Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Establish evaluation system to configure optimal parameters for SDM devices

- Validate the behavior of SDM by computational tests from SDM benchmark

- Define and validate preliminary the hybrid architecture containing SDM module (System 1) and dual-transformer module (System 2)

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. SDM Evaluation Methodology

3.2. SDM Benchmark Design

3.3. System 1 Methodology

- Establish inherent System 1 mechanisms

- Integrate intuitive System 1 mechanisms

- Implement controller to detect emergent System 1 mechanisms

- Integrate System 2 dual transformers to System 1 (SDM and controller)

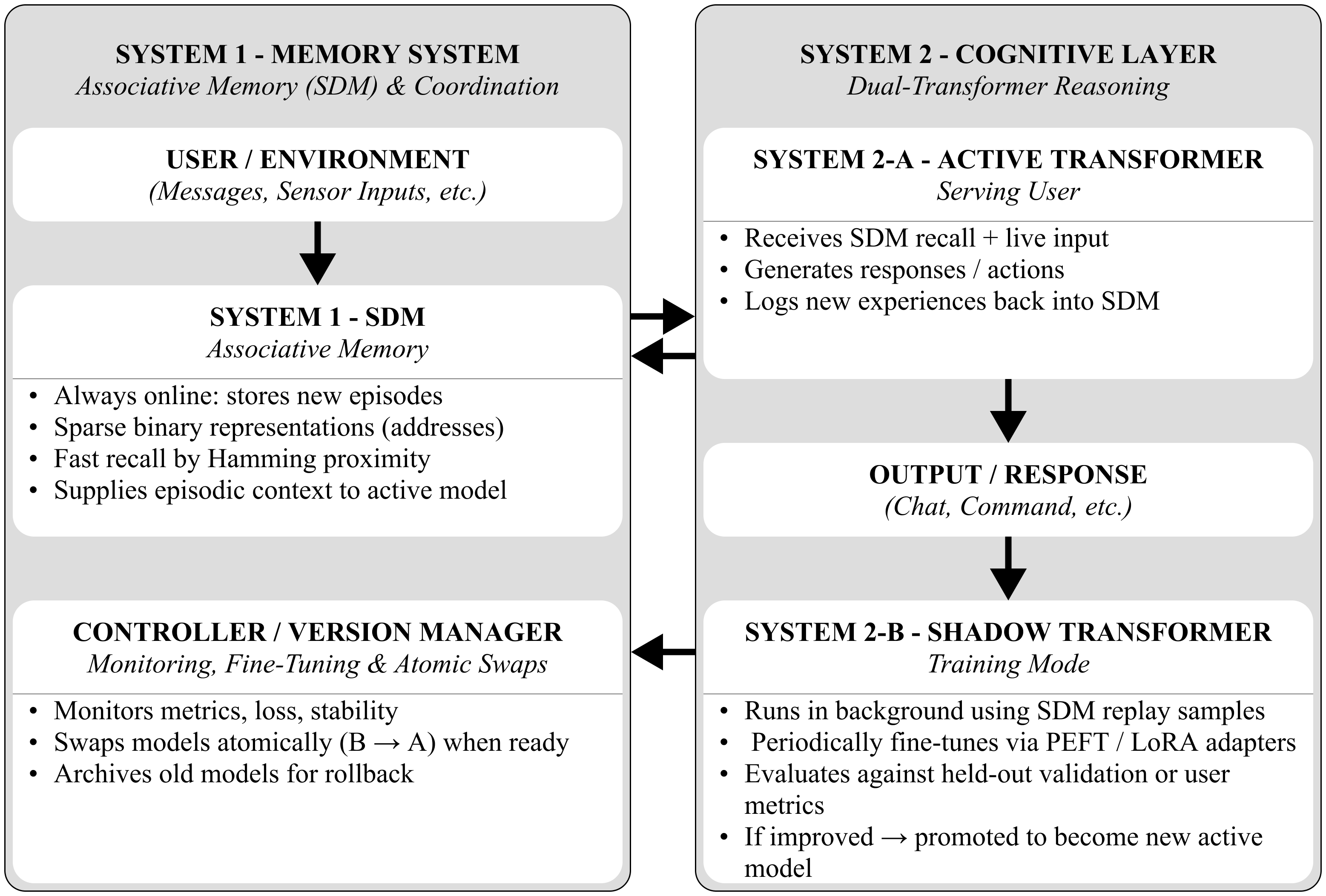

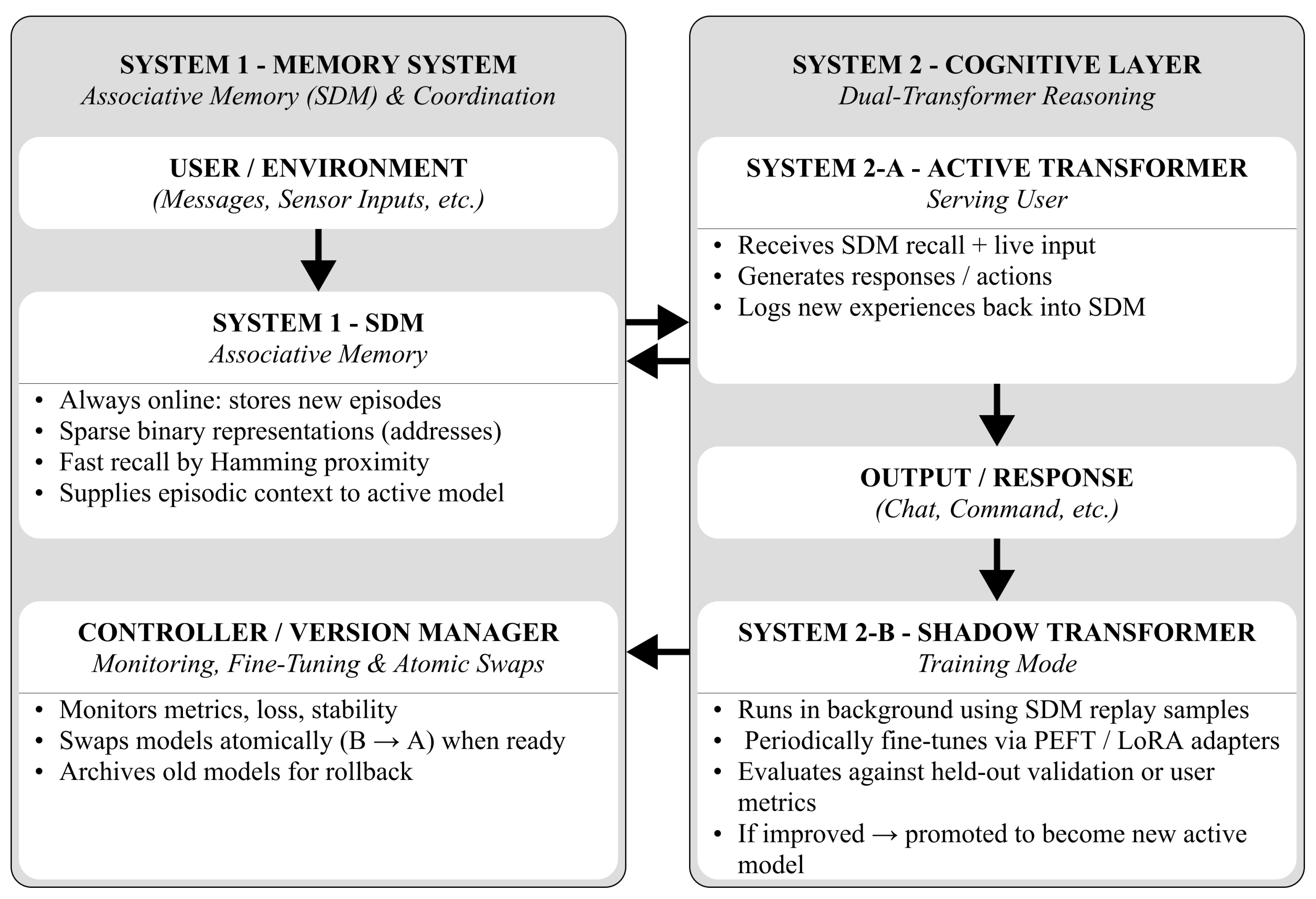

3.4. CALM Architecture

- Continual Adaptation: SDM is allowing rapid incorporation of new data without retraining.

- Memory Grounding: The system maintains an episodic trace of events, enabling structured recall and System 1 operations.

- Biological Plausibility: The modular memory structure aligns with the distributed intelligence of the cortical columns and sensorimotor integration.

- Encoding & Acquisition: New input is encoded as high-dimensional binary vectors and stored in SDM.

