Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination

2.3. Laboratory Confirmation Tests

2.4. Research Surveys

2.5. Statistical Methods

2.6. Ethical Issue

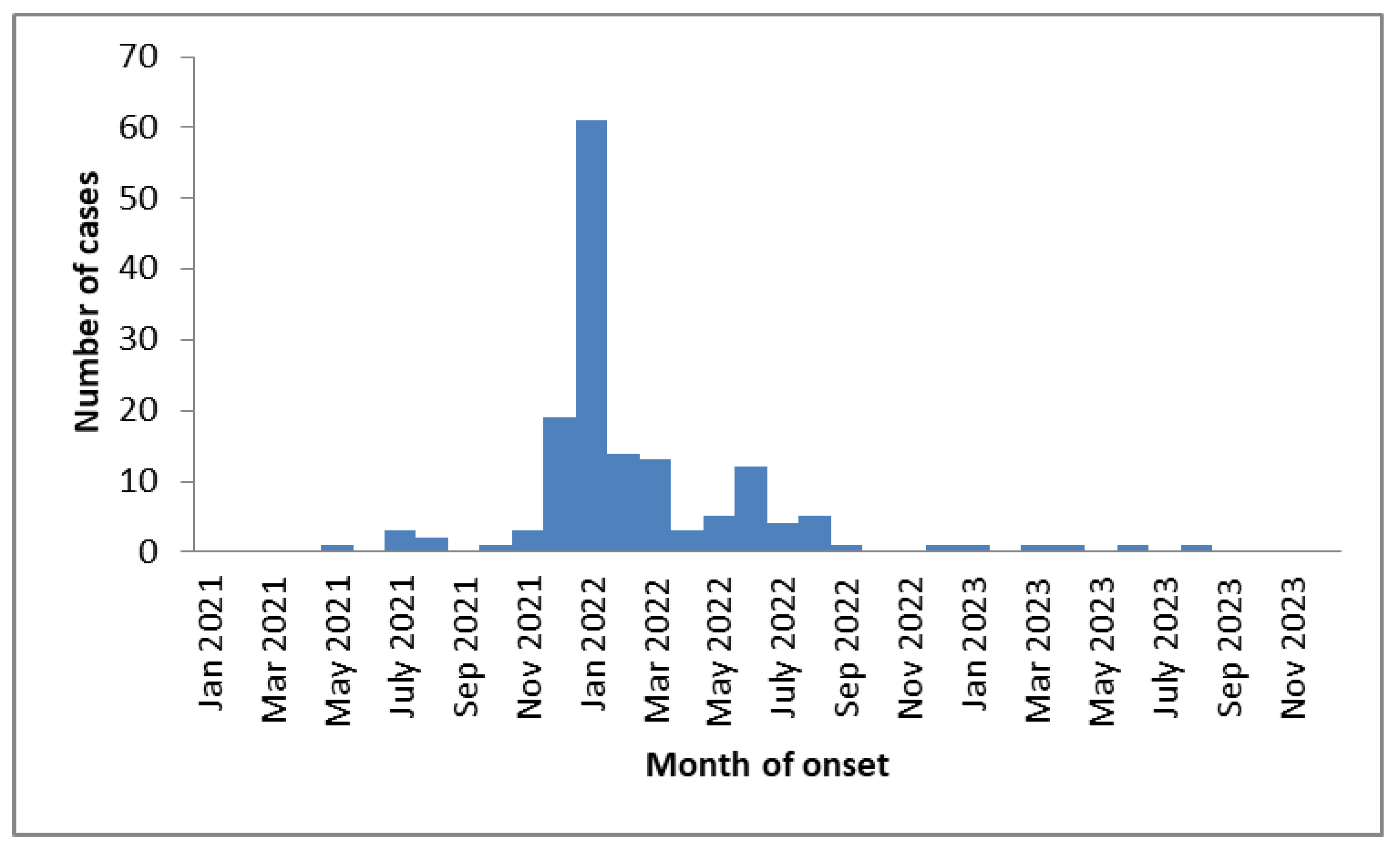

3. Results

3.1. First Approach Considering Participants Vaccinated Before SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.2. Second Approach Considering Participants Vaccinated Before a Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Excluding of Participants with Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections

| Variable | Crude RR 95%CI | Adjusted RR 95% CI | Effectiveness 95% CI | p-value |

| Female | 0.59 (0.46-0.74) | 0.61(0.49-0.78) | 39% (22-51) | 0.000 |

| Male | 0.42 (0.28-0.63) | 0.38(0.23-0.63) | 62% (37-77) | 0.000 |

| Chronic disease Yes | 0.60(0.44-0.81) | 0.48(0.32-0.73) | 52% (27-68) | 0.001 |

