1. Introduction

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) is a distinct B-cell lymphoma that shares clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic features with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL). Since its classification as a separate entity, MGZL has been a significant diagnostic problem because of its rarity, subjective diagnostic criteria, non availability of treatment protocols, and aggressive course of the disease [

1,

2]. Gray zone lymphoma (GZL), also known as “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and CHL,” represents the biological overlap between DLBCL—specifically PMBL—and CHL, particularly the nodular sclerosis variant [

3]. Treatments for tumors in this spectrum have focused on resection with or without subsequent chemotherapy, and these tumors often display histologic and immunophenotypic overlap with both disorders, making accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions difficult [

4,

5,

6]. The lack of established diagnostic markers and consensus on therapeutic strategy, however, remains a great impediment in practice for the pathologist and the clinician [

4,

5,

6]. Here, we provide a focused review of the epidemiology, clinical presentation, pathology, and therapy of GZL, including current challenges, and the outlook for the future.

2. Historical Perspective and WHO Classification of MGZL

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma was first described as a separate clinicopathologic entity in 1998 at a workshop on HL and related diseases on the basis of 5 cases demonstrating characteristics between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) in the mediastinum [

7]. The importance of this immunohistochemical profile in suggesting the diagnosis of a clonal lymphoid proliferation of intermediate clinical spectrum was stressed in a larger series from the National Institutes of Health in 2005 including 21 cases that further validated the existence of such intermediate entity [

8].

Because of these early reports, the 2008 4

th Edition WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues included a provisional entity, designated as “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and CHL” (gray zone lymphoma (GZL)) [

2]. This definition included tumors with morphologic features reminiscent of CHL but maintaining a B-cell phenotype, as well as those with morphologic PMBL with a CHL-like immunophenotypic profile (CD30+, CD15+, no B-cell markers, no CD45) [

9].

The updated 4

th Edition (2017) maintained this provisional category. However, follow-up gene expression profiling and immunohistochemistry data indicated that mediastinal cases had a biology separate from that of their non-mediastinal counterparts. In fact, non-mediastinal GZL cases, characterized by an older age at diagnosis, displayed distinctive molecular profiles and are currently regarded as being biologically nearer to DLBCL, NOS [

10,

11].

The notion of GZL was thus refined in the WHO Classification, 5

th Edition (WHO-HEMA5, 2022). The definition was limited to mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL), a B-cell lymphoma with features intermediate between PMBL and nodular sclerosis CHL believed to begin in the thymic B cells [

9]. Despite the related biology, composite/sequential CHL/PMBL presentations are not recognized as MGZL. In the same vein, EBV-positive DLBCL with a component of introduced Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg-like cells should be in the EBV-positive DLBCL category, as molecular investigations have revealed different pathogenetic pathways [

1,

2].

With the definition of GZL restricted to a mediastinal presentation, the ICC (2022) and the WHOHEMA5 are now in agreement, emphasizing the critical role of both topography and biology in the identification of this rare entity [

1,

2].

3. Clinical Presentation

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) usually occurs in young adults, with a peak incidence of 33-35 years by the definition of MGZL in Kritharis et al. and Pilichowska et al., and presents with a striking male preponderance, affecting about two-thirds of all cases [

12,

13]. The most common clinical presentation is bulky mediastinal mass that can be seen in almost half of the patients. Such mass effect may cause symptoms of SVC syndrome, dyspnea, or respiratory symptoms. Supraclavicular lymph node recurrence is common, and extranodal sites are not seen frequently at the first presentation. Stage IV disease is developed in only approximately 13% of patients [

12].

The mediastinal disease can also spread at the locoregional level toward the lungs and has been reported to metastasize also to the liver, spleen, and bone marrow in relapsed or refractory disease. These findings underscore the aggressive clinical demeanor of MGZL relative to PMBL or CHL [

16]. Epidemiologic differences have been reported as well. Sarkozy et al. described a higher median age (46-48 years) and an equal male/female sex ratio (M/F = 1:1) in this series, although these differences probably reflect the inclusion of both mediastinal ("thymic") and extramediastinal ("non-thymic") cases [

14,

15]. Therefore, once mediastinal and non-mediastinal presentations are considered separately, differences become apparent. Pilichowska et al. showed that mediastinal cases have a lower median age at diagnosis (35 vs. 51 years), more frequently present disease at earlier stage (I/II, 89% vs. 46%) and more often bulky disease (44% vs. 0%) than non-mediastinal ones [

4].

In summary, MGZL shows a male predominance, bulky mediastinal disease, a high frequency of early-stage disease and an aggressive clinical course which sets it apart from both CHL and PMBL, highlighting the variability in clinical behavior between mediastinal versus non-mediastinal gray zone lymphomas [

16].

