1. Introduction

At present, the interest of scientists in the treatment of wastewater from pharmaceuticals (PPs) is growing, as sustainable development requires a balance between economic growth, environmental protection, and human health, and the pollution of water bodies with PP threatens all three. Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) have recently been identified as pollutants of increasing concern that are potentially hazardous to the environment and human health, but most are currently not subject to environmental regulation [

1]. The stability and biological activity of these highly water-soluble contaminants, which occur in micromolar concentrations, can lead to the development of resistance and other health-related effects. Research on pharmaceuticals has primarily focused on their prevalence and impacts in surface waters. For example, six pharmaceuticals (clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole, venlafaxine, gemfibrozil, and diclofenac) selected due to their high global consumption, low removal efficiency in aeration tanks, and persistence in aquatic environments are discussed in detail [

1]. The occurrence of pharmaceuticals in an urban alluvial aquifer was investigated and their risk to human health was assessed. The results showed that 35 pharmaceuticals, including 6 transformation products, were detected in all groundwater samples, and the concentrations ranged from low to μg/L [

2]. A study [

3] investigated the occurrence, distribution, and potential sources of 34 pharmaceuticals and personal care products in water, sediment, aquatic organisms (fish and shellfish), and fish feed from mariculture areas of the Pearl River Delta. Spectinomycin, paracetamol, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ibuprofen were the most frequently detected in feed. Ibuprofen and ketoprofen were widely detected in aquatic organisms, with average concentrations of 562 and 267 ng/g wet weight, respectively.

Although the concentration of pharmaceuticals decreases over time due to partial destruction, filtration through aquifers, adsorption, and oxidation-reduction reactions, it is necessary to develop effective wastewater treatment methods.

Standard treatment facilities do not completely remove pharmaceuticals because they are stable and soluble, so additional methods are necessary. The development of industrial wastewater treatment technologies is of great importance. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), including ozonation, UV radiation, electrolysis, and photocatalysis, play a key role [

4]. AOPs generate various reactive species, including non-selective OH radicals, which promote the degradation of a wide range of organic compounds. The Fenton reaction is characterized by high mineralization efficiency, is inexpensive, simple, and environmentally friendly [

5]. The classic version of the Fenton process requires the use of acidic solutions, which necessitates additional treatment. In addition, homogeneous catalysis leads to secondary contamination with iron(II) and iron(III) cations, which is unacceptable.

The use of the heterogeneous photo-Fenton process, which utilizes metal hydroxides, oxides, and oxyhydroxides as catalysts, significantly expands the potential for water treatment. Unlike homogeneous catalysis, heterogeneous catalysis is effective over a wide pH range and reaches its maximum efficiency when used [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Currently, numerous studies are devoted to the development of new ferrite photocatalysts with high stability and activity for the degradation of pharmaceuticals [

10,

11,

12].

Ferrite-based composites typically exhibit excellent performance due to their multifunctionality and magnetic separation capabilities. These materials provide high adsorption efficiency and fast kinetics for the removal of pollutants such as metal ions, dyes, and pharmaceuticals [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Nanocomposites of spinel ferrites with carbon materials have been shown to exhibit strong photocatalytic activity in the degradation of pollutants [

18,

19]. For example, nickel ferrite-based composites have been studied for water purification from organic pollutants [

20]. They are effective in removing a wide range of pollutants present in water, such as dyes such as methylene blue, rhodamine B, methyl orange, Congo red, and antibiotics (tetracycline, oxytetracycline, ampicillin, and sulfamethoxazole).

The work [

21] describes the synthesis of nickel ferrite (NiFe) nanoparticles, nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon nanoflakes (NCF), and a novel nickel ferrite–carbon nanoflake nanocomposite (NiFe@NCF) using a solvothermal method. The synthesized nanoparticles were used as a heterogeneous photocatalyst for the degradation of water pollutants: ciprofloxacin (CIP) and levofloxacin (LEV). 99.91% of LEV and 98.86% of CIP were degraded within 50 and 70 min under visible light irradiation using NiFe@NCF according to pseudo-first-order kinetics. The increased efficiency of the nanocomposite is due to the larger surface area, a decrease in the band gap (from 2.42 to 2.19 eV), a large number of active centers, and the mobility of charge carriers.

The use of TiO

2-CoFe

2O

4 and TiO

2-CuFe

2O

4 composite films exhibited excellent performance in the photocatalytic degradation of indigo carmine as a model dye at pH 3 under the action of UV and visible radiation [

22].

An extremely efficient and highly adaptive photocatalyst, La-CuFe

2O

4/g-C

3N

4 (LCFO/CN), was obtained using the hydrothermal method [

23]

The efficiency of the photocatalyst (lanthanum-doped copper ferrite/graphitic carbon nitride composites) was tested using the dye rhodamine B (RhB). The composite’s degradation rate was 97.35%, due to an increased surface area, an increased number of active sites, and a decreased band gap compared to the components [

24].

Ternary hybrid composites of Ni

0.5Zn

0.5Fe

2O

4/CeO

2 and Ni

0.5Zn

0.5Fe

2O

4/CeO

2/multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) nanocomposites exhibit excellent photocatalytic degradation efficiency (93.5%) for the removal of rose bengal (RB) dye from wastewater under UV radiation [

25].

A detailed analysis of ferrites and their nanocomposites revealed the influence of various parameters, such as substrate concentration, solution pH, photocatalyst amount, photocatalyst surface area, metal and non-metal ion doping, light intensity, and irradiation time, on the photocatalytic degradation of organic wastewater [

26,

27].

Despite a large number of review articles, little research has been devoted to the degradation of pharmaceuticals. Therefore, the synthesis of new composite photocatalysts and the study of their photocatalytic properties for the degradation of the aforementioned pollutants are of paramount importance.

The aim of this study is to obtain a Fe/CoFe2O4 composite by coprecipitation and hydrothermal treatment, as well as to investigate its physicochemical properties and photocatalytic activity in pharmaceutical degradation reactions.

2. Materials and Methods

The composite was obtained by precipitation of heteropolyhydroxo complexes from solutions FeSO4 and CoSO4 with a molar ratio of iron and cobalt cations of 2:1. The resulting sol was processed in a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor.

The phase composition of the samples was studied using a DRON-2.0 diffractometer. A JSM-6390LV scanning electron microscope was used to study the morphology of the samples.

The magnetic properties of the samples were determined from the magnetic hysteresis loop obtained by vibration magnetometry. To study the absorption of electromagnetic waves, samples were prepared in the form of films. The composite material was uniformly mixed in polyvinyl alcohol with a loading of 20% by weight. Fourier transform infrared spectra were obtained in the wavenumber range 400–4000 cm−1 using a Spectrum One spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer) in KBr tablets at 25 °C.

Photocatalytic properties were obtained using a model methylene blue, furatsilin, tetracycline, streptocide, ibuprofen.

To assess the influence of selected factors, the method of central composite experimental design was used. The influence of such parameters as photocatalyst concentration (X1), volume of H2O2 (X2), and UV irradiation time (X3) on the degradation of methylene blue, furatsilin, tetracycline, streptocide, and ibuprofen was determined. The core of the central composite design was a full factorial experiment (FFE) of the n=3 type.

The FFE plan was supplemented with a certain number of star points, the coordinates of which depend on the adopted optimality principle. The total number of experiments with this planning is determined by the formula

Where the terms are the number of FFE experiments, star points, and zero points, respectively.

The natural and coded values of the levels for each factor are given in

Table 1.

A second-order regression model was used to describe the experimental data:

where β0, βi, βij are coefficients for variables, ε is a value that takes into account the influence of random factors.

The analysis of the results of the response function calculation was carried out using analysis of variance of the results.

The degree of decomposition of the pollutant was used as the response function.

where C0 is the initial concentration of the PP in the solution, Ct is the concentration at time t.

Identification and determination of the pollutant concentration were performed by spectrophotometric analysis using a UV 5800 PC spectrophotometer.

