Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Applications and Case Examples:

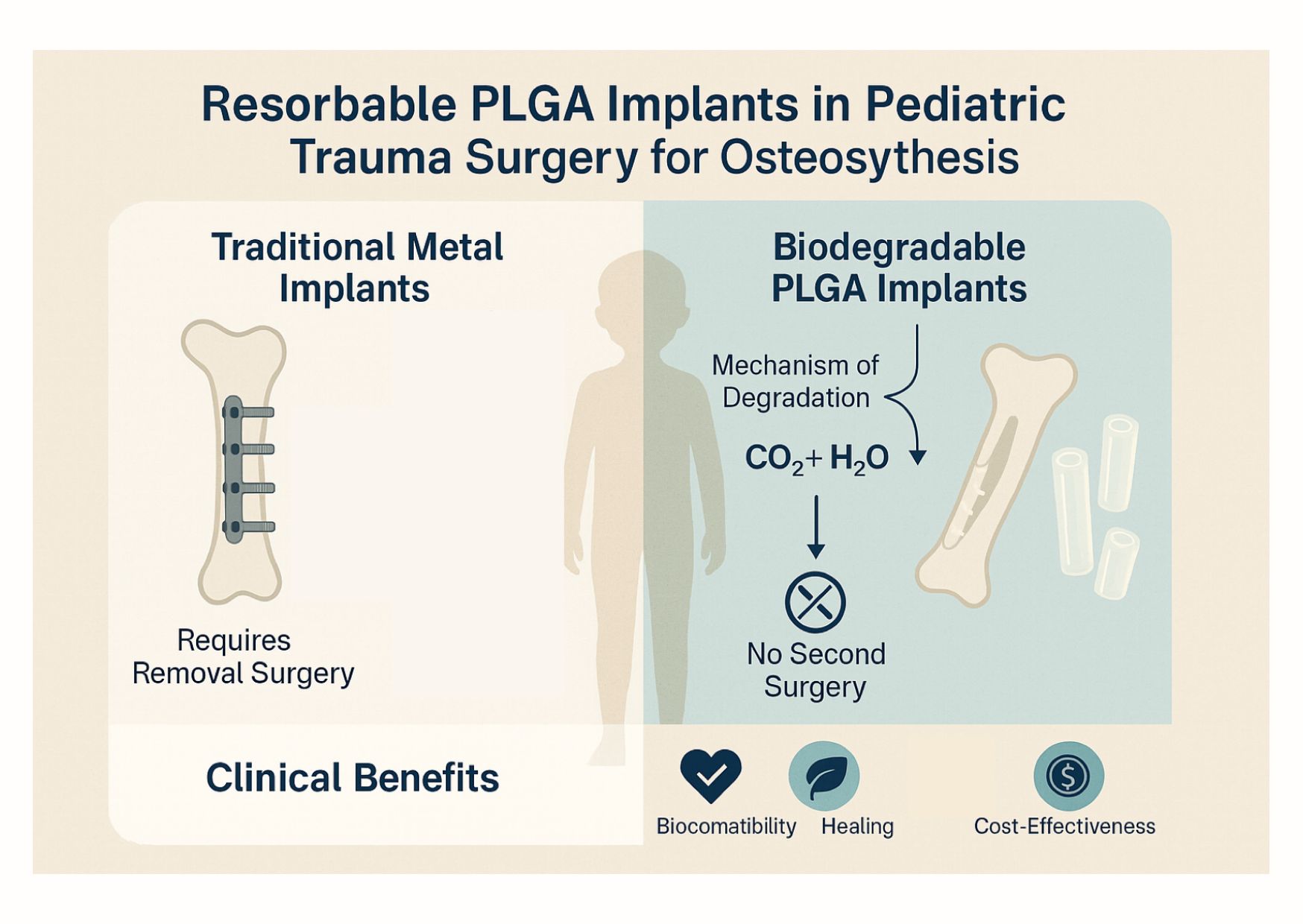

- Forearm Fractures: One of the most common fracture sites in the pediatric population. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN) with metal rods is a standard treatment for unstable diaphyseal forearm fractures. However, nowadays, instead of metal rods, bioabsorbable IM-nails made of PLGA are an alternative solution. In a 2024 cohort study of 38 children, all patients achieved bone union with stable alignment [23]. At one-year follow-up, the children showed nearly full recovery of their range of motion (ROM); minor reductions in forearm rotation and elbow flexion were not clinically significant. Complications such as refractures or irritation were not reported. The efficacy of the minimally invasive approach was reflected by excellent scar assessment scores. Another study, composed of 161 patients, emphasised the significance of surgical technique in order to evade complications [24]. In the literature, several other papers can be found that confirm that RIN is a safe and effective method for internal fixation of the forearm fractures, which produces results that are comparable to traditional metal implants [19,25,26,27].

