1. Introduction

The influence of negative emotions on cognition has been documented across various domains, from fundamental processes like attention, memory, reasoning, and decision-making (for reviews, see Lemaire, 2021; Robinson et al., 2013a), to more specific tasks such as arithmetic problem-solving (e.g., Fabre & Lemaire, 2019; Melani et al., 2025) and time estimation (e.g., Droit-Volet & Gil, 2009; Droit-Volet & Meck, 2007; Gil & Droit-Volet, 2011). Although previous studies showed that negative emotions influence cognitive performance, it remains unclear whether negative emotions modulate all executive processes equally, or whether they selectively disrupt specific mechanisms. To address this issue, the present study investigates how negative emotions modulate the three core components of cognitive control: inhibition, updating, and shifting, within the same group of participants. This within-subject design allows for a direct comparison of emotions effect across distinct control processes and provides a more integrated understanding of how negative emotions influence cognition.

1.1. Emotions Effect on Cognition

Emotions have been shown to either impair performance (e.g., Dresler et al., 2009; Keefe et al., 2019), enhance performance (Hsieh & Lin, 2019; Phelps et al., 2006; Robinson et al., 2013b), or exert no measurable effect on behavioral outcomes (for a review see Lemaire, 2021). Most theoretical hypotheses on emotions effect converge on the idea that emotions effect arises from interactions between attentional mechanisms and domain-specific cognitive mechanisms (Blanchette et al., 2014; Blanchette & Caparos, 2013; Caparos & Blanchette, 2017; Ellis & Ashbrook, 1989; Ellis & Moore, 1999; Okon-Singer et al., 2015; Padmala et al., 2011; Pessoa, 2009; Pratto & John, 1991; Yiend et al., 2013). However, the precise mechanisms through which negative emotions influence cognition remain unclear, particularly regarding how negative emotions capture attention and interfere with or support specific cognitive functions. Building on this perspective, several studies have suggested that negative emotions exert a stronger influence on attentional allocation (e.g., Padmala et al., 2011). Pessoa (2009) emphasized that negative emotions, particularly threat-related stimuli, tend to produce more detrimental effects on behavioral performance. Consistent with this view, highly negative stimuli automatically capture attentional resources and place greater demands on a “common-pool resources” shared by inhibition, updating, and shifting. In other words, cognitive control processes rely on domain-general resources. To further identify through which mechanisms emotions modulate cognition, the present study focuses specifically on the influence of negative emotions, given their well-established capacity to modulate cognitive control.

Cognitive control refers to the capacity to regulate behavior in accordance with internal goals through attentional orientation, by prioritizing task-relevant information and inhibiting distractions or irrelevant responses (Amer et al., 2016; Gratton et al., 2018; Hommel et al., 2002). This control system plays a central role in minimizing interference and supporting behavioral flexibility, particularly in situations involving novel or conflicting demands (Banich et al., 2024). Cognitive control is generally assumed to rely on three executive processes: inhibition, updating and shifting (Banich et al., 2024; Friedman & Miyake, 2017; Miyake et al., 2000). In the present study, the term “cognitive control processes” specifically refers to these executive function processes. Inhibition refers to the capacity to suppress prepotent or automatic responses when they are no longer appropriate for the task. It is typically assessed with paradigms such as the Go/No-Go or Stroop tasks. Updating involves actively monitoring and revising the contents of working memory (WM), replacing outdated information with goal-relevant content. Updating is generally assessed using tasks such as the n-back, which require continuous monitoring and revision of information held in working memory. Shifting, or task-switching reflects the ability to flexibly alternate between mental sets, task rules, or response strategies, and is commonly evaluated using paradigms involving frequent changes between tasks or features of the targeted stimulus. While these executive functions are conceptually distinct, they also share common variance, suggesting the existence of both domain-general and domain-specific control mechanisms (Friedman et al., 2008). Numerous paradigms have been developed to assess each executive process (for review, see Gratton et al., 2018), yet these tasks do not necessarily tap into identical subcomponents of the targeted function. This methodological heterogeneity makes it challenging to identify common mechanisms that may be sensitive to emotional influences. To enhance cross-task comparability and reduce methodological variance, the present study deliberately employed a single, prototypical task for each executive domain—namely, a Go/No-Go task for inhibition, a 2-back task for updating, and a set-switching task for cognitive flexibility. Despite the increasing interest in the interaction between emotions and executive functioning, no study examined the influence of emotions on these three cognitive control processes within the same participant sample. This is what we do in the present experiment, using a within-subject design, allowing us to compare how emotional influences may differentially influence each control mechanism.

Before outlining the rationale of the present work, we briefly review existing findings on how negative emotions modulate performance in each task.

1.2. Emotions Effect on Cognitive Control

The influence of emotions on cognitive control has been investigated through a wide range of experimental paradigms. For example, some studies have used emotional stimuli (e.g., emotional faces, emotional words) embedded directly within the task to examine how emotions influence performance in tasks assessing inhibition (Hare et al., 2005; Myruski et al., 2017; Schulz et al., 2007), updating (Kopf et al., 2013; Ladouceur et al., 2009; Levens & Gotlib, 2010), or shifting (Eckart et al., 2023; Kraft et al., 2020; Reeck & Egner, 2015). A major limitation in this body of research is that the tasks commonly used to assess the interaction between emotions and cognitive control emotional stimuli, requiring explicit recognition or judgment of the emotion. In such paradigms, emotions are inherently task-relevant. The present study adopts an emotional induction approach, whereby emotions were manipulated through the presentation of affective images drawn from the International Affective Picture System – IAPS (Lang et al., 1999) before each trial. This design allows emotions to be induced while keeping the cognitive task content neutral. The following section reviews previous studies that have used similar emotion induction procedures.

1.2.1. Inhibition

Although the impact of negative emotions on inhibitory control performance has received considerable attention, empirical results have been inconsistent. Several studies have investigated how emotions modulate response inhibition in Go/No-Go paradigms by inducing emotions through the presentation of emotional pictures prior to task execution (Albert et al., 2010; Buodo et al., 2017; De Houwer & Tibboel, 2010; Kalanthroff et al., 2016; Krompinger & Simons, 2009; Myruski et al., 2017; Ocklenburg et al., 2017; Stockdale et al., 2020). For example, to induce emotional states, Kalanthroff et al. (2016) presented IAPS pictures immediately before each Go/No-Go trial. Participants were faster to respond to Go trials under negative emotions than under neutral emotions but committed significantly more commission errors on No-Go trials. Kalanthroff and collaborators suggested that negative emotions impaired inhibition by diverting attentional resources toward emotions content. In other words, emotional stimuli capture attention, thereby depleting the cognitive resources available to inhibit incongruent stimuli and disrupting the recruitment of top-down control mechanisms required for successful inhibition (see also for the same results De Houwer & Tibboel, 2010). Buodo et al., (2017) examined how different types of unpleasant stimuli, threatrelated (e.g., attacks) versus mutilation-related (e.g., injuries), modulated performance in an emotional Go/No-Go task. While both categories impaired inhibition, threat-related pictures selectively led to faster responses on Go trials and more commission errors on No-Go trials than mutilation pictures. Buodo et al. (2017) interpreted this difference as reflecting a “freezinglike” defensive response, whereby the highly aversive but non-imminent nature of mutilation images suppresses approach-related motor tendencies. They proposed that different subtypes of negative emotions (e.g., threat versus disgust) differentially activate motivational and attentional systems, thereby leading to distinct patterns of action control: while threat-related cues may trigger a “fight-or-flight” response and heighten attention, disgust-related stimuli may instead prompt behavioral inhibition or avoidance, slowing down responses even when task demands favor quick execution. Albert et al. (2010) took a different approach by exposing participants to emotional pictures in blocks (positive, negative, or neutral) prior to performing the Go/No-Go task. The results showed that participants made more commission errors following both negative and positive emotional blocks compared to neutral ones. The authors argued that positive emotions may promote approach-related behaviors, while negative emotions may elicit withdrawal tendencies, both of which could interfere with the ability to inhibit prepotent responses. Albert and colleagues suggested that emotions can disrupt cognitive control by engaging motivational systems that bias action tendencies.

