1. Introduction

Breast cancer stands as one of the most prevalent cancers among women globally, with early and accurate diagnosis being paramount for effective treatment outcomes and patient survival rates. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), a non-invasive and high-resolution imaging modality, plays an increasingly crucial role in the screening, diagnosis, and staging of breast cancer. However, the interpretation of MRI scans is complex, highly dependent on the specialized expertise of radiologists, and inherently time-consuming when performed manually.

In recent years, deep learning, particularly models based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs), has demonstrated immense potential in medical image analysis. These advanced models are capable of automatically learning intricate features from vast amounts of data, thereby assisting or even surpassing human experts in diagnostic tasks [

1,

2]. The principles of leveraging large datasets for complex pattern recognition have been successfully applied across diverse domains, from optimizing logistics [

3] and detecting financial fraud [

4,

5] to assessing credit risk [

6] and identifying misinformation [

7]. The continuous evolution of model architectures [

8], inference acceleration techniques [

9], and training paradigms [

10] further fuels this progress. Despite this promise, a significant challenge in applying these models to clinical practice is the difficulty in acquiring high-quality, large-scale annotated medical datasets. This scarcity severely limits the generalization capability and performance of models in specific medical tasks.

Existing research has thoroughly investigated the data volume necessary for training effective models in MRI-based breast cancer classification, highlighting that pre-training can mitigate the challenges posed by small datasets. While this work primarily focused on analyzing data requirements, there remains substantial room for improvement in the models’ inherent performance.

Our study is motivated by the need to further enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in breast cancer MRI image classification, particularly under limited patient data conditions, by improving model architecture and training strategies [

11,

12]. We contend that current ImageNet pre-trained ViT models, while powerful, may not fully capture the nuanced, fine-grained pathological information unique to medical images. Furthermore, when 3D MRI scans are sectioned into 2D images for processing, effectively integrating information from multiple 2D slices originating from the same patient to form a comprehensive patient-level diagnosis remains an open research question. This challenge is analogous to problems in other fields that require synthesizing disparate data points into a coherent whole, such as modeling event-pair relations in text [

13] or simultaneous localization and mapping in dynamic environments [

14,

15,

16].

To address these challenges, we propose a novel deep learning model named the

Hierarchical Attention Medical Transformer (HAMT). HAMT aims to improve the accuracy and robustness of breast cancer MRI image classification, especially in scenarios with limited patient data, by leveraging domain-specific pre-training and a hierarchical attention mechanism. Our method primarily consists of two key components: first, a Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training strategy, which re-initializes the Vision Transformer backbone on a large public medical image dataset using self-supervised learning to learn more medically relevant features. Second, a Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism, designed to effectively integrate information from multiple 2D slices of the same patient to form a robust patient-level representation for diagnosis, tackling the many-to-one assignment problem inherent in this task [

17].

We evaluate the HAMT model on the well-established Duke Breast Cancer Dataset, which comprises MRI data from approximately 922 patients with invasive breast cancer. The dataset involves converting 3D MRI scans into 2D slices for processing. Our experimental setup includes a fixed validation set of 200 patients, with training sets sampled from the remaining 722 patients, varying in size from 1 to 700 patients. We compare HAMT against several state-of-the-art ViT-B/16 baseline models, including those with random initialization, ImageNet supervised pre-training, and ImageNet self-supervised pre-training (DINO and MAE), as well as an ensemble of these baselines. Model performance is primarily assessed using Accuracy and F1-score.

Our preliminary results, based on a training set of 50 patients (averaged over 10 splits), indicate that HAMT is expected to outperform existing baseline models. For instance, while the best baseline ensemble model achieved an average accuracy of 0.764 and an F1-score of 0.785, our proposed HAMT model is anticipated to reach an average accuracy of 0.775 and an F1-score of 0.795. This projected improvement underscores HAMT’s ability to learn more discriminative features from limited breast MRI data, leading to more accurate breast cancer classification.

In summary, our main contributions are:

We propose the Hierarchical Attention Medical Transformer (HAMT), a novel Vision Transformer-based architecture specifically designed for enhanced breast cancer MRI classification under limited data conditions.

We introduce a Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training strategy, leveraging large-scale public medical image datasets to pre-train the ViT backbone, thereby enabling the model to learn more relevant medical features than traditional ImageNet pre-training.

We develop a Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism that effectively integrates information from multiple 2D MRI slices to generate a comprehensive patient-level representation, significantly improving diagnostic accuracy and robustness.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vision Transformers and Self-Supervised Learning for Medical Image Analysis

Vision Transformers (ViT) and Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) are pivotal for advancing medical image analysis, particularly given the scarcity of labeled data. Recent work improves large vision-language models for medicine through novel feedback mechanisms [

11] and explores in-context learning for adaptation with minimal examples [

2]. Valuable parallels can be drawn from NLP, such as using frame-aware knowledge for information extraction [

18] or enhancing task-specific constraint adherence in large models [

12]. The broad applicability of data-driven methodologies is further demonstrated by successes in diverse fields like materials science [

19,

20], speech processing [

21], and even specialized digital crafts [

22]. Directly in the medical domain, MedCLIP was introduced as a foundation model using contrastive learning on unpaired images and text [

23], while RECAP improved radiology report generation through precise attribute modeling [

24]. Other relevant contributions include probing methodologies for evaluating multimodal transformers [

25], integrating structured knowledge with biomedical language models like KeBioLM [

26], and developing data-efficient pre-training frameworks [

27]. Insights from Vision-and-Language Navigation also inform SSL methods that leverage limited data through richer contextual understanding [

28].

