1. Introduction

Long-term conservation tillage (LTCT) is a practice that enhances soil productivity by increasing soil organic matter and mitigating soil loss due to erosion [1]. Nevertheless, LTCT practices have been reported to impede soil warming in cold regions and temperate zones during the early growing season [2]. The application of plastic film mulching (PFM) has been widely adopted as an agricultural practice to increase crop productivity by modifying soil microclimatic conditions, particularly in regions with challenging environmental conditions. In the North China Plain (NCP), where winter temperatures can be severe, PFM has been increasingly utilized during the overwintering period to protect crops and improve soil thermal properties [3]. The NCP, a major agricultural region, experiences cold and dry winters, hindering crop development and reducing yields. With increasing soil temperature, PFM helps extend the growing season, promote root activity, and increase nutrient uptake during the overwintering period [4,61].

LTCT practices, especially NT (no-tillage), are known to increase the structure and content of organic matter in the soil and play a crucial role in reducing erosion; however, these practices often face challenges related to soil temperature regulation and weed control [5]. Regarding tilled systems, PFM has been shown to significantly raise soil temperature, and moisture retention within the soil profile is a vital factor for both agricultural productivity and environmental sustainability, as it promotes early crop emergence and root development [4]. In contrast, NT systems minimize soil disturbance, preserve soil organic carbon, and enhance water infiltration, but often result in cooler soils during the primary growth stages (tillering to stem elongation), which can delay crop establishment [6]. PFM can address this issue by warming the soil, creating a more favorable environment for seed germination and improved root growth, thus boosting the overall performance of NT systems. Researchers have shown that PFM can significantly increase soil temperature by 2–5 °C compared to unmulched fields, depending on the soil type, film color, and thickness [7]. This thermal regulation is especially beneficial for early seedling development and root formation, which are critical for crop resilience in low-temperature conditions.

Soil temperature (ST) is a critical factor influencing crop root system architecture (CRSA), which plays a critical role in determining plant growth, nutrient uptake, and overall production. In the NCP, where winter temperatures often drop below optimal levels for crop development, maintaining adequate soil warmth during the overwintering period is essential for sustaining root activity and ensuring crop survival. The relationship between soil temperature and CRSA is well established, with warmer soils promoting root elongation, branching, and biomass accumulation [8]. For example, studies on winter wheat have confirmed that mulched soils, which are 2–5 °C warmer than unmulched soils, exhibit significantly greater root length density and deeper root penetration, particularly during the overwintering period. These adaptations are crucial for crop resilience in cold environments, as they improve water and nutrient acquisition and support post-dormancy recovery [9]. Moreover, the thermal regulation provided by PFM not only enhances root growth but also influences the spatial spread of roots within the soil profile. This deeper rooting pattern helps crops access subsoil water reserves, thereby improving drought tolerance and yield stability. However, the long-term impacts of PFM on soil health and root development, such as potential root restriction due to plastic residues, warrant further investigation [10].

Eliminating transparent films after the stem elongation stage can increase corn yields [11]. Compared with colorless films (transparent), plastic films (FPs), which are black, might have less potential to increase soil temperatures owing to their low brightness absorbency and modest allowance via luminous heat [12]. However, some studies have shown that black plastic film can decrease soil mineralization, and the influence of temperature on the consistency of soil nutrients has been documented in various studies [13], as has the manipulation of weeds [14,15] compared with transparent or white plastic films. On the other hand, in contrast to white films, the black color of plastic films results in greater corn production [16,17], but the opposite results have also been detected, with no variations in either black or white films ([17].

Long-term (17 years) research revealed an explicit association between increasing temperature before anthesis and spring wheat yield. Additionally, higher temperatures throughout seedling-to-stem elongation (jointing) greatly promoted the ending of yield, owing to increased spike development [18]. Long-term conservation tillage practices influence soil structure, nutrient distribution, and crop productivity in the North China Plain, with no-till (NC) systems often showing lower winter wheat yields than moldboard-based conservation tillage (MC) [19–21]. These yield penalties are linked to cooler early-season seedbeds, stronger surface stratification of SOC and nutrients, and higher near-surface bulk density under NT, which limit early vigor and root penetration [12,23].

In the NCP, scientific evidence is scarce regarding soil temperature under long-term conservation tillage after planting, which hinders efforts to persuade farmers to adopt this agricultural practice without conclusive data. The effects of increasing soil temperature are reported to be limited to crop agronomic traits during the overwintering period; however, increasing soil temperature during the overwintering period and its response to the root system under long-term conservation tillage systems are unexplored and crucial. Therefore, the impacts of plastic films (black and white) under 22 years of LTCT practices on winter wheat root systems and soil thermal conditions during the overwintering period were evaluated. We hypothesized that low early spring (the period of rejuvenation and jointing) temperatures limit wheat yield by restricting root development, and that film mulching mitigates this constraint in no-tilled—but not necessarily in tilled systems by improving soil thermal conditions. However, we acknowledge that the actual mulching response may vary depending on the long-term soil physical properties developed under different tillage systems, which this study aimed to evaluate. We intended to estimate (1) the impacts of plastic film on soil thermal conditions during the early spring period (rejuvenation and jointing in March and April months) under tilled (MC) and no-till NC systems, and (2) to evaluate the effects of tillage and plastic film mulching on root system characteristics and their relationship with yield.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Experimental Area Description

The experimental study was conducted at the Luancheng Agroecosystem Experimental Station (37°53′ N, 114°41′ E), affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), on a long-term conservation tillage experimental field in Hebei Province, China’s North China Plain. The area features a temperate semiarid monsoon climate characterized by cold winters and hot summers. The mean annual air temperature is 12.5 °C, with an average yearly rainfall of 482 mm, approximately 70% of which falls between July and September. As reported by Wu et al. [24], the soil is termed a flavour-aquic type formed by an alluvial fan of limestone, and the soil classification is categorized as silt loam Haplic Cambisol (138 g kg−1 sand, 663 g kg−1 silt, and 199 g kg−1 clay). The availability of nutrients in the topsoil layer (0–20 cm) is as follows: total nitrogen (110 mg kg−1), phosphorus (15 mg kg−1), exchangeable potassium (95 mg kg−1), and soil organic matter (15 g kg−1). The major crops cultivated in the NCP are winter wheat and summer maize; therefore, the production of wheat and maize contributes 76% and 29% of the country’s total production, respectively. The dominant cropping system in this region is a winter wheat summer maize (or soybean) double-cropping system. Winter wheat is planted in mid-October and harvested in early June through sprinkler irrigation.

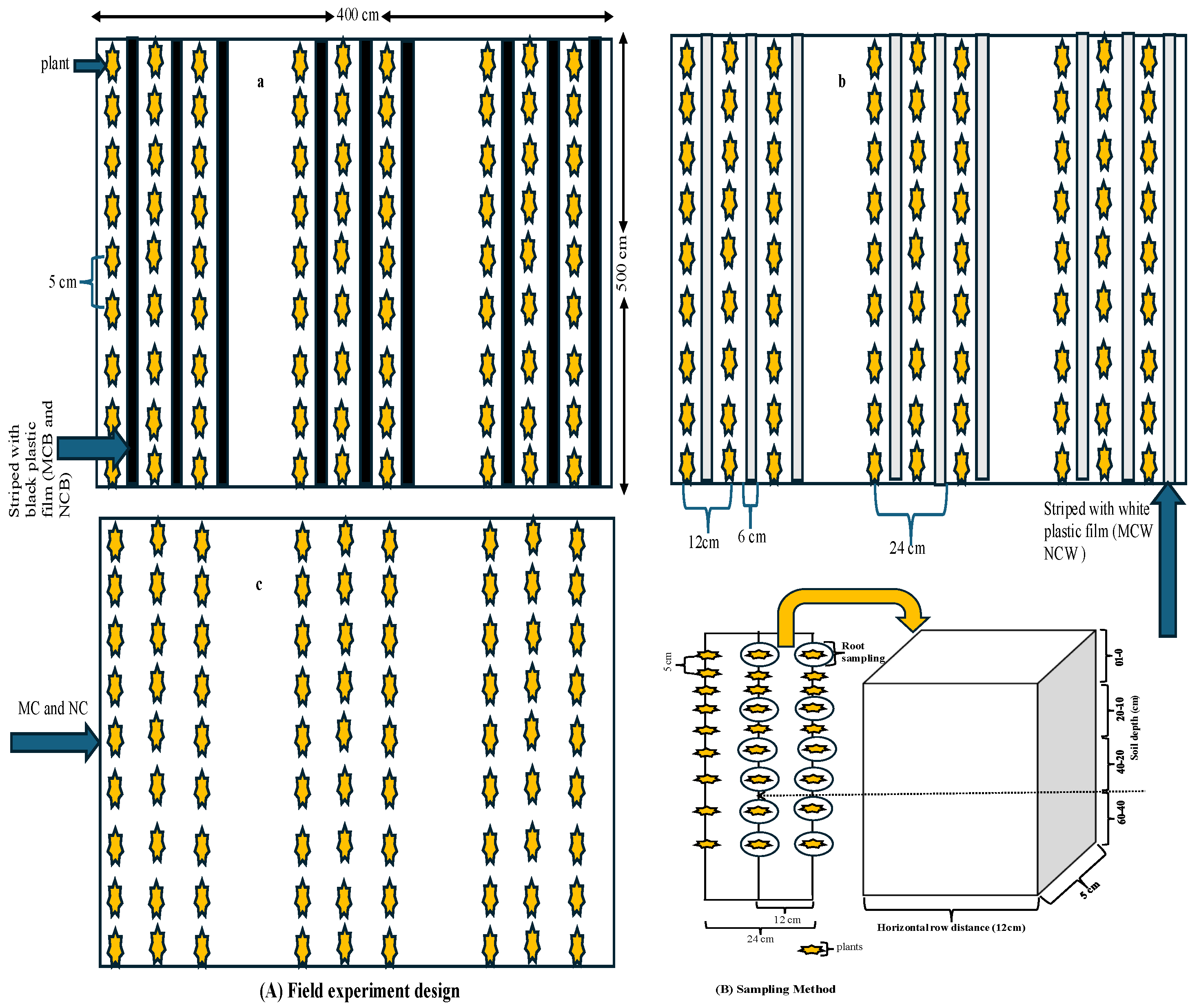

2.2. Main Experimental Plot Design

The experiment was designed on two well-established long-term conservation tillage practices that were initiated in October 2001, with complete randomized block design treatments: moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil (MC) and no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface (NC), which were used to investigate the objectives of our study. The ploughing depth for the MC treatment was approximately 20 cm. Both main experiments (MC and NC) had three replications and covered 560 m2 (8 m × 70 m, respectively). After the winter wheat harvest, the wheat straw was mechanically chopped (5–10 cm) and evenly distributed on the soil surface as mulch in all the treatments. No further tillage operation was performed during maize planting in MC. In the intermediate period after the winter wheat harvest in June, maize, which is 15–20 cm high, is planted in the wheat straw.

2.3. Split-Plot Experimental Design

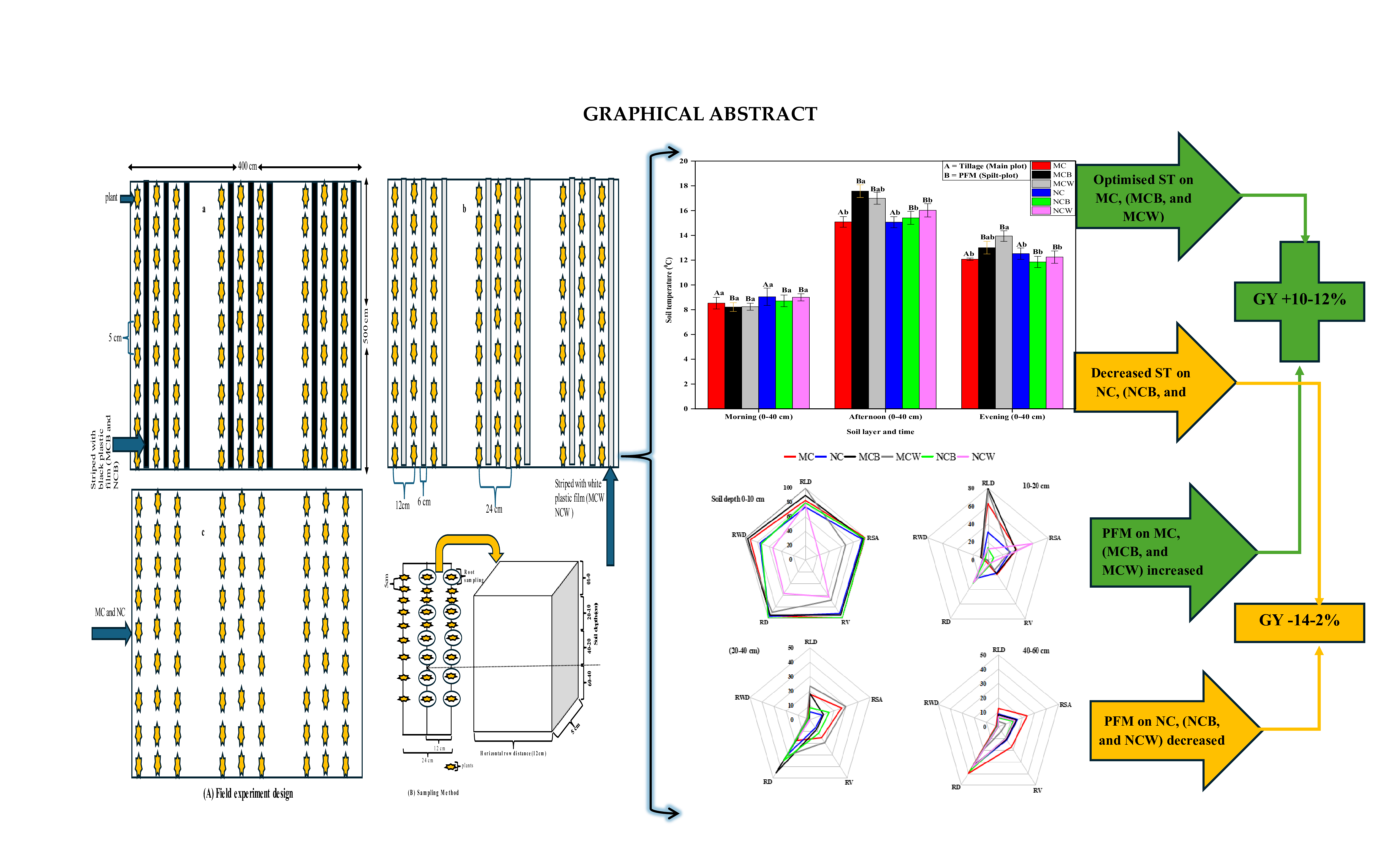

The main experimental plots (MC and NC) were split into four subplots to investigate the differences in the soil thermal conditions and their direct effects on the crop root system in MC and NC. To verify the different degrees of soil temperature in the soil profiles over 22 years of different long-term conservation tillage practices, both MC and NC were split and designed into additional subplots by applying plastic film (black and white/transparent) with a total area of 20 m

2 (4 m × 5 m) for each in 2024. Subplots were established in a randomized block design and replicated three times. The subplots were classified as MCB and MCW (MC with black plastic and white plastic films, respectively) and NCB and NCW (NC with black plastic and white plastic films, respectively). Specifically, both the black and white films were polyethylene (PE) with a thickness of 8 μm. The films had visible light transmittance of approximately 85% (white film) and 10% (black film), and solar reflectivity of about 70% (white film) and 15% (black film), respectively. A detailed layout of the experimental design for all the treatments is presented in

Figure 1. The plastic films were used to cover the soil strips adjacent to the crop rows only during March and April, 2024 (overwintering period or after the tillering to jointing stages), and then the plastic films were removed on April 30

th, 2024.

