The energy sector achieved a significant milestone in 2019 with the establishment of the Canadian Center for Energy Information (CCEI). Housed at Statistics Canada, the CCEI brings together Canada’s existing energy information in one place, facilitating access to products like the Energy Fact Book. For over ten years, the Energy Fact Book has provided a solid foundation for Canadians to understand and discuss significant developments across the energy sector (NRC, 2024a).

3.1. Energy Supply in Canada

As mentioned in the previous subsection, Canada is blessed with large quantities of diverse energy sources, including hydro, wind, solar, ocean (tidal and wave), biomass, uranium, oil, natural gas, coal, oil sands/bitumen, and coal-bed methane. It is an “energy superpower” on the world stage. It is the sixth-largest energy producer in the world (NRC, 2024a). It is the third-largest hydroelectric power-generating country, after China and Brazil, and the fourth-largest oil producer, after the US, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Additionally, it is the fifth-largest natural gas producer, alongside the US, Russia, Iran, and China. It is the second-largest uranium producer in the world after Kazakhstan (Canada Action, 2025).

Canada has some of the world’s largest and safest nuclear-generating stations and several crucial nuclear research facilities. It is one of the few countries in the world that is not only energy-rich but also fully capable of increasing its energy production in an environmentally and economically sustainable manner. These resources, combined with the intellectual and technological skills possessed by Canadians, have made Canada’s domestic and export energy sector one of its biggest economic drivers. The energy sector provides significant employment and economic opportunities, contributing significantly to the lifestyle that Canadians have come to enjoy and expect. For example, in 2006, the industry accounted for 5.9 percent of the national GDP, fuelled by energy production and generation, with over 345,000 people employed in the oil and gas, as well as electricity sectors alone (NRC, 2024b). Canada’s energy sector is substantial in terms of both the quantity produced and traded, as well as its contribution to the country’s GDP. In 2023, the energy sector contributed 10.3 percent to Canada’s GDP and employed 697,000 people (NRC, 2024b). Among different provinces, Alberta alone employs over 150,000 workers. Canada, with only 0.5 percent of the world’s population, produces a substantial amount of energy. Interestingly, it is rich in all forms of energy.

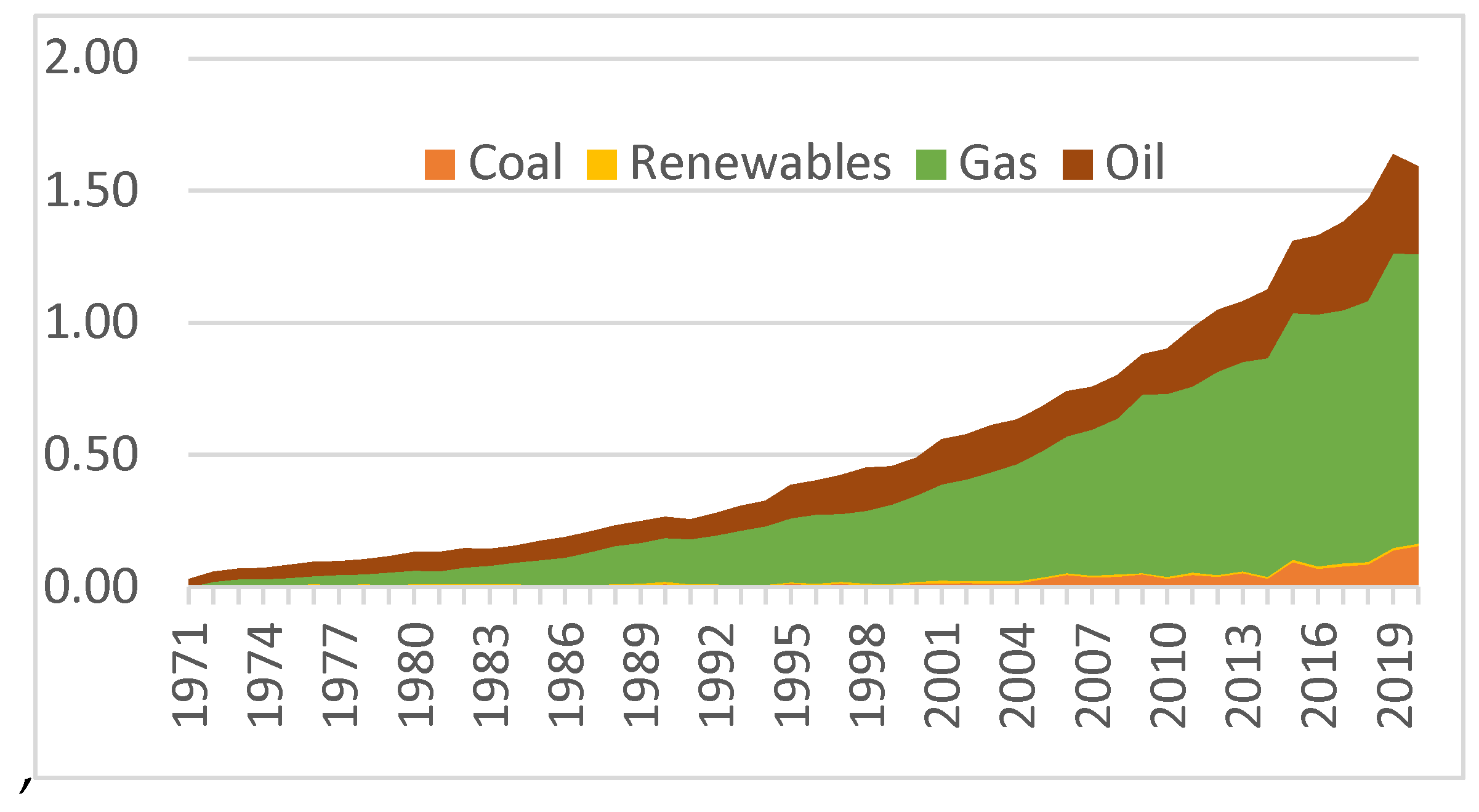

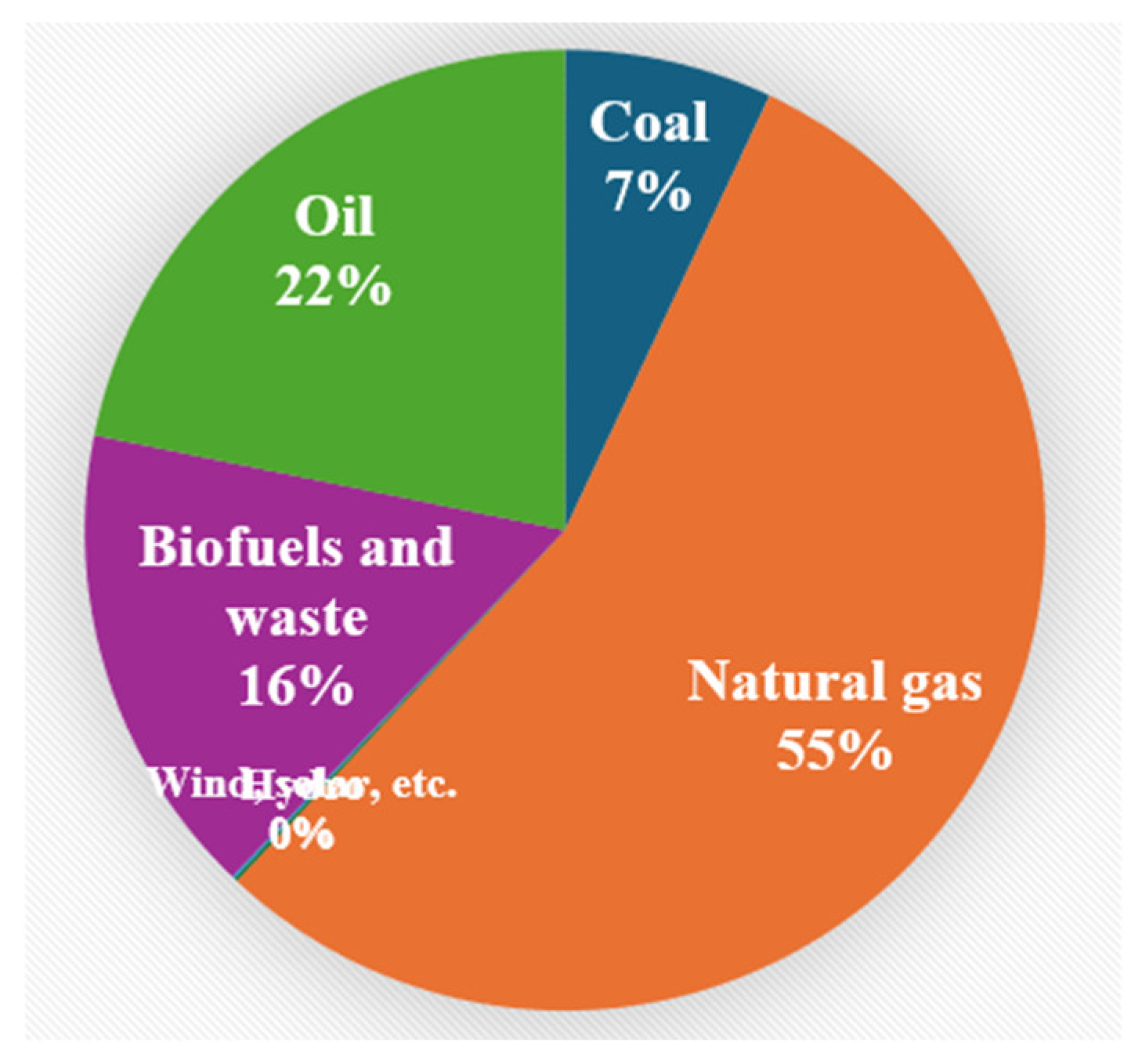

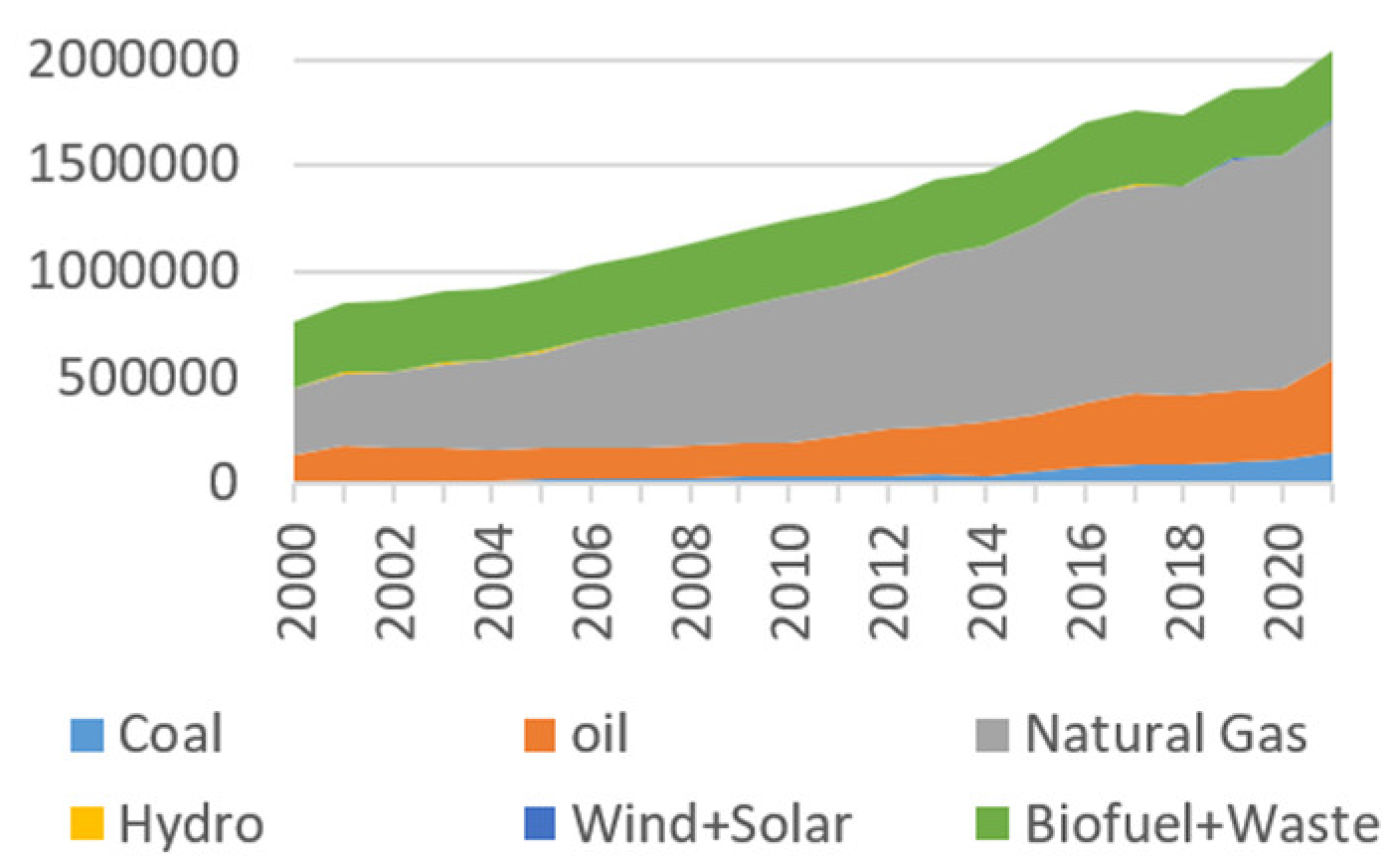

Because of its abundance of energy resources, Canada produces, uses, and exports a diverse portfolio of energy, commonly known as the “energy mix”. The following figure shows the energy mix for Canada in 2021. There may be some variations from one year to the next, but the overall distribution of energy remains more or less the same.

Figure 9.

Canada’s energy production mix, including uranium [Source: NRC, 2024a].

Figure 9.

Canada’s energy production mix, including uranium [Source: NRC, 2024a].

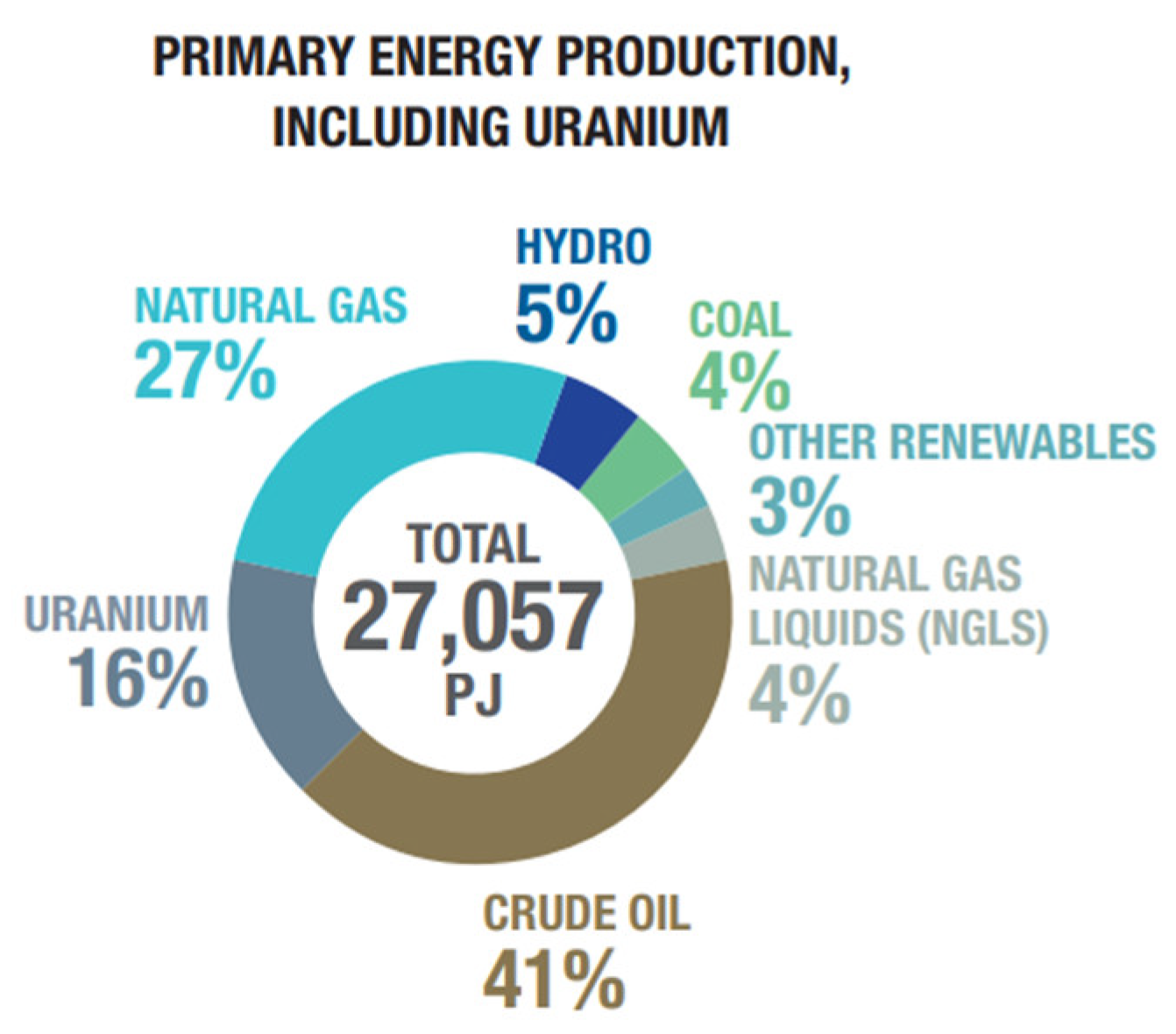

Canada’s energy production and domestic supply are not the same, as it exports nearly all forms of energy it produces. So, the domestic supply is calculated as:

In 2022, Canada’s energy supply mix was 76 percent fossil fuel (2, 41, and 33 percent coal, natural gas and oil, respectively) [Figure below], 16 percent renewable and eight percent nuclear, compared to the global energy mix of 81 percent fossil fuel (28, 23, and 28 percent, coal, natural gas, and oil, respectively), 14 percent renewable and five percent nuclear (NRC, 2024a).

Figure 10.

Canada’s energy supply mix [Source: NRC, 2024a].

Figure 10.

Canada’s energy supply mix [Source: NRC, 2024a].

The energy sector is also a major contributor to several provincial treasuries and, potentially, to territorial treasuries. In 2005, petroleum companies and electrical utilities contributed over $3 billion in royalties, bonuses, fees, dividends, and taxes to Canadian provinces and territories, which support critical programs such as health and education.

Canadian energy production, particularly in the non-renewable sector, faces significant challenges. While Canada’s conventional energy sources, such as oil, natural gas, and coal, still have significant potential to meet demand over the short to medium term, these non-renewable energy sources are becoming increasingly challenging to find and more costly to extract. Therefore, new sources must be developed (CAPP, 2006). As the world has turned its attention to the critical issue of climate change, it is increasingly essential to create, transport, and use energy resources in an environmentally responsible manner. Many stakeholders, communities, and Aboriginal peoples are seeking increased opportunities to provide input into energy policy and resource management.

