1. Introduction

Coastal erosion is one of the most pressing challenges affecting coastal regions worldwide. This phenomenon, which involves the removal of sediment from beaches and dunes due to factors such as waves, currents, and sea-level rise, can have serious implications for biodiversity, coastal infrastructure, and human activities. Understanding erosion dynamics and implementing effective mitigation measures requires the use of modeling tools capable of simulating and predicting the complex interactions between different components of the coastal system, including the beach, dune, and submerged sandbars.

In the field of coastal simulations, the use of numerical and physical models has been widely recognized as fundamental for understanding these processes. Numerical models, such as the CS-Model [

1] offer the advantage of enabling rapid and comprehensive simulations of erosional processes, with the flexibility to explore a wide range of scenarios and parameters ([

2]). These models often simplify physical conditions to make computations feasible, but they may lose accuracy when representing highly dynamic and variable phenomena. To overcome these limitations, small-scale physical modeling conducted in laboratory environments allows for direct observation and measurement of the interactions between waves, sediment transport, and the morphological characteristics of the beach and dune ([

3]). This experimental approach provides valuable data to validate and refine numerical models, ensuring that simulations represent more accurately real coastal system conditions.

Various numerical models have been employed to simulate coastal erosion processes. For instance, the XBeach model ([

4]) is widely used for simulating wave dynamics and sediment transport in coastal environments, while MIKE21 ([

5]) has been applied to predict the effects of erosion and sediment transport in dynamic coastal areas. While these models provide robust results, the selection of the CS-Model for this study is based on its capability to efficiently and directly model interactions between the beach, dune, and submerged sandbar, which represent key aspects of coastal erosion dynamics [

6,

7]. The CS-Model, with its ability to integrate variables such as submerged bar volume and berm width, offers an effective framework for assessing coastal erosion mitigation and dune protection.

Although the CS-Model is a powerful tool for numerical modeling, it is crucial to balance the simulation results with physical laboratory experiments. The interaction between environmental conditions and erosional processes can vary significantly between models and real-world scenarios. Physical modeling permits for more detailed analysis, allowing direct observation of interactions and morphological changes over time ([

6]). Thus, the combination of these two complementary methods (numerical and physical) offers a more robust and complete assessment of solutions for coastal erosion.

Building on this integrated approach, this study aims to analyze coastal erosion dynamics through numerical and physical simulations, using the CS-Model in conjunction with a physical laboratory model. The interactions between the beach profile, dune, and submerged sandbar were evaluated under different conditions, including variations in water level, berm width, and the volume and shape of the submerged bar. Through this comparison, it was possible to validate numerical results and provide a deeper understanding of the variables influencing coastal erosion and dune protection strategies.

Based on this objective, the structure of the study is organized into four main sections.

Section 2 describes the methodologies adopted for both the numerical simulations with the CS-Model and the physical flume experiments, including the reference scenario and the definition of test cases.

Section 3 presents the results from both approaches, structured to allow direct comparison of the influence of water level, berm width, submerged bar volume, and bar shape.

Section 4 provides a discussion of the observed trends and differences between models. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions and implications for coastal erosion mitigation measures.

2. Materials and Methods

To meet the objectives of this study, a combined methodology was adopted, integrating both numerical and physical modeling techniques. The numerical component relies on the CS-Model, described in

Section 2.1, while the physical experiments were conducted in a laboratory flume, as detailed in

Section 2.2. A reference scenario common to both models was defined (

Section 2.3), followed by the definition of test scenarios used to assess morphological changes under different conditions (

Section 2.4).

2.1. CS-Model

The CS-Model is a cross-shore numerical model developed to simulate sand transport and morphological evolution over medium-term timescales. While a detailed description is available in [

1], this section provides a summary of its structure and key processes. The model simulates sand movement along the cross-shore profile and the resulting profile response over periods of up to approximately ten years, considering the main medium-term cross-shore processes: dune erosion and overtopping, wind-driven sand transport, and sediment exchanges between the submerged bar and the beach berm. Each of these processes is represented by a specific module integrated into the CS-Model, containing algorithms based on physical principles and validated by laboratory and field data [

1].

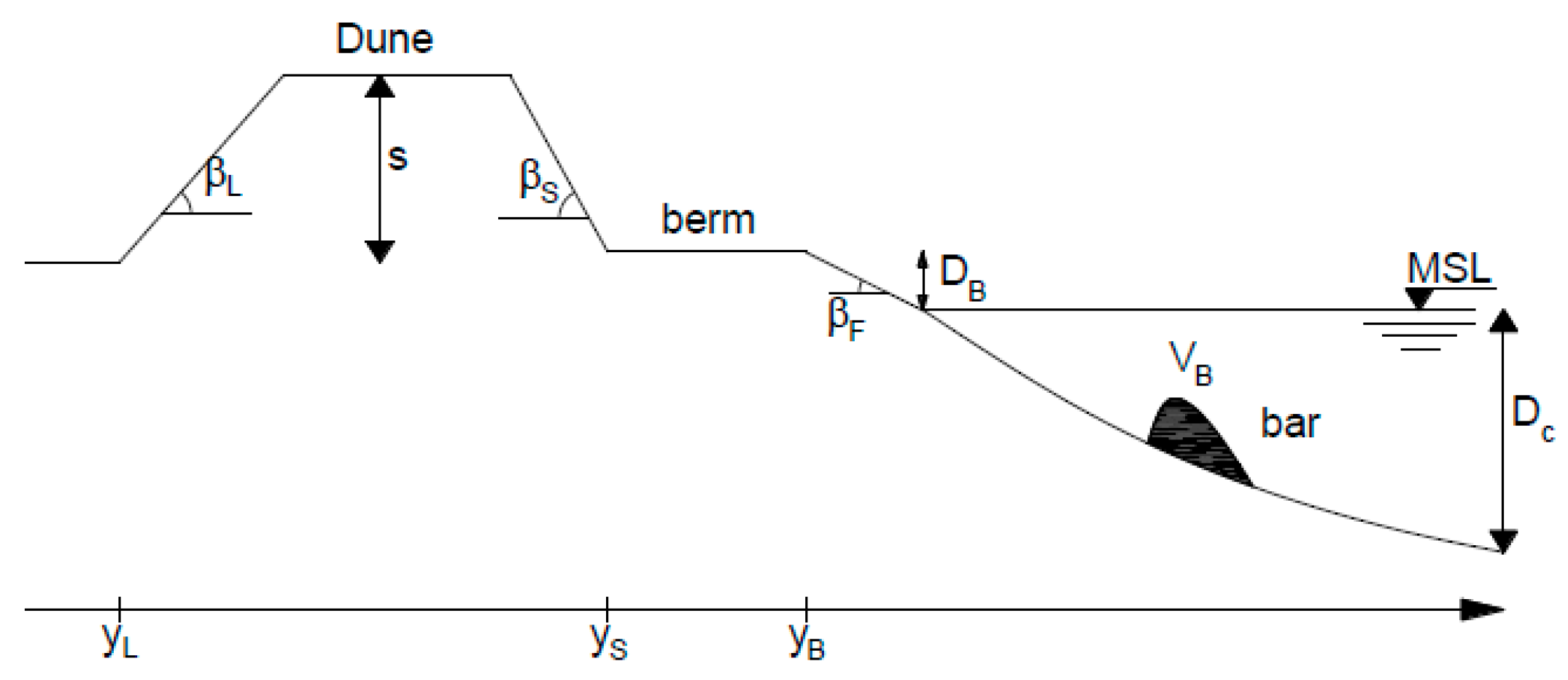

To model the profile response over time, sand volume conservation equations are used and solved alongside sediment transport equations to describe the evolution of the main morphological features of the cross-shore profile. These morphological parameters represent the cross-shore profile and include dune height (S), the location of the dune toe on the landward and seaward sides (Y

L and Y

S, respectively), the location of the berm crest (Y

B), and the volume of the submerged bar (V

B), as illustrated in

Figure 1. The angles βL and βS correspond to the slopes of the dune face on the landward and seaward sides, respectively, while βF represents the beach slope (these parameters are considered constant throughout the simulations). D

B and D

C denote berm height and closure depth, respectively, and MSL represents Mean Sea Level.

Sediment movement along the profile, which alters its geometry, is commonly attributed to wave and wind action, and is influenced by water levels. These changes, which represent the profile’s response, are determined geometrically to maintain mass balance, although the fundamental parameters vary over time.

The CS-Model consists of several integrated modules: two modules for calculating aerial material exchange processes (dune erosion and overtopping, and aeolian sediment transport) and one module for calculating underwater material exchange (material exchange between the bar and the berm, based on bar theory). A brief explanation of dune erosion and overtopping processes is presented.

The determination of dune erosion is carried out through an analytical model proposed by [

8], which is based on the studies of [

9] and [

10] on dune erosion. In this model, the eroded volume of the dune is considered to be proportional to the wave impact force hitting its face.

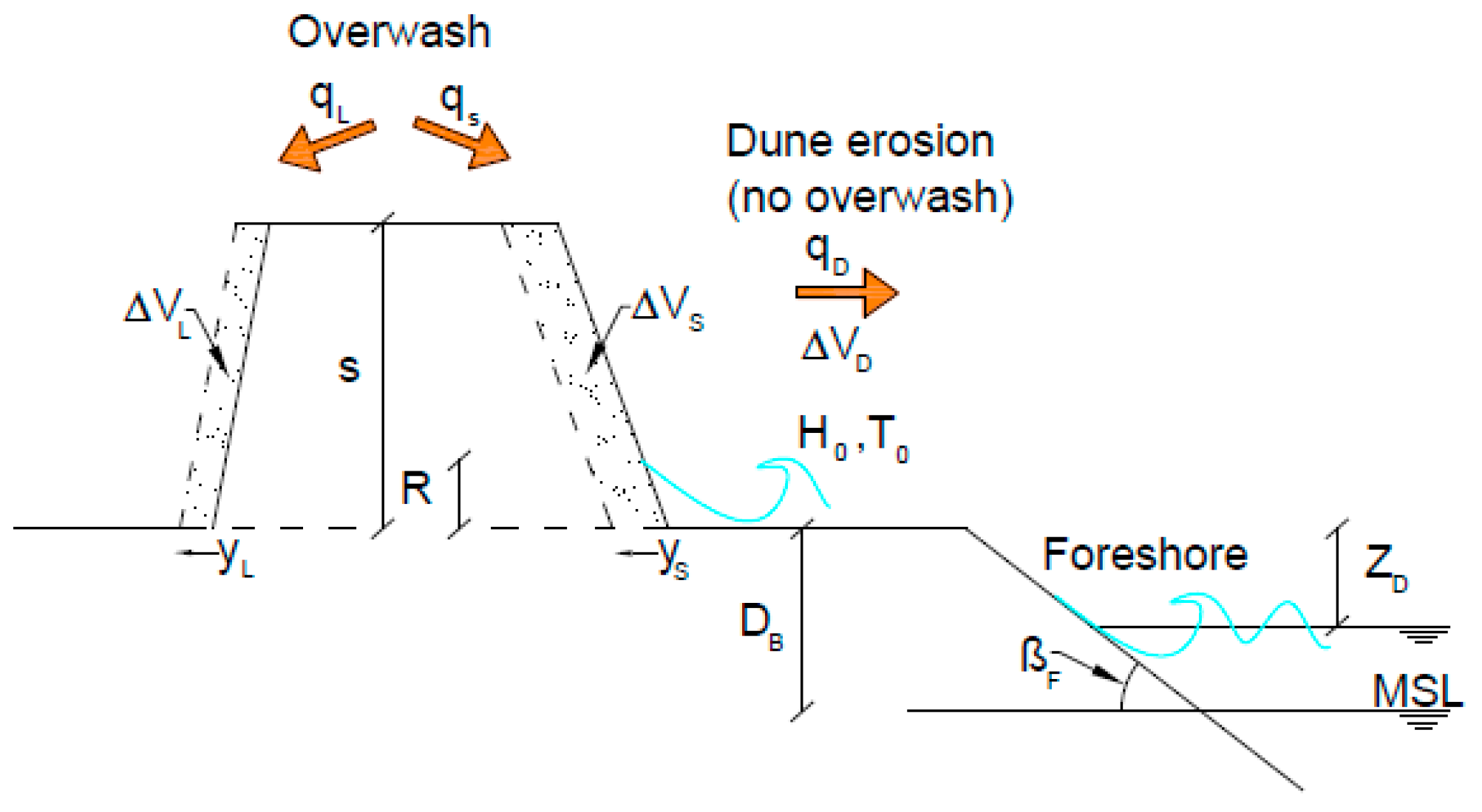

To illustrate the evolution of the profile, a storm impact is considered as an example. If the waves, along with the water level, generate sufficient runup (R), meaning that the wave runup exceeds the base level of the dune, the dune will lose volume (∆V

D) and supply sand to the beach berm (Equation 1). As a consequence of this erosion, the dune's base shifts inland, and Y

S decreases, assuming a constant dune slope.

In Equation 1, ∆t represents the time interval of the simulation, Z

D indicates the vertical distance between the dune toe level and the water level at each time interval (as illustrated in

Figure 2), T denotes the wave period, and C

S is an empirical impact coefficient. The smaller the value of Z

D, the higher the risk of dune erosion. Additionally, a smaller value of Z

D increases the likelihood that waves will reach the upper part of the profile, resulting in R > Z

D + S. In this scenario, it is assumed that the wave impact is reduced due to additional overtopping flow over the dune (as expressed in Equation 2).

During an overtopping event, a portion of the sediments moved by the waves (∆V

D) is transferred to the landward side of the dune (∆V

L), resulting in a reduction of Y

L (i.e. inland displacement). In this case, the slope of the dune's landward face, represented by β

L, is assumed to remain constant. The remaining material is displaced toward the ocean (∆V

S). The distribution of ∆V

D between ∆V

L and ∆V

S, the amounts of the eroded dune volume directed landward and seaward, respectively, is determined by the coefficient α (Equation 3), as expressed by

=

/(1+ α) and

=

/(1+ α).

The empirical coefficient A, approximately established as 3 by [

11] through a comparative analysis with field data, plays a crucial role. When the variation in sediment volume (∆V

D) exceeds the initial volume (V

D), it is interpreted as an indication that the dune is undergoing erosive processes, as described by [

11].

2.2. Flume

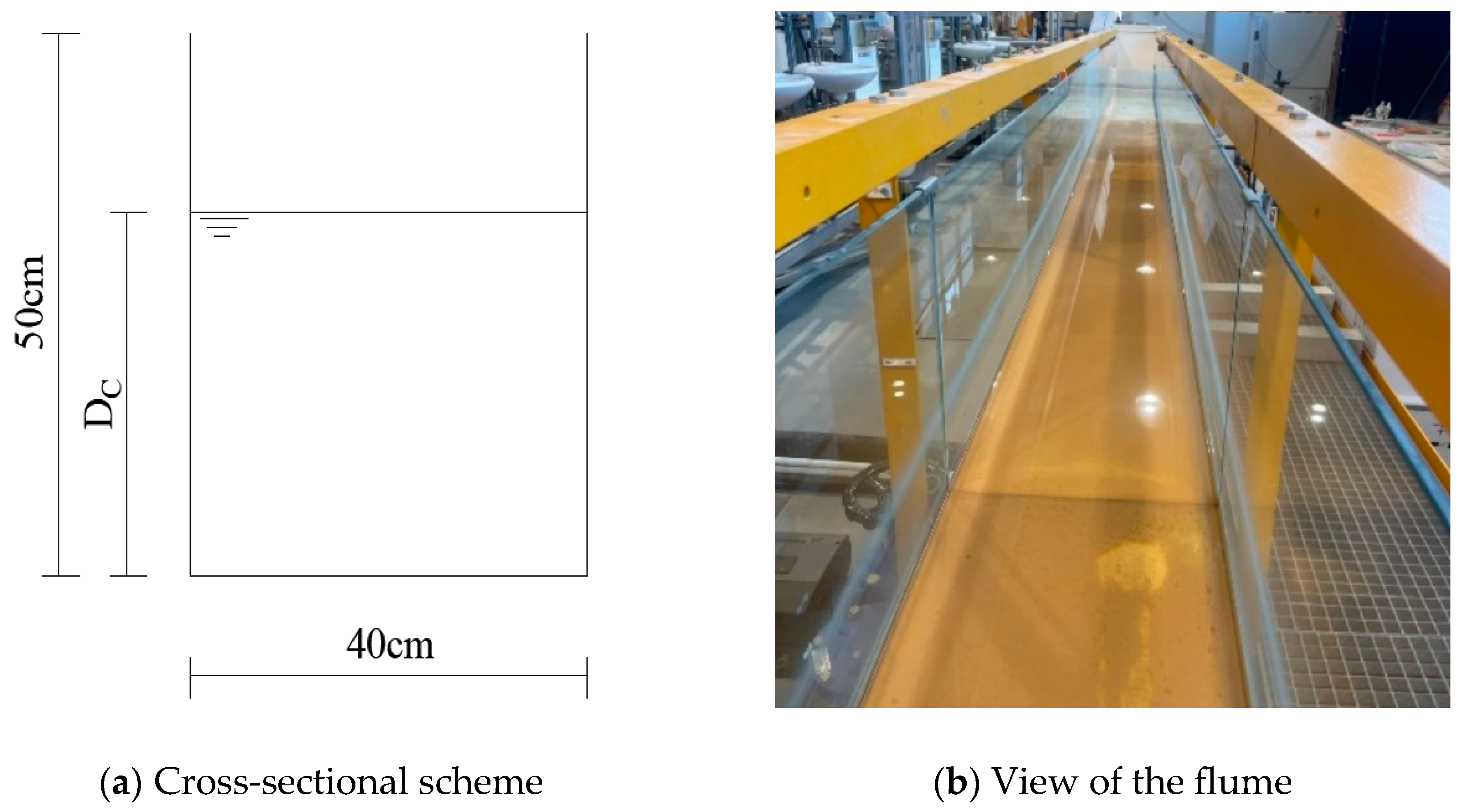

The hydraulic flume of the Civil Engineering Department, at the University of Aveiro, Portugal, has a usable length of 10 m, with a cross-sectional area of 0.40 m × 0.50 m (

Figure 3). Based on the limitations of the flume identified in previous studies ([

12]), a geometric scale of 1/40 was adopted. This scale, derived from Froude similarity, was used to construct a model of the cross-shore beach and dune profile.

