Abstract

This study introduces a novel mixed reality (MR) TMJ dislocation teaching program developed using HoloLens 2, through collaboration among interdisciplinary teams. The program offers an immersive learning experience, enabling learners to visualize and interact with detailed 3D temporomandibular joint (TMJ) models and practice different reduction techniques repeatedly. Real-time feedback of the virtual model enhances the learning process. The 3D printed skull model provided haptic feedback and further strengthened the positive feedback by MR model, reinforcing muscle memory. Despite some challenges related to the learning curve and cost, the program shows promise in medical education for complex clinical procedures. Future research directions include comparing traditional teaching methods, evaluating long-term skill retention, and exploring MR applications in other clinical procedures. Overall, this project demonstrates the potential of MR technology in advancing medical education and skill acquisition.

1. Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation is a relatively common condition, occurring worldwide, with reported incidence rates of 5.3 per 1,000,000 patients, and gender predilection varying across different populations [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This condition involves the displacement of the mandibular condyle from the articular fossa of the temporal bone, leading to considerable pain, functional impairment, and potential complications if not promptly addressed. The reduction technique is a crucial skill that healthcare professionals, particularly in the fields of emergency medicine, dentistry, and oral and maxillofacial surgery, must acquire to effectively manage TMJ dislocation cases. Traditionally, the teaching of TMJ dislocation reduction techniques has relied on conventional methods, including didactic lectures, anatomical models, and supervised hands-on practice. While these methods have served as the cornerstone of medical education, with their strength such as availability of expert guidance and tangible feedback, they possess certain limitations. The scarcity of patients presenting with TMJ dislocation, ethical considerations, time constraints, and limited opportunities for repeated practice often hinder the acquisition and refinement of necessary skills.

To bridge this gap and enhance the teaching of TMJ dislocation reduction technique, emerging technologies such as HoloLens 2 offer a novel and innovative approach. HoloLens 2, a mixed reality (MR) headset developed by Microsoft, is a type of three-dimensional (3D) visualization technologies that provides an immersive and interactive learning environment, merging virtual and real-world elements seamlessly. The use of mixed reality had been widely reported in literature of medical (particularly anatomy) teaching [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] and surgical procedures in operating rooms [

12,

13,

14]. Systematic review and meta-analysis of augmented reality/virtual reality technology or program in medical education and training had reaffirmed their positive improvement in users’ psychomotor performance, knowledge acquisition, and spatial ability, with larger effect observed in younger population and naturalistic studies [

15,

16,

17]. Furthermore, HoloLens 2, with six degrees of freedom, is shown to outperform devices with three degrees of freedom such as Google Cardboard [

18]. However, currently there is lack of literature regarding its use in uncommon but important clinical procedures, such as TMJ reduction technique.

By utilizing HoloLens 2 in teaching TMJ dislocation reduction, several benefits can be realized. Firstly, HoloLens 2 allows for the creation of highly detailed 3D holographic models of the temporomandibular joint, providing a comprehensive visualization of the anatomical structures involved. This immersive experience aids in understanding complex spatial relationships and assists in developing a more intuitive grasp of the reduction technique in a controlled setting.

Moreover, HoloLens 2 facilitates repeated practice of the TMJ reduction technique without relying on the availability of live patients. This feature overcomes the limitations imposed by the scarcity of suitable cases, ensuring that learners can gain proficiency through ample opportunities for simulated practice before real clinical use. Additionally, HoloLens 2 offers real-time feedback on the learner’s technique, enhancing the learning process by allowing immediate corrections and improvements. On the other hand, there are some limitations of using HoloLens 2 in procedural teaching such as TMJ dislocation. HoloLens 2 lacks the ability to provide tactile feedback or sensations, which are important in understanding the resistance and sensitivity of a patient’s jaw during the reduction procedure. The learning curve to master HoloLens 2, its cost and availability may also hinder widespread implementation in the short term.

In this paper, we describe the prototype development process of a novel teaching method for the TMJ dislocation reduction technique using HoloLens 2. We also attempt to overcome the limitation of tactile feedback by creating a customized 3D printed TMJ model to assist the learners in real world sensation, like those provided by the traditional teaching method. Through the amalgamation of virtual and real-world elements, HoloLens 2 holds promise in revolutionizing the way healthcare professionals are educated and trained in complex procedures. The following sections will dive into the methodology, results, and implications of incorporating the HoloLens 2 as a novel teaching modality for TMJ dislocation reduction, ultimately shedding light on its potential to improve medical education in this specific domain.

2. Materials and Methods

The development of the HoloLens TMJ teaching program involved a collaborative effort between emergency physicians, maxillofacial surgeons, computer scientists in the Samsung Medical Center (SMC) Smart Health Lab (SHL), and professional 3D modelling team. This multidisciplinary team brought together expertise in medical knowledge, surgical techniques, and cutting-edge technology to create an effective and immersive learning experience.