Model calculation and subsequent optimization were performed using STATSGRAPHICS 10.0. The resulting models were tested for adequacy using the Fisher exact test, analysis of variance, and Pareto diagram analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composite Characterization

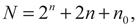

Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the sample synthesized in a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor. Very intense peaks of cobalt ferrite with a spinel structure are observed, along the (311) plane, the peak intensity is 2000 abs units, and there are also small peaks corresponding to α-Fe.

The X-ray diffraction data are in excellent agreement with the standard values for CoFe

2O

4 (JCPDS 22-1086). An anomalous increase in the crystallinity of cobalt ferrite powders obtained by hydrophase methods is observed, which is comparable with the samples obtained by sintering [

25]. The crystallite size determined by different methods was L

311 = 937 Å, L

440 = 1041 Å and L = 1046 Å. It should be noted that the crystallite sizes are an order larger than those obtained, for example, by the plasma method [

29]. The crystal lattice parameter is a = 8.3901 Å and corresponds to the lattice parameter of cobalt ferrite. SEM images of the sample are shown in

Figure 1c. It can be noted that the average particle size is 90-100 nm without pronounced agglomeration, which coincides with the calculated value of the crystallite size (

Table 1) obtained from X-ray diffraction data. It is important to note that particle aggregation is one of the most important technological problems solved by liquid-phase technologies.

The IR Fourier spectra of the sample nanoparticles in the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm

−1 are shown in

Figure 1b. Absorption is observed at wavenumbers of 3447, 1651, 1124. The wavenumber of 584 cm

−1 is characteristic and is related to vibrations of cations in tetrahedral positions in CoFe

2O

4 [

30]. A small peak at 1651 cm

−1, which corresponds to vibrations of absorption of water adsorbed on the surface, corresponds to the X-ray phase analysis data. The indistinct peak centered at 3447 cm

−1 is due to stretching of the O–H bond in cobalt ferrite.

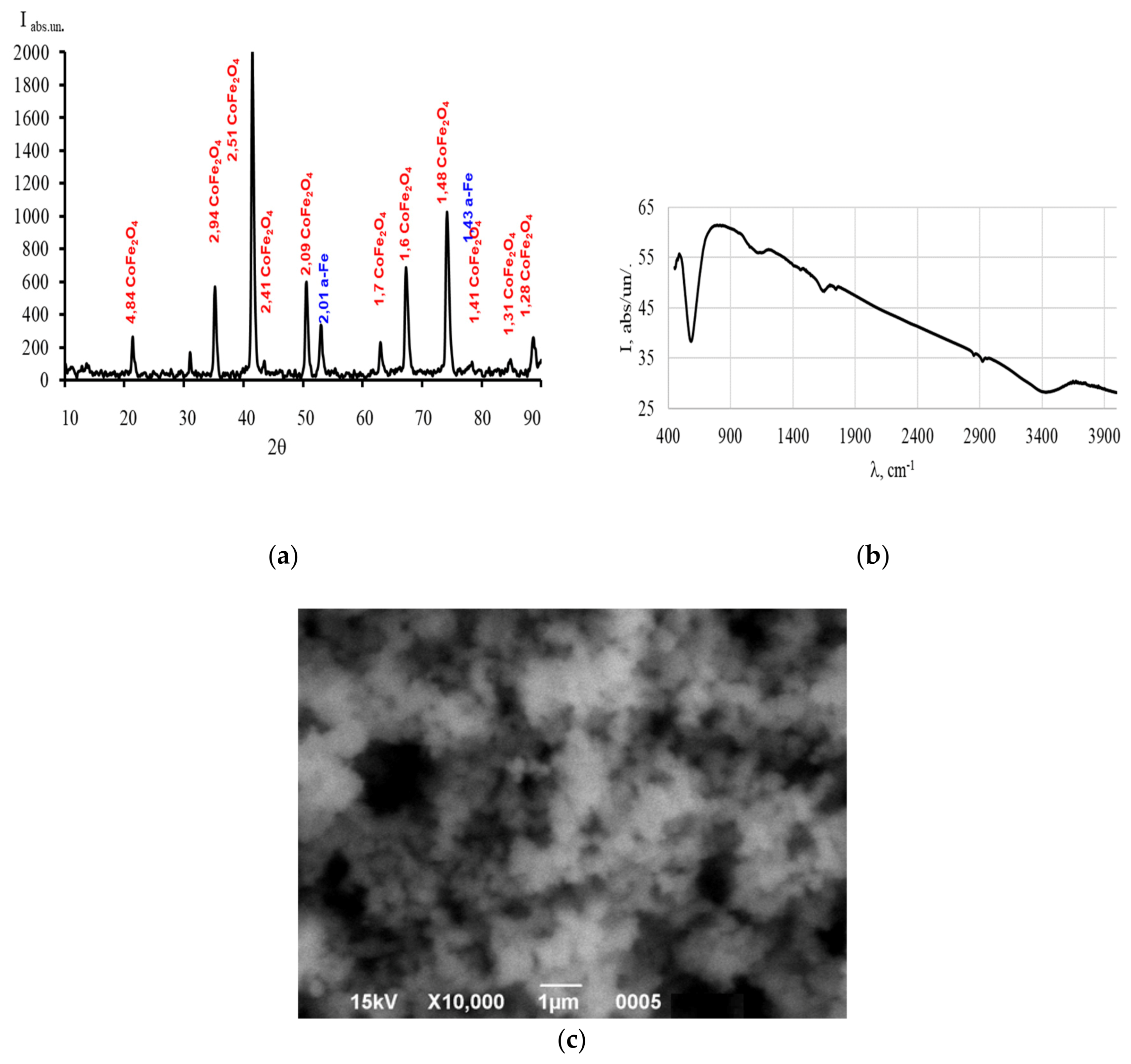

The saturation magnetization of the sample is 189.24 Emu/g, which is significantly higher than that observed for cobalt ferrite (

Figure 2).

This is due to the presence of metallic iron and the formation of the Fe/CoFe

2O

4 composite, i.e., the presence of a ferromagnet increases the magnetic properties. The saturation magnetization value is significantly higher than the values given in [

28]. The coercive force is 602 Oe.

Table 2 shows the main properties of the obtained composite, which characterize it as a promising material.

3.2. Investigation of the Photocatalytic Properties of the Composite

When studying the photocatalytic decomposition of pollutants, apparent rate constants of the destruction reaction in the presence of a photocatalyst were obtained with kinetic coefficients of linear regression for the zero, first and second order of the reaction (

Table 3).

Photocatalytic degradation occurs in pseudo-first order, and its kinetics can be expressed by the integral relationship:

Where C0 is the initial MB concentration (mg/L), t is the process time (min).

The linear plot of lnC/C0 versus t confirms a first-order reaction for всех пoлютантoв degradation. The correlation coefficient for the apparent first-order rate constant was close to unity.

Analyzing the reaction rate constants given in

Table 2, it is obvious that they can be arranged in order of decreasing stability as follows: ibuprofen → streptocide → furacilin → methylene blue → tetracycline. The most stable organic substance is ibuprofen, which contains a benzene ring, a carboxyl group, and a butyl radical. The presence of the benzene ring and the absence of reactive bonds makes ibuprofen and streptocide stable and persistent organic substances. Methylene blue, which has a stable aromatic structure, the heterocycle of which contains a sulfur atom and a cationic structure, is less stable and more reactive. Tetracycline contains four aromatic rings and hydroxyl groups, amido groups, and enol groups in its structure, which determines its lower stability and reactivity; however, the formation of stable intermediate compounds complicates its destruction.

3.3. Experimental Design and Photocatalystic Activity Studies

The influence of such parameters as the mass of the photocatalyst (X1), the volume of H2O2 (X2) and the time of treatment with UV radiation (X3) on the degradation of methylene blue (MB), furatsilin (F), tetracycline (TC), streptocide (S), ibuprofen (IF) was determined. The core of the central compositional design was a full factorial experiment (FFE) of the type with n=3. The degree of decomposition of the substance was used as the response function.