| No | 0.47(0.35-0.63) | 0.55(0.41-0.73) | 45% (27 -59) | 0.001 |

| Age 50 years and over | 0.46(0.31-0.69) | 0.40(0.24-0.64) | 60% (36-76) | 0.000 |

| Age under 50 years | 0.61(0.48-0.78) | 0.61(0.48-0.77) | 39% (23-52) | 0.000 |

3.3. Comparisons First and Second Approaches

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, S.J.W.; Jewell, N.P. Vaccine effectiveness studies in the field. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 650–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feikin, D.R.; Higdon, M.M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Andrews, N.; Araos, R.; Goldberg, Y.; Groome, M.J.; Huppert, A.; O'Brien, K.L.; Smith, P.G.; et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet 2022, 399, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Bao, W.J.; Zhang, H.; Fu, S.K.; Jin, H.M. The efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the Elderly: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med, 2023, Jun 2:1–9.

- Arrospide, A.; Sagardui, M.G.; Larizgoitia, I.; Iturralde, A.; Moreda, A.; Mar, J. Effectiveness of the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine in the Basque Country during the sixth wave: A nationwide cohort study. Vaccine, 2023, 41, 4274–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Badenes-Marques, G.; Gil-Fortuño, M.; Orrico-Sánchez, A.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Perez-Olaso, O.; Sala-Trull, D.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Arnedo-Pena, A. Long COVID prevalence and the impact of the third SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose: A cross-sectional analysis from the third follow-up of the Borriana Cohort, Valencia, Spain (2020-2022). Vaccines (Basel), 2023, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arashiro, T.; Arima, Y.; Muraoka, H.; Sato, A.; Oba, K.; Uehara, Y.; Arioka, H.; Yanai, H.; Kuramochi, J.; Ihara, G.; et al. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection during Delta-dominant and Omicron-dominant periods in Japan: A multicenter prospective case-control Study (factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines study). Clin Infect Dis, 2023, 76, e108-e115.

- Di Fusco, M.; Lin, J.; Vaghela, S.; Lingohr-Smith, M.; Nguyen, J.L.; Scassellati Sforzolini, T.; Judy, J.; Cane, A.; Moran, M.M. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among immunocompromised populations: a targeted literature review of real-world studies. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2022, 21, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssentongo, P.; Ssentongo, A.E.; Voleti, N.; Groff, D.; Sun, A.; Ba, D.M.; Nunez, J.; Parent, L.J.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Paules, C.I. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine effectiveness against infection, symptomatic and severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis, 2022, 22, 439.

- Wiegand, R.E.; Fireman, B.; Najdowski, M.; Tenforde, M.W.; Link-Gelles, R.; Ferdinands, J.M. Bias and negative values of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness estimates from a test-negative design without controlling for prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiberts., A.J.; Hoeve, C.E.; Kooijman, M.N.; de Melker, H.E.; Hahné, S.J.; Grobbee, D.E.; van Binnendijk, R.; den Hartog, G.; van de Wijgert, J.H.; van den Hof, S.; et al. Cohort profile: an observational population-based cohort study on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the Netherlands - the Vaccine Study COVID-19 (VASCO). BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Vidal-Utrillas, P.; Latorre-Poveda, M.; Del Rio-González, A.; Ferrando-Rubert, S.; Ferrer-Abad, G.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Aparisi-Esteve, L.; Badenes-Marques, G.; et al. "Mass gathering events and COVID-19 transmission in Borriana (Spain): A retrospective cohort study". PLoS One, 2021, 16, e0256747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Vidal-Utrillas, P.; Latorre-Poveda, M.; Del Rio-González, A.; Ferrando-Rubert, S.; Ferrer-Abad, G.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Aparisi-Esteve, L.; et al. Complications post-COVID-19 and risk factors among patients after six months of a SARS-CoV-2 infection: A population-based prospective cohort study. Epidemiologia (Basel) 2022, 3, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Orrico-Sanchéz, A.; Gómez-Lanas, L.; Sala-Trull, D.; Domènech-Leon, C.; Del Rio-González, A.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Satorres-Martinez, P.; et al. Cellular immunity of SARS-CoV-2 in the Borriana COVID-19 Cohort: A nested case-control study. Epidemiologia (Basel), 2024, 5, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodcroft, E.; CoVariants. Overview of Variants in Countries. Covariants.org. Available online: https://covariants.org/per-country?country=Spain (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- van Ewijk, C.E.; Kooijman, M.N.; Fanoy, E.; Raven, S.F.; Middeldorp, M.; Shah, A.; de Gier, B.; de Melker, H.E.; Hahné, S.J.; Knol, M.J. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Delta period, a nationwide study adjusting for chance of exposure, the Netherlands, July to December 2021. Euro Surveill 2022, 27, 2200217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, M.; Mahimainathan, L.; Araj, E.; Clark, A.E.; Markantonis, J.; Green, A.; Xu, J.; SoRelle, J.A.; Alexis, C.; Fankhauser, K.; et al. Clinical evaluation of the Abbott Alinity SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Specific Quantitative IgG and IgM Assays among infected, recovered, and vaccinated groups. J Clin Microbiol 2021, 59, e0038821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Bundschuh, C.; Wiesinger, K.; Gabriel, C.; Clodi, M.; Mueller, T.; Dieplinger, B. Comparison of the Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoassay with the EDI™ enzyme linked immunosorbent assays for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human plasma. Clin Chim Acta, 2020, 509, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; López-Diago, L.; Aleixandre-Gorriz, I.; Pérez-Olaso, Ó.; Sala-Trull, D.; Del Rio-González, A.D.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Satorres-Martinez, P.; Casanova-Suarez, J.; et al. Vitamin D Status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfections in the Borriana COVID-19 Cohort: A population-based prospective cohort study. Trop Med Infect Dis 2025, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, H.; Veneti, L.; Kristoffersen, A.B.; Danielsen, A.S.; Stecher, M.; Starrfelt, J. Estimating vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 using cause-specific sick leave as an indicator: a nationwide population-based cohort study, Norway, July 2021 - December 2022. BMC Public Health, 2024, 24, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

