1. Introduction

Domestic animals, particularly ruminants such as cattle, are continuously challenged by the ambient environment. Among environmental stressors, heat stress stands out as one of the most deleterious, especially under the current climate change trajectory, which predicts increase in both mean temperatures and frequency of extreme heat events. Heats stress may be defined as the sum of external and internal forces that act on an animal to raise its body temperature beyond its thermoregulatory capacity and elicit compensatory physiological responses [

1]. In bovine production systems, thermal stress may compromise productivity, health and welfare, especially in tropical and subtropical zones or during heat waves [

1,

2].

Unlike many wild species, livestock cannot freely migrate away from adverse conditions; instead, their survival and performance depend on their capacity to maintain homeothermy within narrow limits. When ambient thermal load exceeds certain thresholds (upper critical temperature), the animal must activate heat dissipation mechanisms to reduce metabolic heat production and improve heat losses by pathways such as evaporation, conduction, convection and radiation, and if those are overwhelmed, heat stress ensues [

3]. In cattle, interactions among ambient temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, wind speed and management (shade, water sprinkling, housing) determine the effective thermal load on the animal [

4]. In practice, expression of heat stress is often asynchronous across individuals: breed, age, body condition, production stage (lactation, gestation), coat colour and prior acclimatisation modulate vulnerability [

5].

Heat stress is not merely a discomfort; it initiates a complex cascade of physiological adaptations that, in chronic or severe form, may lead to tissue damage, immune suppression, reproductive failure, increased morbidity, and even mortality [

6]. Thus, a robust theoretical grounding is essential if one is to monitor, manage or breed for thermotolerance in cattle systems. Therefore, the objective of this communication is to highlight key physiological responses to heat stress and emphasize the importance of monitoring thermoregulatory markers

2. Key Physiological Responses to Heat

When an animal is exposed to rising ambient heat load, a hierarchical set of responses is mobilized to preserve core temperature. These may be classified into behavioral, autonomic/physiological, endocrine/metabolic, and cellular/molecular levels. This section will focus on analyzing the physiological and metabolic levels, as they are fundamental to thermoregulation.

The thermal balance equation posits that core body heat gain (from metabolism + environmental radiation) must equal heat loss (via conduction, convection, radiation, evaporation) for stable body temperature. Under heat stress, evaporative routes (panting, sweating) become dominant, whereas conductive/convective/radiative losses may be insufficient or reversed (i.e., net heat gain) [

4,

7]. In cattle, cutaneous vasodilatation increases blood flow to peripheral dermal vessels, enhancing convective and conductive heat loss to the environment [

8]. In cattle, cutaneous vasodilatation increases blood flow to peripheral dermal vessels, enhancing convective and conductive heat loss to the environment [

7,

9]. In addition, increased respiratory rate (tachypnoea) facilitates evaporative heat loss from the respiratory surfaces. To limit internal heat generation, cattle under heat stress tend to reduce feed intake (thus lowering metabolic heat increment), slow growth, and shift nutrient partitioning away from thermogenic processes [

9]. Thyroid hormones (triiodothyronine T3, thyroxine T4) often decline, reflecting a downregulation of the basal metabolic rate [

10]. Moreover, the efficiency of tissue metabolism is modulated so that mitochondrial activity may be altered to reduce inefficiencies that generate excess heat [

11]. In severe stress, animals may mobilize fat reserves, but this may generate additional metabolic heat or reactive oxygen species, complicating the trade-off between survival and damage.

To support increased peripheral blood flow and facilitate heat transfer, cardiac output may rise (via increased heart rate) to maintain perfusion pressure to central and peripheral tissues [

10]. Concurrently, blood is redistributed away from internal organs toward skin and respiratory surfaces, risking compromised perfusion of other tissues if prolonged. The respiratory system is co-opted for heat dissipation: increased tidal volume, panting, and potentially hyperventilation is common [

12]. These shifts, however, come at a cost: altered blood gas balance, electrolyte shifts, respiratory alkalosis, and increased water loss.

Heat stress provokes activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) and catecholamines, which mediate metabolic shifts, immunomodulation, and energy reallocation, while cortisol also participates in feedback regulation of the HPA axis to fine-tune the stress response [

10]. In parallel, heat shock proteins (HSPs) -especially HSP70-are upregulated as molecular chaperones that mitigate protein denaturation and cellular stress [

13]. Other endocrine signals (e.g., prolactin, growth hormone, insulin/IGF, leptin) also modulate adaptation, especially in adjusting energy balance or appetite [

14]. Chronic stress may lead to endocrine desensitization or maladaptation, further impairing homeostasis.