- Retrieval & Reasoning: SDM provides associative recall to the Active Transformer, which generates responses and updates memory into the SDM.

- Consolidation: The Shadow Transformer fine-tunes asynchronously on SDM replay data, ensuring gradual learning without disrupting live performance.

3.5. CALM Integration

4. Preliminary Results

5. Discussion and Future Work

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CALM | Continual Associative Learning Model |

| EGRU | Event-based Gated Recurrent Units |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| SDM | Sparse Distributed Memory |

| VC | Virtual Cities |

| WYSIATI | What You See Is All There Is |

References

- Huang, C.C.; Rolls, E.T.; Hsu, C.C.H.; Feng, J.; Lin, C.P. Extensive Cortical Connectivity of the Human Hippocampal Memory System: Beyond the “What” and “Where” Dual Stream Model. Cerebral Cortex 2021, 31, 4652–4669. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, P. Sparse Distributed Memory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988.

- Kanerva, P. Self-propagating search: a unified theory of memory (address decoding, cerebellum). 1984.

- Karunaratne, G.; Le Gallo, M.; Cherubini, G.; Benini, L.; Rahimi, A.; Sebastian, A. In-memory hyperdimensional computing. Nature Electronics 2020, 3, 327–337. Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, . [CrossRef]

- Keeler, J.D. Capacity for patterns and sequences in Kanerva’s SDM as compared to other associative memory models, Denver, CO, 1988. NTRS Author Affiliations: NASA Ames Research Center NTRS Document ID: 19890041660 NTRS Research Center: Legacy CDMS (CDMS).

- Flynn, M.J.; Kanerva, P.; Bhadkamkar, N. Sparse distributed memory: Principles and operation; Number RIACS-TR-89-53, NASA, 1989. NTRS Author Affiliations: Research Inst. for Advanced Computer Science NTRS Document ID: 19920001076 NTRS Research Center: Legacy CDMS (CDMS).

- Marr, D. A theory of cerebellar cortex. The Journal of Physiology 1969, 202, 437–470. [CrossRef]

- Albus, J.S. Mechanisms of planning and problem solving in the brain. Mathematical Biosciences 1979, 45, 247–293. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805].

- Kawato, M.; Ohmae, S.; Hoang, H.; Sanger, T. 50 Years Since the Marr, Ito, and Albus Models of the Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2021, 462, 151–174. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, P. Sparse distributed memory and related models. Technical Report NASA-CR-190553, 1992. NTRS Author Affiliations: Research Inst. for Advanced Computer Science NTRS Document ID: 19920021480 NTRS Research Center: Legacy CDMS (CDMS).

