3.2. Cardiometabolic Health Responses

Blood glucose, plasma insulin and triglyceride concentrations across the exercise and resting trial are presented in supplementary tables 1a and 1b.

3.2.1. Blood Glucose Concentrations

Postprandial Blood Glucose, Glucose iAUC and Glucose Peak in Children

In children, blood glucose concentration was similar between the exercise and rest trials following the consumption of the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; p = 0.507) but changed over time (main effect of time; F (3, 39) = 16.66, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.562). The pattern of change in blood glucose concentration was similar between the exercise and resting control trial (trial*time interaction; p = 0.469).

In children, postprandial glucose iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting control trial (p = 0.211), nor were there any differences in peak blood glucose concentrations between trials (p = 0.850).

Postprandial Blood Glucose, Glucose iAUC and Glucose Peak in Parents

In parents, blood glucose concentration was similar between the exercise and rest trials following the consumption of the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; p = 0.654) but changed over time (main effect of time; F (3, 30) = 5.92, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.372). The pattern of change was similar between the exercise and resting control trial (trial*time interaction; p = 0.616).

In parents, postprandial glucose iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting control trial (p = 0.076), nor were there any differences in peak blood glucose concentrations between trials (p = 0.633).

Family Analysis

There was no difference in postprandial blood glucose concentration between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.126). Furthermore, the postprandial blood glucose response to exercise and rest was similar between children and parents (age*trial interaction; p = 0.959), and the pattern of change over time was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.053). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.745).

There was no difference in glucose iAUC between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.144). Furthermore, the blood glucose iAUC response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.800).

There was no difference in peak blood glucose concentrations between children and parents (main effect of age; p = 0.724). Furthermore, the peak blood glucose response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.822).

3.2.2. Plasma Insulin Concentrations

Postprandial Plasma Insulin, Insulin iAUC and Insulin Peak in Children

In children, plasma insulin concentration was similar between the exercise and resting trial following the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; p = 0.067) but changed over time (main effect of time; F (3, 45) = 32.87, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.687). The pattern of change was similar between the exercise and resting trials (trial*time interaction; p = 0.134).

In children, postprandial insulin iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting trial (p = 0.712), nor were there any differences in peak plasma insulin concentrations between the exercise and resting trials (p = 0.184).