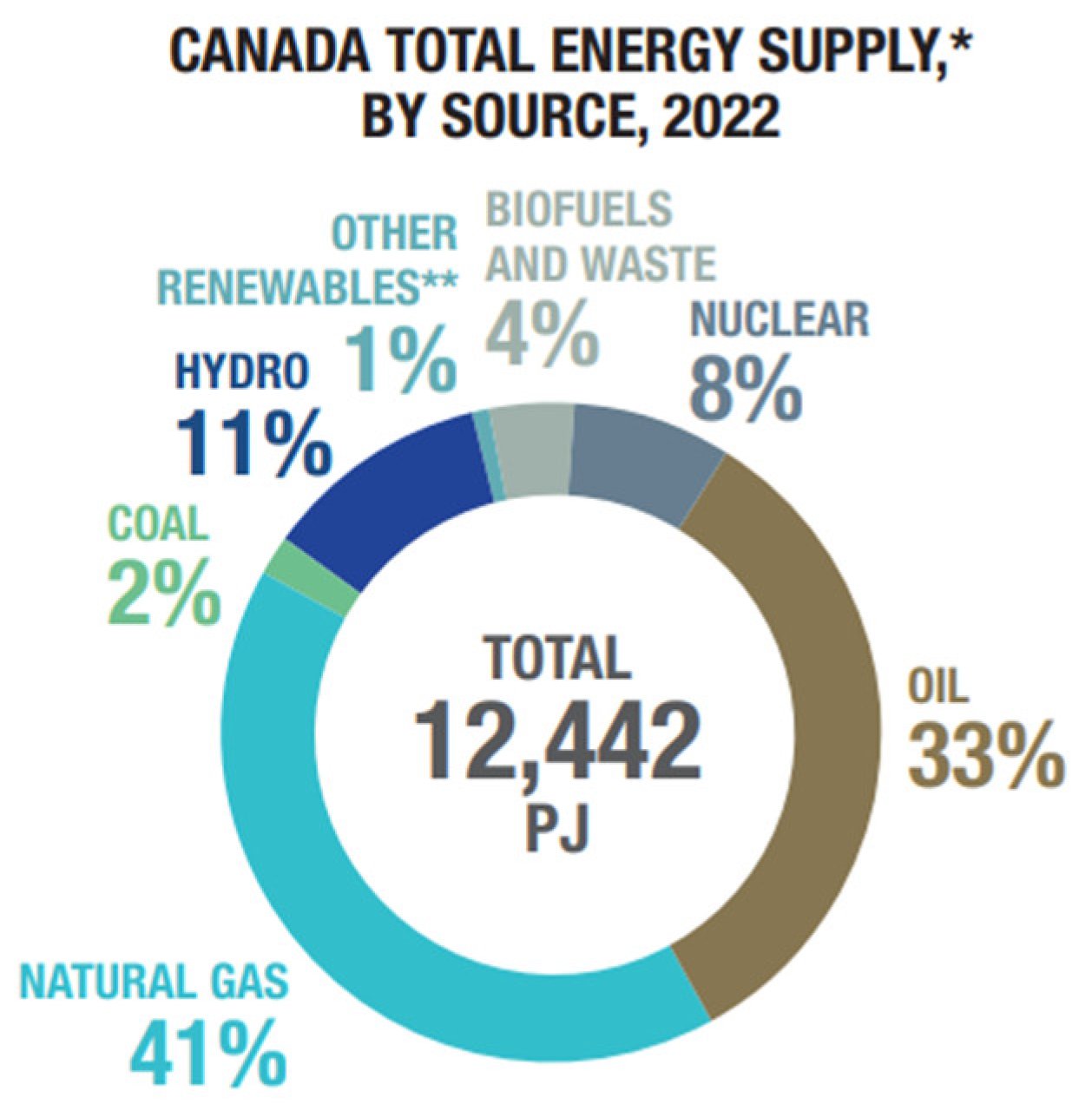

3.1.1. Fossil Energy Supply in Canada

Canada has three primary fossil energies – coal, oil, and natural gas. Over time, due to climate change and environmental concerns, coal production has been declining steadily. Indeed, the Government of Canada is in the process of phasing out the extensive use of coal for electricity production. Canada holds vast reserves of fossil fuels, particularly in the western provinces. The most prominent resource is crude oil, particularly in the form of oil sands, with Alberta serving as the hub of production. In 2021, Canada was the sixth-largest primary energy-producing country in the world, with over 80 percent of its energy coming from fossil fuels (NRC, 2024a). Crude oil is by far the most significant primary energy source in Canada. The energy sector contributes over 10 percent of the country’s GDP and employs more than half a million people (NRC, 2024a). It has a vast amount of primary energy reserves in various forms.

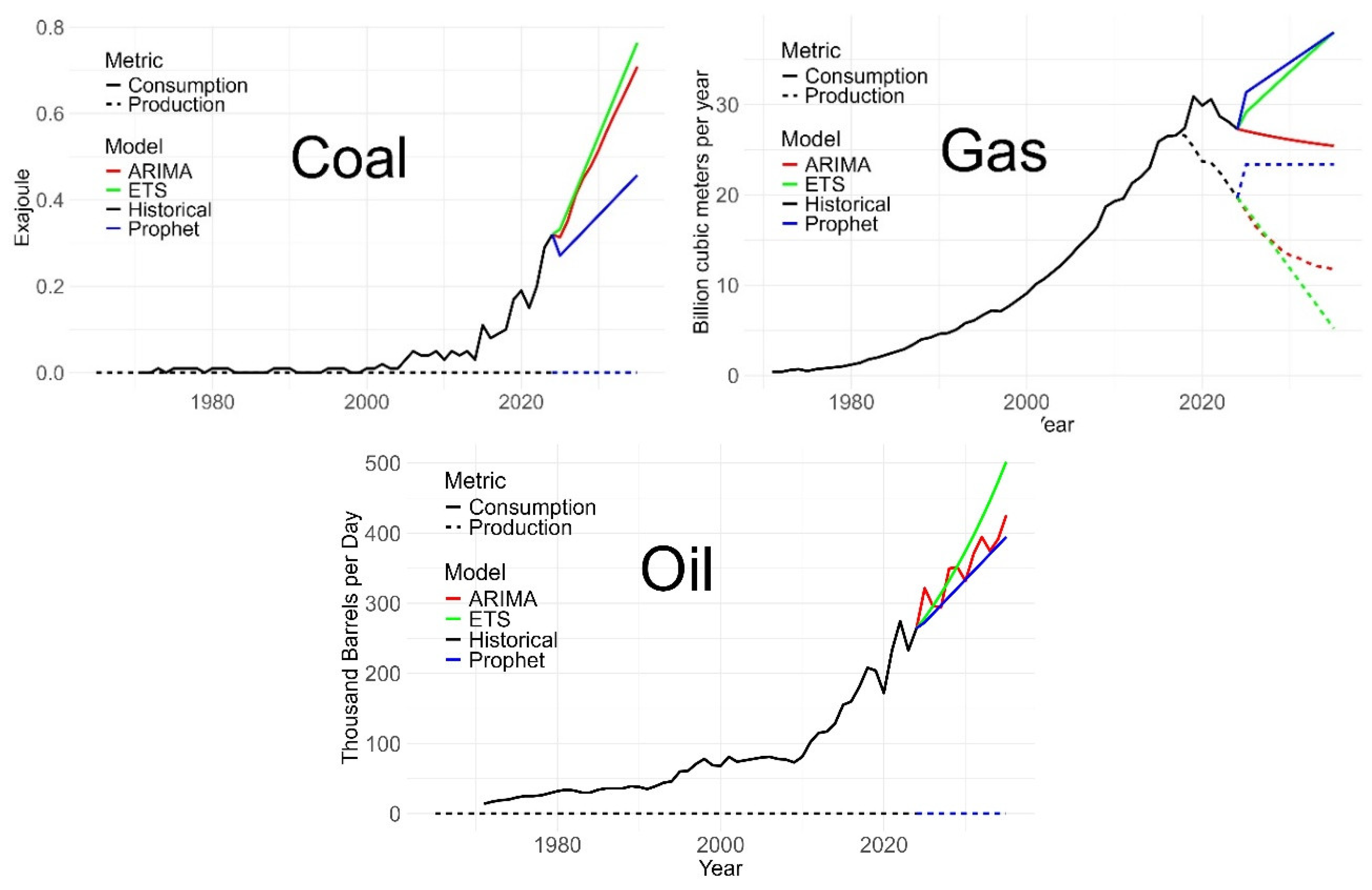

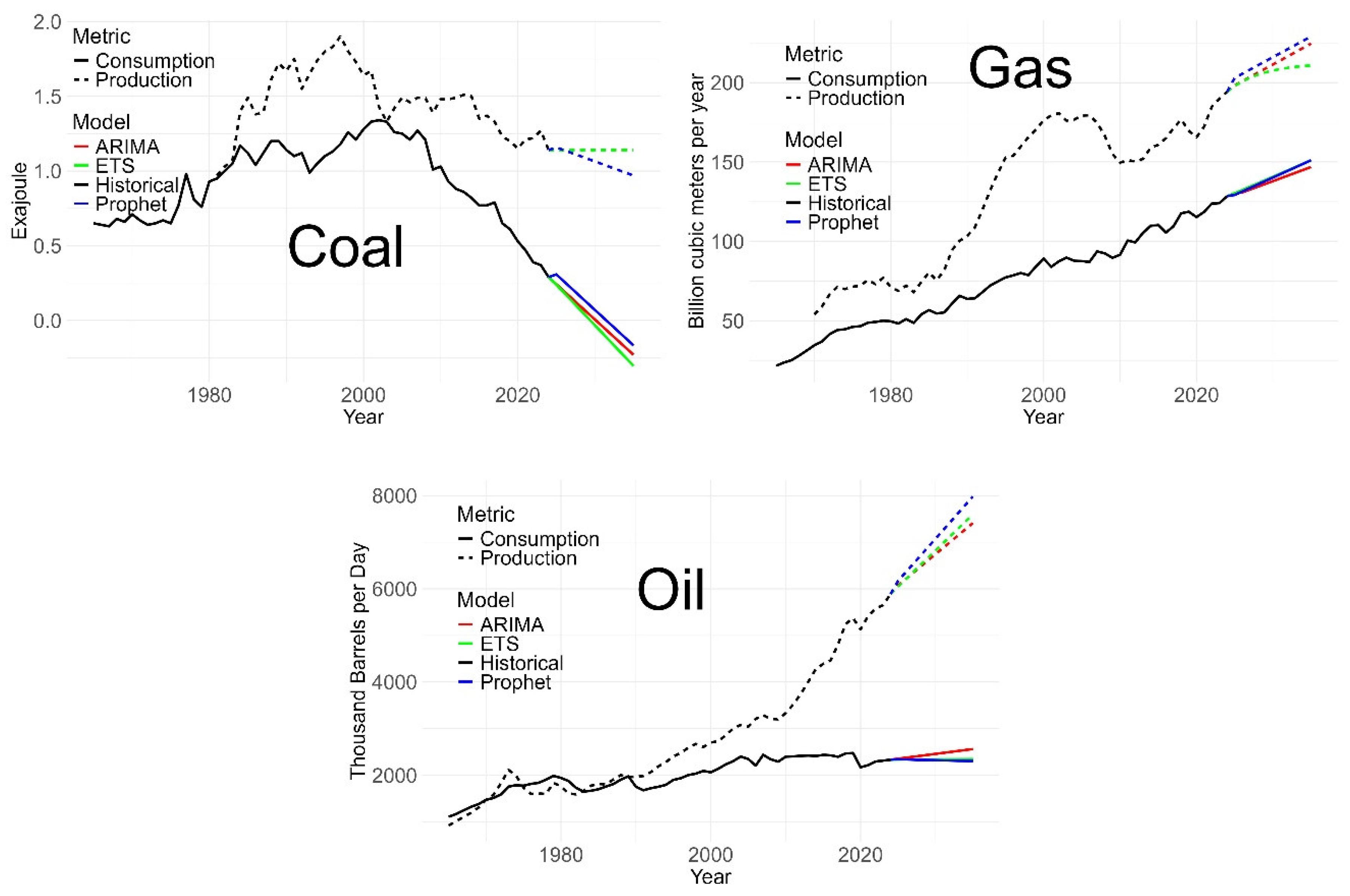

Figure 11.

Fossil fuel (Coal, oil, and natural gas) production in Canada, 1991-2024, indexed to 1991. [Source: Energy Institute, 2025].

Figure 11.

Fossil fuel (Coal, oil, and natural gas) production in Canada, 1991-2024, indexed to 1991. [Source: Energy Institute, 2025].

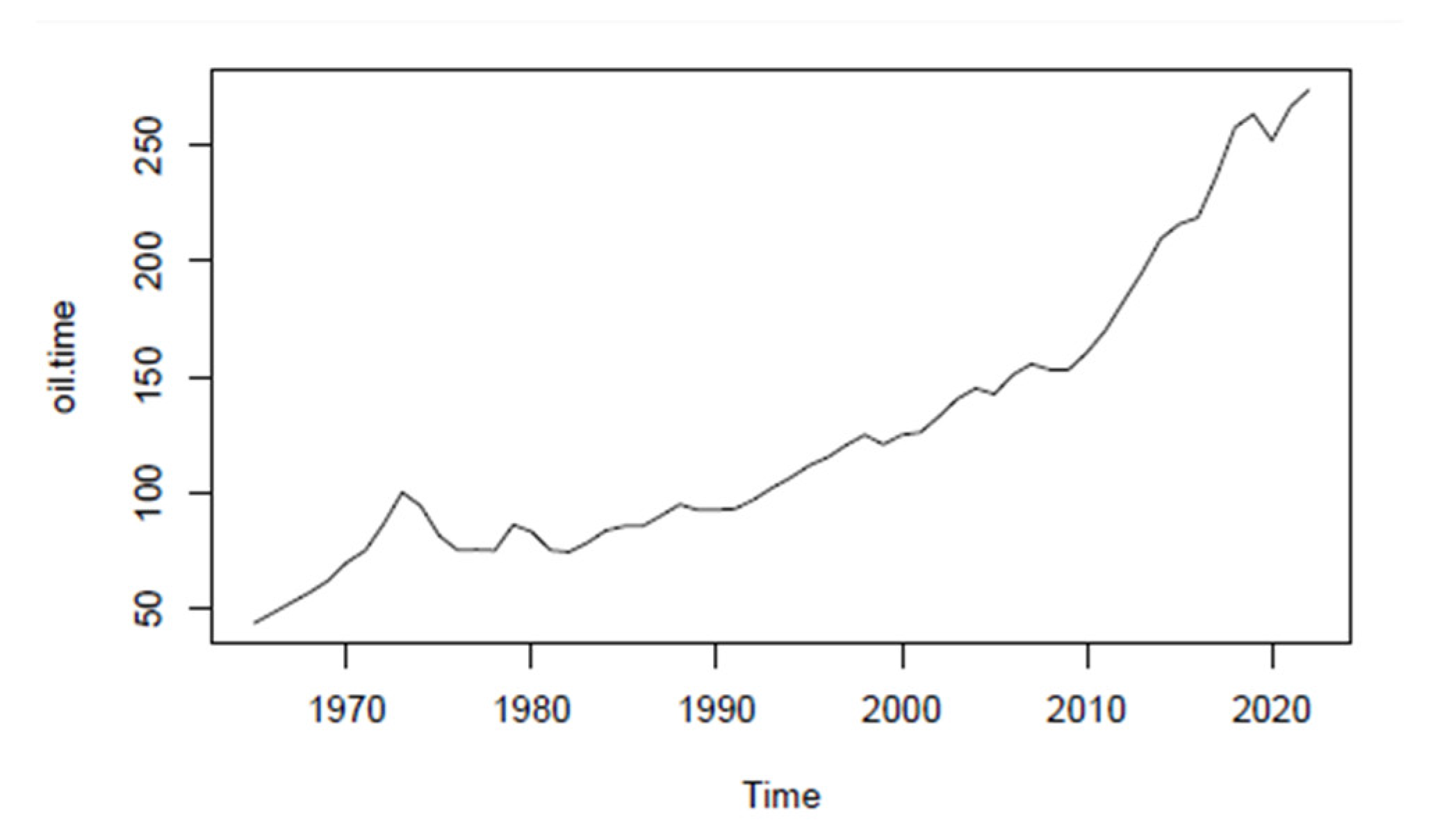

Oil is the primary source of energy and a major contributor to Canada’s export earnings. Although not all provinces have oil resources, some areas are richer than others. Oil production in Canada continued to increase, primarily due to the sustained rise in international crude oil prices and technological advancements in extracting oil from oil sands. New technology, successfully employed in shale gas developments (including horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracture stimulation), has been successfully used in several projects in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Canada now focuses more on its unconventional oil production. By the end of this decade, oilsands production is expected to account for nearly 90 percent of Canadian oil production (NRC, 2013). The shift towards unconventional production has long been anticipated, as 97 percent of Canada’s proved oil reserves are in the form of oil sands.

Canada’s fossil energy sector receives substantial support from the Government, primarily through subsidies (Levin, 2025). The energy sector also generates a considerable income for the resource-rich provincial and federal governments. However, in response to recent environmental concerns, the government has decided to reduce subsidies on the fossil energy sector (Scarpaleggia, 2023). Canada has agreed to phase out coal, which substantially contributes to human health (WHO, 2025). New processes and efficiency improvements are also helping curb the expected demand for natural gas per barrel of oil sands produced. With significant reserves in Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan, Canada is among the world’s top five natural gas producers, with output exceeding 15 billion cubic feet per day in recent years (Energy Institute, 2025). In contrast, coal production has declined due to environmental policies and decreased domestic demand; however, Canada still exports coal, particularly metallurgical coal used in the steelmaking process.

