1. Introduction

Neonatal neuroinflammation is a central driver of acute brain injury and adverse neurodevelopmental trajectories in both preterm and term infants, arising from coordinated crosstalk among microglia, cytokine networks, and intracellular signaling pathways [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Inflammatory injury to the developing brain is a critical complication that can occur before, during, or after a brain injury, leading to direct cellular damage, disruption of neurodevelopmental processes, and long-term neurological sequelae such as cerebral palsy [

5,

6,

7]. Perinatal infection, hypoxia-ischemia, or other stressors can trigger systemic upregulation of inflammatory cytokines and activation of resident immune cells known as microglia [

5,

8,

9]. Microglia—the resident immune cells of the brain—initiate inflammatory programs that are adaptive when transient but become pathological when activation is prolonged or dysregulated, shifting toward an inflammatory primed state that exacerbates neuronal dysfunction through sustained release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species [

2,

10,

11]. These inflammatory cascades extend beyond parturition, shaping neonatal organ injury—including that of the brain—and establishing trajectories of long-term neurodevelopmental risk [

3,

12,

13,

14].

In preterm infants, early inflammatory exposure can shift microglia toward a hyper-responsive inflammatory “primed” state that overreacts to subsequent stimuli and adopts a neurotoxic phenotype, resulting in persistent vulnerability to neurodevelopmental impairment [

15,

16,

17]. Under normal conditions, microglia play essential roles in synaptic pruning, circuit refinement, and axonal guidance through complement-mediated synapse elimination; however, inflammation priming during these critical developmental windows can disrupt these processes and impair circuit maturation [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Consistent with this framework, neuroimaging studies in preterm cohorts have identified MRI biomarkers of microglia-linked neuroinflammatory injury, including reduced cortical gyrification, diminished cortical thickness, and delayed maturation of white-matter microstructure [

23,

24,

25]. Neuroinflammatory processes associated with preterm birth are most strongly linked to white-matter injury and cerebral palsy, whereas perinatal conditions such as chorioamnionitis and systemic neonatal infection

associated with increased risks of cognitive, motor, and language impairments [

7,

26,

27,

28].

Oxytocin (OT) is a hypothalamic nonapeptide produced in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei that signals through the widely distributed oxytocin receptor (OXTR) to regulate neuroendocrine function, autonomic tone, and socio-affective behavior. [

29,

30]. Emerging preclinical evidences indicate that OT exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in microglia: OT pretreatment reduces lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation, suppresses pro-inflammatory mediator release, and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation and p38 MAPK in an OXTR-dependent manner [

30,

31,

32,

33]. These findings suggest that OT may serve as an endogenous regulator of microglial inflammatory priming. However, its mechanistic role in preterm neuroinflammation—particularly on interleukin-6 (IL-6), COX-2, and IL-17-linked pathways—remains unclear. Although OT is not routinely administered to preterm infants, its potential neuroprotective effects under conditions of procedural pain and stress are under active investigation [

29,

34]. In preterm infants, exposure to maternal voice and touch immediately before an inflammatory or painful trigger has been associated with activation of the infant OT system, as evidenced by lower pain scores and increased salivary OT concentration[

35]. Yet, clinical findings remain inconsistent across studies [

34], likely due to variability in OT dose, formulation, and treatment duration, as well as unresolved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues in pediatric use [

36,

37].

We therefore sought to examine how OT pretreatment modulates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 microglia, integrating classical inflammatory readouts with transcriptomic profiling to evaluate OT as a physiological brake on microglial hypersensitivity.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

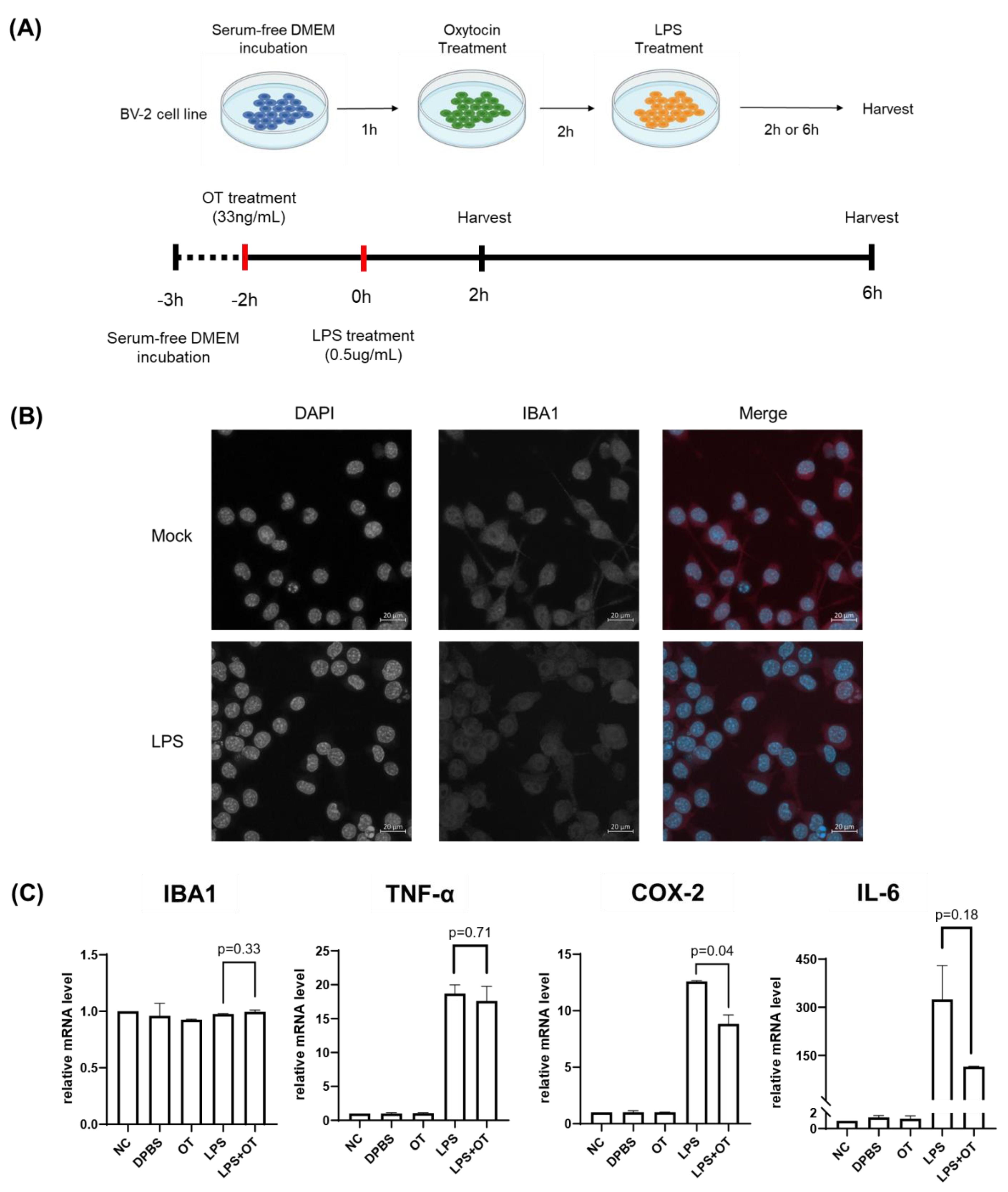

BV-2 murine microglial cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, at 37 °C in a CO₂ incubator. One hour before OT treatment, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM. Cells were preincubated with OT (33ng/mL) for 2 hours and subsequently stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 0.5 µg/mL) for an additional 2 hours under serum-free conditions. For time-course experiments, cells were harvested 2 and 6 hours after LPS treatment to evaluate temporal changes in gene expression.

