1. Introduction

Health literacy is a determinant of an individual and population health: it affects how people can access, receive, assess and act on health-related information to make sound choices, engage in healthy behaviours and manoeuvre health systems throughout the life cycle. Health literacy has since been reshaped since the seminal formulation by Nutbeam (2000) to incorporate interactive abilities (communication about health) and critical abilities (the ability to evaluate and use health information to gain more control over determinants of health). Increasing health literacy in childhood and adolescence, when decisions and habits are established, is thus a fundamental educational and health-related concern (Simonsen et al., 2021).

The importance of schools as a location where health literacy can be developed on a population-wide scale is unique. Natural opportunities to scaffold functional, interactive and critical health literacies exist given the regular contact between students and curriculum structures, and through the social environment of schools. However, traditional school health programs tend to be based on one-size-fits-all teaching, restricted time in the classroom and didactic methods that are not only fail to attract the different kinds of learners but also in producing long term behavioural change. Simultaneously, the quantity and density of accessible health information, in particular, on the Internet, have augmented the cognitive load placed on youth to assess the sources and make evidence-based decisions, escalating the necessity of the pedagogies that develop higher-order health literacy competencies (Paakkari & Okan, 2020).

Meanwhile, the sphere of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies is transforming the educational practice. The new affordances of personalization, immediate formative feedback, simulation-based practice, and early identification of those learners who can receive targeted support can be provided by AI-driven tools, such as adaptive learning engines, recommender systems, conversational agents (chatbots), virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) simulation, and learning analytics. As pointed out by Luckin et al. (2022) and Abedini et al. (2021), AI systems may be used to promote personalization, teacher support, and increased learning outcomes. These developing skills fit the intricate needs of health literacy education in which individualized scaffolding, simulated practice conditions, and feedback (in a timely manner) is pedagogically beneficial (Chassignol et al., 2018).

On the policy level, key players in the world arena have indicated the possibilities and the obligations that come with educational AI and digital health. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO (2023) appreciates human-focused, equity-based use of AI in the education sector, and asks Member States to use these technologies to promote quicker, inclusive quality education and safeguard against potential threats to the privacy of learners. Likewise, in its Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025, the World Health Organization WHO (2020) also emphasizes the significance of the proper, accessible, and ethical use of digital interventions. These models emphasise the idea that AI-enabled pedagogical innovation needs to be supported by governance, teacher education, and privacy and fairness protections (Molina-Carmona & Garcia-Penalvo, 2024).

Although the conceptual connections between AI affordances and health literacy pedagogy fit together well, the particular landscape of AI applications to school-based health literacy is still disjointed. Current literature is usually either small-scale, domain-specific (such as chatbots to support adolescent sexual health, Ridgway et al., 2021), VR to support substance-use refusal skills (Di Giuseppe et al., 2022), and analytics to support adherence to physical-activity programs (Nguyen et al., 2023), or such as higher-education and clinical training settings instead of general school curriculum. Besides, the research evidence distribution is unequal: the majority is provided by high-income nations, whereas the low and middle-income settings, where the benefits of health literacy interactions can be significant, are underrepresented (Shankar, 2022). Repeat issues of data privacy, algorithmic bias, the digital divide, and preparedness of teachers to use AI tools in the most effective way are also present (Yu et al., 2020).

These gaps are filled in this narrative review using case illustration. It has three aims: (1) to map the breadth of AI applications implemented or tested to support facets of health literacy in schools worldwide, such as adaptive platforms, VR/AR simulations, conversational agents, learning analytics, and integrated systems; (2) synthesise the insights based on exemplary cases in a variety of geographic and socio-economic settings and (3) to draw cross-cutting conclusions about how researchers, practitioners, and policymakers can use AI to create equitable, effective, and ethically justifiable health literacy pedagogies in schools.

Combining global cases with conceptual frameworks (i.e., health literacy model, developed by Nutbeam, 2017) Universal Design of Learning (Rose et al., 2005; Jenkins et al., 2023) and principles of responsible AI, the review is expected to yield actionable knowledge: design heuristics (to be used by educators and instructional designers), governance issues (to be considered by school leaders), and an agenda (to be pursued by future researchers). By so doing, AI interventions at schools are not framed as some technological wonder but rather as pedagogical instruments that need to be designed, contextualised, and regulated in a way that is sustainable and purposeful contributing to the health and well-being of the youth.

1.1. Research Questions

Three research questions direct the review:

What are the examples of AI applications applied or tested to facilitate health literacy in schools around the world?

What are the lessons learned based on the illustrative cases of the AI-driven health literacy interventions in different contexts?

What is the cross-cutting implications of educators, policymakers and researchers to be able to promote ethical, equitable, and effective use of AI in health education?

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

The proposed study is designed as a narrative review consisting of case illustrations. Narrative reviews are suitable to recap fluid areas of research in which the literature remains heterogeneous and fragmented, which is the situation with AI applications in health literacy in schools (Greenhalgh et al., 2018). Narrative reviews provide more comprehensive inclusion, critical interpretation, and synthesis of conceptual and empirical knowledge, unlike systematic reviews, which have to be narrowly defined in terms of the intervention and outcomes in question. This allows identifying themes, contextual variations, and lessons learned across a variety of applications of AI, as it is very flexible.

The narrative review is supported by the illustrative cases based on the published studies and authoritative reports. Such instances are richly detailed and contextual to get beyond the abstract concepts to the actual real-world implementations of AI-driven pedagogies in schools across various social-economic and cultural settings (Snyder, 2019).

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

The search in literature was done in Scopus, PubMed, ERIC, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to find the articles about the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to the promotion of health literacy in the school setting, including articles published since 2015. The search terms were controlled and included artificial intelligence, machine learning, and chatbot plus the keywords involving health literacy, school health, and education. Peer-reviewed and grey literature (e.g., UNESCO, WHO, OECD) were also taken into account to make the world views inclusive.

The overall process and number of studies identified from each source are summarized in

Table 1.

This table summarizes the databases searched, key terms used, and number of included studies in Note: the narrative synthesis.

2.2.1. Databases Searched

The searches that were done systematically in the following academic databases were searched:

Scopus (interdisciplinary studies and education)

PubMed (Health and medical education)

ERIC (education -oriented research)

Web of Science (WoS)

Google Scholar (wide, grey literature)

2.2.2. Search Terms

Search terms were clustered into three areas and linked together through the use of Boolean operators:

AI-related terms: “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “chatbots,” “adaptive learning,” “virtual reality,” “augmented reality,” “learning analytics,” “intelligent tutoring.”

