1. Introduction

Most authors today agree that canalolithiasis originates from otolithic debris that migrates into a semicircular canal, where it moves freely, encountering resistance only from the endolymph and the canal walls. Accordingly, head movement along the appropriate plane can displace these fragments, generating endolymphatic currents that elicit transient, paroxysmal nystagmus [

1,

2,

3].

In contrast, the pathogenesis of cupulolithiasis—where debris adheres to the cupula, making it responsive to gravity—remains controversial. Schuknecht’s original hypothesis [

4] proposed that debris adheres directly to the cupula, but this has been questioned [

5], as experimental studies suggest the otoconial fragments do not possess adhesive properties of that magnitude [

6].

With the acceptance that otoconial debris may form a “jam,” a new question arises: could the phenomenon known as “cupulolithiasis” instead result from a mobile jam [

5]? In this scenario, the otolithic mass would be located in the ampulla and, following head movement, would either press against the cupula or obstruct the canal near its junction with the cupula, causing a sustained suction effect. Both conditions would produce apogeotropic nystagmus, consistent with the clinical features traditionally attributed to cupulolithiasis.

While this hypothesis is compelling, it remains unproven. It is also plausible that both mechanisms—true cupulolithiasis and mobile jams—exist independently.

The mobile jam theory offers a valuable framework to interpret non-paroxysmal positional vertigo. In this study, we aim—focusing exclusively on the horizontal canal—to evaluate the expected clinical signs depending on the topographic location of the debris within the canal. This approach yields purely theoretical predictions that can be compared against clinical data.