4. Pathology and Immunophenotype

The term GZL refers to a group of cases with more or less marked morphologic and phenotypic discordance, and ranging between CHL and PMBL [

17]. Tumor cells are generally more numerous and may resemble centroblastic or immunoblastic cells akin to PMBL, however they are typically larger, more pleomorphic, and frequently show mixed morphology. Reed-Sternberg (RS)-like or lacunar cells may accompany, but are usually of intermediate size with less prominent eosinophilic nucleoli compared to classical RS [

4,

8,

18]. Inflammatory backgrounds historically seen with CHL, including an eosinophil- or plasma cell-rich infiltrate, are usually not as conspicuous, and necrosis may be rare or only mild in its extent [

3,

8,

18]. Architectural patterns are often indistinct, although a nodular or coarsely fibrotic process may be present in some cases [

4,

18].

4.1. B-Cell Markers and Transcription Factors

B-cell markers (one or a combination of CD20, CD79a, and PAX5) are at least focally expressed in GZL. It also makes reporters for such transcription factors as BOB.1 and OCT-2 is variable [

8]. Some centroblastic-type cases are CD20 negative/weak, but CD30 and frequently CD15 positive [

8,

19]. Conversely, high B-cell transcription factors (PAX5, BOB.1/BCL6, OCT-2) expression was observed in an abundance of RS-like cells within the tumours and CD45 and were negative with CD15 [

8,

13,

18].

4.2. Activation and Additional Markers

CD30 is nearly always positive, often of only weak intensity [

8,

18]. Some are also CD15 negative and may vary from negative in some to moderate to strong by morphology. CD23 and MAL can also be observed in subsets of cases [

8,

18]. Overexpression of PD-L1/PD-L2 is common and the corresponding CIITA and CD274 genetic abnormalities were illustrated by FISH in both the studies [

20]. EBER positivity cases have been infrequently described and to this point of time under actual ICC/WHO criteria all cases of EBV positive are excluded from the MGZL [

21].

4.3. Proposed Subgroups (Sarkozy et al.)

Sarkozy and associates suggested four morphophenotypic subgroups of BLHL, bordering CHL-like (Group 0–1) to PMBL-like (Group 2–3) based on architecture, fibrosis, and immunophenotypic profile [

16,

18]. Although convenient conceptually, this subclassification suffers from subjectiveness and includes non-mediastinal and EBV-positive cases that are not part of the current WHO-HEMA5 MGZL definition anymore [

1,

2]. Immunophenotypically, MGZL exhibits variable features that overlap with both CHL and PMBL, as summarized in

Table 1.

In general, the immunophenotypic profile of MGZL lies intermediated between CHL and PMBL, with variable expression of B-cell markers, nearly universal expression of CD30, and variable CD15 expression. This immunophenotypic “gray zone” adds to the diagnostic challenge and supports MGZL as a distinct entity [

22].

5. Molecular and Genetic Features

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) shares several genetic and molecular features with both PMBL and CHL identifying it as a biological intermediate. However, recent research has shown that MGZL has specific changes that warrant its recognition as a distinct entity [

23].

5.1. Overlapping with CHL and PMBL

Both PMBL and CHL commonly demonstrate gains at the REL locus (2p16. 1) and the JAK2/CD274/PDCD1LG2 region (9p24. 1), which results in the overexpression of PD-L1 and PD-L2, as well as the activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway [

18,

23]. Changes in the CIITA locus (16p13.3) and MHC-I expression are insufficient to stably abrogate HLA class I expression by expressed viral IL-10. 13) are also frequent, leading to MHC class II downregulation. These genetic lesions are also identified in MGZL, indicating a molecular continuum between the 2 entities [

18,

23].

5.2. Specific Epigenetic as Well as Gene Expression Profiles

At the genomic level, large-scale methylation profiling has shown that MGZL has an epigenetic signature intermediate between CHL and PMBL, but distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS (DLBCL, NOS) [

13,

22]. In particular, hypomethylation of HOXA5 has been recognized as a typical characteristic of MGZL [

13]. Other differently expressed genes, including MMP9, EPHA7, and DAPK1, are involved in different molecular clustering and can distinguish among MGZL, CHL, and PMBL [

23].

5.3. Copy Number Alterations and Structural Variants

Gains at the REL locus (2p16. 1 (~33% of cases) and of the MYC locus (8q24, 27% of cases) have been identified [

22]. These changes might contribute to the aggressive biology of MGZL compared with PMBL or CHL. In conjunction with JAK2/PD-L1/PD-L2 amplifications, these results present a molecular rationale underlying the response of MGZL to immune checkpoint inhibitors [

24,

25].

5.4. Mutational Landscape

NGS-based analyses have revealed that MGZL harbors recurrent mutations affecting key pathways such as JAK/STAT, NF-κB, and antigen presentation [

2,

26]. The most frequently mutated genes are summarized in

Table 2.

These modifications indicate the involvement of the JAK-STAT, NF-κB and antigen presentation pathways. Notably, among cases with MGZL phenotype but not satisfying the diagnostic criterion for mediastinal involvement (historically categorized as GZL), there is an independent mutational profile with higher rates of TP53 (39%), BCL2 (28%), and BIRC6 (22%) mutations and more frequent BCL2/BCL6 rearrangements [

9]. This dissociation at the molecular level supports the current ICC and WHO-HEMA5 limitation of the GZL category to EBV-negative mediastinal tumors only [

15].

