1. Introduction

The development of advanced energy storage systems has become one of the most urgent priorities in materials science and applied chemistry, driven by the accelerating global transition towards sustainable energy and the pervasive growth of portable and autonomous electronic devices. The rising complexity of modern technologies—ranging from medical implants and wearable sensors to distributed Internet of Things (IoT) networks—requires energy storage platforms that combine high performance, long-term reliability, and multifunctionality in compact and lightweight formats [

1]. Conventional electrochemical systems, particularly lithium-ion batteries, have dominated the energy storage landscape due to their relatively high energy density (100–250 Wh kg⁻¹). However, their limited power density, long charging times, and safety issues associated with flammable electrolytes motivate the exploration of complementary or alternative devices [

2]. Supercapacitors, also known as electrochemical capacitors, bridge the gap between batteries and traditional capacitors by delivering high power density, rapid charging/discharging, and excellent cycling stability [

3]. Two major categories exist: electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs), where charge is stored electrostatically at the electrode/electrolyte interface, and pseudocapacitors, which involve fast and reversible surface redox processes [

4]. Despite their outstanding power performance, conventional supercapacitors typically achieve energy densities in the range of 3–10 Wh kg⁻¹, well below that of batteries [

5]. This intrinsic limitation restricts their applicability in autonomous devices that require prolonged operation without frequent recharging.

Addressing this challenge requires not only improvements in electrode materials but also the redefinition of device functionality. Recent years have witnessed the emergence of photoresponsive supercapacitors, which exploit the interaction between light and electrochemical processes to enhance energy storage capacity or even provide self-charging capability. By integrating photoactive materials into electrode architectures, such devices can generate additional charge carriers under illumination, leading to improved capacitance and energy output [

5]. Mechanisms such as photogenerated electron–hole pair separation, interfacial polarization, and photodoping have been proposed to explain the enhancement of capacitance under light irradiation [

6].

Among the photoactive materials explored, titanium dioxide (TiO₂) has been extensively investigated due to its stability, abundance, non-toxicity, and well-understood photocatalytic properties [

7]. TiO₂ exhibits three main crystalline forms—anatase, rutile, and brookite—each with distinct surface energies, band structures, and catalytic activities. Anatase, with a bandgap of ~3.2 eV, is the most widely studied due to its superior photocatalytic activity under ultraviolet (UV) light, while rutile (~3.0 eV) demonstrates higher thermodynamic stability [

8]. However, pristine TiO₂ suffers from significant drawbacks, such as low electronic conductivity and rapid recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, which reduce its efficiency in electrochemical and photocatalytic processes [

9].

To overcome these limitations, researchers have turned to hybrid materials combining TiO₂ with highly conductive carbon-based nanostructures, especially graphene and its derivatives. Graphene, a two-dimensional sheet of sp²-bonded carbon atoms, provides exceptional conductivity (~10⁶ S m⁻¹), ultrahigh surface area (~2600 m² g⁻¹), and remarkable mechanical properties [

10]. Its incorporation into TiO₂-based electrodes enhances charge transport, suppresses electron–hole recombination, and improves the structural integrity of the composite under repeated cycling [

11]. Moreover, defect sites and functional groups in reduced graphene oxide (rGO) facilitate strong interfacial coupling with TiO₂, leading to synergistic improvements in both electrochemical and photoelectrochemical performance [

12].

The coupling of TiO₂ and graphene not only enhances energy storage characteristics but also paves the way for dual-functionality. Recent work has demonstrated that such hybrids can operate as both energy storage devices and environmental sensors. TiO₂ nanostructures exhibit intrinsic sensitivity to humidity, oxygen, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), while graphene provides high surface-to-volume ratio and tunable surface chemistry, making the hybrid suitable for capacitive sensing applications [

13] Graphene-based wireless bacteria detection on tooth enamel. In these systems, adsorption of analytes leads to detectable variations in capacitance, effectively integrating energy storage and environmental monitoring into a single device [

14].

From a broader perspective, multifunctional supercapacitors based on TiO₂/graphene hybrids align with the global push towards self-powered and intelligent electronics. The ability to harvest energy from ambient light, store it, and simultaneously monitor environmental conditions represents a paradigm shift in the design of autonomous systems. These devices hold promise for applications ranging from wearable health monitoring to distributed environmental sensing in smart cities, and even aerospace platforms where weight, multifunctionality, and reliability are critical [

15].

Given this context, the present review aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of photoresponsive TiO₂/graphene hybrid electrodes. Specifically, it discusses their working principles, material properties, fabrication strategies, dual-function capabilities, and performance benchmarks. Special attention is devoted to the underlying mechanisms of photo-induced capacitance enhancement and the integration of sensing functions with storage. By consolidating current knowledge, identifying challenges, and outlining future directions, this review seeks to contribute to the rational design of multifunctional, next-generation energy devices.

2. Fundamentals of Photoresponsive Supercapacitors

2.1. Working Principles of Supercapacitors – EDLCs vs Pseudocapacitors

The operation of supercapacitors relies on two distinct but often complementary charge storage mechanisms: the formation of an electrochemical double layer and the occurrence of fast, reversible faradaic processes. Devices dominated by the first mechanism are known as electrical double-layer capacitors (EDLCs), while those exploiting the second are referred to as pseudocapacitors. Understanding the interplay between these two modes of energy storage is essential to rationalize the performance of emerging photoresponsive hybrid systems such as TiO₂/graphene-based supercapacitors. In EDLCs, the capacitance originates from electrostatic charge accumulation at the electrode–electrolyte interface. When a potential is applied, ions in the electrolyte arrange themselves near the charged surface of the electrode, creating what is known as the Helmholtz double layer. The effective separation distance is only a few angstroms, which allows very high capacitance per unit area. The classical expression C=εA/d illustrates that maximizing the accessible surface area A and minimizing the separation distance d are key to achieving high capacitance. This is why carbon-based materials, especially graphene, are the cornerstone of EDLC technology: they provide extremely large surface areas, excellent conductivity, and chemical stability, enabling specific capacitances of several hundred farads per gram under optimized conditions [

1]. The purely electrostatic nature of this storage process grants EDLCs outstanding cycle life, often exceeding 10⁵ cycles with minimal degradation, and ultra-fast charge/discharge rates. However, their energy density is relatively modest, typically 5–10 Wh kg⁻¹, which limits their application in scenarios demanding sustained energy delivery [

16]. In contrast, pseudocapacitors exploit fast faradaic reactions occurring either on the electrode surface or within near-surface layers. These include redox reactions, ion electrosorption with charge transfer, and shallow intercalation processes. Unlike batteries, pseudocapacitors do not involve phase transformations or irreversible chemical changes; the faradaic processes are highly reversible and kinetically fast. The result is a much higher capacitance than EDLCs can provide, often one to two orders of magnitude greater per surface area unit. Classical examples include transition metal oxides such as RuO₂, MnO₂, and TiO₂, as well as conducting polymers like polyaniline or polypyrrole [

17]. The main advantage of pseudocapacitance lies in its ability to dramatically enhance energy density, often bridging the gap between batteries and EDLCs. However, this comes at the expense of durability: faradaic processes typically induce gradual degradation of the electrode structure or chemical composition, leading to shorter cycle lifetimes compared with EDLC-based devices [

18]. In practice, many high-performance devices combine both mechanisms. Hybrid supercapacitors intentionally integrate EDLC-active materials, such as graphene or activated carbons, with pseudocapacitive components, such as TiO₂ or MnO₂, to exploit the high power of EDLCs and the enhanced energy of pseudocapacitors. The synergy between these two contributions often results in improved performance metrics that cannot be achieved by either mechanism alone [

19]. The hybridization strategy is particularly relevant in the development of multifunctional and photoresponsive systems. In the case of TiO₂/graphene electrodes, graphene ensures fast electron transport and extensive electrostatic charge storage, while TiO₂ contributes additional pseudocapacitance through reversible surface redox processes. Moreover, TiO₂ is photoactive: upon illumination with UV or visible light, photogenerated electron–hole pairs further enhance charge separation and reduce recombination, leading to a measurable increase in capacitance. This light-induced modulation of capacitance not only boosts energy storage performance but also opens the possibility of integrating environmental sensing functions, as TiO₂ surfaces are known to interact with volatile organic compounds and humidity [

20]. The distinction between EDLCs and pseudocapacitors, therefore, is not merely of academic interest but provides the conceptual framework to design multifunctional devices. By carefully tailoring the contributions of electrostatic and faradaic processes, and by incorporating photoresponsive materials, next-generation supercapacitors can simultaneously achieve high power, enhanced energy density, responsiveness to environmental stimuli, and durability suitable for wearable and distributed sensing platforms. A concise comparison of the key features of EDLCs, pseudocapacitors, and hybrid/photoresponsive devices is provided in

Table S1, which highlights their respective charge storage mechanisms, materials, performance metrics, cycle life, and additional functionalities. The table emphasizes that while EDLCs and pseudocapacitors each offer distinct advantages and limitations, hybrid systems—particularly photoresponsive TiO₂/graphene composites—represent a versatile and promising pathway toward multifunctional energy storage devices with integrated sensing capabilities.