The experiment plan consisted of 8 factor points, 6 star points and 4 repeated in the central point, a total of 18 experiments, as shown in

Table 2. Replicas in the central point allow to estimate the error of the experiment and the adequacy of the model. The results obtained at the central point make it possible to determine the experimental mean, standard deviation and variation of the coefficients. The response function, expressed in percentages of degradation, for each combination of factors, is shown in

Table 4.

Mathematical equations obtained for the quadratic regression model are shown in

Table 5.

Table 5 shows the pharmaceutical preparations under consideration in the order of increasing their chemical resistance from the point of view of their structure and the possibility of formation of intermediates, as well as equations describing the degree of destruction of pollutants. All quadratic models have a high correlation coefficient close to unity (R2=0.98-0.99), which confirms the accuracy and reproducibility of the experiments.

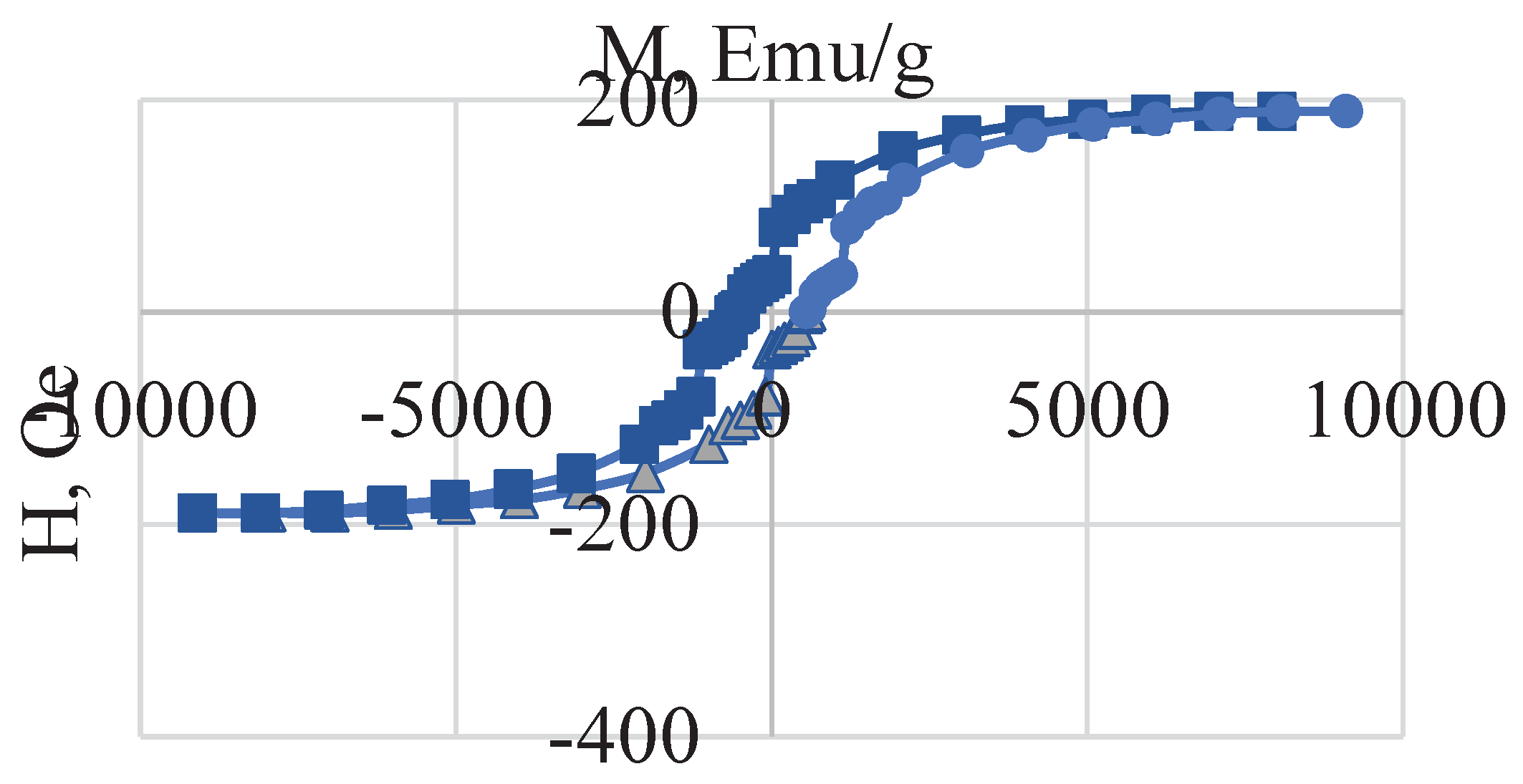

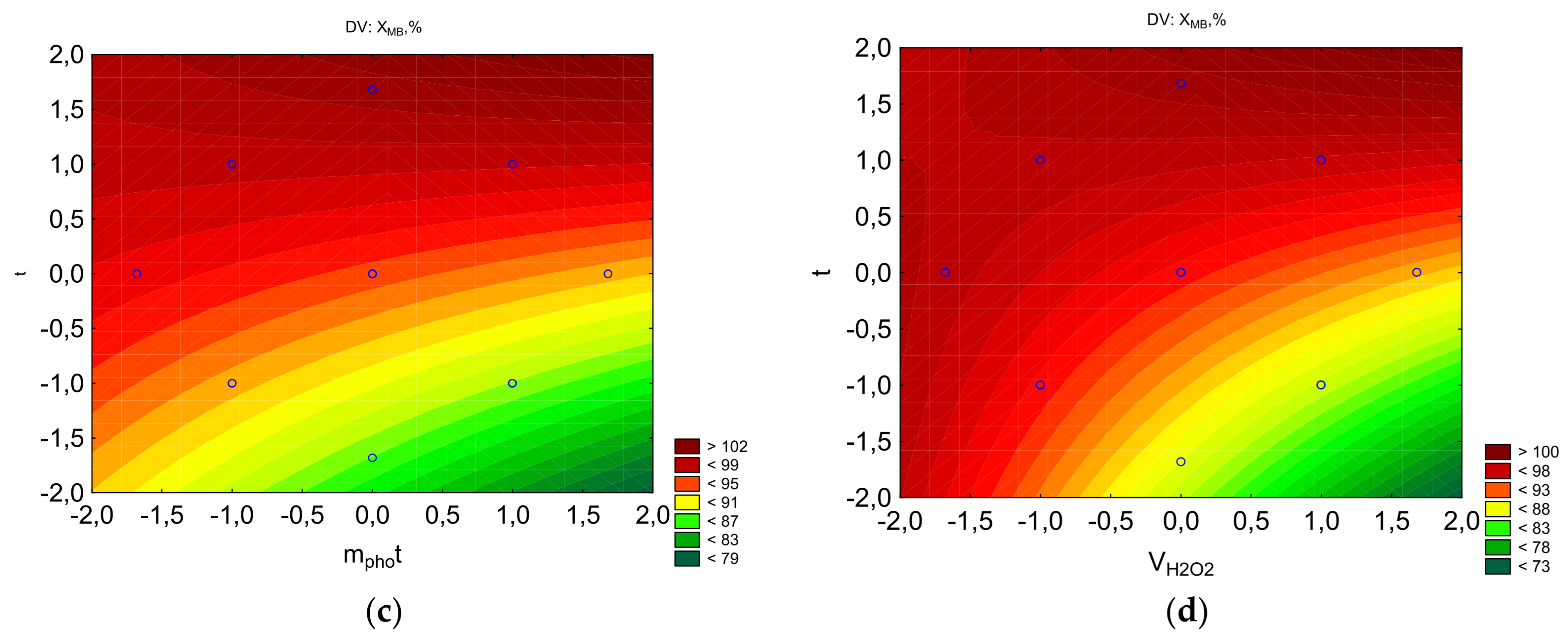

Let us examine in more detail the influence of these factors on the degradation of methylene blue. The dependence of the degree of degradation on the above factors during UV treatment is adequately described by equation 2 in

Table 4.

Figure 3a shows the Pareto diagram constructed for the absolute values of the calculated coefficients of Equation (2). All the studied factors have a significantly smaller impact on the degree of degradation than factor x3 (treatment time). Individual factors—photocatalyst mass and treatment time—have opposite effects. The most influential factor is treatment time. In the case of combined effects, the interaction of treatment time and peroxide concentration, as well as treatment time and photocatalyst mass, positively influences the degree of degradation.

