Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and CNSEC Screening

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- A: Number of isolates confirmed as CNSEC (intermediate or resistant to any carbapenem)

- B: Total number of E. coli isolates tested from that source

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Confirmation of E. coli Strain

2.5. Detection of Carbapenemase Genes in CNSEC Isolates

2.6. Detection of Virulence Genes in CNSEC Isolates

2.7. Determination of Phylogenetic Groups

2.8. Analysis of Genetic Relatedness

3. Results

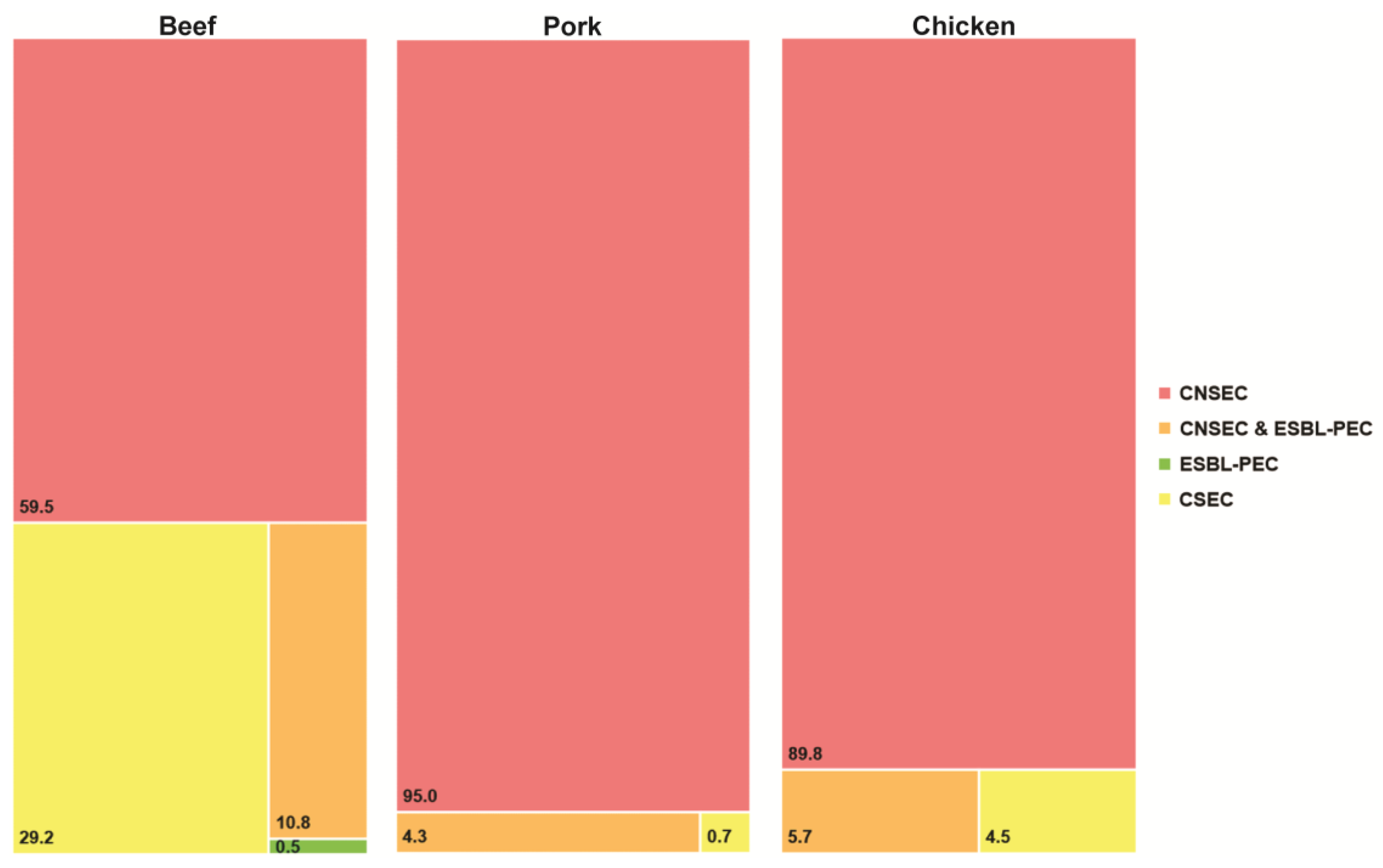

3.1. Prevalence of CNSEC Surrogates

3.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles

3.3. Carbapenemase Genes in CREC Isolates

3.4. Molecular Relationship in blaNDM-Harboring CREC Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marino, A.; Maniaci, A.; Lentini, M.; Ronsivalle, S.; Nunnari, G.; Cocuzza, S.; Parisi, F.M.; Cacopardo, B.; Lavalle, S.; La Via, L. The Global Burden of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Epidemiologia 2025, 6(2), 21. [CrossRef]