2.1. Design and Development

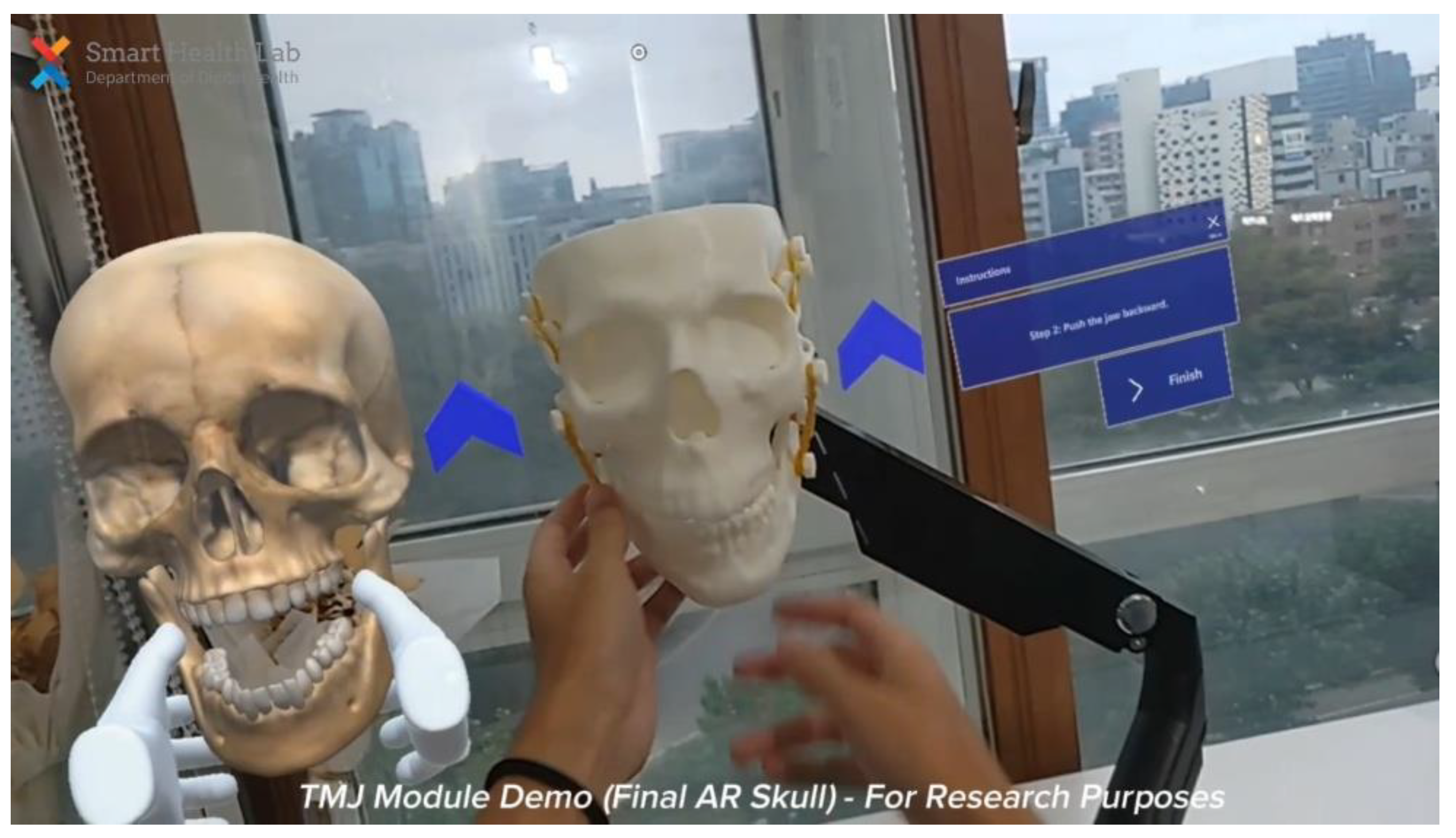

The team aims to create a learning experience, where users first have didactics about basic knowledge of TMJ dislocation. The user then observes the various reduction techniques in virtual skulls with practice. Lastly, users can practice the reduction technique repeatedly on the 3D printed TMJ model to enforce tactile feedback and muscle memory.