Figure 3b shows that the response function isolines exhibit significant curvature, with maximum values observed at the minimum peroxide concentration and across virtually the entire range of photocatalyst mass variations. Furthermore, high degradation values correspond to combinations of 0.375 mL V(H

2O

2) and 30 min, as well as 0.125 mL V(H

2O

2) and 10 min. As seen in

Figure 3c, with a 30-min treatment, a high degradation rate is achieved at a photocatalyst concentration of 0.025 g.

Figure 3d shows a high degradation rate at the maximum treatment time and minimum peroxide concentration.

Analyzing all the resulting equations, it can be concluded that the degradation process of all pharmaceuticals (PPs) depends largely on the irradiation time of the solution, which significantly influences removal efficiency. Moreover, as the stability of the PP increases, the importance of irradiation time decreases, while the mass of the photocatalyst and the amount of hydrogen peroxide become more significant. The irradiation time of the solution indirectly influences the hydrolysis and dissociation of pollutants.

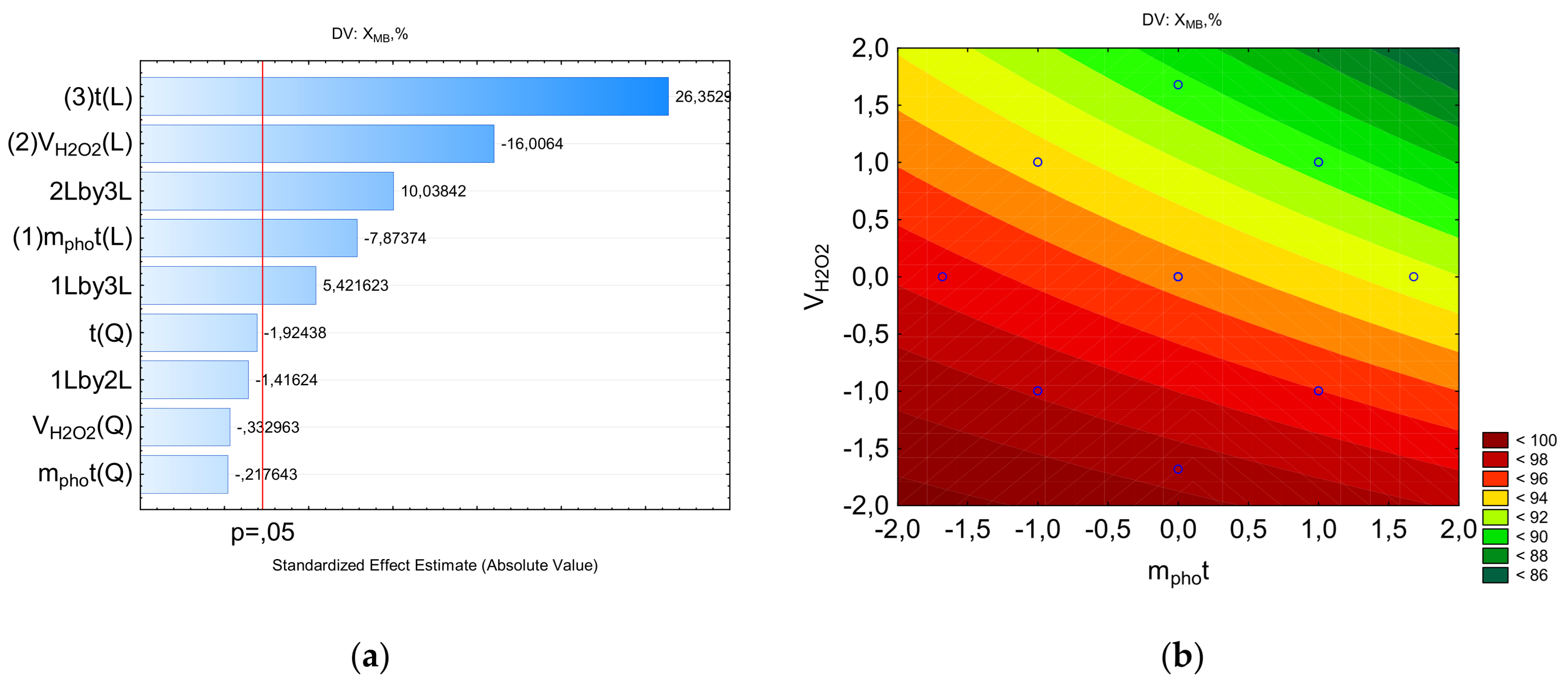

The influence of factors on the degradation process of tetracycline is shown in

Figure 4. The influence of H

2O

2 concentration in the studied range can be assessed by

Figure 4, in which it can be verified that when the concentration of H

2O

2 increased in the reaction mixture, the degree of destruction increased, only at high photocatalyst concentrations. However, it is clear from the graph that an increase in the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in the range of 0.2-2 leads to a decrease in the degree of destruction when the solution is treated for 10-20 minutes (

Figure 4). The data presented in the Pareto diagram in

Figure 4d confirm the behavior of the H

2O

2 concentration factor, since the linear effect X

2 is significant and negative (reduces the response), and the quadratic double effect (X

2X

3) is also negative, i.e., reduces the value of the response function.

