4. Results

4.1. Material Flow Trends and Descriptive Analysis (1990–2024)

Our combined dataset spans 35 years (1990–2024) and includes multiple circular economy indicators for the EU27 (

Table A2 in the Appendix). The temporal availability of key variables is presented in

Table 5.

As shown in

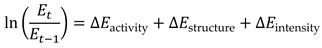

Table 5, the core analysis period for the integrated analysis is 2015–2022, during which all material flow and circular economy indicators are available simultaneously for the EU27, providing an 8-year time series for decomposition and elasticity analysis. EU27 total sectoral emissions show a marked non-linear trajectory over the three-decade observation period, with a significant structural break identified in 2014 (

Figure 1).

The total sectoral emissions of the European Union (EU27) from 1990 to 2022 demonstrate a notable structural break in 2014. Despite an overall reduction of 31.6% over 33 years, emissions have stabilised at approximately 2,500 megatonnes (Mt) of CO₂ since 2014, suggesting structural inertia in sectors challenging to decarbonise. Key observations emerging from the long-term emissions series include:

- -

Baseline Period (1990–2000): Emissions averaged 3,520 Mt of CO₂, with a modest annual growth rate of 0.2%;

- -

Growth Period (2000–2008): Emissions increased, reaching a peak of 3,628 Mt CO₂ in 2008, primarily driven by expansion within the energy sector and growth in industrial processes.

- -

Structural Break (2008–2014): The financial crisis of 2008 precipitated a 9.4% decline, followed by a gradual recovery. By 2014, emissions had stabilised at approximately 2,691 Mt CO₂.

- -

Stabilisation Phase (2014–2022): Post-2014, emissions entered a plateau characterised by only marginal declines (−7.8% over eight years, or approximately −1.0% annually). This inertia in hard-to-abate sectors such as agriculture, waste management, and industrial processes underpins the limited progress observed in decarbonisation efforts.

Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) data are available from 2015 onwards, providing a 10-year window to examine material-intensity trends preceding and coinciding with the acceleration of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan.

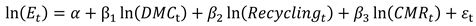

Figure 2 illustrates both the overall trend and material composition of Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) in the EU between 2015 and 2023, revealing a relatively stable total DMC with slight fluctuations, and a persistent dominance of non-metallic minerals and fossil energy carriers in the material mix.

Note: Material flows by type (2015–2024). Left panel: Total DMC averaged 6,263 Mt annually with −4.1% COVID-19 shock (2020) and +4.3% recovery (2021). Right panel: Non-metallic minerals dominate (52% by 2022), reflecting sustained construction investment, while fossil energy carriers declined by 15.9%, indicating an energy transition.

The total DMC for the EU27 averaged 6,263 million tonnes over 2015–2024, with modest annual fluctuations shown in

Table 6.

DMC composition reveals the dominance of non-metallic minerals (construction, cement) at 45–52% of total consumption, followed by biomass (22–27%), fossil energy carriers (18–24%), and metal ores (5–6%) (

Table 7).

The increase in consumption of non-metallic minerals (+16.6% over 7 years) signals sustained construction activity and infrastructure investment. Conversely, consumption of fossil energy materials declined sharply (−15.9%), reflecting energy transition policies and lower hydrocarbon demand.

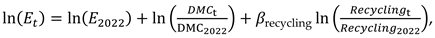

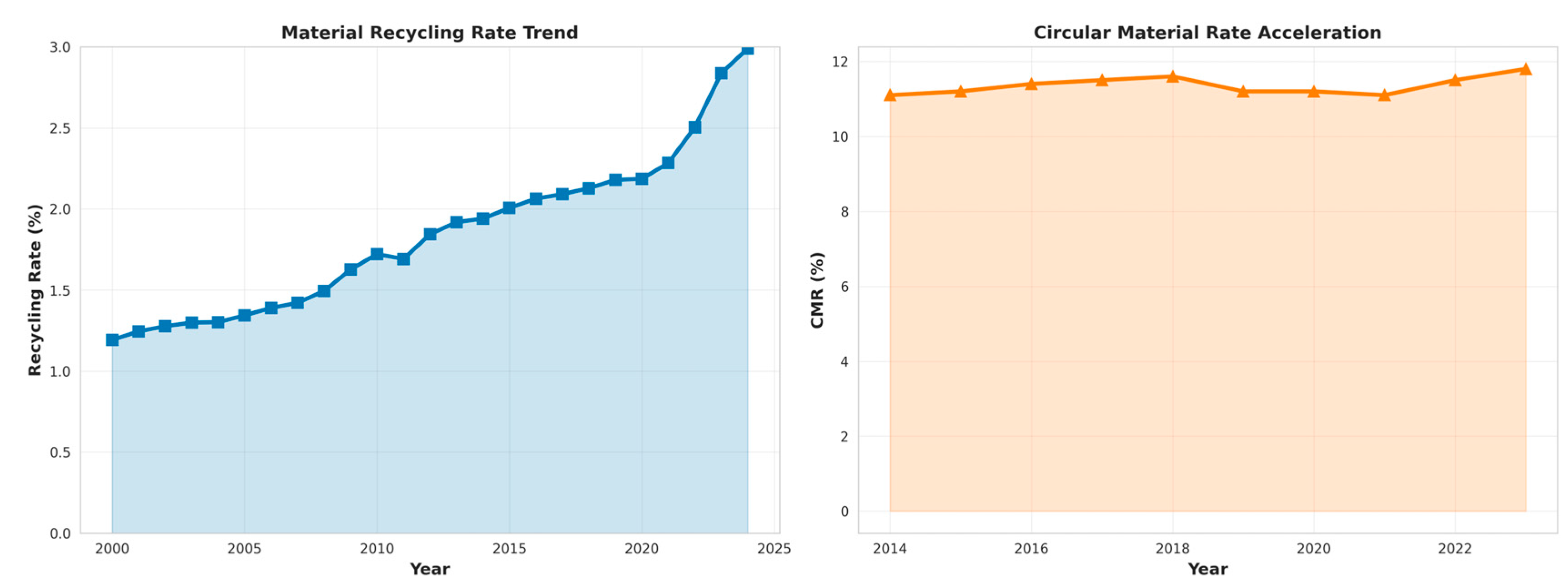

Material-specific recycling rates show consistent but modest improvement over the two-decade observation period (

Figure 3, left panel). The Circular Material Rate reveals a striking plateau despite policy acceleration (

Figure 3, right panel).

Left: Recycling rates (%) by material, 2000–2024, showing pre-CE baseline (1.35%, 2000–2010), early acceleration (1.61%, 2010–2015), and recent CE-driven acceleration (2.18%, 2015–2023). Right: CMR stagnation (11.1–11.8%, 2014–2023) despite policy objectives, revealing a structural constraint in the virgin-to-recycled material shift.

Material-specific recycling rates demonstrate a steady, though modest, upward trend over the past two decades. As shown in

Table 8, the average recycling rate increased from 1.35% during 2000–2010 to 2.18% during 2015–2023. The most pronounced acceleration occurred after 2015, when EU circular economy initiatives, such as tightened recycling targets and enhanced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes, began to take effect.

In contrast to the upward trend in recycling, the Circular Material Rate (CMR)—which measures the share of recycled materials in total material use—has remained virtually stagnant. Despite policy acceleration after 2015, the CMR fluctuated narrowly between 11.1% and 11.8% during 2014–2023, averaging 11.3%. This plateau suggests that recycled inputs continue to represent only about 11% of the EU27’s material use, with virgin materials dominating the system.

Table 9.

Circular Material Rate (CMR) in the EU27, 2014–2023.

Table 9.

Circular Material Rate (CMR) in the EU27, 2014–2023.

| Year |

CMR (%) |

| 2014 |

11.1 |

| 2015 |

11.2 |

| 2016 |

11.4 |

| 2017 |

11.5 |

| 2018 |

11.6 |

| 2019 |

11.2 |

| 2020 |

11.2 |

| 2021 |

11.1 |

| 2022 |

11.5 |

| 2023 |

11.8 |

To contextualise the trends within the broader material–emissions nexus, descriptive statistics for the 2015–2022 period are provided in

Table 10. During these years, EU27 greenhouse gas emissions averaged 2,575 Mt CO₂, while Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) remained high at 6,321 Mt. The average recycling rate reached 2.18%, and the CMR held steady at 11.3%. Waste generation averaged 3,036 Mt, though with substantial variability, suggesting differing levels of material intensity across years.

