1. Introduction

The emergence of software that combines artificial intelligence and large language models, with examples like ChatGPT and DeepSeek, presents both prospects and hurdles for educators in terms of assessing students’ academic performance (Dehouche, 2021; Hosseini et al., 2023; Williamson et al., 2023). This software can be a helpful assistant in many aspects, including preparing assignments in universities. Consequently, educators are tasked with guiding students toward the responsible and ethical utilization of these technologies to achieve prescribed learning outcomes. For instance, students should be encouraged to leverage these tools not as generators of answers, but as sources for inspiration, feedback, or reference materials. At the same time, there are substantial concerns about the efficacy of current plagiarism-detection software in identifying content generated by these applications. While specialized tools, such as Turnitin, can detect and highlight plagiarized sections in written work, students may circumvent these mechanisms by using techniques like the “back-translation” method (Michael & Lynnaire, 2015; Yankova, 2020). Furthermore, such software often provides probabilistic assessments indicating whether specific text segments are likely to be AI-generated, without definitive proof. This ambiguity can lead to disputes between students and teachers in cases of suspected academic dishonesty. Ultimately, the main role of teachers should not be detecting plagiarism but instead cultivating critical thinkers.

Considering the rapid increase of AI applications in the careers of graduates, universities should perceive them as valuable tools rather than software to be avoided. The new tools require a change in the way student assignments are designed and graded. One such change is to require students to articulate their work in their own words. This is achieved by requiring students to submit screen-capture videos, also known as screencasts, in which students must explain their work. As students create these videos, they are called student-created screencasts (SCSs). Optionally, teachers can require students to turn on the camera and record their explanation as the audio of the video. The requirement for students to demonstrate their knowledge is consistent with the principle of constructivism. However, students may not be willing to submit screencasts as assignments. This is because, when compared with traditional written assignments, students must acquire new skills and exert additional effort to create screencasts.

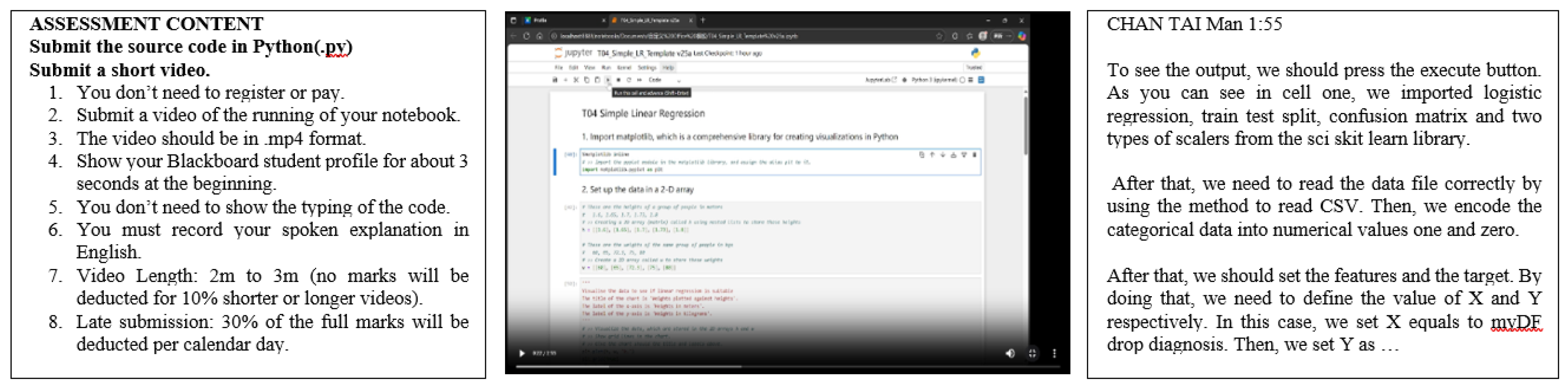

A typical SCS is shown in

Figure 1, together with the assignment instructions and an anonymized script under the fake name CHAN Tai Man. This assignment requires students to record their voice, but they do not have to show their face.

Educators cannot realize the potential benefits of SCSs if it is not feasible for students to create screencasts and accept them as a form of assignment. Therefore, this research study aims to understand students’ acceptance of SCSs as assignments in universities using a modified version of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). The results of this research will pave the way for future research to exploit the benefits of SCSs. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Firstly, will review the use of screencasts in education and the background and applications of the UTAUT. Then the Literature Review section will examine the gaps in screencasts in education and discuss the constructs in the UTAUT. The Methodology and Research Design section will present the hypotheses and describe the design of the survey questionnaire. The Results and Discussions section will discuss the results. Finally, the Conclusion section will summarize the findings, state the limitations, and suggest future research directions.