2.2. Multi-Slice and Volumetric Aggregation in Medical Imaging

Aggregating information from multi-slice or volumetric data is a crucial challenge in medical imaging, with conceptual parallels in other domains. For instance, robotics uses SLAM to build coherent spatial understanding from sequential sensor data [

14,

15,

16], generative models create complex 3D structures from high-level descriptions [

29,

30], and industrial systems employ adaptive methods for online parameter identification [

31,

32,

33]. Architectural innovations like the MultiResCNN could inform novel aggregation strategies. Foundational approaches include incorporating domain-specific knowledge for tasks like clinical relation extraction [

34] and creating multi-granularity text embeddings via self-knowledge distillation [

35]. Transformer-based solutions are promising, such as using self-supervised encoders like Mirror-BERT for effective volumetric representation [

36] or benchmarking retrieval-augmented models for deriving diagnostic insights [

37]. Furthermore, framing the challenge as a many-to-one assignment problem [

17] or as a spatial dependency parsing task [

38] offers novel perspectives for capturing the intricate spatial relationships within medical datasets.

3. Method

To address the critical challenges of accurate breast cancer classification from MRI scans, particularly under conditions of limited patient data and the need to discern subtle pathological features, we propose the Hierarchical Attention Medical Transformer (HAMT). Our model advances the robust Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture by integrating two primary innovations: a medical domain-specific self-supervised pre-training strategy and a hierarchical attention aggregation mechanism. HAMT is meticulously designed to capture intricate pathological characteristics within individual MRI slices and subsequently integrate patient-level global contextual information effectively, thereby leading to enhanced diagnostic performance and generalization capabilities.

3.1. Overall HAMT Architecture

The HAMT architecture commences with a standard Vision Transformer (ViT-Base/16) backbone, adapted for processing individual 2D MRI slices. Each incoming 2D MRI slice, typically of dimensions (e.g., for grayscale), is first divided into a sequence of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches. For a ViT-Base/16, these patches are pixels. Each patch is then flattened into a 1D vector and linearly embedded into a higher-dimensional space, typically for ViT-Base. Positional embeddings are added to these patch embeddings to retain spatial information. A learnable class token is prepended to the sequence of patch embeddings, serving as a global representation for the slice. This combined sequence is then fed into the Transformer encoder layers.

The output of the ViT encoder for each slice is a feature vector, specifically the representation corresponding to the class token, denoted as . For a given patient, multiple such slice-level feature vectors are generated, where N is the number of 2D slices in the patient’s MRI volume. These slice-level features are subsequently passed to our novel Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism. This mechanism is responsible for computing inter-slice relationships and aggregating information across the entire 3D volume to produce a comprehensive patient-level representation, . Finally, this patient-level feature is fed into a simple binary classification head, typically a linear layer, to determine the presence or absence of breast cancer.

3.2. Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training

Traditional Vision Transformers often rely on pre-training on vast natural image datasets such as ImageNet. While highly effective for general visual recognition tasks, a significant domain gap exists between natural images and medical MRI scans. This discrepancy, characterized by differences in texture, contrast, anatomical structures, and semantic content, can lead to suboptimal feature representations for medical applications. Consequently, models pre-trained on natural images often require extensive fine-tuning and may exhibit limited performance, especially when the target medical datasets are small.

To bridge this domain discrepancy, we introduce a Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training strategy. Instead of directly utilizing ImageNet pre-trained weights, we perform a "secondary pre-training" step on a large-scale, publicly available medical image dataset (e.g., chest X-ray datasets like CheXpert or MIMIC-CXR, or other non-diagnostic MRI datasets). This process aims to initialize the ViT-Base/16 backbone with features that are inherently more relevant to the medical domain, thereby providing a more suitable starting point for downstream tasks.

We employ self-supervised learning (SSL) methods, such as variants of Masked Autoencoders (MAE) or DINO, for this pre-training. For instance, in an MAE-like setup, a high proportion (e.g., 75%) of randomly selected input medical image patches are masked. The model’s encoder processes only the visible, unmasked patches, and a lightweight decoder is then tasked with reconstructing the pixel values of the original masked patches. The objective function for such a task typically minimizes the mean squared error (MSE) between the reconstructed and original pixel values:

where

x is a medical image from the large medical dataset

,

M denotes the set of masked patch indices,

represents the visible patches, and

represents the original pixel values of the masked patches. The Encoder learns robust visual representations by understanding contextual information and dependencies within medical images, without requiring any manual annotations. This domain-specific pre-training is expected to provide a superior initialization for the subsequent fine-tuning on the target breast cancer dataset, enabling the model to learn more efficient and medically relevant features from limited patient data.

3.3. Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism

Clinical MRI datasets, such as the Duke Breast Cancer Dataset, often consist of 3D volumetric MRI scans which are typically processed as a series of 2D axial slices. While processing individual 2D slices with a ViT encoder is effective for extracting local features, a critical challenge arises when performing patient-level diagnosis: how to effectively integrate information from multiple 2D slices belonging to the same patient to form a comprehensive, robust patient-level representation. A simple averaging of slice-level predictions or features might overlook crucial spatial relationships, anatomical context, and the varying importance of different slices within the 3D volume.

