1. Introduction

The proliferation of fake news across digital platforms has emerged as a significant global concern, influencing public opinion, undermining democratic processes, and exacerbating social tensions. Traditional fact-checking methods, while accurate, are not scalable in the face of the massive and rapid spread of misinformation online. Consequently, the research community has increasingly turned to Artificial Intelligence (AI) for automated fake news detection solutions. In recent years, Large Language Models (LLMs) such as BERT, RoBERTa, and GPT-based architectures have demonstrated remarkable performance in a wide range of natural language understanding tasks, including fake news detection (Zhou et al., 2020; Kaliyar et al., 2021). These models excel in capturing contextual semantics and subtle linguistic cues that are often indicative of deceptive content. However, despite their high accuracy, such models are often criticized for their lack of interpretability, functioning as black boxes that provide predictions without transparent reasoning.

The opacity of LLMs poses critical challenges in high-stakes applications like misinformation detection, where understanding why a model classifies a piece of news as fake is as important as the classification itself. Without interpretability, it becomes difficult to build user trust, ensure ethical accountability, or detect potential biases in the model’s decisions (Samek et al., 2021; Jacovi & Goldberg, 2020). To address these challenges, recent research has focused on explainable AI (XAI) techniques that aim to make LLMs more transparent by uncovering the internal reasoning behind their predictions. Tools such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), and attention visualization have been applied to language models to highlight the most influential features in a decision (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Lundberg & Lee, 2017; Vig, 2019). However, their integration into fake news detection pipelines remains limited and underexplored.

This study aims to bridge this gap by proposing a framework that combines the predictive power of LLMs with interpretability techniques to improve both the performance and trustworthiness of fake news detection systems. Specifically, we explore how explanations generated by LLMs can assist human users—journalists, analysts, and the public—in understanding and trusting the system's outputs. Through a combination of empirical evaluation and interpretability visualization, we demonstrate that “truth” in machine prediction is not only about accuracy but also about explainability.

In this study, we present a comprehensive and hybrid framework that not only leverages the high accuracy of BERT in detecting fake news, but also enhances the transparency of the model’s decision-making by integrating two distinct interpretability methods (LIME and BERT attention analysis) simultaneously. Unlike previous studies that usually employ only one interpretability method, our approach analyzes decision-making from both local and structural perspectives. Furthermore, the framework is implemented on data related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which is socially sensitive and requires stronger interpretability. This combination provides a better understanding of the linguistic factors influencing fake news detection and increases end-user trust.

2. Related Work

Fake news detection has emerged as a critical challenge in natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning, due to the rapid spread of misinformation online. Over the past few years, numerous studies have explored novel methods to identify fake news and assess its societal impact. Recent reviews have highlighted both the promise and limitations of advanced machine learning and NLP models, while emphasizing challenges such as adversarial attacks and data scarcity (Thakar, 2024).

Text-to-image transformations have been proposed to enhance feature representation, improving the performance of machine learning models in fake news detection and achieving superior results compared to traditional approaches (Rustam, 2024). Additionally, comprehensive surveys have underlined the importance of multidisciplinary approaches and interpretable models for robust detection systems (Harris, 2024). Real-time detection frameworks leveraging cloud computing and CRISP-DM methodology have also demonstrated the feasibility of combining multiple approaches to achieve timely and accurate results (Cavus, 2024).

More recent work has focused on analyzing the intrinsic characteristics of fake news, highlighting the importance of understanding linguistic, semantic, and contextual features for accurate detection (Hu, 2025). Data analytics and machine learning techniques have been applied to study the impact of fake news and deepfake content on public behavior and trust, providing valuable insights into misinformation dynamics (Abraham, 2025). Large language models (LLMs) such as BERT and GPT variants have been increasingly explored for fake news detection, showing significant improvements in detection accuracy and multilingual capabilities (Al-alshaqi, 2025). Collectively, these studies underscore the growing importance of advanced methodologies and integrated frameworks for detecting fake news.