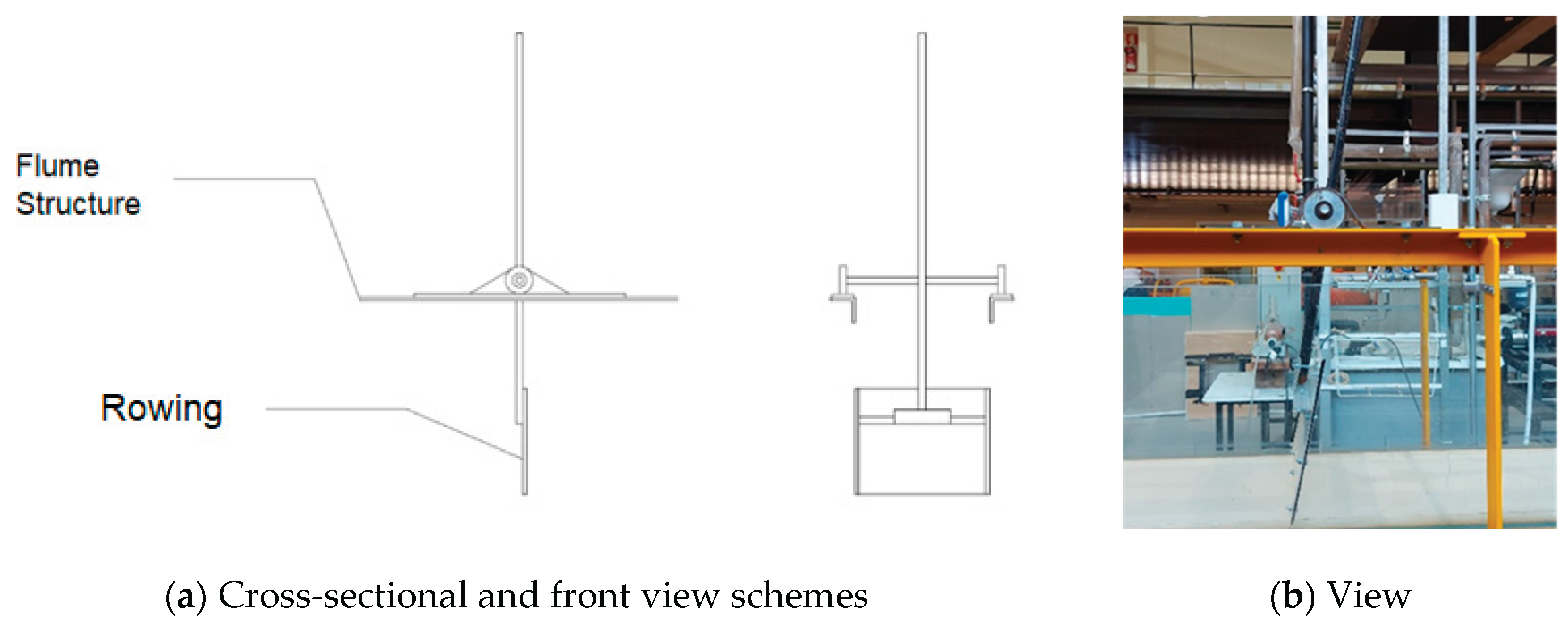

A manual wave generator was installed at the upstream end of the flume to produce controlled wave conditions for the experiments. The device operates through a pendulum motion and consists of acrylic plates connected to a system of steel shafts. The setup is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The water supply for the flume is provided by a pumping system. In the context of this study, the flume was kept in a horizontal position and, after being filled to the required water levels, the pumping system was turned off, initiating the tests in the flume.

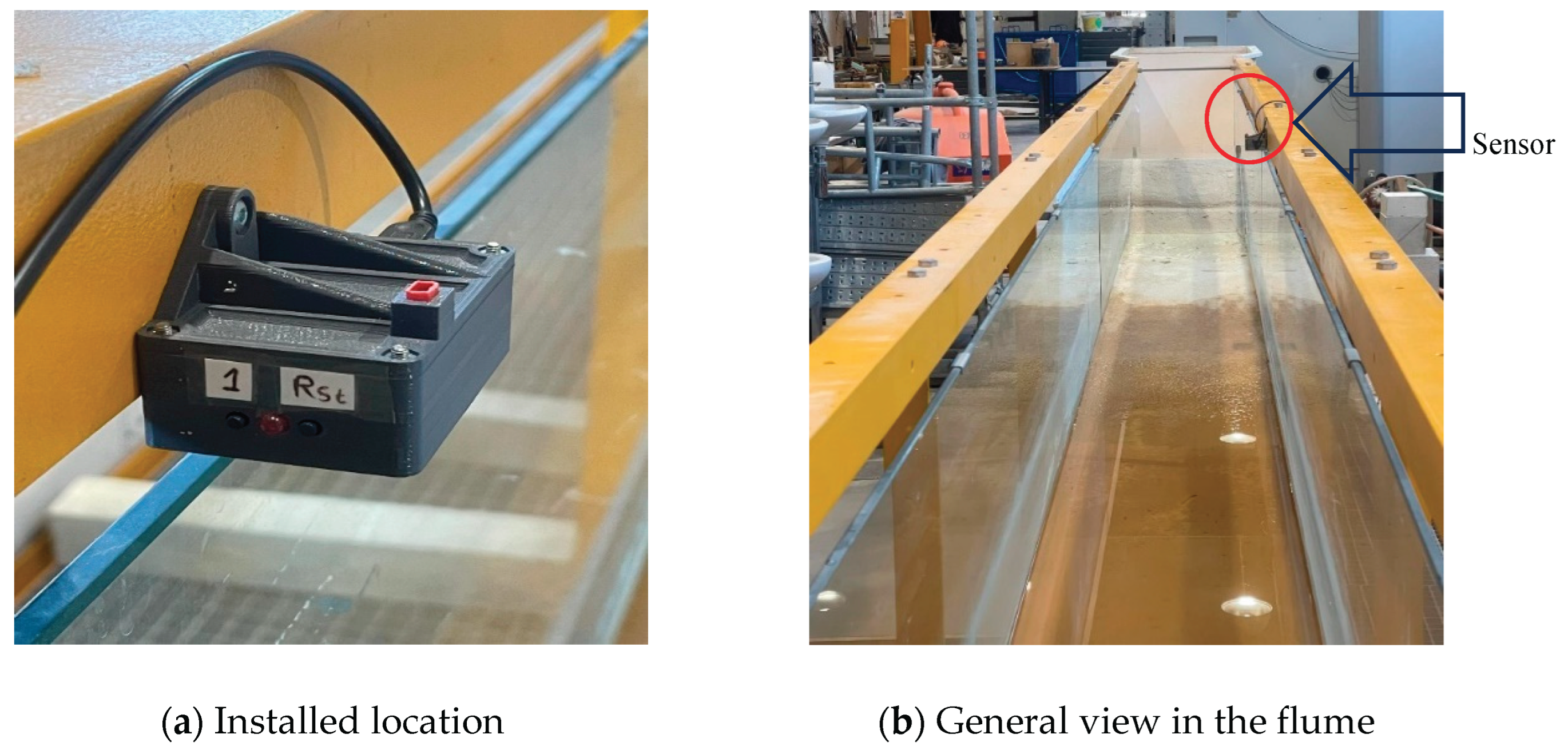

To evaluate and quantify the characteristics of the waves generated during the tests, an ultrasonic sensor was used (

Figure 5). This sensor operates by emitting ultrasonic pulses at intervals of 40 milliseconds, measuring the distance between the sensor and the water surface. The sensor was installed 4.30 meters from the wave paddle, in the area near the beach profile.

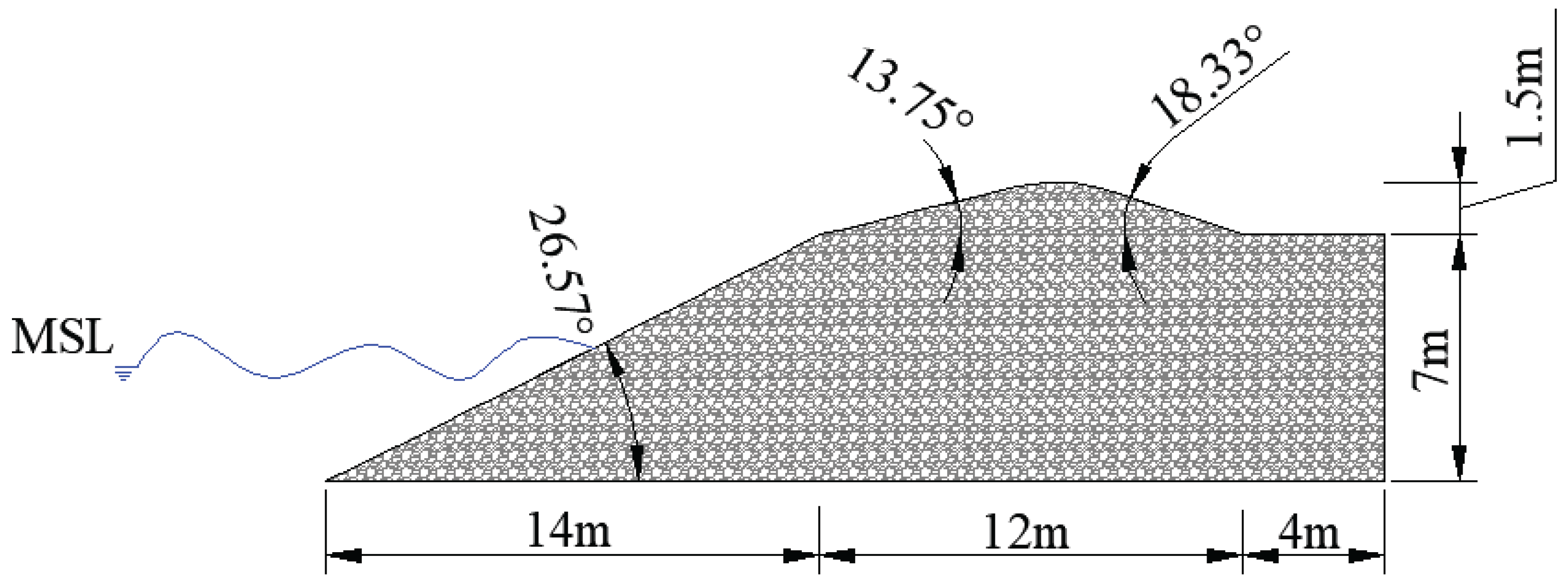

2.3. Reference Scenario

Several preliminary tests were carried out with the objective of defining a profile vulnerable to wave attack, but without overtopping, so that different reinforcement measures for the profile and their respective performance could later be evaluated. By varying the geometric parameters of the profile and the wave climate, some preliminary conclusions were drawn. In this regard, the profile represented in

Figure 6 was considered for the reference scenario, with the following values (prototype): 4 m (Y

L) for the location of the dune toe on the landward side, dune height of 1.5 m, and the position of the dune toe on the seaward side at 16 m (Y

s). This position coincides with the berm crest (Y

B), meaning that the reference profile does not include a berm.

For the wave climate, waves perpendicular to the beach were considered, with a wave height (H

0) of 2 m. The wave period (T) was calculated as a function of H

0 using the following expression ([

13]), resulting in a wave period of 9.34 s:

The reference scenario profile assumes a zero volume for the submerged bar. Subsequently, scenarios considering the presence of an initial submerged bar volume are presented. It should be noted that the CS-Model does not simulate the geometry of the submerged bar nor specify its exact position, considering only an available volume of sediments for bar-berm exchanges.

2.4. Scenario Definition

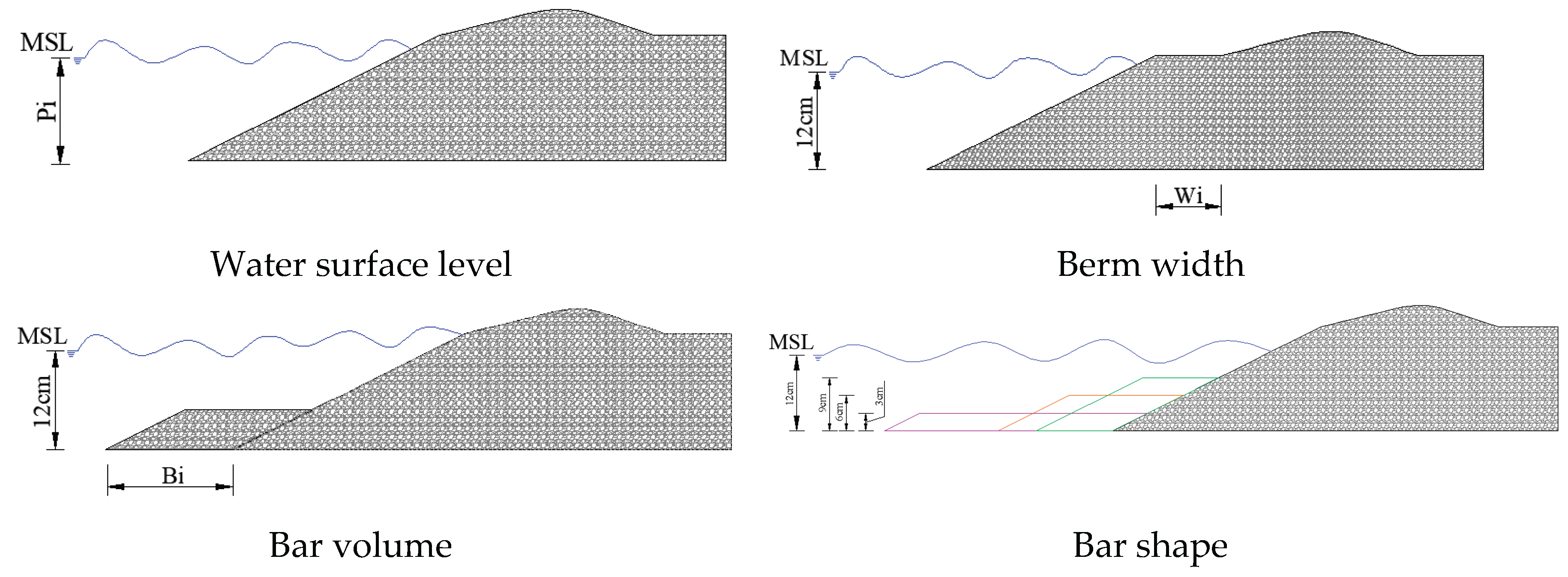

The developed tests aim to characterize the behavior of the beach and dune profile morphology under different conditions of water level, berm width, submerged bar volume, and bar shape. For this reason, values were established for different parameters, which were varied independently, while keeping all other variables equal to the reference scenario. The reference scenario corresponds to Scenario C0.

Three scenarios were defined with water surface levels varying between 12 cm, 11 cm and 10 cm (Pi), as indicated in

Figure 7a, corresponding to scenarios C0, C1, and C2, respectively. These levels allow for testing a beach profile without a berm for different water surface heights. These water levels were also chosen to allow the desired wave height , to ensure sufficient water depth in the channel to generate appropriate waves, while avoiding excessive water that could cause overtopping.