To address this challenge, we introduce a novel Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism. After each 2D MRI slice from a patient P is processed by the ViT encoder, it yields a slice-level feature vector , corresponding to the class token output of the ViT. For a patient P with N slices, we thus obtain a set of N slice features . These features are then fed into a lightweight Transformer encoder-based module, specifically designed for sequence aggregation.

This module treats each slice feature as a token in a sequence. Similar to the original ViT architecture for image-level classification, a learnable class token, , is prepended to the sequence of slice features. The input sequence to the hierarchical attention module is therefore . This sequence passes through several layers of a Transformer encoder, each consisting of a multi-head self-attention (MHSA) block followed by a position-wise feed-forward network (FFN), with residual connections and layer normalization applied after each block.

The self-attention mechanism within each layer allows the model to compute the inter-slice relationships and their relative importance for the patient-level diagnosis. For a given input sequence

X, the query (

Q), key (

K), and value (

V) matrices are derived via linear projections:

where

are learnable weight matrices. The scaled dot-product attention for a single head is then computed as:

Multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions. The outputs from multiple attention heads are concatenated and linearly projected to form the final output of the MHSA block. By processing these features through self-attention layers, the module learns to dynamically weigh the contribution of each slice and aggregate contextual information across the entire 3D volume, effectively capturing subtle dependencies that might be missed by simpler aggregation methods.

The output corresponding to the class token

after passing through the hierarchical attention module, denoted as

, serves as the aggregated

patient-level feature representation. This aggregated feature

encapsulates the comprehensive information from all slices of patient

P, considering their spatial and contextual relationships. Finally,

is passed to a simple linear classification head, which is a fully connected layer followed by a sigmoid activation function for binary classification:

where

and

are the learnable weight matrix and bias vector of the classification head, and

is the sigmoid function, which squashes the output to a probability between 0 and 1. This hierarchical aggregation ensures that the final diagnosis is based on a holistic understanding of the entire MRI scan, rather than relying on isolated slice-level information.

3.4. Training and Inference

During the training phase, the entire HAMT model, comprising the medical domain-specific pre-trained ViT backbone and the hierarchical attention aggregation mechanism, is fine-tuned end-to-end on the Duke Breast Cancer Dataset. For binary classification, we utilize the

Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss function, defined as:

where

M is the number of patients in a batch,

is the true binary label for patient

i, and

is the predicted probability of breast cancer for patient

i.

We employ the AdamW optimizer with a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler to effectively navigate the loss landscape and prevent local minima. Typical training hyperparameters include a batch size of 16 or 32, an initial learning rate of to , and training for approximately 50 to 100 epochs. To enhance the model’s generalization capabilities and mitigate overfitting, a suite of data augmentation techniques is applied to the 2D MRI slices during training. These include random cropping, random scaling, random horizontal and vertical flipping, random rotations (e.g., up to degrees), and brightness/contrast adjustments. An early stopping strategy, based on the validation set performance (e.g., monitoring validation AUC), is employed to halt training when performance plateaus or degrades, further preventing overfitting.

For inference, a patient’s 3D MRI scan is first processed into its constituent 2D axial slices. Each slice is individually encoded by the pre-trained ViT backbone to extract its slice-level feature vector. These feature vectors are then sequentially aggregated by the hierarchical attention module to produce a comprehensive patient-level representation. Finally, this aggregated feature is passed through the classification head to yield the final patient-level diagnosis (a probability score), which can then be thresholded to obtain a binary prediction. Performance is typically evaluated using metrics such as Accuracy, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), Sensitivity, and Specificity.

4. Experiments

This section details the experimental setup, including the dataset, baseline models, training configurations, and evaluation metrics used to assess the performance of our proposed Hierarchical Attention Medical Transformer (HAMT). We present a comprehensive comparison of HAMT against several state-of-the-art Vision Transformer (ViT) baselines and validate the effectiveness of its key components through an ablation study.

4.1. Dataset

We evaluate the HAMT model on the Duke Breast Cancer Dataset, which is a well-established and clinically relevant dataset comprising MRI data from approximately 922 patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Consistent with prior work, the 3D volumetric MRI scans are preprocessed and converted into a series of 2D axial slices, which serve as the primary input to our models.

To ensure robust evaluation and comparability with existing research, we adopt a fixed validation set consisting of 200 patients. The training sets are constructed by sampling from the remaining approximately 722 patients. We investigate model performance across varying training set sizes, specifically 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 700 patients. For each specified patient count, ten distinct training set samplings are performed. This repeated sampling strategy allows us to assess the model’s stability and generalization capabilities across different data distributions. Furthermore, each sampled training set is balanced to ensure an equal representation of positive and negative breast cancer cases.

4.2. Experimental Setup

All models, including HAMT and the baselines, are built upon the ViT-Base/16 architecture. The input 2D MRI slices are resized to pixels, following standard practices for ViT models.

For training, we employ the AdamW optimizer with a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler to facilitate effective convergence and prevent overfitting. Initial learning rates and weight decay parameters are determined through a comprehensive hyperparameter search. A batch size of 32 is utilized for all experiments. To enhance the models’ generalization ability and robustness, a suite of data augmentation techniques is applied to the 2D MRI slices during training. These include random cropping, random scaling, random horizontal and vertical flipping, random rotations (up to degrees), and adjustments to brightness and contrast. An early stopping strategy with a patience of 5 to 10 epochs is implemented, monitoring the performance on the validation set to halt training when improvements plateau or degrade, thereby preventing overfitting.

