1. Introduction

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a clinical finding that often leads to unnecessary antibiotic use, directly contributing to the potential development of antimicrobial resistance [

1]. According to the 2019 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines [

2], antibiotic treatment is only indicated for pregnant women and patients undergoing urological procedures. Conversely, in institutionalized elderly patients, routine treatment has shown no clinical benefit and is associated with an increased risk of adverse events [

3].

The clinical environment of the Emergency Departments (ED) is characterized by high patient volumes and time pressure, requiring rapid clinical decision-making in contexts of incomplete information and limited opportunities for reassessment. In fact, many patients are discharged with outpatient antibiotic prescriptions prior to the availability of the complete antibiogram, which typically require approximately 48 hours [

4]. This situation is further aggravated by high turnover among resident physicians and attending staff, which may compromise continuity of care and uniformity in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to infections [

5].

Approximately 27% of urine culture (UC) results correspond to ASB in elderly patients presenting to EDs [

6]. In these patients, clinical history-taking is often complex due to cognitive impairment and altered mental status at presentation [

3]. These factors may increase the number of microbiological diagnostic tests requested and complicate their clinical interpretation, leading to unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions and contributing to resistance increase in this population.

The primary objective of this article is to describe the impact of a program that included education and audit-feedback to reduce the inappropriate treatment of ASB in an ED.