- Distal Radius Fractures: Generally, injuries affecting the wrists are managed with percutaneous K-wire fixation. Modern alternatives include biodegradable pins and short IM-nails. In 2022, a multicenter retrospective study compared outcomes in children with severely displaced distal radius/forearm fractures treated with either standard K-wires or bioresorbable PLGA pins [28]. The findings were instructive: the group treated with biodegradable pins had significantly lower complication rates than those treated with buried or exposed K-wires. Specifically, the PLGA implants avoided typical K-wire problems such as pin track infections or irritation [28]. By six weeks to six months post-injury, all groups had similar alignment and functional outcomes, but the children with absorbable implants were spared the anxiety and discomfort of wire removal. After 1.5 years of follow-up, there were no growth disturbances observed in any patients, indicating that neither the biodegradable implants nor the K-wires affected the physes negatively [28]. [28]

- Ankle (Physeal) Fractures: Fractures of the distal tibia involving the growth plate (Salter-Harris fractures) are another scenario where implant choice is critical. Metal screws across a growth plate must be removed promptly to avoid growth arrest. In a retrospective study of 128 pediatric ankle fractures compared PLGA absorbable screws were compared to standard metallic screws for fixing physeal fractures (mainly Salter-Harris II, III, IV of the distal tibia) [29,30]. The study noted that the PLGA implants achieved comparable fracture stability and healing as metal screws, but without necessitating implant removal [30]. In the literature, similar results are reported through randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews [22,29,31,32,33]

- Elbow Fractures: Injuries of the lateral humeral condyles are the second most common elbow fractures in children, which often require operative solutions. Traditionally, management includes K-wires or screws, but as of late, biodegradable pins offer an alternate solution. The outcomes of biodegradable pins versus K-wires were examined by Li et al. and were found to be safe and effective, with no significant differences in union rates or functional scores [34]. The pins yielded satisfactory fracture stability and healing, comparable to the standard wires [35].

- Other Applications: IM-nails were used with success for the fixation of the clavicle [36]. Osteochondral fractures of the patella, as well as femoral condylar fractures, which affect the articular surfaces, were treated with resorbable nails, pins, and screws [37,38,39]. Implants have also been used in other pediatric orthopaedic scenarios, including fractures of the radial neck, tibial eminence avulsion fractures, osteotomies for deformity correction, and even spinal deformity surgery in experimental settings. [15,40,41,42]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PGA | Polyglycolic Acid |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| K-wire | Kirschner |

| ESIN | Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing |

| RIN | Resorbable Intramedullary Nailing |

| RCT | Randomised Controlled Trials |

| Mg | Magnesium |

References

- Ergun-Longmire, B.; Wajnrajch, M.P. Growth and Growth Disorders. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., Kalra, S., Kaltsas, G., Kapoor, N., Koch, C., Kopp, P., Korbonits, M., Kovacs, C.S., Kuohung, W., Laferrère, B., Levy, M., McGee, E.A., McLachlan, R., Muzumdar, R., Purnell, J., Rey, R., Sahay, R., Shah, A.S., Singer, F., Sperling, M.A., Stratakis, C.A., Trence, D.L., Wilson, D.P., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000.

- Kamel-ElSayed, S.A.; Nezwek, T.A.; Varacallo, M.A. Bone. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sananta, P.; Lesmana, A.; Alwy Sugiarto, M. Growth Plate Injury in Children: Review of Literature on PubMed. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 11, 22799036221104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, H. Bioabsorbable Screws for Pelvic Osteotomies in Children.

