1. Introduction

After more than ten years of theoretical exploration and technical practice, remarkable achievements have been made in the exploration and development of shale gas in the Wufeng Longmaxi Formation of the Sichuan Basin, forming a shale gas geological theory with Chinese geological characteristics and establishing targeted exploration and development technologies [1-2,35-36]. As shale gas exploration and development enters a stage of rapid scale production, the exploration and development technology for shallower shale gas (with burial depths up to 3500 m) continues to mature, and the deeper strata (with burial depths ranging from 3500 m to 4500 m) have emerged as the next key frontier for the next step of shale gas exploration [3-4]. However, compared to shallower shale gas wells, deep shale gas faces persistent challenges, such as casing deformation, which significantly impacts the development of gas fields [5-8]. Therefore, accelerating the analysis ofgeological-engineering risk conditions in deep shale and optimizing the evaluation technology of geological-engineering sweet spots in deep shale gas reservoirs are crucial for advancing the development of deep shale gas in China.

The shale gas sweet spot refers to the optimal exploration and development area or interval under current economic and technological conditions [9-10]. In recent years, domestic and foreign scholars have gradually become a hot topic in the layout of geological-engineering double sweet spots using more parameter comprehensive evaluation, achieving good results [11-21,37-40]. MA Xinhua (2018) and ZHANG Shaolong (2023) believe that the development of the "sweet spot layer" in the Longmaxi Formation in southern Sichuan has the characteristics of low density, high uranium thorium ratio, high quartz content, high organic carbon content, and high free gas content[12-13]; XU Chunbi (2017) established geological sweet spot index, engineering sweet spot index, and comprehensive sweet spot index formulas using organic carbon, porosity, Young's modulus, and Poisson's ratio as indicators [

14]. LIAO Dongliang (2020) proposed using organic carbon content, kerogen content, porosity, gas saturation, and pore pressure as geological sweet spot parameters, and mud content, brittleness index, carbonaceous content, and stress difference coefficient as engineering sweet spot parameters [

15]; JIANG Tingxue (2016) proposed a calculation method for geological sweetness and engineering sweetness based on the parameters of geological sweetness and engineering sweetness, and evaluated their correlation with production capacity; ZHU Douxing (2018) classified and evaluated geological "sweet spots" (structures, faults, TOC, total gas content, porosity, reservoir thickness, etc.) and engineering "sweet spots" (burial depth, dip angle, brittleness index, fractures, formation pressure, geostress, etc.) based on a total of twelve indicators, achieving the combination of geological "sweet spots" and engineering "sweet spots" and implementing shale gas "sweet spots". The evaluation indicators for desserts vary depending on the application scenarios in terms of factors considered, parameters selected, and specific divisions, but overall they can be divided into two categories: geological and engineering. In terms of geology, indicators such as source rock properties, reservoir physical properties, reservoir oil content, degree of reservoir fracture development, reservoir pressure, and reservoir size were mainly considered; In terms of engineering, the main considerations are the fracturability of the reservoir and the in-situ stress of the reservoir.

However, there are significant differences in geological-engineering conditions between different blocks, and requiring to consider the appropriate sweet spot evaluation parameters [

22]. The geological-engineering conditions in the Northern Luzhou Block are complex, and production data indicate that instability and dislocation of natural fractures or small faults often cause fracture slippage risk, which in turn causes casing deformation and reduces the EUR of individual wells [23-26,33-34]. Engineering risks have a significant impact on the effectiveness of shale gas wells, making the evaluation of engineering risk areas even more important. The core issue is how to make the geological-engineering sweet spot grading evaluation suitable for production and application needs.

Therefore, based on the analysis of the main controlling factors of the geological-engineering sweet spots of shale matrix in the deep block of Luzhou block, this article combines engineering risks to divide the geological-engineering sweet spots of shale gas reservoirs in the northern area of Luzhou block; The geological-engineering sweet spots of shale gas reservoirs is mainly controlled by two factors: (1) favorable geological conditions (reservoir thickness, fracture distribution, sedimentary characteristics, and physical properties); (2)precise engineering evaluation (brittleness characteristics, mechanical characteristics, stress characteristics, fracture slippage); Based on the above analysis, the author has established a geological engineering sweet spot and engineering risk assessment method and standard for shale matrix in the northern area of Luzhou block, completed the grading evaluation of geological-engineering sweet spots in shale gas reservoirs in the research area, and achieved good application results in well location deployment, development plan optimization and adjustment in the research area, in order to provide guidance for efficient development of deep shale gas reservoirs in southern Sichuan.

2. Overview of Exploration and Development

The Sichuan Basin has developed six sets of hydrocarbon source rock strata vertically, among which the Ordovician Wufeng Formation - Silurian Longmaxi Formation has achieved large-scale economic development in shallower areas (with burial depths of less than 3500 m) [

8,

27]. National shale gas demonstration areas such as Changning-Weiyuan and Zhaotong have been established. As shale gas exploration and development intensify, the deep areas (with a burial depth greater than 3500 m) of the Northern Luzhou Block have become an important strategic area for the sustained increase in reserves and production of shale gas in the Ordovician Wufeng Formation - Silurian Longmaxi Formation [

28].

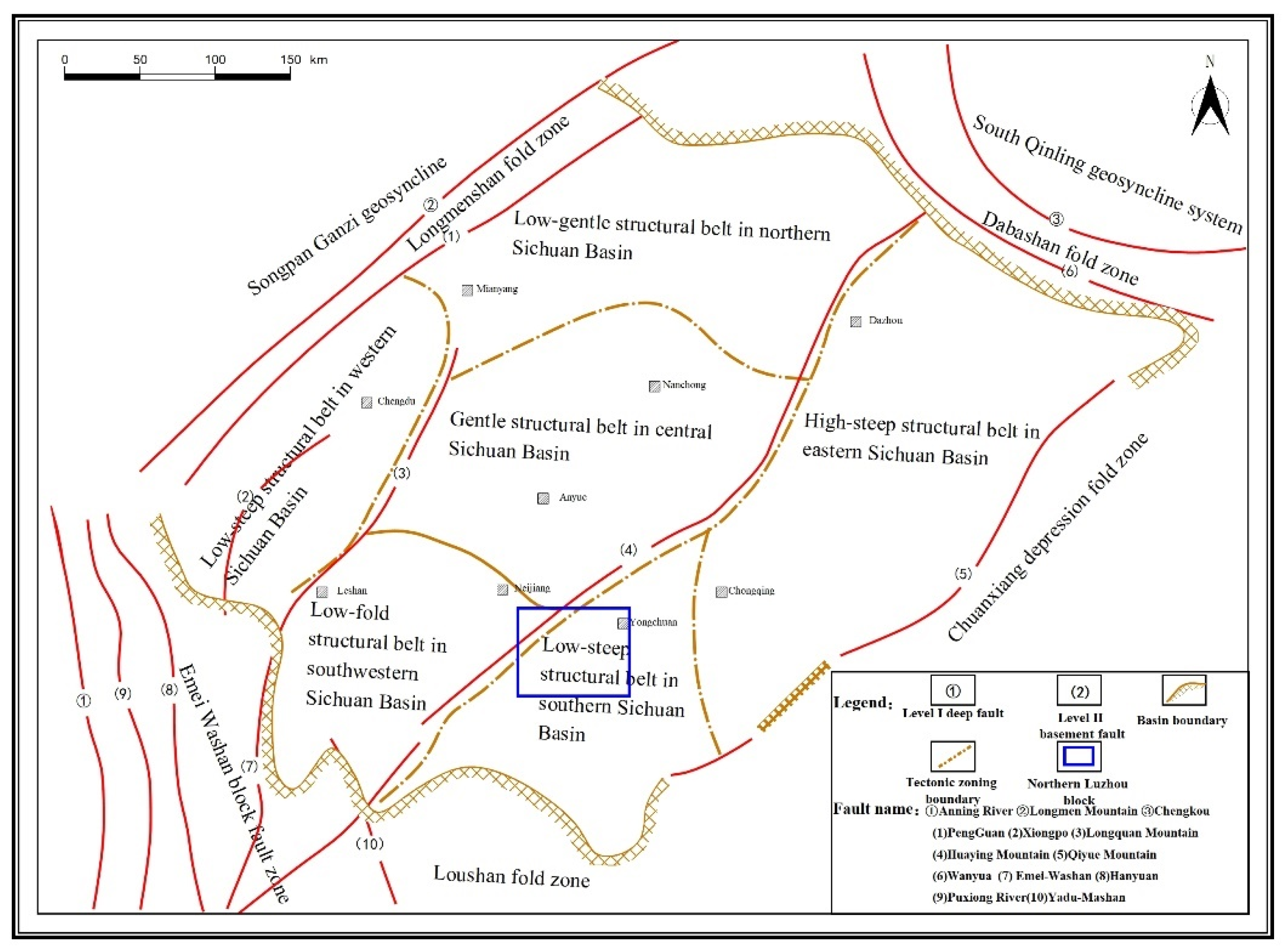

The Northern Luzhou Block is located at the junction of the low-steep structural zone of the Southern Sichuan Basin and the low-fold structural zone of Southwestern Sichuan Basin (

Figure 1). The structure is stable, gradually widening and flattening from north to south, with the folding intensity decreasing. The Ordovician Wufeng Formation - Silurian Longmaxi Formation in this area is located in the center of the deepwater shelf deposition. The continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs ranges from 7 to 18 m, gradually thickening from north to south, making it suitable for overall development.

However, casing deformation frequently occurs in the northern are, with a casing deformation rate as high as 50% in Well W06 and Well W14 zones. Affected by the casing deformation, the gas production of these wells has not met expectations, severely restricting the progress of deep-layer production capacity construction. Therefore, in order to guide the implementation of subsequent development plans and support the increase in shale gas reserves and production, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the distribution of geological-engineering sweet spots and engineering risk conditions in the northern area of the Luzhou block, and ultimately establish a graded evaluation system for development and production areas based on geological-engineering sweet spots.

3. Research Methods

The geological and engineering conditions in the Northern Luzhou Block are complex. Only through continuous iteration and deepening of geological understanding and accurate evaluation engineering risk conditions, can we provide favorable support for the geological-engineering sweet spots grading evaluation in the study area.