2. Results

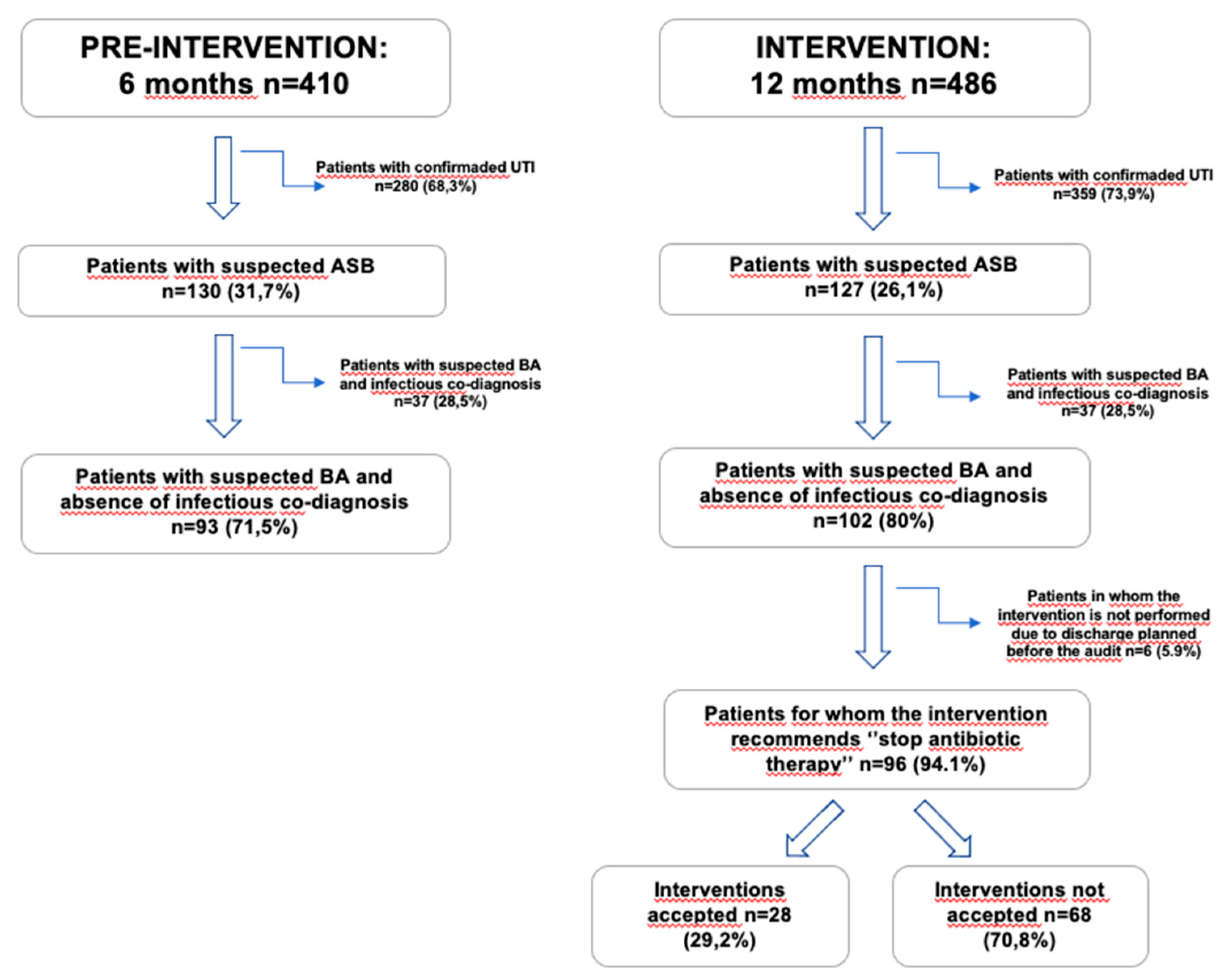

The total number of patients evaluated and included in both periods is represented on

Figure 1: total number of patients with antibiotics and confirmed urinary tract infection (UTI), patients with antibiotics and suspected ASB with and without an infectious co-diagnosis, the number of “stop antibiotic therapy” interventions in the intervention group, as well as the acceptance rate.

2.1. Data Collection

During the pre-intervention period, a total of 410 patients were identified, of whom 280 (68.3%) were excluded (they met UTI criteria), and 130 (31.7%) patients were classified as ASB. Among the 130 with suspected ASB, 93 (71.5%) had no associated infectious co-diagnosis, while 37 (28.5%) patients had a simultaneous infection from a source other than the urinary tract, being the most common exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with pulmonary infection criteria in 7 patients and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in 15 patients. In the intervention period, 486 patients were evaluated, with a total of 359 patients with UTI criteria (73.9%) and 127 (26.1%) patients meeting ASB criteria. Among the 127 with ASB, 102 (80%) had no simultaneous infectious diagnosis, whereas in 25 (20%) patients an associated infectious diagnosis was identified (6 with COPD exacerbation and 15 with CAP). In 96 patients (94.1%), discontinuation of antibiotic therapy was recommended and documented in the patient’s medical record. However, in 6 patients (5.9%), no recommendation was made because the patient was discharged with antibiotic prescription before the feed-back was made by the ED Pharmacists. The recommendation was accepted in 28 cases (29.2%) and not followed in 68 (70.8%). The main reason for not following the recommendation was that the patient’s therapeutic plan regarding outpatient antibiotic treatment had already been established and was linked to intermediate care centers, home hospitalization services and/or had been communicated to the patient and/or their family.

2.2. Description of the Sample of Patients with ASB

As mentioned above, a total of 257 patients with active antibiotics and suspected ASB were included during all the study period, 130 in the pre-intervention group and 127 in the intervention group. The demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age was similar between groups. A lower proportion of males was observed in the intervention group (7.09% vs. 25.38%, p-value <0.001). Regarding the proportion of patients with a Charlson index >6, this was higher in the pre-intervention group (16.2% vs. 7.1%, p-value = 0.02). In terms of comorbidities, a higher prevalence of heart failure was observed in the intervention group (24.6% vs. 9.5%, p-value <0.001). Clinically, there was a greater proportion of confusional syndrome in the pre-intervention group (92.3% vs. 23.7%, p-value <0.001).

2.3. Antibiotic Consumption

Table 2 shows the total consumption of antibiotics, carbapenems, and cephalosporins expressed in Defined Daily Dose (DDD)/1000 admissions per four-month period. Comparing the first four months of the two periods (2024 and 2025), we observe a decrease from 53.7 DDD/1000 admissions in 2024 to 46.9 in 2025, (-12.6%). A similar pattern was observed in the second quarters (Apr–Jun 2024 vs 2025), with a decrease from 51.8 to 40.9 (−21.0%) respectively. For the Jul–Sep of 2024 vs 2025 quarters total antibiotic consumption fell from 53.4 to 41.4 (−22.5%). In the fourth quarters (Oct–Dec), the reduction was: 56.5 in 2023 versus 45.7 in 2024 (−19.1%) with reduction of carbapenems from 9.2 to 7.0 and cephalosporins from 35.6 to 28.2.