1.1. The Potential of Screencasts as a Pedagogical Tool

A SC is a screen-capture video that shows the contents on the screen and the users interactions with the computer. The user actions include mouse clicks, drags and keyboard entries. The user’s voice can also be part of the video. Thus, a SC created by a student is called a student-created screencast (SCSs). Screencasts are useful tools in education. Previous research show that teacher-created videos can increase student engagement and improve student performance than attending traditional lectures (Pereira, Echeazarra, Sanz-Santamaría, & Gutiérrez, 2014; Orús et al., 2016). Students react positively when teacher-created videos are used in lessons (Peterson, 2007; Kawaf, 2019). However, Morris and Chikwa (2013) found despite an “overwhelmingly positive” perception towards videos there was only a “modest” effect of videos on undergraduates’ knowledge acquisition. The principles of constructivism imply that students will benefit even more when they make their videos to explain certain concepts or demonstrate particular skills. (Shieh, 2012, p.206). Hence, we propose requiring students to create videos to explain their work to their teachers. Explaining to someone else is the best evidence that one has understood something. Albert Einstein summarized this with the statement: “If you cannot explain it simply, you don’t understand well enough” (Bindu & Manikandan 2020, p. 4894). This study investigates student perceptions of submitting assignments as videos, called screencasts, which they must explain their work.

It is reasonable to assume that students would not accept SCSs as assignments because it would involve different skills and efforts than the usual “search-edit-submit” method. However, they are likely to accept this new assignment format if they see the future value self-created screencasts for their future study and career. Hence, we propose studying students’ acceptance of SCSs by modifying a proven framework – the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT).

1.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

This research project proposes using a modified version of UTAUT to examine students’ acceptance of creating screencasts as assignments. The UTAUT framework was created by Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis (2003). It states that a person accepts and uses a technology based on that person’s attitude towards the technology. The attitude towards technology is, in turn, influenced by four factors known as constructs. The constructs of the original UTAUT are listed below.

“Performance Expectancy (PE): the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help them to attain gains in the job” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 447).

“Effort Expectancy (EE): the degree of ease associated with using the system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 450).

“Facilitating Conditions (FC): the degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 453).

“Social Influence (SI): the degree to which an individual perceives whether others believe they should use the new system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 451).

Modifications to constructs were necessary when applied in different fields of study when the UTAUT was used in various contexts (Negahban & Chung, 2014; Bagozzi, 2007). In this project, the constructs of FC and SI are not applicable. For FC, the teacher provided free online tools for creating the screencasts. The condition for creating screencast is just a computer with an Internet browser. Therefore, there is no extra cost or software installation required. For SI, the students are required to submit screencasts as assignments. Hence, their use of screencasts is not affected by social influence. However, students may have a positive attitude towards SCSs because they can use them to practice for online interviews, or make pre-recorded demonstrations to their clients or colleagues. Therefore, we propose the new construct of Future Utility (FU) as below:

Future Utility (FU): the degree to which an individual believes that the technology can be used in a future situation to achieve the individual’s purpose.

This study surveyed students on their perceptions of Student-Created Screencasts (SCS) using the constructs of PE, EE and FU to form the modified UTAUT research model. Then, the data was analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine the influencing factors and the moderators.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gaps in Existent Research on Student-Created Screencasts

Finding students who are having difficulty in a subject is crucial. However, the typical educational design in many university courses consists of only a few tasks and one critically important assessment at the end. Students who perform well on the assignments but fail on the final examination are frequently observed. As Bernacki, Chavez & Uesbeck (2020) pointed out that most of the “early warning” research is focused on “alternative, more data-rich contexts including massive open online courses (MOOCs)”. At the early stage of the course, SCS may be a more reliable measure of students’ performance than regular assignments. Which pupils need assistance would be determined by it. Lynch (2019) refers to intervention in education as a set of steps a teacher takes to help students improve in their area of need. According to Wong et al. (2017) and Korkmaz (2021), since that the intervention can significantly enhance the reading and writing skills of the students, it is important to identify those who are having difficulty learning English as a second language.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no using SCSs as an assessment. We examined research papers on screencasts that involved university education to get an overall view of the current state of research in this area, and to identify any gaps in literature. In the research papers about screencasts in higher education, there are many papers that do not explicitly investigate student-created screencasts, or no insufficient details are provided for a clear classification. We found several research articles that focused on using screencasts in higher education. These articles are listed in

Table 1. An analysis of these research articles revealed a significant bias toward teacher-created screencast research. This represents a substantial research gap that warrants immediate attention from the educational technology research community. Among the articles that focused on instructor-produced content, we classified them into 4 categories as shown in

Table 1. It shows that the teacher-provided screencasts are used in five main areas – optional supplementary learning materials, feedback delivery, enhancements to lectures, and specialized subject support such as statistics.