At the cellular level, heat stress induces oxidative stress, cellular membrane disruption, protein misfolding and apoptosis if beyond repair thresholds. Upregulation of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase) and repair pathways is part of the adaptative response [

15]. Mitochondrial dysfunction may occur in extreme cases, impairing ATP production and exacerbating heat-related damage. In the reproductive system, heat stress may impair oocyte quality, embryo survival, spermatogenesis, and placental function through cellular stress pathways [

10].

Animals may undergo acclimation (physiological adjustment over days to weeks) in response to repeated heat exposure. For instance, sweating capacity may increase, circulatory adjustments become more efficient, and hormonal set points shifts [

16]. Genetic adaptation over generations may select for more heat-tolerant genotypes (e.g.,

Bos indicus vs

Bos taurus) with morphological or metabolic traits favoring heat dissipation (Lighter coat, less insulating subcutaneous fat, more skin surface, more efficient sweat mechanisms) [

17]. However, selection for high productivity may antagonize thermotolerance, creating a biological tension.

3. Thermoregulatory Markers (Indicators) of Heat Stress

To understand, monitor or select for heat resilience, one must identify reliable thermoregulatory indicators. Such markers can be core body temperature measures and surface temperature indices respiratory variables, blood or endocrine biomarkers, and behavioral/physiological composites.

3.1. Core Body Temperature Metrics and Surface and Skin Temperature Indices

Rectal temperature is perhaps the most classic index of core temperature, but it is invasive, subject to handling artefacts, and slow to reflect rapid changes [

18]. Alternatives include vaginal temperature, ruminal (reticulo-ruminal) temperature probes, tympanic (ear) sensors, and ingestible telemetric boluses. These approaches differ in response time, invasiveness, cost, and practicality [

19]. Telemetric boluses can provide continuous high-resolution internal temperature data, thereby capturing fluctuations and cumulative heat load better than point measurements.

Surface temperature of skin or extremities can be measured non-invasively via infrared thermography (IRT). This technology yields spatially resolved temperature maps and can detect “hot spots” indicative of vasodilatation or inflammation [

20]. Research in cattle indicates that IRT of the ocular region, Udder, flanks, and muzzle may correlate with core temperature or respiratory stress indicators [

21]. However, external surface temperatures are modulated by ambient variables (wind, solar load, coat, hair thickness), so calibration and threshold estimation are critical [

22].