While these studies showed that emotions can modulate inhibition, their results are difficult to compare directly due to methodological heterogeneity. In particular, they differ in the emotional induction procedures used (trial-based vs. block-based), in the timing of emotional exposure (embedded within or preceding the task), and in the emotional valence and arousal of stimuli. Such differences likely contribute to the inconsistencies observed in the literature.

1.2.2. Updating

Many studies examined how negative emotions influence performance in WM tasks (e.g., Buratto et al., 2014; Grissmann et al., 2017; Ozawa et al., 2014). For example, Grissmann et al., (2017) manipulated emotions induction by presenting emotional pictures from the IAPS database as target and distractor stimuli, while WM load was varied via n-back task. Participants had to respond as quickly and accurately as possible to determine whether the current picture matched the one shown, one or two trials earlier. Emotions induction was manipulated between blocks, each block containing only positive, neutral, or negative images and each emotion condition comprised four blocks. Grissman and colleagues (2017) found that under the negative emotion conditions, participants responded more slowly and less accurately compared to the neutral or positive conditions. They found that negative emotions selectively impaired performance when cognitive demands are high, suggesting a resource competition between emotional and cognitive processes. Grissmann et al. suggested that negative emotions capture attentional resources and disrupt cognitive control processes. Buratto et al. (2014) examined how emotions influenced recognition memory when they were induced during encoding rather than embedded in the task itself. Participants encoded neutral and negative images while performing either a low-load (0-back) or high-load (3-back) task. Four hours after performing n-back task, participants were asked to recognize pictures presented during the task. Their results showed that high negative emotions have facilitating effects on recognition performance under high cognitive load (3-back). High negative emotions reduce the decline in performance across 0 and 3-back, compared to neutral emotions. Burratto and colleagues suggested that highly negative emotion stimuli draw more attention, which in turn helps preserve them in memory even when cognitive resources are recruited. Although this study does not directly measure the direct influence of emotions on n-back task performance, these results highlight the modulatory effects of emotions on attentional resources during a WM task. In another study, Ozawa et al. (2014) explored the effects of emotional pictures from IAPS on WM updating using a modified n-back task. They found no effects of negative emotions on performance.

To sum up, while some authors report impaired cognitive performance under negative emotions (e.g., Grissmann et al., 2017), others found facilitating effects (e.g., Buratto et al., 2014), or no effects of emotions on performance (e.g., Ozawa et al., 2014). These discrepancies may reflect methodological differences, such as whether emotions were task-relevant or incidental, whether they were induced before versus embedded within the task, and the intensity or type of emotional material used. Moreover, few studies have systematically disentangled whether negative emotions selectively affect specific subcomponents of working memory, such as updating versus maintenance. A large part of the literature focused on the influence of emotions on WM updating by manipulating cognitive load (e.g., through comparison across different cognitive loads: 0, 1, 2 or 3-back). This present study aims to assess the influence of emotions on the updating ability, independently of cognitive load, with a single 2-back task.

1.2.3. Shifting

Previous studies investigated how emotions influence cognitive flexibility using various task-switching paradigms (e.g., Demanet et al., 2011; Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004; Van Wouwe et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2017). However, only two studies have directly assessed the impact of negative emotions on switching performance (Demanet et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2017). In these two studies, participants were asked to shift between two distinct tasks, while emotional pictures (negative, positive and neutral) were presented prior to each trial. Wang et al. (2017) reported that participants showed no switching cost under positive emotions, while significant costs were observed under both neutral and negative conditions. Wang and colleagues suggested that positive emotions may promote cognitive flexibility by facilitating more efficient task-set reconfiguration. Demanet et al. (2011) found that only higharousing pictures impaired task-switching performance, while emotional valence had no significant effect. These results suggest that cognitive shifting is more sensitive to arousal intensity than to valence per se. Together, these findings highlight the limited understanding of how negative emotions specifically influence shifting mechanisms. These studies present several limitations. Notably, inconsistencies in the methodologies used to induce emotional states may contribute to the divergent findings regarding the impact of emotions on shifting performance. For instance, Wang et al. (2017) employed a blocked emotional induction procedure, whereas Demanet et al. (2011) applied a trial-by-trial induction method. However, despite this more dynamic approach, Demanet and colleagues failed to observe any effect of emotional valence on task performance.

In summary, findings from the literature revealed mixed results regarding the influence of emotions on each cognitive process, which can be attributed to methodological differences across experimental protocols. Moreover, most prior studies examined the effect of emotions on a single cognitive control process, often in between-subject designs, limiting cross-process comparisons. To address these limitations, the present study employed a standardized, trial-level induction of emotional context using IAPS images. Moreover, the use of a within-subject design enables direct comparisons of emotions effect across inhibition, updating, and shifting within the same individuals. This approach allows for a better understanding of whether negative emotions uniformly disrupt cognitive control or selectively impair specific control mechanisms.

Above and beyond replicating previous findings showing interference effects under neutral emotions on each task involving inhibition (e.g., Albert et al., 2010; Kalanthroff et al., 2016), updating (e.g., Buratto et al., 2014; Grissmann et al., 2017) and shifting (e.g., Demanet et al., 2011; Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004; Wang et al., 2017), the present data were collected to test the emotions effect on cognitive control processes. We hypothesized that negative emotion processing interferes with cognitive control, but not uniformly across all processes. Instead, we expected selective disruptions depending on the executive mechanism involved. For inhibition, we predicted that negative emotions would alter interference resolution, leading to larger commission errors and slower responses on No-Go trials. For updating, we expected performance to decline under negative emotions specifically on non-match trials, with longer latencies and lower accuracy, due to difficulty disengaging from negative emotions and replacing outdated information in working memory. For shifting, we anticipated that switch trials would be more sensitive to negative emotions than repeated trials, reflected in slower and less accurate responses, indicating impaired task-set reconfiguration. Finally, we predicted that emotions effect would correlate across tasks, especially between updating and shifting, which both rely on dynamic attentional control and flexible cognitive processing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

This experiment received approval from Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est-IV in France (Ref #: 2023-A01670-45).

2.2. Sample Size

Following previous studies on the influence of emotions on cognitive control processes (Thompson et al., 2022), where effect size of Emotion × Trial-Type interactions ranged from 0.48, we used a conservative estimate ƞ²ₚ = 0.3, with an alpha level of 0.1 and a 2 x 2 repeated-measures design (Emotion and Trial Type). The analysis indicated that a minimum of 29 participants would be required to achieve 90% statistical power. We recruited 41 participants from the French Air Force Academy (14 females, mean age: 24.4 years; range: 19—33 years) to exceed this criterion.

2.3. Emotional Pictures

Nine hundred and twelve pictures were selected from the International Affective Pictures System (IAPS, Lang et al., 1999). Half of the pictures depicted negative events (

e.g., mutilation) and the other half depicted neutral events (

e.g., ironing board). Emotional valence and arousal were matched for each item (see

Table A1 in the Appendix).

2.4. Design

The PsychoPy-software (Peirce et al., 2019) controlled stimulus presentation, response recording, and collected RTs with 1 millisecond accuracy. Participants were individually tested in a single session lasting approximately 60 minutes. Each session comprised three cognitive tasks: a Go/No-Go task, a 2-back task, and a Set-Switching task. The order of tasks was randomized across participants.