The identified research gap is significant because current research only examines one side of the educational equation—content delivery—while ignoring content creation by students. This pedagogical imbalance may imply miss missed learning opportunities. The principle of constructivism indicates that creating content enhances learning more than consuming it, yet this principle remains unexplored in research related to screencasts. This research represents an innovative first step to explicitly study student-created screencasts.

2.2. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

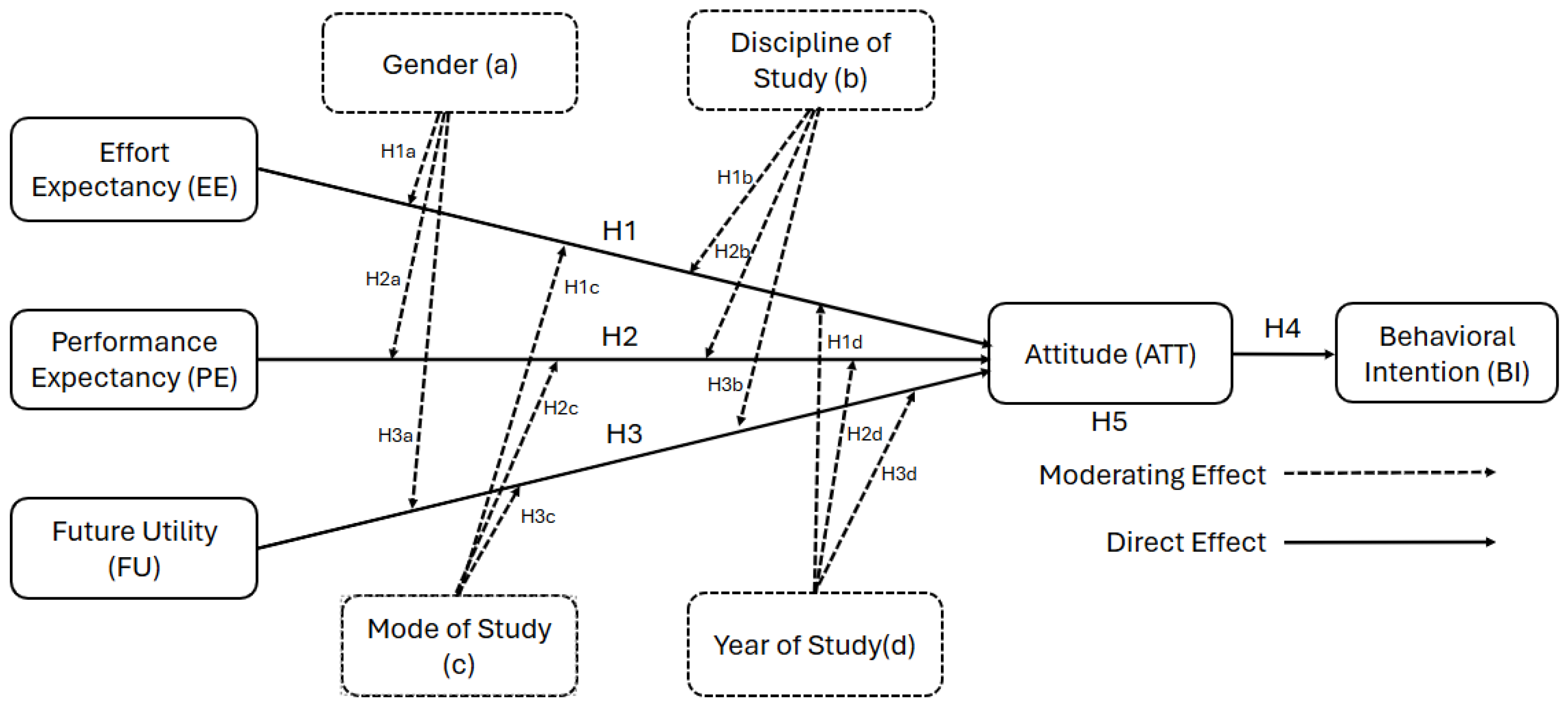

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) framework was created by Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis (2003). It states that a person accepts and uses a technology based on that person’s attitude towards the technology. The attitude towards technology is, in turn, influenced by four factors known as constructs. As discussed in the Introduction section, we propose removing the constructs FC and SI, and add FU. The constructs in our proposed modified UTAUT are shown in

Figure 2 and are discussed below.

