1. Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is the most common presentation of food allergy among infants [

1]. The prevalence of CMA is uncertain, with figures up to 7.5% before the age of 1 year [

2], however, evidence suggests frequent over-diagnosis, since the prevalence of authenticated CMA is <1% [

3]. CMA is influenced by many variables such as geographical location, breastfeeding status, and family history of allergies [

2,

4]. The prevalence varies depending on the methods used for assessment and diagnosis, hence healthcare professionals (HCPs) are encouraged to properly follow dedicated guidance before embarking on a long-term therapeutic elimination diet [

3].

The gold-standard method for diagnosis of CMA is a short elimination diet for 2–4 weeks, followed by oral food challenge (OFC), performed according to existing guidelines [

5]. In addition, skin prick testing or

in vitro specific IgE testing is also recommended for diagnosing IgE-mediated CMA [

6]. A clinical tool named The Cow’s Milk-Related Symptom Score (CoMISS

®) was developed to increase awareness of CMA among HCPs [

7]. Since its development, the tool has been used in many original research studies. CoMiSS can also be used to evaluate and quantify the evolution of symptoms during an elimination diet [

8]. Use of this tool in clinical practice can increase CMA awareness and avoid over- and underdiagnosis [

3,

7].

Whilst the role of breast milk in preventing food allergies is unclear, IgE-mediated CMA in exclusively breastfed infants is quite rare [

3]. Breastfeeding provides many benefits to infants [

9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [

10], and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) recommends that exclusive or full breast-feeding should be promoted for at least 4 months (17 weeks, beginning of the 5th month of life) and exclusive or predominant breast-feeding for approximately 6 months (26 weeks, beginning of the 7th month) is a desirable goal. Complementary foods (solids and liquids other than breast milk or infant formula) should not be introduced before 4 months but should not be delayed beyond 6 months [

11,

12]. In those women who are unable to breastfeed, or who choose not to, cow’s milk-based infant formulas provide safe and nutritionally adequate alternatives.

The first line of treatment in confirmed cases of CMA in formula-fed infants usually includes an extensively hydrolysed formula (eHF), hydrolysed rice formula (HRF), or amino acid formula (AAF) in more severe cases [

2,

3]. Whilst not recommended in current ESPGHAN, EAACI, World Allergy Organization (WAO) or American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the management of CMA, a partially hydrolysed whey-based formula (pHF-W) is used in certain countries as a step down, or bridge, when transitioning from eHF/HRF/AAF to intact CM formula [

13]. Multiple studies have suggested a long-term benefit of pHF for allergy prevention in infants with a family history of atopy [

14,

15,

16] and beneficial gastrointestinal tolerance and digestibility compared to intact cow’s milk [

8,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, its use in the nutritional management of CMA remains unclear [

3]. Clinical studies to establish the efficacy and safety of pHF-W for use in a step-down approach are very limited. There are some data showing improved tolerance to intact cow’s milk protein (CMP) following oral immunotherapy with pHF vs eHF [

22]. In another study, 64% of children with confirmed CMA tolerated pHF-W after oral challenge [

23].

Real world use of pHF in a step-down approach is reported [

13,

24], however, there are no large surveys of its utilisation or HCP experiences, which could provide some useful insights and guidance for clinical practice. To better understand real-world practice and experiences regarding the nutritional management of CMA, particularly the use of pHF in a step-down approach, we carried out a survey of 600 physicians in China and the Middle East, countries where this approach is used. We also discuss the rationale which may underlie the use of pHF in this way.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted to investigate current practices in the nutritional management of CMA among HCPs in the Middle East and China.

A pilot survey was pre-tested in China. More information on this is available in the Supplementary Material. Based on the pilot findings, the final survey questions and flow, which were co-developed by Nestlé and the academic authors, were refined. IPSOS optimised the questionnaire, implemented the survey and was responsible for translations into local languages, which were validated by native speakers. Countries were selected by the regions known to have some use of pHF in a step-down practice.

A mix of HCPs who manage infants with CMA in their daily practice were randomly selected by IPSOS from China and the Middle East (Gulf area). HCP specialties included general paediatricians, paediatric gastroenterologists, dermatologists, neonatologists and allergists/immunologists. Within the survey participants, there was a proportional representation for each country and a spread of specialities from each region (

Table 1).

The survey duration was either 5 minutes (for HCPs not using pHF in a step-down approach) or 15 minutes (for those HCPs applying the step-down approach with pHF). The 25-item questionnaire (Supplementary

Table 1) achieved a sample size of 600 HCP respondents across target regions, with country-level quotas as follows: China (n=400), Bahrain (n=20), Kuwait (n=20), Saudi Arabia (n=130), and United Arab Emirates (n=30). HCPs provided consent on terms and conditions, and a privacy policy upon joining the survey. They were informed in advance about the topic and length of the survey and were therefore able to make an informed decision whether to participate or not in the study. Exclusion criteria included general practice HCPs (GPs) and those with less than 3 years’ experience.

A simple random sampling method was used for each country in the Middle East. Cluster sampling methodology was used in China, with the following locations/provinces: Anhui, Beijung, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hangzhou, Hebei, Henanm Heilongjiang, Hubei, Hunan, Jilin, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Ninxia, Shandong, Shanxi, Shanghai, Sichuan, Tianjin, Xinjiang, Yunnan, Zhejiang, and Chongqing.