Health literacy terms: “health literacy,” “health education,” “health promotion,” “digital health literacy,” “preventive health.”

School context terms: “school,” “adolescent,” “secondary education,” “classroom,” “curriculum.”

Example query: “artificial intelligence” AND “health literacy” AND “school” OR “adolescent”.

2.2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Reports/studies conducted in the last 5 years (20152025).

Target school-going children (6-18 years).

Artificial intelligence tools were directly incorporated into health literacy or health education programs.

Articles in English.

Peer-reviewed journal articles, as well as trustworthy grey literature (policy briefs, NGO/UNESCO/WHO reports).

2.2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Research on clinical training (medical/nursing students).

Applications which do not pertain to health literacy or health promotion (e.g., AI to math or reading skills).

Opinion articles that lack evidence and conceptualization.

2.3. Selection Process

The literature search was conducted based on the best-practice guidelines of the narrative review (Ferrari, 2015). Abstracts and titles were filtered in terms of relevance. Reviews on inclusion and exclusion criteria were then conducted on the full-texts. In order to improve the credibility, two or more reviewers had to screen a sample of sources independently, and disagreements were solved by discussion.

The last group of sources consisted of about 70 publications that consist of empirical studies, systematic reviews, pilot projects reports, and international policy documents. Out of it, five to seven illustrative cases have been chosen in order to gain contextual information about the real-life implementation in various regions (e.g., Finland, Canada, India, South Africa, and the United States).

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

A data extraction template was used to summarize each included study/report:

Author(s), Year, Country

AI Tool/Technology Used

Health Topic Focus (e.g., nutrition, mental health, substance prevention)

Target Population (age, grade, demographics)

Outcomes (knowledge, skills, behaviour, engagement)

Challenges/Limitations

The extracted studies (summarized in

Table 2) revealed five dominant modalities of AI integration in school-based health literacy: chatbots, adaptive learning systems, immersive VR, learning analytics, and equity-oriented AI innovations.

To further compare regional applications and relative strength of evidence, a cross-comparison matrix was developed (

Table 3).

As shown in

Table 3, evidence for conversational AI tools such as chatbots is comparatively strong across Asia and high-income settings, while evidence for equity-oriented AI solutions in low-resource contexts remains limited but emerging. These patterns provide a foundation for the subsequent discussion of implications for educators, policymakers, and researchers.

2.5. Narrative Thematic Analysis

Instead of meta-analysis, narrative synthesis was used (Popay et al., 2006). The extracted data were coded in thematic categories:

Adaptive Learning Systems

Virtual Reality/ Simulation Tools.

Chatbots and Conversational Agents.

Early Intervention Learning Analytics.

Equities and Accessibility

These themes were later mapped onto cases, thus pointing out similarities, differences in contexts and lessons learned.

2.6. Case Illustration Approach

Purposeful sampling (Patton, 2015) was used to select case illustrations, making sure that they were varied in:

Geographic territories (Global North and South).

AI application type (chatbots, VR, adaptive systems).

Health (focus) (nutrition, mental health, substance prevention, hygiene).

The cases are presented narratively each one of which is accompanied by figures/diagrams that demonstrate:

2.7. Best Quality and Reliability

Even though narrative reviews are not as strict as systematic reviews, quality and transparency was ensured by:

A well-documented search and selection process.

Triangulation (academic + policy).

Reflexivity on limitations (e.g., publication bias, language restriction).

2.8. Ethical Considerations

Since this study entailed a secondary analysis of published material, there was no ethical clearance that was necessary. Nevertheless, the review also critically addressed certain ethical aspects of AI applications in schools data privacy, algorithmic bias, informed consent, equitable access, which is in line with recent literature (Madsen et al., 2025; Deckker, & Sumanasekara, 2025).

3. Narrative Themes and Case Examples

The review has found five major themes of AI applications in promoting health literacy in schools, namely (1) Adaptive Learning Systems, (2) Simulation Tools and Virtual Reality, (3) Chatbots and Conversational Agents, (4) Learning Analytics to Early Intervention, and (5) Consideration of Equity/Accessibility. When combined, these themes reveal the way AI technologies are being integrated into use across various aspects of functional, interactive, and critical health literacy in the world.

3.1. Adaptive Learning Systems

Adaptive learning systems driven by AI are personalized instruction depending on the learning pace, previous knowledge, and student interactions. They are also used in school health education applied to nutrition education and hygiene.

Case (Finland): A pilot study employed a customizable learning platform to deliver nutrition literacy to young people. The system altered the level of difficulty and feedback according to the reactions of learners, with the knowledge retention being much better than in the case of the traditional classroom lectures (Selanne et al., 2024).

Case Study (United States): Hygiene practices adaptive tool gave personal notifications and quizzes in the form of a gamification. The teachers noted that the level of participation among students and absenteeism decreased because of illness (Antoninis et al., 2023).

Such systems are in line with the functional aspect of health literacy as learners are able to learn key information based on their learning requirements.

3.2. Virtual Reality and Simulation Tools

Immersive technologies like VR and AR build experiential learning spaces in which the students can practice in a safe and non-hazardous environment making health-related decisions.

Case Study (Canada): A VR simulation also gave secondary school students a chance to practice situations of resisting peer pressure in relation to substance use. It was evaluated that there were better refusal skills and higher levels of self-efficacy when dealing with risky situations (Elendu et al., 2024).

Case Study (South Korea): VR-related exercise modules installed interactive exercise programs at schools. The frequency of motivation to engage in physical activity was higher among students as compared to regular physical education classes (Jiwon et al., 2025).

Interactive health literacy is greatly supported by simulation tools where learners get the chance to negotiate, communicate and act in realistic yet controlled setting.

3.3. Chatbots and Conversational Agents

Chatbots and other conversational AI tools provide a scalable platform of dissemination of health information that is both accessible and private.

Case Study (India): A chatbot was implemented in schools where girls would get sufficient information on menstrual health. Students said that they were more confident to cope with menstruation and less depended on peer-to-peer misinformation (Kaur and Singh, 2025).

Case Study (China): Chatbots with sexual health education enhanced knowledge retention and gave teenagers discrete entry to data (Zhou et al., 2020).

The instruments mainly enhance functional and critical health literacy that enables young learners to assess and consume health information in sensitive areas.

