1. Introduction

Bortezomib, a 26S proteasome inhibitor, is used in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) and mantle cell lymphoma, which interferes with the survival of malignant plasma cells and has significantly improved survival outcomes [

1]. Although it has transformed patient outcomes, there is an emerging consensus of its potential negative effects on the heart. While early trials mainly reported low blood pressure and nerve damage, real-world data now point to a broader range of cardiovascular problems, including cardiomyopathy and cardiac failure [

2].

Patients with MM and amyloidosis pose elevated cardiac risk due to comorbidities like kidney dysfunction, increased blood viscosity, and direct infiltration of the heart by abnormal proteins, making it even more challenging to attribute new heart issues to bortezomib [

3].

Bortezomib affects the heart through multiple biological pathways. It harms the endoplasmic reticulum, generates oxidative stress that impairs mitochondria, and interferes with autophagy which is a vital process for heart cell health [

4]. Moreover, its impacts on the immune and blood systems can potentiate conditions like infection and anemia, which further affects the heart negatively [

5]. These challenges are more relevant in older patients who often have hypertension or coronary artery disease [

6].

While some cardiovascular risks were observed in trials, our real-world analysis of FAERS data provides a more detailed examination of cardiac diseases. By focusing on cases where bortezomib was directly implicated, cardiac amyloidosis (ROR: 35.578), atrial flutter (ROR: 4.339), and cardiac failure (ROR: 3.183) had elevated risks. For example, patients with amyloidosis reported more cardiac amyloidosis events, likely due to bortezomib aggravating fibril buildup [

7].

Recent research in cardio-oncology has shown that targeted treatments, such as bortezomib, can harm the heart through mechanisms including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and endothelial injury [

8]. Our findings back this up, showing associations between bortezomib and serious outcomes like hospitalization and even death. The combination of blood-related side effects and infections, like pneumonia and low platelet counts, likely contributes to this chain reaction[

9].

Using surveillance tools like FAERS gives us a clearer picture of how these risks play out in the real world, particularly in vulnerable populations like older adults [

10]. Overall, our study suggests a need for more careful and focused personalized care for patients receiving bortezomib.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preparation

Data Extraction

Data were obtained from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) through OpenVigil 2.1 (build: OpenVigil 2.1–MedDRA–v24, data coverage 2004Q1–2025Q2), a pharmacovigilance platform [

11]. For this study, adverse event (AE) reports in which bortezomib was recorded as a suspect drug were extracted up to May 19, 2025. Adverse events were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 28.0 (released March 2025).

Case Selection and Role Codes

For each Preferred Term (PT), all unique reports were initially counted irrespective of role designation. Cases in which bortezomib was identified as the primary suspect (PS) or secondary suspect (SS) were included in the main disproportionality analysis. The category labeled as “Other” is an umbrella term encompassing interacting (I) and concomitant (C) roles which were included only in sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the observed associations.

Deduplication and Unit of Analysis

To ensure accurate case counts, duplicate records were removed using OpenVigil’s default deduplication algorithm, which collapses reports by case ID, retains the highest case version, removes entries flagged as duplicates, and consolidates follow-up reports into a single unique case. The number of adverse events was calculated by counting unique cases, not Individual Safety Reports (ISRs). This approach, using the unique case as the unit of analysis for all disproportionality calculations reduced overcounting from cases reporting multiple AEs and provided a more accurate measure of the number of Adverse events.

Event Identification and Grouping

Cardiovascular events were identified using a two-stage process: 1. Screening: We screened for potential cardiac events using Preferred Terms (PTs) in their narrow scope. The Preferred Terms used were for example: 'Cardiac failure', 'Cardiomyopathy', 'ischemic heart disease', and 'Myocarditis' (MedDRA v28.0). 2. Reporting: For the final analysis and signal detection, we investigated closely the PTs and reported results based on the number of unique cases. Ultimately, generating clinically and statically significant signals.

2.2. Disproportionality Analysis

The reporting odds ratio (ROR) method was applied to detect statistically significant signals in the data, following standard pharmacovigilance practices [

12]. This analysis was limited to cases in which bortezomib was listed as a suspect drug and was critical for identifying bortezomib’s unique cardiac risk profile. Signal Detection and Thresholds Disproportionality analyses were performed at the case level. The reporting odds ratio (ROR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used as the primary metric. A signal was considered positive when at least three unique cases (N ≥ 3) were reported for a given PT and the lower bound of the 95% CI exceeded 1, corresponding to χ² ≥ 3.84 (α = 0.05). Exploratory signals that did not meet these thresholds were flagged as hypothesis-generating.

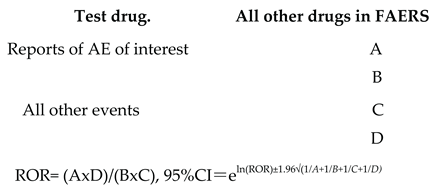

Calculation of ROR.Reporting odds ratio (ROR) with test drug versus all other drugs in the FAERS database was calculated as:

3. Results

3.1. Disproportionality Signals for Cardiac Adverse Events

A search query was performed for all Adverse events associated with Bortezomib compared to the entire database since it’s FDA approval from May 2003 to May 2025. To reduce common symptoms, MedDRA has already been classified into Preferred Terms. A compiled list based on the number of unique cases are summarized in

Table 1 with their respective ROR (95%Cl). 12 Adverse Events were associated with a cardiac disease and exhibited statistically significant RORs for Bortezomib relative to the entire database.