The survey respondents were all from IPSOS HCP panels, and the requests were sent out using individualised invitation delivery. No multiple links were delivered and there was no possibility of duplicate participation. The active fieldwork time was from 28/10/2024 to 25/11/2024. The total average response/completion rate was 53%, with individual country response rates of: 51% (UAE), 58% (Saudi Arabia), 49% (Kuwait), 41% (Bahrain), and 68% (China).

2.2. Data Analysis

Survey data were analysed using R-Project version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14 ucrt), platform: x86_64-w64-mingw32/x64, running under: Windows 10 x64 (build 19045).

Data were analysed overall and split by country: China and the Middle East (all); China, Middle East (without Saudi Arabia); and Saudi Arabia. The other Middle East countries (Bahrain and Kuwait) did not allow a split by country due to lower respondent numbers.

Continuous variables were summarised using the following descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviation, minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, maximum, and the number of participants. These variables were visualised using histograms. Identical summarisation and visualisation were conducted for the data segmented by geographical area and field of practice. For categorical variables derived from single-choice questions, results were reported as percentages, with the total summing to 100%. These variables were visualised in bar graphs. Categorical variables originating from multiple-choice questions were reported as the percentage of participants selecting each potential answer, also visualised in bar graphs. Supplementary visualisations were performed by geographical area, field of practice, years of experience (split by median) or the number of CMA cases seen per month (also split by median). Variables measured on a Likert scale were represented as a 1-100% stacked bar chart.

3. Results

3.1. Survey respondents

A full listing of all the survey results, with sub-analyses by country, HCP specialisation, HCP years of experience, etc., is provided in the supplementary material. For the purposes of this manuscript, a descriptive summary of the key results is provided in the text.

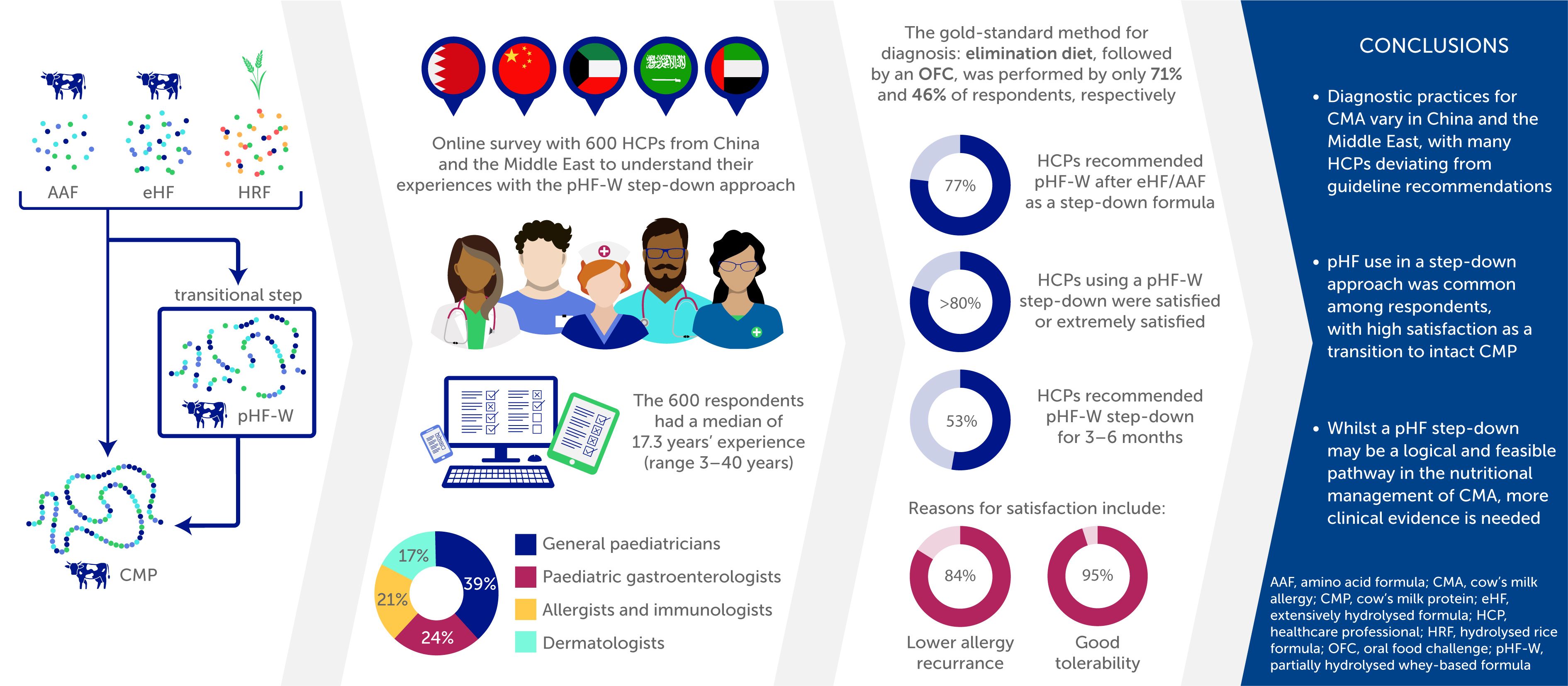

The 600 respondents were located in 135 cities or towns. The median age of participants was 42.4 years (range 26–65 years), with a median of 17.3 years’ experience (range 3–40 years), 31% were attending physicians, 31% were associate chief physicians, 19% were chief physicians, 19% were physicians (private practice). Of the 600 respondents, 39% were general paediatricians, 24% paediatric gastroenterologists, 21% allergists and immunologists and 17% dermatologists (supplementary results: survey Q1–Q6).