2. Materials and Methods

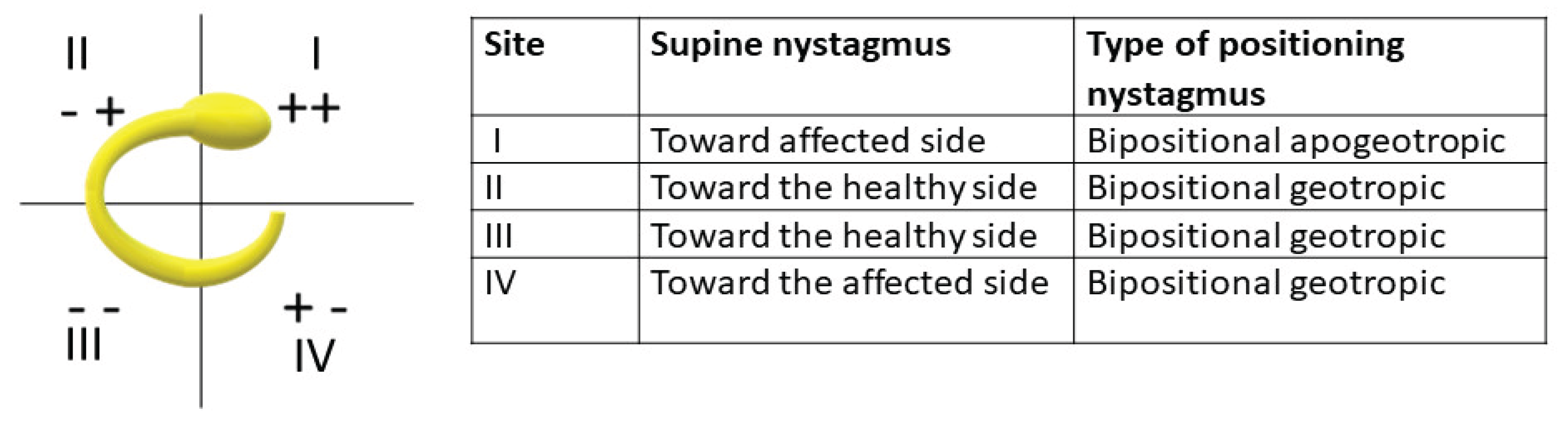

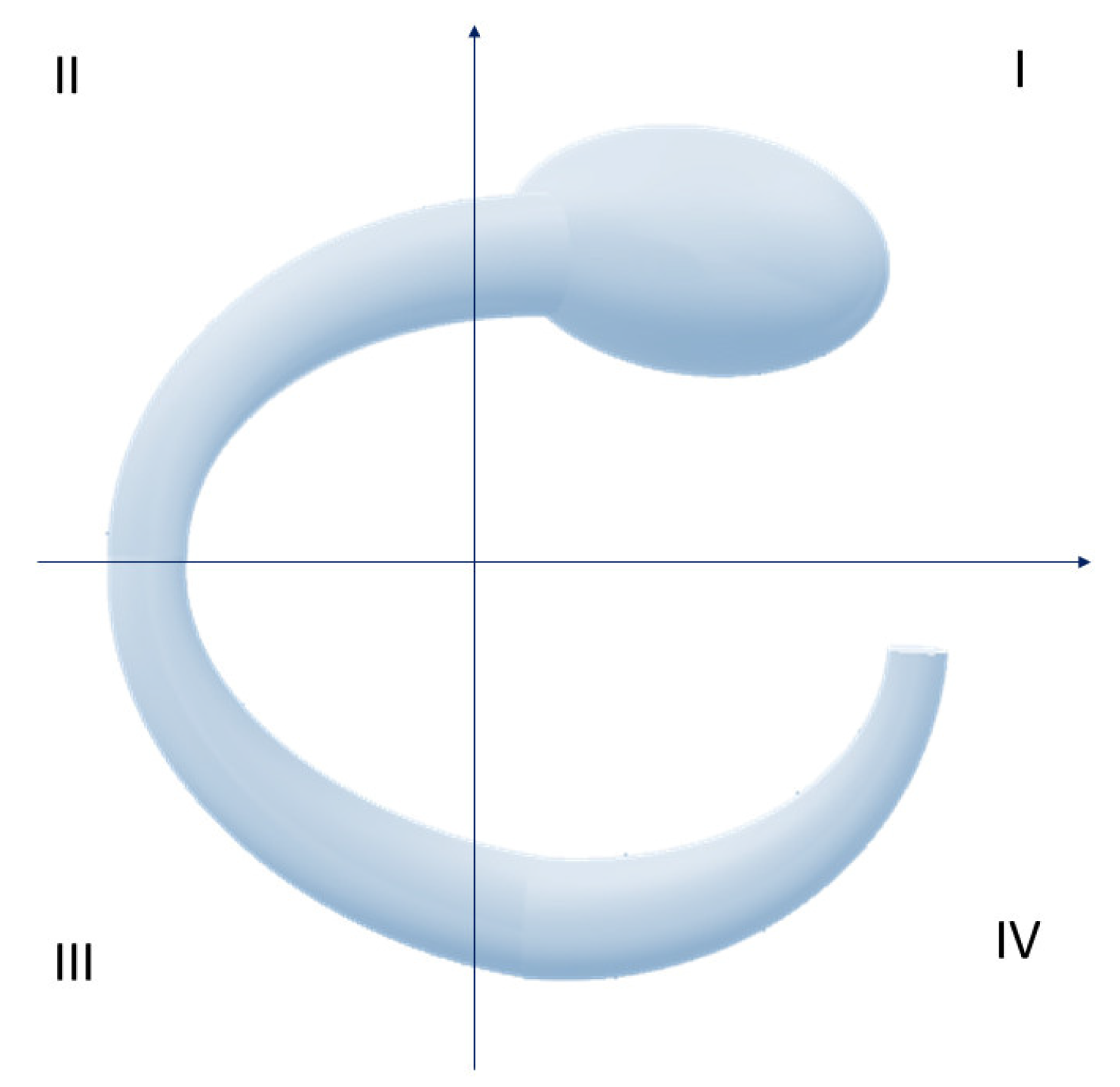

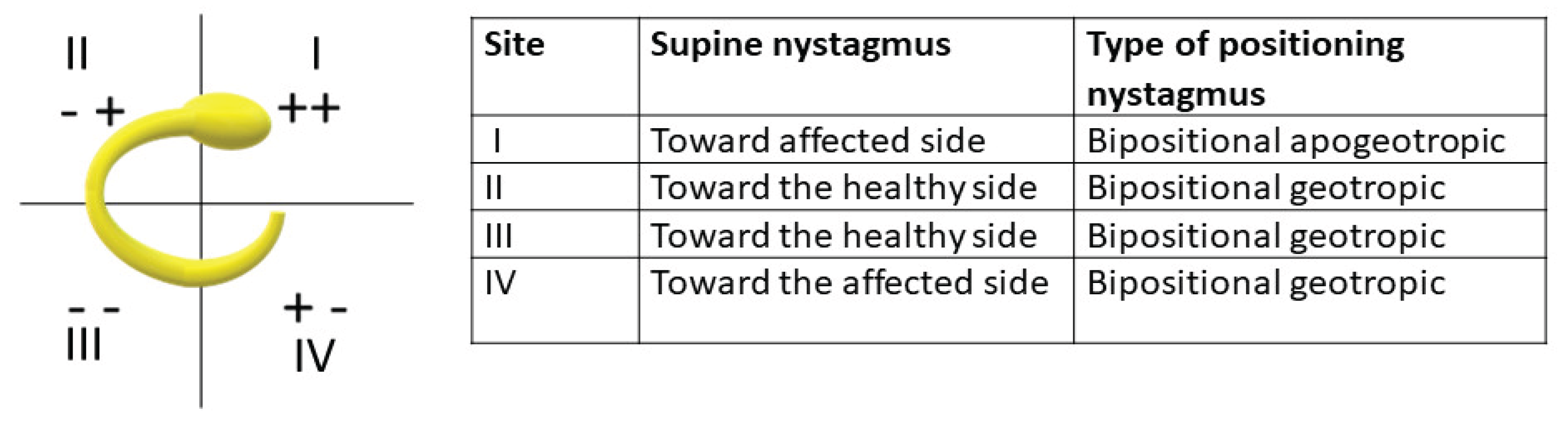

We considered the left lateral semicircular canal (findings are symmetrical for the contralateral side), visualized from above on a horizontal plane. The canal was divided into four quadrants using orthogonal Cartesian axes (

Figure 1):

Quadrant I: includes the ampulla and the ascending segment of the canal (positive X), up to its highest point;

Quadrant II: negative X and positive Y;

Quadrant III: negative X and negative Y;

Quadrant IV: positive X and negative Y, corresponding to the non-ampullary arm's entry into the utricle.

We assessed the effects of debris in each quadrant during key semiological maneuvers:a) transitioning to the supine position (clinostatism),b) head rotated to the right or left while supine.

This approach assumes that the patient is initially examined while sitting to assess for spontaneous nystagmus. The transition to a supine position is then evaluated for the onset, disappearance, or change in nystagmus.

We recorded the presence and direction of expected nystagmus based on the debris location at time t = 0.

To validate theoretical predictions, we analyzed a homogeneous cohort of patients diagnosed with geotropic and apogeotropic lateral canalolithiasis between 2009 and 2018. Cases with suspected central pathology or with indeterminate nystagmus laterality were excluded.

All patients underwent a comprehensive assessment including history, otoscopy, audiometry, spontaneous and evoked nystagmus testing (ocular and head-based), and positional maneuvers. Positional nystagmus was evaluated using the Dix-Hallpike test [

7] for the posterior canal and the Supine Roll Test (Pagnini-McClure maneuver) [

8] for the horizontal canal. Additional assessments included the Head Shaking Test, vestibulospinal reflexes, and caloric testing (Fitzgerald-Hallpike) with slow-phase velocity measured using Jongkees' formulas and recorded via video-oculography. More recently, some patients underwent video Head Impulse Test (video-HIT) and VEMP testing (cervical and ocular).

Out of 178 patients, 8 were excluded due to indeterminate nystagmus laterality. The final study population comprised 170 patients (95 females, 75 males; mean age 63 years, range 15–93). Patients with suspected central pathology underwent MRI with contrast, MR angiography, Doppler ultrasound of neck vessels, and neurological consultation.

Patients diagnosed with lateral canalolithiasis were treated with the Gufoni maneuver—on the affected side for apogeotropic forms, and on the healthy side for geotropic forms—followed by postural advice according to Vannucchi [

9].

