Communication:

Henri Ciriani (

Figure 1), the Franco-Peruvian architect and educator, carved an enduring legacy through a unified philosophy of teaching and design, anchored in the moral, social, and spatial ambitions of modernism. One of the last great voices of this movement, Ciriani passed away on October 3, 2025, at the age of 89. Born in Lima on December 30, 1936, he trained at the Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería (UNI), worked for the Peruvian Ministry of Public Works and the National Housing Institute, and in 1964 left for France, where he rebuilt his career and influence from the ground up.

He saw himself not merely as a practitioner, but as a militant advocate for architecture’s civic role. A self-proclaimed Corbusian, Ciriani believed he was continuing Le Corbusier’s unfinished mission, humanizing modernism through light, proportion, order, and spatial clarity. For him, architecture was not a stylistic exercise, but a tool to dignify human life.

Even early in his career, his work in Peru already reflected this conviction, particularly in the design of social housing and public facilities. Upon moving to France, he joined the Atelier d’Urbanisme et d’Architecture (AUA), collaborating on major civic projects like the Arlequin district in Grenoble, which reinforced his belief that architecture must act as a structuring and transformative urban force. In the 1980s, Ciriani established his own practice, refining a language of form that remained abstract yet deeply humane.

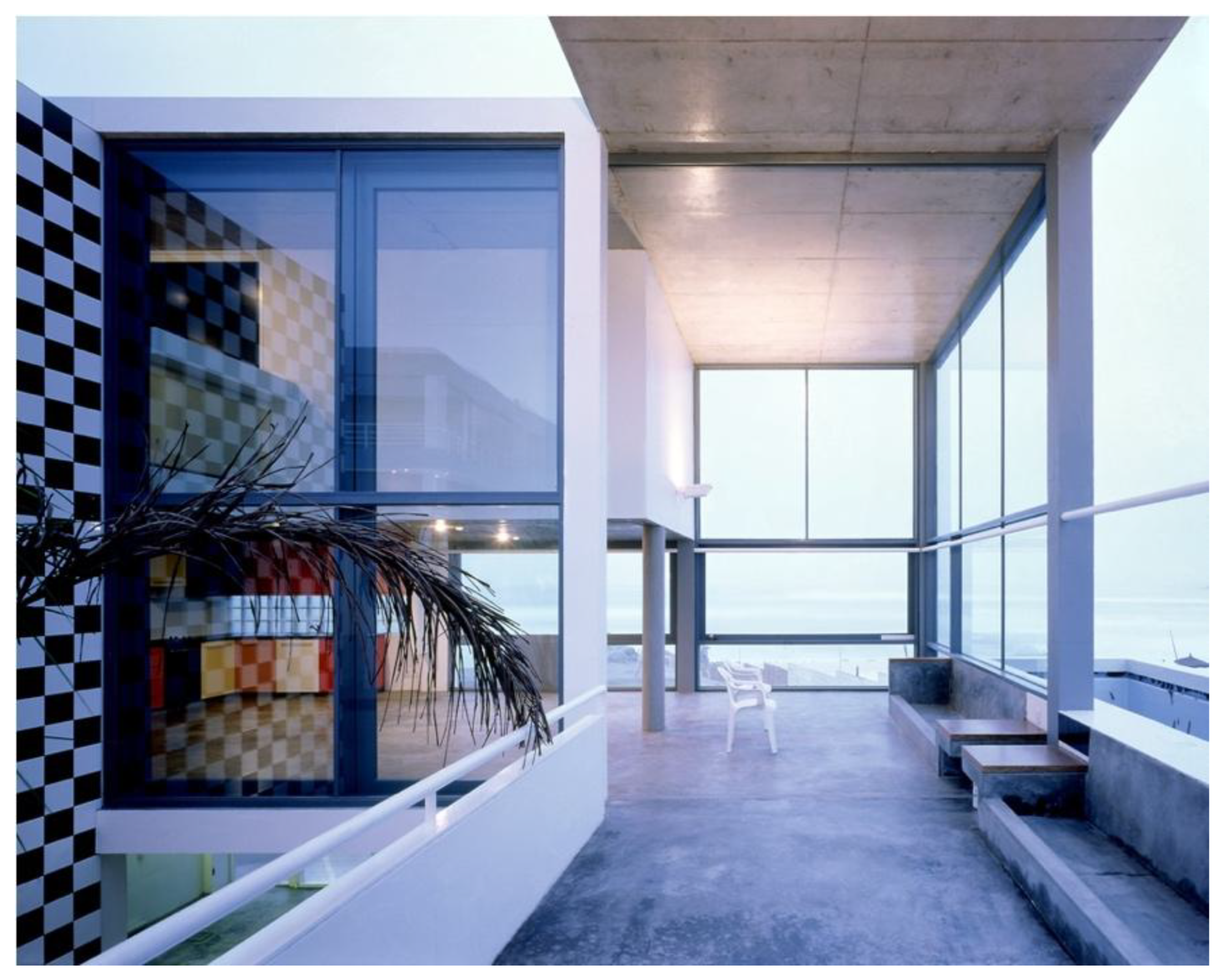

His architectural philosophy was encapsulated by the idea of

l’espace émouvant “the stirring space”. This was not about kinetic form, but about creating emotional and sensory experiences through the sequencing of space, calibrated light, and spatial rhythm (

Figure 2). Light, for Ciriani, was a primary material, used to articulate form, create atmosphere, and animate surfaces. His buildings were to be experienced in motion, as architectural promenades that unfold meaning with each step.

I had the privilege of studying under Henri Ciriani at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville, where he taught for over three decades. His teaching was described by many as charismatic, rigorous, and at times militant. In 1972, he founded the legendary Studio UNO, which became the intellectual backbone of the school. As one of his students, I experienced firsthand the intensity of his pedagogy, how he pushed us not just to think about space, but to feel it, to give it ethical weight.