The cultivar Kenong1413, the most popular for winter wheat in the region, was sown. The sowing of seeds was accomplished on October 20, 2023, and harvesting was performed on June 10, 2024. The fertilizer application during the sowing stage was carried out as per local recommendations. Before the jointing stage, urea fertilizer was applied at a rate of 135 kg N ha−1. Agronomic control practices, including pest control and weed control, were performed equally by following local techniques for wheat. An identical amount of water was sprayed on each plot via a sprinkler irrigation system, and an extra two irrigations were applied accordingly, with an average of 40 to 50 mm per application, depending on precipitation. Before the soil moisture in the root zone reached 65% of the field’s capacity, irrigation was performed.

2.4. Monitoring the Soil Temperature (ST) and Soil Moisture Level

A soil thermometer, made with mercury in the glass, was installed at 0 cm, 5 cm, 10 cm, 20 cm, and 40 cm depths between the winter wheat rows in each treatment. The ST was recorded at three different times: morning (7:30–8.00 h), afternoon (13.30–14.00 h), and evening (17:30–18.00 h). The ST was recorded on alternate days from March 07th to April 30th, 2024. The ST was replicated three times for each reading for the daily average ST. The soil water level in the soil was determined at five depths (0–60 cm) at 10 and 20 cm intervals via the gravimetric method at four main crop growth stages (tillering, jointing, flowering, and maturity stages) via an 8 cm diameter soil core.

2.5. Measurements of Crop Roots and Aboveground Dry Matter (AGDM)

Crop roots were sampled from individual LTCT treatments (replicated three times, with one sample taken along the crop row and the other in the middle of the rows) when the root system reached its peak at the maturity stage (May 19, 2024), as described by [4]. We carefully removed the above-ground parts of the wheat plants before collecting root samples; the roots were sampled at soil depths of 0-10, 10-20, 20-40, and 40-60 cm, up to a depth of 60 cm. Washed roots were retrieved from water using a 2000 µm mesh sieve (Cahoon and Morton, 1961). Afterward, the roots were manually cleaned to prevent contamination and remove foreign particles, then dipped in a 10% (v/v) ethanol solution. Once gently extracted from the soil, the roots were stored at temperatures below 4 °C for further analysis. Root scanning was performed using an Epson Expression 1000XL scanner at 600 dpi, equipped with a dual lighting ribbon source to reduce sample overlap following the method described by [25]. The scanned images were analyzed using WinRHIZO 2013 software (Regent Instruments Inc., Canada, Figure A,

Supplementary Materials). Key root characteristics (RCs), such as root length (RL), root diameter (RD), root surface area (RSA), and root volume (RV), were measured. The data from the software were organized and further analyzed using a detailed Excel spreadsheet.

The root length density (RLD) and root weight density (RWD) were calculated based on the known volumes of soil and roots, respectively, following the methods of [26]. The root dry biomass (RDBM) was determined by oven drying the root samples at 65 °C until a constant weight was achieved. At crop maturity, aboveground dry matter (AGDM) was assessed by randomly selecting ten uniform plants from each treatment. These samples were oven-dried at 60 °C until all moisture was removed, and then the dry weights were recorded.

2.6. Estimation of Crop Yield Attributes

Harvesting of the winter wheat crop was conducted at the maturity stage manually from each plot to measure the crop grain yield and yield attributes (straw yield and 1000-grain weight) at a moisture content of 13%. The number of spikes was sampled by randomly calculating the area of 1.5 m2 in each plot, which was equivalent to 20 plants being picked to record the grain number and spike number.

2.7. Analysis of Data

Data were analyzed using a two-way split-plot ANOVA with tillage (MC and NC) as the main-plot factor and mulching (no mulch, black film, white film) as the subplot factor. When the interaction between tillage and mulching was significant, simple-effect comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05). Multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) and Pearson correlation analysis tests were conducted relating to STs and RCs and agronomic traits, respectively, via a correlation plot in OriginPro 2025 (Learning Edition). The data on root characteristics were normalized (0-100, mean) at four different soil depths (0-60 cm) to generate radar graphs.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Data

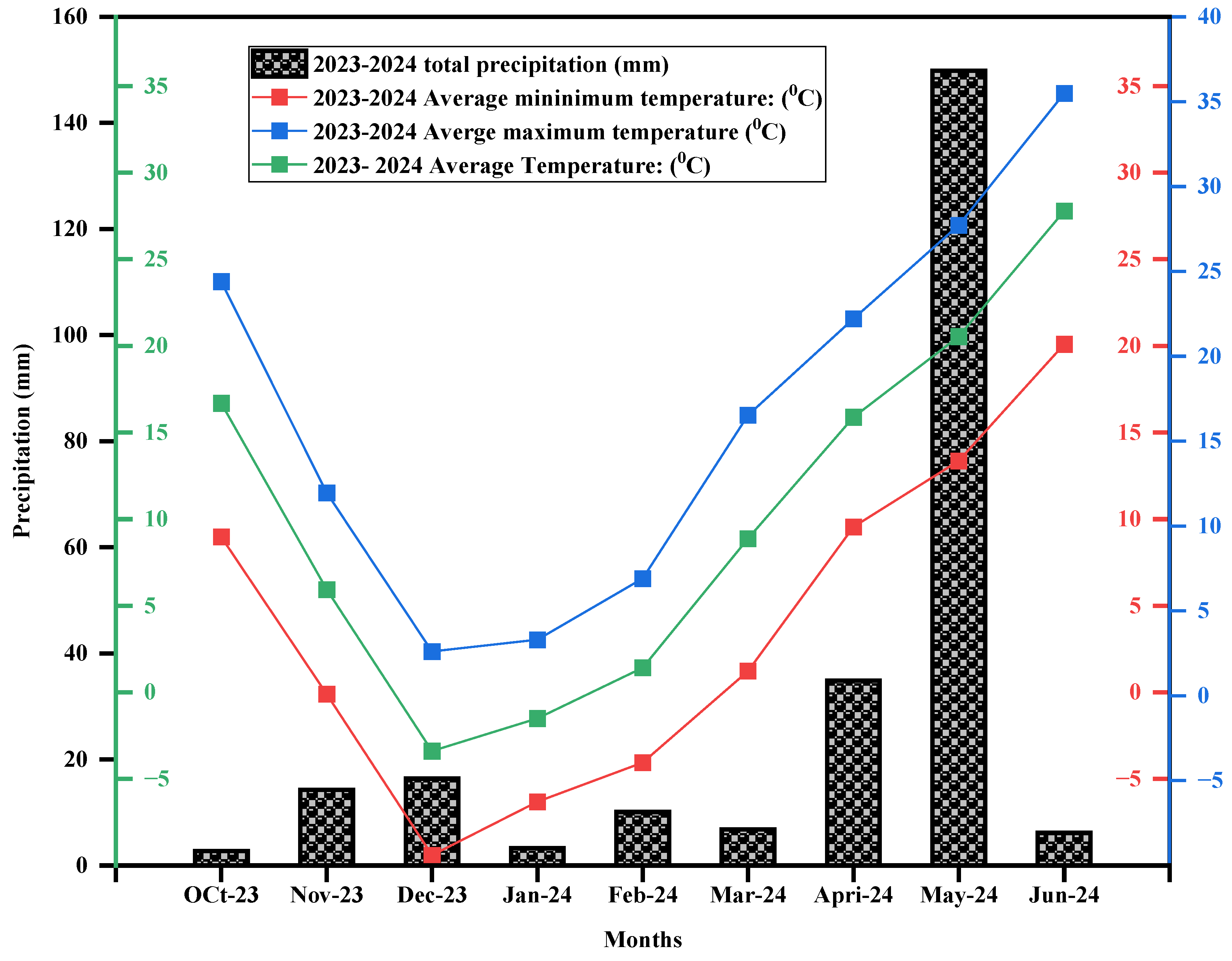

The average monthly precipitation and air temperatures (minimum, maximum, and average) from October 2023 to June 2024 are shown in

Figure 2. The average monthly precipitation was recorded as the highest in May 2024 (150 mm). In contrast, the lowest precipitation occurred in October 2023 (2.7 mm). The highest minimum, maximum, and average air temperatures were recorded in June 2024 (20.09, 27.8, and 38.48 °C, respectively), and the lowest were recorded in December 2023 (-9.41, 2.62, and -3.39 °C, respectively).