3.4. Learning Analytics to Early Intervention

Intelligent learning analytics give educators and administrators the ability to monitor the progress and to determine the students who may be becoming disengaged, or may have some unhealthy behaviour.

Case Study (United States): A school district implemented predictive learning analytics to track enrollment into a physical activity program in digital format. Students who were classified as at-risk due to low engagement were provided with special interventions, and the level of activity improved (Hung et al., 2020).

Case Study (Australia): Analytics dashboards were introduced into a health course to visualize student engagement of mental health modules. These insights were used by teachers to make timely guidance and referrals (Wong et al., 2022).

Analytics has a direct impact on essential health literacy because it provides educators and learners with actionable insights based on the data trends.

3.5. Consideration of Equity/Accessibility

An equity issue became a cut across. Although AI brings the chance of personalization and optimization of health education, disparities in the numbers of people having access to devices, internet, and training of teachers are a major concern.

Case Study (South Africa): An AI-based digital health literacy project implemented a community-based application to support schools in low-resource communities, but offline. Although the involvement went up, there were still issues regarding teacher capacity and infrastructure (Flatela & Funda, 2024).

Case Study (Brazil): A nutrition education mobile application based on AI increased the learning rates in urban schools but was not able to reach the rural population with low connectivity (Pritchard et al., 2016).

This theme highlights the moral necessity to create solutions that are inclusive in AI, in line with Universal Design to Learning (Rose et al., 2021).

Table 4.

Cases of AI in School-Based Health Literacy.

Table 4.

Cases of AI in School-Based Health Literacy.

| Theme |

Country |

AI Tool |

Health Focus |

Outcomes |

Challenges |

| Adaptive Learning |

Finland |

Adaptive platform |

Nutrition |

Improved retention |

Requires infrastructure |

| Adaptive Learning |

USA |

Gamified adaptive tool |

Hygiene |

Better participation, less absenteeism |

Teacher training |

| VR/Simulation |

Canada |

VR simulation |

Substance refusal |

Improved refusal skills, self-efficacy |

Cost, scalability |

| VR/Simulation |

South Korea |

VR exercise modules |

Physical activity |

Higher motivation |

Equipment access |

| Chatbots |

India |

Chatbot |

Menstrual health |

Greater confidence, reduced stigma |

Cultural barriers |

| Chatbots |

China |

Chatbot |

Sexual health |

Improved knowledge |

Privacy concerns |

| Analytics |

USA |

Predictive analytics |

Physical activity |

Higher engagement |

Data governance |

| Analytics |

Australia |

Dashboard |

Mental health |

Timely guidance/referrals |

Teacher data literacy |

| Equity |

South Africa |

Offline AI platform |

General health |

Higher engagement |

Resource limitations |

| Equity |

Brazil |

Mobile app |

Nutrition |

Improved urban outcomes |

Rural exclusion |

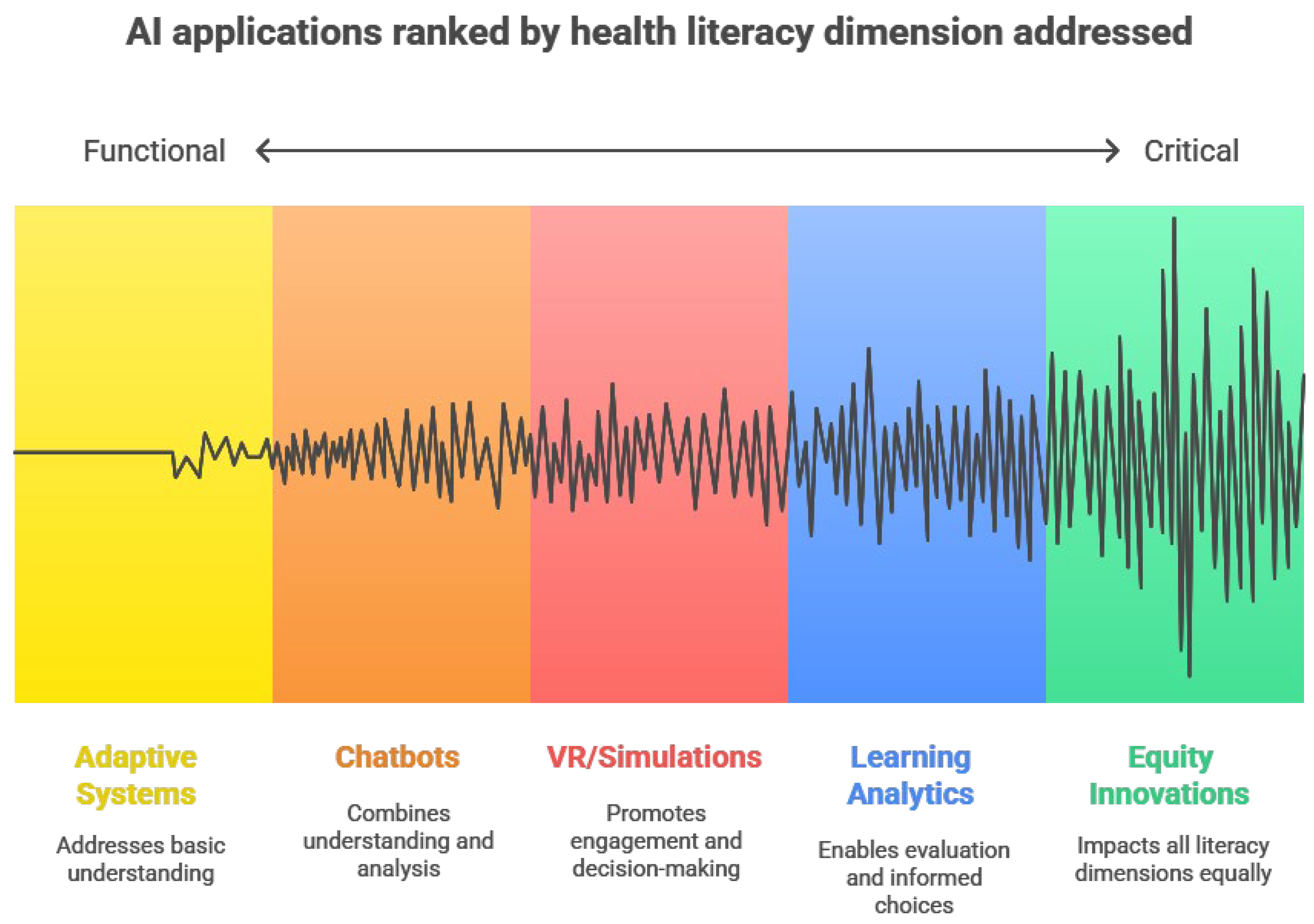

Figure 1.