3.1. Geological Conditions

3.1.1. Stratigraphic Characteristics

The stratigraphic sequence in the northern Luzhou Block is normal, with thethickness of the Longmaxi Formation ranging from 400 to 600 m. Based on sedimentary cycles, lithological assemblages, electrical, paleontological, and geochemical characteristics, the Longmaxi Formation is divided into two members from top to bottom: Long 2 and Long 1. The Long 1 member is further subdivided into two submembers, Long 1-1 and Long 1-2, from bottom to top. The Long 1-1 submember is further divided into seven layers, labeled Long 1-11 to Long 1-17 from bottom to top. It consists primarily of organic-rich black carbonaceous shale, abundant in variously shaped graptolite fossils, with a thickness ranging from approximately 55 to 65 m, gradually thinning from east to west. The top of the Long 1-2 submember is characterized by a large interval of sandy mudstone interbeds or interlayers. In contrast, its bottom is delineated by dark gray shale from the underlying gray-black shale of the Long 1-1 submember, with a thickness ranging between 130 and 170 m.

3.1.2. Structural and Fault Characteristics

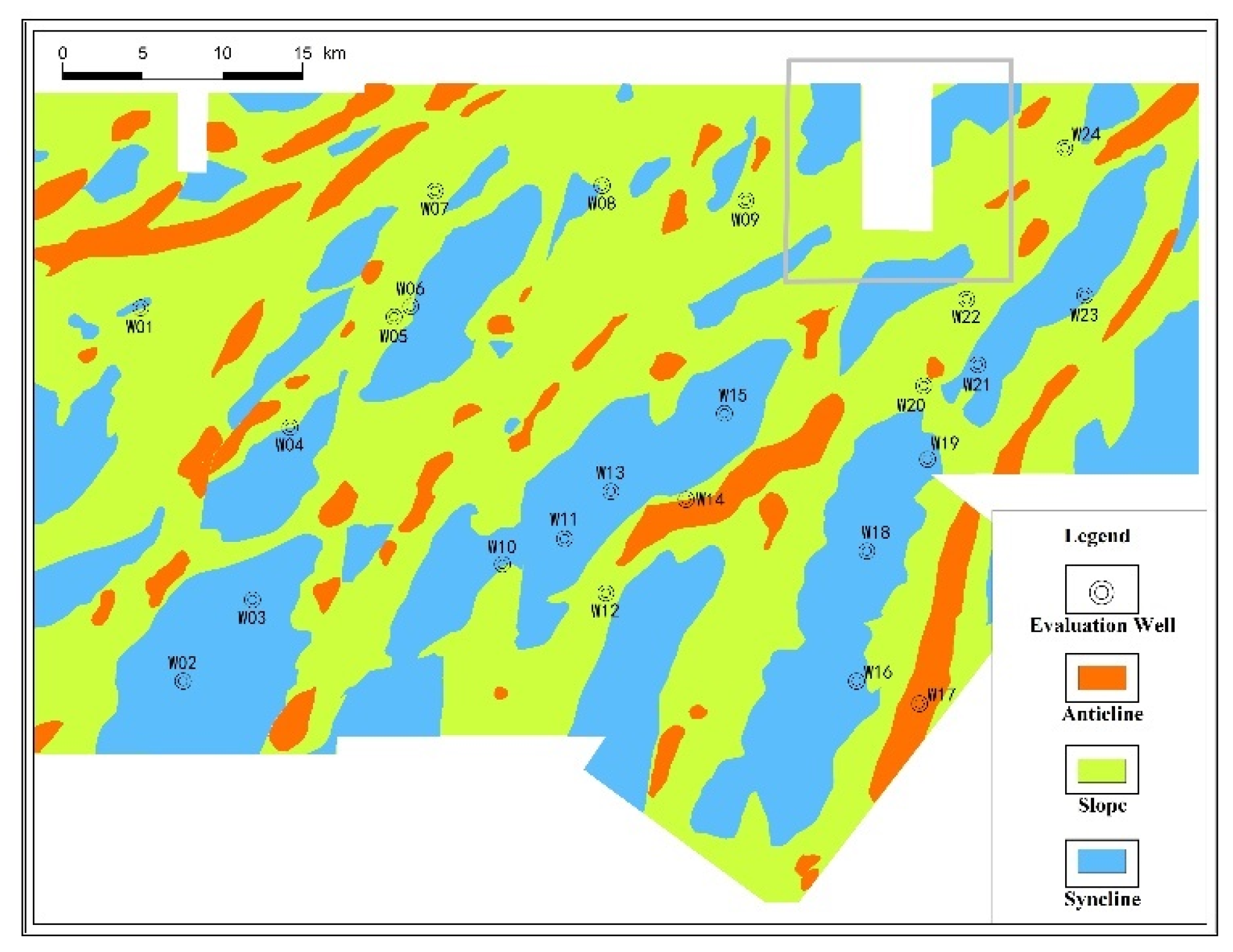

Due to the superposition of multiple tectonic movements, the structural faults in the Northern Luzhou Block exhibit complex fold characteristics. The southern segment of the Huayingshan tectonic belt spreads out in a broom-like pattern from northeast to southwest, presenting an overall tectonic pattern of “alternating grabens and horsts”. The structures in the Northern Luzhou Block can be divided into three types: synclines, slopes, and anticlines (

Figure 2). Six synclines, mainly including the Fuji and Desheng synclines, have been identified. The apparent dip angle of the strata in these synclines ranges from 0° to 5°, with poorly developed microstructures, covering an area of 1000.2 km². The apparent dip angle of the strata on the slopes ranges from 5° to 15°, with relatively well-developed microstructures, covering an area of 1646.8 km². Nine anticlines, mainly including the Luoguanshan and Yundingchang anticlines, have apparent dip angles greater than 15° and well-developed microstructures, covering an area of 260.6 km².

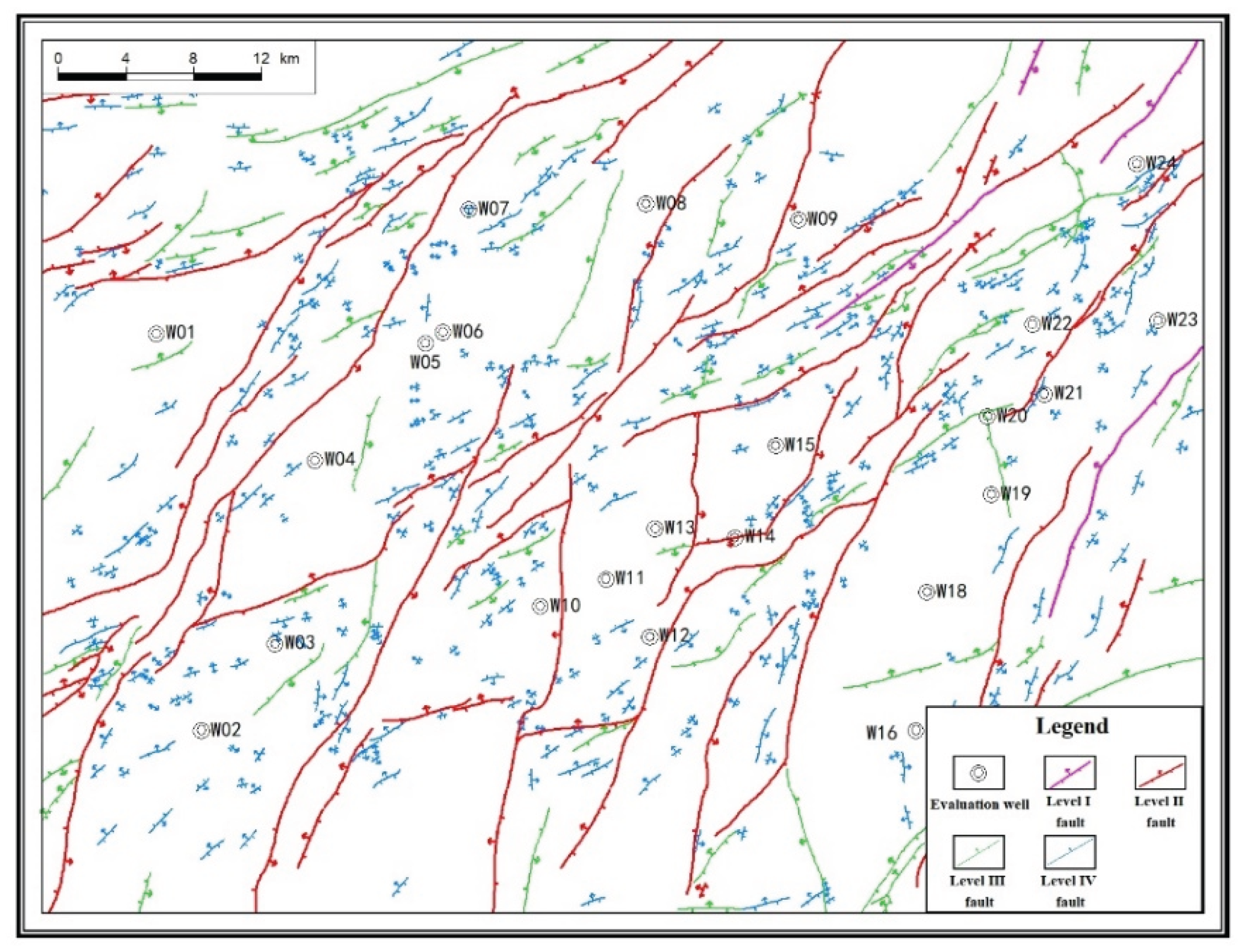

Under the superimposed effects of multiple tectonic activities, the faults in the study area exhibit characteristics of multiple stages, levels, and types (

Figure 3). Since the Indosinian period, the target stratum has mainly been affected by the superposition of tectonic stresses from three periods: the Indosinian, the late Yanshanian to early Himalayan, and the mid-to-late Himalayan. This has resulted in the formation of three sets of faults with orientations of nearly east-west (EW), northeast-southwest (NE-SW), and nearly north-south (NS) at the top of the Wufeng Formation [

29]. Faults can be classified into four levels (I, II, III, and IV) based on their displacement. Level I faults are large faults that extend upward to the surface and control the structure. Their seismic response is characterized by a clear disruption of the event axis, and there are relatively few Level I faults are developed in the study area. Level II faults are typically developed in the high parts of anticlines, with a planar extension exceeding 3.5 km. The vertical displacement between the upper and lower plates of the fault ranges from 100 to 300 m. The fault plane morphology is dominated by plate-type thrusts. The seismic response characteristics are the same as those of Level I faults, extending downward to the Cambrian salt layer and upward to the Silurian or Triassic. Level III faults are distributed in areas with wide and gentle synclines are less disturbed. They generally trend east-west (EW), with a planar extension exceeding 1 km. The vertical displacement between the lower wall and hanging wall ranges from 40 to 100 m. The fault plane morphology is primarily dominated by plate-type thrusts. The seismic response is characterized by a disruption of the event axis, extending downward to the Cambrian or basement and upward to the Silurian. Level IV faults are smaller in scale and are primarily distributed within synclines. Their planar extension is generally ranges from 0.4 and 1 km. The vertical displacement between the lower wall and hanging wall of the fault ranges from 20 to 40 m. The fault plane morphology is dominated by low-angle shovel-type thrusts, which generally only disconnect the Longmaxi Formation. The seismic response is characterized by a curved disruption of the event axis and secondary fold morphologies [

30]. Larger faults (Levels I and II) are generally distributed in the anticlines and slopes of the Northern Luzhou Block, while smaller faults (Levels III and IV) are primarily found within the synclines.