3.2. ST

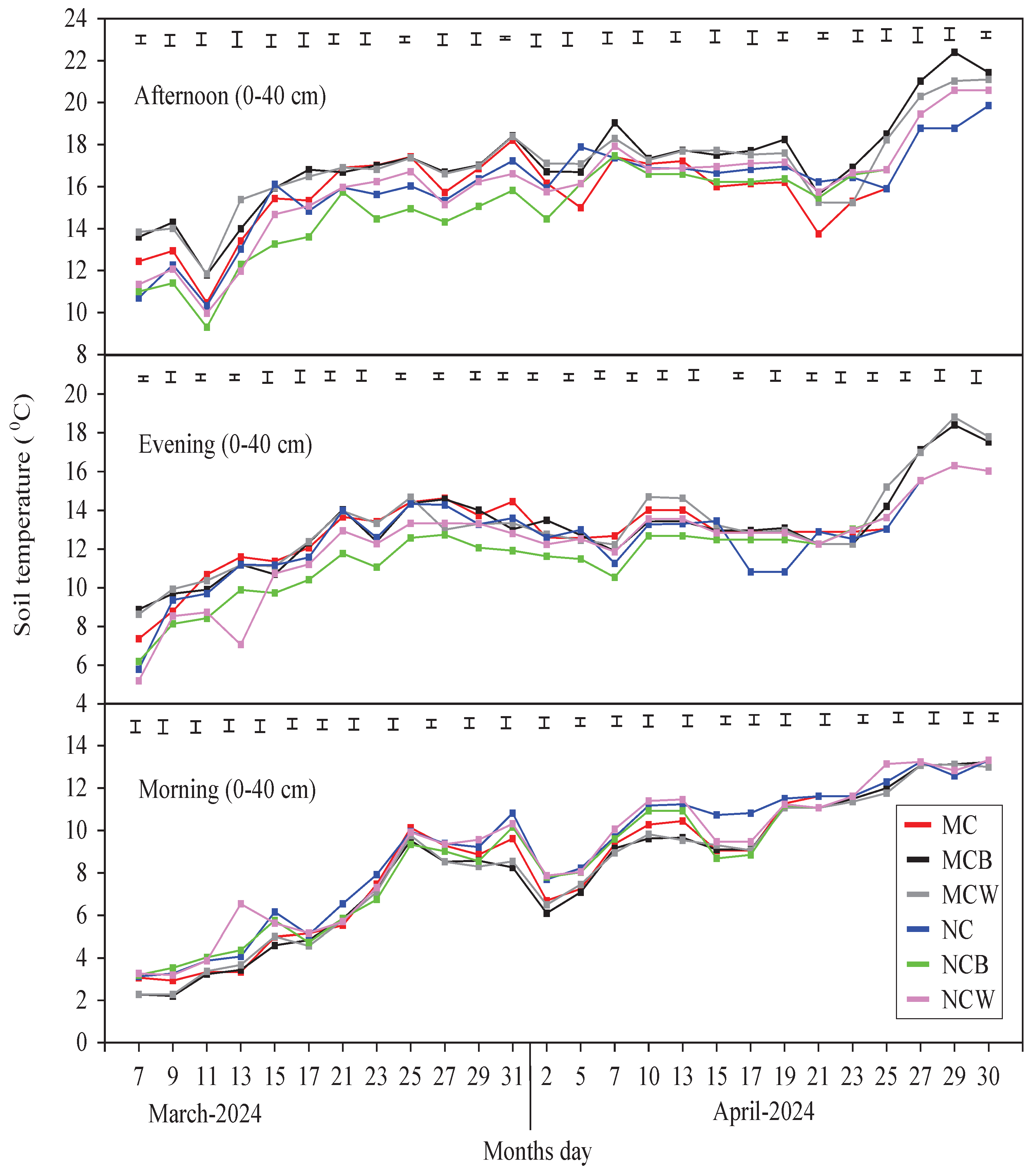

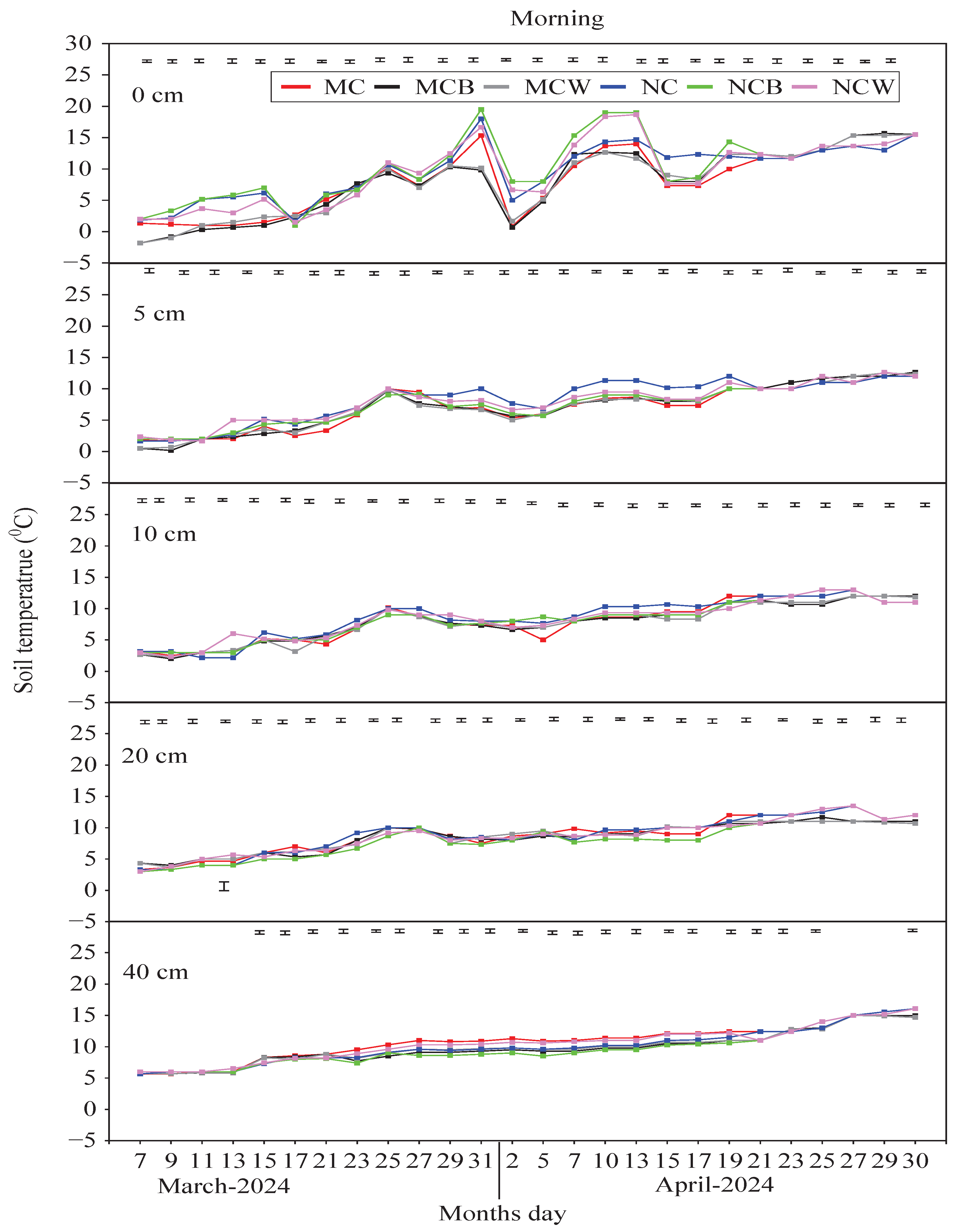

3.2.1. Dynamics of ST in the 0–40 cm Soil Layer with Time

Compared with the non–plastic film treatments, ST dynamics within the 0–40 cm profile were highest under both LTCT practices of FPM. In the afternoon, the greatest average ST was observed in MCB, followed by MCW, throughout the plastic film period, compared with MC and NC. The highest maximum average ST was 22.40 °C in MCB and 21.10 °C in MCW, followed by NCB (20.59 °C) and NCW (20.49 °C), while the lowest was recorded in MC (19.85 °C) and NC (19.60 °C) (

Figure 3a). Similarly, the lowest maximum average ST was 11.80 °C in MCB and 11.83 °C in MCW, compared with 10.47 °C in MC, 10.33 °C in NC, and the lowest in NCB (9.30 °C) and NCW (9.97 °C). A similar ST trend was observed in the evening, with MCB and MCW maintaining the highest STs across 0–40 cm compared with non–plastic film treatments. Overall, ST gradually decreased in FPM treatments during the initial days but later increased in MCB, MCW, and NCW. In contrast, MCB and MCW showed a weaker ST increase in the morning than NC, NCW, and NCB.

