Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

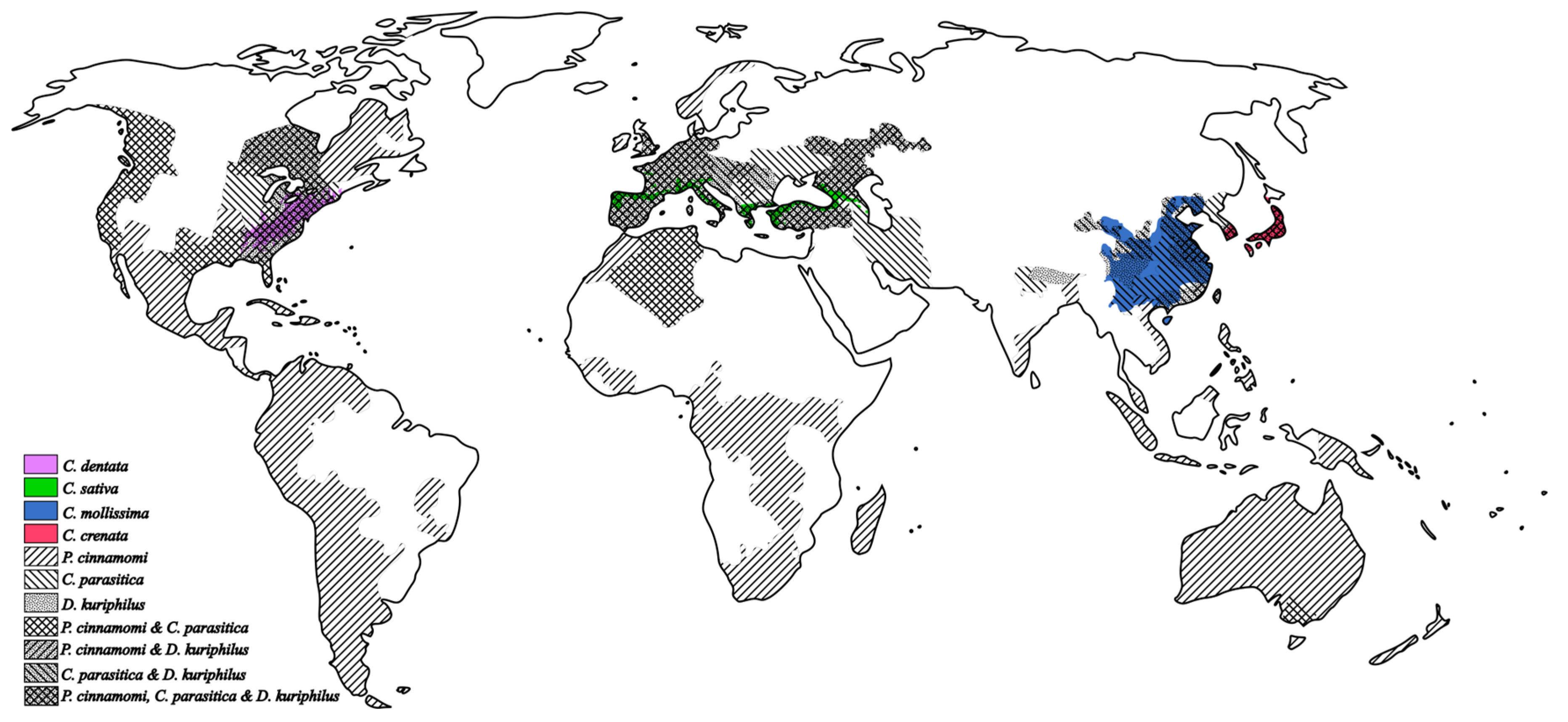

1. Introduction

2. Biotechnological Tools Applied to Chestnut

2.1. Classical and Assisted Genetic Improvement

2.1.1. Controlled Hybridization

2.1.2. Perspective for Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS)

2.2. Molecular and Genomic Approaches

2.2.1. Molecular Mechanisms of Castanea Defence Against Phytophthora cinnamomi

2.2.1.1. Genetic Basis of P. cinnamomi Resistance: Marker Development and Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Mapping

2.2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Castanea Defense Against Cryphonectria parasitica

2.2.2.1. Castanea sativa: Partial Tolerance or Susceptibility to Blight

| Methodology | Species | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Comparative transcriptomics |

C. crenata C. sativa |

C. crenata upregulates genes for pathogen perception, signaling, transcription factors, and defense metabolites. C. sativa shows limited and transient expression | [93,94] |

|

Molecular marker development |

C. sativa C. crenata |

43 EST-SSR markers identified from DEGs associated with host responses to infection | [110] supported by results in [94] |

| Genetic mapping | C. sativa x C. crenata | Interspecific linkage map enabled detection of QTLs for pathogen resistance on linkage groups E and K, co-localizing with defense-related genes | [111] supported by results in [110] |

|

Gene expression profiling |

C. crenata C. sativa C. sativa x C. crenata |

C. crenata shows high basal and induced expression of PR genes (e.g., RLKs, Cast_Gnk2-like), enabling early defense activation. C. sativa has lower expression, allowing rapid pathogen colonization | [93,95] in accordance with results in [97] |

|

Functional gene validation |

C. sativa C. dentata Quercus ilex Quercus suber Arabidopsis thaliana |

Cast_Gnk2-like relevant in Castanea and Quercus defense; CcAOS enhances tolerance in A. thaliana Ler-0 | [102,103,104,108] corroborated by results in [95] |

| Proteomics | C. sativa | C. sativa upon infection shows downregulation of proteins involved in SA signaling | [105]in accordance with results in [93,94] |

|

Histopathology and cellular studies |

C. sativa C. crenata |

C. crenata responds more efficiently than C. sativa; pathogen’s growth is restricted by early activation of callose deposition, HR-like cell death, cell wall thickening and accumulation of phenolic-like compounds. | [97] in accordance with results in [93,107] |

| Susceptibility gene expression analysis |

C. sativa C. crenata |

C. sativa upregulates pmr4 and dmr6 early in the infection, putatively contributing to suppressing SA defenses; putative callose accumulation via pmr4 is not sufficient to restrict pathogen growth | [107] in accordance with results in [97] |

|

Metabolite analysis |

C. sativa | Moderate warming enhances C. sativa resilience to pathogen. Surviving plants accumulate key phenolics (e.g., quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, ellagic acid), contributing to defense | [8] |

|

Physiological and biochemical assays |

C. sativa C. sativa x C. crenata |

C. sativa × C. crenata show early SA signaling, ABA antagonism, and oxidative stress recovery. C. sativa shows delayed JA signaling, high ABA, impaired metabolism, and weak antioxidant response | [96] in accordance with results in [95] |

- Lowering of photosynthetic pigments and augmentation of antioxidant enzyme activities (Ascorbate peroxidase (APX), Guaiacol peroxidase (POD), and Superoxide dismutase (SOD)).

- Accumulation of the stress markers proline (an amino acid that in stress conditions acts as an osmolyte, stabilizes proteins, and neutralizes ROS) and malondialdehyde (a marker of lipid peroxidation caused by oxidative stress levels in infected tissues).

2.2.2.2. Castanea mollissima: Robust Genetic Resistance

2.2.2.3. Breeding and Genomic Efforts

2.2.2.4. Transcriptomic Insights into Chestnut Blight Resistance

2.2.2.5. Metabolomic Insights into Chestnut Blight Resistance

2.2.3. Molecular Mechanisms of Castanea Defense Against Dryocosmus kuriphilus

2.2.4. Whole Genome Sequencing

| Methodology | Species / Genotypes | Results / Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Biological control Torymus sinensis |

