Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Basic Information

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measurement Description

2.2. Best Estimate and Measurement Uncertainty

2.3. Selection of the Reference Plane

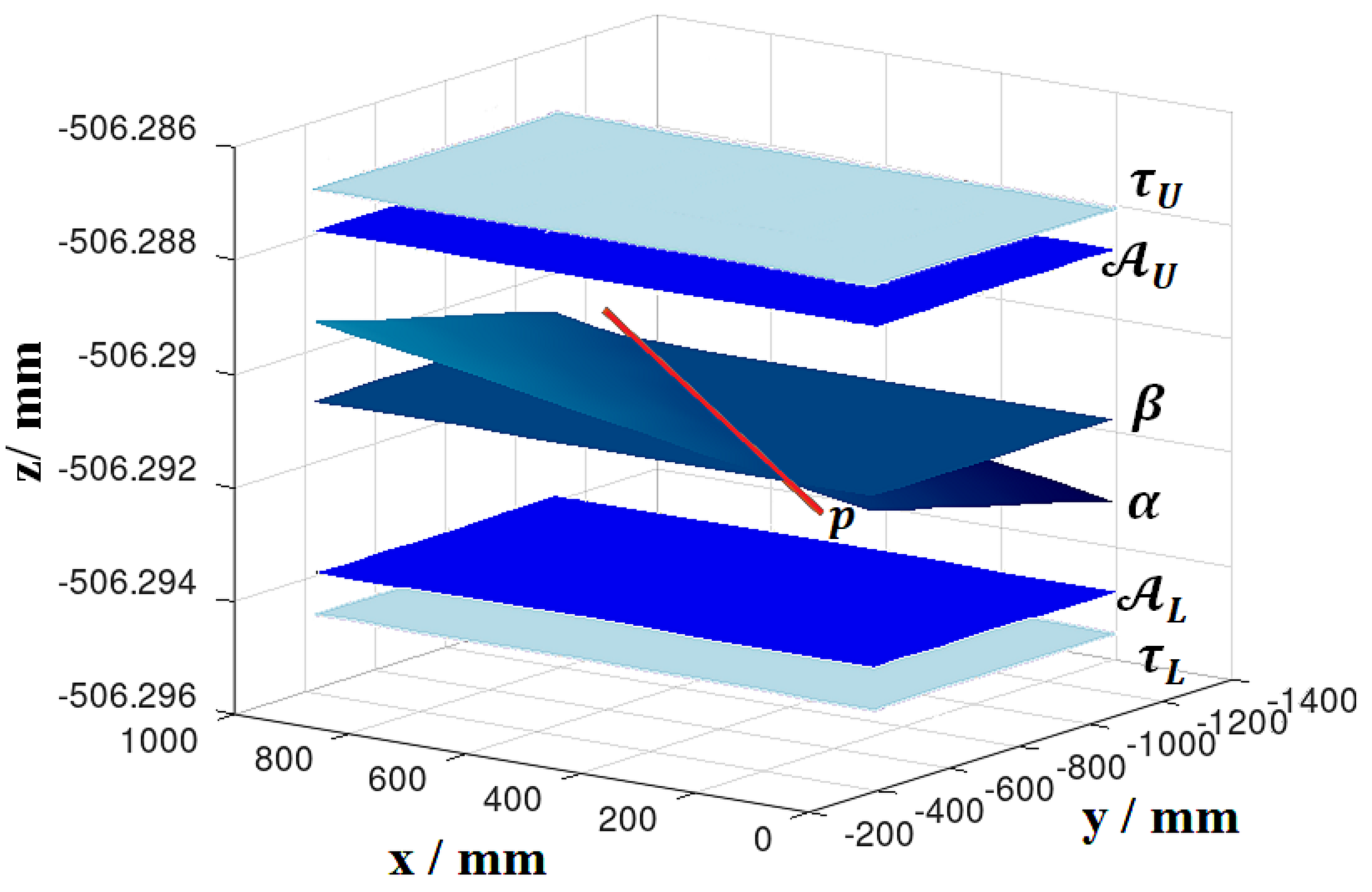

2.4. Tolerance Plane and Acceptance Plane

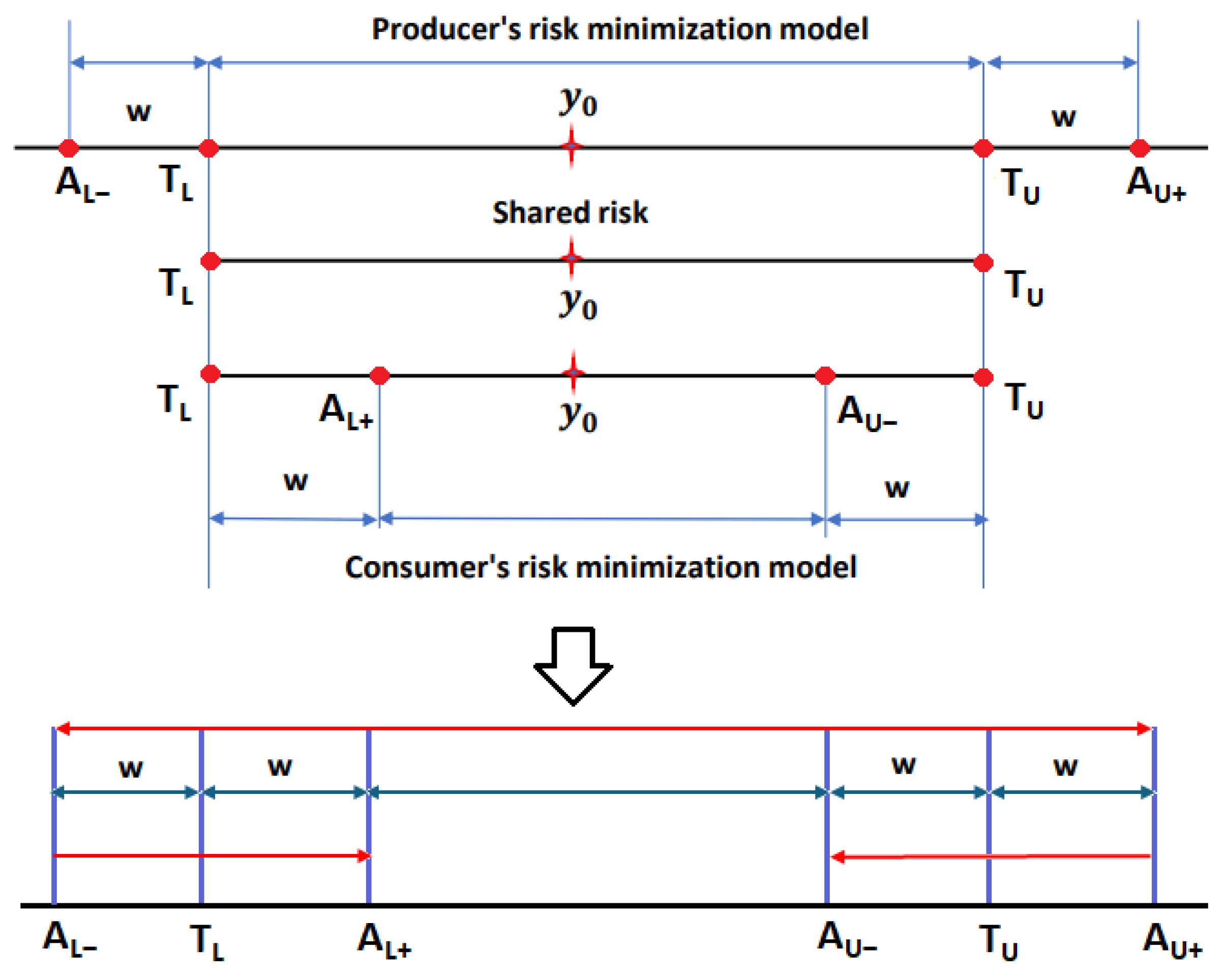

2.5. Risk Calculation

3. Results

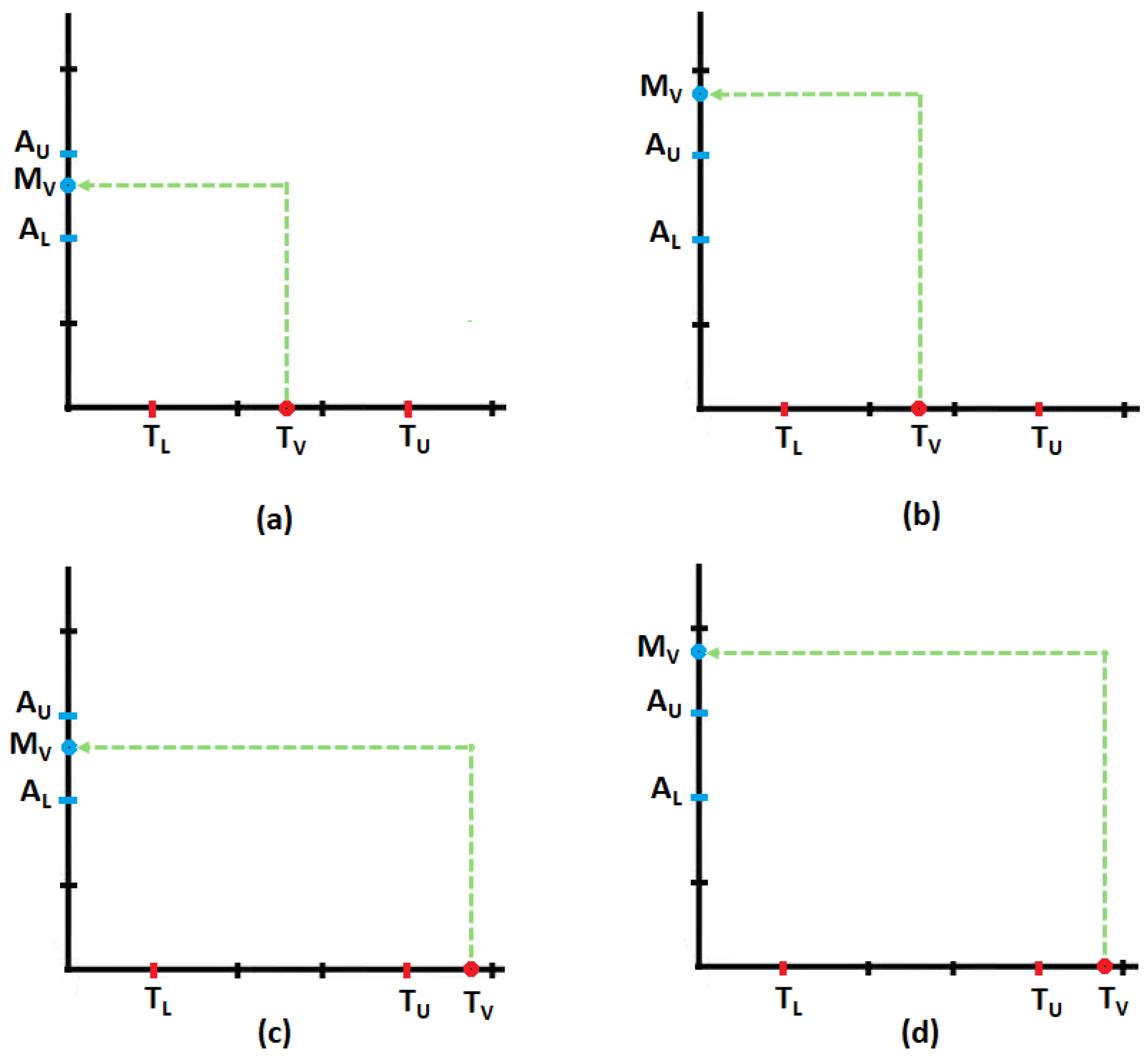

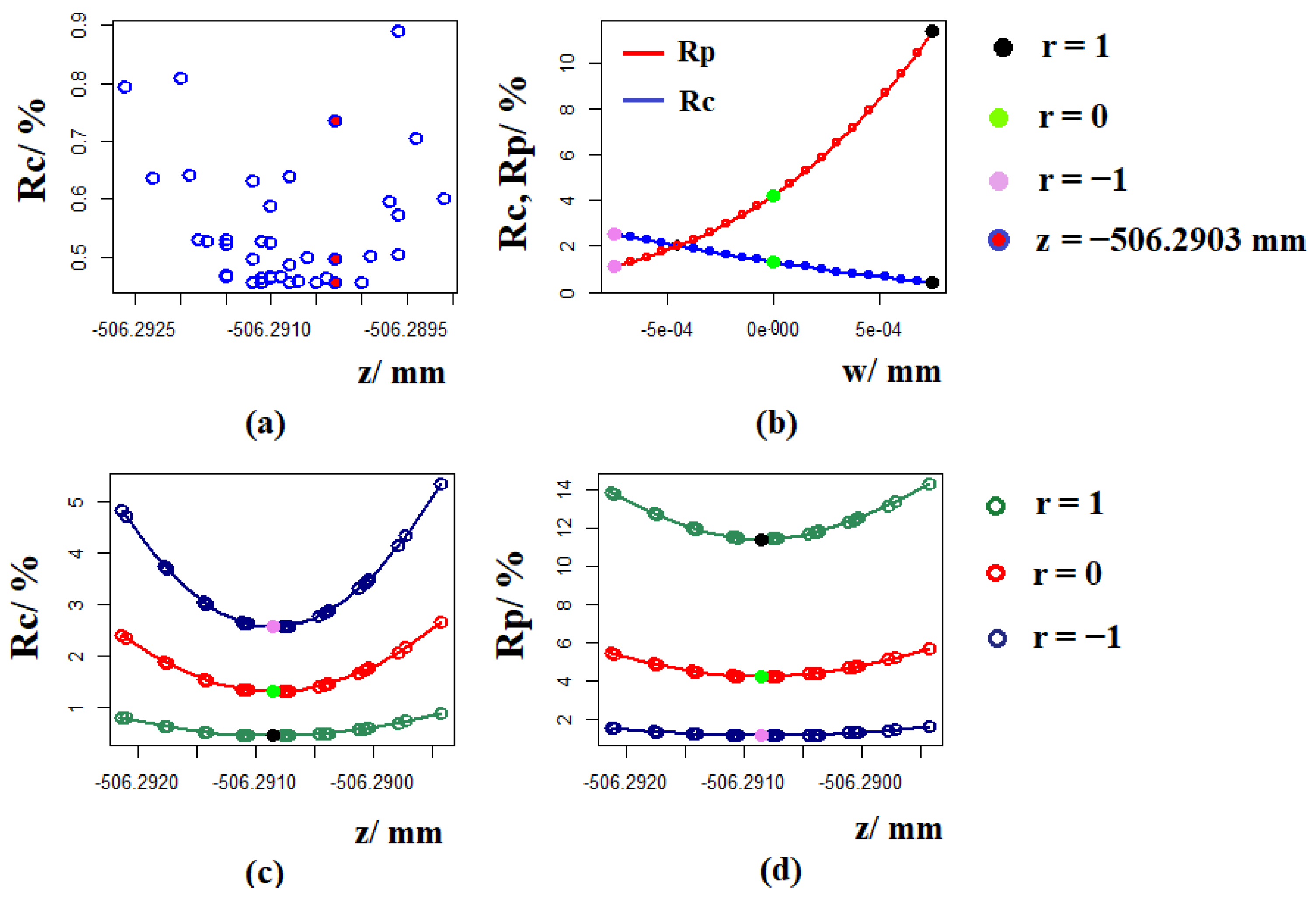

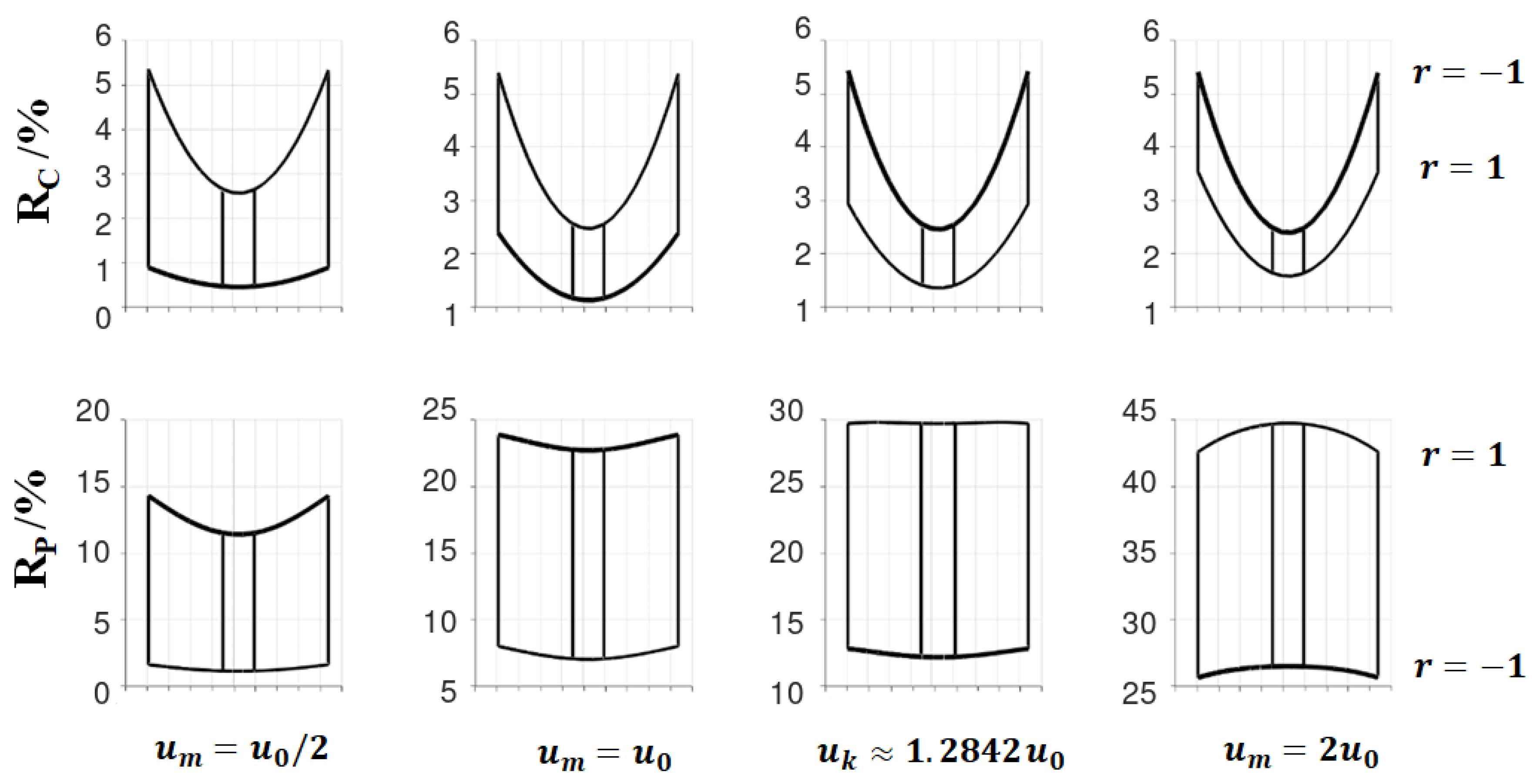

3.1. Risk Curves

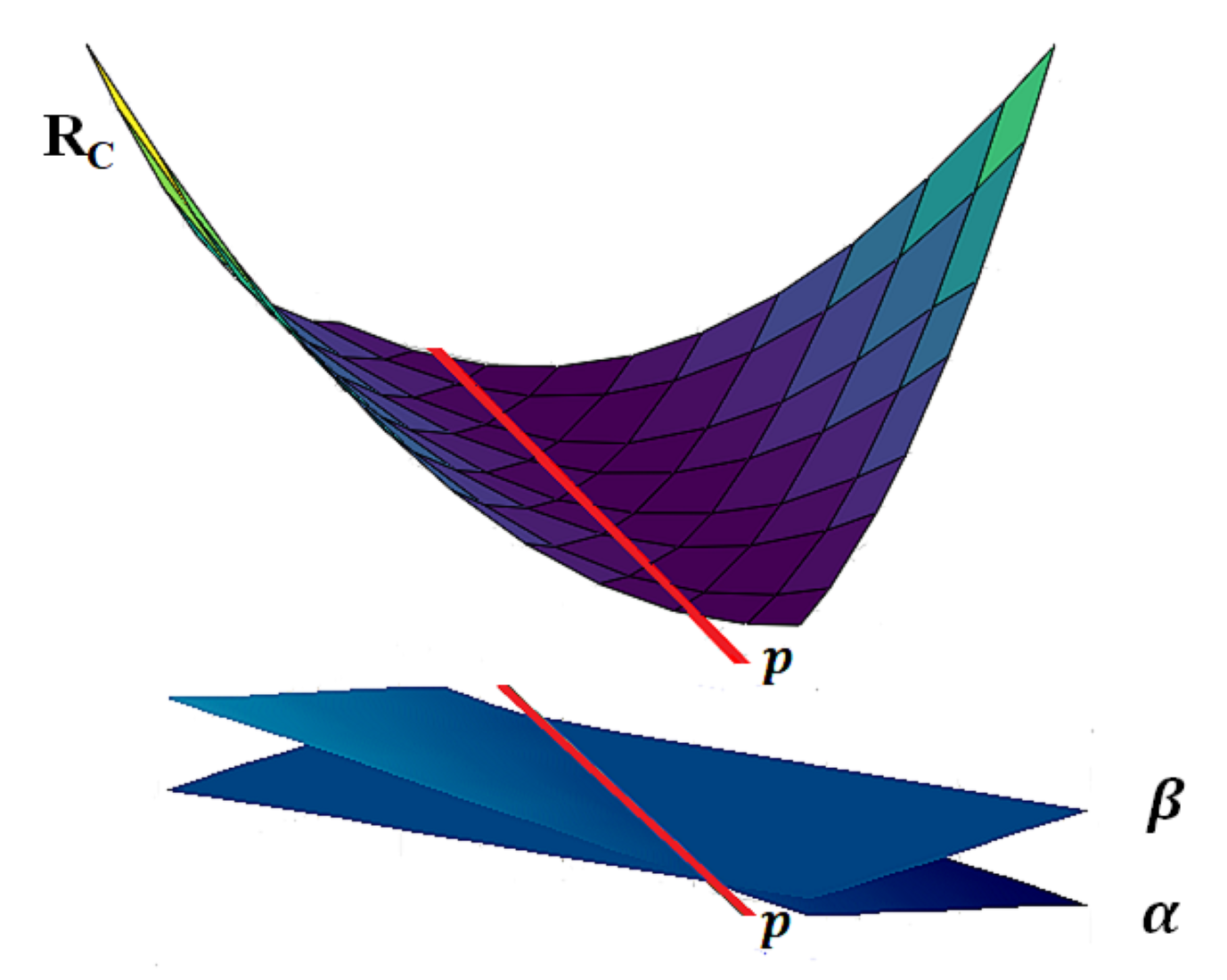

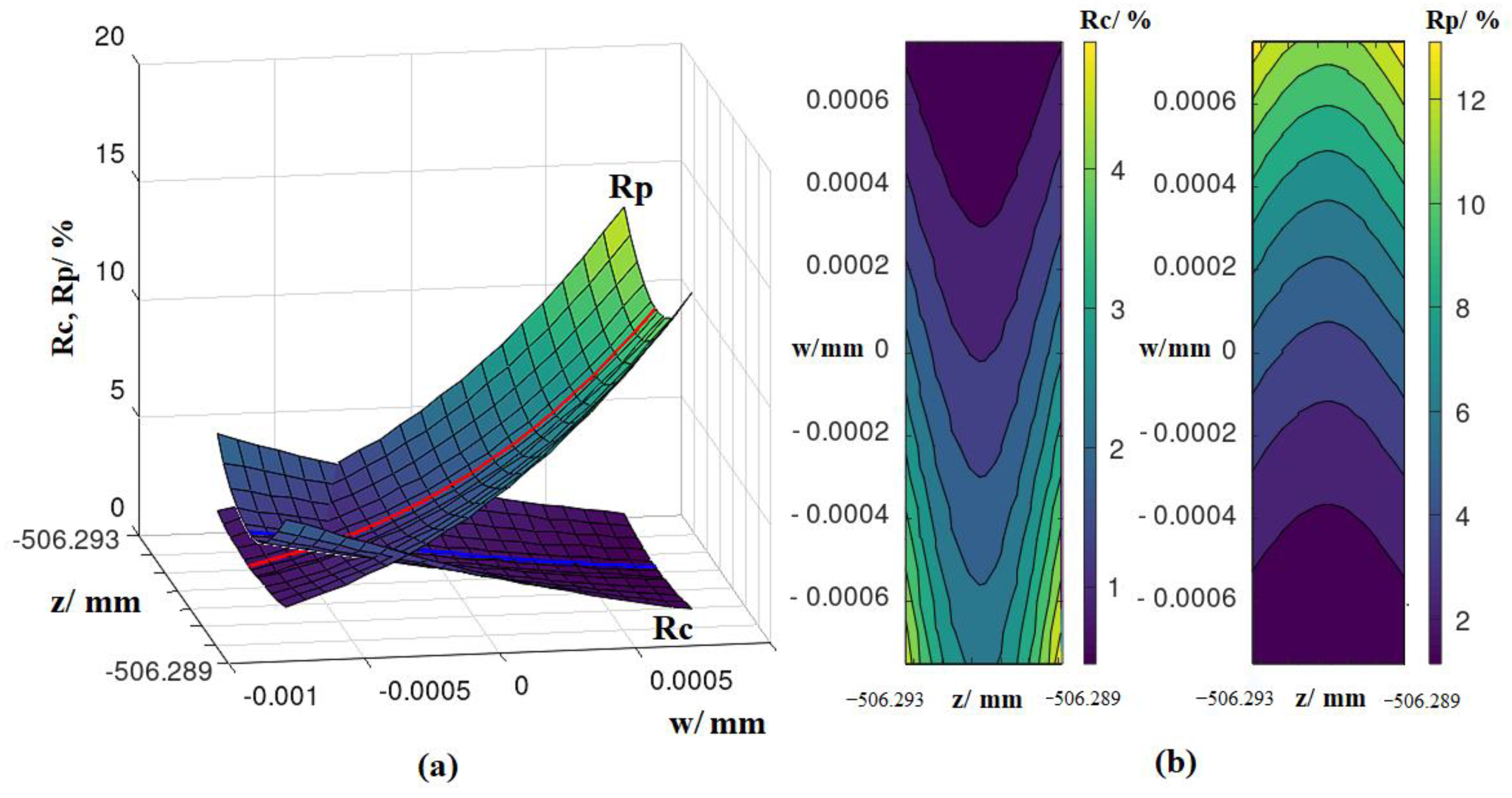

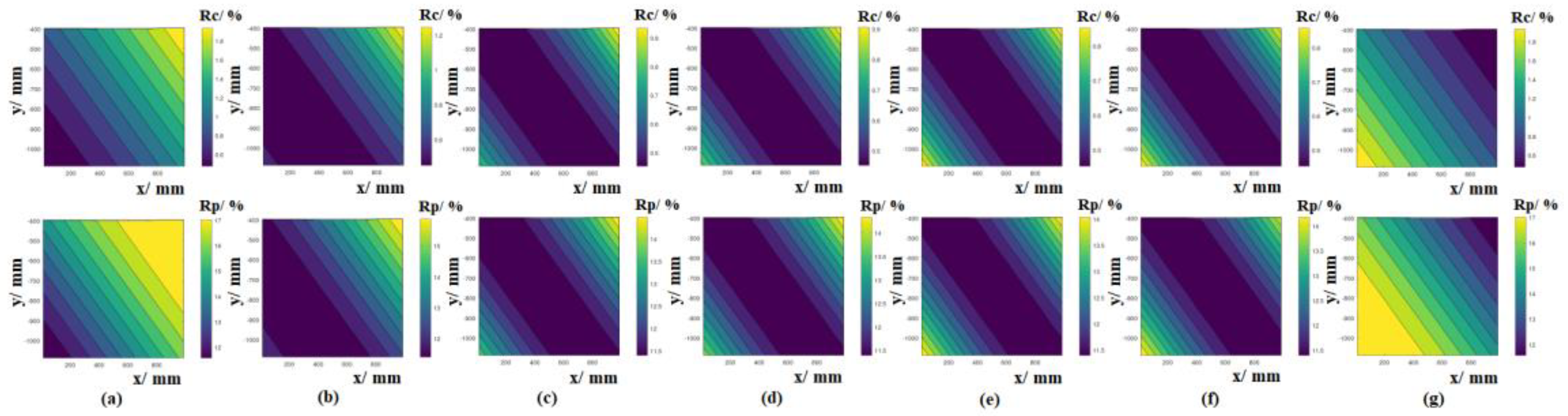

3.2. Risk Surfaces

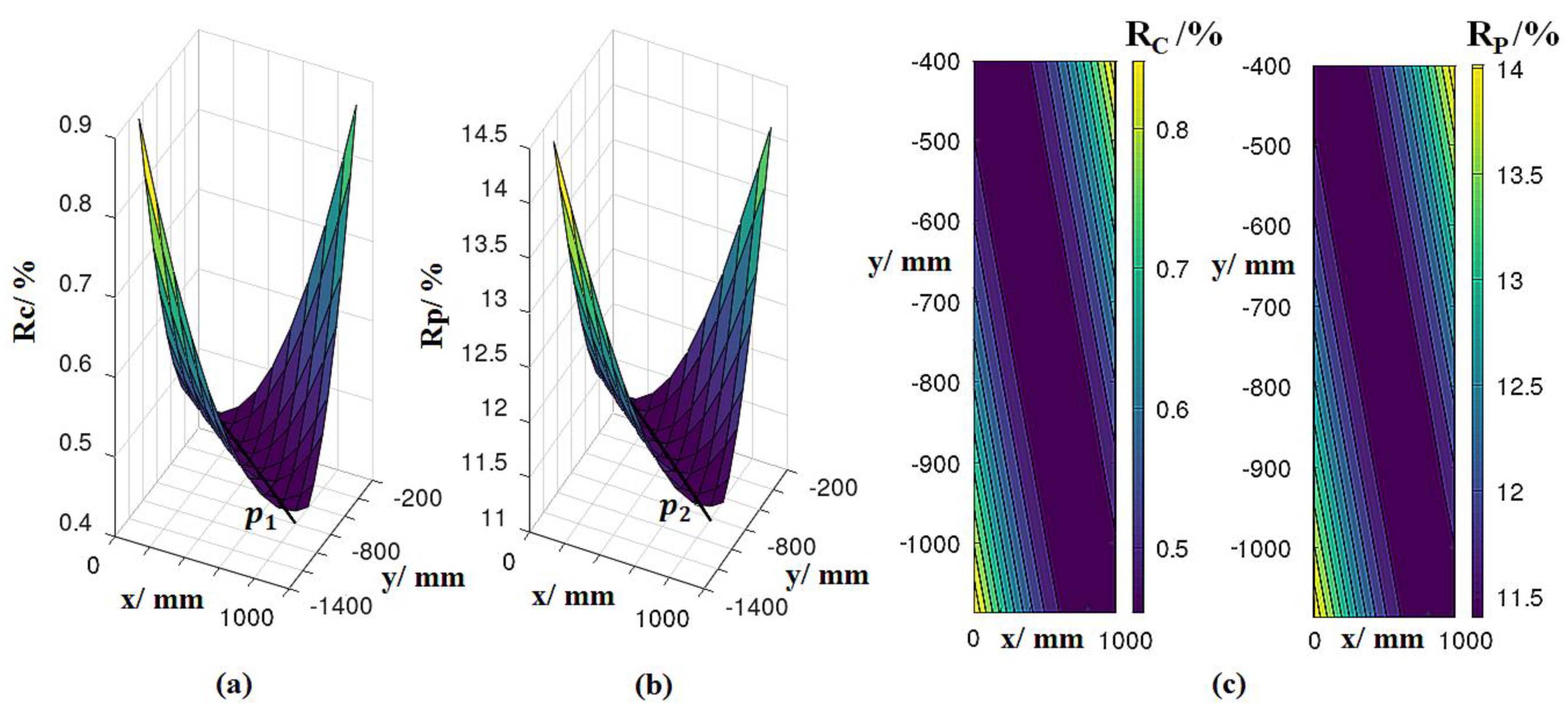

3.3. Risk Spaces

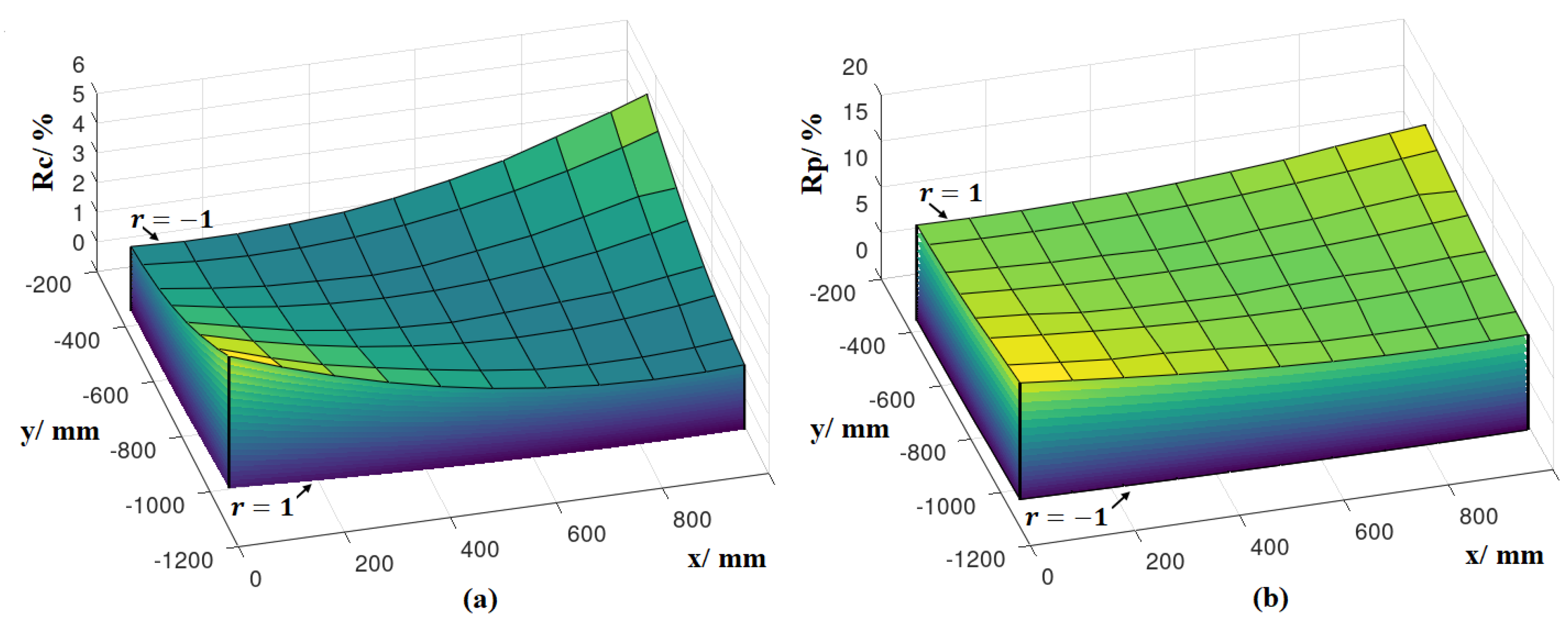

3.4. Dependence of the Results on the Choice of the Reference Plane

3.5. Dependence of Results on Measurement Uncertainty

4. Model Evaluation

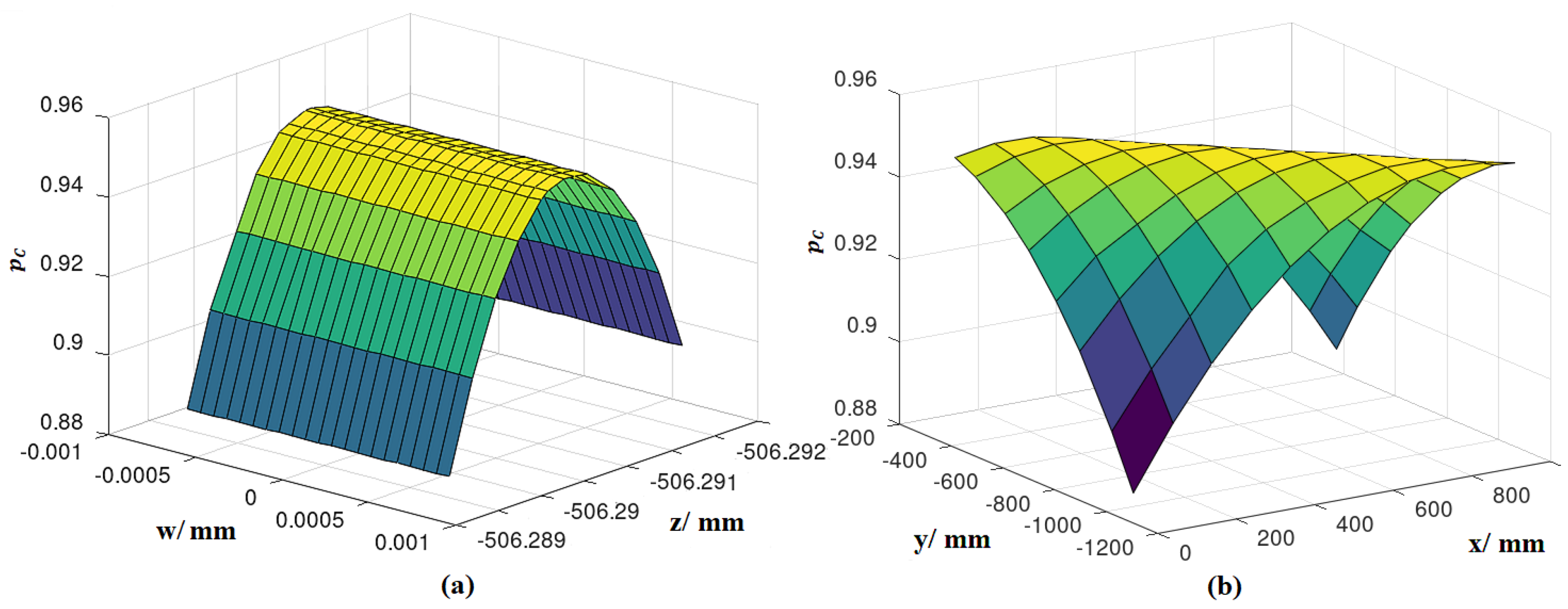

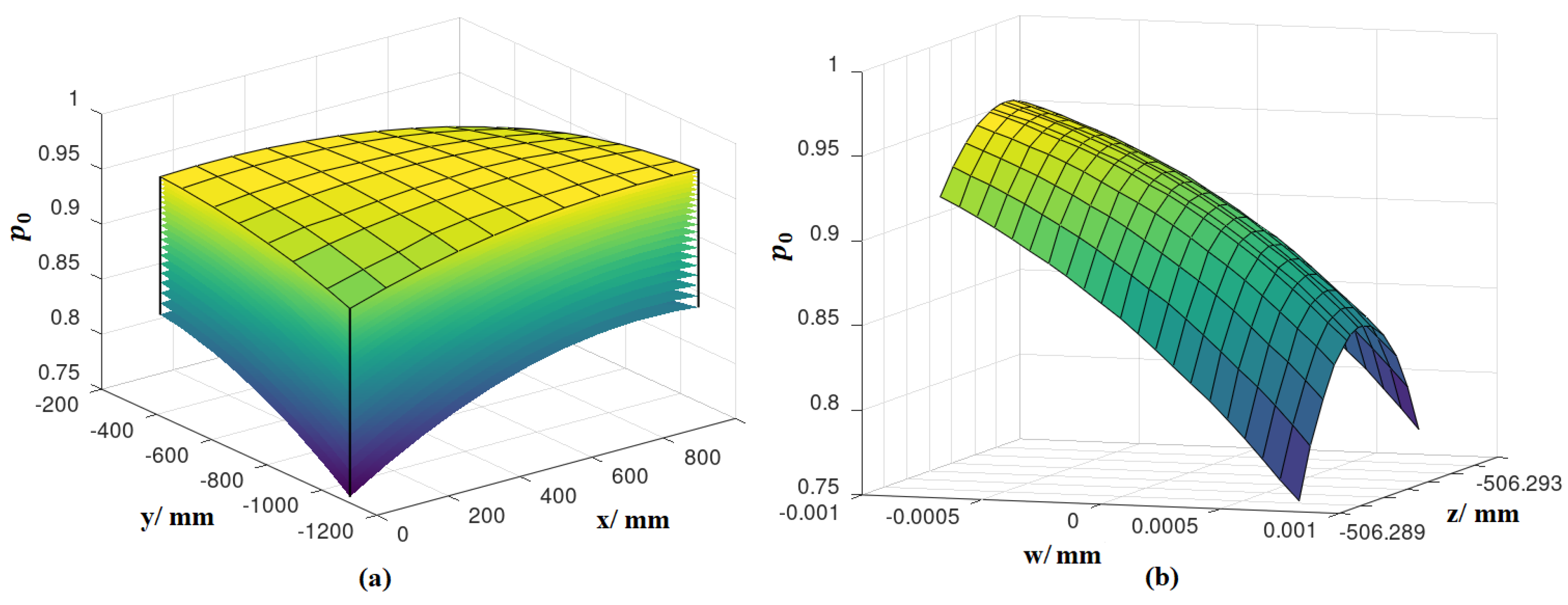

4.1. Conformance Probability

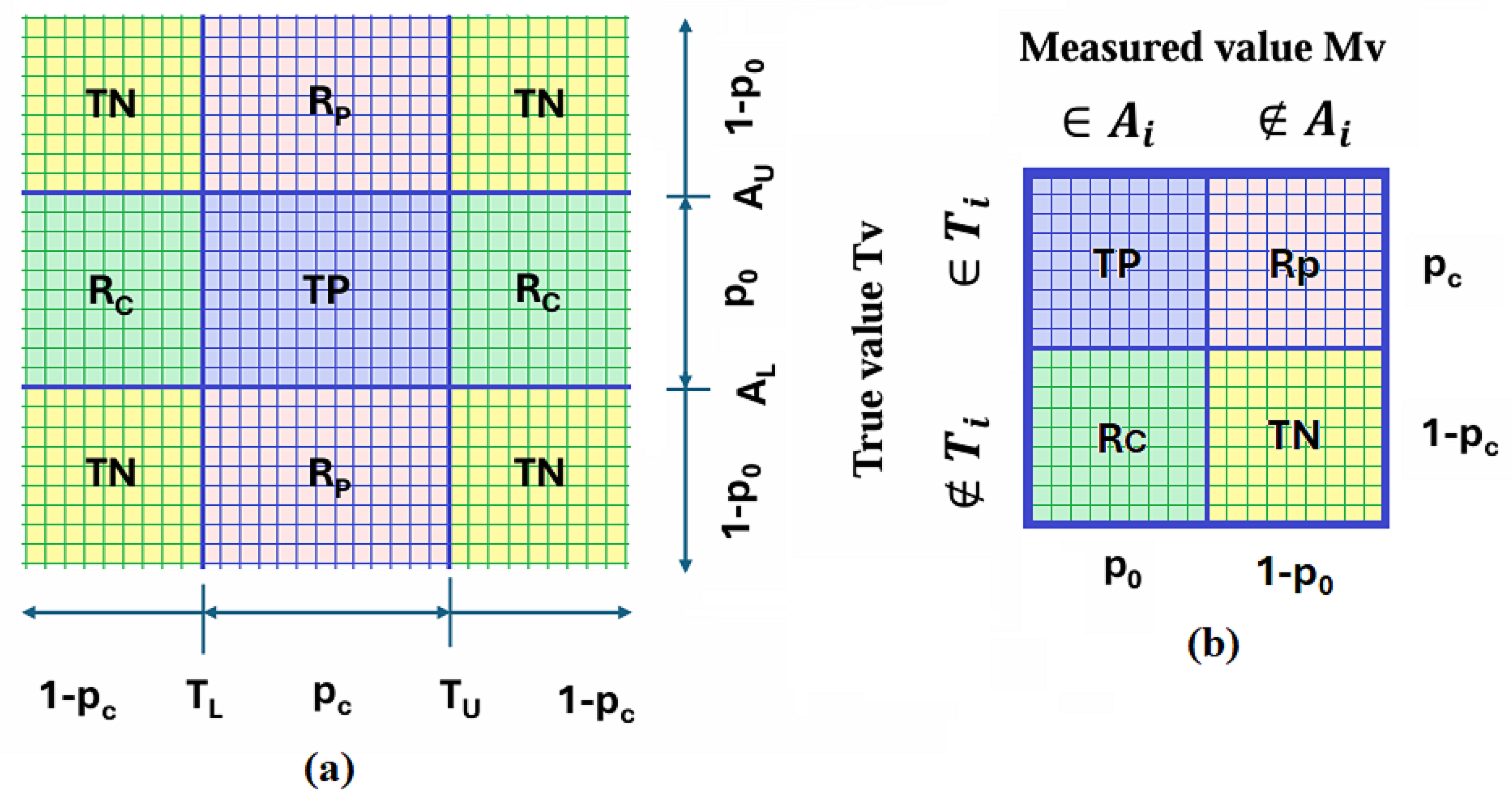

4.2. Confusion Matrix