2.4.1. Go/No-Go Task

The task consisted of four blocks of 96 randomly distributed trials (72 Go and 24 No-Go trials). Two distinct stimuli were used: a white “O” for Go trials, and a white “=” for the No-Go trials. Stimuli were presented at the center of a black square and measured approximately 14% of the screen height. Each trial began with a cross fixation displayed for 1000 ms, followed by an emotional picture (either neutral or negative) presented for 1000 ms. Subsequently, the stimulus was superimposed on the emotional picture and remained on screen until the participant responded or for a maximum of 500 ms. Participants were instructed to press the right arrow key of the keyboard as quickly as possible for the Go trials and to withhold their response to No-Go trials. Correct responses RTs (Go trials), false negative rate (percentage of omissions on Go trials), false positive RTs (No-Go trials), false positive rate (percentage of commissions on No-Go trials) were analyzed.

2.4.2. Two-Back Task

This task consisted of numerical digits (1–9) displayed in white font over a black square, with a height of approximately 10% of the screen. The ratio of odd to even numbers was counterbalanced across trials. Half of the participants were instructed to press the “L” key on a keyboard whenever the current number matched the one presented two trials earlier (i.e., Match trials), and to press the “S” key when there was no match (i.e., Non-Match trials). The other half received the inverse mapping. The experiment included four blocks of 72 trials (24 Match and 48 Non-Match trials). Half of the trials were presented under neutral emotions, while the remaining trials were presented under negative emotions. Each trial began with a fixation cross displayed for 1000 ms, followed by an emotional picture presented for 1000 ms. Then, the number was superimposed on the picture for 1500 ms during which participants could respond. Response times and error rates for each trial type were recorded.

2.4.3. Set-Switching Task

Participants had to respond whether a target digit number stimulus was odd or even. In each trial, two digits (one odd and one even) were displayed one above the other in distinct colors. Participants were instructed to respond based on the number presented in the target color, as indicated at the beginning of each block (e.g., “Respond to green”). Three rule-switch trials occurred per block (at Trials 8, 17 and 24), during which a new color became the target, while the previous target color became the distractor. Response mapping was counterbalanced across participants: half were instructed to press the “L” key for even numbers and the “S” key for odd numbers, and the other half the opposing mapping. Moreover, the position of both odd and even numbers was counterbalanced. They completed eight blocks of 30 trials. Each block consisted of 27 Repeated and 3 Switch trial, half were presented under neutral emotions, and other half under negative emotions. Each trial started with a fixation cross (1000 ms), followed by an emotional picture (1000 ms). Then, the digit stimuli were presented for 1000 ms, superimposed on the emotional picture. Only the four Repeated trials preceding and following a Switch trial were included in the analyses of RTs and error rates.

2.5. Data Analysis

We first examined whether negative emotions influenced performance as a function of trial type in each task (i.e., Go vs. No-Go; Match vs. Non-Match; and Repeated vs. Switch trials). Mean RTs and error rates were analyzed using 2 (Trial Type: within-subject) × 2 (Emotion: Neutral, Negative) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs).

To further assess whether the impact of emotions on cognitive control was consistent across tasks, we computed emotions effect scores for each trial type and each dependent variable (RTs and accuracy). These scores were calculated as normalized change scores using the following formula:

This formula yielded an individual-level percentage score reflecting the relative impact of negative emotions compared to the neutral condition. Separate scores were computed for each trial type (Go, No-Go, Match, Non-Match, Repeated, and Switch). We then conducted Pearson correlation analyses across tasks to assess whether individuals who exhibited stronger emotion-related effects in one task showed similar patterns in the other tasks. Finally, additional repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted on the normalized emotions effect scores to examine systematic differences in the magnitude of emotions effect between tasks and trial types.

3. Results

3.1. Go/No-Go Task

Response times and accuracies were analyzed using a 2 (Emotion: neutral; negative) × 2 (Trial Type: Go; No-Go) repeated-measures ANOVAs. Results are summarized in

Table 1.

3.1.1. Response times

A significant main effect of trial type was observed, F(1,40) = 34.5, p < .001, MSe = 15283, ƞ2p = .46. Participants were slower to respond on correct Go trials than to false positive trials (322 ms vs 302 ms, respectively). Analyses revealed a main effect of Emotion, F(1,40) = 10.00, p = .003, MSe = 3874, ƞ2p=.20 qualified by a significant Emotion × Trial Type interaction, F(1,40) = 5.65, p = .022, MSe = 2302, ƞ²ₚ = .12. Response times for false positive trials were larger under negative emotions (311 ms) compared to neutral emotions (294 ms).

3.1.2. Percentages of Errors

Analysis revealed a significant main effect of Emotion, F(1,40) = 6.08, p = .018, MSe = .01, ƞ²ₚ =.13. Participants made more errors under negative emotions compared to neutral ones (8.35% vs.7.15%). No other main effects or interactions reached significance.

3.1.3. Emotions Effect Scores

Analysis revealed a significant difference effect between correct Go and false positive trials on RTs, F(1,40) = 6.09, p = .018, MSe = .06, ƞ²ₚ = .13. Participants showed a larger emotional effect on false positive trials (+6.54%) compared to correct Go trials (+0.92%). No significant differences in emotions effect came out significant for accuracy.

3.2. Back Task

Participants’ mean latencies and percentages of errors were analyzed with a 2 (Emotion: neutral; negative) × 2 (Trial Type: Match; Non-Match) repeated-measures ANOVAs (see means in

Table 1).

3.2.1. Response Times

A significant main effect of trial type was observed, F(1,40) = 50.5, p < .001, MSe = 121431, ƞ2p = .56. Participants were slower to respond to Non-Match trials (671 ms) compared to Match trials (594 ms) under neutral emotions. This result replicates the classical effect reported in 2-back paradigms (e.g.,Chen et al., 2008; Li et al., 2024).

3.2.2. Percentages of Errors

A main effect of Emotion came out significant, F(1,40) = 9.33, p = .004, MSe = .02, ƞ2p = .20, qualified by a significant Emotion × Trial Type interaction, F(1,40) = 5.25, p = .027, MSe = .01, ƞ2p = .12. Participants made more errors in Non-Match trials under negative emotions (21.6%) than under neutral emotions (18.2%). No significant difference in accuracy was found for Match trials.

3.2.3. Emotions Effect Scores

A significant difference between trial types in percentages of errors was found, F(1,40) = 5.40, p = .025, MSe = .07 ƞ²ₚ = .12. The emotions effect was larger in Non-Match trials (-4.12%) compared to Match trials (-2.13%). No significant emotions effect was observed on RTs.

3.3. Set Switching Task

Participants’ mean latencies and error rates were submitted to a 2 (Emotion: neutral; negative) × 2 (Trial Type: Repeated; Switch) repeated-measures ANOVAs (see means in

Table 1).

3.3.1. Response Time

A significant main effect of trial type was observed, F(1,40) = 8.35, p = .006, MSe = 2102.4, ƞ2p = .17. Participants were slower to respond on Switch trials (614 ms) than on Repeated trials (607 ms). Analyses also revealed a main effect of Emotion, F(1,40) = 6.57, p = .014, MSe = 2049.6, ƞ2p = .14. Participants were faster to respond under negative emotions (607 ms) than under neutral emotions (614 ms). No significant differences in RTs were observed between the neutral and negative emotion conditions, either for Repeated or Switch trials.