Various (wild and cultivated) |

Effective in reducing infestations, but pest continues to spread | [21,154,155] |

| Phenotypic resistance screening |

C. sativa, C. crenata and Euro japanese hybrids |

7 resistant cultivars identified: C. sativa ‘Pugnenga’ & ‘Savoye’; C. crenata ‘Idae’; Hybrids ‘BB’, ‘Marlhac’, Maridonne’, ‘Vignols’ | [59,156] |

|

Histochemistry and gene expression |

‘BB’ (R) vs. ‘Madonna’ (C. sativa, S) |

Detection of H2O2 accumulation and strong GLP expression in R hybrid linked to HR | [157] |

| RNA-seq transcriptome analysis | ‘BB’ (R) vs. ‘Madonna’ (C. sativa, S) |

1,444 RGAs, 1,135 miRNA targets; upregulation of LRRs, WRKYs, AP2/ERFs, RAV1, LEA D29, RAPTOR1B; HR-related genes | [159] |

|

C. mollissima ‘Shuhe Wuyingli’ (PR) vs. ‘HongLi’ (S) |

Peroxidase pathway implicated; 4 TFs identified (CmbHLH130, CmWRKY31, CmNAC50, CmPHL12) | [160] | |

|

Genomic resources development |

C. sativa | Reference unigene catalog; ~7k SSRs and 335k SNP/INDELs | [159] |

| QTL mapping | Interspecific hybrids ‘BB’ x ‘Madonna’ |

Rdk1 locus explains 67–69% of resistance variance; candidate genes include metacaspase-1b and RPP13 receptor | [61] |

| GWAS | Greek C. sativa provenances (R) |

Region on Chr3 with 12 candidate genes (Cytochrome P450, UDP-GT, Rac-like GTPases); 21 SNPs identified | [62] |

| Genome sequencing | D. kuriphilus (pathogen) | High-quality reference genome published; enables host-pest interaction studies | [161] |

2.3. Micropropagation Techniques

2.3.1. Axillary Budding Micropropagation

2.3.2. Somatic Embryogenesis

2.4. Genetic Engineering Strategies

2.4.1. Traditional Genetic Transformation

2.4.2. New Plant Breeding Techniques

2.4.2.1. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Castanea Sativa

2.4.2.2. DNA-Free Genome Editing Using Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs)

2.5. Germplasm Conservation Through Cryopreservation

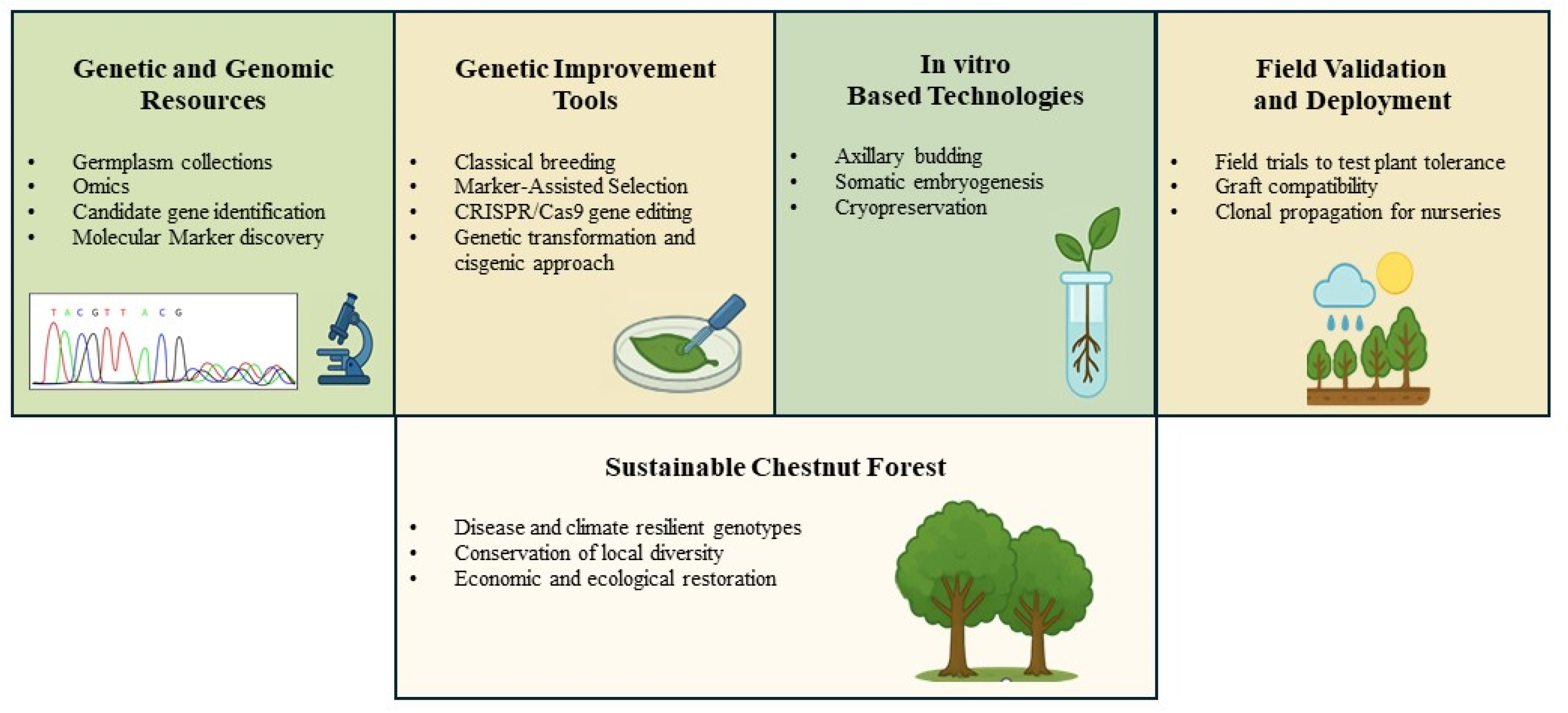

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robin, C. Francia. In Il castagno: Coltura, ambiente ed utilizazioni.; Bounous, G., Ed.; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2002; pp. 232–243.

- Conedera, M.; Tinner, W.; Krebs, P.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Castanea sativa in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., De Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 78–79.

- Fernandes, P.; Colavolpe, M.B.; Serrazina, S.; Costa, R.L. European and American Chestnuts: An Overview of the Main Threats and Control Efforts. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 951844. [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, F.; Merkle, S. Castanea Spp. Chestnut. In Biotechnology of fruit and nut crops; Litz, R., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 265–296.

- De Vasconcelos, M.C.; Bennett, R.N.; Rosa, E.A.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J. V Composition of European Chestnut ( Castanea Sativa Mill.) and Association with Health Effects: Fresh and Processed Products. J Sci Food Agric 2010, 90, 1578–1589. [CrossRef]

- Vannini, A.; Vettraino, A.; Anselmo, N. Patología. In Il Castagno. Coltura, Ambiente ed Utilizzazioni; Bounous, G., Ed.; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2002; pp. 103–111.

- Vannini, A.; Natili, G.; Anselmi, N.; Montaghi, A.; Vettraino, A.M. Distribution and Gradient Analysis of Ink Disease in Chestnut Forests. For Pathol 2010, 40, 73–86. [CrossRef]

- Dorado, F.J.; Alías, J.C.; Chaves, N.; Solla, A. Warming Scenarios and Phytophthora cinnamomi Infection in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). Plants 2023, 12, 556. [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M.; Prospero, S. A Modeling Approach to Determine Substitutive Tree Species for Sweet Chestnut in Stands Affected by Ink Disease. J For Res (Harbin) 2025, 36, 24. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M.E.; Balci, Y. Phytophthora Cinnamomi as a Contributor to White Oak Decline in Mid-Atlantic United States Forests. Plant Dis 2014, 98, 319–327. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M.E.; Balci, Y. Fine Root Dynamics of Oak Saplings in Response to Phytophthora Cinnamomi Infection under Different Temperatures and Durations. For Pathol 2015, 45, 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Weste, G.; Marks, G.C. The Biology of Phytophthora cinnamomi in Australasian Forests. Annu Rev Phytopathol 1987, 25, 207–229. [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, I.; Hardy, G.E.St.J.; Burgess, T.I. Phytophthora cinnamomi Exhibits Phenotypic Plasticity in Response to Cold Temperatures. Mycol Prog 2020, 19, 405–415. [CrossRef]

- EPPO Global Database. Phytophthora cinnamomi Distribution. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/PHYTCN/distribution (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Rigling, D.; Prospero, S. Cryphonectria Parasitica , the Causal Agent of Chestnut Blight: Invasion History, Population Biology and Disease Control. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Trapiello, E.; Rigling, D.; González, A.J. Occurrence of Hypovirus-Infected Cryphonectria parasitica Isolates in Northern Spain: An Encouraging Situation for Biological Control of Chestnut Blight in Asturian Forests. Eur J Plant Pathol 2017, 149, 503–514. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, I.; Pereira, E.; Moura, L.; Castro, J.P.; Gouveia, E. Natural Spread of Hypovirulence in Cryphonectria parasitica. A Case Study, Sergude – Minho – Portugal. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2015, 38, 264–274.

