Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

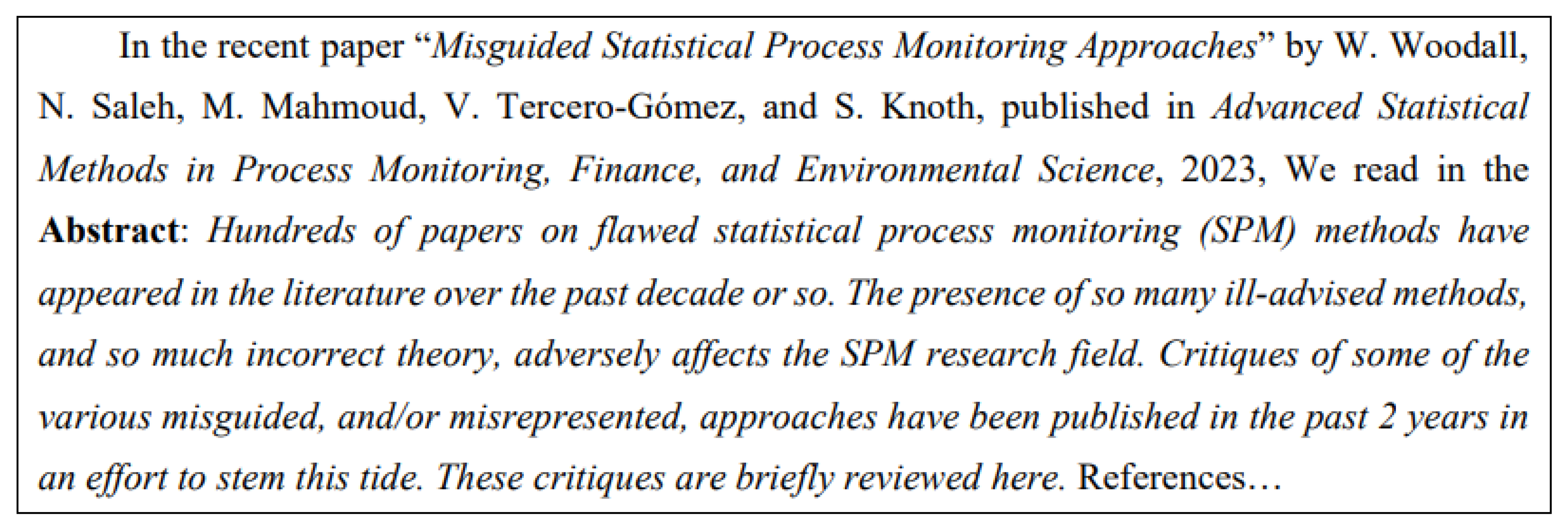

1. Introduction

- a)

- in the 1st of them, we have a sample (the “The Garden of flowers… in [24]”) of “products (papers)” produced by various production lines (authors)

- b)

- while, in the other, we have some few products produced by the same production line (same author)

- c)

- several inspectors (Peer Reviewers, PRs) analyse the “quality of the products” in the two departments; the PRs can be the same (but we do not know) for both the departments

- d)

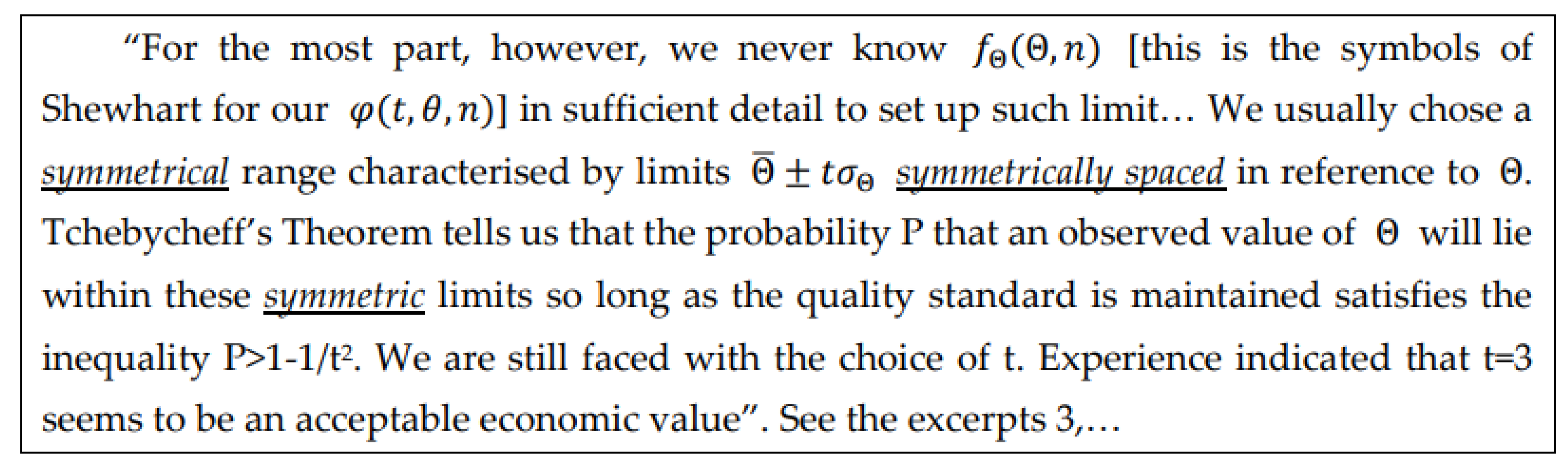

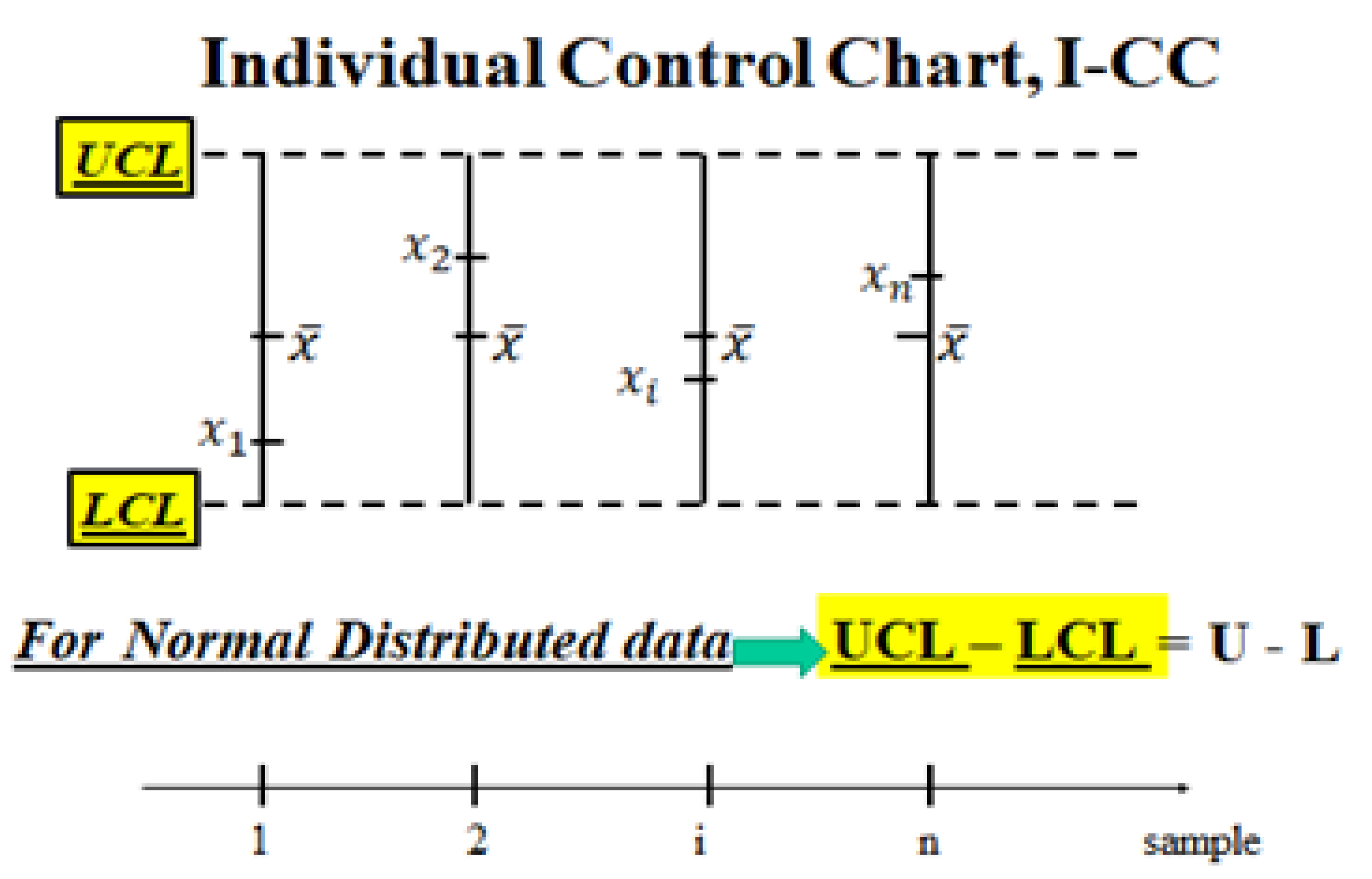

- The final result, according to the judgment of the inspectors (PRs), is the following: the products stored in the 1st dept. are good, while the products in the 2nd dept. are defective. It is a very clear situation, as one can guess by the following statement of a PR: “Our limits [in the 1st dept.] are calculated usingstandard mathematical statistical results/methods as is typical in the vast literature of similar papers [4,5,24].” See the standard mathematical statistical results/methods in the Figures A1, A2, A3, of the Appendix A and meditate (see the formulae there)!