3.2. CMA Case Load and Diagnosis Practices

The median (range) number of suspected or confirmed CMA cases seen by the survey respondents per month (new and follow-up) was 15.5 (1–300) (supplementary results: survey Q7). The gold-standard test for both IgE and non-IgE mediated allergy is a food elimination diet followed by a confirmatory oral food challenge [

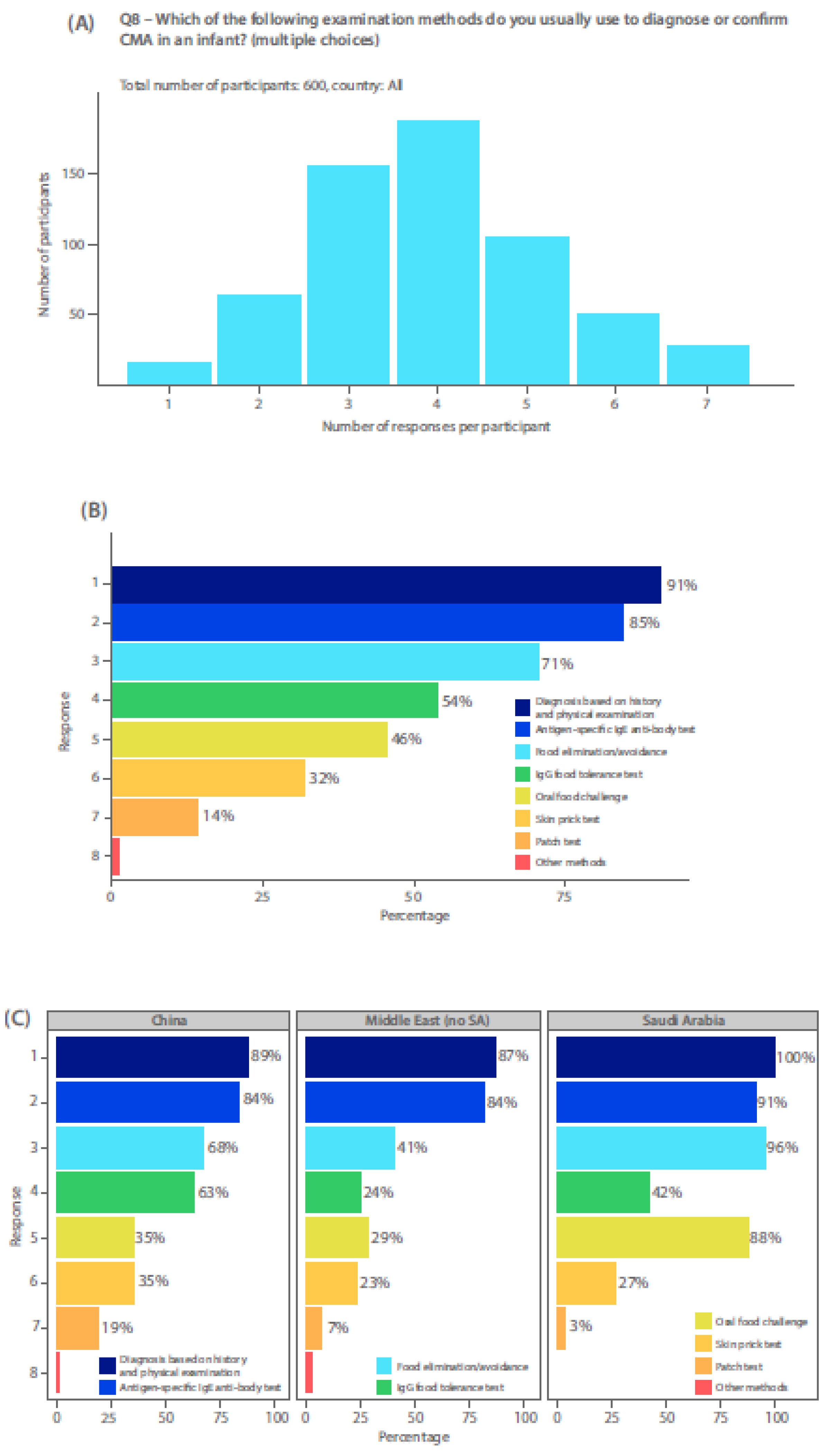

3]. IgE testing (antigen specific IgE antibody or skin prick test), when available, is also performed to identify any IgE-mediated mechanism for food allergy. HCPs completing the survey were mostly using a combination of three or four methods to diagnose CMA in their patients (

Figure 1a), including history and physical examination, food elimination/avoidance, antigen-specific IgE antibody test, OFC, skin prick tests, and patch tests (

Figure 1b). OFC was reported by only 46% (

Figure 1b). In Saudi Arabia, use of an OFC or food elimination/avoidance was much more common as a diagnostic tool, than in China or other Middle Eastern countries (

Figure 1c). Use of unvalidated diagnostic tests, such as an IgG food intolerance test, was used in China more frequently than an OFC. For both Chinese and Middle eastern survey respondents (excluding Saudi Arabia), food elimination diets or avoidance measures were more commonly done than performing an OFC (

Figure 1c). Most respondents used antigen specific IgE antibody testing to diagnose CMA, even over the use of OFC (

Figure 1c).