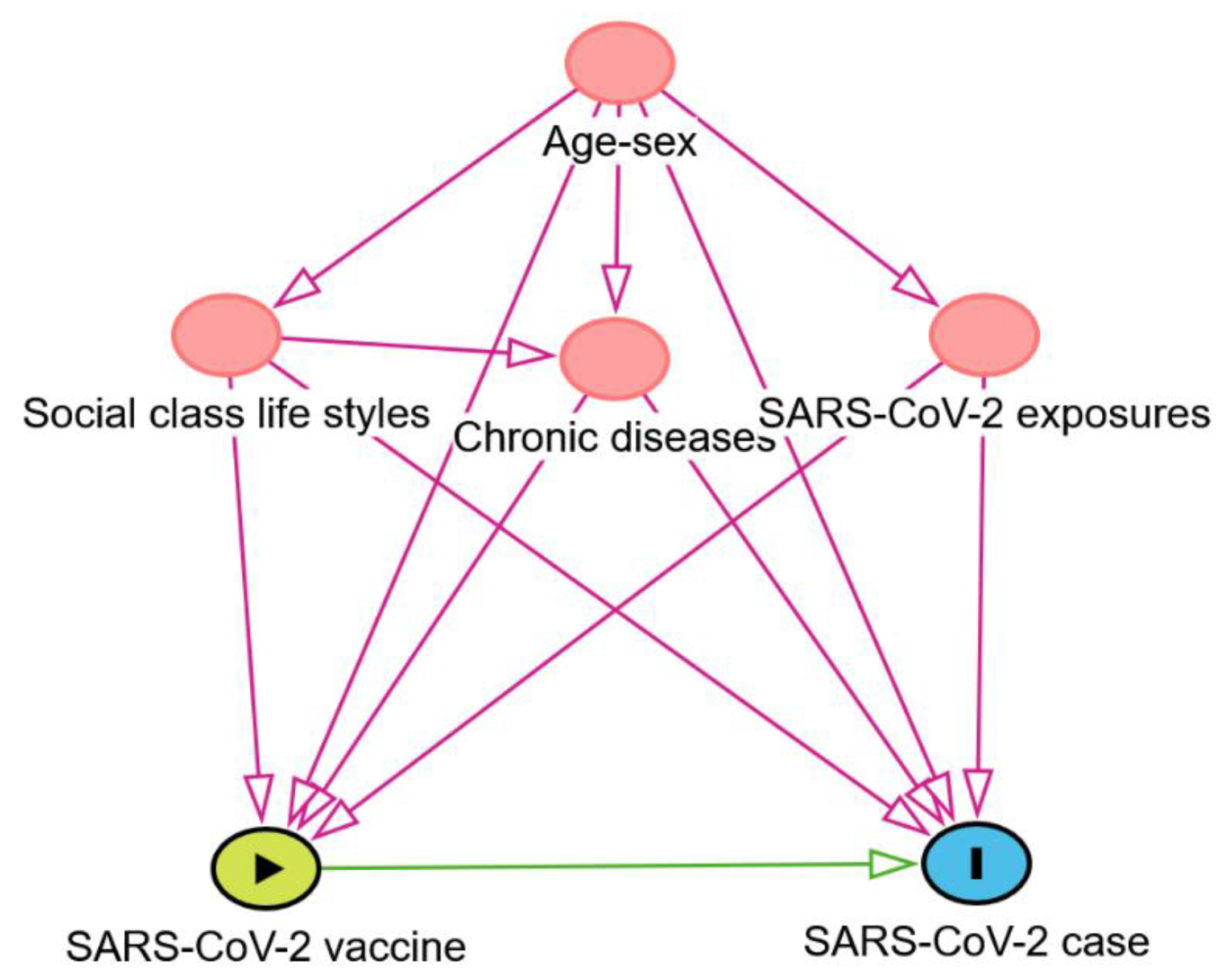

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology, 1999, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, L.; Steen, J.; Loh, W.W.; Crombez, G.; De Block, F.; Jacobs, N.; Tennant, P.W.G.; Cauwenberg, J.V.; Paepe, A.L. How to develop causal directed acyclic graphs for observational health research: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev, 2025, 19, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liskiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package 'dagitty'. Int J Epidemiol 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arashiro, T.; Arima, Y.; Muraoka, H.; Sato, A.; Oba, K.; Uehara, Y.; Arioka, H.; Yanai, H.; Yanagisawa, N.; Nagura, Y.; et al. Behavioral factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Japan. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022, 16, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Ni, P.; Chang, S.; Jin, Y.; Duan, G.; Zhang, R. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccine against Omicron-related infections in the real world: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control, 2023, 51, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.R.; Ferguson, N.M.; Donnelly, C.A.; Grassly, N.C. Measuring vaccine efficacy against infection and disease in clinical trials: Sources and magnitude of bias in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine efficacy estimates. Clin Infect Dis, 2022, 75, e764–e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Brizuela, E.; Carabali, M.; Jiang, C.; Merckx, J.; Talbot, D.; Schnitzer, ME. Potential biases in test-negative design studies of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness arising from the inclusion of asymptomatic individuals. Am J Epidemiol 2025, 194, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Dael, N.; Verweij, S.; Balafas, S.; Mubarik, S.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Pasmooij, A.M.G.; van Baarle, D.; Mol, P.G.M.; de Bock, G.H.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of European studies published up to 22 January 2024. Eur Respir Rev, 2025, 34, 240222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Rickeard, T.; Gallagher, E.; Gower, C.; Kall, M.; Groves, N.; O'Connell., A.M. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, I.; Torrella, A.; Pérez-Quílez, O.; Castillo-Zuza, A.; Martró, E.; Bordoy, A.E.; Saludes, V.; Blanco, I.; Soldevila, L.; Estrada, O.