5.5. Tumor Microenvironment and Epigenetic Plasticity

Gene expression profiling analyses additionally underscore the TME as a hallmark of MGZL biology. In MGZL, but not CHL or PMBL, there are more regulatory macrophages and immune checkpoint molecules PD-1, -L1 and LAG3 are differentially expressed [

28]. High-coverage sequencing has also revealed a remarkably subclonal architecture as mutations (e.g., SOCS1, B2M, TNFAIP3) fulfill their driver potential in different clones under therapeutic selection, indicative that clonal heterogeneity, and epigenetic plasticity may contribute to resistance to drugs and disease relapse [

2,

14].

6. Comparison of MGZL with PMBL and CHL

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) occupies a biological and clinical continuum between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), particularly the nodular sclerosis subtype. While all three entities share origin from thymic B cells, they diverge in their morphology, immunophenotype, molecular characteristics, and clinical presentation [

13,

19,

29,

30]. These comparative features are summarized in

Table 3.

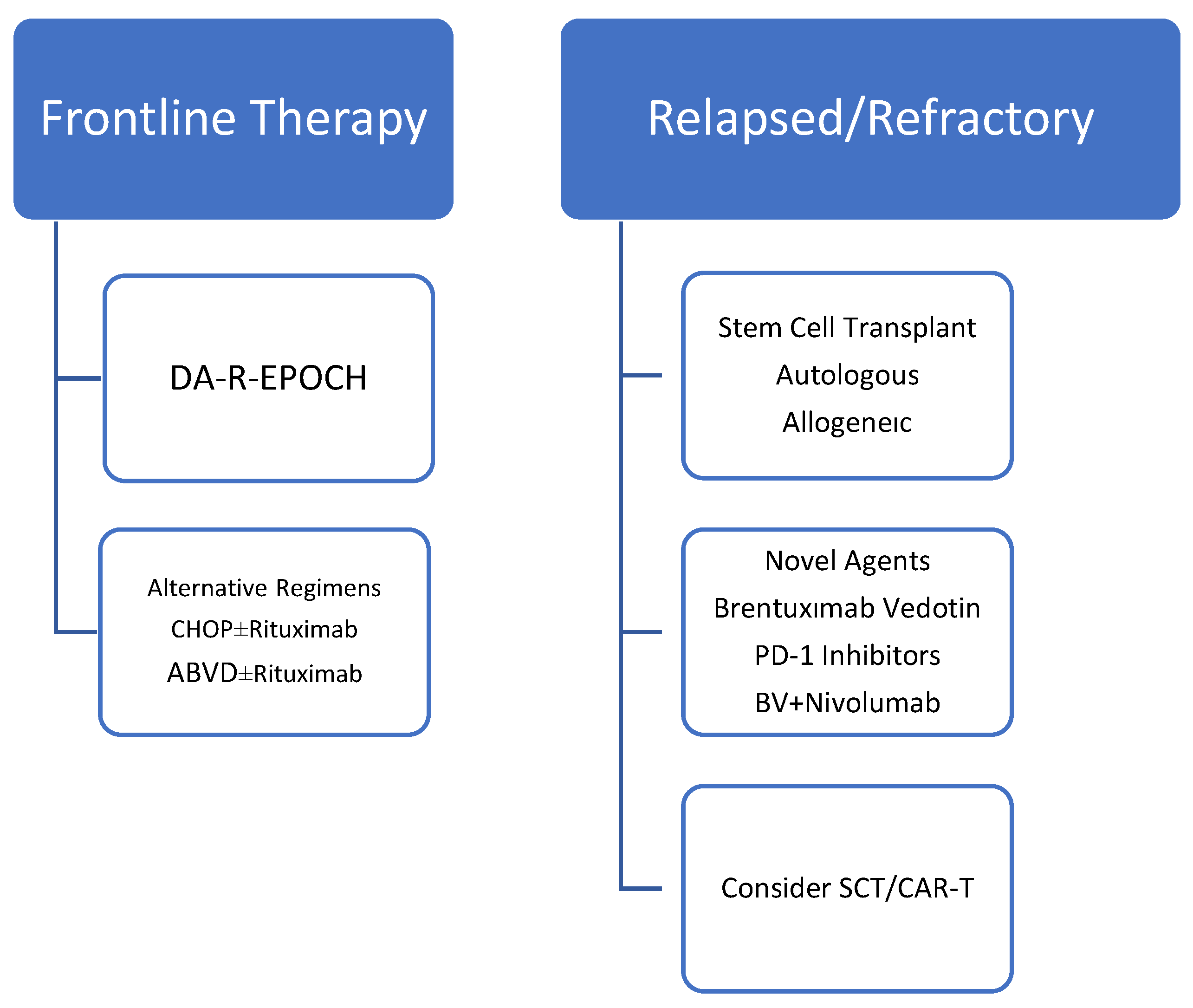

7. Treatment Approaches

The management of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) remains challenging due to its rarity, biological heterogeneity, and lack of standardized therapeutic guidelines. Historically, treatment strategies have mirrored those for PMBL or CHL, but outcomes in MGZL have generally been inferior to either entity [

31]. The overall treatment approach for MGZL is summarized in

Figure 1.