In MedDRA, a Preferred Term (PT) is known as a single, standardized medical concept used for coding adverse events, such as “nausea” or “anaphylactic reaction.” A unique case, on the other hand, is a subset of a Preferred Term (PT) which describes an individual clinical scenario that may involve multiple symptoms, lab abnormalities, or diagnoses. The number of Adverse events on MedDRA’s database correlated closer to the number of unique cases rather than the PT. Therefore, most of this paper’s data utilizes unique cases over the more commonly used unit of PT.

We extracted a comprehensive list of adverse events and unique case IDs in the entire database (from May 2003 to May 2025). Disproportionality analysis using the reporting odds ratio (ROR) revealed statistically significant pharmacovigilance signals for twelve cardiac AEs (

Table 1). Cardiac amyloidosis exhibited the strongest signal (ROR 35.578; 95% CI 28.158 – 44.953), indicating over a 35-fold higher reporting frequency compared with all drugs in the database. Atrial flutter (ROR 4.339; 95% CI 3.414 – 5.515) and left ventricular dysfunction (ROR 4.254; 95% CI 3.259 – 5.554) also showed elevated RORs, revealing a higher vulnerability in treated patients. More commonly reported events, such as Cardiac failure (ROR 3.183; 95% CI 2.925 – 3.463) and Atrial fibrillation (ROR 2.649; 95% CI 2.430 – 2.887), remained significant but with lower magnitude signals.

Table 1.

Disproportionality analysis of cardiac adverse events: The association between bortezomib and twelve cardiac adverse events (AEs) was evaluated using Reporting Odds Ratios (RORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Table 1.

Disproportionality analysis of cardiac adverse events: The association between bortezomib and twelve cardiac adverse events (AEs) was evaluated using Reporting Odds Ratios (RORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

