1. Introduction

The internet of things (IoT) has gained enormous interest in both scientific and industrial communities, with applications ranging from smart cities to agriculture [

1,

2,

3]. In such systems, wireless communication is a key feature, and technologies such as Wireless Fidelity (Wi-Fi), Bluetooth, and Zigbee protocol (Zigbee) are widely employed [

4]. Most deployments rely on numerous embedded systems integrating Microcontroller Unit (MCU)s and sensors, which are typically low-power and often run bare-metal firmware to minimize energy consumption. While manual firmware updates are possible, they require user assistance and do not scale to large deployments [

5,

6,

7]. To overcome these limitations, over-the-air (OTA) update protocols have been developed as a practical and scalable solution.

In industrial settings, where thousands of devices may already be deployed, OTA strategies must deliver new configurations and firmware efficiently while minimizing disruption [

5]. OTA updates are also well established in complex systems such as vehicles, where security enhancements have been introduced through decentralized identifiers and distributed ledger technology [

8]. More recently, Park et al. [

9] proposed a secure and lightweight firmware OTA mechanism for constrained IoT devices, combining encryption, compression, and multichannel transmission to reduce latency, memory, and energy use while resisting man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. These examples demonstrate that OTA solutions must address both performance and security challenges.

In remote deployments, stable short-range connections are often unavailable. Technologies such as Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) and Narrowband Internet of Things (NB-IoT) provide long-range connectivity but are limited by energy consumption, making Long Range (LoRa) a preferred option for low-power devices. Malumbres et al. [

10] proposed a hybrid broadcast–unicast strategy to accelerate LoRa OTA in industrial scenarios, while Neves et al. [

11] presented a runtime update method for LoRaWAN Class A devices that reduces downtime to milliseconds and minimizes transmitted data by over 99%. For NB-IoT, Mahfoudhi et al. [

12] demonstrated a proof-of-concept OTA framework showing that large updates can be delivered with less than 0.75% battery overhead. Together, these works highlight how OTA can be optimized for both long-range reliability and energy efficiency.

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) represent another important domain of the IoT, with applications ranging from environmental monitoring to smart metering. Ševčík et al. [

13] demonstrated a WSN for smart power metering, emphasizing the need for reliable OTA updates to ensure long-term stability. Energy efficiency is equally critical, since WSN nodes are battery-powered or harvest energy. Hodoň et al. [

14] proposed an event-driven framework (Entity Dust Container (EDC)) to minimize operational costs, while Kochlan et al. [

15] evaluated an Open Voltage Maximum Power Point Tracking

(MPPT) algorithm for power management. Complementary approaches were presented by Rehman et al. [

16], who balanced energy and security overhead, and Ullah et al. [

17], who applied hybrid clustering and routing to extend lifetime. These studies reinforce that OTA update systems must integrate energy-aware and security-aware design principles for sustainability in large-scale deployments.

Finally, OTA can be implemented using three typical architectures [

5][

18]:

Edge-to-cloud OTA updates: the microcontroller on the edge device is connected to the internet and directly receives the new firmware binary from the cloud. In this type of architecture, the cloud acts as a dispatcher, delivering the correct firmware version to each IoT device that requires an upgrade.

Gateway-to-cloud OTA updates: a set of local edge devices are connected to an internet-connected gateway that manages these devices. The gateway receives updates from the cloud, allowing not only the distribution of device firmware but also the updating of gateway firmware and host applications.

Edge-to-gateway-to-cloud OTA updates: the gateway downloads the firmware from the cloud and subsequently transmits it to the local edge devices, combining aspects of the first two architectures.

Several OTA frameworks have been proposed in recent years, including Zigbee2MQTT, which enables firmware distribution through Zigbee mesh networks within the Home Assistant ecosystem, as well as commercial platforms such as Mender.io and BalenaCloud that provide containerized OTA management for Linux-based systems. While these solutions offer valuable insights, they remain limited to either specific communication protocols or high-level operating systems, making them unsuitable for resource-constrained microcontrollers like the ESP32. Espressif’s native OTA library, for instance, supports only Wi-Fi-based updates without multi-protocol or version-aware coordination. Other studies have explored LoRa and NB-IoT-based OTA schemes with enhanced energy efficiency [

10,

12], and blockchain-assisted OTA frameworks for secure automotive systems [

8]. Despite these advancements, there remains a lack of unified, lightweight OTA architectures that integrate multiple transport layers and provide centralized version control for microcontroller-based IoT deployments.

The main novelty of this work lies in the design of a unified and automated OTA update architecture for ESP32-based IoT systems that supports multiple communication interfaces (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth

Low Energy (BLE), Zigbee, LoRa, and GSM) under a centralized versioning and routing framework. Unlike existing single-protocol OTA implementations, the proposed system employs a server-driven architecture that dynamically manages firmware distribution, enabling both production and development branches, compatibility checks, and seamless CI/CD integration for continuous firmware delivery. This approach enhances scalability, maintainability, and security across heterogeneous IoT networks, representing a practical contribution toward reliable multi-protocol OTA management for embedded systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the OTA process and its implementation for ESP32-based systems. Section 3 presents the architecture of the updating service, including version management and routing logic. Section 4 discusses the extended OTA models for BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, and GSM. Section 5 provides the analytical model of the OTA process, while Section 6 reports the system testing results. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Over the Air Update

OTA update is a mechanism for remotely deploying and installing firmware updates on connected devices, eliminating the need for physical access. This approach is essential for maintaining, enhancing, and securing IoT devices deployed in various environments, often challenging to reach. This paper presents an overview of the OTA updating process, with a particular focus on the implementation for Espressif microcontrollers [

19].

The OTA update process involves several key steps. First, a new version of the firmware must be prepared by the manufacturer or developer. This firmware may include feature enhancements, bug fixes, or security patches. The new firmware is then uploaded to an update server, which can be configured to be accessible via various communication protocols such as HyperText Transfer Protocol

(HTTP), HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS), or File Transfer Protocol (FTP) [

20,

21,

22].

Connected devices periodically check for the availability of updates by querying the server. This check can be scheduled at regular intervals or triggered by specific events. When an update is detected, the device downloads the firmware from the server. To ensure the firmware’s integrity, the device performs validation checks using hash functions or digital signatures [

19].

Following successful validation, the firmware is installed into the device’s flash memory. This process must be carefully managed to prevent data corruption. After installation, the device restarts to activate the new firmware, and post-installation tests are conducted to verify that the update has been applied correctly and that the new firmware operates as expected.

The partition table is a data structure that defines how the Espressif 32-bit System on Chip

(ESP32)’s flash memory is divided into partitions, each serving a specific purpose, such as storing the bootloader, application code, OTA data, or other essential information. Typically located at the beginning of the flash memory, the partition table acts as a map for the device’s memory layout, playing a crucial role during the boot process and in memory allocation throughout the device’s operation. Common partition types include the bootloader, application partitions, OTA data, Non-Volatile Storage

(NVS), and file system partitions.

Different types of partition tables are supported by the ESP32, including the Single App Partition Table, which is simple with a single application partition and no OTA support, the OTA Partition Table that allows for multiple application partitions to support OTA updates, and Custom Partition Tables, where developers can define specific configurations to meet unique application needs. The bootloader reads the partition table during the boot process, determining which partitions to use for booting and running applications. During OTA updates, new firmware is written to an inactive application partition, with the OTA data partition updated to point to the new firmware after successful verification. This setup allows the device to switch between firmware versions safely, providing a fallback mechanism in case of update failures [

19].