Immunofluorescence staining

BV-2 cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 hours. The seeded cells were then washed with DPBS and fixed with 3.8% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes. Next, the cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 and blocked with 2% normal goat serum (NGS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-IBA1 antibody (Abcam, ab178846) diluted in 0.1% NGS, rinsed with DPBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor™ 647–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A-31573) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were mounted with Antifade Mounting Medium containing DAPI (VECTASHIELD®, H-1200). Confocal images were acquired by a Zeiss LSM 900 microscope. Samples processed without primary antibody were used as negative controls to determine non-specific staining.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Easy-Spin™ Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was prepared with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). qPCR was performed with SYBR Green chemistries on a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Optics Module). GAPDH was used as the internal reference gene for quantifying the relative gene expression based on the observed Ct values.

Transcriptome analysis by mRNA sequencing

The quality of RNA extracted from BV-2 microglial cells were assessed using an Agilent TapeStation D1000 system. RNAs that passed the quality score were utilized to prepare mRNA sequencing libraries using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina platform to generate 150 bp paired-end sequencing reads. The raw sequencing reads were quality-checked and trimmed prior to alignment. Trimmed sequence reads were aligned to Ensembl mouse genome version 38 (GRCm38) with HISAT2. Gene expression levels were quantified using htseq-count, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were discovered using DESeq2 R package.

KEGG pathway and Gene Ontology enrichment analysis

Mouse gene annotation was performed using org.Mm.eg.db v3.21.0. DEGs with adjusted p-value below 0.05 were subjected for enrichment analysis using clusterProfiler R package. KEGG pathways were retrieved from KEGG release 116.0 (2025-10-01). GO enrichment was conducted for the Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) ontologies. The p values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Dot plots summarize the GeneRatio, adjusted p values, and term gene counts.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were conducted with two or more independent biological replicates. Differences in the gene expression levels were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Error bars in the box plots indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Oxytocin Pretreatment in Immune Response of BV-2 Cells to Lipopolysaccharide

To assess the modulatory effect of oxytocin (OT) on microglial inflammatory responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), we sought to analyze the changes in gene expression patterns in BV-2 microglia cells in response to OT and LPS treatment.

To this end, we first established a primed microglial state without provoking excessive inflammatory activation. We conducted immunofluorescence to observed that BV-2 cells showed robust expression levels of IBA1, a microglia marker, consistent with the glial characteristics (

Supplementary Figure S1). We assessed the IBA1 expression levels in BV-2 cell within a range of LPS doses (0.1–100 μg/mL), and found that IBA1 levels remained stable at low to moderate concentrations of LPS concentration up to around 30 μg/mL (

Supplementary Figure S1). Based on this, we selected 0.5 μg/mL as an adequate LPS concentration for inducing LPS-dependent transcriptional priming.

To assess how OT may affect the response of BV-2 cells to LPS, we analyzed the gene expression levels of BV-2 cells that were pretreated with OT (33ng/mL) for 2 hours prior to LPS (0.5 µg/mL) stimulation (

Figure 1A). After LPS stimulation, RNA from the cells were harvested at 2 and 6 hours for downstream analyses. Immunofluorescence analyses showed that IBA1 expressions were consistent in suggesting that the BV-2 cells maintained the glial cell characteristics in after treatment of both OT and LPS (

Figure 1B).

Next, we conducted RT-qPCR to analyze the expression levels of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2 under the five experimental conditions: negative control (NC), DPBS vehicle, OT alone, LPS alone, and LPS with OT pretreatment (

Figure 1C). Compared with NC, LPS treatment increased three markers: IL-6, COX-2, and TNF-α showed marked elevations. On the other hand, IBA1 expression levels remained relatively stable across all groups, with only minor variation around baseline levels and no statistically significant differences among conditions (p = 0.33). Interestingly, comparison between LPS and LPS + OT showed a significant reduction in COX-2 expression following OT pretreatment (p = 0.04). In addition, IL-6 exhibited a marked downward trend although the difference was not statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.18). TNF-α and IBA1 expression levels did not differ significantly between these two groups (p = 0.71 and p = 0.33, respectively). The results suggested that OT pretreatment partly blunted the LPS response: COX-2 was significantly reduced, IL-6 showed a downward trend, while TNF-α and IBA1 were essentially unchanged.

To determine whether these transcriptional effects persisted over time, the identical experimental conditions were applied at a 6-hour post-stimulation time point (

Supplementary Figure 2). Gene expression patterns at 6 hours broadly similar to those observed at 2 hours: OT pretreatment resulted in notable decrease of COX-2 and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated cells. The reduction of IL-6 was significant in the 6-hour analyses. Also similar to 2 hours analyses,

IBA1 and TNF-α displayed a similar expression level irrespective of OT pretreatment.

