2. Results

Traditional water quality monitoring methods, which include manual sample collection and laboratory analysis, have their advantages and disadvantages, summarized in

Table 1, but they are often labor-intensive, expensive, and cannot provide sufficient spatial and temporal coverage for effective pollution detection and tracking.

The latest intelligent information technologies, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), play an important role in modern environmental monitoring, ensuring more accurate and effective data analysis. Here are some existing solutions. The digital platform "World Environment Situation Room (WESR)" collects and analyzes data from various sources, including satellites and sensors, to monitor the state of the environment. The platform was launched by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and uses AI for global environmental analysis. The GEMS air pollution monitoring platform uses AI to track air pollution levels in real-time, analyzing data from sensors located at various points in the city and providing air quality forecasts. AI is used for monitoring emissions of one of the most powerful greenhouse gases – methane. AI algorithms analyze data from satellites and ground sensors to detect emission sources and assess their impact on the climate. AI helps assess the impact of various activities on the environment and climate. This includes analyzing data on greenhouse gas emissions, resource use, and other environmental indicators.

AI to analyze data from sensors that measure various water parameters, such as pollution levels, temperature, and pH. This allows for the detection of anomalies and the prediction of possible threats. AI is used for monitoring wild animal populations and their habitats. Algorithms analyze data from surveillance cameras, drones, and other sources to detect changes in animal behavior and the state of their habitats. The presented environmental technologies demonstrate how AI can significantly improve the effectiveness and accuracy of environmental monitoring, helping to preserve the environment and ensure sustainable development (Melenchuk & Protsyshyn, 2023).

Biological, hydromorphological, and physicochemical parameters help ensure a comprehensive approach to river water quality monitoring, which is critically important for preserving ecosystems and ensuring public health.

Various sensors and equipment are used for water quality monitoring, ensuring accurate measurements of different water parameters. Dissolved Oxygen (DO) sensors have high accuracy, which is a critical parameter for aquatic ecosystems, and are calibrated once every 3–6 months. pH sensors have high accuracy in assessing water acidity/alkalinity but are calibrated monthly or before each use. Temperature sensors are important for chemical reactions and biological processes. They generally do not require calibration, but accuracy verification is recommended once a year. Turbidity sensors are important for assessing water transparency and sediment level and are usually calibrated every 6 months. Conductivity sensors are used to indicate the concentration of ions in the water, and calibration is recommended every 3–6 months. Data about them are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The use of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies opens up new possibilities for real-time water quality monitoring (Hamid et al., 2020; Kamaludin & Ismail, 2017). Modern water quality IoT systems measure parameters such as pH, temperature, water level, turbidity, ORP, DO, EC, chlorophyll, blue-green phytoplankton, conductivity, depth, salinity, chlorine, and others. They use almost all available data transmission technologies: LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, 4G, LTE, GSM, GPRS, Bluetooth, USB, SDI-12, Modbus, Wi-Fi, MQTT, REST API, SD-card, and others.

Sensors collect data on water parameters and transmit them to a central system on servers and cloud platforms for processing. The characteristics of modern IoT water quality sensors are summarized in

Table 4.

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms in water resource monitoring opens up new possibilities for increasing the accuracy, responsiveness, and effectiveness of environmental analysis. These algorithms ensure automated processing of large data sets coming from sensor systems, aiming to detect anomalous changes, predict potential pollution threats, and formulate scientifically sound recommendations for water ecosystem management. Integration with digital platforms and mobile applications allows for the visualization of results in the form of graphs, cartographic layers, and analytical reports, as well as rapidly informing users about critical deviations from normative indicators.

Different types of AI algorithms have a specific purpose depending on the nature of the data and the research goals. Specifically, linear regression is used to build models of dependence between the physicochemical parameters of water and its quality indices. Decision trees are effective for detecting patterns and anomalies in structured data. Support Vector Machine (SVM) methods are applied for classifying types of pollution, while clustering (K-Means) allows for the identification of spatial zones with increased levels of anthropogenic load. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) ensure the analysis of satellite images and images of water objects, and Recurrent Networks (LSTM) predict the dynamics of water quality changes based on time series. Transformer architectures allow for the detection of complex interdependencies in multi-dimensional data, and Autoencoders identify atypical combinations of parameters that may indicate hidden sources of pollution.