2.2. Mechanisms of Photo-Induced Capacitance Enhancement

The enhancement of capacitance under light irradiation in photoresponsive supercapacitors arises from the unique interaction between semiconductor photoactivity and electrochemical charge storage processes. When hybrid materials such as TiO₂/graphene are exposed to illumination, a series of electronic and interfacial phenomena are triggered that profoundly modify the dynamics of charge storage. At the heart of this effect is the generation of photocarriers in the semiconductor, which under appropriate conditions can be separated and transferred to conductive supports such as graphene. Photons with energies equal to or higher than the TiO₂ band gap (∼3.2 eV for anatase) excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving behind positively charged holes. The resulting electron–hole pairs, if not recombined, substantially increase the density of free carriers available to participate in electrochemical processes at the electrode–electrolyte interface. Graphene, owing to its high conductivity and delocalized π-electron system, acts as an effective sink and transport channel for photogenerated electrons, thereby reducing recombination losses and extending carrier lifetimes. This cooperative interaction ensures that a significant fraction of the photoexcited electrons contribute to electrochemical double-layer formation and pseudocapacitive reactions, leading to measurable increases in capacitance, often reported in the range of 20–40% under UV or visible illumination [

21].

In addition to the generation of carriers, illumination also reshapes the interfacial polarization phenomena that govern energy storage in supercapacitors. In classical EDLCs, the capacitance is limited by the electrostatic alignment of electrolyte ions at the electrode surface. The introduction of photogenerated carriers in TiO₂ alters local electric fields, reinforcing the polarization at the semiconductor–electrolyte boundary. This “photoinduced polarization” manifests as a strengthening of the double layer, effectively increasing the apparent capacitance. Nanostructured TiO₂ architectures, such as nanotubes, nanowires, or mesoporous films, are particularly effective in amplifying this effect due to their high density of active surface sites. Moreover, the photogenerated holes at the TiO₂ surface can interact with adsorbed molecules such as water, hydroxyls, or even volatile organic compounds, modifying surface dipoles and leading to dynamic shifts in interfacial polarization. When coupled with graphene, these polarization effects are spread across a highly conductive carbon network, ensuring that the photoinduced charges are efficiently distributed and that polarization occurs over a larger effective interfacial area [

22]. This dynamic interplay between ionic adsorption and electronic carrier redistribution is one of the main reasons why hybrid electrodes show stronger light-enhanced capacitance compared to bare semiconductors.

A further, and in many ways more subtle, mechanism is photodoping, which arises when photogenerated electrons or holes become trapped in defect states, oxygen vacancies, or interfacial sites within the semiconductor. In the case of TiO₂, electrons trapped in oxygen vacancies shift the Fermi level closer to the conduction band, effectively increasing electronic conductivity and lowering the charge-transfer resistance at the electrode/electrolyte interface. This phenomenon, often described as “photoinduced doping,” can persist beyond the illumination period, leading to long-lived conductive states and a memory effect in capacitance, where enhanced charge storage is maintained for some time even after the light is switched off [

23,

24]. Such persistent photoconductivity is particularly relevant for multifunctional applications, as it enables hybrid electrodes not only to store energy more efficiently under light but also to retain enhanced responsiveness in the dark. In addition, photodoping dynamically modifies the band alignment between TiO₂ and graphene, facilitating more favorable electron injection and faster interfacial kinetics. These shifts reduce internal resistance and improve the overall efficiency of both electrostatic and faradaic processes. The combined effect of these mechanisms creates a highly synergistic scenario. Photogenerated carriers increase the available charge density; surface polarization strengthens the double layer and enhances ion–electron coupling at the interface; and photodoping stabilizes charges, lowers resistance, and extends the lifetime of photoinduced states. Rather than being isolated, these processes reinforce one another: graphene extracts and delocalizes photogenerated electrons, preventing recombination and spreading polarization; TiO₂ provides a dense network of active sites where interfacial fields and photodoping can occur; and the hybrid architecture allows these microscopic effects to translate into macroscopic capacitance enhancement. Under continuous illumination, the capacitance of TiO₂/graphene devices has been shown to increase by as much as 35%, while maintaining stability over thousands of cycles [

18,

19]. Perhaps most significantly, these same photo-induced processes also confer additional functionalities beyond energy storage. The interaction of photogenerated holes with adsorbed species makes TiO₂-based electrodes inherently sensitive to environmental factors such as humidity and volatile organic compounds. Changes in adsorption alter polarization and photodoping dynamics, which can be transduced into measurable shifts in capacitance. As a result, TiO₂/graphene photoresponsive supercapacitors operate simultaneously as energy storage devices and environmental sensors. Recent work by Al-Hamry et al. [

20] demonstrated that TiO₂/graphene oxide nanocomposites act as highly sensitive humidity sensors, confirming that environmental monitoring can be embedded directly into energy storage platforms without additional components. This multifunctionality is particularly relevant for next-generation wearable and distributed electronics, where self-powered, adaptive, and environmentally aware devices are in increasing demand.

Taken together, the mechanisms of charge separation, interfacial polarization, and photodoping illustrate the fundamental basis of light-enhanced supercapacitor performance. They show how careful integration of photoactive oxides with conductive carbons like graphene can transform supercapacitors from passive energy storage devices into active, multifunctional systems. By exploiting photon–matter interactions at the nanoscale, it becomes possible to design electrodes that not only store more energy under illumination but also sense and respond to their environment, paving the way for self-sufficient smart technologies.

2.3. Influence of UV vs. Visible Light

The spectral region of incident light strongly determines the mechanisms and magnitude of photo-induced capacitance in supercapacitors. Ultraviolet (UV) photons, with wavelengths below 400 nm, have sufficient energy to directly excite wide-bandgap semiconductors such as TiO₂ and ZnO (bandgap ~3.0–3.2 eV), leading to efficient electron–hole pair generation and strong capacitance enhancement. In contrast, visible light comprises about 45% of the solar spectrum but has lower photon energy, which makes it far more abundant and sustainable yet requires careful material engineering to harvest effectively. Under UV light, wide-bandgap semiconductors undergo direct band-to-band transitions in which photogenerated carriers are efficiently separated and accumulated in the electrode or at the electrode–electrolyte interface. A clear demonstration of this effect was reported in ZnO-based photo-supercapacitors, where the specific capacitance of ZnO nanofibers increased by approximately 2.4 times and that of ZnO nanowires nearly doubled under UV irradiation. Charge–discharge times decreased by almost fivefold, while the coulombic efficiency improved from about 33% to over 100%, underscoring the strong role of UV photons in promoting charge storage processes [

25]. These improvements were attributed to enhanced photocarrier generation, reduced charge transfer resistance, and extended diffusion pathways observed in impedance spectra. Despite these advantages, UV light constitutes less than 5% of natural sunlight, which limits the sustainability of UV-driven systems. This makes the development of visible-light responsive photo-supercapacitors an essential step toward practical devices. Several strategies have been explored, including bandgap engineering through doping with transition metals such as Fe, Co, or V, or non-metals such as N, S, and C, which introduce intermediate states that allow absorption of sub-bandgap photons. Another approach relies on coupling wide-bandgap oxides with narrow-bandgap semiconductors such as MoS₂, CdS, or g-C₃N₄, enabling the transfer of photogenerated carriers across heterointerfaces. Hybridization with conductive carbonaceous nanostructures such as graphene, reduced graphene oxide, and carbon nanotubes has also proven effective, as these materials extend the optical absorption range while providing rapid charge transport pathways. The potential of visible-light activation has been convincingly demonstrated in recent studies. A hybrid photocapacitor integrating a dye-sensitized solar cell with an asymmetric supercapacitor achieved a charging voltage of 920 mV under indoor light illumination (1000 lux) and a power conversion efficiency exceeding 30%, allowing continuous operation of a microcontroller without external batteries [

26]. Another example involves the use of germanane and its derivatives as photoactive electrodes in hybrid zinc-ion capacitors. When irradiated with visible light at 435 nm, capacitance increased by up to 52%, retention of 91% was maintained after 3000 cycles, and maximum capacitance values reached nearly 6000 mF g⁻¹, with charging voltages approaching 1 V [

27]. In addition, heterojunctions combining polymeric carbon nitride with MXene nanosheets have been shown to drive efficient photo-charging under visible light via interfacial charge transfer, leading to highly efficient photo-rechargeable supercapacitors [

28].

Taken together, these results illustrate a fundamental tradeoff. UV irradiation provides straightforward, highly efficient carrier generation but is scarce under solar illumination, while visible light is abundant but requires advanced materials engineering to exploit. Progress in heterojunction design, doping, hybrid nanostructures, and 2D semiconductors demonstrates that visible-light harvesting can enable sustainable, solar-compatible, and multifunctional photo-supercapacitors. Transitioning from UV-driven to visible-light-responsive devices is therefore not only an optimization of efficiency but also a paradigm shift toward real-world applications in energy storage, sensing, and autonomous electronics.

