1. Introduction

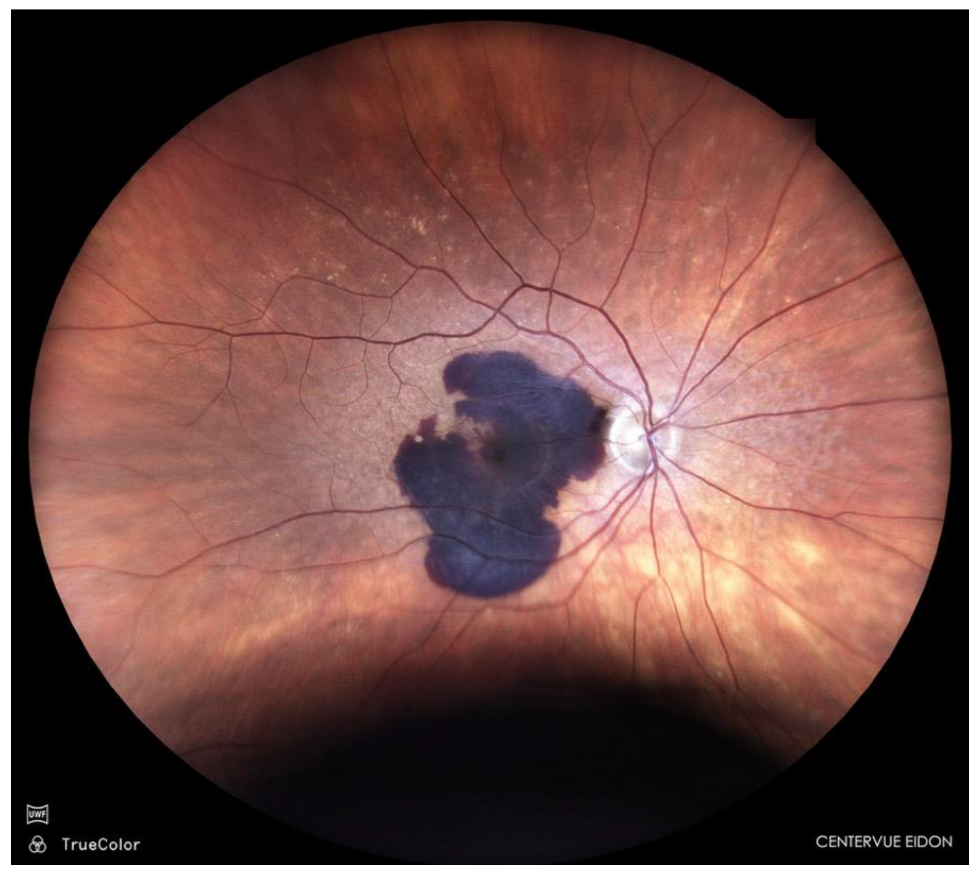

Sub-macular haemorrhage is a vision-threatening complication of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD); (

Figure 1), polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, and rupture of macular macro- or micro-aneurysms [

1,

2].

The accumulation of blood in the subretinal space exerts toxic and mechanical effects on the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium, often leading to irreversible vision loss if left untreated [

3,

4,

5]. The presence of iron, haemosiderin, and fibrin within the subretinal space triggers photoreceptor apoptosis within hours, emphasising the need for early displacement of the clot to restore the foveal architecture and prevent permanent macular damage [

6].

Current therapeutic options include enzymatic clot liquefaction with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase) with or without pneumatic displacement using expansile gas (e.g. sulphur hexafluoride [SF₆] or perfluoropropane [C₃F₈]), anti-VEGF therapy alone, and surgical interventions such as pars plana vitrectomy with subretinal injection of tPA. [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] While surgery can be effective, it carries higher risks and costs and may not be accessible in all clinical settings [

8,

9,

11].

A combined pharmacological and pneumatic approach allows both enzymatic degradation of the subretinal clot and mechanical displacement of blood from the foveal region. This strategy can be performed in an outpatient setting and offers a favourable balance between efficacy, safety, and accessibility—particularly for elderly patients who, owing to comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or diabetes, are often unfit for surgery [

12].