2.2.1. Effort Expectancy (EE)

EE refers to the degree of ease associated with using the technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). According to Nguyen and Nguyen (2024), individuals’ behavioral intention and actual use of a particular technology related to their belief on free of effort while using it. For students’ perception on SCS, the ease of creating SCS must be examined. Additionally, individuals’ EE proved positively influence their attitude and intention towards acceptance of a technology (Moon & Hwang, 2016).

2.2.2. Performance Expectancy (PE)

PE refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help them to attain gains in the job (Venkatesh, 2003). According to Sari et al. (2024), performance expectancy positively influences the intention to adopt technologies, indicating that higher expectations of performance lead to more favorable attitude towards technology adoption in individuals’ educational context. In this study, the performance expectancy refers to students’ belief on creating SCSs help improve their learning activities.

2.2.3. Future Utility (FU)

FU refers the degree to which an individual believes that the technology can be used in a future situation to achieve the individual’s purpose. FU share similar concept with perceived usefulness in TAM (Davis, 1989), but specifically aiming at perceiving its usefulness in the future. In this study, we examine students’ view on using SCSs in future, which also shows their attitude towards SCS.

2.2.4. Attitude (ATT)

ATT refers to the individuals’ favor or not favor to a particular technology. According to Or (2023), ATT is influenced by performance expectancy, effort expectancy in the context of information technology adoption. According to Ernst et al. (2014), individuals’ attitude toward usage of a technology is influence by perceived usefulness, which was considered similar to future utility.

2.2.5. Behavioral intention (BI)

BI is the most important variable in UTAUT. In this study, it represents students’ intention to use SCS. According to Venkatesh et al. (2003), individuals’ BI will have a significant positive influence on their usage towards the discussed technology. We hypothesize that BI was jointly determined by latent variables including effort expectancy, performance expectancy, future utility and attitude. Moreover, Buabeng-Andoh and Baah (2020) suggested that BI is influenced by attitude. Therefore, we propose the following research model and hypotheses.

3. Research model and Hypotheses

As noted by Negahban & Chung (2014) and Bagozzi (2007), when using UTAUT in a specific research area, the researcher should make the necessary changes to the constructs to suit the research project at hand. In this project, the constructs of FC and SI are not applicable, as students are required to use videos, and the infrastructure needed to create screencasts is simply a computer with an Internet browser. Therefore, FC and SI are not included in this study. Since this research is on students in higher education, it is possible that these students may have a positive attitude towards SCSs because they can use them to practice for online interviews and make pre-recorded demonstrations to their clients or colleagues. Therefore, we propose the new construct of Future Utility (FU). In summary, this study used a modified UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003), and it includes the constructs of effort expectancy (EE), performance expectancy (PE), future utility (FU), attitude (ATT) and behavioral intention (BI). The research model and our hypotheses are shown in

Figure 2.

3.1. Research Hypotheses

Under the modified UTAUT framework, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Student attitude towards SCSs is affected by the effort expectancy.

H2: Student attitude towards SCSs is affected by the performance expectancy in their study

H3: Student attitude towards SCSs is affected by the perceived future utility.

H4: Student behavioral intention towards SCSs is affected by their attitude.

H5: Students have a positive attitude towards SCSs.

3.2. Moderators

The effects of above constructs may be moderated by factors such as gender, year of study at the university, discipline of study and mode of study. The years of study are represented by the numbers which correspond to the stage in a 4-year university curriculum. The students in this study belong to different programs of study such as language, engineering and information technology. In our model, the discipline of study is classified as science and non-science. The mode of study is either full-time or part-time. Therefore, we have the following hypotheses.

H1a, H2a, H3a: Gender moderates the effects of EE, PE and FU.

H1b, H2b, H3b: Disciplines of study moderate the effects of EE, PE and FU.

H1c, H2c, H3c: Mode of study moderate the effects of EE, PE and FU.