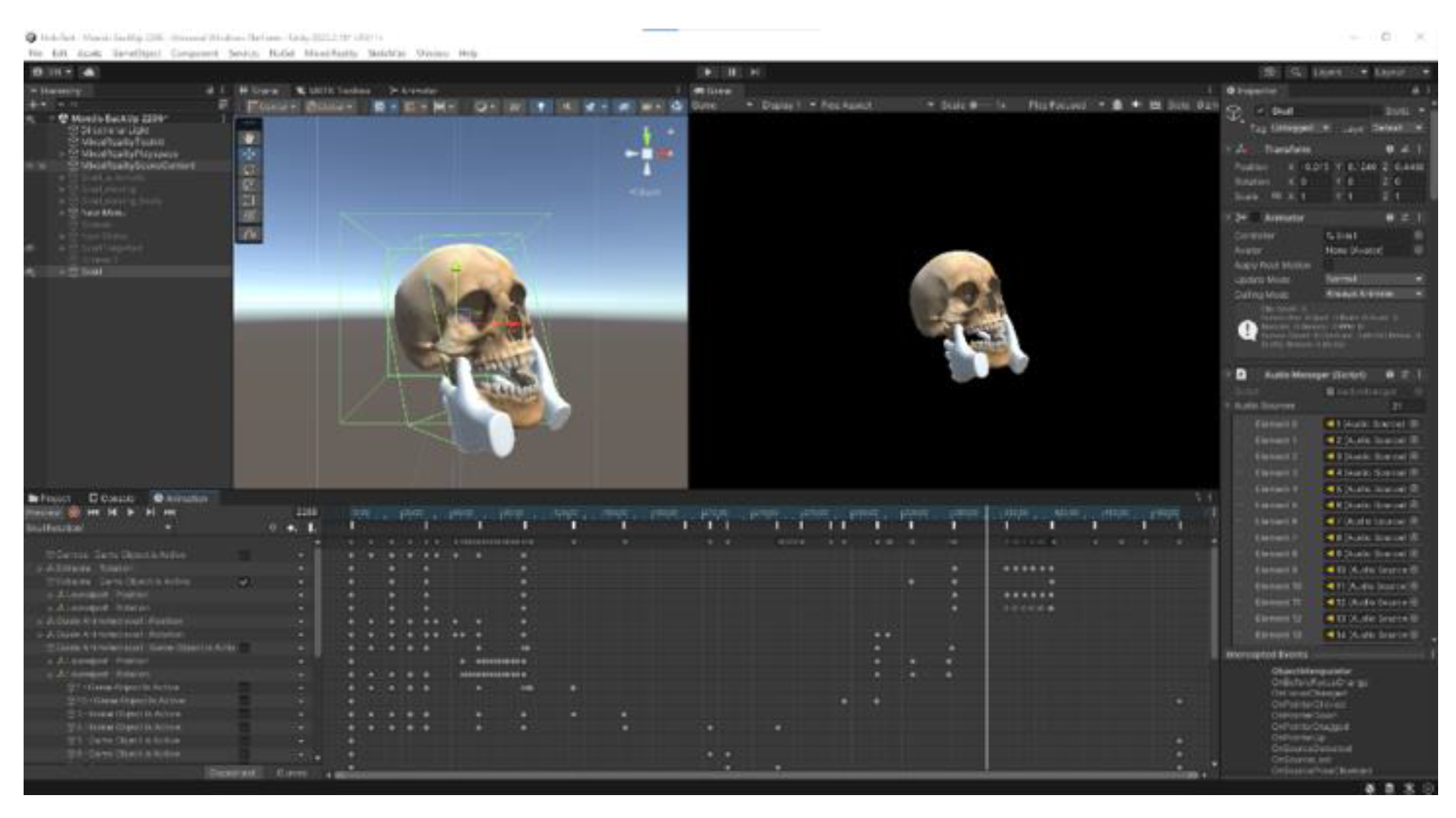

The team embarked on developing a virtual skull with detailed anatomy of the temporomandibular joint. The process involved acquisition of virtual skull model from an open source, with accurate anatomical features such as the mandibular condyle, condylar and coronoid process verified by emergency physicians and the maxillofacial surgeon. Unity (version 2022.2.19f1, Unity Technologies ApS., San Francisco, CA), MRTK (Mixed Reality Toolkit version 2.8.3.0), and Microsoft Visual Studio 2022, (version 2022, Microsoft Corp. Redmond, WA) were used to develop the entire Universal Windows Platform (UWP) application for HoloLens 2. Finally, for the AR part, we used Vuforia Engine 10.16’s model target.

We then separate the mandible from the rest of the skull, to al- low simulation of specific movement of the TMJ in normal position, anterior TMJ dislocation, as well as various reduction techniques. A pair of virtual hands holding to the mandible is added to illustrate the reduction techniques.

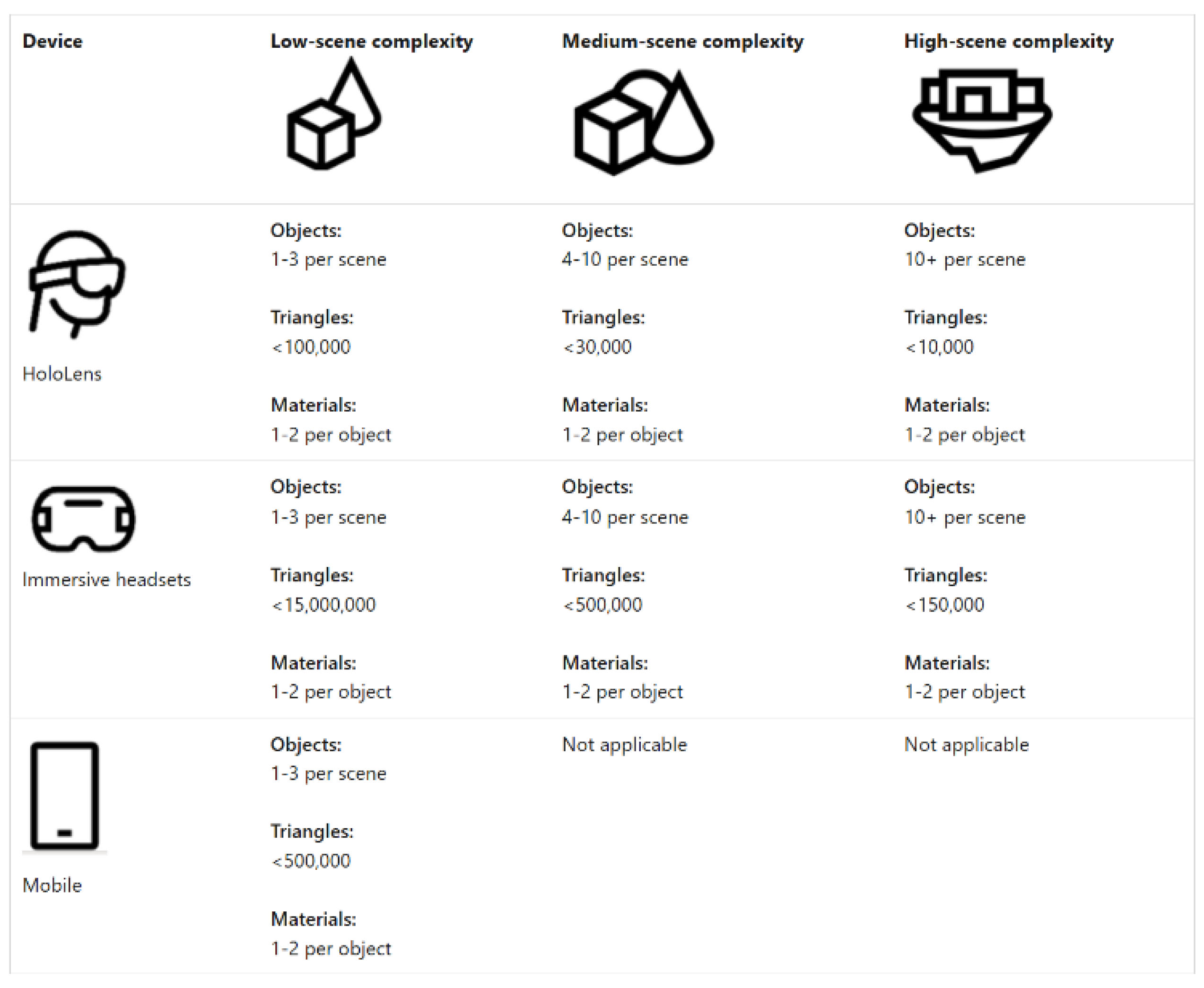

After noting the issue of dropping frame per second (fps) resulting in unsmooth animation, the team proceeded to reduce the triangles as solution with significant improvement.

Figure 1 lists some general conservative targets to aim for when acquiring or authoring 3D models for a range of hardware. When in doubt, target the midrange profile for a balance of fidelity and performance. For HoloLens 2, Microsoft advises to stay within the limit of maximum 100,000 polygons displayed on the screen, for a comfortable experience.

The team imported five virtual skulls in HoloLens 2 to facilitate user learning at different stages, namely Basic Skull, Jaw Locked, Intraoral, Extraoral and Syringe (

Figure 2).

The didactic materials were then added to the virtual environment, to provide the basic knowledge for users. Specifically, on the approaches of reduction techniques, the team described detailed steps and pearls of each procedure. Users can study the virtual skull at the same time during the didactics. The didactics provides two languages, namely Korean and English, to suit the need for local and international learners. The team also developed customized 3D printed TMJ model to help reinforce users’ understanding of the topic covered.