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Secondary attack rates in vaccinated and unvaccinated household contacts during replacement of Delta with Omicron variant, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis, 2022, 28, 1999–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Baz, I.; Miqueleiz, A.; Egüés, N.; Casado, I.; Burgui, C.; Echeverría, A.; Navascués, A.; Fernández-Huerta, M.; García Cenoz, M.; Trobajo-Sanmartín, C.; et al. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among social and household close contacts: A cohort study. J Infect Public Health, 2023, 16, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, R.; Romero-Severson, E.; Sanche, S.; Hengartner, N. Estimating the reproductive number R0 of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States and eight European countries and implications for vaccination. J Theor Biol, 2021, 517, 110621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singanayagam, A.; Hakki, S.; Dunning, J.; Madon, K.J.; Crone, M.A.; Koycheva, A.; Derqui-Fernandez, N.; Barnett, J.L.; Whitfield, M.G.; Varro, R.; et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2022, 22, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, H.; Park, S.; Lim, J.S.; Lim, S.Y.; Bae, S.; Lim, Y.J.; Kim, E.O.; Kim, J.; et al. Transmission and infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding kinetics in vaccinated and unvaccinated Individuals. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5, e2213606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Su, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tang, S. A comprehensive analysis of the efficacy and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 945930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.K.; Burke, P.C.; Nowacki, A.S.; Gordon, S. M Effectiveness of the 2023-2024 Formulation of the COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine. Clin Infect Dis, 2024, 79, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge, S.; Rojas-Benedicto, A.; Olmedo, C.; Mazagatos, C.; José Sierra, M.; Limia, A.; Martín-Merino, E.; Larrauri, A.; Hernán, M.A.; IBERCovid. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccine boosters against infection with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant in Spain: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2022, 22, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, N.N.Y.; So, H.C.; Cowling, B.J.; Leung, G.M.; Ip, D.K.M. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccination against asymptomatic and symptomatic infection of SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2 in Hong Kong: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2023, 23, 421-434.