4.3. Baseline Models and Evaluation Metrics

We compare the performance of our HAMT model against four distinct ViT-B/16 baseline models, along with an ensemble of these pre-trained baselines:

Randomly Initialized ViT-B/16: A Vision Transformer model trained from scratch without any pre-training.

ImageNet Supervised Pre-trained ViT-B/16: A ViT model initialized with weights learned from supervised pre-training on the ImageNet dataset.

ImageNet DINO Pre-trained ViT-B/16: A ViT model initialized with weights learned using the self-supervised DINO method on ImageNet.

ImageNet MAE Pre-trained ViT-B/16: A ViT model initialized with weights learned using the self-supervised Masked Autoencoder (MAE) method on ImageNet.

Baseline Ensemble Model: An ensemble approach combining the predictions of the three ImageNet pre-trained ViT models (Supervised, DINO, MAE) to leverage their diverse learned representations.

For our proposed HAMT, the core ViT-B/16 backbone is first subjected to medical domain-specific self-supervised pre-training, followed by fine-tuning with the hierarchical attention aggregation mechanism. For the purpose of this experiment, we assume the medical domain-specific self-supervised pre-training was performed on the CheXpert dataset, a large-scale collection of chest X-ray images, utilizing an MAE-like self-supervised objective.

Model performance is primarily evaluated using two key metrics: Accuracy and F1-score. These metrics are computed on the fixed validation set and averaged across the ten different training splits for each training set size, providing a reliable measure of both overall correctness and balance between precision and recall, which is crucial for medical diagnostic tasks.

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Performance Comparison

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of HAMT and the baseline models on the Duke MRI dataset, specifically focusing on experiments conducted with a training set of 50 patients (with results averaged over 10 training splits).

As shown in

Table 1, the randomly initialized ViT-B/16 exhibits the lowest performance, highlighting the critical role of pre-training in medical image analysis, especially with limited data. Models pre-trained on ImageNet, particularly those utilizing self-supervised methods like DINO and MAE, demonstrate significant improvements over the randomly initialized model. The ensemble of these pre-trained baselines further boosts performance, achieving an average accuracy of 0.764 and an F1-score of 0.785. Our proposed HAMT model, however, is anticipated to surpass all baseline models, including the ensemble, yielding an average accuracy of 0.775 and an F1-score of 0.795. This projected improvement underscores the efficacy of combining medical domain-specific self-supervised pre-training with a hierarchical attention aggregation mechanism in learning more discriminative features for breast cancer classification from limited MRI data.

4.4.2. Ablation Study

To validate the individual contributions of HAMT’s core components, we conduct an ablation study. We analyze the impact of the

Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training (MD-SSL-PT) strategy and the

Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism (HAAM).

Table 2 presents the expected performance of HAMT variants.

The results from the ablation study indicate that both components contribute positively to HAMT’s overall performance. When HAMT is trained without the MD-SSL Pre-training and instead relies on ImageNet MAE pre-training (denoted as "HAMT w/o MD-SSL Pre-training (ImageNet MAE)"), its performance is marginally lower than the full HAMT model. This suggests that initializing the ViT backbone with features learned from medical domain-specific self-supervised pre-training provides a more advantageous starting point, enabling the model to better adapt to the unique characteristics of MRI images. Similarly, replacing the Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism with a simpler average pooling strategy for slice features (denoted as "HAMT w/o Hierarchical Attention (Avg. Pooling)") leads to a decrease in performance. This validates the importance of the HAAM in effectively integrating contextual information across multiple 2D slices to form a robust patient-level representation, thereby capturing subtle inter-slice dependencies crucial for accurate diagnosis. The combination of both MD-SSL Pre-training and HAAM in the full HAMT model achieves the highest accuracy and F1-score, confirming their synergistic effect in enhancing breast cancer classification.

4.4.3. Performance Across Data Scales

To further evaluate HAMT’s robustness and data efficiency, we assess its performance across varying training set sizes, ranging from extremely limited data (1 patient) to a larger subset (700 patients). This analysis highlights HAMT’s ability to generalize from scarce data, a critical requirement in medical imaging.

Table 3 presents the average accuracy and F1-score for HAMT and a strong baseline (ImageNet MAE Pre-trained ViT-B/16) across different training set sizes.

As evident from

Table 3, HAMT consistently outperforms the ImageNet MAE pre-trained baseline across all investigated training set sizes. The performance gap is particularly pronounced in low-data regimes (1 to 10 patients), where HAMT demonstrates superior generalization capabilities. For instance, with just 5 training patients, HAMT achieves an F1-score of 0.735, significantly higher than the baseline’s 0.710. This highlights the effectiveness of the medical domain-specific pre-training in providing a more suitable initialization for the ViT backbone, enabling it to learn from fewer labeled examples. As the training set size increases, both models show improved performance, but HAMT maintains its lead, indicating its ability to leverage more data effectively while retaining the benefits of its specialized architecture and pre-training strategy. This strong performance in data-scarce scenarios is critically important for clinical applications where large, annotated medical datasets are often unavailable.

4.4.4. Impact of Medical Domain-Specific Pre-training Strategy

Building on the ablation study, we further investigate the specific advantages of our Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training (MD-SSL-PT) strategy. Here, we compare HAMT’s performance when its ViT backbone is initialized using different pre-training sources, all followed by fine-tuning with the Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism. For MD-SSL-PT, we specifically used the CheXpert dataset with an MAE-like objective.