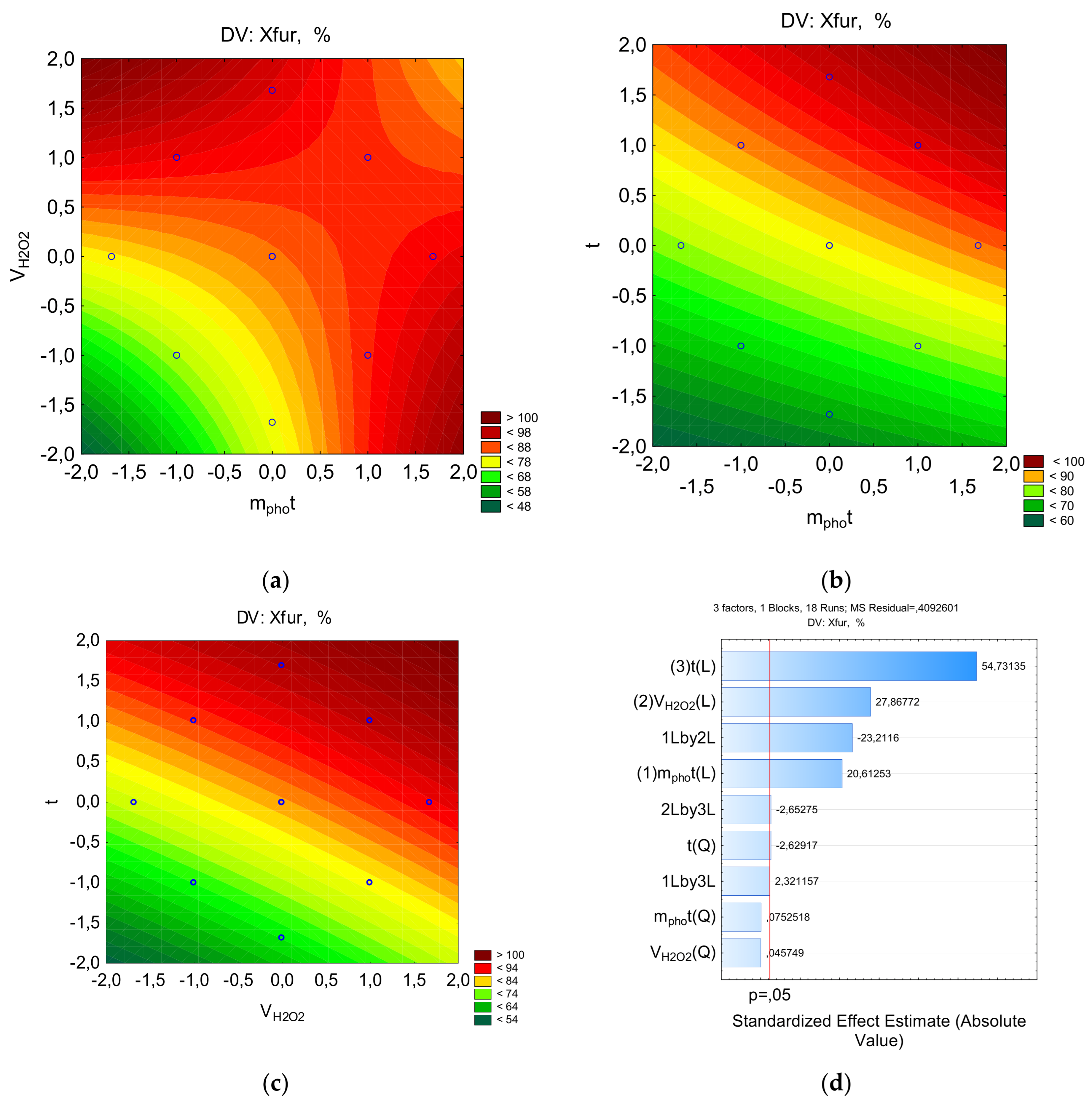

The effect of H

2O

2 concentration on the rate of furatsilin destruction in the presence of a photocatalyst is shown in

Figure 5. It is observed that the degree of destruction initially increases with increasing photocatalyst concentration -2-0, and then decreases in the interval 1-2. Similar relationships were observed in the study of furatsilin destruction using iron and nickel oxyhydroxides [

36]. The initial increase is associated with the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with the photocatalyst with the formation of hydroxyl ions. With an excess of oxidant, hydroxyl ions recombine with the formation of products with a lower redox potential, which reduces the degree of destruction. A directly proportional relationship is observed between the concentration of photocatalyst and hydrogen peroxide: an increase in the photocatalyst content allows you to increase the peroxide concentration. Therefore, to achieve a higher rate of furatsilin degradation, the concentration of H

2O

2 should be optimal.