For Espressif devices, such as the ESP32, the OTA update process is facilitated through the Espressif library, which provides specific Application Programming Interface (API)s for managing OTA updates. For example, on the ESP32, the HTTPUpdate API allows for OTA updates via HTTP/HTTPS, streamlining the update process. The library also supports other communication protocols, including BLE and Zigbee, although Wi-Fi remains the most common due to its speed and ease of use. Additionally, the Espressif library includes functionality for managing rollbacks, allowing the device to revert to a previously valid firmware image if the new update is found to be defective. This rollback feature ensures that the device remains operational even if an OTA update fails, enhancing the reliability of the update process [

19][

23].

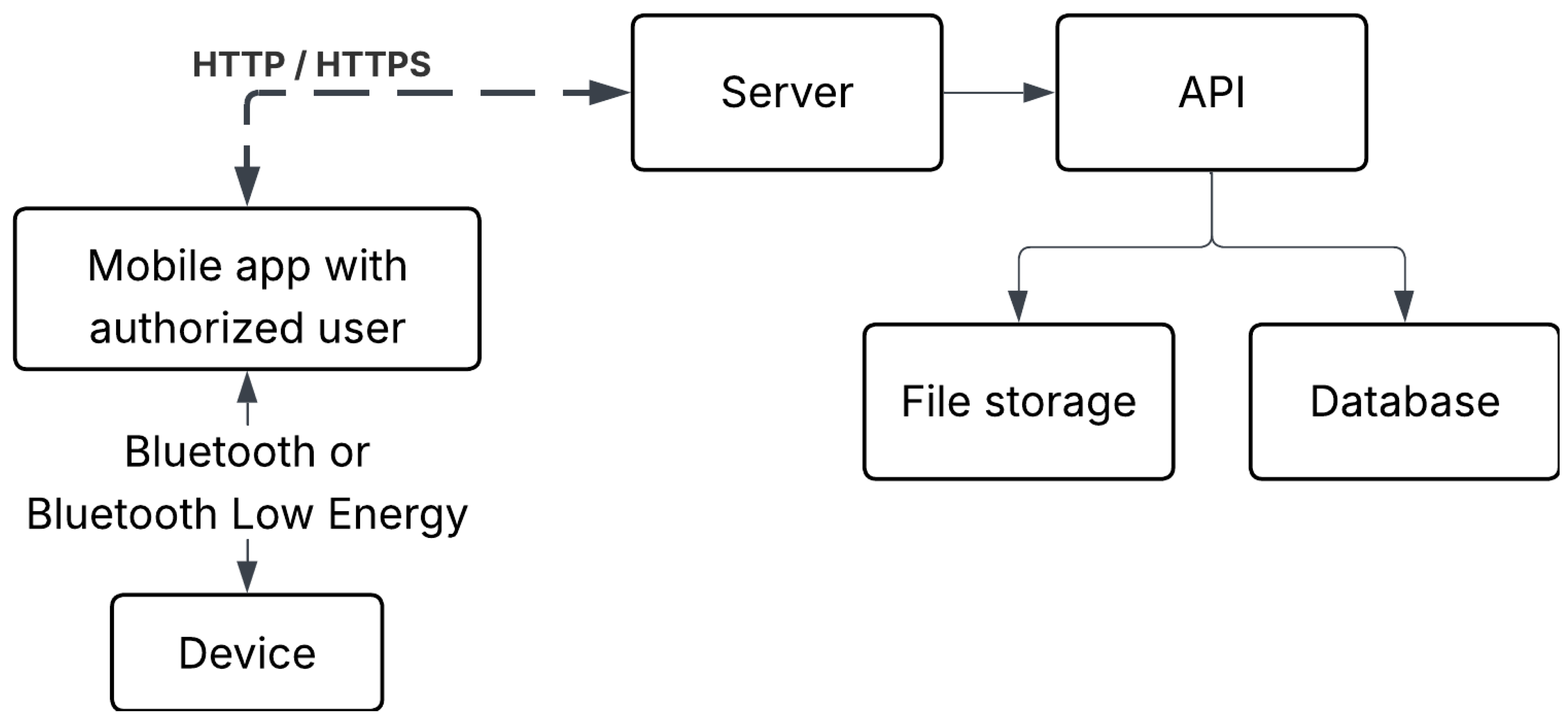

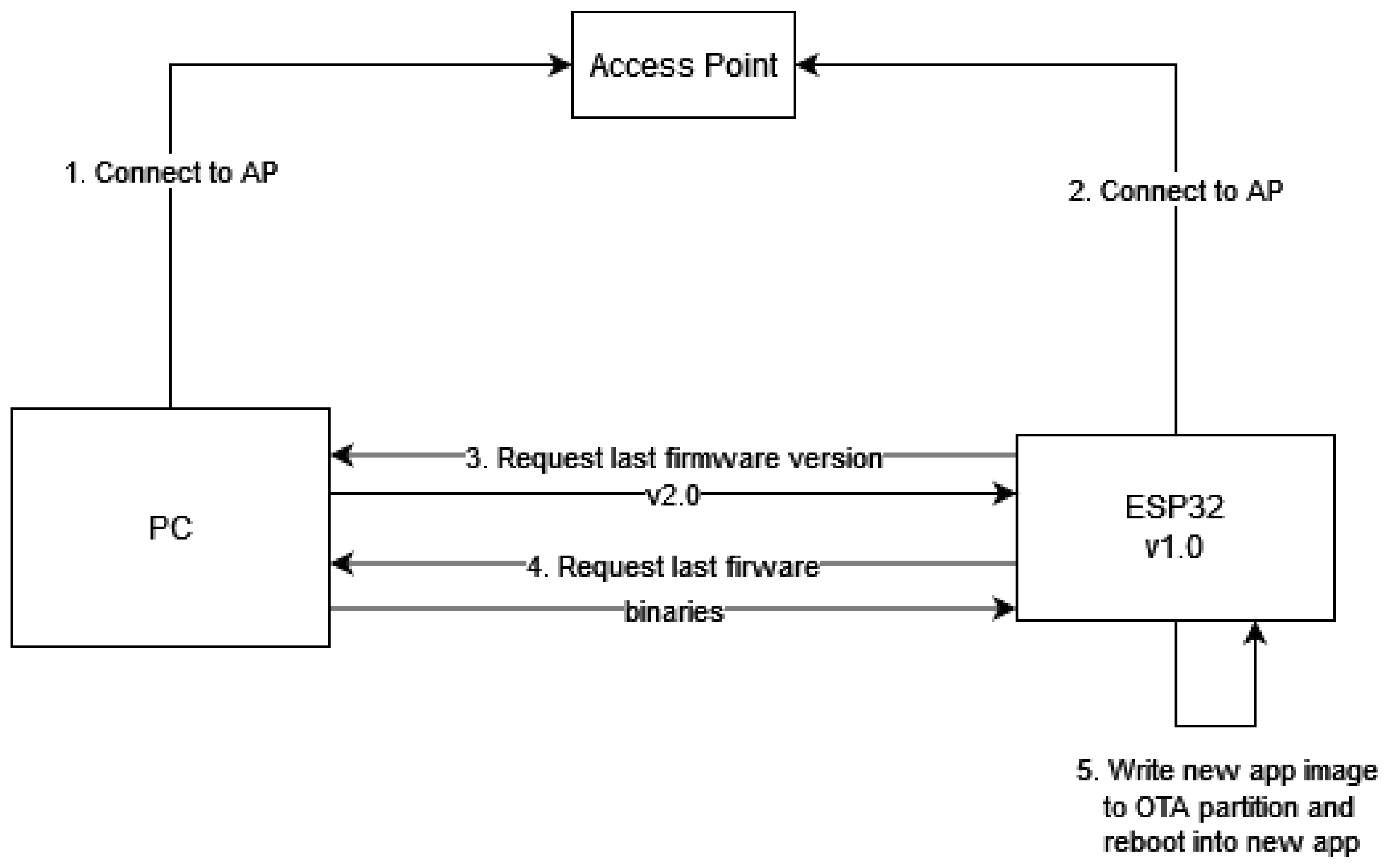

2.1. OTA Update via Wi-Fi

The updated firmware is uploaded to a server accessible via Wi-Fi, which handles HTTP or HTTPS requests, making it straightforward for devices to fetch the firmware [

24].

Devices equipped with Wi-Fi connectivity periodically connect to the update server to check for new firmware availability. This connection allows them to check for the availability of new firmware. The frequency of these checks can be set based on the device’s requirements or operational schedule. When a device detects that a new firmware version is available, it sends a request to the server to download the update. This request typically involves querying the server for the latest version of the firmware and obtaining the firmware file [

20].

The device downloads the firmware file from the server over the Wi-Fi connection. Given the high-speed capabilities of Wi-Fi, this process is generally rapid, allowing for quick transfers even for large firmware files. After downloading the firmware, the device performs a verification process to ensure that the firmware is intact and has not been corrupted. Once verified, the firmware is installed into the device’s flash memory.