4.3. Probability of Frequent and Rare Events

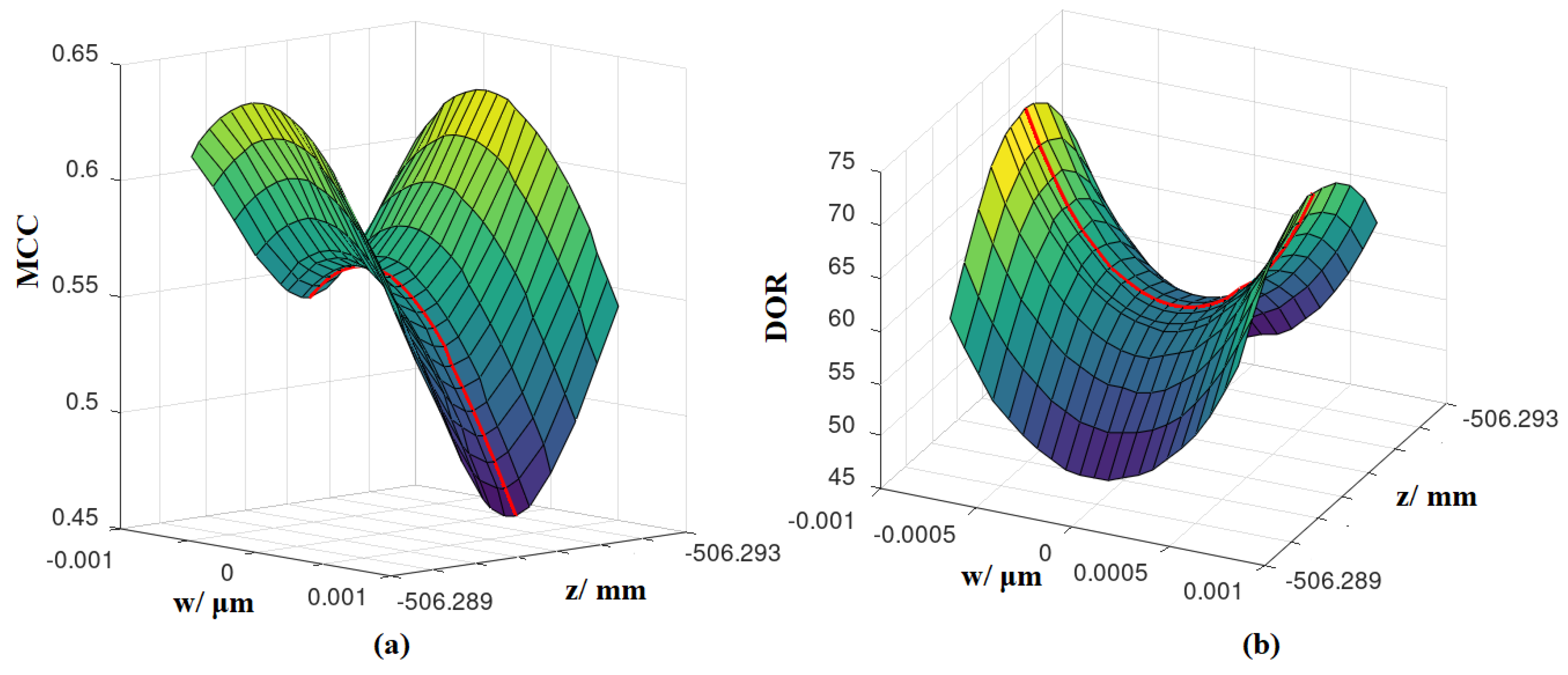

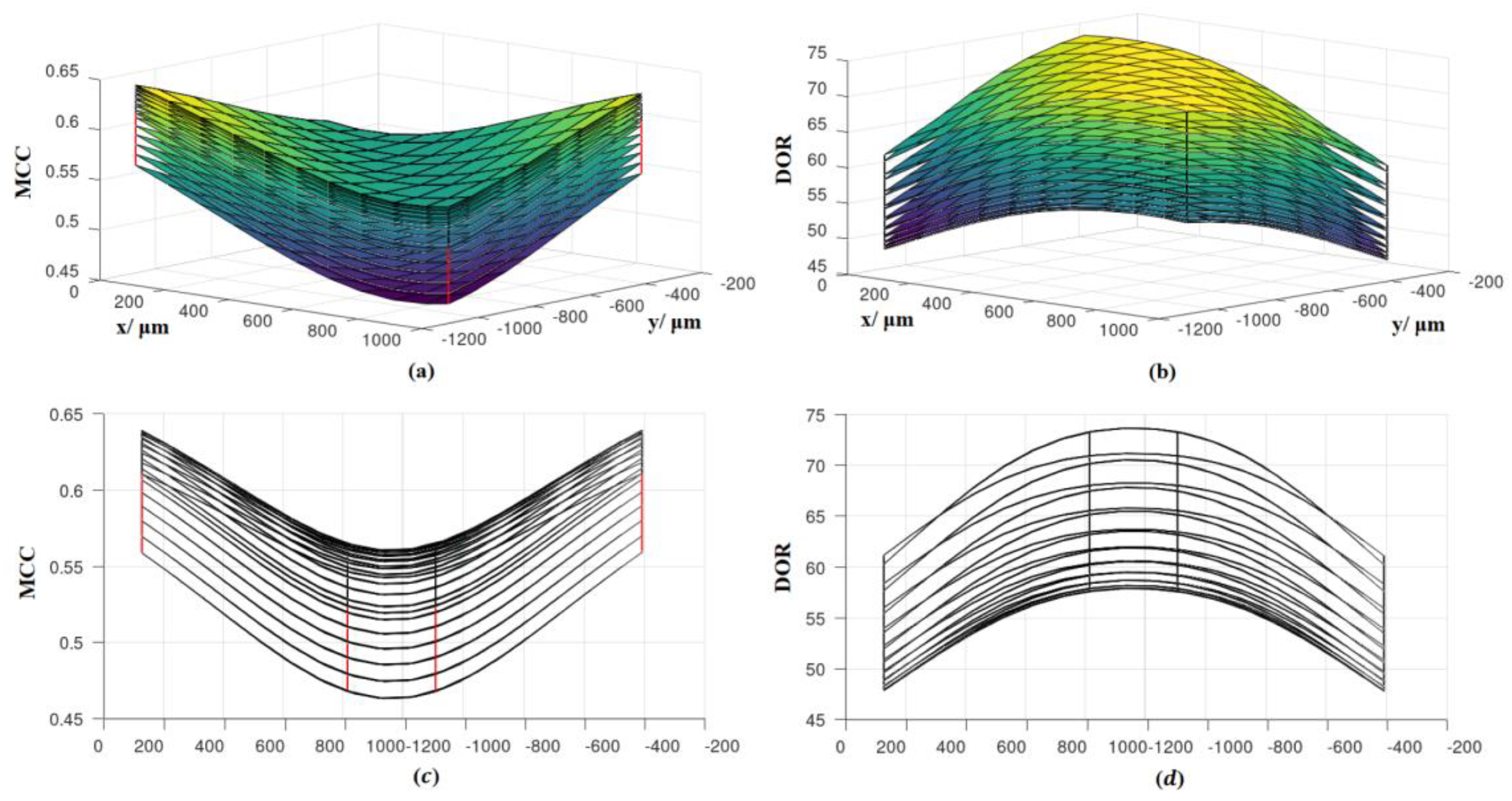

4.4. Curves, Surfaces and Spaces of Metrics Associated with the Confusion Matrix

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuselman, I.; Pennecchi, F.R.; Da Silva, R.J.; Hibbert, D.B. IUPAC/CITAC Guide: Evaluation of risks of false decisions in conformity assessment of a multicomponent material or object due to measurement uncertainty (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93, 113–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolano, G.; Boucher, P.; Degiovanni, I.P.; Losero, E.; Genovese, M.; Ruo-Berchera, I. Quantum conformance test. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabm3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biserka, R.; Horvatić Novak, A.; Keran, Z. Impact of the quality of measurement results on conformity assessment. In Proceedings of the 29th DAAAM International Symposium on Intelligent Manufacturing and Automation, Zadar, Croatia, 24–27 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.R.S.; Lourenço, F.R. Measurement uncertainty evaluation and risk of false conformity assessment for microbial enumeration tests. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 189, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILAC–G8:09/2019. Guidelines on Decision Rules and Statements of Conformity. 2019. Available online: https://ilac.org/publications-and-resources/ilac-guidance-series/ (accessed on August 29, 2025).

- Sedeek, M.A.; Elerian, F.A.; Abouelatta, O.B.; AbouEleaz, M.A. Decision-making Approach to Reduce the Risk of Measurement Uncertainty for Product Size. Manosura Eng. J. 2024, 49, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, A.; Fischer, N.; Smith, I.; Harris, P.; Pendrill, L. Risk calculations for conformity assessment in practice. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Metrology, Paris, France, 24–26 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koucha, Y.; Forbes, A.; Yang, Q. A Bayesian conformity and risk assessment adapted to a form error model. Meas:Sens. 2021, 18, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennecchi, F.R.; Kuselman, I.; Di Rocco, A.; Hibbert, D.B.; Sobina, A.; Sobina, E. Specific risks of false decisions in conformity assessment of a substance or material with a mass balance constraint–A case study of potassium iodate. Meas. 2021, 173, 108662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt da Silva, R.J.; Lourenço, F.; Hibbert, D.B. Setting multivariate and correlated acceptance limits for assessing the conformity of items. Anal. Lett. 2022, 55, 2011–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM, IEC, IFCC, ILAC, ISO, IUPAC, IUPAP, and OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM 100:2008. [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, L.R. Using measurement uncertainty in decision-making and conformity assessment. Metrologia 2014, 51, S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Separovic, L.; Lourenco, F.R. Measurement uncertainty and risk of false conformity decision in the performance evaluation of liquid chromatography analytical procedures. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 171, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Magnusson, B. Eurachem/CITAC Guide: Use of Uncertainty Information in Compliance Assessment. 