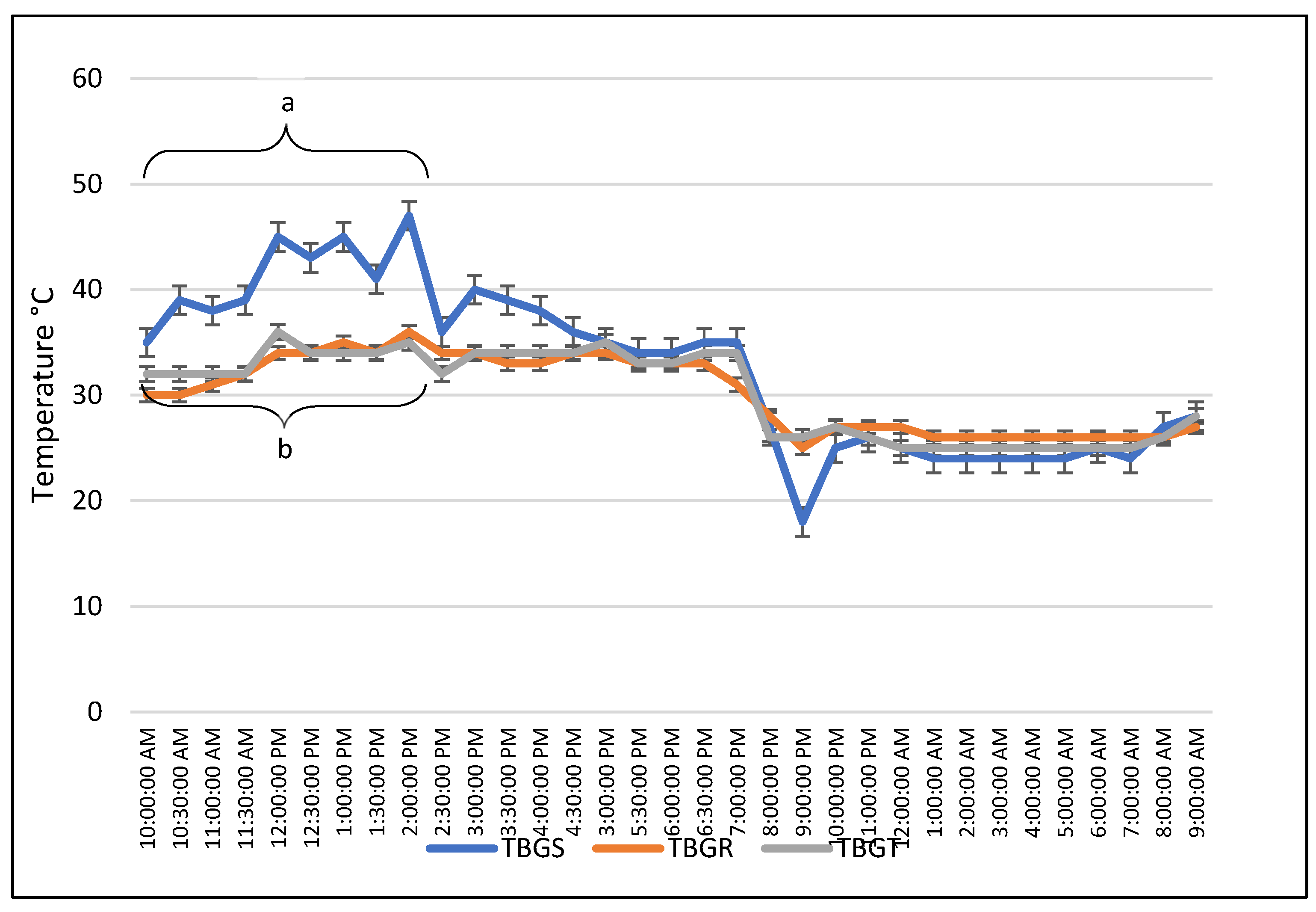

In an unpublished experiment conducted in the state of Tabasco, Mexico (tropical climate) in July (summer), a series of semi-circadian measurements of body temperature and 24-hour measurements of ambient temperature were taken. For this purpose, fifty adult females of the Bos indicus cows were used, and their rectal temperature was evaluated. The ambient temperature was measured using a black globe in the sun and in the shade, both in trees and under roof. In addition, the temperature was assessed using the thermometer bulb outdoors, outside the black globe (dry bulb), both in the sun and in the shade.

It was observed that the highest temperatures detected by the black globe in the sun were between 10:00 and 14:00 compared to the temperatures detected in the shade of a tree or under a roof (P<0.05). The latter did not differ during all measurements (P>0.05;

Figure 1).