2.1. Traditional Approaches to Fake News Detection

Early methods relied heavily on feature engineering and shallow machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naive Bayes, and Random Forests. These approaches leveraged lexical, syntactic, and stylistic cues, such as n-grams, TF-IDF scores, and readability indices, to differentiate between real and fake content (Shu et al., 2017). While interpretable and computationally efficient, these methods often lacked generalizability and semantic understanding, particularly in complex or subtle misinformation cases. Furthermore, handcrafted features were frequently domain-specific and failed to capture the evolving nature of online discourse (Zhou et al., 2020).

2.2. Deep Learning and LLMs for Fake News Detection

Building upon traditional methods, deep learning approaches—especially Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—marked a significant advancement in fake news detection. More recently, transformer-based LLMs, including BERT (Devlin et al., 2019), RoBERTa (Liu et al., 2019), XLNet (Yang et al., 2020), and GPT variants (Brown et al., 2020), have achieved state-of-the-art performance. Pre-trained on massive corpora and fine-tuned for fake news tasks, these models demonstrate high accuracy across benchmark datasets. For instance, FakeBERT, a fine-tuned BERT model, significantly outperformed traditional methods on LIAR and FakeNewsNet datasets (Kaliyar et al., 2021), while RoBERTa achieved strong results in multilingual misinformation detection (Nasir et al., 2022). Despite these advances, model interpretability remains a major concern.

2.3. Explainability in NLP and LLMs

To address the “black-box” nature of LLMs, various Explainable AI (XAI) techniques have been introduced:

Attention visualization: Internal attention weights of transformer layers highlight which words the model focuses on (Vig, 2019).

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Perturbs input texts and trains local interpretable models to approximate predictions (Ribeiro et al., 2016).

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): A game-theoretic method estimating feature contributions to model output (Lundberg & Lee, 2017).

Integrated Gradients and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP): Attribute model predictions to specific inputs using backpropagation-based techniques (Sundararajan et al., 2017).

Although these methods exist, their application in fake news detection—particularly alongside LLMs—remains relatively underexplored.

2.4. The Accuracy-Interpretability Tradeoff

A persistent challenge is the tradeoff between predictive performance and transparency. Highly accurate models such as BERT and GPT often provide limited insight into why a prediction was made, raising concerns about trustworthiness, bias, and ethical implications (Doshi-Velez & Kim, 2017; Jacovi & Goldberg, 2020). While some studies attempt to visualize attention or use post-hoc explanation tools, these efforts frequently fall short of producing faithful, user-centric interpretations. There is therefore a growing need for integrated frameworks that balance accuracy with interpretability, especially in sensitive applications like fake news detection. This paper contributes to this direction by proposing a hybrid approach combining state-of-the-art LLMs with model-agnostic explanation tools.

3. Proposed Methodology

Our proposed framework integrates pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) with post-hoc explainability techniques to create a transparent and effective fake news detection system. The core idea is to leverage the superior predictive performance of LLMs like BERT while simultaneously providing interpretable explanations for their decisions. The framework consists of three main components: (1) the LLM-based classifier, (2) the explanation generation module, and (3) the visualization and analysis interface. This modular design allows for flexibility in choosing different LLMs and explanation methods, making the system adaptable to various datasets and requirements.

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

Our study utilizes the COVID-19 Fake News Dataset available on Kaggle1, which is specifically designed for detecting misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This dataset contains a collection of news articles labeled as either real or fake, providing a relevant and timely benchmark for our fake news detection framework. To prepare the data for our Large Language Model (LLM)-based classifier, we implement a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline:

Text Cleaning: Removal of special characters, and excessive whitespace to standardize the text format.

Handling Missing Data: Identification and appropriate handling of any missing values in the text or label columns.

Label Encoding: Conversion of categorical labels ('real', 'fake') into numerical format (0, 1) suitable for binary classification.