3.3. Current Practice and First-Line Management

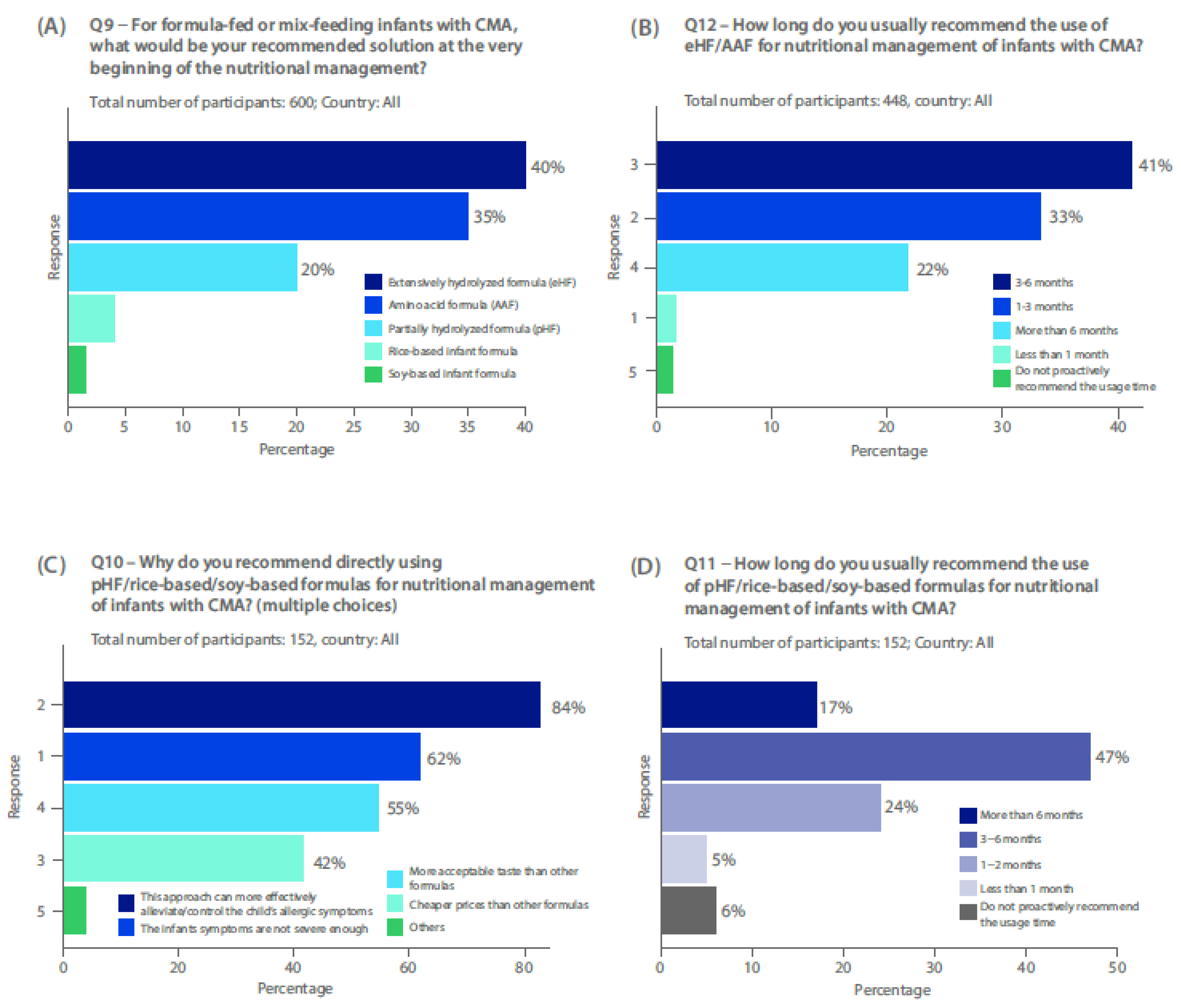

Most HCPs use eHF (40%), or AAF (35%) at the beginning of the nutritional management of CMA (

Figure 2a), with the majority of physicians recommending use of eHF or AAF first line for 3–6 months (41%), with 33% recommending 1–3 months and 22% >6 months (

Figure 2b)

Twenty percent of respondents use pHF-W for first-line nutritional management of CMA (

Figure 2a). Use of pHF-W first line was more common among HCPs from China (26%) and the Middle East (excluding Saudi Arabia) (20%), but only a small percentage of HCPs use pHF-W first-line in Saudi Arabia (supplementary results: survey Q9). In those 152 survey respondents using first-line pHF-W, HRF or soy-based formulas, 84% stated that use can effectively alleviate allergic symptoms, 62% stated it may be useful in less severe cases of CMA, and 55% said that it was cheaper than other formulas (

Figure 2c). Most HCPs using pHF-W, HRF or soy-based formulas first line, recommended it for 3-6 months (47%), or 1-2 months (24 %) (

Figure 2d).