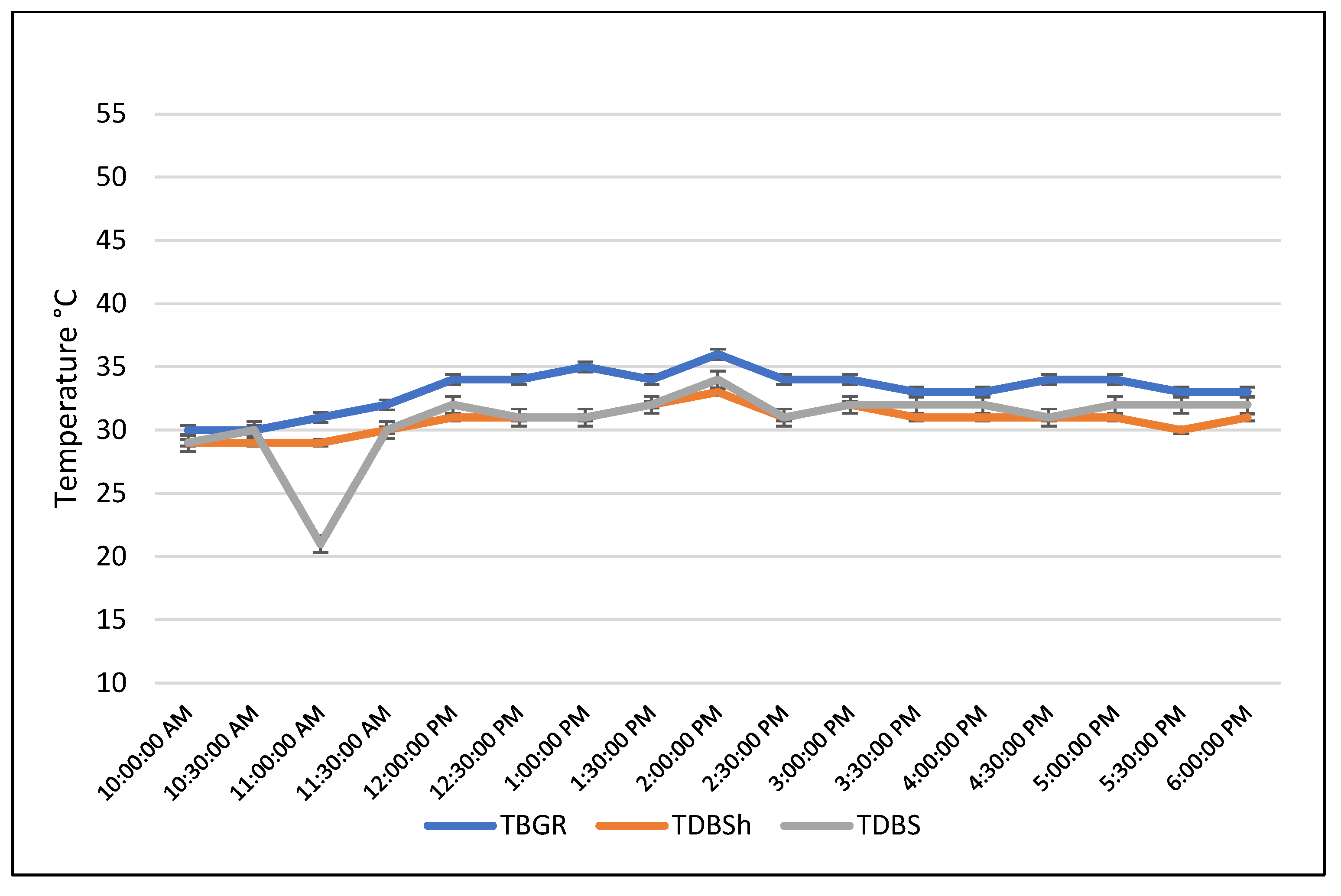

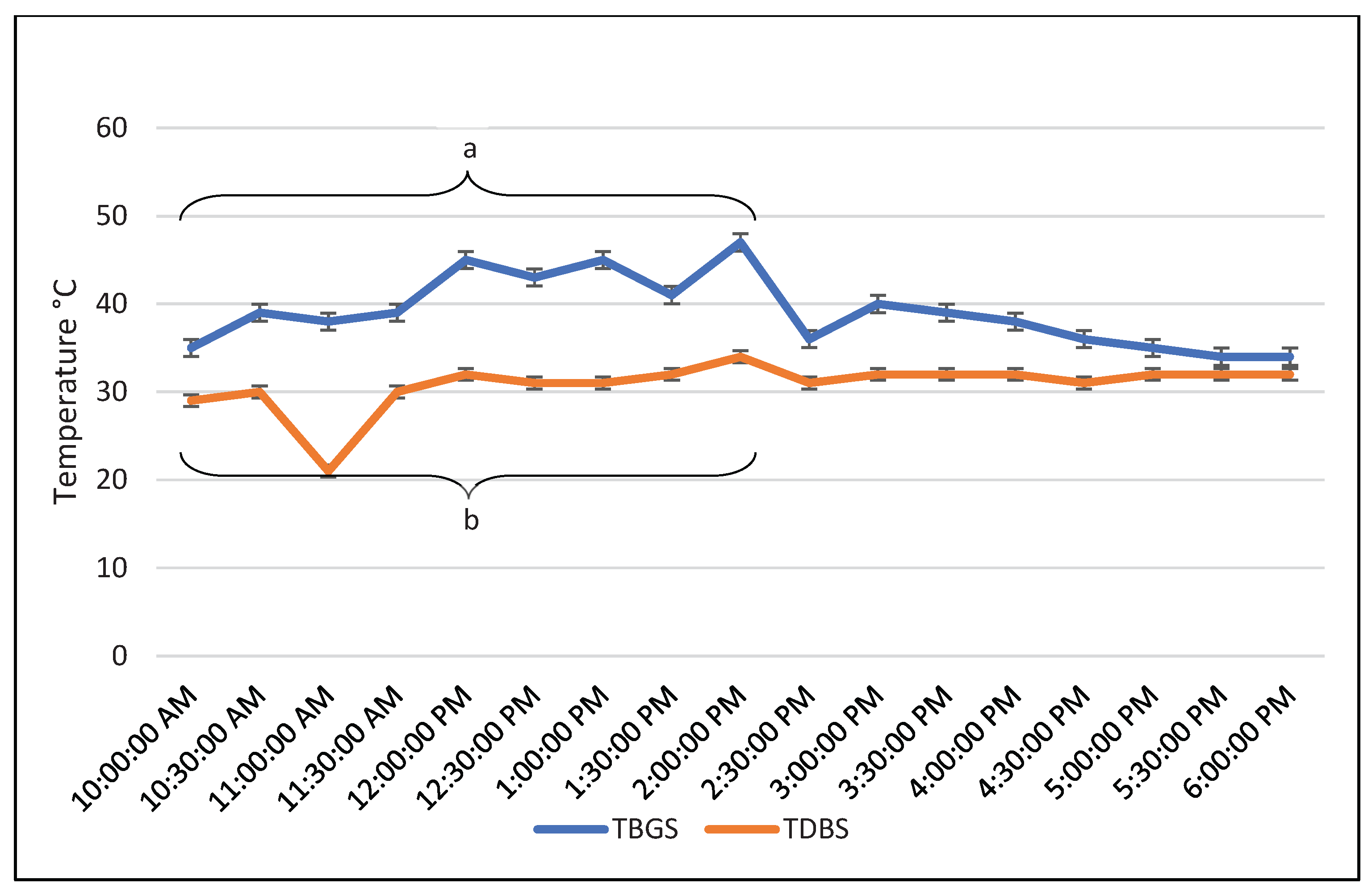

The temperatures detected by the black globe were not affected by wind and humidity (the globe isolated the thermometer bulb from these environmental factors). In contrast, the dry bulb measurements were affected by humidity and wind. Thus, it was observed that the temperature detected by the black globe indoors was similar to that evaluated by the dry bulb in the sun and in the shade (P>0.05;

Figure 2). On the other hand, when comparing the temperature detected by the black globe and the dry bulb in the sun, significant differences (P>0.05) are observed between 10:00 and 14:00 (

Figure 3).

Rectal temperatures varied depending on the time of day they were taken. In the morning (14 measurements between 9:00 and 11:00 a.m.), they averaged 38.73 °C ± 0.73. In contrast, in the afternoon (17 measurements between 13:00 and 14:00), they averaged 41.24 °C ± 2.0, which was significantly different (P=0.001). This would indicate that the animals’ temperature increased as the ambient temperature rose during the morning until 14:00 hrs. (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). In this experiment, it was observed how body temperatures are consistent with ambient temperatures and, in turn, how ambient temperatures need to be influenced by wind and humidity to be more conducive to adaptation by animals living in tropical areas.

3.2. Respiratory and Panting Variable

Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) is among the most frequently used animal-based physiological indicators of heat stress, because it responds rapidly to heat load [

23]. The panting score (a categorical scale of observed respiratory effort) is also used, especially in field settings, though it is subjective and lacks fine resolution [