7.1. Frontline Therapy

In a recent NCDB population-based analysis including 1047 GZL patients, combined modality treatment was associated with superior survival compared to chemotherapy alone (HR 0.54, p=0.005). However, details regarding salvage therapy and transplantation were not available in the dataset, limiting conclusions about the role of autologous or allogeneic SCT in this cohort [

27].

Early studies from the National Institutes of Health evaluated dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (DA-EPOCH-R) in untreated MGZL patients, reporting a 5-year event-free survival (EFS) of 62% and overall survival (OS) of 74% [

22]. These results were better than those achieved with R-CHOP but inferior compared to PMBL treated with DA-EPOCH-R (5-year EFS ~93%, OS ~97%) [

31,

32].

Alternative regimens such as CHOP ± rituximab and ABVD ± rituximab have also been studied in small retrospective series. Pilichowska et al. reported overall response rates (ORR) of 65% for CHOP ± R and 60% for ABVD ± R, while DA-EPOCH-R achieved an ORR of 70% [

19]. However, progression-free survival was significantly inferior for patients treated with ABVD compared to CHOP-based therapy [

32].

More dose-intensive regimens such as escBEACOPP and ACBVP were evaluated in European cohorts, showing promising 3-year EFS (73–74%) and OS (86–94%), though these results likely reflect patient selection with good performance status [

33].

7.2. Role of Radiotherapy

The use of radiotherapy in MGZL remains controversial. It has been employed as consolidation following chemotherapy, particularly for localized or bulky disease, but the limited patient numbers preclude definitive conclusions [

34].

7.3. Response Assesment

Assessment of response in mediastinal gray-zone lymphoma (MGZL) largely parallels strategies used in other FDG-avid lymphomas, yet entails special caveats given the frequent presence of residual fibrotic mediastinal tissue and heterogeneous metabolic patterns. Functional imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT is considered the backbone of response assessment (both interim and end-of-therapy), since metabolic criteria better distinguish viable disease from post-treatment fibrosis than purely anatomic size changes (e.g. CT) [

35]. Many centers apply the Deauville 5-point scoring system to grade residual uptake relative to mediastinal and hepatic background (scores 1–3 often considered negative, 4–5 positive), though interpretation of score 3 requires clinical judgment in borderline cases [

36]. In MGZL, residual mediastinal masses are common even in remission, underscoring that persistent mass alone is not sufficient to infer treatment failure; metabolic negativity is more informative. In equivocal cases—especially when PET remains indeterminate—biopsy confirmation may be needed to distinguish residual viable lymphoma from fibrotic scar or inflammation. In the limited prospective MGZL literature, PET-based criteria have guided salvage decisions (e.g. involved-field radiotherapy) in patients with PET-positive residual disease [

6]. Emerging studies have also begun exploring the prognostic value of early PET negativity (e.g. after 2–4 cycles) to refine risk-adapted therapy, though data remain sparse in MGZL specifically, because MGZL lies at the interface of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin biology, PET findings must be integrated in the context of baseline disease metabolic heterogeneity, clinical features, and morphologic correlates [

37].

7.4. Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Disease and Stem Cell Transplantation

R/R MGZL has historically been treated with salvage chemotherapy regimens such as ICE, ESHAP, and gemcitabine-based combinations, frequently followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). In large series, the 2-year OS after HSCT was ~88% compared to 67% without HSCT, highlighting the importance of transplantation in chemosensitive patients [

39,

41]. Selected patients have also undergone allogeneic SCT in the relapsed setting.

7.5. Novel Agents and Biologic Therapy

Given the frequent CD30 expression and the 9p24.1 alterations leading to PD-1/PD-L1 upregulation, MGZL is a rational target for antibody–drug conjugates and immune checkpoint inhibitors [

40]. Brentuximab vedotin (BV): Effective as a single agent in case reports and small series, and has also been employed as maintenance therapy following ASCT [

39,

41]. In addition to its direct anti-CD30 activity, BV may contribute to immunomodulation by depleting regulatory T cells, thereby enhancing the effect of checkpoint blockade. PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab): Demonstrated clinical activity in relapsed/refractory MGZL, with responses resembling those observed in CHL and PMBL [

40]. BV + Nivolumab Combination: The

CheckMate 436 trial investigated this regimen in patients with R/R MGZL, reporting an overall response rate (ORR) of 70% and a complete remission (CR) rate of 50%, with durable responses (median PFS ~22 months) and a favorable safety profile [

41]. Importantly, this combination enabled a proportion of patients to proceed to SCT, highlighting its potential as an effective bridge-to-transplant strategy. The activity of novel agents in R/R MGZL is summarized in

Table 4.

7.6. Emerging Strategies

Although experience is still limited, CAR-T cell therapy and bispecific antibodies are under investigation, leveraging the overlap of MGZL with other aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Given the highly subclonal structure and plasticity of MGZL, integration of molecularly guided therapies and immunotherapy-based regimens represents a promising direction for future management [

42].

8. Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) is generally inferior to that of PMBL and CHL, reflecting its aggressive clinical behavior and lack of standardized therapeutic approaches. While complete remissions can be achieved with intensive chemoimmunotherapy regimens, long-term outcomes remain suboptimal [

13,

19].

9. Overall Survival and Event-Free Survival

Across multiple series, the 5-year overall survival (OS) for MGZL ranges between 40–60%, significantly lower than the outcomes reported for PMBL (>85–90%) or CHL (>80–85%) in the modern era [

15,

22,

27]. Event-free survival (EFS) similarly lags behind, with reported 5-year rates of ~60% following DA-EPOCH-R, compared to >90% in PMBL [

31].

10. Predictors of Outcome

Morphologic and molecular profile: Discordance between histopathologic features and molecular clustering has been associated with poorer treatment response and survival [

4].

Treatment regimen: Patients treated with ABVD-based therapy generally have inferior outcomes compared to those receiving CHOP- or EPOCH-based regimens [

19,

31,

32].

Stage and bulk: Advanced stage (III/IV), bulky mediastinal disease, and extranodal involvement at diagnosis are linked with worse prognosis [

16].

Transplantation: In the relapsed/refractory setting, outcomes are significantly better for patients able to undergo autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), with a 2-year OS of 88% compared to 67% without ASCT [

41,

42].

Relapsed/Refractory Disease

R/R MGZL carries particularly poor outcomes, with median progression-free survival often <12 months following salvage chemotherapy alone. Incorporation of novel biologics such as brentuximab vedotin (BV) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) has shown promise, but data are still limited to small series and clinical trials [

38].

Comparison with Related Entities

The inferior prognosis of MGZL compared to PMBL and CHL underscores its biological distinctiveness. While PMBL treated with DA-EPOCH-R achieves 5-year OS of ~97% and CHL with ABVD-based regimens exceeds 80–85%, MGZL continues to show relapse rates exceeding 40% and lower survival, highlighting the urgent need for optimized treatment strategies [

19,

31,

32].

11. Future Directions

Despite significant progress in the recognition and characterization of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL), major challenges remain in its management. Future research should aim to refine diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment, and explore novel therapeutic avenues.

11.1. Diagnostic Refinement

The overlap of morphologic and immunophenotypic features between MGZL, PMBL, and CHL continues to complicate diagnosis. Wider integration of molecular profiling, DNA methylation studies, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) could facilitate more precise classification. Predictive biomarkers, including immune checkpoint–related gene alterations and tumor microenvironment (TME) signatures, may improve risk stratification and guide therapy.

11.2. Prospective Clinical Trials

To date, evidence for MGZL treatment is largely derived from retrospective cohorts and small prospective series. Given the rarity of the disease, international collaborative trials are essential to establish standard-of-care regimens and to clarify the role of intensive chemotherapy, consolidative radiotherapy, and stem cell transplantation.

11.3. Immunotherapy and Targeted Approaches

The frequent CD30 expression and 9p24.1/PD-L1/PD-L2 alterations make MGZL an ideal candidate for biologic therapies.

Antibody–drug conjugates (Brentuximab vedotin), either alone or in combination, have demonstrated efficacy, especially in relapsed/refractory disease.

PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) show promising results, particularly when combined with BV.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies represent emerging options, though current data remain limited.

11.4. Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Studies

Recent insights into the predominance of regulatory macrophages and differential expression of checkpoint molecules in MGZL suggest that the TME may significantly influence prognosis and therapeutic response. Application of single-cell technologies and spatial transcriptomics may uncover novel targets and resistance mechanisms.

11.5. Personalized Therapy

The highly subclonal architecture of MGZL revealed by genomic studies suggests that clonal evolution contributes to therapeutic resistance. Future strategies may need to incorporate dynamic molecular monitoring and personalized treatment algorithms that adapt to evolving tumor biology.

12. Conclusion

Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL) represents a rare but clinically significant entity at the intersection of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL). Since its first recognition in 1998 and subsequent inclusion in the WHO classification, the definition of MGZL has evolved, culminating in the most recent restriction by WHO-HEMA5 and ICC to EBV-negative mediastinal tumors with overlapping features of CHL and PMBL.

The diagnostic challenges posed by morphologic and immunophenotypic heterogeneity, combined with the absence of standardized therapeutic guidelines, contribute to the generally inferior outcomes observed in MGZL compared with PMBL or CHL. While intensive chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as DA-EPOCH-R have improved responses, relapse rates remain high and long-term survival unsatisfactory.

Recent advances in molecular profiling and the application of novel biologics—notably brentuximab vedotin and PD-1 inhibitors—have opened new therapeutic avenues, particularly in relapsed/refractory disease. However, current knowledge is limited by small series and retrospective studies.