3.1.3. Sedimentary Characteristics

The Northern Luzhou Block is located within the depositional center of the deep-water shelf facies. Characteristic trace element data (U/Th > 1.25) indicates that the thickness of the strongly reducing deep-water deposits is generally greater than 4m. Based on lithology, electrical properties, sedimentary structures, paleontology, redox conditions, and other facies markers, the Wufeng Formation to the Long 1-1 submember is entirely within the deep-water shelf subfacies. This can be further subdivided into several microfacies types: limestone mud-shelf microfacies, argillaceous mud-shelf microfacies, organic-rich argillaceous mud-shelf microfacies, and organic-rich siliceous mud-shelf microfacies. Specifically, the organic-rich siliceous mud-shelf and organic-rich argillaceous mud-shelf microfacies are developed in the Wufeng Formation to the Long 1-14 layer. Meanwhile, the water depth of the Long 1-15-7 layers gradually becomes shallower, but the depositional center remains within the Northern LuzhouBlock throughout all substrata.

Table 1.

Sedimentary microfacies classification standards in the North Luzhou Block.

Table 1.

Sedimentary microfacies classification standards in the North Luzhou Block.

| Microfacies |

Sedimentary Environment |

GR

(API) |

Lithofacies |

Silica: Calcium: Clay (%) |

Layer |

Limestone

mud-shelf |

U/TH<0.75 |

128 |

Carbonate-bearing siliceous-argillaceous mixed shale |

45:2:53 |

The top of Long 1-16

|

Argillaceous

mud-shelf |

1.25>U/TH>0.75 |

177 |

Carbonate-bearing argillaceous-siliceous shale |

50:15:35 |

The top of Long 1-14 to Long 1-17 layer |

Organic-rich argillaceous

mud-shelf |

U/TH>1.25 |

230 |

Carbonate-bearing argillaceous siliceous shale; siliceous-argillaceous mixed shale |

55:10:35 |

Long 1-14 to Long 1-16 layer |

| Organic-rich siliceous mud-shelf |

U/TH>1.5 |

210 |

Clay-bearing siliceous shale;

siliceous shale |

65:25:10 |

Wufeng Formation to Long 1-13 layer |

3.1.4. Reservoir Characteristics

Based on reservoir quality and engineering conditions, the Wufeng Formation to the Long 1-1 submember is divided into two intervals: the lower intervals (Wufeng Formation to Long 1-14 layer) and the upper intervals (Long 1-15 to Long 1-17 layers). In the Northern Luzhou Block, the total organic carbon (TOC) content of the lower intervals ranges from 3.2% to 4.0%, while the TOC of the upper intervals ranges from 2.0% to 2.6%. The organic pores in the Wufeng Formation to the Long 1-1 submember are primarily circular or elliptical in shape, often developing in a networked, spongy, or beaded pattern. These organic pores are well-preserved, with pore sizes mainly distributed between 20 and 200 nm. Inorganic pores, on the other hand, tend to be nearly circular, square, diamond-shaped, or irregular, and are predominantly composed of calcite intraparticle pores and quartz interparticle pores, with pore sizes ranging from 30 to 1000 nm. The porosity of the lower intervals in this area ranges from 4.2% to 5.5%, while the porosity of the upper intervals is between 4.4% and 5.7%.

Table 2.

Reservoir characteristics of the Luzhou Block.

Table 2.

Reservoir characteristics of the Luzhou Block.

| Stratum |

Formation |

Type I Reservoir Thickness (m) |

Type I+II Reservoir Thickness (m) |

TOC

(%) |

Porosity

(%) |

Gas Saturation (%) |

Gas Content (m³/t) |

| Upper intervals |

Long 1-15-7 layer |

1~6 |

30~50 |

2.0~2.6% |

4.4~5.7% |

55~75 |

4.6~6.2 |

| Lower intervals |

Wufeng Formation to Long 1-13 layer |

7~18 |

21~30 |

3.2~4.0% |

4.2~5.5% |

50~65 |

5.0~7.0 |

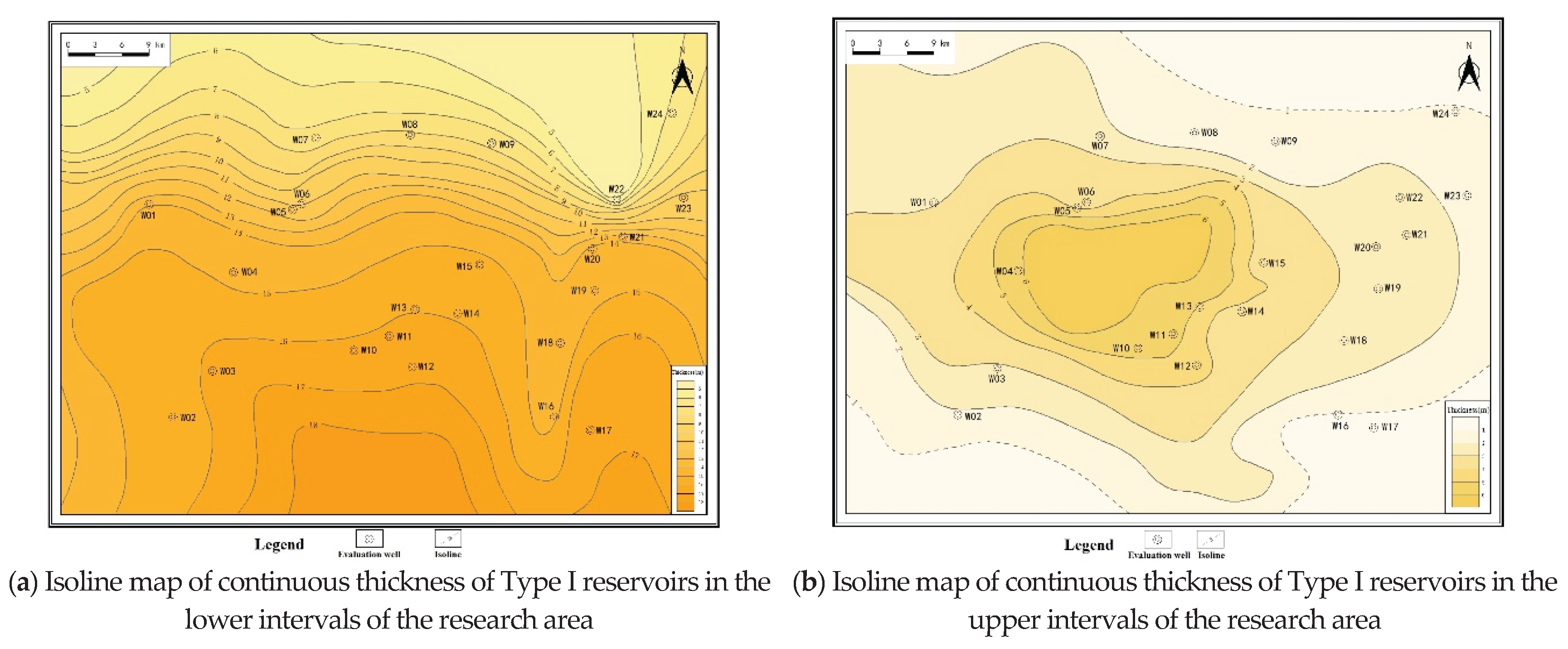

Based on the reservoir distribution characteristics of the upper and lower intervals in the Northern Luzhou Block, the cumulative thickness of Type I + II reservoirs in the lower interval ranges from 21 to 30 m, gradually thickening from the northeast to the southwest. For the upper interval, the thickness of Type I + II reservoirs ranges from 30 and 50 m, gradually thickening from west to east. In the lower intervals, the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs ranges from 7 to 18 m. The TOC of these reservoirs primarily ranges from 3.2% and 4.0%, with porosity between 4.2% and 5.5%, gas saturation between 50% and 65%, and gas content between 5.0 and 7.0 m³/t. The reservoir thickness gradually increases from northwest to southeast. In the upper intervals, the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs ranges from 1 and 6 m. The TOC of these reservoirs ranges from 2.0% and 2.6%, with porosity between 4.4% to 5.7%, gas saturation between 55% and 75%, and gas content between 4.6 and 6.2 m³/t. The reservoir thickness gradually increases from south to north (

Figure 4).

