1. Introduction

The development of a diverse range of antiviral therapies against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses is essential in preparing for the burden of future coronaviral pandemics and epidemics on public health[

1]. Surface proteins on viral membranes are key mediators of viral infection in host cells. Synthetic peptides derived from the fusion peptide (FP) and heptad repeat (HR) regions of measles virus and human immunodeficiency virus type-I (HIV-1) have been reported to inhibit viral replication, thus being used as antiviral peptides in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis [

2] and HIV-1 infection [

3]. Coronaviruses are similarly enveloped viruses with an exterior lipid envelope. Their major surface glycoprotein, Spike (S), contains FP and HR regions that play key roles in the fusion of viral and host membranes to transfer the viral genetic material into the host cell [

4]. Upon binding of the receptor binding domain of S to the major host receptor protein ACE2, S undergoes a conformational change involving HR multimerization that exposes FP and promotes FP insertion into the host cell membrane [

4], typically following the FP N-terminus being exposed during S activation by TMPRSS2 proteolytic cleavage between the S1 and S2 regions of S. Peptides of around forty amino acids in length derived from the HR region have been shown to inhibit SARS and SARS-CoV-2 infection in animal models [

5]. The role of FP-derived or FP-targeting peptides in inhibiting coronaviral infection has not been extensively explored. Given FP evolutionary conservation across coronaviruses, any viral entry inhibitors targeting it may be less prone to the evolution of viral resistance, and may be useful in inhibiting multiple coronaviral species.

FP has been defined as encompassing two regions: the N-terminal FP1, and the following FP2 region. The structure of FP has been characterised in a membrane bicelle as a wedge-shaped set of three alpha-helices. This structure enables interactions of its exposed hydrophobic residues with phospholipid acyl chains [

6], with a short disulphide bridge in the FP2 region contributing in part to the structure. Phosphorylation of the serine at the very start of FP has been reported [

7], but it is unclear what proportion of S proteins are phosphorylated at this site, either before or after protease cleavage upstream of FP. Addition of this negatively charged post translational modification may not directly disrupt the wedge-like FP structure, since the serine is exposed, but it could alter S and FP interactions with membrane, interacting proteins or inhibitors.

We set out to identify peptides that bind the non-phosphorylated form of FP, and that might also have the potential to disrupt SARS-CoV-2 viral entry. To identify binding peptides, we screened two phage display libraries. The NEB PhD-7mer library is a diverse library of a billion (10

9) random 7-mer peptides displayed on the surface of M13 bacteriophage. Since peptides containing D-amino acid enantiomers are more resistant to proteolytic degradation, we identified D-amino acid binders of FP using a mirror phage display approach [

8]. While retro-inverso(D)-peptides only retain an approximate functionality of forward L-peptides, with mirrored phage display there is a nicely preserved perfect fit of the selected peptides, since the screened D-FP bait has an interaction with the phage display binding L-peptides that is an exact mirror image of the L-peptide FP (natural) sequence interaction with the phage display peptides sequenced as D-amino acids [

8]. Secondly, we screened a proteomic phage display library derived from the disordered regions of human proteins [

9], since it is possible that FP may form interactions with human protein regions during membrane fusion. Peptides of interest derived from both screening strategies were then tested for their ability to inhibit viral entry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Peptide Synthesis and Characterization

Peptides were synthesised as forward L-sequences, unless otherwise indicated. The phage display biotinylated FP bait, and the peptides selected from phage display were synthesised substituting L-amino acids with D-amino acids. All the peptides were synthesized on a 0.1 mmol scale from a Rink Amide MBHA resin except for biotinylated fusion D-peptide FP where Rink Amide protide resin was used. Sequences were assembled by solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), according to the Fmoc/t-Bu strategy, with DIC/ Oxyma coupling chemistry, using a microwave-assisted Liberty Blue peptide synthesizer from CEM (CEM Microwave Technology Ltd, Dublin, Ireland). After automated peptide assembly, modifications like biotinylation and acetylation were carried out manually before cleaving the peptide from resin whereas peptide cyclization was carried out after cleaving the peptide from resin. For N-term acetylation, the Fmoc deprotected peptidyl resin was reacted with (1:1) acetic anhydride: DCM solution. The assembled peptides were released from the resin using a cleavage cocktail containing 81.5% TFA, 10% thioanisole, 5% water, 2.5% 1,2-ethane dithiol and 1% triisopropylsilane (TIS). The crude peptides were purified by reverse phase HPLC (Shimadzu Prominence LC system, Kyoto, Japan), using a C18 column (Gemini 110 Å, 5 μm, 10 × 250 mm, Phenomenex, Macclesfield, Cheshire, UK) over a gradient of water/ acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA added to each buffer. The mass of the peptides were confirmed by MALDI TOF Mass Spectrometry (Bruker autoflex maX).

The scheme for generating cyclic biotinylated FP fusion D-peptide is provided in Figure A1. The peptide was assembled by automated SPPS, using a lysine at the C terminus with e- amino protected by a Mtt group. The resin with N-terminally Fmoc protected peptide was treated with a solution of 1% TFA, 2% TIS and 97% DCM to remove the Mtt group from the lysine side chain. Next, the resin with the free lysine side chain amine was reacted twice with 10 eq. of biotin, 10 eq. HATU and 20 eq. of diisopropylethyl amine (DIEA). The Fmoc deprotection of the N terminus of the peptide was later carried out by adding 20% piperidine in DMF twice (n? min each) to the resin. The peptide was then released from the resin using a cleavage cocktail as described above. After HPLC purification, the linear peptide was dissolved at a concentration lower than 100 µg/ml in 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH = 8 with continuous stirring under air for 24 h to form the heterodetic cyclic peptide [

10].