3. Results

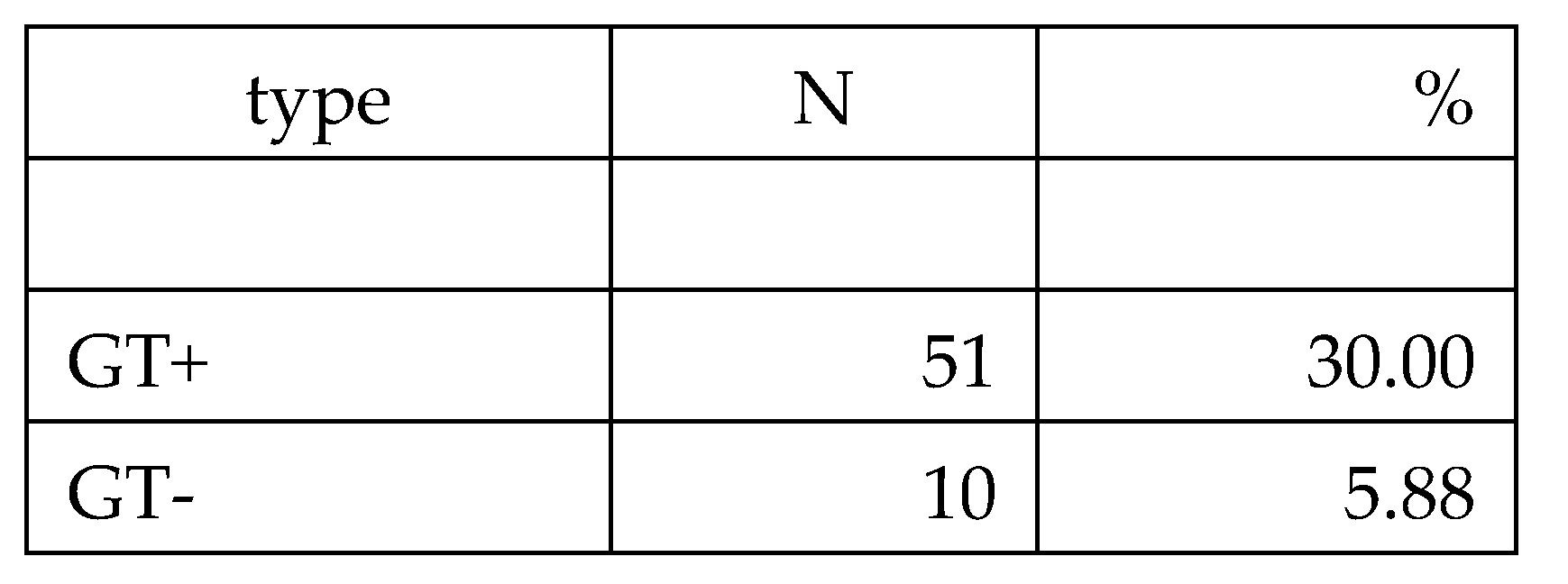

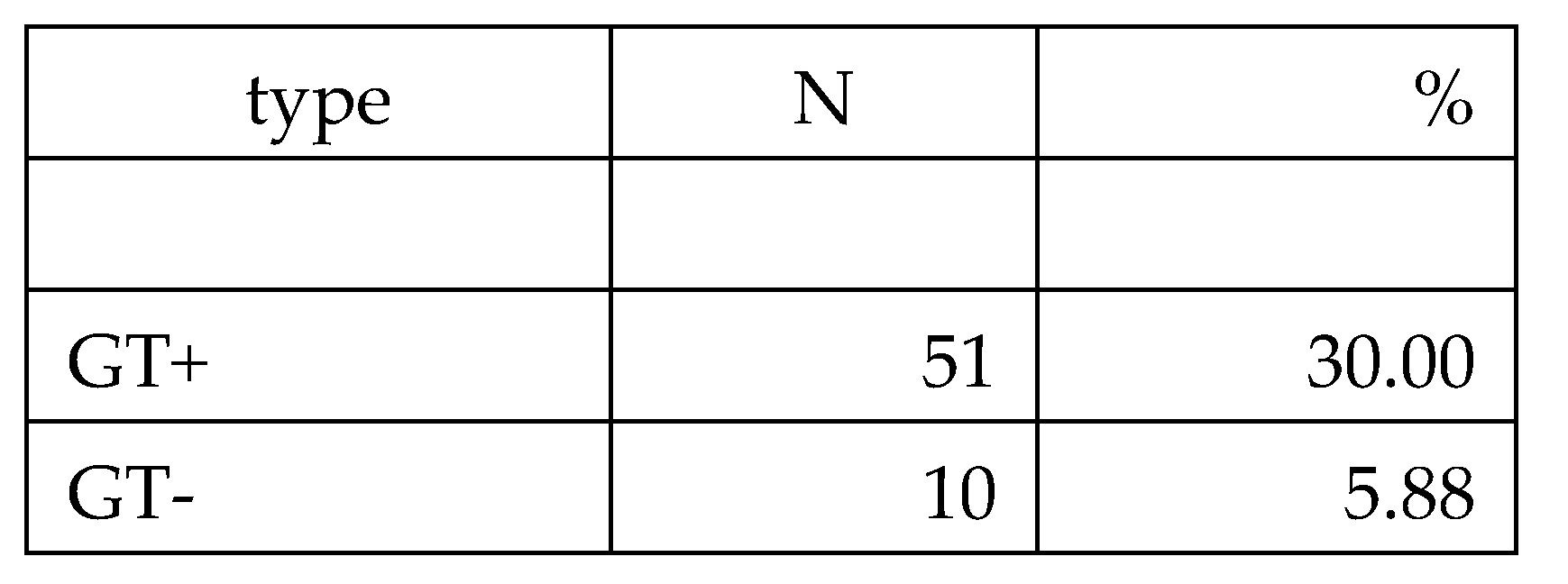

Findings for the 170 patients are summarized in Table 1. Among them, 141 cases were classified as geotropic, and 29 as apogeotropic.

Of the geotropic cases:

80 patients showed no nystagmus upon assuming the supine position but exhibited positional nystagmus when the head was rotated laterally (GT0).

51 patients had nystagmus directed toward the healthy side when supine (congruent nystagmus, GT+).

10 had nystagmus directed toward the affected side (incongruent nystagmus, GT−).

Of the apogeotropic cases:

10 showed no nystagmus at clinostatism but presented with positional nystagmus during lateral head rotation (AGT0).

16 had nystagmus directed toward the affected side (AGT+, congruent).

1 had nystagmus directed toward the healthy side (AGT−, incongruent).

2 patients exhibited monopositional apogeotropic nystagmus (mAGT) [

10].

In total, 90 out of 170 patients (approximately 53%) did not exhibit nystagmus upon assuming the supine position. This occurred more frequently in geotropic cases (80/141, ~57%) than in apogeotropic cases (10/29, ~34%). This difference is statistically significant (Yates-corrected p = 0.0474), suggesting that lying-down nystagmus is more common in geotropic variants.

Table 1.

4. Discussion

Based on theoretical modeling, we expect:

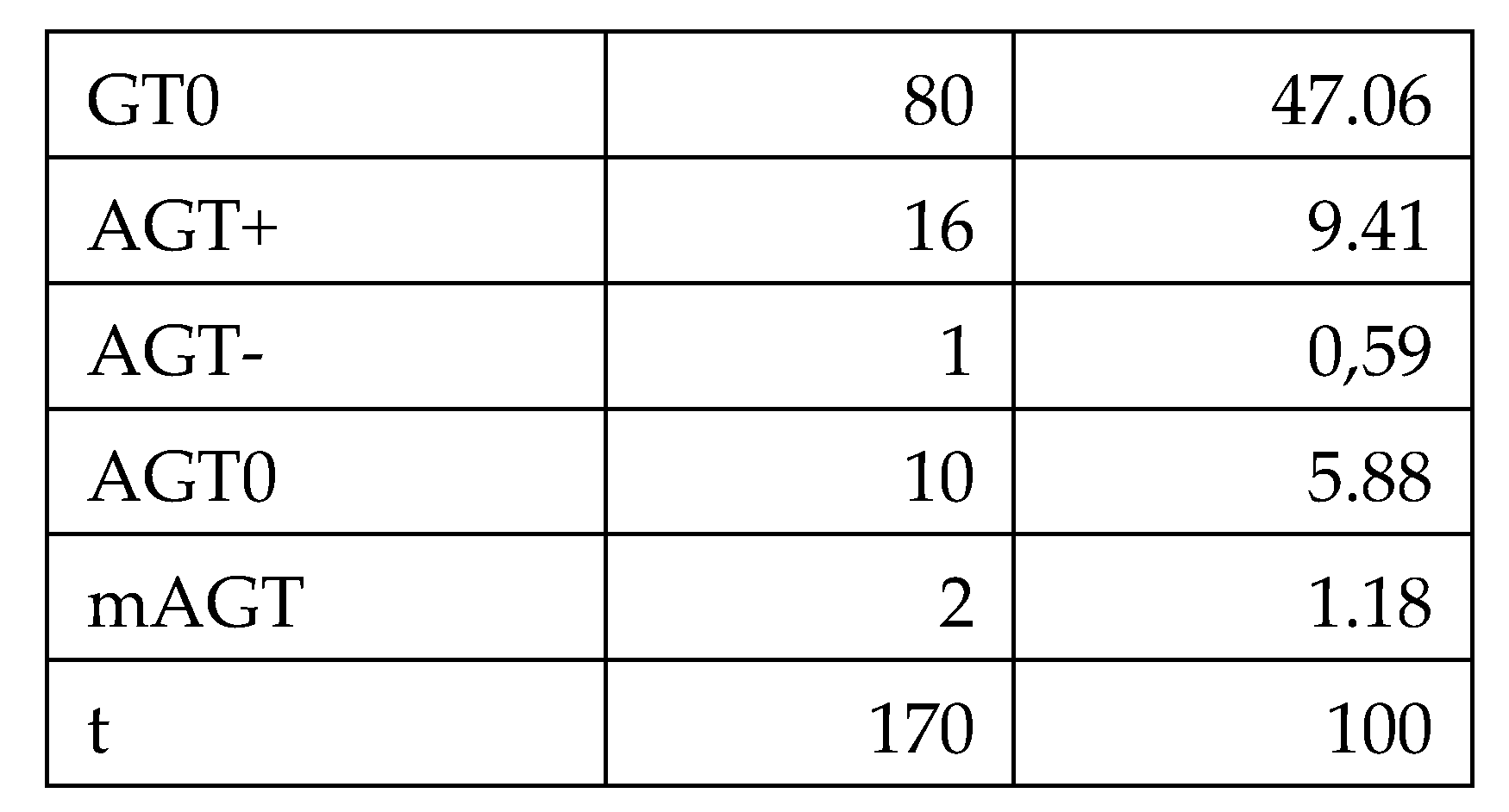

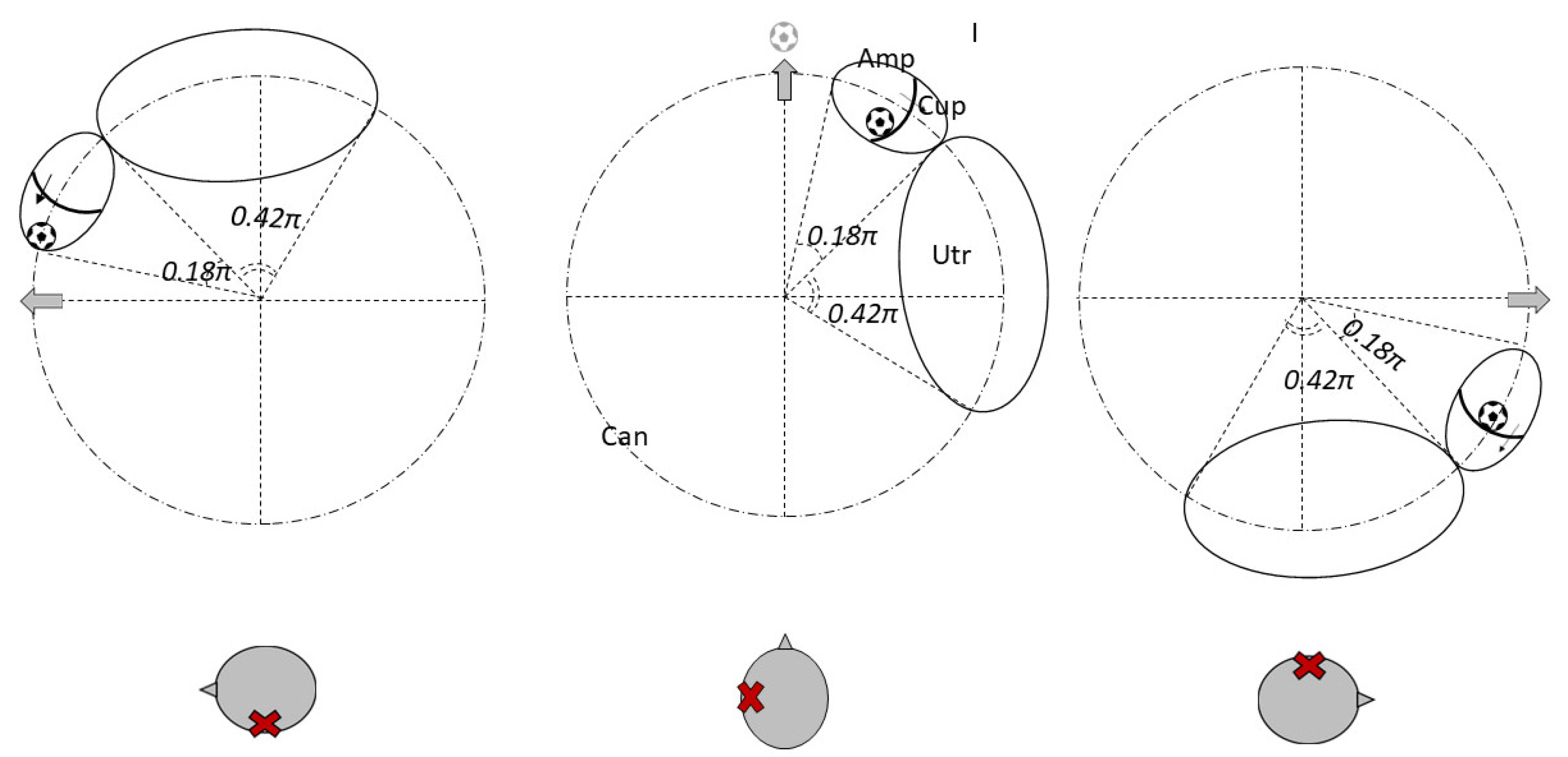

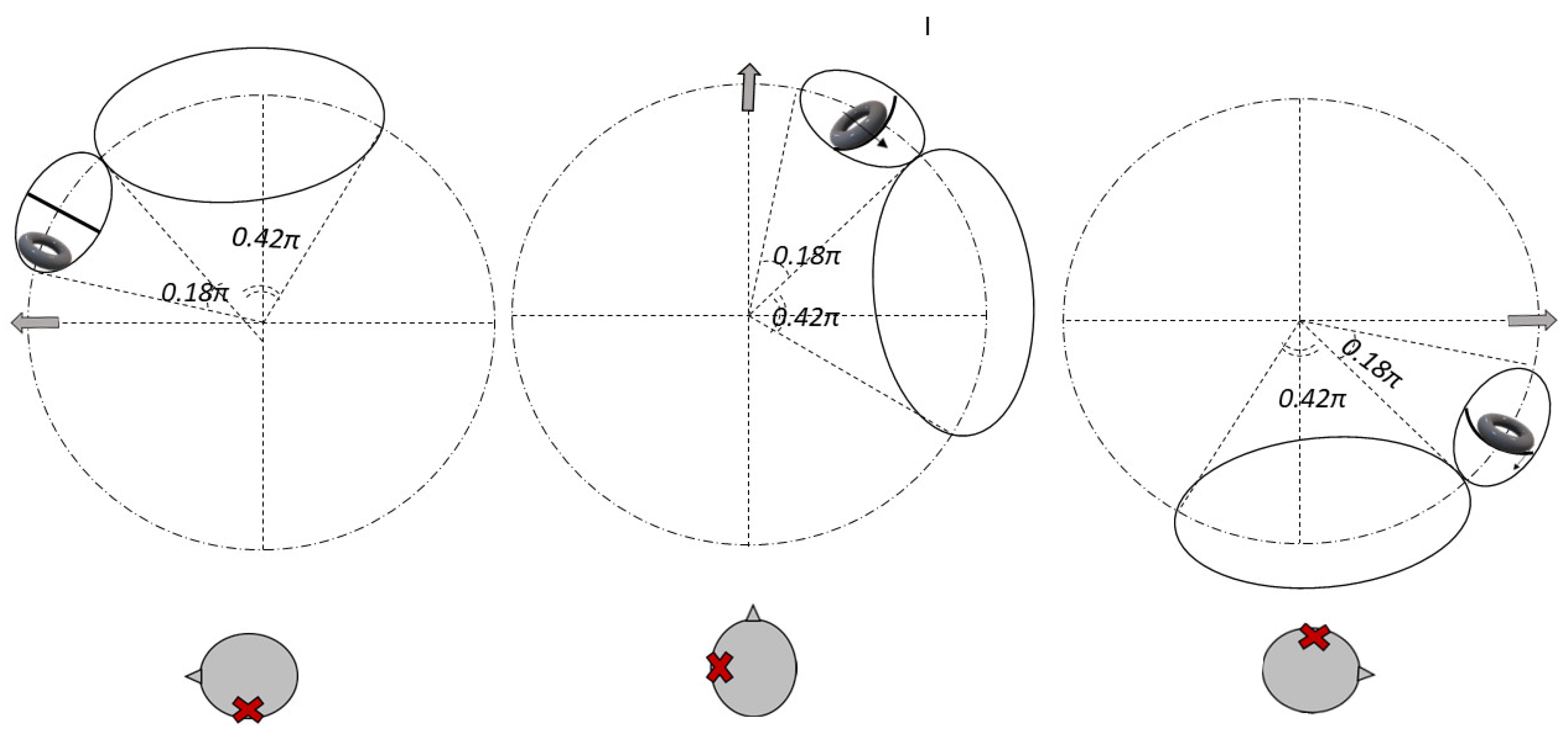

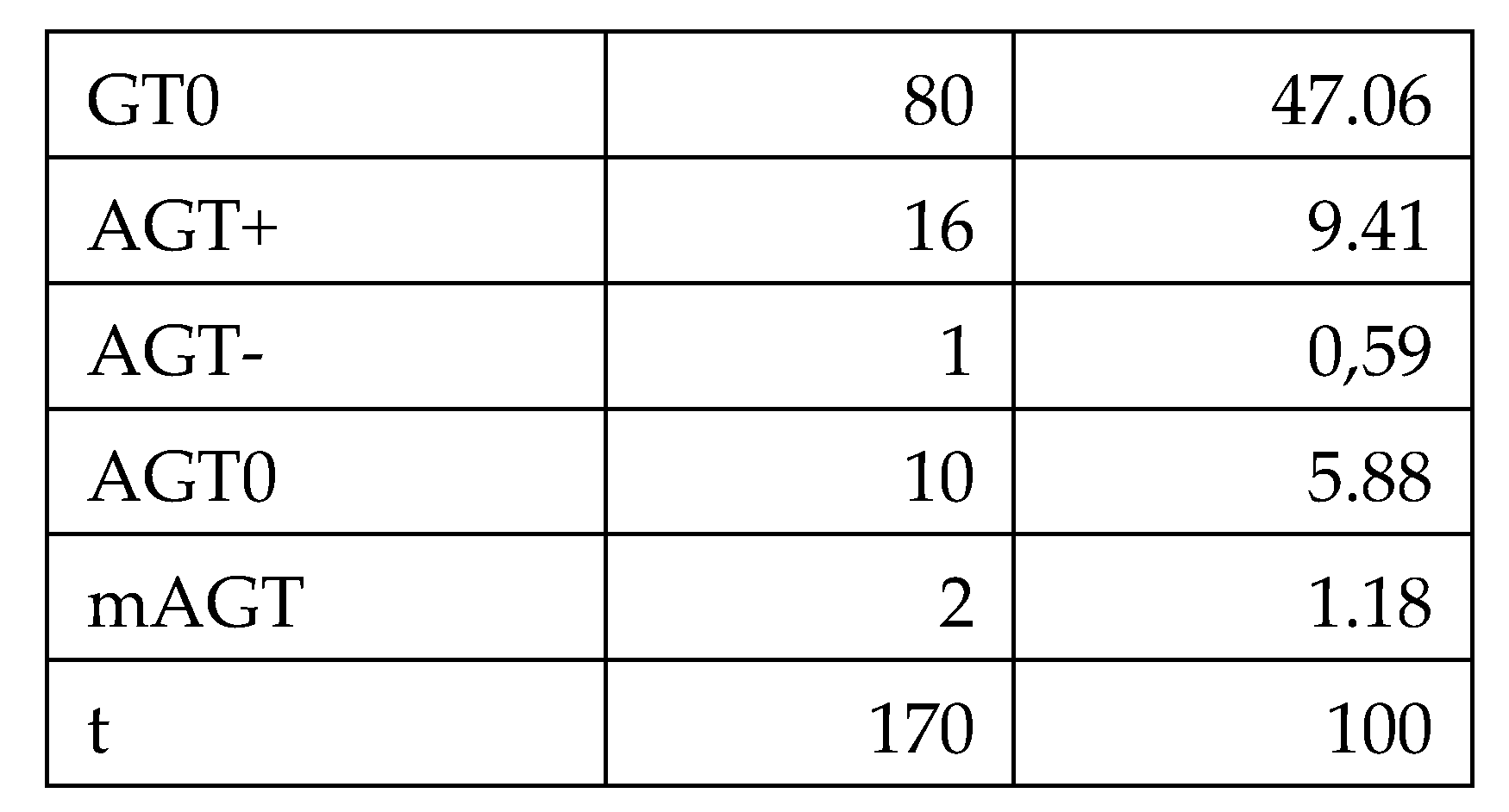

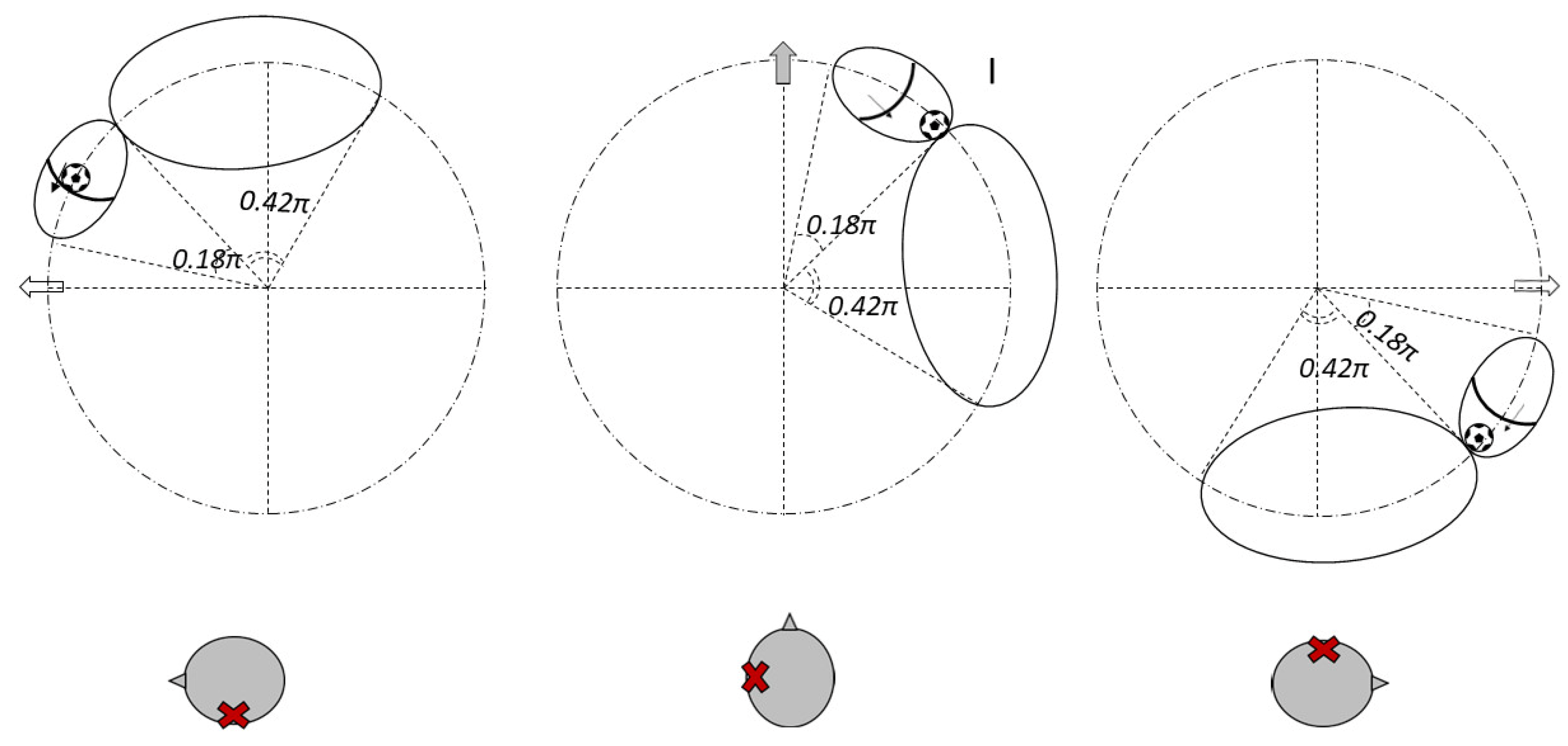

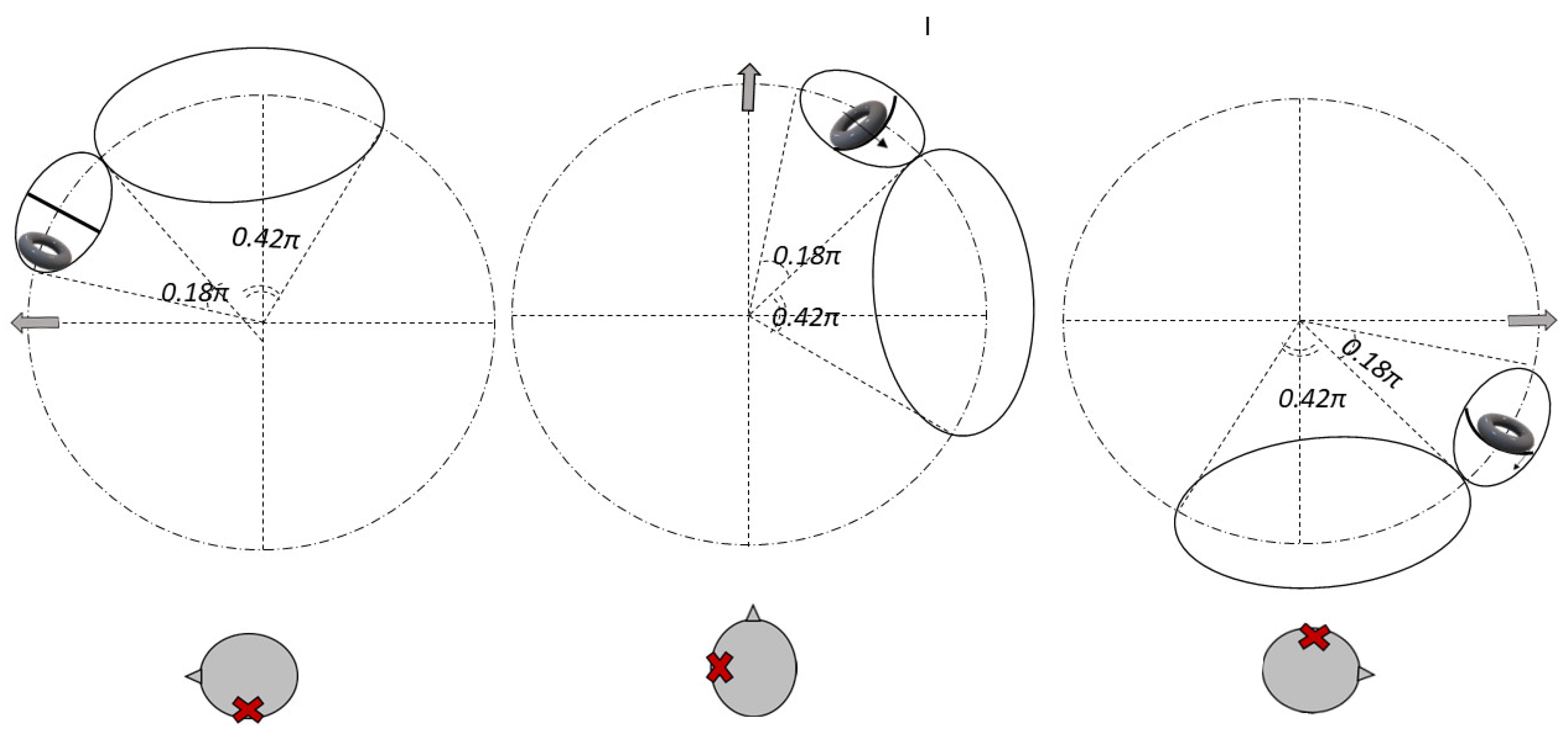

Debris in Quadrant I [

11]: Whether located on the utricular (Figure 2) or canal (Figure 3) side of the ampulla, the outcome is