Future progress will depend on international collaboration, prospective clinical trials, and integration of molecular diagnostics to refine classification and personalize treatment strategies. Ultimately, combining conventional chemotherapy with immunotherapy and targeted approaches may offer the most promise in improving the prognosis of patients with this diagnostically and therapeutically challenging lymphoma.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.Z., M.S., N.A., T.U., M.S.D.; Methodology: T.Z., M.S., N.A., T.U., M.S.D.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.Z., M.S., N.A., T.U., M.S.D.; writing—review and editing, T.Z., M.S., N.A., T.U., M.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D, Calaminici M, Chadburn A, Chan JKC, Cheuk W, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Chuang SS, Coupland SE, Czader M, Dave SS, de Jong D, Du MQ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Ferry J, Geyer J, Gratzinger D, Guitart J, Gujral S, Harris M, Harrison CJ, Hartmann S, Hochhaus A, Jansen PM, Karube K, Kempf W, Khoury J, Kimura H, Klapper W, Kovach AE, Kumar S, Lazar AJ, Lazzi S, Leoncini L, Leung N, Leventaki V, Li XQ, Lim MS, Liu WP, Louissaint A Jr, Marcogliese A, Medeiros LJ, Michal M, Miranda RN, Mitteldorf C, Montes-Moreno S, Morice W, Nardi V, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Ng SB, Oschlies I, Ott G, Parrens M, Pulitzer M, Rajkumar SV, Rawstron AC, Rech K, Rosenwald A, Said J, Sarkozy C, Sayed S, Saygin C, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Sohani AR, Tooze R, Traverse-Glehen A, Vega F, Vergier B, Wechalekar AD, Wood B, Xerri L, Xiao W. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022; 36(7): 1720-1748. Erratum in: Leukemia. 2023; 37(9): 1944-1951.

- Campo E, Jaffe ES, Cook JR, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Swerdlow SH, Anderson KC, Brousset P, Cerroni L, de Leval L, Dirnhofer S, Dogan A, Feldman AL, Fend F, Friedberg JW, Gaulard P, Ghia P, Horwitz SM, King RL, Salles G, San-Miguel J, Seymour JF, Treon SP, Vose JM, Zucca E, Advani R, Ansell S, Au WY, Barrionuevo C, Bergsagel L, Chan WC, Cohen JI, d'Amore F, Davies A, Falini B, Ghobrial IM, Goodlad JR, Gribben JG, Hsi ED, Kahl BS, Kim WS, Kumar S, LaCasce AS, Laurent C, Lenz G, Leonard JP, Link MP, Lopez-Guillermo A, Mateos MV, Macintyre E, Melnick AM, Morschhauser F, Nakamura S, Narbaitz M, Pavlovsky A, Pileri SA, Piris M, Pro B, Rajkumar V, Rosen ST, Sander B, Sehn L, Shipp MA, Smith SM, Staudt LM, Thieblemont C, Tousseyn T, Wilson WH, Yoshino T, Zinzani PL, Dreyling M, Scott DW, Winter JN, Zelenetz AD. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood. 2022 15;140(11):1229-1253. Erratum in: Blood. 2023 26;141(4):437.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th Edition ed. Lyon: IARC; 2017.

- Pilichowska M, Pittaluga S, Ferry JA, Hemminger J, Chang H, Kanakry JA, Sehn LH, Feldman T, Abramson JS, Kritharis A, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Lossos IS, Press OW, Fenske TS, Friedberg JW, Vose JM, Blum KA, Jagadeesh D, Woda B, Gupta GK, Gascoyne RD, Jaffe ES, Evens AM. Clinicopathologic consensus study of gray zone lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and classical HL. Blood Adv. 2017; 1(26): 2600-2609. [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy K, Wilson WH. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: do they require a unique therapeutic approach? Blood. 2015 1;125(1):33-9. [CrossRef]

- Wilson WH, Pittaluga S, Nicolae A, Camphausen K, Shovlin M, Steinberg SM, Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Jaffe ES, Dunleavy K. A prospective study of mediastinal gray-zone lymphoma. Blood. 2014 4;124(10):1563-9. [CrossRef]

- Rüdiger T, Jaffe ES, Delsol G, deWolf-Peeters C, Gascoyne RD, Georgii A, Harris NL, Kadin ME, MacLennan KA, Poppema S, Stein H, Weiss LE, Müller-Hermelink HK. Workshop report on Hodgkin's disease and related diseases ('grey zone' lymphoma). Ann Oncol. 1998;9 Suppl 5:S31-8.

- Traverse-Glehen A, Pittaluga S, Gaulard P, Sorbara L, Alonso MA, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: the missing link between classic Hodgkin's lymphoma and mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 ;29(11):1411-21.