2.2. Combinatorial NEB PhD Phage Display Screening

Streptavidin solution (Sigma S4762, 1 mg/ml) (SA) was prepared in 1x PBS. 9 mg Silica nanoparticles (SiO2 Nps 150 nm in ethanol) were washed with deionized H2O by spinning (7000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature), and the COOH coating activated to COO- by 0.2 M EDC and 50 mM NHS, and then rinsed with dH2O and resuspended in 1x PBS. 1 ml of SA was added to 9 ml of equilibrating buffer (10 mM NaOAc; pH 4.0). Then 1 ml of SiO2 Nps 150 nm (9 mg/ml) was added, and rotated at room temperature for 4 hours. The pellet of SA-conjugated nanoparticles was collected by spinning at 7000 rpm for 5 mins, and washed twice by resuspension/rinsing in 1x PBS (900 µ). Finally, the pellet of SA-conjugated-Nps beads was resuspended in 1 ml of 1x PBS. Remaining 750 μl of SA-Conjugated-Nps beads were functionalized with 1 ml of D-FP12_biotin (0.5 mg/ml) on a rotating wheel for 30 mins at room temperature. The functionalized beads were collected as a pellet by spinning at 7000 rpm for 5 mins and washed with 1x PBS twice. A final suspension of functionalized beads (1 ml 1x PBS) was stored at 40 C. Biopanning experiments were performed in sterile microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 ml). After blocking 250 μl of functionalized beads with 750 μl of blocking buffer (5 mg/ml BSA in 1x PBS), 100 μl of Ph.D.-7 library (NEB #E8100S) was added and mixed on a rotating wheel for 30 min at room temperature. Unbound phage (target negative library) was separated from the phage-bound functionalized beads by spinning. The phage-bound functionalized beads collected as a pellet were washed and eluted with Glycine elution buffer (0.2 M Glycine-HCl, pH 2.2, 1 mg/ml BSA), and then neutralised with a neutralising buffer (1 M tris-HCl, pH 9.1). The target-bound phage viruses were further amplified using E. coli (K12 2738) cells following the manufacturer’s protocol (Ph.D.-7 Phage display peptide library kit, NEB). The amplified target-bound phage viruses were screened against the target-free SA-Conjugated-Nps beads (250 μl) for target-negative screening to eliminate the peptides binding to SA and / or Nps. The target-positive phage viruses were further amplified and screened against functionalized beads for the second and third round of screening.

After the third round of biopanning, phage DNA was isolated using the QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit (cat 12123) and following the manufacturer’s protocol. The isolated phage DNA was PCR-amplified using primers Fwd (Forward: ATTCGCAATTCCTTTAGTGGTACC; reverse: CCCTCATAGTTAGCGTAACGATCT). The PCR-product was purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit and quantified using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer and gel electrophoresis. The purified 177bp PCR products sample was sent for sequencing (Illumina Novaseq sequencer, Eurofins Genomics, Germany). The result files were processed using in-house python scripts (files available as supporting information – Table of scripts and their function) to rank the peptide sequences by copy number. The base tags used for 7-mer peptide search were “TATTCTCACTCT” for forward peptide sequence and “CGAACCTCCACC” for reverse complementary peptide sequence for reverse reads. The FASTQ files obtained had the non-tagged reads discarded. Reverse reads were reverse complemented and merged with Forward reads. The merged dataset was translated to 7-mer peptides, preceded by Tyr Ser His Ser codons and followed by Gly Gly Gly Ser within the pIII coat of M13KE.

2.3. Surface Plasma Resonance.

All SPR experiments were performed on Biacore T200, using Streptavidin SA sensor chip (Cytiva), immobilisation buffer (HBS-EP, 3 mM EDTA), running buffer HBS-P (+/- 2 mM Ca2+). Biotinylated peptides were dissolved in dH2O to 10 μg/ml and injected for 60 s to reach ~1/10 of Mr RU. The injection needle was cleaned with 1 M NaCl/ 50 mM NaOH between injections. Analyte peptides were dissolved in a running buffer and injected at 1 micromolar concentration and the association phase recorded for 600 s and dissociation phase for a further 600 s. Plots of the sensorgrams were prepared using the R ggplot2 package.

2.4. Proteomic Phage Display

The selection experiment was performed in duplicate following the strategy previously described [

11]. Thirty microliters of Streptavidin Dynabeads (Invitrogen, 100099482) were taken in two different microcentrifuge tubes for spike-FP12 peptide and the control, respectively. Beads were washed with 700 µl of PBS buffer on the magnetic rack. The beads were blocked with 700 µl of PBS + 0.5 % (w/v) BSA for 1 h at 4°C. Beads for the control were washed three times with 700 µl of PT buffer (PBS + 0.05 % Tween-20). HD2 näive phage library (Ref 1) with 1010 phages in 200 µl was prepared in PBS buffer. Phage library was added to the control beads and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Beads for spike-FP12 peptide were washed with 700 µl of PT buffer after 2 h of blocking. The unbound phage solution (200 µl) from the control beads were transferred onto beads for spike-FP12 peptide. Five micrograms of spike-FP12 peptide in 100 µl was also added onto the beads along with the phage solution to allow the binding. Beads were incubated for 2 h at 4°C on the shaker. Washed the spike-FP12 beads five times with 700 µl of PT buffer. The bound phages were eluted with 100 µl of actively growing log phase E.coli. Elution was performed at 37°C, 200 RPM for 30 min. The bacteria were hyper-infected with 1011 helper phages by incubating for 45 min at 37°C, 200 RPM. Infected cells were transferred in 10 ml of 2YT medium supplemented with 30 µg/ml kanamycin, 100 µg/ml carbenicillin and 0.3 mM IPTG. Phages were amplified by incubating the cells overnight at 37 °C, 200 RPM. Next day, phages were harvested by centrifuging the tubes at 4000 RPM, 4 °C, 10 min. The supernatant was transferred into fresh high-speed tubes. Phages were precipitated by adding 2.5 ml of PEG/NaCl buffer (20 % PEG-8000 + 2.5 M NaCl) into the supernatant. The phages were incubated for 10 min on ice to precipitate. Tubes were centrifuged at 17,000 x g, 4°C for 10 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was suspended in 1 ml of PBS buffer. The phage solution was transferred into an autoclaved microcentrifuge tube and labeled as round 1 phages. Round 1 phages were used for another round of selection. The procedure was repeated for 3 rounds.