- Bricken, T.; Davies, X.; Singh, D.; Krotov, D.; Kreiman, G. Sparse Distributed Memory is a Continual Learner. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rinkus, G.J. A cortical sparse distributed coding model linking mini- and macrocolumn-scale functionality. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy 2010, 4. Publisher: Frontiers, . [CrossRef]

- Wixted, J.T.; Squire, L.R.; Jang, Y.; Papesh, M.H.; Goldinger, S.D.; Kuhn, J.R.; Smith, K.A.; Treiman, D.M.; Steinmetz, P.N. Sparse and distributed coding of episodic memory in neurons of the human hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 9621–9626. Publisher: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, . [CrossRef]

- Snaider, J.; Franklin, S.; Strain, S.; George, E.O. Integer sparse distributed memory: Analysis and results. Neural Networks 2013, 46, 144–153. [CrossRef]

- Furber, S.B.; John Bainbridge, W.; Mike Cumpstey, J.; Temple, S. Sparse distributed memory using N-of-M codes. Neural Networks 2004, 17, 1437–1451. [CrossRef]

- Peres, L.; Rhodes, O. Parallelization of Neural Processing on Neuromorphic Hardware. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2022, 16, 867027. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.A.; Huang, J.; Kelber, F.; Nazeer, K.K.; Langer, T.; Liu, C.; Lohrmann, M.; Rostami, A.; Schöne, M.; Vogginger, B.; et al. SpiNNaker2: A Large-Scale Neuromorphic System for Event-Based and Asynchronous Machine Learning 2024. arXiv:2401.04491 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bellec, G.; Vogginger, B.; Kappel, D.; Partzsch, J.; Neumärker, F.; Höppner, S.; Maass, W.; Furber, S.B.; Legenstein, R.; et al. Memory-Efficient Deep Learning on a SpiNNaker 2 Prototype. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12. Publisher: Frontiers, . [CrossRef]

- Nazeer, K.K.; Schöne, M.; Mukherji, R.; Mayr, C.; Kappel, D.; Subramoney, A. Language Modeling on a SpiNNaker 2 Neuromorphic Chip, 2023. arXiv:2312.09084 [cs] version: 1, . [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. XNOR-Net: ImageNet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks, 2016, [arXiv:cs.CV/1603.05279]. [CrossRef]

- Vdovychenko, R.; Tulchinsky, V. Sparse Distributed Memory for Sparse Distributed Data. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Systems and Applications; Arai, K., Ed., Cham, 2023; p. 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Vdovychenko, R.; Tulchinsky, V. Sparse Distributed Memory for Binary Sparse Distributed Representations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies, New York, NY, USA, 2022; ICMLT ’22, p. 266–270. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 3521–3526. arXiv:1612.00796 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Rolnick, D.; Ahuja, A.; Schwarz, J.; Lillicrap, T.P.; Wayne, G. Experience Replay for Continual Learning, 2019. arXiv:1811.11682 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.; Field, D. Sparse Coding in the Neocortex. Evolution of Nervous Systems 2007, 3. [CrossRef]

- Beyeler, M.; Rounds, E.L.; Carlson, K.D.; Dutt, N.; Krichmar, J.L. Neural correlates of sparse coding and dimensionality reduction. PLoS Computational Biology 2019, 15, e1006908. [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, I.P.; Glerean, E.; Klucharev, V.; Shestakova, A.; Ahveninen, J. Do sparse brain activity patterns underlie human cognition? NeuroImage 2022, 263, 119633. [CrossRef]

- Drix, D.; Hafner, V.V.; Schmuker, M. Sparse coding with a somato-dendritic rule. Neural Networks 2020, 131, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Olshausen, B.A.; Field, D.J. Sparse coding of sensory inputs. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2004. [CrossRef]

- Le, N.D.H. Sparse Code Formation with Linear Inhibition 2015. arXiv:1503.04115 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Panzeri, S.; Moroni, M.; Safaai, H.; Harvey, C.D. The structures and functions of correlations in neural population codes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2022, 23, 551–567. [CrossRef]

- Chaisanguanthum, K.S.; Lisberger, S.G. A Neurally Efficient Implementation of Sensory Population Decoding. The Journal of Neuroscience 2011, 31, 4868–4877. [CrossRef]