The pedagogical exercise that most captured his philosophy was “L’espace 30 × 30” third year design studio teaching the modern space: a library, a conceptual and spatial challenge in which students had to organize a space within a 30 meter square grid. It was never about formalism; it was a lesson in the grammar of modern architecture: gravity, compression & expansion, light, movement, and the architectural promenade. Clarity and generosity were presented not as aesthetic goals but as moral ones. His core question: “What is the difference between architecture and construction?”, still echoes in the minds of his former students.

His studio became a pilgrimage site for aspiring architects from around the world. I remember groups of Korean students arriving in Paris with one goal: to enroll in Studio UNO and absorb his vision. That international pull was testament to the universal relevance of his ideas, and the depth of his influence.

Ciriani’s mature work embodies his ethical modernism, particularly in three major projects:

Even in the realm of social housing, often seen as a utilitarian task, Ciriani pursued dignity. His housing in Noisy-le-Grand turns a common programme into a civic statement through bold forms, geometric façades, and expressive use of concrete and color turn a common program into a civic statement. For him, social housing was not peripheral, it was central to the life of the city.

Over his long career, Ciriani received many accolades, including the Grand Prix national de l’architecture (1983), the Équerre d’Argent (1983), the Médaille d’Or de l’Académie d’Architecture (2012), and Le Grand Prix d’Architecture, Prix Charles Abella (2021). But perhaps his greatest legacy lies in the architects he shaped, those he taught to see light not as decoration but as structure, to see proportion as ethics, and to understand that design is always a political act.

Even as architectural trends veered toward postmodern irony or digital experimentation, Ciriani stayed loyal to a modernism of plastic depth and psychological warmth. He often returned to Peru, reminding younger generations that modernism was still an ethical undertaking worth fighting for.

Henri Ciriani leaves no manifesto, only buildings and former students who continue to shape atmosphere and stir architectural spaces.