- Rodríguez-Molina, M. del C.; García-García, M.B.; Osuna, M.D.; Gouveia, E.; Serrano-Pérez, P. Various Population Structures of Cryphonectria parasitica in Cáceres (Spain) Determine the Feasibility of the Biological Control of Chestnut Blight with Hypovirulent Strains. Agronomy 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1208 2023, 13, 1208. [CrossRef]

- Quinto, J.; Wong, M.E.; Boyero, J.R.; Vela, J.M.; Aguirrebengoa, M. Population Dynamics and Tree Damage of the Invasive Chestnut Gall Wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus, in Its Southernmost European Distributional Range. Insects 2021, 12, 900. [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Pedrazzoli, F.; Tognetti, R.; Vecchione, A.; Zulini, L.; Maresi, G. Ecophysiological Responses and Vulnerability to Other Pathologies in European Chestnut Coppices, Heavily Infested by the Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp. For Ecol Manage 2014, 314, 38–49. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, E.; Bellosi, B.; Quacchia, A.; Conedera, M. Assessing the Impact of Dryocosmus kuriphilus on the Chestnut Tree: Branch Architecture Matters. J Pest Sci (2004) 2018, 91, 189–202. [CrossRef]

- EPPO Dryocosmus kuriphilus. EPPO Datasheets on Pests Recommended for Regulation. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Savill, P.; Evans, J.; Auclair, D.; Falck, J. Genetics, Silviculture and the Promotion of Wood Quality (Forestry Commission Bulletin 126); Forestry Commission: Edinburgh, UK, 2005;

- Vieitez, A.M.; Corredoira, E.; Martínez, M.T.; San-José, M.C.; Sánchez, C.; Valladares, S.; Vidal, N.; Ballester, A. Application of Biotechnological Tools to Quercus Improvement. Eur J For Res 2012, 131, 519–539.

- Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Micropropagation of Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). In Cell and Tissue Culture in Forestry; Bonga, J.M., Durzan, D.J., Eds.; Springer, 1986; Vol. 1, pp. 127–146.

- Alcaide, F.; Solla, A.; Cherubini, M.; Mattioni, C.; Cuenca, B.; Camisón, Á.; Martín, M.Á. Adaptive Evolution of Chestnut Forests to the Impact of Ink Disease in Spain. J Syst Evol 2020, 58, 504–516. [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M.; Tinner, W.; Krebs, P.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G. Castanea Sativa in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage And. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publ. Off. EU: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e0125e0+.

- Sandercock, A.M.; Westbrook, J.W.; Zhang, Q.; Johnson, H.A.; Saielli, T.M.; Scrivani, J.A.; Fitzsimmons, S.F.; Collins, K.; Perkins, M.T.; Craddock, J.H.; et al. Frozen in Time: Rangewide Genomic Diversity, Structure, and Demographic History of Relict American Chestnut Populations. Mol Ecol 2022, 31, 4640–4655. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Matsui, T. PRDB: Phytosociological Relevé Database, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute Available online: http://www.ffpri.go.jp/labs/prdb/index.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Dane, F.; Lang, P.; Huang, H.; Fu, Y. Intercontinental Genetic Divergence of Castanea Species in Eastern Asia and Eastern North America. Heredity (Edinb) 2003, 91, 314–321. [CrossRef]

- EPPO Global Database. Cryphonectria parasitica Distribution. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/ENDOPA/distribution (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- EPPO Global Database. Dryocosmus Kuriphilus Distribution. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/DRYCKU/distribution (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Inkscape Project. Inkscape 2025 Version 1.4.2 (f4327f4, 2025/05/13). Available online: https://inkscape.org.

- Grattapaglia, D.; Plomion, C.; Kirst, M.; Sederoff, R.R. Genomics of Growth Traits in Forest Trees. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2009, 12, 148–156. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Merkle, S.A.; Martínez, M.T.; Toribio, M.; Canhoto, J.M.; Correia, S.I.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Non-Zygotic Embryogenesis in Hardwood Species. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2019, 38, 29–97. [CrossRef]

- Grattapaglia, D.; Resende, M.D. V. Genomic Selection in Forest Tree Breeding. Tree Genet Genomes 2011, 7, 241–255. [CrossRef]

- Pike, C.C.; Koch, J.; Nelson, C.D. Breeding for Resistance to Tree Pests: Successes, Challenges, and a Guide to the Future. J For 2021, 119, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Gallastegui, C. Técnica de La Hibridación Artificial Del Castaño. Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural 1926, 26, 88–94.

- Urquijo, P. Aspectos de La Obtención de Híbridos Resistentes a La Enfermedad Del Castaño. Boletín de Patología Vegetal y Entomología Agrícola 1944, XIII, 447–462.

- Lafitte, G. Le Châtaignier Japonais En Pays Basque. Mendionde 69 1946.

- Gomes Guerreiro, M. Acerca Do Uso Da Análise Discriminatória: Comparação Entre Duas Castas de Castanhas. – Sep. Das Publicações Da Direcção Geral Dos Serviços Estais e Aquícolas, Vol. XV, Tomo I e II. 1948, 137–151.

- Bagnaresi, U. Osservazioni Morfo-Biologiche Sulle Provenienze Di Castagno Giapponese Coltivate in Italia. Pubblicazione n. 3, Centro Studio Sul Castagno (C.N.R.), Firenze. La Ricerca Scientifica (Suppl.) 1956, 26, 7–48.

- Schad, C.; Solignat, G.; Grente, J.; Venot, P. Recherches Sur Le Chataignier a La Station de Brive. Annales de L’amélioration des plantes 1952, 3, 369–458.

- Taveira-Fernándes, C. Aspects de l’ameliorationdu Chataignier Pour La Résistance a La Maladie de l’encre. In Proceedings of the In Actas III Congr Un Fitopat. Medit; Oeiras, Portugal, 1972; pp. 313–320.

- Burnham, C.R.; Rutter, P.A.; French, D.W. Breeding Blight-Resistant Chestnuts. In Plant Breeding Reviews; Wiley, 1986; pp. 347–397.

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Fernandez-Lopez, J. Propagation of Chestnut Cultivars by Grafting: Methods, Rootstocks and Plant Quality. Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 1997, 72, 731–739. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Santos, C.; Tavares, F.; Machado, H.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Kubisiak, T.; Nelson, C.D. Mapping and Transcriptomic Approches Implemented for Understanding Disease Resistance to Phytophthora cinammomi in Castanea Sp. BMC Proc 2011, 5, O18. [CrossRef]

- Míguez-Soto, B.; López-Villamor, A.; Fernández-López, J. Additive and Non-Additive Genetic Parameters for Multipurpose Traits in a Clonally Replicated Incomplete Factorial Test of Castanea Spp. Tree Genet Genomes 2016, 12, 47. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Amaral, A.; Colavolpe, B.; Balonas, D.; Serra, M.; Pereira, A.; Costa, R.L. Propagation of New Chestnut Rootstocks with Improved Resistance to Phytophthora cinnamomi – New Cast Rootstocks. Silva Lusit 2020, 28, 15–29. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lopez, J. Identification of the Genealogy of Interspecific Hybrids between Castanea sativa, Castanea crenata and Castanea mollissima. For Syst 2011, 20, 65–80. [CrossRef]

- Hennion, B. CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN FRANCE: REVIEW, PERSPECTIVES. Acta Hortic 2010, 866, 493–497. [CrossRef]

- Serdar, Ü.; Saito, T.; Cuenca, B.; Akyüz, B.; Laranjo, J.G.; Beccaro, G.; Bounous, G.; Costa, R.L.; Fernandes, P.; Mellano, M.G.; et al. Advances in Cultivation of Chestnuts. In; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited, 2019; pp. 349–388.

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Coutinho, J.P.; Peixoto, F.; Araújo Alves, J. Ecologia Do Castanheiro (C. sativa Mill.) . In Castanheiros; Gomes-Laranjo, J., Ferreira-Cardoso, J., Portela, E., G.-Abreu, C., Eds.; UTAD: Vila Real, 2007; pp. 109–149.

- Martins, L.; Anjos, R.; Costa, R.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Colutad. Um Clone de Castanheiro Resistente À Doença Da Tinta. In Castanheiros. Técnicas e Práticas; Gomes-Laranjo, J., Peixoto, F., Ferreira-Cardoso, J., Eds.; Pulido Consulting - Indústria Criativa and Universidade Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro: Vila Real, 2009; pp. 135–142.

- Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Serrazina, S.; Gomes, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Correia, I.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Duarte, S.; Bragança, H.; Fevereiro, P.; et al. Comprehension of Resistance to Diseases in Chestnut. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2016, 39, 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Amaral, A.; Colavolpe, B.; Pereira, A.; Costa, R. Avaliação agronómica de genótipos de castanheiro selecionados do programa de melhoramento genético para a resistência à tinta. Vida Rural. 2021, pp. 76–82.

- Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Correia, I.; Gomes, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Costa, R. Phenotyping Castanea Hybrids for Phytophthora cinnamomi Resistance. Plant Pathol 2015, 64, 901–910. [CrossRef]

- Breisch, H.; Boutitie, A.; Reyne, J.; Salesses, G.; Vaysse, P. Châtaignes et Marrons; FRA : CTIFL Centre Technique des Fruits et Légumes: Paris, 1995;

- Sartor, C.; Dini, F.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Mellano, M.G.; Beccaro, G.L.; Alma, A.; Quacchia, A.; Botta, R. Impact of the Asian Wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Yasumatsu) on Cultivated Chestnut: Yield Loss and Cultivar Susceptibility. Sci Hortic 2015, 197, 454–460. [CrossRef]

- Paglietta, R. ‘Lusenta’ a New Early Ripening Euro Japanese Chestnut. In Proceedings of the World Chestnut Industry Conference; Wallace, R.D., Spinella, L.G., Eds.; Chestnut Marketing Assoc., Alachua, Florida, USA: Morgantown, West Virginia, 1992; pp. 10–11.

- Torello Marinoni, D.; Nishio, S.; Valentini, N.; Shirasawa, K.; Acquadro, A.; Portis, E.; Alma, A.; Akkak, A.; Pavese, V.; Cavalet-Giorsa, E.; et al. Development of High-Density Genetic Linkage Maps and Identification of Loci for Chestnut Gall Wasp Resistance in Castanea Spp. Plants 2020, 9, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, M.; Pollegioni, P.; Ciolfi, M.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Beritognolo, I. Identification of a Unique Genomic Region in Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) That Controls Resistance to Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp Dryocosmus Kuriphilus Yasumatsu. Plants 2024, 13, 1355. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.W.; Zhang, Q.; Mandal, M.K.; Jenkins, E. V.; Barth, L.E.; Jenkins, J.W.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Holliday, J.A. Optimizing Genomic Selection for Blight Resistance in American Chestnut Backcross Populations: A Trade-off with American Chestnut Ancestry Implies Resistance Is Polygenic. Evol Appl 2019, 13, 31–47. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C. Anatomical Changes during Chestnut (Castanea Mollissima BL.) Gall Development Stages Induced by the Gall Wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Plants 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1766 2024, 13, 1766. [CrossRef]

- Camisón, Á.; Martín, M.Á.; Flors, V.; Sánchez-Bel, P.; Pinto, G.; Vivas, M.; Rolo, V.; Solla, A. Exploring the Use of Scions and Rootstocks from Xeric Areas to Improve Drought Tolerance in Castanea sativa Miller. Environ Exp Bot 2021, 187, 104467. [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Liang, L.; Paillet, F.L.; Steiner, K.C.; Fang, J.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hebard, F. V. Modelling Chestnut Biogeography for American Chestnut Restoration. Divers Distrib 2012, 18, 754–768. [CrossRef]

- Míguez-Soto, B.; Fernández-Cruz, J.; Fernández-López, J. Mediterranean and Northern Iberian Gene Pools of Wild Castanea Sativa Mill. Are Two Differentiated Ecotypes Originated under Natural Divergent Selection. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0211315. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.R.; Santos, J.A.; Silva, A.P.; Fraga, H. Influence of Climate Change on Chestnut Trees: A Review. Plants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 1463 2021, 10, 1463. [CrossRef]

- Alcaide, F.; Solla, A.; Mattioni, C.; Castellana, S.; Martín, M.Á. Adaptive Diversity and Drought Tolerance in Castanea Sativa Assessed through EST-SSR Genic Markers. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2019, 92, 287–296. [CrossRef]

- Dorado, F.J.; Solla, A.; Alcaide, F.; Martín, M.Á. Assessing Heat Stress Tolerance in Castanea sativa. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2022, 95, 667–677. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Rial, A.; Castro, P.; Solla, A.; Martín, M.A.; Die, J.V. Decoding Drought Tolerance from a Genomic Approach in Castanea Sativa Mill. Plant Genome 2025.

- Solla, A.; Dorado, F.J.; González, R.; Giraldo-Chaves, L.B.; Cubera, E.; Rocha, G.; Martín, C.; Martín, E.; Cuenca, B.; del Pozo, J.L.; et al. Chestnut Trees ( Castanea sativa Mill.) for Climate Change. Acta Hortic 2024, 1, 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, D.; Akkak, A.; Bounous, G.; Edwards, K.J.; Botta, R. Development and Characterization of Microsatellite Markers in Castanea sativa (Mill.). Molecular Breeding 2003, 11, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Buck, E.J.; Hadonou, M.; James, C.J.; Blakesley, D.; Russell, K. Isolation and Characterization of Polymorphic Microsatellites in European Chestnut ( Castanea sativa Mill.). Mol Ecol Notes 2003, 3, 239–241. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.A.; Alvarez, J.B.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Villani, F.; Martin, L.M. Identification and Characterisation of Traditional Chestnut Varieties of Southern Spain Using Morphological and Simple Sequence Repeat (SSRs) Markers. Annals of Applied Biology 2009, 154, 389–398. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.A.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Taurchini, D.; Villani, F. Genetic Characterisation of Traditional Chestnut Varieties in Italy Using Microsatellites (Simple Sequence Repeats) Markers. Annals of Applied Biology 2010, 157, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Torello Marinoni, D.; Akkak, A.; Beltramo, C.; Guaraldo, P.; Boccacci, P.; Bounous, G.; Ferrara, A.M.; Ebone, A.; Viotto, E.; Botta, R. Genetic and Morphological Characterization of Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Germplasm in Piedmont (North-Western Italy). Tree Genet Genomes 2013, 9, 1017–1030. [CrossRef]

- Gobbin, D.; Hohl, L.; Conza, L.; Jermini, M.; Gessler, C.; Conedera, M. Microsatellite-Based Characterization of the Castanea sativa Cultivar Heritage of Southern Switzerland. Genome 2007, 50, 1089–1103. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Barreneche, T.; Mattioni, C.; Villani, F.; Díaz-Hernández, M.B.; Martín, L.M.; Martín, Á. Database of European Chestnut Cultivars and Definition of a Core Collection Using Simple Sequence Repeats. Tree Genet Genomes 2017, 13, 114. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Costa, R.M.L.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Ciordia-Ara, M.; Ribeiro, C.A.M.; Borges, O.; Barreneche, T. Chestnut Cultivar Diversification Process in the Iberian Peninsula, Canary Islands, and Azores. Genome 2011, 54, 301–315. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Costa, R.M.L.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Ribeiro, C.A.M.; da Silva, M.F.S.; Manzano, G.; Barreneche, T. Variation in Grafted European Chestnut and Hybrids by Microsatellites Reveals Two Main Origins in the Iberian Peninsula. Tree Genet Genomes 2010, 6, 701–715. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Barreneche, T.; Mattioni, C.; Villani, F.; Díaz-Hernández, B.; Martín, L.M.; Robles-Loma, A.; Cáceres, Y.; Martín, A. Instant Domestication Process of European Chestnut Cultivars. Annals of Applied Biology 2019, 174, 74–85. [CrossRef]

- Nunziata, A.; Ruggieri, V.; Petriccione, M.; De Masi, L. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms as Practical Molecular Tools to Support European Chestnut Agrobiodiversity Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, Vol. 21, Page 4805 2020, 21, 4805. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.A.; Monedero, E.; Martín, L.M. Genetic Monitoring of Traditional Chestnut Orchards Reveals a Complex Genetic Structure. Ann For Sci 2017, 74, 15. [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Angela Martín, M.; Pollegioni, P.; Cherubini, M.; Villani, F. Microsatellite Markers Reveal a Strong Geographical Structure in European Populations of Castanea sativa (Fagaceae): Evidence for Multiple Glacial Refugia. Am J Bot 2013, 100, 951–961. [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M.A.; Chiocchini, F.; Cherubini, M.; Gaudet, M.; Pollegioni, P.; Velichkov, I.; Jarman, R.; Chambers, F.M.; Paule, L.; et al. Landscape Genetics Structure of European Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill): Indications for Conservation Priorities. Tree Genet Genomes 2017, 13, 39. [CrossRef]

- Castellana, S.; Martin, M.Á.; Solla, A.; Alcaide, F.; Villani, F.; Cherubini, M.; Neale, D.; Mattioni, C. Signatures of Local Adaptation to Climate in Natural Populations of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) from Southern Europe. Ann For Sci 2021, 78, 27. [CrossRef]