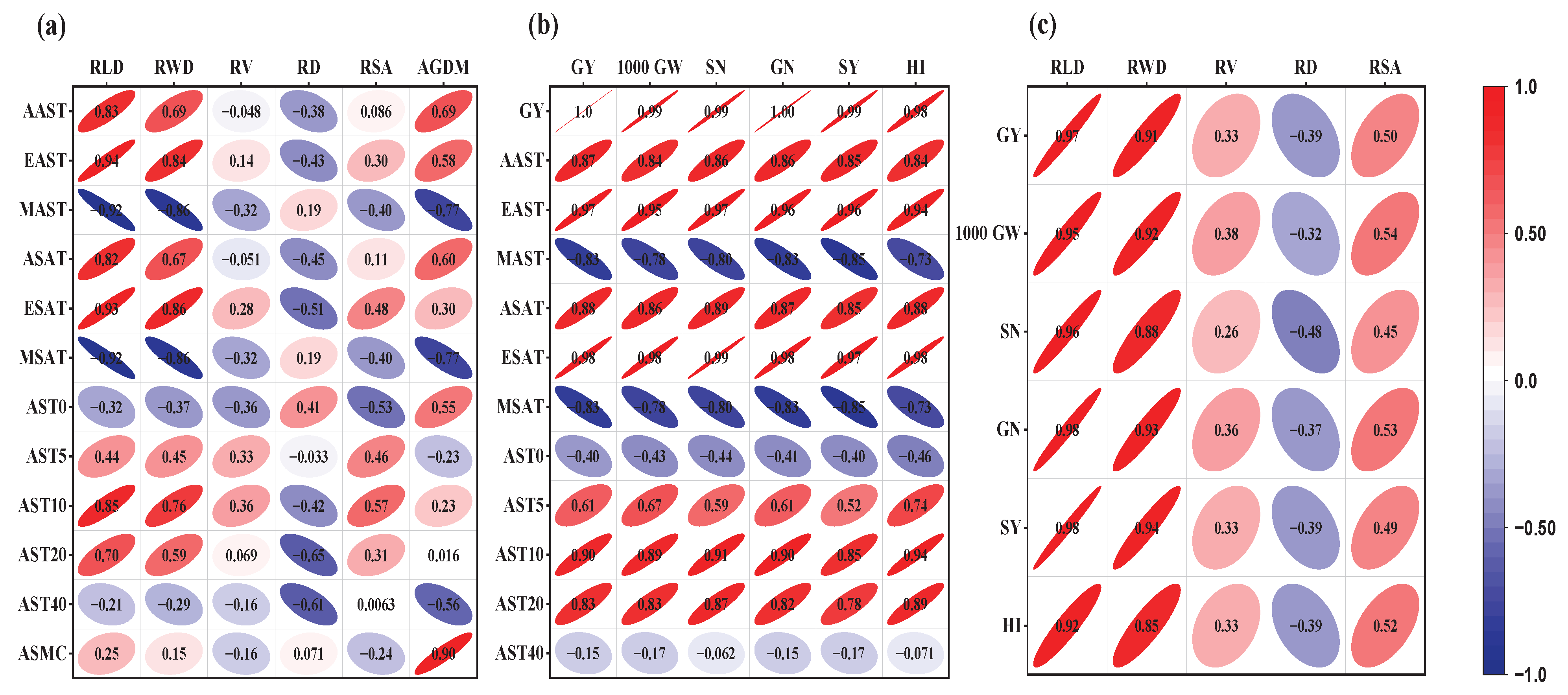

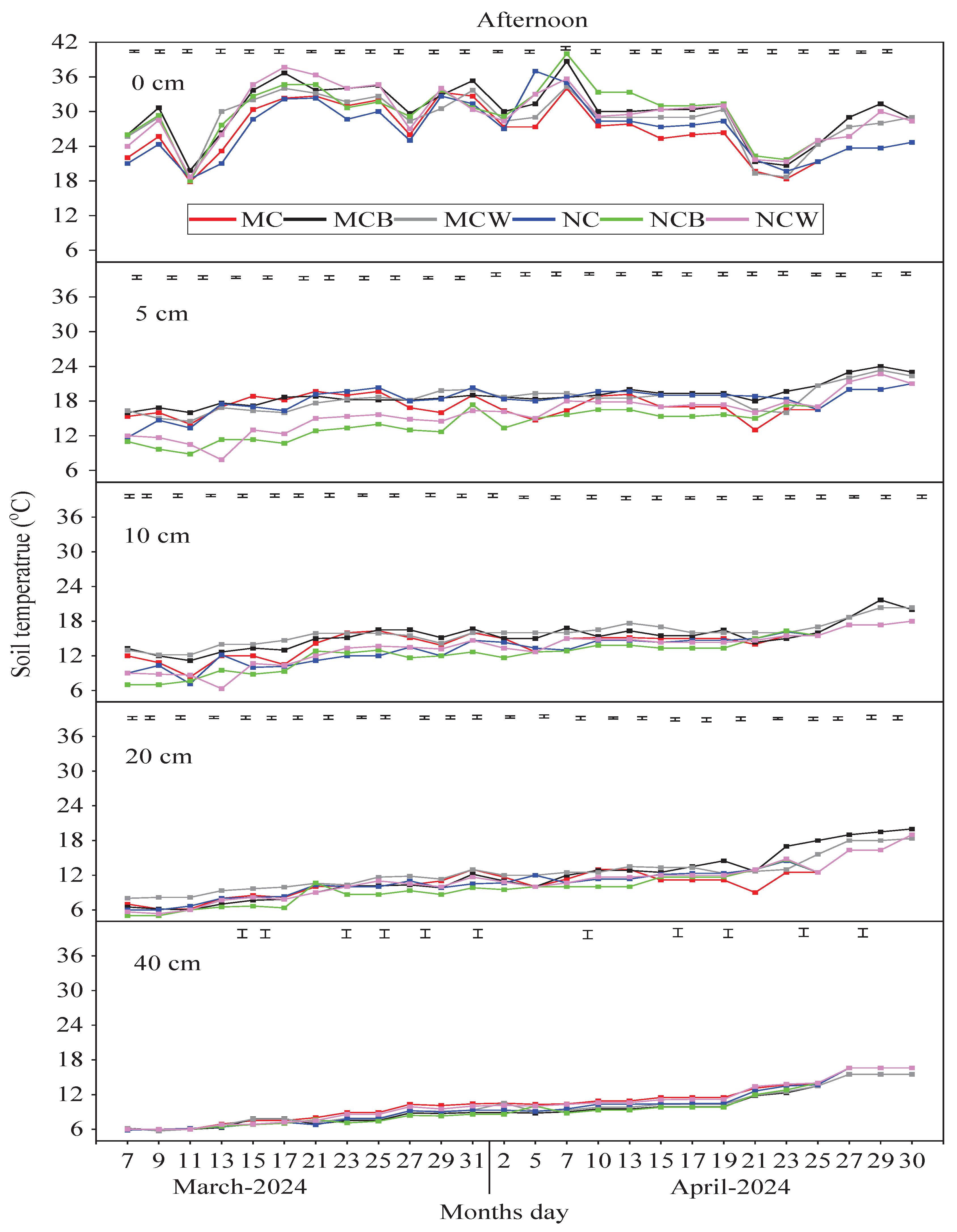

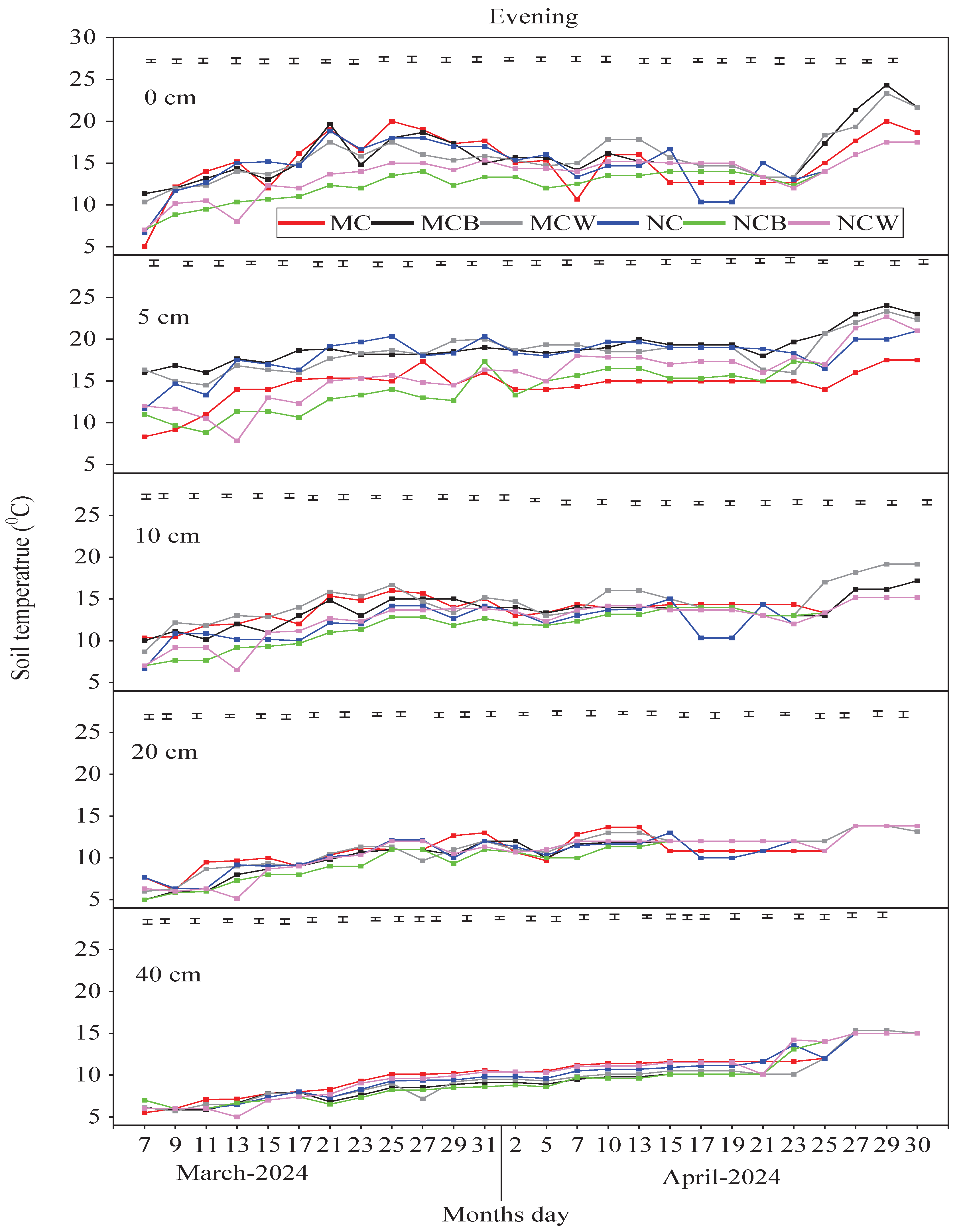

Figure 3b further indicates that at 5, 10, and 20 cm depths, MCB and MCW consistently maintained higher afternoon and evening STs than MC, NC, NCB, and NCW. This consistent pattern highlights the positive thermal influence of combining mulching with tillage. At 10 cm, daily fluctuations lessened, emphasizing the enhanced thermal retention of MCB and MCW (1–2 °C above NC and NCB). Even at 20 cm, both treatments sustained slightly higher and more stable STs. Moreover, correlations between root characteristics (RCs) and STs showed significant (p < 0.05) positive relationships between afternoon and evening average STs (AAST and EAST) and RLD (r = 0.83, 0.94), RWD (r = 0.69, 0.84), and AGBM (r = 0.69, 0.58), while RD was negatively correlated (r = −0.38, −0.34). In contrast, morning average STs (MAST) were negatively related to RCs and AGBM, indicating that lower morning STs were less favorable for winter wheat root growth and biomass accumulation compared with AAST and EAST during the overwintering period.

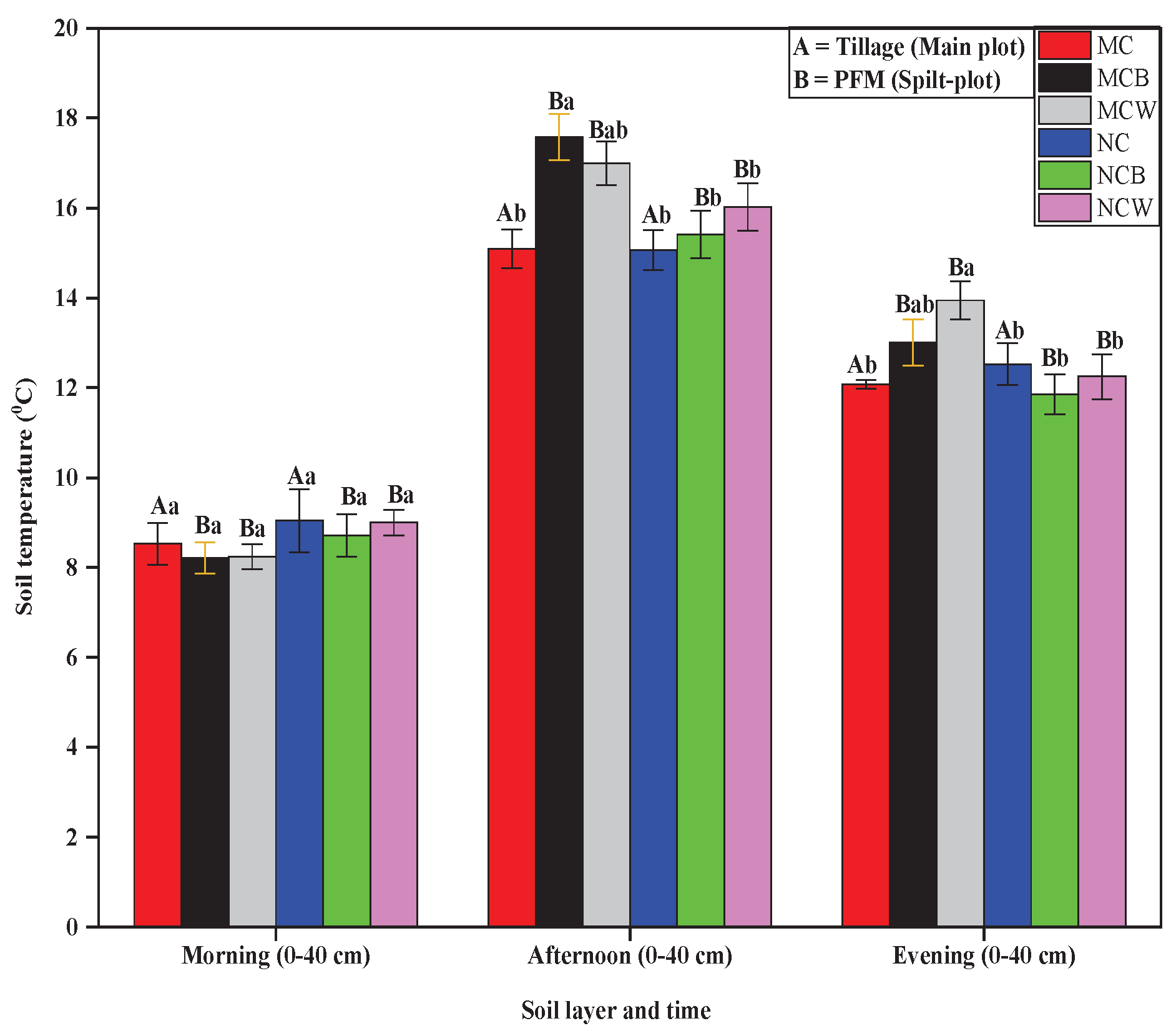

3.2.2. Averaged STs at 0-40 cm

Figure 4 shows the average ST at 0–40 cm during morning, afternoon, and evening throughout the overwintering period of winter wheat, influenced by tillage and plastic film mulching. Both tillage and FPM significantly affected ST in the afternoon and evening (p < 0.05), with a noteworthy tillage × mulching interaction (p < 0.05). In contrast, morning ST showed no significant differences among treatments. Across all times, MCB and MCW had the greatest soil warming, especially in the afternoon, followed by the evening. Compared to the un-mulched treatments, MCB and MCW increased the mean ST (0–40 cm) by 2.52 °C and 0.94 °C (MCB) and 1.94 °C and 1.87 °C (MCW) in the afternoon and evening, respectively. The warming effect was stronger under mouldboard tillage (MC) than under no-tillage (NC), indicating that tillage improved the soil’s thermal response to mulching by enhancing soil porosity and heat conduction.

In the morning, STs remained uniformly low (8.5–9.0 °C) across treatments, signifying that overnight cooling minimized treatment differences. By the afternoon, significant differences emerged: MCB had the highest ST (17.8 °C), followed by MCW, both significantly warmer than other treatments. In the evening, although all treatments experienced cooling, MCB and MCW retained higher residual heat (15.5 °C), confirming that combining tillage and mulching provided superior thermal retention.

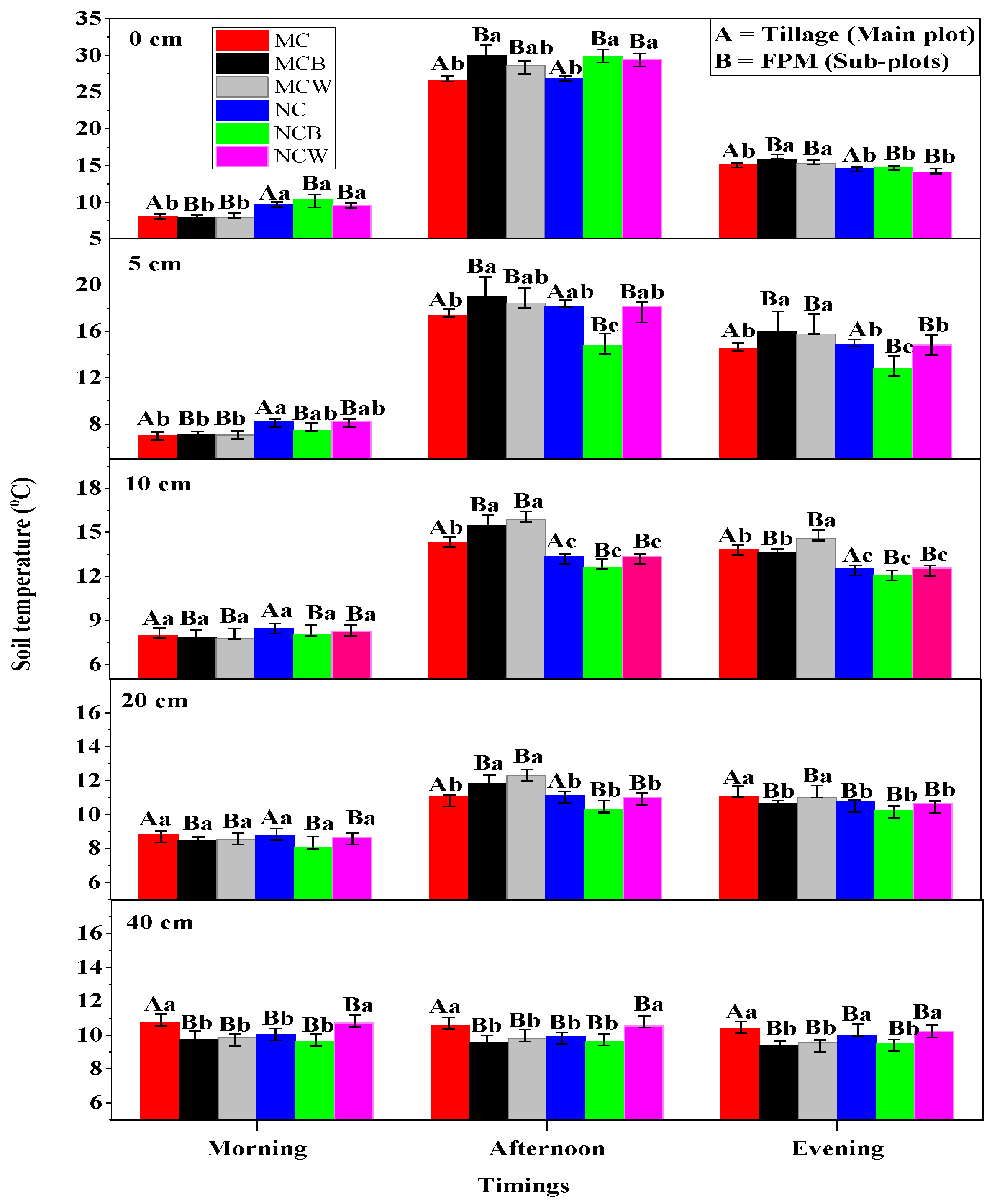

3.2.3. Averaged STs at Different Soil Depths and Timings

Figure 5 shows that both tillage and mulching had significant effects on ST across all depths (

p < 0.05), and their interaction was also significant (

p < 0.05), particularly in the afternoon and evening. The greatest difference in average STs at the 0 cm (AST0) depth occurred in MCB (30 °C) and NCB (29.77 °C), followed by MCW (28.62 °C) and NCW (29.44 °C) in the afternoon, compared with NC (26.28 °C) and MC (26.62 °C). Both MCB and MCW showed the highest average STs at 5, 10, and 20 cm depths (19.0 and 18.5 °C; 15.46 and 15.90 °C; 11.85 and 12.28 °C, respectively) compared to MC and NC treatments. At 40 cm, NCW and NCB recorded the highest average STs. A similar increasing trend in average ST was observed in the evening at 0 and 5 cm in MCB and MCW, followed by slight increases in NCW and NCB at 10 and 40 cm, respectively. During the morning, NC, NCW, and NCB exhibited higher average STs across depths than MC.

At 5 and 10 cm, temperature differences among treatments were more distinct, with MCB and MCW showing higher STs than MC, NC, NCB, and NCW. The combination of PFM with MC (MCB or MCW) enhanced soil thermal conductivity, enabling greater heat retention. At 20 cm, temperature differences began to converge, yet MCB and MCW maintained slightly higher STs, demonstrating deeper thermal benefits and warmer, more stable conditions in the upper 5–20 cm—crucial for root development. Positive correlations were found between STs at 5, 10, and 20 cm and RLD (r = 0.44–0.85), RWD (r = 0.45–0.76), and RSA (r = 0.31–0.57) (p < 0.05), while negative correlations appeared at 0 and 40 cm. RD and AGBM were positively correlated at 0 cm (r = 0.41, 0.55) and negatively at 40 cm (r = −0.61, −0.56) (p < 0.05).