After the installation is complete, the device reboots to apply the new firmware. This step activates the updated software. Following the reboot, the device may perform additional checks to confirm that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new software.

Wi-Fi provides a high-speed connection, making it efficient for transferring large firmware files quickly. This rapid update process minimizes downtime and ensures that devices are swiftly updated with the latest firmware. Implementing OTA updates via Wi-Fi is relatively straightforward. Wi-Fi is a common communication protocol, and many devices are already equipped with Wi-Fi capabilities. Wi-Fi is one of the most commonly used methods for OTA updates due to its widespread availability and the high-speed data transfer it supports. It is well-suited for scenarios where devices are connected to a stable and robust network infrastructure.

One drawback of using Wi-Fi for OTA updates is its relatively high power consumption. Wi-Fi connectivity can be energy-intensive, which may be a concern for battery-operated devices. The power requirements for maintaining a Wi-Fi connection and transferring data can impact the device’s battery life. Devices equipped with Wi-Fi typically query the update server at regular intervals to check for new firmware updates. This polling mechanism ensures that devices stay current with the latest software, although it may involve some overhead in terms of network traffic and server load.

Design and diagram of updating is consequently shown on

Figure 1.

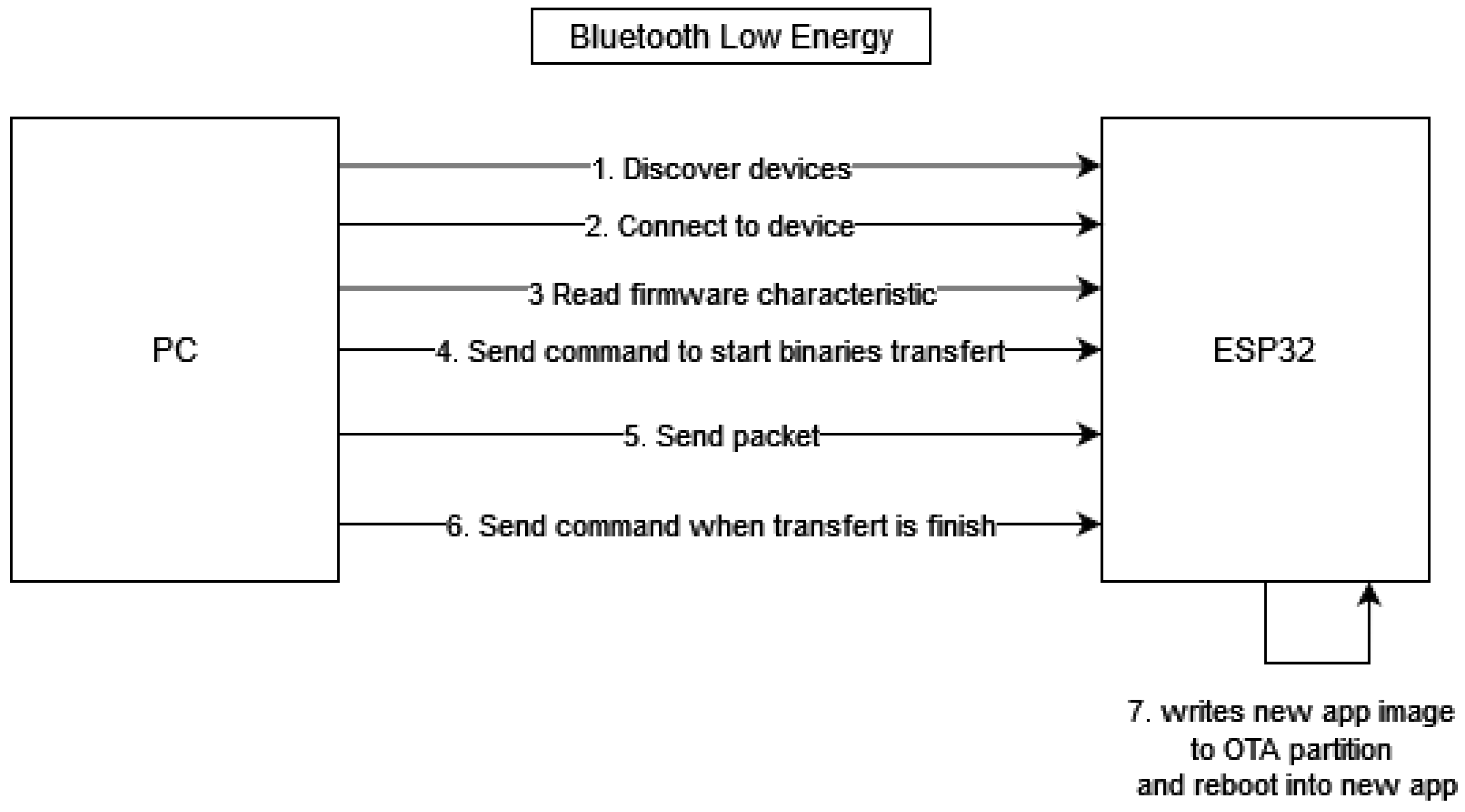

2.2. OTA Update via Bluetooth Low Energy

The new firmware is uploaded to a central server that will be accessed by the client (typically a smartphone or a gateway) to initiate the update process [

20].