In subgroup analysis, carbapenems showed a reduction of 24.5% in the first quarter (from 9.8 to 7.4 DDD/1000 admissions) and 24.2% in the second (from 9.1 to 6.9). Cephalosporins decreased by 10.0% in the first quarter (from 36.9 to 33.2) and 22.3% in the second (from 35.9 to 27.9). Ertapenem use decreased by 34.6% in the first quarter (from 5.2 to 3.4) and 29.5% in the second (from 4.4 to 3.1). Finally, ceftriaxone showed decreases of 10.2% in the first quarter (from 32.2 to 28.9) and 21.8% in the second (from 30.8 to 24.1). In the third quarter (Jul–Sep), the downward trend continued: carbapenems decreased from 9.2 to 7.0 (−23.9%), cephalosporins from 35.6 to 28.2 (−20.8%), ertapenem from 4.4 to 3.1 (−29.5%), and ceftriaxone from 31.6 to 24.4 (−22.8%). In the fourth quarter, carbapenems decreased from 10.1 to 7.9 (−21.8%), cephalosporins from 37.4 to 29.6 (−20.9%), ertapenem from 4.6 to 3.5 (−23.9%), and ceftriaxone from 32.8 to 25.7 (−21.6%).

2.4. Number of Urine Analysis Requests and Urine Cultures

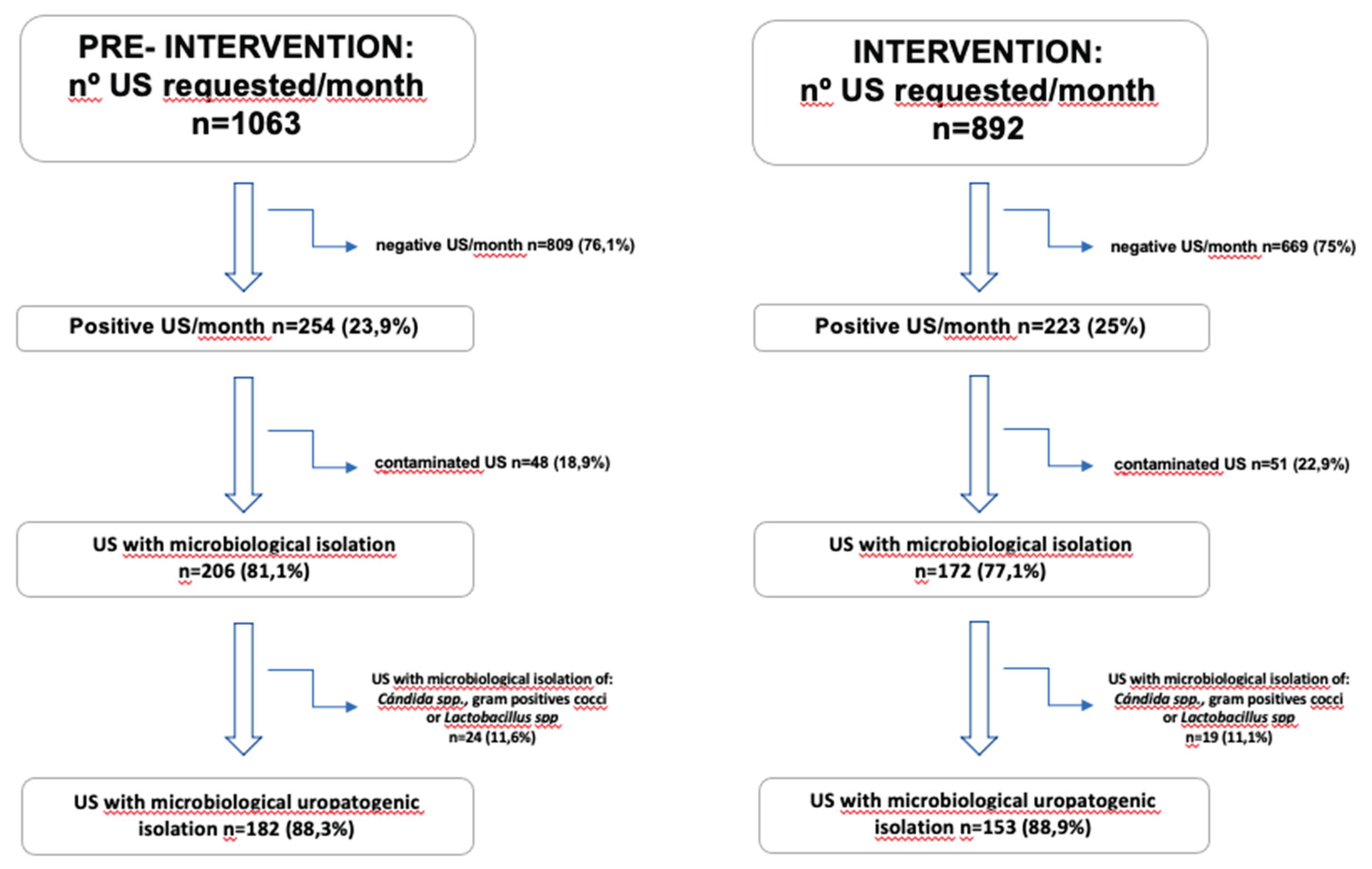

Figure 2 presents a flowchart with the monthly number of UC requests during the pre-intervention (6 months) and intervention (12 months) periods. Following the intervention, there was a 