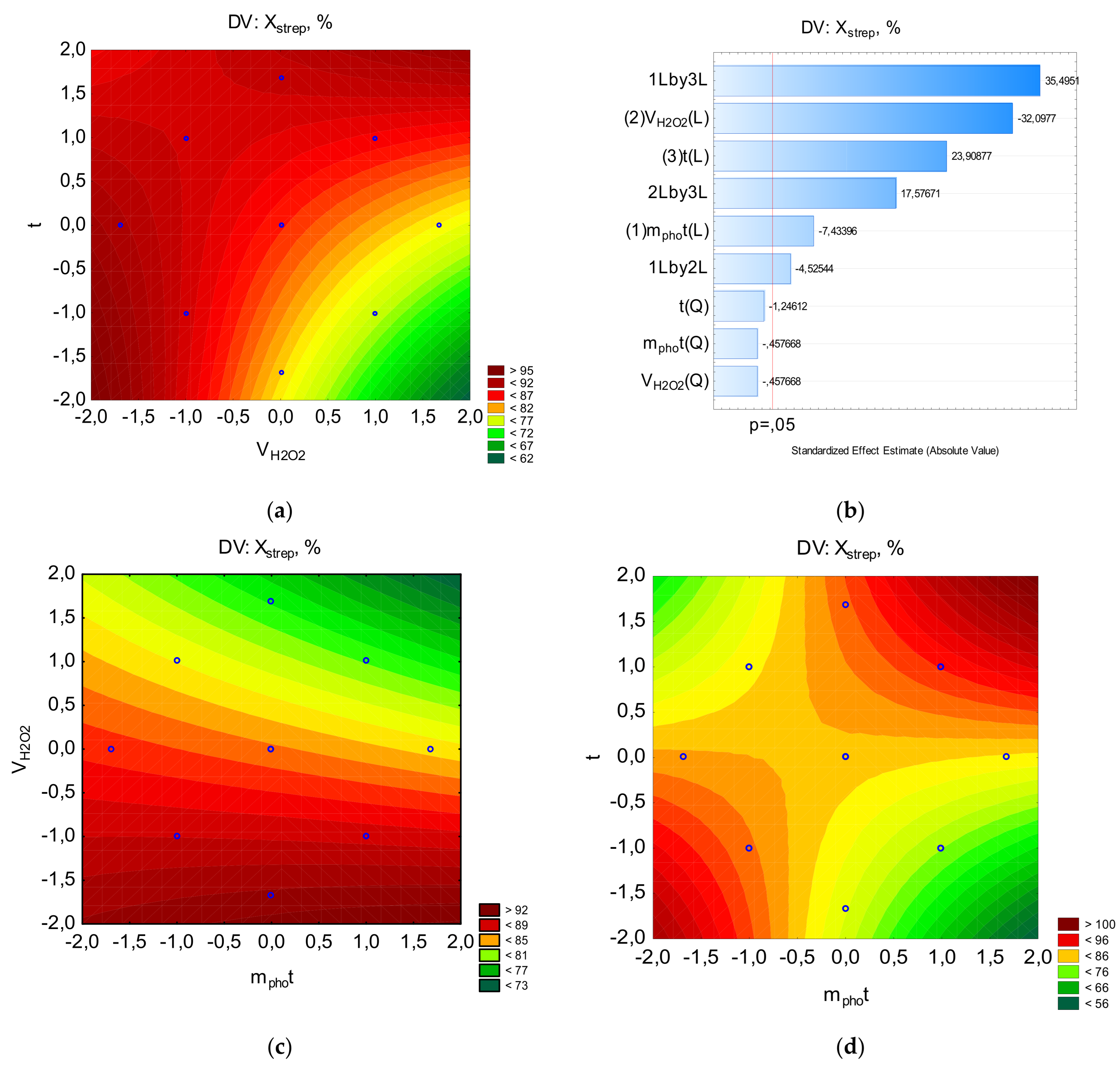

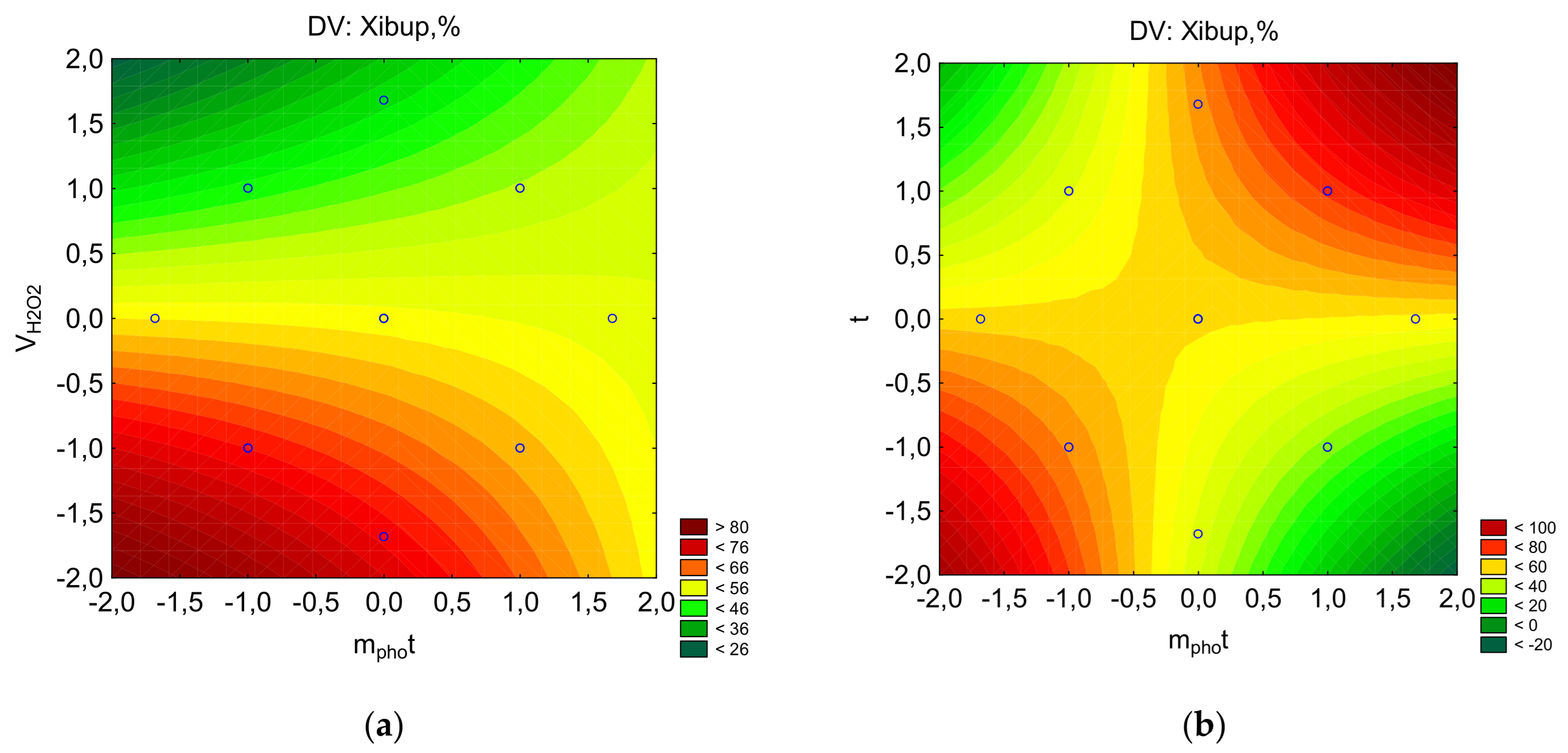

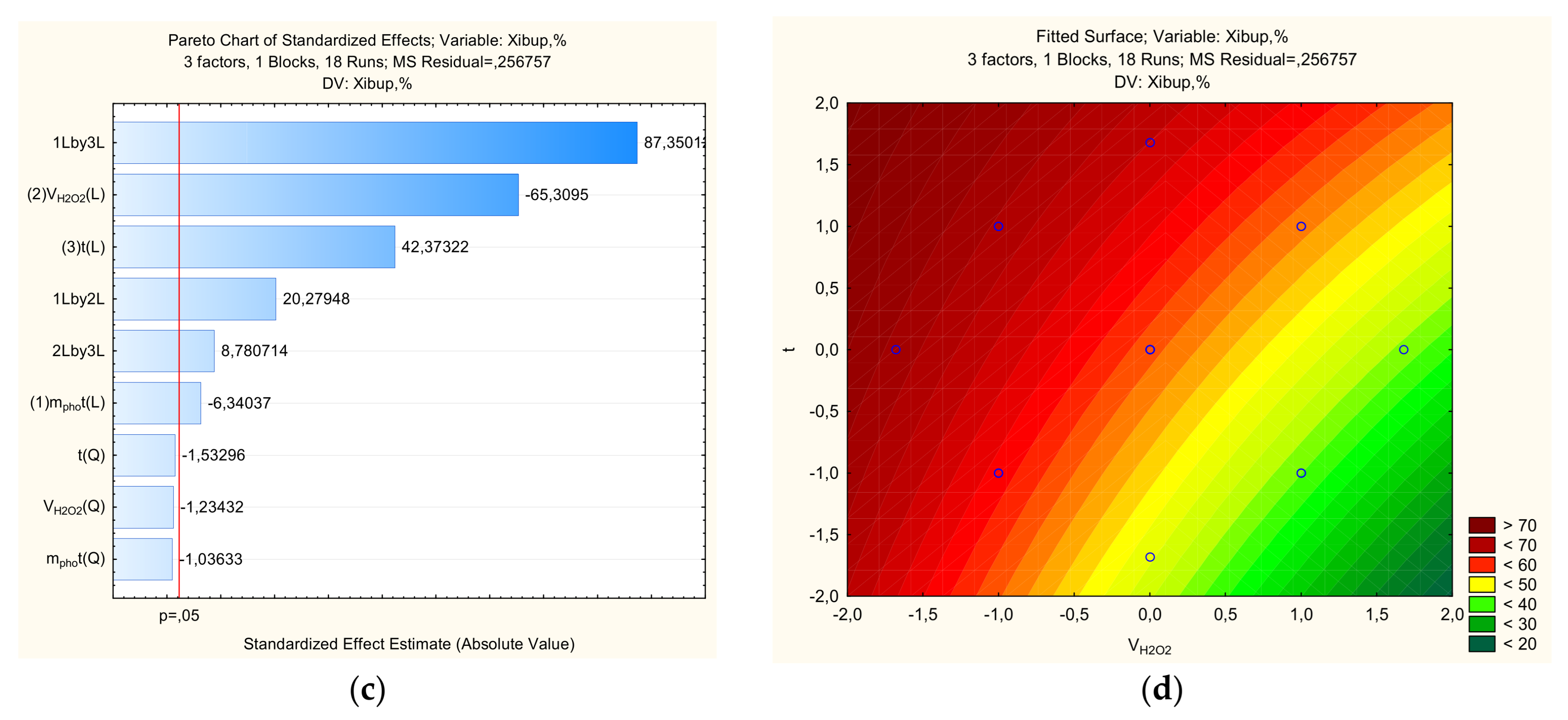

Since the X=f(mphot, τ) dependence for ibuprofen and streptocide has a saddle-shaped surface, it can be assumed that there is a region of metastable equilibrium, where an increase in the amount of photocatalyst can increase the degree of destruction only with an increase in the processing time, and vice versa (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). That is, competing trends are present, where maximum destruction depends on a combination of factors, and the optimal parameters correspond to specific regions on a single line. As can be seen from

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the region of high X values for ibuprofen and streptocide is significantly smaller than in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

4. Conclusions

Magnetic nanoparticles of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite were synthesized by processing coprecipitated hydroxides and hydrothermal treatment. The average particle size of the obtained samples, estimated by SEM microanalysis, was 90–100 nm. Magnetic properties demonstrate high saturation magnetization values of 189.24 EMU/g. The Hc value is approximately 602 Oersted. The results of studying Fe/CoFe2O4 nanocomposites demonstrate their potential as a new type of highly efficient photocatalyst in the degradation of pharmaceuticals (PPs). The main kinetic parameters of the PP degradation process were determined.

Experimental and statistical mathematical models have been developed, and the largest impact factors have been established. Using a different method of planning an experiment with variations in certain factors, it was possible to determine which are the most significant influxes in the process of PPs degradation. It has been established that during the destruction of more persistent pollutants, a consistent concentration of photocatalyst and water peroxide is important. The influx of concentration of water peroxide and catalyst is extreme. For more unstable parts, the most important factor is the complexity of processing.

In addition, analysis of variance showed the consistency between experimental data and theoretical values, so that mathematical models were found to be adequate.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, L.F.; methodology, V.P.; software, V.P.; validation, B.T. and V.P.; formal analysis, B.T.; investigation, L.F.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IR |

Infrared spectrophotometer |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| UV-visible |

Ultraviolet-visible |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| PPs |