3.2.4. Soil Accumulated Temperature (SAT)

Both tillage and PFM significantly affected the SAT across all soil depths (

p < 0.05), and their interaction was also significant (

p < 0.01) in the afternoon and evening (

Table 1). During the afternoon, soil heat accumulation increased markedly under PFM in both tillage systems, especially within the upper 0–20 cm soil layer. The highest SAT values were recorded in MCB (677 °C), NCB (670 °C), and NCW (662 °C) at 0 cm, followed by MCW (640 °C), while the lowest occurred in MC (588 °C) and NC (595 °C). Across 5–20 cm depths, MCB and MCW consistently maintained higher ASTs than NCB, NCW, and un-mulched plots, confirming that the warming effect of PFM was greatest under MC. At 40 cm, the effect of PFM was smaller, although NCW and NCB retained slightly higher temperatures, indicating limited but persistent downward heat transfer

In the evening, both tillage and PFM remained highly significant (p < 0.001), with strong interaction effects across all depths. Surface layers (0–10 cm) under MCB and MCW maintained the highest ASTs, while NCW and NCB showed moderate warming relative to NC. These results suggest that the combination of tillage and PFM improved heat retention capacity, moderating nocturnal soil cooling. In the morning, ST differences among treatments were smaller, yet both tillage and PFM still significantly affected AST (p < 0.001), with a strong interaction effect at all depths. No-tillage treatments (NC, NCW, NCB) tended to retain more residual heat near the surface than MC treatments, likely due to reduced soil heat loss overnight under residue cover. Moreover, the SAT in the afternoon and evening showed strong positive correlations with root traits and yield components: RLD (r = 0.82–0.93, p < 0.05), RWD (r = 0.67–0.86, p < 0.05), RSA (r = 0.11–0.48, p < 0.05), and AGDM (r = 0.30–0.60, p < 0.05). Conversely, morning AST was negatively correlated with RLD (r = –0.92, p < 0.05), RWD (r = –0.86, p < 0.05), and AGDM (r = –0.77, p < 0.05), indicating that excessive nocturnal cooling may have limited early root and shoot activity.

Table 1.

Accumulated soil temperature from March to April (during the overwintering period). MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

Table 1.

Accumulated soil temperature from March to April (during the overwintering period). MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

| Time |

Treatments |

Accumulated Soil Temperature (0C) |

| Soil depth (cm) |

0 |

5 |

10 |

20 |

40 |

| Afternoon |

MC |

588.00 c |

348.83 c |

268.83 c |

182.83 d |

170.13 a |

| MCB |

677.17 a |

391.23 a |

299.03 b |

205.17 b |

144.73 b |

| MCW |

639.67 b |

375.67 b |

308.87 a |

215.15 a |

150.47 b |

| NC |

595.17 c |

378.17 b |

243.17 d |

185.30 c |

153.73 b |

| NCB |

670.00 a |

279.67 e |

224.33 e |

163.67 e |

145.80 b |

| NCW |

661.50 ab |

307.33 d |

242.17 d |

181.67 d |

170.18 a |

| PFM |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Tillage |

|

ns |

*** |

**** |

*** |

ns |

| Interaction |

|

* |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Evening |

MC |

287.67 c |

273.50 d |

255.67 c |

184.17 a |

165.90 a |

| MCB |

308.00 a |

311.50 a |

250.00 b |

173.67 d |

140.83 e |

| MCW |

292.33 b |

306.33 b |

275.17 a |

182.67 b |

144.97 d |

| NC |

274.83 e |

281.67 c |

220.80 d |

175.17 c |

155.89 c |

| NCB |

280.00 d |

228.33 e |

208.33 e |

162.13 e |

142.17 e |

| NCW |

263.00 f |

251.50 f |

222.67 d |

173.67 d |

161.27 b |

| PPM |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Tillage |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Interaction |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Morning |

MC |

107.83 d |

79.17 d |

102.50 d |

124.77 a |

174.53 a |

| MCB |

102.00 e |

80.10 d |

99.33 e |

116.10 c |

149.70 d |

| MCW |

103.50 e |

79.50 d |

97.83 e |

117.50 c |

152.87 c |

| NC |

148.50 b |

109.83 a |

116.17 a |

124.17 a |

157.01 b |

| NCB |

165.00 a |

89.17 c |

106.00 c |

106.00 d |

146.33 d |

| NCW |

144.83 c |

100.50 b |

110.17 b |

120.50 b |

174.23 a |

| PFM |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Tillage |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

ns |

| Interaction |

|

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

Table 2.

Grain yield and yield attributes under different tillage and mulching treatments. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). GY = grain yield, AGDM = aboveground dry matter, 100 GW = grain weight, SN = spike number, SY = straw yield, GN = grain number, and HI = harvest index. Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at * ** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

Table 2.

Grain yield and yield attributes under different tillage and mulching treatments. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). GY = grain yield, AGDM = aboveground dry matter, 100 GW = grain weight, SN = spike number, SY = straw yield, GN = grain number, and HI = harvest index. Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at * ** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

| Treatments |

GY

(kgha-1) |

1000-GW

(g) |

BM

(kgha-1) |

SNm-2

|

SY

(kgha-1) |

GN |

HI

(%) |

AGDM

(g Plant-1) |

| MC |

7445 b |

39.65 bc |

11791 a |

552 b |

7893 b |

34.02 b |

48.5 ab |

3.17 bc |

| MCB |

8169a |

41.00 ab |

15458 a |

566 ab |

8190 ab |

35.19 a |

49.9 a |

4.07 ab |

| MCW |

8300 a |

41.07a |

16272 a |

572 a |

8499 a |

35.28 a |

49.4 a |

4.23 a |

| NC |

6590 c |

38.50c |

13244 a |

527 c |

7306 c |

32.43 c |

47.4 bc |

2.79 c |

| NCB |

5486 d |

35.93d |

11315 a |

498 d |

6799 d |

30.57 d |

44.6 d |

3.78 ab |

| NCW |

5794 d |

36.33 d |

12942 a |

515 cd |

6827 d |

30.97 d |

45.9 cd |

3.49 abc |

| PFM |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

| Tillage |

*** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

ns |

| Interaction |

*** |

** |

ns |

** |

*** |

*** |

** |

ns |

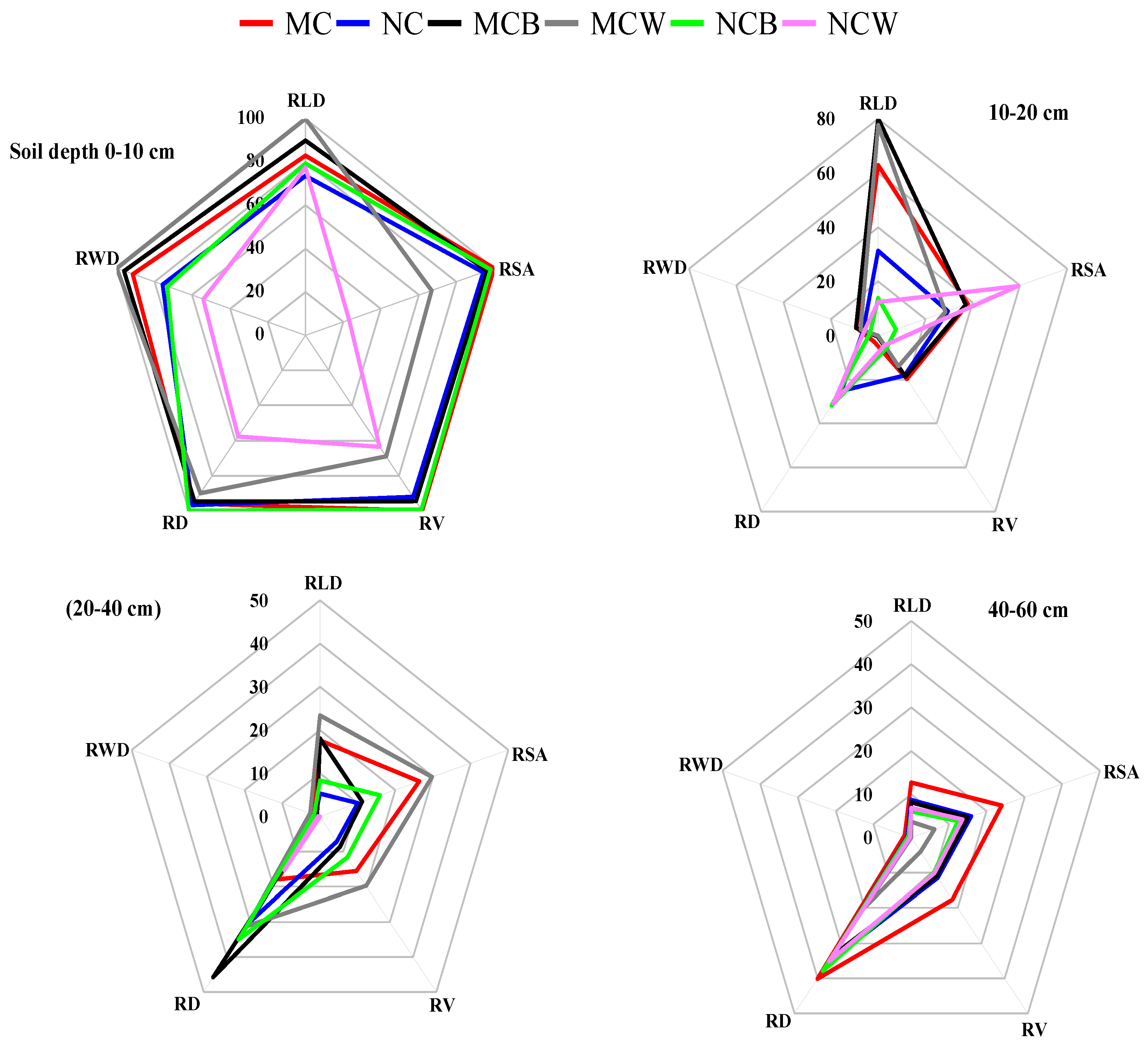

3.3. Effects of STs on Root Characteristics (RC)

Compared with the MC and NC treatments, the FPM treatments, especially the MCB and MCW treatments, markedly increased the RC (RLD, RWD, RSA, and RD) in the upper 0–20 cm soil layer, whereas the effects diminished with depth. These improvements indicate enhanced root proliferation and resource uptake near the surface, underscoring the crucial role of mulching and tillage in shaping the root architecture of winter wheat. Across all the soil layers, MC promoted greater root diameter and volume below 20 cm, whereas NC had shallower, denser roots concentrated in the topsoil. The two-way split-plot ANOVA revealed that

tillage had a highly significant effect on RLD and RWD at 0–10, 10–20, and 20–40 cm soil depths (

p < 0.001), while the main effect of plastic film mulching (FPM) was not significant at most depths. However, a significant Tillage × FPM interaction was observed in the upper 0–20 cm, indicating that the effect of mulching on root proliferation depended on the tillage system (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Root characteristics (RCs) of different plastic and non-plastic under long-term conservation tillage practices. Root length, RLD = Root length density, RWD = Root weight density, RSA = root surface area. RV = root volume, RD = root diameter. Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

Table 3.

Root characteristics (RCs) of different plastic and non-plastic under long-term conservation tillage practices. Root length, RLD = Root length density, RWD = Root weight density, RSA = root surface area. RV = root volume, RD = root diameter. Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3). Significance levels at *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, and ns show not significant.