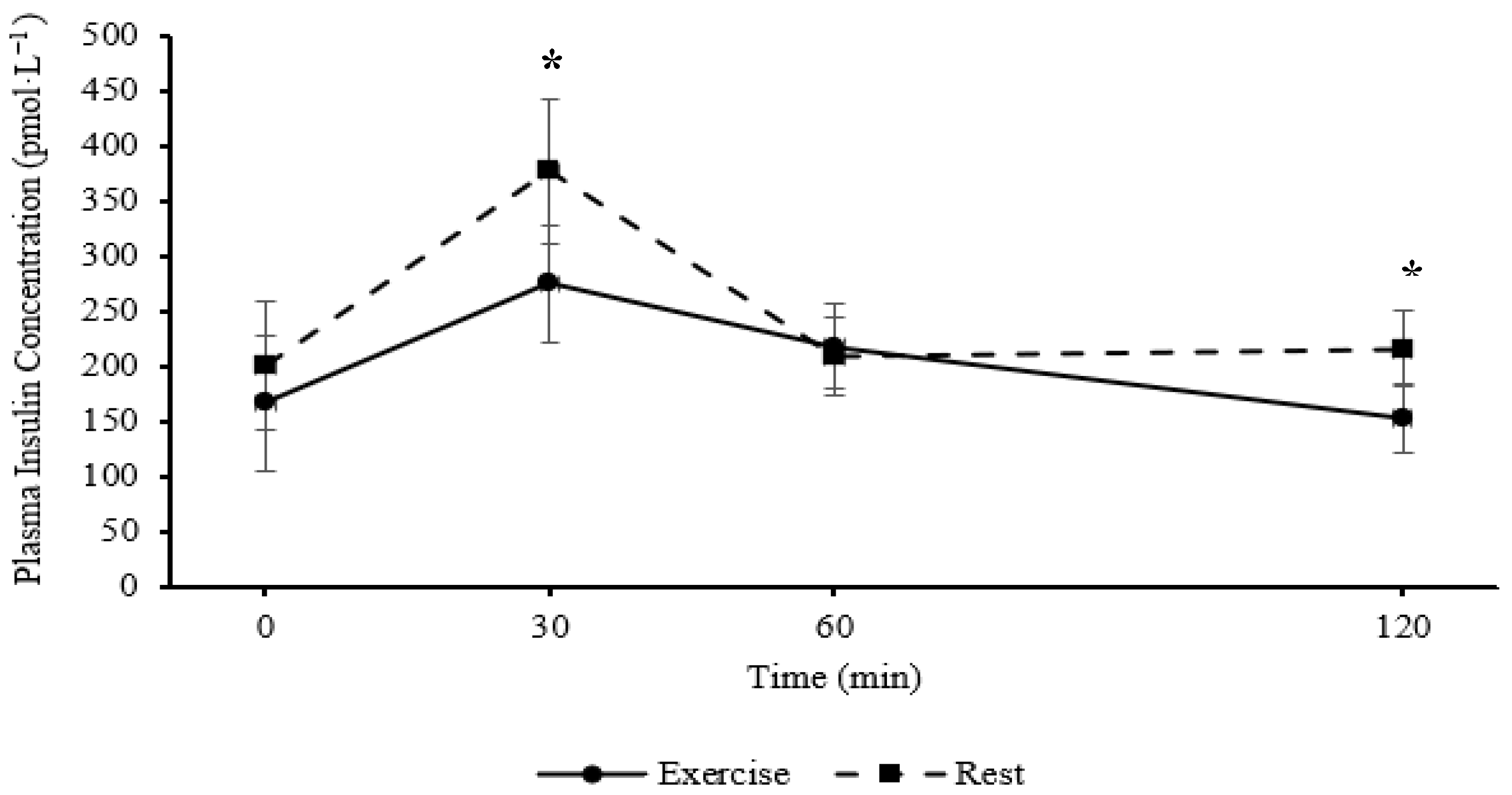

Postprandial Plasma Insulin, Insulin iAUC and Insulin Peak in Parents

In parents, plasma insulin concentration was lower during the exercise trial compared to the resting trial following the consumption of the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; F

(1, 12) = 5.32,

p = 0.040, MD = -0.11 pmol·L

−1 , 95% CI [-0.22, -0.01 pmol·L

−1]), and changed over time (main effect of time; F

(3, 36) = 8.67,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.419). In parents, the pattern of change differed between the exercise and resting trials (trial*time interaction; F

(3, 36) = 2.99,

p = 0.044, η

p2 = 0.200), whereby plasma insulin concentration was lower 30-min (p = 0.004) and 120-min post lunch (

p = 0.011,

Figure 1) in the exercise trial when compared with the rested control trial.

In parents, postprandial insulin iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting trial (p = 0.459). Peak plasma insulin concentrations following the standardised lunch were lower in the exercise trial compared to the resting trial (t (12) = -3.60, p = 0.004, 95% CI [-0.18, -0.04 pmol·L−1]).

Family Analysis

There was a difference in postprandial plasma insulin concentration between children and parents across the exercise and rested control trial (children: 1.9 pmol·L−1 , parents: 2.2 pmol·L−1 ; main effect of age; p = 0.017), whereby plasma insulin concentration was greater in parents than children. The postprandial plasma insulin response to exercise and rest was similar between children and parents (age*trial interaction; p = 0.941), however the pattern of change over time was different in children and parents (time*age interaction; F (3, 81) = 5.01; p = 0.003; ηp2 = 0.157), whereby plasma insulin concentrations were lower in children than in parents at baseline (p = 0.003) and 120-min (p = 0.035) post lunch across the exercise and rest trials. The effects of exercise and rest was different between children and parents over time (trial*time*age interaction; F (3, 81) = 3.82; p = 0.013; ηp2 = 0.124), whereby plasma insulin concentrations were lower 30-min (p = 0.011) and 120-min (p = 0.006) post lunch during the exercise trial compared to the rest trial in parents, whilst the pattern of change in children across time was similar between trials.

There was no difference in insulin iAUC between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.671). Furthermore, the response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.799).

There was no difference in peak plasma insulin concentrations between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.165). Furthermore, the response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.321).