- Baldini, M.; Coppa, V.; Falcioni, D.; Cusano, G.; Massetti, D.; Marinelli, M.; Gigante, A.P. Resorbable Magnesium Screws for Fixation of Medial Epicondyle Avulsion Fractures in Skeletally Immature Patients: A Comparison with Kirschner Wires. J. Child. Orthop. 2022, 16, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Carmagnola, I.; Hatton, P.V. An Overview of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid (PLGA)-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3640–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Carmagnola, I.; Hatton, P.V. An Overview of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid (PLGA)-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3640–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, J.; Lin, Y. Application of 3D-Printed, PLGA-Based Scaffolds in Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tian, Y. Biomechanical Evaluation of Novel 3D-Printed Magnesium Alloy Scaffolds for Treating Proximal Humerus Fractures with Medial Column Instability. Injury 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağırdil, Y. The Growth Plate: A Physiologic Overview. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdan, F.; Szumiło, J.; Korobowicz, A.; Farooquee, R.; Patel, S.; Patel, A.; Dave, A.; Szumiło, M.; Solecki, M.; Klepacz, R.; et al. Morphology and Physiology of the Epiphyseal Growth Plate. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2009, 47, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dl, H.; Np, H.; J, S.; P, M.; R, M.; B, H. AO Philosophy and Principles of Fracture Management-Its Evolution and Evaluation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003, 85, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, S. AO Principles of Fracture Management. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2009, 91, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Garg, V.; Parikh, S.N. Management of Physeal Fractures: A Review Article. Indian J. Orthop. 2021, 55, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banothu, D.; Kumar, P.; Ali, S.G.M.; Reddy, R.; Gobinath, R.; Dhanapalan, S. Design, Fabrication, and in Vitro Evaluation of a 3D Printed, Bio-Absorbable PLA Tibia Bone Implant with a Novel Lattice Structure. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.V.; Gonçalves, V.; da Silva, M.C.; Bañobre-López, M.; Gallo, J. PLGA-Based Composites for Various Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landes, C.A.; Ballon, A.; Roth, C. In-Patient versus in Vitro Degradation of P(L/DL)LA and PLGA. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2006, 76, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitepapers - Bioretec Ltd. Available online: https://bioretec.com/educational-materials/whitepapers?medical_professional=on&category=12 (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Perhomaa, M.; Pokka, T.; Korhonen, L.; Kyrö, A.; Niinimäki, J.; Serlo, W.; Sinikumpu, J.-J. Randomized Controlled Trial of the Clinical Recovery and Biodegradation of Polylactide-Co-Glycolide Implants Used in the Intramedullary Nailing of Children’s Forearm Shaft Fractures with at Least Four Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, H.; Hebelka, H.; Brisby, H.; Laine, T. MRI Evaluation of Resorbable Poly Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) Screws Used in Pelvic Osteotomies in Children—a Retrospective Case Series. J. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 15, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix Lanao, R.P.; Jonker, A.M.; Wolke, J.G.C.; Jansen, J.A.; van Hest, J.C.M.; Leeuwenburgh, S.C.G. Physicochemical Properties and Applications of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) for Use in Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Curnutte, B.; Pan, K.; Liu, J.; Ebraheim, N.A. Biomechanical Comparison of Suture-Button, Bioabsorbable Screw, and Metal Screw for Ankle Syndesmotic Repair: A Meta-Analysis. Foot Ankle Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021, 27, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, A.; Lengyel, Á.M.; Kedves, A.; Nudelman, H.; Józsa, G. Pediatric Diaphyseal Forearm Fracture Management with Biodegradable Poly-L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide (PLGA) Intramedullary Implants: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perhomaa, M.; Pokka, T.; Korhonen, L.; Kyrö, A.; Niinimäki, J.; Serlo, W.; Sinikumpu, J.-J. Randomized Controlled Trial of the Clinical Recovery and Biodegradation of Polylactide-Co-Glycolide Implants Used in the Intramedullary Nailing of Children’s Forearm Shaft Fractures with at Least Four Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastwood, F.; Raheman, F.; Al-Dairy, G.; Popescu, M.; Henney, C.; Hunwick, L.; Buddhdev, P. Healing Smarter: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Bioresorbable Implants for Paediatric Forearm Fractures. J. Child. Orthop. 