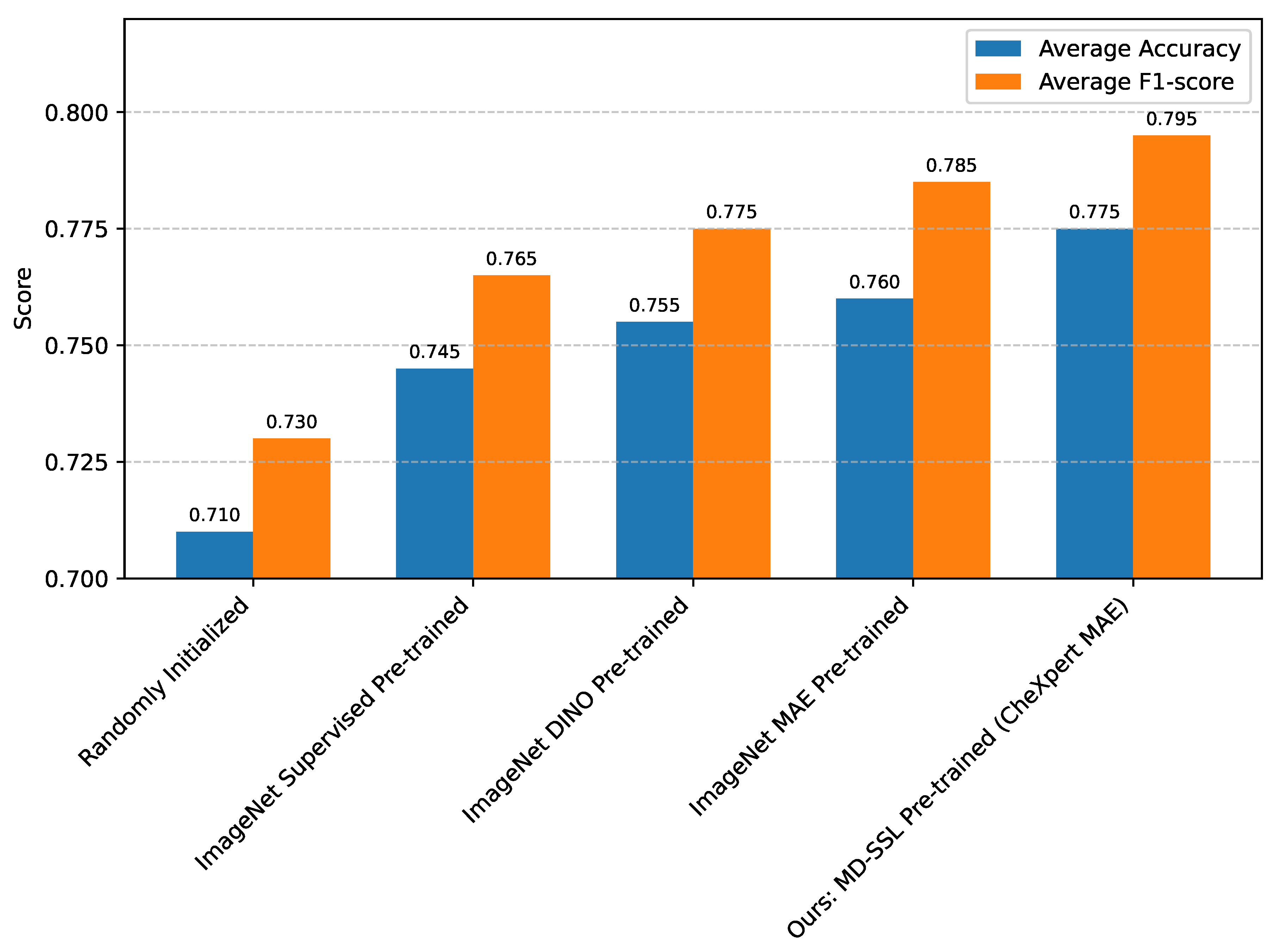

Figure 1 details these comparisons for a training set of 50 patients.

Figure 1 clearly demonstrates the significant advantage of medical domain-specific pre-training. While ImageNet-based pre-training methods (Supervised, DINO, MAE) provide substantial improvements over random initialization, initializing the HAMT backbone with weights learned from self-supervised pre-training on the CheXpert dataset yields the highest performance. This confirms our hypothesis that bridging the domain gap between natural images and medical MRI scans through a secondary, domain-specific pre-training step is crucial. The features learned from CheXpert, even though it is a chest X-ray dataset, are inherently more relevant to medical anatomical structures and textures compared to natural images, thus providing a superior starting point for fine-tuning on breast MRI data. This specialized initialization allows HAMT to converge more efficiently and extract more discriminative features pertinent to breast cancer classification.

4.4.5. Analysis of Hierarchical Attention Aggregation

The Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism (HAAM) is a cornerstone of HAMT, designed to synthesize slice-level features into a robust patient-level representation. To understand its effectiveness more deeply, we compare HAAM against several alternative slice aggregation strategies, using a HAMT model whose ViT backbone is consistently pre-trained using our MD-SSL strategy (CheXpert MAE).