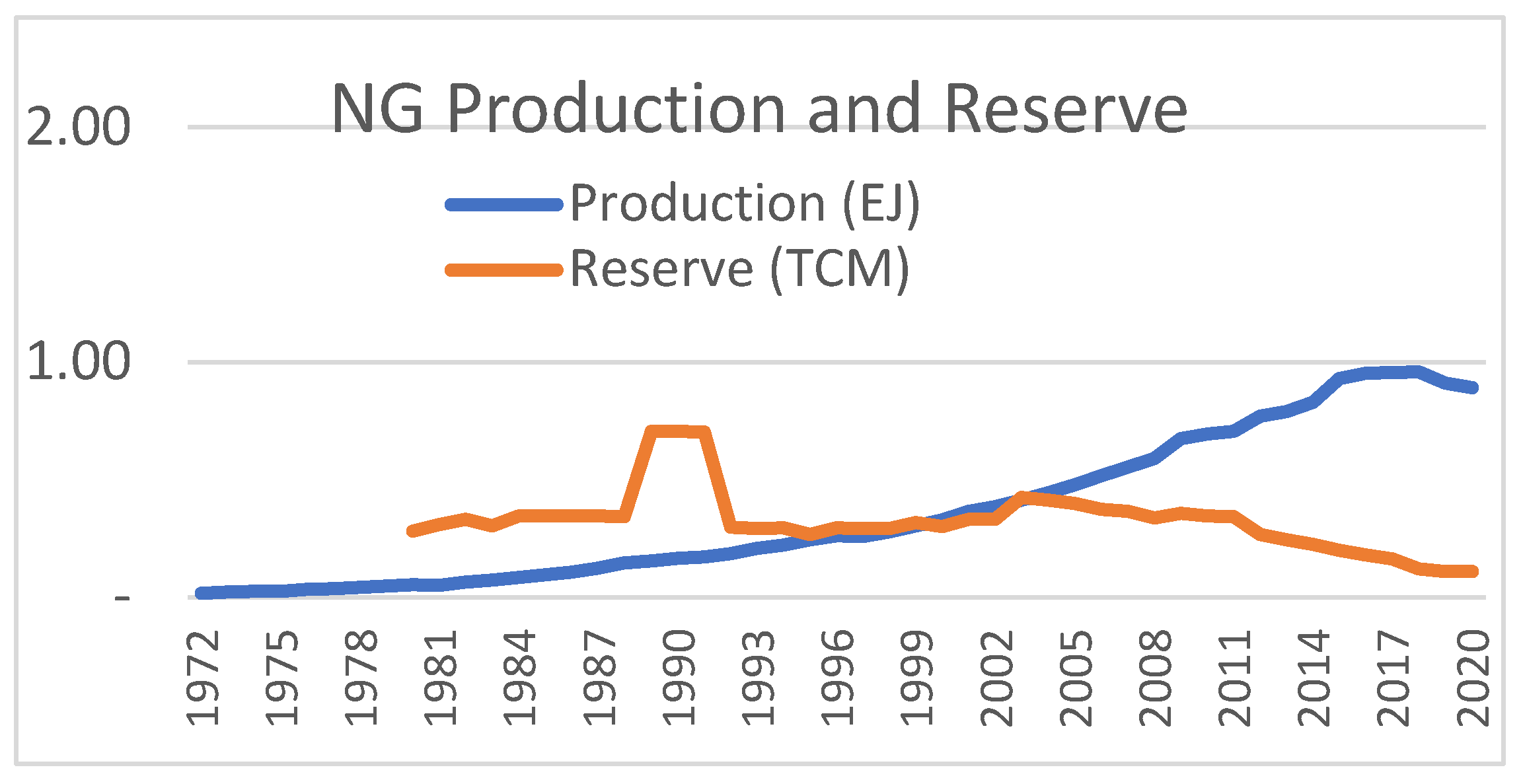

Canada’s natural gas industry began to take off in the mid-20th century, driven by discoveries in Alberta and British Columbia. Today, Canada possesses one of the largest natural gas reserves in the world (Energy Institute, 2025), primarily located in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, which spans Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan. Unconventional sources, such as shale gas and tight gas, have become increasingly important due to advancements in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (Cai et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2024).

Canada is a major exporter of natural gas, with the United States being its primary destination. In 2024, Canada produced over 194 billion cubic meters of natural gas (Energy Institute, 2025), most of which came from Alberta and northeastern British Columbia. Ghose and Islam (2023) used a theoretical model to find that Canada’s entry into the LNG market benefits Canadian firms. The industry has long tried to export its natural gas to the international market beyond the USA with little success. Only recently did the shipment of LNG to Asia from one of its plants begin (Kitimat). Several LNG projects are in development or under construction. These projects aim to diversify Canada’s export markets and enhance energy security for international partners. However, LNG infrastructure development faces challenges, including high costs, regulatory hurdles, and concerns from Indigenous communities and environmental groups. The first LNG shipment from Canada to Asia was on June 30, 2025 (LNG Canada, 2025).

The fossil fuel industry is Canada’s largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, contributing significantly to the country’s climate footprint. Oil sands production, in particular, is energy and water-intensive, raising concerns about air and water pollution, habitat disruption, and Indigenous rights. The future of fossil energy in Canada is uncertain but evolving. While global demand for oil and gas is expected to persist for decades, particularly in developing economies, there is growing pressure to decarbonize. Canada’s fossil energy industry is exploring ways to adapt, such as investing in cleaner extraction technologies, transitioning to hydrogen production, and incorporating carbon capture systems. There is a growing movement toward diversification and innovation in clean energy. Public opinion, investor preferences, and international climate commitments are pushing Canada to rethink its reliance on fossil fuels and invest in a more sustainable energy future.

Fossil energy has long been a pillar of Canada’s economy and energy system. (Clark and Matthews, 2023). While the country remains a major player in global oil and gas markets, it faces mounting challenges related to environmental sustainability and climate change. Balancing economic interests with environmental responsibility will be critical as Canada navigates the transition to a low-carbon future. The evolution of its fossil energy supply will shape not only the nation’s economic trajectory but also its role in the global effort to combat climate change.

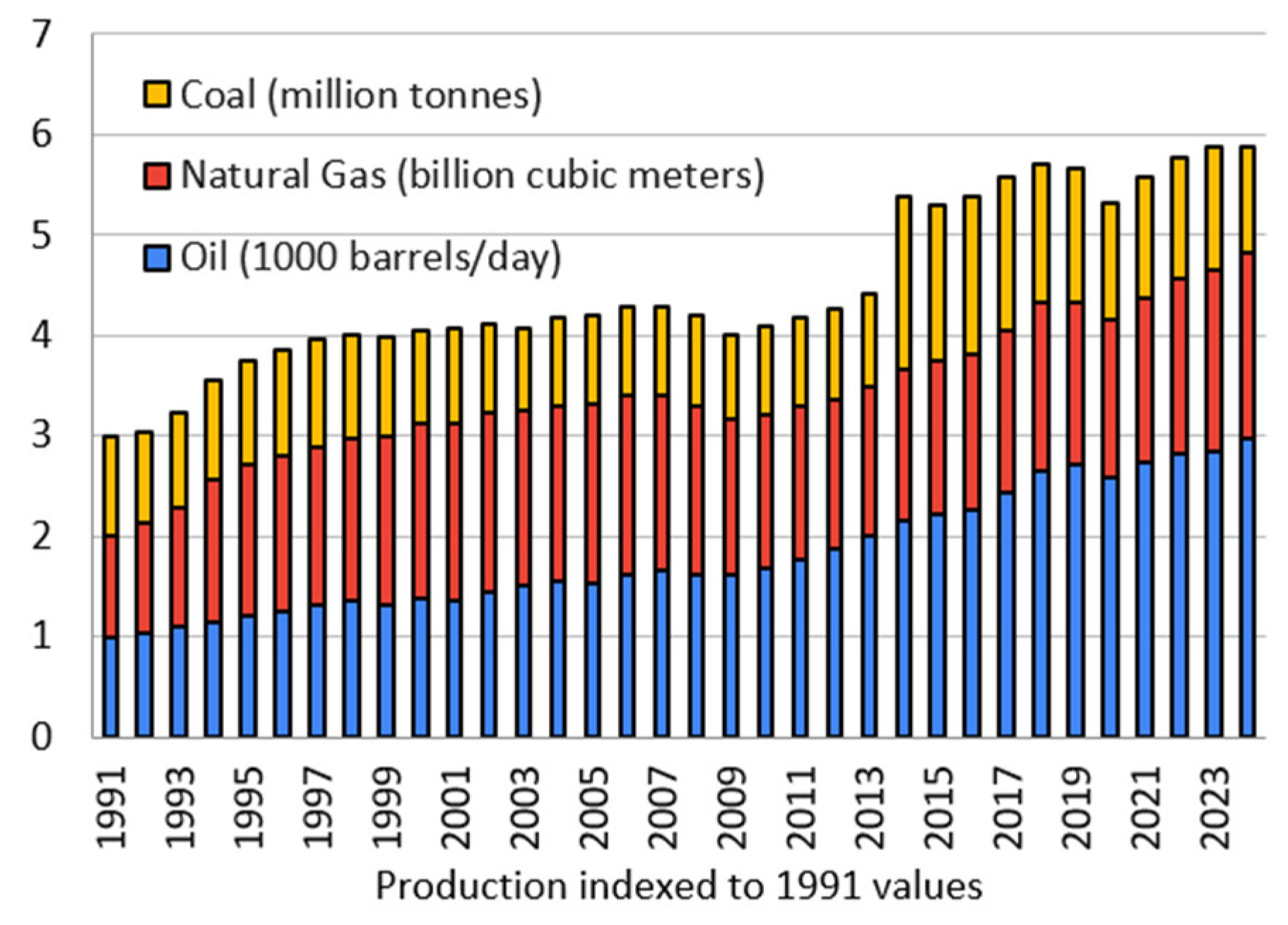

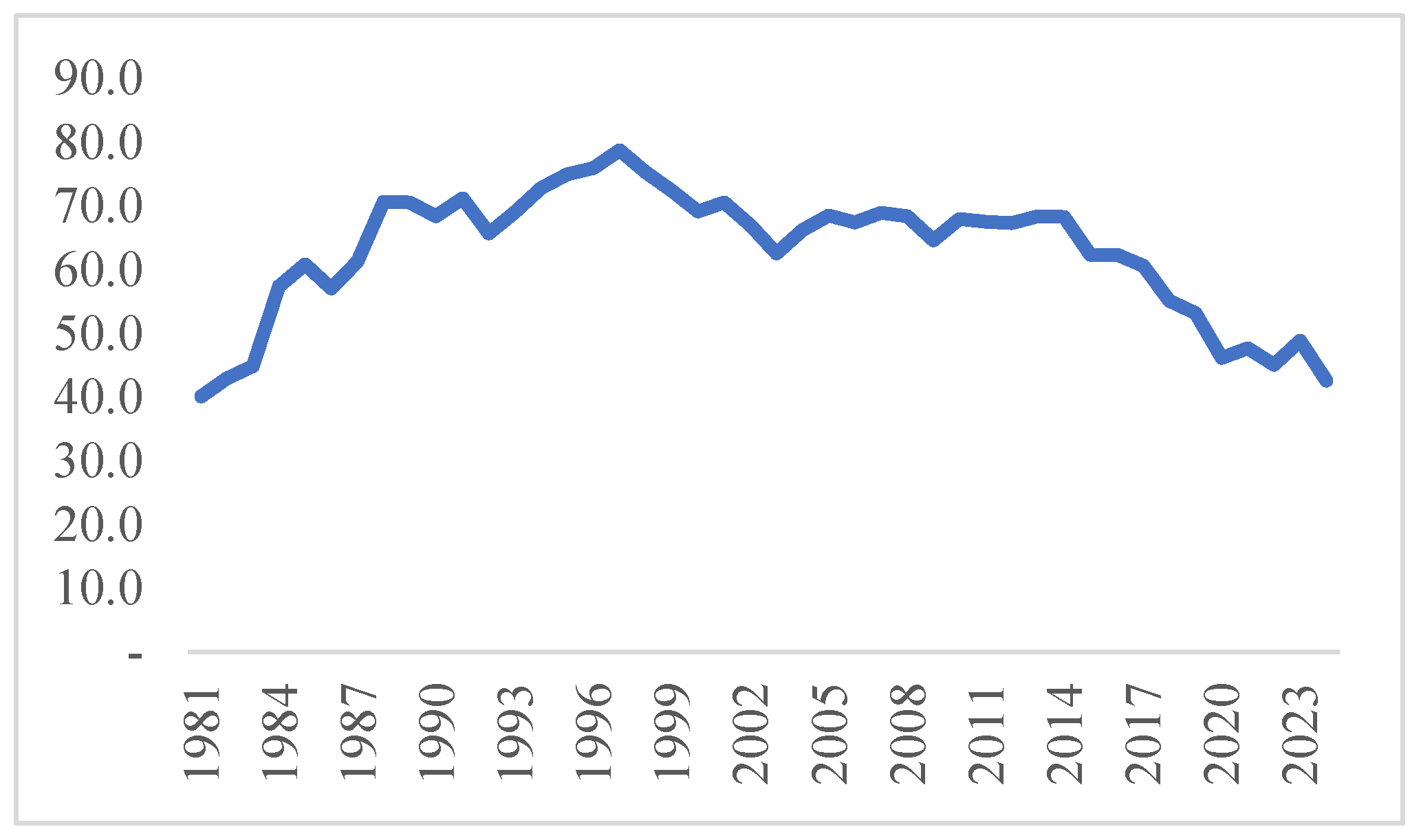

Figure 12.

Oil production trend in Canada [Data source: B.P., 2023; Energy Institute, 2025].

Figure 12.

Oil production trend in Canada [Data source: B.P., 2023; Energy Institute, 2025].

Two ways to combat GHG emissions from Canada are reducing coal production and increasing natural gas production as a transition fuel. Among the three fossil fuels, coal is the worst for contributing to GHG emissions. Canada recognized this almost half a century ago and has made an effort to cut back coal production (Gurtler et al., 2021; Solarin et al., 2021; Bennett et al., 2023). The target is to eliminate coal-fired electricity plants by 2030. However, progress is slow, and the sector may not realize its objectives by 2030 (Gurtler et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the trajectory is in the right direction, and at some point, Canada’s GHG emissions will decline.

The country’s total coal production has been declining since the 1990s, following a period of increase in the 1970s and 1980s (

Figure 13), in response to the world’s energy crisis. The trend continues in the right direction with a more rapid decline in recent years.

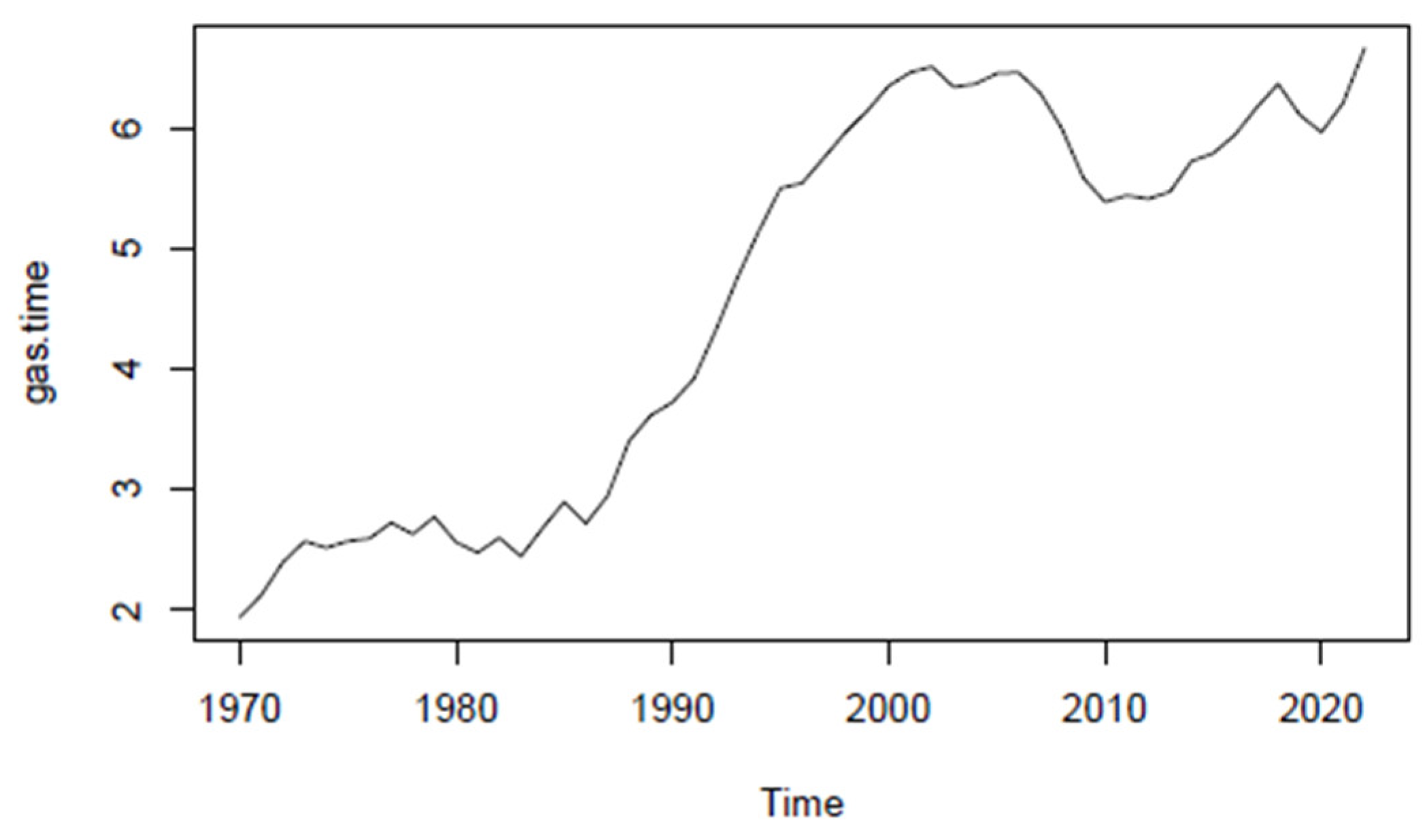

Canada is one of the world’s leading producers of natural gas, with vast reserves that play a crucial role in both the national economy and the global energy market. As the world increasingly looks for cleaner energy alternatives, natural gas is positioned as a transitional fuel, offering a lower-carbon option compared to coal and oil. In Canada, the production and export of natural gas have undergone significant evolution in recent decades (

Figure 14), driven by technological advances, market demands, and environmental considerations.

As the world transitions to net-zero emissions, natural gas in Canada may serve as a bridge fuel, supporting energy reliability and economic development. In contrast, renewable energy capacity continues to expand (IRENA, 2025). However, this will require ongoing investment, robust regulation, and meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities to ensure sustainable development.