To evaluate the berm width, a volume of sand was added to the reference profile, creating a berm with increasing width, with Y

B values of 50 cm, 62.5 cm, 75 cm and 87.5 cm, corresponding to scenarios C3, C4, C5, and C6, as shown in

Figure 7b. The study of the variation in berm width (Wi) allows simulating artificial sand nourishment, enabling inferences about the morphology of profiles under the same wave climate.

For the study of the submerged bar volume’s effect on beach morphology, three scenarios were defined with volumes of 35 cm³/cm, 115.30 cm³/cm and 196 cm³/cm, corresponding to scenarios C7, C8, and C9, respectively, as shown in

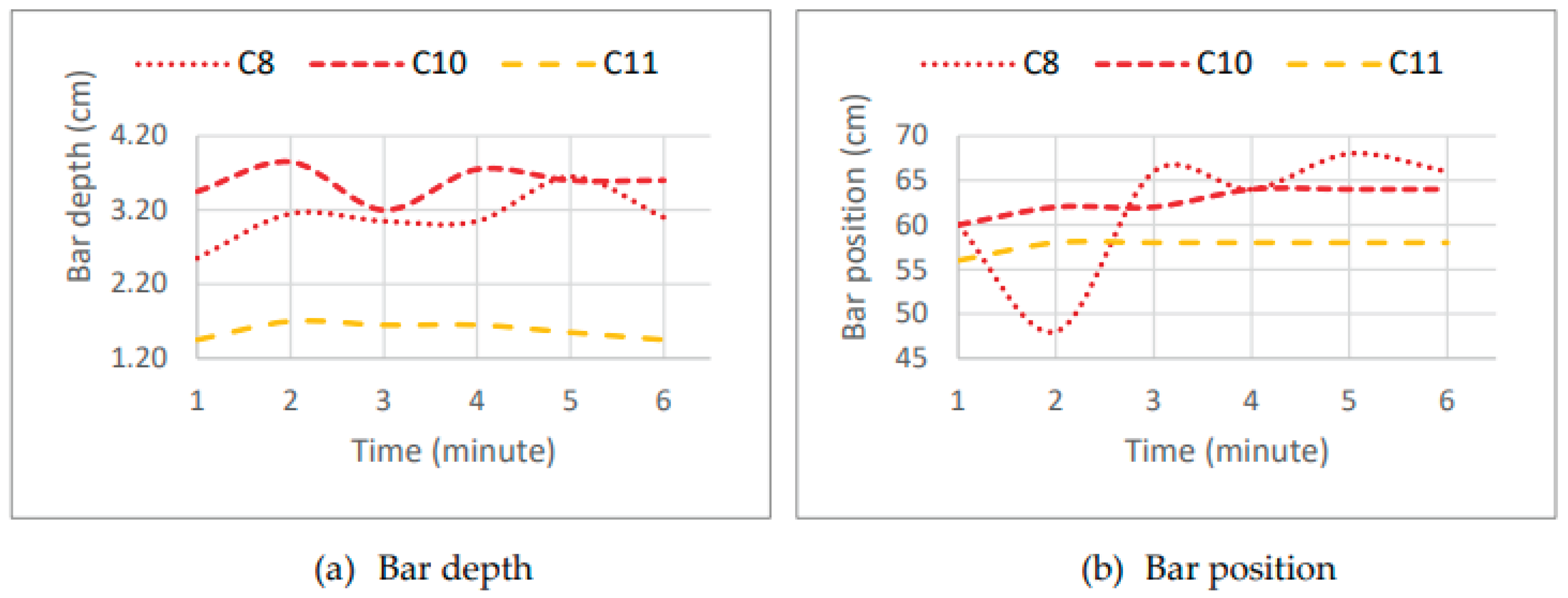

Figure 7c. The volume of 35 cm³/cm corresponds to the equilibrium volume of the submerged bar obtained in the CS-Model simulation, at the model scale. The volume of 115.30 cm³/cm represents the equilibrium volume of the submerged bar in the reference scenario from the laboratory flume experiment. However, for the CS-Model simulation of the prototype, the submerged bar volume was 409 cm³/cm, which was considered too large to be represented in the laboratory flume. For this reason, a volume of 196 cm³/cm was considered for scenario C9. For these scenarios, the same submerged bar height of 6 cm was considered, with the bar width (Bi) varying according to each of the mentioned volumes.

Three scenarios were considered to evaluate the bar shape, all with the same submerged bar volume. Thus, scenario C8, defined previously, was used as the reference, with a submerged bar volume of 115.30 cm³/cm. From this, two additional scenarios were defined: C10, with a submerged bar height of 9 cm; and finally, scenario C11, with a submerged bar height of 3 cm (

Figure 7d). In these two former scenarios, the width was adjusted to maintain the volume of 115.30 cm³/cm.

The parameters common to all scenarios are presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 summarizes the parameters considered to evaluate the performance of the beach and dune profile as a function of the water level (scenarios C0 to C2), berm width (scenarios C0 and C3 to C6), berm volume (scenarios C0 and C7 to C9), and berm shape (scenarios C8, C10, and C11).

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the simulations performed for each of the defined scenarios, followed by an interpretation of the morphological responses observed.

3.1. CS-Model

The CS-Model was used to simulate the same scenarios at both the physical model scale and the prototype scale, and the results were compared. The outcomes are organized by test type, focusing on water level, berm width, submerged bar volume and profile shape. To facilitate comparison between the physical model and the CS-Model, all values presented here refer to the physical model scale (1:40).

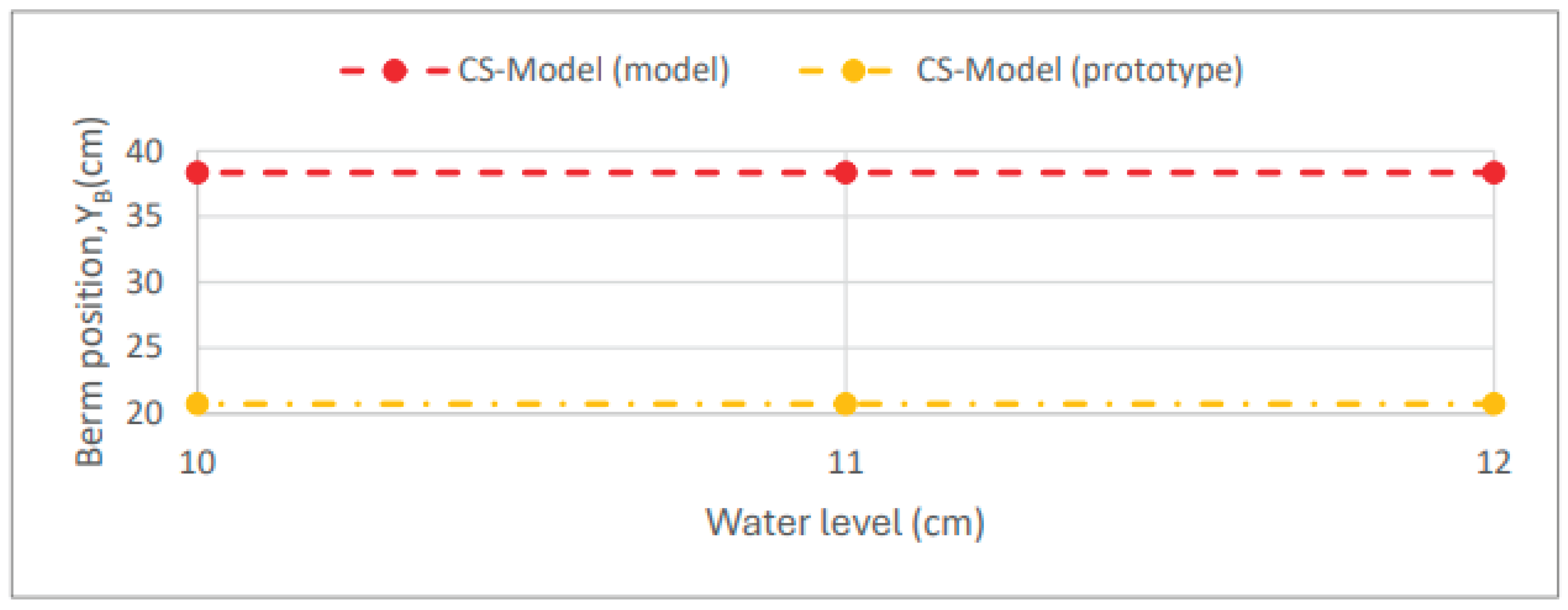

3.1.1. Water Level

Figure 8 shows the final berm position in the CS-Model (i.e., the base of the dune slope and the top of the beach slope) as a function of the water level. At the model scale, all three scenarios (C0 to C2) reached the same value for the final berm position of 38.35 cm, while at the prototype scale, all scenarios resulted in the same value of 20.75 cm.

It was observed that the numerical model is not sensitive to changes in the water level. In the CS-Model simulations at the prototype scale, a greater retreat of the dune was noted.

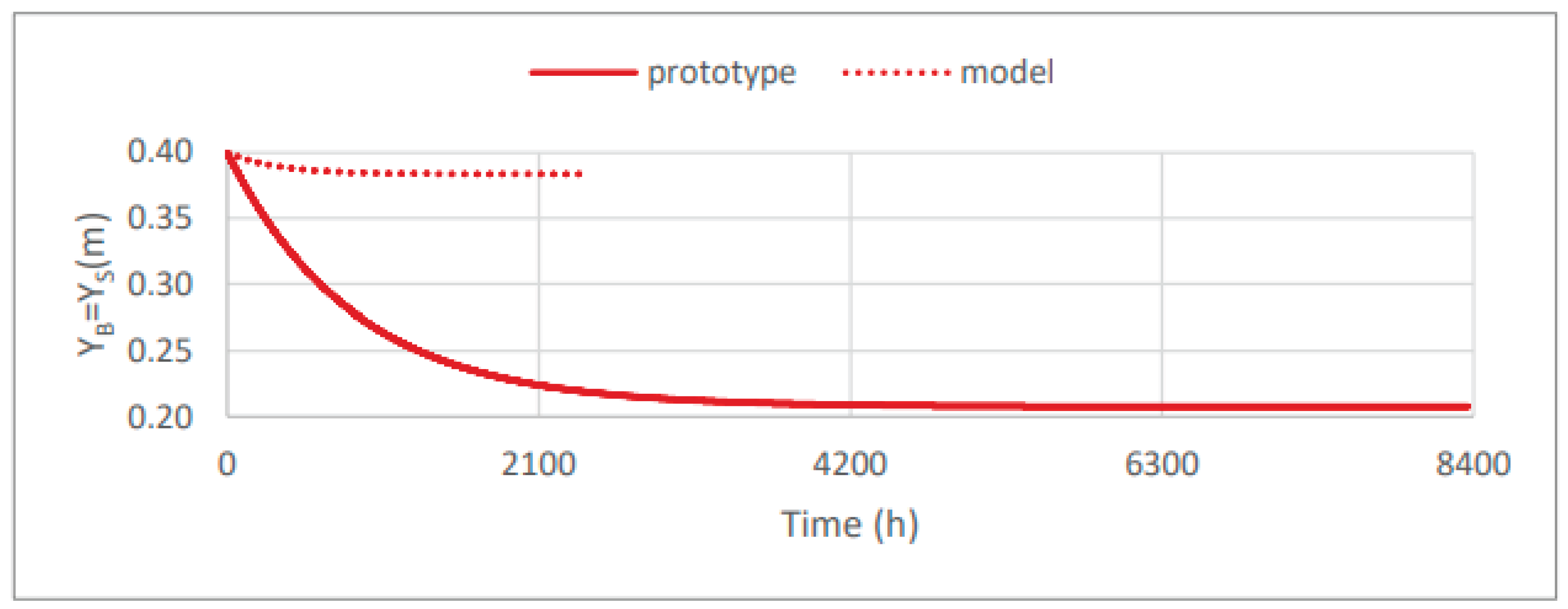

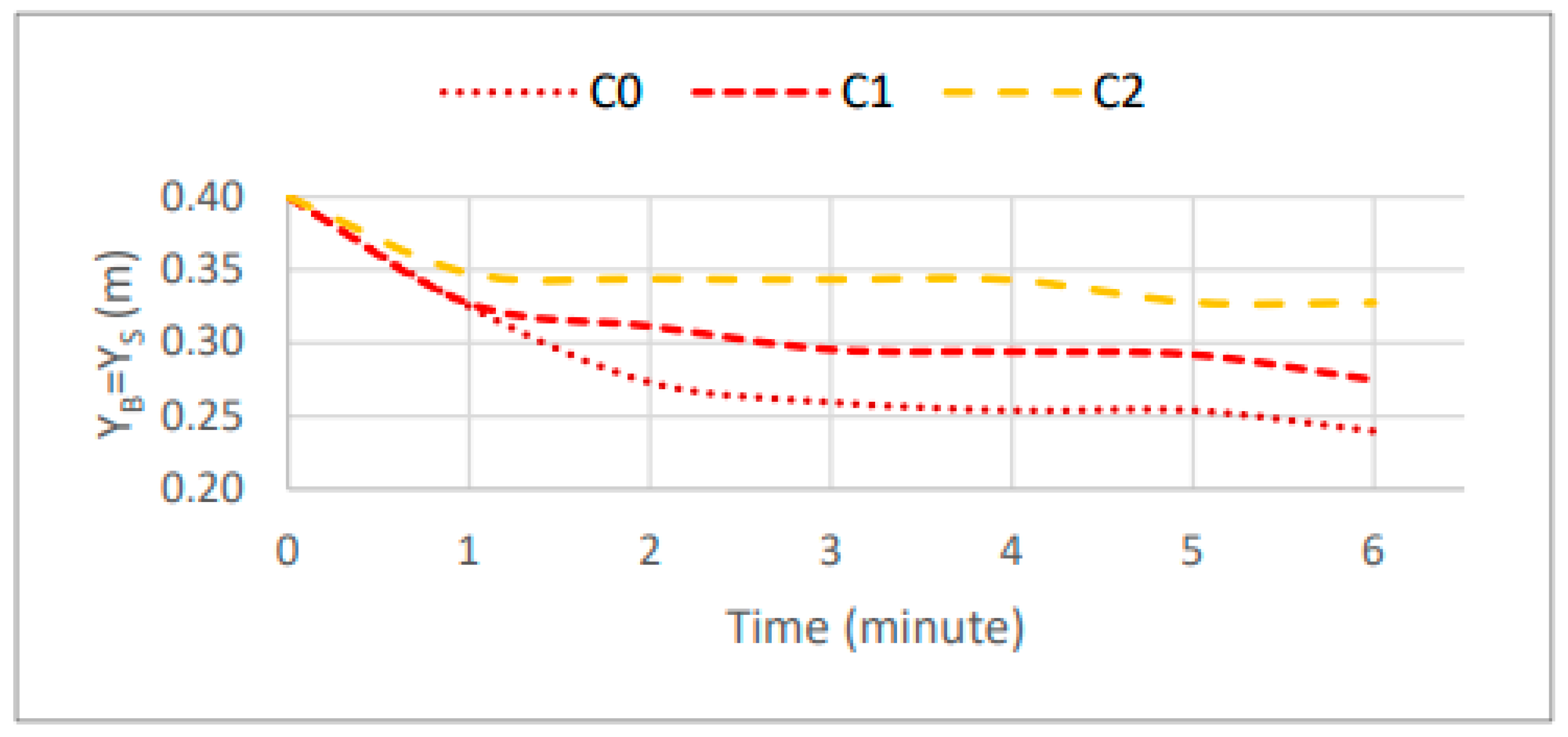

Figure 9 shows the time evolution of the berm position, allowing for a comparison between the numerical simulation results. It can be seen that the time evolution of the berm position in the CS-Model is independent of the tested scenario. At the model scale, there is a nonlinear reduction from 40 cm to 38.35 cm, while at the prototype scale, there is also a nonlinear decrease in the berm position, from 40 cm to 20.75 cm.