- Mimura, W.; Ishiguro, C.; Maeda, M.; Murata, F.; Fukuda, H. Effectiveness of messenger RNA vaccines against infection with SARS-CoV-2 during the periods of Delta and Omicron variant predominance in Japan: the Vaccine Effectiveness, Networking, and Universal Safety (VENUS) study. Int J Infect Dis, 2022, 125, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, B.L.; Robertson, N.M.; Harrison, R.A.; Valiquette, L.; Langley, J.M.; Muller, M.P.; Cooper, C.L.; Nadarajah, J.; Powis, J.; Arnoldo, S.; et al. Risk factors for infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a cohort of Canadian healthcare workers: 2020-2023. Epidemiol Infect, 2025, 153, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arashiro, T.; Arima, Y.; Kuramochi, J.; Muraoka, H.; Sato, A.; Chubachi, K.; Oba, K.; Yanai, A.; Arioka, H.; Uehara, Y.; et al. Letter to the editor: Importance of considering high-risk behaviours in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness estimates with observational studies. Euro Surveill, 2023, 28, 2300034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.K.; Sullivan, S.G.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Peng, L.; Yang, B.; Cowling, B.J. Intensity of public health and social measures are associated with effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in test-negative study. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2025, 2025.05.08.25327221.

- Soriano López, J.; Gómez Gómez, J.H.; Ballesta-Ruiz, M.; Garcia-Pina, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, I.; Bonilla-Escobar, B.A.; Salmerón, D.; Rodríguez, B.S.; Chirlaque, M.D. COVID-19, social determinants of transmission in the home. A population-based study. Eur J Public Health, 2024, 34, 427-434.

- Novelli, S.; Opatowski, L.; Manto, C.; Rahib, D.; de Lamballerie, X.; Warszawski, J.; Meyer, L.; EpiCoV Study Group OBOT. Risk factors for community and intrahousehold transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Modeling in a nationwide French population-based cohort study, the EpiCoV Study. Am J Epidemiol, 2024, 193, 134-148.

- Judson, T.J.; Zhang, S.; Lindan, C.P.; Boothroyd, D.; Grumbach, K.; Bollyky, J.B.; Sample, H.A.; Huang, B.; Desai, M.; Gonzales, R.; et al. Association of protective behaviors with SARS-CoV-2 infection: results from a longitudinal cohort study of adults in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ann Epidemiol, 2023, 86, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, S.; Hoskins, S.; Byrne, T.; Fong, W.L.E.; Fragaszy, E.; Geismar, C.; Kovar, J.; Navaratnam, A.M.D.; Nguyen, V.; Patel, P.; et al. Differential Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Occupation: Evidence from the Virus Watch prospective cohort study in England and Wales. J Occup Med Toxicol 2023, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; Loeb, M.; Mony, P.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Mushtaha, M.; Miller, M.S.; Dias, M.; Yegorov, S.; Mamatha, V.; Telci Caklili, O.; et al. Risk factors for recognized and unrecognized SARS-CoV-2 infection: a seroepidemiologic analysis of the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Microbiol Spectr, 2024, 12, e0149223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumkötter, R.; Yilmaz, S.; Zahn, D.; Fenzl, K.; Prochaska, J.H.; Rossmann, H.; Schmidtmann, I.; Schuster, A.K.; Beutel, M.E.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Protective behavior and SARS-CoV-2 infection risk in the population - Results from the Gutenberg COVID-19 study. BMC Public Health, 2022, 22, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Loria, V.; Aparicio, A.; Porras, C.; Vanegas, J.C.; Zúñiga, M.; Morera, M.; Avila, C.; Abdelnour, A.; Gail, M.H.; et al. Behavioral factors and SARS-CoV-2 transmission heterogeneity within a household cohort in Costa Rica. Commun Med (Lond) 2023, 3, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piernas, C.; Patone, M.; Astbury, N.M.; Gao, M.; Sheikh, A.; Khunti, K.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Dixon, S.; Coupland, C.; Aveyard, P.; et al. Associations of BMI with COVID-19 vaccine uptake, vaccine effectiveness, and risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes after vaccination in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2022, 10, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Xie, Y.; Li, C. Understanding the mechanisms for COVID-19 vaccine's protection against infection and severe disease. Expert Rev Vaccines 2023, 22, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewnard, J.A.; Patel, M.M.; Jewell, N.P.; Verani, J.R.; Kobayashi, M.; Tenforde, M.W.; Dean, N.E.; Cowling, B.J.; Lopman, B.A. Theoretical framework for retrospective studies of the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Epidemiology 2021, 32, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookmeyer, R.; Morrison, D.E. Estimating vaccine effectiveness by linking population-based health registries: Some sources of bias. Am J Epidemiol 2022, 191, 1975–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agampodi, S.; Tadesse, B.T.; Sahastrabuddhe, S.; Excler, J.L.; Kim, J.H. Biases in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness studies using cohort design. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1474045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angius, F.; Puxeddu, S.; Zaimi, S.; Canton, S.; Nematollahzadeh, S.; Pibiri, A.; Delogu, I.; Alvisi, G.; Moi, M.L.; Manzin, A. SARS-CoV-2 evolution: Implications for diagnosis, treatment, vaccine effectiveness and development. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambelli, F.; de Araujo, A.C.V.S.C.; Farias, J.P.; de Andrade, K.Q.; Ferreira, L.C.S.; Minoprio, P.; Leite, L.C.C.; Oliveira, S.C. An update on anti-COVID-19 vaccines and the challenges to protect against new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Pathogens. 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Cases N=226 |