3.1.5. Development Characteristics of Natural Fractures

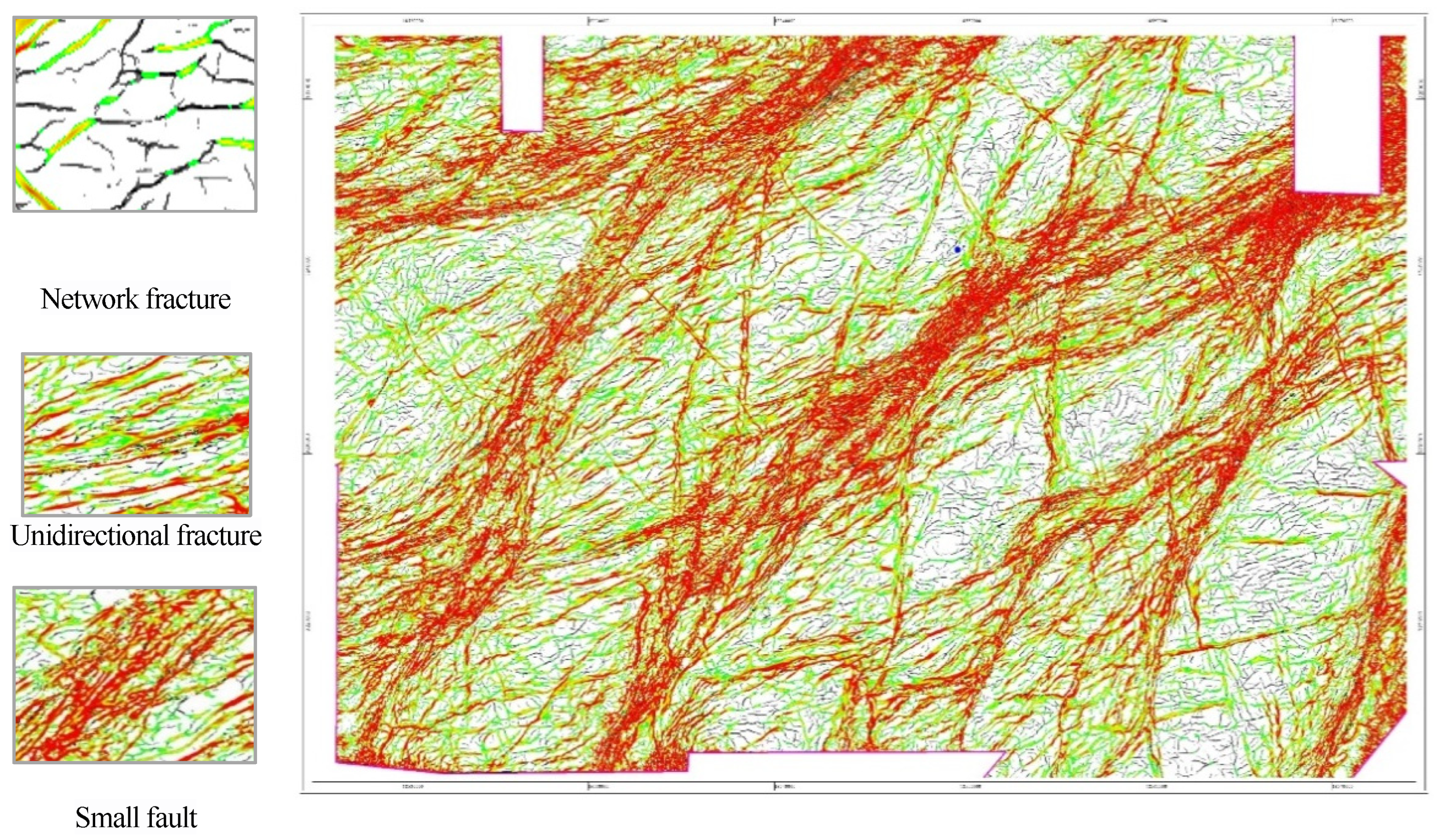

Natural fractures in shale represent another crucial reservoir space for shale gas. The distribution, characteristics, and patterns of these fractures play a significant role in shale gas flow and in evaluating the effectiveness of subsequent fracturing operations. In the absence of fractures, shale exhibits extremely low permeability. Fracture formation is primarily related to factors such as rock brittleness, hydrocarbon generation from organic matter, formation pore pressure, differential horizontal pressure, faults, and folds. The Northern Luzhou Block has a complex structure and has undergone multiple tectonic movements, including the Caledonian, Hercynian, Indosinian, and Himalayan movements. As a result, fractures are widely developed and often associated with faults. These fractures can be classified into three types: reticulate fractures, unidirectional fractures, and small faults, with each type occurring in distinct tectonic settings (

Figure 5). Reticulate fractures, formed during sedimentation and diagenesis, are mostly distributed in stable, gently dipping synclines, particularly in the Fuji and Desheng synclines. They are frequently associated with Level III and IV faults. Unidirectional fractures, formed due to tectonic processes, predominantly occur in narrow slopes and steep anticlines, especially in areas like the northern part of the Fuji syncline and the Baozang syncline. They are controlled by and often accompanied by Type I and II faults. Based on single-well gas production and fracturing data, it is evident that the development of natural fractures is beneficial for increasing gas production. However, the presence of larger-scale natural fractures around the well can lead to complex engineering phenomena such as reduced drilling target accuracy and casing deformations.

3.2. Engineering Conditions

3.2.1. Rock Brittleness Characteristics

The rock minerals in the study area mainly consist of quartz, feldspar, carbonate minerals, clay minerals, and pyrite. The lower intervals are primarily composed of siliceous shale, with a brittle mineral content ranging from 59% to 77.6%. The silicon primarily originates from biological processes. The upper intervals, on the other hand, are dominated by argillaceous shale, which has a lower brittle mineral content, ranging from 47.9% to 65.3%. In these intervals, there is an increase in terrestrial components contributing to the silicon content.. A comparison of brittle mineral content between the upper and lower intervals indicates that the lower intervals have a higher brittle mineral content, making the shale more brittle and more prone to fracturing under external stresses.

3.2.2. Rock Mechanics Characteristics

The strength characteristics of shale affect both the stability of the wellbore wall and the feasibility of fracturing, while the deformation characteristics influence the integrity of the wellbore. Based on triaxial compression test data from single-well cores in the study area, the Young’s modulus of the Long 1-11 layer in the Northern Luzhou Block ranges from 3.685 to 5.004×104 MPa, with an average value of 4.316×104 MPa. The Poisson’s ratio ranges from 0.195 and 0.315, with an average of 0.234. Overall, the reservoir exhibits a high Young’s modulus and a low Poisson’s ratio, indicating significant brittleness. This suggests that the shale is prone to fracturing, which favors the formation of a complex fracture network.

3.2.3. Stress Characteristics

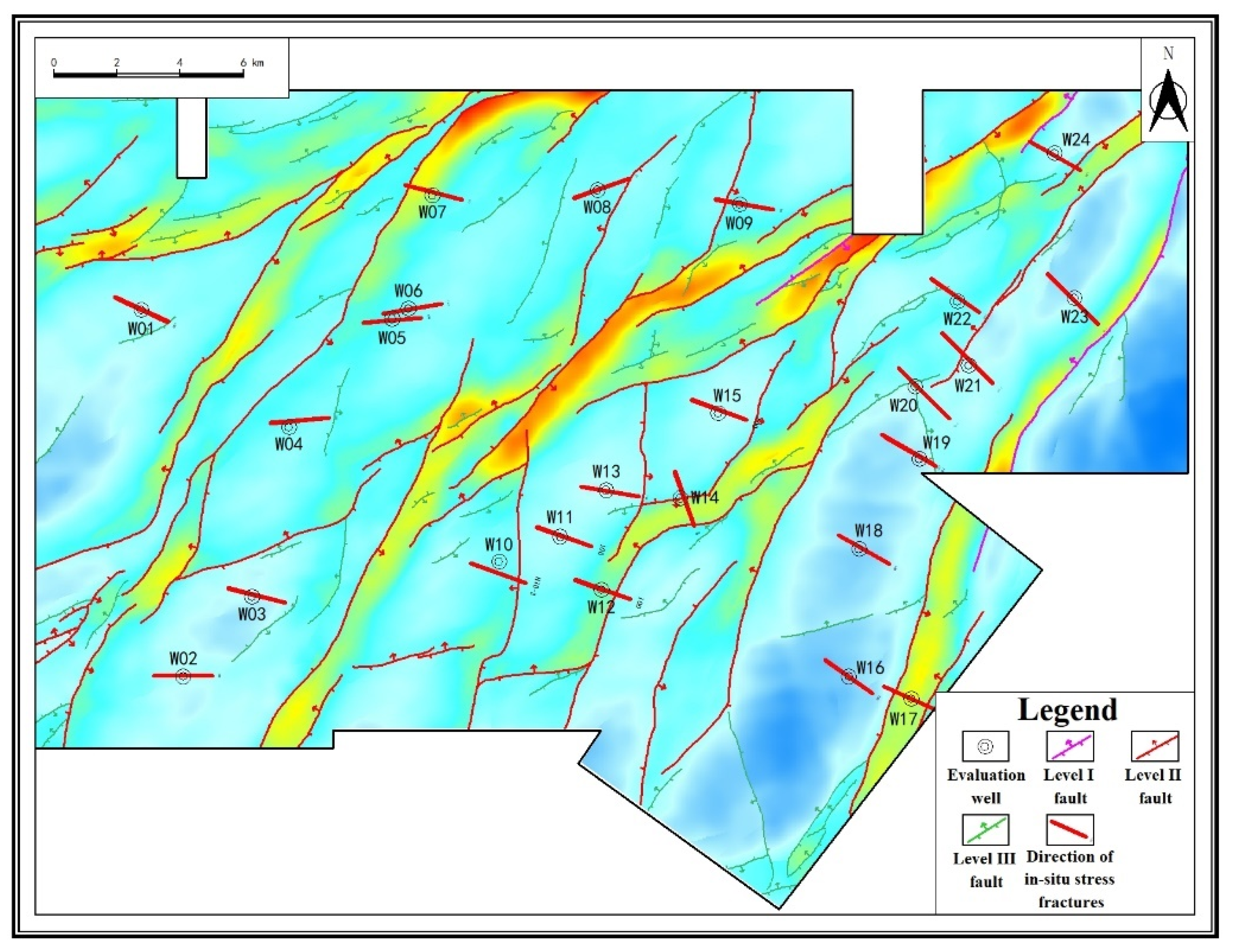

Due to multiple tectonic activities and various types of fault interactions, the ground stress in the deep shale reservoir of Luzhou Block exhibits complex characteristics, including large differences in triaxial stress, rapid directional changes, and a strike-slip stress state. Based on geo-stress experiments conducted on typical wells, indicate the magnitude, direction, and state of reservoir stress are primarily controlled by tectonics and faults. In the Northern Luzhou Block, the horizontal maximum principal stress (112.7 MPa) is greater than the vertical principal stress (106.6 MPa), which in turn is greater than the horizontal minimum principal stress (98.8 MPa). This indicates a strike-slip stress state (

Table 3). Faults significantly influence stress distribution, with stress values within the faults being lower than those in the surrounding strata. Stress concentration often occurs at fault branches and inflection points. Gentle synclines, unaffected by tectonic deformation, exhibit a horizontal maximum principal stress direction that is nearly east-west (85-110°). In contrast, narrow synclines and tectonic highs show a horizontal maximum principal stress direction perpendicular to the long axis of the tectonic structure (

Figure 6). The horizontal differential stress in the study area ranges from 9.61 to 16.17 MPa, which is higher than that in the Changning and Weiyuan Blocks.