3.3.2. Percentages of Errors

The analysis revealed a significant main effect of trial type under neutral emotions, F(1,40) = 10.6, p = .002, MSe = .03, ƞ2p = .21. Participants made more errors in Switch trials (17.00%) compared to repeat trials (13.2%; for same results see Rogers & Monsell, 1995). A significant main effect of Emotion was also observed, F(1,40) = 33.09, p < .001, MSe = .05, ƞ2p = .45, indicating that participants made more errors under negative emotions (22%) than under neutral emotions (15.1%). Planned comparisons revealed that participants made significantly more errors under negative emotions compared to neutral ones in both Switch trials, F(1, 40) = 19.9, p < .001, MSe = .08, ƞ²ₚ = .33, (23.5% vs. 17.0%) and Repeated trials, F(1, 40) = 19.8, p < .001, MSe = .11, ƞ²ₚ = .33 (20.5% vs. 13.2%).

3.3.3. Emotions Effect Scores

No significant differences were found for either RTs or accuracy.

3.4. Cross-Task Correlations of Emotions Effect

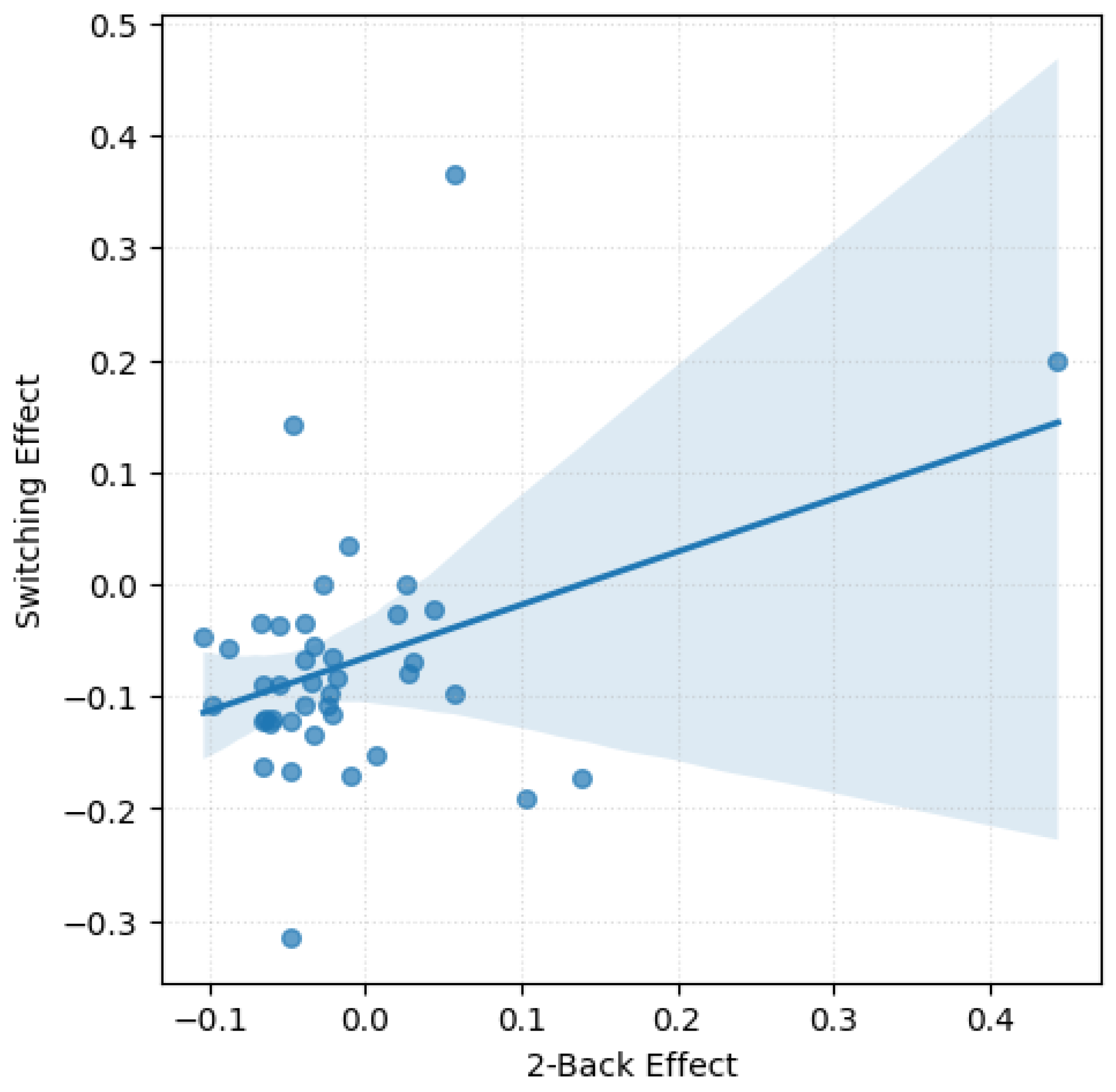

A significant moderate positive correlation emerged between the emotions effect in the 2-back task and the Set-Switching task, r(39) = .38, p = .014 (see

Figure 1). This finding suggests that participants who showed greater emotion-related accuracy impairments in the WM task tended to exhibit similar patterns in the Set-Switching task. No significant correlations were found between the Go/No-Go task and either the 2-back or the Set-Switching task.

No significant correlations were found between emotions effect on RTs across tasks. However, a non-significant trend was observed between switching and 2-back, r(39) = -.30, p = .056, consistent with the task specific analyses, which revealed no significant effect of emotions on RTs for these tasks.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine how negative emotions influence cognitive control performance. Participants completed a Go/No-Go, a 2-back, and a Set-Switching task. Each task was performed under both neutral and negative emotions induced via the presentation of negative and neutral pictures preceding each trial. Our results replicated well-established task-specific effects widely documented in the literature. In the Go/No-Go task, false positive RTs were shorter than correct RTs for Go trials, consistent with previous findings (e.g., Leblanc-Sirois et al., 2018). In the 2-back task, RTs were longer for Non-Match trials compared to Match trials, as previously reported (e.g., Chen et al., 2008; Li et al., 2024). In the set-switching task, the larger percentage of errors in Switch trials compared to repeat trials reflected the expected switching cost typically observed in cognitive flexibility paradigms (e.g., Rogers & Monsell, 1995). Interestingly, our findings revealed that negative emotions impaired performance across all three tasks, although these effects were specific to certain trial types rather than generalized across all trials. Negative emotions modulate executive processes depending on task demands. Surprisingly, in the set-switching task, negative emotions appeared to enhance overall performance, as participants responded faster under negative emotions than under neutral conditions, irrespective of trial type. Although no differences were observed on RTs between Repeated and Switch trials, such a difference emerged for accuracy, indicating that the influence of negative emotions was more pronounced on error rates than on latencies. Interestingly, the emotions effect differed across the three CC tasks. Possibly, negative emotions do not influence all cognitive control processes but rather influence specific mechanisms. Furthermore, the correlation between interference effects in updating and shifting tasks could reflect an overlapping mechanism through which negative emotions influence these components of cognitive control. Taken together, these results offer important insights into the complex interplay between emotion and cognition. By highlighting both global and mechanism-specific effects of emotions on cognitive control, this study contributes to enhance our understanding on how negative emotions influence cognition.