2. Materials and Methods

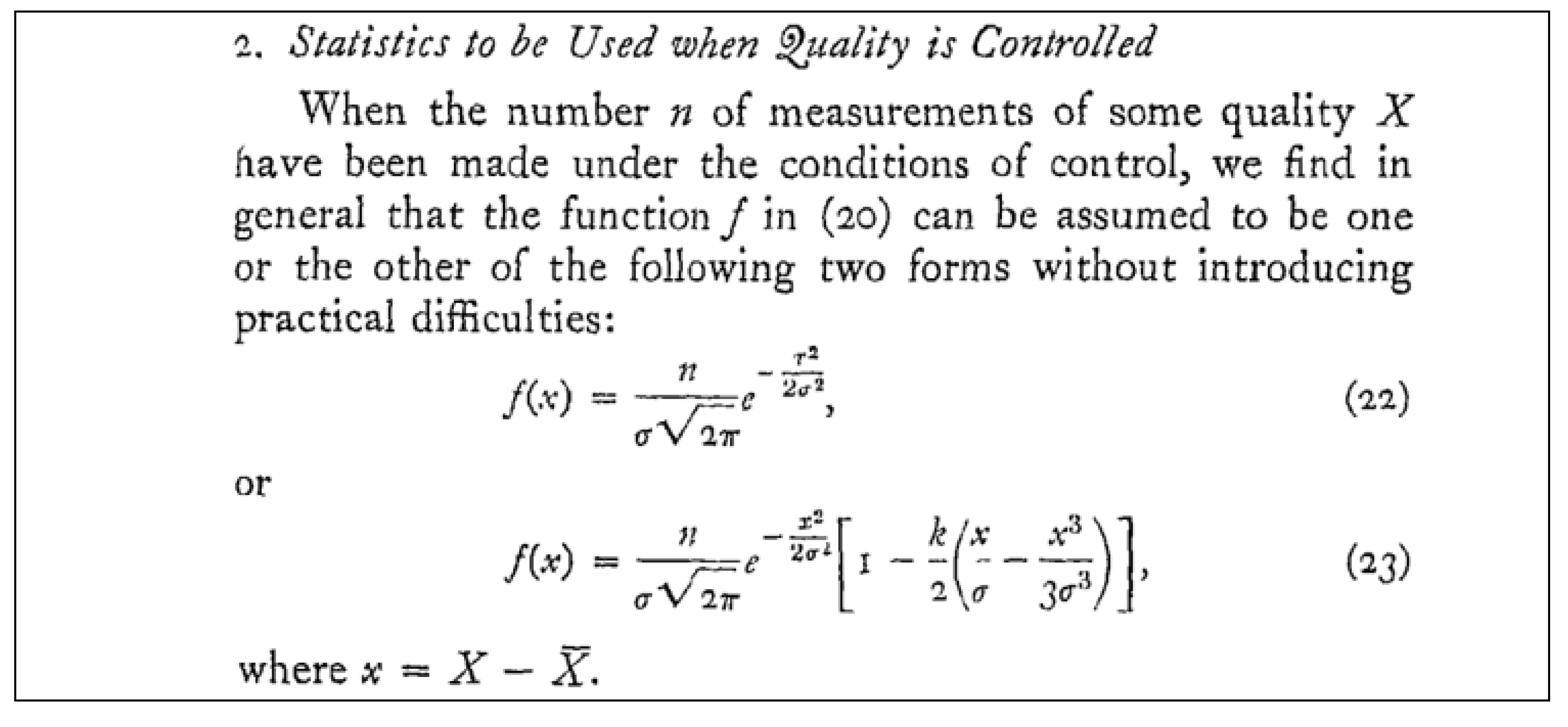

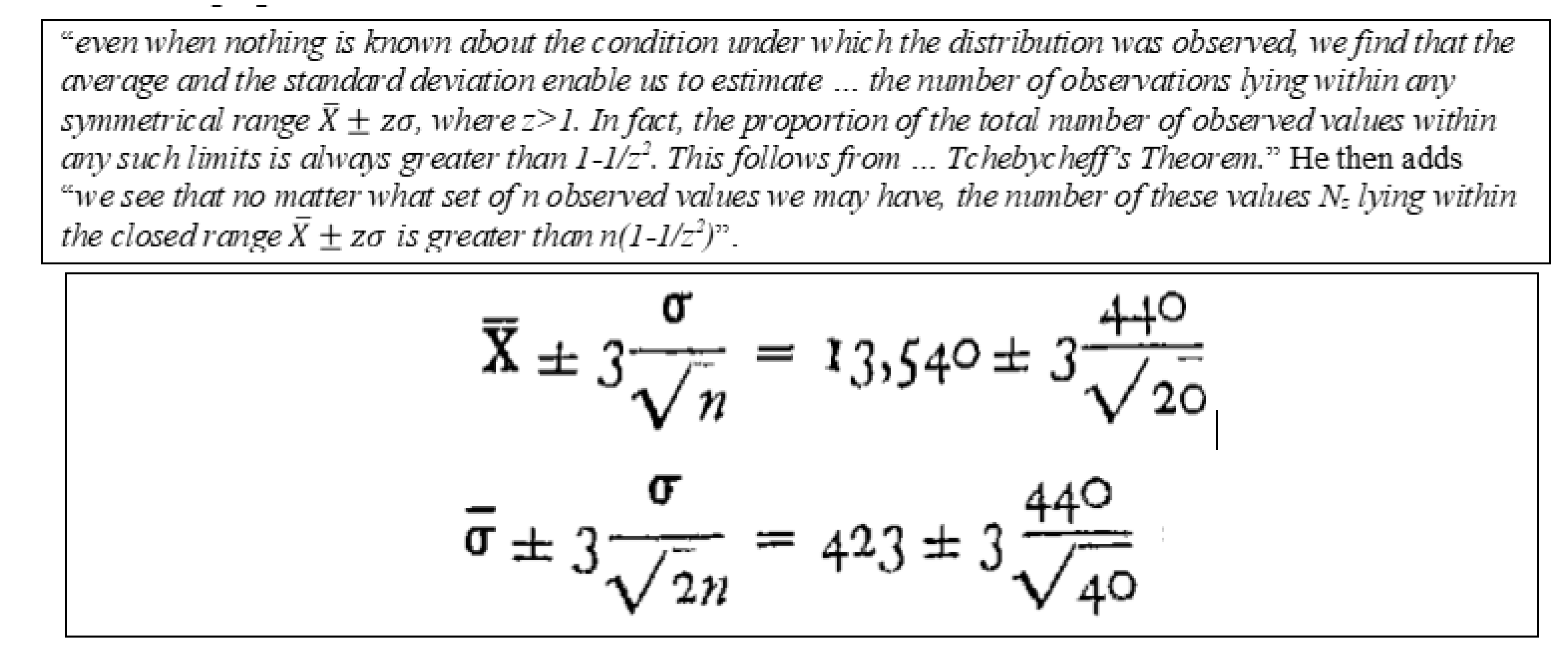

2.1. A Reduced Background of Statistical Concepts

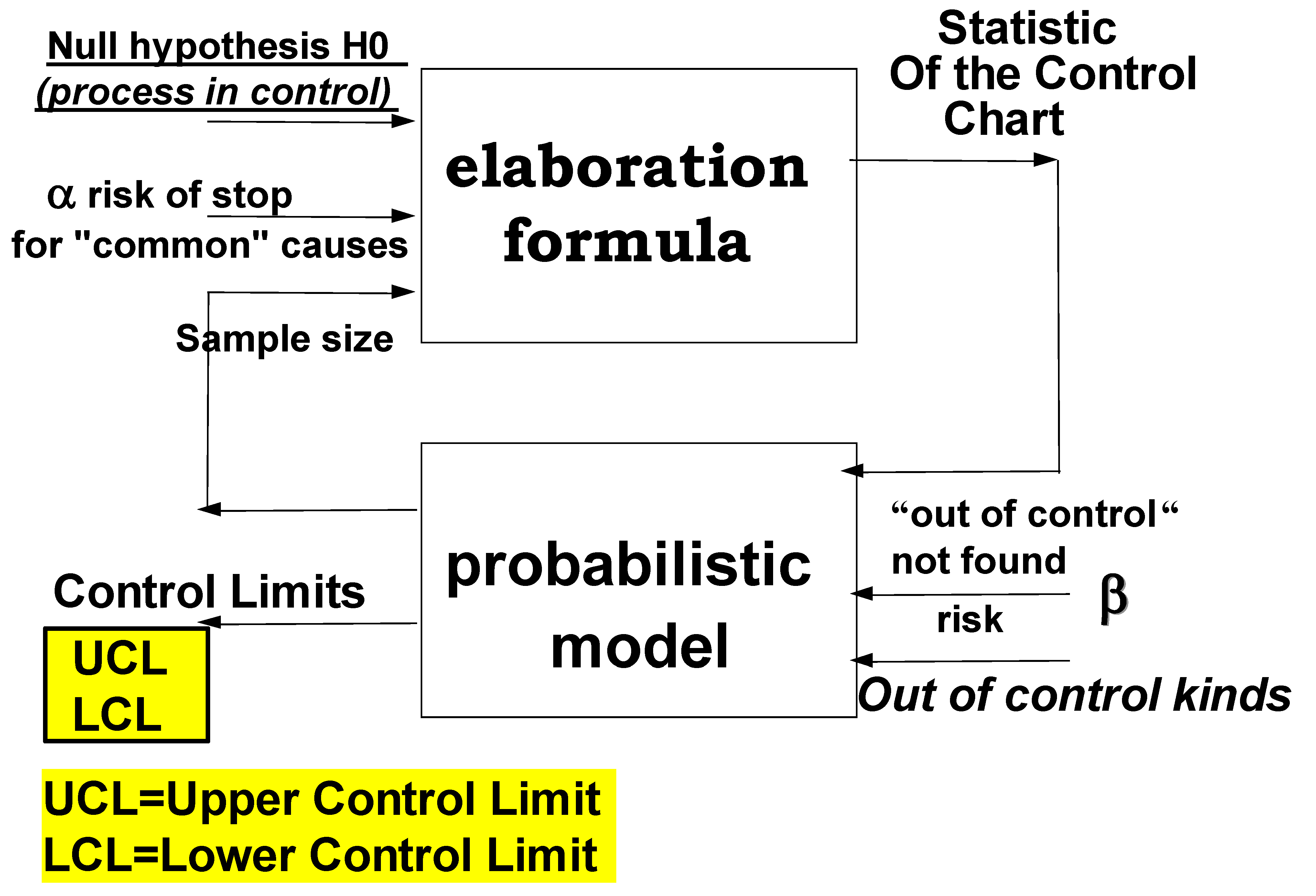

2.2. Control Charts for Process Management

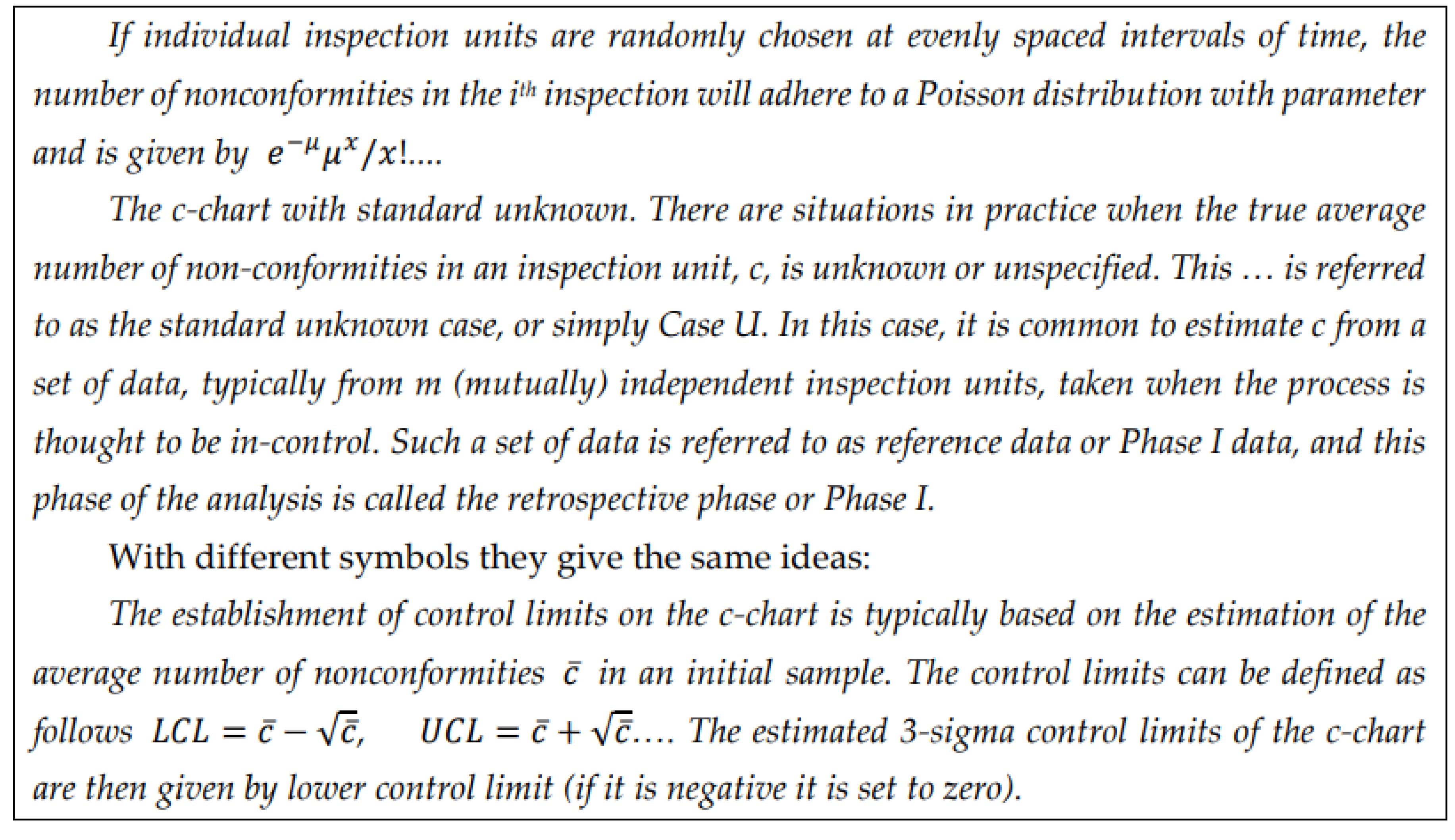

2.3. Control Charts for Attributes

2.4. Statistics and RIT

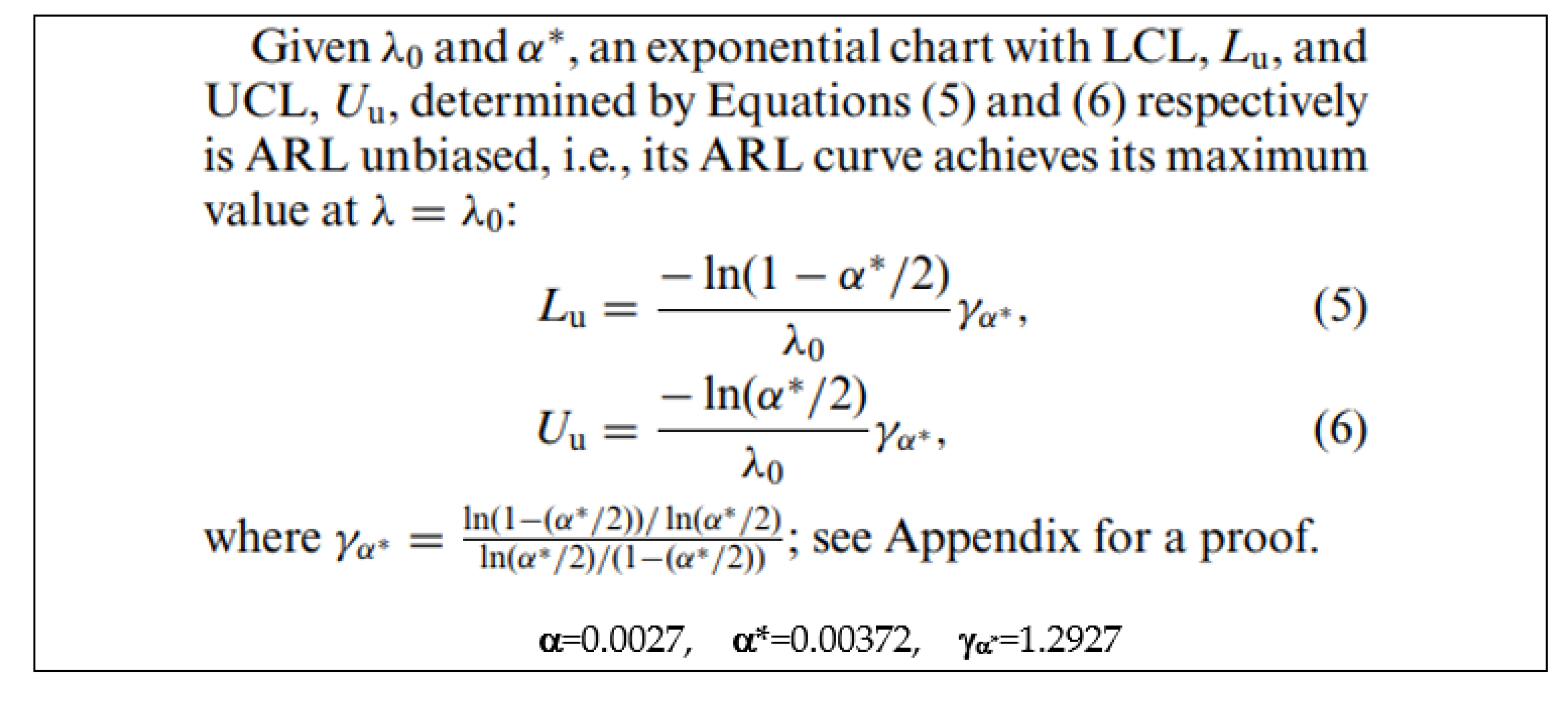

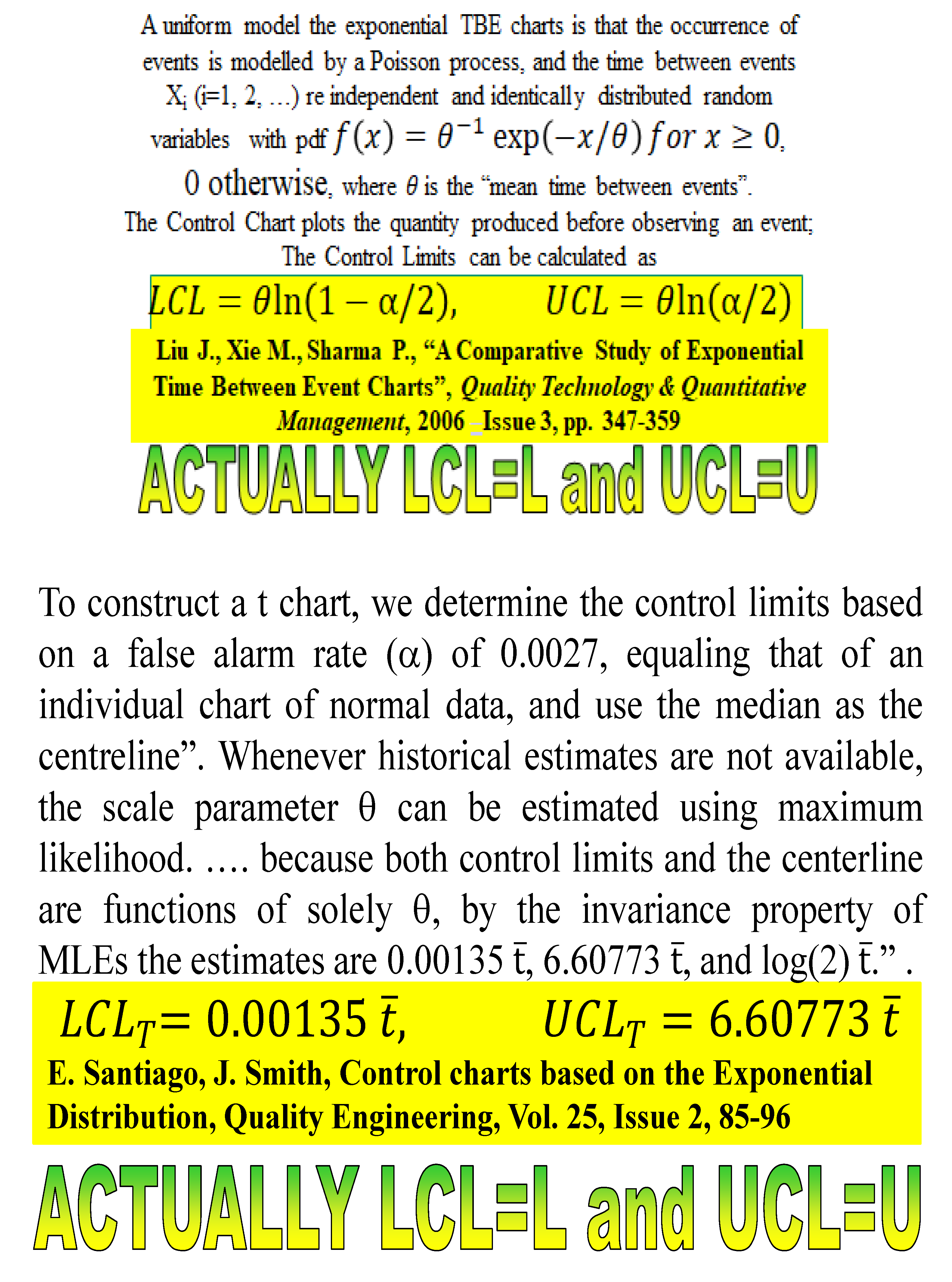

2.5. Control Charts for TBE Data. Some Ideas for Phase I Analysis