Mapping AI Applications to Health Literacy Dimensions. Note: This conceptual mapping demonstrates how different AI modalities address distinct aspects of health literacy as outlined by Nutbeam (2000).

Figure 1.

Mapping AI Applications to Health Literacy Dimensions. Note: This conceptual mapping demonstrates how different AI modalities address distinct aspects of health literacy as outlined by Nutbeam (2000).

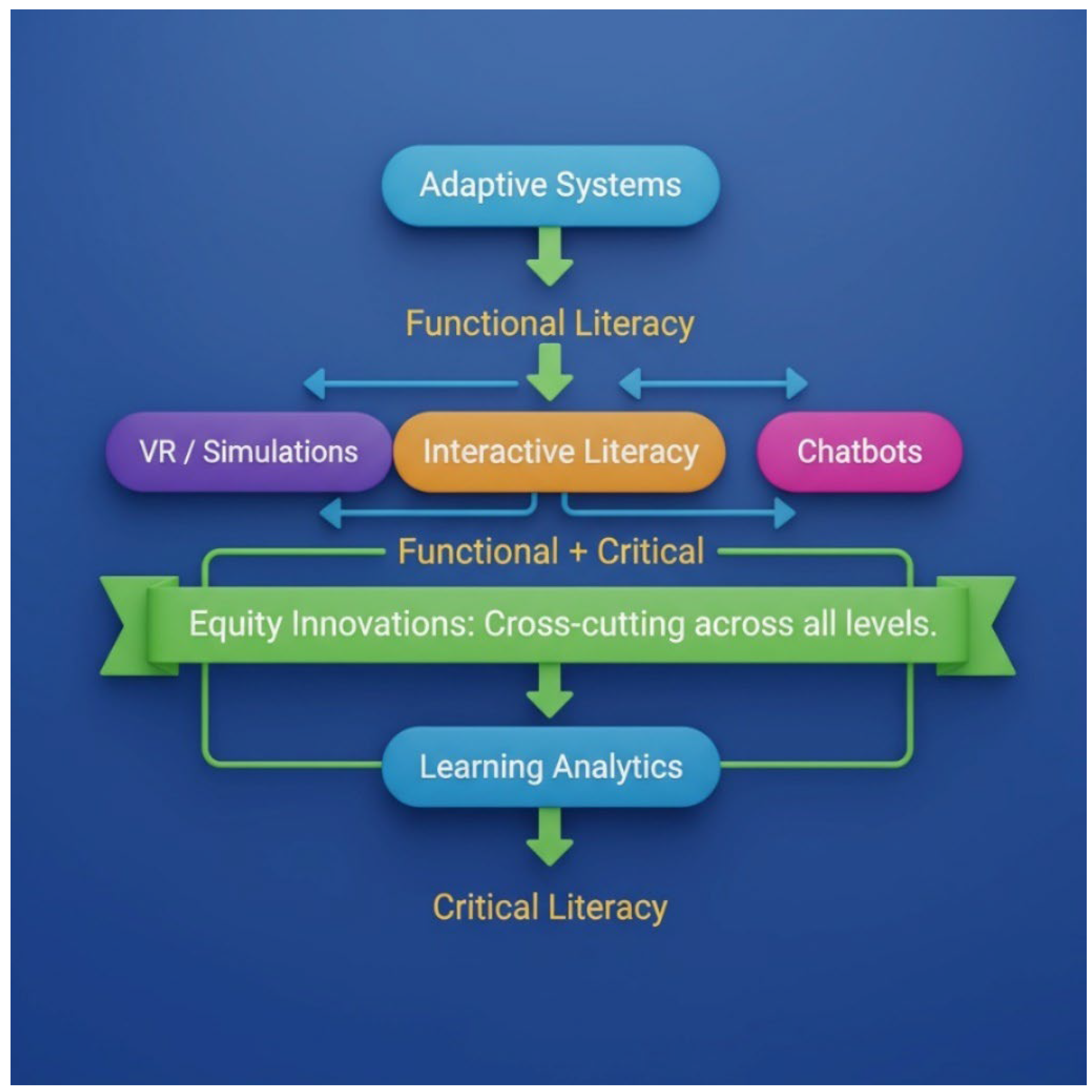

Figure 2.

Conceptual Diagram: AI Modalities and Health Literacy Dimensions.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Diagram: AI Modalities and Health Literacy Dimensions.

This diagram illustrates the relationships between AI applications and the three dimensions of health literacy (functional, interactive, critical), highlighting equity innovations as cross-cutting enablers.

4. Discussion

The findings of this narrative review highlight how Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies are redefining pedagogical possibilities for promoting health literacy in school settings. Across adaptive learning systems, immersive simulations, conversational agents, and learning analytics, AI tools demonstrate significant potential to strengthen functional, interactive, and critical health literacy among young learners. However, realizing this potential requires alignment with sound theoretical models, inclusive design principles, and robust policy frameworks to ensure ethical and equitable outcomes.

4.1. Linking Findings to Nutbeam’s Health Literacy Model

Nutbeam’s (2000) tripartite model--functional, interactive, and critical health literacy--provides a valuable lens for interpreting the ways AI technologies influence learning processes.

Functional Health Literacy, which focuses on the acquisition of factual knowledge and comprehension, is most directly supported by adaptive learning systems and chatbots. Adaptive AI modules allow personalized instruction, while chatbots provide on-demand clarification and reinforcement of basic health knowledge (Zhang et al., 2021).

Interactive Health Literacy, emphasizing social and communicative skills, is advanced through virtual reality simulations that create participatory learning environments. For example, the Canadian VR case (Lie et al., 2023) allowed learners to practice decision-making about substance use in a realistic, safe context. Such immersive, experiential learning transforms abstract health concepts into lived practice (Park & Kim, 2022).

Critical Health Literacy, involving critical appraisal and informed action on health information, is most closely linked to learning analytics and data-driven reflection. Predictive analytics systems, as seen in the U.S. and Australian cases (Hung et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2022), enable both teachers and students to engage with evidence-based insights, fostering reflection on personal and collective health behaviours.