| |

Adverse Event Preferred Term (PT) |

ADR |

Number of Drug Events |

Number of reports for AE in Full database (all drugs) |

ROR (95% Cl) |

| 1 |

Cardiac failure |

Yes |

552 |

45633 |

3.183 (2.92 5- 3.463) |

| 2 |

Atrial fibrillation |

Yes |

529 |

52383 |

2.649 (2.43 - 2.887) |

| 3 |

Cardiomyopathy |

Yes |

97 |

9014 |

2.81 (2.3 - 3.433) |

| 4 |

Cardiac amyloidosis |

Yes |

80 |

661 |

35.578 (28.158 - 44.953) |

| 5 |

Atrial flutter |

Yes |

68 |

4115 |

4.339 (3.414 - 5.515) |

| 6 |

Myocarditis |

Yes |

57 |

6611 |

2.245 (1.73 - 2.914) |

| 7 |

Left Ventricular dysfunction |

Yes |

55 |

3393 |

4.254 (3.259 - 5.554) |

| 8 |

Cardiac Failure acute |

Yes |

48 |

3437 |

3.657 (2.75 -4.862) |

| 9 |

Supraventricular tachycardia |

Yes |

43 |

5150 |

2.173 (1.61 - 2.934) |

| 10 |

Right ventricular failure |

Yes |

33 |

3740 |

2.297 (1.631 - 3.237) |

| 11 |

Congestive cardiomyopathy |

Yes |

36 |

2910 |

3.233 (2.327 - 4.492) |

| 12 |

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

Yes |

12 |

912 |

3.44 (1.946 - 6.081) |

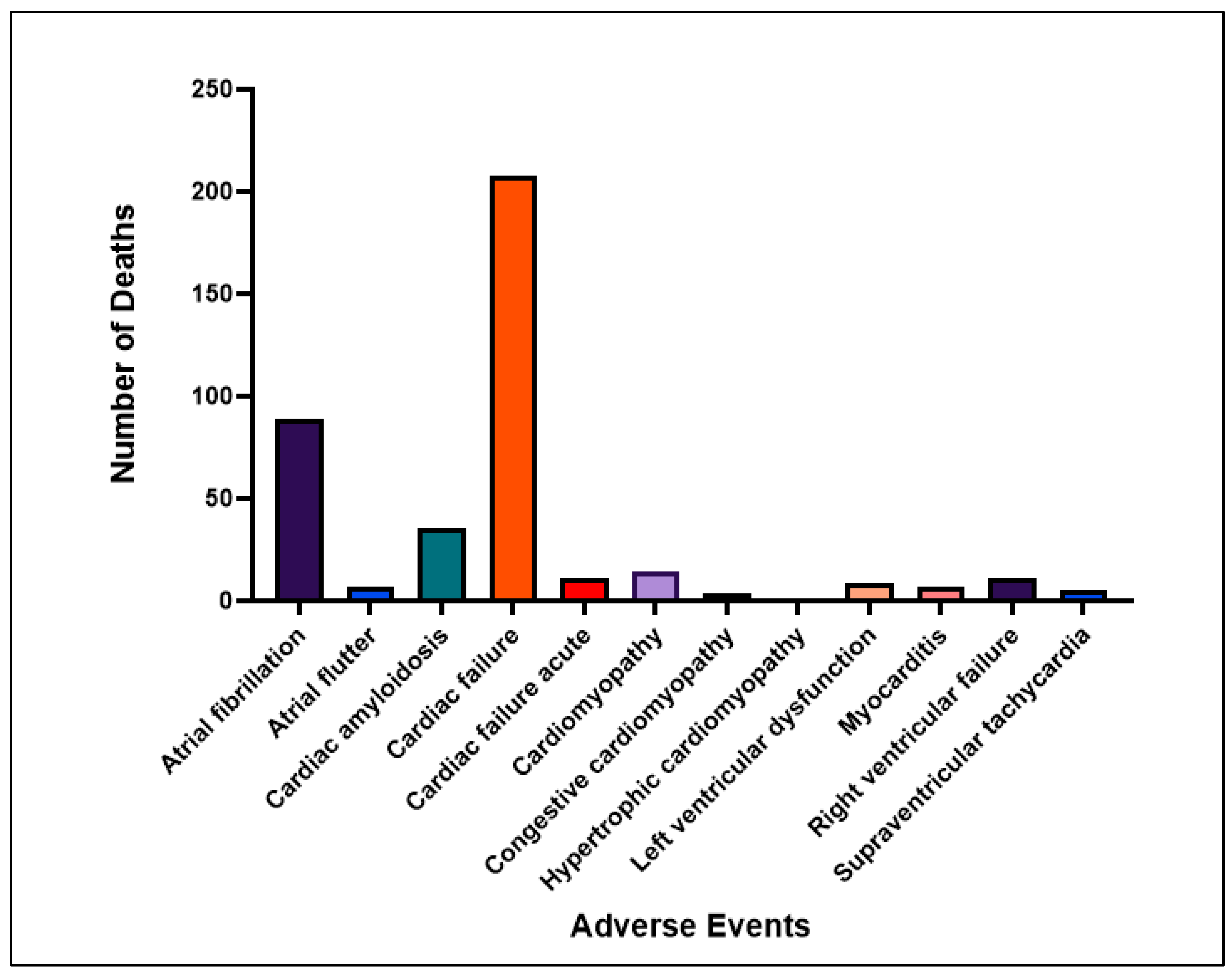

3.2. Clinical Severity and Mortality Outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the clinical impact of twelve cardiac AEs reported in association with bortezomib, including hospitalization rates, life-threatening classifications, and mortality outcomes. According to

Figure 2, Cardiac failure emerged as both the most common and most lethal AE, with 197 hospitalizations and 208 deaths, reflecting a case fatality rate of approximately 37.7%. This finding aligns with earlier reports describing cardiac failure as a frequent complication of proteasome inhibitors, especially in patients with comorbidities such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, or underlying structural heart abnormalities [

13,

19].

Atrial fibrillation also showed high prevalence, with 216 hospitalizations and 89 deaths, but a lower-case fatality rate (~8.7%), consistent with prior studies suggesting that atrial arrhythmias are common but often manageable with appropriate monitoring and supportive care [

18]. These findings are significant given that atrial fibrillation has previously been under-recognized in this population and may reflect direct cardiac remodeling or autonomic imbalance induced by bortezomib [

4,

8].

Cardiac amyloidosis, though reported less frequently (n = 80), demonstrated a disproportionately high mortality burden, with 36 deaths (27.5% mortality rate). However, this signal should be interpreted with caution, as AL amyloidosis is a primary disease indication for bortezomib rather than a drug-induced toxicity. Its inclusion among adverse events likely reflects confounding by indication rather than true cardiotoxicity. Nonetheless, patients with preexisting amyloid cardiomyopathy may remain particularly vulnerable to treatment-related cardiac decompensation due to their limited cardiac reserve and increased sensitivity to therapeutic stressors [

7,

14,

25]. To maintain clinical interpretability, amyloidosis-related Preferred Terms (PTs) should be excluded from the primary cardiotoxicity analysis or examined separately in a prespecified sensitivity analysis labeled as “indication signals.”

In addition, other rare but severe events like myocarditis (6 deaths from 57 reports) and acute cardiac failure (11 deaths from 48 reports) highlight the importance of monitoring for immune-related or inflammatory mechanisms during therapy [

5,

16,

17]. As shown in

Figure 2, even low-frequency AEs such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, right ventricular failure, and supraventricular tachycardia were associated with at least one fatality each, supporting the idea that infrequent events may still carry significant clinical risk in vulnerable patients.

Overall, this mortality profile highlights the need to prioritize both frequent and rare cardiac complications during bortezomib therapy, especially when treating elderly or comorbid patients.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes (hospitalizations, life-threatening events, deaths) for each cardiac AE linked to bortezomib.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes (hospitalizations, life-threatening events, deaths) for each cardiac AE linked to bortezomib.

| Adverse Event |

Hospitalization |

Life-threatening |

Death |

Other Outcomes |

| Atrial fibrillation |

216 |

32 |

89

|

192

|

| Atrial flutter |

39 |

9 |

7 |

13 |

| Cardiac amyloidosis |

7 |

6 |

36 |

31 |

| Cardiac failure |

197 |

45 |

208 |

104 |

| Cardiac failure acute |

24 |

5 |

11 |

6 |

| Cardiomyopathy |

24 |

6 |

14 |

53 |

| Congestive cardiomyopathy |

18 |

2 |

4 |

12 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

10 |

0 |

1 |

1

|

| Left ventricular dysfunction |

22 |

6 |

9 |

18 |

| Myocarditis |

20 |

6 |

6 |

25 |

| Right ventricular failure |

4 |

7 |

21

|

1

|

| Supraventricular tachycardia |

21 |

10 |

4 |

8 |

3.3. Suspected Attribution and Causality Patterns

To evaluate the likelihood of a causal link between bortezomib and each reported cardiac adverse event,

Table 3 categorizes suspect attribution as primary, secondary, or other. Events such as cardiomyopathy (68.0 percent) and acute cardiac failure (60.4 percent) had the highest rates of primary suspect designation, suggesting a closer association between bortezomib exposure and the onset of these conditions. Mechanistically, this observation aligns with prior studies showing that proteasome inhibition can impair protein turnover, increase oxidative stress, and induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis, processes that are central to the development of structural heart disease [

22,

23,

26].