- Aleksander, I.; Stonham, T.J. Guide to pattern recognition using random-access memories. Iee Journal on Computers and Digital Techniques 1979, 2, 29–40. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Frederic, S., 2002. [CrossRef]

- Nechesov, A.; Ruponen, J. Empowering Government Efficiency Through Civic Intelligence: Merging Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain for Smart Citizen Proposals. Technologies 2024, 12, 271. [CrossRef]

- Nechesov, A.; Dorokhov, I.; Ruponen, J. Virtual Cities: From Digital Twins to Autonomous AI Societies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13866–13903. [CrossRef]

- Ruponen, J.; Dorokhov, I.; Barykin, S.E.; Sergeev, S.; Nechesov, A. Metaverse Architectures: Hypernetwork and Blockchain Synergy. In Proceedings of the First Conference of Mathematics of AI, 2025.

- Dorokhov, I.; Ruponen, J.; Shutsky, R.; Nechesov, A. Time-Exact Multi-Blockchain Architectures for Trustworthy Multi-Agent Systems-. MathAI 2025.

Short Biography of Authors

|

Andrey Nechesov— Corresponding Member of RIA, Head of Research Department at the AI Center of Novosibirsk State University. Main organizer of the international conference “Mathematics of Artificial Intelligence”. Expert in the field of strong artificial intelligence, blockchain technologies, and cryptocurrencies. Author and creator of the investment-analytical strategy “One Way — One AI”. |

|

Janne Ruponen —Multidisciplinary Engineer and Researcher with a background in mechanical engineering, innovation, and technology management. His expertise spans the development of advanced manufacturing technologies, including significant contributions to additive manufacturing and 3D printing. He has also led impactful projects in urban planning and automation, such as creating unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) systems and digital twin implementations for heavy industries. His current research explores the integration of blockchain and artificial intelligence, with a focus on applications for moderative multi-agent systems. |

| Parameter | Values | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Vector Dimension | 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024 | Tests scaling from embedded to server deployment |

| Memory Locations | 500, 1K, 3K, 5K, 8K | Evaluates capacity vs. interference trade-offs |

| Access Radius Factor | 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.78, 0.9 | Explores specificity vs. generalization spectrum |

| Reinforcement Cycles | 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, 50, 100 | Standard strengthening for reliable storage |

| Address Vector (Binary) | Payload | Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| 001010001000010100... | “person detected” | 0.87 |

| 111000000101100010... | “car detected” | 0.92 |

| 000100100000000001... | “no motion” | 0.95 |

| Capability | SDM Strength | Transformer Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Online Learning | High | Low |

| Memory Efficiency | High | Low |

| Language Modeling | Low | High |

| Few-shot Learning | High | Medium |

| Noise Robustness | High | Medium |

| Complex Reasoning | Medium | High |

| Interpretability | High | Low |

| Stage | Input | Output Metrics | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDMPreMark | SDM configuration sets | Match ratio, sparsity, runtime | Validate System 1 associative stability |

| CALMark | SDM replay data, transformer checkpoints | , loss stability, swap success | Verify continual consolidation between System 1 and System 2 |

| Continual Reasoning | GLUE, SQuAD, episodic datasets | Retention, adaptation speed, reasoning accuracy | Measure long-term stability and learning efficiency |

| Regime | Radius Range | Match Ratio | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-activation | 0.4–0.6 | No successful retrieval, recalled_ones = 0 | |

| Transition Zone | 0.6–0.9 | Unstable, configuration-dependent | |

| Over-activation | 1.0 | Perfect recall, full pattern recovery |

| Locations | Match Ratio | Latency (ms) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1.0 | 0.090 | High |

| 1,000 | 1.0 | 0.188 | Medium |

| 3,000 | 1.0 | 0.564 | Medium |

| 5,000 | 1.0 | 0.942 | Low |

| 8,000 | 1.0 | 1.501 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).