3.2. Transcriptome Analyses under OT Pretreatment

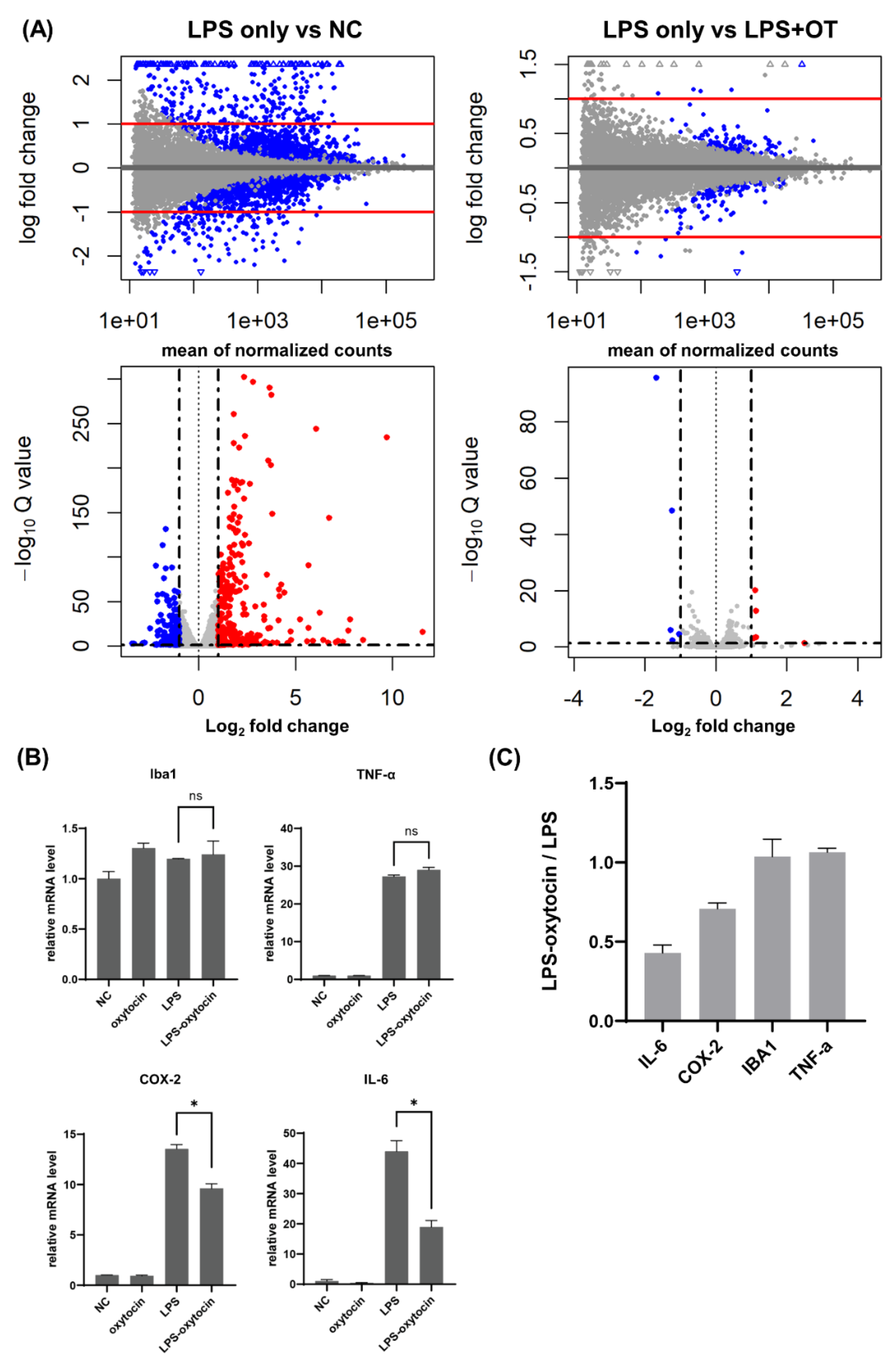

Next, we examined how OT pre-treatment modulates the RNA expression profiles following LPS treatment. To this end, we conducted RNA sequencing of BV-2 cells after treatment of LPS, with or without OT pre-incubation (

Figure 2A). RNA integrity and library quality were first confirmed using the Agilent TapeStation D1000 system, which showed clear peaks between 200–400 bp across all samples, consistent with high-quality library preparation (

Supplementary Figure 3).

The transcriptome analyses showed that LPS treatment resulted in overall changes in gene expression profile of BV-2 cells compared to non-treated condition. In the LPS vs. NC contrast, a broad set of genes was significantly up- or downregulated, producing a wide vertical spread on MA/volcano plots with many transcripts surpassing log₂ fold-change and adjusted Q-value thresholds.

As the RT-qPCR analyses showed that the upregulation of COX-2 and IL-6 could be suppressed by OT, we sought to ask what genes were regulated by OT treatment after LPS stimutation. To this end, we compared the RNA-seq data between LPS-only and OT-LPS conditions and found a group of genes that were decreased by pretreatment of OT before LPS stimulation (

Figure 2A). In contrast to the LPS vs NC analyses, the LPS vs. LPS + OT comparison revealed only a small subset of DEGs, with a visible narrowed log₂ fold-change range and reduced dispersion along the Q-value axis. Most transcripts remained close to baseline, showing that OT pretreatment contracted both the amplitude and the statistical strength of the LPS-driven proinflammatory transcriptome. In summary, LPS inherently elicits a broad, high-intensity proinflammatory transcriptome, whereas OT pretreatment constrains this program by reducing both its breadth and its amplitude, consistent with an anti-priming or “brake” effect.

Expression levels of the representative inflammatory genes (IL-6, COX-2, IBA1, and TNF-α) were extracted from the RNA-seq data and visualized in

Figure 2B. IL-6 and COX-2 were robustly induced by LPS, with mRNA levels markedly higher than in control or OT-only cultures, but both were clearly reduced in the LPS + OT condition. By contrast, IBA1 and TNF-α showed no significant differences between LPS only and LPS + OT and remained comparable across these two groups, indicating lower sensitivity to OT pretreatment under the same conditions Consistently, normalized expression relative to LPS only group demonstrated that IL-6 and COX-2 were more strongly downregulated than TNF-α and IBA1 in the LPS + OT group, indicating a selective dampening of LPS-induced inflammatory transcripts (

Figure 2C).