24]. Changes in tidal volume or inspiratory/expiratory ratio may be informative but require more advanced instrumentation (e.g., pneumotachometers), often impractical in field systems.

3.3. Haematological and Blood Biomarkers

Blood biomarkers may reveal systemic stress beyond superficial thermoregulation. Elevated cortisol, glucose, non-esterified fatty acids, lactate, heat shock proteins (E.g., HSP70, HSP90), thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), and oxidative stress markers (e.g., malondialdehyde, antioxidant enzyme activities) have been proposed [

25]. Electrolyte disturbances (e.g., sodium, potassium, bicarbonate) may reflect compensatory renal or respiratory changes [

26]. Leukocyte counts and immune parameters may show suppressed function under chronic heat stress [

27]. However, blood sampling is invasive, may itself provoke stress, and provides only snapshots rather than continuous data.

3.4. Composite Indices and Derived Indicators

Because no single marker perfectly captures heat stress, researchers often use composite indices. Temperature-Humidity Index (THI) is the most widely used environmental index combining ambient temperature and relative humidity. Thresholds of THI (e.g., >68-74) have been proposed to fleg onset of heat stress in dairy cows. More refined indices incorporate radiant heat, wind speed, or animal-specific factors (e.g., Heat Load Index, Black Globe Humidity Index) [

28]. There is growing interest in animal-based indices integrating multiple physiological signals (e.g., combination of respiration rate, surface temperature, core temperature slope) to detect stress earlier and more sensitively [

29].

