Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Study Area

1.2. The Shoreline Changes

2. Methods

2.1. Digital Shoreline Analysis System (Dsas)

2.2. Litpack Model

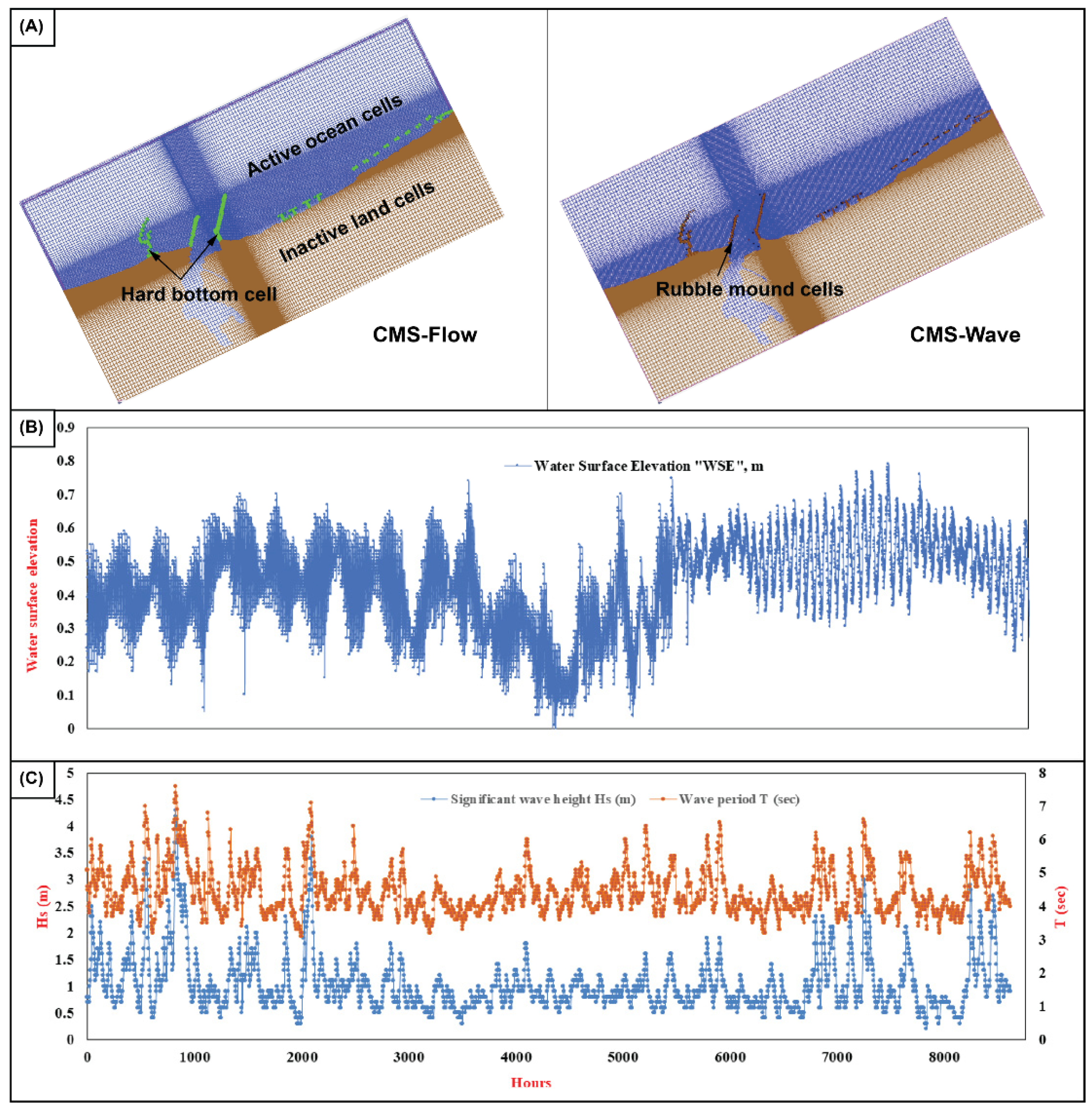

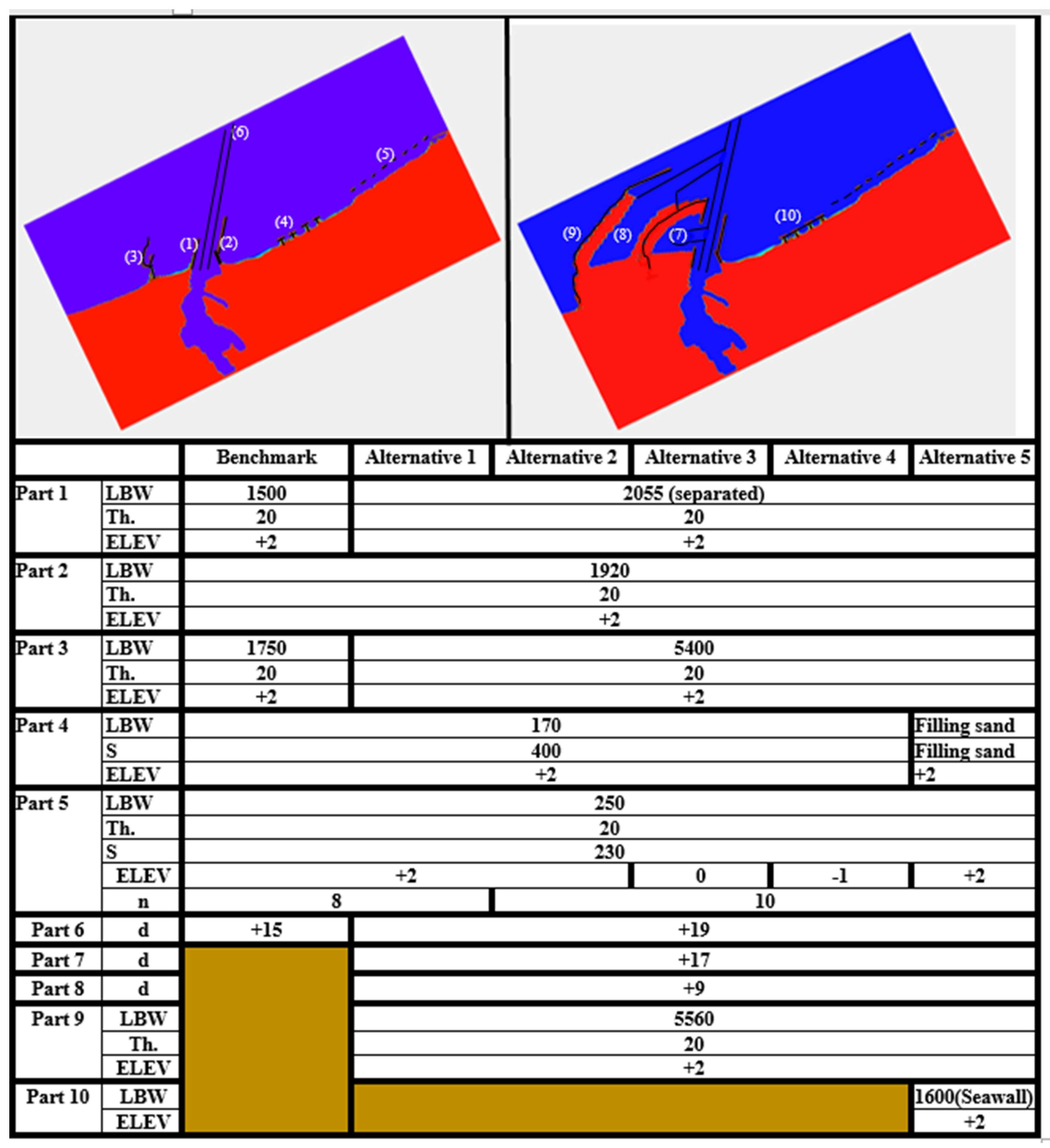

2.3. CMS Model

3. Results and Discussions

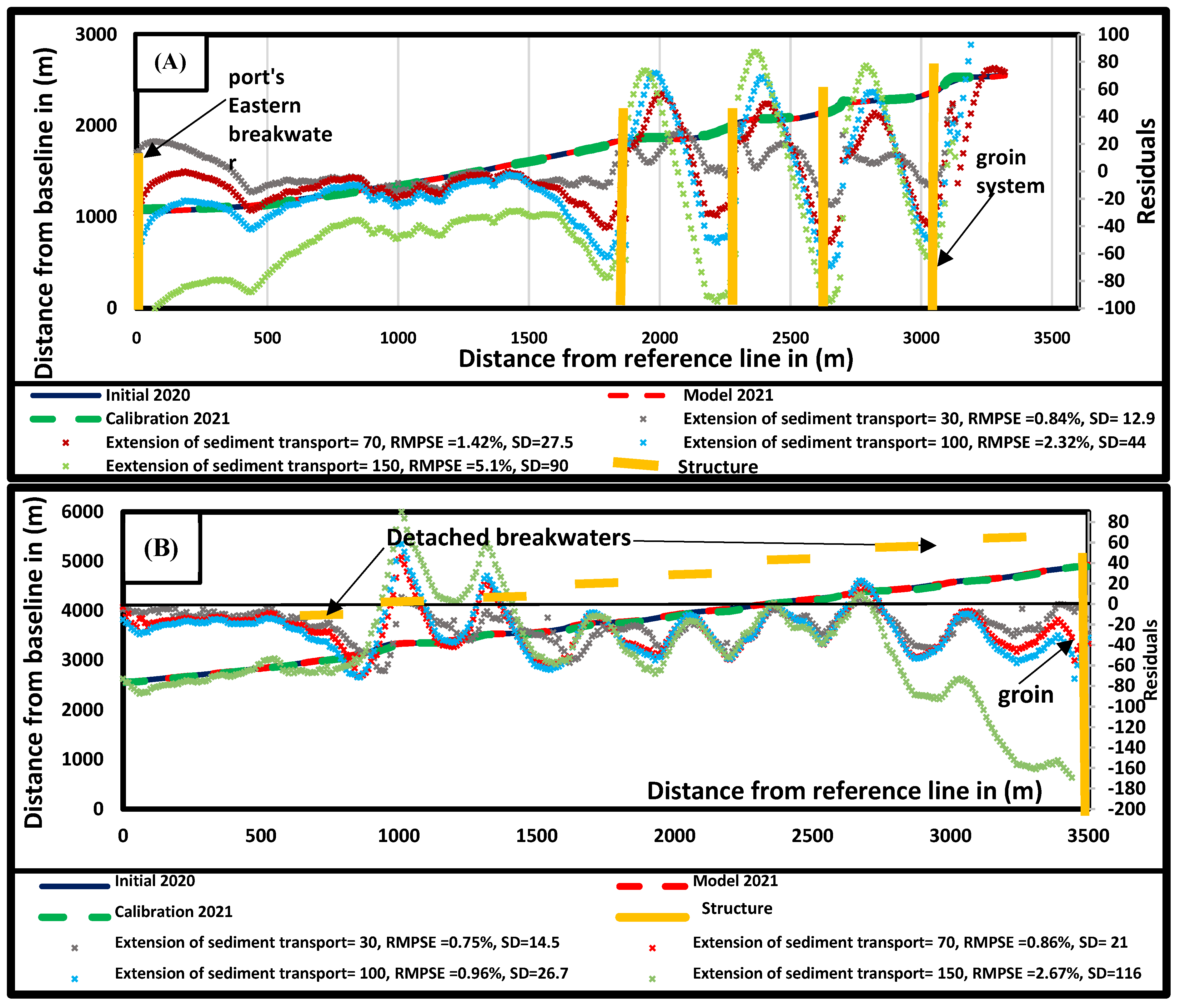

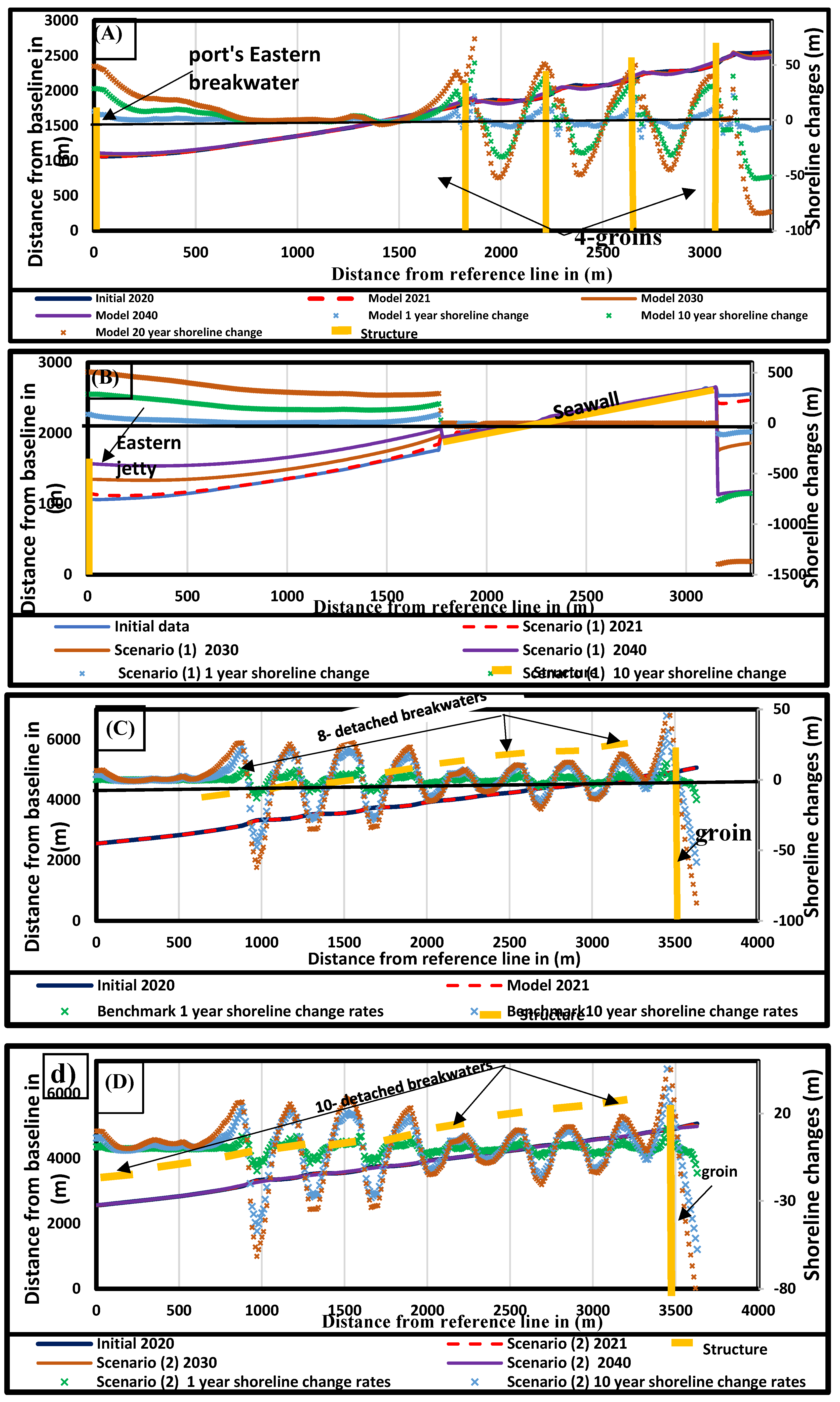

3.1. Litpack

