1. Introduction

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), most often defined as two or more consecutive spontaneous miscarriages before 20–24 weeks of gestation, affects approximately 1–5% of women of reproductive age [

1]. Despite exhaustive investigations for uterine anomalies, parental karyotypes, endocrinopathies, autoimmune conditions (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome), and infectious or hormonal causes, up to 50–75% of RPL cases remain unexplained [

1,

2]. This high proportion of idiopathic cases has led researchers to scrutinize additional contributory pathways, among which inherited thrombophilia and coagulation dysregulation are compelling candidates.

The concept that hemostatic imbalances may predispose to early pregnancy failure rests on the notion that subclinical microthrombi, impaired uteroplacental perfusion, or dysregulated fibrin turnover might compromise trophoblast invasion or placental development. In this paradigm, common single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in genes of the coagulation cascade may subtly modulate levels or activity of clotting factors, thereby shifting the systemic or local balance toward a prothrombotic state. Integrating genotypes with functional coagulation phenotypes (e.g., clotting times, factor activity) offers a promising strategy to move beyond mere association toward mechanistic insight. Despite multiple studies addressing classical thrombophilia markers (e.g., Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, MTHFR 677C>T), their explanatory power in RPL cohorts has been modest and inconsistent [

1,

3,

4]. Moreover, many studies lack concurrent measurement of coagulation phenotypes, limiting the ability to link genetic variation to functional consequences. Beyond these canonical variants, components of the contact pathway, such as coagulation Factor XII (FXII), have attracted renewed attention. Recent work highlights potential links between FXII activity and adverse pregnancy outcomes, suggesting that functional alterations in this pathway may contribute to pregnancy loss [

3,

4]. These insights align with a broader view that coagulation parameters (e.g., INR, aPTT) and related biochemical markers (e.g., fibrinogen, D-dimer, folate, homocysteine) can serve as phenotypic readouts of underlying genetic variation influencing hemostasis [

2,

5,

6].

From this perspective, two single-nucleotide variants assume relevance, on gene F7 the SNV rs6046 (Arg353Gln, also known as R353Q) this missense variant on the coagulation factor VII has been extensively studied in cardiovascular and thrombosis research. The allele encoding the amino acid Gln is associated with lower plasma FVII levels and activity in numerous populations [

7]. However, only recently has this variant been tested in the context of RPL. In an Iranian study of 144 women with RPL vs 150 controls, Kavosh et al. [

7] reported a significant difference in genotype frequencies, with an odds ratio indicating a protective effect for the allele encoding the Gln in several genetic models. Nevertheless, that work did not incorporate measurements of INR, PT, or FVII activity in carriers vs non-carriers. In addition, the SNV rs1801020 in the gene F12, has been mechanistically linked to reduced translation and lower Factor XII levels/activity, and genome-wide association studies have shown that rs1801020 contributes significantly to interindividual variation in aPTT and FXII activity [

1]. Yet, its direct role in RPL remains underexplored. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies testing the association of the SNV rs1801020 with RPL.

Thus, the literature contains a precedent for rs6046 being associated with RPL risk, but without functional coagulation correlation, and a solid mechanistic basis for rs1801020 influencing clotting phenotypes but not previously investigated in RPL in tandem with coagulation metrics.

Given that Mexican and Latin American populations remain underrepresented in thrombophilia/RPL research and considering potential allele frequency differences and gene-environment interactions there is a distinct rationale for focusing on these two SNVs in a Mexican RPL cohort with measurement of coagulation parameters [

8]. Herein, by genotyping F7-rs6046 and F12-rs1801020 alongside a panel of other thrombophilia-related SNVs, and correlating them with a complete coagulation profile (INR, PT, aPTT, TT, fibrinogen, D-dimer, homocysteine, antithrombin III, FXII activity), we aim to bridge the gap between genotype and phenotype in RPL.