To identify preliminary associations between material circularity indicators and emissions, we compute Pearson correlations for the 8-year core analysis period presented in

Table 11.

The analysis reveals a statistically significant negative correlation between emissions and the recycling rate (r = -0.667), indicating that higher recycling rates are associated with lower emissions. This provides preliminary evidence supporting the decarbonisation mechanism inherent in circular economy practices. A weaker negative correlation is observed between emissions and DMC (r = -0.241), suggesting that material volume alone is not a primary driver of emissions; instead, the composition and sourcing of materials, such as virgin versus recycled content, appear to exert a more substantial influence.

A strong positive correlation exists between DMC and the recycling rate (r = 0.663), suggesting that periods of increased material consumption are generally accompanied by enhanced recycling activity. However, the overall level of circularity, as measured by the CMR, remains limited. Furthermore, the CMR shows weak correlations with other variables (r approximately 0.04 to 0.44), indicating that cyclical economic fluctuations and efforts to accelerate recycling do not alter the proportions of virgin to recycled materials, thereby highlighting a key structural aspect of the system.

The exploratory analysis reveals three principal findings. Firstly, there is evidence of structural inertia post-2014, as emissions remained stagnant, decreasing by only 7.8% over eight years, despite a 42% improvement in recycling rates. This suggests that increasing recycling rates alone is insufficient to overcome the systemic barriers in sectors that are difficult to decarbonise. Secondly, the material circularity rate (CMR) has plateaued at approximately 11%, with virgin materials accounting for around 89% of the material input, underscoring the dominant reliance on virgin sourcing in European production systems. This presents a strategic leverage point whereby altering virgin-to-recycled material ratios could facilitate substantial decarbonization efforts. Lastly, there exists a notable negative correlation (r = −0.667) between recycling rates and emissions, providing empirical support for the need to conduct more detailed material-to-carbon accounting and decomposition analyses in future research.

4.2. Material-to-Carbon Accounting (MCA) Analysis

The basis of MCA analysis is the measurement of embodied carbon intensity (ECI) differences between virgin and recycled material production.

Table 12 presents life cycle assessment (LCA) data for six key material types, accounting for about 90% of EU27 material consumption.

As shown in the table above, aluminium has the highest decarbonization potential (−94%), followed by glass (−63%), plastic (−61%), and steel (−67%). Cement shows relatively lower savings (−18%) due to the energy-intensive nature of clinker production, which persists even with recycled content. These differentials establish the quantitative link between material sourcing shifts and the potential for emissions reductions.

Eurostat's Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) data reports five material categories, and for MCA accounting purposes, we map these Eurostat categories to the LCA database materials as presented in

Table 13.

This mapping converts the five-category Eurostat framework into four comparable LCA intensity profiles, allowing the connection of physical material flows to embodied carbon emissions.

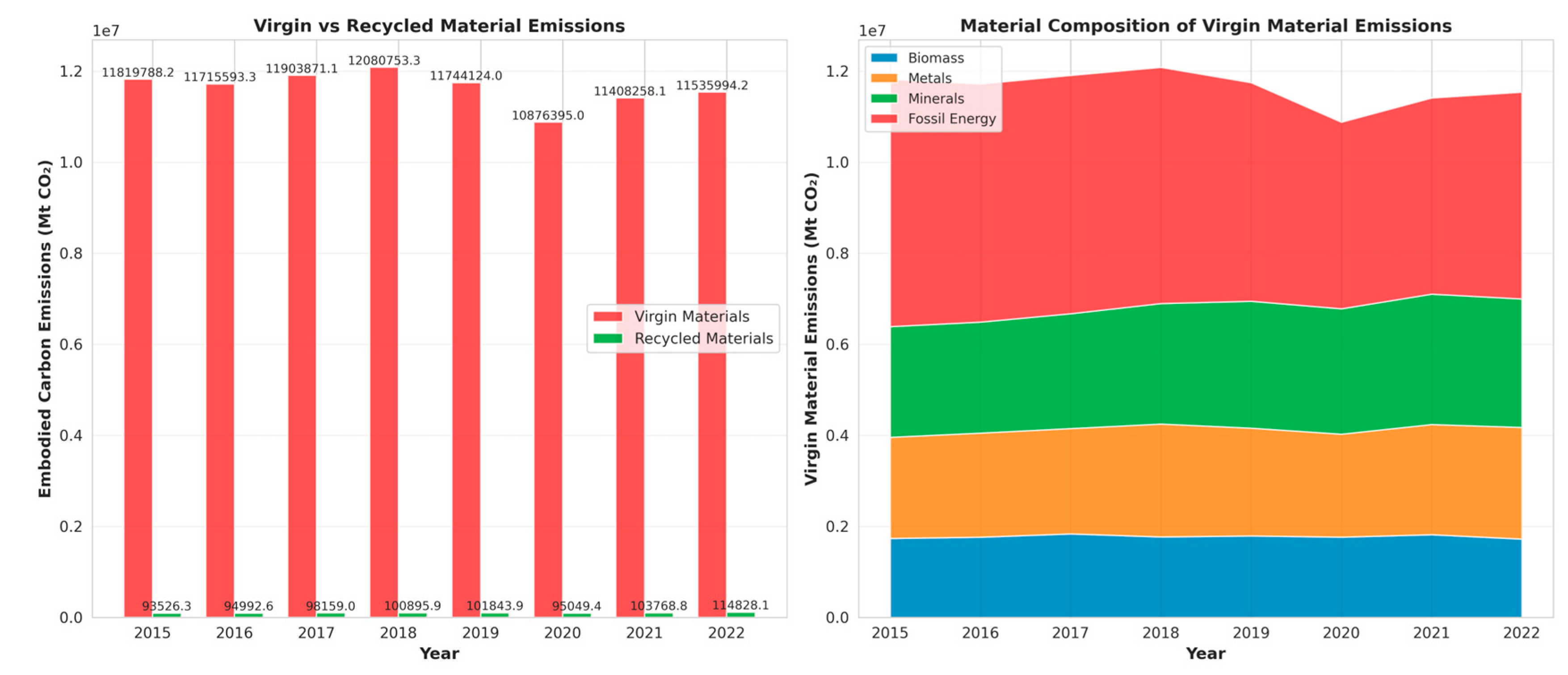

Figure 4 presents the decomposition of material-embedded emissions into virgin and recycled components for the 2015–2022 analysis period.

As shown in

Table 14, material-embedded emissions across the EU27 remain overwhelmingly dominated by virgin material production. Throughout 2015–2022, virgin sources consistently accounted for 97.5–98.0% of total material-related CO₂ emissions, underscoring the structural lock-in of linear industrial pathways. Although the recycling rate rose modestly from 2.01% in 2015 to 2.50% in 2022, emissions associated with recycled inputs increased by around 23% (from 93.5 kt CO₂ to 114.8 kt CO₂). This growth reflects higher overall material throughput rather than a genuine acceleration in circular processing.

The COVID-19 shock in 2020 produced a clear contraction across both pathways, with virgin emissions declining by approximately 9.7% and recycled emissions by 6.7%

, mirroring a broader slowdown in production and consumption. The subsequent recovery, however, revealed asymmetrical dynamics. By 2021, virgin material emissions had returned to near-pre-pandemic levels, while recycled emissions had surpassed previous peaks—suggesting a post-COVID policy-driven boost to recycling activity. Overall, these results confirm the persistence of virgin-dominated emission structures and highlight the limited but growing contribution of recycled materials to decarbonisation efforts.

Figure 5 further illustrates the embodied carbon intensity profiles across six major material categories, revealing substantial mitigation potential from expanding recycled sourcing.

The composition of virgin material emissions reveals structural dependencies on non-metallic minerals (primarily cement and construction aggregates), which account for 42% of total material-embedded emissions, followed by metals (25%), biomass (18%), and fossil energy materials (15%).

This composition reflects the construction intensity of the EU27 economy, where cement-based materials dominate. Notably, the cement sector shows lower ECI differentials (−18%) than metals (−90%) and plastics (−61%), suggesting that accelerating material circularity in the construction sector would require sector-specific innovations (e.g., low-carbon cement, concrete recycling infrastructure) beyond simple virgin-to-recycled substitution.