This mapping illustrates that AI modalities collectively contribute to different--but complementary--dimensions of health literacy. Yet, the greatest impact occurs when these modalities are integrated, rather than deployed in isolation, creating a holistic ecosystem for lifelong health learning.

4.2. Incorporation of the Principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design of Learning (UDL) model focuses on offering various ways of engagement, representation, and action /expression to support diverse learners (Rose et al., 2005). Artificially intelligent applications are inherently in line with the UDL principles of personalization and flexibility.

Several Means of Engagement: Adaptive systems and gamified modules enhance motivation through varying the level of challenge to the needs of the learner.

Several Means of Representation: Chatbots and VR spaces provide information as a text, audio, and image and contribute to better understanding.

Learners are enabled to show learning by means of interactive simulations instead of written tests, which is a multiple Means of Action and Expression.

Nevertheless, the results also indicate that the introduction of UDL based on AI should not be unintentional. The issue of equity, especially in low-resource backgrounds (Adigun & Ogunsola, 2025), indicates that although AI can contribute to closing the learning gap, it can also increase it at the same time provided that access to technology and teacher training is uneven. This is in line with the premise of Eden et al. (2024) that ethical integration of AI in education has to focus on ensuring fairness, access, and inclusion.

4.3. Ethical Frameworks and responsible AI in School Health Education.

The responsible AI models emphasize transparency, accountability, data privacy, and fairness of the algorithm (UNESCO, 2023; Meduri et al., 2025). It is important to apply these principles to health education, as the health data of students is sensitive.

The cases that were reviewed indicate increased ethical awareness but no uniformity of application. In the case of chatbots, select interventions, such as those on sexual and reproductive health, pose a problem of privacy (Nadarzynski et al., 2024). Although learning analytics are useful in the early intervention of students, predictive models may create the risk of stigmatizing students when they are not transparent and lack contextual sensitivities (Stil et al., 2025).

Therefore, the introduction of AI in school health education should be supported through ethically governed systems. The policies are supposed to define the ownership of data, consent policies, and culturally responsive algorithms. Both the UNESCO (2023) and WHO (2020) frameworks suggest the use of human-centred solutions, in which AI will be a pedagogical ally and not a substitute of human teachers.

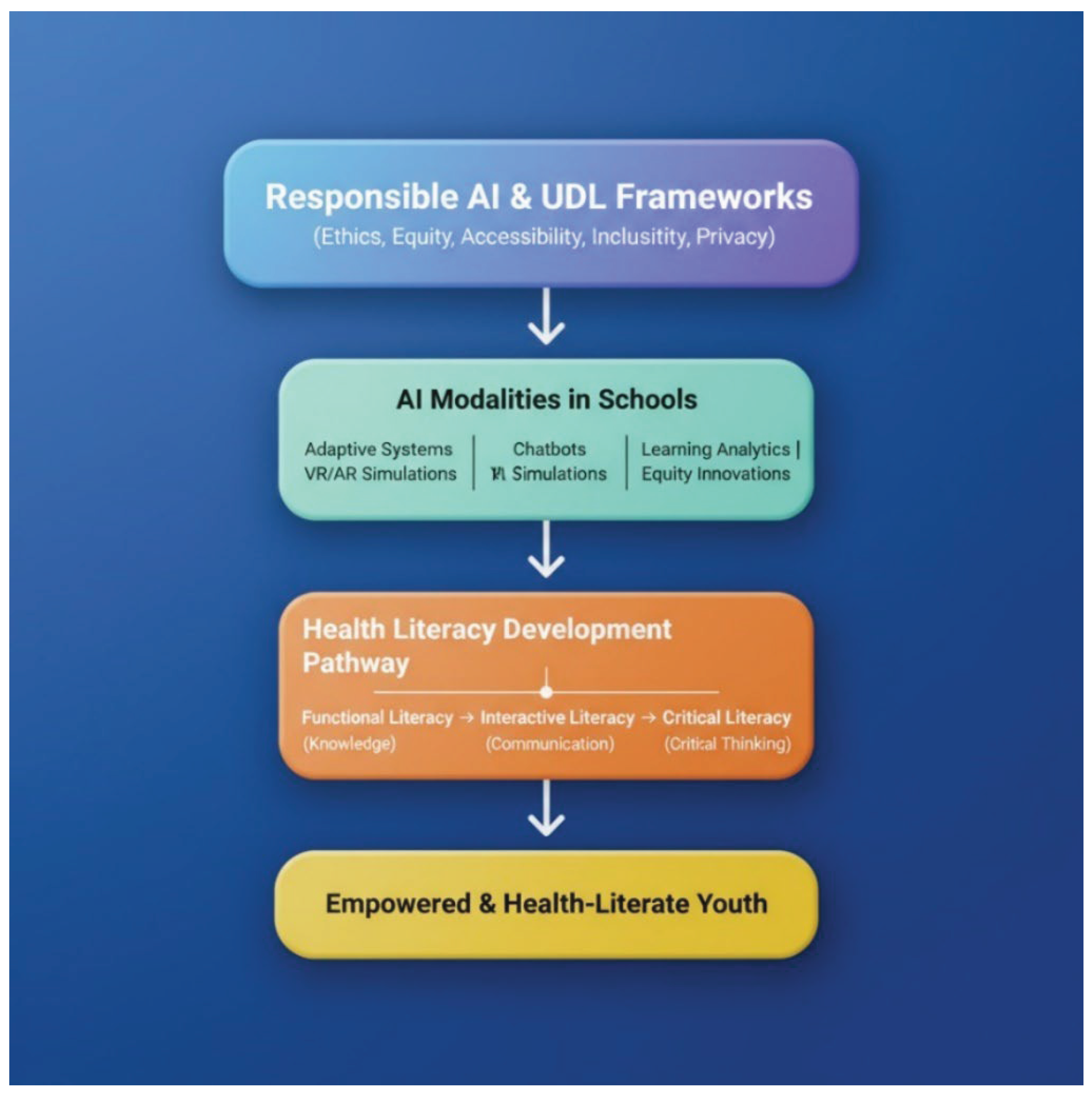

4.4. Implications (Theoretical and Practical)

4.4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The current review adds a synthesis informed by a theory by mapping the global applications of AI to the health literacy framework developed by Nutbeam. It reveals that:

AI modalities are synergistic toward the levels of literacy.

UDL integration is a guarantee to inclusivity.