4.1. Effect of Emotions on Inhibition, Updating and Shifting

In the Go/No-Go task, participants were significantly slower on false positive RTs under negative emotions compared to neutral emotions, indicating a slowdown in inhibitory control. This slowing may reflect increased cognitive load or attentional capture by negative stimuli, which, in turn hinders the deployment of inhibitory control processes. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that negative emotions interfere with attentional control and executive monitoring (e.g., Pessoa, 2009; Verbruggen & De Houwer, 2007). The pattern of shorter false positive RTs has been interpreted as reflecting a failure to suppress prepotent responses that have already been initiated (e.g., Leblanc-Sirois et al., 2018). Emotions modulated overall Go/No-Go performance, with a stronger impact observed on false-positive-Go trials, suggesting a differential emotional influence rather than a generalized inhibition deficit. This pattern likely reflects increased interference under high-control demands, where negative emotions compromise the ability to withhold prepotent responses. According to previous findings, emotions do not consistently influence Go trial performance when emotional content is irrelevant to the task (e.g., Mancini et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2014). No-Go trials require top-down control to inhibit dominant responses, making them more sensitive to interference. This interpretation aligns with recent theories suggesting that emotionally irrelevant information selectively disrupts executive processes when cognitive control demands are high (e.g., Grimshaw et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). It is therefore possible that the slowing of false positive RTs under negative emotions reflects increased interference with top-down inhibition, particularly under cognitively demanding conditions. Moreover, participants made more commission errors under negative emotion conditions. Although the interaction between Emotion and Trial Type was not significant for accuracy, the main effect of emotion nonetheless indicates that inhibition performance is modulated by negative emotions. Emotions effect scores on RTs revealed a larger emotional impact on No-Go trials compared to Go trials, reinforcing the idea that inhibitory control is particularly sensitive to negative emotions. Although our findings suggest an effect of negative emotions on Go/No-Go performance, caution is warranted in generalizing this effect to the broader construct of inhibition. The Go/No-Go paradigm primarily targets response inhibition (i.e., the ability to withhold a prepotent motor response), whereas other forms of inhibitory control such as interference control or proactive control (Friedman & Miyake, 2004; Nigg, 2000) are not encompass. Consequently, our results should be interpretated as reflecting emotion-induced changes in motor response inhibition, rather than inhibition more broadly. Future studies could integrate complementary paradigms (e.g., Stroop, Stop-Signal, Antisaccade task) to further dissociate how emotions impact distinct inhibitory subcomponents.

In the 2-back task, participants were slower to respond to Non-Match trials compared to Match trials. This finding replicates the classic updating cost reported in the literature and reflects the increased cognitive demand associated with monitoring and comparing incoming stimuli in WM (e.g., Li et al., 2024). The significant Emotion × Trial Type interaction in the percentages of errors showed that participants made more errors on Non-Match trials in negative emotional conditions, whereas no difference was found for Match trials. Emotions effect scores also confirmed that performance was influenced on Non-Match trials, suggesting that negative emotions impair updating performance specifically when task demands are high. Negative emotions may primarily affect the updating processes involved in integrating new content into working memory, monitoring stimuli presented two items earlier, and suppressing outdated information. This interpretation suggests that negative emotions influence these specific control operations rather than impairing recall accuracy per se. Non-Match trials are inherently more demanding, as they require participants to maintain the stimulus from two trials earlier, actively suppress information that is no longer relevant, and incorporate new input into WM. This interpretation is consistent with prior studies showing that updating is impaired when emotional states compete with task-relevant processing (e.g., Grissmann et al., 2017). The absence of emotions effect on RTs, despite significant accuracy impairments, suggests that negative emotions do not necessarily slow down updating, but rather impair its efficiency and reliability. It is possible that negative emotions interfere with cognitive representations or increase the probability of response conflict, degrading the fidelity of the memory trace rather than slowing its retrieval (Mitchell & Phillips, 2007). These emotions effect may result from a competition for limited-capacity cognitive resources, with emotion processes drawing attention away from ongoing cognitive control processes. Previous hypothesis proposed that emotions processes are prioritized during cognitive processing at the expense of goal-relevant content (Desimone & Duncan, 1995; Pessoa, 2009). Under high cognitive load, such as in Non-Match trials, this prioritization could reduce the availability of attentional and memory resources required for effective WM updating and the suppression of irrelevant information.

In the Set-Switching task, participants made more errors in Switch trials compared to repeat trials under neutral emotional conditions. These results replicate classical findings from the task-switching literature and reflect the greater cognitive demands associated with reconfiguring mental sets (e.g., Rogers & Monsell, 1995). Interestingly, a main effect of Emotion revealed that participants responded faster under negative emotional conditions compared to neutral ones. Although this performance improvement was not predicted, it aligns with previous findings suggesting that negative emotions can heighten arousal or alertness, thereby accelerating responses (e.g., Kuhbandner & Zehetleitner, 2011; Pessoa, 2009). While these faster RTs under negative emotions may suggest improved performance, accuracy rates did not follow the same pattern. Such a dissociation raises the possibility of a speed–accuracy trade-off (Heitz, 2014), whereby participants under negative emotions may adopt a more impulsive response strategy. This shift could reflect a motivational tendency to complete tasks more quickly in order to reduce the negative emotions effect (Pessoa, 2009). In tasks with high executive demands, such as Set-Switching, this tendency may compromise the ability to maintain task goals or to reconfigure mental sets efficiently. One possible explanation is that participants engaged in a less controlled processing mode, marked by reduced top-down regulation and increased cognitive impulsivity. Although participants generally responded faster under negative emotions, further analyses revealed that emotions effect on latency did not emerge, whereas such effects were observed for accuracy. This pattern suggests that negative emotions did not selectively impair shifting performance, but instead produced a global decline in response accuracy, indicative of reduced overall cognitive control efficiency. Similar findings have been reported in the task-switching literature (e.g., Hsieh & Lin, 2019).

Interestingly, the increase in error rates under negative emotions is consistent with models proposing that negative emotions impair goal maintenance. For instance, Kuhbandner and Zehetleitner (2011) suggested that negative emotions increase distractibility, undermining the ability to shield task goals from interference. In the current study, such interference may have globally weakened participants' ability to sustain task-relevant rules, whether shifting was required or not. Thus, negative emotions appear to compromise the goal representations, resulting in increased errors across both Repeated and Switch trials, rather than a specific disruption of executive reconfiguration mechanisms. An alternative but not mutually exclusive explanation is that negative emotions promote a more flexible processing mode. According to Dreisbach & Goschke (2004), two distinct modes of cognitive control can be distinguished: a shielded mode, which favors goal maintenance and resistance to distraction but limits flexibility, and a flexible mode, which facilitates cognitive reconfiguration at the cost of increased distractibility. Here, the increased errors and faster responses observed under negative emotions might reflect a shift toward this more flexible mode, allowing for quicker transitions but with reduced control over interference.

4.2. The Influence of Emotions Across the Three Tasks

One of the main contributions of the present study lies in the within-subject comparison of emotional effects across distinct cognitive control processes. Our results provide original evidence for a potential link between updating and shifting mechanisms under emotional influence. Specifically, a significant moderate positive correlation was observed between the emotions effect on accuracy in the 2-back and Set-Switching tasks. Participants who exhibited greater emotion-related impairments in WM updating also tended to show similar impairments in cognitive flexibility. This finding is particularly noteworthy given the distinct pattern of emotions effect observed for each task. In the 2-back task, negative emotions selectively impaired participants’ ability to discard no-longer-relevant information, evidenced by decreased accuracy in Non-Match trials. In contrast, performance in the Set-Switching task was globally impaired by negative emotions, with a general increase in percentages of errors across both repeat and Switch trials, suggesting an impairment of cognitive control. Despite these differences, the observed correlation implies a shared emotions effect across these processes. One plausible interpretation is that both updating and shifting rely on a common executive operation, such as the suppression of irrelevant mental representations, which may be particularly sensitive to emotions effect. Prior models of executive function (e.g., Friedman & Miyake, 2017) have emphasized the partially independent yet interconnected nature of cognitive control components, supported by domain-general mechanisms. Similarly, hypotheses of cognitive control suggest that processes like interference resolution, attentional allocation, and top-down monitoring play central roles across multiple executive functions (Gratton et al., 2018). The present findings are consistent with the hypothesis that negative emotions disrupt these shared resources, leading to impairments in tasks that require flexible updating and task-set reconfiguration.