In order to identify the binding peptides, 5 µl of amplified phages from round 3 were PCR amplified. Phages were dual barcoded using barcoding strategy [

12] and the amplification was performed with Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master mix (Thermo Scientific). The size of the amplified product was confirmed on 2 % agarose gel using 100 bp marker (Thermo Scientific). The PCR product was normalized with Mag-bind Total Pure NGS (Omega Bio-tek) and eluted with 20 µl of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA. pH 7.5) buffer. Eluted DNA was run on 2 % agarose and purified using QIAquick Gel extraction Kit Qiagen kit. DNA was eluted with TE buffer and the concentration was quantified with Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Molecular probes by Life technologies). The NGS sample was sent to the NGS-NGI SciLifeLab facility (Solna) for sequencing and analyzed with Illumina MiSeq v3 run, 1 × 150 bp read setup, 20% PhiX. Demultiplexing and data analysis was performed as described previously [

11].

2.5. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Assay and Viability Assay Methods

All cell-based assays were performed using Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 cells (Cat #100978), obtained from Centre For AIDS Reagents (CFAR) at NIBSC [

13,

14]. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’ Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Cat # 61965-026) supplemented with 10% Foetal Calf Serum (FCS, Gibco, Cat #: 10500-064), and 1 mg/ml geneticin (Gibco, Cat # 10131-035). Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO

2 in a humidified incubator. Cells routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Infection experiments were performed using ancestral SARS-CoV-2 isolate with D614G substitution (Pango lineage B.177.18, GenBank accession ON350866, Passage 4) [

15]. Work was conducted in a Containment Level 3 laboratory under Biosafety Level 3 guidelines. Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 cells were seeded at 2.5x10

4 cells per well in 96-well clear, flat-bottom plates and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO

2 to reach 90-100% confluency at the time of infection. Cells were incubated with varying concentrations of test compounds or the corresponding vehicle control for 2 hrs prior to viral infection. SARS-CoV-2 was then added at an MOI of 0.01 directly to each well. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO

2 for 18hrs. Cells were infected with an MOI of 0.04 for 2 hours, before being washed twice with dPBS and incubated in DMEM-2 containing fresh peptide or control for 18h at 37°C with 5% CO

2. Cells were subsequently trypsinised (Trypsin-EDTA, Thermo Scientific, Cat #15400054) to obtain a single cell suspension and fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, F8775).

Flow cytometry staining was carried out as previously described [

15]. Fixed cells were permeabilized in Perm/Wash solution (BD, Cat #51-2091KZ) for 30 minutes at room temperature, then incubated with an anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid primary antibody (Invitrogen, Ref#: MA1-7403) and an anti-mouse IgG fluorescein secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Cat #F2761). Cells were resuspended in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, Sigma, Cat #P4417) before flow analysis (Beckman Coulter CytoFlex). Cells were gated with Forward and Side-Scatter gates to exclude debris from intact cells, with single cells identified using Area versus Height gating. Percentage SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid positive cells were detected using the FITC-channel (Blue 488nm laser, 525/40 laser). Analysis was performed using CytExpert software (version 2.4.0.28, Beckman Coulter).

For the CCK-8 cell viability assay, cells were pre-treated with peptides as described above and mock infected for 18hrs at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cell viability was measured using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Sigma, Cat #96992-3000TESTS-F) according to manufacturer’s instructions with a 2hr colour development before absorbance was measured at 450nm (SpectraMax iD3).

3. Results

3.1. Binding Kinetics Between FP and Selected S-Derived Peptides

We initially hypothesised that S-derived peptides that affect viral entry could potentially interact with FP. A number of regions of S were identified on the basis of their potential for FP interaction after S re-organises following fusion (mainly membrane embedding potential) and/or the ability of known homologous peptides from SARS-CoV to inhibit viral entry [

16]. We evaluated the synthesised SARS-CoV-2 peptide binding kinetics with cyclic-FP-Biotin attached to a streptavidin-coated Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) surface chip. The peptide sequence was based on amino acids 816-855 spanning the overlapping fusion peptide 1 and 2 regions of UNIPROT spike protein entry P0DTC2. The peptide sequence was SFIEDLLFNKVTLADAGFIKQYGDCLGDIAARDLICAQKF-GGK(biotin)-am, where GGK provides an additional linker, with the K providing an attachment site for biotin, and “-am” indicates amidation of the carboxy terminus; the two cysteines are disulphide bonded. The amino terminus is the free amino terminus that is exposed on the Fusion peptide following protease cleavage during activation, typically by the host TMPRSS2 protease. None of these candidate selected peptides (

Table 1) bound FP with high affinity, as a negligible response signal was recorded for each of the four peptides (Figure A2).