3.2.3. Plasma Triglyceride Concentrations

Postprandial Triglycerides, Triglyceride iAUC and Triglyceride Peak in Children

In children, triglyceride concentration was similar between the exercise and resting trial following the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; p = 0.251) and did not change over time (main effect of time; p = 0.070). Furthermore, the pattern of change was similar between the exercise and resting trials (trial*time interaction; p = 0.255).

In children, postprandial triglyceride iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting trial (p = 0.373), nor were there any differences in peak triglyceride concentrations between the exercise and resting trials (p = 0.393).

Postprandial Triglycerides, Triglyceride iAUC and Triglyceride Peak in Parents

In parents, triglyceride concentration was similar between the exercise and resting trials following the standardised lunch (main effect of trial; p = 0.282) but changed over time (main effect of time; F (3, 33) = 4.16, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.274). Furthermore, the pattern of change was similar between the exercise and resting trials (trial*time interaction; p = 0.093).

In parents, postprandial triglyceride iAUC following the standardised lunch did not differ between the exercise and resting trial (p = 0.164), nor were there any differences in peak triglyceride concentrations between the exercise and resting trials (p = 0.181).

Family Analysis

There was no difference in postprandial plasma triglyceride concentration between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.129). The postprandial plasma triglyceride response to exercise and rest was similar between children and parents (age*trial interaction; p = 0.752), and the pattern of change over time was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.707). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.277).

There was no difference in plasma triglyceride iAUC between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.952). Furthermore, the response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.106).

There was no difference in triglyceride peak concentrations between children and parents across the exercise and resting trial (main effect of age; p = 0.132). Furthermore, the response to exercise and rest in children and parents was similar (age*trial interaction; p = 0.713).

3.3. Cognitive Function Outcomes

Cognitive function inverse efficiency scores across the exercise and resting trial are presented in supplementary table 2.

3.3.1. Stroop Test

Children

Overall inverse efficiency scores for the Stroop congruent level were similar between the exercise and rested control trial in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.971) and were similar across time (main effect of time; p = 0.326). The pattern of change between the exercise and resting trial was also similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.717).

For the Stroop incongruent level, inverse efficiency scores were similar between the exercise and resting trials in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.633) and were similar over the course of the day (main effect of time; p = 0.319). Furthermore, the pattern of change between the exercise and resting trial was similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.209).