3.1.2. Berm Width

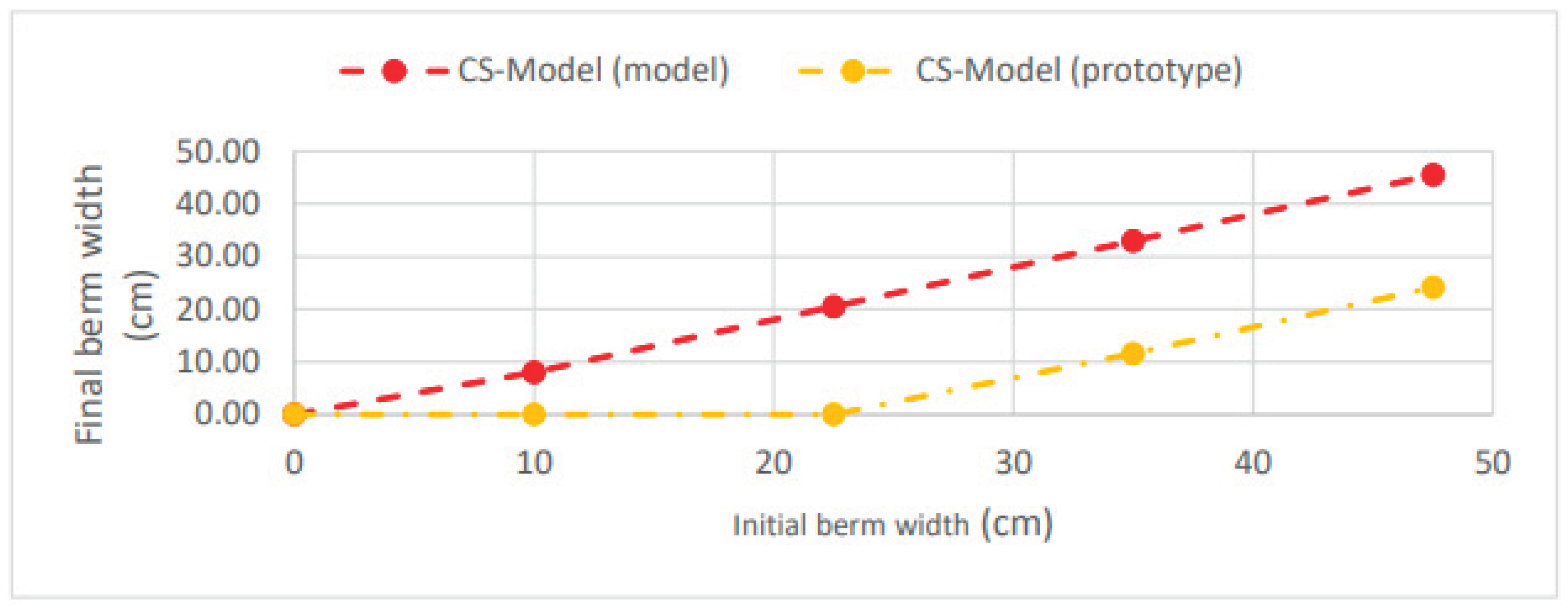

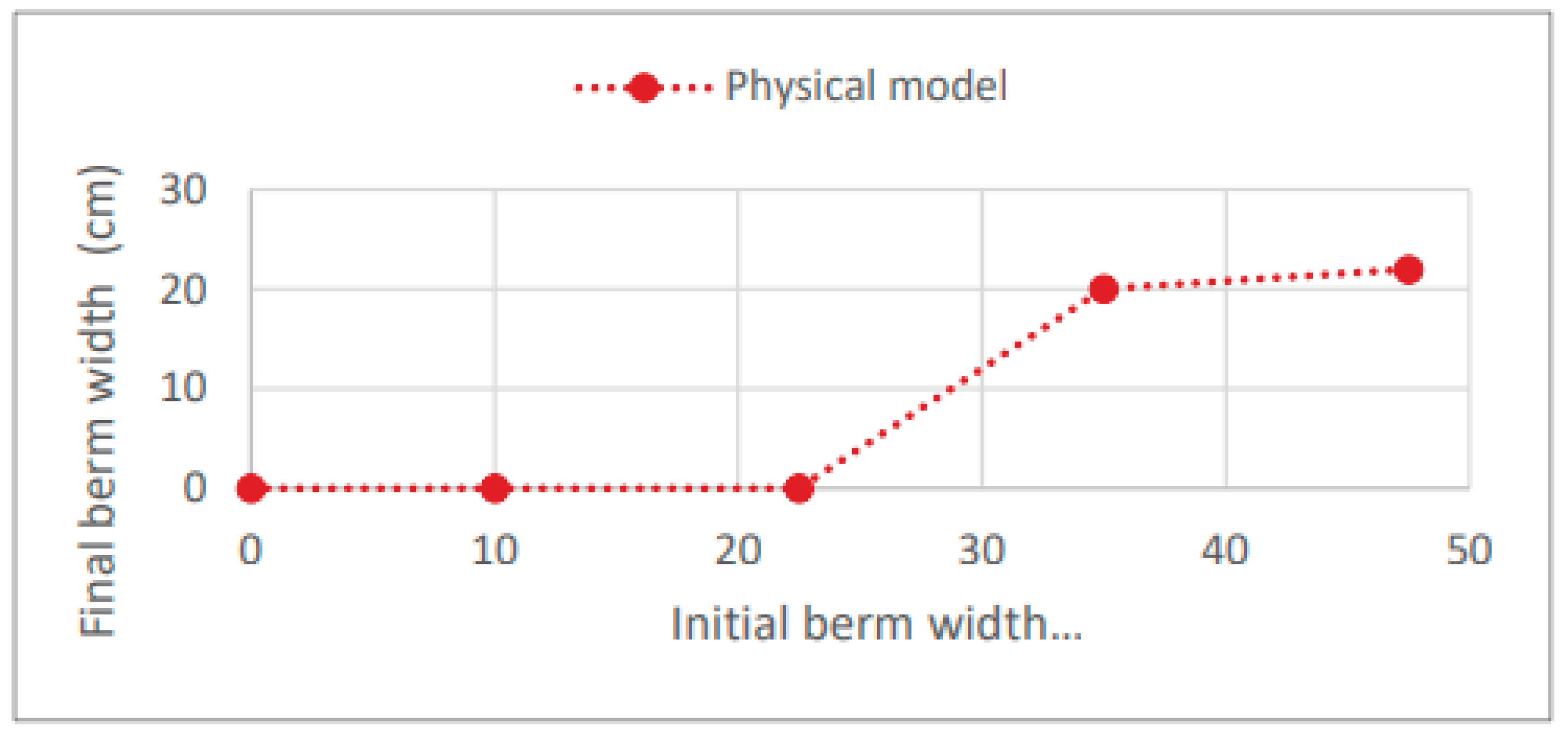

For the study of berm width, four scenarios (C3 to C6) were defined with initial berm widths of 10 cm, 22.5 cm, 35 cm, and 47.5 cm. The results from the numerical modeling are shown in

Figure 10, which presents the final berm width as a function of the initial berm width. The CS-Model simulation at the model scale for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6 resulted in final berm widths values ranging from 0 cm to 45.50 cm. In contrast, the CS-Model at the prototype scale yielded in values between 0 cm and 24.13 cm.

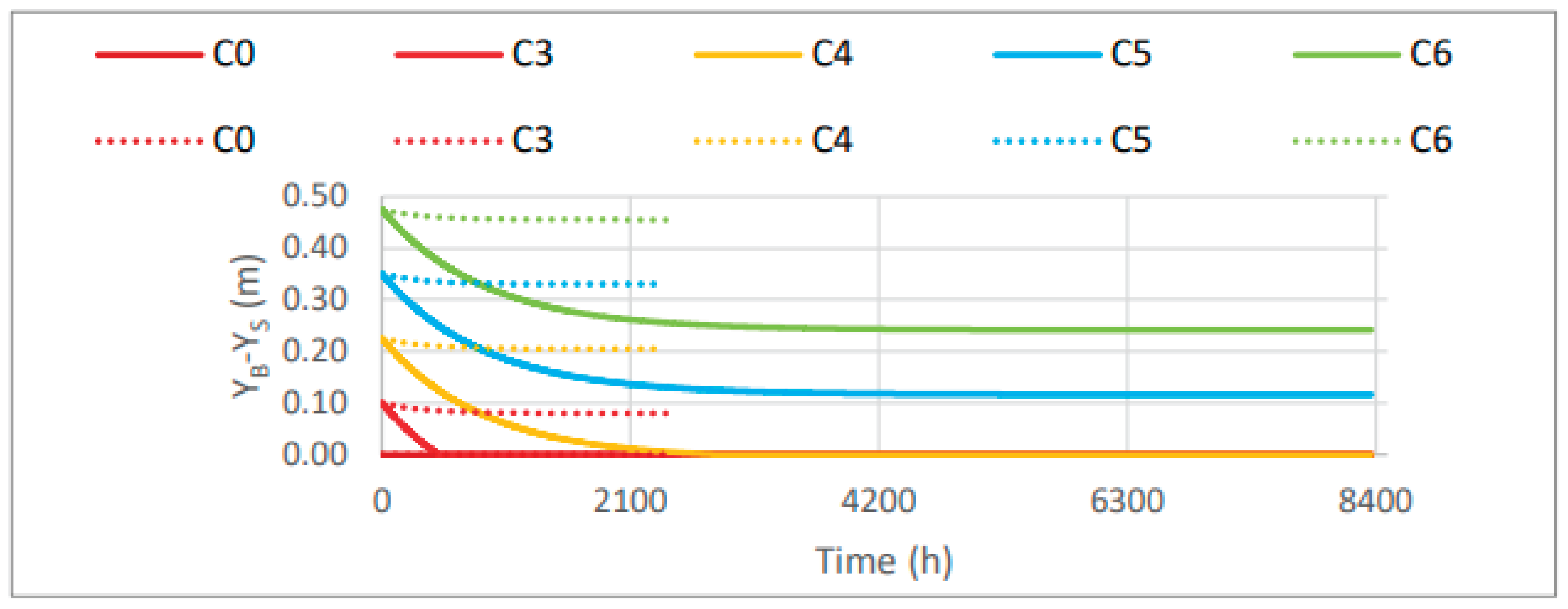

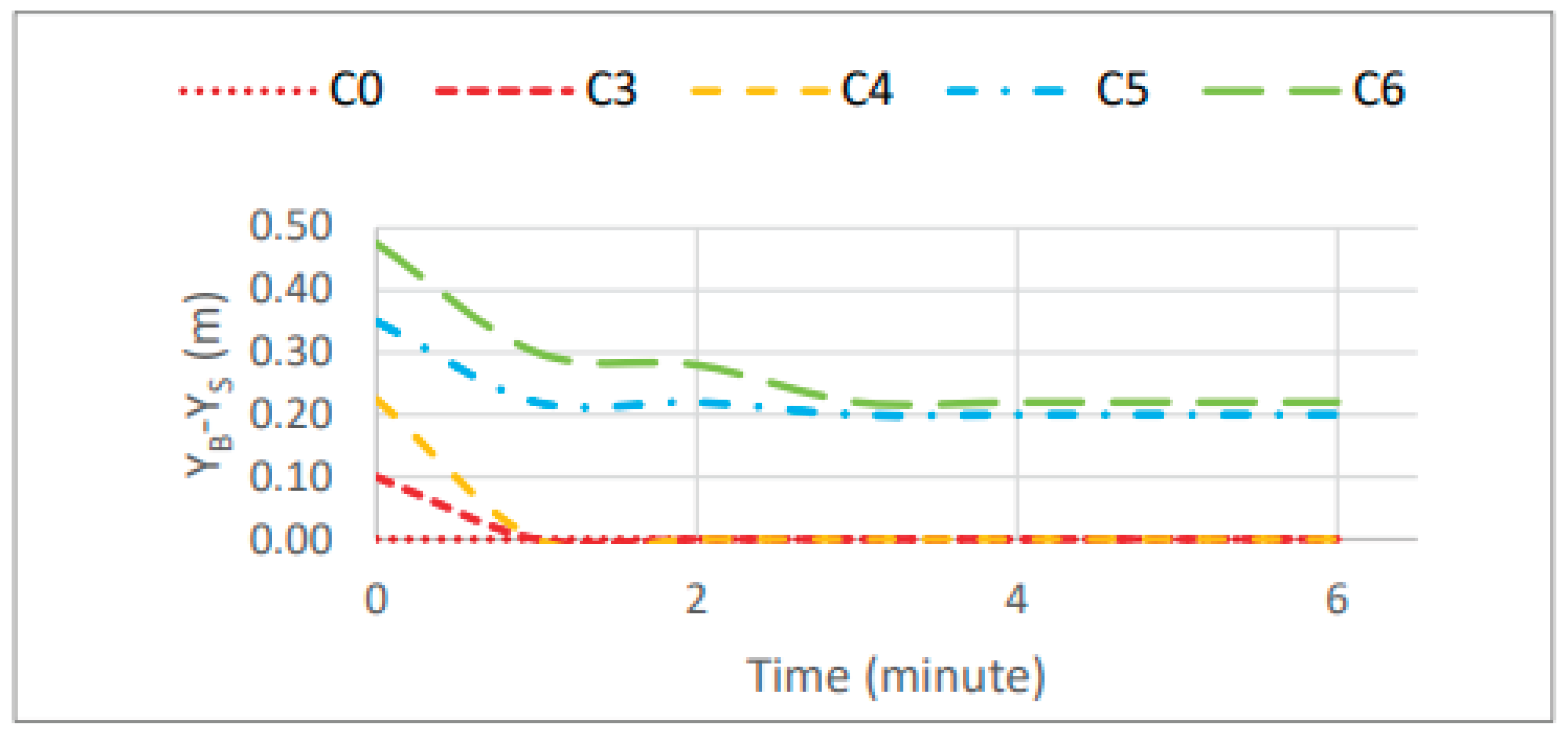

Figure 11 shows the time evolution of the berm width for each scenario (C0 and C3 to C6), based on the calculations performed by the numerical model. In the CS-Model, a nonlinear decrease in berm width over time is observed, tending to converge toward equilibrium. At the model scale, berm width decreased from 10 cm to 8 cm, from 22.50 cm to 20.50 cm, from 35 cm to 33 cm, and from 47.50 cm to 45.55 cm for scenarios C3 to C6, respectively. At the prototype scale, the berm width also decreased from 10 cm to 0 cm, from 22.50 cm to 0 cm, from 35 cm to 11.63 cm, and from 47.50 cm to 24.13 cm, according to scenarios C3 to C6, respectively. Therefore, the variations at the prototype scale are more significant. The results from the CS-Model at the model scale show proportional behavior across all scenarios, whereas at the prototype scale, the berm width becomes null in scenarios C3 and C4.

3.1.3. Volume of the Submerged Bar

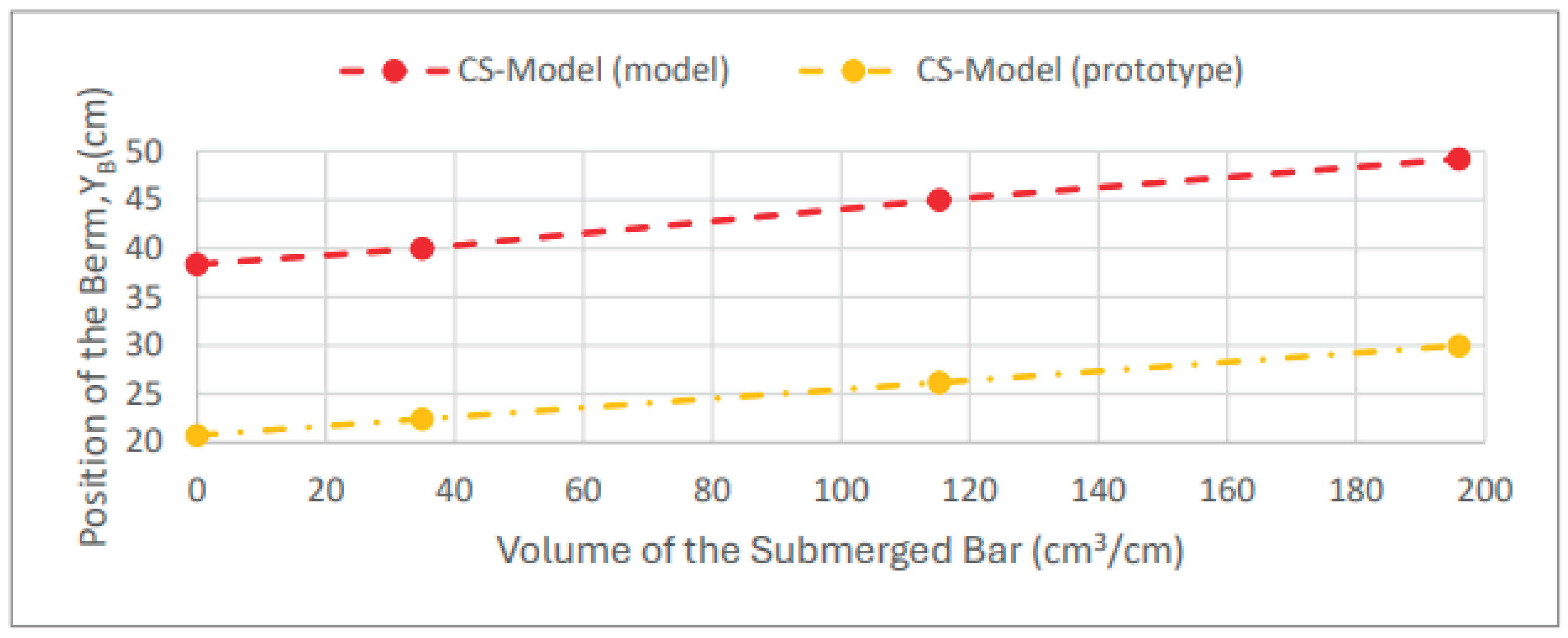

In the study of the submerged bar volume, three scenarios were considered (C7, C8, and C9). The results obtained from the CS-Model at both model and prototype scales are shown in