| Treatments |

Soil Depth

(cm) |

RLD

(cm cm-3) |

SE

(±) |

RWD

(g cm-3) |

SE (±) |

RSA

(cm2) |

SE

(±) |

RV

(cm3) |

SE

(±) |

RD

(mm) |

SE

(±) |

| MC |

0-10 |

3.85 ab |

0.33 |

1.09 ab |

0.04 |

286.85 a |

27.19 |

2.71 a |

0.42 |

3.75 a |

0.29 |

| MCB |

4.15 a |

0.0 |

1.15 ab |

0.06 |

277.03 a |

20.78 |

2.58 a |

0.15 |

3.73 a |

0.07 |

| MCW |

4.59 a |

0.0 |

1.19 a |

0.07 |

200.24 b |

37.74 |

1.92 a |

0.61 |

3.65 a |

0.51 |

| NC |

3.45 b |

0.0 |

0.91 bc |

0.15 |

271.89 a |

28.41 |

2.51 a |

0.46 |

3.77 a |

0.35 |

| NCB |

3.70 b |

0.4 |

0.88 bc |

0.04 |

281.93 a |

33.36 |

2.70 a |

0.34 |

3.82 b |

0.06 |

| NCW |

3.62 b |

0.5 |

0.65 c |

0.12 |

86.67 b |

40.02 |

1.78 a |

0.50 |

3.07 a |

0.21 |

| Tillage (T) |

** |

|

*** |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

* |

|

| FPM |

* |

|

* |

|

** |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

Interaction

(T x FPM) |

* |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

| MC |

10-20 |

2.99 b |

0.36 |

0.13 a |

0.01 |

125.18 ab |

16.78 |

0.66 a |

0.10 |

2.10 b |

0.03 |

| MCB |

3.74 a |

0.10 |

0.13 a |

0.01 |

123.03 ab |

23.51 |

0.63 a |

0.12 |

2.06 b |

0.02 |

| MCW |

3.63 a |

0.31 |

0.10 a |

0.001 |

100.47 ab |

9.78 |

0.51 a |

0.04 |

2.05 b |

0.03 |

| NC |

1.63 a |

0.42 |

0.09 a |

0.03 |

103.32 ab |

34.49 |

0.62 a |

0.16 |

2.50 a |

0.18 |

| NCB |

0.88 b |

0.01 |

0.06 a |

0.001 |

45.73 b |

2.42 |

0.30 a |

0.02 |

2.62 a |

0.04 |

| NCW |

0.82 c |

0.07 |

0.09 a |

0.06 |

180.23 a |

83.13 |

0.27 a |

0.03 |

2.60 a |

0.13 |

| T |

*** |

|

ns |

|

* |

|

ns |

|

* |

|

| FPM |

* |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

Interaction

(T x FPM) |

* |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

| MC |

20-40

|

1.04 a |

0.12 |

0.04 a |

0.01 |

94.83 ab |

11.38 |

0.55 a |

0.05 |

2.37 a |

0.22 |

| MCB |

1.06 a |

0.00 |

0.02 a |

0.01 |

55.54 bc |

17.42 |

0.38 a |

0.08 |

2.86 a |

0.37 |

| MCW |

1.29 a |

0.04 |

0.05 a |

0.01 |

103.73 a |

23.09 |

0.66 a |

0.12 |

2.60 a |

0.13 |

| NC |

0.51 bc |

0.42 |

0.03 a |

0.01 |

52.32 bc |

5.45 |

0.34 a |

0.04 |

2.58 a |

0.08 |

| NCB |

0.64 b |

0.02 |

0.03 a |

0.00 |

67.81 abc |

8.42 |

0.45 a |

0.06 |

2.67 a |

0.10 |

| NCW |

0.28 c |

0.05 |

0.02 a |

0.01 |

26.29 c |

12.84 |

0.16 a |

0.08 |

2.32 a |

0.04 |

| T |

*** |

|

ns |

|

* |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

| FPM |

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

Interaction

(T x FPM) |

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

| MC |

40-60 |

0.83 a |

0.22 |

0.04 a |

0.01 |

88.70 a |

26.36 |

0.61 a |

0.17 |

2.76 a |

0.28 |

| MCB |

0.63 a |

0.00 |

0.02 a |

0.00 |

65.51 a |

2.99 |

0.43 a |

0.03 |

2.65 a |

0.18 |

| MCW |

0.44 a |

0.02 |

0.02 a |

0.01 |

42.39 a |

9.49 |

0.26 a |

0.07 |

2.40 a |

0.08 |

| NC |

0.65 a |

0.13 |

0.03 a |

0.01 |

67.65 a |

17.92 |

0.45 a |

0.10 |

2.68 a |

0.26 |

| NCB |

0.54 a |

0.01 |

0.02 a |

0.00 |

58.72 a |

8.32 |

0.41 a |

0.09 |

2.72 a |

0.27 |

| NCW |

0.58 a |

0.09 |

0.02 a |

0.00 |

61.56 a |

18.96 |

0.41 a |

0.13 |

2.68 a |

0.01 |

| T |

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

| FPM |

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

Interaction

(T x FPM) |

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

ns |

|

3.3.1. Improvement in Root Length Density (RLD) and Root Weight Density (RWD)

The optimized ST attributes at 0–40 cm under plastic film mulching (black and white) with long-term conservation tillage (MC) significantly influenced root length density (RLD) and root weight density (RWD) at shallow depths (0–20 cm) (p < 0.001), while no significant effects occurred at 40–60 cm. Normalized data (0–100) showed the highest total RLD and RWD (0-60cm) in MCW (9.51 cm cm⁻³ and 1.35 g cm⁻³,

Table 3) and MCB (8.95 cm cm⁻³ and 1.30 g cm⁻³), followed by MC (7.88 cm cm⁻³ and 1.26 g cm⁻³) and NC (5.58 cm cm⁻³ and 1.03 g cm⁻³). The most significant increases (p < 0.05) occurred in RLD at 0–10 and 10–20 cm in MCW and MCB due to enhanced ST and tillage effects, while NCW consistently had the lowest values, likely due to cooler, compacted soil and reduced heat reflection. In the 20–40 cm layer, MCW surpassed MCB in RLD, indicating deeper root penetration, whereas MC showed the highest values at 40–60 cm, suggesting effective deep rooting under tillage.

Figure 8 showed strong positive correlations (r = 0.85–0.90, p < 0.005) were observed between RLD, RWD, and yield attributes (GY, 100 GW, SN, SY, GN, and HI).

3.3.2. Influence on Root Surface Area (RSA)

Considering all the observations across the soil layers (0–60 cm) for the distribution of RSA, tillage and PFM significantly increased RSA (180 cm

2) in NCW at a topsoil depth of 10–20 cm, whereas in the intermediate soil layer (20–40), RSA was highest in MCW (103.72 cm

2) compared with NC (52 cm

2) (

Figure 6 and

Table 3). The deeper soil layer (40-60) was not significantly different among the tillage and PFM treatments, whereas MC presented the highest RSA (88.70 cm

2), followed by NC (67.65 cm

2), and MCW presented the lowest RSA (42.39 cm

2 and 13.67 cm

2, respectively). In addition, positive correlations were detected between RSA and GY (r = 0.5, p < 0.05), 100 GW (r = 0.54, p < 0.005), SN (r = 0.45, p < 0.05), GN (r = 0.53, p < 0.005), SY (r = 0.49, p < 0.05), and HI (r = 0.52, p < 0.05).

3.3.3. Root Volume (RV) and Root Diameter (RD) Response to STs

The increase in soil temperature from shallow to deeper layers showed no significant effect of plastic film mulching (PFM) on root volume (RV), at 20–40 cm, where MCW had the highest RV (0.66 cm³) compared with NC (0.34 cm³). The greatest RV occurred at 0–10 cm in MC (2.71 cm³), followed by NCB (2.70 cm³) and MCB (2.58 cm³), with the lowest in MCW (1.92 cm³). Root depth (RD) differed significantly only at 10–20 cm, being higher in NCB (2.62 mm) and NCW (2.60 mm) than in MC (2.09 mm), MCB (2.06 mm), and MCW (2.05 mm). RV correlated positively (r = 0.26–0.38) and RD negatively (r = −0.32 to −0.48) with agronomic traits (p < 0.05).

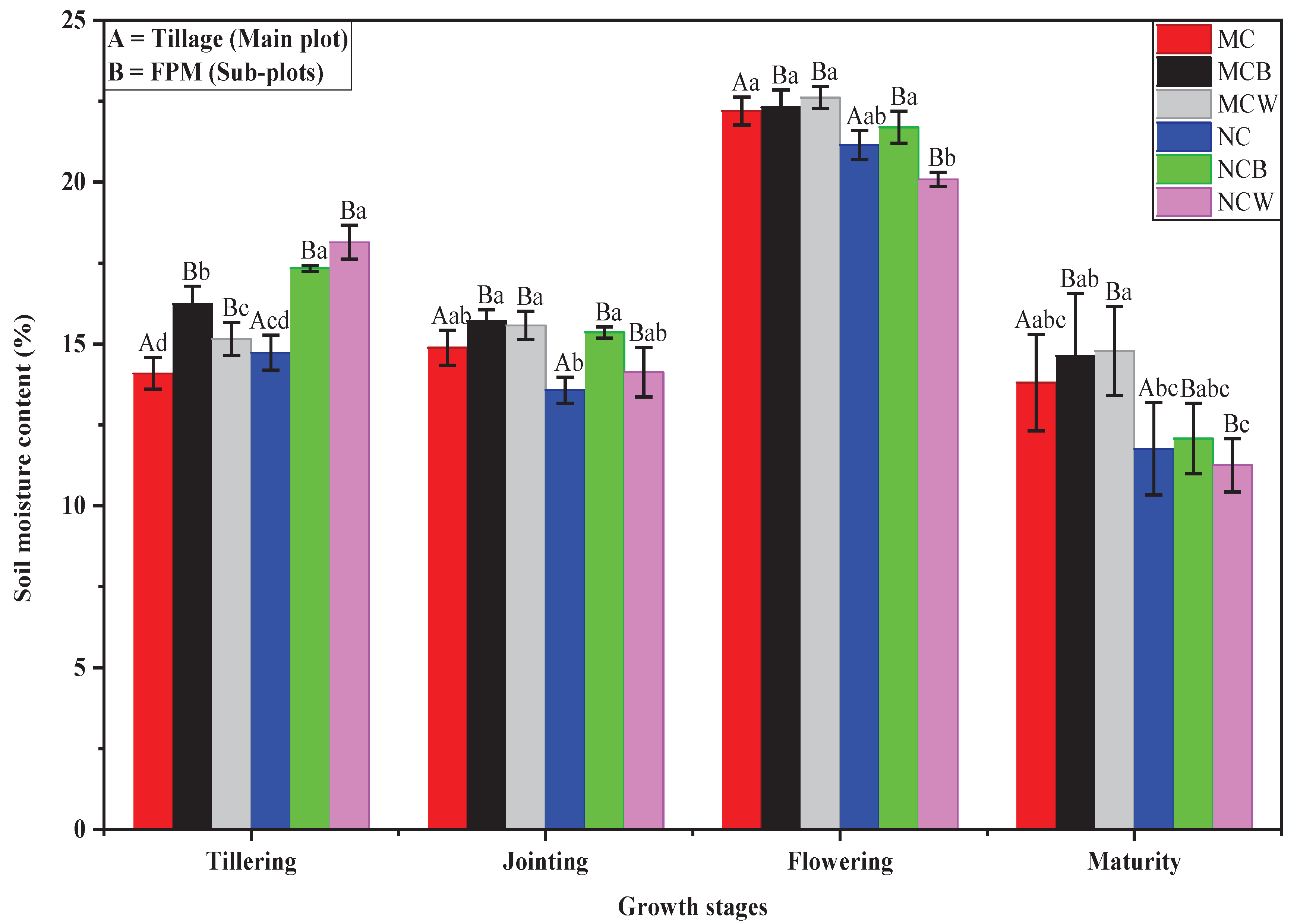

3.4. Effects of Soil Moisture Content (SMC) at Different Growth Stages

SMC varied significantly among treatments and soil depths (0–60 cm) across winter wheat growth stages. The two-way split-plot ANOVA revealed that both tillage and the tillage × mulching interaction had a significant effect on SMC across all stages (p < 0.05). In contrast, the main effect of mulching alone was not significant (p > 0.05). At tillering, NCB and NCW showed the highest SMC (>18%), while NC had the lowest. Similar but smaller differences occurred at a deeper layer (0-60 cm). During jointing, SMC stabilized (13–18%) across treatments. At flowering, SMC increased sharply due to the heavy May rainfall, with NCB and NCW maintaining the highest values. SMC declined across treatments, lowest in NC and the highest in NCB and NCW across 0-60 cm soil depth. Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis showed that an average SMC (ASMC) correlated positively with AGDM, AAST, and EAST (r = 0.58-0.9, p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Soil moisture content (0–60 cm) under different treatments during the winter wheat growing season (Tillering, Jointing, Flowering, and Maturity stages, respectively). MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3).

Figure 7.

Soil moisture content (0–60 cm) under different treatments during the winter wheat growing season (Tillering, Jointing, Flowering, and Maturity stages, respectively). MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). Lowercase letters denote differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments (n = 3).

Figure 8.

Pearson correlation analysis of soil temperature (ST) and root characteristics (RC) (a), ST and agronomic traits (b), and RC and agronomic traits (c). RLD = root length density, RWD = root weight density, RSA = root surface area. RV = root volume, RD = root diameter, AAST = afternoon average soil temperature, EAST = evening average soil temperature, MAST = morning average soil temperature, ASAT = afternoon accumulated soil temperature, EAST = evening accumulated soil temperature, MSAT = morning accumulated soil temperature, AST0 = average soil temperature at 0 cm, AST5 = average soil temperature at 5 cm, AST10 = average soil temperature at 10 cm, AST20 = average soil temperature at 20 cm, AST40 = average soil temperature at 40 cm, AGDM = aboveground dry matter, and ASMC = average soil moisture content. GY = grain yield, 100-GW = grain weight, GN = grain number, SN = spike number, SY = straw yield, HI = harvest index.

Figure 8.

Pearson correlation analysis of soil temperature (ST) and root characteristics (RC) (a), ST and agronomic traits (b), and RC and agronomic traits (c). RLD = root length density, RWD = root weight density, RSA = root surface area. RV = root volume, RD = root diameter, AAST = afternoon average soil temperature, EAST = evening average soil temperature, MAST = morning average soil temperature, ASAT = afternoon accumulated soil temperature, EAST = evening accumulated soil temperature, MSAT = morning accumulated soil temperature, AST0 = average soil temperature at 0 cm, AST5 = average soil temperature at 5 cm, AST10 = average soil temperature at 10 cm, AST20 = average soil temperature at 20 cm, AST40 = average soil temperature at 40 cm, AGDM = aboveground dry matter, and ASMC = average soil moisture content. GY = grain yield, 100-GW = grain weight, GN = grain number, SN = spike number, SY = straw yield, HI = harvest index.

3.5. Response of Crop Yield Attributes and Aboveground Dry Matter (AGDM)

Grain yield and yield attributes showed a significant response to tillage and to the interaction between tillage and mulching (p< 0.05); however, the main effect of mulching alone was not significant (

Table 2). MCW and MCB significantly improved grain yield (GY) and yield attributes, increasing GY by 23.96% and 28.94%, respectively, compared with NC, while NCB and NCW reduced GY by 16.75% and 12.07%. Compared to non-PFM, MCW and MCB increased 1000 GW (6.68%, and 6.49%), SN (8.53%, and 7.27%), GN (8.79% and 8.51%), SY (16.32%, and 12.09%), and HI (4.20%, and 5.31%). AGDM was highest under MCW (4.23 g plant⁻¹) and MCB (4.07 g plant⁻¹), significantly exceeding NC (2.79 g plant⁻¹) and MC (3.17 g plant⁻¹). AGDM, with MCW and MCB increased by 1.44 and 1.28 g plant⁻¹ compared with NC. NCB and NCW showed smaller improvements. GY and yield attributes were strongly positively correlated with STs (AAST, EAST, ASAT, AST₅–AST₂₀; r = 0.84–0.97, p < 0.05) and negatively with MAST and MSAT (r = −0.73 to −0.85, p < 0.05). AGDM correlated positively with AAST, EAST, ASAT, AST₀, and ASMC (r = 0.3–0.9, p < 0.05) and negatively with MAST, MSAT, and AST40 (r = −0.56 to −0.77, p < 0.05).