In contrast, atrial fibrillation (41.4 percent) and cardiac failure (46.0 percent) displayed more distributed attribution patterns, often falling into the secondary suspect category. These patterns likely reflect a combination of drug effects and disease-related factors such as prior cardiovascular history, chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, or progression of multiple myeloma [

3,

19]. Such mixed attributions are common in oncology settings, where polypharmacy and overlapping toxicities complicate causal inference. Less common events, including atrial flutter and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, were frequently classified as secondary or “other,” which may reflect reporting biases, diagnostic uncertainty, or the influence of comorbidities rather than direct drug toxicity [

27].

From an analytical standpoint, it is important to note that restricting attribution to primary suspect reports offers greater signal specificity, whereas including secondary or other roles may introduce concomitant or interacting drugs into the analysis and thereby dilute the association. Additionally, our primary analyses relied on primary suspect reports, with sensitivity analyses that combined primary and secondary suspects. The choice of comparator also influences interpretation. While “all other drugs” provides a broad reference set, this approach risks therapeutic area confounding. Additional sensitivity analyses using myeloma therapeutics (excluding proteasome inhibitors) as comparators, and separate analyses excluding other proteasome inhibitors to test for class-specific effects, provide greater robustness and help clarify whether the observed signals are unique to bortezomib or reflect broader therapeutic trends.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical distribution of bortezomib-associated cardiac AEs by age, diagnosis, reporter country, and attribution type.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical distribution of bortezomib-associated cardiac AEs by age, diagnosis, reporter country, and attribution type.

| |

|

Cardiac Failure |

Atrial Fibrilation |

Atrial Flutter |

Cardiac Failure Acute |

Cardiomyopathy |

Congestive Cardiomyopathy |

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

Left Ventricular Dysfunction |

Myocarditis |

Right Ventricular Failure |

Supraventricular Tachycardia |

Cardiac Amyloidosis |

| Suspect Attribution |

# of Unique cases |

552 |

529 |

68 |

48 |

97 |

36 |

12 |

55 |

57 |

33 |

43 |

80 |

| Other |

61 (11.1%) |

89 (16.8%) |

12 (17.6%) |

2 (4.2%) |

6 (6.2%) |

1 (2.8%) |

1 (8.3%) |

6 (10.9%) |

1 (1.8%) |

4 (12.1%) |

2 (4.7%) |

5 (6.2%) |

| Primary Suspect |

237 (42.9%) |

219 (41.4%) |

22 (32.4%) |

29 (60.4%) |

66 (68.0%) |

18 (50.0%) |

5 (41.7%) |

28 (50.9%) |

37 (64.9%) |

16 (48.5%) |

23 (53.5%) |

39 (48.8%) |

| Secondary Suspect |

254 (46.0%) |

221 (41.4%) |

34 (50.0%) |

17 (35.4%) |

25 (25.8%) |

17 (47.2%) |

6 (50.0%) |

21 (38.18%) |

17 (29.8% |

13 (39.4%) |

18 (41.9%) |

36 (45.0%) |

| |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indication Subtype |

Amyloidosis |

99 (17.9%) |

17 (3.2%) |

4 (5.9%) |

3 (6.25%) |

2 (2.1%) |

1 (2.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

20 (25%) |

| Multiple myeloma |

68 (12.3%) |

112 (21.2%) |

17 (25.0%) |

6 (12.5%) |

31 (32.0%) |

4 (11.1%) |

2 (16.7%) |

7 (12.73%) |

3 (5.2%) |

2 (6.1%) |

17 (39.5%) |

10 (12.5%) |

| Plasma cell myeloma |

179 (32.4%) |

206 (38.9%) |

34 (50.0%) |

28 (58.33%) |

35 (36.1%) |

19 (52.8%) |

8 (66.7%) |

19 (34.55%) |

39 (67.2%) |

8 (24.2%) |

14 (32.6%) |

35 (43.8%) |

| Primary amyloidosis |

46 (8.33%) |

10 (1.9%) |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (6.25%) |

3 (3.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (12.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

7 (8.8%) |

| Other |

138 (25.0%) |

59 (11.2%) |

11 (16.2%) |

4 (8.33%) |

20 (20.6%) |

12 (33.3%) |

1 (8.3%) |

21 (38.18%) |

15 (24.6%) |

17 (51.5%) |

8 (18.6%) |

7 (8.8%) |

| Unknown |

22 (3.9%) |

125 (23.6%) |

2 (2.9%) |

4 (8.33%) |

6 (6.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (8.3%) |

8 (14.55%) |

1 (1.7%) |

2 (6.1%) |

4 (9.3%) |

1 (1.2%) |

| |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age Subtype |

<18 |

19 (3.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (1.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (10.91%) |