2.4. Distinction from Photo-Rechargeable Batteries

Photo-active supercapacitors must be clearly distinguished from photo-rechargeable batteries, even though both concepts rely on coupling light harvesting with energy storage. The key difference lies in the underlying charge storage mechanism. Supercapacitors store energy electrostatically at the electrode–electrolyte interface in electric double layers or through fast surface redox reactions, enabling rapid charging and discharging and high cyclability. In contrast, photo-rechargeable batteries operate through bulk redox processes within electrode materials, where photogenerated carriers directly drive insertion or extraction of ions such as Li⁺, Na⁺, or Zn²⁺, resulting in higher energy density but typically slower kinetics. In photo-active supercapacitors, light irradiation enhances the capacitance by increasing carrier density, promoting interfacial polarization, or driving charge transfer across engineered heterojunctions. This effect is transient and strongly dependent on the illumination conditions; once the light source is removed, the additional capacitance gain decays. In photo-rechargeable batteries, however, photons directly participate in driving faradaic reactions, enabling the storage of solar energy in the form of chemical energy. A well-studied case is the use of TiO₂ photoanodes in lithium-ion systems, where photogenerated electrons facilitate Li⁺ insertion into TiO₂, leading to direct photocharging of the battery [

29]. The differences in performance metrics further highlight this distinction. Performance metrics also highlight the fundamental distinction. Photo-rechargeable batteries typically achieve higher energy densities, often exceeding 150 Wh kg⁻¹, but are limited in power density and cycle life. Photo-supercapacitors, in contrast, deliver power densities in the kW kg⁻¹ range and demonstrate cycling stability beyond 10⁵ cycles, although their energy densities remain comparatively lower. An illustrative example of integrated photo-energy storage is the work of Plebankiewicz et al., who combined silicon solar cells with supercapacitors in a photo-rechargeable architecture, demonstrating the potential of hybrid systems [

30]. Another fundamental difference is architectural. Photo-rechargeable batteries often employ semiconductor photoelectrodes directly interfaced with redox-active insertion compounds, requiring careful band alignment to enable ion intercalation. In photo-active supercapacitors, the illumination is used to generate excess carriers in the electrode material or its surface states, which then contribute to enhanced double-layer formation or pseudocapacitance. This difference also influences application scenarios. While photo-rechargeable batteries are aimed at long-term solar energy storage, such as off-grid power supply, photo-active supercapacitors are better suited for short-term, high-power applications, including self-powered sensors, transient electronics, and hybrid systems integrated with photovoltaics.

This conceptual distinction is important for guiding future research. Photo-rechargeable batteries will continue to evolve toward higher efficiencies through material design, but challenges such as slow kinetics, complex architectures, and stability under prolonged illumination remain. Photo-active supercapacitors, while offering lower energy density, provide unique opportunities for real-time energy buffering and multifunctional integration, where fast response and robustness outweigh the need for long-duration storage. The complementary development of both technologies will therefore be essential for building integrated solar-powered energy storage systems that combine the high-power performance of supercapacitors with the high energy density of batteries.

3. TiO₂-Based Photoactive Materials

3.1. Structural, Optical, and Electrochemical Properties of TiO₂ (Anatase, Rutile, Brookite)

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) is a prototypical photoactive material that crystallizes in three main polymorphs—anatase, rutile, and brookite—each displaying distinct structural, optical, and electrochemical features that strongly influence their performance in photo-assisted energy storage systems. All three structures are composed of TiO₆ octahedra but differ in their connectivity and distortion, which in turn modulate surface energy, defect chemistry, and electronic band structure. Anatase has a tetragonal structure characterized by corner- and edge-sharing TiO₆ octahedra with slight distortions, resulting in a relatively open framework that facilitates high surface area and enhanced reactivity. Rutile, also tetragonal, adopts a more compact arrangement with linear Ti–O–Ti bonds, making it the thermodynamically most stable polymorph at elevated temperatures. Brookite, in contrast, exhibits an orthorhombic structure with a more complex network of distorted TiO₆ units, giving rise to intrinsic lattice strain and a high density of surface-active sites. These differences in atomic arrangement lead to variations in particle morphology, defect distribution, and reactivity under illumination [

7]. From an optical standpoint, TiO₂ is a wide-bandgap semiconductor, with anatase showing a bandgap of ~3.2 eV, rutile ~3.0 eV, and brookite ~3.1 eV. These values restrict absorption mainly to the ultraviolet region of the solar spectrum (<5%), limiting practical solar-driven applications. Nevertheless, anatase is generally considered the most photoactive polymorph because its conduction band minimum lies at a higher energy than rutile, leading to stronger reducing power and more efficient charge separation. Rutile, while less efficient in photogeneration, benefits from a slightly narrower bandgap that extends absorption into longer UV wavelengths. Brookite, although less studied, has attracted growing interest due to its intrinsic lattice distortion, which enhances electron–hole separation and enables synergistic effects when combined with other polymorphs. Indeed, mixed-phase systems such as anatase–rutile or anatase–brookite heterojunctions often outperform single-phase materials by promoting internal electric fields that suppress recombination [

31]. Electrochemically, the three polymorphs also display distinct behaviors. Anatase is well known for its capability to accommodate small cations (Li⁺, Na⁺, H⁺) through reversible intercalation, which underpins its use in both batteries and pseudocapacitive electrodes. Its relatively open structure and high surface area enable fast ion transport and high cycling stability. Rutile, owing to its dense atomic packing, is less favorable for ion insertion but exhibits excellent chemical stability in aqueous environments, making it attractive for long-term durability in supercapacitors and hybrid photoelectrochemical systems. Brookite combines features of both, with higher surface energy and defect density that provide abundant adsorption sites for ions, potentially enhancing pseudocapacitance and light-assisted charge storage. The electrochemical response of TiO₂ electrodes is further enhanced at the nanoscale, where morphologies such as nanotubes, nanorods, and mesoporous films improve ion accessibility and charge separation, while defect engineering (oxygen vacancies, Ti³⁺ states) enhances conductivity and facilitates photocarrier transport [

21]. Overall, anatase is the most exploited phase for photo-assisted supercapacitor applications due to its superior electronic properties, but recent studies highlight the advantages of mixed-phase and defect-engineered systems that combine the strengths of anatase, rutile, and brookite. These polymorphs, through their structural, optical, and electrochemical complementarities, continue to provide a versatile platform for advancing TiO₂-based photoactive materials in energy storage applications.

3.2. Role of Crystallinity, Particle Size, and Surface Area

The performance of TiO₂-based photoactive materials in energy storage devices is not only governed by their intrinsic band structure but is also highly sensitive to microstructural parameters such as crystallinity, particle size, and surface area. These factors determine the density of active sites, the transport pathways for electrons and ions, and the overall balance between charge storage capacity, rate capability, and cycling stability.

Crystallinity plays a decisive role in charge carrier dynamics. Highly crystalline TiO₂ typically exhibits fewer structural defects, which reduces charge carrier recombination and promotes efficient electron transport. For example, Chen and Mao highlighted that improved crystallinity enhances the electron diffusion length, thereby facilitating efficient charge separation and transfer in anatase nanoparticles [

21]. However, excessive crystallinity can also reduce the density of surface hydroxyl groups and active defect sites (such as Ti³⁺ centers or oxygen vacancies), which are crucial for pseudocapacitive charge storage and surface redox reactions. Thus, an optimal trade-off between crystallinity and defect density is required to maximize both conductivity and capacitance.

Particle size is equally important. Reducing the crystallite size to the nanoscale increases the specific surface area and shortens the diffusion distance for charge carriers and ions, resulting in improved electrochemical kinetics. Nanoparticles and nanocrystals with diameters below 20 nm exhibit quantum confinement effects, which shift the bandgap to higher energies, enhancing photocatalytic activity under UV light but limiting visible-light absorption. Conversely, larger crystallites reduce surface area but may favor bulk ion insertion processes due to reduced recombination at grain boundaries. Studies on TiO₂ nanocrystals have shown that optimal sizes around 10–20 nm balance high surface reactivity with efficient charge transport, leading to enhanced performance in hybrid energy storage applications [

32].

Surface area and porosity are central to the capacitive behavior of TiO₂ electrodes. A larger accessible surface increases the number of electrochemically active sites for double-layer formation and surface faradaic reactions, while mesoporous architectures improve electrolyte infiltration and ion diffusion. The introduction of hierarchical porosity—micropores for ion adsorption, mesopores for ion transport, and macropores for electrolyte diffusion—has been shown to markedly enhance capacitance and cycling stability. For instance, Wu et al. demonstrated that mesoporous TiO₂–carbon composites provide high surface area and improved electron pathways, enabling significant enhancement in both energy and power densities [

33]. The interplay between these three factors becomes particularly evident when evaluating different TiO₂ morphologies. Nanotubes, nanowires, and mesoporous films often exhibit higher specific surface area and directional electron transport compared to bulk particles, effectively reducing diffusion limitations and enhancing charge separation. However, excessive downsizing can cause structural instability, particle aggregation, and reduced electrical connectivity. Therefore, optimal performance in photoactive supercapacitors is achieved through the rational engineering of crystallinity, particle dimensions, and porous architectures, often complemented by defect engineering and surface functionalization to fine-tune charge transfer dynamics [

34,

35].

In conclusion, crystallinity, particle size, and surface area are intimately connected parameters that control the optical absorption, charge carrier dynamics, and electrochemical response of TiO₂. Optimizing these properties not only enhances UV-light-driven capacitance but also provides a platform for coupling with sensitizers and carbon-based materials to extend activity into the visible range, thereby broadening the application potential of TiO₂-based photoactive supercapacitors.