Tokenization: Utilization of the specific tokenizer associated with our chosen LLM (e.g., BERT tokenizer) to convert text into subword tokens.

Encoding: Transformation of tokenized text into input IDs and attention masks, which are the required numerical inputs for the transformer model.

Data Splitting: The train/test split was maintained, with part of the training set used for, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

This preprocessing ensures that the data is in an optimal format for feeding into the LLM, preserving the semantic integrity of the news articles while converting them into a structure the model can process effectively.

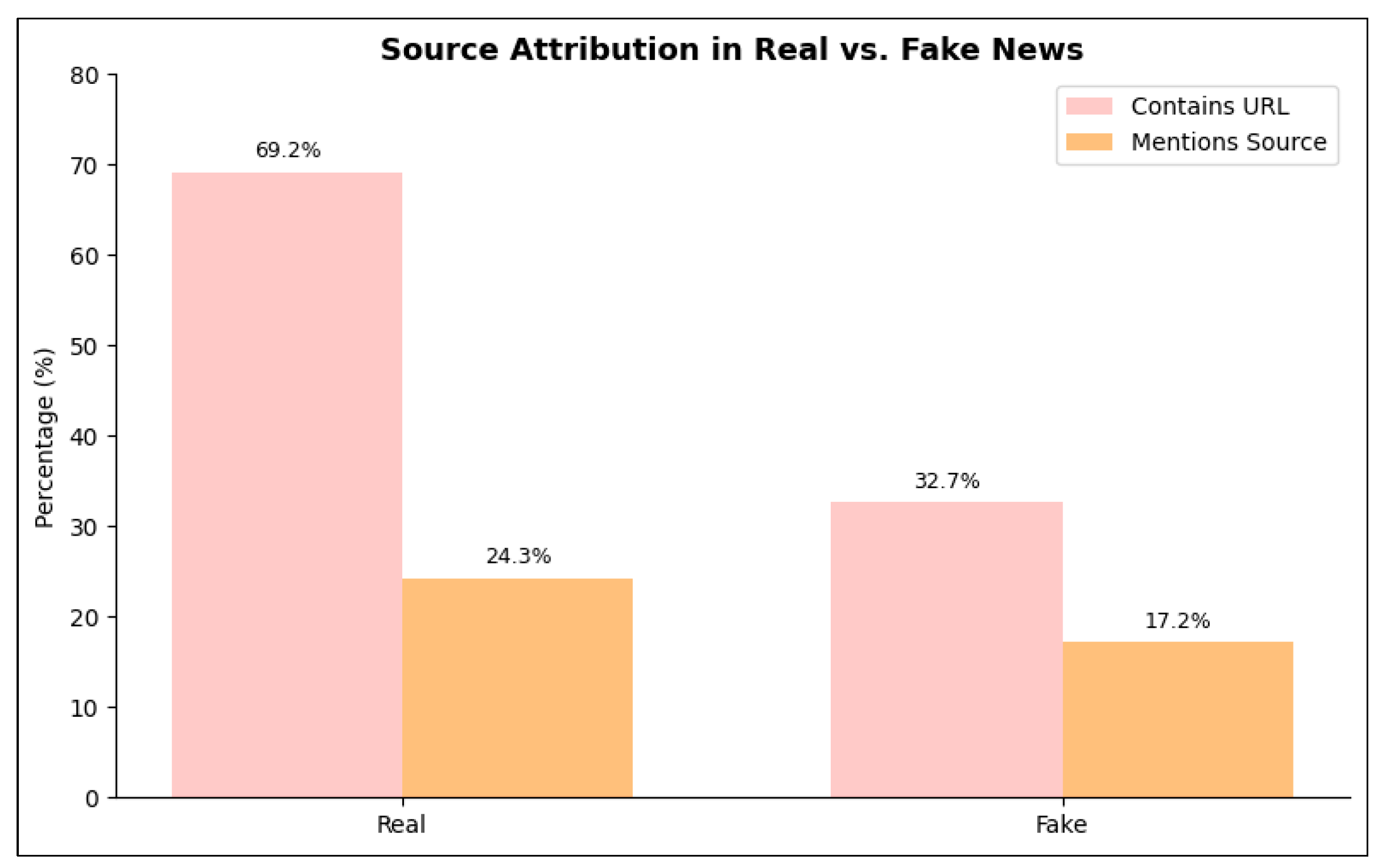

Our analysis reveals significant stylistic differences between real and fake news in the dataset. Real news articles are substantially longer (mean: 215 characters, 32 words) compared to fake news (mean: 145 characters, 22 words), suggesting