Aim

This article presents a case series illustrating the efficacy of a combined minimally invasive approach for sub-macular haemorrhage—intravitreal tPA with expansile gas (C₃F₈)—followed by adjuvant anti-VEGF therapy within a treat-and-extend (T&Ex) regimen. The aim is to evaluate the anatomical and functional outcomes achieved with this combined management strategy in patients with sub-macular haemorrhage secondary to nAMD over a six-month follow-up period.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants:

This retrospective case series included ten patients (10 eyes) treated in 2024 and 2025 at the Prof. Zagórski Eye Surgery Centre, Nowy Sącz, Poland. All patients presented with a diagnosis of sub-macular haemorrhage secondary to exudative AMD.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: a diagnosis of neovascular AMD with sub-macular haemorrhage confirmed by OCT and fundus imaging, and symptom onset within 60 days prior to treatment.

Exclusion criteria consisted of haemorrhage lasting longer than two months or the presence of scarring.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Treatment Protocol:

All patients underwent intravitreal injection of tPA (Alteplase, Actilyse® 100 µg/0.1 mL) combined with pure perfluoropropane gas (C₃F₈) 0.3 mL at 100% concentration, followed by anterior chamber paracentesis to prevent a rise in intraocular pressure (IOP). The procedure was performed under aseptic conditions in the operating theatre. After treatment, patients were instructed to maintain a prone position for at least three days to facilitate displacement of sub-macular blood.

Between 7 and 14 days after the initial tPA + gas injection, all patients began anti-VEGF therapy with either aflibercept 2.0 mg/0.1 mL (Eylea 2 mg, Bayer) or aflibercept 8 mg/0.1 mL (Eylea 8 mg, Bayer) using a treat-and-extend (T&Ex) regimen. The loading phase for both formulations consisted of three-monthly injections, followed by extension according to the T&Ex protocol.

Outcome Measures:

Patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation at baseline and at 7 days or 14 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months initial tPA and gas injection. Assessments included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) measured using an ETDRS chart, fundus photography, macular spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A) at each time point.

3. Results

Ten patients (ten eyes) with sub-macular haemorrhage secondary to neovascular AMD were included. The mean age was 76.0 ± 6.1 years (range: 60–90 years). Five patients

(50%

) were female and five

(50%

) male. All eyes presented with fovea-involving haemorrhage

. The mean duration from symptom onset to treatment was 25 ± 18 days (range: 7–60 days

). Table 1 summarises the demographic data, diagnosis, and symptom onset.