In addition to these practicable skulls, an AR part, namely Target Modeling, recognizes our real 3D printed skull to then display some live AR instruction to the user, following our real 3D skull.

2.2. 3D Printed TMJ Model: Printing Process, Challenges, and Modifications

A 3D skull in STL format was first obtained on an open-source website, thingiverse. It was then 3D printed to study the feasibility of simulating TMJ joint movement and adding simulated muscle. The first version of 3D skull used PLA and PVA filament, which took 96 hours to print. The mandible, on the other hand, used PLA filament that took 13 hours of printing time. After printing the original 3D skull and mandible model, the team found three main problems. First, the total 3D printing time was too long, which was about 100 hours. Second, considering the training environment in the real world, the printed skull should be fixed on a wall or desk, which needs modification of the original 3D model. Third, the zygomatic arch of the printed original 3D skull model was weak, so it needed a modification of the original 3D model.

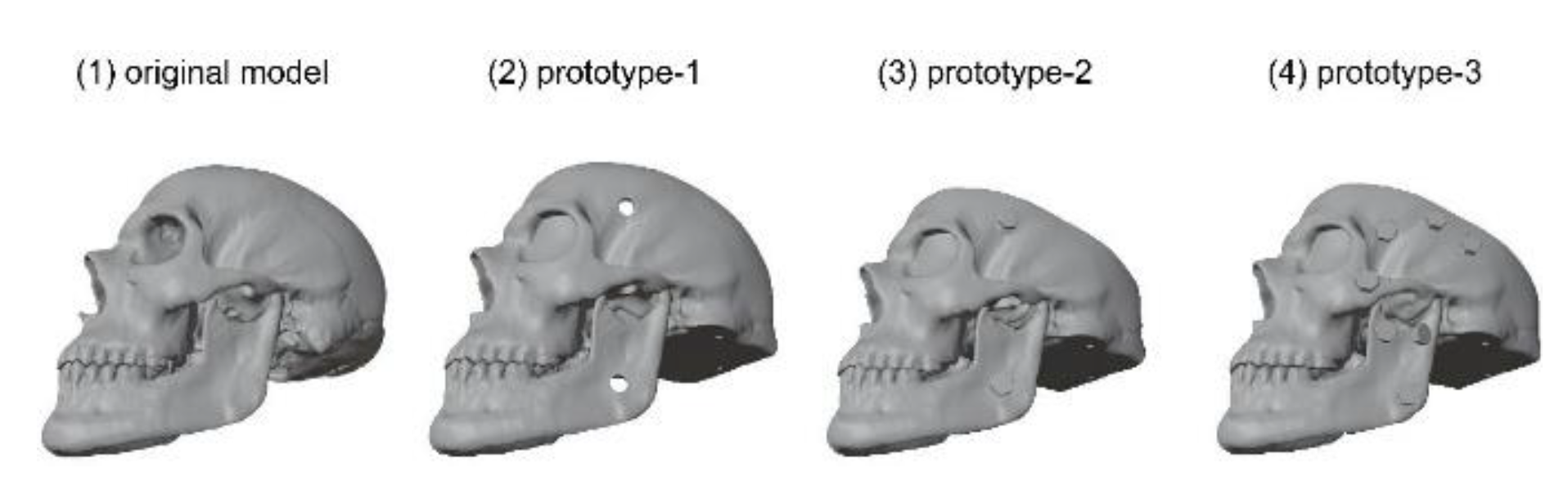

The 3D modeling team modified the original 3D skull model to prototype-1 with the open-source 3D graphics software Blender3D (vers.3.5, the Blender Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The team flattened the base of the skull and made 4 mm diameter 4 holes with 75 mm distance for fixing a 90 degree tiltable single mount monitor arm. In addition, a big hole was made on the backside of the skull for screwing the bolts and knots of the monitor arm. On each side of the skull, a 1 cm diameter hole was made on the side of the zygomatic arch for rubber bands, which represent the temporalis and masseter muscle.