4. Monitoring Strategies and Practical Evaluation in Production Systems

Translating theoretical markers into practical, on-farm monitoring involves technical, economic, and logistical challenges. Optimised strategies are presented in this section.

Traditional monitoring relies on periodic manual measurements (rectal temperature, respiration counts, behavioural observation). While simple, this approach is labour-intensive, disruptive, and limited in temporal resolution. Advances in precision livestock farming allow automated, continuous monitoring of core or surface temperatures, respiration, or movement using sensors, wearable devices, and remote thermal cameras [

30]. Such systems enable early warning and individual-targeted interventions. However, costs, data processing needs, sensor robustness, and farm infrastructure remain barriers.

Effective use of thermoregulatory indicators requires establishment of baseline profiles (for given animals, breeds, production stages, and seasons) and thresholds for intervention. For example, the slope of respiration rate or body temperature versus THI has been used to classify heat-tolerant vs. heat-sensitive individuals [

31]. It is critical to adjust thresholds for local climate, breed coat, and housing conditions. Without calibration, many indicators produce false alarms or missed events. High-frequency continuous sampling can detect transient heat peaks that static measures miss. But trade-offs exist: battery life, data storage, and sensor drift. A mixed scheme (continuous core temperature logging plus periodic manual checks) may be optimal. Data smoothing, trend detection, and anomaly detection algorithms are essential to discriminate noise from real stress events.

Integrating animal-level data with microclimatic sensors (temperature, humidity, solar radiation, wind speed) allows modelling of effective heat load. Currently, data-driven predictive models—including machine learning—are emerging to forecast when animals will cross risk thresholds and trigger mitigation actions (e.g., activation of sprinklers or fans) [

32]. Such anticipatory control is more efficient than reactive response. Sensors must be validated (accuracy, calibration, drift), maintained, and robust to field conditions (dust, moisture, impact). Systems must also be user-friendly for farm staff. Data overload is real: many farms lack capacity for real-time analysis. Therefore, designing dashboards, alerts, and feedback loops is as important as sensor deployment. Cost-benefit analyses are indispensable to ensure interventions are economically justified.

5. Productive, Health and Welfare Implications of Heat Stress in Cattle

5.1. Productivity Impacts

In dairy cattle, heat stress reduces feed intake and milk yield, depresses milk fat and protein content, and impairs lactation persistence [

31]. In beef or growing animals, daily weight gain declines, feed conversion worsens, and carcass quality may be compromised [

32]. Reproductive performance also suffers: reduced oocyte quality, lower conception rates, early embryonic mortality, impaired placental function, altered luteal dynamics, disrupted oestrous expression, and sperm damage in males [

34]. These effects may persist beyond the heat episode, affecting the next lactation or pregnancy.

There is evidence that high temperature–humidity index (THI) values in cows during the final third of gestation can induce alterations in their postpartum reproductive physiology [

35] demonstrated that when animals are exposed to environments with a THI exceeding 76, both reproductive behavior and early postpartum ovarian activity are negatively affected. It is therefore essential to implement appropriate management strategies to mitigate heat exposure, such as providing shade, ensuring adequate access to drinking water, and using sprinklers to prevent the detrimental effects of heat stress on the animals.

Losses in production, increased disease management, higher mortality, increased water and energy consumption, infrastructure investment (cooling, shade, sprinklers), and labor all impose economic burdens. Without adaptation, climate change may render some production systems marginal or unviable in certain regions [

32]. There is also a trade-off: selecting for high yield may reduce resilience, leading to brittle systems vulnerable to heat extremes. Given these costs, breeding for thermotolerance is an important long-term strategy. Traits linked to heat resilience (e.g., lower slope of temperature vs. THI, efficient sweating, lighter coat, better heat shock response) can be included in selection indices [

1]. However, one must balance selection for productivity and resilience; ignoring one leads to fragility.

5.2. Health, Immune Function and Disease Susceptibility

Heat stress depresses immune competence. Elevated cortisol and metabolic shifts suppress leukocyte function, cytokine responses, and vaccination efficacy, increasing disease susceptibility (mastitis, respiratory infections, enteric disorders) [

6,

13]. Gastrointestinal integrity may be compromised via altered rumen motility, higher risk of acidosis, and dysbiosis under feed intake. Water and electrolyte imbalance can provoke dehydration and renal stress. In extreme cases, heat stroke, organ failure, and mortality may occur [

6,

13].