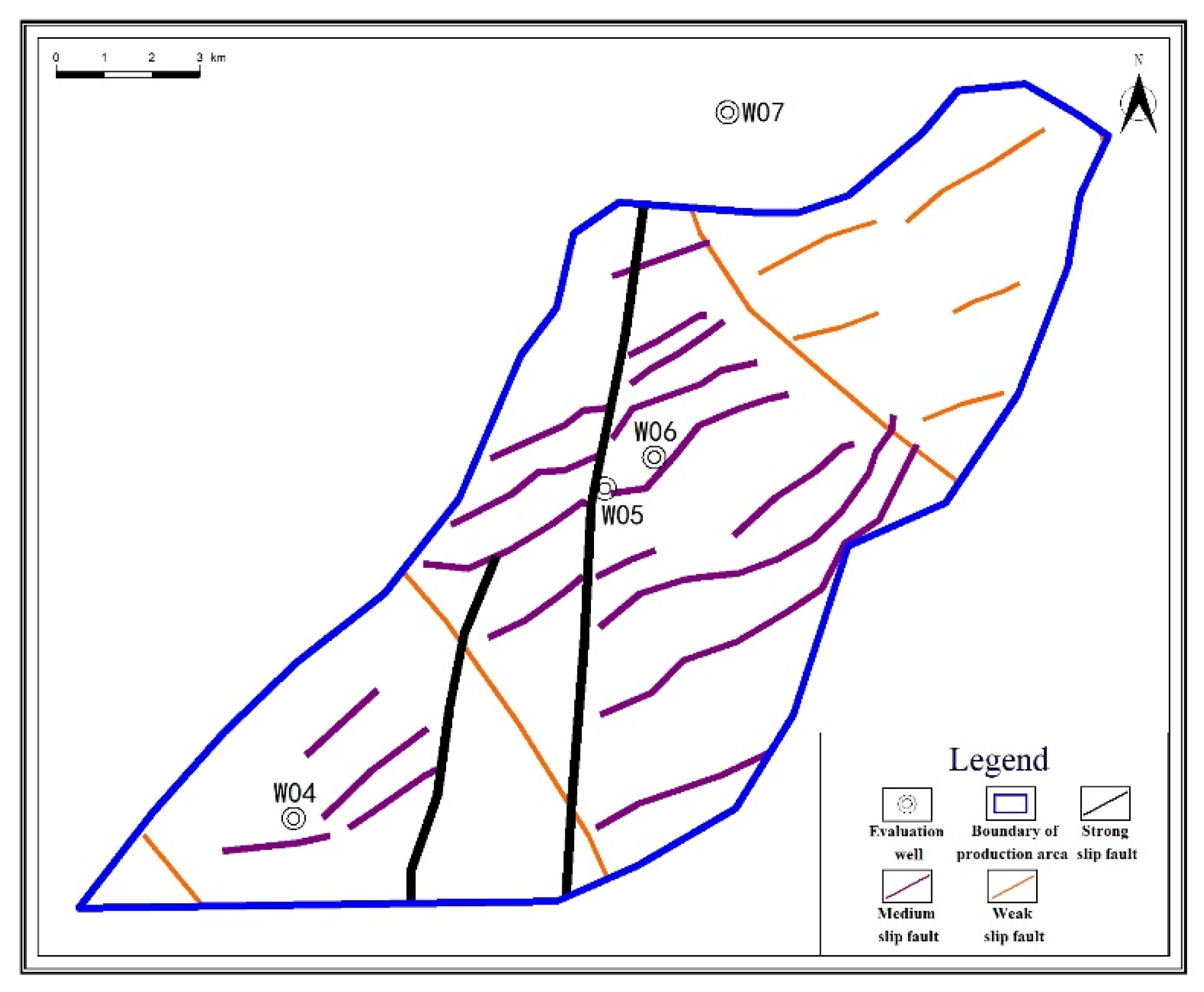

3.2.4. Risk of Fault Slippage

Research indicates that fault slippage is the primary factor influencing casing deformation in the Northern Luzhou Block. To evaluate the severity of fault slippage in this region, several evaluation indicators have been selected: the angle between the direction of ground stress and the fault strike, the fault dip angle, the friction coefficient, and the critical injection pore pressure. These indicators are assigned different weights based on their characteristics (

Table 4). (1) Angle between ground stress direction and fault strike: Fault activity increases when this angle is small, indicating more stringent geological conditions. A weight of 0.45 is assigned to this indicator. (2) Fault dip angle: Fault instability can occur when the dip angle ranges from 0° to 90°, but higher dip angles show a greater tendency for instability. Most faults in the Northern Luzhou Block have dip angles greater than 60°, indicating fewer geological constraints. A weight of 0.3 is assigned to this indicator. (3) Friction coefficient: Based on previous physical experiments and literature reviews[

3], the friction coefficient of open faults in the shale of the Northern Luzhou Block ranges from approximately 0.5 to 0.7, with a relatively small variation. A weight of 0.15 is assigned to this indicator. (4) Critical injection pore pressure: This evaluation indicator requires high-quality single-well data, and experimental data is limited. Only low-risk well data is considered, so a weight of 0.1 is assigned to this indicator.

Using the evaluation method described, an assessment of fault slippage was conducted in four production areas: Well W06, W02, W08, and W14 zones. Based on the evaluation, three categories of fault slippage were identified: strong slip faults, medium slip faults, and weak slip faults.

The evaluation results indicate that the Well W06 zone in the Northern Luzhou Block has the most developed slippage faults, followed by the Well W02 and W08 zones with moderately developed slippage faults. In contrast, the Well W14 and W01 zones show relatively less developed slippage faults. Specifically, 11 strong slip faults, 28 medium slip faults, and 38 weak slip faults were identified. Strong slippage faults are mainly distributed in the Well W06 zone (2 faults), the Well W02 zone (5 faults), and the central and eastern parts of the Well W14 zone (3 faults). Medium slippage faults are primarily located in the Well W06 zone (18 faults). Weak slippage faults are predominantly found in the Well W14 zone (12 faults), the northern Well W06 zone (8 faults), and the Well W08 zone (5 faults). Due to confidentiality reasons,

Figure 7 only shows the evaluation results for slippage faults in the Well W06 zone.

3.3. Evaluation Methods of Geological-Engineering Sweet Spots

3.3.1. Evaluation of Sweet Spots in Shale Matrix Geological-Engineering

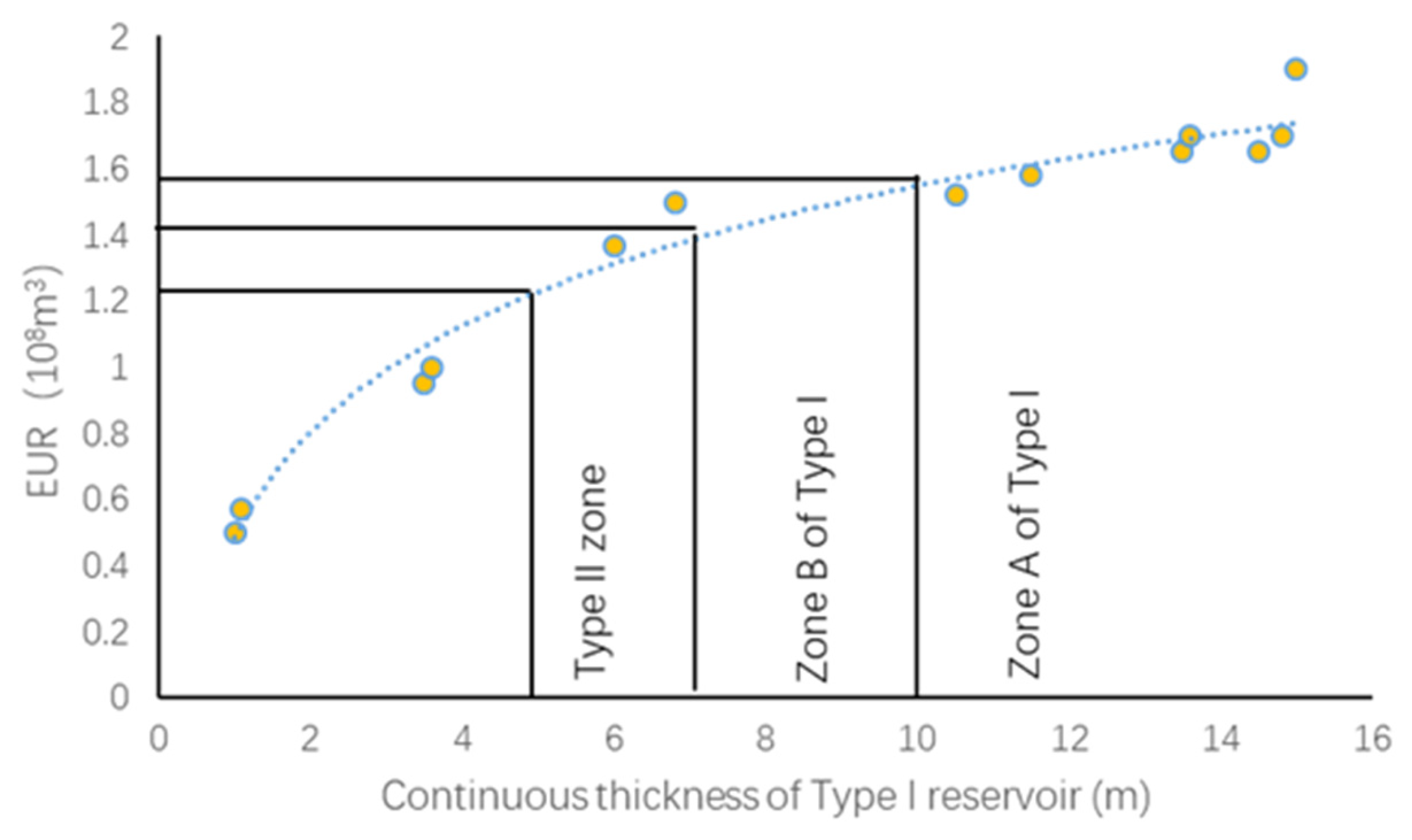

According to the analysis of the production effects in the northern area of the Luzhou Block, there is a good correlation (