3.2. CMS Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Abd El-Hamid, H.T., 2020. Geospatial analyses for assessing the driving forces of land use/land cover dynamics around the Nile Delta Branches, Egypt. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, 48(12), pp.1661-1674.

- Abd-Elhamid, H.F., Zeleňáková, M., Barańczuk, J., Gergelova, M.B. and Mahdy, M., 2023. Historical trend analysis and forecasting of shoreline change at the Nile Delta using RS data and GIS with the DSAS tool. Remote Sensing, 15(7), p.1737. [CrossRef]

- Abo Zed, B.I, 2007. Effects of waves and currents on the siltation problem of Damietta harbor, Nile Delta coast, Egypt, Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 8, 33–47.

- Abou Samra, R.M., El-Gammal, M., Al-Mutairi, N., Alsahli, M.M. and Ibrahim, M.S., 2021. GIS-based approach to estimate sea level rise impacts on Damietta coast, Egypt. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 14, pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Athira, C.A. and Lekshmi Devi C A., 2023. Assessment of Longshore Sediment Transport Using LITPACK.

- Aziz, K.M.A., 2024. Quantitative Monitoring of Coastal Erosion and Changes Using Remote Sensing in a Mediterranean Delta. Civil Engineering Journal, 10(6), pp.1842-1862.