The BLE client searches for nearby devices that need a firmware update. Once the target devices are discovered, the client initiates a connection to each device. In this setup, the client acts as the central server, and the devices (which need the update) act as peripheral servers. Upon establishing a connection, the client sends a request to the device to start the update process. The client then begins to transfer the firmware to the device in small packets. BLE is designed to be energy-efficient, which means that even though the transfer speed is slower compared to Wi-Fi, it consumes significantly less power, making it suitable for battery-operated devices[

25].

As the device receives the firmware packets, it performs checks to ensure the integrity and completeness of the data. This is typically done using hash functions or digital signatures to verify that the firmware has not been corrupted during the transfer. Once the device has received the entire firmware and verified its integrity, it proceeds to install the firmware into its flash memory. After installing the firmware, the device reboots to activate the new software. Post-reboot, the device performs additional checks to ensure that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new firmware [

25].

BLE provides a relatively quick transfer rate for small to medium-sized firmware files, making the update process efficient. While it is not as fast as Wi-Fi, the speed is sufficient for most IoT applications. One of the primary advantages of BLE is its low power consumption. BLE is specifically designed to be energy-efficient, which makes it ideal for devices that rely on battery power. As a Bluetooth technology, BLE benefits from widespread compatibility and support across many devices, including smartphones and gateways. This broad compatibility makes it a versatile option for OTA updates. In the BLE OTA update process, the client (the central server) manages the update process by communicating with the servers (the devices). This client-server model ensures that the update process is controlled and systematic [

25]. Full diagram is shown on

Figure 2.

2.3. OTA Update over Zigbee

The firmware is compiled into an image suitable for distribution. Unlike other methods, Zigbee requires a Zigbee coordinator or server device that manages the update process. This server can be an IoT gateway or a specific device within the Zigbee network, where the new firmware image is uploaded[

26].

The Zigbee server identifies and connects to target devices within the Zigbee mesh network that require the firmware update. Zigbee’s mesh network topology allows for robust communication pathways. The server begins transferring the firmware to the target devices. This transfer is extremely slow compared to Wi-Fi or BLE due to Zigbee’s lower data transfer rates. However, the process is highly energy-efficient, ideal for devices running on limited power sources such as batteries[

26].

As with other OTA methods, the receiving device performs integrity checks on the incoming firmware packets to ensure data integrity. Once the firmware is fully received and verified, it is installed into the device’s flash memory. After installing the firmware, the device reboots to activate the new software. Post-reboot, the device performs additional checks to confirm that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new firmware.

Zigbee’s data transfer rate is significantly slower than Wi-Fi and BLE, making the firmware update process much longer. This can be a limiting factor for large firmware updates but is manageable for smaller updates or infrequent updates. The low power consumption during the OTA update process helps extend the battery life of these devices. Zigbee operates over radio frequencies, providing reliable wireless communication within its network. The mesh network topology enhances connectivity and range by allowing data to hop between multiple devices[

26].

In a Zigbee network, the server responsible for OTA updates is typically installed on a dedicated device, such as a Zigbee coordinator or gateway. This device manages the update process and distributes the firmware to target devices. The new firmware image must be built and uploaded to the Zigbee server, which then manages the distribution and installation of the firmware to the devices within the network. It is possible to configure a Zigbee server on a PC using appropriate Zigbee dongles and software. This setup can provide a flexible and powerful solution for managing OTA updates within a Zigbee network[

26].

Figure 3.

OTA update process over Zigbee [

18]

Figure 3.

OTA update process over Zigbee [

18]

3. Updating Service Architecture

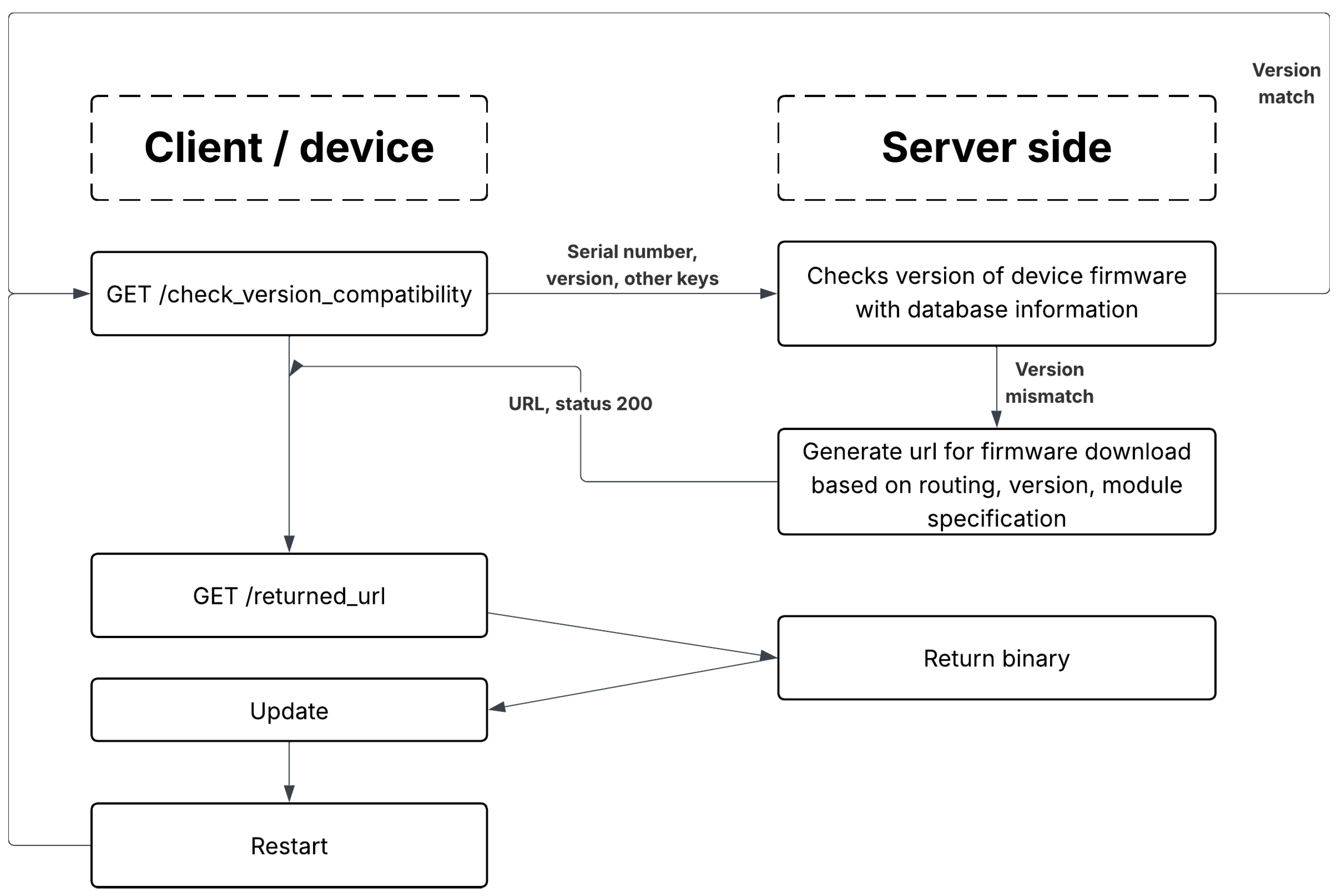

The following section describes the process flow of the Over-the-Air (OTA) firmware update system. The interaction occurs between a client device and a server-side application. Two main paths are possible: a

version match, where no update is required, and a

version mismatch, where a firmware update must be applied. An example database schema is shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, and the overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.1. Version Match Path

The client sends a GET HTTP request to the endpoint /check_version_compatibility, containing its serial number, firmware version, and any required identification or authentication keys. The server compares the provided firmware version with the one stored in the database. If the versions match, the server responds with status code 201. In this case, no update is required, and the process terminates.