3.2. Identification and Testing of Combinatorial Phage Display Peptides

We screened a combinatorial phage display library of 7mer peptides for binding to the FP peptide. The genome sequencing of 177bp (PhD7-mer NEB) PCR products resulted in 7,143,870 sequence reads (2,143,161,000 sequenced bases). Parsing of the sequence reads using in-house python scripts yielded 15,313 unique peptide sequences out of which only 80 unique peptides had an abundance greater than 2550. The peptide sequence WSLGYTG was found to be the most enriched with a sequence count of 6,280,489. Recent work has shown that the enrichment of the peptide sequence "WSLGYTG" is target-unrelated, with its enrichment due to its propagation advantage in M13KE-based peptide library [

20]. To filter out sequences that had such an unfair propagation advantage, we filtered out matches to two sources of enriched peptides (Figure A3) that were not specific for the FP target: a naïve amplified PhD7-mer NEB library [

21]) and a screen of the same library against a target that had extensive reporting of detected sequences [

20]. The naïve library only shared the WSLGYTG artefact. A greater number of matching peptides were observed (Figure A3) among PhD7-mer peptides binding to anti-

Borrelia burgdorferi immune sera [

20], and were accordingly removed from our candidate list, as they are less likely to be target-specific. The final selection of peptide sequences for antiviral assays (

Table 2) excluded certain peptides where there were concerns about the stability or the synthetic feasibility of the peptides [

22].

3.3. Screening Versus the Human Disordered Proteomic Phage Display Library

A proteomic phage library of human disordered protein regions [

9,

11] was screened against spike-FP12 peptide, in duplicate (

Table 3). Some of the identified peptides (CFAP73, CFAP65, MAP1A) are known to be over-enriched in a target non-specific manner in screens with this library [

11], and were thus considered lower priority.

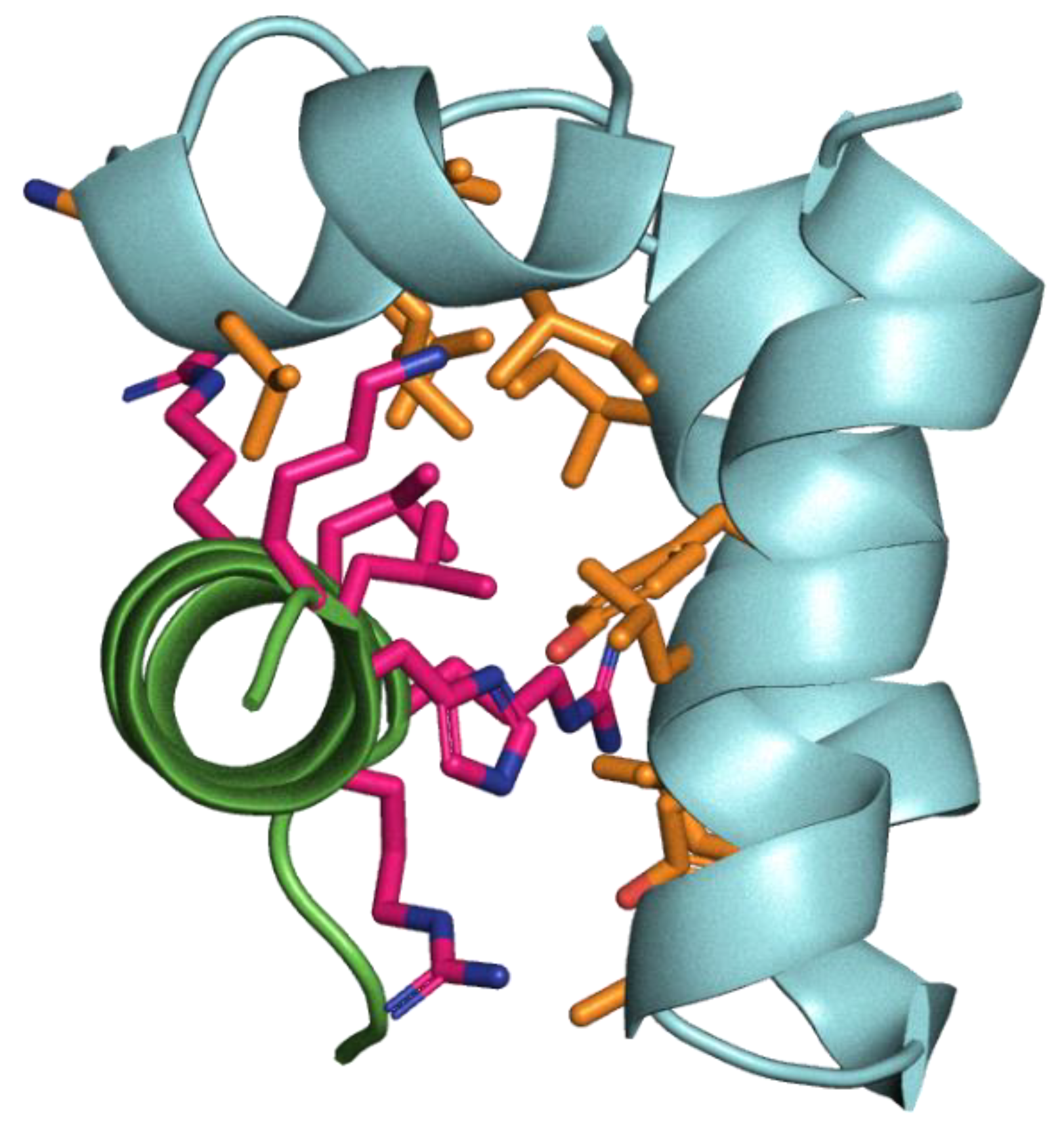

Two retrieved peptides highlighted a stretch of ovarian tumor domain-containing protein 1 (OTU deubiquitinase 1, OTUD1). These overlapping peptides shared the sequence NFRLSEHRQALA. We then investigated structural predictions of OTUD1 peptide binding modes to FP, in the context of predictions of other peptides of interest.