3.3. Pathway Enrichment and Orthogonal Validation

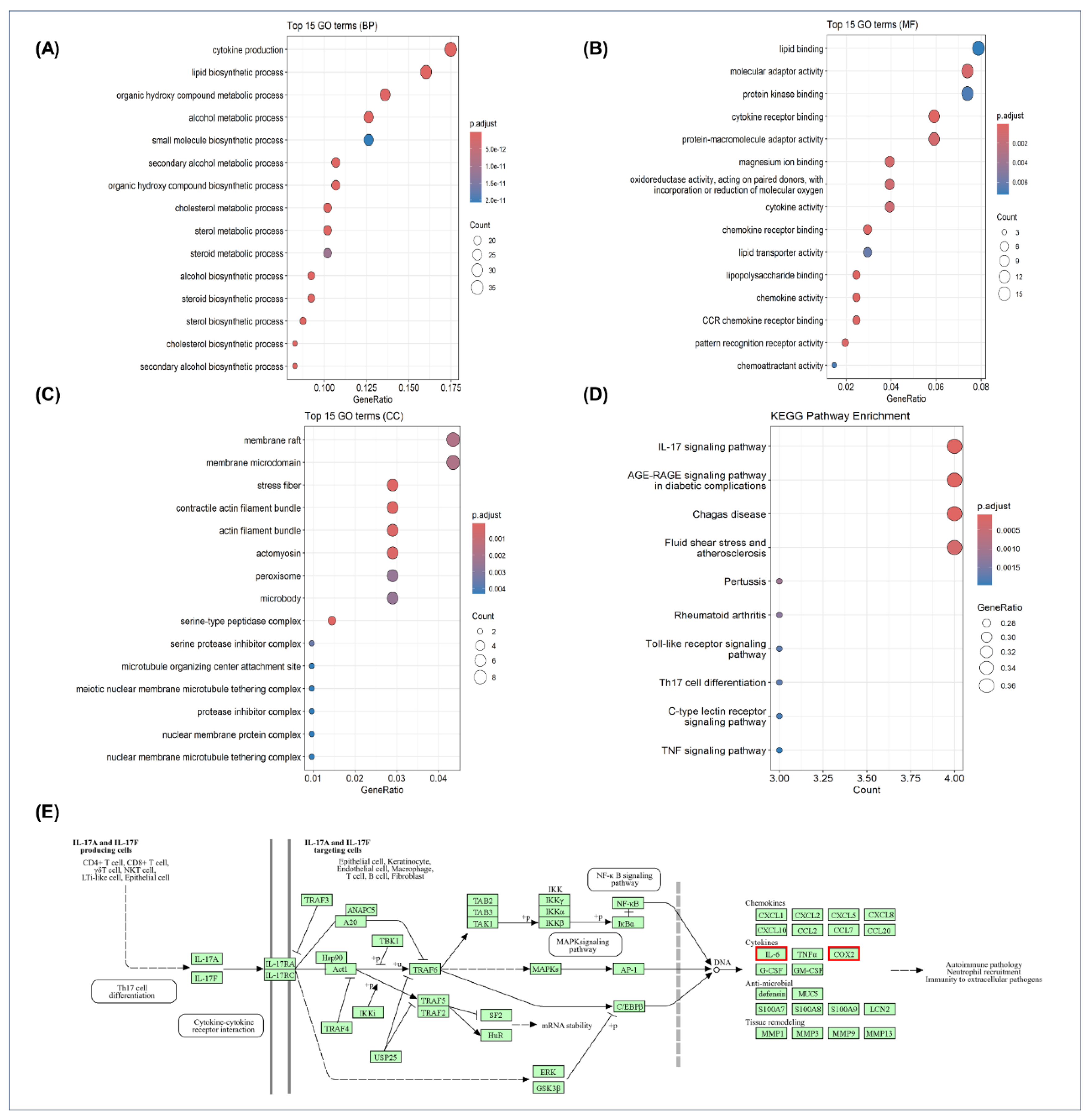

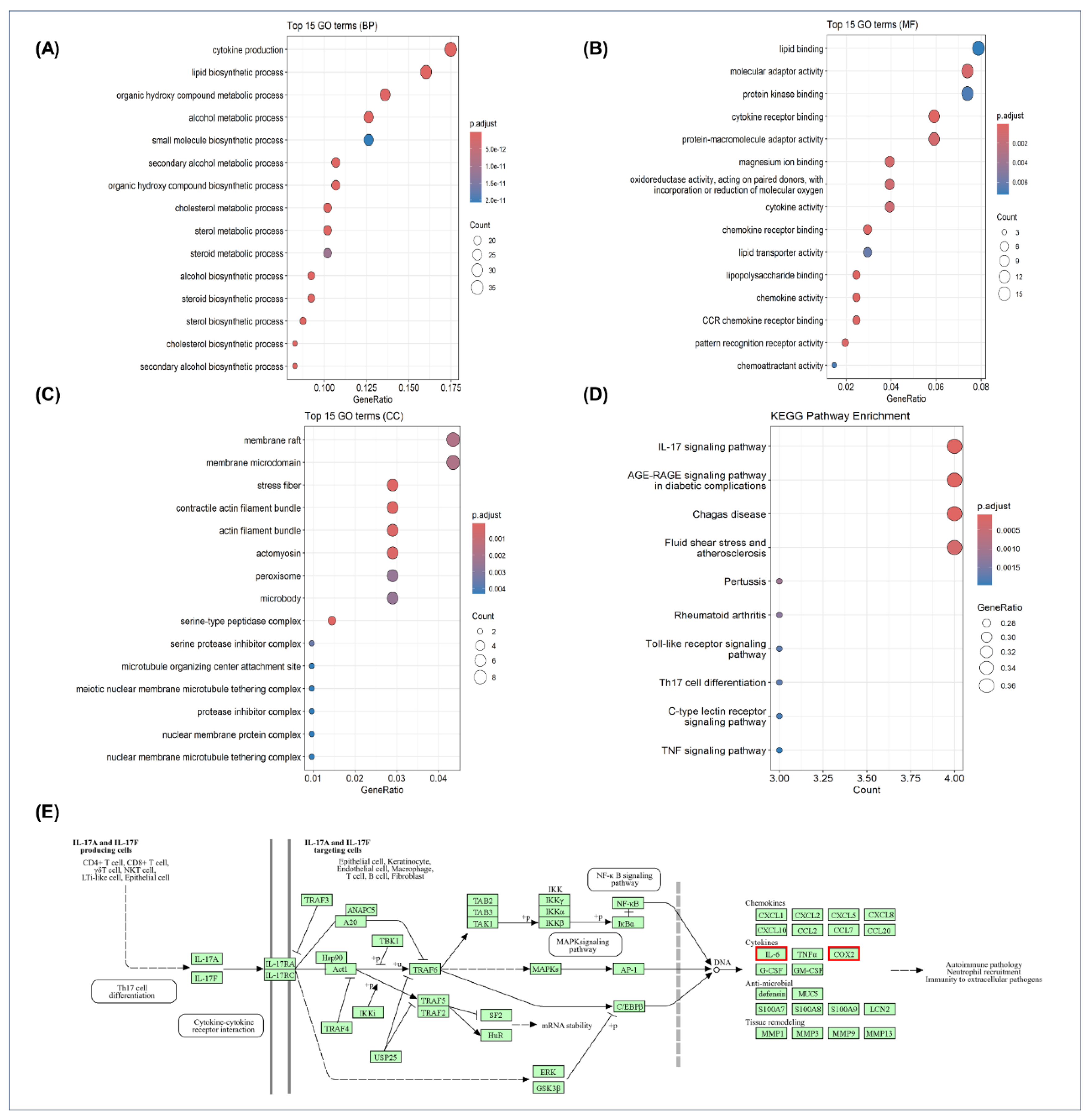

Enrichment analyses of DEGs from oxytocin-pretreated BV-2 microglia showed a consistent pattern of transcriptional modulation across biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), cellular components (CC), and signaling pathways (KEGG) (

Figure 3). In the GO BP category (

Figure 3A), enriched terms were dominated by cytokine production, lipid biosynthetic process, cholesterol metabolic process, steroid biosynthetic process, and organic hydroxy compound metabolic process, indicating broad transcriptional changes across inflammatory and metabolic programs. In the MF category (

Figure 3B), enrichment of lipid binding, cytokine (receptor) binding, and chemokine receptor binding pointed to coordinated modulation of receptor–ligand and lipid-associated functions. The CC category (

Figure 3C) included membrane rafts/microdomains, cytoskeletal structures (stress fibers, actin filament bundles, actomyosin), and metabolic organelles (peroxisomes), showing that oxytocin-responsive genes localized to membrane, cytoskeletal, and metabolic compartments. KEGG analysis (

Figure 3D) further revealed downregulation of canonical inflammatory pathways, most prominently IL-17 signaling, followed by TNF and Toll-like receptor signaling. Together, these data define a coherent transcriptional signature whereby oxytocin pretreatment reshapes immune, metabolic, and structural gene networks in LPS-stimulated BV-2 microglia.

The enrichment of OT-modulated genes in this pathway suggests a targeted modulation of inflammation-related transcriptional programs by OT. A schematic representation of the IL-17 signaling pathway is shown in

Figure 3E (

https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/hsa04657), highlighting key downstream targets such as IL-6 and COX-2, which were among the major OT-responsive genes identified in our dataset and significantly downregulated by OT pretreatment. In addition, a list of the top OT-downregulated DEGs—including Nr4a1—is provided in

Supplementary Table 2, selected on the basis of their differential expression and their reported roles in inflammatory and microglial regulatory pathways.

4. Discussion

In an in vitro model of LPS-induced inflammatory response in BV2 microglia, OT pretreatment attenuated the inflammatory response, as demonstrated by transcriptomic and qPCR analyses. OT significantly reduced IL-6 and COX-2 expression. Moreover, differentially down-regulated genes were most significantly enriched in IL-17 signaling pathway. These findings suggest that OT modulates microglial reactivity by constraining the IL-17–IL-6/COX-2 axis, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory transcriptional activity without broad immunosuppression.