3.3. Bandgap Tuning via Doping (e.g., N, F, Metals)

One of the main limitations of pristine TiO₂ is its wide bandgap (~3.0 eV for rutile and ~3.2 eV for anatase), which restricts its optical absorption mainly to the ultraviolet region, accounting for less than 5% of the solar spectrum. To extend its activity into the visible-light range and improve its suitability for photoactive energy storage, bandgap tuning through doping has been extensively investigated. Doping introduces impurity levels within the electronic structure of TiO₂, modifying the positions of the conduction and valence bands, altering charge carrier dynamics, and facilitating absorption of sub-bandgap photons. Non-metal doping has received particular attention for visible-light activation. Nitrogen doping is among the most widely studied strategies; substitutional N atoms introduce localized states above the valence band maximum of TiO₂, effectively narrowing the bandgap and shifting absorption into the visible range. Asahi et al. were the first to demonstrate that N-doped TiO₂ exhibits visible-light photocatalytic activity, attributing this effect to the mixing of N 2p states with O 2p orbitals [

36]. Other non-metals, such as fluorine, carbon, and sulfur, have also been employed. Fluorine, in particular, enhances the surface acidity and modifies surface states, improving charge separation and electrochemical reactivity without drastically altering the bandgap [

37]. Metal doping offers another effective pathway. Transition metals such as Fe, Cr, V, and Mn can introduce discrete donor or acceptor states within the bandgap, thereby extending light absorption into the visible region. However, the incorporation of transition metal dopants must be carefully optimized, as excessive doping often promotes charge carrier recombination and reduces photo-efficiency. For example, Fe³⁺ ions can serve as shallow traps for electrons, enhancing charge separation, while higher doping levels lead to recombination centers that suppress activity. Choi et al. demonstrated that dopants such as V⁵⁺, Cr³⁺, and Fe³⁺ significantly alter photocatalytic responses, with the effect strongly dependent on dopant concentration [

37]. Noble metals such as Au, Ag, and Pt, though not classical dopants, have also been employed to create localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects, enabling visible and near-infrared activation by hot electron injection into TiO₂ conduction bands. Co-doping strategies have been developed to overcome the limitations of single-element doping, such as localized recombination. By introducing two complementary dopants—such as N with transition metals or F with cations—it is possible to simultaneously narrow the bandgap and stabilize charge carriers, leading to more efficient utilization of visible light. Khan et al. reviewed how non-metal/metal co-doping provides synergistic effects that enhance both photocatalytic and electrochemical performance [

38]. For photoactive supercapacitors, bandgap-tuned TiO₂ electrodes demonstrate improved visible-light responsivity, enhanced charge accumulation, and better interfacial redox activity. By tailoring the dopant type and concentration, it is possible to maximize light harvesting while maintaining conductivity and cycling stability. Ultimately, doping strategies—whether based on anion substitution, cation incorporation, or hybrid co-doping—represent a crucial direction in designing TiO₂-based photoactive materials for next-generation energy storage devices.

3.4. Synthesis Methods: Sol-Gel, Hydrothermal, Anodization, Laser-Assisted, etc.

The synthesis route of TiO₂ has a profound impact on its crystallinity, morphology, surface area, and defect distribution, which ultimately determine its structural, optical, and electrochemical properties. Different synthetic strategies provide control over phase composition (anatase, rutile, brookite), particle size, porosity, and dopant incorporation, enabling the fine-tuning of TiO₂ for photoactive supercapacitor applications. Among the most relevant approaches are sol–gel synthesis, hydrothermal methods, anodization, and laser-assisted processes. The sol–gel method is one of the most versatile techniques for fabricating TiO₂ powders, thin films, and nanostructured coatings. It involves hydrolysis and condensation of titanium precursors, such as titanium isopropoxide or titanium butoxide, followed by controlled drying and calcination. The process allows precise control of stoichiometry and facilitates doping with non-metals or metals at the molecular level. Sol–gel-derived TiO₂ generally crystallizes as anatase at moderate temperatures, with high surface area and tunable porosity. However, the method is sensitive to processing conditions, and high-temperature treatments required for crystallization often reduce surface area and introduce phase transformation into rutile [

39]. The hydrothermal and solvothermal methods are widely used to produce TiO₂ nanoparticles, nanorods, and hierarchical architectures under high-temperature and high-pressure aqueous conditions. These processes yield highly crystalline materials with well-defined morphologies without requiring post-annealing. Hydrothermal synthesis is particularly effective for fabricating brookite and anatase nanostructures, as well as for doping with heteroatoms and hybridizing with carbonaceous materials. Tailored morphologies such as nanorods and nanoflowers enhance surface area and directional electron transport, improving photoelectrochemical performance [

40]. Anodization of titanium foils in fluoride-containing electrolytes provides a straightforward route to highly ordered TiO₂ nanotube arrays, which are directly grown on conductive substrates. These vertically aligned nanotubes offer large surface area, excellent electron transport pathways, and strong mechanical adhesion to the current collector, making them particularly suitable for supercapacitor electrodes. The geometry of the nanotubes (length, diameter, wall thickness) can be tuned by adjusting anodization voltage, electrolyte composition, and duration. Roy et al. provided a comprehensive overview of TiO₂ nanotube synthesis and applications, emphasizing their role in photoelectrochemical and energy storage devices [

35]. Laser-based treatments have gained prominence as advanced methods to engineer TiO₂ surfaces, introducing defect sites that enhance visible-light response. Pulsed laser irradiation, especially using femtosecond lasers, can induce localized surface modifications without affecting the bulk material. Notably, femtosecond laser treatment of TiO₂ colloids has been shown to generate stable, dark-colored TiO₂ nanostructures (often described as "black TiO₂") through the controlled creation of oxygen vacancies and surface disorder—significantly narrowing the optical bandgap while retaining crystal phase integrity [

41]. Additionally, pulsed laser ablation in liquids offers a green and versatile route to produce colloidal TiO₂ nanoparticles with pristine surfaces, free from chemical residues, which is advantageous for applications in photocatalysis and electrochemical energy storage [

42]. Other advanced methods, such as flame spray pyrolysis, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and atomic layer deposition (ALD), have also been employed to fabricate TiO₂ nanostructures with precise dimensional control and excellent scalability. Flame spray pyrolysis allows large-scale production of TiO₂ nanoparticles with controlled crystallinity and surface area, making it attractive for practical applications. CVD techniques provide conformal and uniform TiO₂ coatings on complex substrates, while ALD offers sub-nanometer thickness control, enabling the deposition of pinhole-free and highly uniform TiO₂ films. These approaches are particularly useful for producing thin coatings on electrodes, improving interfacial stability, and integrating TiO₂ into hybrid energy storage and photoelectrochemical architectures [

43,

44,

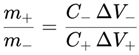

45]. As a visual summary of laser-assisted routes relevant to TiO₂ processing and defect engineering, the main schemes for LAL (laser ablation in liquids), LFL (laser fragmentation in liquids), LML (laser melting in liquids), and LDL (laser defect engineering in liquids) are compiled in

Figure 1.

In summary, the choice of synthesis method dictates the phase composition, crystallinity, particle size, and surface properties of TiO₂. Sol–gel offers compositional flexibility, hydrothermal routes enable well-crystallized nanostructures, anodization produces ordered nanotube arrays with excellent interfacial properties, and laser-assisted processes create defect-engineered TiO₂ with extended optical response. Rational selection and combination of these methods allow the design of advanced TiO₂ electrodes with optimized light absorption, charge transport, and electrochemical performance for photoactive supercapacitor applications.

3.5. Challenges: Charge Recombination, Conductivity Limitations

Despite its wide use and advantages, TiO₂ as a photoactive material faces two critical challenges that limit its performance in photo-supercapacitors and related energy storage systems: rapid charge recombination and intrinsically low electrical conductivity. Charge recombination remains one of the most severe bottlenecks in TiO₂-based systems. Photogenerated electron–hole pairs tend to recombine within picoseconds to nanoseconds, especially in bulk materials or when surface traps act as recombination centers. This rapid recombination drastically reduces the quantum efficiency of photo-induced processes and thus lowers the contribution of light to charge storage. Even in nanostructured TiO₂, where reduced diffusion lengths improve carrier extraction, surface and grain boundary defects often promote recombination pathways. Strategies such as heterojunction engineering, coupling with carbonaceous conductors (graphene, CNTs, carbon black), and introducing oxygen vacancies have been shown to prolong carrier lifetimes and enhance interfacial charge transfer [

21,

31]. Electrical conductivity limitations also hinder the efficiency of TiO₂. As a wide-bandgap semiconductor, TiO₂ has very low intrinsic conductivity (~10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁷ S cm⁻¹), which restricts electron mobility and increases internal resistance in electrochemical devices. This limitation leads to poor rate capability and reduces the achievable power density in photo-supercapacitors. Several approaches have been pursued to overcome this issue: (i) doping with transition metals (Fe, Nb, Ta) to enhance carrier concentration, (ii) hydrogenation or reduction treatments to create Ti³⁺ states and oxygen vacancies that improve n-type conductivity, and (iii) hybridization with conductive scaffolds such as reduced graphene oxide or conducting polymers. Notably, hydrogenated “black TiO₂” demonstrates orders-of-magnitude higher conductivity and improved visible-light absorption, offering a promising pathway for photoactive energy storage [

32]. In addition to recombination and conductivity issues, there is also a challenge in balancing high surface area with electrical continuity. Nanostructured TiO₂ architectures—such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, or mesoporous films—provide abundant active sites and short diffusion lengths, but excessive downsizing often leads to particle aggregation, poor percolation networks, and instability under long-term cycling. This trade-off between surface activity and charge transport efficiency continues to be a central limitation for TiO₂ electrodes in photo-supercapacitors.

Addressing these challenges requires integrating defect engineering, heterostructure design, and hybridization with conductive frameworks. While significant progress has been made, further optimization is necessary to simultaneously achieve low recombination, high conductivity, and structural robustness in TiO₂-based photoactive materials for next-generation supercapacitors.