In the present study, we evaluated the association of thrombophilia-related SNVs with coagulation parameters in women with RPL. F7-rs6046 was significantly associated with alterations in INR or PT, and F12-rs1801020 is associated with differences in FXII activity and aPTT in the same cohort. By combining a multifactorial genotyping panel with biochemical and hemostatic measurements, we seek to clarify whether these two SNVs may influence hemostatic balance in the RPL setting, thus offering mechanistic and potentially translational insight into a challenging and incompletely understood cause of pregnancy loss.The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

A total of 105 women were recruited between July 2021 and April 2024 as part of a retrospective descriptive study. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of RPL, genomic profile data for SNVs related to thrombophilia and coagulation parameters taken before the initiation of anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy or any supplemental treatment reported by the patient were included. The women without baseline coagulation parameters measurements or a previous clinical diagnosis of thrombophilia were excluded.

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Coordination of the Board of Education in Health Sciences (registration number 2024.260). All participants had previously provided informed consent for the use of their data in academic and research contexts, in accordance with the General Law on Protection of Personal Data Held by Obligated Subjects, Article 22, Sections V and VII.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using standard protocols. SNVs were genotyped using real-time PCR with custom TaqMan probes. SNVs analyzed were angiotensinogen (AGT: rs4762, rs699), factor VII (F7: rs6046), fibrinogen (FGB: rs1800790), 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate-homocysteine S-methyltransferase (MTR: rs1805087), methionine synthase reductase (MTRR: rs1801394), 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR: rs1801133, rs1801131), factor II (F2: rs1799963), factor V (F5: rs6025), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (SERPINE1: rs1799889), factor XII (F12: rs1801020) and the A1 subunit of factor XIII (F13A1: rs5985). F12-rs1801020 and F13A1-rs5985 were not part of the panel design in 2021 and were included in 2022.

Statistical Methods

Quantitative variables’ distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Allelic and genotypic frequencies were compared using Fisher’s exact test to assess for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis) were used to compare metabolite levels across genotypes. The p-value of <0.01 was considered statistically significant. Significant pairwise differences were further explored using linear regression under various genetic inheritance models (codominant, dominant, recessive, overdominant, additive). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess linear relationships. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp) and SNPStats were used for inheritance model testing [

9]. Genotype distributions were visualized using Finetti plots generated with the HardyWeinberg package in R (via Datalab).

3. Results

The study population included 105 women with a mean age of 32.5 years (range, 19–42 years; SD, 3.9). Obstetric histories revealed a mean of 3.38 pregnancies (range, 2–7; SD, 1.18) and a mean of 2.9 miscarriages (range, 2–7; SD, 0.97). Nine women (8.6%) had a history of at least one vaginal delivery, thirteen (12.4%) had undergone cesarean section, two (1.9%) had a history of molar pregnancy, and twelve (11.4%) had experienced at least one ectopic pregnancy.

Biochemical analysis showed that mean metabolite values were generally within the reference ranges defined by the testing laboratories, except for folic acid (mean, 22.15 ng/mL; reference range, 3.1–20.5 ng/mL) and thrombin time (mean, 15.94 sec reference range, 13–15.8 sec), which exceeded the upper reference limit. Most metabolite values exhibited broader ranges than the reference intervals, though homocysteine levels remained within normal limits (range, 5.0–13.8 μmol/L; reference range, 5–15 μmol/L) (Supplementary Table S1).

4. Discussion

The present study emphasizes the relationship between thrombophilia-related SNVs and their downstream on coagulation and biochemical parameters, in contrast to most previous studies that primarily focused on the association between these genetic variants and RPL [

10,

11]. More than 80% of participants originated from the metropolitan region, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader Mexican population. The genomic panel employed was designed under the hypothesis that thrombophilia-associated SNVs may exacerbate the prothrombotic state characteristic of pregnancy, promoting placental thrombosis and compromising maternal-fetal exchange [

12]. Among the evaluated SNVs, two showed statistically significant associations with hemostatic markers: rs6046 in the F7 gene, part of the extrinsic coagulation pathway, and rs1801020 in F12, a key player in the intrinsic pathway.