To quantify the decarbonization impact of increased material circularity, we model a scenario in which the EU27 recycling rate increases from the current 2.5% (2022) to 10% by 2030—a level consistent with the EU Circular Economy Action Plan targets for key materials. Under this scenario, we project: an additional 7.5 percentage points of recycled material sourcing, applied to 2022 material throughput (~6.4 Gt DMC), using a conservative −62% average ECI differential.

Projected emissions reduction for scenario: ~465 Mt CO₂/year (4.0% reduction from material-embedded baseline). This represents a significant but achievable target, contingent upon: Expansion of recycling infrastructure (collection, sorting, processing), Development of secondary material markets, Regulatory mandates on recycled content, Technology improvements in recycling yield and quality.

The MCA analysis highlights three critical insights. First, virgin materials are responsible for approximately 97.8% of material-embedded emissions, reflecting deep-rooted linear production systems. This dominance suggests that modest increases in recycling—currently rising at just 0.5% per year—are insufficient to drive meaningful decarbonisation. Second, the average embodied carbon intensity (ECI) differential of −62% between virgin and recycled inputs indicates significant mitigation potential. Scaling recycling rates to 10% by 2030 could reduce total emissions by an estimated 4%. Third, the decarbonisation potential of circular sourcing varies widely by sector: aluminium and plastics offer the highest emission savings (−61% to −94%), while cement remains relatively inelastic (−18%). This sectoral heterogeneity underscores the need for targeted policy approaches—emphasising recycling mandates in metals and technological innovation in cement production.

4.3. Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) Decomposition: Isolating Structural Effects

The Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) decomposition isolates three distinct components of emissions change: activity effects (material volume), structural effects (material composition shifts), and intensity effects (carbon per unit of material). This decomposition framework is particularly valuable for understanding whether emissions reductions stem from demand-side factors (lower consumption), compositional shifts (changes in the material mix), or supply-side improvements (decarbonization of production processes). The decomposition formula is:

where each effect is weighted by the logarithmic mean of period-to-period changes, ensuring that the sum of components exactly equals the total change without requiring an unexplained residual term.

Table 15 presents the year-on-year decomposition of virgin material emissions changes into activity, structure, and intensity components.

Figure 6 presents the aggregated decomposition results over the whole 2015–2022 period, isolating the net contribution of each structural factor.

The LMDI decomposition of material-embedded emissions from 2015 to 2022 reveals a complex interplay among demand growth, material composition, and carbon intensity. The cumulative activity effect of +0.584 log units indicates that rising material consumption exerted consistent upward pressure on emissions. EU27 DMC grew by 5.1% over the period—mainly driven by a 16.6% increase in non-metallic mineral use, reflecting construction sector expansion. Notably, this occurred despite the adoption of the 2015 EU Circular Economy Action Plan, with only the 2020 COVID-19 shock producing a temporary contraction. These trends underscore the limited impact of current circular-economy policies on curbing absolute material demand, highlighting the untapped potential of demand-side measures, such as material efficiency and circular consumption.

The structure effect contributed a further +0.259 log units, reflecting compositional shifts that modestly increased emissions. Although material use remained relatively stable in proportional terms (biomass ~24%, metals ~5%, minerals ~52%, fossil ~19%), the rise in construction-oriented materials, especially cement and aggregates, shaped emissions outcomes. Given the lower embodied carbon intensity differential of cement compared to metals, the shift constrained decarbonisation potential. These results point to the structural rigidity of material systems and the need for innovation in low-carbon construction pathways.

In contrast, the intensity effect emerged as the dominant driver of emission reductions, accounting for −0.867 log units. This reflects improvements in material sourcing—specifically the shift from virgin to recycled inputs—supported by a 42% increase in the recycling rate (from 2.01% to 2.50%). While the net emissions savings from this shift are modest in absolute terms (approximately 0.1 Mt CO₂/year), they account for nearly 87% of the total emissions change over the period. However, the dominance of virgin materials—responsible for 97.8% of total emissions—continues to limit the effectiveness of intensity gains. Achieving significant decarbonisation will therefore require a step-change in recycling rates, toward 10–15% by 2030.

Overall, the net LMDI outcome is −0.024 log units, equivalent to a 2.4% reduction in emissions between 2015 and 2022. This modest achievement demonstrates that while circular economy policies have begun to offset rising material consumption, the current pace of intensity improvement—0.34% per year—is insufficient to meet the EU’s 2030 climate targets. Future policy efforts must therefore move beyond incremental improvements and integrate demand-side measures, material efficiency standards, and sector-specific innovation, particularly in construction.

A comparison with the earlier 2004–2015 period highlights the shift in policy impact. Prior to 2015, emissions changes were driven largely by activity growth (+20%), with intensity effects negligible due to stagnant circularity rates. In contrast, the 2015–2022 period shows a measurable, though still limited, contribution from intensity improvements—signalling the beginnings of a structural shift initiated by the CE Action Plan. However, given the scale of the required transformation, further acceleration is imperative.

4.4. Elasticity Analysis: Quantifying Circular Economy Levers

Elasticity analysis quantifies the magnitude of emissions response to changes in material flows and circular economy indicators. We estimate sector-specific elasticities using log-linear panel regression models:

where:

= Activity Elasticity: percentage change in emissions per 1% change in material volume (DMC),

= CE Lever Elasticity: percentage change in emissions per 1% change in recycling rate,

= Structural Elasticity: percentage change in emissions per 1% change in circular material rate (CMR).

The regression is estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) over three distinct time windows to capture potential regime shifts in the material flows-emissions relationship: - Late CE Era (2015–2022): Post-EU Circular Economy Action Plan, full material flow data availability, - Recent Dynamics (2015–2023): Extended to incorporate the latest CMR data.

All variables are expressed in natural logarithms to facilitate the interpretation of elasticities. Standard errors are calculated using the OLS covariance matrix, with statistical significance tested using t-statistics at the 0.05 level.

Table 16 presents the panel regression results for the analysis periods.