3.4. Step-Down Approach with pHF-W

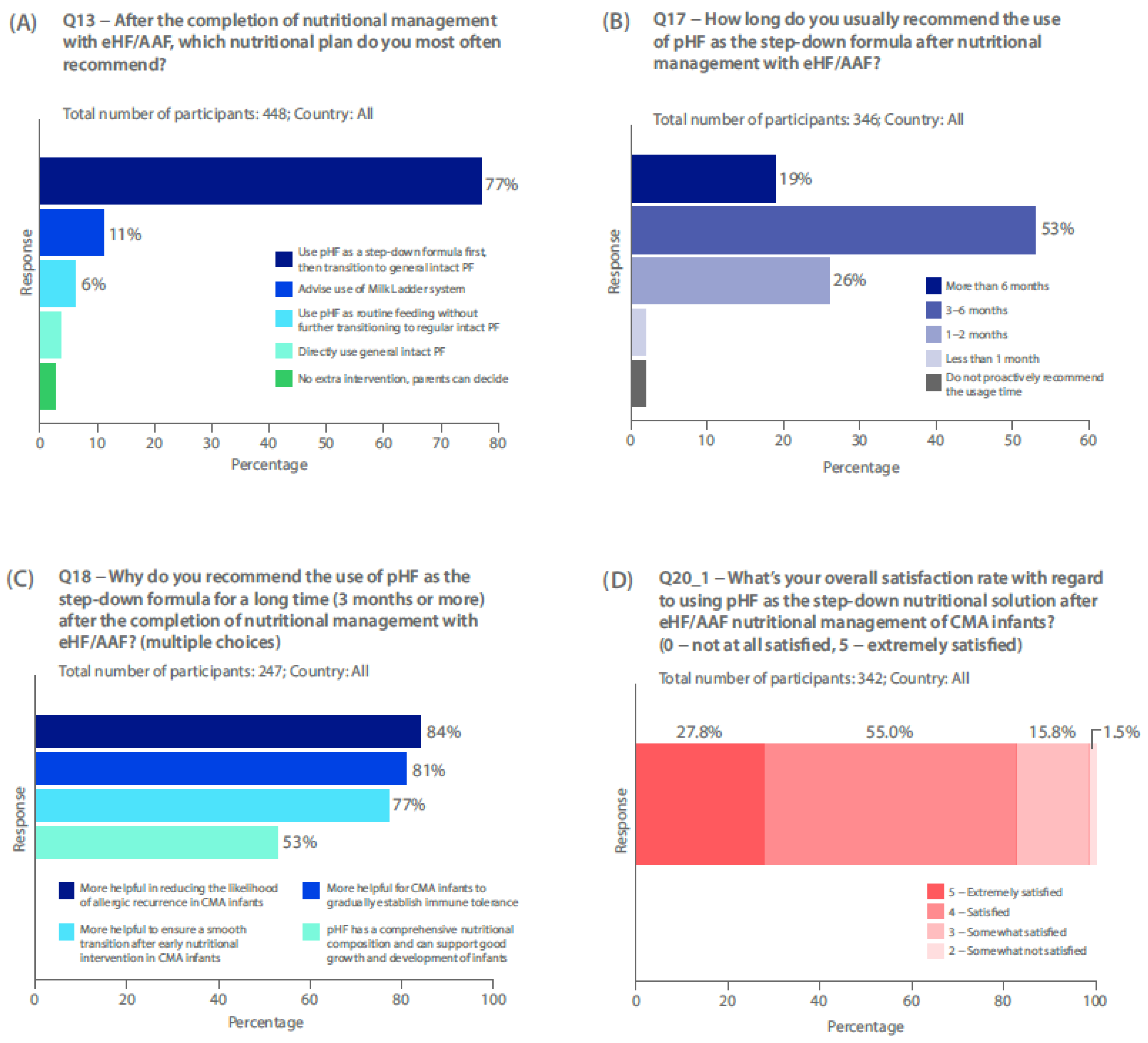

Seventy-seven percent of survey respondents who use first-line eHF or AAF recommend use of pHF-W after eHF / AAF, as a step-down formula (n=346/448), before transitioning to general intact CMP during the management of CMA (

Figure 3a). Most respondents recommended use of pHF-W as a step-down formula after nutritional management with eHF or AAF, for 3–6 months (53%). Just over a quarter of HCPs recommend use for 1–2 months (26%), and 19% for >6 months (

Figure 3b). Most common reasons for recommending pHF-W as a step-down formula for 3 months or more included: more helpful in reducing the allergic recurrence (84%); more helpful for CMA infants to gradually establish immune tolerance (81%); and more helpful to ensure a smooth transition after early nutritional intervention (77%) (

Figure 3c). More physicians in the Middle East (excluding Saudi Arabia) recommend pHF for its comprehensive nutritional composition (92%) than in China (54%) or Saudi Arabia (44%) (supplementary results: survey Q18). In those limiting pHF-W to less than 3 months in a step-down approach (n=95), the most common reasons for this were: long-term use after symptom improvement is not necessary (77%); and worried about the incomplete nutritional composition of pHF-W (61%) (supplementary results: survey Q19).