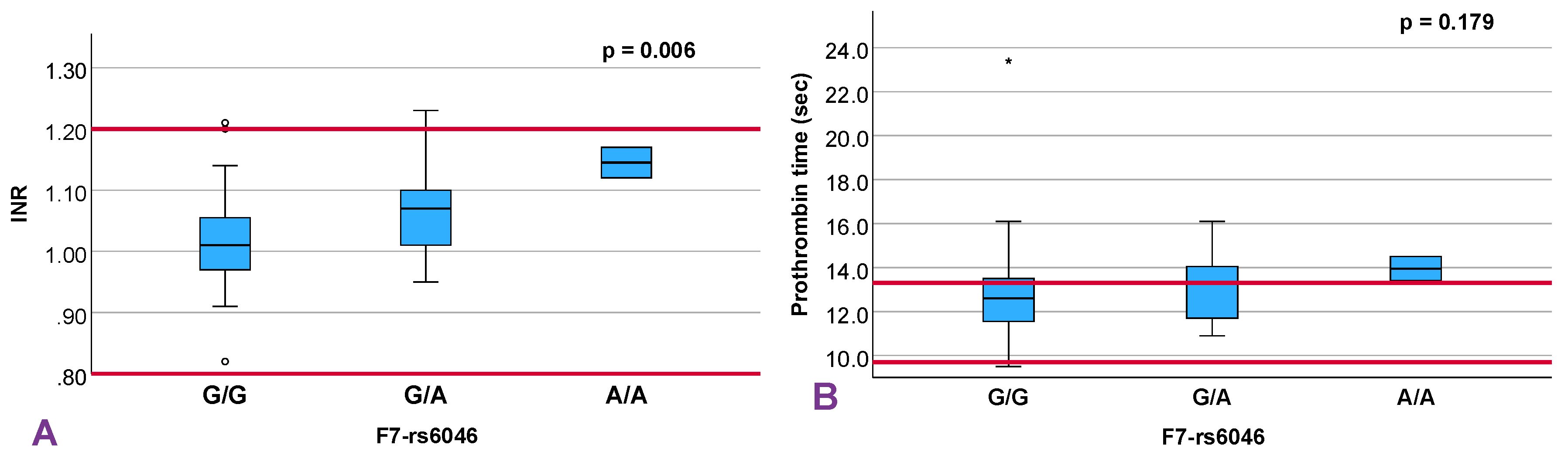

The rs6046 variant in F7 has been functionally linked to reduced factor VII activity—up to 30% in heterozygotes and 43% in homozygotes [

13]. F7 encodes a protein essential for the initiation of coagulation via tissue factor binding and subsequent activation of factor X [

14]. The minor allele frequency (MAF) of rs6046 in our cohort (0.1285) closely matched that reported globally (0.1265) (7), supporting the robustness of our findings. Soria et al. [

15] demonstrated that genetic variability in F7 contributes significantly to factor VII activity, with seven variants accounting collectively for over one-third of its phenotypic variance, reinforcing its polygenic regulation. Although we observed a slight trend toward PT with increasing rs6046 risk alleles (p = 0.179), INR was significantly elevated. This finding complements prior research showing that rs6046 may offer protective effects in RPL; one study reported an OR of 0.35 (95% CI, 0.23–0.53; p < 0.0001) [

16]. These effects may arise from modest downregulation of coagulation in a hypercoagulable environment, consistent with INR prolongation in our cohort.