the same—a nystagmus directed toward the affected side upon clinostatism, with apogeotropic bipositional nystagmus. This pattern is also indistinguishable from cupula-adherent debris, regardless of side. The only clinical method to differentiate between a canal-side and utricle-side jam is to observe whether the liberatory maneuver is effective on the affected or opposite side [

12,

13].

Figure 2.

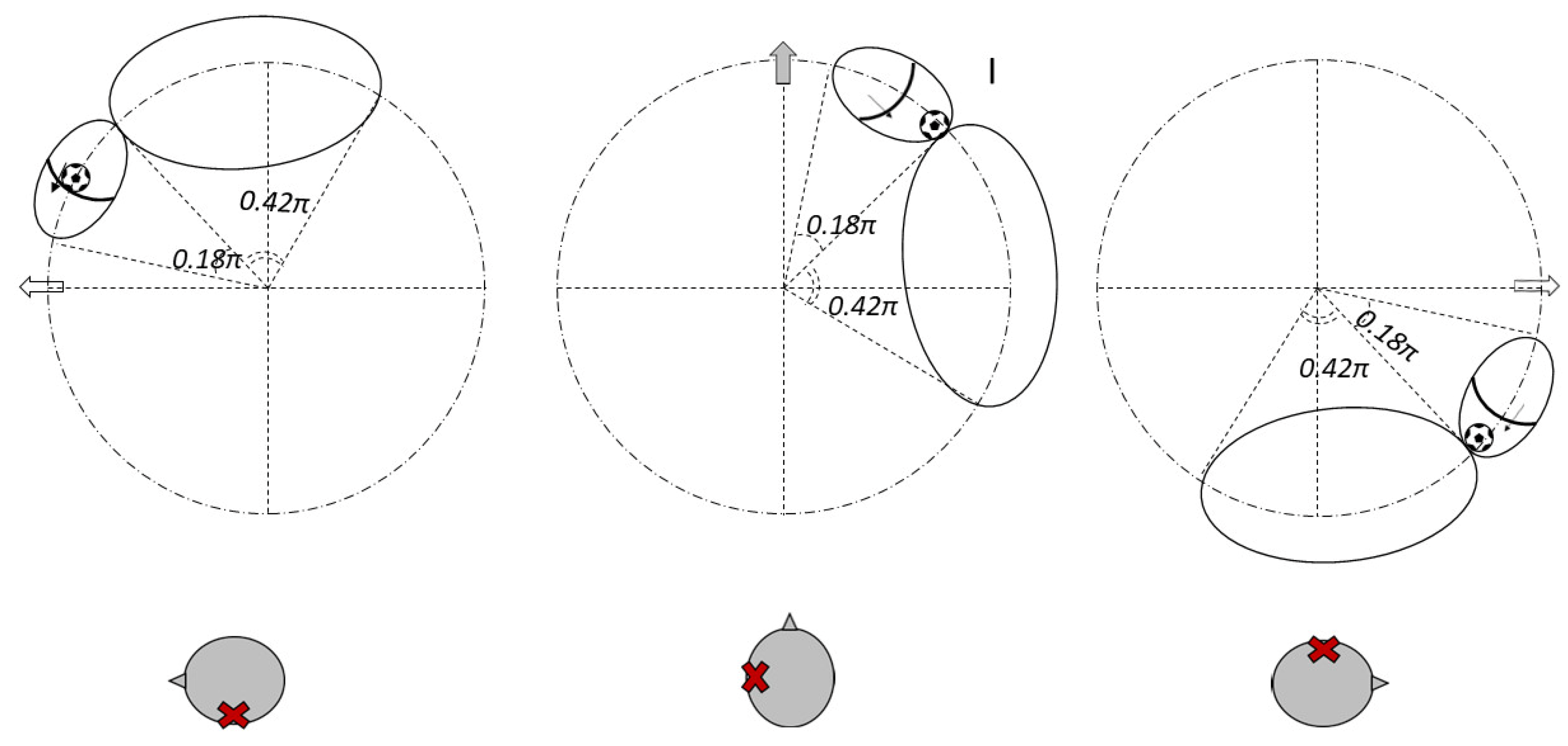

A “sieve jam,” where the block allows partial flow (Figure 4), would produce monopositional apogeotropic nystagmus on the affected side only. When the head is turned to the healthy side, the debris contacts and deflects the cupula; when turned to the affected side, no pressure gradient is created due to its position.