2 (3.5%) |

2 (6.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| 18-44 |

18 (3.3%) |

1 (0.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (2.1%) |

6 (6.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (7.27%) |

7 (12.3%) |

10 (30.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (1.2%) |

| 45-64 |

113 (20.5%) |

102 (19.3%) |

15 (22.1%) |

13 (27.1%) |

31 (32.0%) |

18 (50.0%) |

1 (8.3%) |

20 (36.36%) |

19 (33.3%) |

12 (36.4%) |

15 (34.9%) |

31 (38.8%) |

| 65+ |

230 (41.7%) |

262 (49.5%) |

33 (48.5%) |

23 (47.9%) |

26 (26.8%) |

12 (33.3%) |

11 (91.7%) |

13 (23.64%) |

21 (36.8%) |

4 (12.1%) |

13 (30.2%) |

26 (32.5%) |

| Unknown |

172 (31.2%) |

164 (31.0%) |

20 (29.4%) |

11 (22.9%) |

33 (34.0%) |

6 (16.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

12 (21.82%) |

8 (14.0%) |

5 (15.2%) |

15 (34.9%) |

22 (28.7%) |

| |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Reporter Country |

United States |

100 (18.1%) |

218 (41.2%) |

29 (42.6%) |

2 (4.17%) |

39 (40.2%) |

2 (5.6%) |

5 (41.7%) |

18 (32.73%) |

27 (47.4%) |

13 (39.4%) |

12 (27.9%) |

5 (6.25%) |

| France (FR) |

80 (14.5%) |

45 (8.5%) |

1 (1.5%) |

4 (8.33%) |

2 (2.1%) |

17 (47.2%) |

5 (41.7%) |

1 (1.82%) |

5 (8.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (2.3%) |

12 (15.0%) |

| Japan (JP) |

66 (12.0%) |

18 (3.4%) |

5 (5.9%) |

10 (20.83%) |

4 (4.1%) |

1 (2.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (6.1%) |

7 (16.3%) |

12 (15.0%) |

| Germany(DE) |

76 (13.8%) |

30 (5.7%) |

8 (11.8%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (2.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (3.64%) |

2 (3.5%) |

1 (3.05%) |

2 (4.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| United Kingdom (GB) |

11 (2.0%) |

45 (8.5%) |

6 (8.8%) |

3 (6.25%) |

1 (1.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (3.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (2.3%) |

9 (11.25%) |

| Other Countries |

215 (38.9%) |

164 (31.0%) |

20 (29.4%) |

29 (60.42%) |

3 (3.1%) |

1 (2.8%) |

1 (8.3%) |

34 (61.82%) |

21 (36.8%) |

17 (51.5%) |

16 (37.2%) |

39 (48.75%) |

| Unknown |

4 (0.7%) |

9 (1.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

46 (47.4%) |

15 (41.7%) |

1 (8.3%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (0.09%) |

3 (3.75%) |

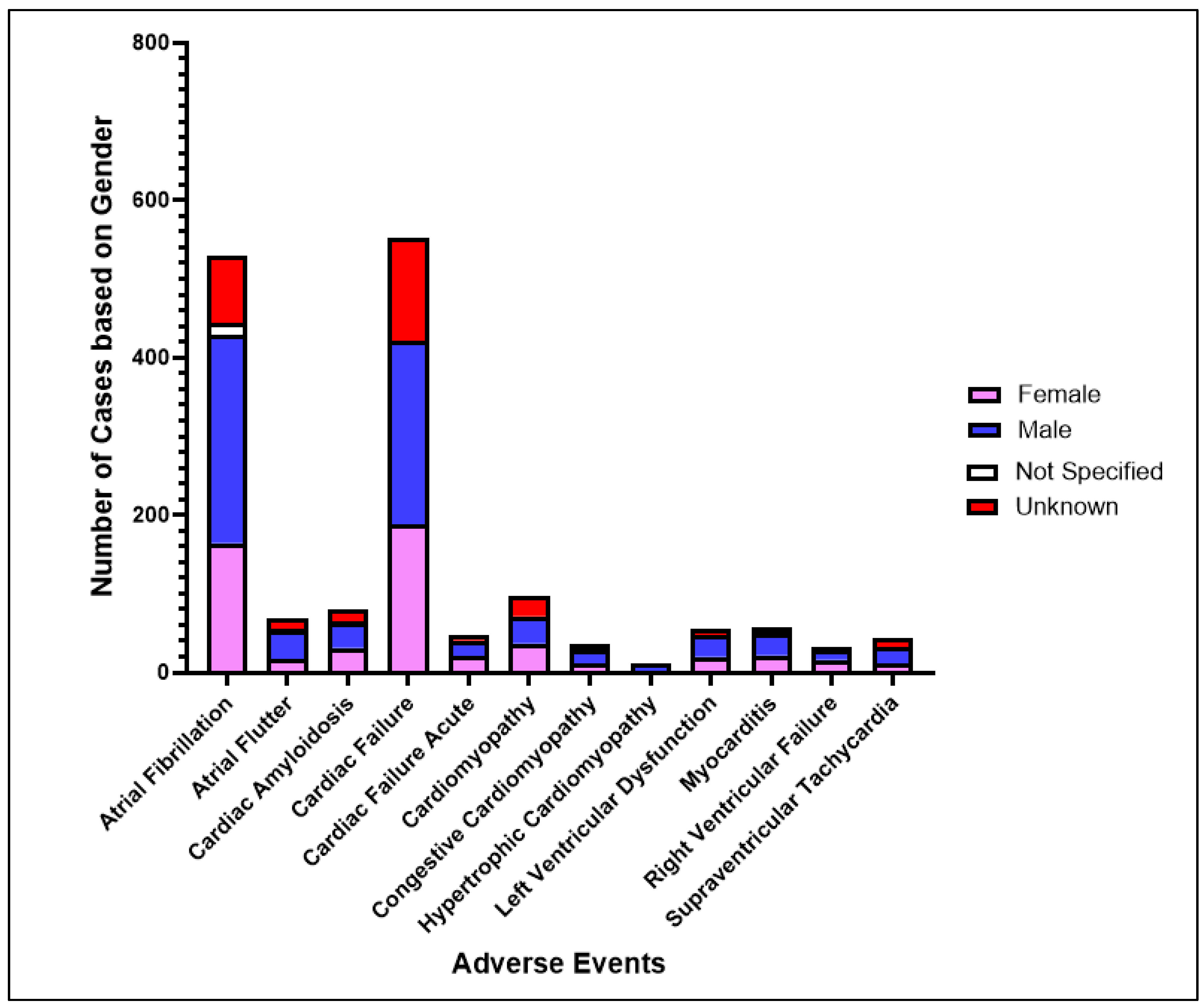

3.4. Demographic and Treatment Context

Demographic analysis showed that cardiac adverse events were more frequently reported in older adults and in males, a pattern that reflects established trends in cardiovascular vulnerability within oncology populations. Among the 552 reports of cardiac failure, 233 involved males, 188 involved females, and 131 lacked gender specification. Atrial fibrillation followed a similar distribution, with 265 reports in males compared to 164 in females. These observations suggest a possible sex-based predisposition, which may be influenced by differences in baseline cardiovascular health, the prevalence of hypertension, or hormonal modulation [

6,

9]. In contrast, cardiac amyloidosis was nearly equally distributed, with 32 reports in males and 31 in females. This balanced pattern is consistent with the biology of amyloidosis, which affects both sexes relatively equally and may remain undetected until late stages of the disease [

14].