In those HCPs not recommending a pHF-W step-down (n=76), the most common reasons were: worried about the incomplete nutritional composition of pHF, which may not support the good growth and development of infants (47%); and not recommended / endorsed by recent guidelines (41%) (supplementary results: survey Q14).

Most physicians recommend pHF-W step-down for those with moderate (62%), severe (50%), or mild (40%) IgE mediated CMA. Twenty-five percent of HCPs also recommend this approach in non-IgE-mediated CMA (supplementary results: survey Q16).

Over 80% of physicians are satisfied or extremely satisfied with using pHF-W as a step-down (

Figure 3d).

3.5. pHF-W Safety and Nutritional Adequacy

Reasons physicians stated for satisfaction with the pHF-W step-down approach included good tolerability during transition (95%). Other factors associated with satisfaction included: lower CMA allergy recurrence rate (84%); good for growth and development (72%); easier to be accepted by parents (53%); and good taste, easily accepted (47%) (supplementary results: survey Q21).

Physicians mostly recognise good tolerability with pHF-W during transition as reduced GI (93%) and skin (93%) symptoms. Other signs of good tolerability were stated as infants don’t develop irritability, crying, or poor sleep due to discomfort symptoms (83%) (supplementary results: survey Q22).

In those HCPs unsatisfied with pHF-W use in a step-down approach (n=5/342) the most common reason was insufficient nutrition (supplementary results: survey Q23).

4. Discussion

This survey of 600 HCPs has provided crucial insights into real-world clinical practice and experiences of HCPs managing CMA in China and the Middle East. There is wide use of pHF-W in these regions, particularly in a step-down approach, and high satisfaction among those HCPs who utilize it in this way - as a bridge between eHF, HRF or AAF and intact CMP. However, several findings highlight key gaps between international guideline recommendations and current clinical practice in these regions.

Firstly, the gold-standard method for diagnosis is the elimination diet for 2-4 weeks with a hypo-allergenic formula, performed by 71% of respondents, followed by an OFC, performed by only 46% of respondents, thus indicating potential for diagnostic errors. Although 85% of respondents used specific IgE antibody testing, use of this alone is not sufficient to diagnose non-IgE mediated CMA, thus an OFC is still necessary to validate the diagnosis. The mix of specialists could account the variability in diagnosis methods, and while the exact reasons are unclear, time constraints, limited resources, lack of availability, or poor awareness regarding guideline recommendations could also play a role. Additionally, OFC are frequently refused by parents since it can make their child unwell again or they may fear a severe reaction. This survey finding suggests that over- or mis-diagnosis remains a significant risk and is consistent with prior studies demonstrating variable adherence to diagnostic guidance across different healthcare settings [

25,

26,

27,

28]. An international survey of over 1,600 clinicians demonstrated marked gaps in guideline awareness and diagnostic practices for CMA [

25]. Similarly, in Brazil, only a minority (16.7%) of paediatricians reported high adherence to international food allergy guidelines, with awareness and resource limitations as key hurdles [

26]. Another study identified large practice variations between gastroenterologists and immunologists with most physicians relying on symptom resolution for diagnosis, without guideline-recommended OFC [

27]. Lack of adherence to guidelines does not only reflect lack of knowledge or education but can also indicate that they are not practical or applicable for certain settings.

Secondly, whilst real world practice for the first-line nutritional management of ‘confirmed’ CMA in formula-fed infants in China and the Middle East largely reflects the current guidelines from ESPGHAN, EAACI and WAO [

2,

3,

4], with eHF and AAF being the most common choices, the use of pHF-W first-line (by 20% of survey respondents) diverges from these guidelines. Use of pHF-W first-line is not recommended, but may reflect regionally different practices, different reimbursements by health insurers across the regions; or use in cases of atopic dermatitis with evidence of positive IgE to CMP and limited resources/availability to perform OFC for confirming or excluding CMA diagnosis. An eHF is most commonly used for the diagnostic elimination diet and while pHF formulas are not recommended due to possible reactions,[

29] it cannot be ruled out that some HCPs are also using it in this way, as shown previously,[

30] or misusing it as a replacement for an OFC. Furthermore, although HRF is widely available in most European countries, low use in China and the Middle East could reflect lack of availability.

Current guidelines do not recommend pHF use as a step-down before reintroduction of intact CMP. Despite the lack of robust evidence, there is wide use of the step-down approach in China and the Middle East (excluding Saudi Arabia). HCPs reported high satisfaction and perceived benefits of pHF-W, including improved tolerance, and reduced allergy recurrence. In these regions, the step-down approach is used for patients with all CMA severities. A key issue could be that overdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of CMA was common among the survey respondents, accounting for the high satisfaction levels if some children never had confirmed CMA. Further, use of pHF-W in a stepdown approach to treat CMA may decrease it’s misuse as a diagnostic tool for the elimination diet. Regardless, whilst this approach could provide a gradual and logical pathway towards presenting intact CMP, more evidence and further clinical studies are required to fully understand the safety and efficacy of pHF use in this way. Despite survey respondents using pHF-W step down in IgE mediated CMA, caution would be advised since these patients may be at risk of severe reactions.