Ethical involvement requires responsible AI concepts.

This multi-framework alignment presents a new conceptual framework the AI-Health Literacy Integration Model that describes how adaptive, immersive and analytic AI tools can interrelate to support health learning (see

Figure 3 below).

4.4.2. Practical Implications

For practitioners and policymakers:

The professional development provided to teachers should be at AI literacy and health education pedagogy.

Along with other health education standards, curriculum designers should not consider AI applications as a supplement.

The policymakers should invest in equal infrastructure such as low-bandwidth AI devices in the resource-strained schools.

To co-design tools, developers are recommended to collaborate with educators to develop culturally relevant pedagogically sound tools.

4.5. Addressing Gaps and Future Directions

Even though the results are promising, several gaps still remain:

Scanty longitudinal data: There is little research that evaluates long-term behavioural or cognitive improvements to short-term learning performance.

Geographical inequity: The vast majority of interventions would be conducted in wealthy countries; we need to have evidence on the part of African, Latin American, and South Asian schools.

Teacher preparedness and attitude: The human aspect of AI integration is not well studied, especially the mediation of teacher between AI outputs and pedagogic decision making.

Ethical literacy: Potential studies should test the comprehension of AI ethics, privacy, and data justice by teachers and students.

The future research must seek to adopt mixed-method and design-based studies to co-develop AI-based health education models alongside educators and communities, and assess both their effectiveness and ethical acceptability.

4.6. Synthesis and Conclusion

The AI-based pedagogies do not necessarily change anything, but when these are driven by theory, design inclusiveness, and responsible governance, their worth becomes apparent. A combination of a framework of health literacy per Nutbeam (2000), UDL principles (Rose et al., 2005), and responsible AI ethics (UNESCO, 2023) offers a logical line of innovation. Finally, to create health literacy using AI, it is necessary not only to be technologically sophisticated but also to provide human-oriented educational leadership that would incorporate equity, empathy, and empowerment at each design and implementation level.

This is the conceptual representation of how multiple AI modalities (adaptive learning, chatbots, VR simulation, and learning analytics) contribute to the gradual increase in the level of health literacy (functional, interactive, and critical) in the context of the Universal Design of Learning (UDL) and the principles of responsible AI.

Description:

The figure represents the intersection between three frameworks:

Health Literacy Dimensions (Functional, Interactive, Critical) demonstrated by Nutbeam as a result of the layers.

AI Modalities (Adaptive Systems, Chatbots, VR, Learning Analytics, Equity Tools) - presented as parallel technological enablers flowing into every literacy area.

Core Principles (UDL and Responsible AI) - represented as high level supports that bring in inclusivity and ethics.

The model depicts the way inclusive, ethically focused AI systems support the progressive development of simple functional knowledge to empowered and critical interactions with health information.

4.6.1. Implications for Educators

Educators and school health care professionals have a central role to play in defining the role of AI in the classroom. Pedagogically informed and ethically aware use of AI in health education requires educators to use it responsibly in order to take advantage of the opportunity.

The use of AI applications in school health curriculum, like adaptive learning platforms, chatbots, and virtual simulations, should be integrated into the current school curriculum instead of being viewed as an addition. An example of that is the ability of adaptive systems to customize lessons on nutrition or hygiene, or chatbots to have an uncensored conversation about a sensitive topic, like reproductive health or substance use (Ridgway et al., 2021). The incorporation of such tools into the formulated health modules creates pedagogical congruency and correlation to the learning outcomes.

- 2.

Creating AI Literacy in Teachers and Students

AI literacy, the knowledge of how AI works, its limitations, and its ethics, needs to be taught during teacher training. When teachers understand how adaptive algorithms operate, data privacy, and bias, they will be in a better position to make informed choices regarding the choice of tools and how they will be used in the classroom (Shah et al., 2023). In the same vein, students should be given a chance to appreciate AI as technology and ethical construct, so that they can become critical users and not passive consumers of technology.

- 3.

Practicing Human Mediation and Empathy

Although AI is capable of individualizing and scaling learning, it has no emotional intelligence, which is at the heart of teaching in humans. The human mediation should thus be preserved by the teachers so that AI-enhanced learning will be relational, empathetic, and context-driven (UNESCO, 2023). The interpretive and pastoral roles of the teacher cannot be substituted in health education when mental well-being or sexuality are the subject of discussion, and the teacher needs to be able to comprehend and show compassion.

- 4.

Culturally Responsive and Use of AI

Teachers need to judge AI technologies in terms of cultural and contextual relevance. The health beliefs, language diversity, and gender norms are diverse, and they will affect the way students perceive the AI-generated content (Adigun & Ogunsola, 2025). The digital health learning should be inclusive and respectful, which requires teachers to localize or adapt AI applications to the local values and student realities.

4.6.2. Implications for Policymakers

The preparation of AI into school health programs needs to be strategically planned, governed, and capacity-built on the policy level to provide equity and accountability.

The policymakers ought to come up with explicit ethical standards that govern data gathering, consent, transparency of the algorithms, and accountability. Given that school-going children are minors, the idea of privacy and protection has to be considered in particular (UNESCO, 2023). Education-related AIs must comply with the ethics of Responsible AI, which include transparency, fairness, explainability, and non-discrimination that must be enforced through legal means (Williamson & Piattoeva, 2023).

- 2.

Investing in Health Infrastructure and Digital

The fair distribution of AI-enhanced health education involves well-developed infrastructure, such as the internet, devices, and technical assistance, especially in low-resource areas. The policymakers need to invest resources in closing the digital divide that is disproportionately imposed on rural and marginalized communities (Pritchard et al., 2016). Focus on low-bandwidth and offline compatible solutions should be considered, but even in schools with limited infrastructure, only inclusiveness should be taken into account.

- 3.

Capacity- Building and Teacher Support

The teacher education systems should also have continuous professional development in AI pedagogy. The partnerships between governments and universities and EdTech companies can be used to create national strategies in AI-in-education that engage teachers for empowerment; aligns curriculum with AI needs; and provides ethical guidance (Sultana et al., 2025).

- 4.

Fostering Cross-Sectoral Cooperation

The ministry of health and education, technology providers, and community organizations should work together in the development and scalability of AI-based health education programs. The involvement of multi-stakeholders is a way of making sure that the technological solutions are responsive to the interests of the community and its health objectives regarding education. The cntralized approach would stop the dissemination of efforts and ensure the highest level of sustainability (UNESCO, 2023).