The application of these tools allows environmentalists not only to respond quickly to changes in the aquatic environment but also to form long-term strategies for water resource management based on data. Summarized data on AI algorithms used for water quality data analysis are presented in

Table 5.

The indicated algorithms help ensure accurate and effective analysis of water quality data, which is critically important for preserving ecosystems and ensuring public health.

Examples of successful implementation of such projects include the "Smart Water" Project (USA) and the "AquaWatch" Project (European Union). The "Smart Water" Project (n.d.) uses IoT for water quality monitoring in urban water supply systems. Sensors collect water quality data, which are analyzed in real-time to detect pollution. The "AquaWatch" Project is based on the use of satellite data and IoT for monitoring water quality in rivers and lakes. In both projects, integration with IoT allows for continuous real-time water quality monitoring, which is critically important for preserving ecosystems and ensuring public health. An example of successful use of AI for water quality monitoring in Ukraine is the "Clean Water" project, in which data on water quality in rivers and lakes of Ukraine are collected using IoT sensors and analyzed using machine learning and AI algorithms.

The reviewed Artificial Intelligence methods demonstrate a wide range of possibilities for increasing the effectiveness of water quality monitoring, particularly through the automated analysis of large volumes of data. One of the key directions of their practical application is the detection of anomalies in water environment indicators, which may indicate sudden pollution or technogenic impacts.

In this context, machine learning algorithms play a special role, allowing the identification of atypical deviations in data, even in the absence of clearly defined threshold values. Let's consider the main approaches to anomaly detection in water quality data using ML. Examples of the most effective ML algorithms used for anomaly detection in water quality data are provided in

Table 6.

Continuous water quality monitoring using AI and IoT allows for the real-time detection of hazardous substance discharges into rivers and water bodies. The detection of discharges is based on the assumption that anomalies significantly deviate from the normal behavior of the data. In the context of monitoring and anomaly detection that may indicate environmental threats or changes, a number of machine learning algorithms exist.

The "Isolation Forest" algorithm (Cheng et al., 2019) effectively detects anomalous observations that are "isolated" faster than normal data through random feature partitioning. In environmental monitoring, this can be applied to detect atypical changes in ecological time series (e.g., sharp jumps in air or water pollution, uncharacteristic behavior of species populations).

The "One-Class SVM" algorithm (Kerimov et al., 2025) is used to identify deviations from the "normal" profile of environmental data when data primarily describing the normal state of the ecosystem are available. It builds a boundary around these normal data, and any new observations outside this boundary are considered anomalous (e.g., detecting unusual chemical compounds in soil samples that are not characteristic of the given area).

The "Local Outlier Factor" (LOF) algorithm determines the degree of abnormality of each data point by comparing its local density with the density of its neighbors. In the environmental protection sphere, LOF can help detect localized anomalies, such as points with unusually low biodiversity compared to surrounding areas or sudden local changes in water temperature (Cheng et al., 2019).

"Autoencoders" algorithms are based on neural networks trained to reconstruct input data (Akhmetshyna & Nesterenko, 2024). Anomalies can be detected as observations for which the reconstruction error is significantly higher, as the model was not trained on such atypical data. Autoencoders can be used to detect unusual combinations of environmental parameters in large datasets from remote sensing or water quality monitoring networks.

"Random Forest" is a method that combines a large number of independent decision trees, each trained on a random subset of data and features. The resulting prediction is formed as the average of the predictions of all trees. The method ensures high accuracy, resistance to overfitting, and allows for assessing feature importance.

"XGBoost" (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is a boosting model that sequentially trains weak models (decision trees), each correcting the errors of the previous ones. The algorithm optimizes the loss function with regularization, allowing for high accuracy while maintaining generalizability. XGBoost supports handling missing values, automatic feature selection, and parallel training.