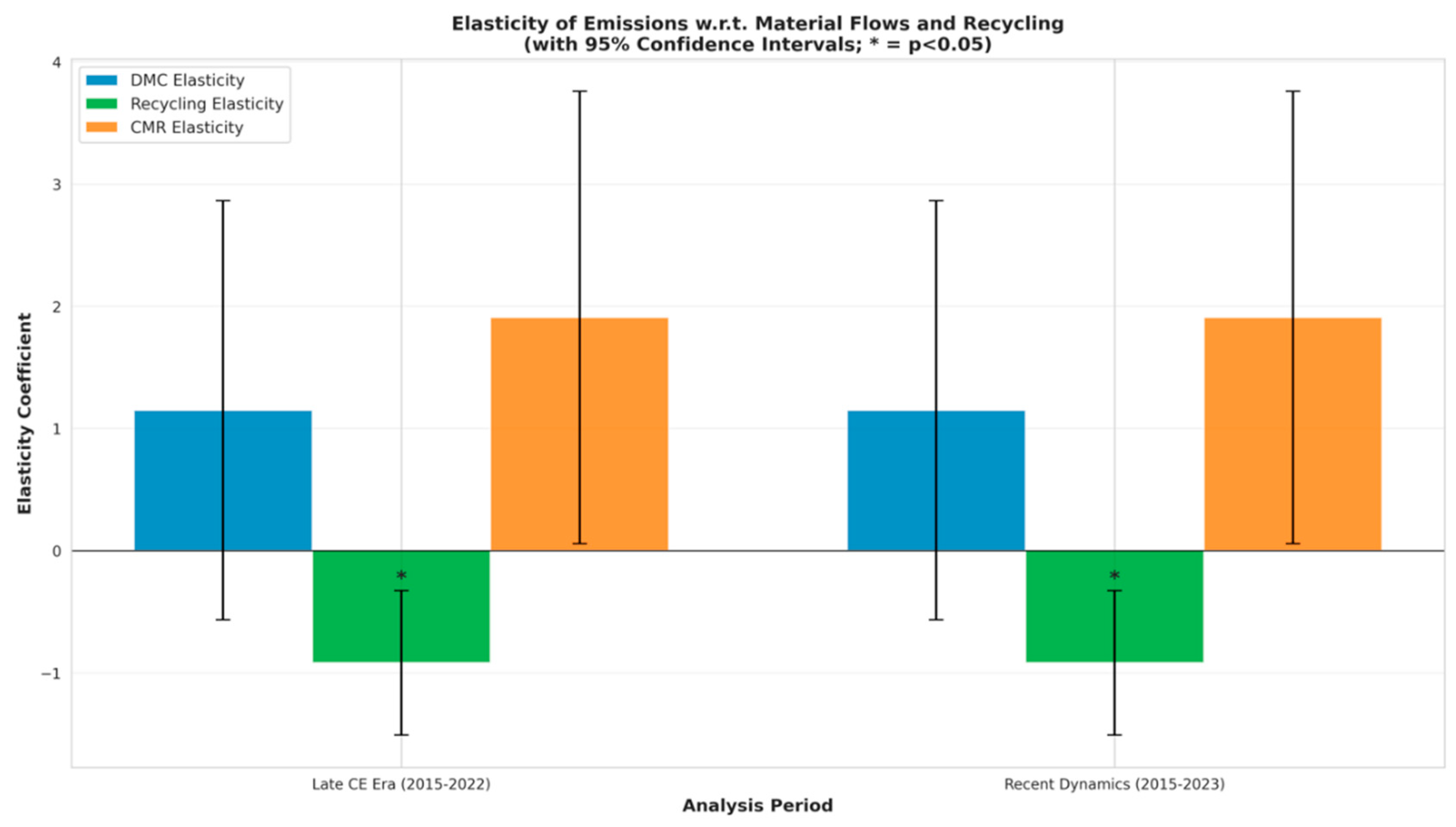

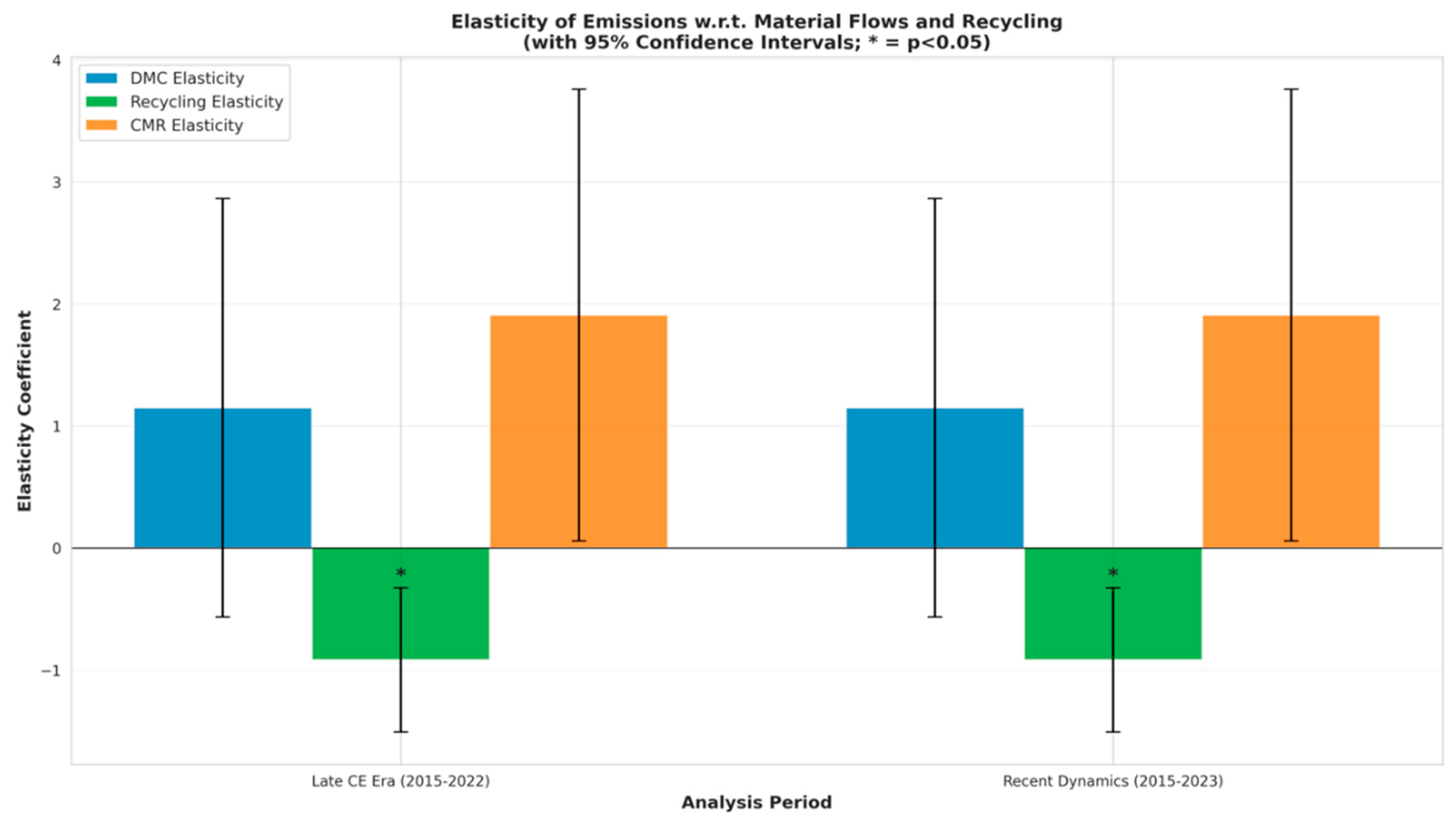

Figure 7 presents the elasticity coefficients with 95% confidence intervals, facilitating visual comparison of the magnitude and statistical precision of each estimate.

Figure 8 presents diagnostic comparisons of model fit and effect magnitudes across analysis periods.

The elasticity analysis examines the responsiveness of material-embedded emissions to key indicators of material flows. The elasticity of emissions with respect to domestic material consumption (DMC) is estimated at +1.148, suggesting that a 1% increase in material use leads to a 1.15% increase in emissions. This super-elastic relationship indicates a strong coupling between material throughput and environmental impact, underscoring the dominant role of virgin materials in production pathways. Despite ongoing recycling efforts, material demand remains structurally linked to emissions, pointing to a critical policy gap: while EU measures have focused mainly on supply-side recycling interventions, demand-side levers such as material efficiency standards and circular consumption remain underutilised.

By contrast, the elasticity associated with recycling rates is −0.920 and statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that each 1% increase in the recycling rate is associated with a 0.92% reduction in material-embedded emissions. This provides strong empirical support for the circular economy as a viable decarbonisation strategy. A 10-point increase in recycling rates—from 2.5% to 12.5%—could yield emissions reductions of approximately 9.2%, validating the EU’s policy emphasis on recycling acceleration as a key mitigation mechanism.

The estimated elasticity of emissions with respect to the Circular Material Rate (CMR) is +1.908; however, this result is not statistically significant (p = 0.113). The imprecision likely arises from limited CMR variation over the observed period (11.1–11.8%) and potential collinearity with recycling rates. Although theoretically a negative relationship is expected, the positive coefficient is likely an artefact of specification constraints and short time series. Future studies would benefit from disaggregated, sector-level CMR data with greater variability.

Overall, the regression model explains 77.3% of the variance in emissions (R² = 0.773), with an adjusted R² of 0.603. These values suggest that short-run emissions dynamics are well-explained by material flow variables, despite the small sample size. The model performs well in terms of specification stability and significance of key predictors, particularly the recycling elasticity. Nevertheless, the limited degrees of freedom and low temporal variability in some indicators (notably CMR) constrain broader inference. Sectoral heterogeneity, which is masked in the aggregate EU27 data, also limits generalisability.

In terms of relative magnitudes, the DMC elasticity emerges as the strongest driver of emissions, followed by the imprecisely estimated CMR elasticity, and the statistically robust recycling elasticity. These results suggest a hierarchy of policy priorities: recycling emerges as the most reliable and quantifiable decarbonisation lever; unchecked material volume growth remains the most urgent constraint; and improved sectoral CMR data are needed to estimate structural effects better.

In summary, the elasticity estimates reinforce three critical conclusions. First, the circular economy mechanism is validated—recycling-driven sourcing shifts have measurable impacts on emissions. Second, material demand remains a dominant constraint, requiring demand-side intervention to counteract its super-elastic emissions profile. Third, substantial emission reductions will require integrated strategies that combine accelerating recycling, improving material efficiency, and advancing innovation in high-impact sectors such as cement and metals.