In LPS-challenged BV-2 microglia, OT pretreatment downregulated IL-6 and COX-2 transcripts, whereas TNF-α showed only a modest, non-significant decrease. This pattern accords with prior reports in rodent microglial—spanning BV-2 lines and primary microglia—showing that exogenous OT or oxytocin-receptor agonism attenuated LPS-evoked IL-6 and COX-2 induction [

31,

32,

33]. IL-6 increases with microglial activation and contributes to neurotoxicity when sustained, and COX-2–dependent eicosanoid signaling sustains inflammatory circuits that compromise synaptic and neuronal integrity [

38,

39]. In the early phase of perinatal inflammation, IL-6 rises rapidly across the placenta–fetal compartments tending to be higher in preterm labor. Amniotic and cervicovaginal IL-6 levels have been linked with preterm birth and are elevated in in cases of preterm labor associated with histologic chorioamnionitis. In addition, time-course studies indicate that IL-6 peaks across maternal, placental, and fetal tissues within the first few hours after an inflammatory trigger [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Elevated IL-6 is closely associated with preterm birth and early-life neuroinflammatory risk [

41,

45], with preterm infants showing higher cerebrospinal fluid IL-6 levels when MRI-defined white-matter injury is present at term-equivalent age [

46]. Clinical studies such as the ELGAN cohort further demonstrate that sustained postnatal inflammation, including elevated IL-6, correlates with long-term cognitive and motor impairments [

47]. Similarly, COX-2 is upregulated in placental and fetal tissues during chorioamnionitis and is inducible in the preterm brain following intra-amniotic LPS exposure [

48,

49]. Moreover, COX-2/PGE₂ signaling within microglia and endothelial cells disrupts oligodendrocyte maturation and contributes to white-matter injury in developing human shite matter [

50]. Collectively, these perinatal data together with our transcriptomic findings support an OT-sensitive IL-6/COX-2 axis as a biologically coherent mechanism that tempers microglial inflammatory tone without global transcriptional suppression [

31,

32,

33].

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified multiple components of the IL-17 signaling pathway—including Il6 and COX-2—among OT-responsive genes. The canonical IL-17RA/RC–ACT1–TRAF6 axis activates NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPK signaling [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Consistent with this, GO enriched terms- cytokine production, receptor binding, chemokine activity, and lipid biosynthesis- indicates the functional output of IL-17 pathway activation. This GO profile suggests a cytokine-focused regulatory effect on inflammatory priming, rather than a global transcriptional suppression, indicating a selective modulation of the IL-6/COX-2 axis. Our RT-qPCR data demonstrated this interpretation, demonstrating targeted suppression of IL-17–linked inflammatory outputs rather than generalized inhibition of TLR4-proximal responses.

Intrauterine infection/inflammation is a major driver of preterm labor, with IL-6 serving as a key mediator at the maternal–fetal interface [

56]. Increasing evidence implicates the IL-17/Th17 axis in these processes: IL-17 concentrations are elevated in amniotic fluid, IL-17–producing CD3⁺CD4⁺ T cells accumulate in chorioamniotic membranes during preterm labor, and cord-blood Th17 signatures are enhanced in preterm neonates exposed to histologic chorioamnionitis [

57,

58,

59]. Mechanistically, IL-17 synergizes with TNF-α to upregulate COX-2 and PGE₂, and PGE₂ which in turn amplify Th17 responses, establishing a feed-forward loop that can reinforce microglial inflammatory reactivity via NF-κB/MAPK pathways [

60,

61,

62,

63] Thus, our findings suggest a model in which OT selectively mitigates IL-17–IL-6/COX-2–driven inflammation acting as a physiological counter-regulator.

Human neonatal studies suggest that, in the absence of intrauterine inflammation, preterm infants typically exhibit lower IL-17A levels and reduced Th17 activity compared with term infants [

64,

65,

66,

67]. However, when intrauterine inflammation such as histologic chorioamnionitis is present, amplified Th17-type responses are observed. This demonstrates that the IL-17/Th17 axis is augmented in response to inflammation [

3,

58]. Dysregulated IL-17 signaling has been linked to multiple neonatal morbidities—including sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, patent ductus arteriosus, and necrotizing enterocolitis—highlighting its developmental relevance [

13]. Moreover, IL-17A has direct neurodevelopmental effects: maternal IL-17A exposure in mice disrupts cortical morphogenesis and produces aberrant neurobehavioral phenotypes, highlighting that this pathway can strongly influence the brain during sensitive developmental windows [

12,

68,

69]. In parallel, emerging evidence indicates that IL-17 signaling drives microglial state transitions and directly activates cortical microglia in the embryonic brain, influencing developmental circuit formation [

70]. Reviews further note that microglia express IL-17RA and can proliferate, migrate, and activate in the setting of sustained IL-17A [

71]. Together, these findings underscore a mechanistic framework in which OT dampens the IL-17–IL-6/COX-2 axis during early neurodevelopmental windows, preventing maladaptive microglial programming that may underlie later circuit dysfunction.

Transcriptome profiling further revealed that OT pretreatment reduced the overall transcriptional response and markedly reduced the immediate-early transcription factor Nr4a1, a key regulator positioned at the AP-1–NF-κB interface [

72,

73] and functionally intersects with IL-17–leveraged modules [

53,

55,

74]. In our data, OT lowered Nr4a1 in parallel with IL-6/COX-2, suggesting that OT rebalances an Nr4a1-centered early-response network to modulate IL-17-linked outputs without broadly suppressing the LPS program [

31,

33,

55]. In vivo studies likewise indicate that OT selectively attenuates specific inflammatory subsets, reduces microglial activation, and preserves synaptic integrity[

32,

75] implicating Nr4a1 as a key mechanistic node linking OT signaling to the IL-17–associated IL-6/COX-2 pathway [

21,

76].

Some limitations should be noted. This study utilized an immortalized BV-2 cell line, which may not fully capture primary microglial phenotypes. Mechanistic specificity was inferred rather than directly demonstrated, as receptor-level engagement and targeted perturbation of the IL-17 pathway were not performed. Furthermore, analyses focused on transcript-level changes; future work should include protein validation and functional assays of microglial behavior. Dose–response relationships and post-treatment effects were not evaluated, and in vivo pharmacokinetics and developmental timing should be explored in follow-up studies.

5. Conclusions

In BV-2 microglia, OT pretreatment attenuated LPS-induced inflammatory activation, characterized by decreased IL-6 and COX-2 expressions and suppression of IL-17–associated cytokine and chemokine modules identified through KEGG and GO enrichment analyses. These findings suggest that OT pretreatment specifically modulates the IL-17–IL-6/COX-2 axis rather than exerting broad transcriptional shutdown. This, in turn, supports the hypothesis that OT can function as an endogenous regulator that lowers the microglial inflammatory set-point during the early stages of developmental microglial priming, consistent with the dependence of IL-17 signaling on developmental stage and the perinatal elevation of IL-6 and COX-2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: Optimization of LPS concentration for IBA1; Table S1: Top differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-seq.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.L., W.C.H., and J.H.H.; methodology, W.C.H. and J.H.H.; software, W.C.H.; validation, Y.H.J. and J.Y.H.; formal analysis, J.Y.H. and S.Y.K.; resources, J.Y.H. and J.H.H.; data curation, J.Y.H. and S.Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.J., J.Y.H., J.H.H., and H.J.L.; visualization, J.Y.H.; supervision, J.H.H., and H.J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-NR076663, RS-2021-NR056589, RS-2023-00261114, RS-2025-02218918) to J.K.H, and RS-2023-00260529 to W.H. This work was also supported by the Korea US Collaborative Research Fund (RS-2024-00468036) to J.K.H, RS-2025-16063805 to W.H, and Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (2023R1A6C101A009). This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under RS-2023-NR077125.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OT |