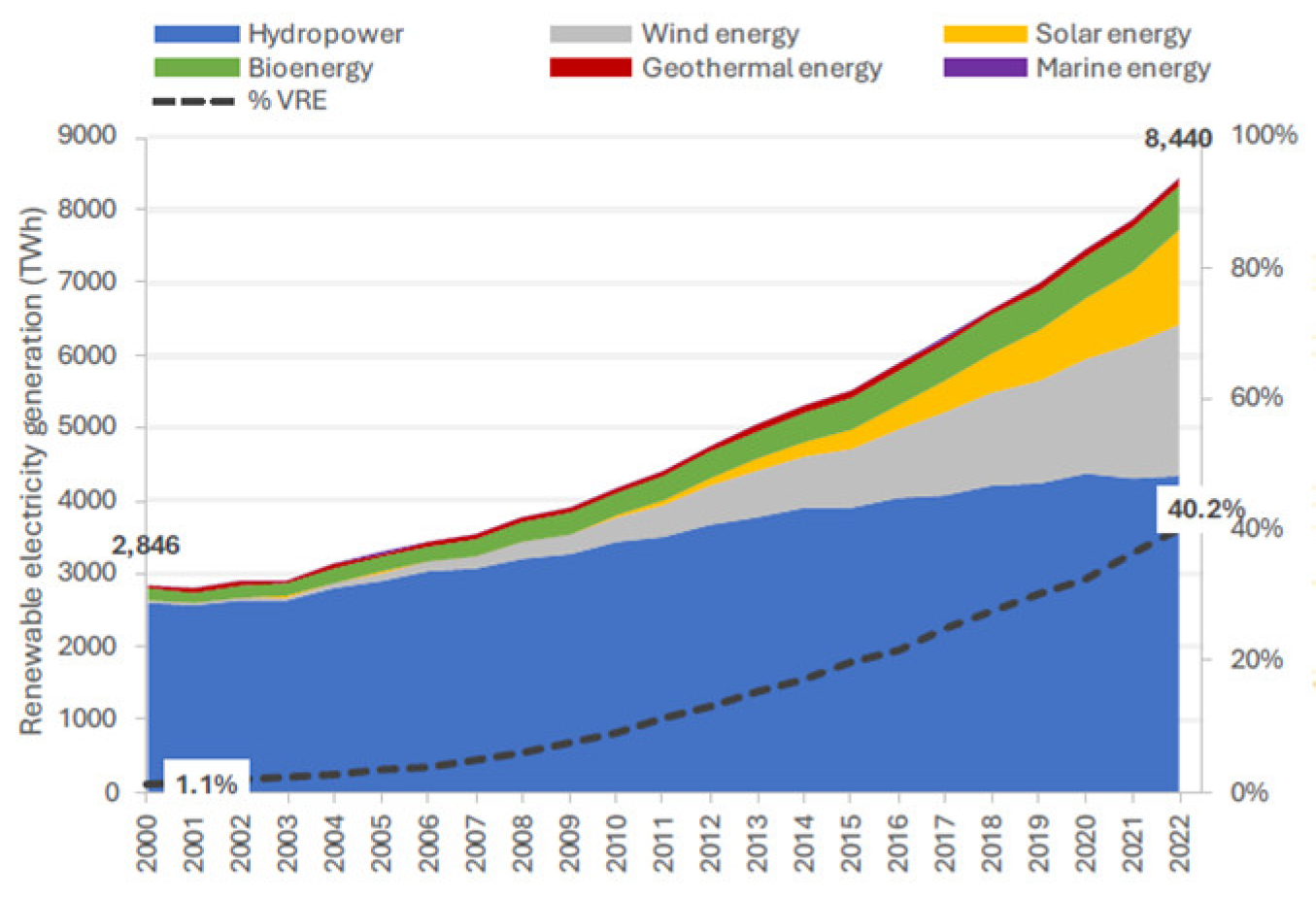

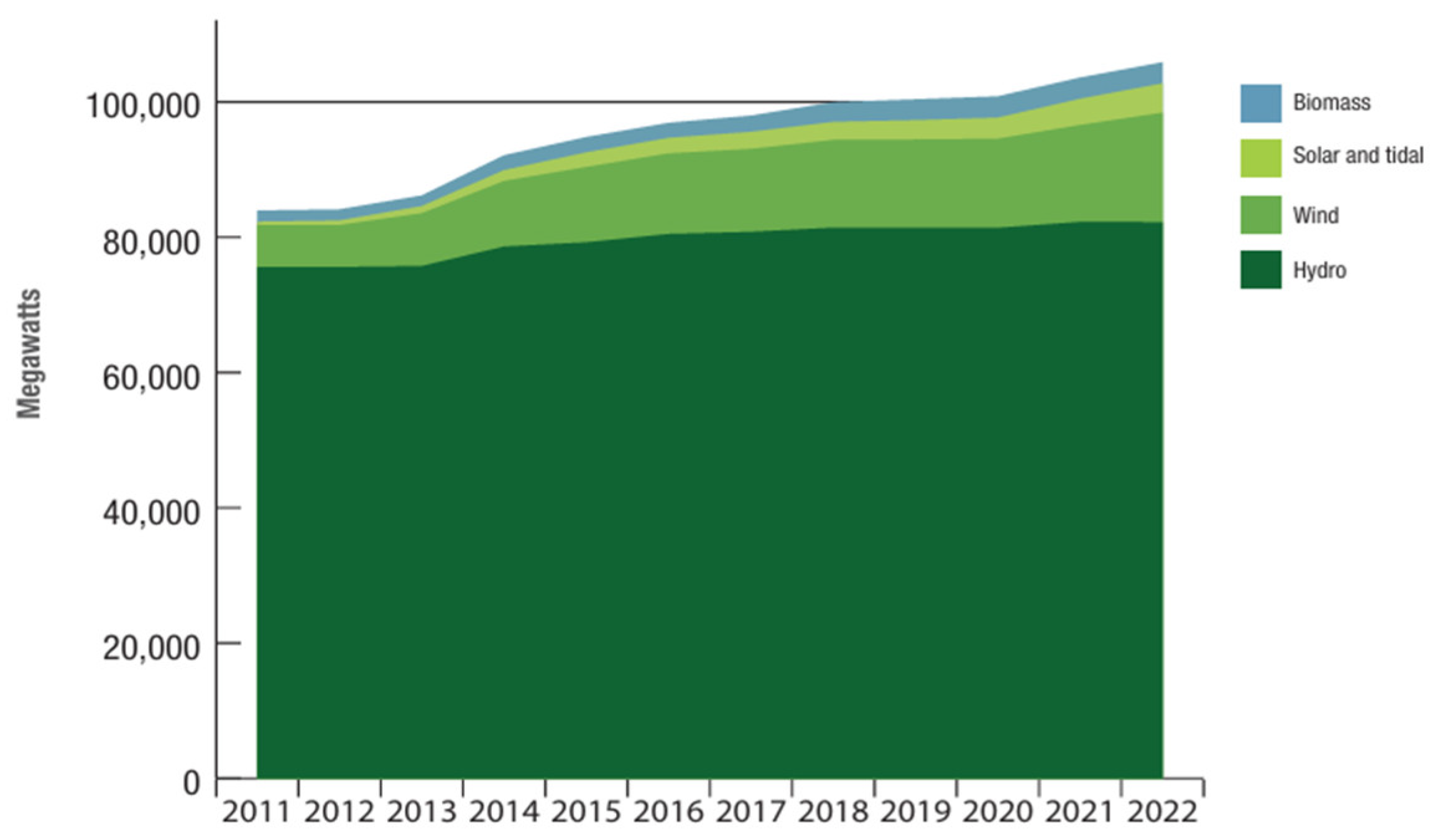

3.1.2. Renewable Energy Supply in Canada

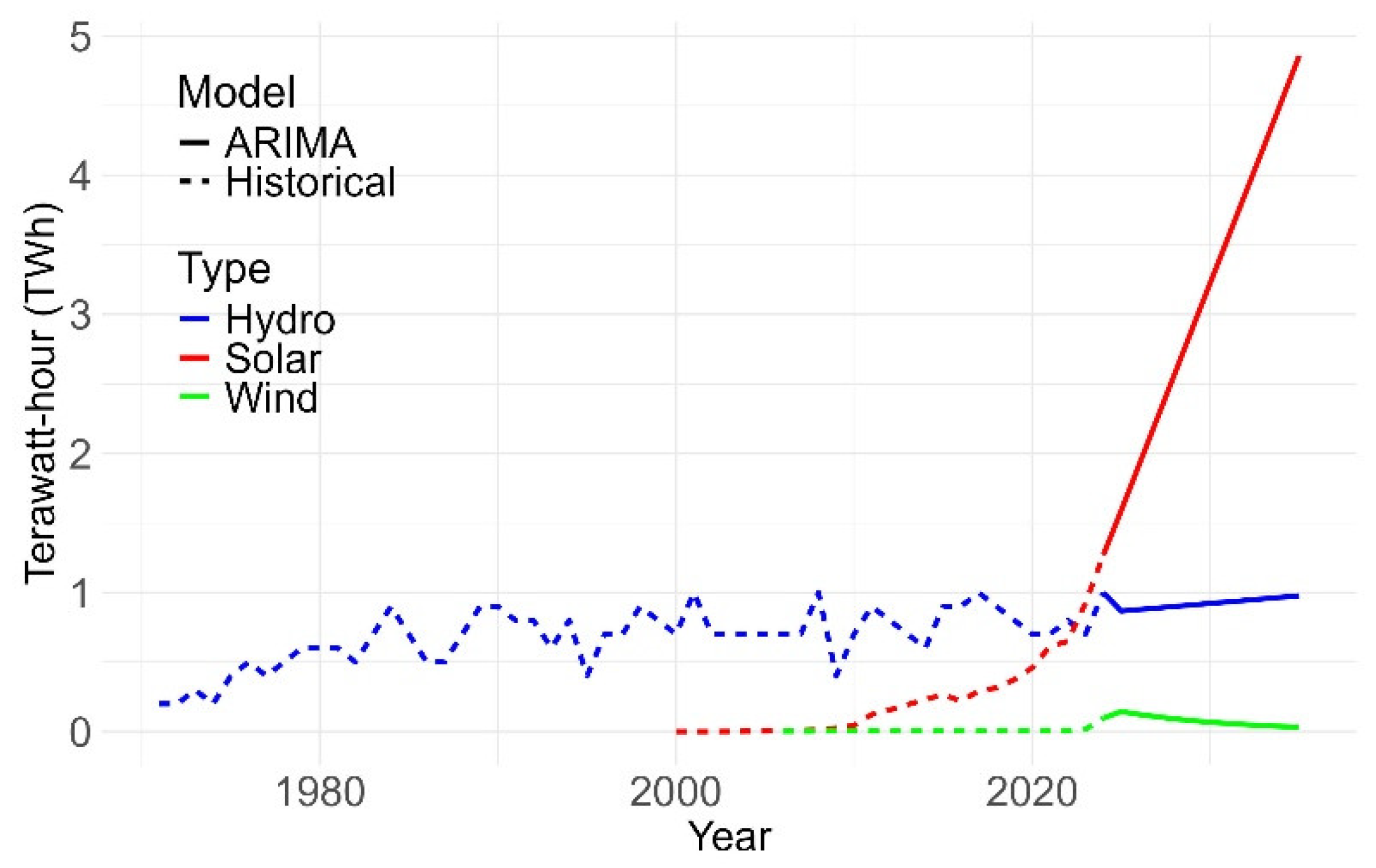

Canada, with its vast natural resources and commitment to environmental sustainability, is a global leader in renewable energy production. The country’s energy landscape is undergoing a significant transformation as it shifts from traditional fossil fuels to cleaner, more sustainable energy sources (NEB, 2019). The development and expansion of renewable energy technologies such as hydroelectricity, wind, solar, and biomass are central to Canada’s strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote economic growth, and ensure energy security (

Figure 15).

Canada’s renewable energy supply is dominated by hydroelectric power, which accounts for nearly 60 percent of the country’s total electricity generation (NRC, 2024c). The abundance of rivers and lakes, particularly in provinces like Quebec, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador, has made hydroelectric power a cornerstone of Canada’s energy strategy. Large-scale hydroelectric dams provide reliable, low-cost electricity and play a key role in reducing the nation’s carbon footprint.

Wind energy is the second-largest source of renewable electricity in Canada, making up about six percent of the country’s total generation (NRC, 2024c). Wind farms are primarily located in Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta, where government policies and favorable wind conditions support their development. The growth of wind power has been rapid over the past two decades, driven by technological advancements and increasing investments from both the public and private sectors.

Solar energy is growing steadily, while still a minor contributor to Canada’s electricity supply (

Figure 15). It is most prevalent in Ontario, which benefits from a combination of solar-friendly policies and relatively high radiation. As solar panel technology becomes more efficient and affordable, it is expected to play an increasingly important role, particularly in distributed energy systems and remote communities.

Biomass and bioenergy also contribute significantly to Canada’s renewable energy portfolio, particularly in regions with substantial forestry and agricultural industries. Biomass energy is derived from organic materials such as wood waste, agricultural residues, and landfill gas. It provides a valuable opportunity for waste reduction while generating heat and electricity.

Canada has committed to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (Navius, 2021). To achieve this target, federal and provincial governments have implemented a range of policies and incentives to promote renewable energy development. These include carbon pricing, renewable portfolio standards, feed-in tariffs, and investments in clean energy infrastructure.

Despite the progress, several challenges remain. Integrating variable renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, into the grid requires significant investment in energy storage, grid modernization, and transmission infrastructure (Bratt, 2021; Bennett et al., 2023). Moreover, energy projects must be developed in partnership with Indigenous communities, respecting land rights and ensuring mutual benefit.

Nevertheless, the transition to renewable energy presents numerous opportunities (Abdolmaleki et al., 2024). Canada can create thousands of green jobs, attract international investment, and develop new export markets for clean technologies. Moreover, renewable energy can provide a reliable and affordable power supply to remote and northern communities, many of which currently rely on expensive and polluting diesel generators.

Canada’s renewable energy supply is vital to its transition to a sustainable, low-carbon economy (Abdolmaleki et al., 2024). While hydro power remains the backbone of its clean energy system, the growth of wind, solar, and biomass signals a diversified and resilient energy future. With continued investment, supportive policies, and a commitment to innovation, Canada is well-positioned to lead the global shift toward renewable energy and climate resilience (Bennett et al., 2023).

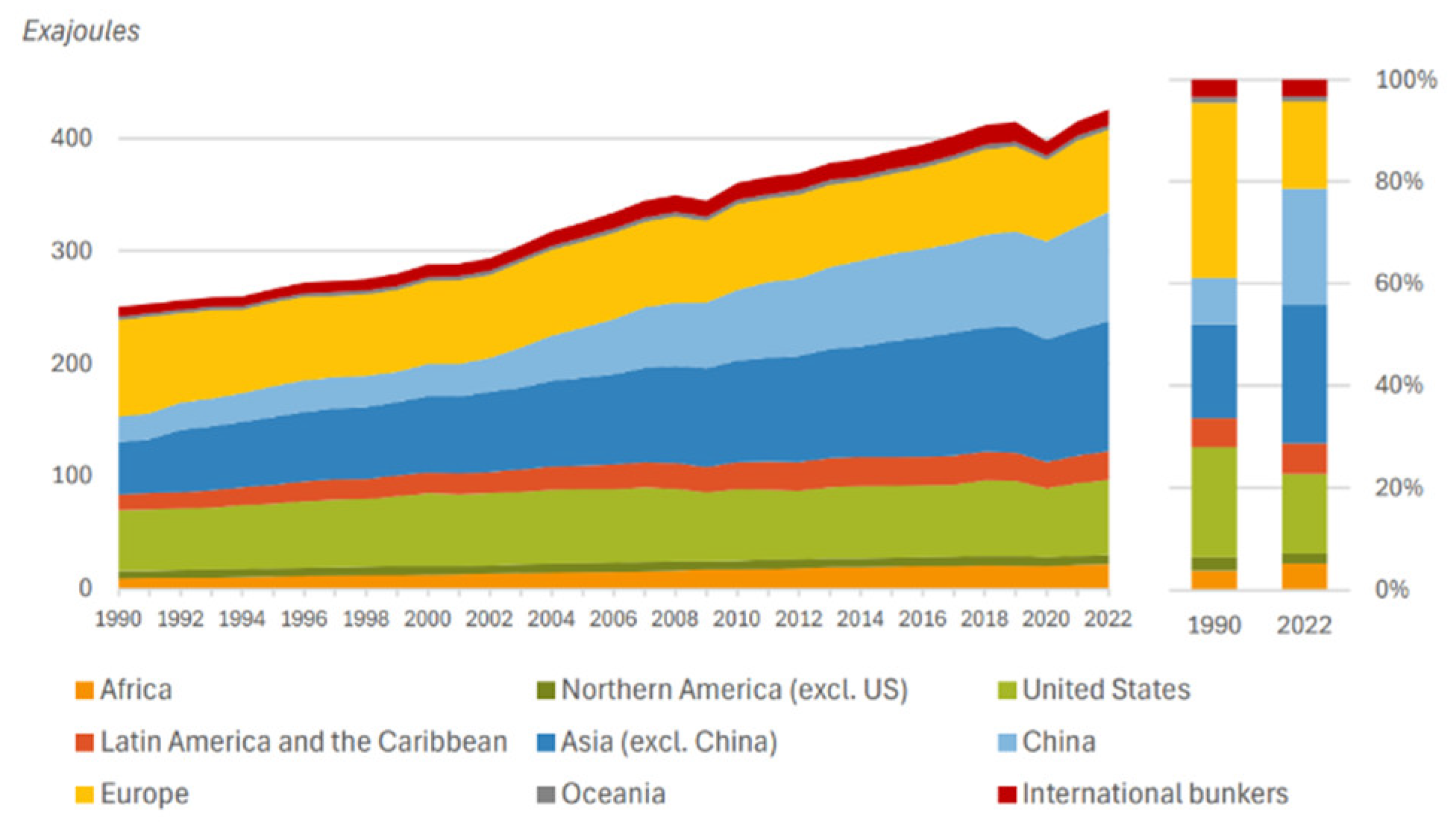

3.2. Energy Demand in Canada

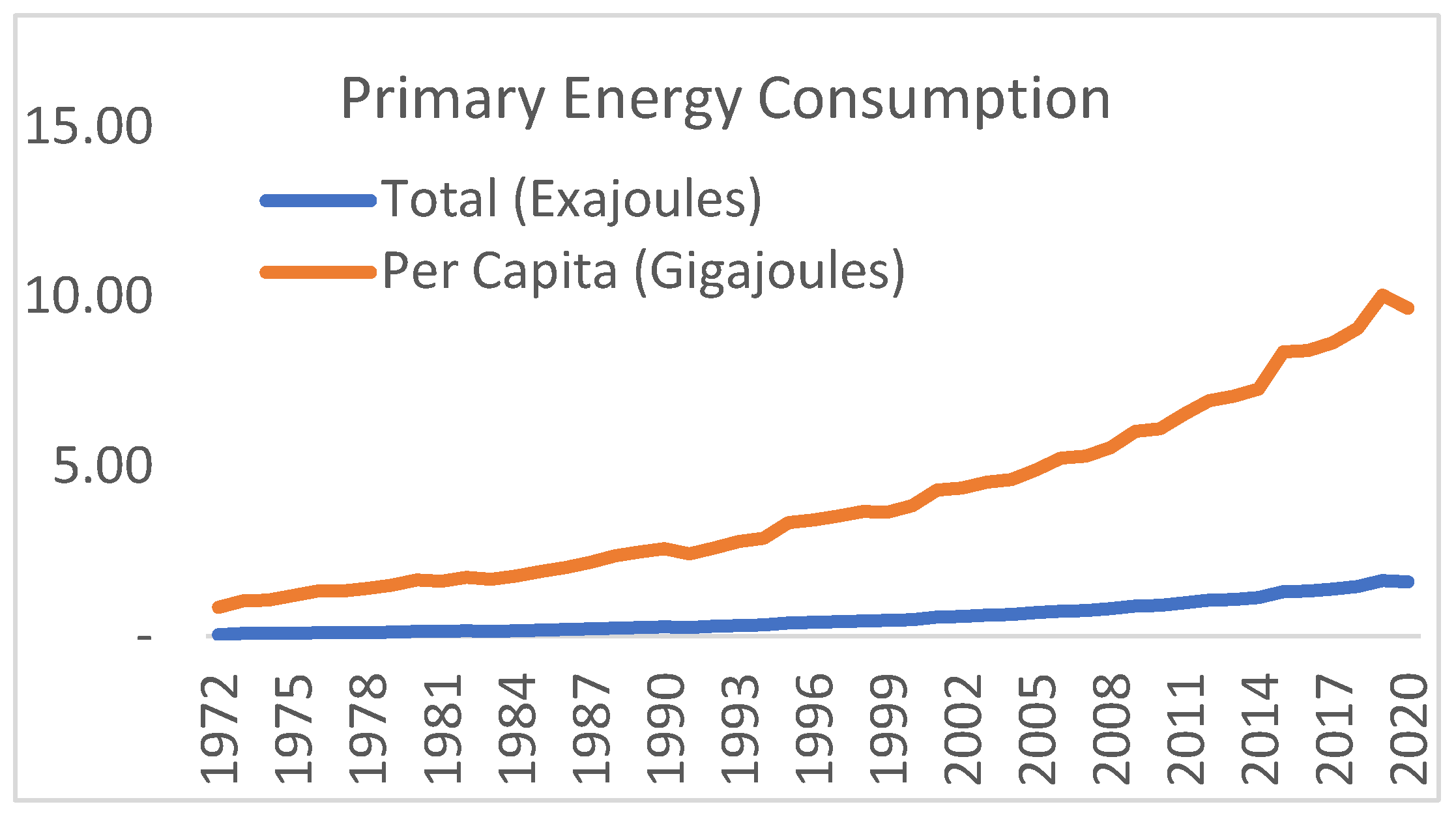

Canada, with its vast geography and diverse climate, is one of the world’s highest per-capita energy consumers (Energy Institute, 2025). Several factors, including economic growth, industrial activity, weather conditions, population trends, and technological advancements, impact energy demand in Canada. Understanding how and why Canadians consume energy is crucial for shaping effective policies on energy production, sustainability, and climate change.