- Casasoli, M.; Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Villani, F. A Genetic Linkage Map of European Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Based on RAPD, ISSR and Isozyme Markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2001, 102, 1190–1199. [CrossRef]

- Casasoli, M.; Pot, D.; Plomion, C.; Monteverdi, M.C.; Barreneche, T.; Lauteri, M.; Villani, F. Identification of QTLs Affecting Adaptive Traits in Castanea Sativa Mill. Plant Cell Environ 2004, 27, 1088–1101. [CrossRef]

- Casasoli, M.; Derory, J.; Morera-Dutrey, C.; Brendel, O.; Porth, I.; Guehl, J.M.; Villani, F.; Kremer, A. Comparison of Quantitative Trait Loci for Adaptive Traits Between Oak and Chestnut Based on an Expressed Sequence Tag Consensus Map. Genetics 2006, 172, 533–546. [CrossRef]

- Barreneche, T.; Casasoli, M.; Russell, K.; Akkak, A.; Meddour, H.; Plomion, C.; Villani, F.; Kremer, A. Comparative Mapping between Quercus and Castanea Using Simple-Sequence Repeats (SSRs). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2004, 108, 558–566. [CrossRef]

- Durand, J.; Bodénès, C.; Chancerel, E.; Frigerio, J.-M.; Vendramin, G.; Sebastiani, F.; Buonamici, A.; Gailing, O.; Koelewijn, H.-P.; Villani, F.; et al. A Fast and Cost-Effective Approach to Develop and Map EST-SSR Markers: Oak as a Case Study. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 570. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Pimentel, D.; Ramiro, R.S.; Silva, M. do C.; Fevereiro, P.; Costa, R.L. Dual Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Early Induced Castanea Defense-Related Genes and Phytophthora cinnamomi Effectors. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Pesquita, C.; Vicentini, R.; Pais, M.S.; Sebastiana, M.; Costa, R. Castanea Root Transcriptome in Response to Phytophthora cinnamomi Challenge. Tree Genet Genomes 2015, 11, 6. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Duarte, S.; Tedesco, S.; Fevereiro, P.; Costa, R.L. Expression Profiling of Castanea Genes during Resistant and Susceptible Interactions with the Oomycete Pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi Reveal Possible Mechanisms of Immunity. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 515. [CrossRef]

- Camisón, Á.; Monteiro, P.; Dorado, F.J.; Sánchez-Bel, P.; Leitão, F.; Meijón, M.; Pinto, G. Choosing the Right Signaling Pathway: Hormone Responses to Phytophthora cinnamomi during Compatible and Incompatible Interactions with Chestnut (Castanea Spp.). Tree Physiol 2025, 45. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Machado, H.; Silva, M. do C.; Costa, R.L. A Histopathological Study Reveals New Insights Into Responses of Chestnut (Castanea Spp.) to Root Infection by Phytophthora cinnamomi. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 345–355. [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, T.; Sawano, Y.; Miyazono, K.I.; Hatano, K.I.; Tanokura, M. Crystallization and Preliminary X-Ray Analysis of Ginkbilobin-2 from Ginkgo Biloba Seeds: A Novel Antifungal Protein with Homology to the Extracellular Domain of Plant Cysteine-Rich Receptor-like Kinases. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2007, 63, 737–739. [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Wadhwani, P.; Mühlhäuser, P.; Liu, Q.; Riemann, M.; Ulrich, A.S.; Nick, P. An Antifungal Protein from Ginkgo Biloba Binds Actin and Can Trigger Cell Death. Protoplasma 2016, 253, 1159–1174. [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, T.; Hatano, K.I.; Miyauchi, Y.; Suwa, Y.I.; Sawano, Y.; Tanokura, M. A Secreted Protein with Plant-Specific Cysteine-Rich Motif Functions as a Mannose-Binding Lectin That Exhibits Antifungal Activity. Plant Physiol 2014, 166, 766–778. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Martínez, M.T.; Fernandes, P.; Colavolpe, B.; Dias, F.; Conde, P.; Malhó, R.; Corredoira, E.; Costa, R.L. Castanea crenata Ginkbilobin2-like as a Resistance Gene to Phytophthora cinnamomi Infection. Acta Hortic 2024, 1, 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Martínez, M.T.; Cano, V.; Malhó, R.; Costa, R.L.; Corredoira, E. Genetic Transformation of Quercus ilex Somatic Embryos with a Gnk2-like Protein That Reveals a Putative Anti-Oomycete Action. Plants 2022, 11, 304. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Martínez, M.; Soudani, S.; Candeias, G.; Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Piñeiro, P.; Malhó, R.; Costa, R.L.; Corredoira, E. Overexpression of Ginkbilobin-2 Homologous Domain Gene Improves Tolerance to Phytophthora cinnamomi in Somatic Embryos of Quercus Suber. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 19357. [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, L.; Fernandes, P.; Oakes, A.; Stewart, K.; Powell, W. Transformation of American Chestnut (Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh) Using Rita® Temporary Immersion Bioreactors and We Vitro Containers. Forests 2020, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Fernández, I.; Milenković, I.; Berka, M.; Černý, M.; Tomšovský, M.; Brzobohatý, B.; Kerchev, P. Integrated Proteomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Phytophthora cinnamomi Attack on Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa) Reveals Distinct Molecular Reprogramming Proximal to the Infection Site and Away from It. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8525. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic Acid: The Roles in Plant Immunity and Crosstalk with Other Hormones. J Integr Plant Biol 2025, 67, 773–785. [CrossRef]

- Pavese, V.; Moglia, A.; Gonthier, P.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Cavalet-Giorsa, E.; Botta, R. Identification of Susceptibility Genes in Castanea sativa and Their Transcription Dynamics Following Pathogen Infection. Plants 2021, 10, 913. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Machado, H.; Costa, R.L.; Duque, P.; Malhó, R. Expression of Castanea crenata Allene Oxide Synthase in Arabidopsis Improves the Defense to Phytophthora cinnamomi. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 149. [CrossRef]

- Langin, G.; González-Fuente, M.; Üstün, S. The Plant Ubiquitin-Proteasome System as a Target for Microbial Manipulation. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2023, 61, 351–375. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Serrazina, S.; Nelson, C.D.; Costa, R. Development and Characterization of EST-SSR Markers for Mapping Reaction to Phytophthora cinnamomi in Castanea Spp. Sci Hortic 2015, 194, 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Nelson, C.D.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Machado, H.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Costa, R.L. First Interspecific Genetic Linkage Map for Castanea sativa x Castanea crenata Revealed QTLs for Resistance to Phytophthora cinnamomi. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0184381. [CrossRef]

- Zhebentyayeva, T.N.; Sisco, P.H.; Georgi, L.L.; Jeffers, S.N.; Perkins, M.T.; James, J.B.; Hebard, F. V.; Saski, C.; Nelson, C.D.; Abbott, A.G. Dissecting Resistance to Phytophthora cinnamomi in Interspecific Hybrid Chestnut Crosses Using Sequence-Based Genotyping and QTL Mapping. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1594–1604. [CrossRef]

- Lovat, C.A.; Donnelly, D.J. Mechanisms and Metabolomics of the Host–Pathogen Interactions between Chestnut (Castanea Species) and Chestnut Blight (Cryphonectria parasitica). For Pathol 2019, 49, e12562. [CrossRef]

- Antipova, T. V.; Zhelifonova, V.P.; Litovka, Y.A.; Baskunov, B.P.; Noskov, A.E.; Timofeyev, A.A.; Pavlov, I.N. Secondary Metabolites of Phytopathogenic Cryphonectria parasitica (Murrill) and Their in Vitro Phytotoxicity. Journal of Plant Pathology 2025, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ježić, M.; Nuskern, L.; Peranić, K.; Popović, M.; Ćurković-Perica, M.; Mendaš, O.; Škegro, I.; Poljak, I.; Vidaković, A.; Idžojtić, M. Regional Variability of Chestnut (Castanea sativa) Tolerance Toward Blight Disease. Plants 2024, 13, 3060. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, G.E.; Szőke, L.; Tóth, B.; Kovács, B.; Bojtor, C.; Illés, Á.; Radócz, L.; Moloi, M.J.; Radócz, L. The Physiological and Biochemical Responses of European Chestnut (Castanea sativa L.) to Blight Fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica (Murill) Barr). Plants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 2136 2021, 10, 2136. [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, P.; Pfeiffer, P.; Zhang, L.; Van Alfen, N.K. Transcriptional Repression of Specific Host Genes by the Mycovirus Cryphonectria Hypovirus 1. J Virol 1996, 70, 1137–1142. [CrossRef]

- Heiniger, U.; Rigling, D. BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF CHESTNUT BLIGHT IN EUROPE. Annu Rev Phytopathol 1994, 32, 581–599. [CrossRef]

- Bolvanský, M.; Adamčíková, K.; Kobza, M. Screening Resistance to Chestnut Blight in Young Chestnut Trees Derived from Castanea sativa × C. crenata Hybrids. FOLIA OECOLOGICA 2014, 41, 1–7.