- Bacino, G.L., Dragani, W.C. and Codignotto, J.O., 2019. Changes in wave climate and its impact on the coastal erosion in Samborombón Bay, Río de la Plata estuary, Argentina. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 219, 71-80. [CrossRef]

- Balah M. I., Elshinnawy I., Tolba E. R. and Youness M., 2012. Impact of Coastal Erosion and Sedimentation along the Northern Coast of Sinai Peninsula, Case Study: AL-ARISH Harbor Coast. Port-Said Engineering Research Journal, 16(1), pp.118-125.

- Bazzichetto, M., Sperandii, M.G., Malavasi, M., Carranza, M.L. and Acosta, A.T.R., 2020. Disentangling the effect of coastal erosion and accretion on plant communities of Mediterranean dune ecosystems. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 241, 106758. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H. and Suh, K.D., 2016. Effect of sea level rise on nearshore significant waves and coastal structures. Ocean Engineering, 114, 280-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.oceaneng.2016.01.026.

- Damietta Port Authority, 2023. Annual Operational and Financial Report. Damietta Port Authority, Damietta, Egypt.

- Darwish, K.S., 2024. Monitoring Coastline Dynamics Using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems: A Review of Global Trends. Catrina: The International Journal of Environmental Sciences, pp.1-23.

- Deabes, E.A.E.H.M., 2010. Sedimentation processes at the navigation channel of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) port, Nile Delta, Egypt. International Journal of Geosciences, 1(1), pp.14-20.

- Deng, B., Wu, H., Yang, S. and Zhang, J., 2017. Longshore suspended sediment transport and its implications for submarine erosion off the Yangtze River Estuary. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 190, pp.1-10. [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, K. M., and Frihy, O. E., 2010. Automated techniques for quantification of beach change rates using Landsat series along the North-eastern Nile Delta, Egypt. In Journal of Oceanography and Marine Science 1(2).

- Dewidar, K., Bayoumi, S., 2021. Forecasting shoreline changes along the Egyptian Nile Delta coast using Landsat image series and Geographic Information System. Environ Monit Assess 193, 429. [CrossRef]

- Eelsalu, M., Montoya, R.D., Aramburo, D., Osorio, A.F. and Soomere, T., 2024. Spatial and temporal variability of wave energy resource in the eastern Pacific from Panama to the Drake passage. Renewable Energy, 224, 120180. [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H. M., and Taha, M. M. N., 2022. Monitoring Coastal Changes and Assessing Protection Structures at the Damietta Promontory, Nile Delta, Egypt, to Secure Sustainability in the Context of Climate Changes. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(22). [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H. M., El-Kafrawy, S. B., and Taha, M. M. N., 2014. Monitoring Coastal Changes along Damietta Promontory and the Barrier Beach toward Port Said East of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Journal of Coastal Research, 297, 993–1005. [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M., 1994. Severe coastal damage along Ras El-Bar shoreline, north of the Nile Delta: An effect of the construction of the detached breakwater system. Journal of Geology, Egypt 38, 793–812.

- El-Asmar, H.M., 2002. Short term coastal changes along Damietta-port Said coast northeast of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Journal of Coastal Research 18, 433–441.

- El-Asmar, H.M., Felfla, M.Sh., ElKotby, M.R., El-Kafrawy, S.B., Naguib, D.M., 2025a. Multi-Decadal shoreline dynamics of Ras El-Bar, Nile Delta: Unraveling human interventions and coastal resilience. Scientific African e02937. [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M., Felfla, M.Sh., Ragab, M.T., Naguib, D.M., El-Kafrawy, S.B., 2025b. New beach geomorphic features associated with a temporal climate storm event, coinciding with the February 6, 2023, little tsunami, Ras El-Bar, Nile Delta coast, Egypt. Geoscience Letters 12. [CrossRef]

- El-Asmar, H.M., Taha, M.M. and El-Sorogy, A.S., 2016. Morphodynamic changes as an impact of human intervention at the Ras El-Bar-Damietta Harbor coast, NW Damietta promontory, Nile Delta, Egypt. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 124, pp.323-339.