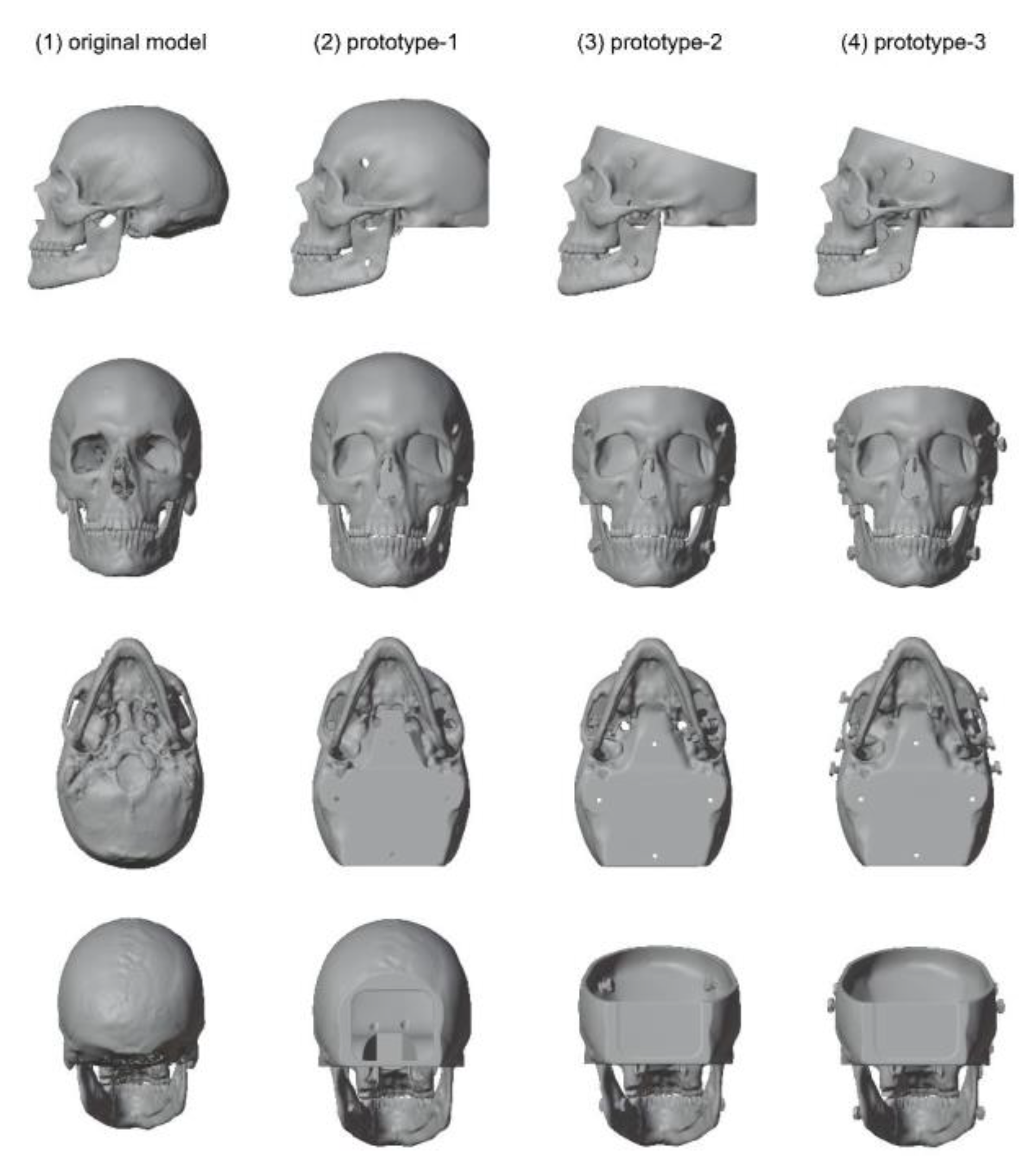

Prototype-1 was 3D printed with Cubicon Single Plus (3DP- 310F, Hyvision System, Sungnam, Korea). Cubicreator4 (v.4.3.0, Hyvision System, Sungnam, Korea) was used for slicing before 3D printing. 3D slicing is an essential process in 3D printing, and it converts a 3D model (.stl file) into a set of instructions called G-code (.hfb file) for the 3D printers. A set of instructions includes 3D printing options like the type of filament, layer height, density of supporter, density of infill, printing temperature, and printing speed. PLA filament was used for printing both the skull and mandible and layer height was 0.2 mm for the skull and 0.1mm for the mandible. Printing the skull took 61 hours and 59 minutes and the mandible took 14 hours and 30 min for the mandible minutes. Compared to the original model, prototype-1 saved about 30 hours of skull printing time. On the other hand, the printing time of the mandible increased by 1 hour 30 minutes. This is mainly because of the high-quality printing setting, and the 0.1 mm layer height. Thus, when printing prototype-2, the layer height of the mandible was changed. In the case of prototype-2, to shorten the printing time, unnecessary parts such as the upper and backside of the skull were removed from prototype-1. For better fixation of rubber bands, knobs were added instead of holes on the side of the skull and mandible. Moreover, to restrict the movement range of TMJ dislocation, an articular tubercle was added on each side of the skull.

Prototype-2 was also printed with PLA filament and for saving printing time, a 0.3 mm layer height setting was applied to both the skull and mandible. As a result, 29 hours and 47 minutes were needed for printing the skull and 5 hours 6 minutes for the mandible, which saved about 30 hours for the skull and 10 hours for the mandible. However, considering the origin and insertion of the temporalis and masseter muscle requires further modification for more realistic representation. Prototype-3 increased the number of knobs on each side of the skull and mandible. In addition, a knob was added on the anterior side of the zygomatic arch. The team also noted that the articular tubercle of the TMJ was not prominent enough, therefore both the articular tubercles were modified with increased prominence for better haptic feedback and stability during dislocation maneuver. The holes over the zygomatic arch were also moved anteriorly to facilitate the movement of simulated muscle. Below the skull, there was an articular tubercle of the TMJ but, it was not prominent enough so, we made it more prominent for a better feeling of the dislocation.

Compared to prototype-2, the 3D printing setting was the same in prototype-3 except for the density of the supporter. The density of the supporter changed from 1% to 5%, which saved 4 hours for skull printing and 5 minutes for mandible printing. In the case of the mandible, it requires only a small amount of supporters; therefore, changing the density of supporter made not that big difference.

In conclusion, the team developed a customized 3D printed TMJ model from a free-source 3D model. Considering the muscle attachment of the temporalis and masseter muscles, several knobs were added on each side of the skull and mandible. To restrict the movement range of TMJ dislocation, the prominent articular tubercle of the TMJ was increased under the skull. A flattened skull base and 4 holes were added for the fixation of the 3D-printed skull on a single monitor arm. Finally, optimizing the 3D printing setting made it possible to save total printing time on the skull and mandible from 110 hours to 30.25 hours, a 72% reduction. (

Figure 3 and 4). Moreover, we were able to cut the printing cost by as much as 43%. (

Table 1).

Figure 3.

3D model comparison according to the modeling modification.

Figure 3.

3D model comparison according to the modeling modification.

Figure 4.

Detailed 3D model comparison according to the modeling modification.

Figure 4.

Detailed 3D model comparison according to the modeling modification.