- Poppema S, Kluiver JL, Atayar C, van den Berg A, Rosenwald A, Hummel M, Lenze D, Lammert H, Stein H, Joos S, Barth T, Dyer M, Lichter P, Klein U, Cattoretti G, Gloghini A, Tu Y, Stolovitzky GA, Califano A, Carbone A, Dalla-Favera R, Melzner I, Bucur AJ, Brüderlein S, Dorsch K, Hasel C, Barth TF, Leithäuser F, Möller P. Report: workshop on mediastinal grey zone lymphoma. Eur J Haematol Suppl. 2005 ;(66):45-52. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, E.S.; Harris, N.L.; Stein, H.; Campo, E.; Stefano Pileri, S.A.; Swerdlow, S.H. B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed.; Swerdlow, S.H., Campo, E., Harris, N.L., Jaffe, E.S., Pileri, S.A., Stein, H., Thiele, J., Vardiman, J.W., Eds.; IARC press: Lyon, France, 2008; pp. 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, E.S.; Stein, H.; Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Pileri, S.A.; Harris, N.L. B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues; Revised fourth, edition, Swerdlow, S.H., Campo, E., Harris, N.L., Jaffe, E.S., Pileri, S.A., Stein, H., Thiele, J., Arber, D.A., Hasserjian, R.P., Le Beau, M.M., et al., Eds.; IARC press: Lyon, France, 2017; pp. 342–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kritharis A, Pilichowska M, Evens AM. How I manage patients with grey zone lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016 ;174(3):345-50.

- Pilichowska M, Pittaluga S, Ferry JA, Hemminger J, Chang H, Kanakry JA, Sehn LH, Feldman T, Abramson JS, Kritharis A, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Lossos IS, Press OW, Fenske TS, Friedberg JW, Vose JM, Blum KA, Jagadeesh D, Woda B, Gupta GK, Gascoyne RD, Jaffe ES, Evens AM. Clinicopathologic consensus study of gray zone lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and classical HL. Blood Adv. 2017 11;1(26):2600-2609.

- Sarkozy C, Chong L, Takata K, Chavez EA, Miyata-Takata T, Duns G, Telenius A, Boyle M, Slack GW, Laurent C, Farinha P, Molina TJ, Copie-Bergman C, Damotte D, Salles GA, Mottok A, Savage KJ, Scott DW, Traverse-Glehen A, Steidl C. Gene expression profiling of gray zone lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020 9;4(11):2523-2535.

- Sarkozy C, Hung SS, Chavez EA, Duns G, Takata K, Chong LC, Aoki T, Jiang A, Miyata-Takata T, Telenius A, Slack GW, Molina TJ, Ben-Neriah S, Farinha P, Dartigues P, Damotte D, Mottok A, Salles GA, Casasnovas RO, Savage KJ, Laurent C, Scott DW, Traverse-Glehen A, Steidl C. Mutational landscape of gray zone lymphoma. Blood. 2021 1;137(13):1765-1776.

- Pileri, S.; Tabanelli, V.; Chiarle, R.; Calleri, A.; Melle, F.; Motta, G.; Sapienza, M.R.; Sabattini, E.; Zinzani, P.L.; Derenzini, E. Mediastinal Gray-Zone Lymphoma: Still an Open Issue. Hemato 2023, 4, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th Edition ed. Lyon: IARC; 2017.

- Sarkozy C, Copie-Bergman C, Damotte D, Ben-Neriah S, Burroni B, Cornillon J, Lemal R, Golfier C, Fabiani B, Chassagne-Clément C, Parrens M, Herbaux C, Xerri L, Bossard C, Laurent C, Cheminant M, Cartron G, Cabecadas J, Molina T, Salles G, Steidl C, Ghesquières H, Mottok A, Traverse-Glehen A. Gray-zone Lymphoma Between cHL and Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Histopathologic Series From the LYSA. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(3):341-351.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, de Jong D, de Mascarel A, Hsi ED, Kluin P, Natkunam Y, Parrens M, Pileri S, Ott G. Gray zones around diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Conclusions based on the workshop of the XIV meeting of the European Association for Hematopathology and the Society of Hematopathology in Bordeaux, France. J Hematop. 2009 22;2(4):211-36.

- Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011 12;117(19):5019-32. [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, Yu X, Gaulard P, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Zhao T, Haioun C, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Lynch JC, Vose J, Armitage JO, Smeland EB, Kvaloy S, Holte H, Delabie J, Campo E, Montserrat E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Connors JM, Braziel R, Grogan TM, Fisher RI, Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Chiorazzi M, Zhao H, Yang L, Powell J, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES, Simon R, Klausner RD, Staudt LM. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003 15;198(6):851-62.

- Egan C, Pittaluga S. Into the gray-zone: update on the diagnosis and classification of a rare lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020 ;13(1):1-3.

- Eberle FC, Rodriguez-Canales J, Wei L, Hanson JC, Killian JK, Sun HW, Adams LG, Hewitt SM, Wilson WH, Pittaluga S, Meltzer PS, Staudt LM, Emmert-Buck MR, Jaffe ES. Methylation profiling of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma reveals a distinctive signature with elements shared by classical Hodgkin's lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2011 ;96(4):558-66. [CrossRef]

- Tabanelli V, Melle F, Motta G, Mazzara S, Fabbri M, Agostinelli C, Calleri A, Del Corvo M, Fiori S, Lorenzini D, Cesano A, Chiappella A, Vitolo U, Derenzini E, Griffin GK, Rodig SJ, Vanazzi A, Sabattini E, Tarella C, Sapienza MR, Pileri SA. The identification of TCF1+ progenitor exhausted T cells in THRLBCL may predict a better response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Blood Adv. 2022 9;6(15):4634-4644.