- 5.

Mechanisms of monitoring and evaluation

To determine the effect of AI interventions on health literacy outcomes, policy makers ought to develop evidence-based assessment systems. Ongoing surveillance will make sure that AI application is useful, inclusive and devoid of unintended damages. The criteria of evaluation need to be equity, learning outcomes, student well-being and teacher satisfaction.

4.6.3. Implications for Researchers

The new opportunities of interdisciplinary research the integration of AI and school health literacy poses to scholars include the opportunity to explore the relations among education, technology, and public health.

Majority of the available research is based on high-income nations that creates a knowledge gap geographically. To understand the role of contextual influences (including culture, infrastructure, and policy) in the success of AI in the school health program, researchers are advised to conduct comparative cross-country research (Hung et al., 2020).

- 2.

Integrating Hybrid Methodologies

Hybrid methods that would involve quantitative analytics (to gauge knowledge gain or engagement) in conjunction with qualitative methods (to investigate experiences, ethics, and socio-cultural dynamics) should be used in the future research. These mixed techniques will give a more in-depth idea of the effect of AI on the behaviour of students and the practice of teachers (Snyder, 2019).

- 3.

Assessment of Long-Term Existence

In the majority of AI health education research, the short-term learning measures are evaluated. Longitudinal studies that monitor behavioural change and persistent knowledge retention and transfer of health literacy skills into practice in real-life decision making are required (Wong et al., 2022).

- 4.

Research Design, Ethical and Participatory

The future research ought to embrace the methods of co-design and include teachers, students and communities in the creation of AI-oriented interventions. Participatory research can not only increase the level of relevance to context but also develop ethical ownership as a manifestation of responsible innovation (Abedini et al., 2021).

5. Conclusion

AI is changing the face of educational health in schools at a very high rate. The reviewed global experiences of this study show that AI may be effectively implemented to promote student engagement, individualization, and multidimensional health literacy building - functional, interactive, and critical abilities.

Nevertheless, this change should be situational, justifiable, and morally regulated. Technology, in itself, will not ensure health literacy increase; human tutors will always be required as they bring in sympathy, cultural knowledge, and ethical orientation. Therefore, the future of health education in schools is the synergy between AI innovation and human pedagogy.

The differences in context in terms of infrastructure, policy and preparedness of teachers imply that there is no universal model. Low-tech or hybrid AI systems, like an offline chatbot or an adaptive SMS-based learning, might produce the most significant effect in resource-limited environments. Immersive simulations and learning analytics can be applied in technologically advanced settings to expand on interactive and critical health literacy. Such situational plasticity is the feature of the sustainable integration of AI.

Policywise, ethics and data privacy regulations will have to change in order to protect learners, and AI-driven health education practices will be dictated by the success of investment in teacher education and the infrastructure. The Universal Design of Learning (UDL) principle is used as a guideline on how to make AI technologies suitable to accommodate all learners, irrespective of their abilities and backgrounds.

The next hurdle, to the research community, is to construct evidence-based, cross-cultural, and ethical models of health education through AI. The Global North-South collaborative networks between researchers can facilitate the scaling of innovations and at the same time be sensitive to local realities.

To sum up, AI can transform school health education but it requires human-centred implementation to be successful. To reach the future, an ecosystem has to be built in which educators, policymakers, and researchers combine their efforts to create AI tools that are pedagogically significant, ethically acceptable, and accessible to everyone. With the world collaborating and by sustaining innovation, AI can be a potent driver of creating a generation of health-savvy empowered youths who can make informed choices in their lifetime to stay healthy.

References

- Abedini, A.; Abedin, B.; Zowghi, D. Adult learning in online communities of practice: A systematic review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1663–1694. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, P.K.; Motiyani, I.; Oke, G.; Joshi, M.; Pathak, K.; Singh, S.M.; Chakraborty, T. Menstrual Health Education Using a Specialized Large Language Model in India: Development and Evaluation Study of MenstLLaMA. J. Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e71977–e71977. [CrossRef]

- Adigun, O.T.; Ogunsola, J.A. (2025). Inclusive Education Through the Lens of Open Distance Learning. In Improving Academic Performance and Achievement With Inclusive Learning Practices (pp. 175-210). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

- Antoninis, M., Alcott, B., Al Hadheri, S., April, D., Fouad Barakat, B., Barrios Rivera, M., ... & Weill, E. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms?.

- Borrelli, B.; Weinstein, D.; Endrighi, R.; Ling, N.; Koval, K.; Quintiliani, L.M.; Konieczny, K. Virtual Reality for the Prevention and Cessation of Nicotine Vaping in Youths: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2025, 14, e71961. [CrossRef]

- Chassignol, M.; Khoroshavin, A.; Klimova, A.; Bilyatdinova, A. Artificial Intelligence trends in education: a narrative overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 136, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-H.; Huang, C.-M.; Sheu, J.-J.; Liao, J.-Y.; Hsu, H.-P.; Wang, S.-W.; Guo, J.-L. Examining the Effectiveness of 3D Virtual Reality Training on Problem-solving, Self-efficacy, and Teamwork Among Inexperienced Volunteers Helping With Drug Use Prevention: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e29862. [CrossRef]

- Chipps, J.; Sibindi, T.; Cromhout, A.; Bagula, A. Use of artificial intelligence in healthcare in South Africa: A scoping review. Heal. SA Gesondheid 2025, 30, 10. [CrossRef]

- Deckker, D.; Sumanasekara, S. Student-centric ethical frameworks for AI-driven education: Participatory consent and data ownership in a global perspective. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 15, 1491–1503. [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, G.; Pelullo, C.P.; Volgare, A.S.; Napolitano, F.; Pavia, M. Parents’ Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children With COVID-19 Vaccine: Results of a Survey in Italy. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2022, 70, 550–558. [CrossRef]

- Eden, C.A.; Chisom, O.N.; Adeniyi, I.S. Integrating AI in education: Opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 10, 006–013. [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.B.; Amaechi, D.C.M.; Okatta, A.U.M.; Amaechi, E.C.M.; Elendu, T.C.B.; Ezeh, C.P.M.; Elendu, I.D.B. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [CrossRef]

- Flatela, A. B., & Funda, V. (2024). Enhancing AI digital literacy among South African youth: A model for inclusive participation. In International Conference on Emerging Technology and Interdisciplinary Sciences (pp. 54-60).