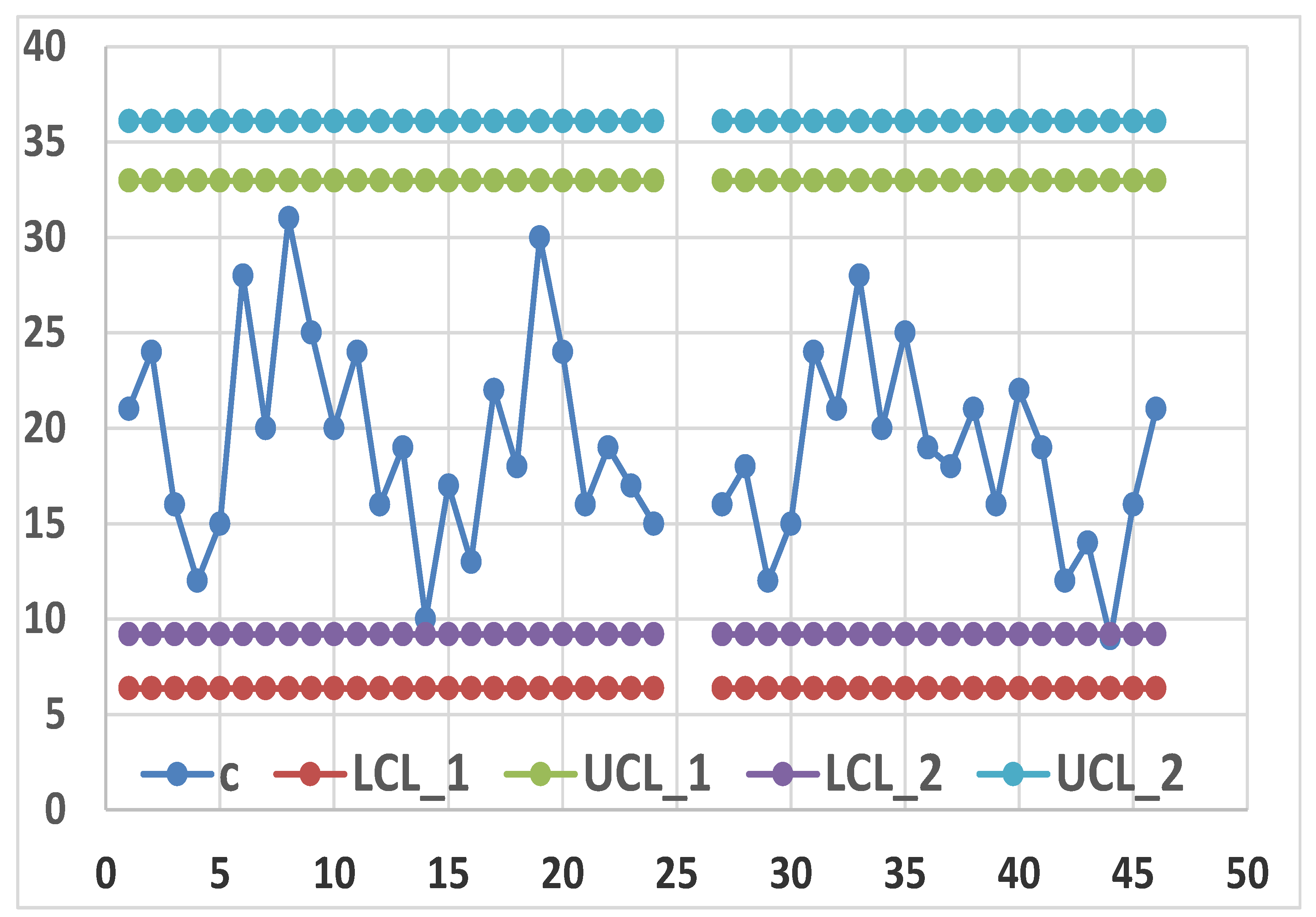

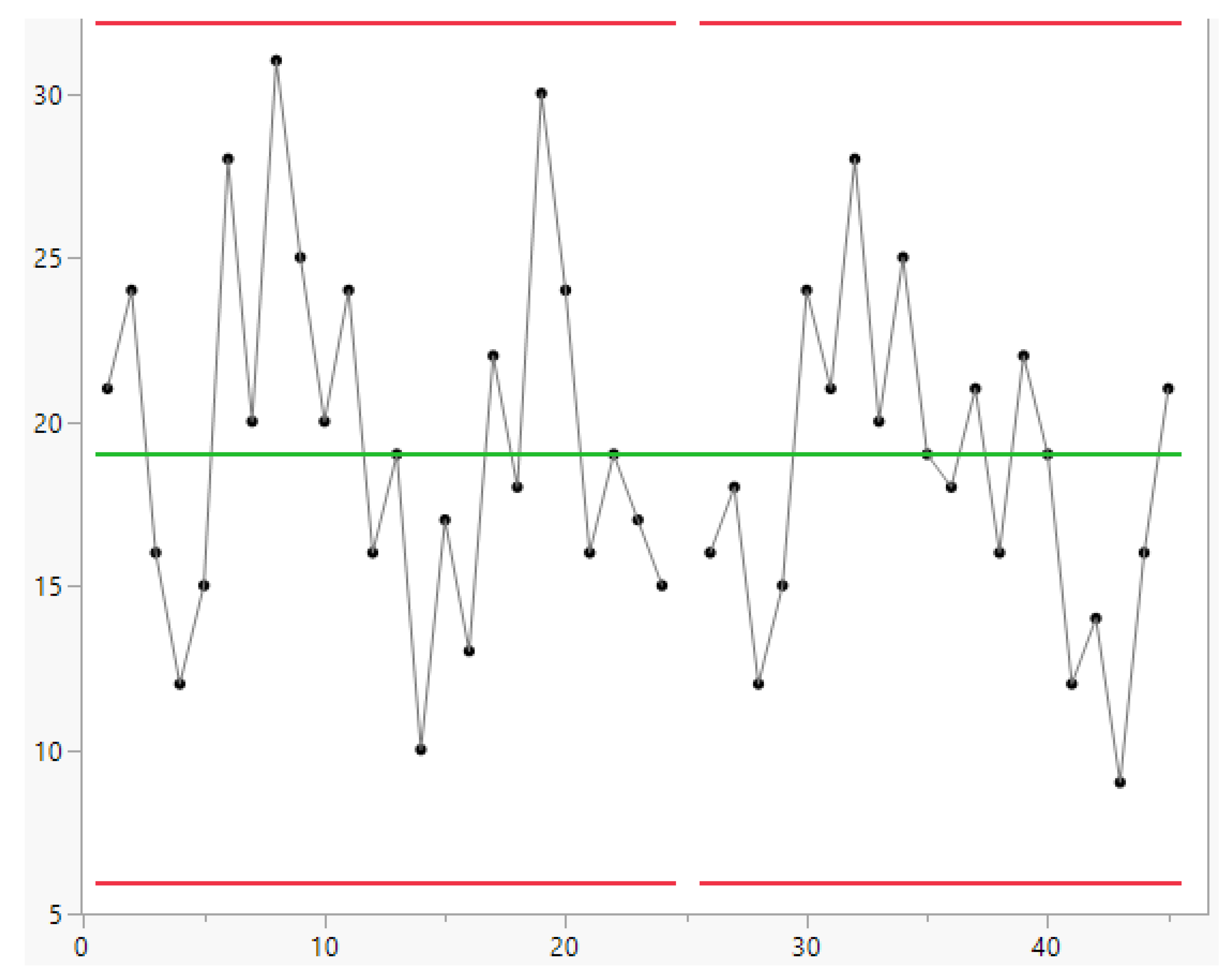

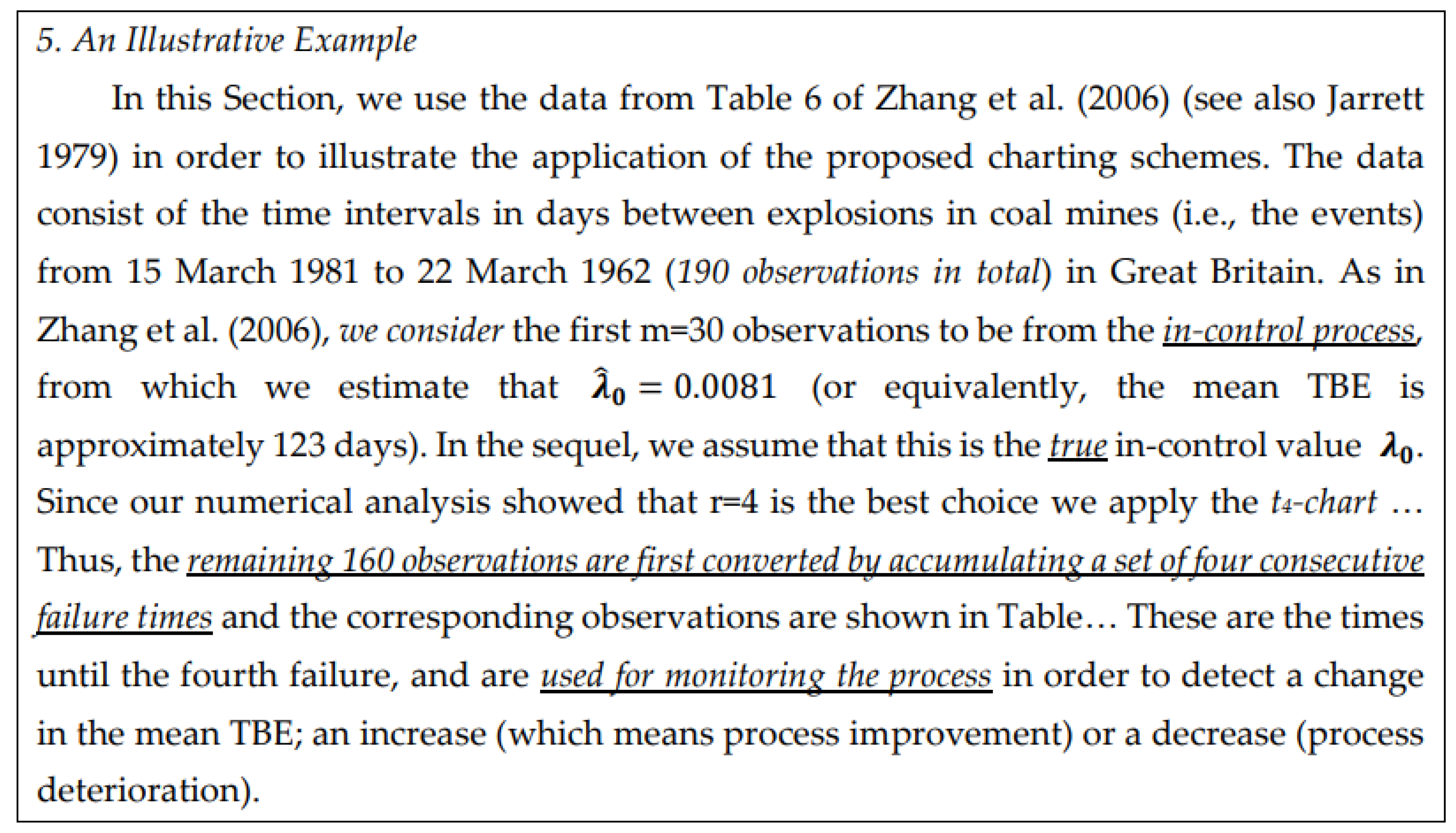

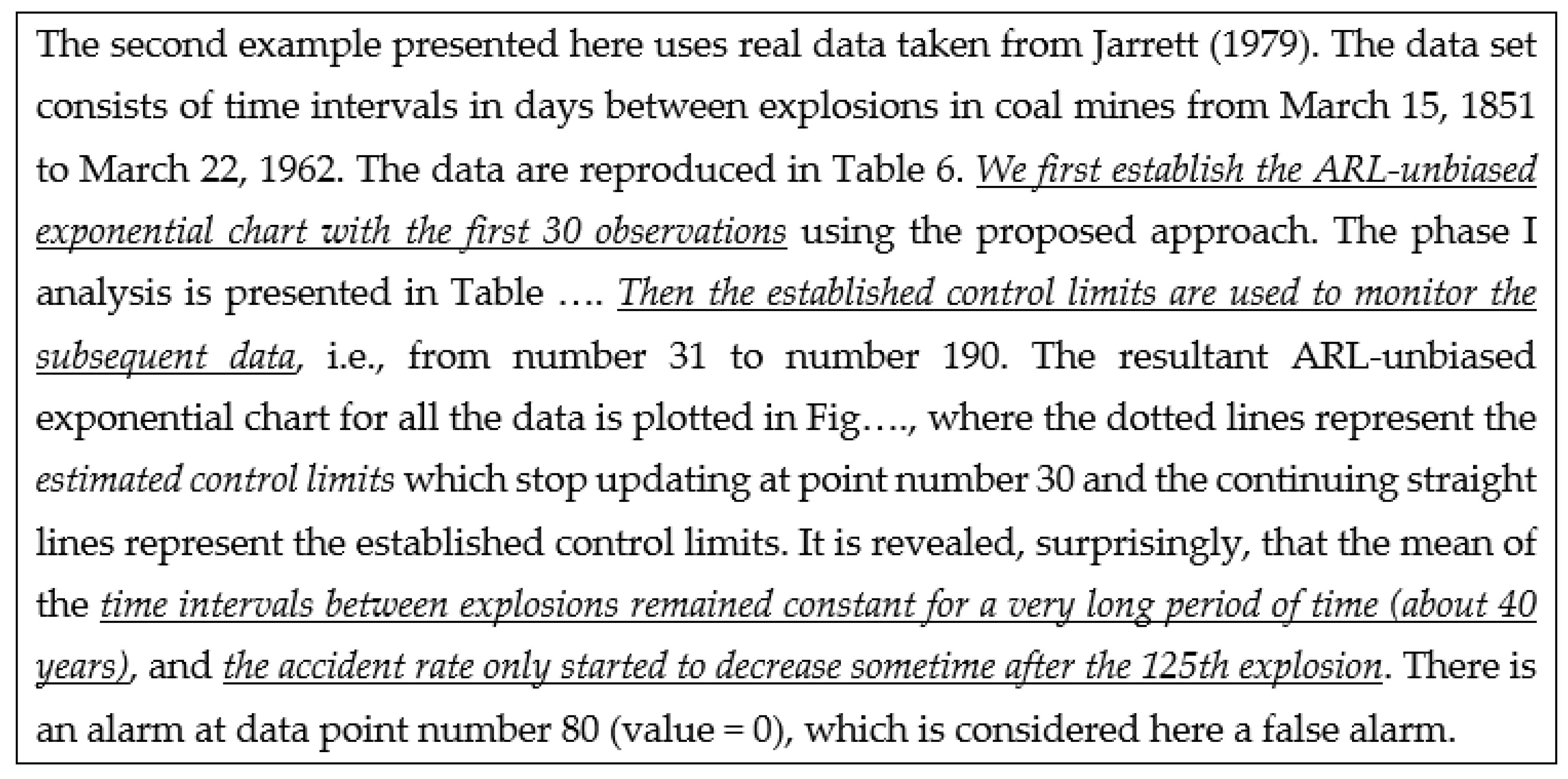

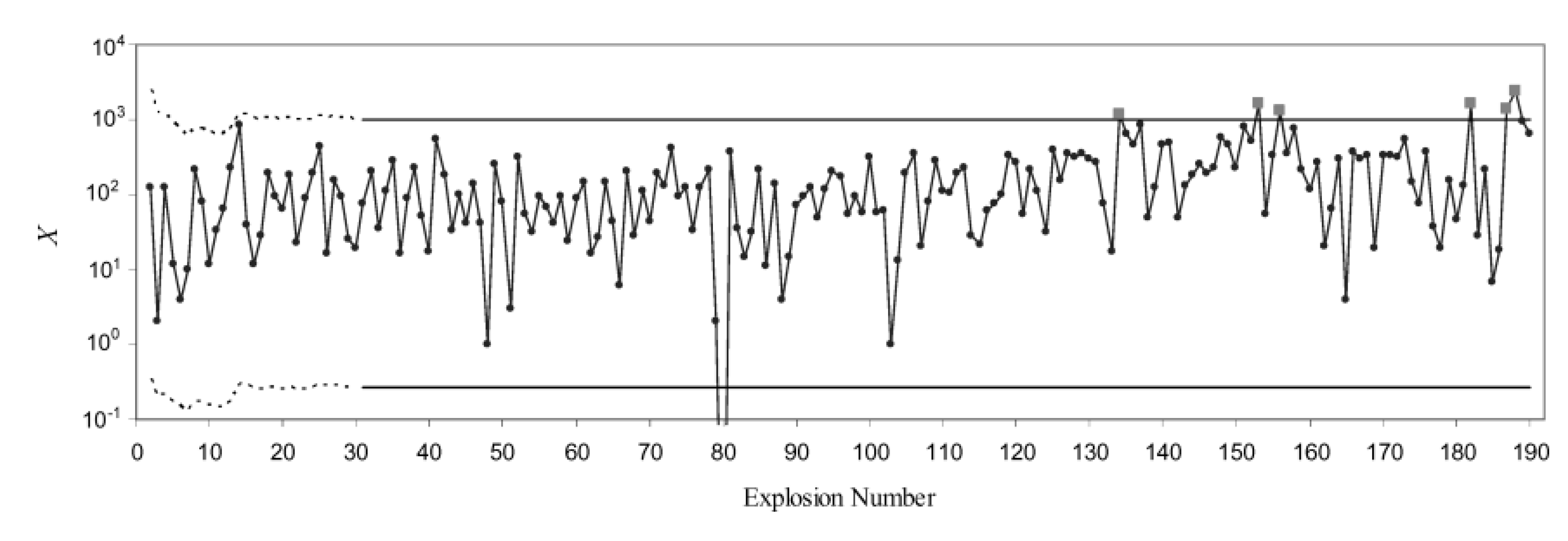

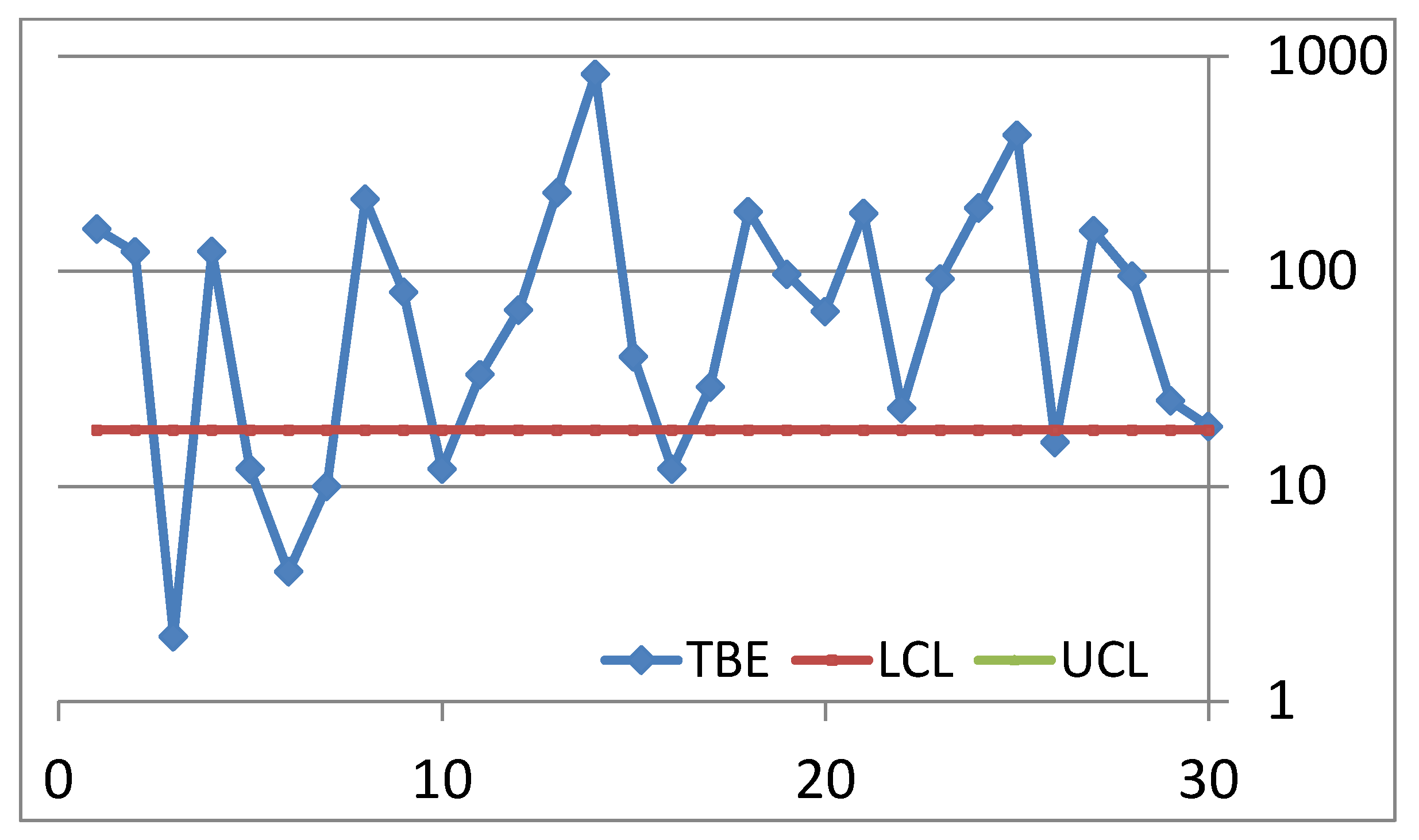

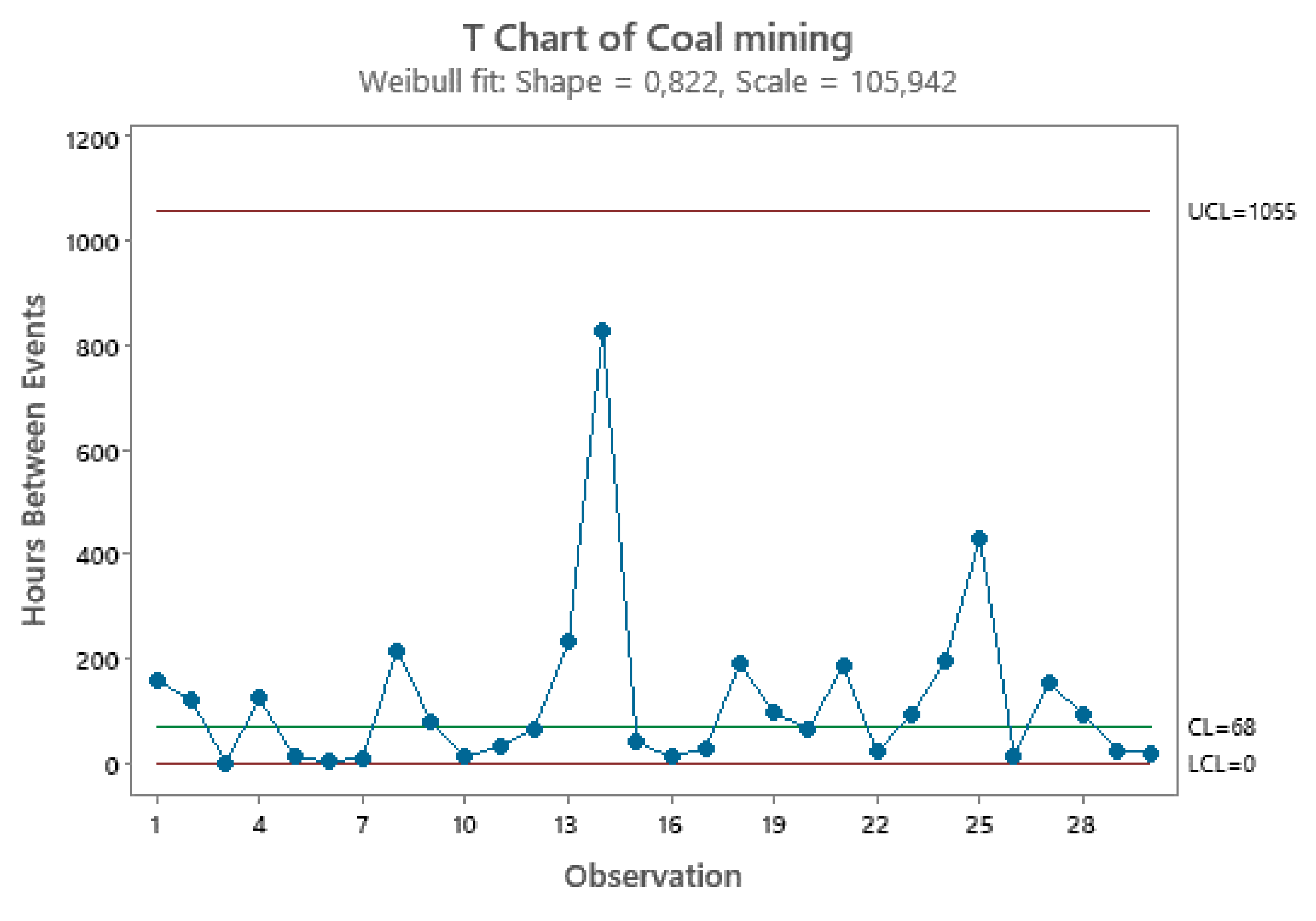

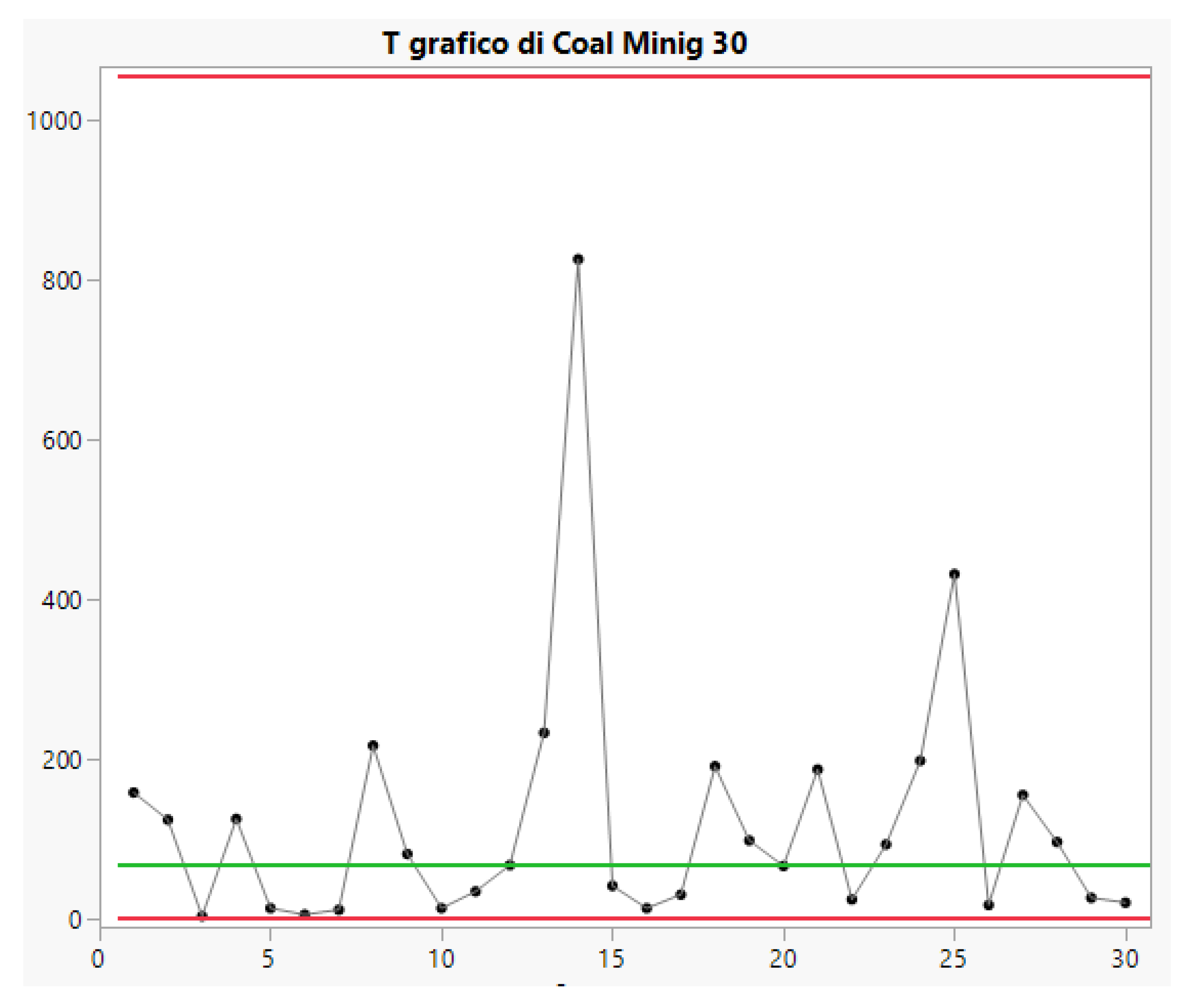

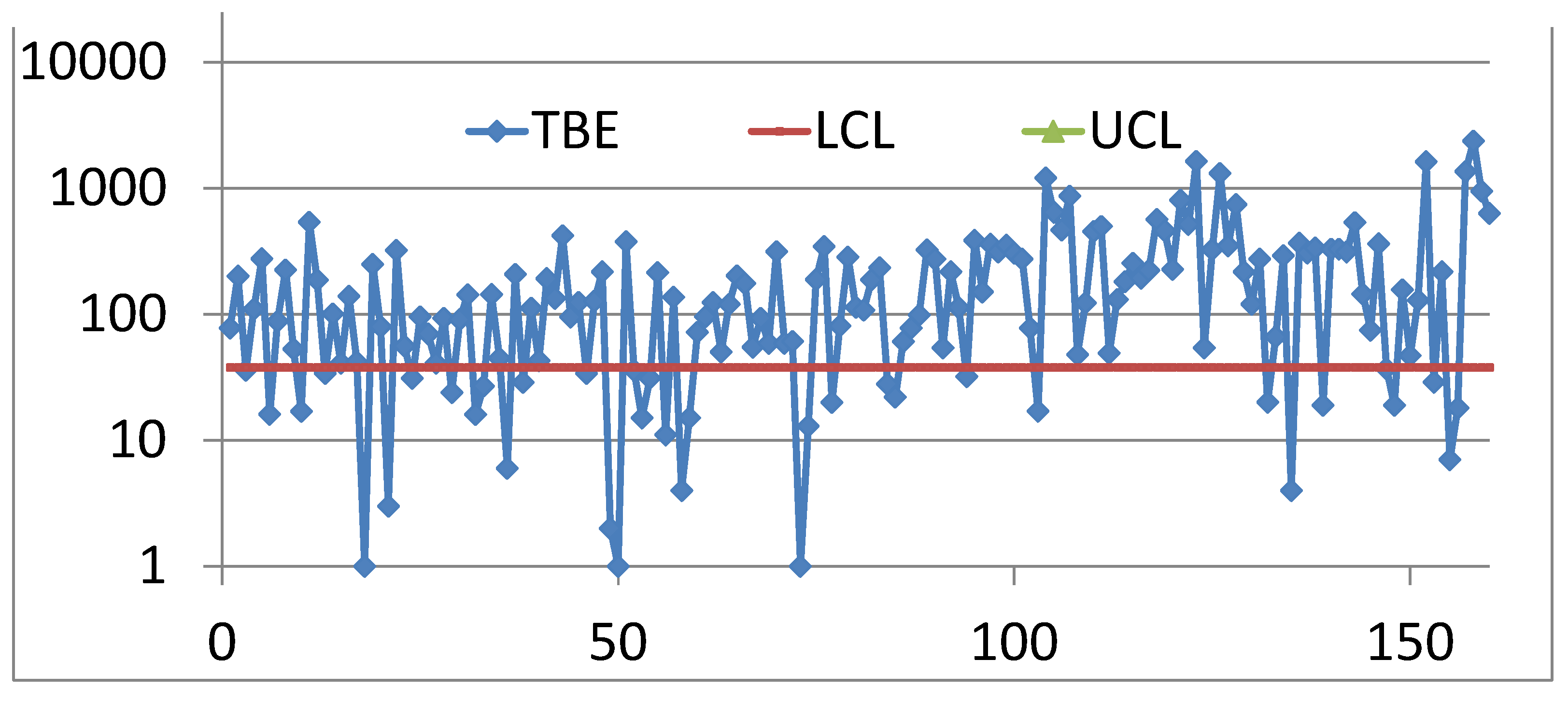

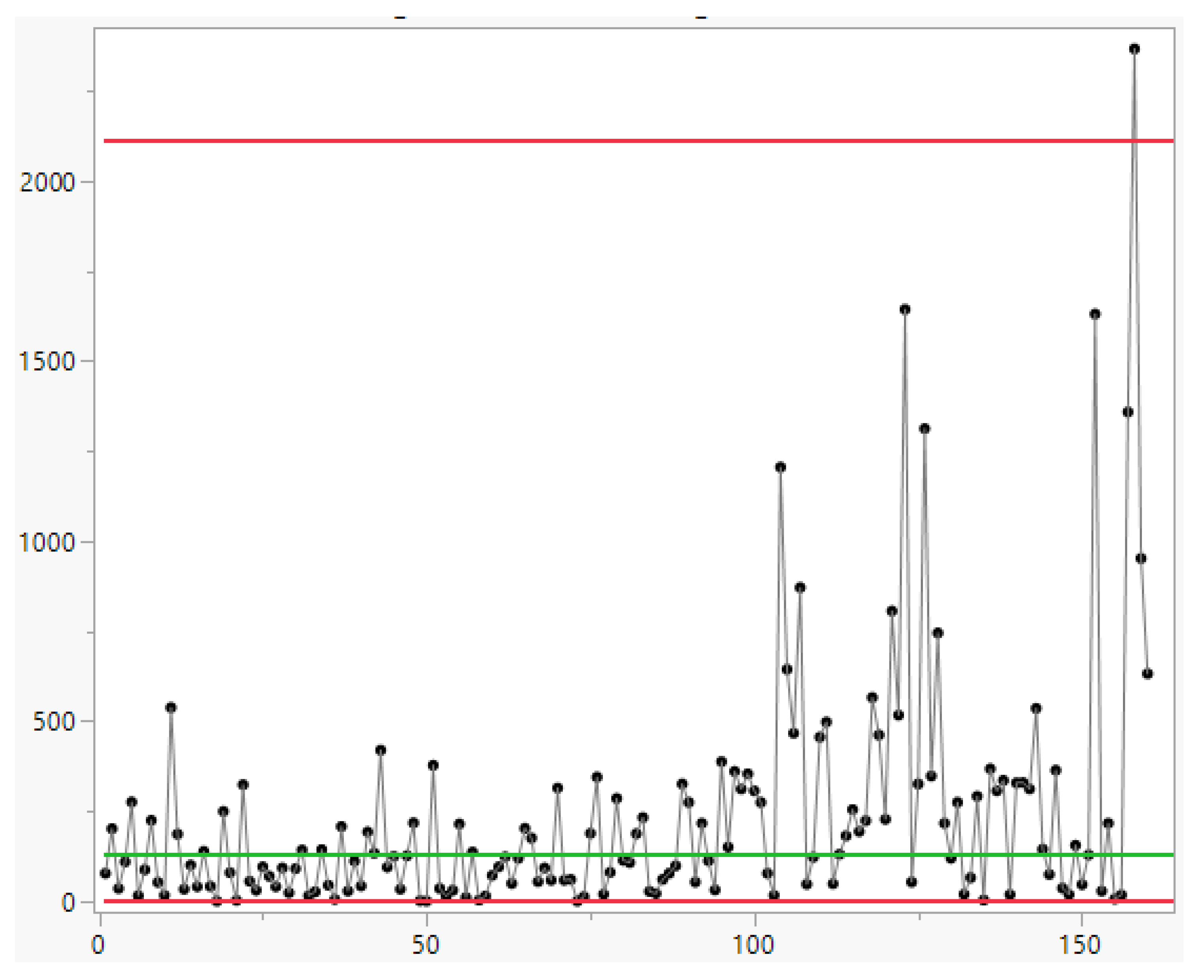