- El-Asmar, H.M., White, K., 2002. Changes in coastal sediment transport processes due to construction of New Damietta Harbour, Nile Delta, Egypt. Coastal Engineering 46, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- ElKotby, M. R., Sarhan, T. A., and El-Gamal, M., 2023. Assessment of human interventions presence and their impact on shoreline changes along Nile delta, Egypt. Oceanologia, 65(4), 595–611. [CrossRef]

- ElKotby, M.R., Sarhan, T.A., El-Gamal, M. and Masria, A., 2024a. Impact evaluation of development plans in the Egyptian harbors on morphological changes using numerical simulation (case study: Damietta harbor, northeastern coast of Egypt). Remote Sens. Appl.: Soc. Environ., p.101301. [CrossRef]

- ElKotby, M.R., Sarhan, T.A., El-Gamal, M. and Masria, A., 2024b. Evaluation of coastal risks to Sea level rise: Case study of Nile Delta Coast. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 78, p.103791. [CrossRef]

- Elnabwy, M.T., Elbeltagi, E., El Banna, M.M., Alshahri, A.H., Hu, J.W., Choi, B.G., Kwon, Y.H. and Kaloop, M.R., 2024. Harbor Sedimentation Management Using Numerical Modeling and Exploratory Data Analysis. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2024(1), p.1209460.

- El-Zeiny, A., Gad, A.-A., El-Gammal, M., and Ibrahim, M., 2016. Space-borne technology for monitoring temporal changes along Damietta shoreline, Northern Egypt. In International Journal of Advanced Research 4(1). http://glovis.usgs.gov/.

- Esmail, M., Mahmod, W., and Fath, H., 2018. Influence of Coastal Measures on Shoreline Kinematics Along Damietta coast Using Geospatial Tools. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., 151(1), p.012027. [CrossRef]

- Frihy, O.E. and Stanley, J.D., 2023. The modern Nile delta continental shelf, with an evolving record of relict deposits displaced and altered by sediment dynamics. Geographies, 3(3), pp.416-445.

- Frihy, O.E., Abd El Moniem, A.B. and Hassan, M.S., 2002. Sedimentation processes at the navigation channel of the Damietta Harbour on the Northeastern Nile Delta coast of Egypt. Journal of Coastal Research, pp.459-469.

- Hendriyono, W., Wibowo, M., Al Hakim, B. and Istiyanto, D.C., 2015. Modeling of sediment transport affecting the coastline changes due to infrastructures in Batang-Central Java. Procedia Earth and Planetary Science, 14, pp.166-178.

- Jerin Joe, R.J., Pitchaimani, V.S., Mirra, T.N.S. and Karuppannan, S., 2025. Shoreline dynamics and anthropogenic influences on coastal erosion: A multi-temporal analysis for sustainable shoreline management along a southwest coastal district of India. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 27, p.100744. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A. M., Soliman, M. R., and Yassin, A. A., 2017. Assessment of a combination between hard structures and sand nourishment eastern of Damietta harbor using numerical modeling. ALEX ENG J., 56(4), 545–555. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhang, C., Cai, Y., Xie, M., Qi, H. and Wang, Y., 2021. Wave dissipation and sediment transport patterns during shoreface nourishment towards equilibrium. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 9(5), 535. [CrossRef]

- Marks, D., Middleton, C. and Pratomlek, O., 2025. Precarity between a megacity and coastal erosion: A political economy of (un) managed retreat pathways in Thailand's peri-urban Khun Samut Chin. Ocean & Coastal Management, 270, 107919. [CrossRef]

- Masria, A., El-Adawy, A. and Eltarabily, M.G., 2021. Simulating mitigation scenarios for natural and artificial inlets closure through validated morphodynamic models. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., 47, p.101991. [CrossRef]

- Masria, A.A., Negm, A.M., Iskander, M.M., Saavedra, O.C., 2013. Hydrodynamic modeling of outlet stability case study Rosetta promontory in Nile delta. Water Science 27, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Moghazy, N.H., Soliman, A. and ELTahan, M., 2024. Effect of Human Interventions on Hydro-dynamics of Sidi-Abdel Rahman Bay “North Western Coast of Egypt”.