16.1% reduction in the total number of monthly samples processed, decreasing from an average of 1,063 to 892 cultures per month. Negative samples decreased by 17.3% per month, and positive samples decreased by 12.2%, while total microbiological isolates decreased by 16.5%. There was a reduction in isolates considered non-uropathogenic flora (including

Candida spp., Gram-positive cocci, and commensal flora), with a monthly reduction of 20.8%. Finally, isolates considered uropathogenic decreased by 15.9% per month after the intervention, consistent with the overall reduction in positives. When comparing both groups, a decrease in the total number of UC requests per month was observed.

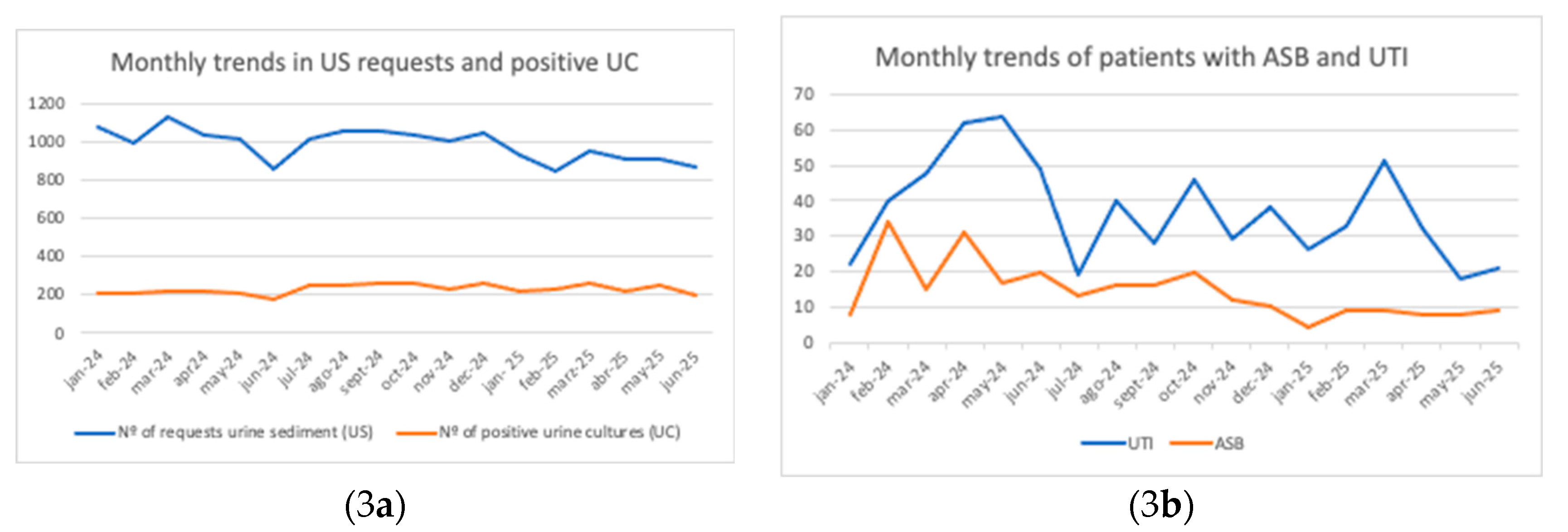

Figure 3 shows the monthly evolution of the number of UC requests and positive cultures (

Figure 3a), as well as patients with ASB and UTI (

Figure 3b) between January 2024 and June 2025. In

Figure 3a, UTI cases (blue line) display marked variability, with peaks in May 2024 and March 2025, while ASB cases (orange line) remain stable with a downward trend over time. In

Figure 3b, UTIs are more frequent, with peaks in May 2024 and March 2025, whereas ASB cases remain fewer in number and show a declining trend.