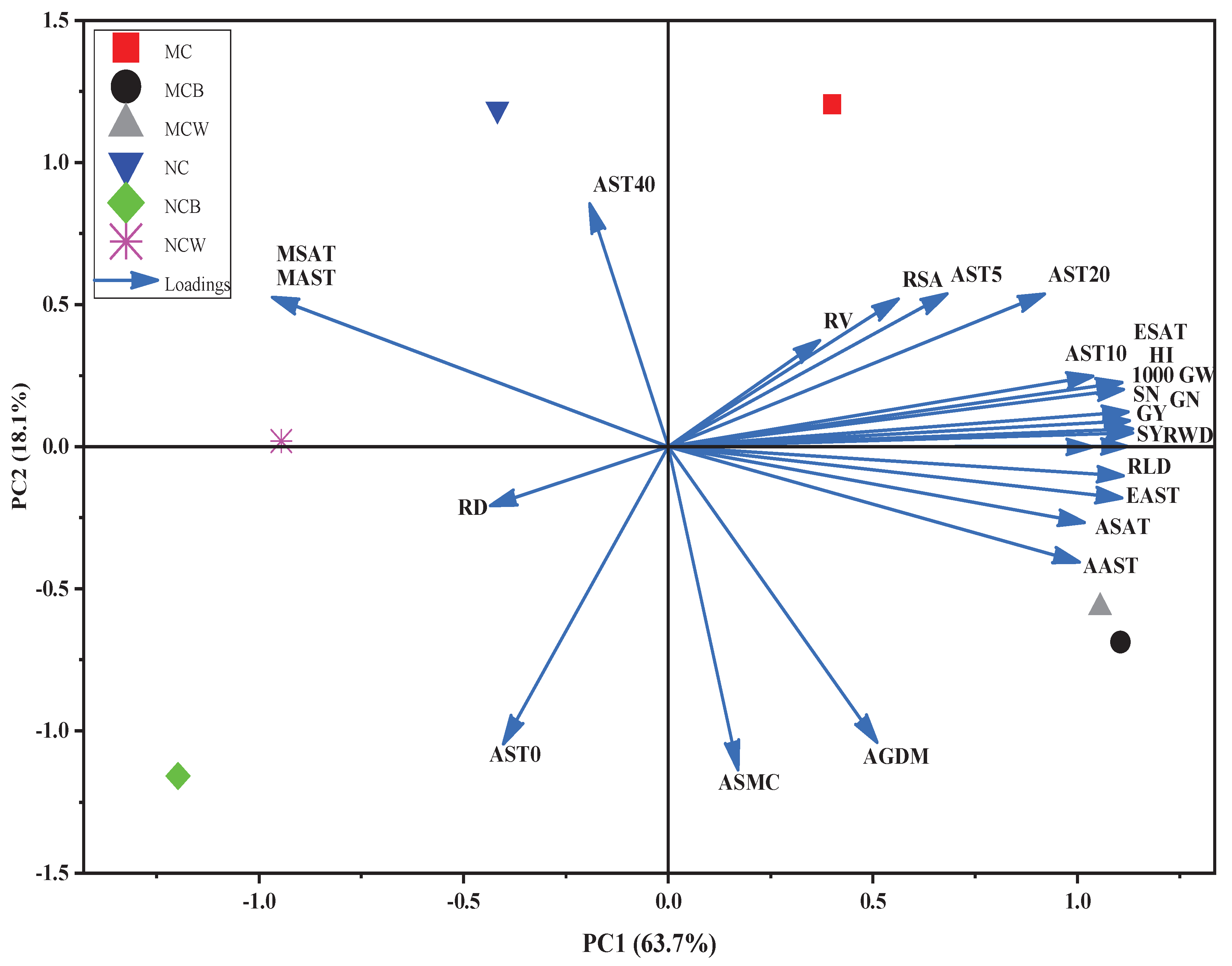

3.6. Multivariate Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to Tillg Systems and PFM

PCA was conducted to assess the multivariate relationships among RCs, ST parameters, and yield components under six soil management treatments. The first two components, PC1 and PC2, explained 63.7% and 18.1% of total variation, respectively (

Figure 9). PC1, dominated by RCs and yield attributes (RLD, RWD, RSA, RV, GY, SN, GN, 1000 GW, and HI), showed strong positive loadings, with MCB and MCW positioned positively, indicating enhanced root development and yield performance under plastic film mulching and tilled system. Conversely, NCW and NCB were negatively aligned with PC1 and PC2, associated with cooler morning soil temperatures (MAST, MSAT) and weaker growth. PC2 reflected variation in deeper soil temperatures (AST40), distinguishing MC due to greater temperature fluctuation at depth. NC (non-mulched, no-tillage) showed minimal association with RCs and yield attributes. Overall, PCA confirmed that tillage treatments with PFM, especially MCB and MCW, improved soil microclimate, RCs (RLD, RWD), and crop productivity compared to tillage alone (MC) and with FPM on the no-tillage system, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Tillage and PFM on Soil Temperature During the Overwintering Period

The significant interaction between tillage and mulching indicates that the response of ST to plastic film depended on the tillage systems. Under the tilled system (MC), film mulching improved soil aeration and heat transfer, resulting in higher soil temperatures. In contrast, under no-tillage, the compacted surface and residue cover likely reduced heat conduction, minimizing the mulching effect. These findings emphasize that soil disturbance through tillage enhances the thermal benefits of plastic mulching. MCB and MCW significantly increased AAST, AEST, ASAT, and ESAT during the low spring months of March and April. This increase is primarily attributed to the greenhouse effect created by transparent or black plastic film, which effectively raises soil temperatures [6,27,28]. During the early growth stages of winter wheat, this effect is particularly beneficial, as the small canopy exposes most of the plastic-covered surface to solar radiation, allowing enhanced soil heating beneath the film. In contrast, NC treatments (NCB and NCW) significantly reduced soil temperatures during the rejuvenation and jointing periods. This reduction is largely due to the higher albedo of straw mulch in NC, which reflects solar radiation and limits heat penetration into the soil [6]. Moreover, the lower thermal conductivity of no-tillage soils slows heat transfer, causing ST to increase more gradually under solar radiation [29]. ST is a critical factor in regulating plant growth and development [30], and multiple studies have demonstrated that different mulching materials distinctly influence soil thermal regimes to maximize crop productivity [6]. Our findings indicated that variations in ST under MC and NC, with the same covering materials but different colors, produced greater ST dynamics (MCB and MCW). This is likely due to differing degrees of long-term soil disturbance between tilled (MC) and no-tillage (NC) systems. Previous studies report that plastic film mulching can effectively increase topsoil temperature (0–20 cm) through the choice of plastic film colour [17]. Black PE [31] and white transparent films [32] are commonly used to cover dryland crop soils, and their transmissivity and opacity determine the degree of solar radiation penetration. Transparent films can increase ST by 2.3–2.9 °C [17], while black films may reduce it by 1–2 °C [14], thereby modulating crop growth by altering soil temperature, particularly in the topsoil [4,33].

During our 22-year-long-term conservation tillage study (MC and NC), plastic films (MCB and MCW) optimized ST (AST) by 2–3 °C at 5–10 cm depths, more effectively diffusing heat than at deeper layers (20 cm). These findings align with prior studies indicating that no-tillage soils generally exhibit lower temperatures than tilled soils [34,35]. MCB and MCW maintained superior thermal conditions compared with NC, NCB, and NCW throughout the overwintering period. Their lower albedo and higher thermal conductivity, relative to NC, allow soil temperature to adjust progressively with solar radiation intensity, particularly in the afternoon and evening [36]. Additionally, MC soils had less surface cover than NC, and plastic film does not prevent water–atmosphere exchange, which enhances latent heat flux and further contributes to higher soil temperatures under MCB and MCW. These enhanced thermal conditions under MCB and MCW optimize root growth compared with NC. Previous studies have shown that mulching exerts a dual effect on soil hydrothermal conditions, warming during jointing stages and cooling during post stages [32,37]. Consistently, our study utilized the warming effect of plastic films from tillering to jointing stages, positively influencing the winter wheat root system, with the effect more pronounced under the tilled system. A three-year comparison of no-tillage with plastic re-mulching and reduced tillage with plastic mulching revealed clear differences in thermal regulation, vertical temperature gradients, accumulated soil temperature, and moisture distribution, particularly within the 5–25 cm layer, while neither year nor year × treatment interaction significantly influenced these outcomes [38]. Lower soil temperatures in no-tillage systems primarily result from crop residue insulation, reduced soil disturbance, and higher soil moisture, which collectively moderate soil temperature, making no-tillage soils cooler than tilled soils [39]. No-tillage increases surface (0–5 cm) temperature but fails to conduct heat efficiently to lower layers or maintain daytime warming due to higher soil bulk density and surface compaction, highlighting the importance of combining tillage with plastic mulching to optimize soil thermal conditions for crop growth.

Though our initial hypothesis proposed that film mulching would alleviate temperature constraints more effectively in no-till systems, the results did not support this expectation. Instead, stronger positive effects were observed under tilled conditions. This difference can be attributed to the contrasting soil physical properties (soil bulk density and soil moisture content) resulting from long-term management. In no-till plots, thick surface residues and higher bulk density reduced thermal conductivity and weakened the soil-warming effect of the mulch. In contrast, tilled soils had closer film–soil contact and higher heat transfer efficiency, which stabilized temperature in the 5–20 cm layer and promoted root growth and yield. These findings indicate that the benefits of PFM depend strongly on soil structure and residue conditions, and that complementary practices—such as shallow loosening or improved mulch design—may be needed to enhance thermal response in long-term no-till systems

4.2. Root Characteristics Response to PFM and Tillage System

The interaction between tillage and PFM played a decisive role in modifying soil thermal and physical environments, which in turn influenced root system development. Reduced soil bulk density under MC significantly amplified the effects of plastic mulching on ST and root weight density (RWD). Consequently, in tilled plots with lower bulk density, the application of plastic mulch increased both soil temperature and RWD compared with un-mulched conditions, resulting in greater biomass production and yield accumulation [43]. Optimized ST profiles under PFM within the tilled system also enhanced key root characteristics (RCs)—particularly RLD, RWD, and RSA—during the overwintering and early spring growth stages. These results support the hypothesis that combining tillage with PFM improves soil thermal conditions and accelerates root system establishment from March to April, when root growth is most sensitive to temperature [40].

Significant increases in RLD and RWD were observed in the top 0–20 cm soil layer, with the strongest effects in MCW and MCB treatments. These treatments provided warmer, well-aerated soil that promoted both horizontal and vertical root expansion, leading to improved resource capture. In contrast, no-tillage (NC) plots exhibited compacted soil structure, lower ST, and reduced root proliferation, consistent with findings from other conservation tillage studies [26,41]. Although most root biomass was concentrated in the upper 20 cm, the combined tillage and PFM treatments (MCW, MCB) facilitated greater root penetration into deeper layers, enhancing RSA and overall root efficiency. Root volume (RV) distribution remained relatively stable across treatments, suggesting that tillage and mulching primarily affected root density and surface area rather than total root volume [42].

Overall, the increase in ST and reduction in bulk density under MCW and MCB treatments were positively correlated with RLD, RWD, and RSA, and indirectly with yield attributes, highlighting the critical role of optimized soil thermal and structural conditions in improving root development and crop productivity. These findings confirm that tillage enhances the structural environment for root growth, while PFM improves the thermal regime, and that their combination provides synergistic benefits for winter wheat growth and yield formation [43,44].

4.3. RC Enhanced Yield and Yield Parameters

Plastic film mulching under long-term tilled conditions (MCW and MCB) significantly improved root characteristics by optimizing ST during the overwintering period, enhancing agronomic traits, and increasing aboveground dry matter (AGDM). Compared with no-tillage, PFM, MCW, and MCB promoted topsoil root extension, which has a greater impact on yield than deeper root growth under mulching [43]. Mulch coverage improved grain yield and substantially increased straw yield [45]. In this study, adding PFM to MC enhanced both grain and straw yield, whereas long-term no-tillage treatments (NCW and NCB) experienced reduced yields. Extreme soil moisture under full-film mulching can cause yield decline due to water stress; however, film mulching helps regulate soil moisture at different growth stages to optimize yields [46]. Tillage combined with plastic film is an effective strategy for improving crop productivity, and plough tillage with PFM achieves higher yields while reducing carbon footprint [47]. Early-stage PFM maintained the highest soil moisture content, supporting winter wheat yield and AGDM. Biomass allocation reflects root-to-shoot ratio, and since winter wheat growth is mostly aboveground, PFM on MC enhanced AGDM. These results align with previous studies, which have shown that PFM improves root–shoot coordination, reduces redundant root growth, and lowers the root-to-shoot ratio, thereby promoting yield [48–50].

4.4. Relationships Among the ST, RC, and Yield Agronomical Parameters

Strong positive correlations between ST and RLD and RWD indicate that warmer soils, particularly during early and middle growth stages, enhance root proliferation and biomass accumulation [51]. This aligns with established agronomic theory, as elevated ST generally increases root metabolic activity and nutrient absorption, facilitating robust early crop establishment and improved resource-use efficiency [6]. Conversely, the negative correlation between morning average ST (MAST) and aboveground dry matter (AGDM) suggests that excessive thermal stress during critical developmental stages may reduce shoot biomass despite enhanced root growth [52]. Depth-specific ST effects were observed, with shallow layers (AST10) significantly promoting root growth, emphasizing the importance of managing soil temperature via practices such as mulching and conservation tillage to improve resource-use efficiency and crop resilience under changing climate conditions [53].

Positive correlations between grain parameters and AAST, EAST, ASAT, and ESAT highlight the role of sufficient thermal accumulation for optimal grain filling, consistent with previous studies on temperature’s influence in crop physiology [54]. Moderate-depth ST (AST10 and AST20) further supports root growth, enhancing nutrient uptake and water-use efficiency critical for resilience under variable climates [55]. Strong correlations between RLD, RWD, and grain yield underline the role of extensive, dense root systems in nutrient and water acquisition, directly contributing to yield [56,57]. Moderate positive correlations with root surface area (RSA) suggest that greater root–soil contact enhances resource absorption and crop performance under stress [58]. Negative correlations with root diameter (RD) indicate that finer roots are more efficient in resource uptake due to higher surface-area-to-volume ratios [59]. These findings emphasize optimizing RCs through agronomic strategies, including irrigation, conservation tillage, and breeding programs, to enhance root architecture, improve yield stability, crop resilience, and resource-use efficiency [60].