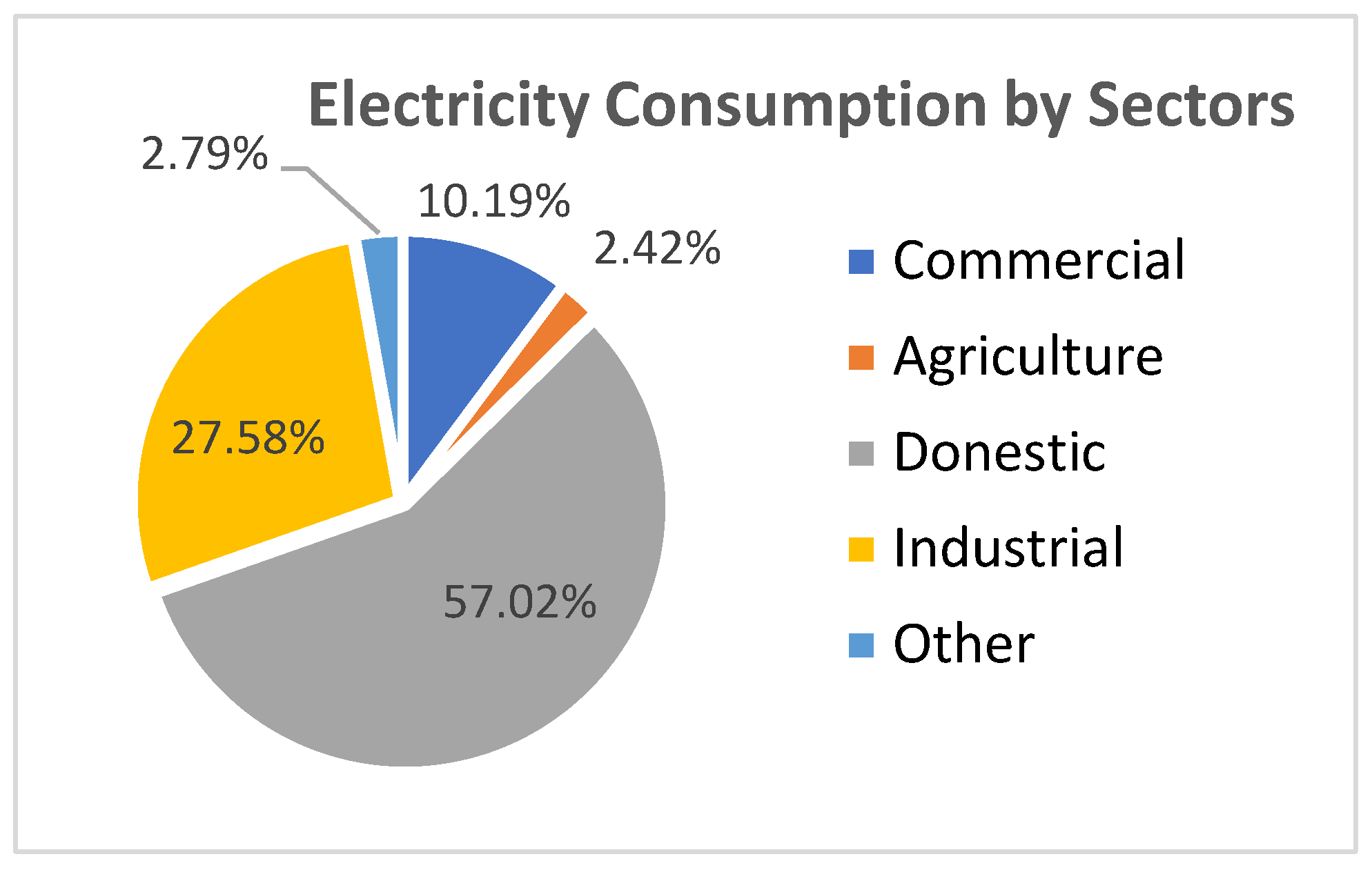

Canada’s total energy demand in 2020 was 11,059 petajoules, which can be divided among four major sectors: industrial, transportation, residential, and commercial/institutional (CER, 2023). The industrial sector is by far the largest consumer, accounting for nearly 50% of the country’s total energy use. This includes energy-intensive industries such as oil and gas extraction, mining, pulp and paper, and manufacturing. The transportation sector follows, consuming about 25 percent, largely in the form of gasoline and diesel fuels.

Table 3.

Canada’s energy demand by sector in 2020. [Source: CER, 2023. Canada’s Energy Future: Data appendix for end-use demand].

Table 3.

Canada’s energy demand by sector in 2020. [Source: CER, 2023. Canada’s Energy Future: Data appendix for end-use demand].

| Sector |

Percent |

| Industrial |

53 |

| Transportation |

20 |

| Residential |

14 |

| Commercial |

13 |

In the residential and commercial sectors, energy is primarily used for heating, specifically for space and water heating, due to Canada’s cold climate (NRC, 2012). Electricity, natural gas, and heating oil are the primary energy sources for these sectors. In recent years, electricity demand has remained relatively stable, while natural gas use has grown due to its affordability and efficiency.

Provinces vary in their reliance on fossil fuels. For example, Alberta and Saskatchewan are heavily dependent on oil and gas, whereas Quebec and British Columbia utilize more hydroelectricity. This regional variation shapes provincial policies and public attitudes toward energy development (CER, 2025).

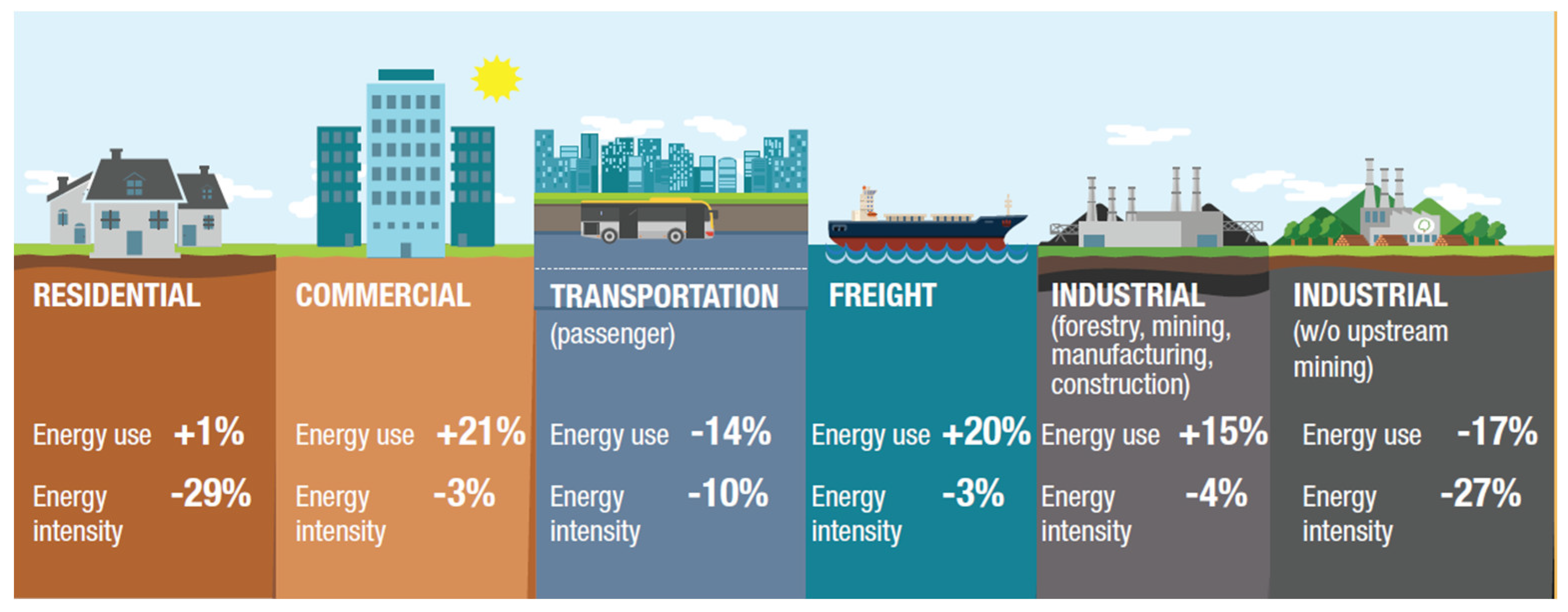

Over the past two decades, energy intensity (energy use per unit of GDP) in Canada has improved, reflecting gains in energy efficiency (NRC, 2024b). Federal and provincial programs promoting building retrofits, appliance standards, electric vehicle adoption, and industrial efficiency have contributed to slowing the growth of demand. However, population growth and economic development continue to exert upward pressure. Electrification of heating and transportation is expected to increase electricity demand in the coming decades.

Canada’s energy demand reflects both its natural resource wealth and its ambitions for a cleaner, more sustainable future. While the country faces challenges in aligning high energy consumption with climate targets, it also has the tools and opportunities to lead in the global energy transition. Although energy use has both positive and negative aspects, in all its sectors, energy intensity continues to improve (

Figure 16). Strategic investments in clean technology, infrastructure, and policy will be essential to meeting future energy needs while reducing environmental impact (Bennett et al., 2023).

3.2.1. Environmental Concerns and Conflicts

Canada, known for its vast natural landscapes and abundant resources, faces growing environmental concerns that reflect the tension between economic development and ecological protection. As a developed country with a resource-based economy, Canada faces complex environmental challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, Indigenous land rights, and industrial pollution. These challenges often give rise to conflicts between governments, industries, Indigenous communities, environmental groups, and the public. Nonetheless, Canada has the highest environmental performance index among G7 countries, indicating that it has the highest energy self-sufficiency, economic development, and environmental performance potential (Ehsanullah et al., 2021).

Canada is one of the world’s highest per-capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters, primarily due to its reliance on fossil fuels for energy and transportation. The oil sands in Alberta are a significant contributor to national emissions, and although the country has set ambitious targets (reaching net-zero emissions by 2050), progress remains slow. Increasing wildfire activity, extreme weather events, and melting permafrost are visible consequences of a warming climate across the country.

Canada has some of the world’s most extensive intact forests, but logging, particularly in provinces such as British Columbia and Quebec, has raised concerns about habitat loss and declining biodiversity. Old-growth forests, which are crucial for carbon storage and species protection, are being cut at unsustainable rates in certain regions, resulting in public protests and legal challenges (Sikkema et al., 2013).

Industrial activities, including mining and oil and gas extraction, have caused significant water contamination in certain areas (Spang et al., 2013). For example, tailings ponds from oil sands operations pose long-term risks to surrounding ecosystems and communities (ED 2013). Agricultural runoff and urban wastewater also contribute to water quality issues in lakes and rivers, including Lake Winnipeg and the Great Lakes (Glynn et al., 2002).

One of the most significant environmental conflicts in Canada involves the rights of Indigenous peoples to their traditional lands. Many natural resource projects—including pipelines, mining operations, and logging—occur on unceded or contested Indigenous territory. While some Indigenous communities support development for economic reasons, others oppose it due to environmental and cultural concerns (Kellner, 2025). Major pipeline projects such as the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) and Coastal GasLink have sparked nationwide debates (Hoberg, 2016; Kraushaar-Friesen and Busch, 2020). Proponents argue that these projects are essential for job creation and energy security, while opponents point to the risks of oil spills, increased emissions, and violations of Indigenous consent. Protests and legal actions have delayed several such projects, underlining the deep divisions they cause. Environmentalists and some First Nations oppose the destruction of ancient forests, arguing that conservation should take priority over short-term economic gain. (Gunton et al., 2021).

Balancing economic interests with ecological sustainability is no easy task, but it is essential for Canada’s long-term health and global climate commitments. Canada’s environmental concerns and conflicts reflect the country’s complex relationship with its natural environment. While it benefits from immense ecological wealth, it also faces significant pressures from development, climate change, and political divisions. Addressing these challenges requires collaboration across sectors and a commitment to justice, sustainability, and respect for nature, as well as the rights of Indigenous peoples.

3.3. Significance of Transition to Renewables

Transitioning to renewable energy is a goal for many government policies, but significant investment is required to ensure a smooth transition (Stringer and Joanis, 2022). According to Stringer and Joanis (2022), previous research papers have shown that the transition is possible at a national scale for Canada, but may not be equally feasible for each province independently. One case study examines the transition to renewable energy sources in Saskatchewan, focusing on a framework known as strategic environmental assessment (SEA) (Nwanekezie et al., 2022). This approach is used to explore the risks, capacities, and challenges that exist in certain institutions and governance; there are opportunities to determine not only the energy security concerns but also implement distributed generation and address the economic impact that may occur when transitioning away from a fossil-fueled run economy (Nwanekezie et al., 2022). Results have shown that there needs to be clear transition goals and objectives in place, along with strategies and tools to implement these goals, and, most importantly, a complete commitment to these objectives (Nwanekezie et al., 2022). They further state that there needs to be clarity and responsibility in place to ensure proper implementation and manage complexity when creating a new assessment for transition-based SEA.

Climate change, specifically CO2 emissions, is a significant global concern, as it impacts humans, resources, and critical environmental systems (Hussain et al., 2025). Global leaders are implementing various energy policies to reduce emissions and promote economic development while ensuring environmental sustainability (Hussain et al., 2025). Canada is a country that heavily relies on grey energy sources such as fossil fuels (Onyinyechukwu et al., 2024). Canada produces 17.7 million tons of carbon emissions, ranking 34th in environmental performance (Hussain et al., 2025). In fact, as of 2020, Canada’s electric power system is responsible for nine percent of Canada’s Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, of which 53 percent comes from Alberta alone (Miri and McPherson, 2024).

Canada, a nation with abundant fossil fuel reserves, faces a critical juncture regarding its energy sector, mainly due to its commitment to achieving net-zero emissions across the economy by 2050 (NRC, 2025). While currently a leading producer of hydropower, diversifying its energy mix beyond non-renewable sources is essential. The country’s energy supply is dominated by non-renewable sources, with fossil fuels accounting for 75 percent of total primary energy production in 2022 (NRC, 2024c). However, the adverse environmental impacts of fossil fuel combustion, including greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, pose a significant threat to Canada’s efforts to mitigate climate change and meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022) has emphasized the need for a rapid transition to renewable energy sources to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Canada has substantial renewable energy potential, with the Canadian Renewable Energy Association (2022) estimating that the country could generate up to 64 percent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2050. Hydroelectricity already accounts for 60 percent of Canada’s electricity generation, while other renewables contribute only 6.2 percent (Canada Energy Regulator, 2021). Transitioning to renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, offers a compelling solution. These resources are abundant in Canada, with wind and solar capacity experiencing significant growth (NEB, 2019; NRC, 2024a). By embracing this transition to renewables, Canada can enhance its energy security, mitigate the impacts of climate change, and unlock new economic opportunities associated with renewable energy technologies.