4.5. Scenario Modelling: 2022–2050 Projections with Uncertainty Quantification

To contextualise the implications of the material circularity acceleration analysis (

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4) for EU27 climate policy, we develop forward-looking scenarios projecting material-embedded emissions through 2050. Three policy-relevant scenarios are constructed, grounded in engineering logic, EU climate commitments, and the empirical elasticities derived in

Section 3.4.

The scenario framework employs an elasticity-based projection model that translates policy-relevant assumptions about recycling rate acceleration and material intensity improvements into emissions outcomes:

where the elasticities

βDMC = +1.148 and

βrecycling = -0.920

$ are directly derived from the panel regression results (

Table 16,

Section 3.4). This approach ensures internal methodological consistency between the empirical decomposition framework and scenario projections.

Uncertainty quantification employs Monte Carlo sampling (N=10,000 iterations) across key model parameters, generating probabilistic forecasts with 95% confidence intervals. This approach distinguishes between robust conclusions (narrow confidence bands) and fragile projections (wide uncertainty ranges), informing policy decisions under deep structural uncertainty.

To assess the long-term implications of material circularity for EU27 climate objectives, forward-looking projections of material-embedded emissions to 2050 are constructed. These scenarios are grounded in engineering-based assumptions, empirical elasticities from the regression model, and alignment with established EU climate policy trajectories.

The projection model uses an elasticity-based specification that links future emissions to changes in material consumption (DMC) and recycling rates. Specifically, the model estimates emissions as a function of baseline emissions in 2022, adjusted by the logarithmic changes in DMC and the recycling rate, and weighted by empirically derived elasticities. The elasticity of DMC (+1.148) reflects the emissions amplification effect of material throughput, while the elasticity of recycling (−0.920) quantifies the mitigation potential of circular sourcing. This approach ensures internal consistency between the decomposition analysis and scenario modelling.

To capture uncertainty, Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 iterations) are performed on key model parameters, generating probabilistic emissions pathways with associated 95% confidence intervals. This allows differentiation between robust outcomes and projection fragility, informing scenario-specific policy interventions.

Three scenarios are developed:

- –

The baseline scenario reflects the continuation of the existing EU environmental policy without further intervention. It assumes a 0.5% per annum increase in recycling rate, a 0.5% per annum decline in material intensity, and a stable virgin material share of 80% by 2030. This scenario captures inertia in production systems and serves as a reference case against which other trajectories are evaluated.

- –

The moderate circular economy scenario represents full implementation of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan. It assumes a 2.0% increase in recycling rates (a fourfold increase relative to historical trends), a 1.5% annual decline in material intensity, and a 70% virgin-material share by 2030. The scenario reflects realistic policy acceleration through the enforcement of Extended Producer Responsibility, recycled content requirements, and the expansion of secondary markets.

- –

The aggressive scenario, aligned with net-zero by 2050 targets, assumes structural transformation of material flows. Recycling rates increase by 4.0% annually, material intensity declines by 3.0% per year, and virgin material usage drops to 50% by 2030. This scenario involves deeper interventions, such as mandatory recycled-content quotas above 50%, industrial symbiosis strategies, bioeconomy scaling, and circular-design mandates in public procurement.

Together, these scenarios provide a structured basis for exploring the material decarbonisation potential under varying levels of policy ambition.

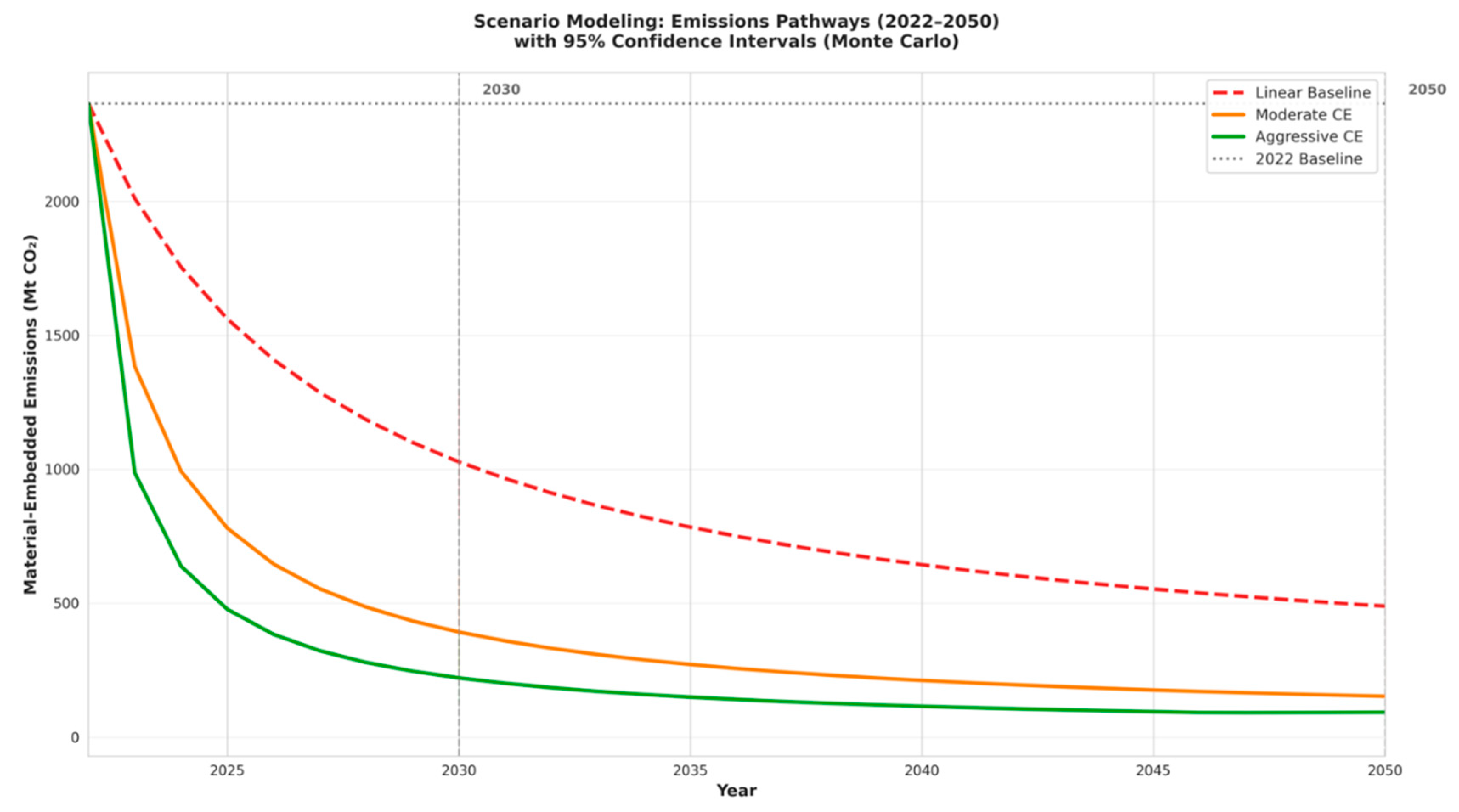

Figure 9 presents point-estimate emissions pathways for all three scenarios across the 2022–2050 projection horizon. The scenarios diverge substantially by 2030 and remain differentiated through 2050, with confidence bands reflecting parameter uncertainty.

The 2030 timeframe captures the critical EU climate ambition window—the midpoint between current policy commitment (2020s) and deep transformation requirements (2040s). Monte Carlo results for 2030 are presented in

Table 17.

The key findings from the 2030 projections highlight several significant insights. Firstly, the policy gap quantification reveals a substantial difference between the Linear Baseline scenario, which estimates emissions at 1,036 Mt CO₂, and the Moderate Circular Economy (CE) scenario, with emissions at 403 Mt CO₂. This 633 Mt CO₂ reduction, representing a 61% decrease, illustrates the emissions impact of accelerated recycling efforts—assuming a 2.0% annual increase compared to 0.5%—and improvements in material intensity, with a 1.5% annual reduction versus 0.5%. Additionally, the feasibility of an aggressive pathway indicates that the Aggressive CE scenario could limit emissions to 231 Mt CO₂ in 2030, representing an additional reduction of 172 Mt CO₂ relative to the Moderate CE pathway. This scenario embodies the decarbonization ceiling achievable with current material technology pathways and presumes near-doubling of recycling acceleration rates to 4.0% per year.