Parents

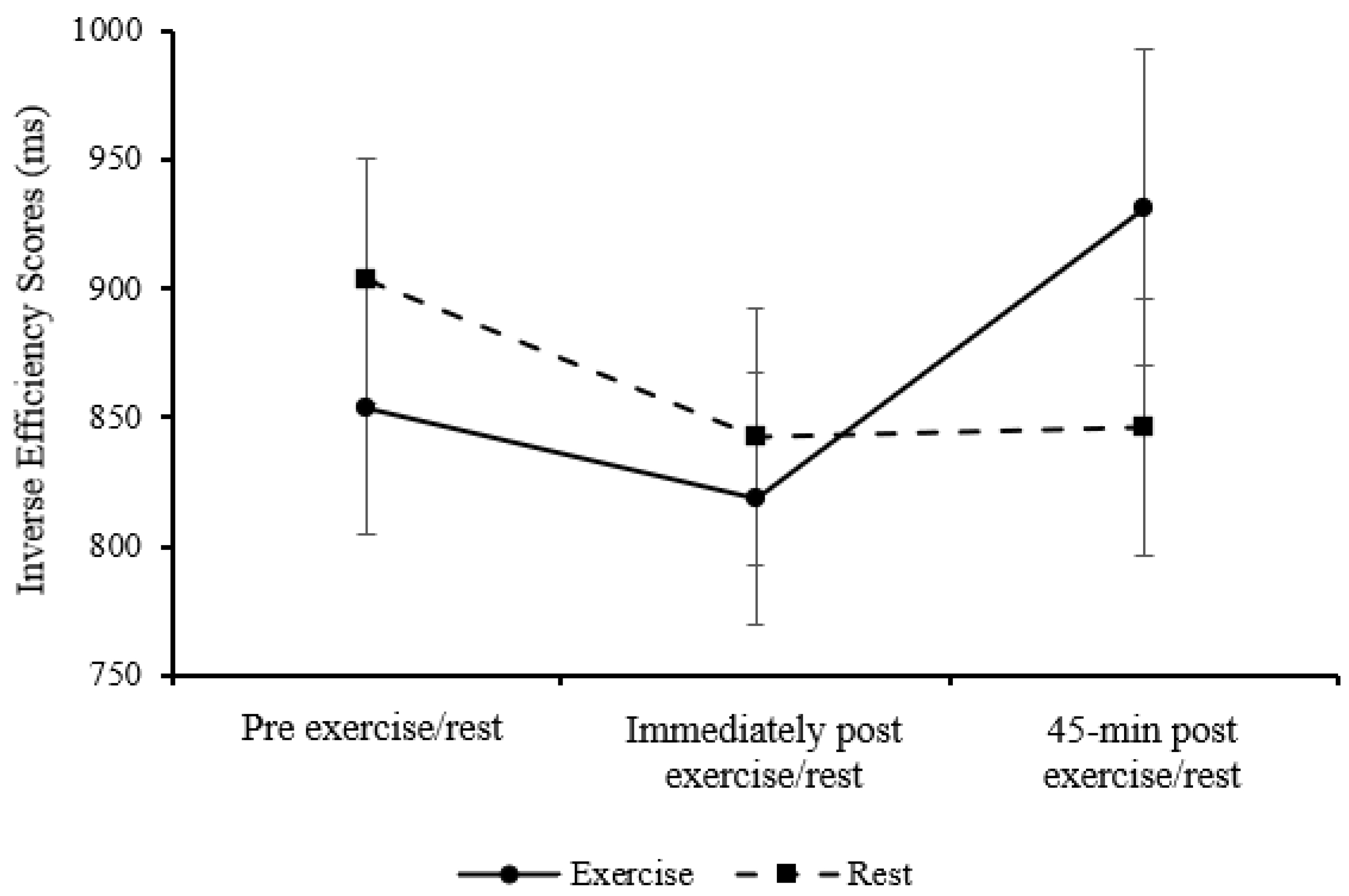

Overall inverse efficiency scores for the Stroop congruent level were similar between the exercise and rested control trial in parents (main effect of trial;

p = 0.129) and improved over the course of the day (main effect of time; F

(2, 34) = 3.58,

p = 0.039, η

p2 = 0.174). Furthermore, the pattern of change differed across trials (trial*time interaction; F

(2, 34) = 5.07,

p = 0.012, η

p2 = 0.230,

Figure 2), with an improvement in inverse efficiency scores immediately post-exercise (p = 0.016).

Inverse efficiency scores for the Stroop incongruent level were similar between the exercise and rested control trial in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.555) and improved over the course of the day (main effect of time; F = 6.83, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.299). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.134).

Family Analysis

There was no difference in inverse efficiency scores on the congruent level of the Stroop test between children and parents across the exercise and rest trial (main effect of age; p = 0.254). Furthermore, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and resting trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.579), and the pattern of change over the course of the day was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.850). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over the course of the day (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.379).

There was no difference in inverse efficiency scores on the incongruent level of the Stroop test between children and parents across the exercise and rest trial (main effect of age; p = 0.420). Furthermore, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.482), and the pattern of change over the course of the day was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.704). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over the course of the day (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.110).

3.3.2. Sternberg Paradigm

Children

Inverse efficiency scores for the Sternberg one-item level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.662) and were similar over the course of the day (main effect of time; p = 0.716). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.071).

For the Sternberg three-item level, inverse efficiency scores were similar between the exercise and rest trials in children (main effect of trial;

p = 0.872) and were similar over the course of the day (main effect of time;

p = 0.104). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial differed (trial*time interaction; F

(2, 42) = 4.60,

p = 0.016, η

p2 = 0.180,

Figure 3), however, inverse efficiency scores immediately post-exercise and 45-min post-exercise were not statistically significant (immediately post-exercise,

p = 0.489; 45-min post-exercise,

p = 0.093).

Inverse efficiency scores for the Sternberg five-item level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.581) and improved immediately post-exercise or rest and worsened 45-min post exercise and rest (main effect of time; p = 0.030). Furthermore, the pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.255).

Parents

Inverse efficiency scores for the Sternberg one-item level were similar between the exercise and rest trial in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.122) and improved over the course of the day (main effect of time; F = 6.83, p = 0.014, ηp2 = 0.233). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.423).

For the Sternberg three-item level, inverse efficiency scores were similar between the exercise and rest trial in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.116) and improved over the course of the day (main effect of time; F = 6.83; p = 0.016; ηp2 = 0.226). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.311).