- Chira, D.; Teodorescu, R.; Mantale, C.; Chira, F.; Isaia, G.; Achim, G.; Scutelnicu, A.; Botu, M. Testing Chestnut Hybrids for Resistance to Cryphonectria parasitica. Acta Hortic 2018, 1220, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- van Loon, L.C.; Rep, M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Significance of Inducible Defense-Related Proteins in Infected Plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2006, 44, 135–162. [CrossRef]

- Schafleitner, R.; Wilhelm, E. Effect of Virulent and Hypovirulent Cryphonectria parasitica (Murr.) Barr on the Intercellular Pathogen Related Proteins and on Total Protein Pattern of Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 1997, 51, 323–332. [CrossRef]

- Schafleitner, R.; Wilhelm, E. CHESTNUT BLIGHT: MONITORING THE HOST RESPONSE WITH HETEROLOGOUS CDNA PROBES. Acta Hortic 1999, 494, 481–488. [CrossRef]

- Vannini, A.; Caruso, C.; Leonardi, L.; Rugini, E.; Chiarot, E.; Caporale, C.; Buonocore, V. Antifungal Properties of Chitinases from Castanea sativa against Hypovirulent and Virulent Strains of the Chestnut Blight Fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 1999, 55, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Allona, I.; Collada, C.; Casado, R.; Paz-Ares, J.; Aragoncillo, C. Bacterial Expression of an Active Class Ib Chitinase from Castanea sativa Cotyledons. Plant Mol Biol 1996, 32, 1171–1176. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; San José, M.C.; Vieitez, A.M.; Allona, I.; Aragoncillo, C.; Ballester, A. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of European Chestnut Somatic Embryos with a Castanea sativa (Mill.) Endochitinase Gene. New For (Dordr) 2016, 47, 669–684. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Rajendran, S.R.C.K.; Gaur, M.; Sajeesh, P.K.; Kumar, A. Plant Defense Signaling and Responses Against Necrotrophic Fungal Pathogens. J Plant Growth Regul 2016, 35, 1159–1174. [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Staton, M.; Cheng, C.-H.; Park, J.; Yassin, N.B.M.; Ficklin, S.; Yeh, C.-C.; Hebard, F.; Baier, K.; Powell, W.; et al. Chestnut Resistance to the Blight Disease: Insights from Transcriptome Analysis. BMC Plant Biol 2012, 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Han, X.; Feng, D.; Yuan, D.; Huang, L.J. Signaling Crosstalk between Salicylic Acid and Ethylene/Jasmonate in Plant Defense: Do We Understand What They Are Whispering? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, Vol. 20, Page 671 2019, 20, 671. [CrossRef]

- Staton, M.; Addo-Quaye, C.; Cannon, N.; Yu, J.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Huff, M.; Islam-Faridi, N.; Fan, S.; Georgi, L.L.; Nelson, C.D.; et al. “A Reference Genome Assembly and Adaptive Trait Analysis of Castanea mollissima ‘Vanuxem,’ a Source of Resistance to Chestnut Blight in Restoration Breeding.” Tree Genet Genomes 2020, 16, 57. [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Aslam, M.M.; Ditta, A.; Iqbal, R.; Mustafa, A.E.Z.M.A.; Elshikh, M.S.; Uzair, M.; Aghayeva, S.; Qasim, M.; Ercisli, S.; et al. Evaluation of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of the Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima) by Using NR-SSR Markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2025, 72, 2445–2457. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Huang, W.; Lan, Y.; Cao, Q.; Su, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, G. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Wild Chinese Chestnut (Castanea Mollissima). Conserv Genet Resour 2018, 10, 291–294. [CrossRef]

- Kubisiak, T.L.; Hebard, F. V.; Nelson, C.D.; Zhang, J.; Bernatzky, R.; Huang, H.; Anagnostakis, S.L.; Doudrick, R.L. Molecular Mapping of Resistance to Blight in an Interspecific Cross in the Genus Castanea. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 751–759. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Georgi, L.L.; Hebard, F. V.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Yu, J.; Sisco, P.H.; Fitzsimmons, S.F.; Staton, M.E.; Abbott, A.G.; Nelson, C.D. Mapping QTLs for Blight Resistance and Morpho-Phenological Traits in Inter-Species Hybrid Families of Chestnut (Castanea Spp.). Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1365951. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.W.; Malukiewicz, J.; Sreedasyam, A.; Jenkins, J.W.; Zhang, Q.; Lakoba, V.; Fitzsimmons, S.F.; Van Clief, J.; Collins, K.; Hoy, S.; et al. Improving American Chestnut Resistance to Two Invasive Pathogens through Genome-Enabled Breeding. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.01.30.635736.

- Powell, W.A.; Newhouse, A.E.; Coffey, V. Developing Blight-Tolerant American Chestnut Trees. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11, a034587. [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, A.; Breda, K.; McGuigan, L.; Coffey, V.; Oakes, A.; Matthews, D.; Drake, J.; Pilkey, H.; Satchwell, S.; Carlson, E.; et al. Petition for Determination of Nonregulated Status for Blight-Tolerant Darling 54 American Chestnut (Castanea Dentata) Available online: https://www.regulations.gov/document/APHIS-2020-0030-17585 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Zhang, B.; Oakes, A.D.; Newhouse, A.E.; Baier, K.M.; Maynard, C.A.; Powell, W.A. A Threshold Level of Oxalate Oxidase Transgene Expression Reduces Cryphonectria parasitica-Induced Necrosis in a Transgenic American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Leaf Bioassay. Transgenic Res 2013, 22, 973–982. [CrossRef]

- USDA-APHIS. Draft Environmental Impact Statement: The State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Petition (19-309-01p) for Determination of Nonregulated Status for Blight-Tolerant Darling 54 American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Available online: https://www.regulations.gov/document/APHIS-2020-0030-17583 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Barakat, A.; Diloreto, D.S.; Zhang, Y.; Smith, C.; Baier, K.; Powell, W.A.; Wheeler, N.; Sederoff, R. Comparison of the Transcriptomes of American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) and Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima) in Response to the Chestnut Blight Infection. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ghozlan, M.H.; EL-Argawy, E.; Tokgöz, S.; Lakshman, D.K.; Mitra, A.; Ghozlan, M.H.; EL-Argawy, E.; Tokgöz, S.; Lakshman, D.K.; Mitra, A. Plant Defense against Necrotrophic Pathogens. Am J Plant Sci 2020, 11, 2122–2138. [CrossRef]

- Künstler, A.; Bacsó, R.; Gullner, G.; Hafez, Y.M.; Király, L. Staying Alive – Is Cell Death Dispensable for Plant Disease Resistance during the Hypersensitive Response? Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 2016, 93, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Almagro, L.; Gómez Ros, L. V.; Belchi-Navarro, S.; Bru, R.; Ros Barceló, A.; Pedreño, M.A. Class III Peroxidases in Plant Defence Reactions. J Exp Bot 2009, 60, 377–390. [CrossRef]

- Passardi, F.; Cosio, C.; Penel, C.; Dunand, C. Peroxidases Have More Functions than a Swiss Army Knife. Plant Cell Rep 2005, 24, 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Havir, E.A.; Anagnostakis, S.L. Seasonal Variation of Peroxidase Activity in Chestnut Trees. Phytochemistry 1998, 48, 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Dane, F.; Wang, Z.; Goertzen, L. Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Castanea Pumila Var. Pumila, the Allegheny Chinkapin. Tree Genet Genomes 2015, 11, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhao, S.; Hao, Y.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.; Xing, Y.; Qin, L. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Key Genes Involved in the Resistance to Cryphonectria parasitica during Early Disease Development in Chinese Chestnut. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Campo, M.; Bellumori, M.; Cecchi, L.; Vignolini, P.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N. Tannins from Different Parts of the Chestnut Trunk (Castanea sativa Mill.): A Green and Effective Extraction Method and Their Profiling by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector-Mass Spectrometry. ACS Food Science & Technology 2023, 3, 1903–1912. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, S.L. Chestnut Bark Tannin Assays and Growth of Chestnut Blight Fungus on Extracted Tannin. J Chem Ecol 1992, 18, 1365–1373. [CrossRef]

- Elkins, J.R.; Pate, W.; Hicks, S. Evidence for a Role of Hamamelitannin in the Pathogenicity of Endothia parasitica. Phytopathology 1979, 69, 1027–1028.