The accuracy of sex-specific risk estimates is limited by the large proportion of missing demographic data, particularly in earlier FAERS submissions. This limitation emphasizes the importance of improving the quality of pharmacovigilance reporting, as more complete datasets are essential for clarifying whether these differences represent true biological effects or are shaped by reporting practices [

10].

Age was also a defining factor in the distribution of cardiac events. Patients aged 65 years or older accounted for 41.7 percent of cardiac failure reports and nearly half of atrial fibrillation reports. These findings are consistent with registry-based studies that demonstrate higher rates of cardiotoxic events among older patients who begin bortezomib therapy [

20,

21]. The increased vulnerability in this group likely reflects the combined impact of baseline frailty, a higher burden of preexisting cardiovascular disease, and diminished physiologic reserve. Given that bortezomib is often prescribed in older adults with plasma cell disorders, these findings underscore the importance of structured cardiovascular risk assessment prior to treatment and vigilant monitoring throughout therapy.

Bortezomib is rarely given alone. In most cases it is administered alongside other agents such as dexamethasone, lenalidomide or thalidomide, daratumumab, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, prednisone, doxorubicin, carfilzomib, or rituximab. Many of these drugs have their own cardiovascular effects, which complicates the attribution of risk to bortezomib alone. To address this challenge, future pharmacovigilance studies could benefit from summarizing the most frequent co-medications and conducting sensitivity analyses. These might include excluding cases where anthracyclines such as doxorubicin were co-reported or focusing specifically on cases where bortezomib was used as monotherapy. Such approaches would help disentangle drug-specific associations from the combined effects of multidrug regimens and provide a clearer picture of the cardiovascular risks attributable to bortezomib.

Figure 1.

Gender-Based Distribution of Cardiac Adverse Events Associated with Bortezomib(Female – Pink, Male – Blue, Not Specified – White, Unknown – Red).

Figure 1.

Gender-Based Distribution of Cardiac Adverse Events Associated with Bortezomib(Female – Pink, Male – Blue, Not Specified – White, Unknown – Red).

Figure 2.

Number of reported deaths per cardiac AE linked to bortezomib, highlighting severity beyond frequency.

Figure 2.

Number of reported deaths per cardiac AE linked to bortezomib, highlighting severity beyond frequency.