Pharmaceuticals |

| APIs |

Active pharmaceutical ingredients |

| AOPs |

Advanced oxidation processes |

| CIP |

Ciprofloxacin |

| LEV |

Levofloxacin |

| RhB |

Rhodamine B |

| MWCNTs |

Multiwalled carbon nanotubes |

| RB |

Rose bengal |

| FFE |

Full factorial experiment |

| MB |

Methylene blue |

| F |

Furatsilin |

| TC |

Tetracycline |

| S |

Streptocide |

| IF |

Ibuprofen |

References

- O’Flynn, D.; Lawler, J.; Yusuf, A.; Parle-McDermott, A.; Harold, D.; Mc Cloughlin, T.; Holland, L.; Regan, F.; White, B. A review of pharmaceutical occurrence and pathways in the aquatic environment in the context of a changing climate and the COVID-19 pandemic. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A.; Labad, F.; Scheiber, S.; Criollo, R.; Nikolenko, O.; Pérez, S.; Ginebreda, A. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and risk assessment in urban groundwater. Adv. Geosci. 2022, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Hao, H.; Xu, N.; Liang, X.; Gao, D.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tao, H.; Wong, M. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in water, sediments, aquatic organisms, and fish feeds in the Pearl River Delta: Occurrence, distribution, potential sources, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, P.K.; Kalogirou, C.; Kanellou, E.; Vaitsis, C.; Savvidou, M.G.; Sourkouni, G.; Zorpas, A.A.; Argirusis, C. Key points of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for wastewater, organic pollutants and pharmaceutical waste treatment: A mini review. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qiao, J.; Sun, Y.; Dong, H. The profound review of Fenton process: What’s the next step? J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.D.N.; Santana, C.S.; Velloso, C.C.V.; Da Silva, A.H.M.; Magalhães, F.; Aguiar, A. A review on the treatment of textile industry effluents through Fenton processes. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 155, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalık, Ç.; Çifçi, D.İ. Comparison of kinetics and costs of Fenton and photo-Fenton processes used for the treatment of a textile industry wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Nasernejad, B.; Sanavi Fard, M. Challenges and future roadmaps in heterogeneous electro-fenton process for wastewater treatment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, R.; Yasar, A.; Ikhlaq, A.; Nissar, H.; Nizami, A.S. Comparison of ozonation, Fenton, and photo-Fenton processes for the treatment of textile dye-bath effluents integrated with electrocoagulation. J. Water Process. Eng. 2022, 46, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Liaqat, A.; Imran, M.; Javaid, A.; Hussain, N.; Jesionowski, T.; Bilal, M. Development of zinc ferrite nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic performance for remediation of environmentally toxic pharmaceutical waste diclofenac sodium from wastewater. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaldo, M.V.; Marchetti, S.G.; Elías, V.R.; Mendieta, S.N.; Crivello, M.E. Degradation of anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac using cobalt ferrite as photocatalyst. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 166, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.A.H.; Shamma, R.N.; Elagroudy, S.; Adewuyi, A. Chitosan incorporated nickel ferrite photocatalyst for complete photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin, ampicillin and erythromycin in water. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Acharya, R.; Parida, K. Spinel-ferrite-decorated graphene-based nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic detoxification of organic dyes in aqueous medium: A review. Water 2023, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, L.; Rajaram, A. Constructive Z-scheme interfacial charge transfer of a spinel ferrite-supported g-C3N4 heterojunction architect for photocatalytic degradation. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 172987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir, M.; Aleem, W.; Akhtar, M.N.; Din, A.A.; Yasmeen, G.; Ashiq, M.N. Synthesis and characterizations of Co–Zr doped Ni ferrite/PANI nanocomposites for photocatalytic methyl orange dye degradation. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2022, 624, 413392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, S.; Ren, Q.; Jin, Z.; Ding, Y.; Xiong, C.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Oh, W.C. Microwave absorption and photocatalytic activity of MgxZn1− x ferrite/diatomite composites. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2022, 59, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Song, Y. Recent advances in spinel ferrite-based magnetic photocatalysts for efficient degradation of organic pollutants. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 1465–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asokan, J.; Kumar, P.; Arjunan, G.; Shalini, M.G. Photocatalytic Performance of Spinel Ferrites and their Carbon-Based Composites for Environmental Pollutant Degradation. J. Cluster Sci. 2025, 36, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmelesi, O.K.; Ammar-Merah, S.; Nkambule, T.T.; Nkosi, B.; Liu, X.; Kefeni, K.K.; Kuvarega, A.T. The photodegradation of naproxen in an aqueous solution employing a cobalt ferrite-carbon quantum dots (CF/N-CQDs) nanocomposite, synthesized via microwave approach. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugham, N.; Mariappan, A.; Eswaran, J.; Daniel, S.; Kanthapazham, R.; Kathirvel, P. Nickel ferrite-based composites and its photocatalytic application–A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 8, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patar, S.; Mittal, R.; Yasmin, F.; Bhuyan, B.K.; Borthakur, L.J. Photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics by N-doped carbon nanoflakes-nickel ferrite composite derived from algal biomass. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 142908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatskiy, D.; Budnikova, Y.; Bratskaya, S.; Vasilyeva, M. TiO2-CoFe2O4 and TiO2-CuFe2O4 composite films: A new approach to synthesis, characterization, and optical and photocatalytic properties. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Alabada, R.; Usman, M.; Alothman, A.A.; Tufail, M.K.; Mohammad, S.; Ahmad, Z. Synthesis of visible-light-responsive lanthanum-doped copper ferrite/graphitic carbon nitride composites for the photocatalytic degradation of toxic organic pollutants. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darandale, S.; Hase, D.; Mane, K.; Khedkar, J.; Murade, R.; Dichayal, S.; Murade, V. Synthesis of Spinel Ferrites and Their Composites: A Comprehensive Review on Synthesis Methods, Characterization Techniques, and Photocatalytic Applications. J. Chem. Rev. 2025, 7, 216–235. [Google Scholar]

- Phor, L.; Malik, J.; Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, V.; Rani, G.M.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Chahal, S. Magnetically separable NiZn-ferrite/CeO2 nanorods/CNT ternary composites for photocatalytic removal of organic pollutants. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Ubhi, M.K.; Jeet, K.; Singla, C.; Kaur, M. A review on impacting parameters for photocatalytic degradation of organic effluents by ferrites and their nanocomposites. Processes 2023, 11, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, N.; Abbas, Q.; Yaseen, M.; Jilani, A.; Zahid, M.; Iqbal, J.; Murtaza, A.; Janczarek, M.; Jesionowski, T. Coal fly ash-based copper ferrite nanocomposites as potential heterogeneous photocatalysts for wastewater remediation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 565, 150542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakirzyanov, R.I.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Zdorovets, M.V.; Zheludkevich, A.L.; Shlimas, D.I.; Abmiotka, N.V.; Trukhanov, A.V. Impact of thermobaric conditions on phase content, magnetic and electrical properties of the CoFe2O4 ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 954, 170083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, L. Photocatalytic activity of spinel ferrites CoxFe3−xO4 (0.25< x< 1) obtained by treatment contact low-temperature non-equilibrium plasma liquors. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 4585. [Google Scholar]

- Biswal, D.; Peeples, B.N.; Peeples, C.; Pradhan, A.K. Tuning of magnetic properties in cobalt ferrite by varying Fe+2 and Co+2 molar ratios. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2013, 345, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.S.; Longhi, M.R.; Garnero, C. Pharmaceutical systems as a strategy to enhance the stability of oxytetracycline hydrochloride polymorphs in solution. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.K.; Chan, W.C.; Wong, H.N.; Li, K.Y.; Wu, W.K.; Fan, K.M.; Sung, H.H.; Williams, I.D.; Prosperi, D.; Melato, S.; et al. Facile oxidation of leucomethylene blue and dihydroflavins artemisinins: Relationship with flavoenzyme function and antimalarial mechanism of action. ChemMedChem 2010, 5, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastrakov, M.; Starosotnikov, A. Recent progress in the synthesis of Drugs and bioactive molecules core. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białk-Bielińska, A.; Stolte, S.; Matzke, M.; Fabiańska, A.; Maszkowska, J.; Kołodziejska, M.; Liberek, B.; Stepnowski, P.; Kumirska, J. Hydrolysis of sulphonamides in aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 221, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, H.; Wang, G.; Sun, J. Enantioselective pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen and involved mechanisms. Drug Metab. Rev. 2005, 37, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, L. H2O2/UV catalytic degradation of furacilin by Fe-Ni oxyhydroxides synthesized via coprecipitation. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, A1–A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Composite characteristics Fe/CoFe2O4 (a) X-ray pattern of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite; (b) SEM image of nanoparticles of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite; (c) FT-IR spectra of nanoparticles of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

Figure 1.

Composite characteristics Fe/CoFe2O4 (a) X-ray pattern of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite; (b) SEM image of nanoparticles of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite; (c) FT-IR spectra of nanoparticles of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

Figure 2.

Magnetic hysteresis loop of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

Figure 2.

Magnetic hysteresis loop of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

Figure 3.