We predicted the structural complex of the OTUD1 region spanned by both peptides to FP, using the Alphafold3 [

23] server, and compared it to predicted structures for candidate virally-derived peptides of interest. Alphafold3 drew on the template library (up to the cutoff of 30/09/2021) that included the wedge-shaped triple helix conformation from an NMR model of FP in membrane bicelles (PDB entry 7MY8; [

6]). Given the small peptide sizes, the low likelihood of an extensive long-range coevolutionary signal between the conserved coronaviral FP and mammalian OTUD1, and the absence of any explicit modelling of the membrane environment, this is a challenging prediction. While the binding of OTUD1 was suggestively more reliable compared to that of FP with other candidate peptides (Figure A7), the iPTM interaction score of Alphafold3 did not indicate high confidence, and various potential FP binding modes are seen for the predictions for different candidate peptides. Nevertheless, the suggested binding mode of OTUD1 to FP did involve a three helix approximately wedge-like FP structure, in which the FP residues that interacted with OTUD1 were predominantly hydrophobic, including three of the phospholipid acyl binding residues identified in the bicelle structure, while 5 of the 7 residues of the helical OTUD1 peptide at the interaction surface were positively charged (

Figure 1).

Phage display of peptide regions of proteins is also possible for viral as well as host proteins, and a preliminary screen of FP versus a pan-coronaviral phage display library of regions of coronaviral proteins was carried out following the methods previously outlined [

24], which only identified a single peptide, despite a large amount of sequencing data obtained. This 39mer LSTLSVDFNGVLHKAYIDVLRNSFGKDLNANMSLAECKR peptide was derived from the nsp3 (protease-encoding) protein of coronavirus 229E comprising the last four residues of the loop between Y2 and Y3 regions, and the first 35 residues of the Y3 region. Y3 plays a role in double membrane vesicle formation [

25], but the lack of binding to homologous regions of other coronaviruses in the library placed the finding in doubt.

3.4. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Toxicity

We assessed the toxicity and efficacy of the ten selected 7-mer D peptides in Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 cells. We first evaluated their cytotoxicity using a CCK8 viability assay. Cells were treated for 18 hours with peptide concentrations ranging from 1-50 μM. No significant toxicity was observed with viability remaining between 70% and 100% across all tested conditions (Figure A4).

We next examined the antiviral capacity of the combinatorial peptides against SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 were pre-incubated with the peptides (1-50 μM) for 2 hours prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2. After 18 hours infection in the presence of the peptides, we observed a moderate reduction in the number of infected cells in the peptide-treated wells compared to the vehicle controls with 9/10 peptides with the exception of ETSTMYP. However, no dose-response was observed and the maximum inhibition remained modest, achieving less than 50% reduction in infection (Figure A5).

Given that the OTUD1 peptide naturally occurs intracellularly, we assessed the antiviral effects of the OTUD1-derived peptide modified at the N-terminus with a cell penetrating octa-arginine sequence. The sequence was then RRRRRRRRGPDRNFRLSEHRQALA-am, where “am” indicates amidation of the carboxy terminus. There was no evidence for any marked impact of this peptide on the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection of Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 cells (Figure A6).

4. Discussion

Our interest in targeting the fusion peptide (FP) of SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) arose from its evolutionary sequence conservation relative to many other regions of the S protein, and its key role in viral entry by membrane fusion selection. Its choice as a target of interest was also guided by the success story of Enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) - a 36 residue long biomimetic peptide modified from the fusion domain of HIV-type 1 virus that binds to the HR1 of the HIV-type 1 glycoprotein. The HR domain of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein undergoes a conformational shift from three helical bundles of HR1 and HR2 to a six helical bundle during viral-host membrane fusion [

26]. eptides derived from HR2 of SARS-CoV Spike have been reported to inhibit SARS-CoV infection [

27].

HR domain peptides targeting SARS-CoV-2 [

5,

28] to inhibit membrane fusion remains a useful strategy to explore further in the development of anti-coronaviral peptides, although the size of the currently effective peptides such as the pegylated cholesterol 46mer HR1-derived peptide pan-coronaviral inhibitor in phase II clinical trials [

5] may reduce their chance of progressing to widespread clinical use.

The approach of mirror-image phage display screening using L-peptide PhD7-mer library against a D-peptide target was applied to overcome one of the major limitations of L-peptide ligands’ proteolytic degradation by naturally occurring enzymes. As the D-amino acid composed target (dFP) is the exact mirror image of L-amino acid FP, the ten lead peptides selected for in vitro screenings were synthesised using D-amino acids to prevent proteolytic degradation in the cellular environment during in vitro screens. The viability assay of Vero-E6/TMPRSS2 cells confirmed that all ten D-peptides were non-toxic to mammalian cells, but had no anti-viral effects.

The strategies employed here to identify peptides that bind FP suggested peptides of potential interest, but tests of the best binding candidates identified did not identify any that had an inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection. While naturally generated antibodies can bind the FP region coronaviruses with high affinity [

29], it may be that FP of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein might not be feasible to target with short peptidyl anti-coronavirus therapies.

One of the candidate peptides identified is derived from a disordered region of the OTUD1 protein. OTUD1 is a de-ubiquitinase (DUB). At least 24 DUBs including OTUD1 negatively regulate virally induced antiviral IFN-I production, while another 10 DUBs positively regulate antiviral responses [

30]. Antibodies that cross-react among diverse coronaviruses are known to target the N-terminus of the highly conserved fusion peptide of SARS-CoV-2 [

29]. We considered the possibility that a peptide binding a section of SARS-CoV-2 S protein might share similarities with coronaviral antibodies. For the three antibodies of known structure (PDB entries 8D36, 8D6Z and 8DAO) binding to a region overlapping the FP [

29], there is no obvious primary sequence similarity of their variable FP binding regions to the OTUD1 peptide.