Welfare is compromised when animals are unable to maintain comfort, autonomy, or normal behavior. Heat-stressed cattle often stand more (to increase convective heat loss), reduce lying time, alter feeding and rumination patterns, and increase panting or drooling [

6]. Chronic stress predisposes to behavioral disorders, and prolonged discomfort reduces quality of life, even if productivity is maintained.

6. Conclusions

Physiological adaptations and thermoregulatory indicators of heat stress in bovine systems represent a rich but complex field at the intersections of animal physiology, environmental science and precision livestock farming. Heat stress provokes a cascade of responses-from vascular dilation, panting, metabolic depression, endocrine shifts, to cellular stress mechanisms- that are necessary to maintain homeostasis but carry costs. No single indicator suffices: core temperature probes, surface thermography, respiratory rates, hormonal biomarkers and composite indices must be integrated within a monitoring framework. Practical implementation demands sensor robustness, calibration, data analytics, and cost-effective mitigation strategies.

Heat stress imposes substantive penalties on milk yield, growth, reproduction, health and welfare, threatening economic viability and ethical standards in cattle systems. To mitigate these effects, farms should adopt real-time monitoring, anticipatory cooling, shade/water systems, and breed for resilience. As global temperatures rise, understanding and applying the framework of thermoregulatory adaptation in cattle becomes not merely academic but existential for many production systems.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institutional Subcommittee for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals(DC-2015/2-8 2015-02-08).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to sincerely thank MV Daniela Alvaracin. for her collaboration in the review of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- West, J.W. Effects of heat-stress on production in dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 2003, 86, 2131–44.

- Collier, R.J, Gebremedhin, K.G. Thermal biology of domestic animals. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 2014, 1, 513–32. [CrossRef]

- Renaudeau, D.; Collin, A.; Yahav, S., de Basilio, V.; Gourdine, J.L.; Collier, R.J. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal 2012, 707–28. [CrossRef]

- Lees, A.M.; Sejian, V.; Wallage, A.L.; Steel, C.C.; Mader, T.L.; Lees, J.C.; Gaughan, J.B. The Impact of Heat Load on Cattle. Animals 2019, 9, 322. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves Titto C, Khan IM, Khan MZ, Umer S, Guilherme S, Gonçalves C, et al. Heat tolerance, thermal equilibrium and environmental management strategies for dairy cows living in intertropical regions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Dahl GE, Tao S, Laporta J. Heat Stress Impacts Immune Status in Cows Across the Life. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R.; Maloney, S.K. A review of thermal stress in cattle. Australian Veterinary Journal 2023, 101, 417-429. [CrossRef]

- Jian W, Ke Y, Cheng L. Physiological responses and lactation to cutaneous evaporative heat loss in Bos indicus, Bos taurus, and Their Crossbreds. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2015, 28, 1558–64. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Heat stress on calves and heifers: A review. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2020, 11, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Țogoe, D.; Mincă, N.A. The Impact of Heat Stress on the Physiological, Productive, and Reproductive Status of Dairy Cows. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2024, 14, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Acevedo AS, Hood R, Collier RJ, Skibiel AL. Graduate student literature review: Mitochondrial response to heat stress and its implications on dairy cattle bioenergetics, metabolism, and production. J Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 8351-8365. [CrossRef]

- Burhans, W.S.; Rossiter, C.A., Baumgard, L.H. Invited review: Lethal heat stress: The putative pathophysiology of a deadly disorder in dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 2022, 105, 3716-35. [CrossRef]

- Rakib, M.R.H.; Messina, V.; Gargiulo, J.I.; Lyons, N.A.; Garcia, S.C. Graduate Student Literature Review: Potential use of HSP70 as an indicator of heat stress in dairy cows—A review. Journal of Dairy Science 2024, 107, 11597–610. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Li, L.; Ouyang, K.; Qu, M.; Qiu, Q. Deciphering Heat Stress Mechanisms and Developing Mitigation Strategies in Dairy Cattle: A Multi-Omics Perspective. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2025, 15, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Tufarelli, V.; Colonna, M.A.; Losacco, C.; Puvača, N. Biological Health Markers Associated with Oxidative Stress in Dairy Cows during Lactation Period. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sejian V, Bhatta R, Gaughan JB, Dunshea FR, Lacetera N. Review: Adaptation of animals to heat stress. Vol. 12, Animal. Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. S431–44. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F ul.; Nawaz, A.; Rehman, M.S.; Ali, M.A.; Dilshad, S.M.R.; Yang, C. Prospects of HSP70 as a genetic marker for thermo-tolerance and immuno-modulation in animals under climate change scenario. Animal Nutrition 2019, 5, 340-50. [CrossRef]