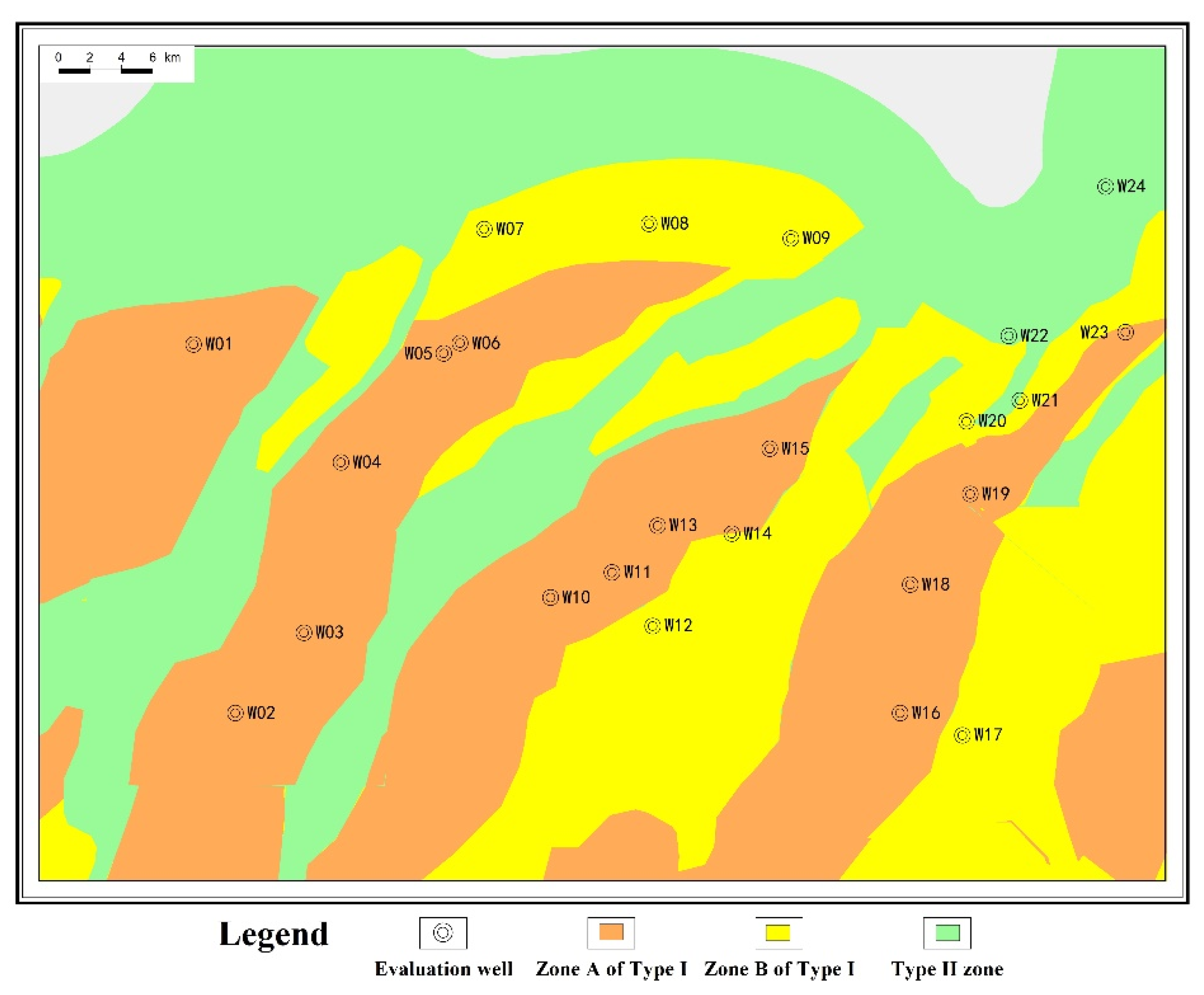

Figure 8), mainly a positive correlation, between the EUR of shale gas wells (excluding those with complex engineering conditions) and the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs. By combining the analysis of geological and engineering conditions, the evaluation indicators for geological-engineering sweet spots are optimized from four aspects: reservoir quality, rock pressability, structural and fault characteristics, and natural fracture characteristics. The "continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs, structural positions, fault scales, and natural fracture type characteristics" are selected as the classification evaluation indicators for geological-engineering sweet spots in the study area. The northern area of the Luzhou Block is divided into three types of geological-engineering sweet spot areas: " Zone A of Type I, Zone B of Type I, and Type II " (

Figure 9).

In Zone A of Type I, the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 10m, mainly characterized by wide and gentle synclines. Faults of Grade IV, III, II, and I are underdeveloped, and network fractures are predominant. Zone B of Type I can be divided into two situations. Firstly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 7m, the natural fractures are mainly network fractures, and faults of Grade IV, III, II, and I are underdeveloped. Secondly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 10m, the network fractures are underdeveloped, while faults of Grade IV and III are relatively more developed.There are four situations in the Type II Area. Firstly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 5m, it is mainly composed of narrow slopes and faulted anticlines, located near the high structural parts. Faults of Grade III are relatively more developed, and network fractures are underdeveloped. Secondly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 5m, faults of Grade III, II, and I are underdeveloped, and network fractures are well-developed. Thirdly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 7m, faults of Grade IV and III are developed, and network fractures are underdeveloped. Fourthly, when the continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs is greater than 10m, in the complex fault block areas, faults of Grade III and II are developed, and network fractures are underdeveloped.

The Zone A of Type I in the Northern Luzhou Block spans approximately 1,340 km² and is mainly distributed in the synclinal parts of the Well W01 zone, Well W06-W04-W03 zones, Well W15-W13-W11-W10 zones, and the Well W23-W19-W18 zones. The Zone B of Type I spans approximately 1,039 km² and is primarily located in the Well W07-W08-W09 zones, Well W20-W14-W12 zones, and the eastern side of the Well W19-W18 zones, specifically within the Yunjin Syncline. The Type II Zone, covering an area of about 938 km², is mainly distributed in the northern area and in the high structural positions of the faulted anticlines.

3.3.2. Engineering Risk Assessment

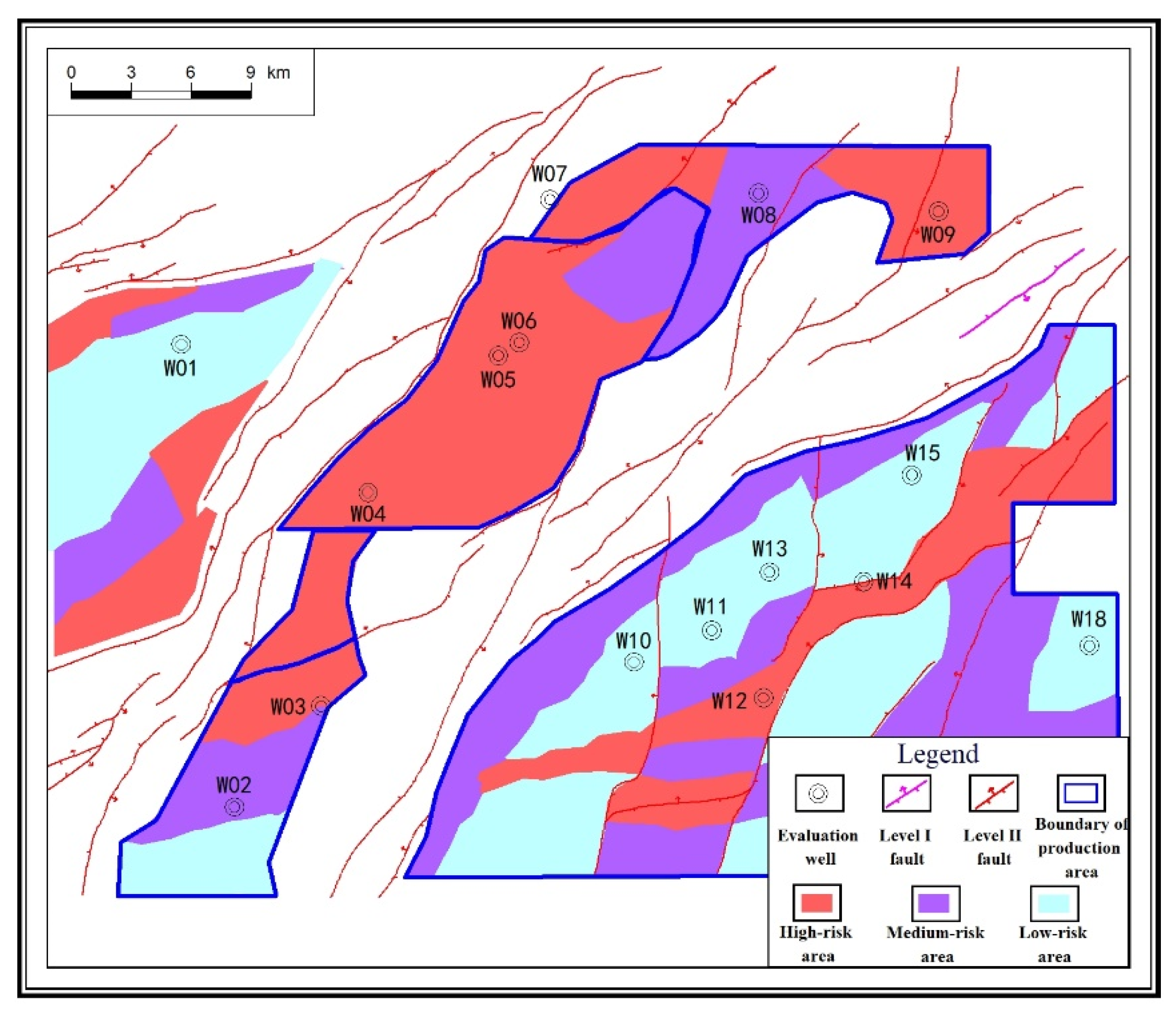

Affected by multiple tectonic movements, multilevel faults, and complex in-situ stress, frequent casing failures occur in shale gas wells within the production areas of the northern Luzhou block. This not only reduces the Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) of individual wells but also shortens their service life, constraining the progress of deep shale gas production capacity construction. Studies indicate that the stability of shale reservoir geological bodies is the primary cause of development engineering complexity, with fault slip potential in the target formation being the key influencing factor. Thus, the distribution characteristics of slip-prone faults serve as the core indicator for engineering risk classification, which is divided into three categories:

High-risk areas: Densely developed strong slip-prone faults, located in structurally high positions (minor-amplitude structural zones), with Grade II and higher faults, dominated by unidirectional fractures;Medium-risk areas: Moderately/weakly developed slip-prone faults with relatively dense distribution, located in slope zones (moderately developed minor-amplitude structures), dominated by Grade III faults and unidirectional fractures;Low-risk areas: Poorly developed slip-prone faults, located in slope zones (moderately developed minor-amplitude structures), dominated by Grade IV/V faults and network fractures.