An additional interpretation is that a shared mechanism may underlie the influence of negative emotions on both task switching and WM updating specifically, the ability to actively maintain task goals and suppress irrelevant information. Negative emotions are known to receive prioritized processing (Pessoa, 2009), which can lead to stronger interference when cognitive control demands are high. This difficulty in filtering out emotional distractors could explain the observed performance impairments across both trial types in the switching task, as well as the greater error rates on Non-Match trials in the 2-back task, which require the active replacement of outdated information. Furthermore, the observed correlation between emotions effect in the shifting and updating tasks suggests that participants who are more susceptible to emotional interference in one domain may experience similar deficits in the other. These findings support the hypothesis of a general reduction in control efficiency under negative emotions, characterized by impaired goal maintenance and inhibitory filtering of affective interference.

However, no significant correlations were observed between the Go/No-Go task and either the updating or switching tasks. This pattern of results suggests that inhibitory control, as assessed in the present paradigm, is influenced by emotions through more domain-specific or process-specific pathways. One possible explanation is that the type of inhibition required in the Go/No-Go task relies more heavily on automatic, stimulus-driven processes, which are triggered by specific response demands and may be less sensitive to fluctuations in the emotional context across individuals. In contrast, updating and shifting require more sustained and flexible engagement of cognitive resources, making them more vulnerable to emotional interference and to individual differences in emotional reactivity. As such, the absence of cross-task correlations involving the inhibition task may reflect distinct mechanisms by which emotions modulate executive functioning, with inhibition being relatively isolated from the broader, integrative control processes engaged in updating and shifting.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, these cross-task analyses reinforce the idea that emotions effect on cognitive control is not uniform but instead vary depending on the nature of the executive process involved. While inhibitory control appears to operate independently, updating and shifting may share a common emotional influence, especially when cognitive demands involve actively suppressing or replacing irrelevant information. This pattern supports a componential model of executive function, in which distinct yet partially overlapping control mechanisms are differentially influenced by negative emotions.

One limitation of our experiment is that each executive process was assessed using a distinct task. Although this strategy allows for isolating the emotions effect on specific mechanisms, it may also introduce variability due to differences in task structure, difficulty, or emotional sensitivity. This variability may limit the comparability of negative emotions across cognitive control domains. Future research would benefit from developing integrated paradigms in which the three cognitive control mechanisms are assessed within a single, unified task. Such a design would offer a more ecologically valid and dynamic framework to investigate how negative emotions affect executive functions and would allow for fine-grained modeling of emotion–cognition interactions across mechanisms within the same context. It would also help disentangle whether emotional modulation targets distinct control processes independently or results from a more general disruption of top-down regulation under affective load. Another limitation lies in the use of a single task for each cognitive control process. As said below, the Go/No-Go task only allows the investigation of one specific facet of inhibition and may not reflect the influence of emotions on other inhibitory control subcomponents. Thus, while our results indicate emotional modulation of response inhibition, they should not be overgeneralized to the broader domain of inhibitory control. This observation also applies to other cognitive control processes. Indeed, although we deliberately restricted our design to a single cognitive task to assess each process and thereby reduce methodological variability, future research should aim to examine the influence of emotions on other subcomponents of cognitive control.

Taken together, the present findings provide new insights into the differential impact of negative emotions on cognitive control. While negative emotions impaired performance across inhibition, updating, and shifting tasks, the nature and specificity of these effects varied by process. Notably, a significant association between emotion-related impairments in updating and shifting suggests the presence of a shared, emotion-sensitive control mechanism, possibly linked to the suppression of irrelevant information. In contrast, inhibition appeared to be influenced in a more domain-specific manner. These results reinforce the idea that negative emotions do not uniformly influence executive functioning but instead target specific cognitive mechanisms.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the development and the conceptualization of the study. T.F. coded the experiment and analyzed the data. L.F. provided feedback on the data analysis. All authors wrote the first draft of the manuscript, edited it, and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agence de l’Innovation de Défense (AID), grant number 2022-65-0086.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee Comité de protection des personnes Sud-Est IV, Loi Jardé (number 2023- A01670-45).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable contribution of all participants who took part in this study. ChatGPT was employed to provide assistance in translating the manuscript from French to English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVAs |

Analysis of Variance |

| IAPS |

International Affective Picture System |

| MSe |

Mean Square Error |

| ms |

Millisecond(s) |

| RT |

Response Time(s) |

| WM |

Working Memory |

| ƞ2p

|

Partial eta squared |

Appendix

Table A1.

Emotional valence and arousal ratings for each type of trial in the three tasks.

Table A1.

Emotional valence and arousal ratings for each type of trial in the three tasks.

| Elements |

Negative |

Neutral |

F(df1,df2) |

|

| |

Emotional Valence |

|

|

| |

|

F (1,143) |

|

| Go trial (N=144) |

3.28 (1.81 – 4.75; 0.07) |

6.30 (5.35 – 7.18; 0.04) |

10429*** |

|

| No-Go trial (N=48) |

3.21 (1.31 – 4.88; 0.19) |

6.29 (5.22 – 7.32; 0.12) |

1644*** |

|

| F(1,47) |

0.931 (p=.194) |

0.0121 (p=.913) |

|

|

| |

|

F (1,95) |

|

| Non-Match trial (N=96) |

3.23 (1.56 – 4.84; 0.10) |

6.27 (5.24 – 7.27; 0.06) |

3160*** |

| Match trial (N=48) |

3.29 (1.59 – 4.82; 0.16) |

6.31 (5.26 – 7.26; 0.10) |

2477*** |

|

| F(1, 95) |

1.81 (p=.185) |

1.81 (p=.850) |

|

|

| |

F (1,17) |

|

| Repeated trial (N=150) |

3.25 (1.76 – 4.78; 0.07) |

6.29 (5.32 – 7.22; 0.04) |

10178*** |

|

| Switch trial (N=18) |

3.22 (1.67 – 7.81; 0.31) |

6.27 (5.29 – 7.24; 0.19) |

701*** |

|

| F(1, 17) |

0.0227 (p=.882) |

< .001 (p=.985) |

|

|

| |

Arousal Rating |

|

|

| Go trial (N=144) |

5.22 (2.03 – 6.96; 0.08) |

4.81 (2.6 – 6.82; 0.08) |

10.9** |

|

| No-Go trial (N=48) |

5.31 (1.72 – 7.26; 0.19) |

4.34 (2.51 – 6.34; 0.13) |

15.7*** |

|

| F(1, 47) |

0.849 (p=.400) |

3.09 (p=.085) |

|

|

| Non-Match trial (N=96) |

5.19 (2.39 – 7.39; 0.12) |

4.55 (2.74 – 6.66; 0.10) |

13.6*** |

|

| Match trial (N=48) |

3.23 (2.69 – 7.34; 0.19) |

4.39 (2.32 – 7.07; 0.16) |

9.03* |

|

| F(1,47) |

1.83 (p=.183) |

0.033 (p=.885) |

|

| Repeated trial (N=150) |

5.16 (1.74 – 4.78; 0.08) |

4.64 (5.32 – 7.22; 0.08) |

15.4*** |

|

| Switch trial (N=18) |

5.20 (1.67 – 4.81; 0.32) |

4.26 (5.29 – 7.24; 0.23) |

4.42* |

|

| F(1, 17) |

0.485 (p=.496) |

|

0.0216 (p=.885) |

|

|

References

- (Albert et al., 2010) Albert, J., López-Martín, S., & Carretié, L. (2010). Emotional context modulates response inhibition : Neural and behavioral data. NeuroImage, 49(1), 914-921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.045. [CrossRef]

- (Amer et al., 2016) Amer, T., Campbell, K. L., & Hasher, L. (2016). Cognitive Control As a Double-Edged Sword. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(12), 905-915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.002. [CrossRef]

- (Banich et al., 2024) Banich, M. T., Haber, S. N., & Robbins, T. W. (2024). The Frontal Cortex : Organization, Networks, and Function. MIT Press.