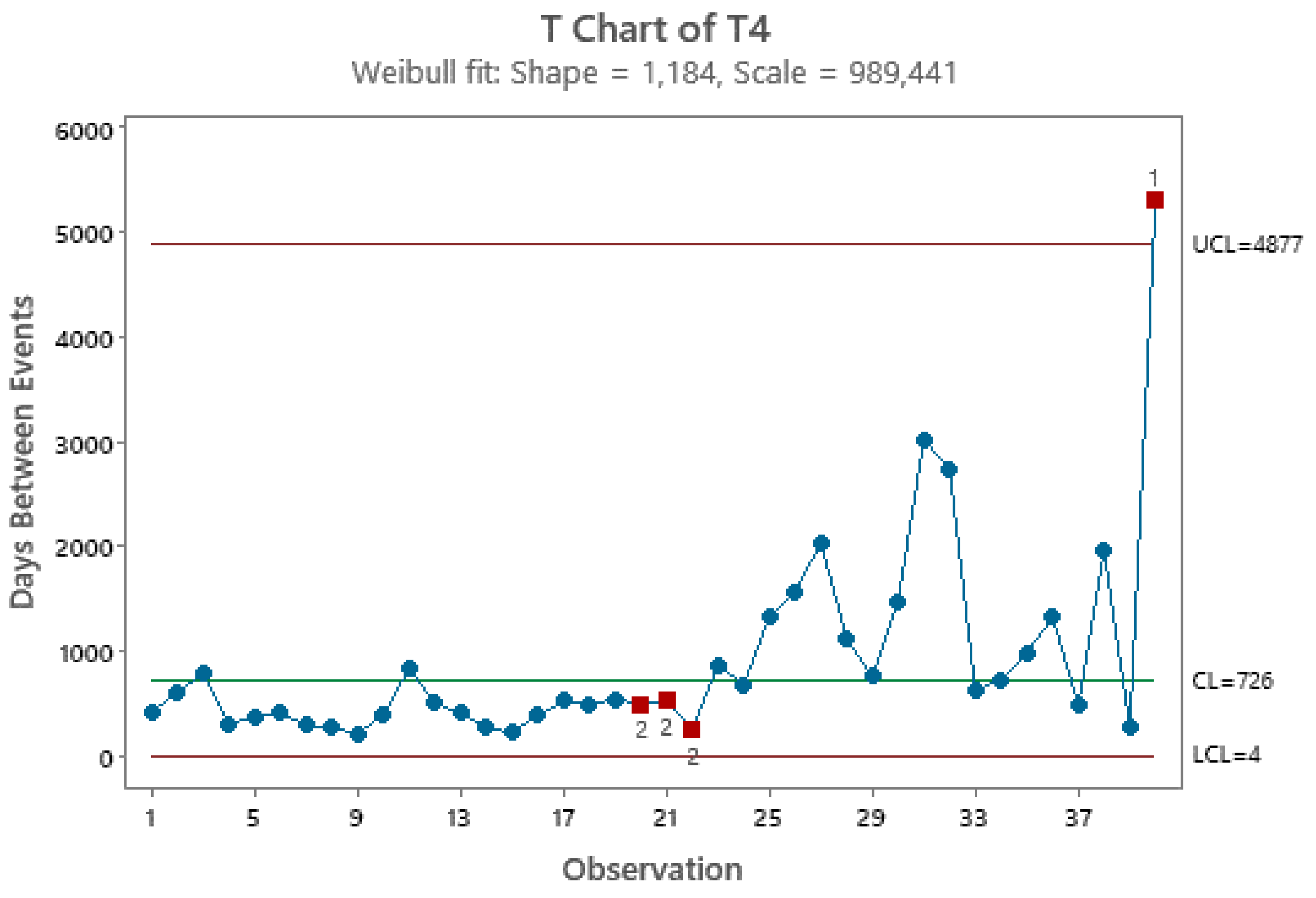

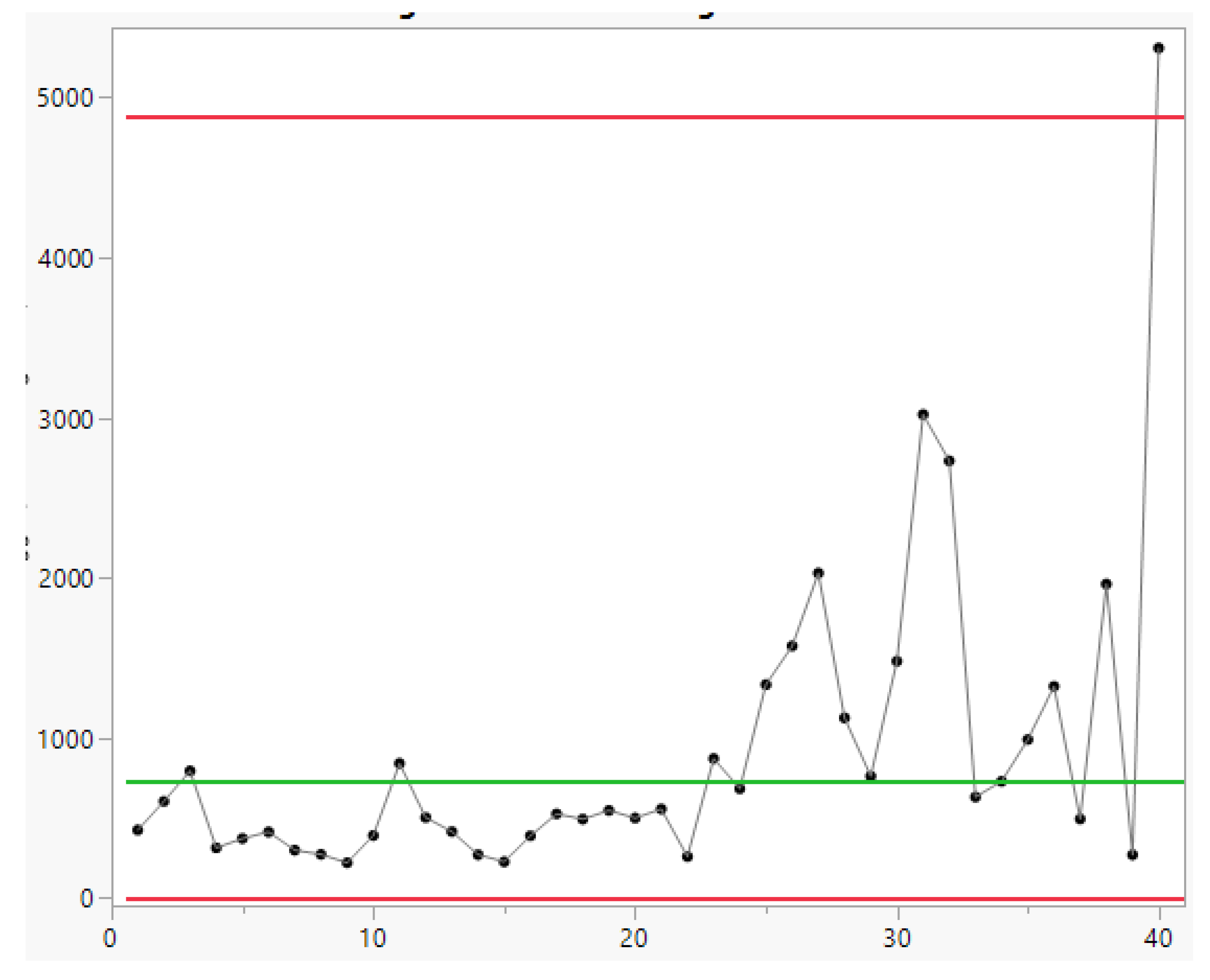

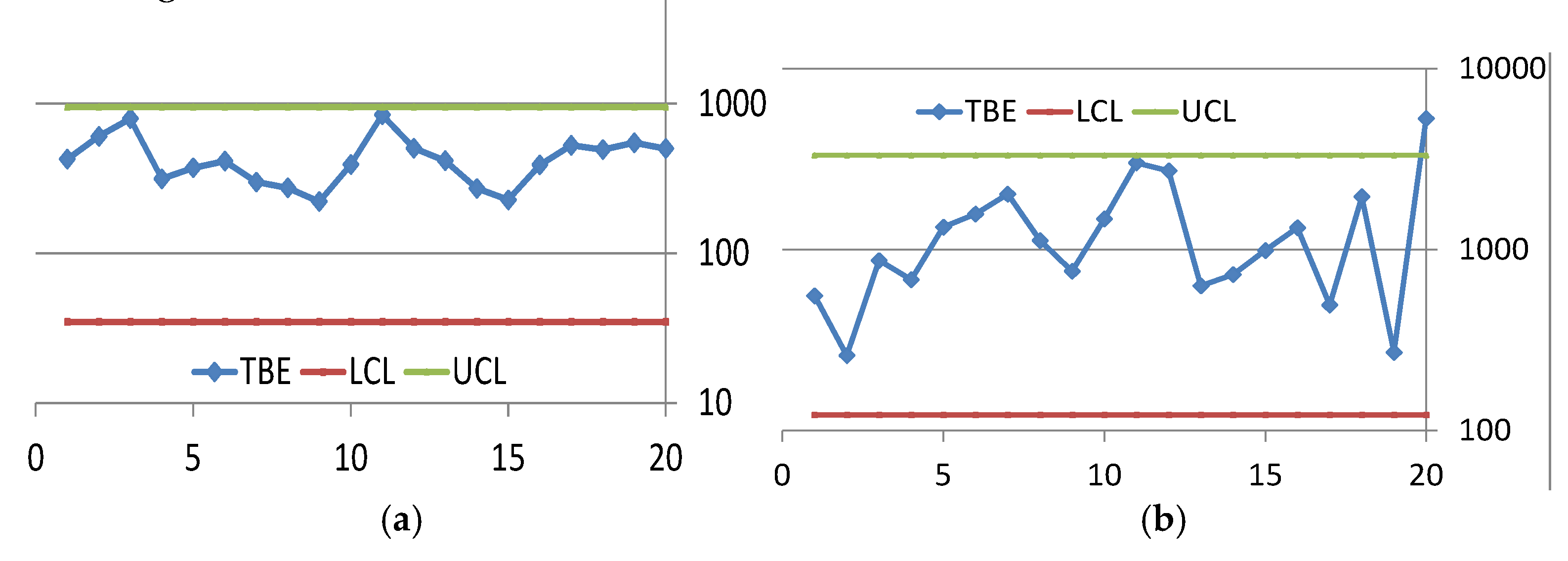

- … first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process, from which we estimate … the mean TBE approximately, 123 days; we name it θ0.

- … we apply the t4-chart… Thus, … converted by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times … the times until the fourth failure, used for monitoring the process to detect a change in the mean TBE.