that factual reporting tends to include more contextual details. Furthermore, real news is more likely to contain URLs (69.2% vs. 32.7%) and explicitly reference credible sources such as health organizations or scientific studies (24.3% vs. 17.2%). These patterns indicate that linguistic and structural features—beyond semantic content—can serve as valuable signals for fake news detection. The differences in URL presence and source citations are illustrated in

Figure 2.

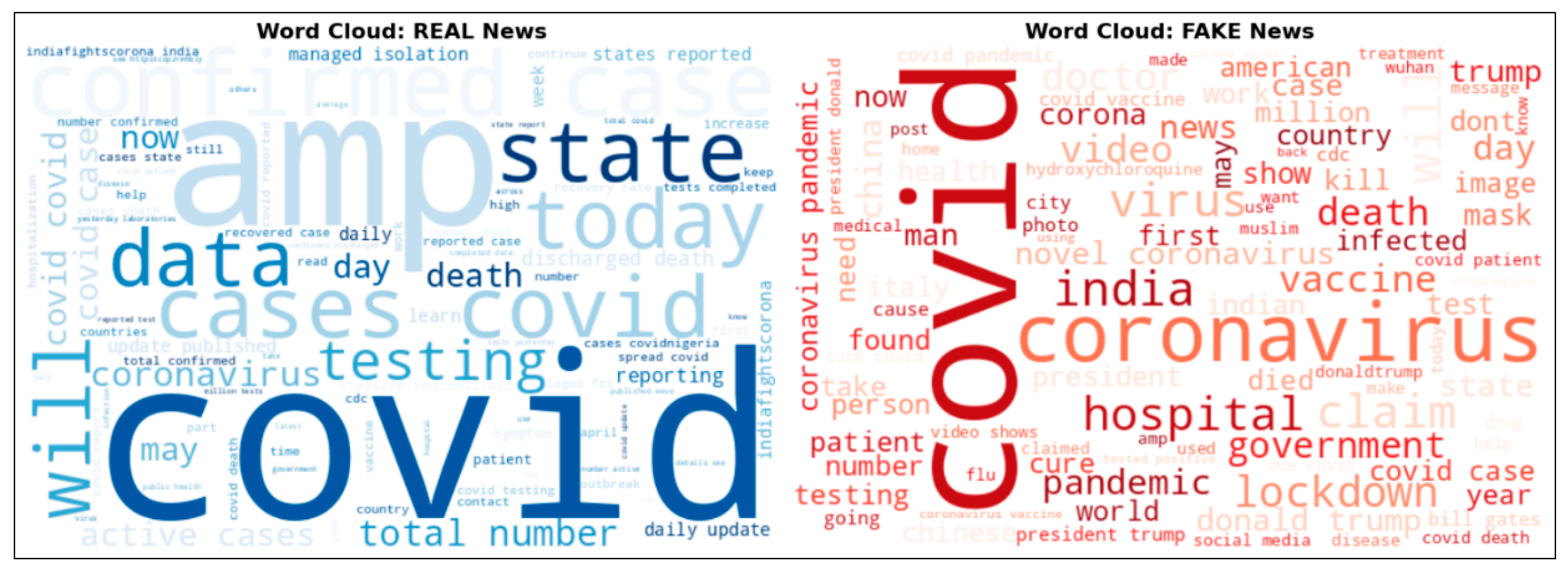

The observed differences in text length and source attribution highlight that fake news often relies on brevity and emotional appeal rather than evidence-based reporting. This reinforces the importance of incorporating both semantic understanding (via BERT) and surface-level features (e.g., URL presence, text length) into detection systems. the word clouds reveal distinct lexical patterns between real and fake news (