- Nakamura, R., Ohizumi, K., Ishibashi, K., Katayama, D. and Aoki, Y., 2024. Dynamics of beach scarp formation behind detached breakwaters. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 298, 108651. [CrossRef]

- Nassar, K., Mahmod, W. E., Masria, A., Fath, H., and Nadaoka, K., 2018. Numerical simulation of shoreline responses in the vicinity of the western artificial inlet of the Bardawil Lagoon, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. Appl. Ocean Res., 74, 87–101. [CrossRef]

- Nassar, K., Masria, A., Mahmod, W. E., Negm, A., and Fath, H., 2019. Hydro-morphological modeling to characterize the adequacy of jetties and subsidiary alternatives in sedimentary stock rationalization within tidal inlets of marine lagoons. Appl. Ocean Res., 84, 92–110. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-M., Van, D.D., Duy, T.L., Pham, N.T., Dang, T.D., Tanim, A.H., Wright, D., Thanh, P.N., Anh, D.T., 2022. The influence of crest width and working states on wave transmission of Pile–Rock breakwaters in the coastal Mekong Delta. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, 1762. [CrossRef]

- Pareta, K., 2024. 1D-2D hydrodynamic and sediment transport modelling using MIKE models. Discover Water 4. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.T.M., 2025. The use of remote sensing techniques in the observation and evaluation of sediments movement in the marine belt environment of Damietta Harbor. Unpublished M.Sc. thesis, Damietta University, Damietta, Egypt.

- Reed, C.W., Brown, M.E., Sánchez, A., Wu, W., Buttolph, A.M., 2011. The Coastal Modeling System Flow Model (CMS-Flow): past and present. Journal of Coastal Research 59, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martín, R., Valdemoro, H. and Jiménez, J.A., 2025. Unveiling coastal adaptation demands: Exploring erosion-induced spatial imperatives on the Catalan Coast (NW Mediterranean). Landscape and Urban Planning, 263, 105450. [CrossRef]

- Saengsupavanich, C., Ariffin, E.H., Yun, L.S. and Pereira, D.A., 2022. Environmental impact of submerged and emerged breakwaters. Heliyon, 8 (12). [CrossRef]

- Saha, D., Rahman, Md.A., 2022. Simulation of longshore sediment transport and coastline changing along Kuakata Beach by mathematical modeling. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering 19, 15–31. [CrossRef]

- Sanhory, A., El-Tahan, M., Moghazy, H.M. and Reda, W., 2022. Natural and manmade impact on Rosetta eastern shoreline using satellite Image processing technique. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 61(8), pp.6247-6260.

- Sarhan, T., Mansour, N.A. and El-Gamal, M., 2020. Prediction of Shoreline Deformation around Multiple Hard Coastal Protection Systems. MEJ-Mansoura Engineering Journal, 45(3), pp.11-21. [CrossRef]

- Sharaan, M., Ibrahim, M.G., Iskander, M., Masria, A., Nadaoka, K., 2018. Analysis of sedimentation at the fishing harbor entrance: case study of El-Burullus, Egypt. Journal of Coastal Conservation 22, 1143–1156. [CrossRef]

- Sulisz, W., 1985. Wave reflection and transmission at permeable breakwaters of arbitrary cross-section. Coastal Engineering 9, 371–386. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B., Nederhoff, K. and Gallien, T.W., 2025. Quantifying compound coastal flooding effects in urban regions using a tightly coupled 1D–2D model explicitly resolving flood defense infrastructure. Coastal Engineering, 199, 104728.

- Thieler, E.R., Himmelstoss, E.A., Zichichi, J.L., Ergul, A., 2009. The Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) Version 4.0 - An ArcGIS extension for calculating shoreline change. Antarctica a Keystone in a Changing World. [CrossRef]

- White, K. and El-Asmar, H.M., 1999. Monitoring changing position of coastlines using Thematic Mapper imagery, an example from the Nile Delta. Geomorphology, 29(1-2), 93-105.

- Wu, W., Rosati, J.D., Brown, M.E., Demirbilek, Z., Li, H., Reed, C.W., Sanchez, A., Laboratory, C. and H., Program, C.I.R., 2014. Coastal Modeling System : Mathematical formulations and numerical methods. URL https://hdl.handle.net/11681/7361.

- Youssef, Y.M., Gemail, K.S., Atia, H.M. and Mahdy, M., 2024. Insight into land cover dynamics and water challenges under anthropogenic and climatic changes in the eastern Nile Delta: inference from remote sensing and GIS data. Science of the Total Environment, 913, p.169690. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).