Inverse efficiency scores for the Sternberg five-item level were similar between the exercise and rest trial in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.373) and were similar over the course of the day (main effect of time; p = 0.167). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial were similar (trial* time interaction; p = 0.951).

Family Analysis

There were differences in inverse efficiency scores on the Sternberg one-item level between children and parents across the exercise and rest trial (children: 661.4 ms, parents: 543.3 ms; main effect of age; p = 0.013), whereby parents performance was significantly better than children’s. However, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.366), as was the pattern of change over the course of the day (time*age interaction; p = 0.593). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents across time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.066).

There was a difference in inverse efficiency scores on the three-item Sternberg level between children and parents (children: 872.3 ms, parents: 656.9 ms; main effect of age; p = 0.002), whereby parents performance was significantly better than children’s. Inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.519). Yet, the pattern of change across time was different in children and parents (time*age interaction; F(2, 74) = 4.10, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.098), whereby children’s inverse efficiency scores were lower immediately following exercise and rest. However, children’s inverse efficiency scores increased 45-min post-exercise or rest, whilst parents’ scores remained low. The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.397).

There was a difference in inverse efficiency scores on the five-item Sternberg level between children and parents (children: 1081.5 ms, parents: 790.5 ms; main effect of age; p < 0.001), whereby parents performance was significantly better than children’s. Furthermore, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.327), and the pattern of change over time was different in children and parents (time*age interaction; F(2, 72) = 4.60 p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.113), whereby children’s inverse efficiency scores were lower immediately following exercise and rest but increased 45-min post-exercise or rest. Parents’ inverse efficiency scores were higher immediately following exercise/rest and decreased 45-min post-exercise/rest. The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.310).

3.3.3. Flanker Task

Children

Overall inverse efficiency scores for the Flanker congruent level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.207) and were similar across time (main effect of time; p = 0.500). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial was similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.610).

Inverse efficiency scores for the Flanker incongruent level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in children (main effect of trial; p = 0.420) and were similar across time (main effect of time; p = 0.279). The pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial was similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.358).

Parents

Overall inverse efficiency scores for the Flanker congruent level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.665) and were similar across time (main effect of time; p = 0.204). Furthermore, the pattern of change between the exercise and resting trial was similar (trial *time interaction; p = 0.242).

Inverse efficiency scores for the Flanker incongruent level were similar between the exercise and rest trials in parents (main effect of trial; p = 0.384) and were similar across time (main effect of time; p = 0.657). Furthermore, the pattern of change between the exercise and rest trial was similar (trial*time interaction; p = 0.106).

Family Analysis

There was a difference in inverse efficiency scores on the congruent level of the flanker task between children and parents (main effect of age; p = 0.020), whereby children’s inverse efficiency scores were higher than their parents. Yet, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.213), and the pattern of change across time was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.931). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents across time (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.274).

There was no difference in inverse efficiency scores on the incongruent level of the Flanker task between children and parents (main effect of age; p = 0.066). Furthermore, inverse efficiency scores were similar in children and parents between the exercise and rest trial (age*trial interaction; p = 0.516), and the pattern of change over the course of the day was similar in children and parents (time*age interaction; p = 0.346). The effects of exercise and rest did not differ between children and parents over the course of the day (trial*time*age interaction; p = 0.281).

3.4. Focus Groups and Interviews

Families highlighted several factors which shaped their perceptions of their enjoyment of the tag-rugby session, and the feasibility of implementing tag-rugby at home. Specifically, two themes were developed for enjoyment: inclusivity and whole family enjoyment, and engaging elements that captivate children and parents. Three themes were developed for feasibility: modality, intensity and session duration, integrating family tag-rugby into family life, and traditional low impact sports as alternatives.

Illustrative quotes are presented in supplementary table 3, with a focus within the text on themes which were most prevalent in the focus groups/interviews and most significant in their impact.

3.4.1. Families Perceived Enjoyment of Tag-Rugby

Overall, families felt the tag-rugby session provided an inclusive environment for children and their parents to exercise, and the enjoyment of the session outweighed the fact that they were exercising. Furthermore, tag-rugby was highlighted as an exercise modality that parents and their children can, and want to, participate in together.