- Vickers LA, Burfeind O, von Keyserlingk MAG, Veira DM, Weary DM, Heuwieser W. Technical note: Comparison of rectal and vaginal temperatures in lactating dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2010, 93, 5246-51. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J., Lin, Y.C. A review study on environmental heat stress and heat load management in the dairy cattle under climate change. Taiwan Livestock Res. 2024, 57, 124–41. 10.6991/JTLR.202406_57(2).0007.

- Alp Kağan Gürdil, G., Çağatay Selvi, K., Knížková Petr Kunc, I. Applications of infrared thermography in animal production. J. of Fac. Of Agric. 2007, 22, 328-336. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298093153.

- Daltro D dos S, Fischer V, Alfonzo EPM, Dalcin VC, Stumpf MT, Kolling GJ, et al. Infrared thermography as a method for evaluating the heat tolerance in dairy cows. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 2017, 22, 374–83. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, G.; Schmidt, M.; Ammon, C.; Rose-Meierhöfer, S., Burfeind, O., Heuwieser, W., et al. Monitoring the body temperature of cows and calves using video recordings from an infrared thermography camera. Veterinary Research Communications 2013, 37,91–9. [CrossRef]

- Brown-Brandl TM, Eigenberg RA, Nienaber JA. Heat stress risk factors of feedlot heifers. Livest. Sci. 2006, 105, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Gaughan JB, Mader TL, Holt SM, Sullivan ML, Hahn GL. Assessing the heat tolerance of 17 beef cattle genotypes. International Journal of Biometeorology 2010, 54, 617–27. [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Cheng, J.B.; Shi, B.L.; et al. Effects of heat stress on serum cortisol, biochemical indices and heat shock proteins in dairy cows. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 999–1008. [CrossRef]

- Bernabucci, U.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Nardone, A. Influence of body condition score on relationships between metabolic status and oxidative stress in periparturient dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2017–2026. [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, J.B.; Rhoads, R.P.; VanBaale, M.J.; Sanders, S.R.; Baumgard, L.H. Effects of heat stress on energetic metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 644–655. [CrossRef]

- García-Ispierto, I.; López-Gatius, F.; Bech-Sabat, G.; Santolaria, P.; Yániz, J.L.; Nogareda, C.; De Rensis, F.; López-Béjar, M. Climate factors affecting conception rate of high producing dairy cows in northeastern Spain. Theriogenology 2007, 67, 1379–1385. [CrossRef]

- Arias, R.A.; Mader, T.L.; Escobar, P.C. Factores climáticos que afectan el desempeño productivo del ganado bovino de carne y leche. Arch. Med. Vet. 2008, 40, 7–22. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Hoffmann, G.; Ammon, C.; Amon, T. Critical THI thresholds based on the physiological parameters of lactating dairy cows. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102523. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, G.; Li, F.; Lin, H.; Jiao, H.; Han, H.; et al. Optimized machine learning models for predicting core body temperature in dairy cows: Enhancing accuracy and interpretability for practical livestock management. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14(18), 2724. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Thorup, V.M.; Kudahl, A.B.; Østergaard, S. Effects of heat stress on feed intake, milk yield, milk composition, and feed efficiency in dairy cows: A meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107(5), 3207–3218. [CrossRef]

- Summer, A.; Lora, I.; Formaggioni, P.; Gottardo, F. Impact of heat stress on milk and meat production. Anim. Front. 2019, 9(1), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Dovolou, E.; Giannoulis, T.; Nanas, I.; Amiridis, G.S. Heat stress: A serious disruptor of the reproductive physiology of dairy cows. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13, 1801. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.F.; Galina, C.S.; Aranda, E.M.; Aceves, L.A.; Gallegos, S.J.; Pablos, J.L. Effect of temperature–humidity index on the onset of postpartum ovarian activity and reproductive behavior in Bos indicus cows. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, e20190074. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).