3. Results

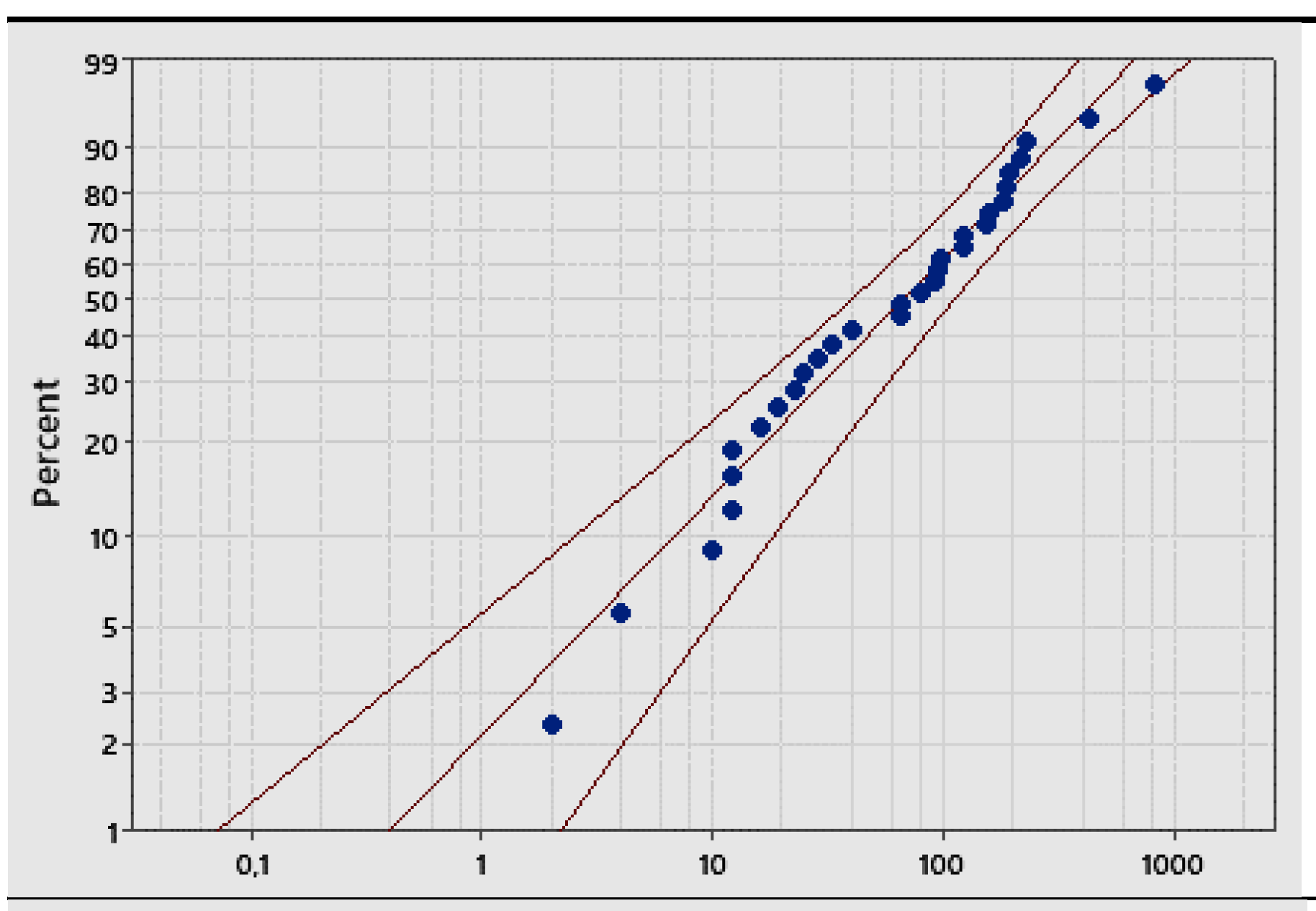

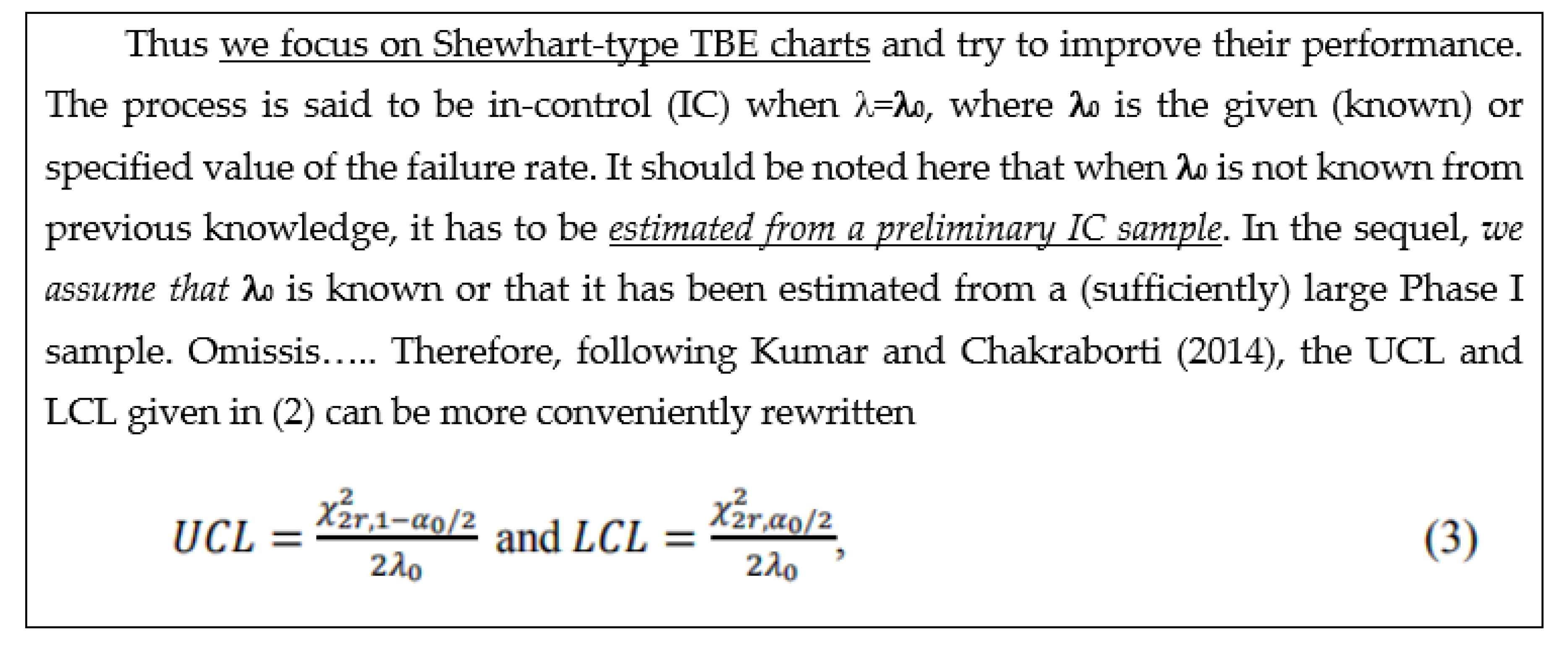

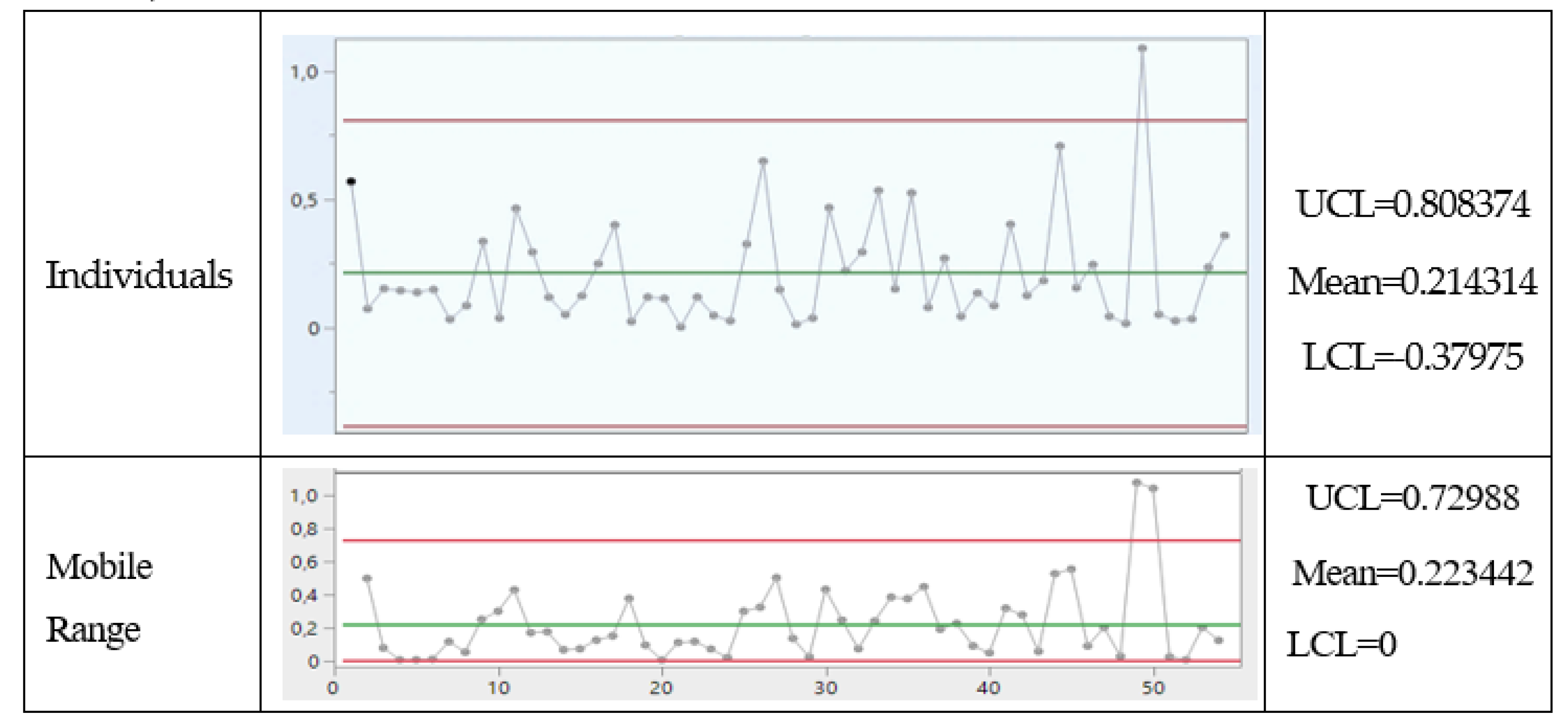

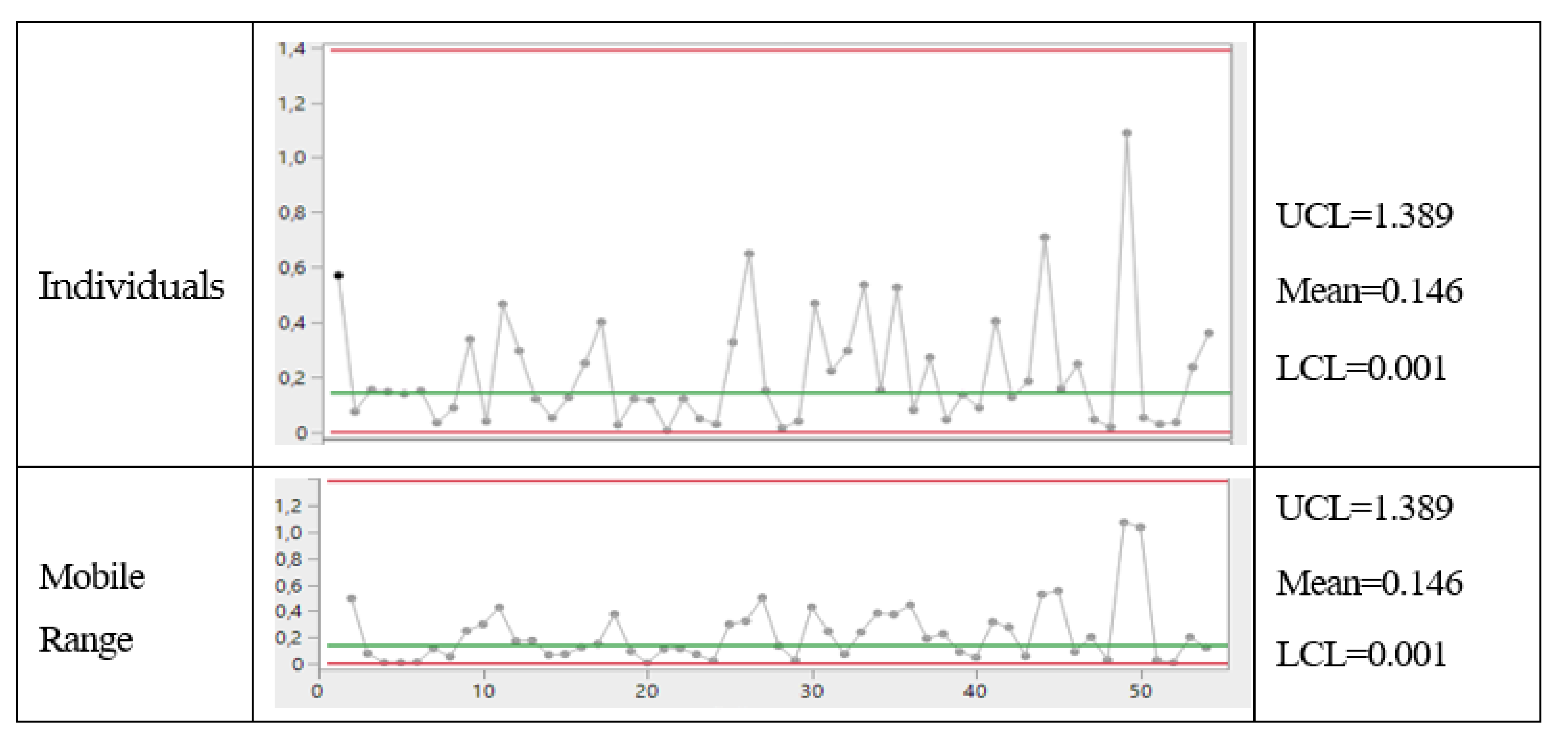

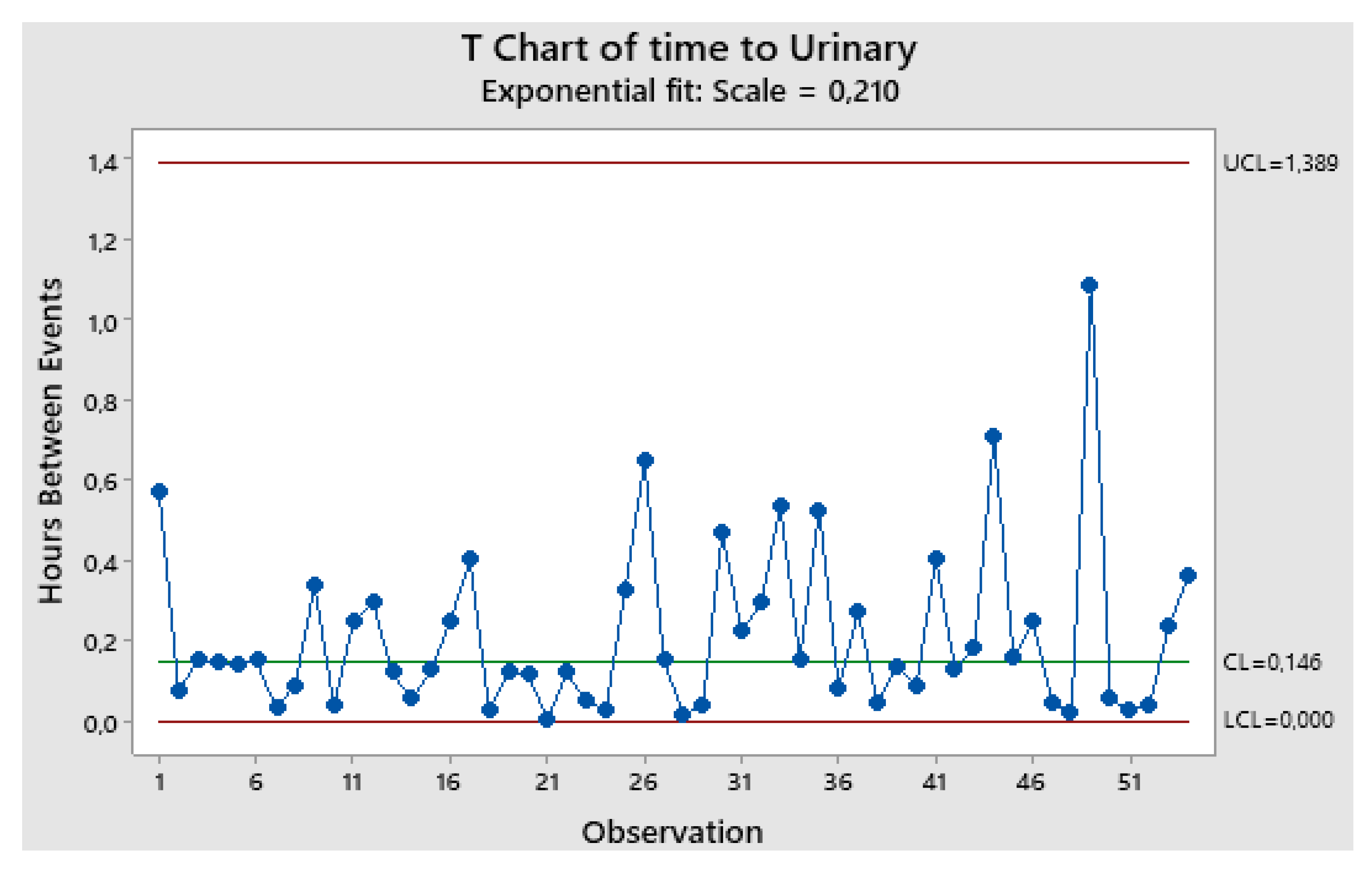

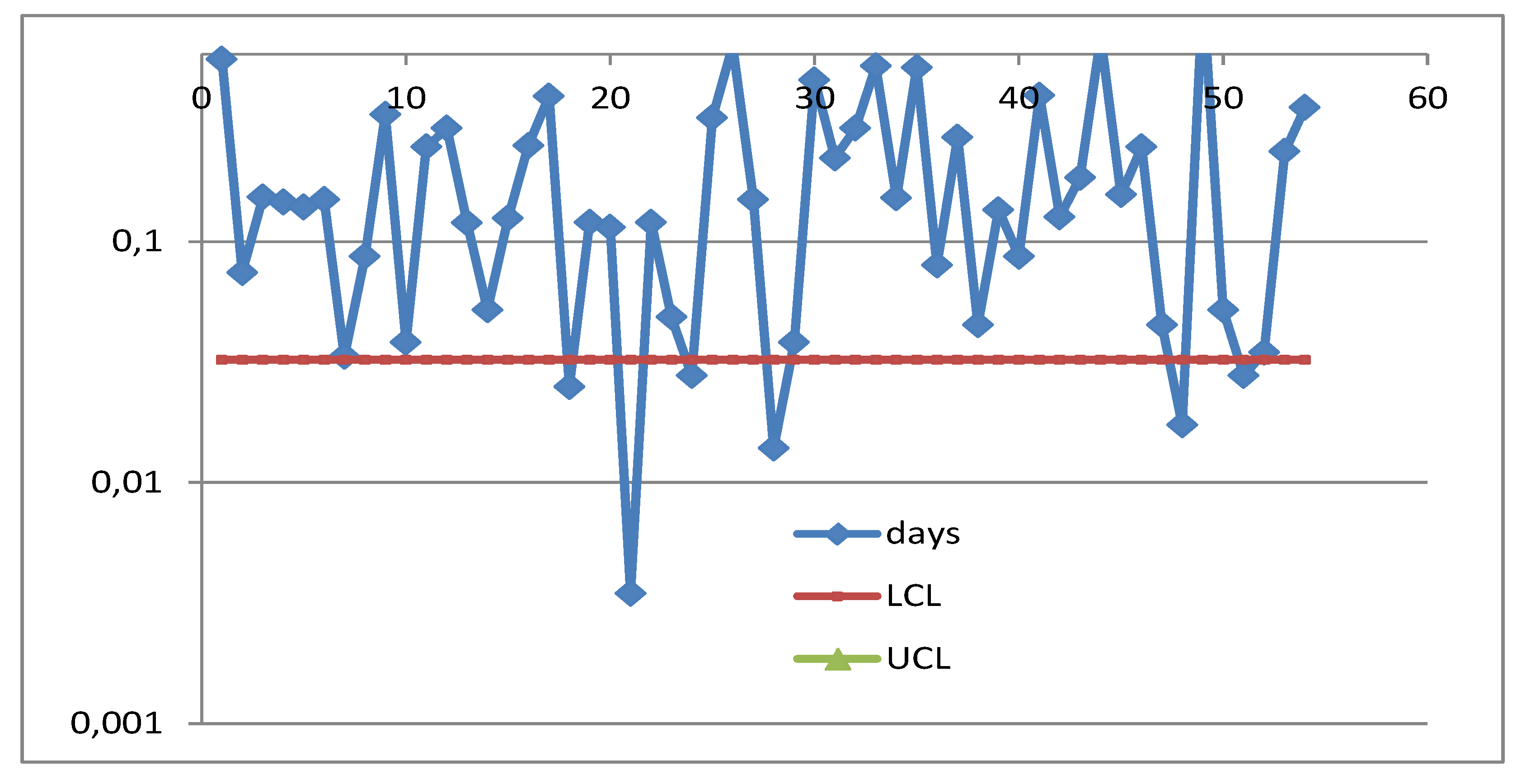

3.1. Control Charts for TBE Data. Phase I Analysis

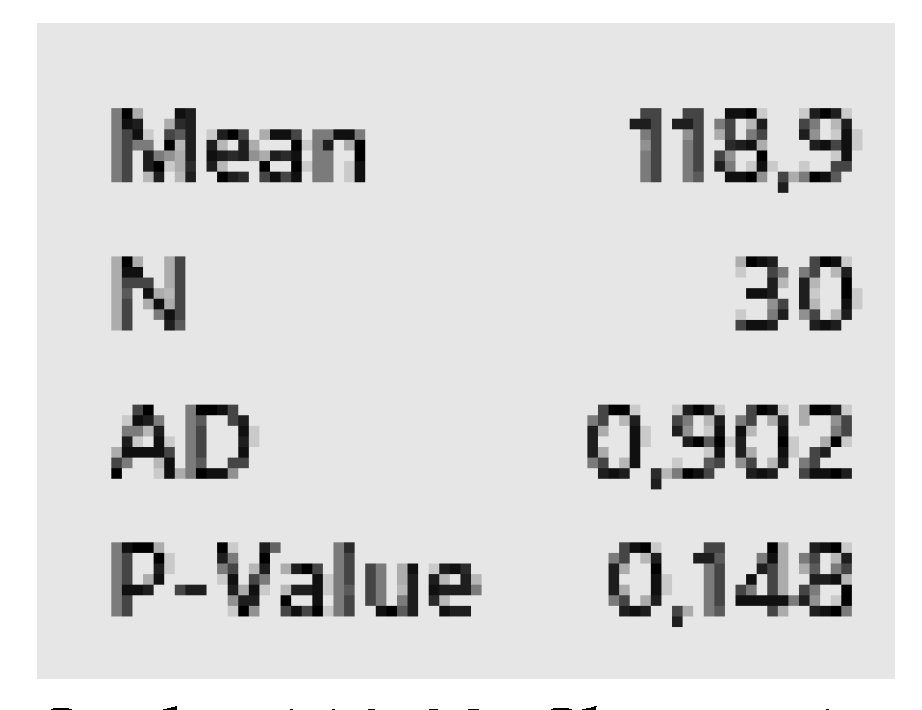

| Lu=0.286 versus the above value LCLZhang=0.268 |

Uu=966.6 versus the above value UCLZhang=1013.9 |

| Lu=0.286 and LCLZhang=0.268 | Uu=966.6 and UCLZhang=1013.9 |

|

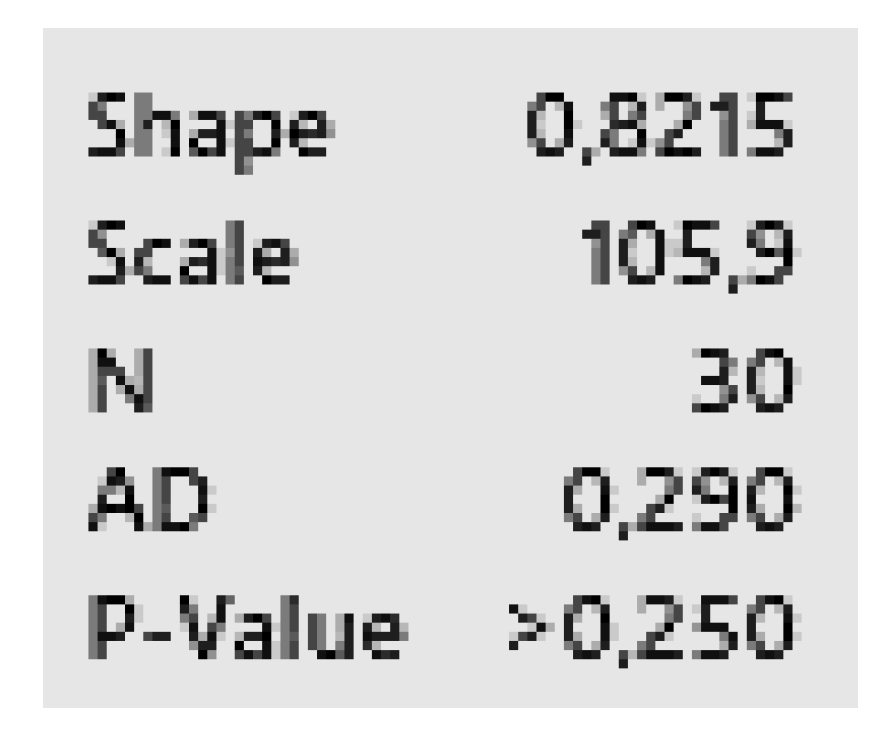

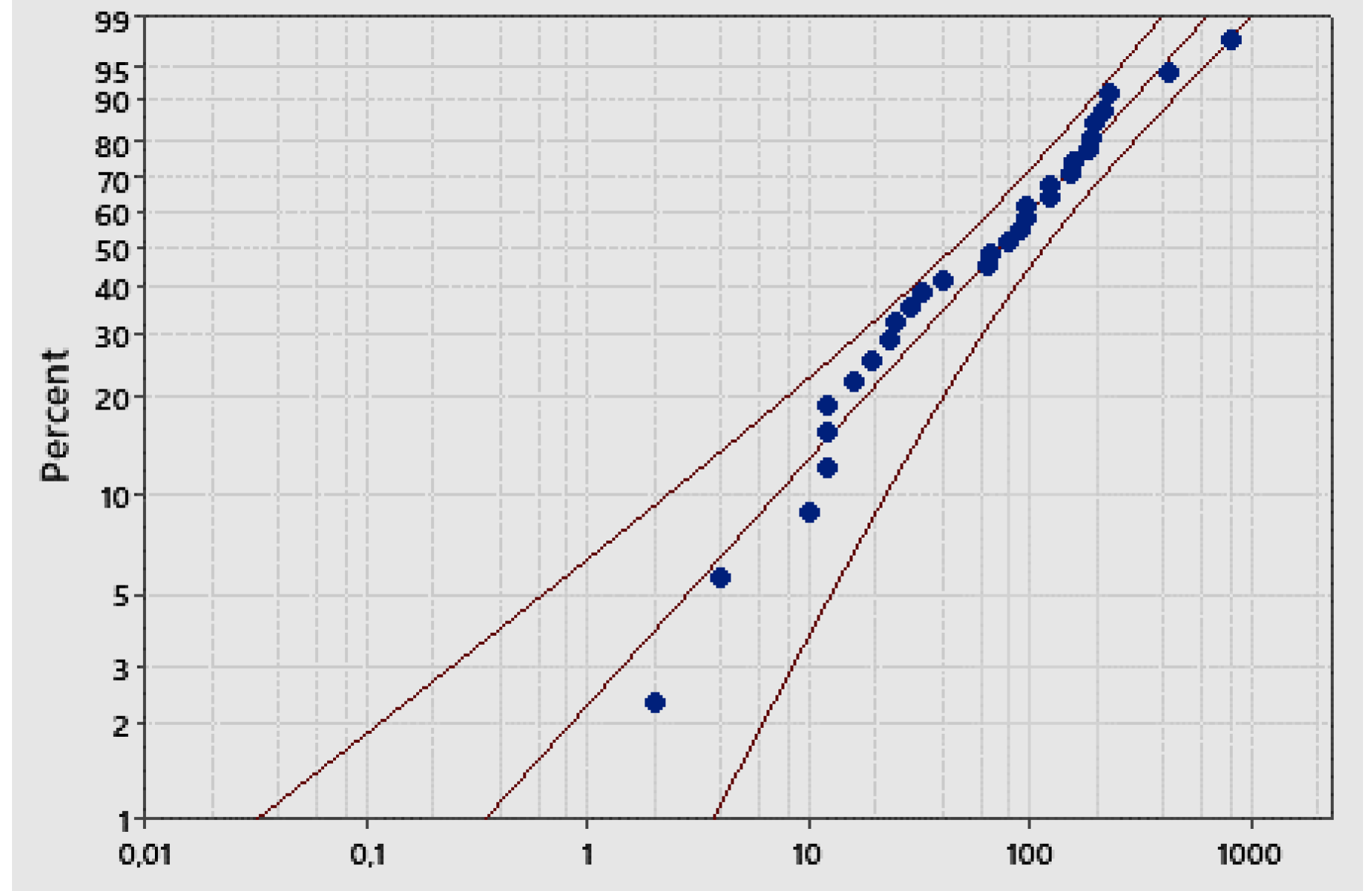

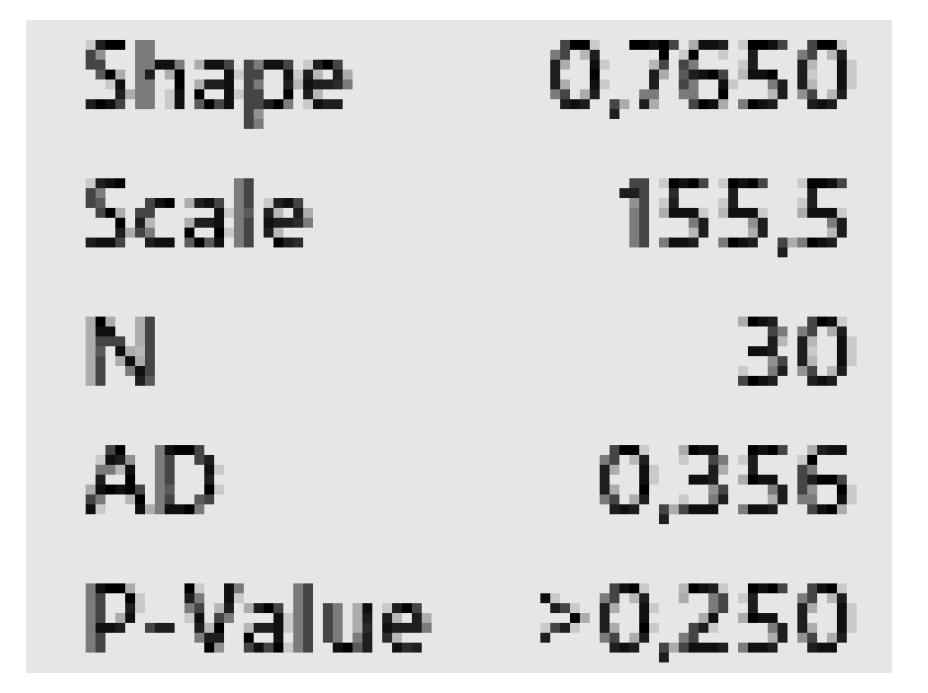

Weibull (95%) Scale: 105.94; Shape: 0.82 Scale: 105.94; Shape: 0.82 |

|

Gamma (95%) Scale: 155.47; Shape: 0.77 Scale: 155.47; Shape: 0.77 |

|

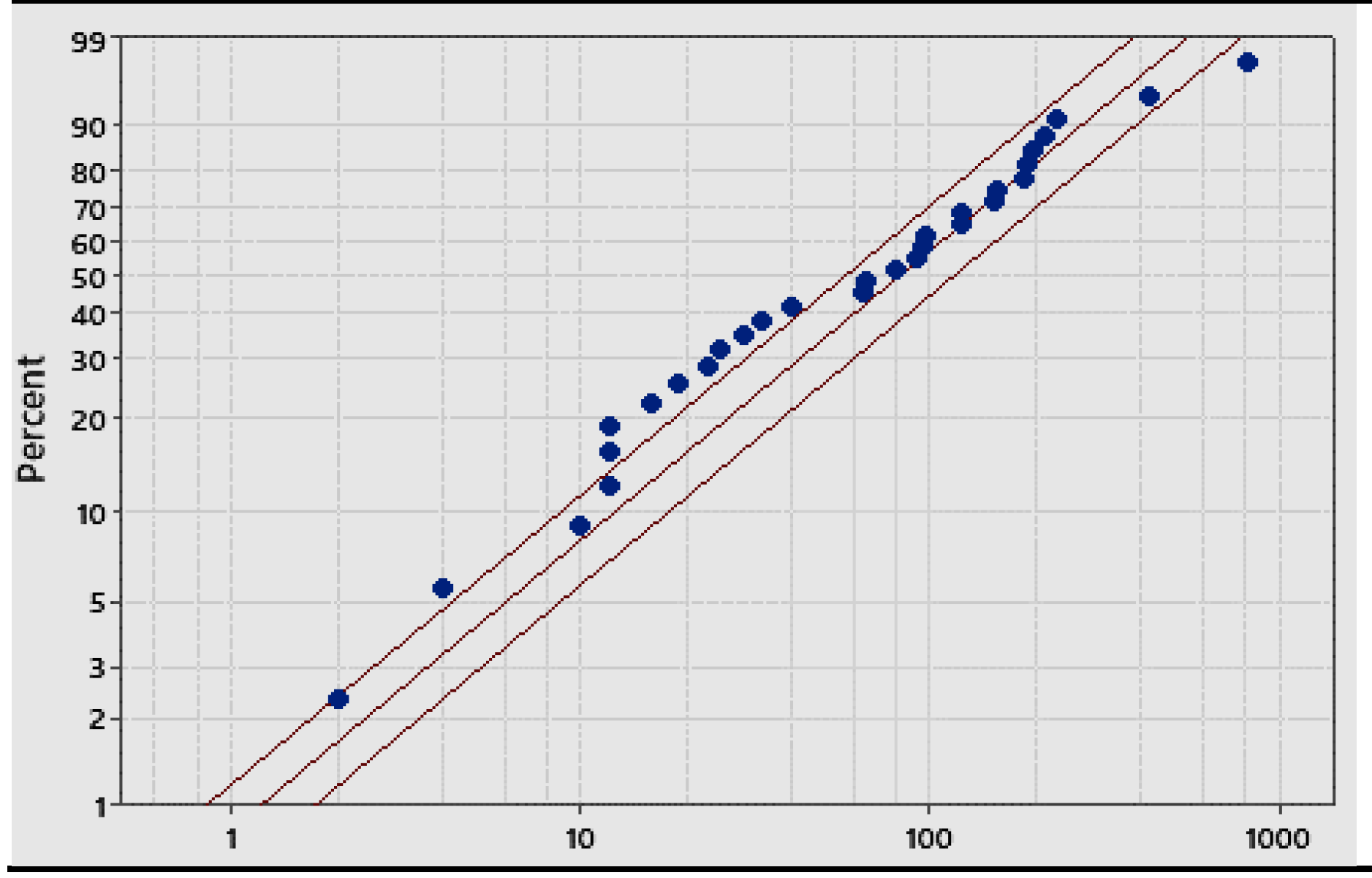