Non-cases N=75 |

Total | RR | 95 CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)±SD1 | 37.8±17.3 | 44.8±17.6 | 0.99 | (0.98-0.99) | 0.004 | |

| Age≥50 years Yes | 57 (22.2) | 41 (54.7) | 98 | 0.70 | (0.59-0.84) | 0.000 |

| No | 169 (74.8) | 34 (45.3) | 204 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 81 (35.7) | 37(49.3) | 118 | 0.87 | (0.75-0.99) | 0.049 |

| Female | 145 (64.3) | 38 (50.7) | 183 | 1.00 | ||

| Social class2 I-II | 50 (22.1) | 19(25.3) | 69 | 0.96 | (0.81-1.12) | 0.581 |

| Social class III-VI | 176 (77.9) | 56 (74.7) | 232 | 1.00 | ||

| Chronic disease Yes | 74(32.7) | 30 (40.0) | 104 | 0.92 | (0.80-1.07) | 0.271 |

| No | 152 (67.3) | 45 (60.0) | 197 | 1.00 | ||

| Obesity3,4 Yes | 30 (13.6) | 11 (14.9) | 41 | 0.97 | (0.80-1.19) | 0.798 |

| No | 190 (86.4) | 63 (85.1) | 253 | |||

| Current smoking5 | 60 (27.1) | 31(41.9) | 91 | 0.76 | (0.60-0.97) | 0.024 |

| Ex-smoking | 38 (17.2) | 13 (17.6) | 51 | 0.93 | (0.74-1.18) | 0.565 |

| Never smoking | 123 (55.0) | 30 (40.5) | 153 | 1.00 | ||

| Alcohol6 intake Yes | 40 (18.0) | 15 (21.7) | 55 | 0.96 | (0.81-1.15) | 0.677 |

| No | 182 (82.0) | 59 (78.3) | 241 | 1.00 | ||

| Physicalexercise7 Yes | 135 (60.0) | 34 (47.2) | 169 | 1.13 | (0.99-1.30) | 0.076 |

| 90 (40.0) | 38 (52.8) | 128 | 1.00 | |||

| Numbers of cohabitants at home8± SD1 | 3.3±1.0 | 2.9±1.1 | 1.08 | (1.02-1.16) | 0.011 | |

| Family COVID-19 case9 Yes | 196 (89.5) | 57 (40.5) | 253 | 1.25 | (0.96-1.62) | 0.098 |

| No | 23 (10.5) | 14 (59.5) | 37 | 1.00 | ||

| Exposure to the public at work 10 Yes | 167 (77.7) | 45 (64.3) | 212 | 1.20 | (1.00-1.43) | 0.049 |

| No | 48 (22.3) | 25 (35.7) | 73 | 1.00 | ||

| Visiting restaurants /bars11 Yes | 158 (72.5) | 42 (60.9) | 200 | 1.15 | (0.98-1.34) | 0.093 |

| No | 60 (27.5) | 27 (39.1) | 87 | 1.00 | ||

| Face mask wearing12 Yes | 69 (32.1) | 28 (40.6) | 97 | 0.91 | (0.79-1.06) | 0.218 |

| No | 146 (67.9) | 41 (59.4) | 187 | 1.00 |

| Variables |

Cases

N=226 |

No cases

N=75 |

Total | RR | 95% CI | p-value |

| N (%) | N (%) | N | ||||

| Vaccinated with at least one dose Yes | 210 (92.9) | 75 (100) | 285 | 0.74 | (0.69-0.79) | 0.000 |

| No | 16 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 16 | 1.00 | ||

| Completed vaccination | ||||||

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 200 (88.5) | 75 (100) | 275 | 0.72 | (0.68-0.78) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1 doses | 26 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 26 | 1.00 | ||

| Booster vaccination | ||||||

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 102 (45.1) | 63 (84.0) | 165 | 0.68 | (0.59-0.77) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-2 doses | 124 (55.9) | 12 (16.0) | 136 | 1.00 | ||

| Number of vaccines doses received | ||||||

| 0-1 doses | 26 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 26 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 doses | 98 (43.4) | 12 (16.0) | 110 | 0.89 | (0.83-0.95) | 0.001 |