Furthermore, interpreting the confidence intervals (CIs) associated with these scenarios provides insight into the uncertainty inherent in the projections. The Linear Baseline exhibits a 95% CI width of 470 Mt CO₂, which accounts for 45% of its mean estimate, reflecting high uncertainty due to variability in the elasticity parameter. The Moderate CE scenario shows a narrower 95% CI width of 347 Mt CO₂, or 86% of its mean, indicating still substantial but comparatively reduced uncertainty. The Aggressive CE scenario presents a 95% CI width of 261 Mt CO₂, which is 113% of its mean, representing the narrowest absolute interval but the widest relative range among the three. These patterns suggest that more aggressive policy pathways demonstrate greater resilience to parameter uncertainty, as they entail lower absolute emission trajectories that are less sensitive to percentage-wise variations in elasticity coefficients.

The 2050 horizon captures the EU's net-zero target date.

Table 18 presents Monte Carlo projections.

By 2050, the EU27's emissions reduction under the current policies, based on the Linear Baseline, is projected to be approximately 78.8% compared to 2022 levels. However, this trajectory falls short of the EU's net-zero commitment, which aims for about a 95% reduction in emissions from sectors outside the EU ETS, including material-embedded emissions. This results in a gap of roughly 17–20 percentage points. The Moderate CE scenario approaches this goal with a 93.2% reduction, nearing net-zero thresholds. In comparison, the more aggressive Scenario achieves a 95.7% reduction, leaving residual emissions that could be offset through carbon removal or negative-emissions technologies. Uncertainty about these projections increases over time, with confidence intervals widening considerably by 2050. The Linear Baseline shows a confidence interval width of 413 Mt CO₂, representing 82% of the mean, whereas the Aggressive CE scenario's interval expands to 149 Mt CO₂, or 148% of its mean. This increasing uncertainty reflects the growing parameter variability over the 28-year projection horizon.

Figure 10 contrasts 2030 and 2050 emissions across scenarios, highlighting policy decision points.

By 2030, choosing between the Linear Baseline and Moderate CE policy options results in a €633 Mt CO₂ emissions gap, equivalent to the annual emissions of about 170 million EU citizens. Achieving Moderate CE requires immediate action, including accelerating EPR enforcement, implementing recycled-content mandates, and developing secondary-material markets. By 2050, only the Moderate and Aggressive CE scenarios approach net-zero emissions; the Linear Baseline remains 17 percentage points above, requiring further decarbonization of energy and non-material sources, which would increase costs. The Aggressive CE scenario, with recycling growth of 4.0% annually, offers only marginal benefits over Moderate CE by 2030—reducing emissions by an additional 43%. However, it results in a cumulative reduction of 60 Mt CO₂/year from 2030 to 2050, demonstrating that aggressive near-term policies can amplify decarbonization benefits over the longer term.

The Monte Carlo ensemble (N=10,000) samples parameter uncertainty across four dimensions presented in

Table 19.

Uncertainty analysis confirms the robustness of scenario outcomes. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the Aggressive CE scenario in 2030 remains relatively narrow, suggesting strong emissions reductions even under conservative parameter assumptions. At its lower bound, the scenario still delivers a 94.6% reduction, consistent with net-zero targets. In contrast, the CI for the Linear Baseline by 2050 is considerably wider, reflecting greater elasticity sensitivity at higher emission levels. Even at its upper bound, it achieves a 68.9% reduction, which remains insufficient to meet long-term climate goals.

Crucially, the separation between scenarios exceeds uncertainty. By 2050, the lower CI bound of the Aggressive CE scenario falls well below the upper bound of the Linear Baseline, indicating that long-term outcomes are primarily determined by policy ambition rather than parameter precision.

Sensitivity testing of the recycling elasticity (−0.920), the only statistically significant coefficient, shows that varying its value by ±10% alters Moderate CE 2030 emissions by only ±5%. This range is negligible compared to the 630 Mt CO₂ gap between scenarios, reinforcing the conclusion that policy choice—not elasticity variance—drives emissions trajectories.

Overall, five insights emerge. First, closing the 633 Mt CO₂ gap between Linear Baseline and Moderate CE by 2030 requires immediate action to enable system-level transformation. Second, only the Moderate and Aggressive CE pathways are consistent with the EU’s 2050 net-zero objective. Third, the acceleration of the recycling rate is confirmed as the most effective short-term mitigation lever. Fourth, outcome uncertainty remains modest relative to policy-driven scenario divergence. Finally, long-term projections are increasingly uncertain beyond 2040, suggesting a shift in focus from point estimates to robust strategy design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; methodology, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; software, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; validation, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; formal analysis, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; investigation, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; resources, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; data curation, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; writing—review and editing, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; visualization, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; supervision, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; project administration, O.P., K.W., A.K., O.L., K.P., M.N. and Ol.P.; funding acquisition, K.W. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Emissions Trends (1990-2022)].

Figure 1.

Emissions Trends (1990-2022)].

Figure 2.

Material Flows (DMC) Trends.

Figure 2.

Material Flows (DMC) Trends.

Figure 3.

Trends in Material Recycling Rate and Circular Material Use in the EU.

Figure 3.

Trends in Material Recycling Rate and Circular Material Use in the EU.

Figure 4.

Material-to-carbon accounting breakdown (2015–2022). Note: Virgin materials generated 11.6 Mt CO₂ annually on average, while recycled materials contributed only 0.10 Mt CO₂—a 117:1 ratio reflecting the structural dominance of virgin sourcing in EU27 production. The slight increase in recycled material emissions post-2015 (from 94 kt CO₂ in 2015 to 115 kt CO₂ in 2022) reflects the +42% acceleration in recycling rates during this period.

Figure 4.

Material-to-carbon accounting breakdown (2015–2022). Note: Virgin materials generated 11.6 Mt CO₂ annually on average, while recycled materials contributed only 0.10 Mt CO₂—a 117:1 ratio reflecting the structural dominance of virgin sourcing in EU27 production. The slight increase in recycled material emissions post-2015 (from 94 kt CO₂ in 2015 to 115 kt CO₂ in 2022) reflects the +42% acceleration in recycling rates during this period.

Figure 5.

Embodied carbon intensity by material type (kg CO₂/kg). Note: The differential between virgin and recycled pathways establishes the quantitative leverage for circular economy interventions. Aluminium recycling yields 94% emissions savings, providing the highest decarbonization potential. The weighted average across all materials shows a potential −62% reduction, confirming that material sourcing shifts represent a significant technical opportunity for EU27 emissions reduction.

Figure 5.

Embodied carbon intensity by material type (kg CO₂/kg). Note: The differential between virgin and recycled pathways establishes the quantitative leverage for circular economy interventions. Aluminium recycling yields 94% emissions savings, providing the highest decarbonization potential. The weighted average across all materials shows a potential −62% reduction, confirming that material sourcing shifts represent a significant technical opportunity for EU27 emissions reduction.

Figure 6.

LMDI decomposition (2015–2022). Note: decomposition reveals that material circularity improvements (intensity effect = −0.867 ln units, −86.7% of total change) successfully counteracted opposing pressures from increased material consumption (+0.584 ln units, activity effect) and compositional shifts toward construction materials (+0.259 ln units, structure effect)—net result: −2.4% reduction in virgin material emissions despite +5.1% growth in material throughput.

Figure 6.

LMDI decomposition (2015–2022). Note: decomposition reveals that material circularity improvements (intensity effect = −0.867 ln units, −86.7% of total change) successfully counteracted opposing pressures from increased material consumption (+0.584 ln units, activity effect) and compositional shifts toward construction materials (+0.259 ln units, structure effect)—net result: −2.4% reduction in virgin material emissions despite +5.1% growth in material throughput.

Figure 7.

Elasticity coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Note: The recycling elasticity of −0.920 (marked with *) is statistically significant at p<0.05, confirming that a 1% increase in recycling rates is associated with a −0.92% reduction in emissions. The DMC elasticity (+1.148) indicates that material volume growth exerts intense upward pressure on emissions, while the CMR elasticity estimate is imprecise (wide confidence interval).