2.5. Clinical Outcomes

During the pre-intervention phase, 11 patients (8.5%) with ASB were discharged with outpatient antibiotics and returned to the ED for UTI, of whom 8 (6.2%) with the same isolate. Eight patients (6.2%) died within 30 days. Only two of them had returned with a UTI caused by the same isolate, and neither death was attributable to infection, but rather to complications or progression of chronic underlying disease.

During the intervention phase, 6 patients (4.7%) with ASB returned to the ED, 2 (1.6%) of them with the same isolate, and 5 (3.9%) died within 30 days, none due to infection. The 30-day mortality causes for both periods are detailed in the footnote of

Table 3. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups in 30-day UTI revisits with the same isolate (6.2% vs. 1.6%, p=0.103), overall UTI revisits (8.5% vs. 4.7%, p=0.316), or 30-day mortality (6.2% vs. 3.9%, p=0.571).

3. Discussion

As other pharmacist-led programs have attempted to reduce antibiotic prescribing in ASB by only education [

7], our study evaluated the impact of implementing an educational and audit-feedback strategy to reduce antimicrobial overtreatment of ASB in the ED. A later post-intervention phase, conducted without ongoing recommendations, aimed to evaluate the sustainability of antibiotic consumption patterns achieved during the intervention period.

The intervention was associated with a reduction in antibiotic prescribing among patients with ASB, decreased overall antimicrobial consumption, and a decline in the number of unnecessary urinalysis and UC, without compromising clinical outcomes such as ED return visit to the EDs for UTI or 30-day infection-related mortality. Although the acceptance of direct recommendations to discontinue antibiotic therapy was low (

Figure 1), antimicrobial consumption (

Table 2), the number of urinalysis requests (

Figure 3a), and the incidence of ASB diagnoses (

Figure 3b) progressively declined during the intervention period.

With regard to the study population, both groups had comparable demographic profiles, consisting predominantly of older, multimorbid, and female patients—similar to populations described in previous studies [

8]. However, during the intervention phase, patients presented with a lower burden of comorbidity, which may have resulted in less severe conditions upon ED admission and a greater window of opportunity before initiating antibiotic therapy. Clinically, the intervention group also exhibited lower rates of confusional syndrome due to a decrease in the routine ordering of US tests for these patients. This improvement in clinical assessment, combined with targeted education and daily audit-feedback, likely supported more precise diagnoses and a reduction in unnecessary empirical antibiotic prescribing. While no statistically significant differences were observed between groups for COPD or CAP, other infectious syndromes were significantly less frequent in the intervention group (11.5% vs. 3.1%). These findings suggest that the program contributed to more accurate infectious diagnoses in the ED and to reduced empiric antibiotic use in nonspecific presentations, such as confusional syndrome in frail elderly patients with ASB.

A major finding of this study was the low acceptance rate (29.2%) of “stop antibiotic therapy” recommendations. Several factors such as perceived clinical risk, the lack of patient follow-up after discharge, and the high-pressure environment of rapid decision-making likely hindered uptake of deprescribing recommendations. ED prescribers often prioritize immediate safety and broad-spectrum coverage in complex scenarios, particularly under substantial workloads. These results contrast with previous antimicrobial stewardship programs in EDs, such as that of Zhang et al. [

9], which reported a 93.3% acceptance rate, most commonly for narrowing antibiotic coverage rather than discontinuation of antibiotics. The timing of pharmacist reviews may have also influenced acceptance rates. They usually prioritize patients requiring urgent attention, such as those with sepsis or septic shock. That would explain that in many cases, the therapeutic plan for ASB patients had already been established before pharmacist evaluation, particularly in patients discharged to other intermediate care facilities, home hospitalization, or nursing homes for outpatient intravenous therapy (e.g., ceftriaxone or ertapenem), being difficult to discontinue the antibiotic. In addition, for inpatients who remained in the ED, antibiotics were often initiated by the attending physician the day prior, making it challenging to reassess decisions with the initial prescriber the previous day. Overall, the low acceptance of recommendations observed in this study underscores persistent barriers to effective ASP implementation in the ED. These include therapeutic inertia, concerns about patient safety, high physician turnover, and restricted capacity for post-discharge monitoring. Addressing these challenges will require targeted educational interventions, stronger adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines, and the promotion of an institutional culture that supports rational antibiotic use and deprescribing practices within the emergency care environment.