Concerns over nutritional adequacy of pHF were reported by a number of survey participants. The nutritional adequacy and safety of pHF-W is well known and well-documented [

31,

32], indicating knowledge/education gaps for some HCPs. The European Food Safety Authority consider pHF-W as a validated source of feeding for all infants, therefore, there are no nutritional issues associated with its use [

33]. In a 10-year follow-up of an RCT in which 1,840 infants were fed different formula, there were no long-term consequences on BMI in those receiving pHF-W compared with other formulas (eHF and CMF) or those exclusively breastfed [

34]. There were no substantial or significant differences at 10 years between any of the formula-fed or breastfed groups with respect to weight and length (z-scores), although feeding with casein-based eHF (eHF-C) did lead to a significantly slower BMI increase during the first year of life compared to breastfeeding [

35]. In a pooled analysis of seven clinical trials, including data from 511 infants, those fed pHF-W grew similarly to those fed standard formula, with both supporting adequate growth in infancy [

36]. It is also important to note that infant formulas can differ significantly due to variations in milk protein source and methods of hydrolysis. pHF-W can appear in various formulations; different pHF proteins may have distinct characteristics and may behave differently from an immunological perspective with changes in allergenicity and ability to induce oral tolerance [

37,

38].

Limitations of the survey include a lack of clear detail about how diagnoses of CMA were made, and the average age of patients when the decision to step down was made. As such, overdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of CMA cannot be ruled out, limiting the strength of conclusions that can be made from some of the survey findings. Further limitations of the survey design include allowing multiple responses to some questions meaning that it was not possible to distinguish between ‘not applicable’ and a missing answer [

39]. It would be interesting to perform the survey in a group of HCPs from a wider geographical area, including patients with a diagnosis of CMA based on current guidelines.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, many HCPs in China and the Middle East are deviating from the guidelines for diagnosis of CMA. Most HCPs report first line eHF or AAF for the nutritional management of CMA, however, pHF use is common, particularly in a step-down approach, with high satisfaction as a transition to intact CMP. A pHF step-down may be a logical and feasible pathway in the nutritional management of CMA, however, more evidence is needed. These findings underscore the need for educational interventions, greater dissemination of international guidelines, and further clinical trials evaluating pHF-W safety and efficacy in a step-down approach for the management of CMA.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Supplementary Methods document (PDF), Supplementary Results: HCP Survey document (PDF).

Author Contributions

All authors (E.E.B., Y.V., E.D., M.H., M.R., Y.W.; and A.E.) contributed to the conceptualization, and methodology (design) of the survey, provided critical interpretation of the data, and were involved in the writing—original draft preparation, review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nestlé. Medical writing support was also funded by Nestlé, however, they had no influence on the preparation and finalisation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with local/ national guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

HCPs provided consent on terms and conditions, and a privacy policy upon joining the survey. They were informed in advance about the topic and length of the survey and were therefore able to make an informed decision whether to participate or not in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the survey respondents for their valuable contribution and Eugenia Migliavacca of the Nestlé Biostatistics Team for analysis of the survey data.

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Emma East of Emma East Medical Writing. This support was funded by Nestlé.

Conflicts of Interest

E.E.B.: no conflicts of interest.

Y.V.: participated as a clinical investigator, and/or advisory board member, and/or consultant, and/or speaker for Abbott Nutrition, Alba Health, Arla, Biogaia, Danone, ELSE Nutrition, Friesland Campina, Nestlé Health Science, Nestlé Nutrition Institute, Nutricia, Pileje, United Pharmaceuticals (Novalac).

E.D.: speaking honoraria from Sanofi.

M.H.: no conflicts of interest.

M.R.: advisory board and speaker honoraria for Nestlé Nutrition and Abbot Nutrition. Speaker honoraria for Danone Nutricia.

Y.W.: no conflicts of interest.

A.E.: medical advisor and paid honoraria for Nestlé and Danone/Nutricia.

The funders had a role in the design of the survey; and in the analyses, however, they had no role in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAF |

Amino acid formula |

| CMA |

Cow’s milk allergy |

| CMP |

Cow’s Milk Protein |

| CoMISS |

Cow’s millk-related symptoms score |

| eHF |

Extensively hydrolysed formula |

| ESPGHAN |

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| HCP |

Healthcare Professional |

| HRF |

Hydrolysed rice formula |

| Ig |

Immunoglobulin |

| OFC |

Oral food challenge |

| pHF-W |

Partially hydrolysed whey protein formula |

| WAO |

World Allergy Organization |

| WHO |

World Health Orgnisation |

References

- Sathya P, Fenton TR. Cow's milk protein allergy in infants and children. Paediatr Child Health 2024, 29, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognanni A, Fiocchi A, Arasi S, et al. World allergy organization (wao) diagnosis and rationale for action against cow's milk allergy (dracma) guideline update - xii - recommendations on milk formula supplements with and without probiotics for infants and toddlers with cma. World Allergy Organ J. 2024, 17, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Broekaert I, Domellöf M, et al. An espghan position paper on the diagnosis, management, and prevention of cow's milk allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024, 78, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter C, Meyer R, Groetch M, et al. World allergy organization (wao) diagnosis and rationale for action against cow's milk allergy (dracma) guidelines update - xvi - nutritional management of cow's milk allergy. World Allergy Organ J. 2024, 17, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson HA, Arasi S, Bahnson HT, et al. Aaaai–eaaci practall: Standardizing oral food challenges—2024 update. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2024, 35, e14276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos AF, Riggioni C, Agache I, et al. Eaaci guidelines on the diagnosis of ige-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2023, 78, 3057–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Bajerova K, Dupont C, et al. The cow's milk related symptom score: The 2022 update. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenplas Y, Gerlier L, Caekelbergh K, et al. An observational real-life study with a new infant formula in infants with functional gastro-intestinal disorders. Nutrients. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek JY, Noble L, Section on B. Policy statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization. Fact sheet: Infant and young child feeding: 2023 [Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding. Accessed: February 2025].

- Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, et al. Complementary feeding: A position paper by the european society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition (espghan) committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017, 64, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halken S, Muraro A, de Silva D, et al. Eaaci guideline: Preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update). Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2021, 32, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenplas Y, Al-Hussaini B, Al-Mannaei K, et al. Prevention of allergic sensitization and treatment of cow's milk protein allergy in early life: The middle-east step-down consensus. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gappa M, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Libuda L, et al. Long-term effects of hydrolyzed formulae on atopic diseases in the gini study. Allergy. 2021, 76, 1903–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajewska H, Horvath A. A partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula and the risk of eczema and any allergy: An updated meta-analysis. World Allergy Organ J. 2017, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Schulz H, et al. Allergic manifestation 15 years after early intervention with hydrolyzed formulas--the gini study. Allergy. 2016, 71, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeaud C, Guillet J, Sandler B. Gastric emptying in infants with or without gastro-oesophageal reflux according to the type of milk. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990, 44, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Bongers ME, de Lorijn F, Reitsma JB, et al. The clinical effect of a new infant formula in term infants with constipation: A double-blind, randomized cross-over trial. Nutr J. 2007, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exl BM, Deland U, Secretin MC, et al. Improved general health status in an unselected infant population following an allergen-reduced dietary intervention programme: The zuff-study-programme. Part ii: Infant growth and health status to age 6 months. Zug-frauenfeld. Eur J Nutr. 2000, 39, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino F, Maccario S, Castagno E, et al. Advances in the management of digestive problems during the first months of life. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2005, 94, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savino F, Palumeri E, Castagno E, et al. Reduction of crying episodes owing to infantile colic: A randomized controlled study on the efficacy of a new infant formula. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006, 60, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuo C, Tanaka K, Suzuki S, et al. Oral immunotherapy using partially hydrolyzed formula for cow's milk protein allergy: A randomized, controlled trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018, 177, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro PG, Kjellman NI, Oldaeus G, et al. Hypoallergenicity of an extensively hydrolyzed whey formula. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001, 12, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Belohlavkova S, Enninger A, et al. How are infants suspected to have cow’s milk allergy managed? A real world study report. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrazo JA, Alrefaee F, Chakrabarty A, et al. International cross-sectional survey among healthcare professionals on the management of cow's milk protein allergy and lactose intolerance in infants and children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2022, 25, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira SCF, Santos VS, Franco JM, et al. Brazilian pediatricians' adherence to food allergy guidelines-a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granot M, Machnes Maayan D, Weiss B, et al. Practice variations in the management of infants with non-ige-mediated cow's milk protein allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022, 75, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manasfi H, Hanna-Wakim R, Akel I, et al. Questionnaire-based survey in a developing country showing noncompliance with paediatric gastro-oesophageal reflux practice guidelines. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Brough HA, Fiocchi A, et al. Current guidelines and future strategies for the management of cow's milk allergy. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 1243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Belohlavkova S, Enninger A, et al. How are infants suspected to have cow's milk allergy managed? A real world study report. Nutrients. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser B, Blecker U, Keymolen K, et al. Plasma amino acid concentrations in term-born infants fed a whey predominant or a whey hydrolysate formula. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997, 21, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Hauser B, Blecker U, et al. The nutritional value of a whey hydrolysate formula compared with a whey-predominant formula in healthy infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993, 17, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Opinion of the scientific panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies [nda] related to the safety and suitability for particular nutritional use by infants of formula based on whey protein partial hydrolysates with a protein content of at least 1.9 g protein/100 kcal. EFSA Journal. 2005, 3, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzehak P, Sausenthaler S, Koletzko S, et al. Long-term effects of hydrolyzed protein infant formulas on growth--extended follow-up to 10 y of age: Results from the german infant nutritional intervention (gini) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011, 94 (Suppl. 6), 1803S–1807S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzehak P, Sausenthaler S, Koletzko S, et al. Short- and long-term effects of feeding hydrolyzed protein infant formulas on growth at < or = 6 y of age: Results from the german infant nutritional intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkies LA, Kineman BD, Cohen SS, et al. A pooled analysis of growth and tolerance of infants exclusively fed partially hydrolyzed whey or intact protein-based infant formulas. Int J Pediatr. 2018, 2018, 4969576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdeau T, Affolter M, Dupuis L, et al. Peptide characterization and functional stability of a partially hydrolyzed whey-based formula over time. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Auria E, Salvatore S, Acunzo M, et al. Hydrolysed formulas in the management of cow's milk allergy: New insights, pitfalls and tips. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (cross). J Gen Intern Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).