Oxytocin |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| IL-17 |

Interleukin-17 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| BV-2 |

BV-2 microglial cell line |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor (alpha) |

| qPCR |

Quantitative PCR |

| IBA1 |

Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 |

| DPBS |

Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| MAPK |

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| AP-1 |

Activator Protein-1 |

| DEGs |

Differentially Expressed Genes |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO |

Gene Ontology |

References

- Fleiss, B.; Van Steenwinckel, J.; Bokobza, C.; K. Shearer, I.; Ross-Munro, E.; Gressens, P. Microglia-mediated neurodegeneration in perinatal brain injuries. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet Neurology 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humberg, A.; Fortmann, I.; Siller, B.; Kopp, M.V.; Herting, E.; Göpel, W.; Härtel, C.; German Neonatal Network, G.C.f.L.R.; Consortium, P.I.a.t.b.o.l. Preterm birth and sustained inflammation: consequences for the neonate. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Immunopathology; 2020; pp. 451–468. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Translational neurodegeneration 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, H.; Mallard, C.; Ferriero, D.M.; Vannucci, S.J.; Levison, S.W.; Vexler, Z.S.; Gressens, P. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nature Reviews Neurology 2015, 11, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatrov, J.G.; Birch, S.C.; Lam, L.T.; Quinlivan, J.A.; McIntyre, S.; Mendz, G.L. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2010, 116, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.W.; Colford Jr, J.M. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Jama 2000, 284, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallard, C.; Tremblay, M.-E.; Vexler, Z.S. Microglia and neonatal brain injury. Neuroscience 2019, 405, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrock, J.E.; Panchapakesan, K.; Vezina, G.; Chang, T.; Harris, K.; Wang, Y.; Knoblach, S.; Massaro, A.N. Association of brain injury and neonatal cytokine response during therapeutic hypothermia in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatric research 2016, 79, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannes, N.; Eppler, E.; Etemad, S.; Yotovski, P.; Filgueira, L. Microglia at center stage: a comprehensive review about the versatile and unique residential macrophages of the central nervous system. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 114393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, M.W.; Stevens, B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nature medicine 2017, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.B.; Yim, Y.S.; Wong, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.V.; Hoeffer, C.A.; Littman, D.R.; Huh, J.R. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 2016, 351, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.M.; Ruoss, J.L.; Wynn, J.L. IL-17 in neonatal health and disease. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2018, 79, e12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin Yim, Y.; Park, A.; Berrios, J.; Lafourcade, M.; Pascual, L.M.; Soares, N.; Yeon Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Waisman, A. Reversing behavioural abnormalities in mice exposed to maternal inflammation. Nature 2017, 549, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbo, S.D.; Schwarz, J.M. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2009, 3, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.N.; Barbosa-Silva, M.C.; Maron-Gutierrez, T. Microglial priming in infections and its risk to neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2022, 16, 878987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastenbroek, L.; Kooistra, S.; Eggen, B.; Prins, J. The role of microglia in early neurodevelopment and the effects of maternal immune activation. In Proceedings of the Seminars in immunopathology; 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Mechanisms and significance of microglia–axon interactions in physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2021, 78, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, D.P.; Lehrman, E.K.; Kautzman, A.G.; Koyama, R.; Mardinly, A.R.; Yamasaki, R.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Greenberg, M.E.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 2012, 74, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteros, B.M.; Sia, G.M. Complement and microglia dependent synapse elimination in brain development. WIREs mechanisms of disease 2022, 14, e1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarzoni, P.; Oller, G.; Hoeffel, G.; Pont-Lezica, L.; Rostaing, P.; Low, D.; Bessis, A.; Ginhoux, F.; Garel, S. Microglia modulate wiring of the embryonic forebrain. Cell reports 2014, 8, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, B.; Allen, N.J.; Vazquez, L.E.; Howell, G.R.; Christopherson, K.S.; Nouri, N.; Micheva, K.D.; Mehalow, A.K.; Huberman, A.D.; Stafford, B. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell 2007, 131, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibble, M.; Ang, J.Z.; Mariga, L.; Molloy, E.J.; Bokde, A.L. Diffusion tensor imaging in very preterm, moderate-late preterm and term-born neonates: a systematic review. The Journal of pediatrics 2021, 232, 48–58. e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.E.; Thompson, D.K.; Adamson, C.L.; Ball, G.; Dhollander, T.; Beare, R.; Matthews, L.G.; Alexander, B.; Cheong, J.L.; Doyle, L.W. Cortical growth from infancy to adolescence in preterm and term-born children. Brain 2024, 147, 1526–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, C.; Palaniyappan, L.; Kroll, J.; Froudist-Walsh, S.; Murray, R.M.; Nosarti, C. Altered cortical gyrification in adults who were born very preterm and its associations with cognition and mental health. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Thompson, D.K.; Anderson, P.J.; Yang, J.Y.-M. Short-and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of very preterm infants with neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children 2019, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussenhoven, R.; Westerlaken, R.J.; Ophelders, D.R.; Jobe, A.H.; Kemp, M.W.; Kallapur, S.G.; Zimmermann, L.J.; Sangild, P.T.; Pankratova, S.; Gressens, P. Chorioamnionitis, neuroinflammation, and injury: timing is key in the preterm ovine fetus. Journal of neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Ma, L.; Luo, K.; Bajaj, M.; Chawla, S.; Natarajan, G.; Hagberg, H.; Tan, S. Chorioamnionitis in the development of cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pediatrics 2017, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.S.; Kenkel, W.M.; MacLean, E.L.; Wilson, S.R.; Perkeybile, A.M.; Yee, J.R.; Ferris, C.F.; Nazarloo, H.P.; Porges, S.W.; Davis, J.M. Is oxytocin “nature’s medicine”? Pharmacological reviews 2020, 72, 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, B.; Neumann, I.D. The oxytocin receptor: from intracellular signaling to behavior. Physiological reviews 2018, 98, 1805–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Yamakage, H.; Tanaka, M.; Kusakabe, T.; Shimatsu, A.; Satoh-Asahara, N. Oxytocin suppresses inflammatory responses induced by lipopolysaccharide through inhibition of the eIF-2α–ATF4 pathway in mouse microglia. Cells 2019, 8, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selles, M.C.; Fortuna, J.T.; de Faria, Y.P.; Siqueira, L.D.; Lima-Filho, R.; Longo, B.M.; Froemke, R.C.; Chao, M.V.; Ferreira, S.T. Oxytocin attenuates microglial activation and restores social and non-social memory in APP/PS1 Alzheimer model mice. Iscience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Hao, A.; Wang, Z. Oxytocin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in microglial cells and attenuates microglial activation in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. Journal of neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Schmid, U.; Morgado, A.; Heim, C.; Klawitter, H.; Hellmeyer, L.; Entringer, S. Oxytocin in prematurely born infants and their parents-a systematic review with clinical implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2025, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippa, M.; Monaci, M.G.; Spagnuolo, C.; Serravalle, P.; Daniele, R.; Grandjean, D. Maternal speech decreases pain scores and increases oxytocin levels in preterm infants during painful procedures. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBois, M.; Tseng, A.; Francis, S.M.; Haynos, A.F.; Peterson, C.B.; Jacob, S. Utility of downstream biomarkers to assess and optimize intranasal delivery of oxytocin. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikich, L.; Kolevzon, A.; King, B.H.; McDougle, C.J.; Sanders, K.B.; Kim, S.-J.; Spanos, M.; Chandrasekhar, T.; Trelles, M.P.; Rockhill, C.M. Intranasal oxytocin in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erta, M.; Quintana, A.; Hidalgo, J. Interleukin-6, a major cytokine in the central nervous system. International journal of biological sciences 2012, 8, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.U.; Woodling, N.S.; Wang, Q.; Panchal, M.; Liang, X.; Trueba-Saiz, A.; Brown, H.D.; Mhatre, S.D.; Loui, T.; Andreasson, K.I. Prostaglandin signaling suppresses beneficial microglial function in Alzheimer’s disease models. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermick, J.; Watson, S.; Lueschow, S.; McElroy, S.J. The fetal response to maternal inflammation is dependent upon maternal IL-6 in a murine model. Cytokine 2023, 167, 156210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Li, W.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, X. Association between interleukin-6 and preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine 2023, 55, 2284384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goepfert, A.R.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Andrews, W.W.; Hauth, J.C.; Mercer, B.; Iams, J.; Meis, P.; Moawad, A.; Thom, E.; VanDorsten, J.P. The Preterm Prediction Study: association between cervical interleukin 6 concentration and spontaneous preterm birth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2001, 184, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, P.C.; Ernest, J.; Teot, L.; Erikson, M.; Talley, R. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6 levels correlate with histologic chorioamnionitis and amniotic fluid cultures in patients in premature labor with intact membranes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1993, 169, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Avila, C.; Santhanam, U.; Sehgal, P.B. Amniotic fluid interleukin 6 in preterm labor. Association with infection. The Journal of clinical investigation 1990, 85, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J.P.; Ireland, G.; Sullivan, G.; Pataky, R.