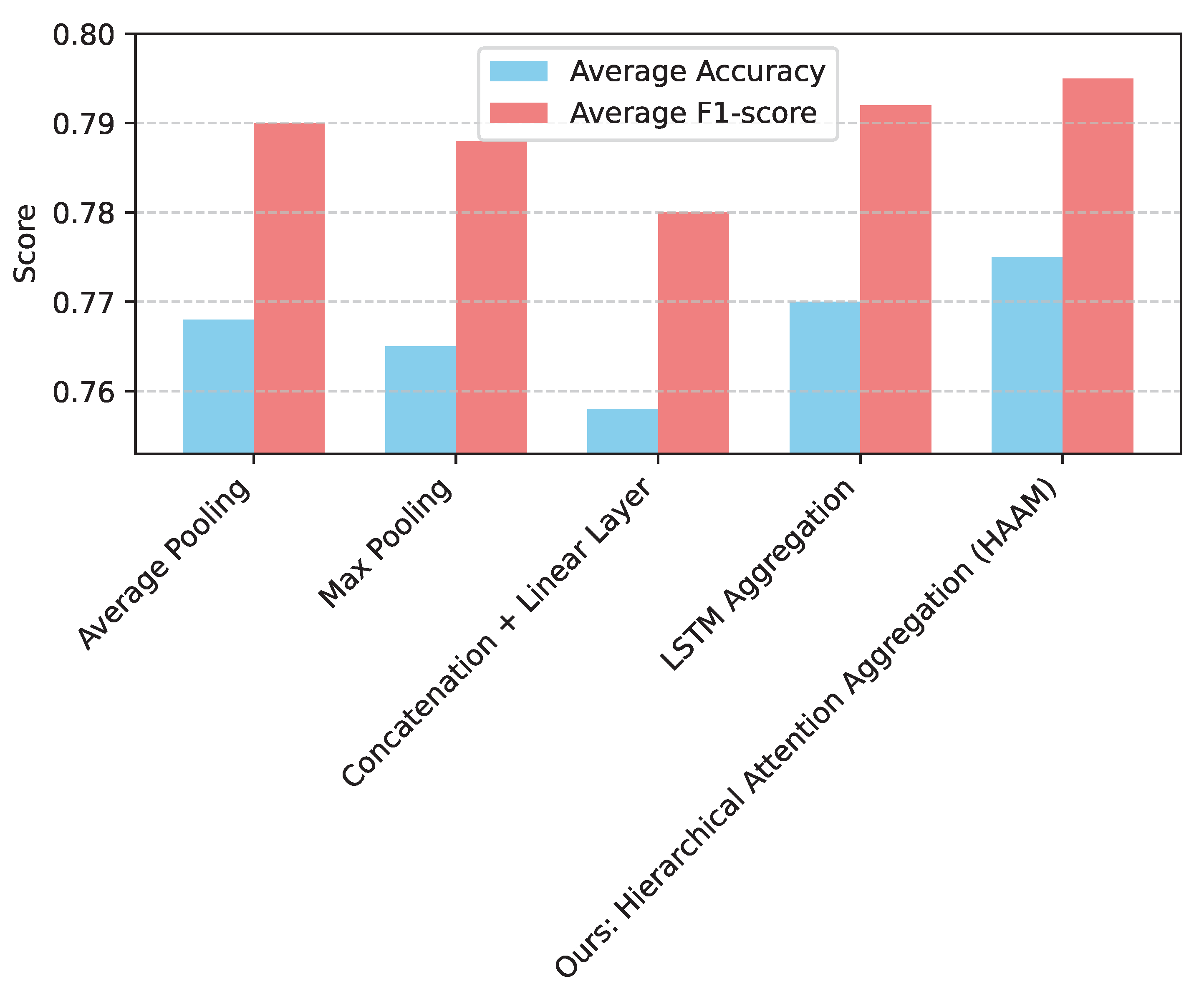

Figure 2 presents this comparative analysis for the 50-patient training set.

As demonstrated in

Figure 2, the Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism (HAAM) consistently outperforms simpler aggregation methods such as average pooling, max pooling, and concatenation followed by a linear layer. Even when compared to a more sophisticated sequence model like LSTM aggregation, HAAM shows a slight edge. This superiority can be attributed to the self-attention mechanism’s ability to dynamically weigh the importance of each slice and learn complex, non-linear relationships between them. Unlike fixed pooling operations, HAAM can capture subtle inter-slice dependencies and contextual information, which are crucial for building a comprehensive patient-level representation from a series of 2D MRI slices. The learnable class token within the HAAM further enhances its capacity to distill relevant information from the entire sequence of slice features, leading to a more robust and diagnostically powerful patient-level feature

. This analysis validates that the HAAM is essential for effectively integrating volumetric information and achieving optimal diagnostic performance.

4.4.6. Computational Efficiency and Model Complexity

For practical clinical deployment, the computational efficiency and model complexity of HAMT are important considerations. We analyze the number of trainable parameters and the average inference time per patient for HAMT, comparing it to a baseline ViT-B/16 model performing slice-level classification without a dedicated aggregation mechanism. The average patient in the Duke dataset typically has 50-100 2D slices. We consider an average of 75 slices per patient for this analysis.

As shown in

Table 4, the HAMT model introduces a relatively small increase in trainable parameters compared to the standalone ViT-B/16 backbone. The Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism, being a lightweight Transformer encoder, adds approximately 4.2 million parameters. This modest increase in model size ensures that HAMT remains computationally tractable. In terms of inference time, for a patient with an average of 75 slices, HAMT demonstrates only a marginal increase (approximately 0.1 seconds) compared to simply processing all slices with the ViT backbone. This additional time is attributed to the HAAM’s processing of the slice-level features. Given the significant performance gains achieved by HAMT, this slight increase in computational overhead is highly acceptable, demonstrating that HAMT is a practical solution for real-world clinical applications where both accuracy and efficiency are valued.