The application of these methods allows for more effective detection of potential environmental problems at early stages, tracking changes in ecosystems, and making informed decisions regarding environmental protection measures.

A comparison of AI and ML methods for anomaly detection is presented in

Table 7.

To select the monitoring method for water in reservoirs, factors such as data structure (structured, unstructured), data size, resource size (limited, unlimited), and the nature of anomalies must be considered. The method selection is summarized in

Table 8.

Various types of models are used to assess and predict the pathways of hazardous substance spread in water bodies.

Mathematical models (including Gaussian and turbulent diffusion models) are applied to describe the processes of pollutant dispersion in the aquatic environment. They are based on the normal distribution of concentrations and consider the influence of turbulent flows and diffusion. Such models are effective for estimating pollution levels at different distances from the source, especially in complex hydrological conditions.

Hydrodynamic models, based on the equations of fluid motion (Navier–Stokes equations, transport equations), allow for modeling the behavior of water flows and the spread of pollution in water bodies. They take into account real hydrodynamic conditions, which makes them indispensable for environmental monitoring and planning clean-up measures.

Machine learning methods use historical data to detect patterns in pollution spread, allowing for building forecasts based on the analysis of large volumes of ecological information, which is particularly useful when the amount of field measurements is limited.

A comparative characteristic of these approaches is given in

Table 9, which allows for selecting the optimal modeling method depending on the research conditions and available data.

These methods help ensure accurate and effective prediction of hazardous substance spread pathways in water bodies, which is critically important for preserving ecosystems and ensuring public health.

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) methods in water quality monitoring systems is accompanied by a number of technical and practical challenges. The effectiveness of AI models largely depends on the quality of the input data coming from sensor devices. Incomplete or inaccurate data can lead to false predictions and incorrect management decisions (Shestopalov et al., 2024).

The process of training and functioning of AI models requires significant computational resources, which may be inaccessible to small organizations. The integration of intelligent systems into the already existing monitoring infrastructure is often complex and requires additional financial and technical costs (Tekhnična inzhenerija, 2024). The high cost of implementing and maintaining such systems can become a barrier to their widespread adoption, especially under conditions of limited funding. It is also important to consider that the effective use of AI requires highly qualified personnel, which is not always available in environmental institutions with limited human resources.

Besides technical aspects, the application of AI in water resource monitoring must comply with current regulatory requirements and standards, which may complicate its implementation. These limitations are important aspects to consider when implementing AI for water quality monitoring.