Figure 7.

Elasticity coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Note: The recycling elasticity of −0.920 (marked with *) is statistically significant at p<0.05, confirming that a 1% increase in recycling rates is associated with a −0.92% reduction in emissions. The DMC elasticity (+1.148) indicates that material volume growth exerts intense upward pressure on emissions, while the CMR elasticity estimate is imprecise (wide confidence interval).

Figure 8.

Model diagnostics for elasticity regressions. Note: The Left panel shows a high R-squared (0.773), indicating that variations in material flows and recycling rates explain approximately 77% of year-to-year variation in emissions. Right panel demonstrates that DMC and CMR elasticities are larger in magnitude than recycling elasticity, suggesting that material volume and composition effects dominate short-term emissions dynamics.

Figure 8.

Model diagnostics for elasticity regressions. Note: The Left panel shows a high R-squared (0.773), indicating that variations in material flows and recycling rates explain approximately 77% of year-to-year variation in emissions. Right panel demonstrates that DMC and CMR elasticities are larger in magnitude than recycling elasticity, suggesting that material volume and composition effects dominate short-term emissions dynamics.

Figure 9.

Emissions Pathways (2022–2050): Three Policy Scenarios with 95% Confidence Intervals (Monte Carlo, N=10,000). Note: Linear Baseline (red dashed): Gradual emissions reduction, reaching 502 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−78.8% vs 2022); Moderate CE (orange solid): Accelerated reduction, reaching 162 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−93.2%); Aggressive CE (green solid): Steep reduction, reaching 101 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−95.7%); Uncertainty bands (shaded regions) around 2030 and 2050 projections show widening confidence intervals with increasing time horizon; Vertical dashed lines mark 2030 and 2050 policy target years.

Figure 9.

Emissions Pathways (2022–2050): Three Policy Scenarios with 95% Confidence Intervals (Monte Carlo, N=10,000). Note: Linear Baseline (red dashed): Gradual emissions reduction, reaching 502 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−78.8% vs 2022); Moderate CE (orange solid): Accelerated reduction, reaching 162 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−93.2%); Aggressive CE (green solid): Steep reduction, reaching 101 Mt CO₂ by 2050 (−95.7%); Uncertainty bands (shaded regions) around 2030 and 2050 projections show widening confidence intervals with increasing time horizon; Vertical dashed lines mark 2030 and 2050 policy target years.

Figure 10.

Scenario Comparison: 2030 and 2050 Projections with 95% Confidence Intervals (Monte Carlo, N=10,000). Note: Left panel (2030): Bar chart comparing three scenarios with error bars representing 95% CI, Linear Baseline: 1,036 Mt CO₂ (−56.2%), Moderate CE: 403 Mt CO₂ (−82.9%), Aggressive CE: 231 Mt CO₂ (−90.2%). Right panel (2050): Bar chart comparing 2050 outcomes - Linear Baseline: 502 Mt CO₂ (−78.8%), Moderate CE: 162 Mt CO₂ (−93.2%), Aggressive CE: 101 Mt CO₂ (−95.7%), Red dashed line indicates 2022 baseline (2,365 Mt CO₂). Error bars represent ±1.96 standard errors from the Monte-Carlo ensemble.

Figure 10.

Scenario Comparison: 2030 and 2050 Projections with 95% Confidence Intervals (Monte Carlo, N=10,000). Note: Left panel (2030): Bar chart comparing three scenarios with error bars representing 95% CI, Linear Baseline: 1,036 Mt CO₂ (−56.2%), Moderate CE: 403 Mt CO₂ (−82.9%), Aggressive CE: 231 Mt CO₂ (−90.2%). Right panel (2050): Bar chart comparing 2050 outcomes - Linear Baseline: 502 Mt CO₂ (−78.8%), Moderate CE: 162 Mt CO₂ (−93.2%), Aggressive CE: 101 Mt CO₂ (−95.7%), Red dashed line indicates 2022 baseline (2,365 Mt CO₂). Error bars represent ±1.96 standard errors from the Monte-Carlo ensemble.

Table 3.

Circular Economy Policy Scenarios and Projected Emissions Outcomes by 2030.

Table 3.

Circular Economy Policy Scenarios and Projected Emissions Outcomes by 2030.

| Scenario |

Material Intensity |

Recycling Rate Change |

Virgin-to-Recycled Mix (2030) |

Policy Levers |

Interpretation |

2030 Emissions Outcome |

| A. Linear Baseline (Current Policies) |

−0.5% per annum (historical average) |

+0.5% per annum (historical pace) |

~80% virgin |

— |

Continuation of existing policies without acceleration |

Baseline for comparison |

| B. Moderate Circular Economy |

−1.5% per annum (accelerated decoupling) |

+2.0% per annum |

70% virgin |

EPR enforcement, recycled content mandates |

Implementation of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan |

−8% vs. baseline |

| C. Aggressive Circular Economy (Net-Zero Compatible) |

−3.0% per annum (structural decoupling) |

+4.0% per annum |

50% virgin |

>50% recycled content mandates, industrial symbiosis, bioeconomy expansion |

Aligned with EU net-zero 2050 commitment |

−18% vs. baseline |

Table 4.

Monte Carlo Parameter Distributions.

Table 4.

Monte Carlo Parameter Distributions.

| Parameter |

Distribution |

Parameters |

Justification |

| Virgin carbon intensity (CIvirgin) |

Normal |

μ, σ = 0.12μ |

±12% LCA database variation |

| Recycled carbon intensity (CIrecycled) |

Normal |

μ, σ = 0.15μ |

±15% process variation |

| Recycling acceleration rate |

Uniform |

1%–5% p.a. |

Policy uncertainty range |

| Material demand elasticity |

Normal |

μ = 0.8, σ = 0.15 |

Econometric estimates |

Table 1.

Embodied Carbon Intensity (ECI) by Material Type.

Table 1.

Embodied Carbon Intensity (ECI) by Material Type.

| Material |

Virgin ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

Recycled ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

ECI Differential (%) |

Source |

| Steel |

1.95 |

0.65 |

−67% |

IVL (2019) |

| Aluminum |

12.5 |

0.75 |

−94% |

Material Economics (2021) |

| Paper & Cardboard |

1.2 |

0.5 |

−58% |

Eurostat LCA |

| Plastic |

3.8 |

1.5 |

−61% |

APME (2022) |

| Cement |

0.92 |

0.75 (alternative) |

−18% |

WBCSD |

| Glass |

0.8 |

0.3 |

−63% |

FEVE (2020) |

Table 2.

Panel regression results.

Table 2.

Panel regression results.

| Period |

Coverage |

Purpose |

Sample Size |

| Early CE Era |

2004–2015 |

Baseline recycling rates |

12 years |

| Late CE Era |

2015–2022 |

Acceleration phase |

8 years |

| Recent Dynamics |

2015–2023 |

CMR acceleration |

9 years |

Table 5.

Temporal availability of key variables.

Table 5.

Temporal availability of key variables.

| Variable |

Period |

Coverage |

Observations |

| Total Emissions |

1990–2022 |

94.3% |

33 years |

| Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) |

2015–2024 |

28.6% |

10 years |

| Recycling Rates |

2000–2024 |

71.4% |

25 years |

| Circular Material Rate (CMR) |

2014–2023 |

28.6% |

10 years |

| Waste Generation |

2004–2022 |

28.6% |

10 years |

Table 6.

Annual Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) and Year-on-Year Change in the EU27, 2015–2022.

Table 6.

Annual Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) and Year-on-Year Change in the EU27, 2015–2022.

| Year |

DMC (Mt) |

Year-on-Year Change |

| 2015 |

6,133 |

— |

| 2016 |

6,125 |

−0.1% |

| 2017 |

6,295 |

+2.8% |

| 2018 |

6,403 |

+1.7% |

| 2019 |

6,481 |

+1.2% |

| 2020 |

6,212 |

−4.1% (COVID-19) |

| 2021 |

6,477 |

+4.3% (recovery) |

| 2022 |

6,444 |

−0.5% |

Table 7.

Change in Domestic Material Consumption by Material Type in the EU27, 2015–2022.

Table 7.