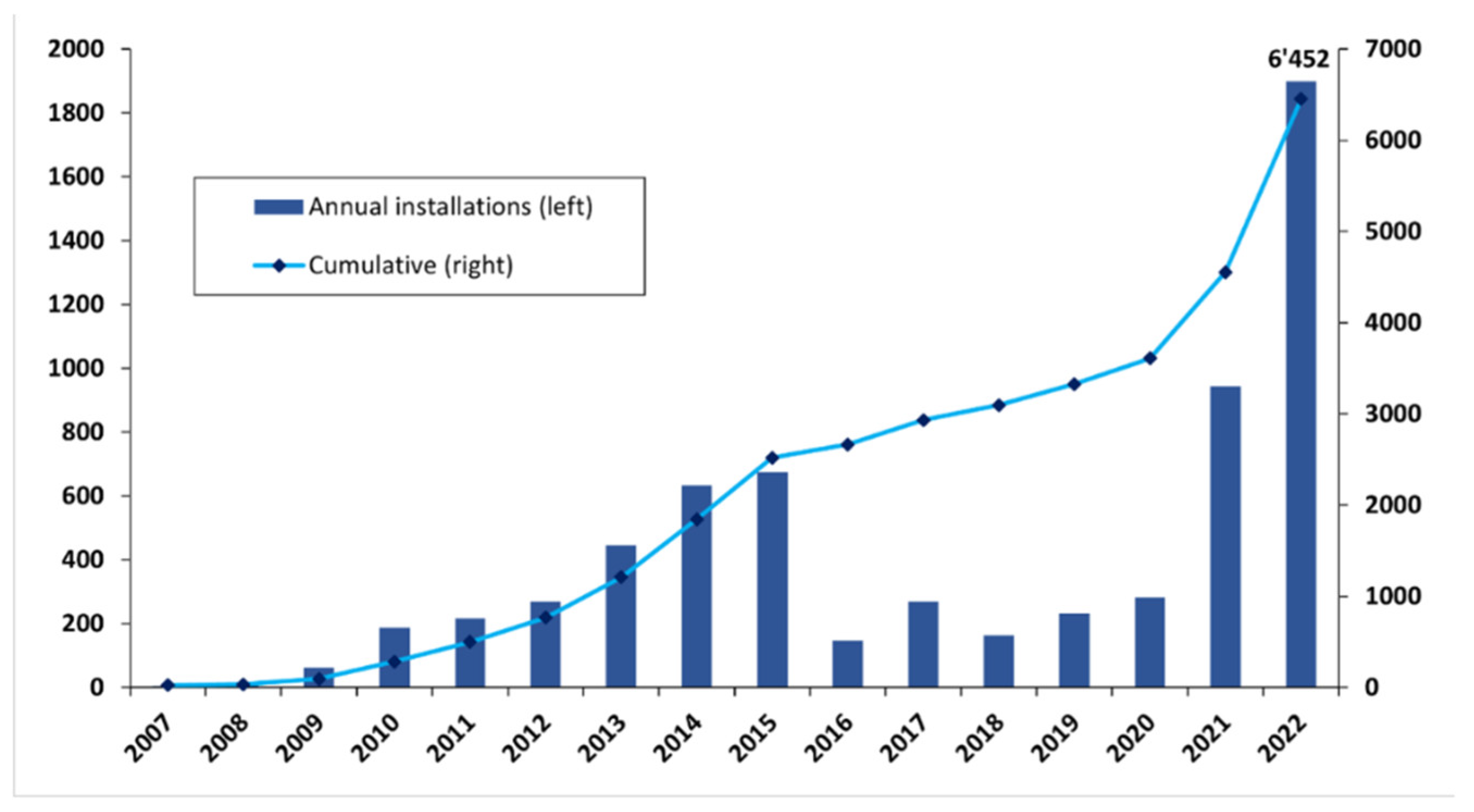

3.3.1. Solar Energy

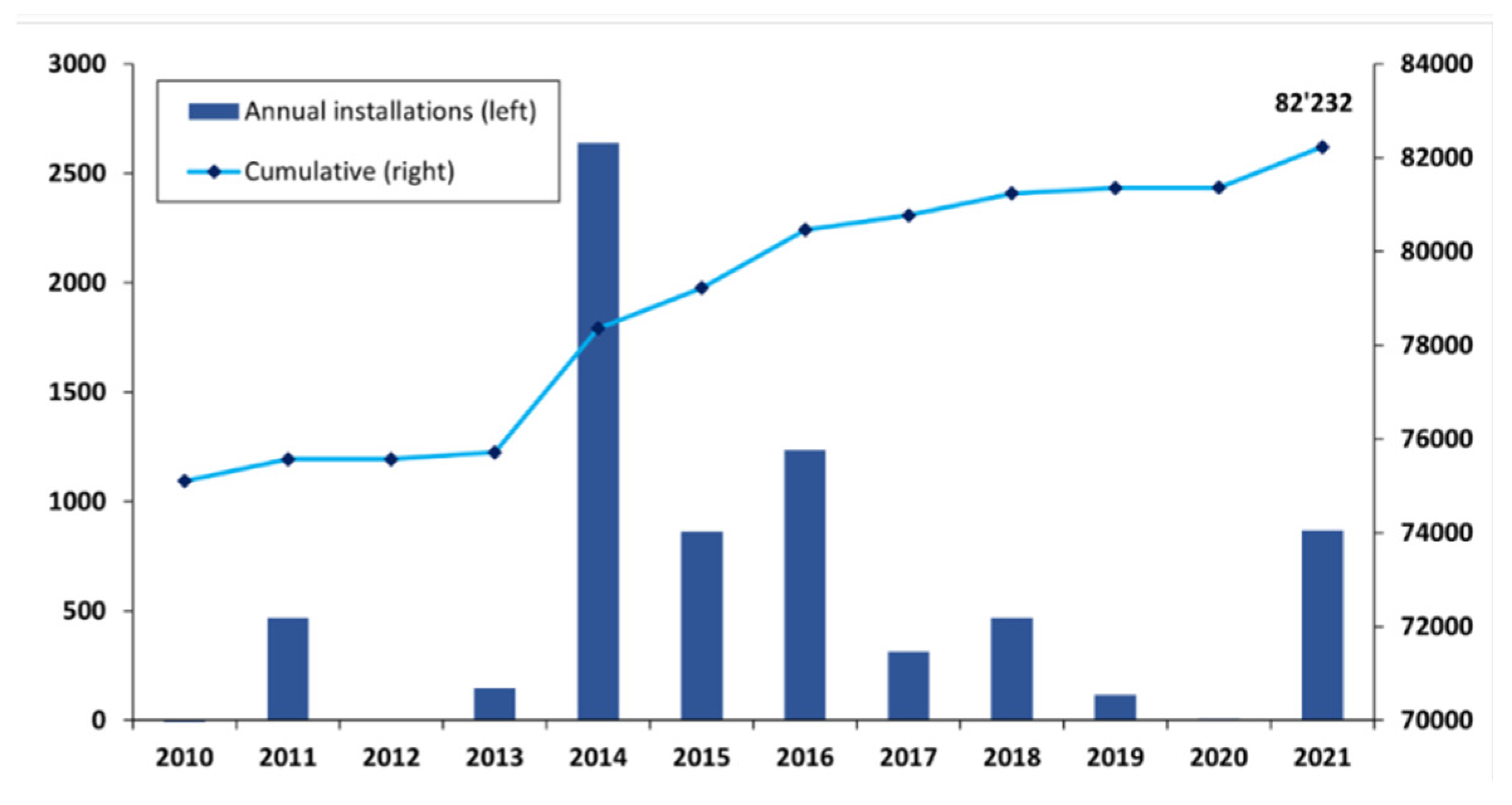

Canada, known for its vast landscapes and diverse energy resources, is increasingly turning to renewable energy to meet its environmental and economic goals. Among these renewables, solar energy is gaining momentum as a clean, sustainable, and accessible source of power (NRC, 2025). Solar energy installations in Canada continued to increase until 2015, after which they slowed down, but reached a peak in 2021 (

Figure 17). From 2023 to 2024, solar energy production in Canada increased by 8.2 percent (Energy Institute, 2025).

Although Canada is not the sunniest country in the world, its advancing technology, declining costs, and growing climate awareness have positioned solar energy as a key player in the country’s energy transition, and production is expected to continue to increase (Gaucher-Loksts and Pellan, 2024). British Columbia aspires to have net-zero energy by 2032 (Shirinbakhsh and Harvey, 2024). Canada has certain advantages when it comes to solar energy, as it is not only abundant but also has a significant solar energy potential in most of the southern part of the country, as well as in the western part of Prince Edward Island (Karayel and Dincer, 2024b). There are over 43,000 solar photovoltaic systems across Canada that supply electricity to commercial, residential, and industrial rooftop areas (Karayel and Dincer, 2024b).

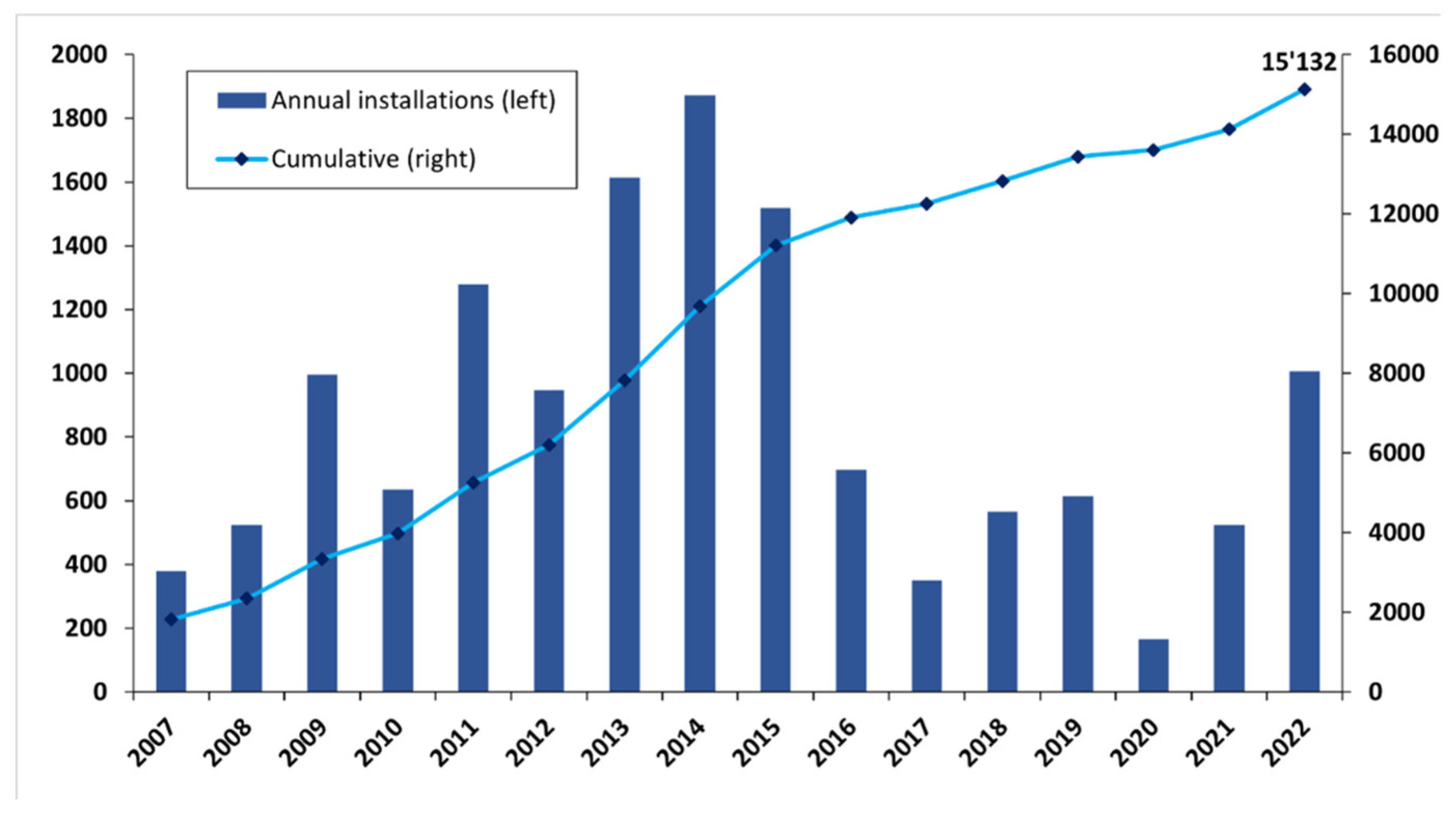

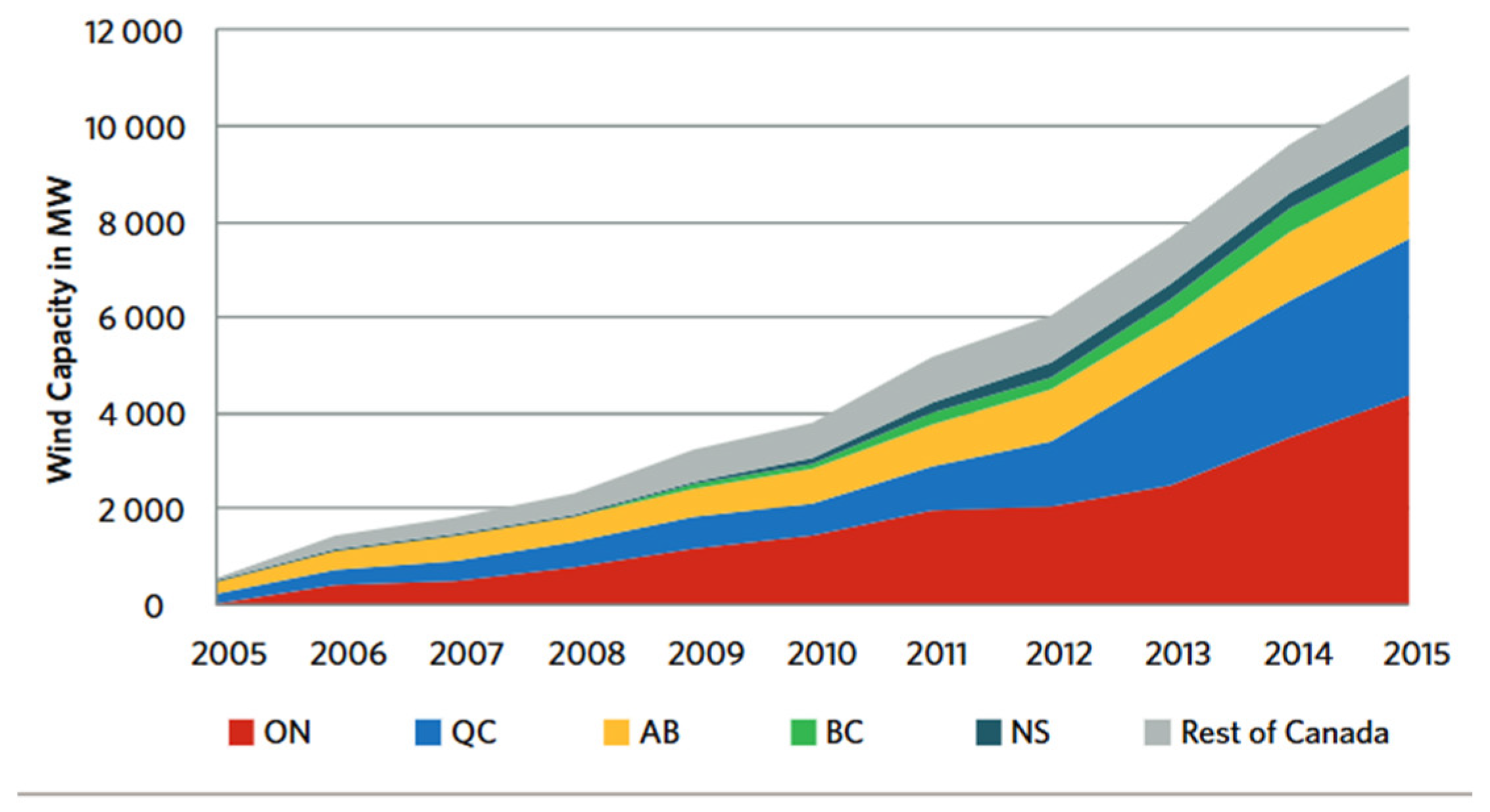

3.3.2. Wind Energy

Wind energy is one of the fastest-growing sources of renewable electricity in Canada. With its vast open landscapes and strong wind resources, Canada is well-positioned to harness the power of the wind to generate clean, reliable energy. As global efforts to reduce carbon emissions intensify, wind energy is playing an increasingly important role in helping Canada transition to a low-carbon economy. Although annual installations vary, the cumulative total wind energy capacity continues to increase (

Figure 18). From 2023 to 2024, wind energy in Canada grew at a rate of 8.2 percent (Energy Institute, 2025).

Canada, being the second-largest country in the world, has a vast area with high wind energy production potential. Wind power systems are generally viable where annual average wind velocity exceeds 15 km/h (Das et al, 2014; Savelle, 2025). Despite considerable seasonal variations in wind and temperature, particularly extreme winter temperatures, adequate wind resources exist throughout Canada for wind power generation. Socio-economic aspects play a significant role in implementing the wind energy production projects. The market size, remoteness, transmission facilities, grid connection, local acceptance, installation and maintenance expenses, and energy storage capabilities are some of the key challenges. An environmentally friendly energy production does not necessarily become acceptable to everyone (Walker et al, 2016).

In Canada, wind energy has grown rapidly since 2008, accounting for approximately five percent of the country’s overall electrical energy generation (CER, 2019; NEB, 2021). Canada, being the second-largest country in the world, has a vast landmass and varying capacities among its geographical regions. Ontario and Quebec together produce over 66 percent of Canada’s total wind energy (

Figure 19). However, one small province, Prince Edward Island, produces over 95 percent of its electricity from wind.

In Canada, potential exists for a continuous increase in wind electricity generation. Canada’s geography, especially the Prairies and coastal regions, offers consistent and powerful wind currents that are ideal for large-scale wind farms (IEA, 2022). The four principal advantages of wind energy are: clean and renewable, abundant and sustainable, low operating costs, job creation, and economic growth. However, despite these advantages, wind energy has several issues, including intermittency, impact on wildfires and landscapes, community composition, and competition with hydroelectricity.

Despite these organizations, Canada has difficulty adopting wind energy. The three most common ones are: (1) intermittency and storage of wind electricity, (2) impacts on wildlife and landscapes, (3) community opposition, and (4) transmission infrastructure (Sanij et al, 2022). The federal government has played a significant role in promoting wind energy through various programs. Examples include feed-in tariffs and renewable energy targets in Ontario, carbon pricing across Canada, green infrastructure funding, and Indigenous partnerships.

The future of wind energy in Canada is promising. With global and domestic pressure to reduce emissions, wind power is expected to expand rapidly. According to the Canadian Renewable Energy Association (CREA, 2021), wind and solar together could make up 30–35 percent of Canada’s electricity by 2050.

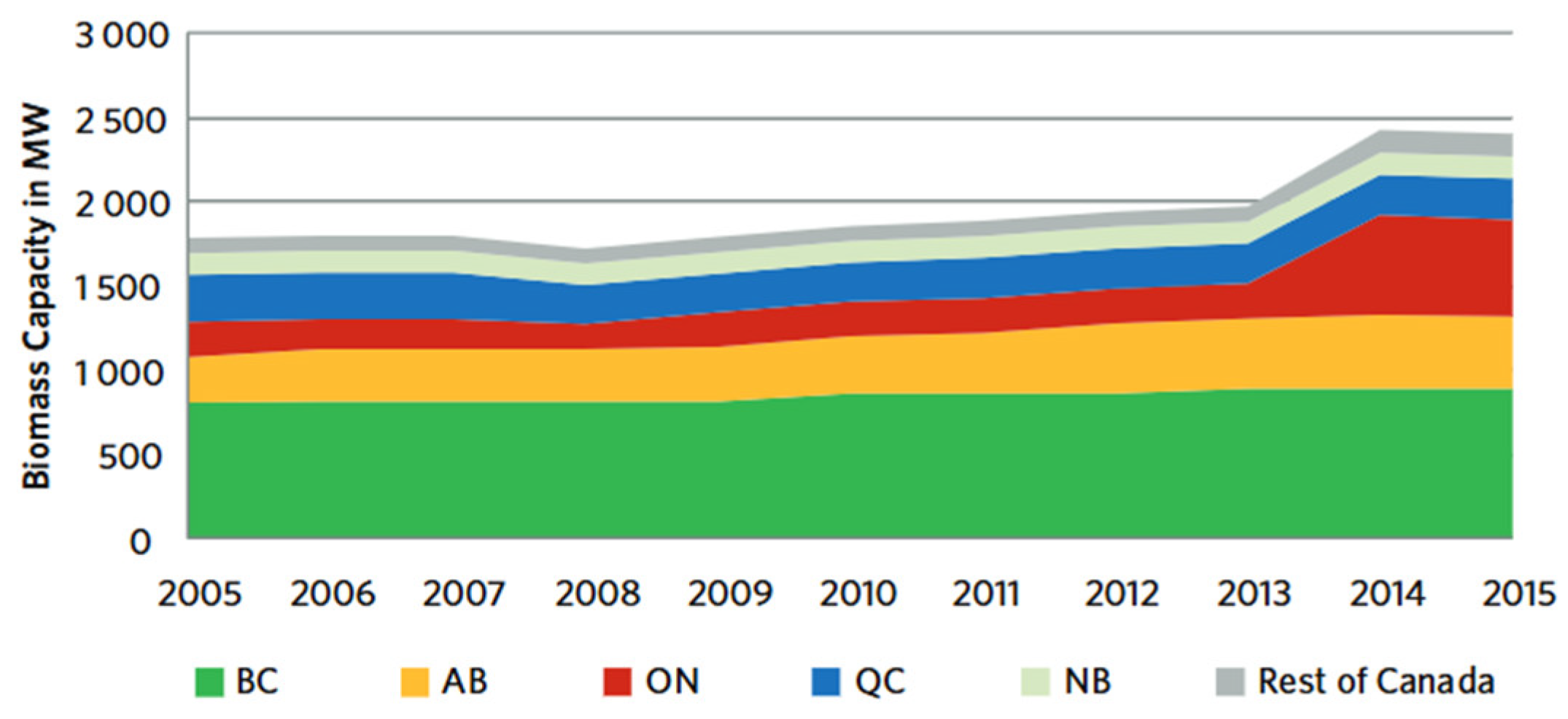

3.3.3. Biomass

Biomass energy refers to the use of organic matter, such as wood chips, pellets, crop waste, and even animal manure, to generate heat, electricity, or transportation fuels. Biomass can be burned directly, converted into biogas, or processed into liquid biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel. Biomass energy is a vital yet often underappreciated component of Canada’s renewable energy portfolio. Derived from organic materials such as wood, agricultural residues, and municipal waste, biomass provides a sustainable means of producing electricity, heat, and biofuels. In a country as rich in forests and agricultural land as Canada, biomass presents a unique opportunity to support rural economies, reduce waste, and contribute to national climate goals (NRC, 2025a).