3.2. Version Mismatch Path

The client again sends a GET request to /check_version_compatibility using the same parameters. The server compares the firmware version reported by the device with the current version stored in the database. If a mismatch is detected, the server generates a firmware download URL based on the routing information, target firmware version, and module specification. It responds with status code 200 and includes the generated download link, for example: /module_type/routing/version/firmware.bin.

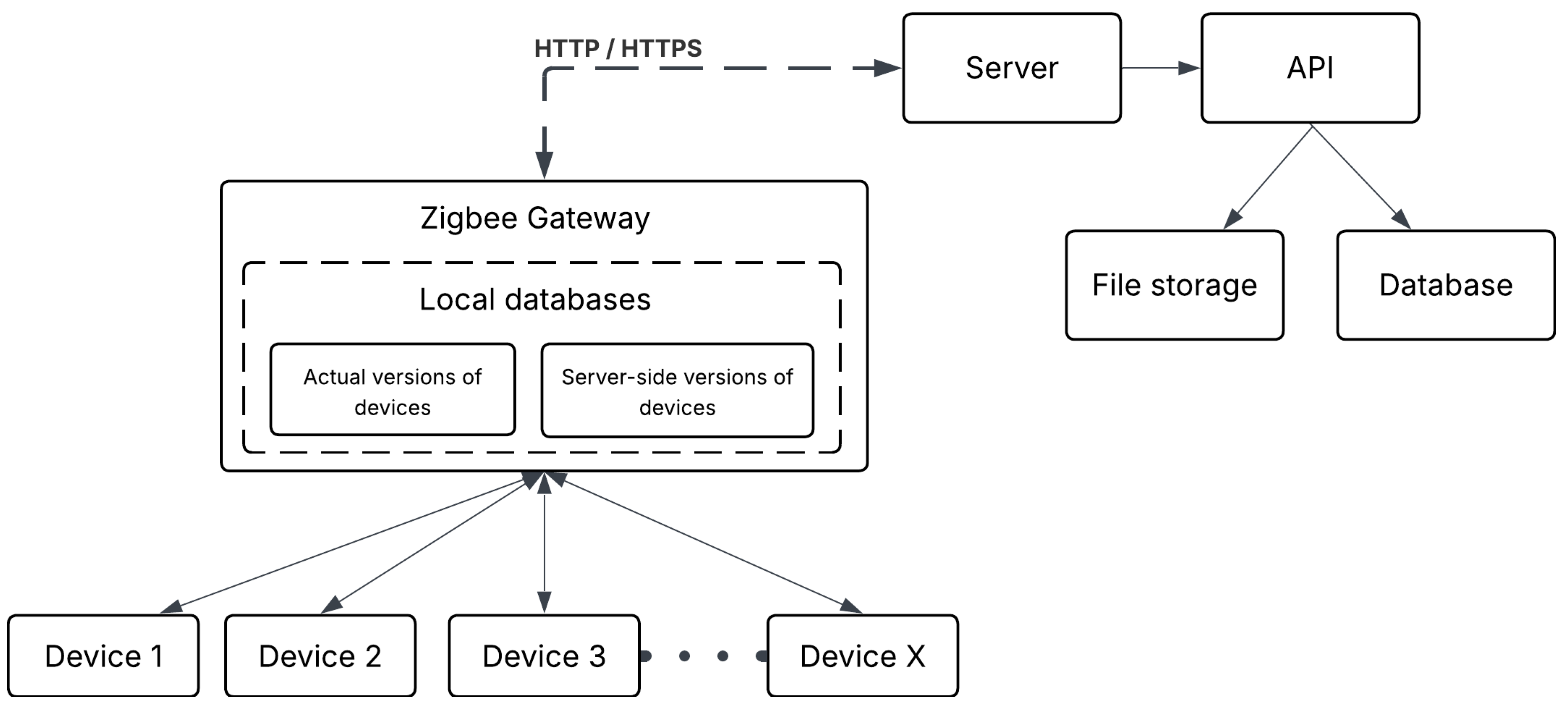

Figure 5.

Workflow of the OTA update process over BLE using a mobile application as an intermediary between the update server and the target device.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the OTA update process over BLE using a mobile application as an intermediary between the update server and the target device.

3.3. Update Download and Installation

The client then sends a request to the returned firmware URL (/returned_url). The server responds by providing the binary firmware file. The device downloads the firmware, verifies its integrity, installs the new version, and restarts to complete the update process.

4. Extended OTA Architectures: BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, GSM

While the baseline OTA system provides a reliable update mechanism over Wi-Fi, more complex network environments require specialized architectures. In particular, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and Zigbee introduce specific constraints and opportunities that influence the update process. Both approaches are designed with attention to energy efficiency and robustness but require different infrastructure components and dataflow optimization strategies.

4.1. OTA Updates over BLE with Mobile Application Support

For BLE-based updates, the update process involves a mobile application acting as an intermediary between the update server and the end device. The workflow is as follows:

- (1)

The mobile application automatically queries the server with the device’s current firmware version.

- (2)

If a version mismatch is detected, the mobile application downloads the appropriate firmware image into a temporary repository on the mobile device.

- (3)

The firmware is then transferred via BLE to the target device in small, reliable packets, ensuring integrity through checksum verification.

- (4)

Upon successful installation and restart of the device, the temporary firmware file is removed from the mobile repository to save storage and prevent redundancy.

This architecture leverages the widespread availability of smartphones while compensating for BLE’s limited bandwidth. By preloading the firmware into the mobile application before transfer, interruptions in connectivity are minimized and the overall dataflow remains efficient. Dataflow optimization is achieved through packet segmentation, error correction at the BLE layer, and by limiting redundant transfers across multiple devices.

Figure 6.

Gateway-coordinated OTA update process over Zigbee, illustrating version management, metadata synchronization, and incremental firmware distribution.

Figure 6.

Gateway-coordinated OTA update process over Zigbee, illustrating version management, metadata synchronization, and incremental firmware distribution.

4.2. OTA Updates over Zigbee with Gateway Coordination

For Zigbee-based networks, a gateway device plays a central role in managing OTA updates. The gateway maintains a temporary database containing the firmware versions of all connected devices, along with the latest versions available on the server. The update process proceeds as follows:

- (1)

The gateway periodically synchronizes with the server to fetch metadata about available firmware versions.

- (2)

It compares stored device versions against server versions to detect mismatches.

- (3)

When mismatches are found, the gateway distributes updates incrementally, handling one firmware version at a time across the connected Zigbee devices.

- (4)

After each successful device update, the temporary version database is updated to ensure consistency and traceability.

Due to Zigbee’s limited bandwidth, dataflow optimization is critical. This can be achieved through:

Incremental firmware distribution (version by version rather than all at once),

Local caching of firmware binaries at the gateway to avoid repeated server downloads, and

Scheduling updates to minimize network congestion in dense Zigbee meshes.