4. Graphene and Nanocarbon Enhancers

4.1. Role of Graphene/rGO/CNTs in Improving Conductivity and Charge Transport

One of the major limitations of pristine TiO₂ and other wide-bandgap photoactive oxides is their intrinsically low electrical conductivity, which hinders charge transport and limits their rate capability in energy storage devices. To overcome this drawback, conductive nanocarbon materials such as graphene, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been widely integrated with TiO₂ to form hybrid architectures. These carbonaceous enhancers act as conductive backbones that facilitate electron mobility, suppress charge recombination, and improve overall device performance. Graphene is a two-dimensional sheet of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms with outstanding electrical conductivity, high carrier mobility, and a theoretical surface area of 2630 m² g⁻¹. When coupled with TiO₂ nanoparticles, graphene serves as an electron-accepting and conducting network that extracts photogenerated electrons from TiO₂ and transports them rapidly to the current collector. This charge shuttling effect reduces recombination at TiO₂ surfaces and significantly enhances capacitance under illumination. The large surface area of graphene also improves electrolyte accessibility and provides abundant anchoring sites for TiO₂ nanoparticles, stabilizing the composite structure [

10,

46]. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) represents a cost-effective alternative to pristine graphene, retaining much of its conductivity while being more readily available through scalable chemical routes. rGO sheets, decorated with functional groups and residual defects, can form strong interfacial interactions with TiO₂, which improves charge transfer kinetics and enhances structural stability. Moreover, the oxygen-containing functionalities in rGO provide active sites for redox reactions, contributing to pseudocapacitive behavior in addition to improving electron transport. TiO₂/rGO composites have shown higher capacitance values and superior cycling stability compared to bare TiO₂ electrodes, particularly under light irradiation [

15]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), either single-walled (SWCNTs) or multi-walled (MWCNTs), offer one-dimensional conductive pathways that efficiently transport electrons while also providing mechanical robustness. CNTs can act as nanoscale “wires” that interconnect TiO₂ particles or bind them onto graphene/rGO sheets, creating three-dimensional hierarchical architectures. Such hybrid networks improve electron percolation, reduce resistance at the electrode–electrolyte interface, and enhance rate performance. In addition, CNTs prevent restacking of graphene sheets, ensuring high surface area and effective electrolyte penetration. Studies have shown that TiO₂/CNT composites exhibit improved conductivity by several orders of magnitude compared to pristine TiO₂, enabling higher power densities in supercapacitors and hybrid photoelectrochemical devices [

47].

Overall, the incorporation of graphene, rGO, and CNTs into TiO₂ electrodes provides synergistic benefits: (i) significantly improved electrical conductivity through extended conductive networks, (ii) suppression of charge recombination by rapid extraction of photogenerated carriers, (iii) enhancement of specific capacitance due to increased electroactive surface area, and (iv) improved structural integrity under long-term cycling. These hybrid materials represent one of the most effective strategies to overcome the conductivity limitations of TiO₂ and to unlock its potential in photo-supercapacitor applications.

4.2. Synergistic Effects with TiO₂: Interfacial Contact, Defect Mediation, Charge Mobility

The synergistic behavior of TiO₂ when combined with graphene, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), or carbon nanotubes (CNTs) is not a trivial additive effect but arises from the intimate coupling between the semiconductor and the conductive carbonaceous matrix. Three interconnected mechanisms, as interfacial contact, defect mediation, and charge mobility, play decisive roles in determining the enhanced performance of TiO₂/graphene nanohybrids for photoresponsive supercapacitors. A central factor is the quality of interfacial contact between TiO₂ and graphene-based materials. In bare TiO₂, photogenerated electrons are prone to recombination with holes due to limited electron transport pathways and the absence of efficient sinks. However, when TiO₂ nanoparticles are anchored onto graphene sheets, photogenerated electrons are rapidly injected into the graphene lattice owing to the favorable band alignment between TiO₂ conduction band (–4.5 eV). This strong electronic coupling ensures ultrafast charge separation and electron transfer, thereby suppressing recombination. Cheng et al. demonstrated that TiO₂/graphene nanocomposites show markedly improved photocurrent response compared to bare TiO₂, directly evidencing the role of graphene as an electron acceptor and transport channel [

48]. In the context of supercapacitors, this efficient interfacial contact not only prolongs the lifetime of photocarriers but also translates into higher capacitance under illumination, since the additional charges extracted into graphene contribute to double-layer formation and fast surface redox reactions. The second synergistic mechanism involves defect mediation. Defects in TiO₂, such as oxygen vacancies and Ti³⁺ centers, are known to influence electronic conductivity and charge carrier dynamics. While excessive defects promote nonradiative recombination, a controlled defect density can act as shallow traps that extend carrier lifetimes and induce beneficial photodoping. When TiO₂ is coupled with rGO, the residual oxygen functionalities and structural defects of rGO provide nucleation sites for TiO₂ nanoparticle growth, ensuring intimate interfacial contact and stabilization of defect-rich TiO₂ domains. This interaction mitigates detrimental recombination and enhances the persistence of photoinduced doping effects. Chen et al. reported that defect-engineered TiO₂ combined with rGO exhibited a significant decrease in charge-transfer resistance (from ~230 Ω to ~65 Ω) and improved electrochemical capacitance due to enhanced utilization of oxygen vacancies [

49,

50]. Importantly, graphene sheets help prevent defect collapse during cycling, maintaining the stability of TiO₂’s electronic structure. This defect mediation effect is particularly relevant for photo-supercapacitors, where persistent photoconductivity induced by defect states can sustain elevated capacitance even after illumination ceases. A third crucial element is the enhancement of charge mobility through hybridization with conductive carbons. Pristine TiO₂ suffers from intrinsically low electrical conductivity (~10⁻⁷ S cm⁻¹), which restricts electron transport and reduces power density. Incorporating graphene or CNTs creates highly conductive percolation pathways that dramatically increase the effective conductivity of the composite. CNTs, in particular, act as one-dimensional "wires" that interconnect TiO₂ particles and graphene sheets, forming three-dimensional electron highways. This synergy improves electron percolation, reduces internal resistance, and ensures that photogenerated carriers are rapidly transported to the current collector. Poirot et al. demonstrated that TiO₂/CNT composites achieved a specific capacitance nearly 2.5 times higher than bare TiO₂ electrodes, directly attributable to enhanced electron mobility and improved electrode/electrolyte interface properties [

51]. Similarly, hybrid TiO₂/graphene architectures have shown significant reductions in charge-transfer resistance, as confirmed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, with values decreasing by more than 60% compared to pristine TiO₂ electrodes [

52]. Taken together, these synergistic effects demonstrate that the integration of TiO₂ with graphene, rGO, and CNTs creates hybrid systems where interfacial contact accelerates charge separation, defect mediation stabilizes and harnesses oxygen vacancies, and conductive carbon networks boost charge mobility. This triad of cooperative mechanisms addresses the two major bottlenecks of TiO₂—charge recombination and poor conductivity—while simultaneously enhancing electrochemical capacitance, stability, and multifunctionality. Beyond energy storage, these synergies also underpin the environmental sensing capabilities of TiO₂/graphene systems, as interfacial and defect-mediated charge transfer mechanisms make the electrodes sensitive to adsorbed molecules such as water, oxygen, or volatile organic compounds, which alter capacitance in a measurable and reproducible manner.

In summary, the synergistic integration of TiO₂ with nanocarbon scaffolds transforms a relatively poor electronic conductor into a high-performance photoactive electrode, capable of coupling light harvesting with efficient energy storage and sensing. This cooperative interaction, verified across multiple studies, is a cornerstone in the development of multifunctional photo-supercapacitors for next-generation self-powered devices.

4.3. Common Fabrication Strategies for TiO₂–Graphene Hybrids

The fabrication of TiO₂–graphene hybrids requires methods that ensure intimate interfacial contact, uniform distribution of TiO₂ nanostructures on graphene surfaces, and preservation of the intrinsic conductivity of the carbon scaffold. Several complementary strategies have been developed, each offering specific advantages in terms of morphology control, scalability, and interfacial engineering. One of the most widely adopted routes is the sol–gel method, where titanium alkoxides such as titanium isopropoxide undergo controlled hydrolysis and condensation in the presence of graphene oxide (GO) or reduced graphene oxide (rGO). The oxygen-containing functional groups in GO act as nucleation sites for TiO₂ nanoparticles, ensuring homogeneous deposition and strong interfacial bonding. After subsequent calcination or reduction, uniform TiO₂/rGO nanocomposites are obtained, with well-dispersed nanoparticles anchored on graphene sheets. This method has been successfully employed to produce anatase–graphene composites with improved capacitance and photocatalytic response [

53,

54]. The hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis approach is another common strategy, allowing crystallization of TiO₂ under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions in the presence of graphene derivatives. This method produces highly crystalline TiO₂ nanoparticles, nanorods, or nanoflowers anchored on rGO sheets without requiring high-temperature post-treatment. The hydrothermal environment also promotes reduction of GO to rGO, thereby restoring conductivity. Other authors demonstrated that hydrothermally grown TiO₂/rGO hybrids exhibited strong interfacial coupling and enhanced photoelectrochemical performance due to improved crystallinity and conductive pathways [

55,

56]. In situ reduction–deposition methods offer the advantage of simultaneously reducing GO to rGO and depositing TiO₂ nanoparticles. Chemical reductants such as hydrazine or hydroquinone, or mild thermal treatments, are used to restore the conjugated graphene structure while Ti precursors hydrolyze to TiO₂. This dual process ensures intimate contact and avoids aggregation of TiO₂. Such in situ routes yield composites with excellent electrical conductivity and strong electronic coupling between TiO₂ and rGO [

57]. Electrochemical deposition offers an effective way to fabricate TiO₂–graphene hybrids directly onto conductive carbon substrates. In such approaches, graphene-coated electrodes act as templates for TiO₂ film growth, ensuring strong adhesion, precise control over thickness, and enhanced electrochemical stability. For example, Endrődi et al. demonstrated a one-step electrodeposition method in which nanocrystalline TiO₂ films were deposited onto graphene film electrodes. The resulting TiO₂/graphene electrodes exhibited promising photoelectrochemical behavior and notable charge storage capability, outperforming conventional reference materials under similar conditions [