OTUD1 acts by de-ubiquitinating interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) at lysine 63 to prevent nuclear localisation and thus inhibit the effects of IRF3 on transcription [

31]. IRF3 plays a key role in mediating host responses to foreign viral material [

32], and can be inhibited by a coronaviral protease [

33]. Induction of OTUD1 by viruses also regulates mitochondrial antiviral signal (MAVS) protein by indirectly (via Smurf1) leading to the removal of the Lysine 48 ubiquitination of MAVS [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. OTUD1 also serves to de-ubiquitinate and stabilise Tyk2 thus stabilising INF-I responses [

39]. Tyk2 is known to be down-regulated by SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein 1 (NSP1) [

40], and another DUB that negatively regulates antiviral responses, USP13, is known to be hijacked by SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein 13 (NSP13) [

41]. Any possible role of OTUD1 could well be complex over the course of COVID infection, since it is one of 21 down-regulated signature genes associated with COVID induction of a long term inflammatory T cell and NK cell states [

42]. Given the challenges of developing small molecular inhibitors with specificity for particular DUBs, ubiquitin variant inhibitor selection by phage display [

43] has been applied to OTUD1 to develop nanomolar ubiquitin variant inhibitors [

44].

The other candidate peptides suggested by the proteomic phage display of human protein disordered regions may conceivably have some relationship to coronaviral infection. Two were derived from proteins associated with ciliated cells. Coronaviral infection can cause the withdrawal of the cilium into the cell body of nasopharyngeal cells, or other structural defects, which may contribute to rhinorrhaea [

45,

46]. Of the two ciliary cell associated proteins, CFAP73 (ciliary and flagellar associated protein 73) is not itself known to be located within the cilium, but is clearly expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of bronchial and nasopharyngeal ciliated epitheliar cells [

47], with virions accumulating at the base of cilia [

48]. While DBP (vitamin D binding protein) polymorphisms show some association with SARS-CoV-2 infection [

49,

50], it is primarily a liver enzyme, and its effects on viral function are far more likely to be via its impact on vitamin D levels, rather than being mediated through direct FP-DBP protein interaction.

While our experiments were negative, the fusion peptide remains an attractive target for pan-coronavirus therapeutics, given its high conservation. A three helix wedge shape conformation of FP has been observed on NMR analysis within membrane bicelles [

6]. This conformation serves to expose hydrophobic residues on the surface where they can form interactions with the hydrophobic membrane components (Phe817, Leu821, Phe823 of helix 1, Phe833 and Tyr837 of helix 2, and Leu828 from the loop between them). While Alphafold3 structural predictions of FP-peptide interactions had low confidence, they may provide some insights into the design of FP binding peptides. The model of OTUD1 peptide bound to FP had three helices roughly corresponding to those of the bicelle model, and another peptide identified in the proteomic phage display screen from human protein MBTPS1 had a similar periodic distribution of positive charges. The OTUD1 facing residues of FP included half of the hydrophobic residue side chains that interact with phospholipid acyl tails in the bicelle model : Leu821 of helix 1, Y837 of helix 2, and L828 from the loop region. This ability of FP to bind helices that present a strongly positively charged helical surface may help guide the future design of peptide inhibitors of FP. The membrane perturbing effect of SARS-CoV-2 FP appears to be strongly calcium dependent [

51], suggesting that positive charge may stabilise the conformation in some way. It is possible that future FP inhibitory peptides could act by outcompeting calcium binding in order to exert strong effects

in vivo.

5. Conclusions

Combinatorial 7mer phage display and proteomic phage display of peptides from human proteins identified potential candidate peptides binding FP, including a peptide derived from OTUD1. However, none of these peptides had a marked impact on the in vitro infection of mammalian cells by SARS-CoV-2. The modelled structural binding mode of the OTUD1 peptide suggested a strongly positively charged helical surface binding the hydrophobic surface of FP. This may give insights into the future design of peptides or other compounds targeting FP as pan-coronavirus inhibitors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DCS, MD, VG, NR, AP; methodology, AP, YI, NR, MA, VG, MD, DCS, DO’C, PM; software, AP; validation, VG, MA, NF, SO’R; formal analysis, AP; investigation, AP, YI, NR, DO’C, MA, NF, SO’R, PM, DCS; resources, DO’C, PM, MD; data curation, AP; writing—original draft preparation, AP, DCS; writing—review and editing, AP, NR, MA, NR, PM, NF, VG, SO’R, MD, DO’C, DCS; visualization, DCS, AP, MA; supervision, DCS, VG, MD, YI; project administration, DCS; funding acquisition, DCS, MD, VG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science Foundation Ireland (Research Ireland) grant numbers 20/COV/8470, 16/RI/3737 (peptide synthesis equipment) and 18/RI/5702 (mass spectrometry equipment)'

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The peptide sequences identified in the phage display experiment are submitted to the Xenodo repository…

Acknowledgments

We thank Ylva Ivarsson for supporting the human proteome phage display panning and sequencing in her lab by PM. We thank Julie Overbaugh and Caitlin Stoddard for their generous help in providing us with the pancoronavirus phage display library. We thank Jimmy Muldoon School of Chemistry, UCD, for MALDI-TOF MS analyses of peptides.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FP |