- (Blanchette & Caparos, 2013) Blanchette, I., & Caparos, S. (2013). When emotions improve reasoning : The possible roles of relevance and utility. Thinking & Reasoning, 19(3-4), 399-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2013.791642. [CrossRef]

- (Blanchette et al., 2014) Blanchette, I., Gavigan, S., & Johnston, K. (2014). Does emotion help or hinder reasoning? The moderating role of relevance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1049-1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034996. [CrossRef]

- (Buodo et al., 2017) Buodo, G., Sarlo, M., Mento, G., Messerotti Benvenuti, S., & Palomba, D. (2017). Unpleasant stimuli differentially modulate inhibitory processes in an emotional Go/NoGo task : An event-related potential study. Cognition and Emotion, 31(1), 127-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1089842. [CrossRef]

- (Buratto et al., 2014) Buratto, L. G., Pottage, C. L., Brown, C., Morrison, C. M., & Schaefer, A. (2014). The Effects of a Distracting N-Back Task on Recognition Memory Are Reduced by Negative Emotional Intensity. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110211. [CrossRef]

- Caparos, S., & Blanchette, I. (2017). Independent effects of relevance and arousal on deductive reasoning. Cognition and Emotion, 31(5), 1012-1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1179173. [CrossRef]

- (Chen et al., 2008) Chen, Y. N., Mitra, S., & Schlaghecken, F. (2008). Sub-processes of working memory in the N-back task: An investigation using ERPs. Clinical Neurophysiology, 119(7), 1546-1559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.003. [CrossRef]

- (De Houwer & Tibboel, 2010) De Houwer, J., & Tibboel, H. (2010). Stop what you are not doing ! Emotional pictures interfere with the task not to respond. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 17(5), 699-703. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.17.5.699. [CrossRef]

- (Demanet et al., 2011) Demanet, J., Liefooghe, B., & Verbruggen, F. (2011). Valence, Arousal, and Cognitive Control : A Voluntary Task-Switching Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00336. [CrossRef]

- (Desimone & Duncan, 1995) Desimone, R., & Duncan, J. (1995). Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annual review of neuroscience, 18(1), 193-222. [CrossRef]

- (Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004) Dreisbach, G., & Goschke, T. (2004). How Positive Affect Modulates Cognitive Control : Reduced Perseveration at the Cost of Increased Distractibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(2), 343-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.30.2.343. [CrossRef]

- (Dresler et al., 2009) Dresler, T., Mériau, K., Heekeren, H. R., & Meer, E. (2009). Emotional Stroop task : Effect of word arousal and subject anxiety on emotional interference. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 73(3), 364-371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-008-0154-6. [CrossRef]

- (Droit-Volet & Gil, 2009) Droit-Volet, S., & Gil, S. (2009). The time–emotion paradox. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1943-1953. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0013. [CrossRef]

- (Droit-Volet & Meck, 2007) Droit-Volet, S., & Meck, W. H. (2007). How emotions colour our perception of time. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(12), 504-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.008. [CrossRef]

- (Eckart et al., 2013) Eckart, C., Kraft, D., Rademacher, L., & Fiebach, C. J. (2023). Neural correlates of affective task switching and asymmetric affective task switching costs. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 18(1), nsac054. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsac054. [CrossRef]

- (Ellis & Ashbrook, 1989) Ellis, H. C., & Ashbrook, P. W. (1989). The" state" of mood and memory research: A selective review. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 4(2), 1.

- (Ellis & Moore, 1999) Ellis, H. C., & Moore, B. A. (1999). Mood and memory. Handbook of cognition and emotion, 193-210.

- (Fabre & Lemaire, 2019) Fabre, L., & Lemaire, P. (2019). How Emotions Modulate Arithmetic Performance : A Study in Arithmetic Problem Verification Tasks. Experimental Psychology, 66(5), 368-376. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000460. [CrossRef]

- (Friedman & Miyake, 2017) Friedman, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2017). Unity and diversity of executive functions : Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex, 86, 186-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.023. [CrossRef]

- (Friedman et al., 2008) Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(2), 201-225. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201. [CrossRef]

- (Gil & Droit-Volet, 2011) Gil, S., & Droit-Volet, S. (2011). “Time flies in the presence of angry faces”… depending on the temporal task used! Acta Psychologica, 136(3), 354-362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.12.010. [CrossRef]

- (Gratton et al., 2018) Gratton, G., Cooper, P., Fabiani, M., Carter, C. S., & Karayanidis, F. (2018). Dynamics of cognitive control : Theoretical bases, paradigms, and a view for the future. Psychophysiology, 55(3), e13016. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13016. [CrossRef]

- (Grimshaw et al., 2018) Grimshaw, G. M., Kranz, L. S., Carmel, D., Moody, R. E., & Devue, C. (2018). Contrasting reactive and proactive control of emotional distraction. Emotion, 18(1), 26. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/emo0000337. [CrossRef]

- (Grissmann et al., 2017) Grissmann, S., Faller, J., Scharinger, C., Spüler, M., & Gerjets, P. (2017). Electroencephalography Based Analysis of Working Memory Load and Affective Valence in an N-back Task with Emotional Stimuli. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 616. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00616. [CrossRef]

- (Hare et al., 2005) Hare, T. A., Tottenham, N., Davidson, M. C., Glover, G. H., & Casey, B. J. (2005). Contributions of amygdala and striatal activity in emotion regulation. Biological Psychiatry, 57(6), 624-632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.038. [CrossRef]

- (Heitz, 2014) Heitz, R. P. (2014). The speed-accuracy tradeoff : History, physiology, methodology, and behavior. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00150. [CrossRef]

- (Hommel et al., 2002) Hommel, B., Ridderinkhof, R., & Theeuwes, J. (2002). Cognitive control of attention and action : Issues and trends. Psychological Research, 66(4), 215-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-002-0096-3. [CrossRef]

- (Hsieh & Lin, 2019) Hsieh, S., & Lin, S. J. (2019). The Dissociable Effects of Induced Positive and Negative Moods on Cognitive Flexibility. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37683-4. [CrossRef]

- (Kalanthroff et al., 2016) Kalanthroff, E., Henik, A., Derakshan, N., & Usher, M. (2016). Anxiety, emotional distraction, and attentional control in the Stroop task. Emotion, 16(3), 293-300. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000129. [CrossRef]

- (Keefe et al., 2019) Keefe, J. M., Sy, J. L., Tong, F., & Zald, D. H. (2019). The emotional attentional blink is robust to divided attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81(1), 205-216. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-018-1601-0. [CrossRef]

- (Kopf et al., 2013) Kopf, J., Dresler, T., Reicherts, P., Herrmann, M. J., & Reif, A. (2013). The Effect of Emotional Content on Brain Activation and the Late Positive Potential in a Word n-back Task. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e75598. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075598. [CrossRef]

- (Kraft et al., 2020) Kraft, D., Rademacher, L., Eckart, C., & Fiebach, C. J. (2020). Cognitive, Affective, and Feedback-Based Flexibility – Disentangling Shared and Different Aspects of Three Facets of Psychological Flexibility. Journal of Cognition, 3(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.120. [CrossRef]

- (Krompinger & Simons, 2009) Krompinger, J. W., & Simons, R. F. (2009). Electrophysiological indicators of emotion processing biases in depressed undergraduates. Biological Psychology, 81(3), 153-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.03.007. [CrossRef]

- (Kuhbandner & Zehetleitner, 2011) Kuhbandner, C., & Zehetleitner, M. (2011). Dissociable Effects of Valence and Arousal in Adaptive Executive Control. PLoS ONE, 6(12), e29287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029287. [CrossRef]

- (Ladouceur et al., 2009) Ladouceur, C. D., Silk, J. S., Dahl, R. E., Ostapenko, L., Kronhaus, D. M., & Phillips, M. L. (2009). Fearful faces influence attentional control processes in anxious youth and adults. Emotion, 9(6), 855-864. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017747. [CrossRef]

- (Lang et al., 1999) Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B., N. (1999). International affective picture system (IAPS) : Instruction manual and affective ratings.