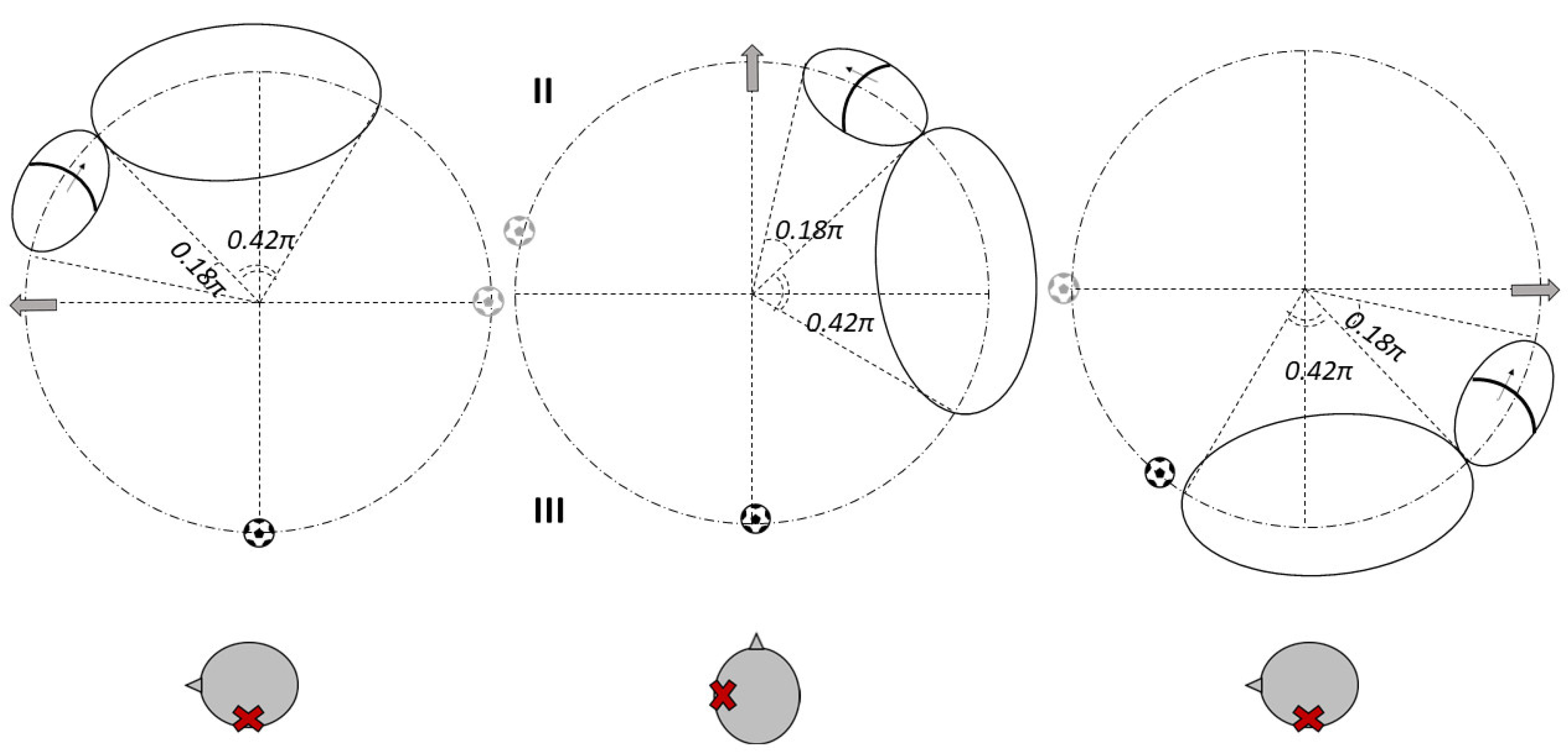

- 2.

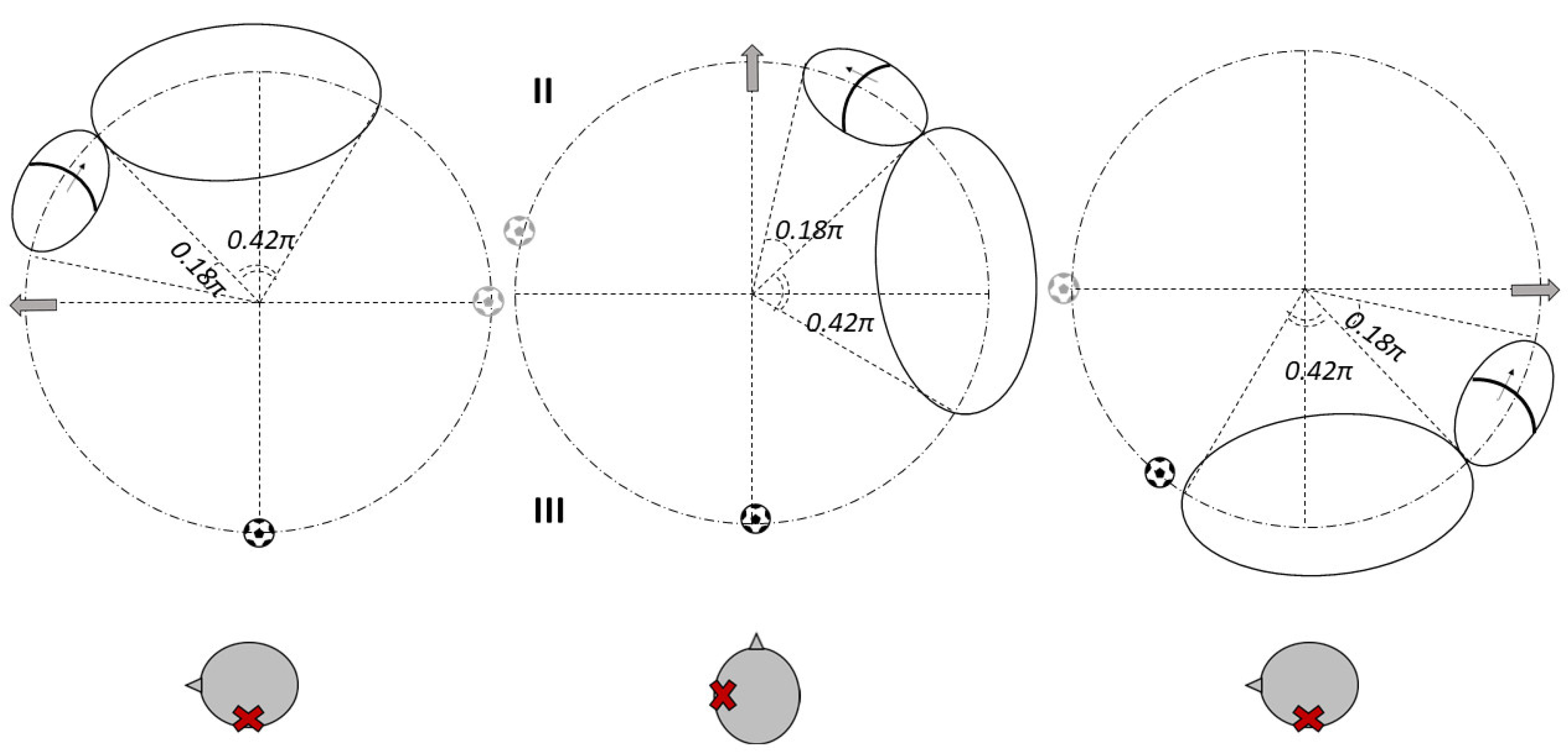

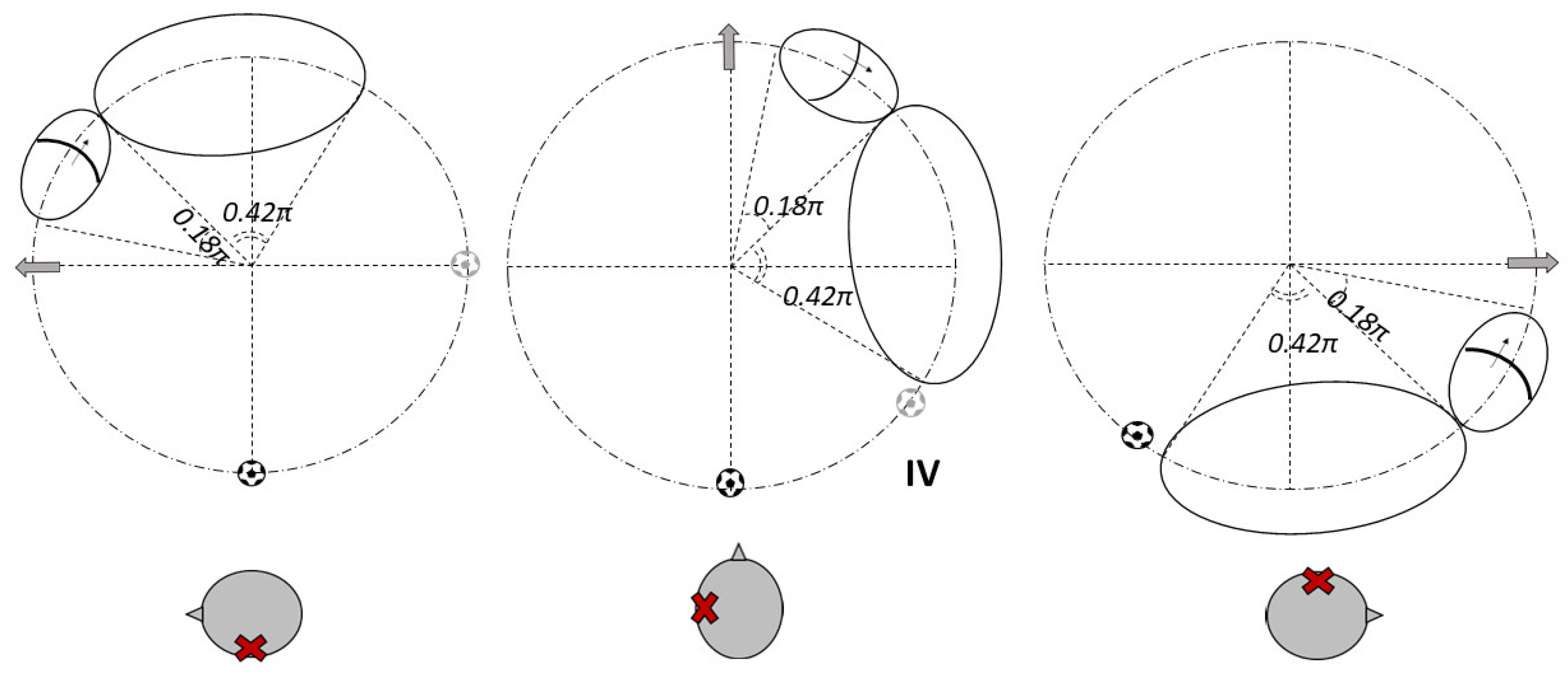

Debris in Quadrants II or III (Figure 5): These configurations correspond to classic geotropic forms, with supine nystagmus beating toward the healthy ear.