Exponential (95%) Scale: 118.93, Shape: 1 Scale: 118.93, Shape: 1 |

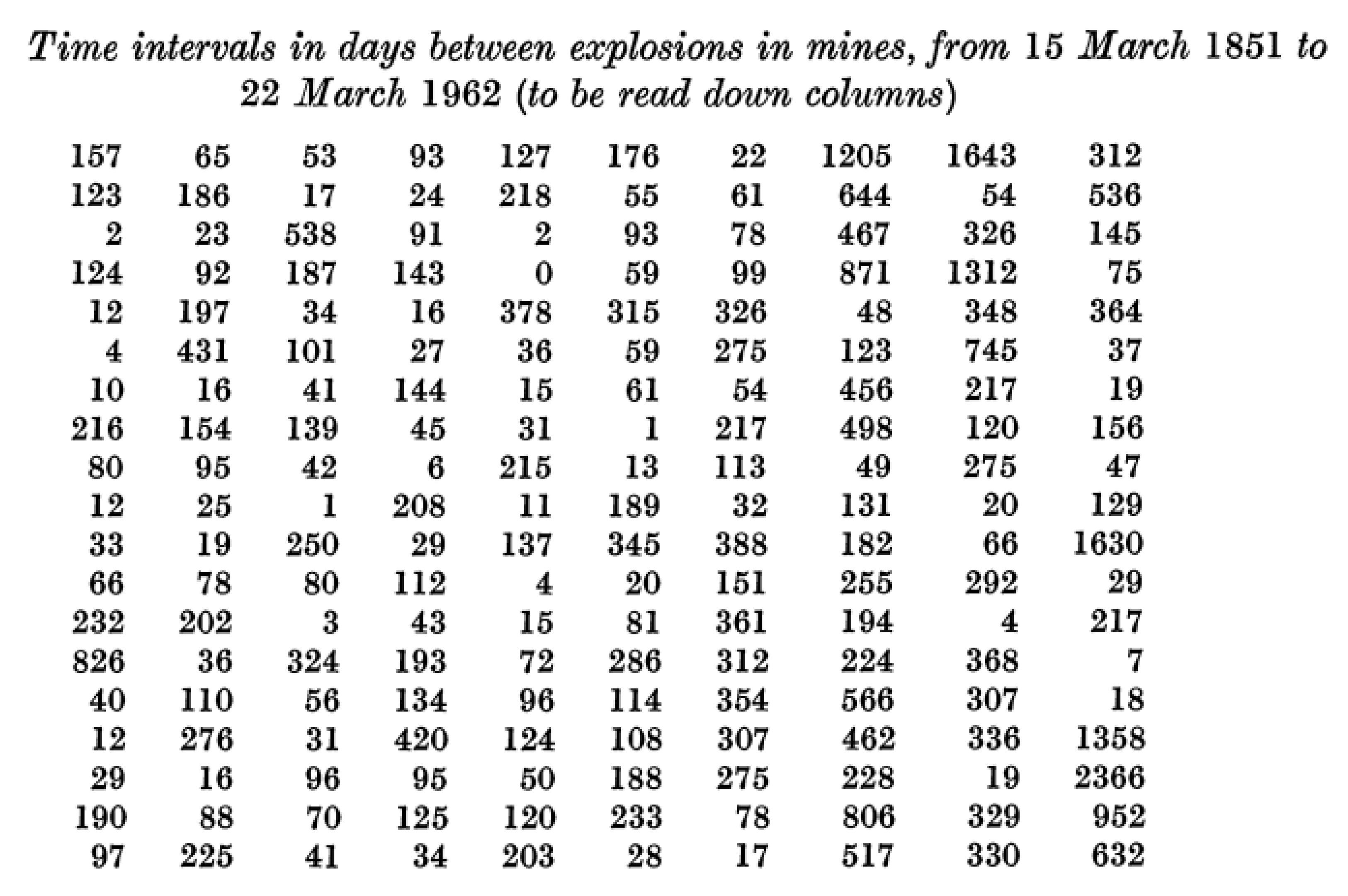

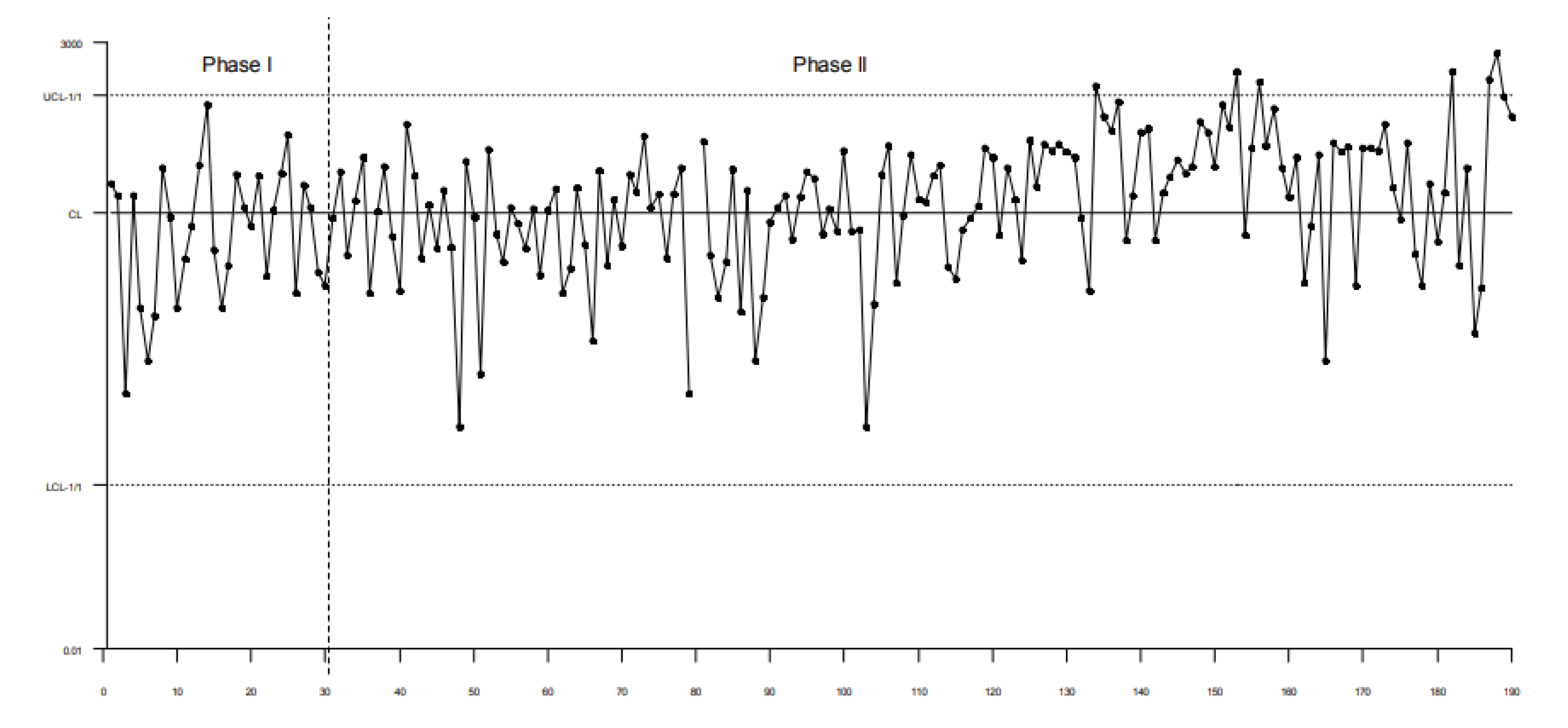

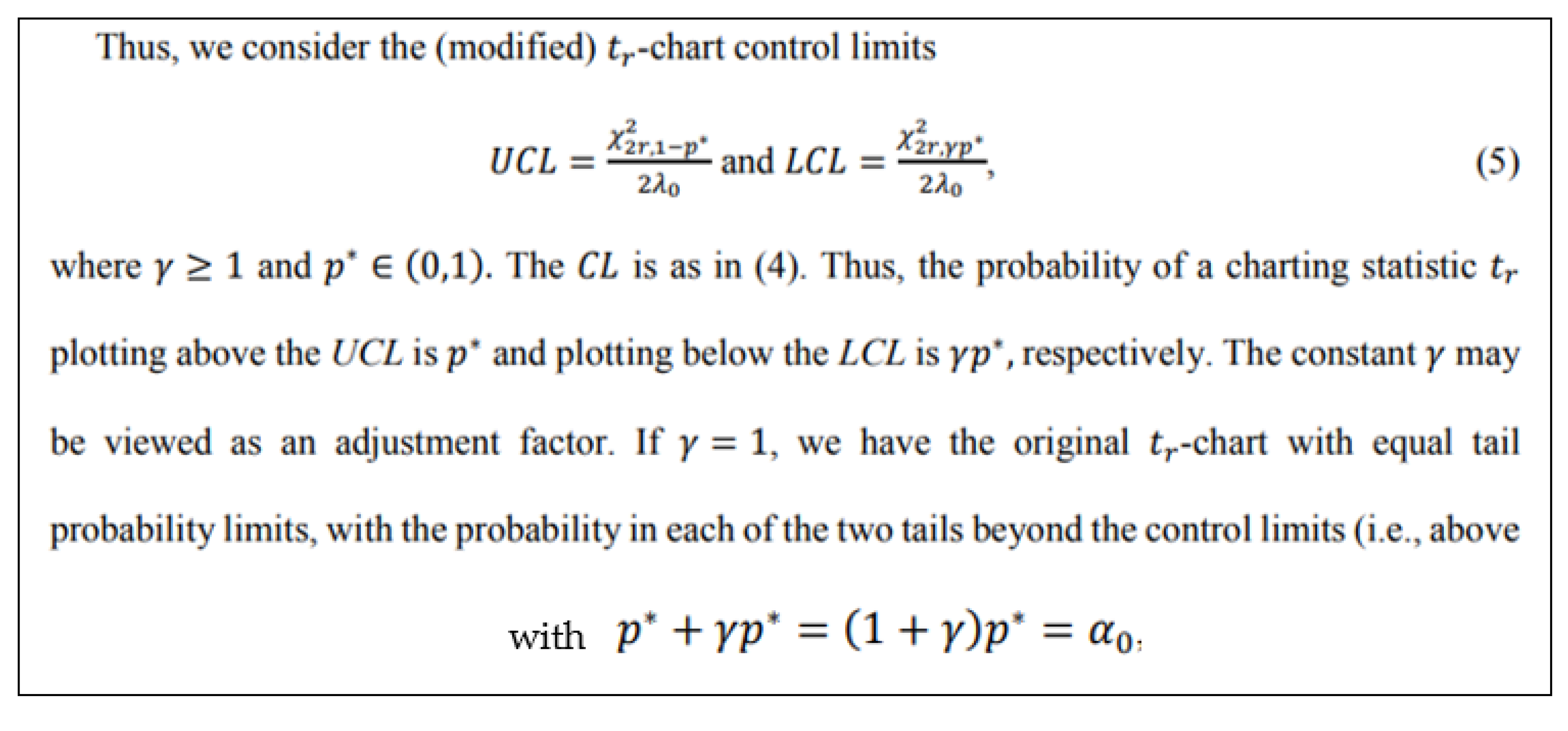

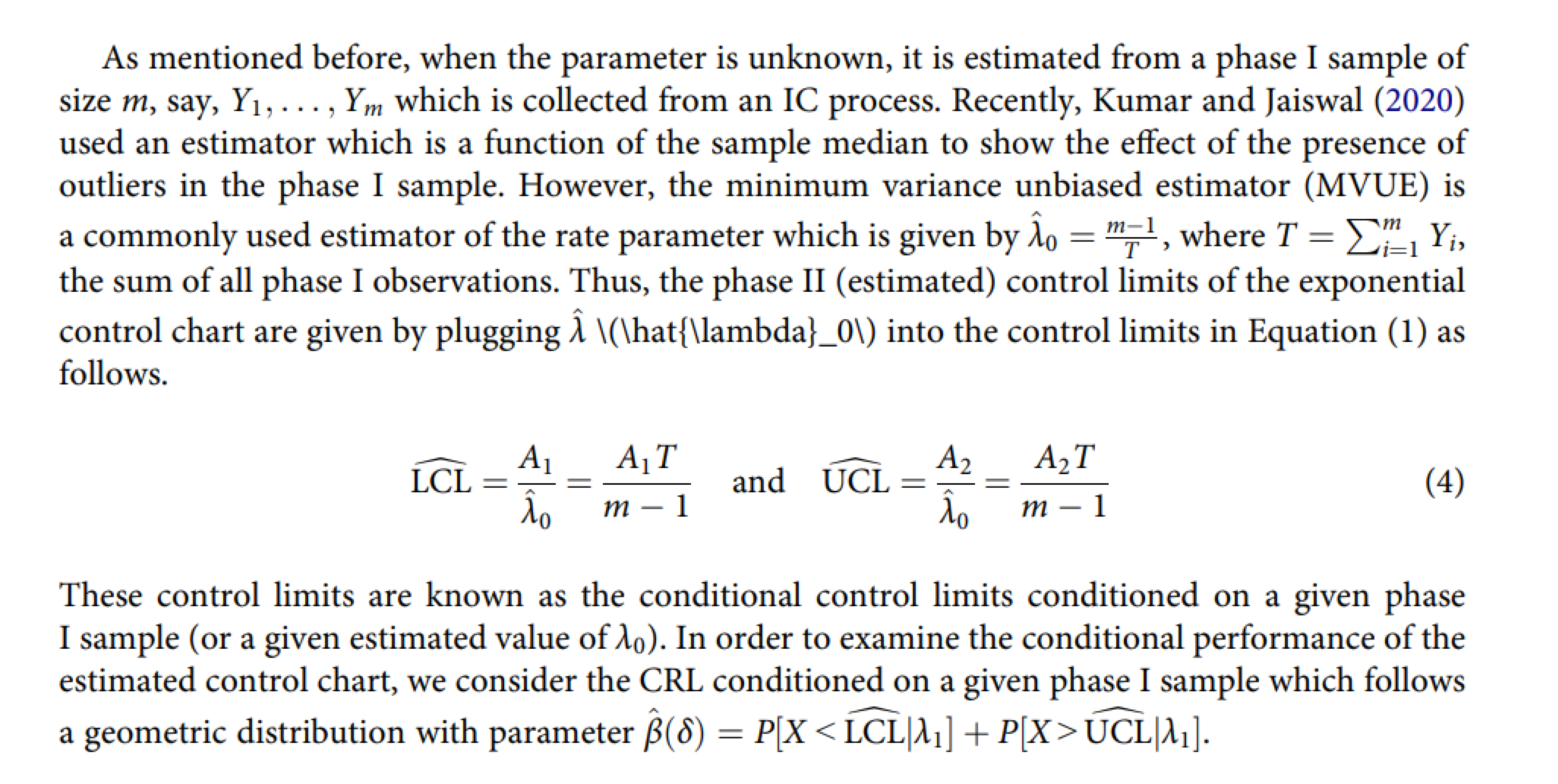

3.2. Control Charts for TBE Data. Phase II Analysis

- … first m=30 observations to be from the in-control process, from which we estimate … the mean TBE approximately, 123 days; we name it θ0.

- … we apply the t4-chart… Thus, … converted by accumulating a set of four consecutive failure times … the times until the fourth failure, used for monitoring the process to detect a change in the mean TBE.

- a)

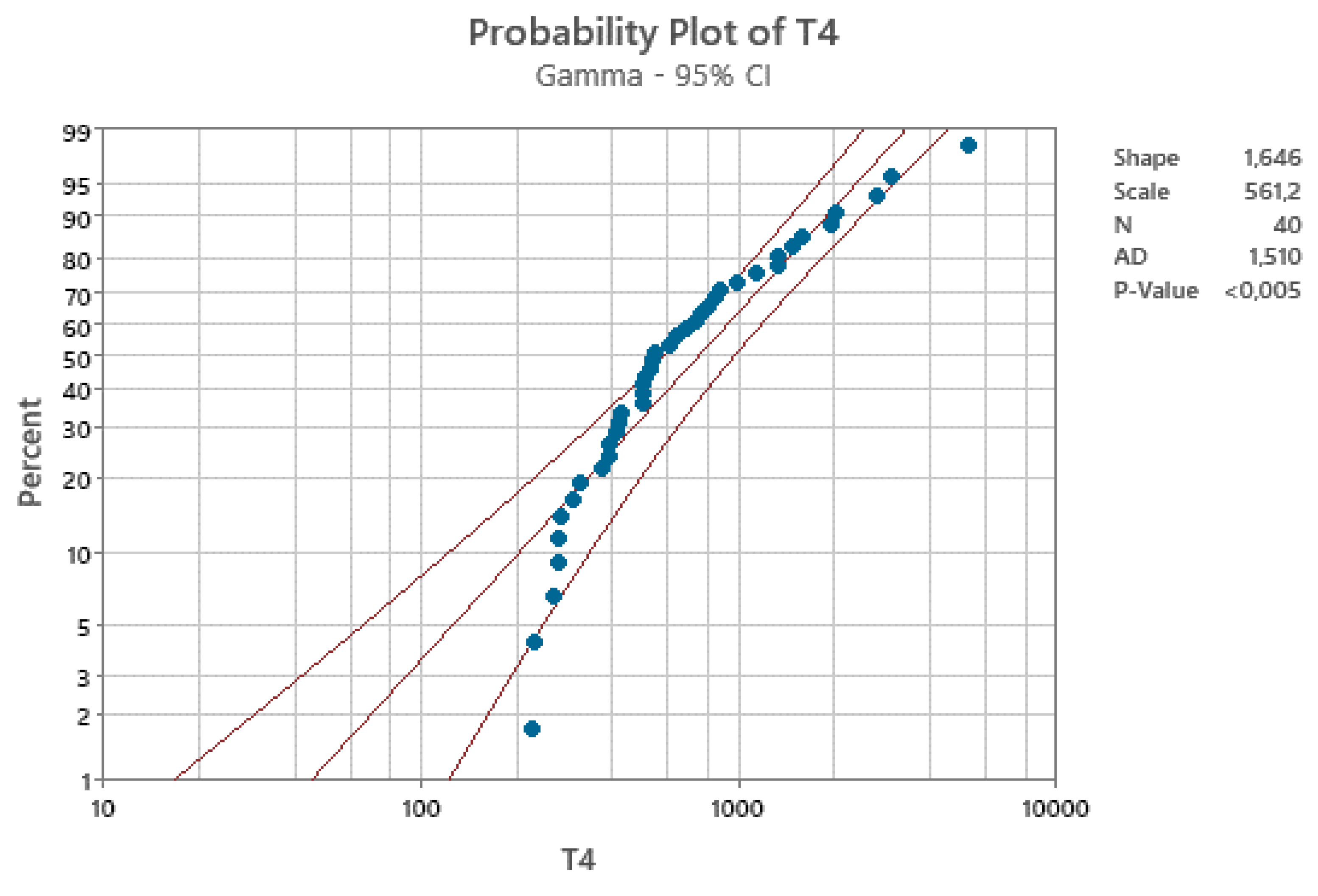

- the gamma (Erlang) distribution does not apply, with CL=95%

- b)

- then, the formulae in the Excerpt 11 cannot be applied.