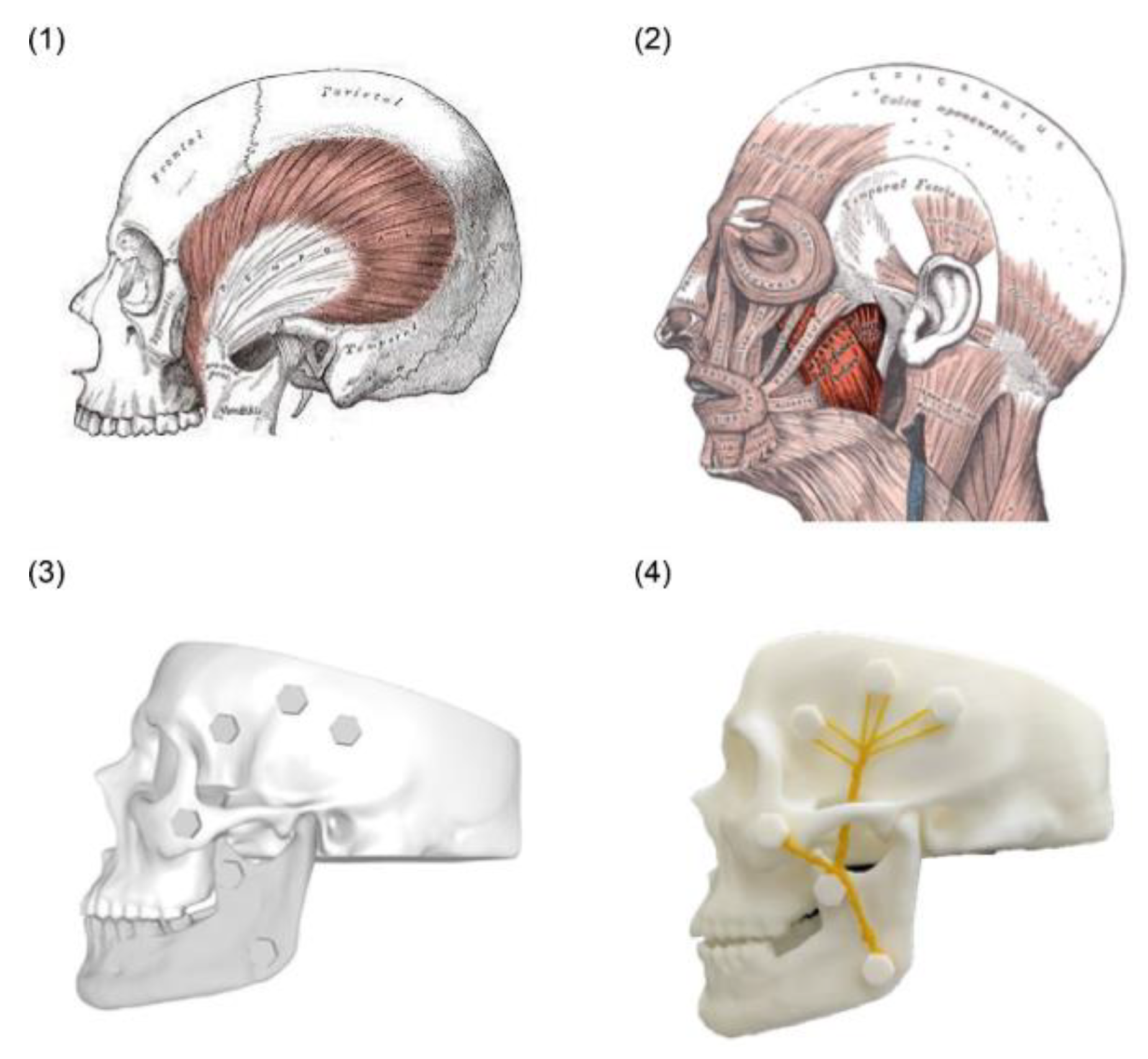

The team faced challenges with suitable material to simulate muscle movement. The temporalis muscle has a broad insertion that occupies most of the temporal fossa and inserts onto the tip and medial surface of coronoid process of mandible (

Figure 5, top left image). The masseter originates from the zygomatic arch and inserts along the angle and lateral surface of the mandible (

Figure 5, top right image). Facing issues with needs to customize the flexible muscle and possible stress onto the tip of coronoid process, the team eventually develop a system where rubbers bands with adjustable tightness are applied across 6 knobs on each side of the 3D printed skull (

Figure 5, bottom left image).The maxillofacial surgeon provided input on optimal location of knobs to simulate the temporalis and masseter muscle movement direction, and to enhance the prominence of the articular eminence for better simulation of TMJ dislocation. The 3D modeling team in SMC then proceeded to remove the details irrelevant to the TMJ reduction training, addition of knobs along both side of skull, removal of parietal and occipital part of skull, as well as placement of holes to allow fixation of base of skull onto a monitor holder readily available in market. Blender (version 3.5), a free 3D-image software, was used for the prototype design. The final product, at fifth revision, needs significantly less printing time at 25 hours for skull and 5 hours for mandible, and provided a much-improved degree of realism on TMJ for learning (

Figure 5, bottom right image).

3. Results

The program successfully developed:

Module 1: 3D interactive class of TMJ Dislocation, including slides, videos and 3D guides, to understand the science behind temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation, including anatomy, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management strategy;

Module 2: Anatomy models showing virtual skull with nor- mal TMJ movement, anterior TMJ dislocation, hands position in various reduction techniques, and movement of mandible in relation to skull in these techniques;

Module 3: 3D printed TMJ model for practical session including AR overlay.

In the module 1, users can learn in both English and Korean, in 3D interactive format, about the basic science of TMJ dislocation. This includes the definition, TMJ anatomy in depth in both normal and dislocation positions, clinical and imaging diagnosis of TMJ dislocation, as well as up-to-date information about three different reduction techniques reported in the medical literature (

Figure 6). The procedural steps and pearls of each technique are discussed in depth. This 3D interactive guide is approximately 8 minutes long.