Unlike fossil fuels, biomass is renewable, as new crops or forests can regrow to replace what is used. While burning biomass releases carbon dioxide, the emissions are generally offset by the carbon absorbed by the plants during their growth, making the process carbon-neutral when sustainably managed.

Canada is one of the world’s leading producers and consumers of biomass energy, largely due to its extensive forest sector (

Figure 20). Canada is investing in advanced biofuels and biochemical technologies to produce cleaner alternatives for aviation, shipping, and heavy industries. It is expected to remain a crucial component of Canada’s clean energy strategy, particularly in rural, remote, and industrial setting

s. With improved efficiency, emissions controls, and sustainable sourcing, biomass can complement other renewables like wind, solar, and hydro.

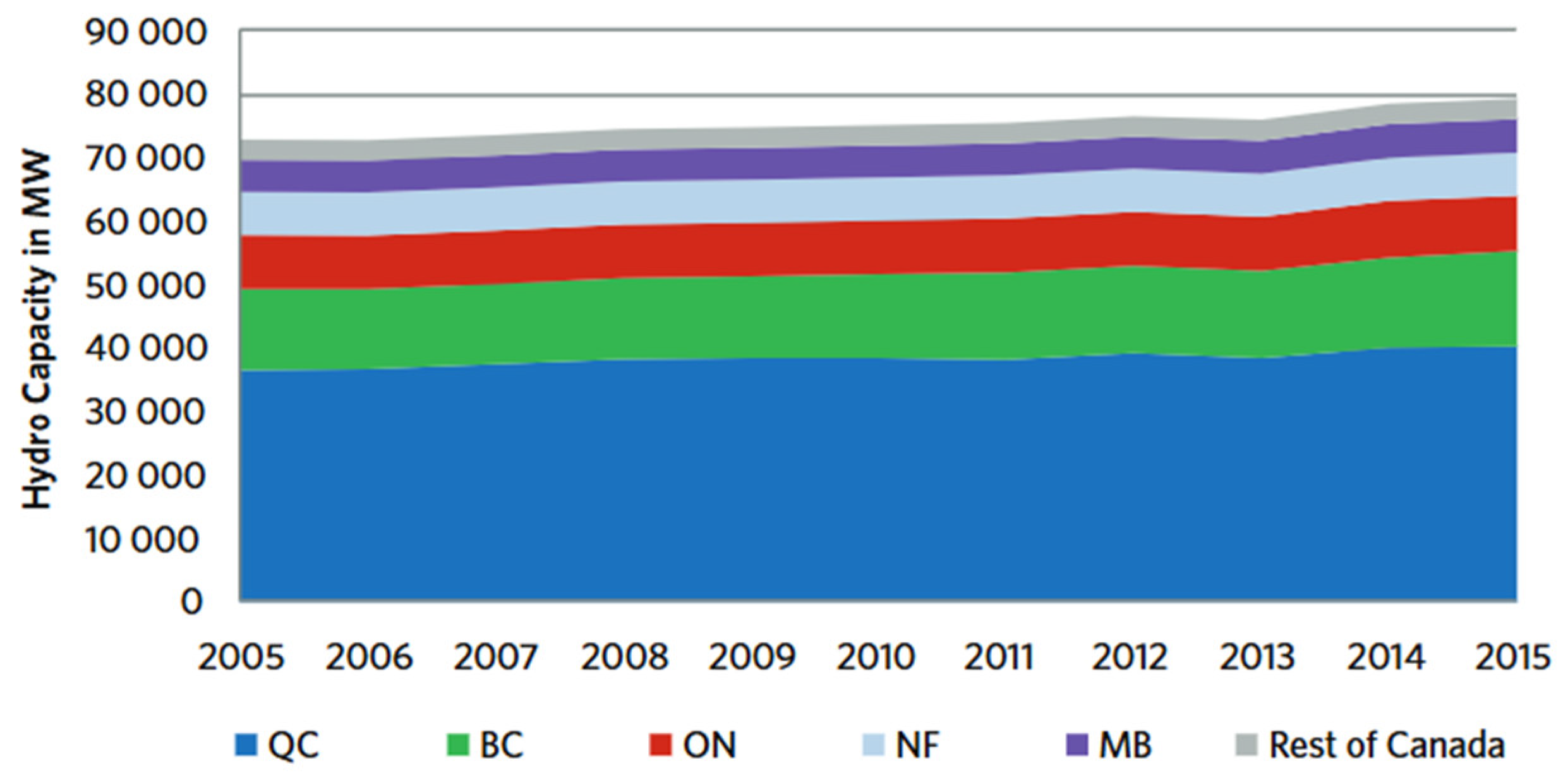

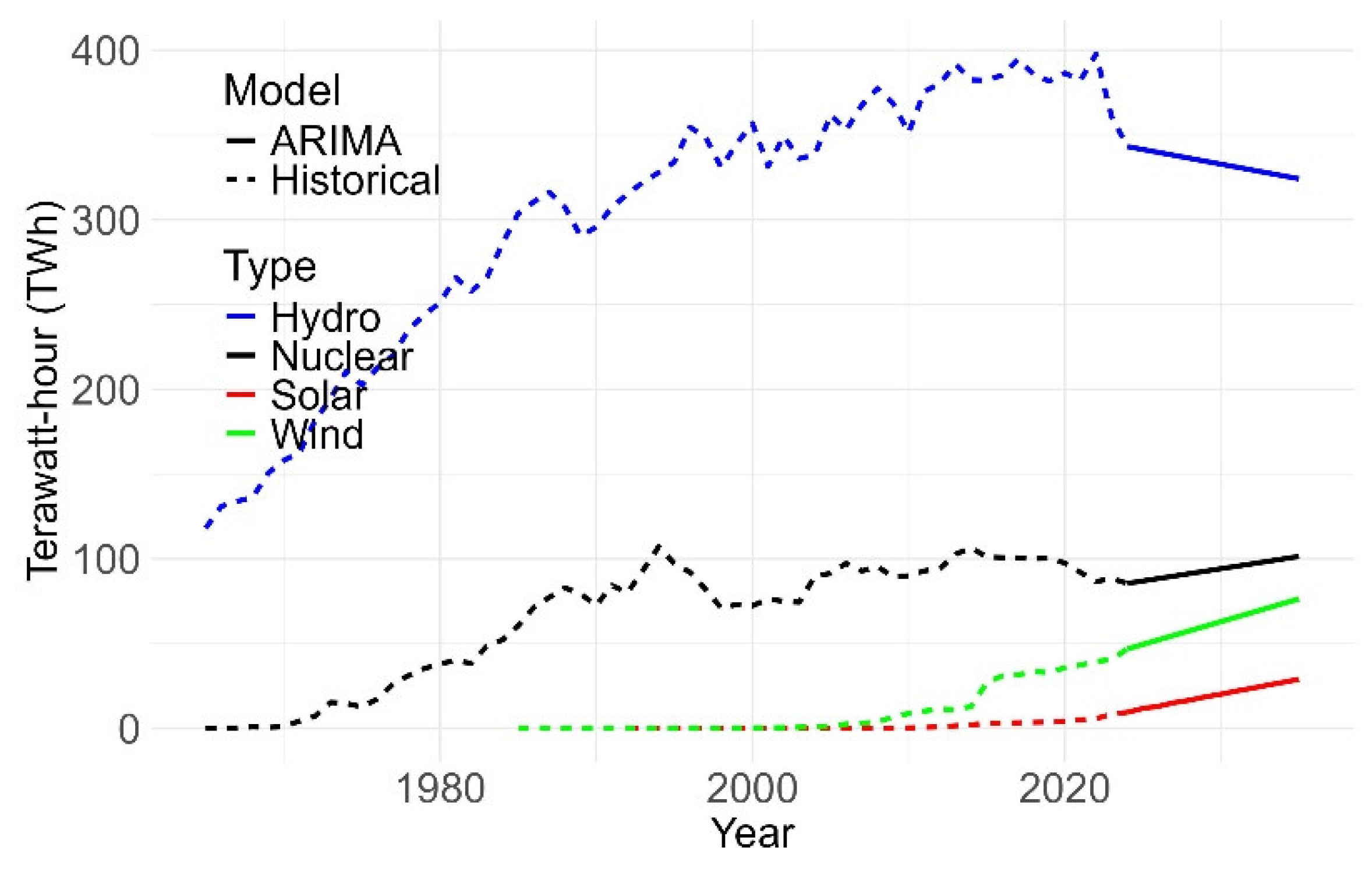

3.3.4. Hydro

Hydroelectricity, or hydro energy, is the backbone of Canada’s electricity system. Thanks to its abundant rivers, lakes, and elevation changes, Canada has become one of the world’s largest producers of hydroelectric power (

Table 1). As a clean, renewable, and reliable energy source, hydro energy plays a key role in helping Canada reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition to a sustainable energy future. Canada is the second-largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world, after China. As of 2024, over 60 percent of Canada’s electricity comes from hydro power, making it the dominant source of renewable energy in the country (NRC, 2025). Among Canadian provinces, Quebec and British Columbia are the homes of massive hydropower. Manitoba, Newfoundland, and Labrador also rely heavily on hydro. Nonetheless, the production capacity remains relatively stable, with a moderate increase (

Figure 21 and

Figure 22).

Canada’s hydroelectricity projects are aging and face challenges from various fronts, including ecosystem disruptions, indigenous land claims, greenhouse gas emissions, and high maintenance costs. Nonetheless, hydro will remain a cornerstone of Canada’s energy system, but future projects are expected to focus more on community partnerships, environmental sustainability, and respect for Indigenous rights.

Hydro energy has powered Canada for over a century and remains central to its clean energy leadership. With its ability to provide large-scale, low-emission, and reliable electricity, hydro plays a key role in meeting national climate goals. However, to maintain public trust and sustainability, future hydro development must be balanced with ecological protection and meaningful Indigenous engagement. By doing so, Canada can continue to lead the world in clean, responsible energy production.

3.3.5. Geothermal

In Canada, geothermal energy remains underdeveloped, despite the country’s vast geothermal resources. As Canada seeks to reduce emissions and diversify its renewable energy mix, geothermal energy presents a promising, though challenging, opportunity [Joseph, 1991; Wang et al, 2024].

Geothermal energy is derived from the natural heat of the Earth’s interior. It can be accessed in several ways: (1) Shallow geothermal systems (also called ground-source heat pumps) for residential and commercial heating and cooling; (2) Deep geothermal systems for producing electricity by using hot water or steam to drive turbines and (3) Direct-use applications, such as heating greenhouses, fish farms, or industrial facilities [Grasby et al., 2012; Wang et al 2024]. Geothermal energy is a reliable, renewable source that has a very low environmental footprint when developed responsibly. Canada has significant geothermal potential—especially in British Columbia, Alberta, Yukon, and Saskatchewan (Majorowicz and Grasby, 2013; Leitcha et al, 2019). Increased interest in low-carbon heating systems, as part of Canada’s push for net-zero emissions by 2050, could further boost demand for geothermal heating in urban and suburban areas (Wang et al, 2024).

Geothermal energy in Canada is still in its early stages, but its future looks promising (Huang et al., 2024). As technology improves, costs decrease, and climate policies become more ambitious, geothermal is expected to play a supporting role in Canada’s clean energy transition. Particularly in provinces like Saskatchewan and Alberta, geothermal energy can help repurpose oil and gas expertise, create new jobs, and decarbonize heat and electricity (Leitcha et al., 2019).

Though underutilized, geothermal energy represents a robust and sustainable resource beneath Canada’s surface. With the right mix of investment, research, and policy support, geothermal could help Canada achieve its clean energy goals while providing reliable power and heating—especially in remote and resource-rich regions. Unlocking this potential will require collaboration between governments, Indigenous communities, industry, and researchers.

3.3.6. Tidal Energy

As the world moves toward cleaner energy solutions, tidal energy—the power generated from the natural rise and fall of ocean tides—offers a predictable and sustainable source of renewable electricity. With its vast coastlines and strong tidal currents, Canada is uniquely positioned to become a global leader in tidal power (Cornett, 2006; Fisch, 2016a, b; MRC, 2018). While the technology is still emerging, it holds great promise for contributing to Canada’s clean energy goals, especially in coastal and remote communities.

Tidal energy harnesses the gravitational forces of the moon and sun, which create the daily movement of tides in oceans and bays. This energy can be captured using several technologies, including (1) Tidal stream turbines – Underwater turbines that operate like underwater windmills in fast-moving tidal currents, (2) Tidal barrages – Dams built across tidal estuaries that trap water at high tide and release it through turbines, and (3) Tidal lagoons – Man-made enclosures that work similarly to barrages, but with potentially less environmental disruption (Kempener and Neumann, 2014).

Unlike wind and solar, tidal energy is highly predictable, making it a reliable option for enhancing grid stability and supporting long-term planning. Canada is home to one of the most powerful tidal zones in the world: the Bay of Fundy, located between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. This bay experiences tidal ranges of up to 16 metres—the highest on Earth (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2024). Tidal energy has not yet been widely commercialized in Canada, and the number of operational projects remains relatively small (Cornett, 2006).

Tidal energy in Canada is still in the early stages of commercial development, but its long-term potential is substantial. As technology improves and costs fall, tidal power could play a complementary role alongside wind, solar, and hydro in Canada’s renewable energy mix. For coastal provinces like Nova Scotia and British Columbia, tidal energy offers a unique opportunity to generate clean power while supporting local economies and Indigenous energy sovereignty (MRC, 2018).

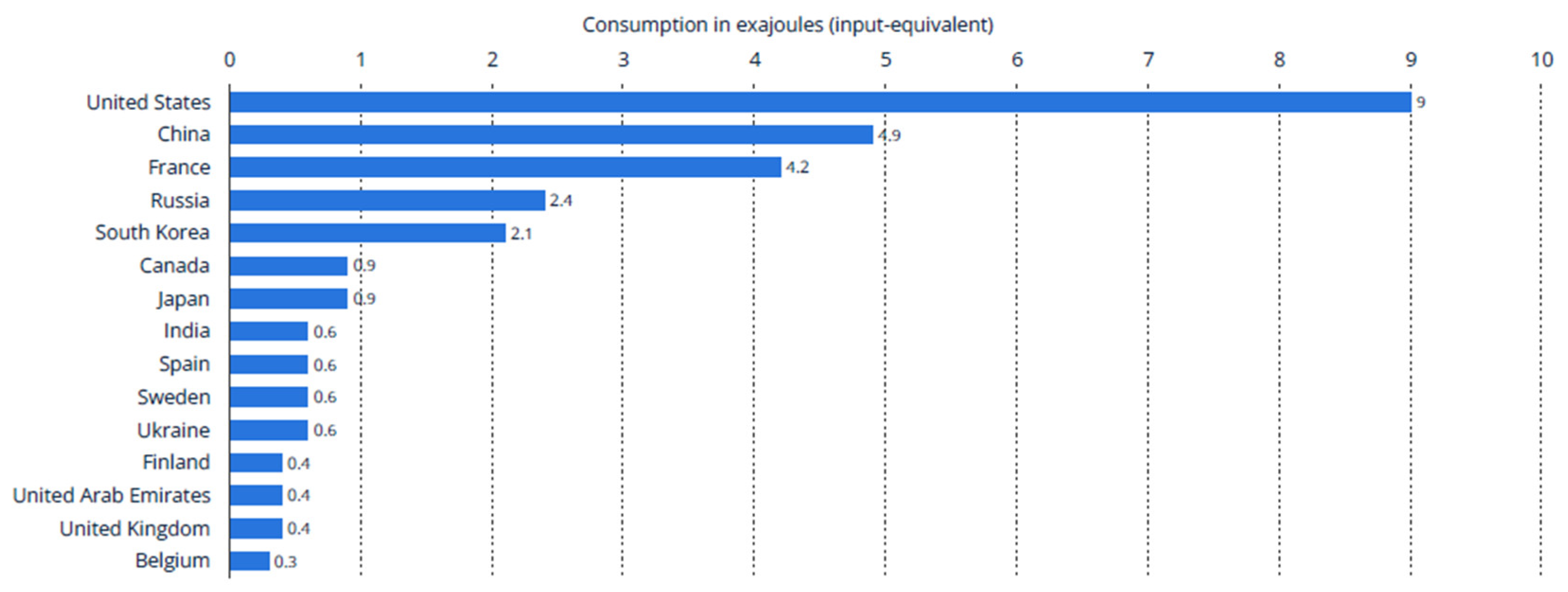

3.3.7. Nuclear Energy

Nuclear energy has been a cornerstone of Canada’s electricity system for over half a century. As the country seeks to decarbonize its energy grid and meet its climate targets, nuclear power, particularly with the emergence of new technologies like small modular reactors (SMRs), is receiving renewed attention (NEB, 2018). With a strong domestic industry, an established safety record, and significant uranium resources, Canada is the sixth-largest producer of nuclear energy, accounting for approximately four percent of the world’s total nuclear energy production (NEB, 2018). The largest nuclear energy-producing and consuming countries are the USA, China, France, Russia, and South Korea (

Figure 23).