Despite the low acceptance of individual recommendations, the program’s impact was evident in the sustained reduction in ASB and UTI diagnoses over time (

Figure 3b). This effect can be attributed to the initial educational sessions conducted at the start of the intervention phase and reinforced through daily audit-feedback reviews by the pharmacy team. We compared consumption by quarters to avoid bias due to seasonal variation in infections, as CAP is more frequent in winter, whereas in summer UTIs tend to predominate over other infections [

10,

11]. The most pronounced reduction in antibiotic consumption, however, was observed in the final trimester of the intervention period (Apr–Jun 2025) and the post-intervention quarter (Jul-Sep 2025), suggesting that feedback-based audits had a stronger cumulative effect than the initial training sessions. This delayed but progressive improvement is consistent with the complexity of changing prescribing behaviors, as education alone is rarely sufficient to alter ingrained clinical practices. Notably, even when direct recommendations were not accepted, prescribers received reinforcement on appropriate antibiotic use, which likely contributed to subsequent improvements during the following months. The sustained reduction in antimicrobial use highlights an important outcome beyond cost savings and adverse event prevention: its role in combating antimicrobial resistance. Particularly noteworthy is the decrease in ceftriaxone use, a key driver of selective pressure on multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, especially extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains as Rodríguez-Baño has showed [

12].

The intervention also improved diagnostic stewardship. The reduction in overall urinalysis and UC requests, along with fewer negative or non-uropathogen-positive cultures, suggests more judicious use of diagnostic resources specially in patients with confusional syndrome. These findings align with previous studies [

13] demonstrating the benefits of educational interventions in reducing unnecessary UC requests, especially in institutionalized or chronically catheterized populations [

14,

15]. The lower frequency of non-uropathogenic isolates (e.g.,

Candida spp., Gram-positive cocci, commensal flora) further indicates improved sampling practices by nursing staff, reflecting an indirect benefit of the program on overall care quality.

From a clinical outcomes perspective, the program demonstrated safety: there was no increase in return visit to the ED for UTI or in 30-day mortality. In fact, return visit to the EDs for UTI with the same microbiological isolate decreased in the intervention group (6.2% vs. 1.6%), suggesting that withholding antibiotics in AB does not increase the risk of recurrence with the same pathogen. Similarly, overall UTI return visit to the ED (8.5% vs. 4.7%) and 30-day mortality (6.2% vs. 3.9%) were lower in the intervention period. These trends, though not statistically significant, are consistent with the established evidence that antibiotic treatment of ASB provides no clinical benefit while promoting adverse effects and antimicrobial resistance [

2,

12].

4. Materials and Methods

We conducted a quasi-experimental study in the ED of a tertiary hospital with 650 beds in Barcelona, Spain, serving approximately 140,000 ED visits per year, between January 2024 and June 2025.

The six-month pre-intervention period (January–June 2024) consisted of the observational-prospective phase. During this period, all ED patients with a diagnostic suspicion of UTI and an active antibiotic prescription were reviewed, and those who met ASB criteria according to the IDSA guidelines [

2] were selected. Patients were identified through the daily review of antibiotic prescriptions by the ED Pharmacists using the electronic prescribing system. The electronic health record was reviewed. Patients with positive US who met diagnostic criteria for UTI (fever, urinary symptoms such as incontinence, dysuria, urgency or frequency, or flank pain) and/or had an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP>50 mg/L), and/or leukocytosis (>12,000 cells/μL) without another suspected infectious diagnosis were excluded, as they were considered that may really have an UTI. We based these criteria on the objective diagnostic scale for UTI [

17]. On the contrary, patients without diagnostic criteria for UTI, and positive US were considered as potential candidates with ASB and were included. Patients with and elevated CRP>50 mg/L, and/or leukocytosis >12,000 cells/μL, and a co-diagnosis of another infection (e.g., COPD exacerbation, pneumonia) that justified elevated inflammatory markers were also included and considered as possible ASB, when there were no UTI symptoms and the US was positive. Demographic, clinical, and comorbidity data were recorded too. No interventions or clinical recommendations were performed during this phase.