- Steidl C, Gascoyne RD. The molecular pathogenesis of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011 8;118(10):2659-69.

- Campo E, Jaffe ES. Taking gray zone lymphomas out of the shadows. Blood. 2021 1;137(13):1703-1704. [CrossRef]

- Samhouri Y, Jayakrishnan TT, Alnimer L, Bakalov V, Wegner RE, Khan C, Fazal S, Lister J. Treatment Selection and Survival in Patients with Gray Zone Lymphoma: A Comprehensive Population-Based Analysis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2023 4;16(3):245-253.

- Gargano G, Vegliante MC, Esposito F, Pappagallo SA, Sabattini E, Agostinelli C, Pileri SA, Tabanelli V, Ponzoni M, Lorenzi L, Facchetti F, Di Napoli A, Lucioni M, Paulli M, Leoncini L, Lazzi S, Ascani S, Opinto G, Zaccaria GM, Volpe G, Mondelli P, Bucci A, Selicato L, Negri A, Loseto G, Clemente F, Scattone A, Zito AF, Nassi L, Del Buono N, Guarini A, Ciavarella S. A targeted gene signature stratifying mediastinal gray zone lymphoma into classical Hodgkin lymphoma-like or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma-like subtypes. Haematologica. 2024 1;109(11):3771-3775. [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma. Haematologica. 2011 Apr;96(4):496-9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.043026. PMID: 21454881; PMCID: PMC3069224.30.

- Higgins JP, Warnke RA. CD30 expression is common in med iastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:241–247. [CrossRef]

- Wilson WH, Pittaluga S, Nicolae A, Camphausen K, Shovlin M, Steinberg SM, Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Jaffe ES, Dunleavy K. A prospective study of mediastinal gray-zone lymphoma. Blood. 2014 4;124(10):1563-9. [CrossRef]

- Pilichowska M, Kritharis A, Evens AM. Gray Zone Lymphoma: Current Diagnosis and Treatment Options. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016 ;30(6):1251-1260.

- Sarkozy C, Hung SS, Chavez EA, Duns G, Takata K, Chong LC, Aoki T, Jiang A, Miyata-Takata T, Telenius A, Slack GW, Molina TJ, Ben-Neriah S, Farinha P, Dartigues P, Damotte D, Mottok A, Salles GA, Casasnovas RO, Savage KJ, Laurent C, Scott DW, Traverse-Glehen A, Steidl C. Mutational landscape of gray zone lymphoma. Blood. 2021 1;137(13):1765-1776.

- Zinzani PL, Martelli M, Magagnoli M, Pescarmona E, Scaramucci L, Palombi F, Bendandi M, Martelli MP, Ascani S, Orcioni GF, Pileri SA, Mandelli F, Tura S. Treatment and clinical management of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma with sclerosis: MACOP-B regimen and mediastinal radiotherapy monitored by (67)Gallium scan in 50 patients. Blood. 1999 15;94(10):3289-93.

- Cavalli F, Ceriani L, Zucca E. Functional Imaging Using 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET in the Management of Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The Contributions of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e368-75. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_159037. PMID: 27249743.

- Plastaras JP, Svoboda J. PET/CT Responses in Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma: What's Negative? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021 1;111(3):595-596.

- Menguc MU, Arikan F, Toptas T, Medıastınal Gray Zone Lymphoma; Shades Of Gray, Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy, Volume 46, Supplement 3, 2024, Pages 18-19, ISSN 2531-1379.

- Evens AM, Kanakry JA, Sehn LH, Kritharis A, Feldman T, Kroll A, Gascoyne RD, Abramson JS, Petrich AM, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Al-Mansour Z, Adeimy C, Hemminger J, Bartlett NL, Mato A, Caimi PF, Advani RH, Klein AK, Nabhan C, Smith SM, Fabregas JC, Lossos IS, Press OW, Fenske TS, Friedberg JW, Vose JM, Blum KA. Gray zone lymphoma with features intermediate between classical Hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: characteristics, outcomes, and prognostication among a large multicenter cohort. Am J Hematol. 2015 ;90(9):778-83.

- Kritharis A, Pilichowska M, Evens AM. How I manage patients with grey zone lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016 ;174(3):345-50. [CrossRef]

- Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, Juszczynski P, Currie T, O'Donnell E, Chapuy B, Takeyama K, Neuberg D, Golub TR, Kutok JL, Shipp MA. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010 28;116(17):3268-77.

- Santoro A, Moskowitz AJ, Ferrari S, Carlo-Stella C, Lisano J, Francis S, Wen R, Akyol A, Savage KJ. Nivolumab combined with brentuximab vedotin for relapsed/refractory mediastinal gray zone lymphoma. Blood. 2023 1;141(22):2780-2783. [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla J. Targeted therapy in mediastinal gray zone lymphoma. Blood. 2023 1;141(22):2673-2674. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).