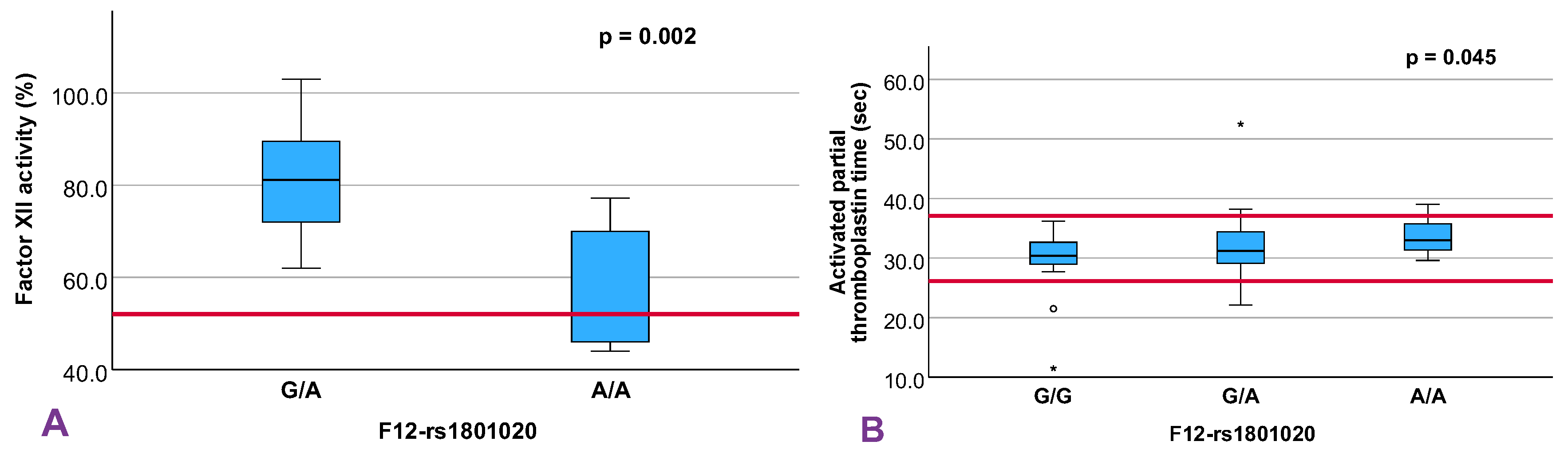

In contrast, the rs1801020 variant in F12 demonstrated robust associations with both factor XII activity and aPTT, in line with previous reports. F12 encodes the zymogen FXII, which plays roles not only in intrinsic coagulation but also in fibrinolysis, inflammation, and complement activation [

17,

18,

19]. Calafell et al.[

20] identified rs1801020 as the principal determinant of FXII activity in a Spanish cohort. This SNV may affect translation through two proposed mechanisms: (1) creation of an upstream start codon resulting in a truncated peptide [

20,

21,

22], or (2) disruption of the Kozak sequence impairing translation initiation [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Our findings confirmed a significant genotype-dependent reduction in FXII activity. In comparison with published data from Kanaji et al. [

23] and Calafell et al. [

20], our activity values for heterozygotes (C/T = 81.8%) and homozygotes (T/T = 56.9%) closely mirror those in thrombosis-related cohorts, despite not measuring wild-type individuals (C/C). The aPTT prolongation observed in our cohort (mean difference, 2.17 seconds; 95% CI, 0.50–3.84) under an additive model also exceeded that reported in the ARIC study by Weng et al. [

27], where rs1801020 accounted for 11%–12% of aPTT variance in both European and African Americans. The stronger effect observed here may be explained by phenotype-based cohort enrichment or population-specific genetic architecture, warranting further investigation.

Interethnic variability in rs1801020 allele frequency is well documented. The T allele is found at frequencies of 0.18 in Spanish, 0.25 in Dutch [

25,

28], and up to 0.73 in Japanese populations [

23,

25]. In our cohort, MAF reached 0.44, closely resembling that of African ancestry groups [

27]. While this may reflect a phenotype-driven enrichment, future studies comparing this frequency in population-based Mexican cohorts are needed to determine whether this variant contributes to RPL risk at the population level.

Although this is the first study in Mexico to evaluate associations between thrombophilia-related SNVs and their metabolic correlates in RPL, prior work by Domínguez et al.[

19] assessed factor XII activity and aPTT in venous thromboembolism. Their reported values were similar to those in our cohort, although their broader measurement range, particularly for FXII activity, may reflect the inclusion of wild-type individuals.