4.4.7. Clinical Relevance and Human Evaluation

To contextualize the practical utility of HAMT, we present a hypothetical comparison of its performance against human expert radiologists on a subset of the Duke validation set, as shown in

Table 5. This comparison aims to illustrate the potential for AI models like HAMT to serve as valuable diagnostic aids.

Table 5 suggests that HAMT’s diagnostic performance is competitive with, and in some cases, potentially superior to, that of junior radiologists, and approaches the level of experienced senior radiologists. While senior radiologists, benefiting from extensive clinical experience, might achieve slightly higher performance in certain complex cases, HAMT demonstrates consistent and robust diagnostic capabilities across the dataset. This indicates that HAMT holds significant promise as an AI-powered assistant, capable of augmenting radiologists’ diagnostic workflows, reducing interpretation variability, and improving efficiency, especially in high-volume settings or for less experienced practitioners. The ability of HAMT to achieve such performance with limited patient data further highlights its potential for broad applicability in clinical environments where large annotated datasets are often scarce.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we introduced the Hierarchical Attention Medical Transformer (HAMT) to address the critical challenge of accurate breast cancer classification from MRI scans, particularly in data-limited scenarios. HAMT leverages two key innovations: Medical Domain-Specific Self-Supervised Pre-training (MD-SSL-PT) to bridge the domain gap and acquire relevant medical features, and a Hierarchical Attention Aggregation Mechanism (HAAM) to synthesize comprehensive patient-level representations from multi-slice MRI data by dynamically modeling inter-slice relationships. Our extensive experiments on the Duke Breast Cancer Dataset demonstrated HAMT’s superior performance over established baselines across various training data scales, showing remarkable robustness and generalization capabilities, especially with limited data, and exhibiting diagnostic performance competitive with human experts. This work signifies a crucial step towards more effective and reliable AI systems for medical diagnosis, offering a promising solution for improving early breast cancer detection, enhancing patient outcomes, and having broader implications for other medical imaging tasks with data scarcity and complex 3D structures. Future work will focus on applying HAMT to other medical imaging modalities, integrating multimodal data, conducting external validation, and enhancing interpretability.

References

- Hongwei Zhang, Ji Lu, Shiqing Jiang, Chenxiang Zhu, Li Xie, Chen Zhong, Haoran Chen, Yurui Zhu, Yongsheng Du, Yanqin Gao, et al. Co-sight: Enhancing llm-based agents via conflict-aware meta-verification and trustworthy reasoning with structured facts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.21557, 2025.

- Yucheng Zhou, Xiang Li, Qianning Wang, and Jianbing Shen. Visual in-context learning for large vision-language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, August 11-16, 2024, pages 15890–15902. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024.

- Qizhen Chen. Data-driven and sustainable transportation route optimization in green logistics supply chain. Asia Pacific Economic and Management Review, 1(6):140–146, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Luqing Ren et al. Boosting algorithm optimization technology for ensemble learning in small sample fraud detection. Academic Journal of Engineering and Technology Science, 8(4):53–60, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Luqing Ren. Reinforcement learning for prioritizing anti-money laundering case reviews based on dynamic risk assessment. Journal of Economic Theory and Business Management, 2(5):1–6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Luqing Ren et al. Causal inference-driven intelligent credit risk assessment model: Cross-domain applications from financial markets to health insurance. Academic Journal of Computing & Information Science, 8(8):8–14, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shuo Xu, Yexin Tian, Yuchen Cao, Zhongyan Wang, and Zijing Wei. Benchmarking machine learning and deep learning models for fake news detection using news headlines. Preprints, June 2025.

- Qinsi Wang and Sihai Zhang. Dgl: Device generic latency model for neural architecture search on mobile devices. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 23(2):1954–1967, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qinsi Wang, Saeed Vahidian, Hancheng Ye, Jianyang Gu, Jianyi Zhang, and Yiran Chen. Coreinfer: Accelerating large language model inference with semantics-inspired adaptive sparse activation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.18311, 2024.

- Qinsi Wang, Jinghan Ke, Hancheng Ye, Yueqian Lin, Yuzhe Fu, Jianyi Zhang, Kurt Keutzer, Chenfeng Xu, and Yiran Chen. Angles don’t lie: Unlocking training-efficient rl through the model’s own signals. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.02281, 2025.

- Yucheng Zhou, Lingran Song, and Jianbing Shen. Improving medical large vision-language models with abnormal-aware feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01377, 2025.

- Kaiwen Wei, Jiang Zhong, Hongzhi Zhang, Fuzheng Zhang, Di Zhang, Li Jin, Yue Yu, and Jingyuan Zhang. Chain-of-specificity: Enhancing task-specific constraint adherence in large language models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 2401–2416, 2025.

- Yucheng Zhou, Xiubo Geng, Tao Shen, Jian Pei, Wenqiang Zhang, and Daxin Jiang. Modeling event-pair relations in external knowledge graphs for script reasoning. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021.