4.3. Dataflow Optimization Considerations

In both BLE and Zigbee OTA workflows, efficient dataflow management is essential to ensure stability and minimize update latency. BLE optimization focuses on reducing redundant mobile–server transfers, while Zigbee optimization relies on caching, incremental updates, and congestion-aware scheduling. Together, these approaches extend the robustness of OTA updates beyond Wi-Fi, making the system adaptable to a wide variety of IoT environments.

In addition to Wi-Fi, BLE, and Zigbee, new technologies and programming paradigms are expanding the possibilities for OTA updates on embedded devices. Among these, the use of bare-metal Rust for ESP32 development, as well as long-range communication technologies such as LoRa and GSM, represents a promising direction.

The integration of Rust, LoRa, and GSM into OTA workflows demonstrates the adaptability of modern update systems. Bare-metal Rust on ESP32 provides software-level safety and maintainability, while LoRa and GSM extend the reach of OTA updates to remote and mobile devices. Each technology requires tailored dataflow optimizations to account for bandwidth, latency, or cost constraints. Together, these approaches highlight the flexibility and scalability of OTA updates across diverse IoT deployment scenarios.

4.4. OTA Updates over LoRa

LoRa is well-suited for IoT applications requiring long-range communication with low power consumption, but it introduces severe bandwidth constraints. Full OTA updates over LoRa must therefore be optimized for efficiency. The update workflow typically includes:

- (1)

Fragmentation: Firmware images are split into small packets compatible with LoRa payload sizes (e.g., 51–222 bytes),

- (2)

Broadcast and unicast combination: Broadcast reduces the number of redundant transmissions, while unicast ensures reliability for devices that missed packets, and

- (3)

Forward error correction: Optional redundancy bits are added to recover from packet loss without retransmission.

Due to the limited data rate of LoRa, delta updates (transmitting only differences between firmware versions) and compression are often employed. This allows devices deployed in remote areas to receive critical security patches and updates without exhausting their battery resources.

4.5. OTA Updates over GSM

GSM and cellular IoT technologies (e.g., Long Term Evolution for Machines (LTE-M), NB-IoT) offer higher bandwidth compared to LoRa, making them suitable for distributing larger firmware binaries. The OTA update process over GSM involves:

- (1)

The device establishes a mobile data connection to the update server.

- (2)

It checks for the latest firmware version and downloads the binary file directly.

- (3)

To minimize costs, updates can be scheduled during off-peak hours or configured for partial (delta) transfers.

The main challenges of OTA over GSM are data costs, energy consumption during cellular communication, and intermittent coverage in rural areas. Dataflow optimization strategies include caching firmware at local gateways, compressing binaries before transfer, and splitting updates into resumable chunks.

5. Analytical Model of OTA Update Process

To complement the empirical evaluation, a simplified analytical model of the OTA process was developed to quantify the main timing, reliability, and energy parameters. This model provides a theoretical framework for evaluating performance and scalability under various communication conditions.

5.1. Timing Model

The total update duration can be expressed as:

where each component represents the time required for version verification, binary transfer, flash writing, and system reboot, respectively.

The firmware download time is approximated by:

where

S is the firmware size (in bytes) and

B is the average useful throughput (in bytes/s). This expression assumes a steady-state transfer rate without retransmissions. In practical networks, retransmissions due to packet loss slightly increase

according to the expected retry rate

derived below.

5.2. Reliability Model

Transmission reliability is modeled as a Bernoulli process with independent packet losses. If

p denotes the packet loss probability and

m the total number of packets per update, then the probability of successfully completing an update without retransmission is:

The expected number of retransmissions can be approximated by:

As p increases, both the expected latency and the total energy cost of the update grow nonlinearly, which emphasizes the importance of reliable link-layer error correction.

5.3. Energy Consumption Model

The total energy cost of an update is estimated as:

where

and

denote the number of transmitted and received packets, and

represent the average energy per packet transmission and reception, respectively. The processing overhead

includes checksum verification, flash writing, and cryptographic signature validation.

Assuming

J and

J per packet with

the total energy consumption per OTA update is approximately:

This estimate aligns with experimental results measured in

Section 6, confirming that communication overhead dominates the total energy consumption.

In addition to communication and processing costs, cryptographic verification contributes a measurable but minor overhead. On the ESP32 microcontroller, computing a SHA-256 hash over a 1 MB firmware image requires approximately 25 ms and 2.4 mJ of energy, while Ed25519 signature verification takes about 4.8 ms and 3.5 mJ. These operations represent less than 1% of the total update duration and energy but are essential for ensuring firmware authenticity and for protecting against rollback, replay, and man-in-the-middle attacks. The adopted security model follows a Dolev–Yao adversary assumption, where the attacker can eavesdrop, inject, or modify packets within the network but cannot compromise private cryptographic keys.

5.4. Delta Updates and Fragmentation Efficiency

When

delta updates are employed, only the difference between firmware versions (

) is transmitted. The relative size reduction ratio is given by:

The total update time then becomes:

where

and

are the compression and decompression times. Forward Error Correction (FEC) introduces redundancy factor

, increasing transmission volume by

and reducing packet loss effects at the cost of additional processing time. The effective throughput under FEC protection is:

These relationships allow estimating the tradeoff between computational overhead and transmission efficiency, which is crucial for optimizing OTA performance in low-bandwidth networks such as LoRa or Zigbee.

5.5. Optimization Considerations

The optimal OTA configuration can be viewed as a constrained optimization problem:

where

a represents the selected communication architecture (

Wi-Fi, BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, GSM). This formulation enables the designer to balance latency and energy consumption when choosing the appropriate OTA mechanism for large-scale IoT deployments.

6. System Testing and Results

The proposed OTA update architecture was validated in a controlled test environment. Up to twenty devices were connected simultaneously to a public server to evaluate performance, stability, and version management capabilities. Each device periodically requested update information, retrieved firmware images when available, and applied updates automatically.

Two versioning tracks were maintained during the evaluation:

Development firmware: used for testing and rapid iteration. These builds were frequently updated and deployed only to selected devices.

Production firmware: intended for stable operation. These versions were rolled out to all devices once the development builds had been validated.

This separation between development and production versions ensured that experimental features could be verified without affecting the stability of devices running in production. Testing confirmed that the server was capable of handling simultaneous update checks and firmware distribution for multiple devices. The architecture maintained consistency in version control, correctly distinguishing between development and production firmware, and reliably serving the appropriate binary images. The overall stability of the system was validated by repeated update cycles across all connected devices without failures or data corruption.

The experimental validation included measurements of average update duration, power consumption, and disconnection rates. For twenty ESP32 devices connected simultaneously, the average update time was approximately 18 s per device over Wi-Fi and 65 s over BLE. The mean power draw during the update process was 0.83 W, corresponding to an average energy cost of 15.1 J per update. No data corruption or firmware installation failures were detected, and only a single transient disconnection (5%) was observed in BLE mode. These metrics confirm the robustness and energy efficiency of the proposed OTA framework under realistic operating conditions.

All tests were conducted under controlled conditions, with the devices located approximately 5 m from the Wi-Fi access point and Bluetooth gateway. The average packet loss rate during transmission was below 1.5%, and the network load remained under 20% throughout the tests. Each experiment was repeated ten times under identical conditions to ensure statistical reliability. The standard deviation of update duration did not exceed 4.2% for Wi-Fi and 6.8% for BLE connections, confirming stable update performance across sessions.