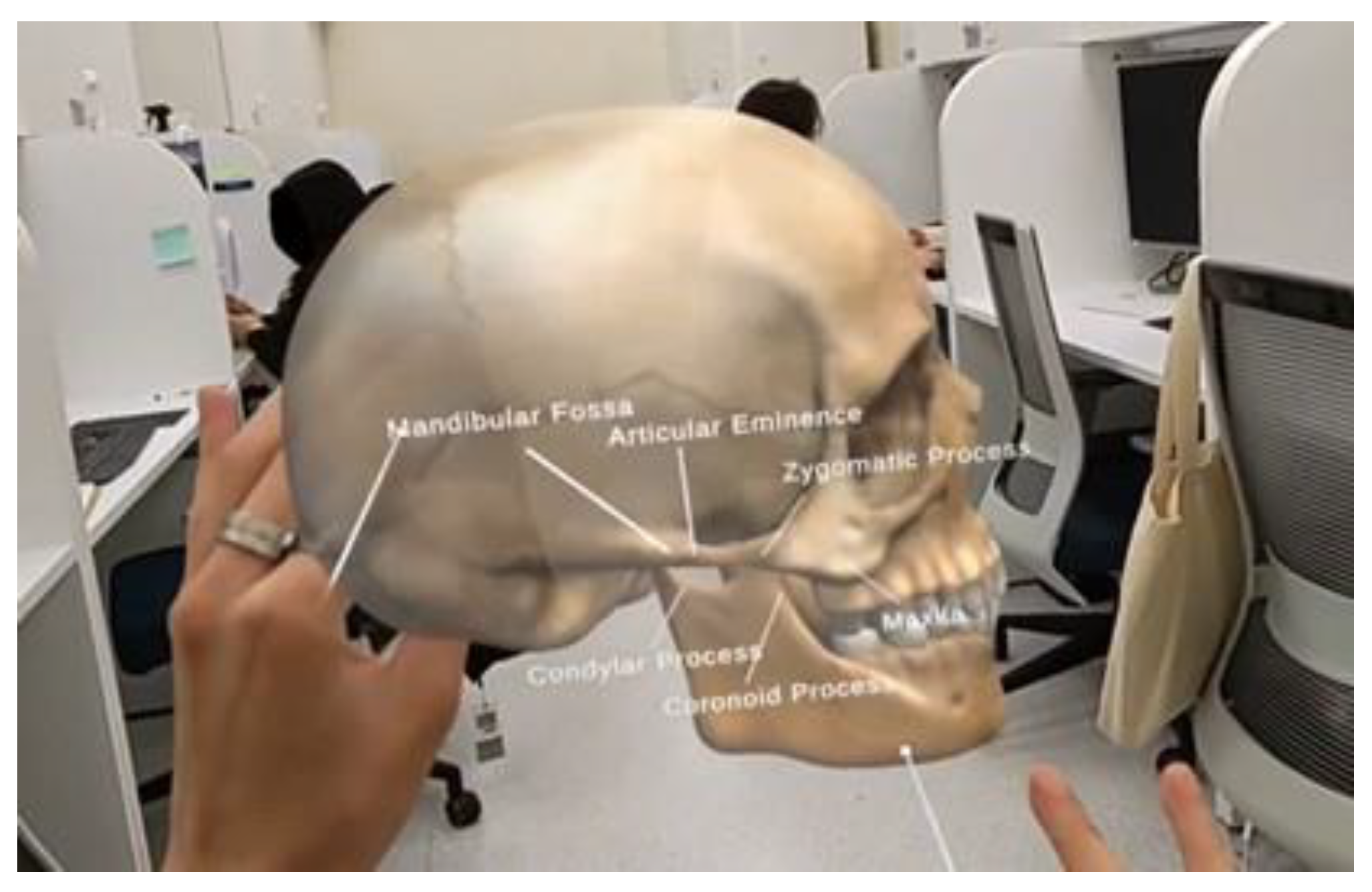

The second module allows users to observe closely the anatomy of TMJ on the virtual skull in a realistic 3D space. The users can manipulate the model’s size and viewing angles to orientate themselves on the spatial relationship of various anatomical structures in TMJ. For example, the users can observe that the TMJ movement in normal situations is comprised of 2 parts, where the initial 2 centimeters of mouth opening involving purely rotational movement of condylar process in the mandibular fossa; beyond 2 centimeters of mouth opening the condylar process will move along a sliding movement on the articular disc anteriorly. This complex action was difficult to understand and visualize with traditional teaching methods.

The next virtual skull will then show the process of TMJ dislocation. Users will appreciate the challenges of successful reduction due to the masseter muscle spasm that prevents the condylar process moving posteriorly. The subsequent virtual skull will show the reduction techniques, with virtual hands on the mandible, and illustrate the relative position of condylar process to the mandibular fossa. The three TMJ reduction techniques and mandible movement are described in

Table 2.

Lastly, users can “grasp” the mandible and simulate the movement in reduction techniques to place the mandible in correct position again (

Figure 7). The video demonstrating module 2 can be found in

Appendix A.1.

For Module 3, the 3D printed TMJ model supplements the HoloLens 2 limitation, to provide realistic tactile feedback to users. In addition to self-simulating the TMJ normal movement and dislocation, users can practice the three reduction techniques repeatedly and gain experience in the effective way to perform those techniques. The realism and ability to provide deliberate practice in controlled manner is extremely useful for uncommon but clinically important procedures such as TMJ dislocation. In this module, an AR Target Modelling feature was added to the 3D printed TMJ model. To achieve this feature, we used Vuforia’s model target generator to analyze the structure of our model, which took approximately 4 hours.

We then exported the model into unity. Thus, we could add our own educational overlays onto the 3D printed TMJ model (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated the development of a MR TMJ dislocation teaching program using HoloLens 2, with collaboration from several academic disciplines. This collective effort, where each interdisciplinary team shares knowledge and skills, leads to the development of a novel teaching approach to let users learn about TMJ dislocation and reduction techniques. We believe that we are the first team that reports MR assisted TMJ education in literature, and this serves as a steppingstone to more future use cases in education of uncommon but clinically important procedures, such as reduction of shoulder and elbow dislocation, reduction of wrist and ankle fracture, open thoracotomy, lateral canthectomy, and even perimortem cesarean section.

The project has few strengths compared to traditional teaching methods. First, the use of HoloLens 2 provides an immersive learning experience, allowing learners to visualize and interact with 3D holographic models of the TMJ. This enhanced engagement can facilitate better understanding and retention of complex anatomical structures and procedural techniques. Secondly, HoloLens 2 enables learners to repeatedly practice the TMJ reduction technique in a safe and controlled virtual environment. This repetitive practice can enhance skill acquisition and build confidence, especially considering the limited availability of patients with TMJ dislocation. Subsequent practice on 3D printed TMJ model then further reinforce the skills and muscle memory. Thirdly, the HoloLens 2 and 3D TMJ model can provide instantaneous feedback on the learner’s technique, allowing for immediate adjustments and improvements. This real-time feedback mechanism can accelerate the learning process and help learners refine their skills more effectively. Lastly, the user’s view in HoloLens 2 can be projected real-time onto a monitor. This makes tele-education possible, where group learning, distant learning, and interactive conference presentation are able to reach learners, which is not possible with traditional methods.

This paper described the development process in a pragmatic and detailed way, sharing challenges faces and our solution. The team explained approaches during development of the virtual skull (reduce numbers of triangles, animation of mandible, how to create engaging and seamless users experience), as well as 3D TMJ model such as approach to simplify the model to shorten printing time. The virtual model and 3D printed model can be readily available in open-source websites, with user friendly 3D modelling program to colleagues with computer science background. As a result, similar projects can be reproducible by other teams without need for cutting-edge technology or high-cost resource.