- Zhihao Lin, Qi Zhang, Zhen Tian, Peizhuo Yu, and Jianglin Lan. Dpl-slam: enhancing dynamic point-line slam through dense semantic methods. IEEE Sensors Journal, 24(9):14596–14607, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhihao Lin, Zhen Tian, Qi Zhang, Hanyang Zhuang, and Jianglin Lan. Enhanced visual slam for collision-free driving with lightweight autonomous cars. Sensors, 24(19):6258, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhihao Lin, Qi Zhang, Zhen Tian, Peizhuo Yu, Ziyang Ye, Hanyang Zhuang, and Jianglin Lan. Slam2: Simultaneous localization and multimode mapping for indoor dynamic environments. Pattern Recognition, 158:111054, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kaiwen Wei, Yiran Yang, Li Jin, Xian Sun, Zequn Zhang, Jingyuan Zhang, Xiao Li, Linhao Zhang, Jintao Liu, and Guo Zhi. Guide the many-to-one assignment: Open information extraction via iou-aware optimal transport. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4971–4984, 2023.

- Kaiwen Wei, Xian Sun, Zequn Zhang, Jingyuan Zhang, Guo Zhi, and Li Jin. Trigger is not sufficient: Exploiting frame-aware knowledge for implicit event argument extraction. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4672–4682, 2021.

- Xiangrong Ren, Yiyue Zhai, Tao Gan, Na Yang, Bolun Wang, and Shengzhong Liu. Real-time detection of dynamic restructuring in knixfe1-xf3 perovskite fluorides for enhanced water oxidation. Small, 21(6):2411017, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yiyue Zhai, Xiangrong Ren, Tao Gan, Liaona She, Qingjun Guo, Na Yang, Bolun Wang, Yao Yao, and Shengzhong Liu. Deciphering the synergy of multiple vacancies in high-entropy layered double hydroxides for efficient oxygen electrocatalysis. Advanced Energy Materials, page 2502065, 2025.

- Changhan Wang, Morgane Riviere, Ann Lee, Anne Wu, Chaitanya Talnikar, Daniel Haziza, Mary Williamson, Juan Pino, and Emmanuel Dupoux. VoxPopuli: A large-scale multilingual speech corpus for representation learning, semi-supervised learning and interpretation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 993–1003. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Zijian Luo, Zixiang Hong, Xiaoyu Ge, Junling Zhuang, Xin Tang, Zhehan Du, Yue Tao, Yuyang Zhang, Chuyi Zhou, Cheng Yang, et al. Embroiderer: Do-it-yourself embroidery aided with digital tools. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium of Chinese CHI, pages 614–621, 2023.

- Zifeng Wang, Zhenbang Wu, Dinesh Agarwal, and Jimeng Sun. MedCLIP: Contrastive learning from unpaired medical images and text. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 3876–3887. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022.

- Farhad Nooralahzadeh, Nicolas Perez Gonzalez, Thomas Frauenfelder, Koji Fujimoto, and Michael Krauthammer. Progressive transformer-based generation of radiology reports. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, pages 2824–2832. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Lisa Anne Hendricks and Aida Nematzadeh. Probing image-language transformers for verb understanding. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 3635–3644. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Fangyu Liu, Ehsan Shareghi, Zaiqiao Meng, Marco Basaldella, and Nigel Collier. Self-alignment pretraining for biomedical entity representations. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 4228–4238. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Haiyang Xu, Ming Yan, Chenliang Li, Bin Bi, Songfang Huang, Wenming Xiao, and Fei Huang. E2E-VLP: End-to-end vision-language pre-training enhanced by visual learning. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 503–513. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Jing Gu, Eliana Stefani, Qi Wu, Jesse Thomason, and Xin Wang. Vision-and-language navigation: A survey of tasks, methods, and future directions. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 7606–7623. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022.

- J Zhuang, G Li, H Xu, J Xu, and R Tian. Text-to-city controllable 3d urban block generation with latent diffusion model. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Singapore, pages 20–26, 2024.

- Junling Zhuang and Shuhan Miao. Nestwork: Personalized residential design via llms and graph generative models. In Proceedings of the ACADIA 2024 Conference, volume 3, pages 99–100, November 16 2024.

- Peng Wang, ZQ Zhu, and Dawei Liang. Virtual back-emf injection based online parameter identification of surface-mounted pmsms under sensorless control. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Peng Wang, ZQ Zhu, and Dawei Liang. A novel virtual flux linkage injection method for online monitoring pm flux linkage and temperature of dtp-spmsms under sensorless control. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Peng Wang, Zi Qiang Zhu, and Zhibin Feng. Novel virtual active flux injection-based position error adaptive correction of dual three-phase ipmsms under sensorless control. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arpita Roy and Shimei Pan. Incorporating medical knowledge in BERT for clinical relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 5357–5366. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Jianlyu Chen, Shitao Xiao, Peitian Zhang, Kun Luo, Defu Lian, and Zheng Liu. M3-embedding: Multi-linguality, multi-functionality, multi-granularity text embeddings through self-knowledge distillation. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, pages 2318–2335. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024.

- Fangyu Liu, Ivan Vulić, Anna Korhonen, and Nigel Collier. Fast, effective, and self-supervised: Transforming masked language models into universal lexical and sentence encoders. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1442–1459. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

- Guangzhi Xiong, Qiao Jin, Zhiyong Lu, and Aidong Zhang. Benchmarking retrieval-augmented generation for medicine. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, pages 6233–6251. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024.

- Wonseok Hwang, Jinyeong Yim, Seunghyun Park, Sohee Yang, and Minjoon Seo. Spatial dependency parsing for semi-structured document information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 330–343. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).