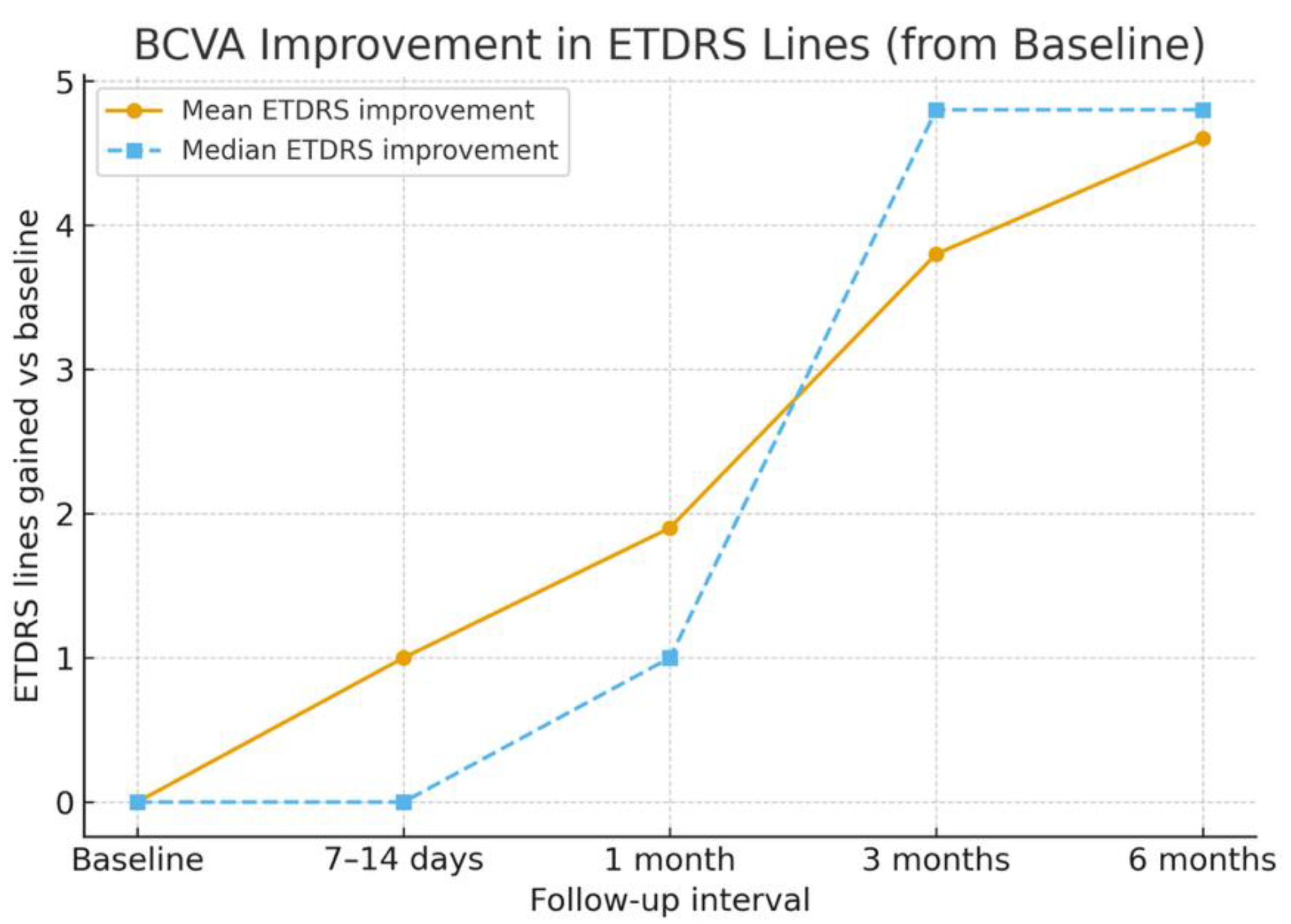

The mean baseline BCVA was 0.99 ± 0.21 logMAR (Snellen equivalent ≈ 20/180). By 7–14 days, the mean BCVA improved to 0.89 ± 0.20 logMAR (≈ 20/155), representing an early gain of approximately one ETDRS line. At 1 month, the mean BCVA improved further to 0.80 ± 0.20 logMAR (≈ 20/110), corresponding to an average gain of two ETDRS lines. At 3 months, the mean BCVA reached 0.60 ± 0.18 logMAR (≈ 20/80), and by 6 months, it improved to 0.53 ± 0.20 logMAR (≈ 20/70), with six eyes (60%) gaining four or more ETDRS lines and none lost vision. Mean and median ETDRS line gains are shown in

Figure 2, and BCVA changes over time are detailed in

Table 2.