Fusion Peptide |

| SPR |

Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| -am |

amidation |

| ac- |

acetylation |

| NMR |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PDB |

Protein Data Base |

| S |

Spike protein |

| nsp3 |

Non-structural protein 3 |

| DUB |

de-ubiquitinase |

References

- Aiello, T.F.; García-Vidal, C.; Soriano, A. Antiviral Drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Rev Esp Quimioter 2022, 35 (Suppl 3), 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Abe, Y.; Kodama, E.N.; Nabika, R.; Oishi, S.; Ohara, S.; Sato, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Fujii, N.; et al. A Novel Peptide Derived from the Fusion Protein Heptad Repeat Inhibits Replication of Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis Virus in Vitro and in Vivo. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, V.; Jidar, K.; Tatay, M.; Yeni, P. Enfuvirtide: From Basic Investigations to Current Clinical Use. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010, 11, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.-F.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.-W. Structural and Functional Properties of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein: Potential Antivirus Drug Development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, A.; Tang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Qu, J.; Lei, W.; Liu, W.J.; et al. A Pan-Coronavirus Peptide Inhibitor Prevents SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mice by Intranasal Delivery. Sci China Life Sci 2023, 66, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppisetti, R.K.; Fulcher, Y.G.; Van Doren, S.R. Fusion Peptide of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Rearranges into a Wedge Inserted in Bilayered Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13205–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.D.; Williamson, M.K.; Lewis, S.; Shoemark, D.; Carroll, M.W.; Heesom, K.J.; Zambon, M.; Ellis, J.; Lewis, P.A.; Hiscox, J.A.; et al. Characterisation of the Transcriptome and Proteome of SARS-CoV-2 Reveals a Cell Passage Induced in-Frame Deletion of the Furin-like Cleavage Site from the Spike Glycoprotein. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Mayr, L.M.; Minor, D.L.; Milhollen, M.A.; Burgess, M.W.; Kim, P.S. Identification of D-Peptide Ligands through Mirror-Image Phage Display. Science 1996, 271, 1854–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, N.E.; Seo, M.-H.; Yadav, V.K.; Jeon, J.; Nim, S.; Krystkowiak, I.; Blikstad, C.; Dong, D.; Markova, N.; Kim, P.M.; et al. Discovery of Short Linear Motif-Mediated Interactions through Phage Display of Intrinsically Disordered Regions of the Human Proteome. FEBS J 2017, 284, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Buckley, V.; Moman, E.; Coleman, L.; Meade, G.; Kenny, D.; Devocelle, M. Inhibition of Platelet Adhesion by Peptidomimetics Mimicking the Interactive β-Hairpin of Glycoprotein Ibα. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3323–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, C.; Ali, M.; Krystkowiak, I.; Simonetti, L.; Sayadi, A.; Mihalic, F.; Kliche, J.; Andersson, E.; Jemth, P.; Davey, N.E.; et al. Proteome-scale Mapping of Binding Sites in the Unstructured Regions of the Human Proteome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.E.; Sidhu, S.S. Chapter Fifteen - Engineering and Analysis of Peptide-Recognition Domain Specificities by Phage Display and Deep Sequencing. In Methods in Enzymology; Keating, A.E., Ed.; Methods in Protein Design; Academic Press, 2013; Vol. 523, pp. 327–349.