H1d, H2d, H3d: Year of study moderate the effects of EE, PE and FU.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Method and Participants

This research adopted a quantitative approach. The students in this study were studying at different stages in a higher education institution. These students had to complete an individual assignment in which they must submit a screencast to explain their work. All the screencasts are less than 3-minutes in length and the students must record their voice in English to explain their work. However, the students did not have to show their face. After the subjects have finished and the grades are released, the students completed an online survey. This timing ensured the students that their response in the survey would not affect their grades.

Table 2 shows the subject code, subject names, and the number of respondents. In the survey, there was a consent statement, and the students can opt out of the survey. Eventually, there were 203 valid responses. The demographics of the students are shown in

Table 3.

4.2. Research Instrument

The survey was separated into two parts. In part one of the survey, the questions collected the students’ demographic information, including their gender, age and their previous qualification before joining the university. The results of this part are shown in

Table 3. In part two of the survey, the questions are adopted and adapted from Khechine et al. (2014) and Wu & Chen (2017), plus the two questions on FU. The questions and their source are shown in

Table 4. These questions asked students to rate their answers using a 5-point Likert Scale. The answers were coded as 5 for “Strongly Agree”, 4 for “Agree”, 3 for “Neutral”, 2 for “Disagree”, 1 for “Strongly Disagree”.

5. Results and Discussions

In this study, SmartPLS v4.1.1.2 was used to implement the PLS-SEM approach. All data were retrieved through PLS-SEM algorithm and 5000 sampling sized Bootstrapping in 0.05 level. There are two components in PLS. The first component is the measurement model which specifies the correlation between constructs by evaluating their validity and reliability. The second component is the structural model which specifics the interaction and influence between constructs. The results of these two components are presented and discussed below.

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

Table 5 shows the validity and reliability of the collected data. It is important to carry a reliability testing when assessing data consistency, stability, dependability of measurement data and outcomes to determine the reliability of the data. There are standard of acceptable range regarding different latent variables suggested by Hair et al. (2020). For a reliable latent variable, the Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) should not be below 0.7 to be considered as dependable. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha and CR were in range between 0.866 and 0.977, which surpassed the 0.7 threshold. Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed 0.5 to indicate that the latent variables have ideal convergent validity. In this study, the AVE were in range between 0.820 and 0.933, which surpass the 0.5 threshold.

To examine the discriminant validity of the constructs, Fornell-Larcker criterion was performed as shown in

Table 6. According to Ab Hamid et al. (2017), the Fornell-Larcker value of a construct correlated itself (square root of AVE) should be greater that its Fornell-Larcker value correlated to other constructs as shown above. As a result, all constructs were confirmed to have acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 6.

Fornell-Larcker criterion

Table 6.

Fornell-Larcker criterion

| |

EE |

PE |

FU |

ATT |

BI |

| EE |

0.906 |

|

|

|

|

| PE |

0.634 |

0.921 |

|

|

|

| FU |

0.582 |

0.760 |

0.939 |

|

|

| ATT |

0.651 |

0.805 |

0.828 |

0.957 |

|

| BI |

0.569 |

0.718 |

0.739 |

0.806 |

0.966 |

Table 7.

VIF values for the inner model (VIF < 5 represent generally accepted of the presence of collinearity)

Table 7.

VIF values for the inner model (VIF < 5 represent generally accepted of the presence of collinearity)

| Path |

VIF |

| EE -> ATT |

1.740 |

| PE -> ATT |

2.729 |

| FU -> ATT |

2.467 |

| ATT -> BI |

1.000 |

To diagnose the presence of collinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was performed. Hair et al. (2020) suggest that having VIF values of 5 or above indicate critical collinearity issues. In this study, all paths are within the acceptable range of 5. The measurement model assessment shows the reliability and validity of the constructs, allowing further analysis.

In summary, the above results show that the measure model is valid. The next section examines the results in the structural model assessment, in which the hypotheses were tested using the results from the survey.

5.2. Structural Model Assessment

Table 8 shows the structural model with the results from the survey. The path coefficient, t value, p value, R2, and f 2 are some of the components used to test the hypotheses. The strength of the association between latent variables can be determined by looking at the path coefficient value. Huber et al. (2007) state that to account for a particular influence within the model, the path coefficients claimed significant when exceeding 0.100 in the 0.05 level. The size difference of relation to the variation in the sample data is measured using t values. According to Winship and Zhuo (2020), t values of the path should be greater than 0.196 to be deemed significant, as the traditional critical value of the t statistic is 1.96 for two-tailed tests at a significant level of 0.05. Therefore, the hypotheses H1, H2, H3 are H4 accepted.