2021. Available online: https://www.eurachem.org/index.php/publications/guides/uncertcompliance (accessed on August 29, 2025).

- Xue, Z.; Mou, X.; Sun, H.; Cao, C.; Xu, B. A Protocol for Conformity and Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical Product by High Performance Liquid Chromatography Based on Measurement Uncertainty. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Separovic, L.; Simabukuro, R.S.; Couto, A.R.; Bertanha, M.L.G.; Dias, F.R.; Sano, A.Y.; Caffaro, A.M.; Lourenco, F.R. Measurement uncertainty and conformity assessment applied to drug and medicine analyses–a review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 53, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A. The Cost of Wrong decisions. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference Laboratory Competence-Brijuni 2024, Brijuni, Croatia, 23–25 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Volodarsky, E.T.; Kosheva, L.O.; Klevtsova, M.O. Approaches to the Evaluation of Conformity Taking into Account the Uncertainty of the Value of the Monitored Parameter. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th International Conference on Advanced Optoelectronics and Lasers (CAOL), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 6–8 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM, IEC, IFCC, ILAC, ISO, IUPAC, IUPAP, and OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — The role of measurement uncertainty in conformity assessment. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM 106:2012. [CrossRef]

- Volodarskyi, Y.; Kosheva, L.; Kozyr, O. Reducing the Impact of Measurement Uncertainty in Conformity Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2023 XXXIII International Scientific Symposium Metrology and Metrology Assurance (MMA), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 7–11 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runje, B.; Horvatić Novak, A.; Razumić, A.; Piljek, P.; Štrbac, B.; Orošnjak, M. Evaluation of Consumer and Producer Risk in Conformity Assessment Decision. In Proceedings of the 30th DAAAM International Symposium “Intelligent Manufacturing & Automation”, Zadar, Croatia, 23–26 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, D.B.; Korte, E.H.; Örnemark, U. Metrological and quality concepts in analytical chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 2021). Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93(9), 997–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, I. A Bayesian approach to the consumer’s and producer’s risks in measurement. Metrologia 1999, 36, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodarsky, E.T.; Kosheva, L.O.; Klevtsova, M.O. The Role Uncertainty of Measurements in the Formation of Acceptance Criteria. In Proceedings of the 2019 XXIX International Scientific Symposium" Metrology and Metrology Assurance"(MMA), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 6–9 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIPM, IEC, IFCC, ILAC, ISO, IUPAC, IUPAP, and OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — Supplement 1 to the “Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement” — Propagation of distributions using a Monte Carlo method. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM 101:2008. [CrossRef]