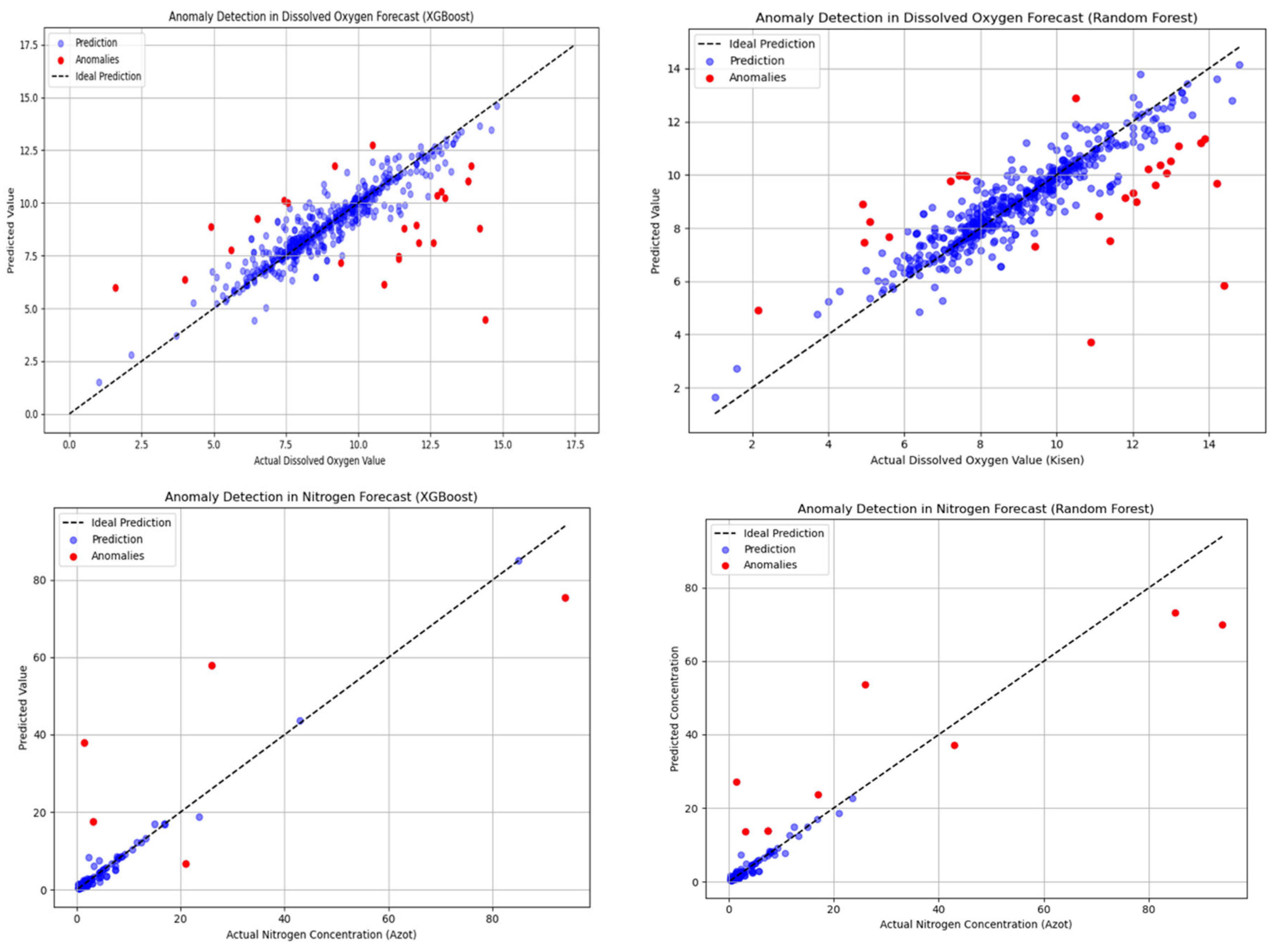

The authors conducted a study to assess the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms for predicting key water quality indicators, particularly nitrogen concentration and dissolved oxygen, based on multi-dimensional chemical, spatial, and seasonal features. Anomaly detection was additionally performed, which may indicate hazardous substance discharges or sensor errors.

Open environmental water quality data collected between February 2022 and January 2023 were analyzed, containing information on the quality status of Ukraine's surface waters for 2022. The dataset contains primary information (observation data) from the state monitoring of surface waters. Data are presented by monitoring sites and sampling dates. The set includes 16 key monitoring indicators: total nitrogen, biochemical oxygen demand for 5 days, suspended solids, dissolved oxygen, sulfate ions, chloride ions, ammonium ions, nitrate ions, nitrite ions, phosphate ions (polyphosphates), chemical oxygen demand, phytoplankton, and others. Each table in the dataset contains observation data for a specific period. Monitoring programs and other reference information can be found on the State Water Agency website (Derzhavne ahentsvo vodnykh resursiv Ukrayiny, n.d.) and the Portal for monitoring and environmental assessment of Ukraine's water resources (Portal monitorynhu ta ekologhichnoji otsinky vodnykh resursiv Ukrajiny, n.d.).