- c)

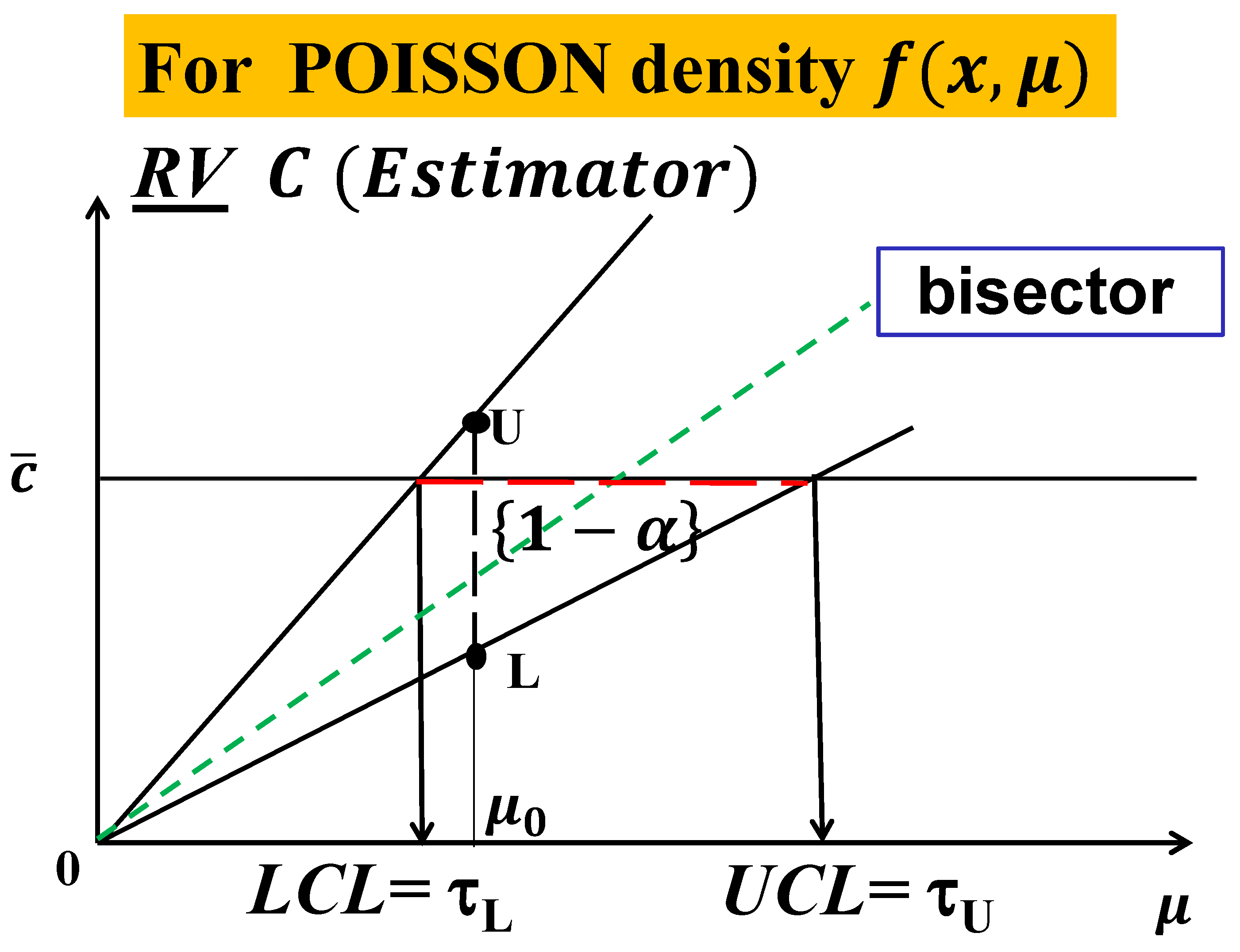

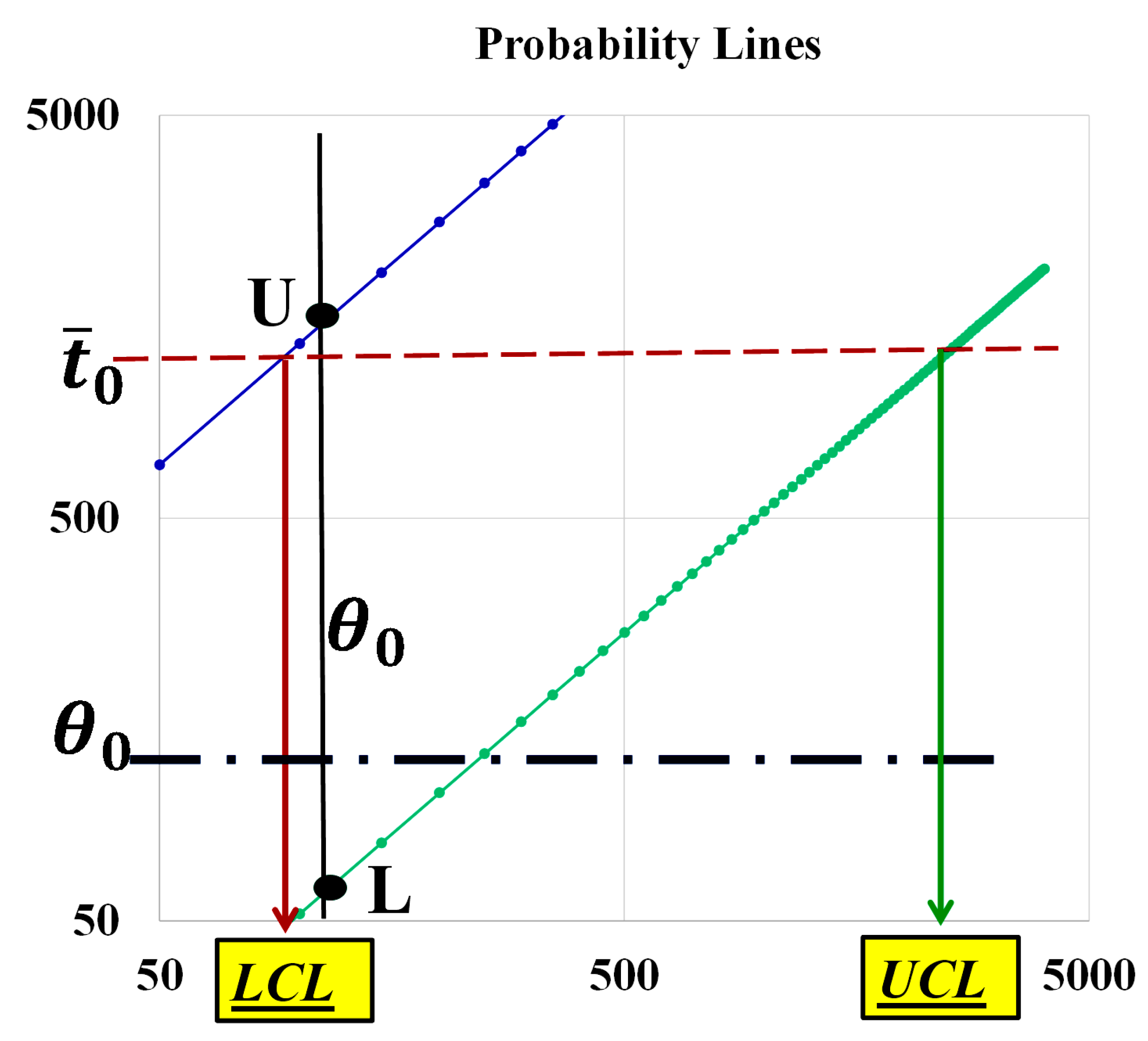

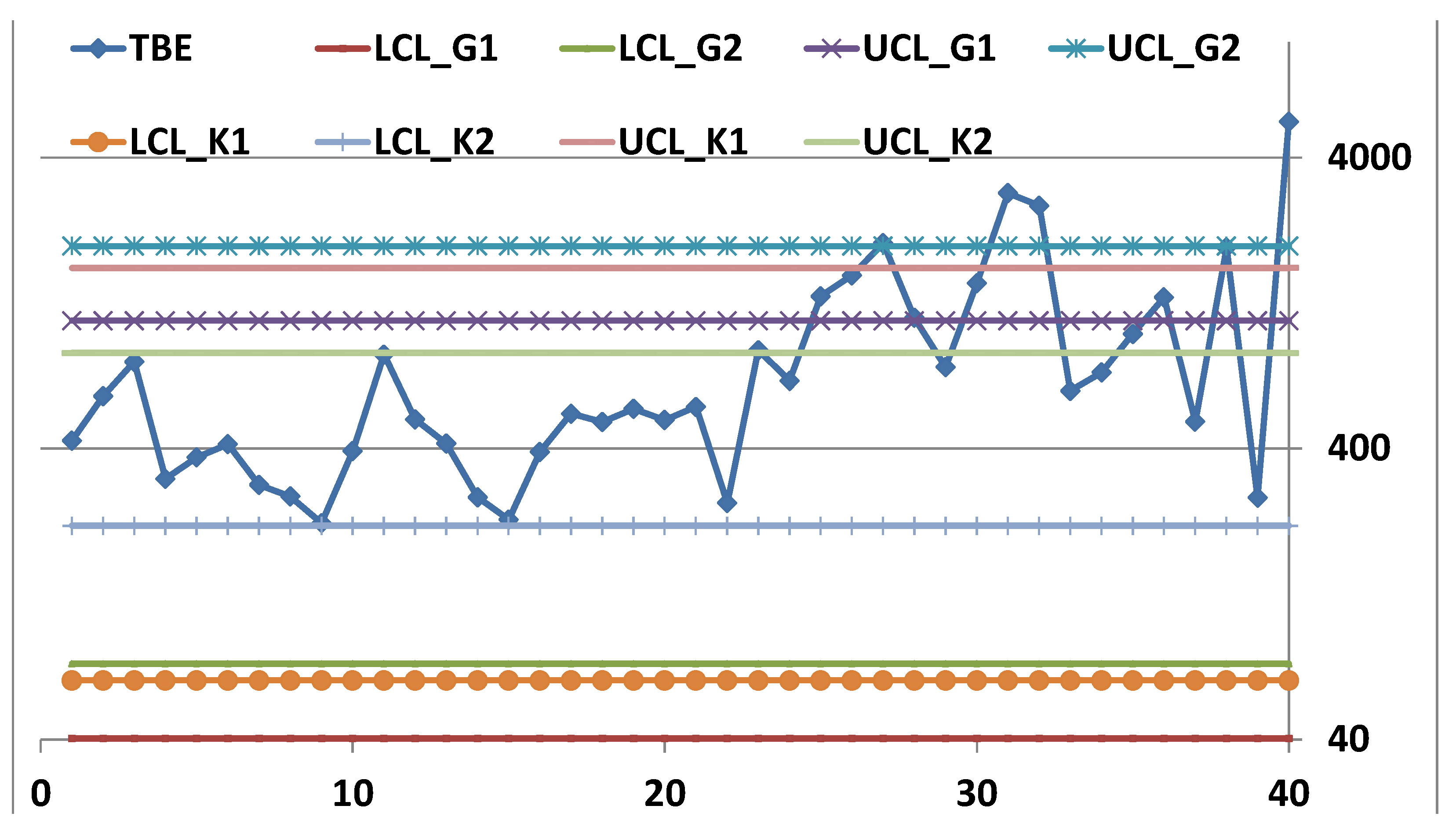

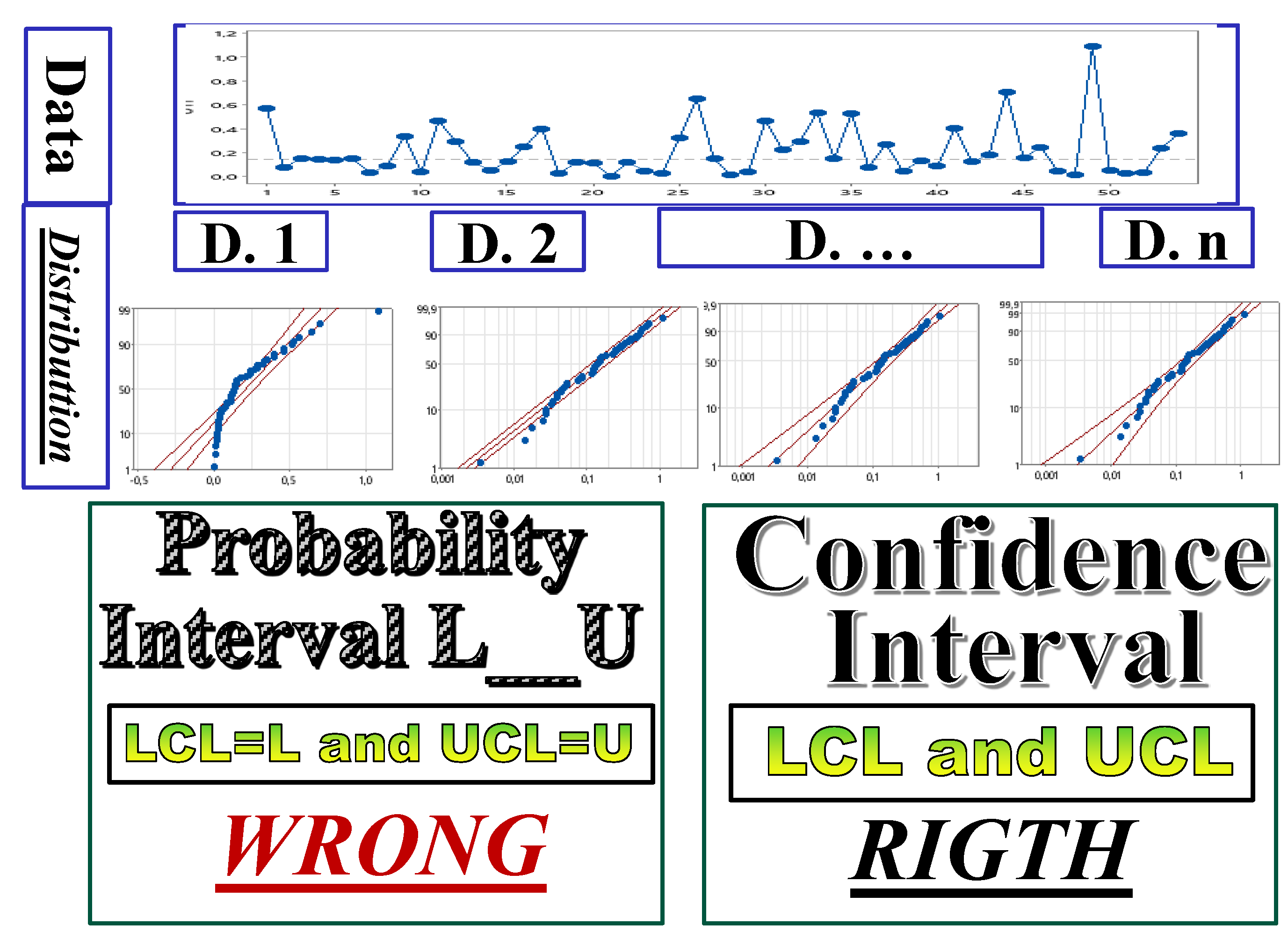

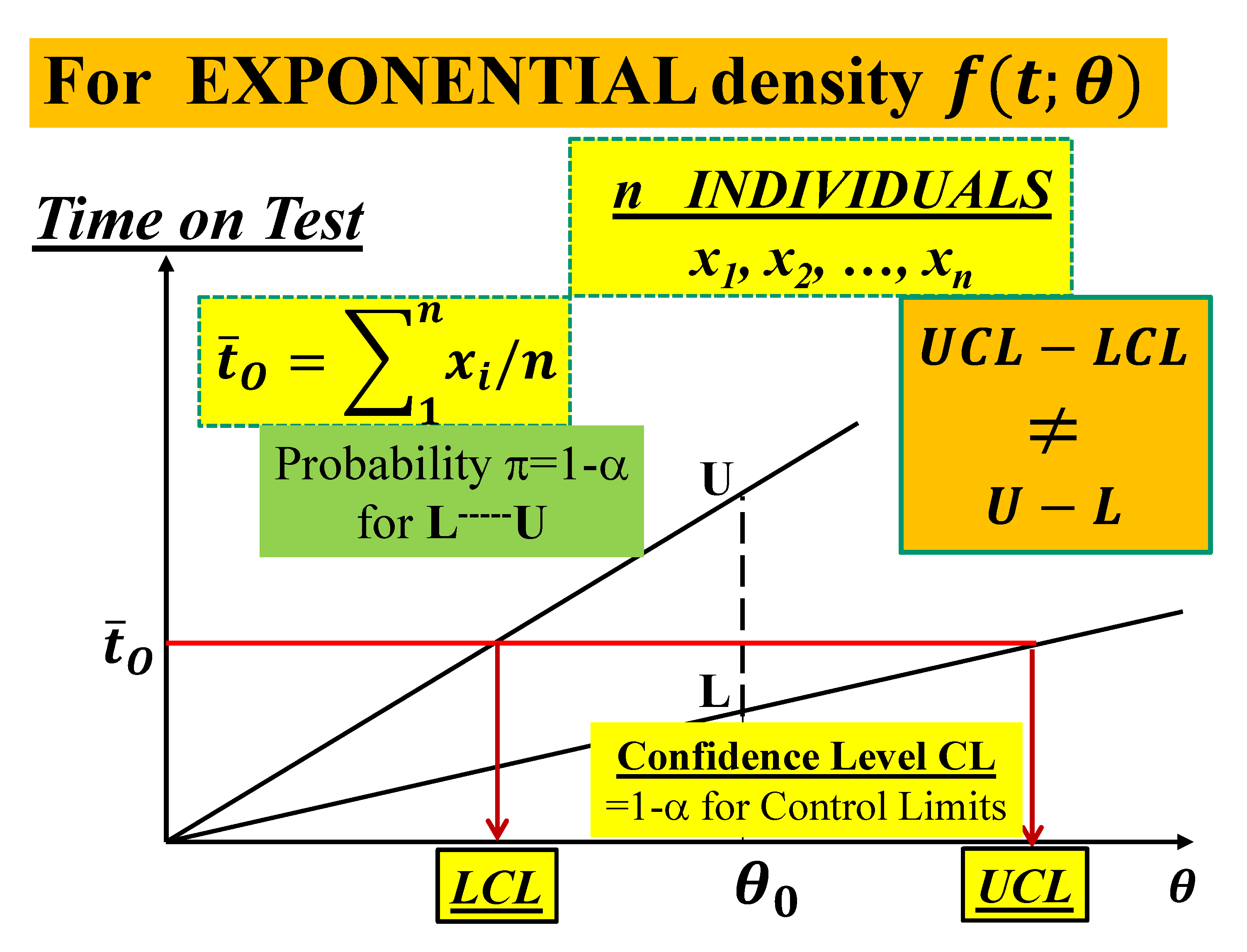

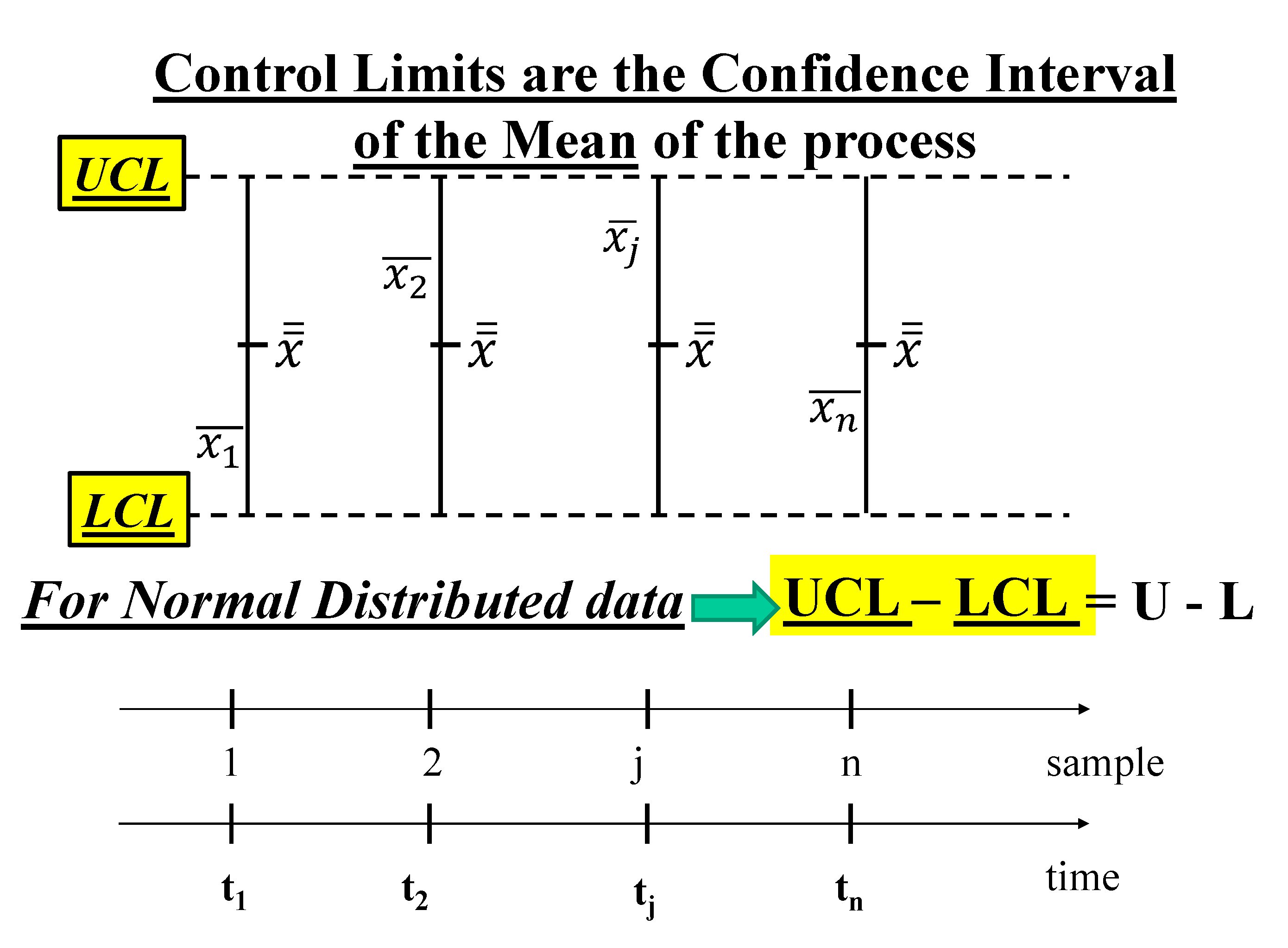

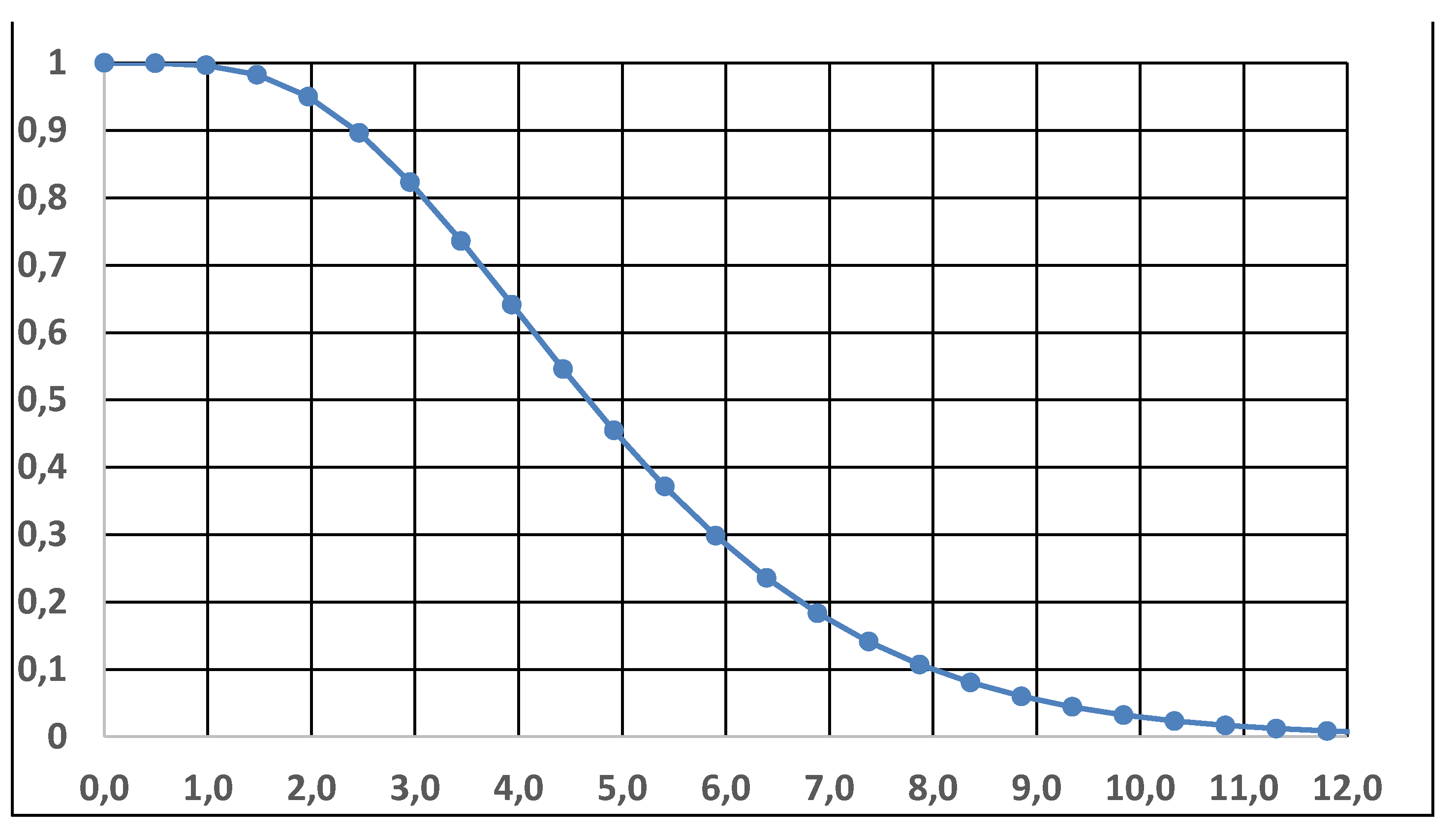

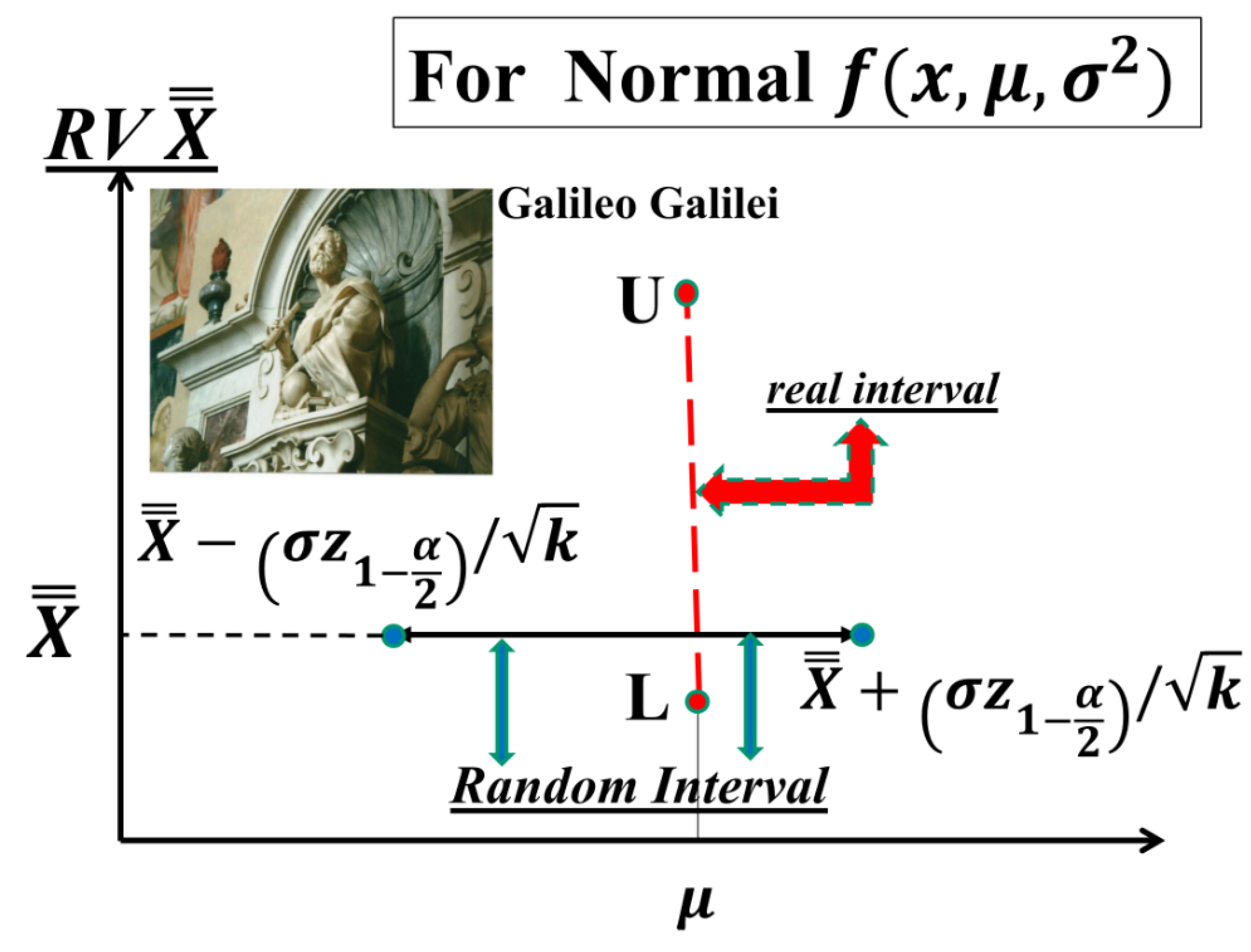

- the formulae, in their paper, and are generated by the confusion (of the authors) between LCL and L and UCL and U, as you can see in the Figure 9, based on the non-applicable Gamma distribution; you see the vertical line intercepting the two probability lines in the points L and U such that and versus the horizontal line, at intercepting the two lines at LCL and UCL.

| LCL_K1 | LCL_K2 | UCL_K1 | UCL_K2 | LCL_G1 | LCL_G2 | UCL_G1 | UCL_G2 |

| 63.95 | 217.13 | 1669.28 | 852.92 | 40.38 | 72.91 | 1100.37 | 1986.96 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Zameer Abbas et al., (30 June 2024): “Efficient and distribution-free charts for monitoring the process location for individual observations”, Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation,

- Marcus B. Perry (June 2024) [University of Alabama 674 Citations] “Joint monitoring of location and scale for modern univariate processes”, Journal of Quality Technology.

- E. Afuecheta et al., (2023) “A compound exponential distribution with application to control charts”, Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics [the authors use data of Santiago&Smith (Appendix C) and erroneously find that the UTI process IC].

- N. Kumar (2019), “Conditional analysis of Phase II exponential chart for monitoring times to an event”, Quality Technology & Quantitative Management

- N. Kumar (2021), “Statistical design of phase II exponential chart with estimated parameters under the unconditional and conditional perspectives using exact distribution of median run length”, Quality Technology & Quantitative Management

- S. Chakraborti et al. (2021), “Phase II exponential charts for monitoring time between events data: performance analysis using exact conditional average time to signal distribution”, Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation

- S. Chakraborti et al. (2025), “Dynamic Risk-Adjusted Monitoring of Time Between Events: Applications of NHPP in Pipeline Accident Surveillance”, downloaded from RG

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCL, UCL | Control Limits of the Control Charts (CCs) |

| L, U | Probability Limits related to a probability 1-α |

| θ | Parameter of the Exponential Distribution |

| θL-----θU | Confidence Interval of the parameter θ |

| RIT | Reliability Integral Theory |

Appendix A

| UTI | UTI | UTI | UTI | UTI | UTI | ||||||

| 1 | 0.46014 | 11 | 0.46530 | 21 | 0.00347 | 31 | 0.22222 | 41 | 0.40347 | 51 | 0.02778 |

| 2 | 0.07431 | 12 | 0.29514 | 22 | 0.12014 | 32 | 0.29514 | 42 | 0.12639 | 52 | 0.03472 |

| 3 | 0.15278 | 13 | 0.11944 | 23 | 0.04861 | 33 | 0.53472 | 43 | 0.18403 | 53 | 0.23611 |

| 4 | 0.14583 | 14 | 0.05208 | 24 | 0.02778 | 34 | 0.15139 | 44 | 0.70833 | 54 | 0.35972 |

| 5 | 0.13889 | 15 | 0.12500 | 25 | 0.32639 | 35 | 0.52569 | 45 | 0.15625 | ||

| 6 | 0.14931 | 16 | 0.25000 | 26 | 0.64931 | 36 | 0.07986 | 46 | 0.24653 | ||

| 7 | 0.03333 | 17 | 0.40069 | 27 | 0.14931 | 37 | 0.27083 | 47 | 0.04514 | ||

| 8 | 0.08681 | 18 | 0.02500 | 28 | 0.01389 | 38 | 0.04514 | 48 | 0.01736 | ||

| 9 | 0.33681 | 19 | 0.12014 | 29 | 0.03819 | 39 | 0.13542 | 49 | 1.08889 | ||

| 10 | 0.03819 | 20 | 0.11458 | 30 | 0.46806 | 40 | 0.08681 | 50 | 0.05208 |

Appendix B

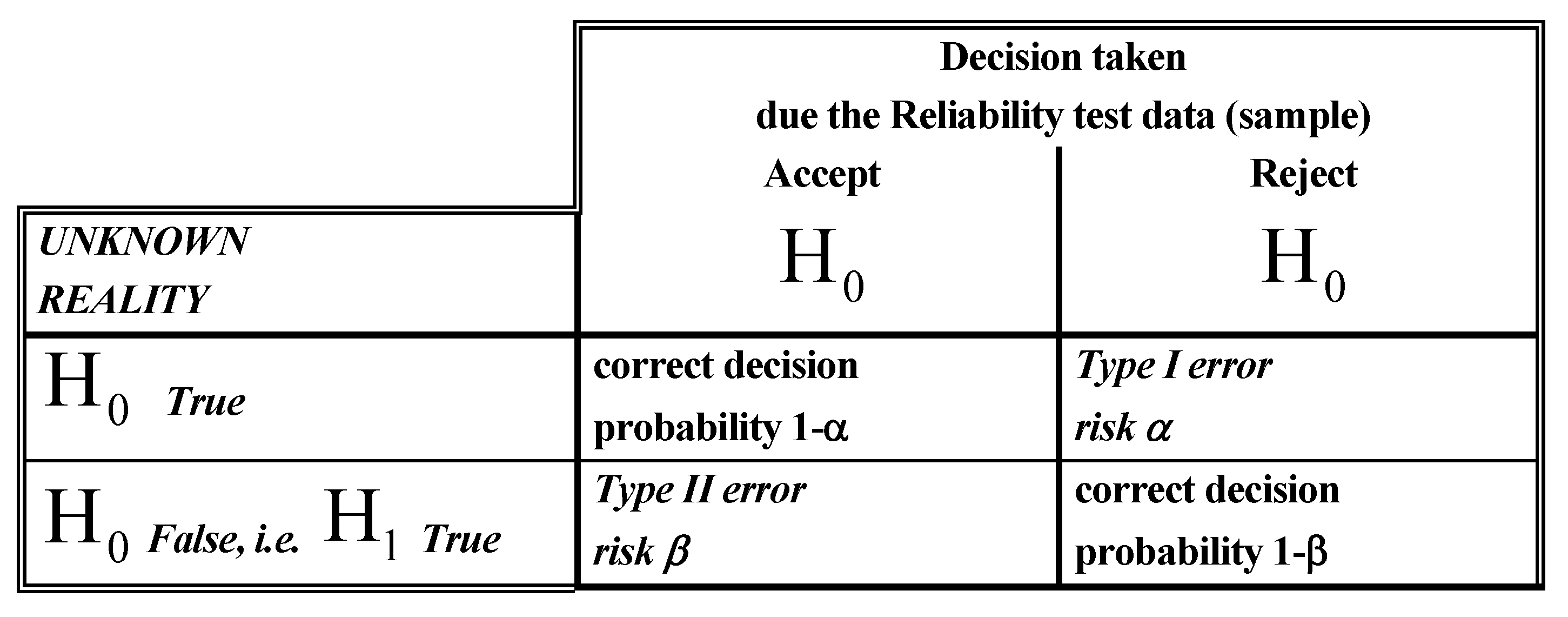

- Simple Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) and the values of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

- Composite Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) BUT NOT the values of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

- a. Parametric Hypothesis: it specifies completely the distribution (probabilistic model) and the values (some or all) of the parameters of the distribution of the Random Variable under consideration

- b. Non-parametric Hypothesis: it does not specify the distribution (probabilistic model) of the Random Variable under consideration

- for which sample values the decision is made to «accept» H0 as true,

- for which sample values H0 is rejected and then H1 is accepted as true.

- the test statistic (a formula to analyse the data)

- the critical region R (rejection region)

- 1)

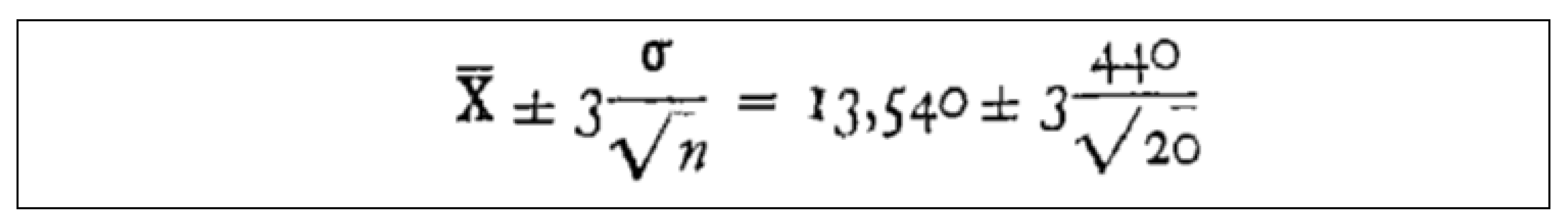

- Construct a confidence interval for the population mean

- 2)

- THEN Accept H0; otherwise H0 is rejected.

- ⇒ the risks must be stated,

- ⇒ together with the goals (the hypotheses),

- ⇒ BEFORE any statistical (reliability) test is carried out.

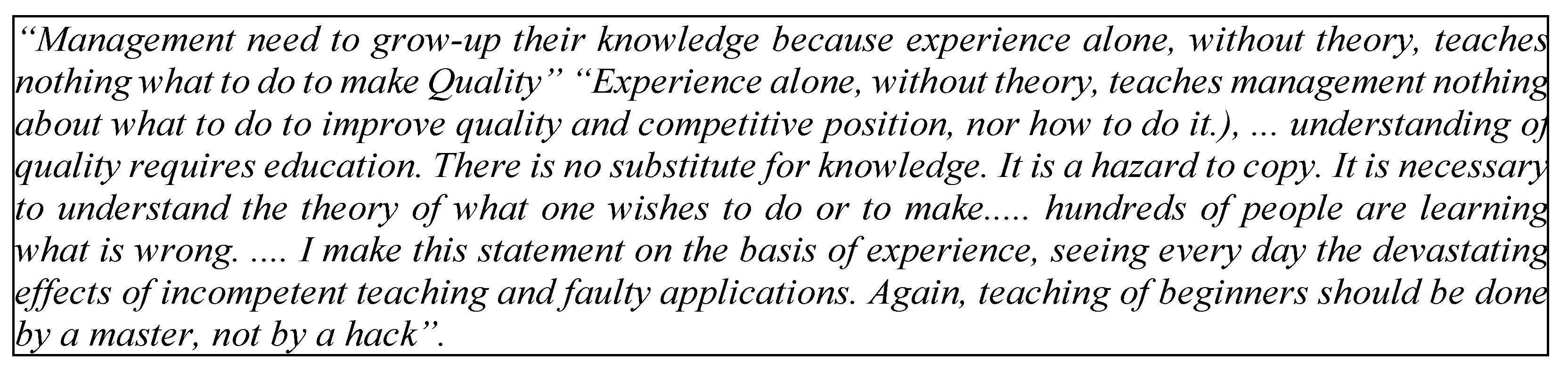

- A figure without a theory tells nothing.

- There is no substitute for knowledge.

- There is widespread resistance of knowledge.

- Knowledge is a scarce national resource.

- Why waste Knowledge?

- Management need to grow-up their knowledge because experience alone, without theory, teaches nothing what to do to make Quality

- Anyone that engages teaching by hacks deserves to be rooked.

- Ø The result is that hundreds of people are learning what is wrong. I make this statement on the basis of experience, seeing every day the devastating effects of incompetent teaching and faulty applications.

Appendix C

References

- Galetto, F., Quality of methods for quality is important. European Organisation for Quality Control Conference, Vienna. 1989.