5.3. Moderating Effect

Table 9 shows their moderating variables and their effects in the structural model. The moderating effects with p values exceeding 0.05 are considered not statistically significant. Therefore, all the moderators were not significant except for H1b, which states that the students’ years of study moderates the influence of EE on ATT.

5.4. Students’ Attitudes (ATT) Towards SCS

Students’ general attitude (ATT) towards SCS is crucial. As the survey was designed on 5-point Likert scale, in which “1” means “strongly disagree”, “3” means “neutral”, and “5” means “strongly agree”, it is crucial to if there is a significant difference between “3” and the average responses. To determine whether the difference is significant, a one-sample t-test was performed.

First, there are three questions regarding students’ attitudes towards SCS. A student’s ATT was calculated as the student’s average response to those three questions. For example, if a student answered questions “I believe that creating Screencasts is a good idea in this subject.”, “I believe that creating Screencasts is good advice in this subject.” and “I have good impression about Screencasts.” are 4, 4 and 5 points respectively, then the student’s ATT will be 4.333. In this study, average ATT from all samples is 3.714. To determine if the students indeed have a positive attitude towards SCS, we need to determine whether this average is statistically significantly higher than 3, we adopted the critical t-value method (Ross & Wilson, 2017).

According to Ross and Wilson (2017), the formula for calculating the t-value in a one-sample t-test is shown below.

Where is the sample average (which is 3.714). μis the hypothesized average, (which is 3), s is the samples standard deviation (which is 0.922), n is the number of samples (which is 203). According to the formula above, the t-value was 11.034. The p-value was calculated using the Excel formula “T.DIST.ST(ABS(t-value), Degrees of freedom)”, and the critical t-value (1.972) was computed using Excel formula “=T.INV.2T(0.05, Degrees of freedom)”, where degrees of freedom were 202 (number of samples - 1). As the p-value (0.000) is smaller than 0.05, and the t-value (11.034) of the sample is greater than the critical t-value. Thus, the hypothesis H5 was accepted.

5.5. Discussions

Insights from the modified UTAUT

As the hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 are accepted, the UTAUT model confirms that students’ attitudes (ATT) toward SCSs are significantly influenced by EE, PE, and FU. According to the results in

Table 8, Future Utility (FU) exhibited the strongest influence on ATT. This result implies that students are more likely to have a favorable perception of SCSs if they recognize the relevance of screencasts for future use. This finding aligns with the principle of constructivism, which emphasizes the importance of practical and transferable skills in learning. Similarly, Performance Expectancy (PE) also demonstrated a significant strong positive effect on ATT. Thus, this result indicates that students perceive SCSs as a tool that can enhance the quality of their learning activities. This confirms the potential of student-generated content, in terms of screencasts, to improve learning outcomes. However, the modest contribution of EE to ATT suggests that while ease of use is important, students’ acceptance of SCSs is primarily driven by perceived benefits rather than the simplicity of the process. Finally, Behavioral Intention (BI) toward using SCSs was significantly influenced by ATT. This strong relationship between ATT and BI means it is important to induce favorable perceptions among students by providing helpful guidelines, student-friendly tools, and constructive feedback on screencast assignments.

Implications of the moderating effects

The moderation analysis revealed some interesting insights. Notably, gender, discipline of study, and mode of study did not significantly moderate the relationships between Effort Expectancy (EE), Performance Expectancy (PE), or Future Utility (FU) and Attitude (ATT). This suggests that the acceptance of Student-Created Screencasts (SCSs) is relatively uniform across diverse student demographics, making this approach broadly applicable across different groups of learners. However, a notable exception was observed with the year of study, which moderated the relationship between EE and ATT. Specifically, students in later years of their academic journey exhibited less favorable perceptions of the effort required to create screencasts. This could be attributed to their greater exposure to traditional assessment methods and the more complex and demanding nature of their upper-level coursework. In contrast, students in earlier years may view the additional technical and creative skill requirements of SCSs as an exciting and manageable challenge that aligns with their early-stage learning experiences. This finding highlights the need for tailored approaches when introducing SCSs, particularly for students in advanced years of study.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study highlight the potential of SCSs as an innovative and effective assessment tool in higher education. To encourage students’ acceptance of SCSs, educators should focus on making students aware of the long-term benefits of screencast creation, such as its applicability in professional settings like online interviews and client presentations. Communicating these future-oriented advantages can enhance students’ perceptions of the value of SCSs, particularly through the lens of skill development and career preparation.