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P.; Miron, V. The cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory response to preterm birth. Frontiers in physiology 2018, 9, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, V.J.; Mocatta, T.J.; Winterbourn, C.C.; Darlow, B.A.; Volpe, J.J.; Inder, T.E. The relationship of CSF and plasma cytokine levels to cerebral white matter injury in the premature newborn. Pediatric research 2005, 57, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Kuban, K.C.; Dammann, O.; Paneth, N.; Fichorova, R.; Hirtz, D.; Leviton, A.; Investigators, E.L.G.A.N.S. Elevated concentrations of inflammation-related proteins in postnatal blood predict severe developmental delay at 2 years of age in extremely preterm infants. The Journal of pediatrics 2012, 160, 395–401. e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Bonifacio, L.; Weinberger, B.; Reddy, P.; Murphy, S.; Romero, R.; Sharma, S. Evidence for interleukin-10-mediated inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin production in preterm human placenta. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2006, 55, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovska, V.; Atta, J.; Kelly, S.B.; Zahra, V.A.; Matthews-Staindl, E.; Nitsos, I.; Moxham, A.; Pham, Y.; Hooper, S.B.; Herlenius, E. Increased prostaglandin E2 in brainstem respiratory centers is associated with inhibition of breathing movements in fetal sheep exposed to progressive systemic inflammation. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13, 841229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiow, L.R.; Favrais, G.; Schirmer, L.; Schang, A.L.; Cipriani, S.; Andres, C.; Wright, J.N.; Nobuta, H.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P. Reactive astrocyte COX2-PGE2 production inhibits oligodendrocyte maturation in neonatal white matter injury. Glia 2017, 65, 2024–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisson, B.; Wang, C.; Pedergnana, V.; Wu, L.; Cypowyj, S.; Rybojad, M.; Belkadi, A.; Picard, C.; Abel, L.; Fieschi, C. An ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 2013, 39, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.S.; Collins, E.S.; FitzGerald, O.M.; Pennington, S.R. New insight into the functions of the interleukin-17 receptor adaptor protein Act1 in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy 2012, 14, 226. [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy, M.J.; Cua, D.J.; Gaffen, S.L. The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaidani, S.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J.; Bulek, K.; Li, X. TRAF regulation of IL-17 cytokine signaling. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, S.; Inohara, N.; Ohmuraya, M.; Tsuneoka, Y.; Yagita, H.; Katagiri, T.; Nishina, T.; Mikami, T.; Funato, H.; Araki, K. IκBζ controls IL-17-triggered gene expression program in intestinal epithelial cells that restricts colonization of SFB and prevents Th17-associated pathologies. Mucosal Immunology 2022, 15, 1321–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presicce, P.; Roland, C.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Cappelletti, M.; Hammons, M.; Miller, L.A.; Jobe, A.H.; Chougnet, C.A.; DeFranco, E.; Kallapur, S.G. IL-1 and TNF mediates IL-6 signaling at the maternal-fetal interface during intrauterine inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1416162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Nakashima, A.; Hidaka, T.; Okabe, M.; Bac, N.D.; Ina, S.; Yoneda, S.; Shiozaki, A.; Sumi, S.; Tsuneyama, K. A role for IL-17 in induction of an inflammation at the fetomaternal interface in preterm labour. Journal of reproductive immunology 2010, 84, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rito, D.C.; Viehl, L.T.; Buchanan, P.M.; Haridas, S.; Koenig, J.M. Augmented Th17-type immune responses in preterm neonates exposed to histologic chorioamnionitis. Pediatric research 2017, 81, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrachnis, N.; Karavolos, S.; Iliodromiti, Z.; Sifakis, S.; Siristatidis, C.; Mastorakos, G.; Creatsas, G. Impact of mediators present in amniotic fluid on preterm labour. in vivo 2012, 26, 799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-k.; Nie, L.; Zhao, Y.-p.; Zhang, Y.-q.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.-s.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, L. IL-17 mediates inflammatory reactions via p38/c-Fos and JNK/c-Jun activation in an AP-1-dependent manner in human nucleus pulposus cells. Journal of translational medicine 2016, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makihara, S.; Okano, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Kariya, S.; Noda, Y.; Higaki, T.; Nishizaki, K. Regulation and characterization of IL-17A expression in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and its relationship with eosinophilic inflammation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2010, 126, 397–400. e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polese, B.; Thurairajah, B.; Zhang, H.; Soo, C.L.; McMahon, C.A.; Fontes, G.; Hussain, S.N.; Abadie, V.; King, I.L. Prostaglandin E2 amplifies IL-17 production by γδ T cells during barrier inflammation. Cell Reports 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumzhum, N.N.; Patel, B.S.; Prabhala, P.; Gelissen, I.C.; Oliver, B.G.; Ammit, A.J. IL-17A increases TNF-α-induced COX-2 protein stability and augments PGE2 secretion from airway smooth muscle cells: impact on β2-adrenergic receptor desensitization. Allergy 2016, 71, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Thang, C.M.; Thanh, L.Q.; Dai, V.T.T.; Phan, V.T.; Nhu, B.T.H.; Trang, D.N.X.; Trinh, P.T.P.; Nguyen, T.V.; Toan, N.T. Immune profiling of cord blood from preterm and term infants reveals distinct differences in pro-inflammatory responses. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 777927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, S.; Surendran, N.; Pichichero, M. Immune responses in neonates. Expert review of clinical immunology 2014, 10, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobini, M.; Mirzaie, S.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Zainodini, N.; Sabzali, Z.; Ghyasi, M.; Mokhtari, M.; Bahramabadi, R.; Hakimi, H.; Ghorban, K. Association of cord blood levels of IL-17A, but not TGF-β with pre-term neonate. Iranian journal of reproductive medicine 2015, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Razzaghian, H.R.; Sharafian, Z.; Sharma, A.A.; Boyce, G.K.; Lee, K.; Da Silva, R.; Orban, P.C.; Sekaly, R.-P.; Ross, C.J.; Lavoie, P.M. Neonatal T helper 17 responses are skewed towards an immunoregulatory interleukin-22 phenotype. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 655027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, H. Advances in the study of IL-17 in neurological diseases and mental disorders. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1284304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.; Hoeffer, C. Maternal IL-17A in autism. Experimental neurology 2018, 299, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Tome, S.; Takei, Y. Intraventricular IL-17A administration activates microglia and alters their localization in the mouse embryo cerebral cortex. Molecular brain 2020, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.M.; Antonson, A.M. At the crux of maternal immune activation: viruses, microglia, microbes, and IL-17A. Immunological Reviews 2022, 311, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.P.; Crean, D. Molecular interactions between NR4A orphan nuclear receptors and NF-κB are required for appropriate inflammatory responses and immune cell homeostasis. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Castrillo, A.; Tontonoz, P. Regulation of macrophage inflammatory gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77. Molecular endocrinology 2006, 20, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenis, D.S.; Medzikovic, L.; van Loenen, P.B.; van Weeghel, M.; Huveneers, S.; Vos, M.; Evers-van Gogh, I.J.; Van den Bossche, J.; Speijer, D.; Kim, Y. Nuclear receptor Nur77 limits the macrophage inflammatory response through transcriptional reprogramming of mitochondrial metabolism. Cell reports 2018, 24, 2127–2140. e2127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, J.; Yamada, D.; Ueta, Y.; Iwai, T.; Koga, E.; Tanabe, M.; Oka, J.-I.; Saitoh, A. Oxytocin reverses Aβ-induced impairment of hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2020, 528, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Bolasco, G.; Pagani, F.; Maggi, L.; Scianni, M.; Panzanelli, P.; Giustetto, M.; Ferreira, T.A.; Guiducci, E.; Dumas, L. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. science 2011, 333, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental design and microglial activation following LPS stimulation (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow. BV-2 cells were seeded at 5 × 10^4 cells/well, cultured overnight, pretreated with oxytocin (33ng/mL) for 2 hours, and subsequently stimulated with LPS (0.5 µg/mL). Cells were harvested at 2 or 6 hours for gene expressions analysis. (B) IBA1 immunofluorescence in mock and LPS-treated BV-2 cells. Cells were stimulated with LPS (0.5 µg/mL). Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) Validation of oxytocin effects on LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 cells. qRT-PCR analysis of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α and COX-2 expression under negative control (NC), DPBS, OT alone, LPS alone, and LPS+OT conditions. OT denotes oxytocin (33ng/mL). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2), internally normalized to GAPDH renormalized to NC.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and microglial activation following LPS stimulation (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow. BV-2 cells were seeded at 5 × 10^4 cells/well, cultured overnight, pretreated with oxytocin (33ng/mL) for 2 hours, and subsequently stimulated with LPS (0.5 µg/mL). Cells were harvested at 2 or 6 hours for gene expressions analysis. (B) IBA1 immunofluorescence in mock and LPS-treated BV-2 cells. Cells were stimulated with LPS (0.5 µg/mL). Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) Validation of oxytocin effects on LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 cells. qRT-PCR analysis of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α and COX-2 expression under negative control (NC), DPBS, OT alone, LPS alone, and LPS+OT conditions. OT denotes oxytocin (33ng/mL). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2), internally normalized to GAPDH renormalized to NC.