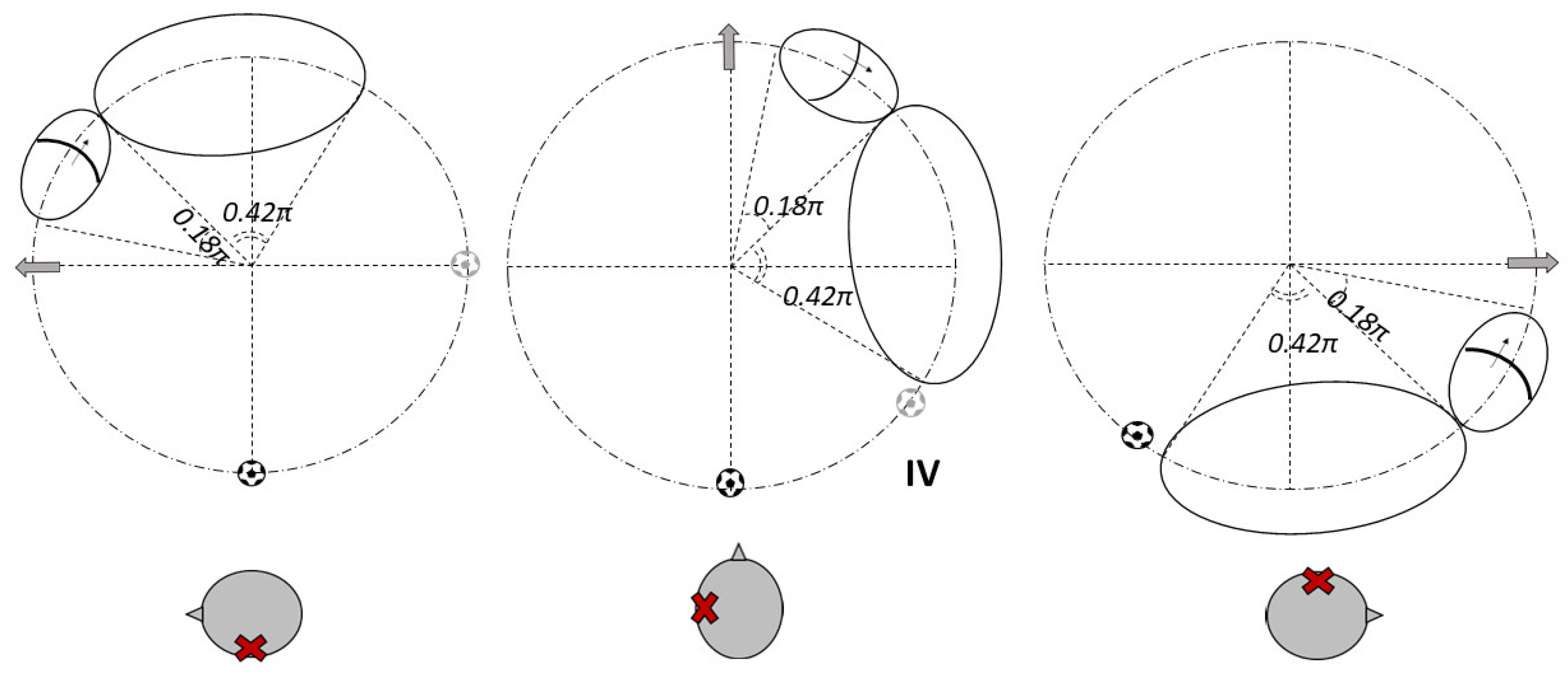

- 3.

Debris in Quadrant IV (Figure 6): In contrast, this scenario leads to supine nystagmus beating toward the affected ear, yet still results in a geotropic pattern during head turns.

Regarding nystagmus characteristics, particle swarms typically produce paroxysmal nystagmus, whereas conglomerated debris may cause more persistent responses, independent of their location.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

The clinical data reveal a noteworthy observation: over half of the cases lacked nystagmus when transitioning to the supine position. While its presence can help localize the lesion, its absence does not rule out canalolithiasis.

Possible explanations include:

Debris may initially be too dispersed to generate an effective endolymphatic current but later aggregate into a mass capable of inducing symptoms.

A non-mobile jam may not move during the supine transition but only during head rotations.

Excluding cases without lying-down nystagmus, debris was presumed to be located in:

The relative rarity of debris in Quadrant IV may be explained by centrifugal forces acting during natural horizontal head movements, which tend to move debris toward other canal regions.

In 2 of 29 apogeotropic cases (~7%), monopositional apogeotropic nystagmus suggested a sieve-type jam. These cases require careful differential diagnosis, and the most reliable indicator remains the response to liberatory maneuvers [

12].

One apogeotropic case featured “incongruent” supine nystagmus—likely an anecdotal outlier, potentially due to patient head misalignment or canal angle variability during testing.

Figure 7.

5. Conclusions

The mobile jam hypothesis provides a plausible explanation for findings throughout the horizontal semicircular canal. Our study does not exclude the presence of true cupulolithiasis, nor the possibility that both mechanisms coexist.

Key takeaways include:

a) To differentiate between utricular- and canal-side jams, the only reliable method is to determine on which side the liberatory maneuver is effective. For this reason, we recommend performing the maneuver on one side, verifying the result, and repeating it on the opposite side if necessary.

b) Supine nystagmus (clinostatism) is an important diagnostic clue but its absence does not preclude lateral canalolithiasis.

c) The mobile jam theory is consistent with the observed clinical data.

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hall SF, Ruby RR, McClure JA. The mechanics of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol. 1979 Apr;8(2):151-8. [PubMed]

- Epley, JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992 Sep;107(3):399-404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini P, Nuti D, Vannucchi P. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of the horizontal canal. ENT J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1989;51(3):161-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuknecht, HF. Cupulolithiasis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1969; 90(6): 765-78.

- Kalmanson O, Foster CA. Cupulolithiasis: A Critical Reappraisal. OTO Open. 2023 Mar 1;7(1):e 38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griech SF, Carroll MA. The use of mastoid vibration with canalith repositioning procedure to treat persistent benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: A case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018 Nov;34(11):894-899. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1952;61(4):987 1016. 10.1177/000348945206100403).

- Pagnini P, Nuti D, Vannucchi P. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of the horizontal canal. ENT J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1989;51(3):161-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Pagnini P. Treatment of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res. 1997 Jan-Feb;7(1):1-6. [PubMed]

- Gufoni M, Casani AP. The clinical significance of direction-fixed mono-positional apogeotropic horizontal nystagmus. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2022 Jun;42(3):287-292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büki B, Mandalà M, Nuti D. Typical and atypical benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: literature review and new theoretical considerations. J Vestib Res. 2014;24(5-6):415-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gufoni M, Mastrosimone L, Di Nasso F. Repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal vertigo of horizontal semicircular canal]. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1998 Dec;18(6):363-7. Italian. [PubMed]

- Casani AP, Dallan I, Berrettini S, Raffi G, Segnini G. Le manovre terapeutiche nella vertigine parossistica posizionale: possono indicarne una possibile genesi centrale? [Therapeutic maneuvers in the treatment of paroxysmal positional vertigo: can they indicate a central genesis?]. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2002 Apr;22(2):66-73. Italian. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).