Data from monthly files were merged, cleaned of missing values, and converted to a numerical format. Relevant chemical, spatial, and seasonal features (biochemical oxygen demand for 5 days, phosphate concentration, and nitrate concentration, geographical coordinates of monitoring sites, and seasonal features) were selected for nitrogen and oxygen. A hybrid ensemble approach (RF/XGBoost + residual analysis) was chosen for predicting key indicators (nitrogen, oxygen). This choice is pragmatic and optimal because, in addition to high accuracy and resistance to overfitting, these models are less demanding on computational resources compared to deep learning methods (e.g., autoencoders), which was appropriate for the study's capabilities. Residual analysis was applied for anomaly detection, where the deviation threshold from the model's prediction indicated unforeseen events, such as local pollution or measurement errors. Both methods were tested on identical datasets. The standard 80/20 train/test split method was used for initial model evaluation, and more robust methods, such as k-fold cross-validation, are proposed for future research. Residual analysis for anomaly detection, model comparison, and result generalization were also performed. The coefficient of determination (R2), which shows the proportion of the variation in the target variable the model could explain based on features, and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were calculated for each model.

All key stages of the study were verified and summarized in

Table 10.

Residual analysis allowed for the identification of anomalous points that significantly deviate from the model's predictions (

Figure 1). These deviations indicate the presence of observations that do not correspond to the general pattern and may be indicators of unforeseen events, such as local pollution or measurement errors.