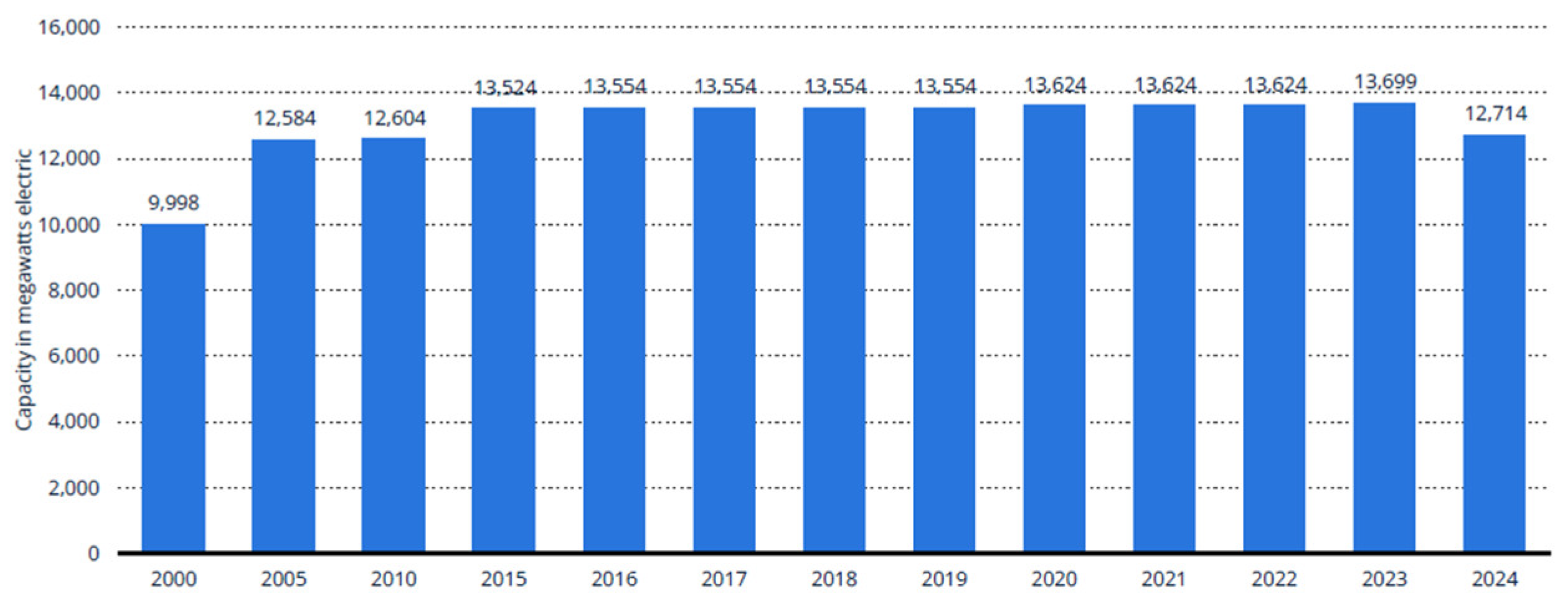

Canada began developing nuclear technology in the 1940s and launched its first commercial nuclear power station in the early 1970s (Atomic Energy Canada Limited, 1997; Brooks, 2002). Today, nuclear energy accounts for approximately 15 percent of Canada’s electricity, with over 60 percent of this energy used in Ontario, where it serves as a primary power source. Canada operates 19 nuclear reactors, primarily in Ontario, with additional reactors located in New Brunswick and Quebec (CNA, 2020). It is the birthplace of the CANDU reactor (CANada Deuterium Uranium), a unique technology that uses natural (unenriched) uranium and heavy water. Canada is also one of the world’s top producers and exporters of uranium, with major mining operations in Saskatchewan (Brooks, 2002; CNA 2020). Canada’s nuclear energy production has remained stable in the last two decades (

Figure 24).

Ontario and New Brunswick are the only two provinces in Canada that operate nuclear power plants. Nuclear generation accounted for 58 percent of Ontario’s total generated electricity in 2016, and 30 percent of the total in New Brunswick (NEB, 2018). In both provinces, it was the largest source of electricity generation. From 2005 to 2016, total nuclear generation in Canada increased by 10 percent. No new nuclear facilities were built during this time. Refurbishments and improvements at existing nuclear facilities in Ontario and New Brunswick were responsible for the increase. Similarly, a decrease in 2024 (

Figure 24) is due to maintenance.

Nuclear energy is a vital part of Canada’s clean energy strategy (Hervas and Noyahr, 2024). With its low-carbon footprint, reliable output, and potential for innovation through SMRs, nuclear power can help Canada meet its climate commitments while supporting economic growth. However, its future depends on addressing public concerns, managing waste responsibly, and ensuring the safe and cost-effective deployment. If implemented correctly, nuclear energy will continue to be a powerful and sustainable contributor to Canada’s energy future (Winfield, 2006; Wilde et al., 2018; Hervas and Noyahr, 2024).

3.4. Energy Policy in Canada

Canada’s energy policy framework represents a complex governance and public administration challenge, fundamentally shaped by two persistent tensions. First, there exists an ongoing competition between economic development tied to resource extraction and environmental protection, mandating rapid decarbonization. More specifically, it has vast fossil fuel reserves, with its economy heavily dependent on this sector. Simultaneously, it always positioned itself internationally as a proponent of ambitious climate commitments, from its early ratification of the Kyoto Protocol to its more recent obligations under the Paris Agreement to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 (Government of Canada, 2023).

Second, the distribution of energy authority is spread across multiple levels of government, requiring sophisticated coordination mechanisms between federal, provincial, territorial, and Indigenous authorities. This intricate constitutional division of powers creates systematic challenges for policy coordination, as energy-consuming provinces with larger populations can elect federal governments that favour consumers. In contrast, energy-producing provinces exercise constitutional authority over natural resources to resist such policies (Viens, 2022).

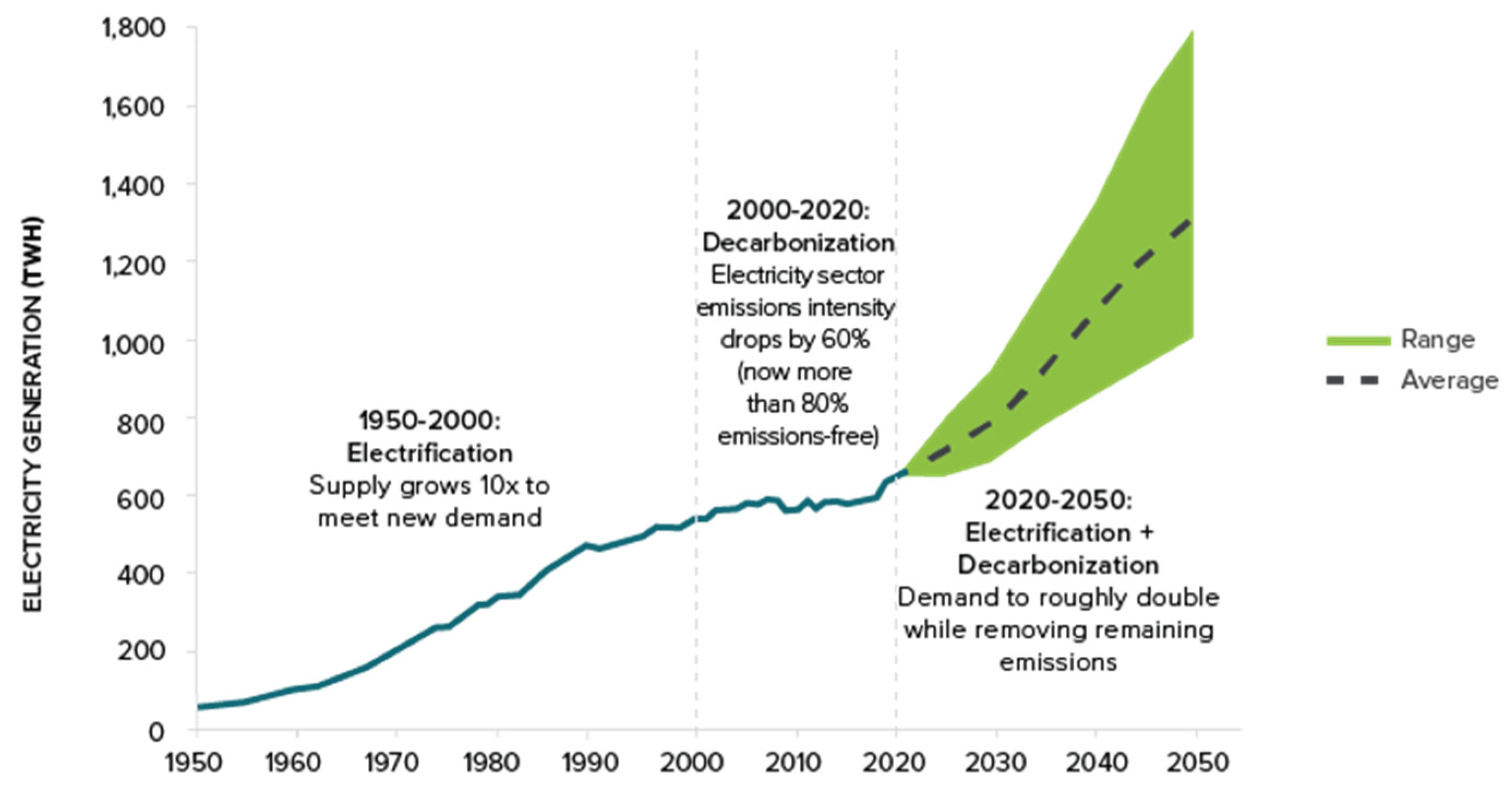

Recent policy developments provide crucial insights into these dynamics. The 2025 restructuring of federal carbon pricing, the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, and the finalization of the Clean Electricity Regulations demonstrate both the adaptive capacity and inherent limitations of Canada’s federal system in managing energy transition (Government of Canada, 2025a). These developments reveal a pattern of policy effectiveness that varies dramatically across economic sectors, with notable success in decarbonizing electricity contrasting sharply with persistent challenges in reducing emissions from oil and gas.

3.4.1. Energy-Environment Competition

Policy Architecture and Constitutional Framework:

Canada’s contemporary climate policy framework is anchored by the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act (2021), which establishes legally binding interim targets, including a 40–45 percent reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050. This legislation represents a significant institutional innovation, establishing independent oversight mechanisms through the Net-Zero Advisory Body and requiring comprehensive emissions reduction plans with mandatory progress reporting.

The federal carbon pricing system underwent fundamental restructuring in March 2025, representing a significant departure from the comprehensive approach implemented since 2019 (Government of Canada, 2025b). The government eliminated the consumer-facing fuel charge, effective April 1, 2025, by setting federal fuel charge rates to zero and removing the requirement for provinces and territories to maintain consumer-facing carbon pricing (Department of Finance Canada, 2025). Prior to this restructuring, the system had reached $80 per ton CO2 in 2024 and was scheduled to increase annually by $15 per ton, reaching $170 per ton by 2030 (Government of Canada, 2025c).

This policy shift reflects persistent implementation challenges that arise when federal environmental policies intersect with provincial constitutional authority and regional economic interests. The elimination of consumer-facing carbon pricing while maintaining industrial carbon pricing systems represents a strategic recalibration that prioritizes federal authority over large emitters while accommodating provincial resistance to broad-based carbon pricing.

The Two-Track Pattern of Policy Effectiveness

The empirical evidence reveals stark differences in policy effectiveness across economic sectors, with emissions outcomes varying dramatically based on structural characteristics. Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions data demonstrates a clear pattern of policy impact across the Canadian economy.

Table 4.

Sectoral Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Canada (Mt CO2eq).

Table 4.

Sectoral Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Canada (Mt CO2eq).

| Economic Sector |

2005 |

2023 |

Change 2005-2023 (%) |

| Oil and Gas |

194.5 |

208.0 |

+6.9% |

| Transportation |

156.2 |

156.6 |

+0.3% |

| Electricity |

115.9 |

48.8 |

-57.9% |

| heavy industry |

86.8 |

78.3 |

-9.8% |

| Buildings |

82.3 |

82.7 |

+0.5% |

| Total National |

759.0 |

694.0 |

-8.6% |

The electricity sector achieved remarkable decarbonization success, with emissions declining from 115.9 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2005 to 48.8 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2023, representing a decrease of nearly 58 percent. This transformation was primarily driven by Ontario’s provincially mandated phase-out of coal, which resulted in the elimination of coal-fired electricity generation between 2005 and 2014 (IIS, 2015). The success reflects the structural advantages of government intervention in sectors dominated by Crown corporations and regulated utilities, which are directly susceptible to government mandates.

Conversely, the oil and gas sectors present fundamentally different implementation challenges. Emissions from this sector increased from 194.5 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2005 to 208.0 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2023, representing a 6.9 percent increase despite the implementation of comprehensive federal climate policies. The transportation sector exhibited similar resistance to policy intervention, with emissions remaining relatively stable at approximately 157 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2023 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2025).

This differential effectiveness reflects distinct characteristics of economic sectors and their susceptibility to government intervention. Electricity systems, dominated by provincial utilities and Crown corporations, present clear regulatory pathways for government action. Oil and gas production, characterized by private ownership, global market integration, and significant regional economic dependence, presents far more complex implementation challenges that resist direct government control (Viens, 2022).

Renewable Energy Policy Implementation

Federal renewable energy policies have achieved substantial deployment outcomes, though implementation has varied significantly across technologies and regions. The Clean Technology Investment Tax Credit offers a 30 percent refundable tax credit for renewable technologies implemented until 2034, while the Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit provides additional support for generation projects that meet emission intensity thresholds of no greater than 65 tons of CO2 per gigawatt-hour (Natural Resource Canada, 2024).

Table 5.

Renewable Energy Capacity Growth in Canada.

Table 5.

Renewable Energy Capacity Growth in Canada.

| Technology |

2019 Capacity (GW) |

2014 Capacity (GW) |

Growth Rate (%) |

| Wind |

13.4 |

18.0 |

+34.3% |

| Solar (Utility-scale) |

2.1 |

4.0 |

+90.5% |

| Solar (On-site) |

0.5 |

1.0 |

+100.0% |

| Energy Storage |

0.11 |

0.33 |

+200.0% |

Provincial approaches to renewable energy policy implementation reveal significant variation in effectiveness. Quebec’s renewable energy auction system has achieved some of the lowest prices for wind and solar power in North America, demonstrating successful policy design that leverages competitive market mechanisms. Alberta’s Renewable Electricity Program facilitated significant wind and solar development through long-term contracts, though policy momentum has varied with changes in provincial government priorities (Patel and Parkins, 2023).

The Canada Infrastructure Bank’s commitment of over $3 billion to clean energy projects represents an innovative approach to addressing private sector investment gaps, though implementation has been slower than initially anticipated. This experience illustrates the broader challenges of translating federal policy intentions into operational outcomes within Canada’s complex institutional environment (IEA, 2020).

3.4.2. Interjurisdictional Conflict and Cooperation

Constitutional Constraints and Federal-Provincial Dynamics

Canada’s federal system presents fundamental implementation challenges for a coherent energy policy, stemming from the constitutional division of powers outlined in sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Provinces maintain constitutional jurisdiction over natural resources under section 92A, while the federal government holds authority over interprovincial trade, international commerce, and matters of national concern. This division creates overlapping jurisdictions and institutional friction, which significantly complicates policy implementation (Bratt, 2021).

The constitutional framework enables energy-consuming provinces with larger populations to elect federal governments that favor energy consumers. In contrast, energy-producing provinces can exercise constitutional authority over natural resources to resist federal policies that may constrain development. This structural dynamic creates persistent implementation challenges, as federal climate policies must navigate provincial resistance from jurisdictions whose economies heavily depend on fossil fuel production (Banks, 2018; Choudhury, 2019; Bratt, 2021).

Clean Electricity Regulations Implementation

The development and finalization of the Clean Electricity Regulations (CER) illustrate the complex negotiation processes required for implementing federal environmental policy within Canada’s federal system. Initially proposed to require electricity systems to achieve net-zero emissions by 2035 (Canada Gazette, 2024), these regulations illustrate the complexities of federal environmental policy implementation within Canada’s federal system. The regulations faced significant opposition from several provinces, particularly Saskatchewan and Alberta (Viens, 2022; Wang, 2025).

The final regulations, enacted in December 2024, represent substantial federal accommodation to provincial concerns (Canada Gazette, 2024). The emissions intensity limit was revised from the originally proposed 30 tons of CO2 per gigawatt-hour to 65 tons, with additional flexibility through offset credits. The timeline for achieving net-zero was extended from 2035 to 2050, with emission restrictions not taking effect until January 1, 2035 (Canada Gazette, 2024)

Alberta’s Electric System Operator concluded that the regulations pose significant risks to reliability and affordability, projecting $30 billion in additional costs and 35% higher wholesale electricity prices between 2035 and 2050. Saskatchewan has rejected the regulations as unconstitutional, while Alberta has announced its intention to launch a constitutional challenge (Schulz, 2024).

Indigenous Rights and Energy Development

Indigenous consultation requirements, established through Supreme Court decisions and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (2021), introduce additional layers of complexity in implementing energy projects (Government of Canada, 2021). The federal government’s commitment to free, prior, and informed consent has significantly empowered Indigenous communities to influence decisions related to energy development. Yet, implementation remains challenging due to complex governance structures and varying community perspectives. The Energy Council of Canada recognizes that the risks faced by Indigenous communities and individuals were underappreciated and emphasizes this to bring it to the public sphere (Energy Council of Canada, 2022).

International Constraints and Policy Implementation

Canada’s energy policy operates within international constraints that limit domestic policy flexibility and complicate implementation. However, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (CUSMA) does not include energy provisions that affect Canadian policy options, particularly the proportionality clause, which requires Canada to maintain energy export levels to the United States during supply shortages, which was previously present in NAFTA (Global Affairs Canada, 2019).

Cross-border electricity trade relationships with the United States create both opportunities and constraints for policy implementation. Quebec exports significant hydroelectric power to New England, while Manitoba exports to the US Midwest, requiring regulatory coordination between Canadian and American authorities. These relationships create interdependencies that affect domestic energy policy choices and limit unilateral Canadian action.

The completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion in May 2024 highlights ongoing federal support for fossil fuel infrastructure, despite climate commitments. The project, which cost over $34.2 billion and increased capacity from 300,000 to 890,000 barrels per day, represents the largest federal investment in energy infrastructure in decades (Government of Canada, 2024). This juxtaposition, namely federal financing of major hydrocarbon infrastructure alongside renewed commitments to net-zero, illustrates the deep structural contradictions that continue to define Canada’s energy policy landscape.

Together, the evidence across

Section 3.4.1 and

Section 3.4.2 reveals a policy architecture marked by impressive institutional sophistication but constrained by systemic fragmentation. It has achieved world-leading decarbonization in sectors under direct regulatory authority, like electricity. However, entrenched provincial autonomy, fossil-fuel dependence, and uneven federal–provincial coordination continue to limit the scope and speed of its economy-wide energy transition. This highlights that governance coherence, rather than technological capacity, remains the decisive factor in Canada’s pathway to net zero.