- Zankere, T.; Lechiile, K.; Mokgwathi, K.; Tlhako, N.; Moorad, B.; Ntereke, T.D.; Gatonye, T.; Lautenbach, E.; Richard-Greenblatt, M.; Mokomane, M.; Mosepele, M.; Cancedda, C.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Styczynski, A.; Parra, G.; Smith, R.M.; Mannathoko, N.; Strysko, J. Admission screening for extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales colonization at a referral hospital in Botswana: A one-year period-prevalence survey, 2022–2023. PLOS Global Public Health 2025, 5(10), e0005018. [CrossRef]

- Suay-García, B.; Pérez-Gracia, M.T. Present and future of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Advances in clinical immunology, medical microbiology, COVID-19, and big data 2021, 435-456. [CrossRef]

- Netikul, T.; Kiratisin, P. Genetic characterization of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae and the spread of carbapenem-resistant klebsiella pneumonia ST340 at a university hospital in Thailand. PloS one 2015, 10(9), e0139116. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zou, G.; Huang, X.; Bi, J.; Meng, L.; Zhao, W.; Li, T. Molecular characterization and resistance mechanisms of ertapenem-non-susceptible carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae co-harboring ESBLs or AmpC enzymes with porin loss or efflux pump overexpression. J. Bacteriol. 2025, e00148-25. [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Weinstein, R.A. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. The Journal of infectious diseases 2017, 215(suppl_1), S28-S36. [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Mendes, R.E.; Doyle, T.B.; Sader, H.S. Prevalence of carbapenemase genes among carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected in US hospitals in a five-year period and activity of ceftazidime/avibactam and comparator agents. JAC-antimicrobial resistance 2022, 4(5), dlac098. [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi Halat, D.; Ayoub Moubareck, C. The current burden of carbapenemases: Review of significant properties and dissemination among gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9(4), 186. [CrossRef]

- Nataro, J.P.; Kaper, J.B. Diarrheagenic escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11(1), 142-201.

- Johnson, J.R.; Murray, A.C.; Gajewski, A.; Sullivan, M.; Snippes, P.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Smith, K.E. Isolation and molecular characterization of nalidixic acid-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from retail chicken products. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2003, 47(7), 2161-2168. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (2019 AR Threats Report), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA. 2019 [Accessed 04 January 2020]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/Biggest-Threats.html.

- Ramírez-Castillo, F.Y.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L.; Avelar-González, F.J. An overview of carbapenem-resistant organisms from food-producing animals, seafood, aquaculture, companion animals, and wildlife. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10(1158588. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bi, Z.; Ma, S.; Chen, B.; Cai, C.; He, J.; Schwarz, S.; Sun, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J. Inter-host transmission of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli among humans and backyard animals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127(10), 107009. [CrossRef]

- Grönthal, T.; Österblad, M.; Eklund, M.; Jalava, J.; Nykäsenoja, S.; Pekkanen, K.; Rantala, M. Sharing more than friendship–transmission of NDM-5 ST167 and CTX-M-9 ST69 Escherichia coli between dogs and humans in a family, Finland, 2015. Eurosurveillance 2018, 23(27), 1700497. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Tsai, W.-C.; Li, J.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Wang, J.-T.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, F.-J.; Lauderdale, T.-L.; Chang, S.-C. Increasing New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-positive Escherichia coli among carbapenem non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae in Taiwan during 2016 to 2018. Scientific reports 2021, 11(1), 2609. [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Expert consensus protocol on carbapenem resistance detection and characterisation for the survey of carbapenem- and/or colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae – Version 3.0. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 2019. 2019 [30 October 2025]; Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/expert-consensus-protocol-carbapenem-resistance.pdf.

- Sirikaew, S.; Rattanachuay, P.; Nakaguchi, Y.; Sukhumungoon, P. Immuno-magnetic isolation, characterization and genetic relationship of Escherichia coli O26 from raw meats, Hat Yai City, Songkhla, Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2015, 46(2), 241.