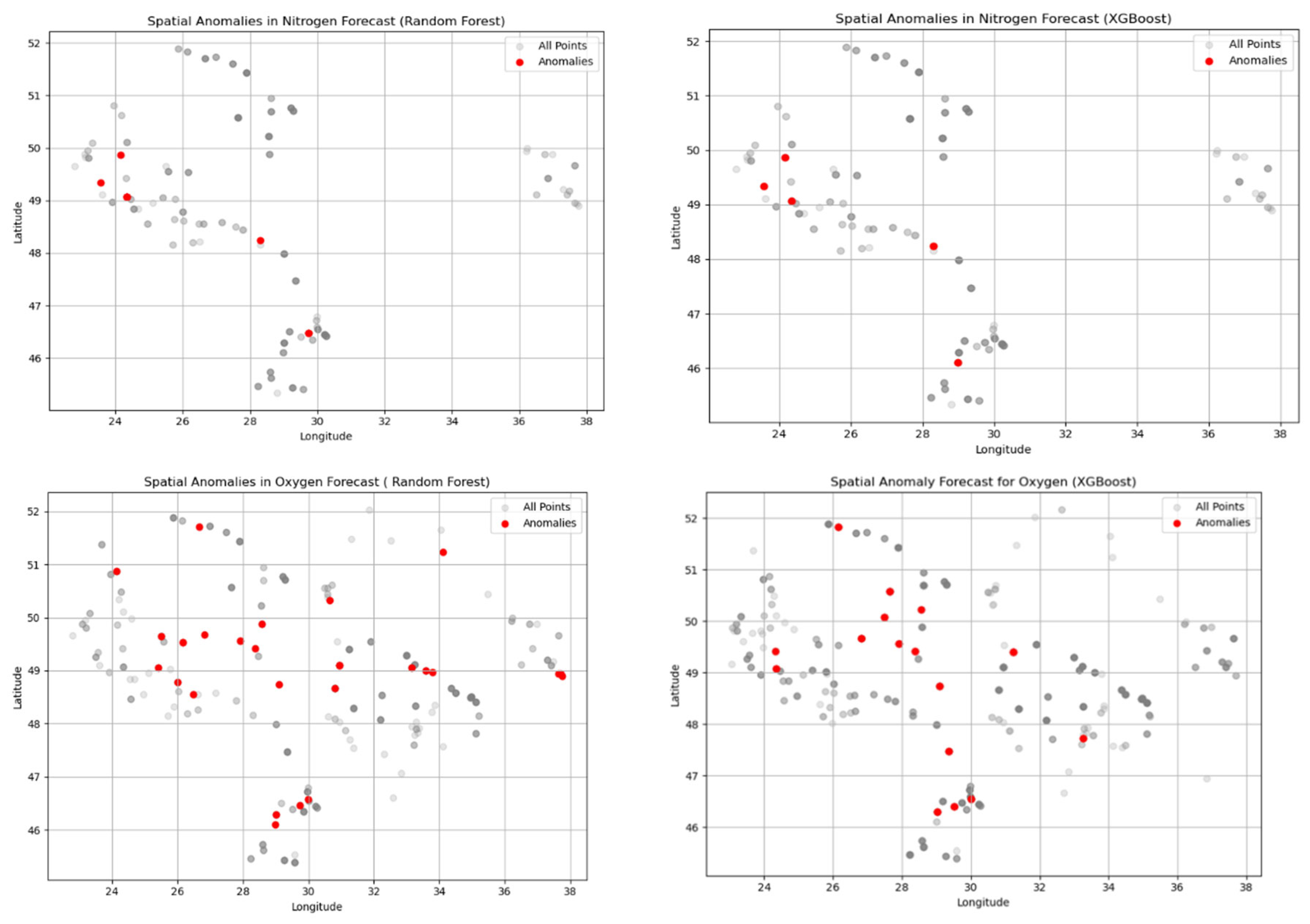

Anomalous points that do not correspond to the general pattern were detected. Based on Latitude and Longitude coordinates, maps (

Figure 2) were constructed to demonstrate the spatial location of these anomalous points. The visualization confirmed that anomalies are not concentrated in one region (from Lviv region to Odesa region), which indicates the systemic nature of the phenomenon or distributed pollution sources (municipal sewage, agricultural impact) across the entire monitoring area.

Verification of the origin of the anomalous points by monitoring siteі was carried out. It was found that six monitoring sites are sources of most anomalies, which may indicate local pollution problems, technical measurement errors, or non-uniformity in data collection methods. The integration of residual analysis into the modeling process allowed for increased prediction accuracy and the detection of potentially critical points that require additional monitoring. This approach demonstrates how AI algorithms can be used for the early detection of environmental threats. Prediction results and model evaluation are presented in

Table 11.

Residual analysis was performed for each indicator to detect anomalous points that do not align with the models' predictions. For oxygen, both models have similar accuracy, but RF detected slightly more anomalies (28 versus 6). The threshold is lower for oxygen, indicating less residual variability. Nitrogen anomalies are concentrated around technogenic sources, while oxygen anomalies are more widely distributed, often associated with drinking water intakes. Some monitoring sites (

Table 12) have anomalies that recur across different models, regardless of the method or target variable.

Residual analysis allowed for the identification of anomalous points that significantly deviate from the model's predictions. These deviations indicate the presence of observations that do not correspond to the general pattern and may be indicators of unforeseen events, such as local pollution or measurement errors. Anomalous points that do not align with the general pattern were detected.

Six monitoring sites are the sources of most recurring anomalies across different models, which indicates systemic instability or the manifestation of local pollution. Specifically, anomalies at the R. Poltva monitoring site (Kam'yanopil'), which consistently deviated from predicted values, have a high probability of technogenic origin. This monitoring site is located downstream from Lviv and its sewage treatment plants. Deviations detected by the Random Forest and XGBoost models may be a direct indicator of irregular or peak discharges from the municipal infrastructure that do not fit into usual seasonal and annual patterns. A similar situation is observed at other monitoring sites, which is confirmed by geographical analysis.

Anomalies were detected in two or more models at six monitoring sites. The Kropyvnyk River is the most persistent point of concern, with four anomalies identified by the RF model (nitrogen) and confirmed by the XGB model (nitrogen). The Hadzhyder River presents a unique case where anomalies were found for both indicators (nitrogen and oxygen) in the RF model. The Kyrhyzh-Kytay River shows a cross-model anomaly, appearing in the XGB model (nitrogen) and the RF model (oxygen).

These points may indicate systemic water quality problems, anthropogenic impacts, or sensor measurement instability. Their detection, independent of the model used, confirms the consistency of the algorithms and the reliability of the anomaly detection approach.