- (Leblanc-Sirois et al., 2018) Leblanc-Sirois, Y., Braun, C. M. J., & Elie-Fortier, J. (2018). Reaction Time of Erroneous Responses in the Go/No-Go Paradigm : Effects of Go Trial Probability and Memory Demand. Experimental Psychology, 65(5), 314-321. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000415. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, P. (2021). Émotion et cognition. De Boeck supérieur.

- (Levens & Gotlib, 2010) Levens, S. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Updating positive and negative stimuli in working memory in depression. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(4), 654-664. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020283. [CrossRef]

- (Li et al., 2024) Li, H., Feng, J., Shi, X., & Zhao, X. (2024). Neural mechanisms of Chinese character recognition, updating, and maintenance in the N-back task. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 200, 112356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2024.112356. [CrossRef]

- (Mancini et al., 2020) Mancini, C., Falciati, L., Maioli, C., & Mirabella, G. (2020). Threatening Facial Expressions Impact Goal-Directed Actions Only if Task-Relevant. Brain Sciences, 10(11), 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10110794. [CrossRef]

- (Melani et al., 2025) Melani, P., Fabre, L., & Lemaire, P. (2025). How negative emotions influence arithmetic problem-solving processes : An ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 211, 109132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2025.109132. [CrossRef]

- (Mitchell & Phillips, 2007) Mitchell, R. L. C., & Phillips, L. H. (2007). The psychological, neurochemical and functional neuroanatomical mediators of the effects of positive and negative mood on executive functions. Neuropsychologia, 45(4), 617-629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.06.030. [CrossRef]

- (Miyake et al., 2000) Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks : A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49-100. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [CrossRef]

- (Murphy et al., 2020) Murphy, J., Devue, C., Corballis, P. M., & Grimshaw, G. M. (2020). Proactive control of emotional distraction: evidence from EEG alpha suppression. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00318. [CrossRef]

- (Myruski et al., 2017) Myruski, S., Bonanno, G. A., Gulyayeva, O., Egan, L. J., & Dennis-Tiwary, T. A. (2017). Neurocognitive assessment of emotional context sensitivity. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 17(5), 1058-1071. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-017-0533-9. [CrossRef]

- (Ocklenburg et al., 2017) Ocklenburg, S., Peterburs, J., Mertzen, J., Schmitz, J., Güntürkün, O., & Grimshaw, G. (2017). Effects of Emotional Valence on Hemispheric Asymmetries in Response Inhibition. Symmetry, 9(8), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym9080145. [CrossRef]

- (Okon-Singer et al., 2015) Okon-Singer, H., Hendler, T., Pessoa, L., & Shackman, A. J. (2015). The neurobiology of emotion-cognition interactions : Fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058. [CrossRef]

- (Ozawa et al., 2014) Ozawa, S., Matsuda, G., & Hiraki, K. (2014). Negative emotion modulates prefrontal cortex activity during a working memory task : A NIRS study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00046. [CrossRef]

- (Padmala et al., 2011) Padmala, S., Bauer, A., & Pessoa, L. (2011). Negative Emotion Impairs Conflict-Driven Executive Control. Frontiers in Psychology, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00192. [CrossRef]

- (Peirce et al., 2019) Peirce, J., Gray, J. R., Simpson, S., MacAskill, M., Höchenberger, R., Sogo, H., Kastman, E., & Lindeløv, J. K. (2019). PsychoPy2 : Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 195-203. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y. [CrossRef]

- (Pessoa et al., 2009) Pessoa, L. (2009). How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 160-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.006. [CrossRef]

- (Phelps et al., 2006) Phelps, E. A., Ling, S., & Carrasco, M. (2006). Emotion Facilitates Perception and Potentiates the Perceptual Benefits of Attention. Psychological Science, 17(4), 292-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01701.x. [CrossRef]

- (Pratto & John, 1991) Pratto, F., & John, O. P. (1991). Automatic vigilance : The attention-grabbing power of negative social information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 380-391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.380. [CrossRef]

- (Reeck & Egner, 2015) Reeck, C., & Egner, T. (2015). Emotional task management : Neural correlates of switching between affective and non-affective task-sets. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(8), 1045-1053. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu153. [CrossRef]

- (Robinson et al., 2013a) Robinson, M. D., Watkins, E., & Harmon-Jones, E. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of cognition and emotion. The Guilford Press.

- (Robinson et al., 2013b) Robinson, O. J., Krimsky, M., & Grillon, C. (2013). The impact of induced anxiety on response inhibition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00069. [CrossRef]

- (Rogers & Monsell, 1995) Rogers, R. D., & Monsell, S. (1995). Costs of a predictible switch between simple cognitive tasks. Journal of experimental psychology: General, 124(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.124.2.207. [CrossRef]

- (Schulz et al., 2007) Schulz, K., Fan, J., Magidina, O., Marks, D., Hahn, B., & Halperin, J. (2007). Does the emotional go/no-go task really measure behavioral inhibition?Convergence with measures on a non-emotional analog. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(2), 151-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.12.001. [CrossRef]

- (Stockdale et al., 2020) Stockdale, L. A., Morrison, R. G., & Silton, R. L. (2020). The influence of stimulus valence on perceptual processing of facial expressions and subsequent response inhibition. Psychophysiology, 57(2), e13467. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13467. [CrossRef]

- (Thompson et al., 2022) Thompson, N. M., Van Reekum, C. M., & Chakrabarti, B. (2022). Cognitive and Affective Empathy Relate Differentially to Emotion Regulation. Affective Science, 3(1), 118-134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-021-00062-w. [CrossRef]

- (Van Wouve et al., 2011) Van Wouwe, N. C., Band, G. P. H., & Ridderinkhof, K. R. (2011). Positive Affect Modulates Flexibility and Evaluative Control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(3), 524-539. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21380. [CrossRef]

- (Verbruggen & De Houwer, 2007) Verbruggen, F., & De Houwer, J. (2007). Do emotional stimuli interfere with response inhibition? Evidence from the stop signal paradigm. Cognition & Emotion, 21(2), 391-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600625081. [CrossRef]

- (Wang et al., 2017) Wang, Y., Chen, J., & Yue, Z. (2017). Positive Emotion Facilitates Cognitive Flexibility : An fMRI Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01832. [CrossRef]

- (Yiend et al., 2013) Yiend, J., Barnicot, K., & Koster, E. (2013). Attention and Emotion.

- (Yu et al., 2014) Yu, F., Ye, R., Sun, S., Carretié, L., Zhang, L., Dong, Y., Zhu, C., Luo, Y., & Wang, K. (2014). Dissociation of Neural Substrates of Response Inhibition to Negative Information between Implicit and Explicit Facial Go/Nogo Tasks : Evidence from an Electrophysiological Study. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e109839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109839. [CrossRef]

- (Zhang et al., 2023) Zhang, J., Bürkner, P.-C., Kiesel, A., & Dignath, D. (2023). How emotional stimuli modulate cognitive control : A meta-analytic review of studies with conflict tasks. Psychological Bulletin, 149(1-2), 25-66. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000389. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).