- Adler, A.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Marcos, E.; Schwartz, D.; Carmeli, Y. Laboratory and clinical evaluation of screening agar plates for detection of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from surveillance rectal swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49(6), 2239-2242. [CrossRef]

- Mosavie, M.; Blandy, O.; Jauneikaite, E.; Caldas, I.; Ellington, M.J.; Woodford, N.; Sriskandan, S. Sampling and diversity of Escherichia coli from the enteric microbiota in patients with Escherichia coli bacteraemia. BMC Research Notes 2019, 12(1), 335. [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; Twenty-Sixth edition informational Supplement (M100S). CLSI, Wayne, PA. 2016. 2016,.

- Johnson, J.R.; Gajewski, A.; Lesse, A.J.; Russo, T.A. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli as a cause of invasive nonurinary infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41(12), 5798-5802. [CrossRef]

- Clermont, O.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bingen, E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66(10), 4555-4558. [CrossRef]

- Sukhumungoon, P.; Sae-lim, A.; Hayeebilan, F.; Rattanachuay, P. Prevalence, Virulence Profiles, and Genetic Relatedness of Escherichia coli O45 from Raw meats, Southern Thailand. Journal of Scientific and Technological Reports Online ISSN: 2773-8752 2023, 27(2), 58-71. [CrossRef]

- Versalovic, J. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 5(25-40.

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2022 guidance on the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR-P. aeruginosa). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75(2), 187-212.

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The lancet 2022, 399(10325), 629-655. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Rizzotti, L.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S. Horizontal gene transfer among microorganisms in food: current knowledge and future perspectives. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42(232-243. [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Hansen, G.R.; Kar, A.; Cordova, C.D.; Price, L.B.; Johnson, J.R. Antibiotic resistance in humans and animals. NAM Perspectives 2016,. [CrossRef]

- Authority, E.F.S.; Prevention, E.C.f.D.; Control. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2018/2019. Efsa Journal 2021, 19(4), e06490.

- Tshitshi, L.; Manganyi, M.C.; Montso, P.K.; Mbewe, M.; Ateba, C.N. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase-resistant determinants among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from beef cattle in the north West Province, South Africa: a critical assessment of their possible public health implications. Antibiotics 2020, 9(11), 820. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahian, S.; Graham, J.P.; Halaji, M. A review of the mechanisms that confer antibiotic resistance in pathotypes of E. coli. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2024, 14(1387497. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Lavelle, K.; Huang, A.; Atwill, E.R.; Pitesky, M.; Li, X. Assessment of prevalence and diversity of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli from retail meats in Southern California. Antibiotics 2023, 12(4), 782. [CrossRef]

- van Boxtel, R.; Wattel, A.A.; Arenas, J.; Goessens, W.H.; Tommassen, J. Acquisition of carbapenem resistance by plasmid-encoded-AmpC-expressing Escherichia coli. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2017, 61(1), 10.1128/aac. 01413-16. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xiang, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, K.; Wu, K.; Su, M.; Li, R.; Hurley, D.; Bai, L. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae cultured from retail meat products, patients, and porcine excrement in China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12(743468. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.M.; Abd El-Aziz, A.M.; Hassan, R.; Abdelmegeed, E.S. β-lactam resistance associated with β-lactamase production and porin alteration in clinical isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae. PLoS One 2021, 16(5), e0251594.

- Chang, Y.-T.; Siu, L.K.; Wang, J.-T.; Wu, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Lin, J.-C.; Lu, P.-L. Resistance mechanisms and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Escherichia coli in Taiwan, 2012-2015. Infection and drug resistance 2019, 2113-2123. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.-H.; Chu, M.-J.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Zou, M.; Liu, B.-T. High prevalence and transmission of blaNDM-positive Escherichia coli between farmed ducks and slaughtered meats: An increasing threat to food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 424(110850. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Fu, B.; Shi, X.; Sun, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; Walsh, T.R.; Cai, C.; Wang, Y. Contaminated in-house environment contributes to the persistence and transmission of NDM-producing bacteria in a Chinese poultry farm. Environ. Int. 2020, 139(105715. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; San José, M.; Roschanski, N.; Schmoger, S.; Baumann, B.; Irrgang, A.; Friese, A.; Roesler, U.; Helmuth, R.; Guerra, B. Spread and persistence of VIM-1 Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in three German swine farms in 2011 and 2012. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 200(118-123. [CrossRef]