- Galetto, F., GIQA, the Golden Integral Quality Approach: from Management of Quality to Quality of Management. Total Quality Management (TQM), Vol. 10, No. 1; 1999.

- Chakraborti et al., Properties and performance of the c-chart for attributes data, Journal of Applied Statistics, January 2008.

- Kumar, N. , Chakraborti, S., Rakitzis, A. C. et al., Improved Shewhart-Type Charts for Monitoring Time Between Events. Journal of Quality Technology 2017, 49, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. W. , Xie, M., Goh, T. N., Design of exponential control charts using a sequential sampling scheme. IIE Transactions 2006, 38, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, M. Statistical Methods in the Process Industry: McMillan; 1973.

- Casella, Berger, Statistical Inference, 2nd edition: Duxbury Advanced Series; 2002.

- Cramer, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics: Princeton University Press; 1961.

- Deming W., E. , Out of the Crisis, Cambridge University Press; 1986.

- Deming W., E. , The new economics for industry, government, education: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

- Dore, P. , Introduzione al Calcolo delle Probabilità e alle sue applicazioni ingegneristiche, Casa Editrice Pàtron, Bologna; 1962.

- Juran, J. , Quality Control Handbook, 4th, 5th ed.: McGraw-Hill, New York: 1988-98.

- Kendall, Stuart, (1961) The advanced Theory of Statistics, Volume 2, Inference and Relationship:, Hafner Publishing Company; 1961.

- Meeker, W. Q. , Hahn, G. J., Escobar, L. A. Statistical Intervals: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers. John Wiley & Sons. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mood, Graybill, Introduction to the Theory of Statistics, 2nd ed.: McGraw Hill; 1963.

- Rao, C. R. , Linear Statistical Inference and its Applications: Wiley & Sons; 1965.

- Rozanov, Y. , Processus Aleatoire, Editions MIR: Moscow, (traduit du russe); 1975.

- Ryan, T. P. , Statistical Methods for Quality Improvement: Wiley & Sons; 1989.

- Shewhart W., A. , Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Products: D. Van Nostrand Company; 1931.

- Shewhart, W.A. , Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control: Graduate School, Washington; 1936.

- D. J. Wheeler, Various posts, Online available from Quality Digest.

- Galetto, F., (2014), Papers, and Documents of FG, Research Gate.

- Galetto, F. , (2015-2025), Papers, and Documents of FG, Academia.

- Galetto, F. , (2024), The garden of flowers, Academia.

- Galetto, F. , Affidabilità Teoria e Metodi di calcolo: CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy); 1981-94.

- Galetto, F. , Affidabilità Prove di affidabilità: distribuzione incognita, distribuzione esponenziale: CLEUP editore, Padova (Italy); 1982, 85, 94.

- Galetto, F. , Qualità. Alcuni metodi statistici da Manager: CLUT, Torino (Italy; 1995-2010).

- Galetto, F. , Gestione Manageriale della Affidabilità: CLUT, Torino (Italy); 2010.

- Galetto, F. , Manutenzione e Affidabilità: CLUT, Torino (Italy); 2015.

- Galetto, F. , Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach, Vol-1: www.morebooks.de.; 2016.

- Galetto, F. , Reliability and Maintenance, Scientific Methods, Practical Approach, Vol-2: www.morebooks.de.; 2016.

- Galetto, F., Statistical Process Management, ELIVA press ISBN 9781636482897; 2019.

- Galetto F., Affidabilità per la manutenzione, Manutenzione per la disponibilità: tab edizioni, Roma (Italy), ISBN 978-88-92-95-435-9, www.tabedizioni.it; 2022.

- Galetto, F. Hope for the Future: Overcoming the DEEP Ignorance on the CI (Confidence Intervals) and on the DOE (Design of Experiments). Science J. Applied Mathematics and Statistics 2015, 3, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F. Management Versus Science: Peer-Reviewers do not Know the Subject They Have to Analyse. Journal of Investment and Management. 2015, 4, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F. The first step to Science Innovation: Down to the Basics. , Journal of Investment and Management. 2015, 4, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F. , (2021) Minitab T charts and quality decisions, Journal of Statistics and Management Systems. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2021) Control Charts for TBE and Quality Decisions, Academia.edu.

- Galetto, F. (2021) ASSURE: Adopting Statistical Significance for Understanding Research and Engineering, Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Technology, ISSN: 2634 – 8853, 2021 SRC/JEAST-128. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, F., (2006) Does Peer Review assure Quality of papers and Education? 8th Conference on TQM for HEI, Paisley (Scotland).

- Galetto, F., (2001), Looking for Quality in “quality books”, 4th Conference on TQM for HEI, Mons (Belgium).

- Galetto, F., (2001), Quality QFD and control charts, Conference ATA, Florence (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2002), Fuzzy Logic and Control Charts, 3rd ICME Conference, Ischia (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2010),The Pentalogy Beyond, 9th Conference on TQM for HEI, Verona (Italy).

- Galetto, F., (2024), News on Control Charts for JMP, Academia.edu.

- Galetto, F., (2024), JMP and Minitab betray Quality, Academia.edu.

| Notice that only the Weibull … is Yes | Using 40 t4 data | Using 160 data | |||

| Exponential | NO | 924.02 | 231.13 | ||

| Weibull | Yes | 1.18 | 989.44 | 0.795 | 201.35 |

| Gamma | NO | 1.65 | 561.21 | 0.718 | 322.12 |

| Normal | NO | ||||

| Normal | NO | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).