Currently, the northern Luzhou block comprises five main production areas: W06, W02, W08, W14, and W01 well areas. To guide differentiated well placement and refined fracturing design, a hierarchical risk assessment was conducted, delineating a total engineering risk area of 950.8 km² (

Figure 10):

High-risk areas (274.3 km²): Distributed around wells W03, W06, W07, W09, W12, and W14, as well as in the structurally high northern and southern parts of the W01 well area;Medium-risk areas (381.9 km²): Located in the slope zone of the W14 well area and adjacent to Grade II/III faults;Low-risk areas (294.6 km²): Distributed in the synclinal zones of W01, W02, W14, and W18 well areas.

Affected by multiple phases of tectonic movements, multi-level faults, and complex in-situ stress conditions and other geological engineering factors in the northern area of the Luzhou block, casing failures frequently occur in the shale gas wells within the production area. This not only reduces the Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) of individual wells but also shortens the well's life cycle. Consequently, it restricts the progress of deep shale gas production capacity construction.Studies have indicated that the stability of the geological bodies in the shale reservoir is the most crucial factor contributing to the complexity of shale gas development projects. Among these factors, the fault slip characteristics of the target formation are the most significant influencing factor. Therefore, the distribution characteristics of the slip faults are taken as the main indicator for evaluating engineering risks.Engineering risks are classified into three categories: high, medium, and low. In high-risk areas, strong slip faults are well-developed and densely distributed. These areas are generally located at the structural highs, with the development of micro-reliefs. Faults of Grade II and above are present, and it is an area where unidirectional fractures are developed. In medium-risk areas, moderately and weakly developed slip faults are densely distributed. These areas are typically located in the slope zones, with relatively well-developed micro-reliefs. Grade III faults are predominant, and the block is mainly characterized by unidirectional fractures. In low-risk areas, slip faults are underdeveloped. These areas are generally located in the slope zones, with relatively well-developed micro-reliefs. Grade IV and V faults are predominant, and the area is characterized by a network of fractures.

4. Results

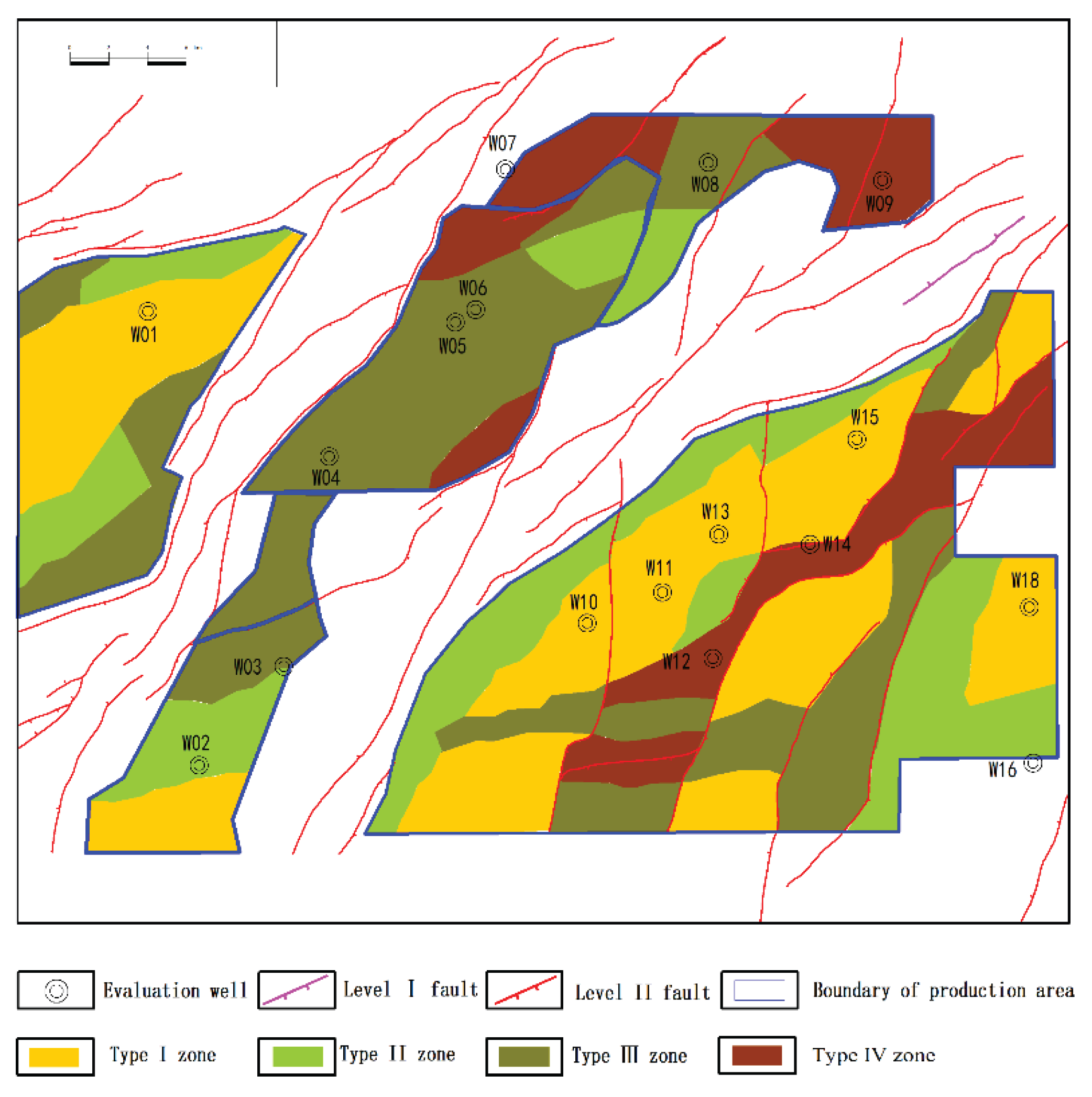

Geological-engineering sweet spots in the shale matrix form the foundation for high-yield shale gas wells, while the development of natural weak planes due to strong shale heterogeneity introduces engineering complexities, often resulting in suboptimal well performance. Accurate evaluation of these sweet spots therefore requires integrating both matrix sweet zones and engineering risks from natural weak planes. Adopting the concept of "multi-factor coupling control units" [

37], this study overlays matrix sweet spot classification results with engineering risk assessments of natural weak planes, dividing the northern Luzhou block's production areas into four geological-engineering sweet spot Type (I, II, III, Ⅳ) to inform development plan optimization:

Type I (Type I Sweet Spots–Low-Risk Overlap): Covers 365 km², distributed in the central W01 well area, southern W02 well area, W10-W11-W13-W15 well cluster, W18 well area, and eastern W12 well area.Type II (Type IA Sweet Spots–Medium-Risk Overlap): Covers 244 km², distributed in the northern/southern W01 well area, central W02 well area, southern W08 well area, western W10-W11-W13-W15 well cluster, and southwestern W18 well area.Type III (Type IA Sweet Spots–High-Risk / Type IB Sweet Spots–Medium-Risk Overlap): Covers 357 km², distributed in the northern/southern W01 well area, W03-W07 well areas, central W08 well area, W12 well area, and southern fringe of the W14 well area (

Figure 11). Type Ⅳ (Type IB Sweet Spots–High-Risk Overlap): Covers 174 km², distributed in the eastern/western W08 well area, W12 well area, and W14 well area.

5. Discussion

Shale gas production is governed by a multitude of factors, which can be broadly categorized into geological and engineering aspects. Accurate evaluation of the integrated geological-engineering “sweet spots” in shale reservoirs is therefore critically important. In this study, targeting deep shale gas in the southern Sichuan Basin, we applied a principal controlling factor analysis approach to identify key geological sweet spot indicators, including continuous thickness of Type I reservoirs, fracture type, and regional structural characteristics. Given the limited variation in conventional compressibility parameters—such as rock mechanical properties and brittle mineral content—across the study area, we instead selected engineering and risk-related parameters as evaluation criteria for engineering sweet spots. These include structural setting, characteristics of natural and slip fracture distributions, and micro-amplitude structural features. By integrating the geological and engineering sweet spot assessments, a coupled evaluation methodology for dual sweet spot identification was established.

While this approach demonstrates strong applicability to deep shale gas blocks in the southern Sichuan Basin, its transferability to other regions with simpler geological and engineering conditions may be limited. Several shortcomings are noted: the current geological sweet spot evaluation does not account for shale reservoir fluidity indicators; likewise, the engineering assessment overlooks the influence of natural weak planes (e.g., bedding and micro-fractures) and fracturing fluid interactions on traditional compressibility metrics. Moreover, a single evaluation standard is insufficient to address diverse geological-engineering settings. For future improvement, big data and artificial intelligence offer promising pathways for developing adaptive sweet spot evaluation criteria tailored to varying reservoir models.

6. Conclusions

(1) The northern Luzhou block exhibits favorable geology but complex engineering challenges, with frequent casing failures degrading well performance. By analyzing controlling factors, this study established evaluation methods for matrix sweet spots and engineering risks, integrating them to define four classes of geological-engineering sweet spots for scientific development.

(2) The lower formation in the northern block was deposited in a strongly reducing environment, yielding high-quality reservoirs: continuous Class I reservoir thickness of 7–18 m, high brittleness, Young’s modulus of 3.685×10⁴–5.004×10⁴ MPa, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.195–0.315, indicating excellent fracability. Multi-phase tectonism resulted in multi-period, multi-level, and multi-type faults, accompanied by diverse natural fractures. Current reservoir conditions feature large horizontal stress differences, rapid stress orientation changes, and strike-slip stress states, increasing fault slip and casing failure risks.