- Iuculano, G.; Nielsen, L.; Zanobini, A.; Pellegrini, G. The principle of maximum entropy applied in the evaluation of the measurement uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2007, 56, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.B.; Chen, X.H.; Li, H.L.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Jiang, R.; Lü, J.; Fu, H.D. Analysis and comparison of Bayesian methods for measurement uncertainty evaluation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 1, 7509046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, G.; Fouskakis, D.; Liseo, B.; Ntzoufras, I. Prior distributions for objective Bayesian analysis. Bayesian Anal. 2018, 13, 627–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caticha, A.; Preuss, R. Maximum entropy and Bayesian data analysis: Entropic prior distributions. Phys. Rev. E. 2004, 70, 046127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folye, D. K.; Scharfenaker, E. Bayesian Inference and the Principle of Maximum Entropy. Am. Stat. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, A.; Kay, M. Prior setting in practice: Strategies and rationales used in choosing prior distributions for Bayesian analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, B. From historical data to priors. In Proceedings of the Biopharmaceutical Section, Joint Statistical Meetings, American Statistical Association, Miami Beach, Florida, USA, 30 July–4 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Separovic, L.; de Godoy Bertanha, M.L.; Saviano, A.M.; Lourenço, F.R. Conformity decisions based on measurement uncertainty—a case study applied to agar diffusion microbiological assay. J. Pharm. Innov. 2020, 15, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B. Data Modelling in Risk Assessment. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference Laboratory Competence 2022, Cavtat, Croatia, 9–12 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B. Selection of an Appropriate Prior Distribution in Risk Assessment. In Proceedings of the 33rd International DAAAM Virtual Symposium “Intelligent Manufacturing & Automation”, Vienna, Austria, 27–28 October 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toczek, W.; Smulko, J. Risk Analysis by a Probabilistic Model of the Measurement Process. Sensors 2021, 21, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennecchi, F.R.; Kuselman, I.; Di Rocco, A.; Hibbert, D.B.; Semenova, A.A. Risks in a sausage conformity assessment due to measurement uncertainty, correlation and mass balance constraint. Food Control, 2021, 125, 107949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, L.P.; Silva, V.F.; Bassi, M.; de Oliveira, E.C. Risk assessment in monitoring of water analysis of a Brazilian river. Mol. 2022, 27, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Separovic, L.; Saviano, A.M.; Lourenço, F.R. Using measurement uncertainty to assess the fitness for purpose of an HPLC analytical method in the pharmaceutical industry. Meas. 2018, 119, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Prado Pereira, W.; Carvalheira, L.; Lopes, J.M.; de Aguiar, P.F.; Moreira, R.M.; e Oliveira, E.C. Data reconciliation connected to guard bands to set specification limits related to risk assessment for radiopharmaceutical activity. Heliyon, 2023, 9, e22992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, F.G.; de Andrade Ferreira, A.; Silva, G.M.; Freire, T.A.; Costa, M.R.; de Morais, E.T.; Guzzo, J.V.P.; de Oliveira, E.C. Measurement Uncertainty and Risk of False Compliance Assessment Applied to Carbon Isotopic Analyses in Natural Gas Exploratory Evaluation. Mol. 2024, 29, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis Medeiros, K.A.; da Costa, L.G.; Bifano Manea, G.K.; de Moraes Maciel, R.; Caliman, E.; da Silva, M.T.; de Sena, R.C.; de Oliveira, E.C. Determination of total sulfur content in fuels: A comprehensive and metrological review focusing on compliance assessment. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 54, 3398–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Samardžija, M.; Kurtela, M.; Keran, Z.; Runje, B. Risk Evaluation for Coating Thickness Conformity Assessment. Mater. 2023, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuselman, I.; Pennecchi, F.; da Silva, R.J.; Hibbert, D.B. Conformity assessment of multicomponent materials or objects: Risk of false decisions due to measurement uncertainty–A case study of denatured alcohols. Talanta, 2017, 164, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuselman, I.; Pennecchi, F.R.; Da Silva, R.J.; Hibbert, D.B. Risk of false decision on conformity of a multicomponent material when test results of the components’ content are correlated. Talanta, 2017, 174, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.J.; Pennecchi, F.R.; Hibbert, D.B.; Kuselman, I. Tutorial and spreadsheets for Bayesian evaluation of risks of false decisions on conformity of a multicomponent material or object due to measurement uncertainty. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Sys. 2018, 182, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.D.; Lourenço, F.R. Definition of multivariate acceptance limits (guard-bands) applied to pharmaceutical equivalence assessment. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 222, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.D.; Lourenço, F.R. Multivariate guard-bands and total risk assessment on multiparameter evaluations with correlated and uncorrelated measured values. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 60, e23564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A.; Lisjak, D.; Štrbac, B. Risk assessment for non-centered models in metrology. In Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific Conference MMA-Flexible Technologies, Novi Sad, Serbia, 24–26 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puydarrieux, S.; Pou, J.M.; Leblond, L.; Fischer, N.; Allard, A.; Feinberg, M.; El Guennouni, D. Role of measurement uncertainty in conformity assessment. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Metrology (CIM2019), Paris, France, 24–26 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Lisjak, D.; Kolar, D. Metrics Related to Confusion Matrix as Tools for Conformity Assessment Decisions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A. Risk Assessment for Linear Regression Models in Metrology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A. Risk Assessment Procedure for Calibration. Teh. glas. 2025, 19(si1), 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A. Risk assessment for calibration: The non-linearized case. In Proceedings of the 2025 IMEKO Joint Conference TC8–TC11–TC25, Torino, Italy, 14–177 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, D.; Runje, B.; Razumić, A.; Lisjak, D.; Štrbac, B. Risk assessment for linear regression models in metrology: hypothetical cases. In Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific Conference MMA-Flexible Technologies, Novi Sad, Serbia, 24–26 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranisavljev, M.; Razumić, A.; Štrbac, B.; Runje, B.; Horvatić Novak, A.; Hadžistević, M. Ispitivanje ravnosti granitnog stola KMM primenom konvencionalne i koordinatne metrologije. In Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific Conference Conference on Mechanical Engineering Technologies and Applications (COMETa2022), Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 17–19 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, G.; Petro, S. Geometric tolerance evaluation: A discussion on minimum zone fitting algorithms. Precis. Eng. 2008, 32, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlovački, V.; Hadžistević, M.; Štrbac, B.; Delić, M.; Kamberović, B. Evaluating minimum zone flatness error using new method—Bundle of plains through one point. Prec. Eng. 2016, 43, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 1101:2017, Geometrical product specifications (GPS) – Geometrical tolerancing – Tolerances of form, orientation, location and run-out, International Organization for Standardization, 2017.

- Shen, Y.; Ren, J.; Huang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L. Surface form inspection with contact coordinate measurement: a review. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 2023, 5, 022006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahwi, S.Z.; Amer, M.A.; Abdou, M.A.; Elmelegy, A.M. On the calibration of surface plates. Meas. 2013, 46, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrbac, B.; Radlovački, V.; Spasić-Jokić, V.; delić, M.; Hadžistević, M. The Difference Between GUM and ISO/TC 15530-3 Method to Evaluate the Measurement Uncertainty of Flatness by a CMM. Mapan, 2017, 32, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Fu, S.; Huang, F. Research on the uncertainties from different form error evaluation methods by CMM sampling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 43, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standard: BS 817:1988 Specification for Surface Plates. British Standard Institution, 1988.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Borchers, H.W. Pracma: Practical Numerical Math Functions. R Package Version 2.4.2/r532. Available online: https://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/optimist/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Eaton, J.W.; Bateman, D.; Hauberg, S.; Wehbring, R. GNU Octave Version 8.4.0 Manual: A High-Level Interactive Language for Numerical Computations. Available online: https://www.gnu.org/software/octave/doc/v8.4.0/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Chicco, D.; Tötsch, N.; Jurman, G. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is more reliable than balanced accuracy, bookmaker informedness, and markedness in two-class confusion matrix evaluation. BioData Min., 2021, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juras, J.; Pasarić, Z. Application of tetrachoric and polychoric correlation coefficients to forecast verification. Geofizika, 2006, 23, 59–82. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/4211 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Grandini, M.; Bagli, E.; Visani, G. Metrics for multi-class classification: An overview. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, S.; Imas, S.S.; Djatna, T.; Atikah, T.D. Comparative analysis using various performance metrics in imbalanced data for multi-class text classification. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhan, M.; Algarni, A.; Alouane, M.T.H. Imbalanced data problem in machine learning: A review. IEEE Access, 2025, 13, 13686–13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Labels | Metrics | mm | ||

| 1 | Accuracy | ↘* | 6.375 | 7.5 |

| 2 | F1 score | ↘ | 6.75 | 7.5 |

| 3 | BA | ↗ | 7.5 | 6.75 |

| 4 | G-mean | ↗ | 7.5 | 6.3 |

| 5 | BM | ↗ | 7.5 | 6.75 |

| 6L | kappa | ↗ | 7.5→3.75 | — |

| 6R | kappa | ↘ | 2.625 | 7.5 |

| 7L | MCC | ↗ | 7.5→3 | — |

| 7R | MCC | ↘ | 2.25 | 7.5 |

| 8L | DOR | ↘ | 7.5→0 | — |

| 8R | DOR | ↗ | — | 0.375→7.5 |

| Intersection of intervals | Labels | mm | ||

| 1–5, 6L, 7L, 8L | 6.375→3.75 | — | ||

| 1–5, 6R, 7R, 8L | 2.25→0 | — | ||

| 1–5, 6R, 7R, 8R | — | 0.375→6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).