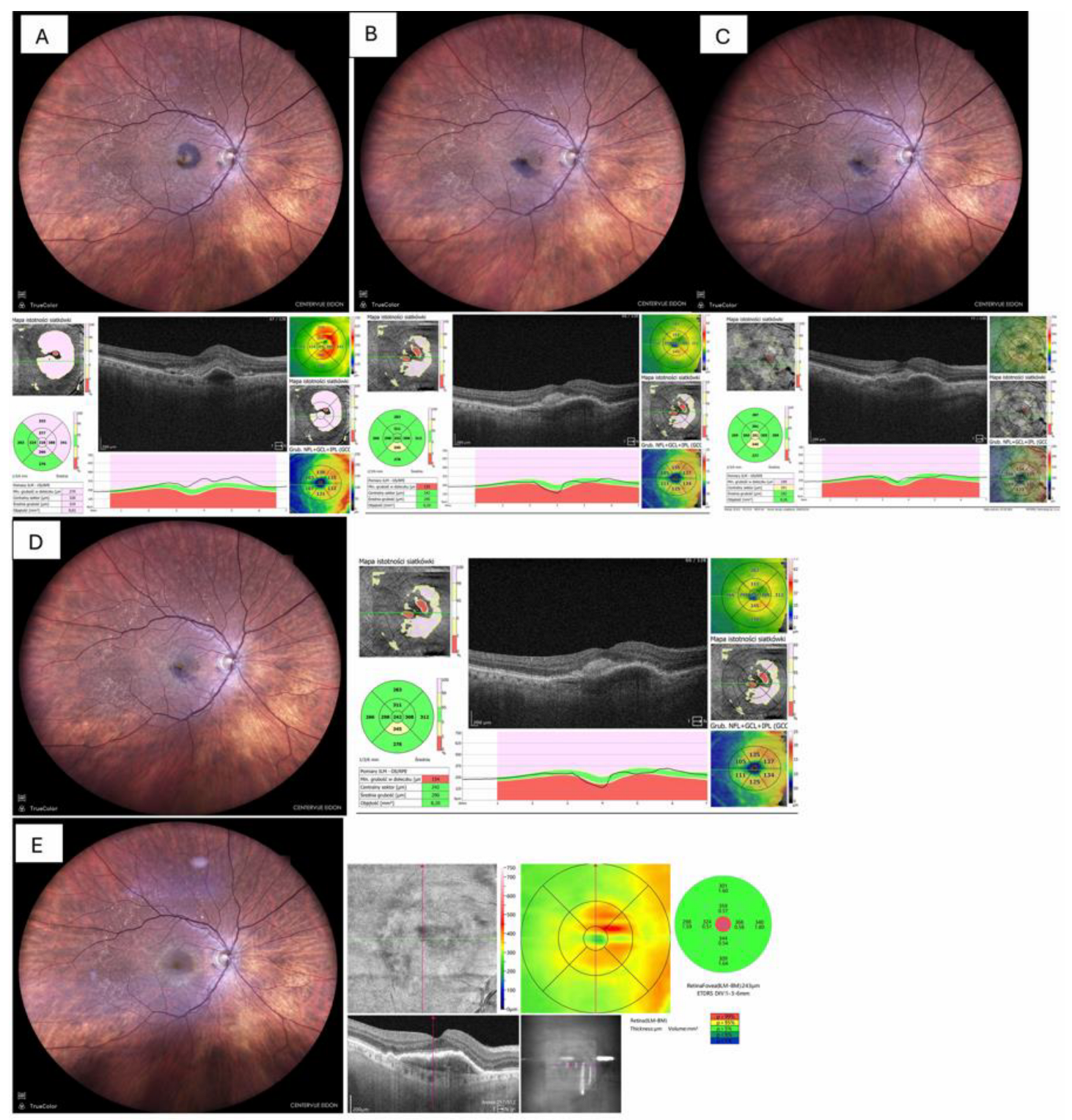

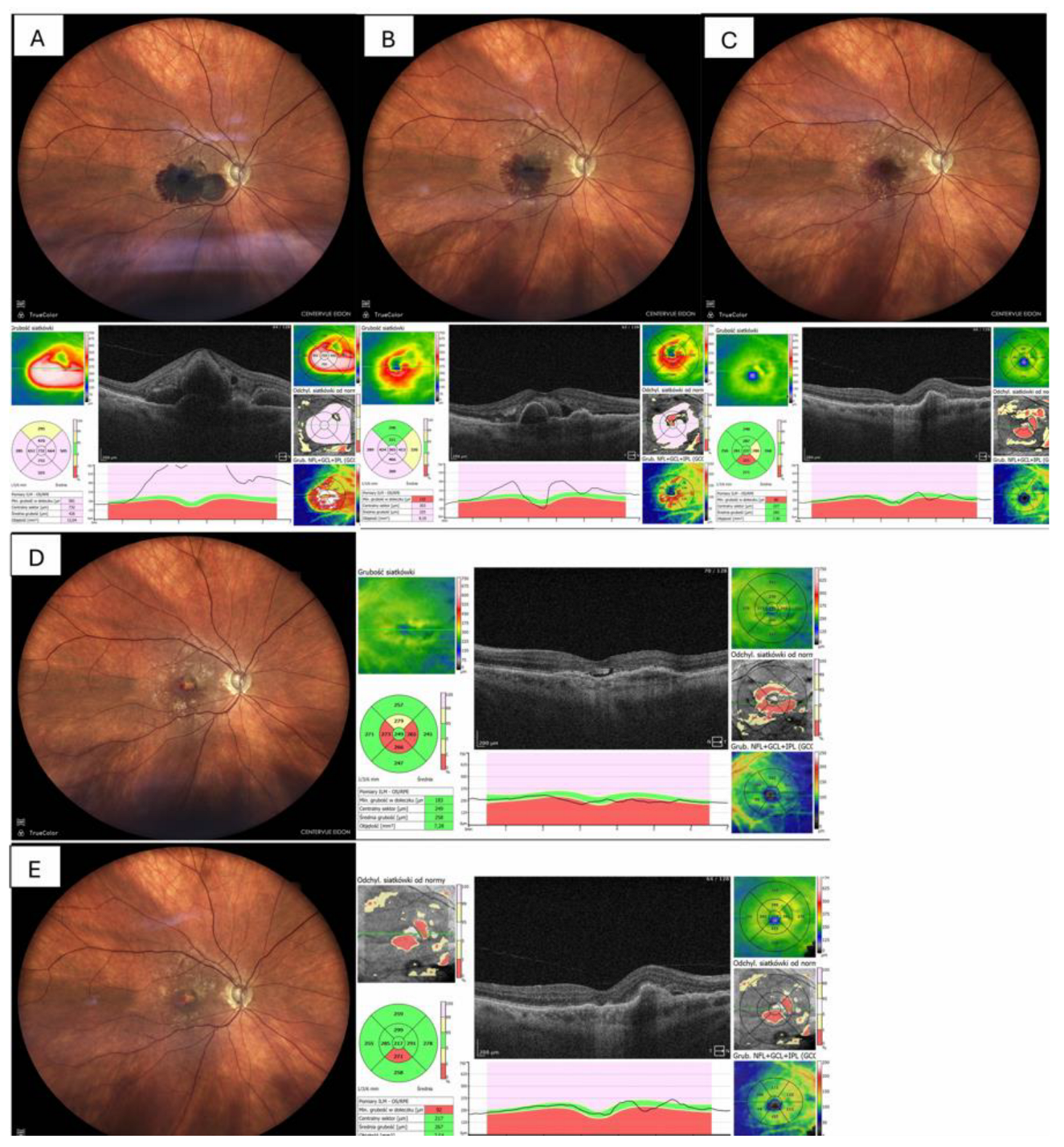

Fundus photography and OCT imaging confirmed near-complete displacement of the haemorrhage by day 30 and restoration of the foveal contour in eight eyes (80%) as depicted in

Figure 3, whereas two eyes (20%) showed residual ellipsoid-zone disruption and subsequent fibrotic scarring and atrophy, which is shown in

Figure 4.

Safety Outcomes:

One patient experienced a transient IOP rise (≥30 mmHg), which resolved following anterior-chamber paracentesis. Two patients developed cataract progression (non–vision-threatening), and two showed macular neovascularisation scarring.

No cases of endophthalmitis, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tear, retinal detachment, or recurrent haemorrhage occurred during the six-month follow-up.

Table 3 summarises the safety outcomes and complications.

4. Discussion

Sub-macular haemorrhage (SMH) in the context of neovascular AMD remains a pressing therapeutic challenge. Prompt, effective treatment is critical, as blood accumulation damages photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium through mechanical separation, iron toxicity, and clot-related stress [

4,

5]. Early intervention is therefore vital to preserve macular integrity.

A 2024 meta-analysis revealed that combining tPA and anti-VEGF resulted in significant visual acuity improvement (−0.38 logMAR at 1 month, −0.47 logMAR at longer follow-up) with an 86% success rate in haemorrhage displacement [

9]. Similarly, combining low-dose subretinal tPA with intravitreal anti-VEGF during vitrectomy produced favourable six-month outcomes, although retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) degeneration in some patients highlights the need for individualised treatment planning [

3,

10,

13].