Inclusive and Enjoyable for the Whole Family

All families, regardless of socioeconomic status, felt that the enjoyment of the tag-rugby session surpassed the fact that they were exercising. One mother from the low socioeconomic status group reflected that tag-rugby brings an enjoyable aspect to physical activity.

“But they [daughters] tend to moan a lot, you know, like oh you know, my legs are hurting. When are we there yet? So I think the tag-rugby thing brings the fun aspect to it where they don't actually realise that they're exercising. Yeah, because they're enjoying what they're doing, you know?” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

When discussing the tag-rugby session with parents alone, regardless of their socioeconomic status, most suggested they preferred to participate in physical activity without their children in general due to factors such as differing abilities and interests, and wanting time to themselves. However, they felt that tag-rugby created an inclusive environment for the whole family, which provided a novel, interactive and viable opportunity to exercise as a family.

“I think it was nice for me to do that with the children. Yeah, because I guess there are sports that the children do where they're doing it themselves and you're watching them, aren't you? So it's quite a nice activity to get involved in where, yeah, you know you have enjoyed and have fun together. Yeah. So, yeah, I thought it was, it was nice” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“Yeah, I mean the weather was great and there were different tasks and it was interactive with ages and the families as well, so it was good” (Mother, middle socioeconomic status)

Similarly, children, regardless of their socioeconomic status, suggested that they typically preferred to participate in physical activity without their parents. Following this, they implied that they would like to participate in tag-rugby again with their parents, as it was fun and novel.

“I think it depends what it is [mode of physical activity], because if it was like that fun tag-rugby then that's fine. If it was at like a different level, then I'd rather do it myself, yeah” (Daughter, high socioeconomic status)

Furthermore, all children reflected on the opportunities available to them for family physical activity and felt that tag-rugby provided an opportunity for them to exercise as a unit, something they wouldn’t normally do.

“I think it was fun because we don’t normally do stuff like that with each other, so it’s like very different” (daughter, high socioeconomic status)

Engaging Elements that Captivate Children and their Parents

Parents from the low socioeconomic group felt their children were faster and more capable during the tag-rugby small-sided games, however, this was deemed as encouraging for parents and a facilitator for future participation.

“It was challenging because they’re kids, you know, they're faster than that. So yeah, they've got more energy, though they're pushing us” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

Conversely, parents in the middle-high socioeconomic groups felt that even though the session was fast moving, they were able to keep up with their children during the session. Additionally, they felt the fast-paced nature of the session kept everyone engaged.

“I thought it was good because it was quite fast moving, and so it kept everyone interested. You were just, before you could get bored anything like that in terms of switching it kept everybody on their toes and kept everybody engaged so that was quite good” (Mother, middle socioeconomic status)

Regardless of socioeconomic status, most parents preferred the organised drill component of the tag-rugby session. They suggested that this provided a structured environment for them to exercise, further suggesting that the small-sides games were “not well organised” (Mother, low socioeconomic status). Parents in the middle-high socioeconomic groups suggested that including more rules during the small-sided games would maintain structure so that children would not misbehave and interrupt the session.

“It [tag-rugby game] almost got too, too free, but then some of us wanted to bring it back a little bit whereas the kids just wanted to carry on being silly. Not that it was a bad thing to be silly, we were just thinking more of the game” (mother, high socioeconomic status)

Conversely children from all socioeconomic groups preferred the small-sided games, and described the drill component as repetitive, which hindered enjoyment.

“I liked the drills except when it got repetitive, so for quite a long time it didn’t feel as fun” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

They further explained that the small-sided games were relaxed and non-competitive allowing them to focus on having fun.

“It [tag-rugby game] was very very fun. It didn’t feel that competitive. I felt like I was more having fun than competitive” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

Thus, there seems to be a generational difference in preferences; parents favour organised components with more structure, while children prefer a more relaxed approach. Future interventions should offer a variety of activities that incorporate structured drills with casual game elements, catering to children and parents.

3.4.2. Feasibility of Implementing Family-Based Tag-Rugby at Home

Overall, families from all socioeconomic groups felt that 45-min of tag-rugby, 1-3 times per week would feasibly work for them, whilst perceptions of the intensity of the session varied across generations, as well as across socioeconomic groups.