The counter plots showing the parameters influencing the percentage of MB to be removed: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 3.

The counter plots showing the parameters influencing the percentage of MB to be removed: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 4.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of tetracycline for removal: a-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); b-X=f(t, mphot); c-X=f(t, VH2O2), d-Pareto chart to X.

Figure 4.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of tetracycline for removal: a-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); b-X=f(t, mphot); c-X=f(t, VH2O2), d-Pareto chart to X.

Figure 5.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of furacilin for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 5.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of furacilin for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 6.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of streptocide for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 6.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of streptocide for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 7.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of ibuprofen for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Figure 7.

The counter plots showing the effect parameters on the percent of ibuprofen for removal: a-Pareto chart to X; b-X=f(VH2O2, mphot); c-X=f(t, mphot); d-X=f(t, VH2O2).

Table 1.

Natural and coded values of factor levels.

Table 1.

Natural and coded values of factor levels.

| Factor |

Name |

Dimension |

Value |

| Maximum |

Minimum |

| X1

|

Photocatalyst mass |

mg/50 mL |

0.075 |

0.025 |

| X2

|

H2O2 volume |

ml/50mL |

0.375 |

0.125 |

| X3

|

Processing time |

min |

30 |

10 |

Table 2.

Properties of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

Table 2.

Properties of the Fe/CoFe2O4 composite.

| Parameters of the sample |

|---|

| No. |

Indicator |

Explanation |

Value |

| 1 |

L311, A |

Crystallite size on the 311 plane |

937 |

| 2 |

L441., A |

Crystallite size on the 441 plane |

1041 |

| 3 |

L,A

|

Average crystallite size |

1046 |

| 4 |

M, % |

Percentage of microstrains |

10.1*10−4

|

| 5 |

D, cm−2

|

Dislocation density on the 311 plane |

10.45*1010

|

| 6 |

D, cm−2

|

Dislocation density on the 441 plane |

9.21*1010

|

| 7 |

I p Fe, Abs. un. |

Peak X-ray intensity |

1209 |

| 8 |

а,A |

Crystal lattice parameter |

8.3901 |

| 9 |

Eg, еV |

Gap width |

2.1 |

| 10 |

Ms, Emu/g |

Saturation magnetization |

189.24 |

| 11 |

Hc, Oe |

Coercive force |

601 |

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for pollutant degradation.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for pollutant degradation.

| pollutant |

methylene blue |

furacilin |

tetracycline |

streptocide |

ibuprofen |

Reaction

order |

Equation

|

Reaction

Rate

constant |

R2

|

Reaction

Rate

constant |

R2

|

Reaction

Rate

constant |

R2

|

Reaction

Rate

constant |

R2

|

Reaction

Rate

constant |

R2

|

| zero |

V=k |

0.0163 |

0.59 |

0.065 |

0.953 |

0.085 |

0.77 |

0.042 |

0.92 |

0.0192 |

0.98 |

| first |

V=k[C] |

0.1282 |

0.99 |

0.0374 |

0.986 |

0.347 |

0.99 |

0.022 |

0.98 |

0.0187 |

0.99 |

| second |

V=k[C]2

|

19.6301 |

0.69 |

0.1436 |

0.886 |

0.3168 |

0.95 |

0.162 |

0.87 |

0.0428 |

0.844 |

Table 4.

Plan of central composite rotatable design for three factors and its results.

Table 4.

Plan of central composite rotatable design for three factors and its results.

| No. |

mphot

|

VH2O2

|

τ |

Xmb, % |

Xfurac, % |

Xibup, % |

Xstrep, % |

Xtetra, % |

| 1 |

+1 |

+1 |

+1 |

98.14 |

98.68 |

73.19 |

90.56 |

76.90 |

| 2 |

-1 |

+1 |

+1 |

98.20 |

100.00 |

36.65 |

82.98 |

36.50 |

| 3 |

1 |

-1 |

+1 |

98.80 |

100.32 |

81.23 |

94.02 |

76.80 |

| 4 |

-1 |

-1 |

+1 |

99.36 |

81.54 |

58,32 |

83.72 |

63.10 |

| 5 |

+1 |

+1 |

-1 |

82.62 |

78.41 |

27,22 |

69.02 |

48.58 |

| 6 |

-1 |

+1 |

-1 |

88.66 |

82.92 |

53.40 |

82.73 |

31.38 |

| 7 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

92.96 |

78.35 |

41.40 |

83.02 |

42.60 |

| 8 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

96.23 |

61.51 |

81.23 |

94.02 |

39.50 |

| 9 |

1.68 |

0 |

0 |

92.30 |

91.36 |

55.20 |

83.57 |

65.94 |

| 10 |

-1.68 |

0 |

0 |

96.20 |

79.39 |

57.96 |

86.44 |

37.72 |

| 11 |

0 |

1.68 |

0 |

90.10 |

93.65 |

41.52 |

78.82 |

46.22 |

| 12 |

0 |

-1.68 |

0 |

98.30 |

77.07 |

71.64 |

91.20 |

57.44 |

| 13 |

0 |

0 |

1.68 |

99.80 |

99.29 |

66.27 |

89.73 |

71.30 |

| 14 |

0 |

0 |

-1.68 |

87.22 |

68.90 |

46.89 |

80.29 |

32.36 |

| 15 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

94.50 |

85.30 |

56.58 |

85.01 |

51.83 |

| 16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

94.70 |

85.68 |

56.58 |

85.01 |

51.83 |

| 17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

94.40 |

85.30 |

56.58 |

85.01 |

51.83 |

| 18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

94.80 |

85.68 |

56.58 |

85.01 |

51.83 |

Table 5.

Statistical models describing the influence of factors on the destruction of pollutants.

Table 5.

Statistical models describing the influence of factors on the destruction of pollutants.

| No |

Pollutant |

Equation |

intermediates |

name |

| 1 |

Tetracycline |

X=51.83+8.92mad-3.48 VH2O2 + 0.02 VH2O22 + 11.48 t − 0.2 t2+5.1 mad VH2O2 + 4.22 mad t - 3.05 VH2O2 t |

Epitetracycline (epimer at position C4)

Isotetracycline, apo-tetracycline, anhydrotetracycline, epitetracycline, resistant, melanin-like polymers, organic acids

[31] |

(4S,6S,12aS)-4-(dimethylamino)-1,4,4a,5,5a,6,11,12a-octahydro-3,6,10,12,12a-pentahydroxy-6-methyl-1,11-dioxonaphthacene-2-carboxamide |

| 2 |

MB |

X=94.58-1.2mad-0.03 mad2 - 2.45 VH2O2 - 0.05 VH2O22 + 4.049 t − 0.29 t2- 0.28 mad VH2O2 + 1.08 mad t + 2.01 VH2O2 t |

Leukomethylene blue, sulfoxide derivatives of phenothiazine

[32] |

3,7-Bis (dimethylamino) phenothiazin-5-ium chloride. |

| 3 |

Furatsilin |

X=85.47+3.56mad + 0,014 m2ad + 4.82 VH2O2 + 0.008VH2O22 + 9.47 t − 0.47 t2-5.25 mad VH2O2 + 0.525mad t - 0.6 VH2O2 t |

Aminofural, nitrosofural, hydrazone, organic acids

[33] |

[(E)-[(5-nitrofuran-2-yl)methylidene]amino]urea |

| 4 |

Streptocide |

X=85.22-0.85mad-0.054 mad2 - 3.68 VH2O2 - 0.054 VH2O22 + 2.74 t − 0.14 t2-0.68 mad VH2O2 + 5.32 mad t + 2.63 VH2O2 t |

Aniline, sulfamic acid

[34] |

4-aminobenzenesulfonamide |

| 5 |

Ibuprofen |

X=56.82-0.87mad-0.14 mad2 - 8.95 VH2O2 - 0.176 VH2O22 + 5.81 t − 0.218 t2+3.63 mad VH2O2 + 15.64 mad t + 1.57 VH2O2 t |

Hydroxy- and carboxy-ibuprofen

[35] |

(RS)-2-(4-(2-methylpropyl)phenyl)propanoic acid |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).