2025, 19, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, C.; Alves, C.; Balslev-Clausen, A.; Canavese, F.; Gercek, E.; Kassai, T.; Klestil, T.; Klingenberg, L.; Lutz, N.; Varga, M.; et al. Pilot Study and Preliminary Results of Biodegradable Intramedullary Nailing of Forearm Fractures in Children. Child. Basel Switz. 2022, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, L.; Perhomaa, M.; Kyrö, A.; Pokka, T.; Serlo, W.; Merikanto, J.; Sinikumpu, J.-J. Intramedullary Nailing of Forearm Shaft Fractures by Biodegradable Compared with Titanium Nails: Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial in Children with at Least Two Years of Follow-Up. Biomaterials 2018, 185, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, M.; Józsa, G.; Hanna, D.; Tóth, M.; Hajnal, B.; Krupa, Z.; Kassai, T. Bioresorbable Implants vs. Kirschner-Wires in the Treatment of Severely Displaced Distal Paediatric Radius and Forearm Fractures - a Retrospective Multicentre Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.H.; Roh, Y.H.; Yang, B.G.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, M.K. Outcomes of Operative Treatment of Unstable Ankle Fractures: A Comparison of Metallic and Biodegradable Implants. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2012, 94, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, H.; Lőrincz, A.; Lamberti, A.G.; Varga, M.; Kassai, T.; Józsa, G. Management of Pediatric Ankle Fractures: Comparison of Biodegradable PLGA Implants with Traditional Metal Screws. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1410750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Eng, D.M.; Schep, N.W.L.; Schepers, T. Bioabsorbable Versus Metallic Screw Fixation for Tibiofibular Syndesmotic Ruptures: A Meta-Analysis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Foot Ankle Surg. 2015, 54, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangdal, S.; Singh, D.; Joshi, N.; Soni, A.; Sament, R. Functional Outcome of Ankle Fracture Patients Treated with Biodegradable Implants. Foot Ankle Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012, 18, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Yu, A.-X.; Guo, X.-P.; Qi, B.-W.; Zhou, M.; Wang, W.-Y. Absorbable Implants versus Metal Implants for the Treatment of Ankle Fractures: A Meta-Analysis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, E.M.; Mattar, L.T.; Newell, B.W.; Coutinho, D.V.; Kaufmann, R.A.; Baratz, M.E.; Debski, R.E. Do Intramedullary Screws Provide Adequate Fixation for Humeral and Ulnar Components in Total Elbow Arthroplasty? A Cadaveric Analysis. J. Hand Surg. 2025, 50, 239.e1–239.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helling, H.-J.; Prokop, A.; Schmid, H.U.; Nagel, M.; Lilienthal, J.; Rehm, K.E. Biodegradable Implants versus Standard Metal Fixation for Displaced Radial Head Fractures. A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Study. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006, 15, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, E.J.; Farnsworth, C.L.; Doan, J.D.; Edmonds, E.W. Bioabsorbable Plating in the Treatment of Pediatric Clavicle Fractures: A Biomechanical and Clinical Analysis. Clin. Biomech. Bristol Avon 2018, 55, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiokas, A.; Morassi, L.G.; Kohl, S.; Zampakides, C.; Megremis, P.; Evangelopoulos, D.S. Bioabsorbable Pins for Treatment of Osteochondral Fractures of the Knee after Acute Patella Dislocation in Children and Young Adolescents. Adv. Orthop. 2012, 2012, e249687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Han, P.-F.; Chen, T.-Y.; Li, P.-C.; Wei, X.-C. [Meta-analysis of clinical effects between non-metallic materials and metallic materials by internal fixation for patellar fracture]. Zhongguo Gu Shang China J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2018, 31, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarda, L.; Morello, S.; Balistreri, F.; D’Arienzo, A.; D’Arienzo, M. Non-Metallic Implant for Patellar Fracture Fixation: A Systematic Review. Injury 2016, 47, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Xie, K.; Cao, S.; Wen, J.; Wang, S.; Xiao, S. Midterm Comparative Result of Absorbable Screws and Metal Screws in Pediatric Medial Humeral Epicondyle Fracture. J. Orthop. Sci. 2025, 30, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Oh, M.J.; Park, M.S.; Sung, K.H. Comparison of Surgical Outcomes between Bioabsorbable and Metal Screw Fixation for Distal Tibial Physeal Fracture in Children and Adolescent. Int. Orthop. 2024, 48, 2681–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, D.; Feng, W.; Song, B.; Wang, Q. Comparison of Bioabsorbable Screw versus Metallic Screw Fixation for Tibial Tubercle Fractures in Adolescents: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heye, P.; Matissek, C.; Seidl, C.; Varga, M.; Kassai, T.; Jozsa, G.; Krebs, T. Making Hardware Removal Unnecessary by Using Resorbable Implants for Osteosynthesis in Children. Children 2022, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmowafy, E.M.; Tiboni, M.; Soliman, M.E. Biocompatibility, Biodegradation and Biomedical Applications of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Micro and Nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Investig. 