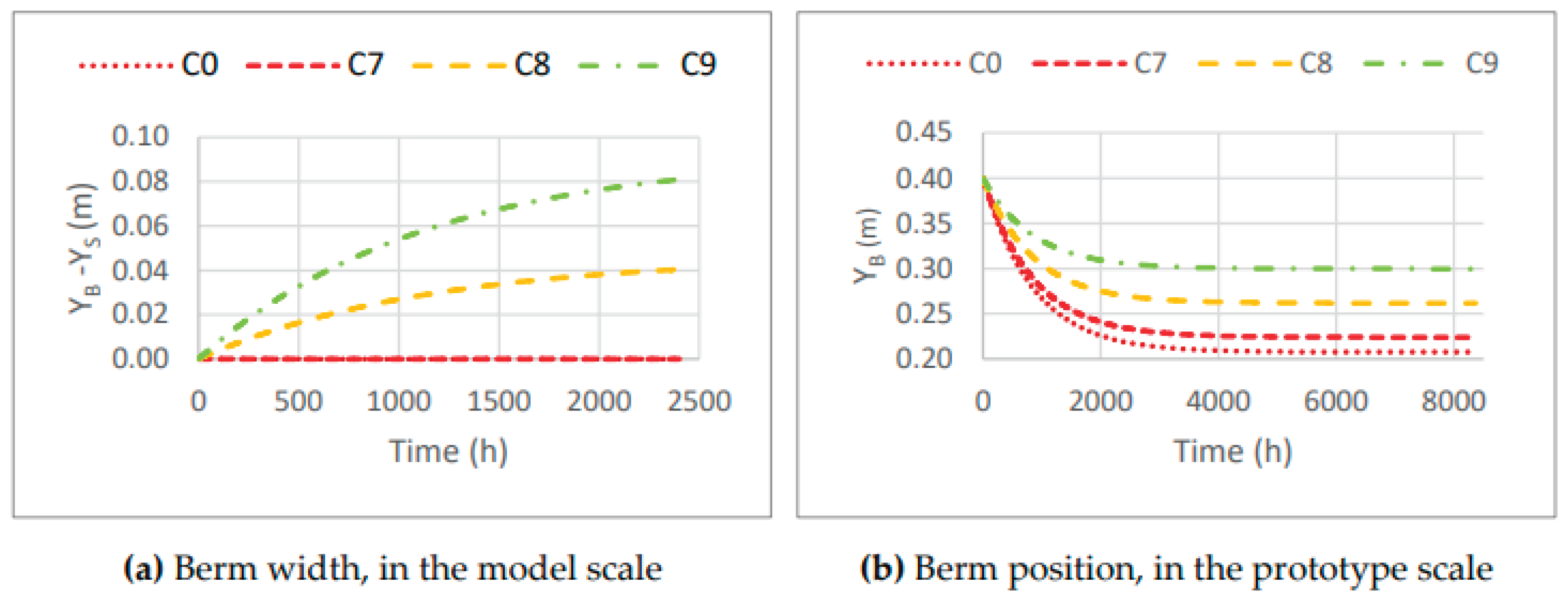

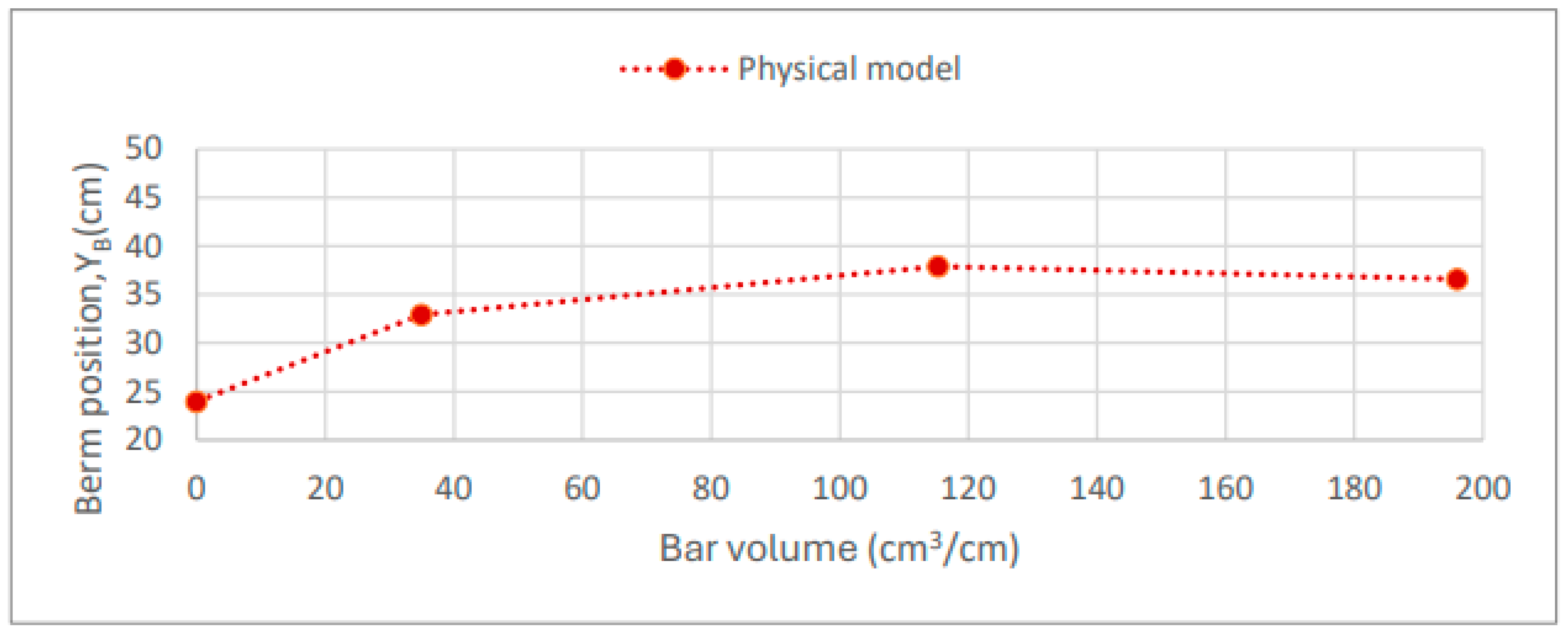

Figure 12, relating the berm position to bar volumes. In the CS-Model, at the model scale, the final position of the berm is 40 cm, 45 cm, and 49.2 cm for scenarios C7 to C9, emphasizing that in these simulations, the beach berm increased in width. For the results of the CS-Model at the prototype scale, the position of the beach berm was 22.40 cm, 26.18 cm, and 29.98 cm, for the respective scenarios C7 to C9. The CS-Model simulations show a linear variation in berm position as a function of bar volume, regardless of the scale (model or prototype).

In

Figure 13a, the evolution of the berm width over time at the model scale is presented. It is observed that the berm width increases over time, with increasing initial bar volumes, according to scenarios C7 to C9. At the prototype scale (

Figure 13b), the initial beach width is zero, as the wave climate caused a gradual recession of the berm position, resulting in final values of 22.40 cm, 26.18 cm, and 30 cm, for scenarios C7, C8, and C9, respectively.

It is observed that the CS-Model, at the model scale, created a berm for scenarios C8 and C9, while in scenario C7, there was virtually no change in the morphology, because the volume corresponding to the smallest bar in these scenarios is equal to the equilibrium volume of the submerged bar. It was noted that at the prototype scale, the equilibrium volume of the bar is higher than the volume considered in the three scenarios. Therefore, in this situation, the trend is for the beach and/or dune to lose material to the submerged bar, until the equilibrium volume of the submerged bar is reached. For this reason, in the CS-Model simulations at the prototype scale, there was always a recession of the dune.

3.1.4. Bar Shape

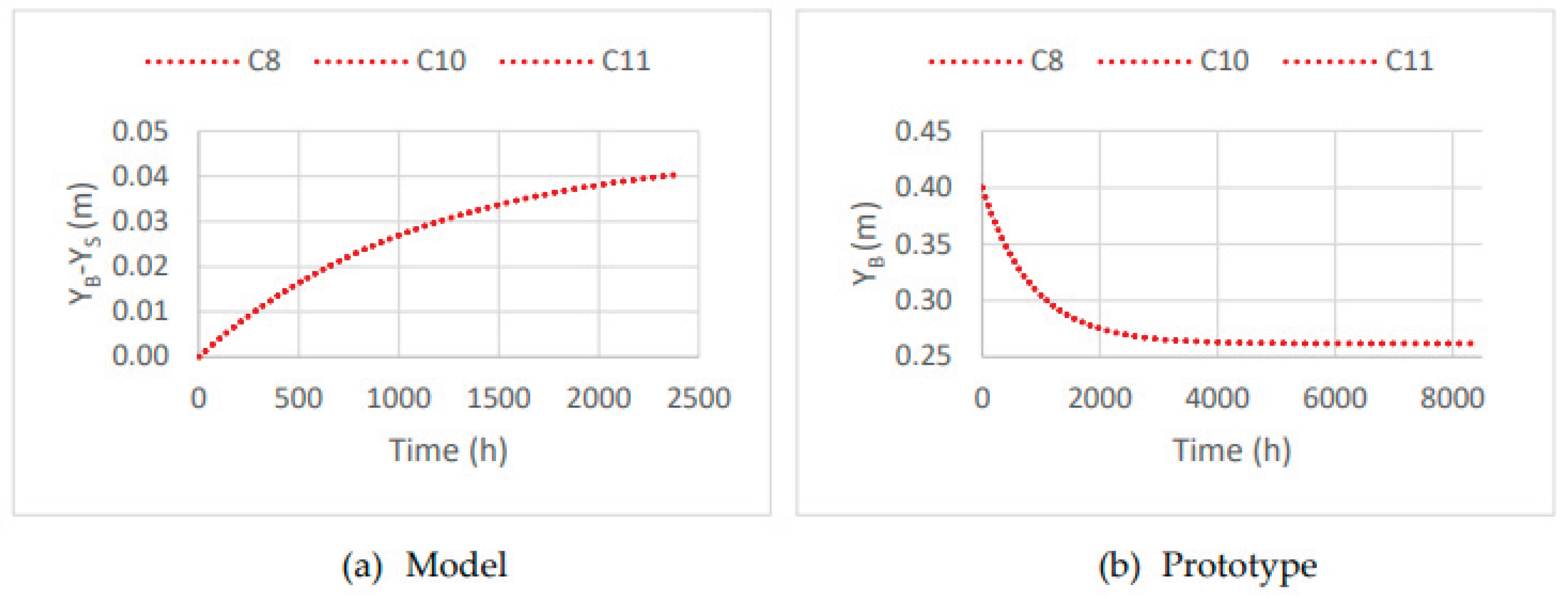

To analyze the shape of the submerged bar, three scenarios were considered (C8, C10, and C11). The results from scenario C8 were presented in the previous section and serve as a reference for the simulations of the other bar shapes. In the numerical simulations using CS-Model, it is not possible to reproduce the exact shape of the bar, because the model defines the bar only through its volume, VB. Thus, the results and values of the CS-Model for both the model scale and the prototype scale are presented in

Figure 14. For the CS-Model at the model scale, the final berm position is 45 cm, implying a gain of material for the beach berm. However, for the CS-Model at the prototype scale, the final berm position is 26.18 cm, resulting in a recession of the berm position.

Figure 14a presents the time evolution of the berm width, representing the result of the CS-Model at the model scale for the three scenarios (C8, C10, and C11), while

Figure 14b presents the time evolution of the berm in the CS-Model at the prototype scale, with the berm position varying from 40 cm to 26.18 cm.

3.2. Flume

Laboratory tests were carried out for the same scenarios defined in the numerical simulations, allowing for a comparison between physical and numerical results. The results are organized by test type, with particular focus on the profile shape, water level, and the submerged bar volume, position, and crest depth.

3.2.1. Water Level

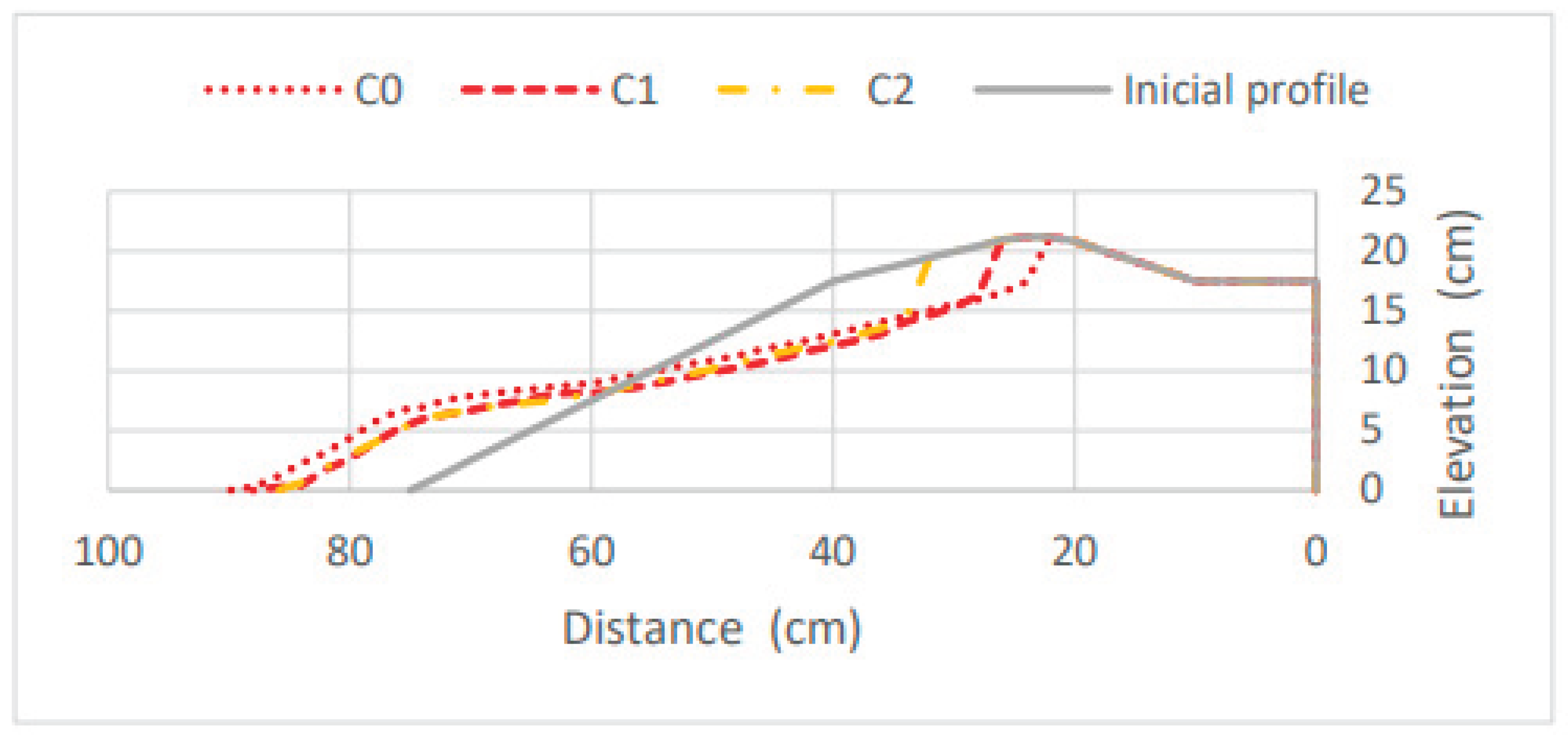

To assess the morphological effects observed in tests C0 to C2,

Figure 15 presents the final beach and dune profiles recorded at the end of each laboratory experiment.

Throughout the tests, it was observed that the sand gradually migrated downward along the profile, with the erosion volume defined as the area below the initial profile. Simultaneously, a bar forms in the lower section of the profile (area above the initial configuration), considered as the accretion volume. The morphology of each test, at each one-minute time step, was compared to the reference scenario profile, enabling the quantification of the volumes corresponding to the erosion and accretion zones, as presented in

Table 3.

Upon analyzing

Table 3, it was observed that almost all the relative difference percentages are below 10%, a condition sufficient to ensure mass conservation in the profile during the laboratory experiments. In scenario C1, a slight decrease in the bar area was observed between the 5

th and 6

th minutes. This behavior is believed to be related with a reduced measurement precision, as all other results indicate a progressive evolution toward equilibrium.