Another critical implication is the need to address students’ concerns about the perceived effort involved in creating screencasts. Providing clear instructions, accessible tools, and technical support can help students overcome initial hurdles and develop confidence in their ability to produce high-quality screencasts. Additionally, embedding screencast training into the curriculum, particularly in the early years, can help normalize this form of assessment and reduce the resistance often associated with unfamiliar tasks. For students in later years, educators might consider integrating SCSs into projects that align with their existing expertise or provide support to help students to transition from traditional assessments to this more technology-driven and innovative form of assessment.

Finally, there are implications for teachers too. Firstly, they need to develop new assessment rubrics that are suitable for SCSs. Secondly, they may perceive that they need to spend extra efforts to view and mark the SCSs. Finally, the viewing of SCSs may review other aspects of students that teachers were not aware of before.

6. Conclusions

This research examined university students’ acceptance of student-created Screencasts as assignments. Given the potential benefits of student-created screencasts according to the principle of constructivism, this study contributes to narrowing the imbalanced amount of research on teacher-created screencasts and student-created screencasts. imbalanced research on using screencasts as pedagogical tools. Using the modified UTAUT, we identified key factors influencing students’ attitudes and behavioral intentions toward SCSs. Among these, Future Utility (FU) emerged as the most significant predictor of students’ attitudes, indicating that students are more likely to embrace SCSs when they see their relevance and applicability in future professional or academic contexts. Performance Expectancy (PE) and Effort Expectancy (EE) also played important roles, underscoring the need to balance the perceived benefits of SCSs with the effort required to create them. In conclusion, this study underscores the potential of Student-Created Screencasts as a transformative educational tool. By addressing the identified limitations and pursuing new research directions, educators and researchers can further unlock the pedagogical value of SCSs, paving the way for their broader adoption and integration into higher education.

6.1. Limitations

We acknowledge this study has several limitations. First, the research was conducted within a single institution, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future research should replicate this study across multiple institutions and cultural contexts to confirm the results and explore any variations. Second, the reliance on self-reported survey data introduces the possibility of response bias. Incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide richer insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of SCSs. Third, while this study focused on students’ acceptance of SCSs, it did not directly measure the impact of SCSs on learning outcomes. Future research could examine whether SCSs lead to measurable improvements in academic performance, engagement, or skill development.

6.2. Future Research Directions

Looking ahead, there are many opportunities to build on the findings of this study. Researchers could explore the use of SCSs in different disciplines to assess their adaptability and effectiveness across diverse subject areas. Additionally, the role of instructor support, feedback, and training in influencing students’ acceptance and performance with SCSs warrants further investigation. Longitudinal studies could also assess the long-term impact of using SCSs on students’ professional readiness and employability. Finally, future research could examine how SCSs might foster collaborative learning by incorporating peer feedback and group-based screencast assignments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Adam Wong; methodology, Adam Wong.; software, Lai Lam Chan; validation, Adam Wong; formal analysis, Adam Wong.; investigation, Adam Wong, Ken Tsang and Shuyang Lin.; resources, Adam Wong, Ken Tsang and Shuyang Lin; data curation, Adam Wong, Ken Tsang and Shuyang Lin; writing—original draft preparation, Adam Wong; writing—review and editing, Adam Wong and Lai Lam Chan; visualization, Adam Wong and Lai Lam Chan; supervision, Adam Wong; project administration, Adam Wong.; funding acquisition, Adam Wong. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. (Project Ref: UGC/FDS24/H24/24)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCS |

Student-Created Screencast |

| UTAUT |

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| EE |

Effort Expectancy |

| PE |

Performance Expectancy |

| FU |

Future Utility |

| ATT |

Attitude |

| BI |

Behavioral Intention |

References

- Ab Hamid, M. R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M. M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. In Journal of physics: Conference series; IOP Publishing, September 2017; Vol. 890, No. 1, p. 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The Legacy of the Technology Acceptance Model and a Proposal for a Paradigm Shift. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2007, 8(4), 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M. L.; Chavez, M. M.; Uesbeck, P. M. Predicting achievement and providing support before STEM majors begin to fail. Computers & Education 2020, 158, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, M. R.; Manikandan, R. Can Humans Take Medicines To Become Immortal? A Review Of Amish Tripathi’s Shiva Trilogy. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine 2020, 7(3), 4894–4897. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. In Handbook I: Cognitive domain; New York; David McKay Company, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Bonwell, C.; Eison, J. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom AEHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1; Washington, D.C.; Jossey-Bass, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chaka, C. Detecting AI content in responses generated by ChatGPT, YouChat, and Chatsonic: The case of five AI content detection tools. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching 2023, 6(2). [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouche, N. Plagiarism in the age of massive Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT-3). Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics 2021, 21, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din Eak, P. N.; Annamalai, N. Enhancing online learning: A systematic literature review exploring the impact of screencast feedback on student learning outcomes. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal 2024, 19(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P. K.; McDonald, C.; Loch, B. StatsCasts: Screencasts for complementing lectures in statistics courses. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology 2015, 46(4), 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C. P. H.; Wedel, K.; Rothlauf, F. Students’ acceptance of e-learning technologies: Combining the technology acceptance model with the didactic circle, 2014.