The 12-month intervention period (July 2024–June 2025) included an initial educational phase and a subsequent audit-feedback phase. The education phase lasted for two weeks and consisted of sessions delivered to ED prescribers and nursing staff by the Antimicrobial Stewardship team. Updated therapeutic guidelines and recent scientific evidence on ASB were reviewed, along with the potential application of these guidelines in the ED, the criteria for ordering US by nursing staff, and results from the pre-intervention phase. Sessions were scheduled across different days and shifts to maximize attendance. The audit-feedback lasted for 12 months: The Antimicrobial Stewardship team led by a Pharmacist continued daily structured review of active antibiotic prescriptions initiated within the previous 24 hours in ED patients with suspected UTI. For patients with possible ASB and active antibiotic therapy, case-by-case audit-feedback was provided directly to prescribers. If no exclusion criteria or alternative infection requiring antibiotics were identified, antibiotic discontinuation was recommended. All recommendations, prescriber acceptance or rejection, and reasons for rejection were recorded.

There was also a post-intervention phase corresponding to the third quarter of 2025 (Jul-Sep), in which no audits or feedback were performed, with the aim of assessing whether the reduction in antimicrobial consumption patterns was sustained over time without intervention.

The primary outcome was 30-day return visit to the ED to the emergency department for UTI with the same microbiological isolate as the prior episode. Secondary outcomes included 30-day return visit to the EDs for new UTI episodes regardless of microbiological results, 30-day all-cause mortality, antimicrobial consumption expressed as DDD per 1,000 admissions. DDD/1,000 admissions is the unit of measurement that best reflects the reality of the ED for carbapenems and cephalosporins with daily dosing [

18,

19], and the number of UC requested from the ED. Antibiotic consumption was analyzed by comparing the first (Jan–Mar 2024), second (Apr–Jun 2024) and third (Jul-Sep 2024) quarters with the corresponding periods in 2025, the fourth quarter of 2024 with that of 2023 due to unavailable 2025 data.

Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages, and are compared using chi-square tests. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation using Student’s t-tests. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA, with significance set at p<0.05.

5. Limitations

Despite these positive outcomes, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study design did not allow for long-term follow-up beyond 30 days, limiting the evaluation of recurrent infections or delayed outcomes.Second, this was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings and reduce statistical power for rare outcomes. Third, during the post-intervention phase, due to limited human resources, neither daily audit-feedback nor educational sessions were conducted; consequently, data on the number of patients diagnosed with UTI and ASB, as well as on microbiological test requests, were not available. Finally, as an observational study, causality cannot be firmly established, although the temporal association and consistency with prior literature support the effectiveness of stewardship interventions in this setting. Additionally, unmeasured variations in overall ED patient volumes during the study period may have influenced results and represent a potential source of bias.

6. Conclusions

The implementation of an education and audit-feedback program in the ED significantly reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for asymptomatic bacteriuria, overall antimicrobial consumption, and unnecessary diagnostic testing, without compromising patient safety. Although direct acceptance of deprescribing recommendations was limited, the combined effect of initial training and sustained audit-feedback led to progressive improvements in prescribing practices. The marked reduction in ceftriaxone use is particularly important, given its role in driving antimicrobial resistance. Collectively, these findings support the safety of antibiotic deprescribing in AB and reinforce the value of educational interventions as a cornerstone strategy for optimizing antimicrobial use and mitigating resistance in ED settings.