The scenario with the lowest water level, corresponding to scenario C2, shows the smallest morphological variations. Scenario C1, in turn, presents the highest erosion volume, with 11.66 x 10⁻³ m³/m, while scenario C0 reveals the highest accretion volume, approximately 11.53 x 10⁻³ m³/m. In scenario C1, beach and dune erosion were more significant, while in scenario C0, dune erosion was greater than in the other scenarios. In all scenarios, the largest morphological variation occurred within the first 60 seconds. During the first 60 seconds, the erosion rates of 46.83%, 56.50%, and 69.54%, and accretion rates of 55.14%, 79.14%, and 68.85%, respectively, were observed for scenarios C0, C1, and C2, when compared to the final situation of the test.

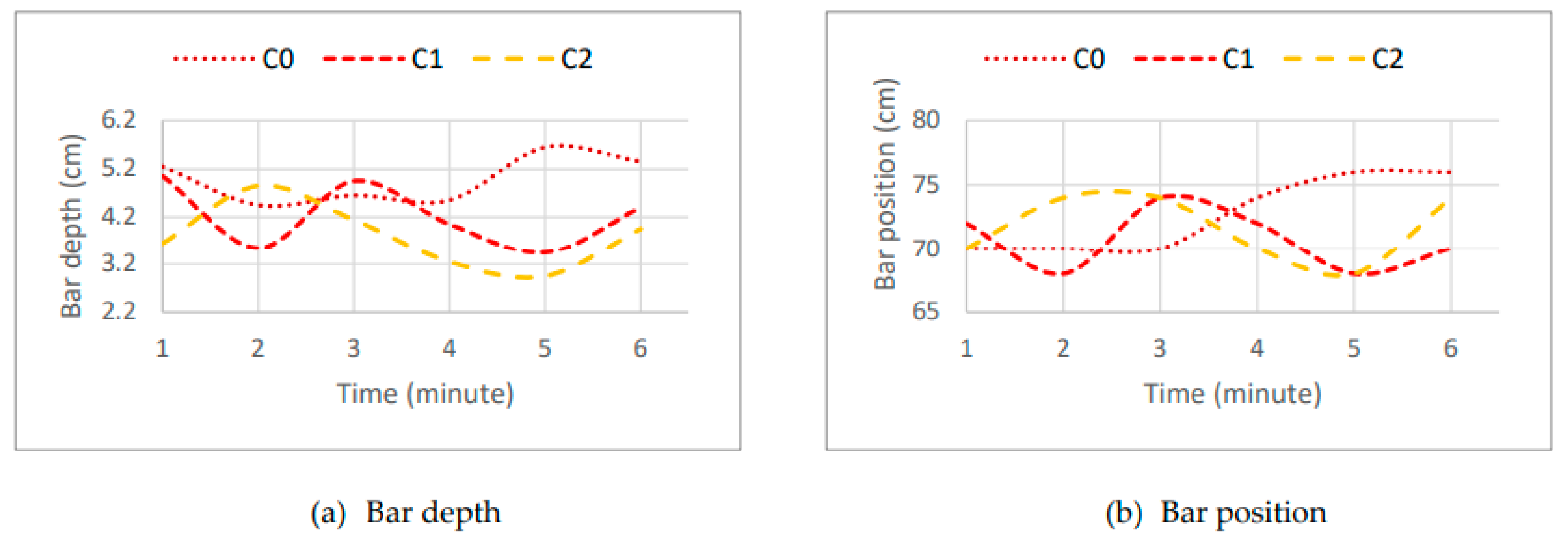

Figure 16 shows the variation over time of the depth and position of the bar crest in scenarios C0 to C2. The bar crest was identified as the inflection point of the submerged bar shape, characterized by the change in the slope of the upper face of the submerged profile.

In this regard,

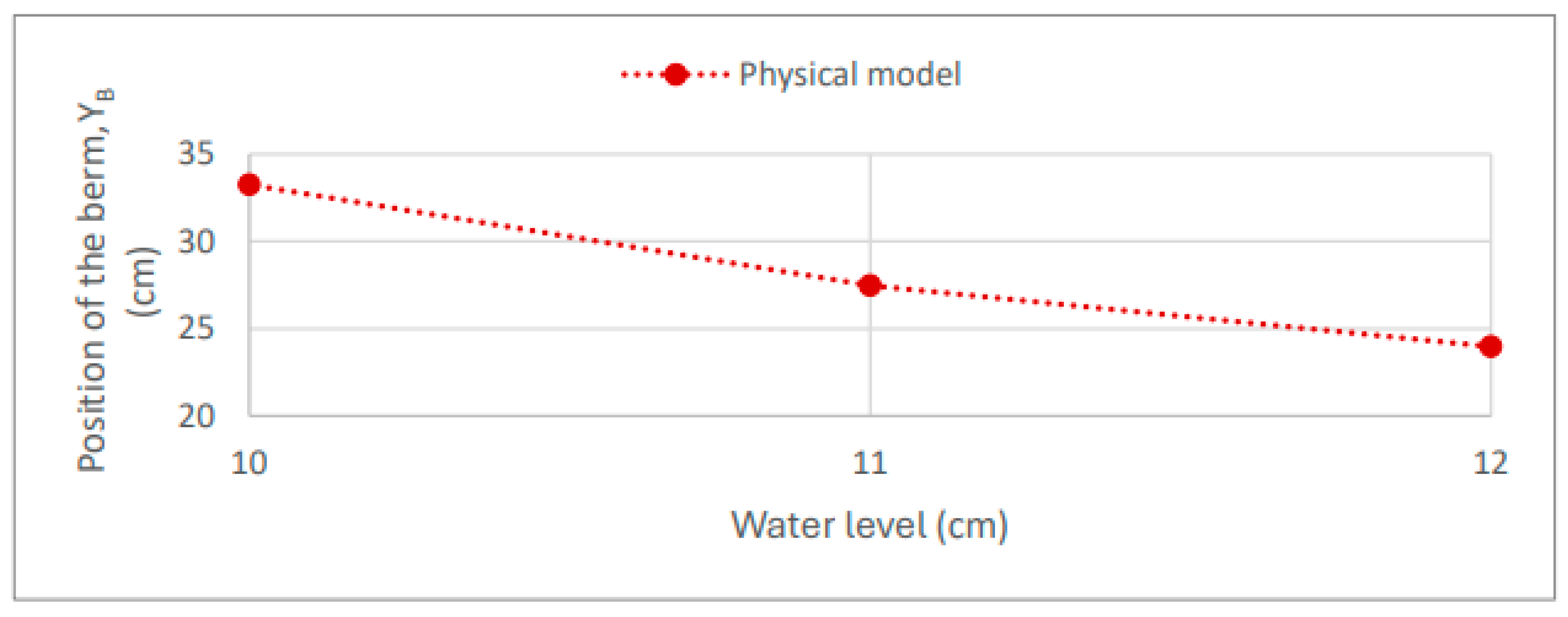

Figure 17 shows the position of the final berm (base of the dune slope and top of the beach slope) as a function of the water level. Thus, the physical model results are situated between 23.97 cm and 33.25 cm.

In

Figure 18, it can be seen that the temporal evolution of the berm position in the physical model is independent of the scenario. It is also observed that the position of the seaward berm toe is directly proportional to the water surface level, with smaller retreats of the berm position as the water surface level decreases.

3.2.2. Berm Width

For the study of berm width, four scenarios (C3 to C6) were defined, with the following berm widths: 10 cm; 22.5 cm; 35 cm; and 47.5 cm.

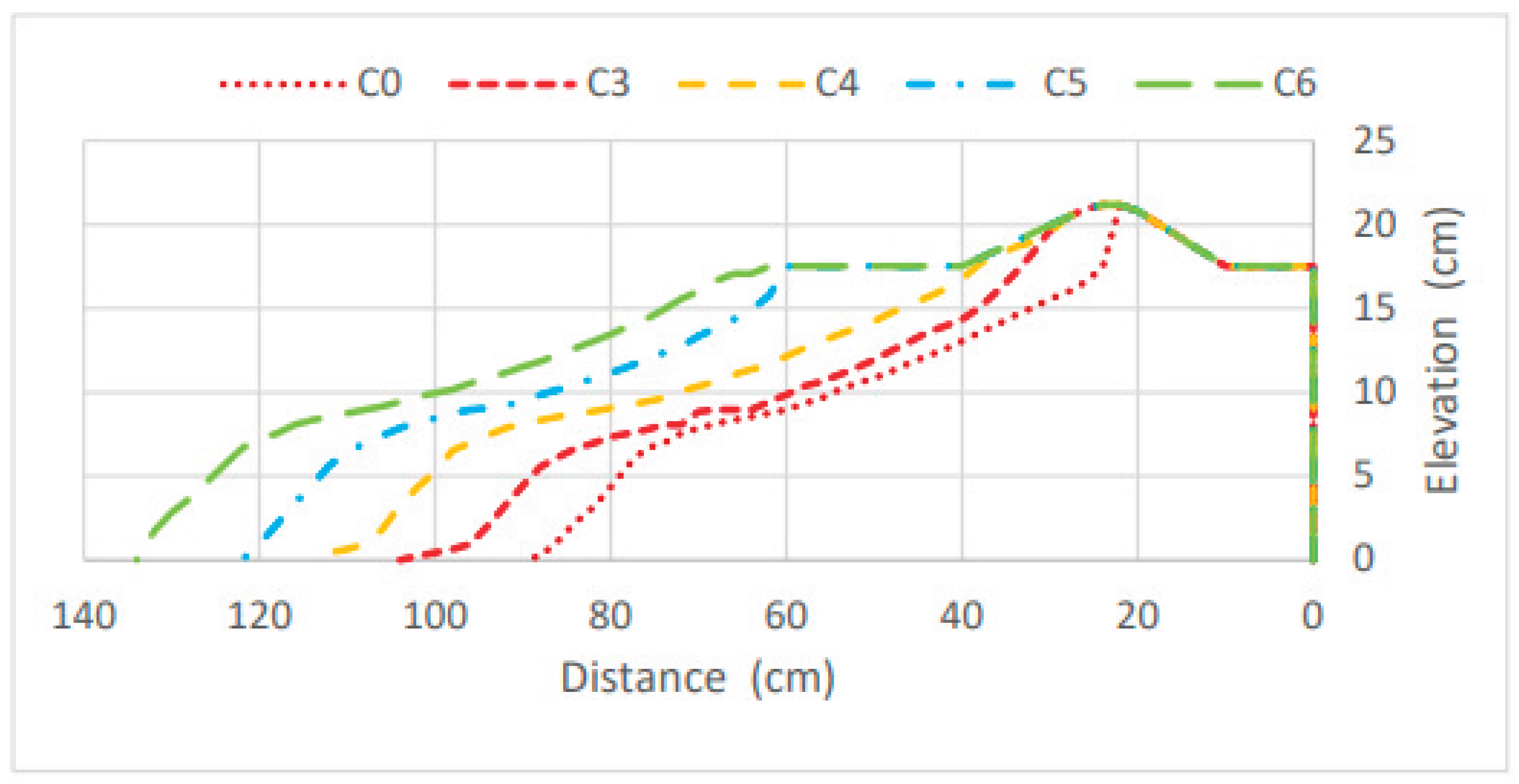

Figure 19 represents the morphology of each laboratory test at the end of six minutes, thus allowing the observation of the effect of increasing berm width. It should be noted that, the greater the initial berm width, the smaller the retreat of the dune toe position at the end of the test, and consequently, the smaller the erosion caused to the dune.

Table 4 presents the erosion and accretion volumes for each berm width scenario, minute by minute.

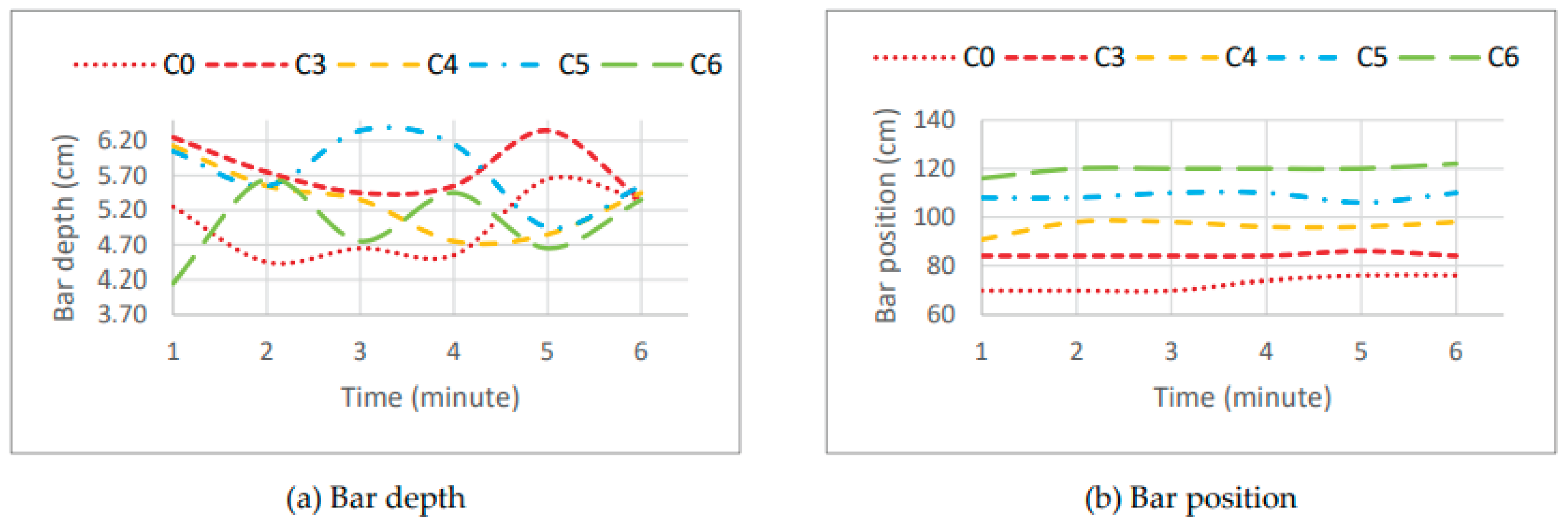

In scenario C4, a slight decrease in the bar volume was observed in the last minute of the test. It is noteworthy that, regardless of the berm width, the final bar volume ranges from 10.56 to 10.90 x 10⁻³ m³/m, indicating a trend that suggests the formation of the bar is not dependent on the berm width. It is also relevant to note that the greatest erosions occur in scenarios C3 and C4, because the dune is directly affected by wave action, while in scenarios C5 and C6, the berm is sufficiently wide, preventing dune erosion, and the final erosion volume is lower than in C3 and C4.

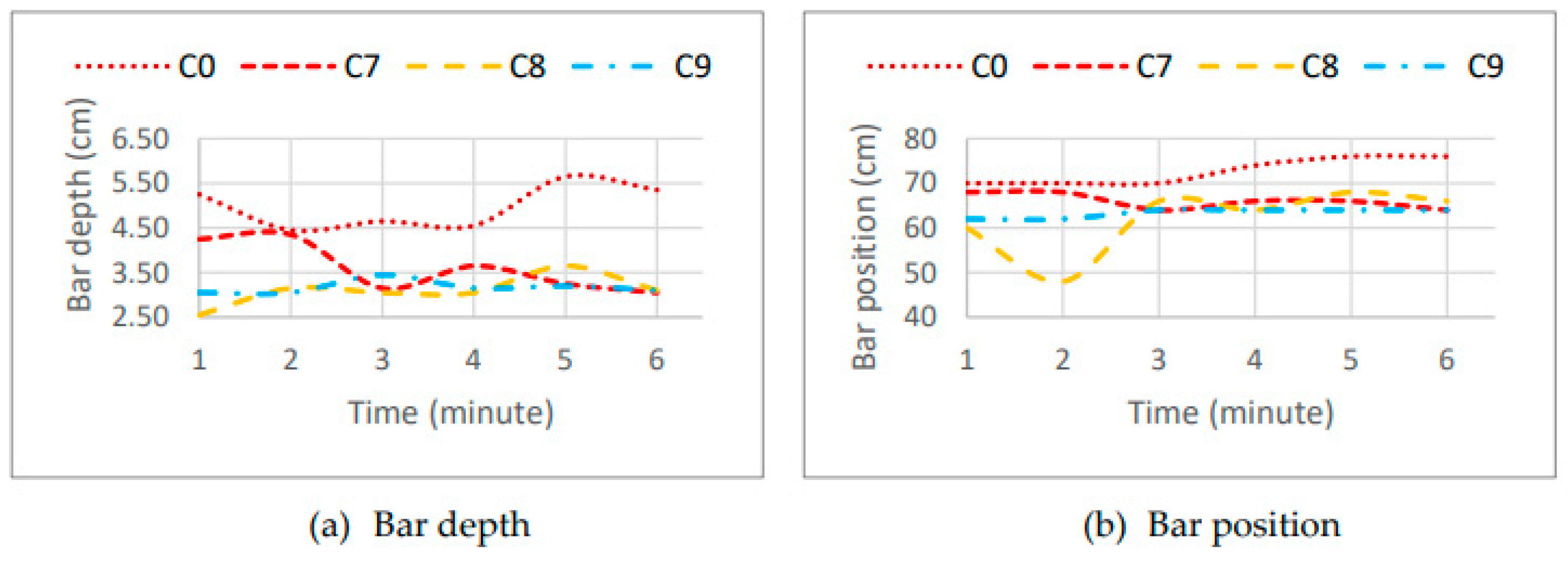

Figure 20 shows the variation over time of bar depth and position for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6. In

Figure 20a, it is observed that the bar crest depth is independent of the amount of material used, displaying an oscillatory behavior over time, which tends to converge to the same value of 5.35 cm at the end of the test. In

Figure 20b, it is observed that the bar position is directly proportional to the berm width, with larger berm widths corresponding to a further offshore bar crest position.