(3) Fault slip evaluation indices (angle between in-situ stress and fault strike, fault dip, friction coefficient) were defined, identifying 11 strong-slip, 28 moderate-slip, and 38 weak-slip faults.

(4) Based on comprehensive geo-engineering analysis, "continuous Class I reservoir thickness, structural position, fault scale, and natural fracture characteristics" were selected as matrix sweet spot indicators, dividing them into Type IA, IB, and II. Engineering risks were classified into high/medium/low categories using slip fault distributions. Integration yielded four geological-engineering sweet spot Typees (I, II, III, Ⅳ).

(5) Development plans were optimized using sweet spot classifications:Type I/II areas (W14, W01 well areas): Prioritized production in low-risk zones;Type III areas (W06 well area): Phased deferral with pilot testing for high-risk zones;Type Ⅳ areas (W08, W14 well areas): Real-time adjustments based on W06 pilot insights to meet "14th Five-Year Plan" production and capacity targets.

References

- ZOU, C.H.; ZHU, R.K.; DONG, D.Z.; WU,S. T.; Scientific and Technological Progress, Development Strategy and Policy Suggestion Regarding Shale Oil and Gas. ACTA PETROLEI SINICA 2022, 43, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, J.C.; SHI, M.; WANG, D.S.; TONG,Z. Z.;HOU,X.D.; Fields and Directions for Shale Gas Exploretion in China. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- JIA, C.Z. ; Development Challenges and Future Scientific and Technological Researches in China's Petroleum Industry Upstream. ACTA PETROLEI SINICA 2020, 41, 1445–1464. [Google Scholar]

- XIE, J. ; Rapid Shale Gas Development Accelerated by the Progress in Key Technologies: A Case Study of the Changning-Weiyuan National Shale Gas Demonstration Zone. Natural Gas Industry 2017, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUO, T.L.; XIONG, L.; LEI, W. ZHAO,Y.;PANG,H.Q.; Deep Shale Gas Exploration and Development in the Weirong and Yongchuan Areas, South Sichuan Basin: Progress, Challenges and Prospec. Natural Gas Industry 2022, 42, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- DAI, Q. ; Analysis of Production Casing Damage Reasons During Testing and Completion of Shales Gas Well. Drilling & Production Technology 2015, 38, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- GUO, J.C.; LU, Q.L.; HE, Y.W. ; Key Issues and Explorations in Shale Gas Fracturing. Natural Gas Industry 2022, 42, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YANG, H.Z.; ZHAO, S.X.; LIU, Y.; WU,W. ;XIA,Z.Q.; Main Controlling Factors of Enrichment and High-Yield of Deep Shale Gas in the Luzhou Block, Southern Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry 2019, 39, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU, D.H.; JIAO Fangzheng. Evaluation and Prediction of Shale Gas Sweet Spots: A Case Study in Jurassic of Jiannan Area, Sichuan Basin. PETROLEUM GEOLOGY & EXPERIMENT 2012, 34, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- YANG, Z.; HOU, L.H.; TAO, S.Z.; CUI,J. W.;WU,S.T.; Formation Conditions and “Sweet Spot ” Evaluation of Tight Oil and Shale Oil. PETROLEUM EXPLORATION AND DEVELOPMENT 2015, 42, 555–565. [Google Scholar]

- ZOU, C.N. ; Unconventional Hydrocarbon Geology(Second Edition). Geology Press, Beijing, 2013.

- MA, X.H. ; Enrichment Laws and Scale Effective Development of Shale Gas in the Southern Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry 2018, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, S.L.; YAN, J.P.; GUO, W.; ZHONG,G. H.;Huang,Y.; Logging Evaluation Method of Geological-Engineering Sweet Spot Parameters for Deep Shale Gas Based On Petrophysical Facies: A Case Study of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in Lz Block of Sichuan Basin. Petroleum geophysical exploration 2023, 58, 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- XU, C.B.; XIAO, H.; YANG, D.P.; BA,Y. ;Compressibility Evaluation of Longmaxi Shale Reservoir in Ydn Area Based On Comprehensive Dessert Index. Journal of Chongqing University of Science and Technology (Natural Sciences Edition) 2017, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- LIAO, D.L. ; Evaluation Methods and Engineering Application of the Feasibility of “Double Sweet Spots”in Shale Gas Reservoirs. PETROLEUM DRILLING TECHNIQUES 2020, 48, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- TINNIN B, MCCHESNEY M D, BELLO H. Multi-Source Data Integration: Eagle Ford Shale Sweet Spot Mapping//Unconventional Resources Technology Conference. 2015.

- Ter HEEGE J, ZIJP M, NELSKAMP S, et al. Sweet Spot Identification in Underexplored Shales Using Multidisciplinary Reservoir Characterization and Key Performance Indicators: Example of the Posidonia Shale Formation in the Netherlands. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2015, 27, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CUDJOE S, VINASSA M, HENRIQUE BESSA GOMES J, et al. A Comprehensive Approach to Sweet-Spot Mapping for Hydraulic Fracturing and Co 2 Huff-N-Puff Injection in Chattanooga Shale Formation. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2016, 33, 1201–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUEVARA J, ZADROZNY B, BUORO A, et al. A Machine-Learning Methodology Using Domain-Knowledge Constraints for Well-Data Integration and Well-Production Prediction. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering.

- JIANG, T.X.; BIAN, X.B. ; The Novel Technology of Shale Gas Play Evaluation-Sweetness Calculation Method. PETROLEUM DRILLING TECHNIQUES 2016, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ZHU, D.X.; JIANG, L.W.; NIU, W.T.; JIAN,Z. C.;HANG,B.; Seismic and Geological Integration Applied in the Shale Gas Exploration. Oil Geophysical Prospecting 2018, 53, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- NIE, H.K.; HE, Z.L.; LIU, G.X.; DU,W. ;WANG,R.Y.; Genetic Mechanism of High-Quality Shale Gas Reservoirs in the Wufeng–Longmaxi Fms in the Sichuan Basin. NATURAL GAS INDUSTRY 2020, 40, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- LI, L.W.; WANG, G.C.; LIAN, Z.H.; ZHANG,L. ;MEI,J.; Deformation Mechanism of Horizontal Shale Gas Well Production Casing and its Engineering Solution: A Case Study On the Huangjinba Block of the Zhaotong National Shale Gas Demonstration Zone. Natural gas industry 2017, 37, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN, Z.W.; FANG, C.; ZHU,Y. ;XIANG,D.G.; Deformation Characteristics and Stress Modes of Casings for Shale Gas Wells in Sichuan. CHINA PETROLEUM MACHINERY 2020, 48, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- YIN, F.; HAN, L.L.; CHEN, Y.J.; YANG,S. Y.;SHI,B.B.; Assessment of Casing Deformation and Optimization of Cement Sheath Performance Under Fracturing Shale Gas Wells. PETROLEUM TUBULAR GOODS & INSTRUMENTS 2020, 6, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- MAO, L.J.; LIN, H.Y.; YU, X.Y.; MAI,Y. ; Influence of Fault Slip On Casing Deformation of Horizontal Well in Shale Gas Reservoir. FAULT-BLOCK OIL & GAS FIELD 2021, 28, 755–760. [Google Scholar]

- HE, X.; CHEN, G.S.; WU, J.F.; LIU,Y. ;WU,S.;Deep Shale Gas Exploration and Development in the Southern Sichuan Basin: New Progress and Challenges. Natural Gas Industry 2022, 42, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG, S.R.; DONG, D.Z.; LIAO, Q.S.; SUN,S. S.;HUANG,S.S.;Geological Characteristics and Resource Prospect of Deep Marine Shale Gas in the Southern Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- TANG, X. ; Tectonic Control of Shale Gas Accumulation in Longmaxi Formation in Southern Sichuan Basin. Xuzhou, Jiangsu: China University of Mining and Technology 2018, 211.

- MA, S.J.; ZENG, L.B.; SHI, X.W.; WU,W. ;TIAN,H.; Characteristics and Main Controlling Factors of Natural Fractures in Marine Shale in Luzhou Area, Sichuan Basin. Eart Science 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- HE, C.R. ; VERBERNE BA, SPIERS CJ. FRICTIONAL Properties of sedimentary rocks and natural fault gouge from longmenshan fault zone and their implications. Chinese Journal of Rock Mechanics and Engineering.

- Zeng, L.B. , Lyu, P., Qu, X.F., et al. Multi-Scale Fractures in Tight Sandstone Reservoirs with Low Permeability and Geological Conditions of Their Development. Oil & Gas Geology 2020, 41, 449–454 (in Chinese with English abstract), (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.S. , Zeng, L.B., Lyu, W.Y., et al. Progress in Brittleness Evaluation and Prediction Methods in Unconventional Reservoirs. Petroleum Science Bulletin 2021, 6, 31–45, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L. , Wang, J., Gao, S., et al. Characterization, Controlling Factors and Evolution of Fracture Effectiveness in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Journal of Petro⁃ leum Science and Engineering 2021, 203, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.H. , Xie, J. The Progress and Prospects of Shale Gas Exploration and Exploitation in Southern Sichuan Basin, NW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2018, 45, 161–169, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUO Tonglou, XIONG Liang, LEI Wei, et al. Deep Shale Gas Exploration and Development in the Weirong and Yongchuan Areas, South Sichuan Basin: Progress, Challenges and Prospec. Natural Gas Industry 2022, 42, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L. , Yao, J.Q., Gao, S., et al. Controls of Rock Mechanical Stratigraphy on Tectonic Fracture Spacing. Geotectonica et Metallogenia 2018, 42, 965–973, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.X. , Tang, J.M., Ouyang, J.S., et al. Characteristics of Structural Deformation in the Southern Sichuan Basin and Its Relationship with the Storage Condition of Shale Gas. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41, 11–19, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. , Xu, J.L., Wang, Y., et al., 2021. The Shale Gas Enrichment Factors of Longmaxi Formation under Gradient Basin- Mountain Boundary in South Sichuan Basin: Tectono- Depositional Differentiation and Discrepant Evolution.

- Ma, X.H. , Xie, J., Yong, R., et al. Geological Characteristics and High Production Control Factors of Shale Gas Reservoirs in Silurian Longmaxi Formation, Southern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2020, 47, 841–855, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).