Notably, a recent randomised trial indicated that surgical management of SMH—vitrectomy with subretinal tPA and intravitreal gas—did not significantly outperform pneumatic displacement in improving visual outcomes. The ongoing TIGER trial is expected to provide clarity on surgical versus non-surgical strategies in large, fovea-involving haemorrhages [

7,

14]. Announced in 2020 and updated in 2025, this trial is still ongoing, with no results published yet [

14,

15].

Imaging evidence suggests that retinal damage depends more on the duration of haemorrhage than on the treatment technique, supporting the rationale fo

r early combined therapy [

11,

16]

. Although clinical practice varies—ranging from observation to monotherapy or combination therapy—our minimally invasive, simple yet effective protocol aligns well with the most evidence-supported approaches. Biologically, the basis for early treatment is compelling. Fibrin toxicity and photoreceptor separation were first demonstrated in animal models by Toth et al., while Lim et al. emphasised the risk of breakthrough haemorrhage and complications when triple therapy is delayed [

4,

13].

In summary, our findings complement the growing body of evidence supporting early, combined, minimally invasive pharmacological–pneumatic therapy for SMH secondary to AMD [

9]. Going forward, randomised studies, extended follow-up, and image-guided treatment individualisation are needed to optimise outcomes.

Compared with classical surgical approaches (vitrectomy with sub-macular tPA), this method is less invasive, repeatable, and can be performed in an outpatient or office setting. Early initiation of treatment (preferably within 30 days) appears to be a critical factor in achieving favourable visual and anatomical results [

3,

10].

The main limitations of this study include its small sample size and retrospective, non-randomised design. Further prospective, randomised controlled trials are required to confirm our findings and to refine treatment timing and dosage protocols [

15].