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the interactions among soil temperature, root system development, and wheat yield under 22 years of conservation tillage practices, incorporating tillage (MC) and no-tillage (NC) with plastic film mulching during the overwintering period. Compared with NC, MC alone influenced root development and yield, but its effects on soil temperature during overwintering and the root system were limited across the soil depth. Plastic film mulching produced contrasting effects depending on long-term tillage history. In tilled systems (MCB and MCW), mulching stabilized soil thermal conditions at the 5–20 cm depth, enhanced root growth, and significantly improved yield. In contrast, in no-till systems (NCB and NCW), mulching was associated with cooler soils, constrained root development, and reduced yield. These findings indicate that overwintering temperatures indirectly restrict wheat yield potential through their effects on root and shoot system development, thereby influencing soil resource capture and biomass accumulation. They also highlight the critical interaction between tillage history and mulching efficacy, suggesting that successful temperature management in no-till systems requires complementary practices such as subsoiling or improved mulch design to overcome inherent soil physical limitations.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1902605-01 and 2021YFD1901002-2). The first author was financially supported by the Chinese Government Scholarship (CGS) and the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, PR, China.

References

- Plaza, C.; Courtier-Murias, D.; Fernández, J.M.; Polo, A.; Simpson, A.J. Physical, chemical, and biochemical mechanisms of soil organic matter stabilization under conservation tillage systems: A central role for microbes and microbial by-products in C sequestration. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2012, 57, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, M.A.; Al-Kaisi, M. Strip-tillage effect on seedbed soil temperature and other soil physical properties. Soil and Tillage Research 2004, 80, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Turner, N.C.; Li, X.-G.; Niu, J.-Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Chai, Q. Ridge-Furrow Mulching Systems—An innovative technique for boosting crop productivity in semiarid Rain-Fed environments. In Advances in agronomy, 2012; pp 429–476. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L. Root size, distribution and soil water depletion as affected by cultivars and environmental factors. Field Crops Research 2009, 114(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Derpsch, R.; Kienzle, J. Overview of the worldwide spread of conservation agriculture. Available online: https://doaj.org/article/5ebd222c01734909b194ec21684a1c96.

- Li, R.; Hou, X.; Jia, Z.; Han, Q.; Ren, X.; Yang, B. Effects on soil temperature, moisture, and maize yield of cultivation with ridge and furrow mulching in the rainfed area of the Loess Plateau, China. Agricultural Water Management 2012, 116, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Martre, P.; Zhao, Z.; Ewert, F.; Maiorano, A.; Rötter, R.P.; Kimball, B.A.; Ottman, M.J.; Wall, G.W.; White, J.W.; et al. The uncertainty of crop yield projections is reduced by improved temperature response functions. Nature Plants 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Malhi, S.S.; Vera, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of rainfall harvesting and mulching technologies on water use efficiency and crop yield in the semi-arid Loess Plateau, China. Agricultural Water Management 2008, 96(3), 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Quan, H.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H.; Ding, D.; Siddique, K.H.M. Responses of winter wheat yield and water productivity to sowing time and plastic mulching in the Loess Plateau. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 289, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Z.; Wollmann, C.; Schaefer, M.; Buchmann, C.; David, J.; Tröger, J.; Muñoz, K.; Frör, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? The Science of the Total Environment 2016, 550, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Luo, S.; Chen, X.; Li, S. Source–Sink Capacity Responsible for Higher Maize Yield with Removal of Plastic Film. Agronomy Journal 2013, 105(3), 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughrin, J.H.; Kasperbauer, M.J. Aroma of Fresh Strawberries Is Enhanced by Ripening over Red versus Black Mulch. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2001, 50(1), 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.M.; Moreno, A. Effect of different biodegradable and polyethylene mulches on soil properties and production in a tomato crop. Scientia Horticulturae 2008, 116(3), 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikwe, M.A.N.; Mbah, C.N.; Ezeaku, P.I.; Onyia, V.N. Tillage and plastic mulch effects on soil properties and growth and yield of cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) on an ultisol in southeastern Nigeria. Soil and Tillage Research 2006, 93(2), 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, J.A.; Masiunas, J.B. The effects of black plastic mulch and weed control strategies on herb yield. HortScience 1991, 26(5), 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldoma, I.M.; Li, M.; Zhang, F.; Li, F.-M. Alternate or equal ridge–furrow pattern: Which is better for maize production in the rain-fed semi-arid Loess Plateau of China? Field Crops Research 2016, 191, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J.-Y.; Xiong, Y.-C.; Nguluu, S.N.; Li, F.-M. Ridge-furrow mulching system in semiarid Kenya: A promising solution to improve soil water availability and maize productivity. European Journal of Agronomy 2016, 80, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Gao, Z.; Wu, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Cui, G.; Yu, M.; Yan, G.; et al. Impact of increased temperature on spring wheat yield in northern China. Food and Energy Security 2021, 10(2), 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Hu, C.; Oenema, O. Responses of cereal yields and soil carbon sequestration to four Long-Term Tillage practices in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2022, 12(1), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Ren, T.; Hu, C. Tillage and residue removal effects on soil carbon and nitrogen storage in the North China Plain. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2010, 74(1), 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Hu, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y. Tillage and residue management effects on soil carbon and CO2 emission in a wheat–corn double-cropping system. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2008, 83(1), 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Mawodza, T.; Atkinson, B.S.; Atkinson, J.A.; Sturrock, C.J.; Whalley, R.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Cooper, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; et al. The effects of soil compaction on wheat seedling root growth are specific to soil texture and soil moisture status. Rhizosphere 2023, 29, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittelkow, C.M.; Liang, X.; Linquist, B.A.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Lee, J.; Lundy, M.E.; Van Gestel, N.; Six, J.; Venterea, R.T.; Van Kessel, C. Productivity limits and potentials of the principles of conservation agriculture. Nature 2014, 517(7534), 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Timilsina, A.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C.; Dong, W. Long-term conservation tillage practices affect total carbon and contribute to the formation of soil aggregates in the semi-arid North China Plain. Soil Use and Management; 2024; 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimento, C.; Amaducci, S. Characterization of fine root system and potential contribution to soil organic carbon of six perennial bioenergy crops. Biomass and Bioenergy 2015, 83, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaddeghi; Mahboubi, A.A.; Safadoust, A. Short-term effects of tillage and manure on some soil physical properties and maize root growth in a sandy loam soil in western Iran. Soil and Tillage Research 2008, 104, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, R.; Shi, X.; Wei, H.; Sun, G.; Li, F.-M.; Zhang, F. The effects of plastic film mulching and straw mulching on licorice root yield and soil organic carbon content in a dryland farming. The Science of the Total Environment 2022, 826, 154113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Li, F.-M. A regional evaluation of plastic film mulching for improving crop yields on the Loess Plateau of China. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2017, 248, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.L.; Daigh, A.L.M. Tillage practices alter the surface energy balance – A review. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 195, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.R.; Gawith, M. Temperatures and the growth and development of wheat: A review. European Journal of Agronomy 1999, 10(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M. Ridge-furrow mulching with black plastic film improves maize yield more than white plastic film in dry areas with adequate accumulated temperature. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2018, 262, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhan, A.; Bu, L.; Zhu, L.; Luo, S.; Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Li, S.; Hill, R.L.; Zhao, Y. Understanding dry matter and nitrogen accumulation for High-Yielding Film-Mulched Maize. Agronomy Journal 2014, 106(2), 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hou, R.; Gong, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effects of 11 years of conservation tillage on soil organic matter fractions in wheat monoculture in Loess Plateau of China. Soil and Tillage Research 2009, 106(1), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C.F.; Tan, C.; Welacky, T.W.; Oloya, T.O.; Hamill, A.S.; Weaver, S.E. Red clover and tillage influence on soil temperature, water content, and corn emergence. Agronomy Journal 1999, 91(1), 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmaniyan, K.; Zhou, W. Soil Temperature Associated with Degradable, Non-Degradable Plastic and Organic Mulches and Their Effect on Biomass Production, Enzyme Activities and Seed Yield of Winter Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2008, 32, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Perry, K.B.; Ristaino, J.B. Estimating temperature of mulched and bare soil from meteorological data. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 1996, 81, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Pei, D.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, S.L. Effects of straw mulching on soil temperature, evaporation and yield of winter wheat: Field experiments on the North China Plain. Annals of Applied Biology 2007, 150(3), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Chai, Q.; Guo, Y.; Fan, H.; Fan, Z.; Hu, F.; Zhao, C.; Yu, A.; Coulter, J.A. No tillage with plastic re-mulching maintains high maize productivity via regulating hydrothermal effects in an arid region. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata, D.; Rajan, N.; Mowrer, J.; Casey, K.; Schnell, R.; Hons, F. Long-term tillage effect on with-in season variations in soil conditions and respiration from dryland winter wheat and soybean cropping systems. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L. Black film mulching and plant density influencing soil water temperature conditions and maize root growth. Vadose Zone Journal 2018, 17(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Root phenotypes for improved nutrient capture: An underexploited opportunity for global agriculture. New Phytologist 2019, 223(2), 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, B.; Niu, J. Soil water status and root distribution across the rooting zone in maize with plastic film mulching. Field Crops Research 2013, 156, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, Z.; Pan, W.; Liao, Y.; Li, T.; Qin, X. Response of root traits to plastic film mulch and its effects on yield. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 209, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Mulching improves yield and water-use efficiency of potato cropping in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2018, 221, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Chai, Q.; Guo, Y.; Feng, F.; Zhao, C.; Yu, A.; Hu, F. Analysis of Leaf Area Index Dynamic and Grain Yield Components of Intercropped Wheat and Maize under Straw Mulch Combined with Reduced Tillage in Arid Environments. Journal of Agricultural Science 2016, 8(4), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Huo, Z.; Wang, H. Simulation for response of crop yield to soil moisture and salinity with artificial neural network. Field Crops Research 2011, 121(3), 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Lai, H.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Yang, D.; Li, X. The impacts of soil tillage combined with plastic film management practices on soil quality, carbon footprint, and peanut yield. European J of Agr. 2023, 148, 126881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jin, C.; Guan, D.; Wang, Q.; Wang, A.; Yuan, F.; Wu, J. The effects of simulated nitrogen deposition on plant root traits: A meta-analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2015, 82, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, H.; Wen, X.; Han, J.; Liao, Y. Optimizing planting pattern and nitrogen application rate improves grain yield and water use efficiency for rain-fed spring maize by promoting root growth and reducing redundant root growth. Soil and Tillage Research 2022, 220, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Yue, S.; Luo, Z.; Li, S. Understanding of maize root responses to changes in water status induced by plastic film mulching cultivation on the Loess Plateau, China. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 301, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregitzer, K.S.; King, J.S.; Burton, A.J.; Brown, S.E. Responses of tree fine roots to temperature. New Phytologist 2000, 147(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Prueger, J.H. Temperature extremes: Effect on plant growth and development. Weather and Climate Extremes 2015, 10, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304(5677), 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Schlenker, W.; Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 2011, 333(6042), 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Moreira, A. The role of mineral nutrition on root growth of crop plants. In Advances in agronomy, 2011; pp 251–331. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Steep, cheap and deep: An ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Annals of Botany 2013, 112(2), 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, A.P.; Richards, R.A.; Chatrath, R.; Misra, S.C.; Prasad, S.V.S.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Christopher, J.; Watt, M. Traits and selection strategies to improve root systems and water uptake in water-limited wheat crops. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63(9), 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, G.L.; Dong, Z.; McLean, G.; Doherty, A.; Messina, C.; Schussler, J.; Zinselmeier, C.; Paszkiewicz, S.; Cooper, M. Can changes in canopy and/or root system architecture explain historical maize yield trends in the U.S. corn belt? Crop Science 2009, 49(1), 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.G.; Kirkegaard, J.A. The distribution and abundance of wheat roots in a dense, structured subsoil – implications for water uptake. Plant Cell & Environment 2009, 33, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Root phenotypes for improved nutrient capture: An underexploited opportunity for global agriculture. New Phytologist 2019, 223(2), 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, W.-H.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Cao, C.-Y.; Li, K.-J. Artificial Warming from Late Winter to Early Spring by Phased Plastic Mulching Increases Grain Yield of Winter Wheat. ACTA AGRONOMICA SINICA 2016, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the established experimental field plot design with 22 years of long-term conservation tillage practices on MC and NC. Where, a = MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC); b = MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC), and (c) non-plastic film mulching (MC and NC). Fig 01. (B) Method for root and soil sampling.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the established experimental field plot design with 22 years of long-term conservation tillage practices on MC and NC. Where, a = MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC); b = MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC), and (c) non-plastic film mulching (MC and NC). Fig 01. (B) Method for root and soil sampling.

Figure 2.

Monthly average air temperature (maximum, minimum, and average) and precipitation during the winter wheat crop growing season (2023-2024) in the experimental field area.

Figure 2.

Monthly average air temperature (maximum, minimum, and average) and precipitation during the winter wheat crop growing season (2023-2024) in the experimental field area.

Figure 3.

a. Dynamics of soil temperatures (

0C) at depths of 0-40 cm in the afternoon, evening, and morning during the overwintering period of the winter wheat growing season. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). The vertical bars represent the LSD = 0.05 (n = .

Figure 3b (Afternoon). Dynamics of soil temperatures (

0C) at depths of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 cm in the afternoon, during the overwintering period of the winter wheat growing season. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). The vertical bars represent the LSD = 0.05 (n = 3).

Figure 3b (Evening). Dynamics of soil temperatures (

0C) at depths of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 cm in the evening, during the overwintering period of the winter wheat growing season. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). The vertical bars represent the LSD = 0.05 (n = 3).

Figure 3b (Morning). Dynamics of soil temperatures (

0C) at depths of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 cm in the evening, during the overwintering period of the winter wheat growing season. MC (moldboard ploughing with crushed maize stalks mixed into the soil) and NC (no-tillage with crushed maize stalks left on the soil surface), MCB (black plastic film mulching on MC, and NCB (black plastic film mulching on NC), MCW (white plastic film mulching on MC, and NCW (white plastic film mulching on NC). The vertical bars represent the LSD = 0.05 (n = 3).

Figure 3.

a. Dynamics of soil temperatures (