58]. More recently, atomic layer deposition (ALD) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) have been leveraged to build TiO₂–graphene composites with nanoscale precision. ALD enables conformal, ultrathin TiO₂ coatings on graphene/rGO—down to a few nanometers—with excellent coverage and interfacial control; for example, Ban et al. deposited amorphous TiO₂ on high–surface-area rGO via ALD and demonstrated conformal films and improved electrochemical behavior [

59]. Likewise, Zhang et al. showed tunable ALD growth of TiOₓ on single-layer graphene (uniform amorphous layers at 60 °C vs. ~2 nm nanocrystals at 200 °C after ~20 cycles), directly evidencing the atomic-level control that lowers interfacial resistance and maximizes contact area [

60]. In the context of charge storage, Sun et al. anchored ALD-TiO₂ to graphene/CNT electrodes and reported pronounced pseudocapacitive response and cycling stability, underscoring ALD’s utility for supercapacitor-oriented hybrids [

61]. Complementarily, CVD routes have been used to integrate TiO₂ with graphene while controlling crystallinity and film continuity; recent overviews explicitly survey CVD as a viable pathway within TiO₂/graphene composite synthesis toolkits [

62]. Additional ALD studies on TiO₂–graphene further corroborate conformal coverage and thickness control for optimizing electrochemical interfaces [

63].

In summary, fabrication strategies for TiO₂–graphene hybrids range from solution-based approaches such as sol–gel and hydrothermal synthesis to advanced thin-film techniques such as ALD and CVD. Each method offers unique advantages: sol–gel ensures molecular-level mixing, hydrothermal routes yield high crystallinity and morphological control, in situ reduction provides strong interfacial bonding, electrochemical deposition enables scalable integration on electrodes, and ALD/CVD deliver precise nanoscale architectures. Rational selection of synthesis strategies, often involving combinations of these methods, is essential for designing high-performance TiO₂–graphene electrodes optimized for photoresponsive supercapacitors.

4.4. Examples of Enhanced Electrochemical Performance in Hybrids

Multiple, independently verified studies show that coupling TiO₂ with nanocarbon (graphene, rGO, CNTs) reliably boosts capacitance, rate handling and durability—often adding photo-responsiveness that further elevates performance. A representative early benchmark is the rGO–TiO₂ study by Xiang et al., who compared TiO₂ nanobelts (NBs) vs nanoparticles (NPs) anchored on reduced graphene oxide. At an rGO:TiO₂ mass ratio of 7:3, rGO–TiO₂ nanobelts delivered 225 F g⁻¹ (0.125 A g⁻¹), whereas the rGO–TiO₂ nanoparticles reached 62.8 F g⁻¹, evidencing the advantage of anisotropic TiO₂ morphologies when intimately interfaced with conductive graphene [

64]. To minimize interfacial resistance and preserve electron pathways, laminated “sandwich” electrodes place TiO₂ between rGO sheets. Ramadoss et al. built a porous rGO/TiO₂-nanorod/rGO laminate that reached 114.5 F g⁻¹ (5 mV s⁻¹ in 1 M Na₂SO₄) and retained >85% capacitance after 4000 cycles—performance attributed to efficient ion access and short electron paths through the rGO framework [

65]. Flexible layered films further highlight the utility of rGO as both a current collector and spacer to suppress graphene restacking. Kim et al. prepared stacked rGO/TiO₂ films by vacuum filtration; the composites delivered 286 F g⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹, ≈93% retention after 1000 cycles, and device-level energy/power densities of ≈39.7 Wh kg⁻¹ and ≈472 W kg⁻¹ in a symmetric cell—figures difficult to reach with TiO₂ alone [

66]. ALD offers another validated route: ultrathin, conformal TiO₂ grown directly on high–surface area carbon can switch on robust intercalation-type pseudocapacitance while keeping diffusion lengths short. Sun et al. anchored amorphous TiO₂ films to graphene aerogels (and CNTs) via ALD and observed specific capacitances of ~97.5 F g⁻¹ (graphene) and ~135 F g⁻¹ (CNTs) at 1 A g⁻¹ after 50 ALD cycles—well above the parent carbons—along with good cycling and an asymmetric device operating to 1.5 V in aqueous KOH [

61]. Three-dimensional scaffolds that co-embed TiO₂ and graphene also deliver strong gains by combining abundant ion-accessible porosity with conductive highways. Jiang et al. used a loofah-derived, 3D hierarchical carbon as a host for graphene and TiO₂; the best composite reached 250.8 F g⁻¹ at 2 A g⁻¹ with decent rate performance and >80% retention over 100 cycles [

67]. When the objective is an integrated photo-supercapacitor rather than a stand-alone electrode, coupling a TiO₂ photoanode with a graphene-based capacitor can preserve charge during light-off periods and reduce series resistance at the junction. In a three-electrode integrated device that paired a dye-sensitized TiO₂ photoanode with a PPy/rGO symmetric supercapacitor, Lau et al. measured 124.7 F g⁻¹ specific capacitance and 70.9% retention after 50 charge–discharge cycles under 100 mW cm⁻² illumination [

68]. The same design principles extend to other nanocarbon partners. For example, coating multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) with TiO₂ nanodots (binder-free) produced high areal capacitance with strong rate capability, emphasizing that intimate, conformal TiO₂–carbon contact—not just the carbon type—governs performance [

69]. Across these examples, several consistent, mechanism-level features explain the gains: (i) rGO/graphene provides fast, percolating electron pathways that mitigate TiO₂’s low conductivity; (ii) conformal or laminated architectures shorten Li⁺/H⁺/Na⁺ diffusion paths in TiO₂ and maximize electrochemically active surface; (iii) interfacial defect states and heterojunctions at TiO₂–graphene contacts suppress charge recombination and promote faradaic storage; and (iv) 3D porosity and flexibility (films/hydrogels) maintain electrolyte access under practical deformation or high current loads. Together, these effects lift specific/areal capacitance, preserve capacity at high rates, and enhance cycling life—while in integrated photo-supercapacitors, TiO₂’s photoactivity can directly assist charging under illumination. Building on the preceding discussion of interfacial contact, defect mediation, and charge-transport pathways, it is helpful to ground these concepts in a concrete dataset before moving on. As a performance example of nanocarbon-assisted TiO₂ electrodes,