Figure 2.

RNA-seq analysis demonstrates that oxytocin attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 microglia. (A) RNA-seq of BV-2 cells treated with NC, OT (33ng/mL), LPS (0.5 µg/mL, 2 h), and LPS+OT. MA and volcano plots are shown for two contrasts: LPS vs NC and LPS vs LPS+OT. Differentially expressed genes were defined as adjusted p < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 (red, upregulated; blue, downregulated; gray, not significant). (B) Normalized RNA-seq expression of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α and COX-2 under NC, OT, LPS, and LPS+OT conditions. Oxytocin reduced IL-6 and COX-2, whereas IBA1 and TNF-α showed no significant change. OT denotes oxytocin (33ng/mL). (C) Relative mRNA expression changes of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2 in BV-2 cells.

Figure 2.

RNA-seq analysis demonstrates that oxytocin attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 microglia. (A) RNA-seq of BV-2 cells treated with NC, OT (33ng/mL), LPS (0.5 µg/mL, 2 h), and LPS+OT. MA and volcano plots are shown for two contrasts: LPS vs NC and LPS vs LPS+OT. Differentially expressed genes were defined as adjusted p < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 (red, upregulated; blue, downregulated; gray, not significant). (B) Normalized RNA-seq expression of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α and COX-2 under NC, OT, LPS, and LPS+OT conditions. Oxytocin reduced IL-6 and COX-2, whereas IBA1 and TNF-α showed no significant change. OT denotes oxytocin (33ng/mL). (C) Relative mRNA expression changes of IBA1, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2 in BV-2 cells.

Figure 3.

RNA-seq analysis reveals oxytocin-mediated transcriptional changes in BV-2 microglia. (A) GO enrichment analysis (Biological Process, BP) of DEGs from LPS + OT versus LPS. Top enriched biological processes are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (B) GO enrichment analysis (Molecular Function, MF) of DEGs from the same comparison. Top enriched molecular functions are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (C) GO enrichment analysis (Cellular Component, CC) of DEGs from the same comparison. Top enriched cellular components are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of downregulated genes in LPS + OT compared with LPS (log2FC < −0.7, p-adj < 0.05) identifying the IL-17 signaling pathway as the most significantly affected. (E) Schematic representation of the IL-17 signaling pathway adapted from KEGG. Key downstream targets such as IL-6 and COX-2 (red box)—which were significantly downregulated by OT—are included to illustrate potential regulatory mechanisms through which OT modulates microglial inflammatory responses. RNA-seq experiments were performed in biological triplicates (n = 3 per group). Statistical significance for DEGs was determined using DESeq2 with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p values.

Figure 3.

RNA-seq analysis reveals oxytocin-mediated transcriptional changes in BV-2 microglia. (A) GO enrichment analysis (Biological Process, BP) of DEGs from LPS + OT versus LPS. Top enriched biological processes are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (B) GO enrichment analysis (Molecular Function, MF) of DEGs from the same comparison. Top enriched molecular functions are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (C) GO enrichment analysis (Cellular Component, CC) of DEGs from the same comparison. Top enriched cellular components are displayed (dot size, gene counts; color, adjusted p value; x-axis, GeneRatio). (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of downregulated genes in LPS + OT compared with LPS (log2FC < −0.7, p-adj < 0.05) identifying the IL-17 signaling pathway as the most significantly affected. (E) Schematic representation of the IL-17 signaling pathway adapted from KEGG. Key downstream targets such as IL-6 and COX-2 (red box)—which were significantly downregulated by OT—are included to illustrate potential regulatory mechanisms through which OT modulates microglial inflammatory responses. RNA-seq experiments were performed in biological triplicates (n = 3 per group). Statistical significance for DEGs was determined using DESeq2 with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p values.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).