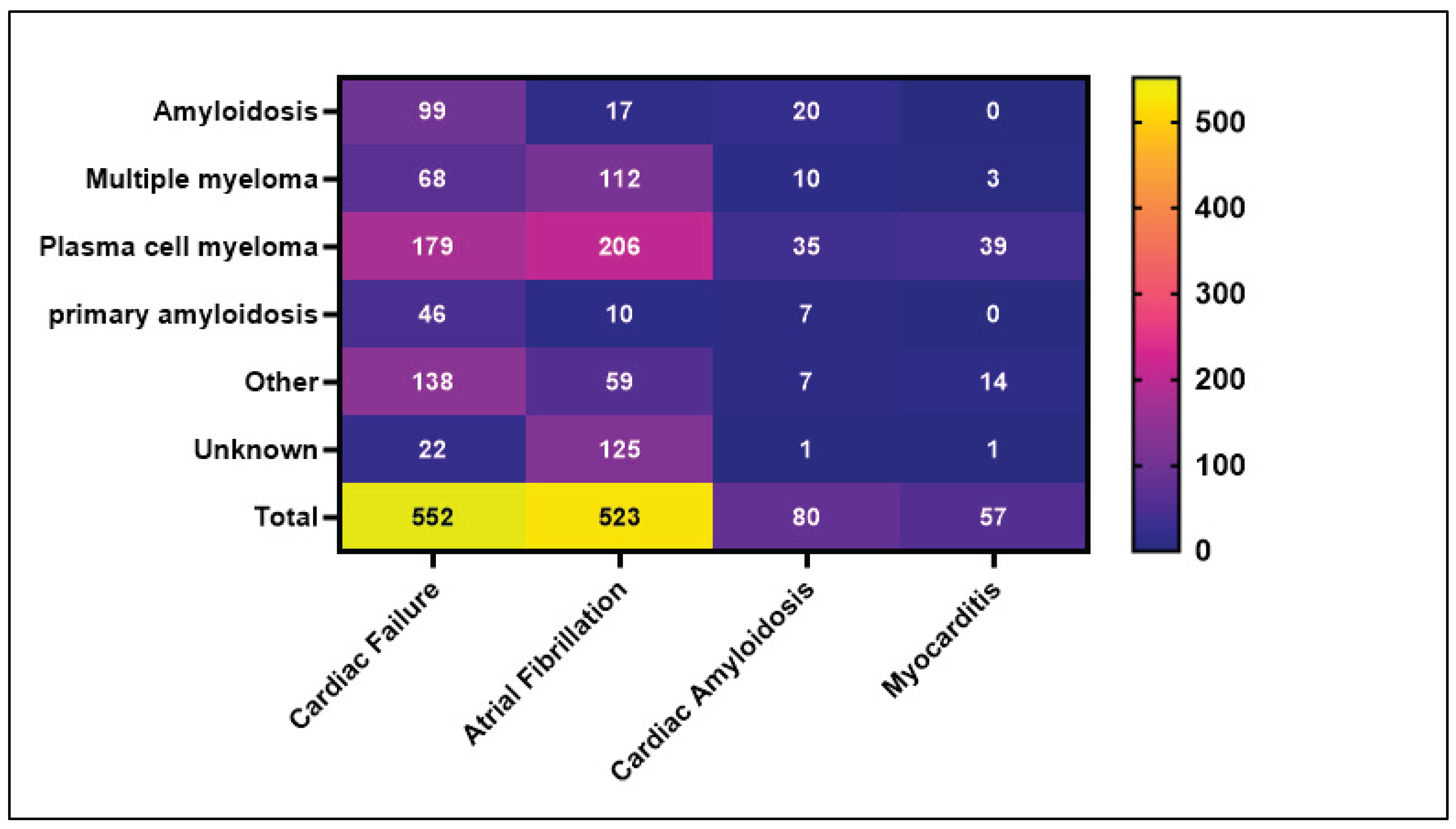

3.5. Disease-Specific Patterns and Subgroup Risk

Figure 3 presents a heatmap of four major cardiac AEs across clinical subgroups based on diagnosis (e.g., plasma cell myeloma, systemic amyloidosis). Cardiac failure and atrial fibrillation were present in patients with plasma cell myeloma (179 and 206 reports, respectively), while cardiac amyloidosis clustered heavily in amyloidosis patients (27 of 80 reports), illustrating disease-specific cardiotoxic risks.

These distribution patterns are clinically important. For example, patients with amyloidosis often present with underlying transthyretin or light chain deposition, which may predispose the heart to dysfunction under proteasome inhibition [

7,

14,

25]. In contrast, myocarditis, although rarer overall (58 reports), disproportionately affected plasma cell myeloma patients (39 reports), potentially reflecting immune dysregulation, infections, or off-target inflammatory responses in this population [

5,

16].

Furthermore, multiple myeloma, a condition known to involve high treatment burden and systemic inflammation, accounted for a substantial proportion of atrial fibrillation and cardiac failure cases. These results support the need for disease specific surveillance strategies and may influence decisions regarding drug selection, dose modification, and cardiac imaging [

13,

20].

4. Discussion

Our analysis identified a strong pharmacovigilance signal associating bortezomib with a spectrum of cardiac adverse events (AEs), including cardiac failure, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias. These observations contribute to the ongoing debate in cardio-oncology, where proteasome inhibitors remain essential in treating multiple myeloma (MM) and systemic amyloidosis but may also introduce cardiovascular concerns [

13,

19]. Because these data come from the FAERS Database, they should be viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than evidence of causation.

Mechanistically, several pathways could explain bortezomib’s cardiotoxic profile. Proteasome inhibition disrupts protein homeostasis, which in turn may trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial injury, and impaired cellular repair capacity [

4,

22,

23]. These mechanisms, described in cardiac literature, provide a biological explanation for the observed signals, but they remain speculative and require further experimental validation.

The signals were particularly common among older adults and patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease. These findings do not establish these conditions as risk factors, but they highlight plausible clinical contexts where reduced physiologic reserve, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired mitochondrial resilience may increase susceptibility to cardiac injury [

20,

21]. This interpretation aligns with real-world data showing that elderly MM patients often experience higher cardiovascular event rates soon after initiating bortezomib therapy.

Patterns of attribution also varied across AEs. Acute cardiac failure and cardiomyopathy were more frequently designated as primary suspect events, suggesting a closer link to drug exposure. In contrast, atrial fibrillation and congestive cardiomyopathy were more often reported as secondary suspects, likely reflecting the use of co-medications, underlying disease burden, and comorbidities common in oncology populations [

3,

9]. Rare events such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and supraventricular tachycardia, though rare, were associated with severe outcomes including death. These findings highlight prior pharmacovigilance literature, which shows that even low-prevalence signals can carry high clinical impact when they affect vulnerable cardiac substrates [

13,

17].

Sex-based patterns were also observed. Males were more frequently represented in cases of atrial fibrillation and cardiac failure, although these findings are limited by missing demographic information in older FAERS records. Nonetheless, this trend aligns with prior reports suggesting that hormonal and behavioral differences, such as hypertension prevalence and tobacco use, may shape cardiovascular outcomes in patients receiving bortezomib [

6].

Disease-specific subgroup patterns further support the complexity of these observations. Among MM patients, atrial fibrillation and cardiac failure were particularly common, likely reflecting the combined burden of anemia, systemic inflammation, and treatment-related stress [

3,

20]. In systemic amyloidosis, cardiac amyloidosis reports carried disproportionately high mortality. These events should be regarded as confounding by indication rather than evidence of drug-induced toxicity, since amyloidosis is both the underlying disease substrate and a treatment indication. Nevertheless, the high fatality rate emphasizes the extreme vulnerability of this patient population and the importance of close monitoring [

7,

14,

25].

In summary, our findings highlight a set of hypothesis-generating signals that support further investigation. Bortezomib’s potential cardiovascular effects may involve mitochondrial dysfunction and endothelial injury, though confirmatory studies are needed. While causality cannot be inferred from FAERS data, the results suggest that older adults and patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease represent plausible contexts of heightened vulnerability. Future prospective studies and mechanistic investigations are essential to clarify these patterns and to guide evidence-based risk mitigation strategies.