2019, 49, 347–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Coppa, V.; Falcioni, D.; Senigagliesi, E.; Marinelli, M.; Gigante, A.P. Use of Resorbable Magnesium Screws in Children: Systematic Review of the Literature and Short-Term Follow-Up From Our Series. J. Child. Orthop. 2022, 16, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, F.A.; Spenciner, D.B.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Miller, L.E. Biocomposite Implants Composed of Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)/β-Tricalcium Phosphate: Systematic Review of Imaging, Complication, and Performance Outcomes. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 2017, 33, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, H.; Larnert, P.; Antonsson, P.; Lagerstrand, K.; Brisby, H.; Hebelka, H.; Laine, T. Stability in Pelvic Triple Osteotomies in Children Using Resorbable PLGA Screws for Fixation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2021, 41, e787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, S.; Vakili-Tahami, F.; Chakherlou, T.N. Comparing the Performance of a Femoral Shaft Fracture Fixation Using Implants with Biodegradable and Non-Biodegradable Materials. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Carmagnola, I.; Hatton, P.V. An Overview of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid (PLGA)-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3640–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutilainen, T.; Pätiälä, H.; Ruuskanen, M.; Rokkanen, P. Comparison of Costs in Ankle Fractures Treated with Absorbable or Metallic Fixation Devices. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1997, 116, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bakelen, N.B.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Buijs, G.J.; Jansma, J.; de Visscher, J.G. a. M.; Hoppenreijs, T.J.M.; Bergsma, J.E.; Stegenga, B.; Bos, R.R.M. Cost-Effectiveness of a Biodegradable Compared to a Titanium Fixation System in Maxillofacial Surgery: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. PloS One 2015, 10, e0130330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahemad, D.A.Z.; Rattan, P.D.V.; Jolly, D.S.S.; Kalra, P.D.P.; Sharma, D.S. Biomechanical Comparison of Magnesium Bioresorbable and Titanium Lag Screws for Mandibular Symphysis Fracture Fixation: A Finite Element Analysis. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, K.; Yugami, M.; Karata, S.; Karasugi, T.; Uehara, Y.; Masuda, T.; Nakamura, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Hisanaga, S.; Sugimoto, K.; et al. Plates Made from Magnesium Alloy with a Long Period Stacking Ordered Structure Promote Bone Formation in a Rabbit Fracture Model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workie, A.B.; Shih, S.-J. A Study of Bioactive Glass-Ceramic’s Mechanical Properties, Apatite Formation, and Medical Applications. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23143–23152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunello, G.; Elsayed, H.; Biasetto, L. Bioactive Glass and Silicate-Based Ceramic Coatings on Metallic Implants: Open Challenge or Outdated Topic? Mater. Basel Switz. 2019, 12, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshimaysawee, S.; Fadhel Obaid, R.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Alexis Ramírez-Coronel, A.; Bathaei, M.S. Recent Advancements in Metallic Drug-Eluting Implants. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Srivastava, A.; Bhati, P.; Chaturvedi, M.; Patil, V.; Kunnoth, S.; Kumari, N.; Arya, V.; Pandya, M.; Agarwal, M.; et al. Enhanced Osseointegration of Drug Eluting Nanotubular Dental Implants: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhardi, V.J.; Bichara, D.A.; Kwok, S.; Freiberg, A.A.; Rubash, H.; Malchau, H.; Yun, S.H.; Muratoglu, O.K.; Oral, E. A Fully Functional Drug-Eluting Joint Implant. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D.H.; Tappa, K.; Boyer, C.J.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Hemmanur, K.; Weisman, J.A.; Alexander, J.S.; Mills, D.K.; Woodard, P.K. Antibiotics in 3D-Printed Implants, Instruments and Materials: Benefits, Challenges and Future Directions. J. 3D Print. Med. 2019, 3, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G. A Review of 3D Printed Bone Implants. Micromachines 2022, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicum, A.; Hothi, H.; Henckel, J.; di Laura, A.; Schlueter-Brust, K.; Hart, A. Characterisation of 3D-Printed Acetabular Hip Implants. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, U.; Terner, B.; Karim, M.A.; Ebied, A.; Polkowski, G.G.; Schwarzkopf, R. Total Hip Arthroplasty in Challenging Settings: Acetabular Fractures, Adolescents, Conversions, and Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. J. Arthroplasty 2025, 40, S49–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).