Funding

This study has been funded by a 2024-2026 CAREer Grant from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) to Laura Escolà-Vergé.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (approval no. IIBSP-OAM-2022-86). As the intervention was part of a continuous quality improvement programme, individual informed consent was not required.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the PhD of Alvaro Monje ‘’Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Emergency Department’’.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ASB |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| UTI |

Urinary tract infection |

| ED |

Emergency department |

| DDD |

Daily Define Dose |

| UC |

Urine Culture |

| US |

Urine Sediment |

| CRP |

C Reactive Protein |

| CAP |

Community Acquired Pneumonia |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1188–94. [CrossRef]

- Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, Colgan R, DeMuri GP, Drekonja D, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):e83–e110. [CrossRef]

- Plasencia JT, Ashraf MS. Management of bacteriuria and urinary tract infections in the older adult. Urol Clin North Am. 2024;51(4):585–94. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramos J, Herrera-Mateo S, Rivera-Martínez MA, Monje-López AE, Hernández-Ontiveros H, Pereira-Batista CS, Martinez-Ysasis YM, Puig-Campmany M. Antimicrobial stewardship program in urinary tract infections due to multiresistant strains in the emergency department. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2023 Oct;36(5):486–491. [CrossRef]

- Singer AJ, Morley EJ, Henry MC. Managing infectious disease in the emergency department: challenges and opportunities. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(3):499–516. [CrossRef]

- Khawcharoenporn T, Vasoo S, Singh K. Abnormal urinalysis finding triggered antibiotic prescription for asymptomatic bacteriuria in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(7):828–30. [CrossRef]

- James D, Lopez L. Impact of a pharmacist-driven education initiative on treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Am J Health Syst Pharm [Internet]. 17 de mayo de 2019 [citado 3 de octubre de 2025];76(Supplement_2):S41-8. Disponible en: https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article/76/Supplement_2/S41/5373045.

- Henderson JT, Webber EM, Bean SI. Screening for Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1195–1205. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Rowan N, Pflugeisen BM, Alajbegovic S. Urine culture guided antibiotic interventions: A pharmacist driven antimicrobial stewardship effort in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Apr;35(4):594-598. Epub 2016 Dec 16. PMID: 28010959. [CrossRef]

- Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, Ampofo K, Bramley AM, Reed C, Stockmann C, Anderson EJ, Grijalva CG, Self WH, Zhu Y, Patel A, Hymas W, Chappell JD, Kaufman RA, Kan JH, Dansie D, Lenny N, Hillyard DR, Haynes LM, Levine M, Lindstrom S, Winchell JM, Katz JM, Erdman D, Schneider E, Hicks LA, Wunderink RG, Edwards KM, Pavia AT, McCullers JA, Finelli L; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372(9):835-845. PMID: 25714161; PMCID: PMC4697461. [CrossRef]

- Simmering JE, Polgreen LA, Cavanaugh JE, Erickson BA, Suneja M, Polgreen PM. Warmer Weather and the Risk of Urinary Tract Infections in Women. J Urol. 2021 Feb;205(2):500-506. Epub 2020 Sep 18. PMID: 32945727; PMCID: PMC8477900. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Baño J, Navarro MD. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in ambulatory care: a clinical perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008 Jan;14 Suppl 1:104-10. Erratum in: Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008 Mar;14(3):293. Ngugro, M D [corrected to Navarro, M D]. Erratum in: Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008 May;14 Suppl 5:21-4. PMID: 18154533. [CrossRef]

- Krouss M, Hsiung A, Wilson M, Puchalski J. Impact of Clinical Decision Support on Inappropriate Urine Culture Testing in the Emergency Department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2024;33(1):45–52.

- Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, Hysong SJ, Cadena J, Patterson JE, et al. Effectiveness of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach for Urinary Catheter–Associated Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120–7.

- Kellom K, Klapheke M, Perkins A, Van Hooser A, Malani PN. Reduction in urine cultures in long-term care through introduction of diagnostic stewardship. Am J Infect Control.

- Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Lador A, Sauerbrun-Cutler MT, Leibovici L. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD009534.

- A reference standard for urinary tract infection research: a multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study Bilsen, Manu PHooton, Thomas et al. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Volume 24, Issue 8, e513 - e521.

- Ruiz-Ramos J, Monje-López ÁE, Escolà-Vergé L, Herrera-Mateo S, Hernández-Ontiveros H, Duch-Llorach P, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial consumption indicators in the emergency department. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2025 May 22:S2529-993X(25)00130-3. [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Gil AB, Mejías-Trueba M, Peñalva G, Aguilar-Guisado M, Molina J, Gimeno A, Álvarez-Marín R, Praena J, Bueno C, Lepe JA, Gil-Navarro MV, Cisneros JM. Antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department observation unit: definition of a new indicator and evaluation of antimicrobial use and clinical outcomes. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024 Apr 12;13(4):356. PMID: 38667032; PMCID: PMC11047618. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).