The results of the physical model are shown in

Figure 21, where the final berm width is presented as a function of the initial berm width. The physical model shows final berm widths ranging from 0 cm to 22 cm.

Figure 22 presents the temporal evolution of berm width for each scenario (C0 and C3 to C6) of the laboratory tests.

Upon analyzing the laboratory tests, it was observed that the results for scenarios C3 and C4 are quite similar, with final berm position (YB) values of 33.25 cm and 38.33 cm, respectively. Both of these scenarios resulted in dune erosion, with scenario C3 showing a higher erosion rate. Therefore, it can be stated that increasing the berm width was beneficial for better dune shape preservation. In scenarios C5 and C6, the dune was preserved as the erosion did not affect the dune, with wave energy dissipated along the berm. Additionally, in these two scenarios, a residual berm width was maintained. At the end of the tests for scenarios C5 and C6, the berm position was 60 cm and 62 cm, resulting in final berm widths of 20 cm and 22 cm, respectively.

3.2.3. Volume of the Submerged Bar

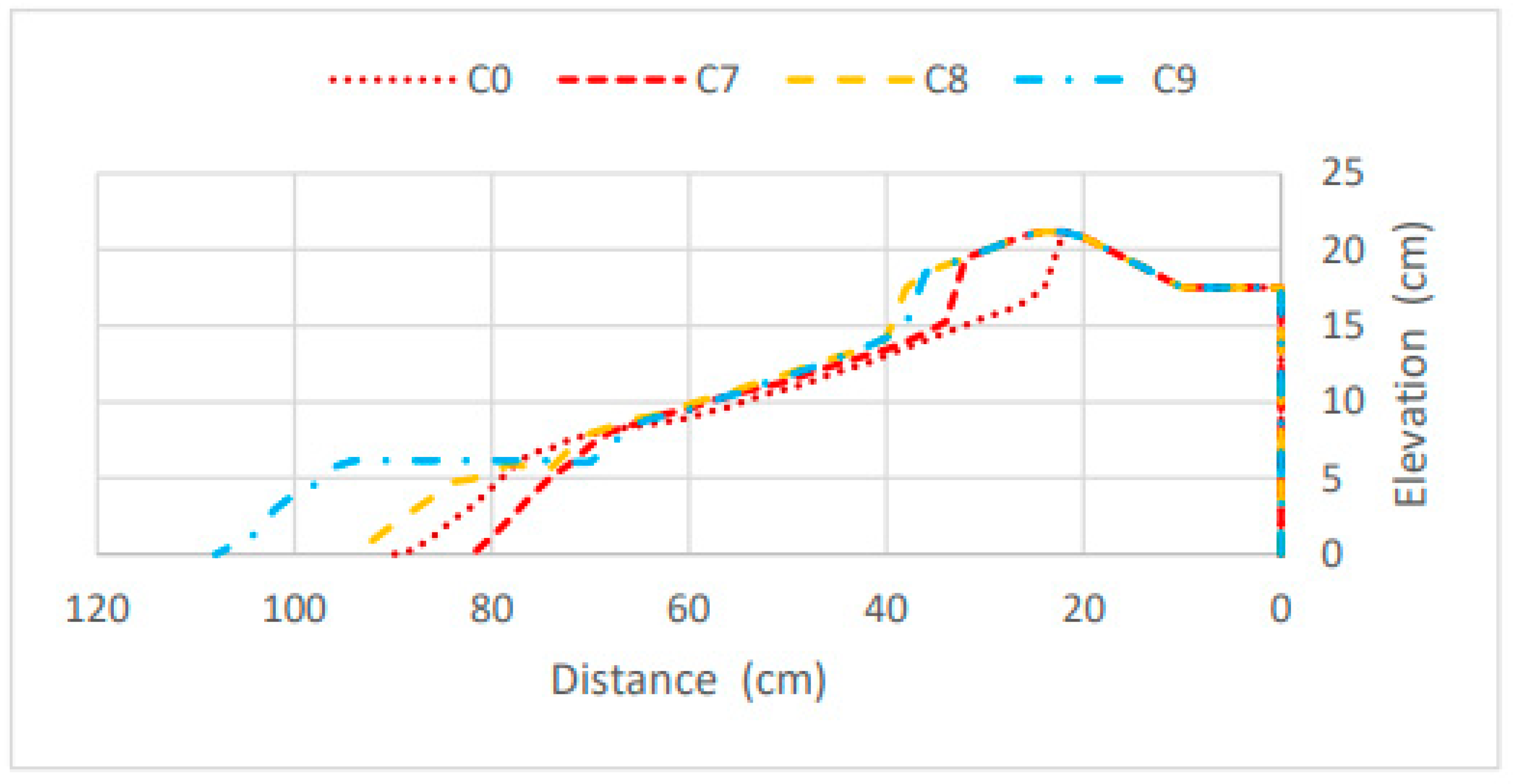

In the study of the submerged bar volume, three scenarios were considered, C7, C8, and C9. After obtaining the morphological evolution of the conducted tests, it was possible to represent their morphology at the end of the test (

Figure 23).

Based on the morphological evolution recorded throughout the tests, it was possible to determine the erosion and accretion volumes resulting from sediment dynamics for each minute of the tests performed (

Table 5). It is observed that adding an initial volume to the submerged bar improved dune preservation compared to the reference scenario, C0. However, in scenarios C7, C8, and C9, erosion on the dune still occurred. The values obtained for the dune toe position at the end of their respective tests were 32.92 cm, 37.90 cm, and 36.57 cm, respectively. Therefore, the smallest submerged bar volume, scenario C7, corresponds to the greatest dune erosion. However, despite scenario C8 having a smaller bar volume than scenario C9, it resulted in better dune preservation than scenario C9 .

In scenarios C7 and C9, a slight decrease in the erosion volume was observed in the last minute of the test, showing some stability in the behavior, which tends to converge towards equilibrium. In

Figure 24, it can be seen that the initial bar volume caused the initial position and depth of the crest to differ, but they tend to evolve towards the same final result, with the exception of just one scenario, C0, which corresponds to the reference scenario.

The laboratory test results for C0 and C7 to C9 are presented in

Figure 25, relating the berm position to the bar volumes.

3.2.4. Bar Shape

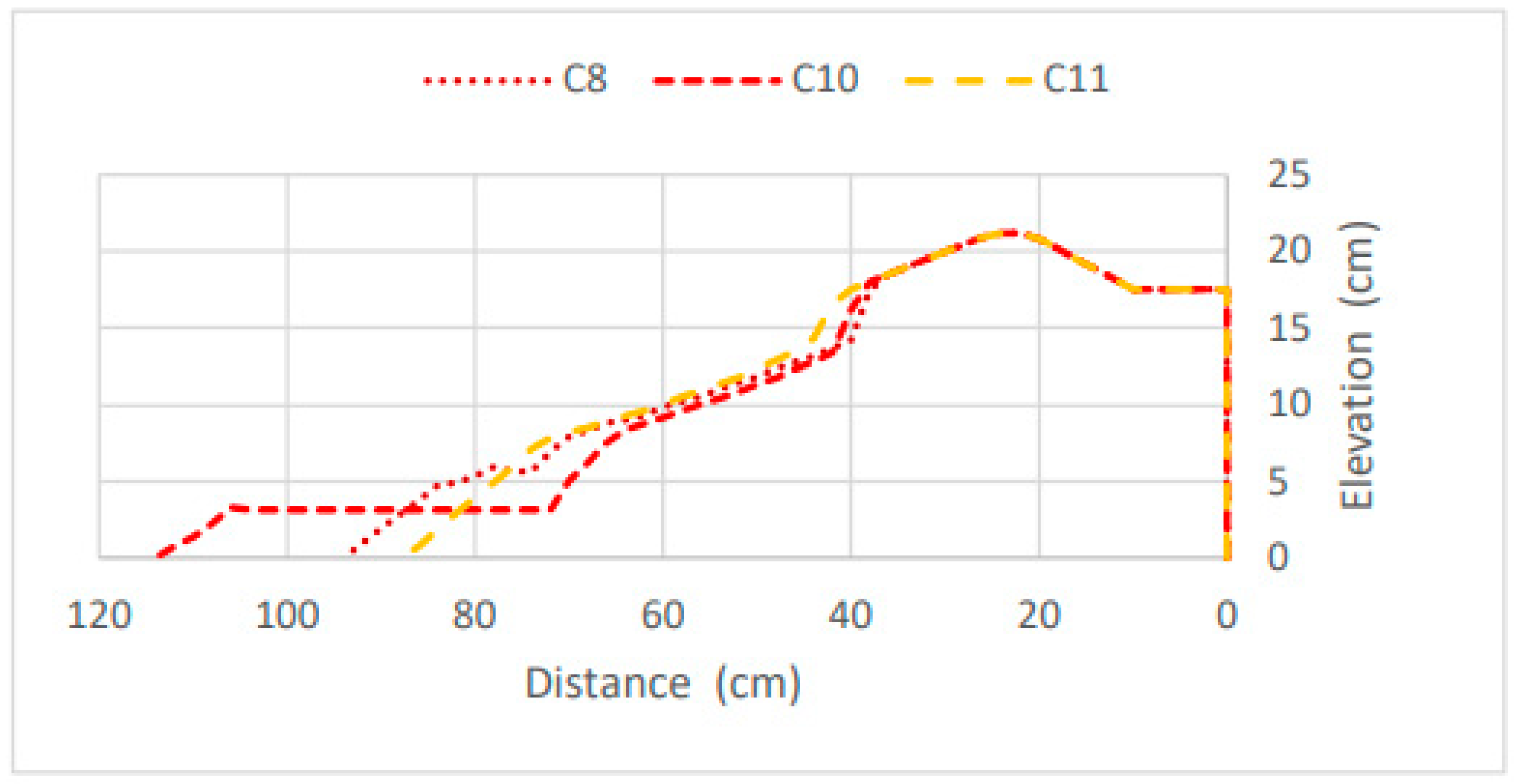

To analyze the shape of the submerged bar, three scenarios were considered: C8; C10; and C11. The results for scenario C8 were presented in the previous section and serve as a reference for the tests involving other bar shapes.

Figure 26 depicts the morphology of each of these scenarios at the final stage of the laboratory tests, illustrating how the shape of the submerged bar can influence the profile morphology.

Based on the morphology of each test, it was possible to determine the erosion and accretion volumes over time (

Table 6).

In scenario C11, the morphological changes over time were reduced, suggesting that the initial bar shape is closer to the equilibrium, thereby minimizing sediment dynamics. Similar to scenario C8, scenarios C10 and C11 showed improved dune conservation compared to the reference scenario, C0. The final values of the berm position (Y

B) were 37.9 cm, 38.53 cm, and 40 cm for scenarios C8, C10, and C11, respectively. It was observed that scenario C10, despite having a lower submerged bar height, exhibited a lower erosion rate than scenario C8. However, in both scenarios (C8 and C10), erosion slightly affected the dune. Therefore, among these scenarios, only scenario C11 ensures dune conservation, as erosion did not impact the dune at any point.

Figure 27 further confirms that scenario C11 exhibits reduced sediment dynamics, maintaining the bar crest position and corresponding depth constant over time.

4. Discussion

This section presents a critical analysis of the results from the numerical simulations and laboratory tests. A comparison of the performance of the CS-Model at both prototype and model scales is discussed, aiming to better understand the coastal erosion processes, particularly the interactions among the beach profile, dune system, and submerged bar.

The study demonstrated that the CS-Model is not sensitive to variations in water level, as the results were identical for different water levels in scenarios C0 to C2. This behavior may be attributed to the simplification of boundary conditions in the numerical model, which does not account for dynamic variations in water levels, unlike coastal models that integrate tides and other factors [

2]. Moreover, dune retreat was more pronounced in the CS-Model at the prototype scale, indicating an overestimation of erosion. This is likely due to the lack of variability in erosive processes, such as the interaction between water and sediments [

2]. According to [

14], an increase in the water surface level amplifies the interaction between waves and the beach profile, accelerating erosion. The results of this study confirm this trend, with scenario C1, which features a higher water level, causing greater erosion in the upper part of the beach.

It was observed that a greater berm width acts as a buffer, reducing dune and beach erosion, especially in scenarios C5 and C6. However, the simulations at model and prototype scales showed differences in berm width variations. These discrepancies can be explained by the CS-Model's limitation in simulating the dynamics of water and sediment transport in the berm interaction zone [

15]. The relationship between berm width and the reduction of dune erosion is well documented, as shown by [

16]. This study supports these findings, demonstrating that a wider berm results in the dissipation of wave energy, preventing dune erosion. In scenarios C5 and C6, berm width was crucial for dune protection, which is consistent with the results of other authors [

7,

15].

In scenarios C7 to C9, at the model scale, an increase in the submerged bar volume resulted in an expansion of the berm width, indicating material deposition on the beach. However, in the prototype, continuous dune erosion was observed, suggesting that the equilibrium volume of the bar in the prototype exceeds the volume used in the model scale simulations. This highlights the inadequacy of model-scale simulations in accurately replicating real coastal system conditions ([

17]). Previous studies, such as those by [

18], suggest that the volume of the submerged bar can mitigate dune erosion, although with diminishing returns as the volume increases. The laboratory tests confirm that, although the increase in bar volume, as observed in scenarios C8 and C9, reduces dune erosion, this relationship is not linear. The analysis suggests that an optimized adjustment of bar volume could lead to more effective and cost-efficient solutions.

The CS-Model does not account for the shape of the submerged bar, relying solely on its volume. This limitation restricts the model's ability to accurately simulate the morphological interactions between waves, currents, and sediments, which are crucial for coastal evolution and dune protection ([

19]; [

3]). In the physical model, the shape of the submerged bar, in terms of height and width, also plays a key role in wave energy dissipation. [

18] highlights the importance of these factors, which is confirmed in this study. The results indicate that the difference between the water level and the height of the submerged bar affects energy dissipation, with the width of the bar becoming more significant in dune protection than its height, when this difference reaches 6 cm.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the morphological evolution of coastal profiles through physical and numerical modeling, with particular emphasis on the interaction between the beach, dune, berm, and submerged bar. Laboratory experiments and simulations using the CS-Model at both model and prototype scales were conducted to analyze how different configurations influence sediment dynamics and erosion patterns. The conclusions presented below synthesize the key findings and discuss their relevance to coastal management and future research.

Simulations of the CS-Model at the model scale resulted in dune retreat values lower than those obtained in simulations at the prototype scale, as evaluated by the berm position. For the assessment of the influence of berm width on dune erosion mitigation in the numerical simulations, it was observed that as berm width increased, the likelihood of dune erosion decreased. In evaluating the effect of the bar volume in the CS-Model simulations at the model scale, it was found that as the submerged bar volume increased, the position of the beach berm increased. This behavior is explained by the fact that the 35 cm³/cm volume is greater than the equilibrium bar volume in the CS-Model at the model scale. Therefore, for this numerical model, whenever the initial bar volume exceeds the equilibrium bar volume, the bar volume decreases, and this material moves toward the beach, increasing the beach width. On the other hand, in the three scenarios of the submerged bar volume study at the prototype scale, dune erosion was always observed. It is important to note that the equilibrium volume of the submerged bar in the prototype is approximately 409 cm³/cm, while the volumes considered in the studied scenarios were lower. In this situation, an increase in the bar volume was observed, leading to the material moving towards the submerged bar, resulting in beach and dune erosion. The CS-Model only considers the bar volume, making this parameter independent of the shape and position of the submerged bar. Thus, for the same submerged bar volume, the result obtained is always the same.