There are a few limitations observed in this project. First, the adoption of HoloLens 2 technology requires familiarity with the device and its software. There may be a learning curve involved in mastering the operation of the HoloLens 2, which could potentially divert the learners’ attention from the core technique itself. Secondly, the implementation of HoloLens 2 technology may be limited by cost and accessibility issues. The acquisition and maintenance costs of the hardware and software, as well as the availability of the HoloLens 2 in educational institutions, may pose challenges to widespread adoption.

This project provides possibilities of future research directions. Comparative studies comparing the HoloLens 2 teaching method with traditional teaching methods can provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and superiority of the novel approach. Assessing learning outcomes, skill acquisition, and learner satisfaction in controlled studies can contribute to evidence-based educational practices. In addition, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term skill retention of learners trained with the HoloLens 2 teaching method. Assessing their ability to apply the learned techniques in real-world clinical settings and evaluating their long-term performance can provide valuable insights into the durability and effectiveness of this novel teaching modality. Similar studies combining MR with task trainers to complement haptic feedback for other clinical procedures can be performed, such as reduction of joint dislocation or fracture, lateral canthectomy, open thoracotomy, and perimortem cesarean section. The integration with existing surgical simulators in some of these procedures could create a comprehensive training platform for medical trainees.

5. Conclusion

The novel teaching method utilizing the HoloLens 2 with 3D printed model for teaching TMJ dislocation reduction technique demonstrates significant strengths in terms of immersive and interactive learning, repeatable practice, and real-time haptic feedback. However, the limitations surrounding technical challenges and cost should be acknowledged. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations, conducting comparative studies, evaluating long-term skill retention, and exploring integration with surgical simulators. The ongoing development and refinement of this teaching method holds great potential to enhance the training of uncommon but clinically important procedures and contributes to the advancement of medical education

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

N.L.V. and W.M.N. conceptualized the research study. N.L.V., W.M.N., S.L., J.R., J.A., J.C.K., M.H.S., and W.C.C. developed the methodology. N.L.V. and W.M.N. prepared the original draft of the manuscript. N.L.V., W.M.N., S.L., J.R., J.A., J.C.K., M.H.S., W.C.C. contributed to review and editing of the manuscript. M.H.S. and W.C.C. acquired funding for the project. S.L., J.R., J.A., J.C.K., M.H.S. and W.C.C. provided resources for the study. M.H.S. and W.C.C. supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

HoloLens 2 (Microsoft) were provided by the Samsung Medical Center. This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant HI23C0460).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| FPS |

Frames Per Second |

| MR |

Mixed Reality |

| MRTK |

Mixed Reality Toolkit |

| PLA |

Polylactic Acid |

| PVA |

Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| SHL |

Smart health Lab |

| SMC |

Samsung Medical Center |

| STL |

Stereolithography |

| TMJ |

Temporomandibular Joint |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Video of Module 1,2 & 3

References

- Agbara, R.; Fomete, B.; Obiadazie, A.C.; Idehen, K.; Okeke, U. Temporomandibular joint dislocation: experiences from Zaria, Nigeria. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 40, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsis, G.; Papoutsi, S.; Klukowska-Rötzler, J.; Schaller, B.; Exadaktylos, A.K. Temporomandibular joint dislocation: a retrospective study from a Swiss urban emergency department. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2018, 10, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnakumar Raja, V.B. Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation. In Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for the Clinician; Bonanthaya, K., Panneerselvam, E., Manuel, S., Kumar, V.V., Rai, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1381–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Singh, A.K.; Pandey, A.; Verma, V.; Singh, S. Temporomandibular joint dislocation. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 6, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniam, P.; Schnell, P.; Dan, L.; Portelli, R.; Erolin, C.; Mountain, R.; Wilkinson, T. Exploration of temporal bone anatomy using mixed reality (HoloLens): development of a mixed reality anatomy teaching resource prototype. J. Vis. Commun. Med. 2020, 43, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. Development and feasibility evaluation of an AR-assisted radiotherapy positioning system. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 921607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McJunkin, J.L.; Jiramongkolchai, P.; Chung, W.; Southworth, M.; Durakovic, N.; Buchman, C.A.; Silva, J.R. Development of a mixed reality platform for lateral skull base anatomy. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, e1137–e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, A.; Lau, L.Y.; Awad, Z.; Darzi, A.; Singh, A.; Tolley, N. Virtual reality simulation training in otolaryngology. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, E. Virtual reality simulation—the future of orthopaedic training: a systematic review and narrative analysis. Adv. Simul. 2021, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, A.D.; Hierck, B.P.; de Jong, P.G.M.; et al. User experiences of medical students with 360-degree virtual reality applications to prepare them for the clerkships. Virtual Reality 2023, 27, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutitas, G.; Smith, S.; Lawrence, G. Performance evaluation of AR/VR training technologies for EMS first responders. Virtual Reality 2021, 25, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, O.M.; Rudy, H.L.; Lefkowitz, A.; Weimer, K.A.; Marks, S.M.; Stern, C.S.; Garfein, E.S. Mixed reality with HoloLens: where virtual reality meets augmented reality in the operating room. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubben, P.L.; Sinlae, R.S.N. Feasibility of using a low-cost head-mounted augmented reality device in the operating room. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2019, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Jiang, T.; Dou, J.; Yu, D.; Ndaro, Z.N.; Du, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, G. A novel evaluation model for a mixed-reality surgical navigation system: where Microsoft HoloLens meets the operating room. Surg. Innov. 2020, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, M.C.; Davis, M.M. A meta-analysis of augmented reality programs for education and training. Virtual Reality 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abich, J.; Parker, J.; Murphy, J.S.; et al. A review of the evidence for training effectiveness with virtual reality technology. Virtual Reality 2021, 25, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, S.; Kennedy, G.; Sanzone, S. Toward the validation of VR-HMDs for medical education: a systematic literature review. Virtual Reality 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsikpasi, P.; Fokides, E. A scoping review of the educational uses of 6DoF HMDs. Virtual Reality 2022, 26, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).