Modality, Intensity and Duration of the Session

All families, regardless of socioeconomic status, acknowledged that the 45-min tag-rugby session was not overly time-consuming. They further expressed that the duration of the session was right for them, and parents from the low socioeconomic status group felt that the inclusion of breaks was ideal.

“No, it was ok because, because there was, there was a, there was half time, so there was half time. So, it’s ok when doing it, she gave us a minute. Then we continue” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

Families from the low socioeconomic group described the flexible nature of tag-rugby by discussing how it can be adapted to different settings, including indoors or outdoors, and can be inclusive for multiple families too. They further suggested that this would allow friendships between families to form and highlighted that it’s a form of physical activity that can be utilised to break the day up.

“Similar to how you might go out and walk the dog, you could be with your kids on the field playing something like that. Couldn't you, just to break the day up or something? You know, for half an hour or whatever” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“For me, I think it's nice to do it with multiple families. There's more interaction and the kids can have friends, and you know, we can make friends as well” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

When discussing the intensity of the session, parents from the low socioeconomic status group found the intensity to be just right, whereas middle-high parents, and children from all socioeconomic groups felt they could have done more. Children preferred if the session included “more running around” (son, low socioeconomic status), however, they explained that the session was tiring.

“I think it could’ve been a bit more high intensity just for myself because erm I didn’t feel like I was going as fast as I could’ve but it was tiring” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

Parents from the middle socioeconomic group suggested that the pitched area for the small-sided games could’ve been bigger to encourage them to work harder.

“You could make the pitch a bit bigger so that there was more intensity encouraged and more going on, I think that might help” (mother, middle SES)

Finally, all families deemed tag-rugby to be an outdoor sport, and thus participating outside, particularly during the warmer, lighter summer months was most favourable.

“Yeah, especially in the summer when it’s light and you can go out and enjoy the weather” (Father, high socioeconomic status)

Integrating Tag-rugby into Family Life

All families discussed life commitments as a barrier to participating in physical activity together, and particularly for implementing family tag-rugby at home. While most children explained that they participate in physical activity regularly when under the care of their parents, parents identified responsibilities including work commitments and family duties as barriers to tag-rugby implementation at home.

“It depends what world we’re living in, if I could be doing something with him once a day I would, but in the reality we are living in with school, other extra curriculars, we could only fit in once a week” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

However, families believed they would want to participate in tag-rugby frequently and suggested that one to three times a week would be feasible. Specifically, the mornings of weekends were most desirable to participate in family tag-rugby, and after school or work were considered by some families too.

“Ermm mornings like after I wake up after breakfast. Erm, because I think morning is when I, I feel more energetic and it works better” (Son, middle socioeconomic status)

Therefore, future interventions should recognise these barriers whilst personalising the approach for each family, to ensure the inclusion of both children and their parents.

Traditional team sports and low impact sports as alternatives to tag-rugby

Families discussed possible alternatives to family-based tag-rugby and reflected on past opportunities they had taken for family physical activity. Two approaches were discussed by all families, which included team-based and low impact sports.

Families discussed alternatives to family-based tag-rugby, and not surprisingly, the most favoured were traditional team sports such as football, basketball, dodgeball and netball, which were most favoured by children. The children suggested that these were the sports they were most familiar with, and interested in.

“Because I quite like dodgeball and I quite like playing with my parents so that would be quite fun” (son, high socioeconomic status)

Conversely, parents spoke of their experiences of participating in physical activity with their children, and contrary to team-based sports, the most familiar were low impact sports such as walking, cycling or swimming.

“So going for walks in the countryside would be my top one because they're really chilled out. And they get on really well and they laugh a lot when we do go for walks. Yeah, I know they love going swimming into water parks. I really don't like it, so I wish I liked swimming more. Whenever you say, what do you want to do? They'll say family swim, which involves me going on slides and stuff. Erm yeah which I'm a bit funny about water, I don't really like the water. Erm, but yeah, that that would if I if I could get around it that would be a good one for us” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

They further explained that family physical activity can be combined with other elements, turning it into a family day out that includes alternative ways of engagement and bonding, such as visiting restaurants or playing card games.

“And then especially if you can mix it in with going for pub lunch and taking, like, card games. So, that, that would be my favourite thing” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

Thus, future interventions could consider games-based alternatives to tag-rugby. Furthermore, including aspects beyond physical activity (such as family activities following a family-based physical activity session) could be considered to aid with motivation.