It was observed that in all the laboratory tests conducted, the highest profile variation rates, resulting in accretion on the bar and erosion in the upper part of the profile, occurred during the first 60 seconds, with changes exceeding 40% of the total morphological variation recorded at the end of the test. In evaluating the effect of the water surface level in the physical model, it was found that, although there was a difference of 3.67 x 10-3 m³/m in bar volume between scenario C1 and C0, with C1 corresponding to a water surface height of 11 cm, greater erosion of the upper part of the beach occurred in the C1 scenario at the end of the test. However, a higher rate of dune erosion variation was recorded for scenario C0, while scenario C2 exhibited a lower rate of dune erosion variation. Thus, it can be concluded that the lower the water surface height, the less likely the wave climate will cause dune erosion, provided the profile is subjected to the same wave conditions. Regarding the evaluation of berm width influence in mitigating dune erosion, it was found that the wider the berm, the lower the chances of dune erosion occurring, as the beach width contributes to wave energy dissipation. When the width is sufficient to dissipate wave energy, no dune erosion occurs, and only a reduction in berm width is observed, as confirmed in scenarios C5 and C6. For the evaluation of the bar volume in the laboratory, the scenarios suggest that increasing the submerged bar volume does not necessarily guarantee the best solution for mitigating dune erosion. However, increasing the bar volume results in less dune erosion, as seen in the results from scenarios C8 and C9. The relationship between bar volumes and dune erosion reduction is not linear, which suggests that studying the bar volume for dune erosion mitigation could lead to a more optimized artificial nourishment project, requiring fewer financial resources. In the study of the submerged bar shape during the laboratory tests, it was observed that for the same bar volume, when the difference between the water surface level and the submerged bar height is at least 3 cm (scenario C10), the height of the submerged bar becomes more crucial in dissipating wave energy. If this difference exceeds 6 cm (scenario C8), the width of the bar becomes more important than the height of the bar, leading to improved dune erosion mitigation. Therefore, scenario C11, with a 3 cm submerged bar height, yielded better results in dune shape preservation than scenario C8, which had a height of 6 cm.

In conclusion, the laboratory tests showed that artificial nourishment involving submerged bar volume were more effective at mitigating dune erosion than those focused on increasing berm width. Notably, only scenario C11 fully preserved the dune. These findings may offer valuable preliminary guidance for future artificial nourishment projects, contributing to more effective and sustainable coastal management.

References

- Larson M, Palalane J, Fredriksson C, Hanson H. Simulating cross-shore material exchange at decadal scale. Theory and model component validation. Coastal Engineering 2016; 116: 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Marinho B, Coelho C., Larson M, Hanson H. Simulating cross-shore evolution towards equilibrium of different beach nourishment schemes. Proceedings of Coastal Dynamics 2017, 2017, 15.

- Masselink G, Hughes M, Knight J. Introduction to Coastal Processes and Geomorphology. Routledge, 2014.

- Roelvink D, Reniers A, van Dongeren A, van Thiel de Vries J, McCall R, Lescinski J. Modelling storm impacts on beaches, dunes and barrier islands. Coastal Engineering 2009; 56: 1133–1152.

- DHI. MIKE 21. User manual. DHI Water & Environment, 2012.

- Guimarães A, Coelho C, Veloso-Gomes F, Silva PA. 3D Physical Modeling of an Artificial Beach Nourishment: Laboratory Procedures and Nourishment Performance. J Mar Sci Eng 2021; 9: 613. [CrossRef]

- Marinho B. Artificial nourishments as a coastal defense solution: monitoring and modelling approaches (PhD Thesis). 2018.

- Larson M, Erikson L, Hanson H. An analytical model to predict dune erosion due to wave impact. Coastal Engineering 2004; 51: 675–696. [CrossRef]

- Fisher JS, Overton MF, Chisholm T. Field Measurements of Dune Erosion. Coastal Engineering 1986, American Society of Civil Engineers 1987, 1107–1115.

- Nishi R, Kraus N. Mechanism and calculation of sand dune erosion by storms. Proceedings of the 25th Coastal Engineering Conference, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 1996; 3034–3047.

- Larson M, Donnelly C, Jiménez JA, Hanson H. Analytical model of beach erosion and overwash during storms. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Maritime Engineering 2009; 162: 115–125.

- Vale D, Pires R. Avaliação do Espraiamento e Galgamento em Estruturas Costeiras. 2022.

- Coelho C. Riscos de exposição de frentes urbanas para diferentes intervenções de defesa costeira (PhD Thesis, in Portuguese). 2005.

- van Rijn LC, Tonnon PK, Walstra DJR. Numerical modelling of erosion and accretion of plane sloping beaches at different scales. Coastal Engineering 2011; 58: 637–655.

- Puleo JA, Lanckriet T, Conley D, Foster D. Sediment transport partitioning in the swash zone of a large-scale laboratory beach. Coastal Engineering 2016; 113: 73–87. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira AM, Coelho C, Silva PA. Medium-Term Effects of Dune Erosion and Longshore Sediment Transport on Beach–Dune Systems Evolution. J Mar Sci Eng 2024; 12: 1083. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn LC, Tonnon PK, Sánchez-Arcilla A, Cáceres I, Grüne J. Scaling laws for beach and dune erosion processes. Coastal Engineering 2011; 58: 623–636. [CrossRef]

- Borsje BW, van Wesenbeeck BK, Dekker F et al. How ecological engineering can serve in coastal protection. Ecol Eng 2011; 37: 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Chun I, Lim HS, Shim JS, Park KS. Numerical Analysis of the Performance of Perforated Coastal Structures under Irregular Wave Conditions. J Coast Res 2015; 315: 1159–1169. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Cross-shore profile scheme in the CS-Model [

7].

Figure 1.

Cross-shore profile scheme in the CS-Model [

7].

Figure 2.

Diagram of dune erosion and overtopping processes, adapted from [

7].

Figure 2.

Diagram of dune erosion and overtopping processes, adapted from [

7].

Figure 3.

Hydraulic flume of the Civil Engineering Department (University of Aveiro, Portugal).

Figure 3.

Hydraulic flume of the Civil Engineering Department (University of Aveiro, Portugal).

Figure 4.

Wave generation mechanism.

Figure 4.

Wave generation mechanism.

Figure 5.

Ultrasonic sensor for water level measurement.

Figure 5.

Ultrasonic sensor for water level measurement.

Figure 6.

Profile of the reference scenario, at the prototype scale.

Figure 6.

Profile of the reference scenario, at the prototype scale.

Figure 7.

Schemes of the evaluated scenarios.

Figure 7.

Schemes of the evaluated scenarios.

Figure 8.

Final berm position as a function of the water level (scenarios C0 to C2).

Figure 8.

Final berm position as a function of the water level (scenarios C0 to C2).

Figure 9.

Evolution of the berm position over time, for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the berm position over time, for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 10.

Berm width as a function of the initial width.

Figure 10.

Berm width as a function of the initial width.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the berm width over time, in scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the berm width over time, in scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 12.

Evaluation of the volume of the submerged bar in the physical model.

Figure 12.

Evaluation of the volume of the submerged bar in the physical model.

Figure 13.

Evolution of the berm width and position over time in the CS-Model, for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 13.

Evolution of the berm width and position over time in the CS-Model, for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 14.

Evolution of the berm width and position over time in the CS-Model, for scenarios C8, C10 and C11.

Figure 14.

Evolution of the berm width and position over time in the CS-Model, for scenarios C8, C10 and C11.

Figure 15.

Final profile morphology for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 15.

Final profile morphology for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 16.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 16.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C0 to C2.

Figure 17.

Final position of the berm depending on the water level.

Figure 17.

Final position of the berm depending on the water level.

Figure 18.

Evolution of the berm position, for scenarios C0 to C2, over time.

Figure 18.

Evolution of the berm position, for scenarios C0 to C2, over time.

Figure 19.

Profile morphology at the end of the laboratory tests, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 19.

Profile morphology at the end of the laboratory tests, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 20.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 20.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 21.

Berm width, as a function of initial berm width.

Figure 21.

Berm width, as a function of initial berm width.

Figure 22.

Evolution of berm width over time, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 22.

Evolution of berm width over time, for scenarios C0 and C3 to C6.

Figure 23.

Profile morphology at the end of the test, for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 23.

Profile morphology at the end of the test, for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 24.

Variation in depth and position of the bar over time for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 24.

Variation in depth and position of the bar over time for scenarios C0 and C7 to C9.

Figure 25.

Evaluation of the submerged bar volume in the laboratory model.

Figure 25.

Evaluation of the submerged bar volume in the laboratory model.

Figure 26.

Profile morphology at the end of the test, for scenarios C8, C10, and C11.

Figure 26.

Profile morphology at the end of the test, for scenarios C8, C10, and C11.

Figure 27.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C8, C10, and C11.

Figure 27.

Variation of bar depth and position over time, for scenarios C8, C10, and C11.

Table 1.

Beach profile parameters, common to all scenarios.

Table 1.

Beach profile parameters, common to all scenarios.

| H0(cm) |

T (s) |

YL (cm) |

YS (cm) |

βL (°) |

βS (°) |

βF (°) |

S (cm) |

| 5 |

1.48 |

10 |

40 |

18.33 |

13.75 |

26.56 |

3.75 |

Table 2.

Defined scenario and beach profile parameters, at the physical model scale.

Table 2.

Defined scenario and beach profile parameters, at the physical model scale.

| Scenarios |

YB (cm) |

DB (cm) |

DC (cm) |

VB0 (cm3/cm) |

| C0 |

40.00 |

5.50 |

12.00 |

0.00 |

| C1 |

40.00 |

6.50 |

11.00 |

0.00 |

| C2 |

7.50 |

10.00 |

| C3 |

50.00 |

5.50 |

12.00 |

0.00 |

| C4 |

62.50 |

| C5 |

75.00 |

| C6 |

87.50 |

| C7 |

40.00 |

5.50 |

12.00 |

35.00 |

| C8 |

115.30 |

| C9 |

196.00 |

| C10 |

40.00 |

5.50 |

12.00 |

115.30 |

| *C11 |

Table 3.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in profile volumes, for scenarios C0 to C2 of the laboratory tests.

Table 3.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in profile volumes, for scenarios C0 to C2 of the laboratory tests.

| Test |

Time

(minutes) |

Volume |

Differences |

Erosion

(x10-3m3/m) |

Bar

(x10-3m3/m) |

Absolute1

(x10-3m3/m) |

Relative2

(%) |

C0 |

1 |

5.09 |

6.35 |

1.27 |

24.88 |

| 2 |

8.56 |

9.36 |

0.80 |

9.35 |

| 3 |

9.56 |

10.67 |

1.11 |

11.61 |

| 4 |

9.71 |

11.32 |

1.61 |

16.58 |

| 5 |

10.12 |

11.31 |

1.19 |

11.76 |

| 6 |

10.86 |

11.53 |

0.66 |

6.08 |

C1 |

1 |

6.59 |

6.33 |

0.26 |

4.00 |

| 2 |

7.54 |

7.41 |

0.13 |

1.77 |

| 3 |

8.61 |

7.93 |

0.68 |

7.93 |

| 4 |

9.12 |

8.81 |

0.30 |

3.33 |

| 5 |

9.61 |

9.00 |

0.61 |

6.36 |

| 6 |

11.66 |

7.99 |

3.67 |

31.47 |

C2 |

1 |

5.63 |

5.41 |

0.22 |

3.95 |

| 2 |

6.52 |

6.05 |

0.47 |

7.24 |

| 3 |

6.93 |

6.97 |

0.04 |

0.54 |

| 4 |

7.31 |

7.16 |

0.14 |

1.95 |

| 5 |

8.15 |

7.40 |

0.74 |

9.11 |

| 6 |

8.09 |

7.85 |

0.24 |

2.99 |

Table 4.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in profile volumes, for scenarios C3 to C6 from the laboratory tests.

Table 4.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in profile volumes, for scenarios C3 to C6 from the laboratory tests.

Test |

Time

(minutes) |

Volume |

Differences |

Erosion

(x10-3m3/m) |

Bar

(x10-3m3/m) |

Absolute1

(x10-3m3/m) |

Relative2

(%) |

C3 |

1 |

7.35 |

8.13 |

0.79 |

10.69 |

| 2 |

9.03 |

9.26 |

0.23 |

2.56 |

| 3 |

9.73 |

9.59 |

0.13 |

1.38 |

| 4 |

10.25 |

10.09 |

0.15 |

1.50 |

| 5 |

11.19 |

10.31 |

0.87 |

7.81 |

| 6 |

11.53 |

10.68 |

0.85 |

7.40 |

C4 |

1 |

11.66 |

9.72 |

1.94 |

16.63 |

| 2 |

12.40 |

10.40 |

2.00 |

16.12 |

| 3 |

12.66 |

10.94 |

1.72 |

13.58 |

| 4 |

12.68 |

11.08 |

1.60 |

12.60 |

| 5 |

13.25 |

11.09 |

2.16 |

16.29 |

| 6 |

13.30 |

10.90 |

2.40 |

18.03 |

C5 |

1 |

6.63 |

7.64 |

1.01 |

15.15 |

| 2 |

7.63 |

8.80 |

1.17 |

15.27 |

| 3 |

8.37 |

9.15 |

0.79 |

9.38 |

| 4 |

8.50 |

9.31 |

0.82 |

9.59 |

| 5 |

9.02 |

10.07 |

1.06 |

11.70 |

| 6 |

9.54 |

10.56 |

1.02 |

10.64 |

C6 |

1 |

7.27 |

7.12 |

0.15 |

2.06 |

| 2 |

9.25 |

8.42 |

0.83 |

8.97 |

| 3 |

9.89 |

10.13 |

0.24 |

2.43 |

| 4 |

10.74 |

10.33 |

0.41 |

3.82 |

| 5 |

11.41 |

10.54 |

0.87 |

7.62 |

| 6 |

11.44 |

10.75 |

0.69 |

6.03 |

Table 5.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in the volumes on the profile, for scenarios C7 to C9 of the laboratory tests.

Table 5.

Erosion and accretion volumes, as well as the absolute and relative differences in the volumes on the profile, for scenarios C7 to C9 of the laboratory tests.

Test |

Time

(minutes) |

Volume |

Differences |

| Erosion (x10-3m3/m) |

Bar

(x10-3m3/m) |

Absolute1

(x10-3m3/m) |

Relative2

(%) |

C7 |

1 |

4.02 |

3.22 |

0.80 |

19.89 |

| 2 |

4.68 |

3.56 |

1.12 |

23.92 |

| 3 |

5.18 |

4.02 |

1.16 |

22.39 |

| 4 |

5.22 |

3.88 |

1.34 |

25.66 |

| 5 |

5.50 |

4.42 |

1.08 |

19.63 |

| 6 |

5.49 |

4.61 |

0.88 |

16.03 |

C8 |

1 |

1.90 |

2.03 |

0.13 |

7.00 |

| 2 |

2.53 |

2.74 |

0.20 |

8.01 |

| 3 |

2.83 |

3.46 |

0.62 |

22.00 |

| 4 |

2.81 |

3.39 |

0.58 |

20.46 |

| 5 |

2.94 |

3.85 |

0.91 |

30.78 |

| 6 |

3.28 |

3.93 |

0.66 |

19.97 |

C9 |

1 |

2.55 |

2.23 |

0.32 |

12.72 |

| 2 |

2.68 |

2.28 |

0.39 |

14.76 |

| 3 |

2.99 |

2.58 |

0.41 |

13.87 |

| 4 |

3.18 |

2.91 |

0.27 |

8.64 |

| 5 |

3.32 |

3.03 |

0.29 |

8.87 |

| 6 |

3.30 |

3.13 |

0.17 |

5.29 |

Table 6.

Test |

Time

(minutes) |

Volume |

Differences |

| Erosion (x10-3m3/m) |

Bar

(x10-3m3/m) |

Absolute1

(x10-3m3/m) |

Relative2

(%) |

C10 |

1 |

1.12 |

1.59 |

0.47 |

41.56 |

| 2 |

1.67 |

2.31 |

0.65 |

38.75 |

| 3 |

2.43 |

3.19 |

0.77 |

31.54 |

| 4 |

2.49 |

3.54 |

1.05 |

41.95 |

| 5 |

2.47 |

3.70 |

1.22 |

49.52 |

| 6 |

2.76 |

3.88 |

1.13 |

40.84 |

C11 |

1 |

0.65 |

0.95 |

0.30 |

45.69 |

| 2 |

1.06 |

1.15 |

0.09 |

8.93 |

| 3 |

1.06 |

1.25 |

0.19 |

17.63 |

| 4 |

1.03 |

1.29 |

0.27 |

26.00 |

| 5 |

0.97 |

1.28 |

0.31 |

31.64 |

| 6 |

0.89 |

1.32 |

0.44 |

49.27 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).