- Matsuyama, S.; Nao, N.; Shirato, K.; Kawase, M.; Saito, S.; Takayama, I.; Nagata, N.; Sekizuka, T.; Katoh, H.; Kato, F.; et al. Enhanced Isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-Expressing Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 7001–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nao, N.; Sato, K.; Yamagishi, J.; Tahara, M.; Nakatsu, Y.; Seki, F.; Katoh, H.; Ohnuma, A.; Shirogane, Y.; Hayashi, M.; et al. Consensus and Variations in Cell Line Specificity among Human Metapneumovirus Strains. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0215822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, S.; Kenny, G.; Alrawahneh, T.; Francois, N.; Gu, L.; Angeliadis, M.; d’Autume, V. de M.; Leon, A.G.; Feeney, E.R.; Yousif, O.; et al. Development of a Novel Medium Throughput Flow-Cytometry Based Micro-Neutralisation Test for SARS-CoV-2 with Applications in Clinical Vaccine Trials and Antibody Screening. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0294262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.-Y.; Wu, S.-L.; Chen, J.-C.; Wei, Y.-C.; Cheng, S.-E.; Chang, Y.-H.; Liu, H.-J.; Hsiang, C.-Y. Design and Biological Activities of Novel Inhibitory Peptides for SARS-CoV Spike Protein and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Interaction. Antiviral Res. 2006, 69, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, I.-J.; Kao, C.-L.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Wey, M.-T.; Kan, L.-S.; Wang, W.-K. Identification of a Minimal Peptide Derived from Heptad Repeat (HR) 2 of Spike Protein of SARS-CoV and Combination of HR1-Derived Peptides as Fusion Inhibitors. Antivir. Res 2009, 81, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badani, H.; Garry, R.F.; Wimley, W.C. Peptide Entry Inhibitors of Enveloped Viruses: The Importance of Interfacial Hydrophobicity. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1838, 2180–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, J.; Pérez-Berná, A.J.; Moreno, M.R.; Villalaín, J. Identification of the Membrane-Active Regions of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Membrane Glycoprotein Using a 16/18-Mer Peptide Scan: Implications for the Viral Fusion Mechanism. J Virol 2005, 79, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionov, Y.; Rogovskyy, A.S. Comparison of Motif-Based and Whole-Unique-Sequence-Based Analyses of Phage Display Library Datasets Generated by Biopanning of Anti-Borrelia Burgdorferi Immune Sera. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0226378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matochko, W.L.; Chu, K.; Jin, B.; Lee, S.W.; Whitesides, G.M.; Derda, R. Deep Sequencing Analysis of Phage Libraries Using Illumina Platform. Methods 2012, 58, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoofnagle, A.N.; Whiteaker, J.R.; Carr, S.A.; Kuhn, E.; Liu, T.; Massoni, S.A.; Thomas, S.N.; Townsend, R.R.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Boja, E.; et al. Recommendations for the Generation, Quantification, Storage, and Handling of Peptides Used for Mass Spectrometry-Based Assays. Clin Chem 2016, 62, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, C.I.; Galloway, J.; Chu, H.Y.; Shipley, M.M.; Sung, K.; Itell, H.L.; Wolf, C.R.; Logue, J.K.; Magedson, A.; Garrett, M.E.; et al. Epitope Profiling Reveals Binding Signatures of SARS-CoV-2 Immune Response in Natural Infection and Cross-Reactivity with Endemic Human CoVs. Cell Rep. 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Pustovalova, Y.; Shi, W.; Gorbatyuk, O.; Sreeramulu, S.; Schwalbe, H.; Hoch, J.C.; Hao, B. Crystal Structure of the CoV-Y Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 3. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; et al. Fusion Mechanism of 2019-nCoV and Fusion Inhibitors Targeting HR1 Domain in Spike Protein. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.J.; Martina, B.E.E.; van der Zee, R.; Lepault, J.; Haijema, B.J.; Versluis, C.; Heck, A.J.R.; de Groot, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Rottier, P.J.M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Infection Inhibition Using Spike Protein Heptad Repeat-Derived Peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 8455–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Xu, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Shen, X.; Zhou, J.; Xu, L.; Pu, J.; Yang, C.; Huang, Y.; et al. A Five-Helix-Based SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Inhibitor Targeting Heptad Repeat 2 Domain against SARS-CoV-2 and Its Variants of Concern. Viruses 2022, 14, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacon, C.; Tucker, C.; Peng, L.; Lee, C.-C.D.; Lin, T.-H.; Yuan, M.; Cong, Y.; Wang, L.; Purser, L.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Target the Coronavirus Fusion Peptide. Science 2022, 377, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Zhu, L.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Lv, H. An Integrated View of Deubiquitinating Enzymes Involved in Type I Interferon Signaling, Host Defense and Antiviral Activities. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 742542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Song, J.; Sun, Y.; Qi, F.; Liu, L.; Jin, Y.; McNutt, M.A.; Yin, Y. Mutations of Deubiquitinase OTUD1 Are Associated with Autoimmune Disorders. J Autoimmun 2018, 94, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Pan, M.; Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Q. The Regulatory Network of Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase-Stimulator of Interferon Genes Pathway in Viral Evasion. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 790714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.G.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tseng, M.; Barretto, N.; Lin, R.; Peters, C.J.; Tseng, C.-T.K.; Baker, S.C.; et al. Regulation of IRF-3-Dependent Innate Immunity by the Papain-like Protease Domain of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 32208–32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Qian, L.; Feng, Q.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Miao, Y.; Guo, T.; et al. Induction of OTUD1 by RNA Viruses Potently Inhibits Innate Immune Responses by Promoting Degradation of the MAVS/TRAF3/TRAF6 Signalosome. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liuyu, T.; Yu, K.; Ye, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ren, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Lin, D.; Zhong, B. Induction of OTUD4 by Viral Infection Promotes Antiviral Responses through Deubiquitinating and Stabilizing MAVS. Cell Res 2019, 29, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Hou, P.; Pan, W.; He, W.; He, D.C.; Wang, H.; He, H. DDIT3 Targets Innate Immunity via the DDIT3-OTUD1-MAVS Pathway to Promote Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Replication. J Virol 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Cheng, A.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Huang, J.; Jia, R. Viruses Utilize Ubiquitination Systems to Escape TLR/RLR-Mediated Innate Immunity. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1065211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Shen, J. MAVS Ubiquitylation: Function, Mechanism, and Beyond. Front Biosci Landmark Ed 2024, 29, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-G.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Xin, N.; Li, S.; Miao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Guo, T.; et al. Depression Compromises Antiviral Innate Immunity via the AVP-AHI1-Tyk2 Axis. Cell Res 2022, 32, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ishida, R.; Strilets, T.; Cole, J.; Lopez-Orozco, J.; Fayad, N.; Felix-Lopez, A.; Elaish, M.; Evseev, D.; Magor, K.E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 1 Inhibits the Interferon Response by Causing Depletion of Key Host Signaling Factors. J Virol 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Gao, M.; Gao, X.; Zhu, B.; Huang, J.; Luo, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Deng, M.; Lou, Z. SARS-CoV-2 Non-Structural Protein 13 (Nsp13) Hijacks Host Deubiquitinase USP13 and Counteracts Host Antiviral Immune Response. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Whalley, J.P.; Knight, J.C.; Wicker, L.S.; Todd, J.A.; Ferreira, R.C. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Induces a Long-Lived pro-Inflammatory Transcriptional Profile. Genome Med 2023, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sartori, M.A.; Makhnevych, T.; Federowicz, K.E.; Dong, X.; Liu, L.; Nim, S.; Dong, A.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Generation and Validation of Intracellular Ubiquitin Variant Inhibitors for USP7 and USP10. J Mol Biol 2017, 429, 3546–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Mallette, E.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, W. Development of an OTUD1 Ubiquitin Variant Inhibitor. Biochem J 2023, 480, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzelius, B.A. Ultrastructure of Human Nasal Epithelium during an Episode of Coronavirus Infection. Virchows Arch. 1994, 424, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilvers, M.A.; McKean, M.; Rutman, A.; Myint, B.S.; Silverman, M.; O’Callaghan, C. The Effects of Coronavirus on Human Nasal Ciliated Respiratory Epithelium. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 18, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertilsson, F.; Hikmet, F.; Hansen, J.N.; Uhlén, M.; Méar, L.; Lindskog, C. A High-Resolution Subcellular Map of Proteins in Ciliated Cells 2025, 2025. 03.18.64 3967.

- S Banach, B.; Orenstein, J.M.; Fox, L.M.; Randell, S.H.; Rowley, A.H.; Baker, S.C. Human Airway Epithelial Cell Culture to Identify New Respiratory Viruses: Coronavirus NL63 as a Model. J. Virol. Methods 2009, 156, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcioglu Batur, L.; Hekim, N. The Role of DBP Gene Polymorphisms in the Prevalence of New Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection and Mortality Rate. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speeckaert, M.M.; De Buyzere, M.L.; Delanghe, J.R. Vitamin D Binding Protein Polymorphism and COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.L.; Freed, J.H. SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Has a Greater Membrane Perturbating Effect than SARS-CoV with Highly Specific Dependence on Ca2+. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).