Our findings suggest that rs1801020 contributes to variation in FXII activity and aPTT prolongation but is unlikely to explain the RPL phenotype. These data support the concept that the SNV under investigation may act as contributory—not singular—factors in RPL. Their pathogenic effects likely depend on broader genetic context, metabolic state, and pregnancy-specific physiological conditions. These emerging associations may pave the way for clinically relevant, personalized interventions tailored to the allelic profiles of women affected by RPL.

Finally, the retrospective design and metropolitan recruitment of our cohort limit the generalizability of these results. Prospective studies incorporating participants from diverse geographic regions across the country are needed to overcome current design limitations and enhance the generalizability and impact of the findings. Metabolomics research could also be expanded to involve other SNVs related to inflammatory or other related disease pathways to benefit personalized medicine in RPL.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first effort in Mexico to investigate the relationship between thrombophilia-related SNVs and associated coagulation parameters in women with RPL. The primary outcome was the identification of significant associations between two SNVs, F7-rs6046 and F12-rs1801020, and alterations in coagulation parameters, specifically INR and aPTT, in Mexican women with RPL. These findings support the notion that specific genetic variants involved in coagulation pathways may modulate coagulation processes and contribute to a prothrombotic state that impairs placental function and, ultimately, pregnancy viability.

The observed effects were consistent with previous functional evidence and appear more pronounced in this phenotypically enriched cohort, underscoring the potential value of integrating genetic and biochemical data in the clinical evaluation of RPL. In this context, the results suggest that integrating genetic screening into the clinical evaluation of RPL may enhance personalized risk stratification and inform targeted therapeutic strategies.

Overall, this study contributes to foundational knowledge on the pathophysiology of RPL and highlights the importance of a comprehensive and systematic approach to its etiology—particularly in genetically diverse populations. Given the multifactorial nature of thrombophilia and its variable expression across individuals, future research in broader, unselected cohorts is warranted to validate these findings and further explore their clinical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.L.M., L.L.R. and R.S.M.; Methodology, L.F.L.M., L.L.R., M.A.R. and S.V.T.; Software, L.F.L.M., A.C.F. and Y.Z.R.L.; Validation, A.C.F., P.C.S.V., A.H.B., H.J.B.O. and Y.M.M.; Formal Analysis, L.F.L.M., M.A.R., V.Z.C. and S.V.T.; Investigation, L.L.R., M.A.R., A.C.F., P.C.S.V., Y.Z.R.L., Y.M.M. and M.A.L.F.; Resources, A.H.B., V.Z.C., R.S.M. and H.J.B.O.; Data Curation, L.F.L.M., L.L.R., M.A.L.F. and M.A.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.F.L.M., L.L.R. and Y.M.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, R.S.M., A.H.B., V.Z.C. and H.J.B.O.; Visualization, L.F.L.M., A.C.F. and S.V.T.; Supervision, R.S.M. and V.Z.C.; Project Administration, L.F.L.M. and R.S.M.; Funding Acquisition, R.S.M, H.J.B.O. and V.Z.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Coordination of the Board of Education in Health Sciences (registration number 2024.260).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participants and their relatives for their collaboration in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGT |

Angiotensinogen gene |

| aPTT |

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| F2 |

Coagulation Factor II (Prothrombin) |

| F5 |

Coagulation Factor V |

| F7 |

Coagulation Factor VII |

| F12 |

Coagulation Factor XII |

| F13A1 |

Coagulation Factor XIII A1 Subunit |

| FGB |

Fibrinogen Beta Chain gene |

| FXII |

Coagulation Factor XII protein |

| HWE |

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| INR |

International Normalized Ratio |

| MAF |

Minor Allele Frequency |

| MTHFR |

5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase gene |

| MTR |

5-Methyltetrahydrofolate–Homocysteine Methyltransferase gene |

| MTRR |

Methionine Synthase Reductase gene |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PT |

Prothrombin Time |

| RPL |

Recurrent Pregnancy Loss |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SERPINE1 |

Serpin Family E Member 1 gene (Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1) |

| SNV/SNVs |

Single Nucleotide Variant(s) |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TT |