- Hebard, F. V.; Griffin, G.J.; Elkins, J.R. Developmental Histopathology of Cankers Incited by Hypovirulent and Virulent Isolates of Endothia Parasitica on Susceptible and Resistant Chestnut Trees. Phytopathology 1984, 74, 140. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.R.; Rieske, L.K. Differential Responses in American (Castanea dentata Marshall) and Chinese (C. mollissima Blume) Chestnut (Falales: Fagaceae) to Foliar Application of Jasmonic Acid. Chemoecology 2008, 18, 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Shain, L. Activity of Polygalacturonase Produced by Cryphonectria parasitica in Chestnut Bark and Its Inhibition by Extracts from American and Chinese Chestnut. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 1995, 46, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Ferracini, C.; Ferrari, E.; Pontini, M.; Saladini, M.A.; Alma, A. Effectiveness of Torymus sinensis: A Successful Long-Term Control of the Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp in Italy. J Pest Sci (2004) 2019, 92, 353–359. [CrossRef]

- Quacchia, A.; Moriya, S.; Bosio, G.; Scapin, I.; Alma, A. Rearing, Release and Settlement Prospect in Italy of Torymus sinensis, the Biological Control Agent of the Chestnut Gall Wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus. BioControl 2008, 53, 829–839. [CrossRef]

- Sartor, C.; Botta, R.; Mellano, M.G.; Beccaro, G.L.; Bounous, G.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Quacchia, A.; Alma, A. Evaluation of Susceptibility to Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Castanea sativa Miller and in Hybrid Cultivars. Acta Hortic 2009, 815, 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Dini, F.; Sartor, C.; Botta, R. Detection of a Hypersensitive Reaction in the Chestnut Hybrid ‘Bouche de Bétizac’ Infested by Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2012, 60, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Botta, R.; Sartor, C.; Marinoni, D.T.; Quacchia, A.; Alma, A. Differential Gene Expression in Chestnut Buds Following Infestation by Gall-Wasp (Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu, Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Acta Hortic 2009, 844, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Acquadro, A.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Sartor, C.; Dini, F.; Macchio, M.; Botta, R. Transcriptome Characterization and Expression Profiling in Chestnut Cultivars Resistant or Susceptible to the Gall Wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2020, 295, 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, F.; Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M.; Nieuwenhuizen, N.J. Transcriptomics and Antioxidant Analysis of Two Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima BL.) Varieties Provides New Insights Into the Mechanisms of Resistance to Gall Wasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus Infestation. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 874434. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ren, Y.; Su, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, D. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Oriental Chestnut Gall Wasp (Dryocosmus kuriphilus). Sci Data 2024, 11, 963. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Fontana, P.; Marchesini, A.; Torre, S.; Moser, M.; Piazza, S.; Alessandri, S.; Pavese, V.; Pollegioni, P.; Vernesi, C.; et al. The de Novo, Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Sweet Chestnut (Castanea Sativa Mill.) Cv. Marrone Di Chiusa Pesio. BMC Genom Data 2024, 25, 64. [CrossRef]

- Uncu, A.O.; Cetin, D.; Srivastava, V.; Uncu, A.T.; Akbudak, M.A. A Genome Sequence Resource for the European Chestnut (Castanea Sativa Mill.) and the Development of Genic Microsatellite Markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2025, 72, 3621–3636. [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, K.; Nishio, S.; Terakami, S.; Botta, R.; Marinoni, D.T.; Isobe, S. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Japanese Chestnut (Castanea crenata Sieb. et Zucc.) Reveals Conserved Chromosomal Segments in Woody Rosids. DNA Research 2021, 28. [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, A.M.; Westbrook, J.W.; Zhang, Q.; Holliday, J.A. A Genome-Guided Strategy for Climate Resilience in American Chestnut Restoration Populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2403505121. [CrossRef]

- Pavese, V.; Moglia, A.; Abbà, S.; Milani, A.M.; Marinoni, D.T.; Corredoira, E.; Martinez, M.T.; Botta, R. First Report on Genome Editing via Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) in Castanea sativa Mill. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, A.M.; Vieitez, M.L.; Vieitez, E. Chestnut Spp. . In Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry, Trees I; Bajaj, Y.P.S., Ed.; Springer Verlag: Berlin, 1986; pp. 393–414.

- Ballester, A.; Sánchez, M.C.; Vieitez, A.M. Etiolation as a Pretreatment for in Vitro Establishment and Multiplication of Mature Chestnut. Physiol Plant 1989, 77, 395–400. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A. Reinvigoration Treatments for the Micropropagation of Mature Chestnut Trees. Annales des Sciences Forestières 1997, 54, 359–370. [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, A.; Giannini, R. Reinvigoration of Mature Chestnut (Castanea sativa) by Repeated Graftings and Micropropagation. Tree Physiol 2000, 20, 1243–1248. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Martínez, M.; Cernadas, M.; San José, M. Application of Biotechnology in the Conservation of the Genus Castanea. Forests 2017, 8, 394. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.; Tedesco, S.; da Silva, I.V.; Santos, C.; Machado, H.; Costa, R.L. A New Clonal Propagation Protocol Develops Quality Root Systems in Chestnut. Forests 2020, 11, 826. [CrossRef]

- Merkle, S.A.; Viéitez, F.J.; Corredoira, E.; Carlson, J.E. Castanea Spp. Chestnut. In Biotechnology of fruit and nut crops; CAB International: UK, 2020; pp. 206–237.

- Pavese, V.; Ruffa, P.; Abbà, S.; Costa, R.L.; Corredoira, E.; Silvestri, C.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Botta, R. An In Vitro Protocol for Propagating Castanea Sativa Italian Cultivars. Plants 2022, 11, 3308. [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Chen, Q.; Callow, P.; Mandujano, M.; Han, X.; Cuenca, B.; Bonito, G.; Medina-Mora, C.; Fulbright, D.W.; Guyer, D.E. Efficient Micropropagation of Chestnut Hybrids (Castanea Spp.) Using Modified Woody Plant Medium and Zeatin Riboside. Hortic Plant J 2021, 7, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, A.M.; Sänchez, M.C.; García-Nimo, M.L.; Ballester, A. Protocol for Micropropagation of Castanea sativa. In Protocols for Micropropagation of Woody Trees and Fruits; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2007; pp. 299–312.

- Marino, L.A.; Ruffa, P.; Mozzanini, E.; Patono, D.L.; Sereno, A.; Pavese, V. LEDs in Plant Tissue Culture: Boosting Micropropagation of Castanea sativa Cultivars. J Plant Growth Regul 2025, 44, 6046–6060. [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, F.J.; San Jose, M.C.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Somatic Embryogenesis in Cultured Immature Zygotic Embryos in Chestnut. J Plant Physiol 1990, 136, 253–256. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, F.J.; Vieitez, A.M. Somatic Embryogenesis in Chestnut. In Somatic Embryogenesis; Mujib, S., Samaj, J., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 177–199.

- Sauer, U.; Wilhelm, E. Somatic Embryogenesis from Ovaries, Developing Ovules and Immature Zygotic Embryos, and Improved Embryo Development of Castanea Sativa. Biol Plant 2005, 49, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, M.; Dumanoğlu, H. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration from Immature Cotyledons of European Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant 2014, 50, 58–68. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, M.; Dumanoğlu, H. In Vitro Propagation Potential via Somatic Embryogenesis of the Two Maturing Early Cultivars of European Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). Am J Plant Sci 2016, 07, 1001–1012. [CrossRef]

- Vieitez, F.J. Somatic Embryogenesis in Chestnut. 1995, 375–407. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Proliferation , Maturation and Germination of Castanea sativa Mill Somatic Embryos Originated from Leaf Explants. Ann Bot 2003, 92, 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Vieitez, A.M.; San José, M.C.; Vieitez, F.J.; Ballester, A. Advances in Somatic Embryogenesis and Genetic Transformation of European Chestnut: Development of Transgenic Resistance to Ink and Blight Disease. In Vegetative Propagation of Forest Trees; Park, Y.S., Bonga, J.M., Moon, H.-K., Eds.; National Institute of Forest Science (NIFoS): Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 279–301.