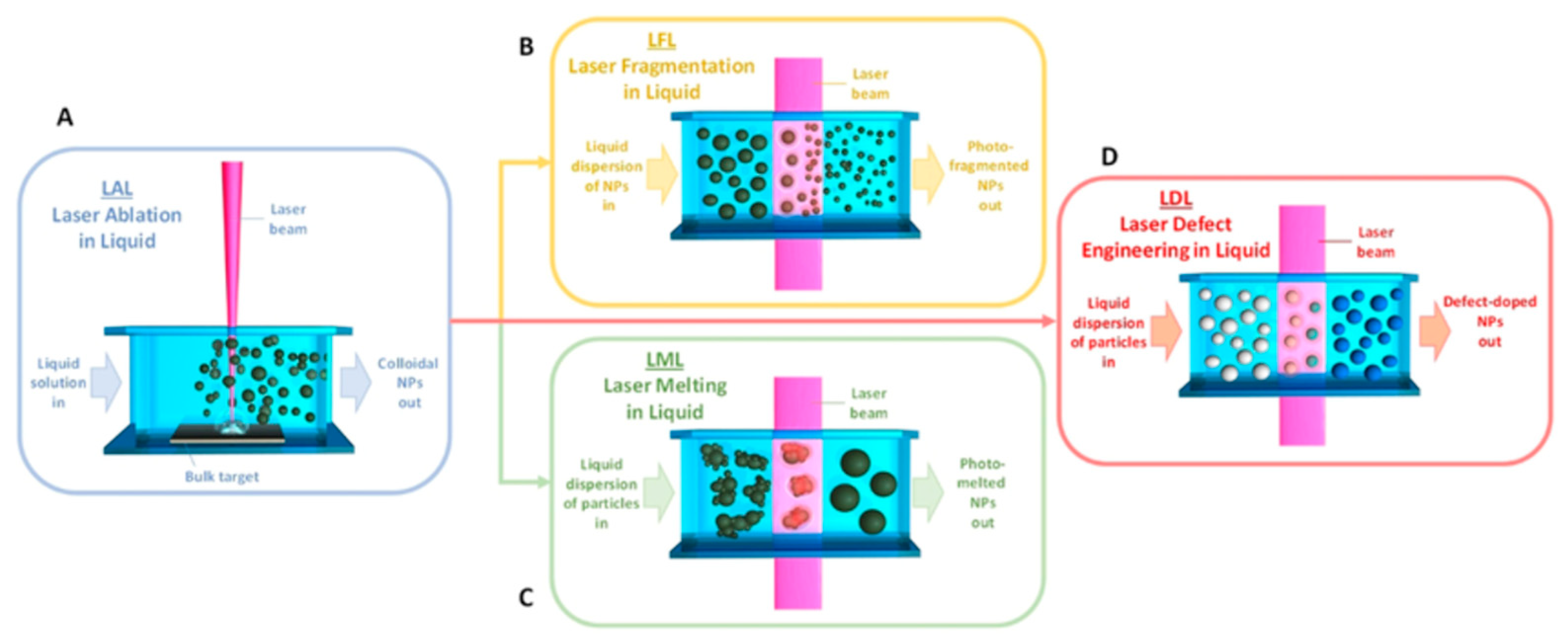

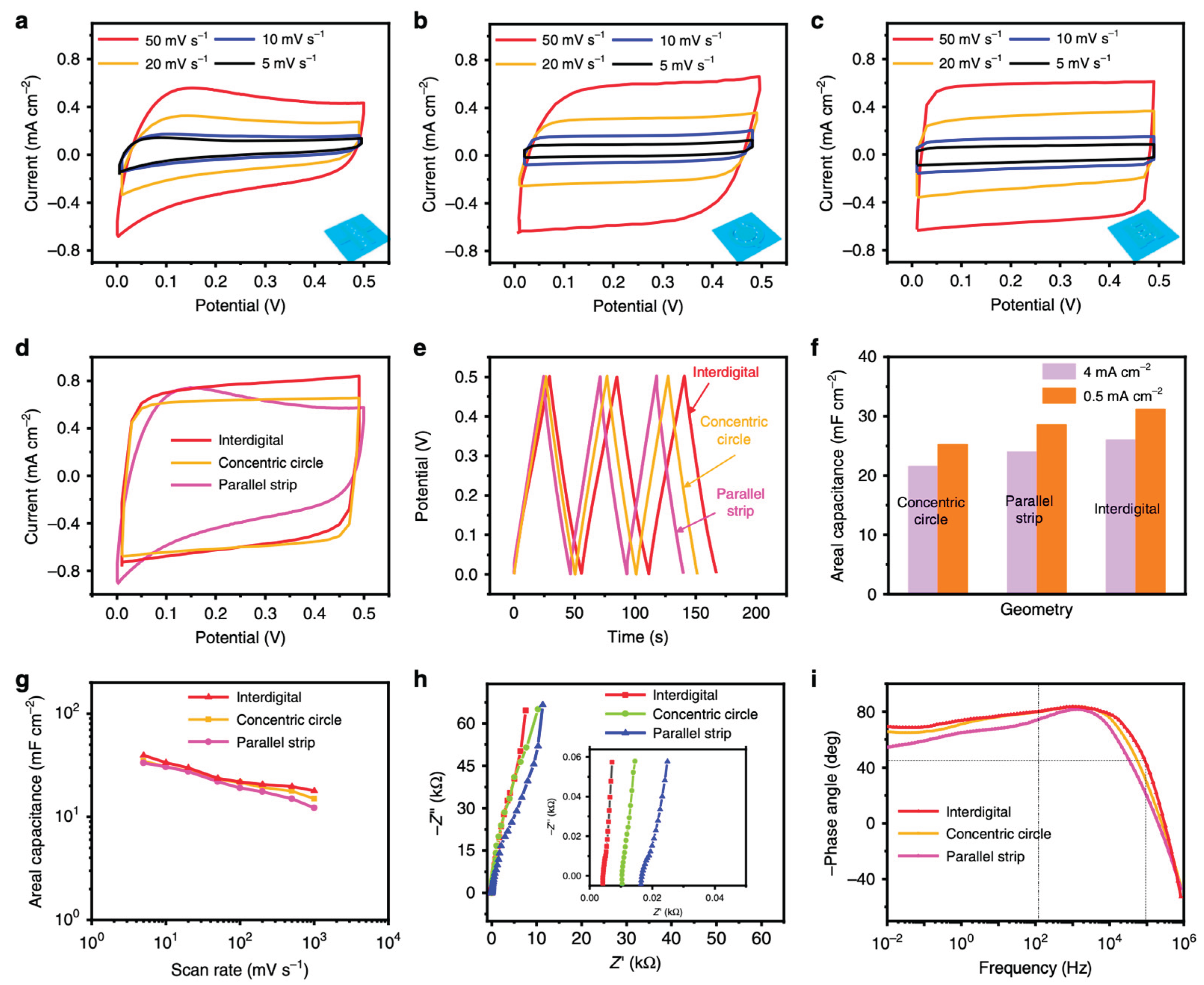

Figure 2 summarizes cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), cycling stability, and rate capability for bio-carbon/graphene/TiO₂ composites, highlighting how the carbon framework translates into measurable gains in charge storage and durability [

67].

5. Dual-Functionality: Energy Storage + Environmental Sensing

5.1. Principles of Capacitive Sensing: VOCs, Humidity and Gases

Capacitive sensing is fundamentally based on the modulation of dielectric properties and interfacial charge dynamics in response to external environmental stimuli. A capacitor consists of two conductive electrodes separated by a dielectric medium; when the dielectric constant or conductivity of this medium changes due to the adsorption of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), water molecules, or gaseous species, the capacitance is altered. This variation provides a direct transduction pathway for sensing. In supercapacitor-based systems, the electrodes already display high surface area and tunable surface chemistry, which can be exploited not only for charge storage but also for environmental detection. In the case of humidity sensing, the mechanism is primarily governed by the adsorption and desorption of water molecules at hydrophilic sites on the electrode or electrolyte interface. At low relative humidity, chemisorption dominates, with water molecules binding strongly to defect sites or oxygen-containing functional groups. As humidity increases, multilayer physisorption occurs, leading to the formation of a continuous water layer. This enhances proton conduction and dielectric polarization, thereby significantly modulating the capacitance response [

70]. For VOC detection, the principle involves changes in the dielectric constant of the medium surrounding the active electrode surface. Polar VOCs (e.g., ethanol, acetone) interact strongly with functional groups or porous frameworks, producing measurable capacitance variations. By tailoring electrode materials—such as incorporating graphene, metal oxides, or MXenes—the sensitivity and selectivity toward specific analytes can be enhanced. In particular, MXene-based electrodes show strong binding affinity for polar molecules due to surface-terminated functional groups such as –OH and –F, which makes them highly attractive for dual energy-storage and sensing platforms [

71]. Gas sensing, especially for small molecules such as NH₃, CO₂, or NO₂, is mainly governed by adsorption-induced charge transfer and polarization effects. The adsorption of electron-donating or electron-withdrawing gases modifies the interfacial charge distribution at the electrode, which can shift the local Fermi level and alter both double-layer capacitance and capacitance in porous frameworks. This behavior has been widely reported for two-dimensional materials such as graphene, where surface functionalization enables room-temperature NH₃ detection through specific electronic interactions with functional groups [

72]. For CO₂ detection, copper oxides and their derivatives exhibit strong potential as active sensing materials, since the adsorption of CO₂ molecules modifies the work function and surface states, leading to measurable capacitance changes under room-temperature conditions with low energy consumption [

73]. Similarly, NO₂ detection has been associated with the strong interaction of this oxidizing gas with surface defects or vacancies in semiconducting and photoactivated materials, which induces charge transfer and capacitance modulation. Photoactivated materials such as TiO₂, WO₃, or hybrid structures have shown fast and sensitive responses to low NO₂ concentrations under ambient conditions [

74].

Integrating these capacitive sensing mechanisms into supercapacitors enables the development of dual-functionality devices: systems capable of simultaneously storing electrical energy while acting as responsive sensors for environmental monitoring. This multifunctionality represents an emerging paradigm in the field of “smart supercapacitors” designed for the Internet of Things (IoT), where energy storage elements also serve as active sensing nodes.

5.2. Case Studies of TiO₂ or Graphene-Based Capacitive Sensors

Early thin-film TiO₂ devices established what makes capacitive humidity sensing so compelling: enormous dynamic range at room temperature and fast, repeatable response. Using glancing-angle deposition (GLAD), Steele, Brett and co-workers coated interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) with nanocolumnar TiO₂ and observed capacitance rising from ~1 nF to ~1 µF as RH increased from 2 % to 92 %, a hallmark of interfacial and dielectric-constant modulation in highly porous oxides. Their IEEE letter highlighted sub-second dynamics, while a follow-up study quantified ~270 ms response using similar GLAD films; critically, performance could be photocatalytically regenerated under UV after surface fouling—an early demonstration of self-cleaning in capacitive sensors (see

Table 1, rows 1–3) [

75]. Graphene-family dielectrics translate the same capacitive principle to 2D materials. Graphene oxide (GO), laminated over IDEs, behaves as a hygroscopic, nanolaminate dielectric whose permittivity and interfacial polarization rise with water uptake. Practical device builds report strong, frequency-dependent capacitance changes at room temperature and straightforward microfabrication. For instance, GO capacitors fabricated on common CMOS-style IDEs show large RH transfer functions across the ambient range, and GO/Ag-nanoparticle composites layer-by-layer onto IDEs achieve exceptionally high capacitance sensitivity (see

Table 1, rows 4–5) [

76]. Beyond humidity, graphene varactors enable

gas sensing by exploiting quantum capacitance. Adsorbates shift graphene’s Fermi level, changing the series combination of geometric and quantum capacitance. A canonical wireless vapor sensor coupled a metal-oxide-graphene varactor to an inductor and read humidity as a linear resonant-frequency shift of ~5.7 kHz per %RH over 1–97 % RH, cleanly tying the signal to quantum-capacitance modulation. Related work used graphene varactors to capacitively detect intercalated water between graphene and HfO₂, confirming rapid, reversible, room-temperature operation—useful design cues for capacitive gas sensing generally (

Table 1, rows 6–7) [

77]. Finally, recent NO₂ studies show that capacitive readout is not restricted to water vapor. Using CVD graphene with an enhanced geometrical capacitance back-gate stack, researchers measured capacitance changes tracking 1–100 ppm NO₂ at room temperature, explicitly attributing the signal to quantum-capacitance effects in graphene. This anchors feasibility for ppm-level, room-temperature capacitive gas sensors, complementing the humidity literature (