- Glavak et al. / C4TBH / Griffith (2018–2025). VR house-party simulation apps for alcohol & substance prevention in adolescents. [Pilot / demonstration reports].

- Glavak-Tkalić, R.; Šimunović, M.; Pavišić, K.P.; Razum, J.; Colombo, D. Virtual Reality in Prevention and Treatment of Substance-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70144. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews?. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. M., et al. (2025). VR prevention program feasibility pilot: Substance misuse & violence prevention [Pilot feasibility report].

- Griffin, K.W.; Botvin, G.J.; Williams, C.; Sousa, S.M. Using virtual reality technology to prevent substance misuse and violence among university students: A pilot and feasibility study. Heal. Informatics J. 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.-L.; Rice, K.; Kepka, J.; Yang, J. Improving predictive power through deep learning analysis of K-12 online student behaviors and discussion board content. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2020, 48, 199–212. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.L.; Sykes, S.; Wills, J. The conceptualization and development of critical health literacy in children: a scoping review. Heal. Promot. Int. 2023, 38. [CrossRef]

- Jiwon, H.; Jiwon, S.; Mai, N.T. Implementing Virtual Reality in Science Education at South Korean High Schools. J. Emerg. Technol. Educ. 2025, 3, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J., & Singh, P. (2025). Exploring the Potential of Peer Support Group for Family Planning Needs of Women in Resource-constrained Settings in India. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 9(2), 1-25.

- Liang, Y. T., Wang, C., & Hsiao, C. K. (2024). Data analytics in physical activity studies with accelerometers: scoping review. Journal of medical Internet research, 26, e59497.

- Lie, S. S., Helle, N., Sletteland, N. V., Vikman, M. D., & Bonsaksen, T. (2023). Implementation of virtual reality in health professions education: scoping review. JMIR medical education, 9, e41589.

- Luckin, R., Holmes, W., Griffiths, M., & Forcier, L. B. (2022). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. This book discusses various aspects of AI in education, including its role in assessment and exam proctoring.

- Madsen, M., Lunde, I. M., Piattoeva, N., & Karseth, B. (2025). Introduction: Time and temporality in the datafied governance of education. Critical Studies in Education, 66(2), 109-125.

- Meduri, K., Podicheti, S., Satish, S., & Whig, P. (2025). Accountability and transparency ensuring responsible AI development. In Ethical Dimensions of AI Development (pp. 83-102). IGI Global.

- Molina-Carmona, R., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2024). Safeguarding knowledge: ethical artificial intelligence governance in the university digital transformation. In Advanced Technologies and the University of the Future (pp. 201-220). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Nadarzynski, T., Knights, N., Husbands, D., Graham, C. A., Llewellyn, C. D., Buchanan, T., ... & Ridge, D. (2024). The impact of Chatbot-Assisted Self Assessment (CASA) on intentions for sexual health screening in people from minoritised ethnic groups at risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sexual Health, 21(4).

- Nguyen, T., Tran, K. D., Raza, A., Nguyen, Q. T., Bui, H. M., & Tran, K. P. (2023). Wearable technology for smart manufacturing in industry 5.0. In Artificial Intelligence for Smart Manufacturing: Methods, Applications, and Challenges (pp. 225-254). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–267.

- Paakkari, L., & Okan, O. (2020). COVID-19: health literacy is an underestimated problem. The lancet public health, 5(5), e249-e250.

- Park, S. M., & Kim, Y. G. (2022). A metaverse: Taxonomy, components, applications, and open challenges. IEEE access, 10, 4209-4251.

- Pritchard, B., Ortiz, R., & Shekar, M. (Eds.). (2016). Routledge handbook of food and nutrition security. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ridgway, J.P.; Uvin, A.; Schmitt, J.; Oliwa, T.; Almirol, E.; Devlin, S.; Schneider, J. Natural Language Processing of Clinical Notes to Identify Mental Illness and Substance Use Among People Living with HIV: Retrospective Cohort Study. JMIR Public Heal. Surveill. 2021, 9, e23456. [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, J. P., Uvin, A., Schmitt, J., Oliwa, T., Almirol, E., Devlin, S., & Schneider, J. (2021). Natural language processing of clinical notes to identify mental illness and substance use among people living with HIV: retrospective cohort study. JMIR Medical Informatics, 9(3), e23456.

- Rose, D. H., Meyer, A., & Hitchcock, C. (2005). The universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies. Harvard Education Press. 8 Story Street First Floor, Cambridge, MA 02138.

- Sakhi Chatbot” (MIT Solve). (2024). WhatsApp AI-enabled chatbot for menstrual hygiene and digital literacy. MIT Solve case report.

- Selänne, L., Pasanen, M., Aslan, F., & Pakarinen, A. (2024). Gamified Intervention for Health Promotion of Families in Child Health Clinics—A Cluster Randomised Trial. Simulation & Gaming, 55(3), 552-569.

- Shah, P. (2023). AI and the Future of Education: Teaching in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shankar, P. R. (2022). Artificial intelligence in health professions education. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 10(2), 256-261.

- Simonsen, N., Wackström, N., Roos, E., Suominen, S., Välimaa, R., Tynjälä, J., & Paakkari, L. (2021). Does health literacy explain regional health disparities among adolescents in Finland?. Health Promotion International, 36(6), 1727-1738.

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research, 104, 333-339.

- Stil, S. (2025). Understanding the Applications of AI for Autistic STEM Student Mentorship (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech).

- Sultana, N., ul Abidin, Z., Shifa, S., & Batool, I. (2025). Exploring How AI Can Support Ongoing Education and Professional Development, Helping Individuals Stay Current with Industry Trends. The Critical Review of Social Sciences Studies, 3(1), 3237-3251.

- UNESCO. (2023). AI and education: Guidance for policy-makers. UNESCO Publishing. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000376709.

- Wang, H., Gupta, S., Singhal, A., Muttreja, P., Singh, S., Sharma, P., & Piterova, A. (2022). An artificial intelligence chatbot for young people’s sexual and reproductive health in India (SnehAI): instrumental case study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e29969.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337895.

- Yu, P. K. (2020). The algorithmic divide and equality in the age of artificial intelligence. Fla. L. Rev., 72, 331.

- Zhou, L., Gao, J., Li, D., & Shum, H. Y. (2020). The design and implementation of xiaoice, an empathetic social chatbot. Computational Linguistics, 46(1), 53-93.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).