Change in Domestic Material Consumption by Material Type in the EU27, 2015–2022.

| Material Type |

2015 (Mt) |

2022 (Mt) |

Change (%) |

| Biomass |

1,478 |

1,473 |

−0.3% |

| Metal Ores |

314 |

348 |

+10.8% |

| Non-metallic Minerals |

2,885 |

3,365 |

+16.6% |

| Fossil Energy |

1,458 |

1,225 |

−15.9% |

| Total |

6,133 |

6,444 |

+5.1% |

Table 8.

Average Recycling Rates by Period (2000–2023).

Table 8.

Average Recycling Rates by Period (2000–2023).

| Period |

Mean Recycling Rate (%) |

Status |

| 2000–2010 |

1.35 ± 0.08 |

Baseline establishment |

| 2010–2015 |

1.61 ± 0.06 |

Pre-CE Action Plan |

| 2015–2023 |

2.18 ± 0.41 |

CE acceleration phase |

Table 10.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables (2015–2022).

Table 10.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables (2015–2022).

| Variable |

Mean |

Std Dev |

Min |

Max |

N |

|

Emissions (Mt CO₂) |

2,575 |

176 |

2,369 |

2,849 |

8 |

|

DMC (Mt) |

6,321 |

146 |

6,125 |

6,481 |

8 |

| Recycling Rate (%) |

2.18 |

0.31 |

1.82 |

2.84 |

8 |

| CMR (%) |

11.3 |

0.25 |

11.1 |

11.8 |

8 |

|

Waste Generation (Mt) |

3,036 |

804 |

1,763 |

3,893 |

7 |

Table 11.

Correlation Matrix (2015–2022).

Table 11.

Correlation Matrix (2015–2022).

| |

Total Emissions |

DMC |

Recycling Rate |

CMR |

| Total Emissions |

1.000 |

−0.241 |

−0.667 |

0.438 |

| DMC |

|

1.000 |

0.663 |

0.036 |

| Recycling Rate |

|

|

1.000 |

0.080 |

| CMR |

|

|

|

1.000 |

Table 12.

Embodied Carbon Intensity by Material Type (LCA Data).

Table 12.

Embodied Carbon Intensity by Material Type (LCA Data).

| Material |

Virgin ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

Recycled ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

ECI Differential (%) |

Decarbonization Leverage |

| Aluminum |

12.50 |

0.75 |

−94% |

Very High |

| Steel |

1.95 |

0.65 |

−67% |

High |

| Plastic |

3.80 |

1.50 |

−61% |

High |

| Glass |

0.80 |

0.30 |

−63% |

High |

| Paper & Cardboard |

1.20 |

0.50 |

−58% |

High |

| Cement |

0.92 |

0.75 |

−18% |

Low |

Table 13.

Material categories according to Eurostat's Domestic Material Consumption (DMC).

Table 13.

Material categories according to Eurostat's Domestic Material Consumption (DMC).

| Eurostat Category |

Mapped LCA Materials |

Average Virgin ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

Average Recycled ECI (kg CO₂/kg) |

ECI Differential (%) |

| Biomass |

Paper & Cardboard |

1.20 |

0.50 |

−58% |

| Metal ores (gross) |

Steel, Aluminum |

7.22 |

0.70 |

−90% |

| Non-metallic minerals |

Cement, Glass |

0.86 |

0.53 |

−39% |

| Fossil energy |

Plastic |

3.80 |

1.50 |

−61% |

Table 14.

Annual Virgin and Recycled Material Emissions (2015–2022).

Table 14.

Annual Virgin and Recycled Material Emissions (2015–2022).

| Year |

Recycling Rate (%) |

Virgin Emissions (Mt CO₂) |

Recycled Emissions (kt CO₂) |

Total MCA Emissions (Mt CO₂) |

Virgin Share (%) |

| 2015 |

2.01 |

11.82 |

93.5 |

11.91 |

98.0 |

| 2016 |

2.06 |

11.72 |

95.0 |

11.81 |

97.9 |

| 2017 |

2.09 |

11.90 |

98.2 |

12.00 |

97.9 |

| 2018 |

2.13 |

12.08 |

100.9 |

12.18 |

97.9 |

| 2019 |

2.18 |

11.74 |

101.8 |

11.85 |

97.8 |

| 2020 |

2.19 |

10.88 |

95.0 |

10.97 |

97.8 |

| 2021 |

2.28 |

11.41 |

103.8 |

11.51 |

97.7 |

| 2022 |

2.50 |

11.54 |

114.8 |

11.65 |

97.5 |

Table 15.

Annual LMDI Decomposition Results (2015–2022).

Table 15.

Annual LMDI Decomposition Results (2015–2022).

| Period |

Emissions Change (%) |

Activity Effect (%) |

Structure Effect (%) |

Intensity Effect (%) |

| 2015–2016 |

−0.88 |

+166.9 |

−1,076.8 |

+1,009.9 |

| 2016–2017 |

+1.61 |

+2,025.5 |

−1,080.9 |

−844.6 |

| 2017–2018 |

+1.49 |

+1,383.6 |

−1,099.2 |

−184.4 |

| 2018–2019 |

−2.79 |

−507.0 |

−1,091.2 |

+1,698.2 |

| 2019–2020 |

−7.39 |

+623.7 |

−1,030.5 |

+506.7 |

| 2020–2021 |

+4.89 |

+976.0 |

−1,014.0 |

+138.0 |

| 2021–2022 |

+1.12 |

−531.2 |

−1,047.2 |

+1,678.4 |

Table 16.

Panel Regression Results: Elasticity Estimates.

Table 16.

Panel Regression Results: Elasticity Estimates.

| Parameter |

Late CE Era (2015–2022) |

Recent Dynamics (2015–2023) |

| N observations |

8 years |

8 years |

| Intercept |

−6.087

(SE: 7.869, p=0.482) |

−6.087

(SE: 7.869, p=0.482) |

| DMC Elasticity (β₁) |

+1.148

(SE: 0.875, p=0.260) |

+1.148

(SE: 0.875, p=0.260) |

| Recycling Elasticity (β₂) |

−0.920*

(SE: 0.302, p=0.038) |

−0.920*

(SE: 0.302, p=0.038) |

| CMR Elasticity (β₃) |

+1.908

(SE: 0.944, p=0.113) |

+1.908

(SE: 0.944, p=0.113) |

| R-squared |

0.773 |

0.773 |

| Adj. R-squared |

0.603 |

0.603 |

| Std. Error |

0.041 |

0.041 |

Table 17.

2030 Emissions Projections by Scenario (95% Confidence Intervals, N=10,000).

Table 17.

2030 Emissions Projections by Scenario (95% Confidence Intervals, N=10,000).

| Scenario |

Mean (Mt CO₂) |

Median (Mt CO₂) |

Std Dev |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

% Change vs 2022 |

| Linear Baseline |

1,036 |

1,033 |

119.4 |

814 |

1,284 |

−56.2% |

| Moderate CE |

403 |

395 |

89.6 |

253 |

600 |

−82.9% |

| Aggressive CE |

231 |

223 |

66.7 |

127 |

389 |

−90.2% |

Table 18.

2050 Emissions Projections by Scenario (95% Confidence Intervals, N=10,000).

Table 18.

2050 Emissions Projections by Scenario (95% Confidence Intervals, N=10,000).

| Scenario |

Mean

(Mt CO₂) |

Median

(Mt CO₂) |

Std Dev |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

% Change vs 2022 |

| Linear Baseline |

502 |

— |

121.7 |

323 |

736 |

−78.8% |

| Moderate CE |

162 |

— |

70.8 |

79 |

289 |

−93.2% |

| Aggressive CE |

101 |

— |

55.1 |

46 |

195 |

−95.7% |

Table 19.

Monte Carlo Parameter Distributions and Rationale.

Table 19.

Monte Carlo Parameter Distributions and Rationale.

| Parameter |

Distribution |

Range/Parameters |

Justification |

| Virgin ECI |

Normal |

μ, σ=0.12μ |

±12% LCA database variation |

| Recycled ECI |

Normal |

μ, σ=0.15μ |

±15% process variation |

| Recycling Acceleration |

Uniform |

[80%, 120%] of scenario value |

Policy implementation uncertainty |

| DMC Elasticity |

Normal |

μ=1.148, σ=0.15 |

Econometric estimation uncertainty |