| 3 doses | 102 (45.1) | 63 (84.0) | 165 | 0.62 | (0.55-0.70) | 0.000 |

| Type of vaccine | ||||||

| mRNA1 alone | 172 (82.0) | 56 (74.7) | 228 | 1.13 | (0.93-1.38) | 0.222 |

| mRNA1 and other vaccines | 38 (18.0) | 19 (25.3) | 57 | 1.00 |

| Variables | Adjusted RR 95% CI | Effectiveness 95% CI | p-value |

| Vaccinated with a least one dose | 0.78(0.63-0.96) | 22% (4-37) | 0.020 |

| Non-vaccinated | 1.00 | ||

| Completed vaccinated | |||

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 0.82(0.70-0.95) | 18% (5-30) | 0.011 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1 doses | 1.00 | ||

| Booster vaccination | |||

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 0.71 (0.61-0.82) | 29% (18-39) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1-2 doses | 1.00 | ||

| Number of vaccines doses received | |||

| 3 doses | 0.63 (0.51-0.78) | 37% (22-49) | 0.000 |

| 2 doses | 0.89 (0.76-1.03) | 11% (-3 - 24) | 0.149 |

| 0-1 doses | 1.00 |

| Variables | Crude RR 95%CI | Adjusted RR 95% CI | Effectiveness 95% CI | p-value |

| Female | 0.72 (0.62-0.84) | 0.74(0.63-0.87) | 26% (13-37) | 0.000 |

| Male | 0.60 (0.48-0.78) | 0.62(0.46-0.83) | 38% (17-54) | 0.001 |

| Chronic disease Yes | 0.70(0.56-0.87) | 0.60(0.44-0.81) | 40% (19-56) | 0.006 |

| No | 0.67(0.56-0.79) | 0.74(0.62-0.89) | 26% (11-38) | 0.001 |

| Age 50 years and over | 0.60(0.45-0.80) | 0.51(0.36-0.75) | 49% (25-64) | 0.000 |

| Age under 50 years | 0.77(0.67-0.89) | 0.77(0.67-0.88) | 23% (12-33) | 0.000 |

| Variables |

Cases

N=153 |

Non-cases

N=75 |

Total | RR | 95 CI | p-value |

| N (%) | N(%) | |||||

| Age (years) ± SD1 | 37.1 ± 16.8 | 44.8 ± 17.6 | 0.99 | (0.98-0.99) | 0.002 | |

| Age ≥ 50 years Yes | 36 (23.5) | 41 (54.7) | 77 | 0.60 | (0.47-0.78) | 0.000 |

| No | 117 (76.5) | 34 (45.3) | 151 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 51 (33.3) | 37(49.3) | 88 | 0.80 | (0.65-0.98) | 0.029 |

| Female | 102 (66.7) | 38 (50.7) | 140 | 1.00 | ||

| Social class2 I-II | 36 (23.5) | 19(25.3) | 55 | 0.97 | (0.78-1.20) | 0.769 |

| Social class III-VI | 117 (76.5) | 56 (74.7) | 173 | 1.00 | ||

| Chronic disease Yes | 50(32.7) | 30 (40.0) | 80 | 0.90 | (0.73-1.10) | 0.294 |

| No | 103 (67.3) | 45 (60.0) | 148 | 1.00 | ||

| Obesity3,4 Yes | 20 (13.5) | 11 (14.9) | 31 | 0.96 | (0.73-1.27) | 0.790 |

| No | 128 (86.5) | 63 (85.1) | 191 | |||

| Current smoking 5 | 39 (26.4) | 31(41.9) | 70 | 0.76 | (0.60-0.97) | 0.024 |

| Ex-smoking | 27 (18.2) | 13 (17.6) | 40 | 0.92 | (0.72-1.18) | 0.512 |

| Never smoking | 82 (55.4) | 30 (40.5) | 112 | 1.00 | ||

| Alcohol intake 6 Yes | 27 (18.1) | 15 (21.7) | 42 | 0.95 | (0.74-1.22) | 0.708 |

| No | 122 (81.9) | 59 (78.3) | 181 | 1.00 | ||

| Physical exercise7 Yes | 88 (57.9) | 34 (47.2) | 122 | 1.15 | (0.95-1.38) | 0.142 |

| No | 64 (42.1) | 38 (52.8) | 102 | 1.00 | ||

| Numbers of cohabitants at home8 ± SD1 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 1.14 | (1.04-1.25) | 0.007 | |

| Family COVID-19 case9 Yes | 137 (90.7) | 57 (40.5) | 194 | 1.41 | (0.96-2.07) | 0.077 |

| No | 14 (9.3) | 14 (59.5) | 28 | 1.00 | ||

| Exposure to the public at work 10 Yes | 117 (79.1) | 45 (64.3) | 162 | 1.30 | (1.01-1.68) | 0.041 |