For comparison, Espressif’s native OTA library for the ESP32 platform achieves an average update duration of approximately 22 s over Wi-Fi and lacks multi-version coordination or routing logic. The proposed architecture reduced the update duration by roughly 15% while introducing centralized version control, dynamic routing, and automated branching. Compared to Zigbee2MQTT-based OTA mechanisms, which are limited to single-protocol communication, the presented framework enables unified firmware management across heterogeneous IoT protocols under a common server-driven infrastructure.

The experimentally observed energy consumption closely matched the analytical estimate derived in Section, confirming that communication energy dominates the overall OTA process cost. This correlation validates the accuracy of the analytical model and supports the assumption that optimization of transmission parameters yields the most significant energy savings.

Table 3.

Comparison of OTA performance across existing implementations.

Table 3.

Comparison of OTA performance across existing implementations.

| Implementation |

Update Time [s] |

Protocols Supported |

Version Control |

| Espressif OTA Library |

22 (Wi-Fi) |

Single |

No |

| Zigbee2MQTT OTA |

60 (Zigbee) |

Single |

Partial |

| Proposed System |

18 (Wi-Fi), 65 (BLE) |

Multi-protocol |

Yes |

Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed OTA update solution is scalable, resilient, and suitable for deployment in environments where both testing and stable operation must coexist. The combination of analytical validation, repeatable experiments, and multi-protocol comparison provides a comprehensive proof of concept, supporting the framework’s applicability to diverse IoT ecosystems.

7. Future Work

Building on the current implementation, we plan to extend our system with a focus on automation, reliability, and ease of deployment for ESP32-based devices. The following directions represent key priorities.

7.1. OTA update infrastructure for ESP32 (BLE and Zigbee)

A key enhancement is the implementation of an automated over-the-air (OTA) update architecture for ESP32 devices. Our focus is on supporting:

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE): For provisioning and local OTA updates in close-range or mobile-app-assisted environments.

Zigbee (via ESP32 with Zigbee module): For mesh-based, remote update distribution across large networks of ESP32 devices.

The update mechanism will include:

Version checking and secure update delivery.

Rollback capability in case of failure.

Modular firmware packaging to reduce bandwidth.

This will greatly improve long-term maintainability and remote support capabilities.

7.2. Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) Pipeline Integration

To enhance reliability and speed of firmware delivery, we plan to adopt a CI/CD pipeline tailored to ESP32 development, which will include:

Automatic testing of build success for each commit.

Static code analysis and linting to enforce coding standards.

Automated deployment of verified firmware images to the remote build/update server.

This pipeline will help detect issues early, enforce quality control, and support faster release cycles.

7.3. Remote Build Server for ESP32

We intend to develop a remote build server dedicated to ESP32 firmware compilation. This server will provide:

Centralized, reproducible builds using the Espressif IoT Development Framework (ESP-IDF) or

Arduino-ESP32 toolchains.

Web or API interfaces to trigger builds remotely (e.g., from a Git repository).

Build caching and artifact management for efficient development workflows.

This setup will eliminate the need for local toolchain configuration, simplify onboarding, and ensure consistent build outputs across all developers and CI jobs.

7.4. Self-diagnosis of Release Tags

An important planned enhancement is the introduction of a self-diagnosis mechanism for release tags. Each deployed firmware version will automatically collect diagnostic feedback from devices in the field, linking performance and stability data directly to the corresponding release. This mechanism will provide:

Percentage of devices affected by faults for a given release.

Classification of fault types (e.g., connectivity failures, bootloader mismatches, installation errors, runtime crashes).

Automatic aggregation of fault statistics and trend analysis over time.

By quantifying the health of each release, the system will enable developers to make informed decisions regarding rollbacks, targeted fixes, or gradual rollout strategies. In the long term, these diagnostics can be combined with machine learning techniques for fault clustering and prediction, further improving the reliability and resilience of OTA deployments.

7.5. Bare-metal Rust and OTA Updates on ESP32

An important direction for future development is the integration of bare-metal Rust into the OTA update workflow for ESP32-based devices. Rust has gained popularity in embedded systems due to its emphasis on memory safety, concurrency, and performance. Exploring Rust-based OTA implementations offers several expected benefits:

Memory safety: leveraging Rust’s ownership model to minimize the risk of runtime crashes or memory corruption during critical update processes.

Efficient concurrency: using Rust’s async capabilities to handle network requests and flash operations in parallel, improving responsiveness.

Cross-platform tooling: adopting the esp-rs ecosystem to ensure modern tooling support and compatibility across multiple targets.

In the planned architecture, the ESP32 device will periodically check the update server for new firmware releases, download the binary, and perform integrity verification (e.g., Secure Hash

Algorithm 256-bit (SHA-256) or Ed25519 signatures). The firmware image will then be written into an inactive flash partition. After successful verification, the bootloader will update the partition table and activate the new firmware on restart. This workflow is expected to provide reliability comparable to the C-based ESP-IDF OTA libraries, while benefiting from the additional safety and maintainability of the Rust ecosystem.

7.6. Security Considerations for OTA Updates

Although the current work focused on functionality and scalability, the security of OTA processes remains a crucial research topic. Several studies have highlighted vulnerabilities in ESP32’s OTA mechanisms, including unencrypted firmware transfers, replay attacks, and weak signature verification [

27,

28,

29,

30]. These issues may compromise firmware integrity and allow unauthorized access or code injection into IoT devices.

Recent research has demonstrated that OTA update channels can be targeted through cross-protocol attacks, packet sniffing, or denial-of-service techniques [

29,

30]. For example, Baek et al. simulated TCP SYN flooding and ARP spoofing attacks that disrupted OTA updates on ESP32-based drones, while Cayre et al. analyzed low-level firmware vulnerabilities that enable direct memory tampering in the ESP32 architecture. These findings highlight the importance of integrating robust encryption, authentication, and memory protection into OTA frameworks.

To address these challenges, future versions of the proposed system will incorporate mutual authentication between the device and the update server, digital firmware signing using modern cryptographic algorithms such as Ed25519, and encrypted HTTPS update channels. In addition, integrity checks based on digital signatures and secure hash verification will be required before firmware activation to ensure both authenticity and tamper resistance.

Building upon these approaches, our future work will extend the OTA architecture to include adaptive encryption, rollback protection, and self-diagnosis of firmware integrity, ensuring that ESP32-based IoT systems remain reliable, scalable, and resilient against security threats.

Conclusions

This work presented the design and validation of an advanced OTA update architecture for ESP32-based devices. The system ensures reliable version management, supports separation between development and production firmware, and provides an automated mechanism for distributing updates to multiple devices. Experimental evaluation with up to twenty connected devices confirmed the stability and scalability of the proposed solution. The architecture successfully distinguished between development and production tracks, enabling rapid testing of experimental builds without compromising the reliability of production deployments.

The proposed system reduces the operational overhead of manual firmware updates and provides a flexible framework that can be extended with additional features such as CI/CD pipeline integration, build automation, and support for multiple communication technologies. By combining version control, automated distribution, and robust verification mechanisms, the OTA update solution described here demonstrates strong potential for long-term maintainability and large-scale IoT deployments.

Beyond Wi-Fi, this work also explored more complex OTA architectures over BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, and GSM. These extensions demonstrate that OTA updates can be adapted to diverse network environments by optimizing dataflow through packet segmentation, caching, incremental distribution, and congestion-aware scheduling. Such optimizations are essential to maintain reliability under constrained bandwidth and energy conditions.