- Ghilay, Y.; Ghilay, R. Computer courses in higher-education: Improving learning by screencast technology. i-manager’s Journal on Educational Technology 2015, 11(4), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr.; Howard, M. C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Rasmussen, L. M.; Resnik, D. B. Using AI to write scholarly publications; Accountability in Research, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaf, F. Capturing digital experience: The method of video videography. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2019, 36(2), 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechine, H.; Lakhal, S.; Pascot, D.; Bytha, A. UTAUT model for blended learning: The role of gender and age in the intention to use webinars. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects 2014, 10(1), 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S.; Öz, H. Using Kahoot to improve reading comprehension of English as a foreign language learner. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET) 2021, 8(2), 1138–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Matthew. Types of Classroom Interventions. 15 October 2019. Available online: https://www.theedadvocate.org/types-of-classroom-interventions/.

- Moon, Y. J.; Hwang, Y. H. A study of effects of UTAUT-based factors on acceptance of smart health care services. In Advanced Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering: Future Information Technology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.; Chikwa, G. Videos: How effective are they and how do students engage with them? Active Learning in Higher Education 2014, 15(1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullamphy, D. F.; Higgins, P. J.; Belward, S. R.; Ward, L. M. To screencast or not to screencast. The ANZIAM Journal 2010, 51, C446–C460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahban, A.; Chung, C.-H. Discovering determinants of users perception of mobile device functionality fit. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 35, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, V. A. An application of model unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A use case for a system of personalized learning based on learning styles. International Journal of Information and Education Technology 2024, 14(11), 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, C. The Role of Attitude in the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modelling Study. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science 2023, 7(4), 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orús, C.; Barlés, M. J.; Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.; Fraj, E.; Gurrea, R. The effects of learner-generated videos for YouTube on learning outcomes and satisfaction. Computers & Education 2016, 95, 254–269. [Google Scholar]

- Penn, M.; Brown, M. Is screencast feedback better than text feedback for student learning in higher education? A systematic review. Ubiquitous Learning: an international journal 2022, 15(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Echeazarra, L.; Sanz-Santamaría, S.; Gutiérrez, J. Student-generated online videos to develop cross-curricular and curricular competencies in Nursing Studies. Computers in Human Behavior 2014, 31, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E. Incorporating Videos in Online Teaching. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 2007, 8(3), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder Grover, T.; Green, K. R.; Millunchick, J. M. The efficacy of screencasts to address the diverse academic needs of students in a large lecture course. Advances in Engineering Education 2011, 2(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.; Willson, V.L. One-Sample T-Test. In Basic and Advanced Statistical Tests. SensePublishers; Rotterdam, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N. P. W. P.; Duong, M. P. T.; Li, D.; Nguyen, M. H.; Vuong, Q. H. Rethinking the effects of performance expectancy and effort expectancy on new technology adoption: Evidence from Moroccan nursing students. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 2024, 19(3), e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, H.; MacLeod, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H. H. College students’ cognitive learning outcomes in technology-enabled active learning environments: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2020, 58(4), 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, R. S. The impact of Technology-Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) implementation on student learning and teachers’ teaching in a high school context. Computers & Education 2012, 59(2), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

The Government of HKSAR, “2016 Policy Address”. Available online: https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2021/eng/policy.html (accessed on 11 Feb 2022).

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M. G.; Davis, G. B.; Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view; MIS quarterly, 2003; pp. 425–478. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Macgilchrist, F.; Potter, J. Re-examining AI, automation and datafication in education. Learning, Media and Technology 2023, 48(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Delante, N. L.; Wang, P. Using PELA to Predict International Business Students’ English Writing Performance with Contextualised English Writing Workshops as Intervention Program. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 2017, 14(1). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Computers in Human Behavior 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).