| No | 31 (20.9) | 25 (35.7) | 56 | 1.00 | ||

| Visiting restaurants /bars11 Yes | 111 (74.5) | 42 (60.9) | 153 | 1.24 | (0.99-1.56) | 0.063 |

| No | 38 (25.5) | 27 (39.1) | 65 | 1.00 | ||

| Face mask wearing 12 Yes | 42 (28.6) | 28 (40.6) | 70 | 0.83 | (0.67-1.04) | 0.102 |

| No | 105 (71.4) | 41 (59.4) | 146 | 1.00 |

| Variables |

Cases

N=153 |

No cases

N=75 |

Total | RR | 95% CI | p-value |

| N (%) | N(%) | N | ||||

| Vaccinated with at least one dose Yes | 144 (94.1) | 75 (100) | 119 | 0.66 | (0.60-0.72) | 0.011 |

| No | 9 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 9 | 1.00 | ||

| Completed vaccination | ||||||

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 135 (88.2) | 75 (100) | 210 | 0.64 | (0.58-0.71) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1 doses | 18 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 18 | 1.00 | ||

| Booster vaccination | ||||||

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 54 (35.3) | 63 (84.0) | 117 | 0.51 | (0.42-0.64) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1-2 doses | 99 (64.7) | 12 (16.0) | 111 | 1.00 | ||

| Number of vaccines doses received | ||||||

| 0-1 doses | 18 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 18 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 dose s | 81 (52.9) | 12 (16.0) | 93 | 0.87 | (0.81-0.94) | 0.001 |

| 3 doses | 54 (35.3) | 63 (84.0) | 117 | 0.46 | (0.38-0.56) | 0.000 |

| Type of vaccine | ||||||

| mRNA1 alone | 119 (82.8) | 56 (74.7) | 175 | 1.20 | (0.91-1.58) | 0.205 |

| mRNA1 and other vaccines | 25 (20.8) | 19 (25.3) | 44 | 1.00 |

| Variable | Adjusted RR 95% CI | Effectiveness 95% CI | p-value |

| Vaccinated with at least one dose | 0.81(0.53-1.22) | 19% (-22 - 47) | 0.308 |

| Non-vaccinated | 1.00 | ||

| Completed vaccinated | |||

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 0.82(0.67-1.01) | 18%(-1- 33 ) | 0.066 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1 doses | 1.00 | ||

| Booster vaccination | |||

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 0.54 (0.44-0.68) | 46% (32-56) | 0.000 |

| Vaccinated with 0-1-2 doses | 1.00 | ||

| Number of vaccines doses received | |||

| 3 doses | 0.50 (0.37-0.67) | 50% (33-63) | 0.000 |

| 2 doses | 0.92 (0.75-1.12) | 8% (-12 - 25) | 0.376 |

| 0-1 doses | 1.00 |

| Measures | First approach | Second approach |

| All SARS-CoV-2 cases | Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 cases | |

| Variables | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) |

| Vaccinated with at least one dose | 0.78(0.63-0.96) | 0.81(0.53-1.22) |

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 0.82(0.70-0.95) | 0.82(0.67-1.01) |

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 0.71 (0.61-0.82) | 0.54 (0.44-0.68) |

| Number of vaccine doses | ||

| 3 doses | 0.63 (0.51-0.78) | 0.50 (0.37-0.67) |

| 2 doses | 0.89 (0.76-1.03) | 0.92 (0.75-1.12) |

| Effectiveness | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) |

| Vaccinated with at least one dose | 22% (4-37) | 19% (-22 - 47) |

| Vaccinated with 2-3 doses | 18% (5-30) | 18% (-1 -33) |

| Vaccinated with 3 doses | 29% (18-39) | 46% (32-56) |

| Number of vaccines received | ||

| 3 doses | 37% (22-49) | 50% (33-63) |

| 2 doses | 11% (-3- 24) | 8% (-12 - 25) |

| Stratification | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) |

| Female | 0.74(0.63-0.87) | 0.62(0.49-0.78) |

| Male | 0.62(0.46-0.83) | 0.38(0.23-0.63) |

| Chronic disease Yes | 0.60(0.44-0.81) | 0.48(0.32-0.72) |

| No | 0.74(0.62-0.89) | 0.55(0.42-0.74) |

| Age 50 years and above | 0.51(0.36-0.75) | 0.41(0.26-0.66) |

| Age low 50 years | 0.77(0.67-0.88) | 0.61(0.47-0.77) |

| Effectiveness | ||

| Female | 26% (13-37) | 39% (22-51) |

| Male | 38% (13-54) | 62% (37-77) |

| Chronic disease Yes | 40% (19-56) | 52% (27-68) |

| No | 26% (11-38) | 45% (27-59) |

| Age 50 years and over | 49% (25-64) | 60% (36-76) |

| Age under 50 years | 23% (12-33) | 39% (23-53) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).