Table 1, row 8) [

78]. As summarized in

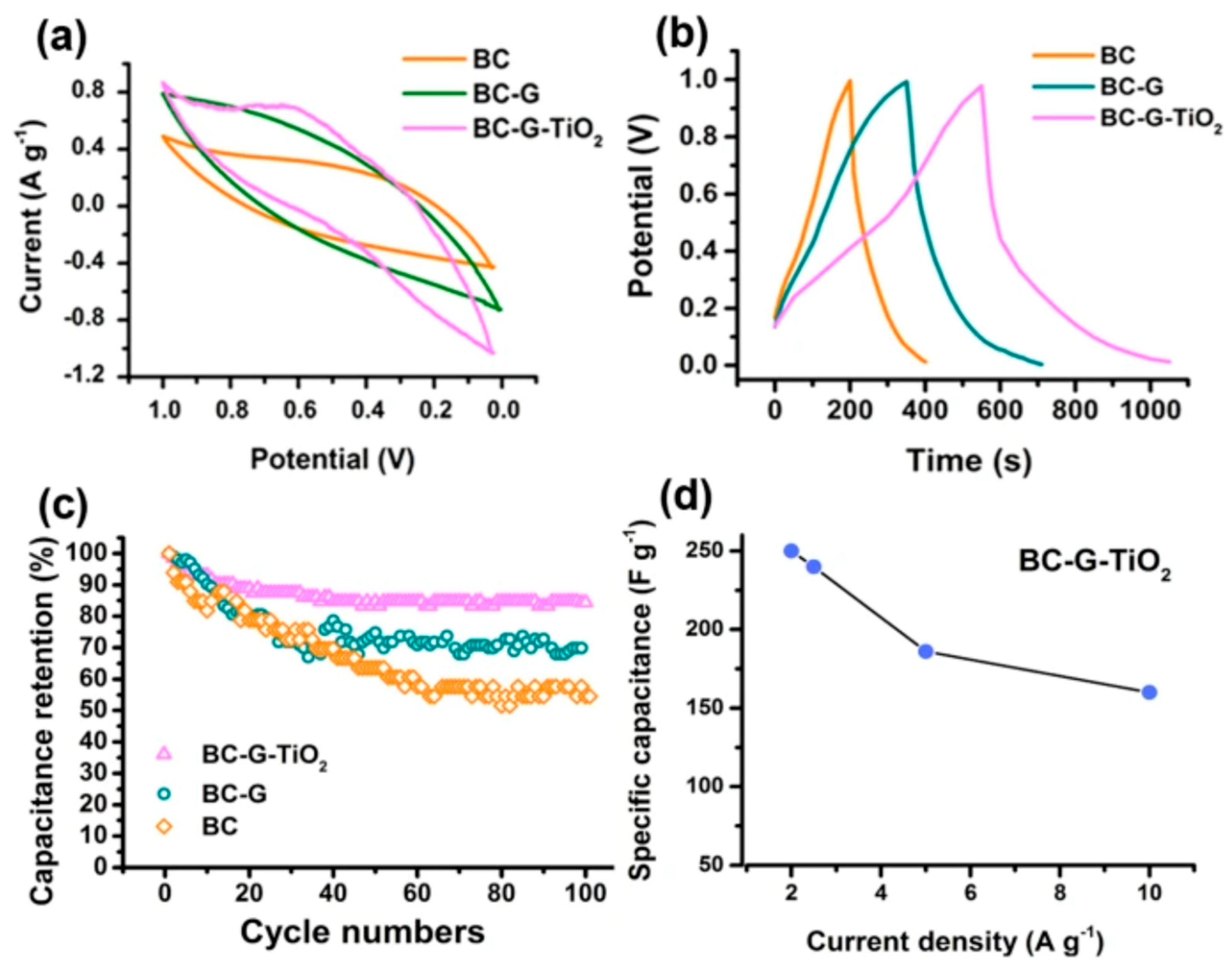

Table 1, these case studies collectively map the design space, porous TiO₂ dielectrics for large RH dynamic range and self-regeneration; GO (and GO-nanocomposites) for CMOS-friendly, high-sensitivity capacitive humidity transduction; and graphene varactors for quantum-capacitance-based humidity and gas detection at room temperature. Building on the device-level considerations above, it is useful to anchor the discussion with a frequency-tuned capacitive sensing example based on CVD graphene. To that end,

Figure 3 combines the device schematic and measurement configuration with representative performance metrics, linking architecture and readout to practical sensing outcomes. Specifically, the composite figure assembles the layout and measurement window together with dynamic response traces and the corresponding calibration curve for NO₂, illustrating how adsorption-induced doping modulates the measurable capacitance in a controlled frequency band.

5.3. Mechanisms of Analyte Interaction and Change in Capacitance

This section examines the mechanisms by which analytes modulate the measured capacitance in porous and low-dimensional electrodes engineered to serve concurrently as environmental sensors. In capacitive transduction, three interrelated pathways are predominant: (i) bulk and interfacial dielectric polarization within the sensing layer; (ii) ionic transport and electrical double-layer phenomena in saturated pores and at electrolyte–solid interfaces; and (iii) alterations of the electronic density of states—i.e., quantum capacitance—in materials such as graphene. The relative contribution of each pathway is governed by the electrode material (e.g., TiO₂ versus graphene/GO), the excitation frequency, the ambient humidity, and the applied bias conditions. At the lowest humidities, H₂O chemisorbs on oxide surfaces (e.g., TiO₂) to form surface hydroxyls; as RH rises, physisorbed water layers build up and percolate. The film’s effective permittivity increases and an interfacial (Maxwell–Wagner–Sillars, MWS) polarization emerges at boundaries between grains/pores and the adsorbed electrolyte, boosting the measured capacitance of interdigital or sandwich structures, especially at kHz–MHz where dipolar and space-charge relaxations are active. The same progression also enables protonic Grotthuss transport along water networks, further lowering impedance and amplifying the capacitive signature. These mechanisms—and their frequency dispersion and hysteresis—are well established in humidity-sensor reviews and dielectric spectroscopy of composites [

70,

86,

87]. In nanostructured TiO₂ (columns/chevrons made by GLAD), capillary condensation and ultrahigh surface area magnify both permittivity changes and MWS effects, yielding large ΔC/ΔRH and sub-second dynamics. Importantly, TiO₂’s photocatalysis under near-UV can “self-regenerate” the surface by oxidizing foulants and restoring hydroxyl chemistry, one reason GLAD TiO₂ capacitive RH sensors maintain stability without heaters [

75,

88,

89,

90]. For graphene and graphene oxide, two additional levers appear. First, GO swells and uptakes water, and its effective dielectric constant rises strongly with RH; both the volumetric water fraction and interlayer spacing control permittivity and, thus, the capacitance seen by interdigitated electrodes or microwave resonators. Ultrafast GO humidity sensors (tens of milliseconds) arise from GO’s “superpermeability” to water and rapid sorption/desorption kinetics [

82,

91]. Second, and unique to graphene, is quantum capacitance (Cq)—the contribution from its low electronic density of states. When analyte adsorption donates or withdraws charge (e.g., NO₂ as a strong acceptor), the Fermi level and DOS shift, changing Cq; since the measured capacitance is 1/C

tot=1/C

geom+1/C

q, even modest DOS changes can be read out as ΔC. This has been directly measured in graphene and exploited in varactor-based chemicapacitors and passive wireless resonators whose frequency follows humidity or gas concentration via Cq [

92,

93,

94,

95]. Gas molecules interact by physisorption or weak chemisorption with graphene and many oxides, producing adsorption-induced charge transfer and local polarization. On graphene, single-molecule events alter carrier density and, consequently, Cq (and conductance), with strong p-doping by NO₂ and weaker n- or p-doping for NH₃, CO, and H₂O depending on coverage and defects. These donor/acceptor trends are established by single-molecule detection experiments and first-principles studies [

96,

97]. When these sensing films are integrated into electrochemical capacitors, a further channel couples in: EDL formation and ion transport within flooded pores. Analytes that change the ionic strength, pH, viscosity, or surface charge (e.g., by deprotonating/adding hydroxyls) shift the EDL capacitance and its characteristic RC times. Porous electrodes therefore convert subtle changes in local electrolyte chemistry into measurable ΔC and phase shifts in impedance spectra; frequency helps disentangle dielectric/MWS processes (higher f) from diffusion/EDL processes (lower f) [

1,

98]. Pulling these pieces together suggests a practical picture for TiO₂ and graphene/GO sensors:

In TiO₂, ΔC is dominated by changes in dielectric permittivity (water uptake), MWS interfacial polarization, and (under UV) photocatalytic surface rejuvenation that resets hydroxyl chemistry, ideal for low-power, room-temperature RH sensing with regeneration instead of heaters [

89].

In GO films, swelling + permittivity increase control ΔC at low–mid frequencies, while fast sorption kinetics enable rapid response; at GHz, the humidity-dependent complex permittivity can also be read wirelessly [

91].

In graphene varactors, adsorption-induced doping perturbs Cq, enabling capacitive readout of water and certain gases, even wirelessly, without needing high temperatures [

77].

Two caveats matter for devices that co-store energy while sensing. First, bias history (state of charge) sets the operating Fermi level and the fraction of C

tot coming from Cq vs. geometric/EDL, so the same analyte can cause different ΔC at different biases. Second, analyte-driven capillary condensation and electrolyte uptake can transiently raise capacitance but also introduce hysteresis and drift, mitigated by porous architectures that favor fast desorption and, in TiO₂, by UV regeneration [

87,

88].

5.4. Design Criteria for Integrating Sensing and Storage in a Single Device