- Vieitez, F.J. Mass Balance of a Long-Term Somatic Embryo Cultures of Chestnut. In Proceedings of the Application of Biotechnology to Forest Genetics, BIOFOR-99; Espinel, S., Ritter, E., Eds.; Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 1999; pp. 199–211.

- Corredoira, E.; Valladares, S.; Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Improved Germination of Somatic Embryos and Plant Recovery of European Chestnut Improved Germination of Somatic Embryos and Plant Recovery of European Chestnut. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant 2008. [CrossRef]

- Seabra, R.C.; Pais, M.S. Genetic Transformation of European Chestnut. Plant Cell Rep 1998, 17, 177–182.

- Corredoira, E.; Montenegro, D.; San-José, M.C.; Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of European Chestnut Embryogenic Cultures. Plant Cell Rep 2004, 23, 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; San-José, M.C.; Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Improving Genetic Transformation of European Chestnut and Cryopreservation of Transgenic Lines. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 2007, 91, 281–288. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; San-josé, M.C.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Genetic Transformation of Castanea sativa Mill. by Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Acta Hortic 2005, 693, 387–393. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, E.C. Structural and Developmental Patterns in Somatic Embryogenesis. In In Vitro Embryogenesis in PlantsCurrent Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture; Thorpe, T.A., Ed.; Springer, Dordrecht, 1995; Vol. 20, pp. 205–247 ISBN 978-94-011-0485-2.

- Garcia-Casado, G.; Collada, C.; Allona, I.; Soto, A.; Casado, R.; Rodriguez-Cerezo, E.; Gomez, L.; Aragoncillo, C. Characterization of an Apoplastic Basic Thaumatin-like Protein from Recalcitrant Chestnut Seeds. Physiol Plant 2000, 110, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Valladares, S.; Allona, I.; Aragoncillo, C.; Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Genetic Transformation of European Chestnut Somatic Embryos with a Native Thaumatin-like Protein (CsTL1) Gene Isolated from Castanea sativa Seeds. Tree Physiol 2012, 00, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Serrazina, S.; Martínez, M.T.; Valladares, S.; Del Castillo-González, L.; Francisco, M.; Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Piñas, E.; Piñeiro, P.; Malhó, R.; Costa, R.L.; et al. Overexpression of Ginkbilobin-2 Homologous Domain Gene to Enhance the Tolerance to Phytophthora cinnamomi in Plants of European Chestnut. BMC Genomics 2025. (in press).

- Colavolpe, M.B.; Vaz Dias, F.; Serrazina, S.; Malhó, R.; Lourenço Costa, R. Castanea crenata Ginkbilobin-2-like Recombinant Protein Reveals Potential as an Antimicrobial against Phytophthora cinnamomi, the Causal Agent of Ink Disease in European Chestnut. Forests 2023, Vol. 14, Page 785 2023, 14, 785. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; Valladares, S.; Vieitez, A.M.; Ballester, A. Chestnut, European (Castanea sativa). In Agrobacterium Protocols; Wang, K., Ed.; 2015; pp. 163–176.

- Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C. CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing and Precision Plant Breeding in Agriculture. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2019, 70, 667–697. [CrossRef]

- Walawage, S.L.; Zaini, P.A.; Mubarik, M.S.; Martinelli, F.; Balan, B.; Caruso, T.; Leslie, C.A.; Dandekar, A.M. Deploying Genome Editing Tools for Dissecting the Biology of Nut Trees. Front Sustain Food Syst 2019, 3, 491199. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wu, J.; VanDusen, N.J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Homology-Directed Repair for Precise Gene Editing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102344. [CrossRef]

- Bewg, W.P.; Ci, D.; Tsai, C.-J. Genome Editing in Trees: From Multiple Repair Pathways to Long-Term Stability. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 412688. [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.W.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S. Il; Corvalán, C.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-G.; Kim, S.-T.; Choe, S.; Kim, J.-S. DNA-Free Genome Editing in Plants with Preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoproteins. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 1162–1164. [CrossRef]

- Santillán Martínez, M.I.; Bracuto, V.; Koseoglou, E.; Appiano, M.; Jacobsen, E.; Visser, R.G.F.; Wolters, A.-M.A.; Bai, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-Targeted Mutagenesis of the Tomato Susceptibility Gene PMR4 for Resistance against Powdery Mildew. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, 284. [CrossRef]

- Pavese, V.; Moglia, A.; Corredoira, E.; Martínez, M.T.; Torello Marinoni, D.; Botta, R. First Report of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Castanea sativa Mill. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 1752. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, D.; Martínez, M.T.; Sánchez-Romero, C.; Montalbán, I.A.; Sales, E.; Moncaleán, P.; Arrillaga, I.; Corredoira, E. Current Status of the Cryopreservation of Embryogenic Material of Woody Species. Front Plant Sci 2024, 14, 1337152. [CrossRef]

- Corredoira, E.; San-José, M.C.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Cryopreservation of Zygotic Embryo Axes and Somatic Embryos of European Chestnut. Cryo Letters 2004, 25, 33–42.

- Gaidamashvili, M.; Khurtsidze, E.; Kutchava, T.; Lambardi, M.; Benelli, C. Efficient Protocol for Improving the Development of Cryopreserved Embryonic Axes of Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) by Encapsulation–Vitrification. Plants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 231 2021, 10, 231. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Oiyama, I. Cryopreservation of Nucellar Cells of Navel Orange (Citrus sinensis Osb. Var. Brasiliensis Tanaka) by Vitrification. Plant Cell Rep 1990, 9, 30–33. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.; Sánchez, C.; Jorquera, L.; Ballester, A.; Vieitez, A.M. Cryopreservation of Chestnut by Vitrification of in Vitro-Grown Shoot Tips. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant 2005, 41, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.; Vieitez, A.M.; Fernández, M.R.; Cuenca, B.; Ballester, A. Establishment of Cryopreserved Gene Banks of European Chestnut and Cork Oak. Eur J For Res 2010, 129, 635–643. [CrossRef]

- Carneros, E.; Berenguer, E.; Pérez-Pérez, Y.; Pandey, S.; Welsch, R.; Palme, K.; Gil, C.; Martínez, A.; Testillano, P.S. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Human LRRK2 Enhance in Vitro Embryogenesis and Microcallus Formation for Plant Regeneration of Crop and Model Species. J Plant Physiol 2024, 303, 154334. [CrossRef]

| Methodology | Species / Genotypes | Results / Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Physiological and biochemical responses |

C. sativa | Reduced photosynthetic pigments; Increased APX, POD, SOD; Accumulation of proline and MDA |

[116] |

|

Biological control CHV1 hypovirus |

C. sativa | Mitigation of disease severity via hypovirulent strains | [117] |

|

Chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase expression |

C. sativa | Systemic induction; Higher activity with hypovirulent strains; Antifungal activity of Ch3 protein |

[122,123,124,125] |

|

Susceptibility gene expression profiling |

C. sativa | Upregulation of pmr4 and dmr6; Suppression of SA-mediated responses |

[107] |

|

SA accumulation studies (metabolite and transcriptome analysis) |

C. sativa C. dentata C. mollissima |

Higher SA levels with hypovirulent strains; SA-related gene expression in canker tissue |

[123,128] |

| Genomic and transcriptomic studies |

C. mollissima ‘Vanuxem’ |

Identification of resistance genes; Rapid wound response and cell wall lignification |

[130] |

|

Chloroplast genome sequencing |

Wild C. mollissima | 131 genes involved in stress responses and metabolic regulation | [132] |

| Genetic mapping and GWAS | C. dentata × C. mollissima | Resistance loci on all chromosomes; Candidate resistance and susceptibility genes identified |

[63,134,135] |

|

Transgenic OxOexpression |

C. dentata | Oxalate oxidase degrades oxalic acid from pathogen; field trials and regulatory review ongoing | [136,137] |

| Transcriptome comparison via pyrosequencing |

C. dentata vs. C. mollissima |

Differential expression of defense genes; Stronger defense response in C. mollissima |

[128,140] |

| Transcriptomic profiling | Wild C. mollissima ‘HBY-1’ |

283 DEGs in metabolism and defense pathways; Early JA pathway activation |

[147] |

|

Tannin profiling (metabolite analysis) |

C. mollissima C. dentata C. sativa |

Prevalence of hamamelitannin in C. sativa and C. dentata; Higher vescalagin and castalagin in C. mollissima - inhibition of fungal enzymes |

[151,152,153] [113](and references within) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).