5. Conclusion

This pharmacovigilance analysis provides real-world evidence that bortezomib is associated with a spectrum of serious cardiac AEs, including cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, and other arrhythmias. The elevated reporting odds ratios, particularly in older adults and those with underlying plasma cell disorders, highlight the need for personalized cardiovascular surveillance. Mechanistically, these AEs align with known pathways of proteasome inhibitor-induced toxicity, including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired protein clearance. Clinicians should consider early cardiac risk stratification, baseline imaging, and routine monitoring when prescribing bortezomib, especially for high-risk populations such as patients with AL amyloidosis or advanced age.

6. Study Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations stemming from the nature of spontaneous reporting data in the FAERS database. First, under- and over-reporting bias may affect signal reliability, as reports are submitted voluntarily and influenced by factors such as media attention, litigation, and the time elapsed since drug approval. Second, missing or incomplete information in start and event dates can obscure temporal relationships between drug exposure and the onset of adverse events. Third, the absence of reliable exposure denominators prevents the estimation of true incidence or comparative risk. Fourth, co-medication and indication confounding are likely, particularly in oncology patients who often receive complex treatment regimens. Fifth, duplicate, incomplete, or misclassified reports may persist despite rigorous deduplication and data-cleaning efforts. Sixth, variability in data entry practices, MedDRA coding, and reporter expertise can introduce inconsistencies that affect signal interpretation. Seventh, because FAERS is a dynamic system that undergoes continuous updates, the dataset analyzed from May 13, 2003, to May 19, 2025, may change as new reports are submitted or revised, meaning results could shift even after a single day. Finally, disproportionality analyses are inherently non-causal and should be regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. These limitations should be carefully considered when analyzing the results, as they emphasize the need for complementary epidemiological and mechanistic studies to verify potential safety signals identified through FAERS.

References

- Richardson, P.G., et al., A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med, 2003. 348(26): p. 2609-17. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P., et al., Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Oncol, 2011. 12(5): p. 431-40. [CrossRef]

- Kistler, K.D., et al., Incidence and Risk of Cardiac Events in Patients With Previously Treated Multiple Myeloma Versus Matched Patients Without Multiple Myeloma: An Observational, Retrospective, Cohort Study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 2017. 17(2): p. 89-96 e3. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.H., et al., Reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the apoptotic response to Bortezomib, a novel proteasome inhibitor, in human H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(36): p. 33714-23. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K. and H. Liu, The proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, induces prostate cancer cell death by suppressing the expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen, as well as androgen receptor. Int J Oncol, 2019. 54(4): p. 1357-1366. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M., et al., Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives. Circ Res, 2016. 118(8): p. 1273-93.

- Christoffersen, M., et al., Transthyretin Tetramer Destabilization and Increased Mortality in the General Population. JAMA Cardiol, 2025. 10(2): p. 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J., et al., Vascular Toxicities of Cancer Therapies: The Old and the New--An Evolving Avenue. Circulation, 2016. 133(13): p. 1272-89.

- Gandolfi, S., et al., The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2017. 36(4): p. 561-584. [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.A., et al., Sociodemographic Characteristics of Adverse Event Reporting in the USA: An Ecologic Study. Drug Saf, 2024. 47(4): p. 377-387. [CrossRef]

- Sakaeda, T., et al., Data mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Med Sci, 2013. 10(7): p. 796-803. [CrossRef]

- Bate, A. and S.J. Evans, Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2009. 18(6): p. 427-36. [CrossRef]

- Chari, A., et al., Analysis of carfilzomib cardiovascular safety profile across relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma clinical trials. Blood Adv, 2018. 2(13): p. 1633-1644. [CrossRef]

- Movila, D.E., et al., Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Narrative Review of Diagnostic Advances and Emerging Therapies. Biomedicines, 2025. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J., et al., Current Therapies and Future Horizons in Cardiac Amyloidosis Treatment. Curr Heart Fail Rep, 2024. 21(4): p. 305-321. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al., Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors in Multiple Myeloma Therapy. Curr Probl Cardiol, 2023. 48(3): p. 101536. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C., et al., Infection-related adverse events comparison of bortezomib, carfilzomib and ixazomib: a pharmacovigilance study based on FAERS. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2025: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., et al., Coexisting atrial fibrillation and cancer: time trends and associations with mortality in a nationwide Dutch study. Eur Heart J, 2024. 45(25): p. 2201-2213. [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulos, G., et al., Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors: Underlying Mechanisms and Management Strategies: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol, 2023. 5(1): p. 1-21.

- Armenian, S.H., C. Lacchetti, and D. Lenihan, Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Summary. J Oncol Pract, 2017. 13(4): p. 270-275. [CrossRef]

- Jang, B., et al., Real-world incidence and risk factors of bortezomib-related cardiovascular adverse events in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Res, 2024. 59(1): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.K., et al., A gene expression signature distinguishes innate response and resistance to proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J, 2017. 7(6): p. e581. [CrossRef]

- Ruckrich, T., et al., Characterization of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in bortezomib-adapted cells. Leukemia, 2009. 23(6): p. 1098-105. [CrossRef]

- Curigliano, G., et al., Management of cardiac disease in cancer patients throughout oncological treatment: ESMO consensus recommendations. Ann Oncol, 2020. 31(2): p. 171-190. [CrossRef]

- Caponetti, A.G., et al., Screening approaches to cardiac amyloidosis in different clinical settings: Current practice and future perspectives. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2023. 10: p. 1146725. [CrossRef]

- Sundaravel, S.H., et al., Bortezomib-Induced Reversible Cardiomyopathy: Recovered With Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy. Cureus, 2021. 13(12): p. e20295. [CrossRef]

- Hedhli, N. and C. Depre, Proteasome inhibitors and cardiac cell growth. Cardiovasc Res, 2010. 85(2): p. 321-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).