Planned enhancements include the integration of bare-metal Rust into the OTA workflow, leveraging memory safety, efficient concurrency, and modern tooling to increase reliability and maintainability for ESP32 devices. In addition, a self-diagnosis mechanism for release tags will be introduced, enabling automatic collection and aggregation of diagnostic data, fault percentages, and fault types (e.g., connectivity failures, bootloader mismatches, installation errors, and runtime crashes). This capability will allow developers to evaluate release quality in real time and guide decisions regarding rollbacks, targeted fixes, and staged deployments.

Overall, the results confirm that the proposed OTA architecture is stable, scalable, and extensible. With future integration of multi-protocol delivery, secure build pipelines, release self-diagnostics, and Rust-based implementations, the system will further strengthen the reliability, adaptability, and sustainability of OTA updates in complex and large-scale IoT environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, L.F.; software, P.K. and M.K..; validation L.F.; formal analysis, P.K. and O.K.; investigation, resources, O.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and O.K.; visualization, M.K. and P.K.; supervision, O.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of AI-based language modeling tools, which were used to assist in correcting grammar, improving sentence clarity, and enhancing the overall readability of this manuscript. All technical content, methodologies, and conclusions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Olesnanikova, V.; Karpis, O.; Chovanec, M.; Sarafin, P.; Zalman, R. Water level monitoring based on the acoustic signal using the neural network. 2016, p. 203 – 206. Cited by: 3. [CrossRef]

- Zyrianoff, I.; Montori, F.; Trotta, A.; Sciullo, L.; Gigli, L.; Kamienski, C.; Di Felice, M. A Location-Aware WebAssembly-Based Software Update Framework for IoT End Devices. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 22nd Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–4.

- Mazhar, S.; Rakib, A.; Doss, R.; Anwar, A.; Jiang, F. Integrating Threat Analysis and Formal Verification for Secure OTA Updates. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing (PRDC 2025). IEEE, 2025, pp. In–Press.

- Chochul, M.; Ševčík, P. A Survey of Low Power Wide Area Network Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2020 18th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), 2020, pp. 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Xing, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zheng, F.; Hu, D. Design of Over-the-Air Firmware Update and Management for IoT Device with Cloud-based RESTful Web Services. In Proceedings of the 2021 China Automation Congress (CAC), 2021, pp. 5081–5085. [CrossRef]

- Moses, G.E.; Oyineteimode, Y. Software Development Process for an IOT-Based Fingerprint Device Based on ESP32 MCU.

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Z. Research on Security for Software Updates of Intelligent Connected Vehicles Based on Post-Quantum Cryptography. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Automation and Information Science (EEAIS). IEEE, 2025, pp. 160–164.

- Kovacevic, A.; Gligoric, N. Enhancing Security of Automotive OTA Firmware Updates via Decentralized Identifiers and Distributed Ledger Technology. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, I.G. Secure and Lightweight Firmware Over-the-Air Update Mechanism for Internet of Things. Electronics 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, V.; Saldana, J.; Berné, G.; Modrego, J. Firmware Updates over the Air via LoRa: Unicast and Broadcast Combination for Boosting Update Speed. Sensors 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Neves, B.P.; Valente, A.; Santos, V.D.N. Efficient Runtime Firmware Update Mechanism for LoRaWAN Class A Devices. Eng 2024, 5, 2610–2632. [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudhi, F.; Sultania, A.K.; Famaey, J. Over-the-Air Firmware Updates for Constrained NB-IoT Devices. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Ševčík, P.; Žák, S.; Hodoň, M. Wireless sensor network for smart power metering. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2017, 29, e4247, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/cpe.4247]. e4247 cpe.4247. [CrossRef]

- Hodon, M.; Chovanec, M.; Čechovič, L.; Hudik, M.; Milanova, J.; Kochlan, M.; Jurecka, M.; Kapitulik, J.; Sevcik, P. Maximizing performance of low-power WSN node on the basis of event-driven-programming approach: Minimization of operational energy costs of WSN node control unit. 07 2015, pp. 204–209. [CrossRef]

- Kochlan, M.; Zak, S.; Micek, J.; Hodon, M.; Hudik, M. Performance of Open Voltage Control Algorithm for Sensor Node Power Management Unit. In Proceedings of the 2016 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INFORMATION AND DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES (IDT). IEEE; ESRA, 2016, pp. 138–143. International Conference on Information and Digital Technologies (IDT), Rzeszow, POLAND, JUL 05-07, 2016.

- Rehman, A.; Abdullah, S.; Fatima, M.; Iqbal, M.W.; Almarhabi, K.A.; Ashraf, M.U.; Ali, S. Ensuring Security and Energy Efficiency of Wireless Sensor Network by Using Blockchain. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Khan, F.S.; Mohy-ud din, Z.; Hassany, N.; Gul, J.Z.; Khan, M.; Kim, W.Y.; Park, Y.C.; Rehman, M.M. A Hybrid Approach for Energy Consumption and Improvement in Sensor Network Lifespan in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kubaščík, M.; Tupý, I.A.; Šumský, J.; Bača, T. OTA firmware updates on ESP32 based microcontrolers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 17th International Scientific Conference on Informatics (Informatics), 2024, pp. 185–189. [CrossRef]

- Over The Air Updates (OTA). https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-idf/en/stable/esp32/api-reference/

system/ota.html.

- Over The Air Updates (OTA) API. https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-idf/en/release-v3.0/api-reference/system/ota.html.

- Serepas, F.; Papias, I.; Christakis, K.; Dimitropoulos, N.; Marinakis, V. Lightweight Embedded IoT Gateway for Smart Homes Based on an ESP32 Microcontroller. Computers 2025, 14, 391.

- Mahmood, S.; Nguyen, H.N.; Shaikh, S.A. Systematic threat assessment and security testing of automotive over-the-air (OTA) updates. Vehicular Communications 2022, 35, 100468.

- Ota 3 protocols. https://github.com/kubascikmichal/esp-ota.

- Ota via Wi-Fi example. https://github.com/espressif/esp-idf/tree/master/examples/system/ota/simple_

ota_example.

- Ota via BLE example. https://github.com/espressif/esp-iot-solution/tree/master/examples/bluetooth/

ble_ota.

- Ota via Zigbee example. https://github.com/espressif/esp-zigbee-sdk/tree/62d67374bfc59dd002be2fcf0

3cca52caaf5d525/examples/esp_zigbee_ota.

- Ahsan, M.S.; Pathan, A.S.K. A Comprehensive Survey on the Requirements, Applications, and Future Challenges for Access Control Models in IoT: The State of the Art. IoT 2025, 6, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zandberg, K.; Schleiser, K.; Acosta, F.; Tschofenig, H.; Baccelli, E. Secure Firmware Updates for Constrained IoT Devices Using Open Standards: A Reality Check. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 71907–71920. [CrossRef]

- Cayre, R.; Cauquil, D.; Francillon, A. ESPwn32: Hacking with ESP32 System-on-Chips. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), 2023, pp. 311–325. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Jang, J.; Kim, S. A Study on Vulnerability Analysis and Memory Forensics of ESP32. Journal of Internet Computing and Services 2024, 25, 1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).