The detected anomalies exhibit a clear seasonal and spatial structure, indicating the models' sensitivity to natural and anthropogenic factors. Anomalies that recur across different models point to systemic water quality problems, regardless of the algorithm chosen.

Thus, the applied anomaly detection method (residual analysis) successfully identifies local pollution sources associated with high anthropogenic pressure. Combining ensemble methods (RF, XGB) with residual analysis proves to be an effective strategy for uncovering hidden patterns in environmental data. This approach can be scaled to other types of monitoring, including air, soil, or biological indicators. ML models have demonstrated their ability to detect complex non-linear dependencies, offering high accuracy and ease of interpretation without manual formula tuning. This research demonstrates that AI can support environmental monitoring, and these models can be integrated into early warning system.

3. Conclusions

The conducted research confirmed that combining ensemble algorithms (Random Forest and XGBoost) with residual analysis is an effective tool for identifying systemic and hidden anomalies in water quality data. The geographic verification of anomalous points clearly correlates their occurrence with major sources of anthropogenic impact. Specifically, two main types of impact were identified: technogenic and agricultural. The technogenic impact, recorded on the Poltva and Kropyvnyk rivers, is linked to municipal and industrial discharges from large cities. The agricultural impact, detected on the Hadzhyder and Kyrhyzh-Kytay rivers, manifests through cross-model anomalies of nitrogen and oxygen, which serve as a direct indicator of systemic eutrophication caused by fertilizer runoff. This approach allows for the transformation of machine learning results into operational data for environmental management and early warning of local pollution events.

A comparison between artificial intelligence and traditional methods in the field of water quality monitoring reveals significant differences across several key criteria.

From the perspective of accuracy and speed, AI provides high analytical precision and is capable of processing data in real time, which is critically important for preserving ecosystems and ensuring public health. Traditional methods can also be accurate, but they require significantly more time to perform the analysis.

Regarding responsiveness, AI-based systems enable continuous monitoring and rapid reaction to changes in the aquatic environment. In contrast, traditional approaches are limited in this aspect as they rely on manual data collection, which slows down the response process.

In the context of cost and accessibility, AI helps reduce expenses associated with manual data collection and is easily scalable. At the same time, traditional methods have the advantage of relatively low-cost field tests, especially in the initial stages.

However, both approaches have their drawbacks. AI is characterized by a high dependency on the quality of input data, as well as significant costs for system implementation and maintenance. Traditional methods, in turn, require expensive laboratory analyses and a long time to process the results.

In summary, we can affirm that AI ensures high accuracy in data analysis through the use of machine learning and deep learning algorithms. This allows for the detection of complex anomalies that might be missed by traditional methods.

Continuous, real-time monitoring of water quality enables the rapid detection of pollution and the implementation of necessary remediation measures. Integration with Internet of Things (IoT) systems provides for the automation of data collection and analysis processes, which increases the efficiency of water resource management. AI algorithms can predict the spread of pollutants in water bodies, which allows for timely measures to be taken to prevent environmental disasters. Machine learning models help assess the impact of various factors on water quality and develop strategies to reduce pollution. The speed of data processing increases significantly, which enables real-time results and rapid responses to changes in water quality. Overall, AI, ML, and IoT help to optimize water resource management, reducing the costs associated with their monitoring and purification.

Prospects for further research in the field of AI-powered water quality monitoring encompass several key areas aimed at enhancing the accuracy, efficiency, and scalability of these technologies. Among them are the development of new, more sensitive sensors, the integration of systems with the Internet of Things (IoT) for real-time data collection, and the use of satellite data for large-scale monitoring. An important direction is the improvement of artificial intelligence algorithms, particularly machine learning and deep learning, for more precise analysis and prediction of pollution.

Furthermore, significant attention should be given to modernizing laboratory equipment to improve the quality of analytical research. All these areas contribute to the creation of more reliable, adaptive, and accessible monitoring systems, which are critically important for the protection of water resources, environmental safety, and public health.