- Pulss, S.; Semmler, T.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Bauerfeind, R.; Ewers, C. First report of an Escherichia coli strain from swine carrying an OXA-181 carbapenemase and the colistin resistance determinant MCR-1. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50(2), 232-236. [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.D.; Ahmed, M.F.; El-Adawy, H.; Hotzel, H.; Engelmann, I.; Weiß, D.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R. Surveillance of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in dairy cattle farms in the Nile Delta, Egypt. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7(1020. [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Diaconu, E.L.; Ianzano, A.; Di Matteo, P.; Amoruso, R.; Dell'Aira, E.; Sorbara, L.; Bottoni, F.; Guarneri, F.; Campana, L. The hazard of carbapenemase (OXA-181)-producing Escherichia coli spreading in pig and veal calf holdings in Italy in the genomics era: Risk of spill over and spill back between humans and animals. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13(1016895. [CrossRef]

- Tello, M.; Oporto, B.; Lavín, J.L.; Ocejo, M.; Hurtado, A. Characterization of a carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli from dairy cattle harbouring bla NDM-1 in an IncC plasmid. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77(3), 843-845. [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, F.; Donkor, E. Carbapenem resistance: a review. Medical Sciences 2018, 6(1), 1.

- Connell, I.; Agace, W.; Klemm, P.; Schembri, M.; Mărild, S.; Svanborg, C. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93(18), 9827-9832. [CrossRef]

- Sokurenko, E.V.; Chesnokova, V.; Dykhuizen, D.E.; Ofek, I.; Wu, X.-R.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Struve, C.; Schembri, M.A.; Hasty, D.L. Pathogenic adaptation of Escherichia coli by natural variation of the FimH adhesin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95(15), 8922-8926. [CrossRef]

- Hojati, Z.; Zamanzad, B.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Molaie, R.; Gholipour, A. The FimH gene in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from patients with urinary tract infection. Jundishapur journal of microbiology 2015, 8(2),. [CrossRef]

- Maluta, R.P.; Logue, C.M.; Casas, M.R.T.; Meng, T.; Guastalli, E.A.L.; Rojas, T.C.G.; Montelli, A.C.; Sadatsune, T.; de Carvalho Ramos, M.; Nolan, L.K. Overlapped sequence types (STs) and serogroups of avian pathogenic (APEC) and human extra-intestinal pathogenic (ExPEC) Escherichia coli isolated in Brazil. PloS one 2014, 9(8), e105016. [CrossRef]

| Sample source | No. of positive samples/ no. of total samples (%) | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Beef | 30/53 (56.6) | 185 |

| Pork | 30/51 (58.8) | 139 |

| Chicken | 20/51 (39.2) | 88 |

| Total | 80/155 (51.6) | 412 |

| Antimicrobial agents | Beef | Pork | Chicken | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (%) | I (%) | R (%) | S (%) | I (%) | R (%) | S (%) | I (%) | R (%) | |

| Cefotaxime | 149 (80.5) | 15 (8.1) | 21 (11.4) | 106 (76.3) | 29 (20.9) | 4 (2.9) | 72 (81.8) | 11 (12.5) | 5 (5.7) |

| Ceftazidime | 155 (83.8) | 13 (7.0) | 17 (9.2) | 106 (76.3) | 29 (20.9) | 4 (2.9) | 80 (90.9) | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Imipenem | 55 (29.7) | 13 (7.0) | 117 (63.2) | 3 (2.2) | 16 (11.5) | 120 (86.3) | 4 (4.5) | 11 (12.5) | 73 (83.0) |

| Meropenem | 84 (45.4) | 44 (23.8) | 57 (30.8) | 31 (22.3) | 57 (41.0) | 51 (36.7) | 20 (22.7) | 34 (38.6) | 34 (38.6) |

| Isolate code | uidA | Carbapenemase gene | Antimicrobial resistance pattern | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A | Class B | Class D | |||||

| blaKPC | blaNDM | blaVIM | blaIMP | blaOXA-48 | |||

| B14.1 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.2 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.3 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.4 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.5 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.6 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.7 | + | - | + | + | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.8 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.9 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.10 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.11 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.12 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.13 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.14 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| B14.15 | + | - | + | - | - | - | CTX, CAZ, IPM, MEM |

| Isolate code | DEC indicator gene | ExPEC indicator gene | Other E. coli virulence gene | Phylogenetic group | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEC and EHEC | ETEC | EAEC | EIEC | DAEC | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | ||||||||||||||||

| stx1 | stx2 | eae | bfpA | elt | est | aggR | ipaH | daaE | papA | papC | sfaDE | afa | kpsMT II | iutA | agn43 | astA | cnf1 | fimH | hlyA | lpf | chuA | yjaA | TSPE4.C2 | Group | |

| B14.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

| B14.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).