Thrombin Time |

References

- Turesheva, A.; Aimagambetova, G.; Ukybassova, T.; Marat, A.; Kanabekova, P.; Kaldygulova, L.; Amanzholkyzy, A.; Ryzhkova, S.; Nogay, A.; Khamidullina, Z.; et al. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Etiology, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Management. Fresh Look into a Full Box. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; He, H.; Zhao, K. Thrombophilic Gene Polymorphisms and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2023, 40, 1533–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard, E.; Pedersen, M.K.; Bor, P.; Bor, M.V. Revisiting the Link Between Factor XII and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Scoping Review. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2025, 94, e70127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, N.; Aktün, L.H. Evaluation of Factor XII Activity in Women with Recurrent Miscarriages. Bezmialem Science 2018, 6, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrnos, L.; Gangaraju, R. Inherited Thrombophilia and Recurrent Miscarriage: Is There a Role for Anticoagulation during Pregnancy? Hematology: the American Society of Hematology Education Program 2024, 2024, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayal, H.B.; Beksac, M.S. The Effect of Hereditary Thrombophilia on Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavosh, Z.; Mohammadzadeh, Z.; Alizadeh, S.; Sharifi, M.J.; Hajizadeh, S.; Choobineh, H.; Omidkhoda, A. Factor VII R353Q (Rs6046), FGA A6534G (Rs6050), and FGG C10034T (Rs2066865) Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss in Iranian Women. Indian Journal of Hematology & Blood Transfusion 2023, 40, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Delgado, G.J.; Cantero-Fortiz, Y.; Mendez-Huerta, M.A.; Leon-Gonzalez, M.; Nuñez-Cortes, A.K.; Leon-Peña, A.A.; Olivares-Gazca, J.C.; Ruiz-Argüelles, G.J. Primary Thrombophilia in Mexico XII: Miscarriages Are More Frequent in People with Sticky Platelet Syndrome. Turkish Journal of Hematology 2017, 34, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, X.; Guinó, E.; Valls, J.; Iniesta, R.; Moreno, V. SNPStats: A Web Tool for the Analysis of Association Studies. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1928–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Ramos, A.; Valdez-Velázquez, L.L.; Hernández, G.; Baltazar, L.M.; Padilla-Gutiérrez, J.R.; Valle, Y.; Rodarte, K.; Ortiz, R.; Ortiz-Aranda, M.; Olivares, N. Evaluación de Cinco Polimorfismos de Genes Trombofílicos En Parejas Con Aborto Habitual. Gac Med Mex 2006, 142, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- López-Jiménez, J.J. ; Porras-Dorantes; Juárez-Vázquez, C.I.; García-Ortiz, J.E.; Fuentes-Chávez, C.A.; Lara-Navarro, I.J.; Jaloma-Cruz, A.R. Molecular Thrombophilic Profile in Mexican Patients with Idiopathic Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Genetics and Molecular Research, 2016; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordaeva, O.Y.; Derevyanchuk, E.G.; Alset, D.; Amelina, M.A.; Shkurat, T.P. The Prevalence and Linkage Disequilibrium of 21 Genetic Variations Related to Thrombophilia, Folate Cycle, and Hypertension in Reproductive Age Women of Rostov Region (Russia). Ann Hum Genet 2024, 88, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alesci, R.S.; Hecking, C.; Racké, B.; Janssen, D.; Dempfle, C.E. Utility of ACMG Classification to Support Interpretation of Molecular Genetic Test Results in Patients with Factor VII Deficiency. Front Med 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olgasi, C.; Assanelli, S.; Cucci, A.; Follenzi, A. Hemostasis and Endothelial Functionality: The Double Face of Coagulation Factors. Haematologica 2024, 109, 282272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.M.; Almasy, L.; Souto, J.C.; Sabater-Lleal, M.; Fontcuberta, J.; Blangero, J. The F7 Gene and Clotting Factor VII Levels: Dissection of a Human Quantitative Trait Locus. Hum Biol 2005, 77, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavosh, Z.; Mohammadzadeh, Z.; Alizadeh, S.; Sharifi, M.J.; Hajizadeh, S.; Choobineh, H.; Omidkhoda, A. Factor VII R353Q (Rs6046), FGA A6534G (Rs6050), and FGG C10034T (Rs2066865) Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss in Iranian Women. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion 2024, 40, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanaev, A.; Litvak, M.; Gailani, D. Recent Advances in Factor XII Structure and Function. Curr Opin Hematol 2022, 29, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnoff, O.D.; Busse Jr, R.J.; Sheon, R.P. The Demise of John Hageman. New England Journal of Medicine 1968, 279, 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Reyes, V.M.; Hernandez-Juarez, J.; Arreola-Diaz, R.; Majluf-Cruz, K.; Reyes-Maldonado, E.; Alvarado-Moreno, J.A.; Ruiz, L.A.M.; Majluf-Cruz, A. Factor XII Deficiency in Mexico: High Prevalence in the General Population and Patients with Venous Thromboembolic Disease. Arch Med Res 2024, 55, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, F.; Almasy, L.; Sabater-Lleal, M.; Buil, A.; Mordillo, C.; Ramírez-Soriano, A.; Sikora, M.; Souto, J.C.; Blangero, J.; Fontcuberta, J.; et al. Sequence Variation and Genetic Evolution at the Human F12 Locus: Mapping Quantitative Trait Nucleotides That Influence FXII Plasma Levels. Hum Mol Genet 2009, 19, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Maihofer, A.X.; Mir, S.A.; Rao, F.; Zhang, K.; Khandrika, S.; Mahata, M.; Friese, R.S.; Hightower, C.M.; Mahata, S.K.; et al. Polymorphisms at the F12 and KLKB1 Loci Have Significant Trait Association with Activation of the Renin-Angiotensin System. BMC Med Genet 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater-Lleal, M.; Chillón, M.; Mordillo, C.; Martínez, Á.; Gil, E.; Mateo, J.; Blangero, J.; Almasy, L.; Fontcuberta, J.; Soria, J.M. Combined Cis-Regulator Elements as Important Mechanism Affecting FXII Plasma Levels. Thromb Res 2010, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaji, T.; Okamura, T.; Osaki, K.; Kuroiwa, M.; Shimoda, K.; Hamasaki, N.; Niho, Y. A Common Genetic Polymorphism (46 C to T Substitution) in the 5′-Untranslated Region of the Coagulation Factor XII Gene Is Associated with Low Translation Efficiency and Decrease in Plasma Factor XII Level. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 1998, 91, 2010–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, N.C.; Butenas, S.; Lange, L.A.; Lange, E.M.; Cushman, M.; Jenny, N.S.; Walston, J.; Souto, J.C.; Soria, J.M.; Chauhan, G.; et al. Coagulation Factor XII Genetic Variation, Ex Vivo Thrombin Generation, and Stroke Risk in the Elderly: Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2015, 13, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.Y.; Tuite, A.; Morange, P.E.; Tregouet, D.A.; Gagnon, F. The Factor XII -4C>T Variant and Risk of Common Thrombotic Disorders: A HuGE Review and Meta-Analysis of Evidence from Observational Studies. Am J Epidemiol 2011, 173, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum-Asfar, S.; de la Morena-Barrio, M.E.; Esteban, J.; Miñano, A.; Aroca, C.; Vicente, V.; Roldán, V.; Corral, J. Assessment of Two Contact Activation Reagents for the Diagnosis of Congenital Factor XI Deficiency. Thromb Res 2018, 163, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.C.; Cushman, M.; Pankow, J.S.; Basu, S.; Boerwinkle, E.; Folsom, A.R.; Tang, W. A Genetic Association Study of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time in European Americans and African Americans: The ARIC Study. Hum Mol Genet 2015, 24, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmann, J.L.; de Haan, H.G.; Algra, A.; Vossen, C.Y.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Siegerink, B. Genetic Determinants of Activity and Antigen Levels of Contact System Factors. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2019, 17, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).