Conclusion

A combined treatment approach using a single intravitreal injection of alteplase with pure C₃F₈ gas, followed by anti-VEGF therapy within a treat-and-extend (T&Ex) regimen, can achieve significant visual and anatomical improvement in patients with sub-macular haemorrhage secondary to AMD. Early intervention remains crucial, and this minimally invasive protocol may serve as a safe and effective alternative to more complex surgical procedures.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Tsuiki E, Kusano M, Kitaoka T: Complication associated with intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of submacular hemorrhage due to rupture of retinal arterial macroaneurysm. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019, 16:. 10.1016/j.ajoc.2019. 1005.

- Mohammed TK, Simon CL, Gorman EF, Taubenslag KJ: Management of Submacular Hemorrhage. Curr Surg Rep. 2022, 10:. 10. 1007.

- Iannetta D, De Maria M, Bolletta E, Mastrofilippo V, Moramarco A, Fontana L: Subretinal injection of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and gas tamponade to displace acute submacular haemorrhages secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2021, 15:. 10.2147/OPTH. 3240.

- Toth CA, Morse LS, Hjelmeland LM, Landers MB: Fibrin Directs Early Retinal Damage After Experimental Subretinal Hemorrhage. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1991, 109:. 10.1001/archopht.1991. 0108.

- Daniel E, Toth CA, Grunwald JE, et al.: Risk of scar in the comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2014, 121:. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.

- Stanescu-Segall D, Balta F, Jackson TL: Submacular hemorrhage in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A synthesis of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016, 61:. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.04.

- Jackson TL, Bunce C, Desai R, et al.: Vitrectomy, subretinal Tissue plasminogen activator and Intravitreal Gas for submacular haemorrhage secondary to Exudative Age-Related macular degeneration (TIGER): study protocol for a phase 3, pan-European, two-group, non-commercial, active-control, observer-masked, superiority, randomised controlled surgical trial. Trials. 2022, 23:99. 10. 1186.

- Iannetta D, De Maria M, Bolletta E, Mastrofilippo V, Moramarco A, Fontana L: Subretinal Injection of Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Gas Tamponade to Displace Acute Submacular Haemorrhages Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2021, Volume 15:3649–59. 10.2147/OPTH. 3240.

- Veritti D, Sarao V, Martinuzzi D, Menzio S, Lanzetta P: Submacular Hemorrhage during Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression on the Use of tPA and Anti-VEGFs. Ophthalmologica. 2024, 247:191–202. 10. 1159.

- Wolfrum P, Böhm EW, König S, Lorenz K, Stoffelns B, Korb CA: Safety and Long-Term Efficacy of Intravitreal rtPA, Bevacizumab and SF6 Injection in Patients with Submacular Hemorrhage Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J Clin Med. 2025, 14:. 10. 3390.

- Szeto SKH, Tsang CW, Mohamed S, et al.: Displacement of Submacular Hemorrhage Using Subretinal Cocktail Injection versus Pneumatic Displacement: A Real-World Comparative Study. Ophthalmologica. 2024, 247:118–31. 10. 1159.

- De Silva SR, Bindra MS: Early treatment of acute submacular haemorrhage secondary to wet AMD using intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator, C 3F8, and an anti-VEGF agent. Eye (Basingstoke). 2016, 30:. 10.1038/eye.2016.

- Lim JH, Han YS, Lee SJ, Nam KY: Risk factors for breakthrough vitreous hemorrhage after intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator and gas injection for submacular hemorrhage associated with age related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2020, 15:e0243201. 10.1371/journal.pone. 0243.

- NCT04663750: Vitrectomy, Subretinal Tissue Plasminogen Activator (TPA) and Intravitreal Gas for Submacular Haemorrhage Secondary to Exudative (Wet) Age-related Macular Degeneration (TIGER). https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04663750. 2020.

- Lee CN, Desai R, Ramazzotto L, et al.: Vitrectomy, subretinal Tissue plasminogen activator and Intravitreal Gas for submacular haemorrhage secondary to Exudative Age-Related macular degeneration (TIGER): update to study protocol and addition of a statistical analysis plan and health economic analysis plan for a randomised controlled surgical trial. Trials. 2025, 26:. 10. 1186.

- Bae K, Cho GE, Yoon JM, Kang SW: Optical coherence tomographic features and prognosis of pneumatic displacement for submacular hemorrhage. PLoS One. 2016, 11:. 10.1371/journal.pone. 0168.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).