Figure 3). The word clouds reveal distinct lexical patterns between real and fake news. Real news predominantly features data-driven terms such as “cases,” “testing,” and “reported,” reflecting an emphasis on factual reporting and statistical updates. In contrast, fake news is characterized by emotionally charged vocabulary like “kill,” “death,” and “government conspiracy,” often targeting political figures (e.g., “Trump”) or promoting unverified cures (e.g., “hydroxychloroquine”). These findings suggest that linguistic cues — beyond semantic content — can serve as powerful indicators for automated detection systems.

3.2. Integration of Explainability Techniques

To make the LLM’s predictions more transparent, we leverage two complementary post-hoc explanation methods that provide insights at different levels:

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): A local interpretability method that quantifies the contribution of individual words or features to a specific prediction (Garreau & von Luxburg, 2020). This allows us to understand why the model classified a particular instance as fake or real.

BERT Attention Weights: A global, model-intrinsic approach that captures the interactions between tokens across layers and attention heads (Clark et al., 2019). By visualizing these token-to-token relationships, we can observe which parts of the input the model prioritizes when forming its predictions.

Together, these methods offer a comprehensive view of the model’s behavior, combining fine-grained, instance-level explanations with broader, sentence-level insights.

3.3. Implementation Details

We fine-tuned a transformer-based LLM, specifically BERT, for the binary classification task of fake news detection. The model was initialized with pre-trained weights (bert-base-uncased) and equipped with a classification head on top of the transformer layers. Input texts were preprocessed using the BERT tokenizer with padding and truncation (maximum sequence length = 256) to handle variable-length inputs, converting each text into token IDs and attention masks.

Training was performed using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-5, weight decay of 0.01, and a linear learning rate scheduler with warmup steps set to 10% of the total training steps. The model was trained for 3 epochs with a batch size of 16, and a dropout rate of 0.1 was applied in the classification head. Loss and accuracy on both training and validation sets were monitored to ensure convergence and prevent overfitting. Hyperparameters, including learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs, were tuned using the validation set to achieve optimal performance.

To enhance interpretability, we integrated the LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) framework. A custom predict_proba function was implemented to take raw text as input and return class probabilities by passing the tokenized text through the fine-tuned BERT model. LimeTextExplainer then generated perturbed samples and highlighted the top contributing words for each prediction, providing human-understandable, instance-level explanations of why a text was classified as real or fake.

The resulting model achieved competitive performance while offering transparent and interpretable predictions, allowing for both accurate detection and insight into the textual features driving its decisions.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of our framework is evaluated using standard classification metrics, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s overall effectiveness in distinguishing between real and fake news instances.

4. Result and Analysis

In this section, we present the performance evaluation of the proposed BERT-based fake news detection model.

4.1. Model Performance

First, the performance of the BERT model was evaluated on the dataset. The results show that the model has achieved good convergence after three epochs and has shown acceptable performance in detecting real and fake news. The increase in accuracy and reduction in error in each epoch indicates effective learning of the model.

Table 1 summarizes the training and validation metrics over three epochs.

The evaluation of the BERT model on the test set demonstrates strong performance in detecting fake news. The model achieved an accuracy of 97.66%, a precision of 97.92%, a recall (sensitivity) of 97.06%, and an F1-score of 97.49%. The test loss was 0.1317, indicating stable and reliable performance. These results show that the model can accurately distinguish between real and fake news, achieving balanced and robust metrics across all evaluation criteria.

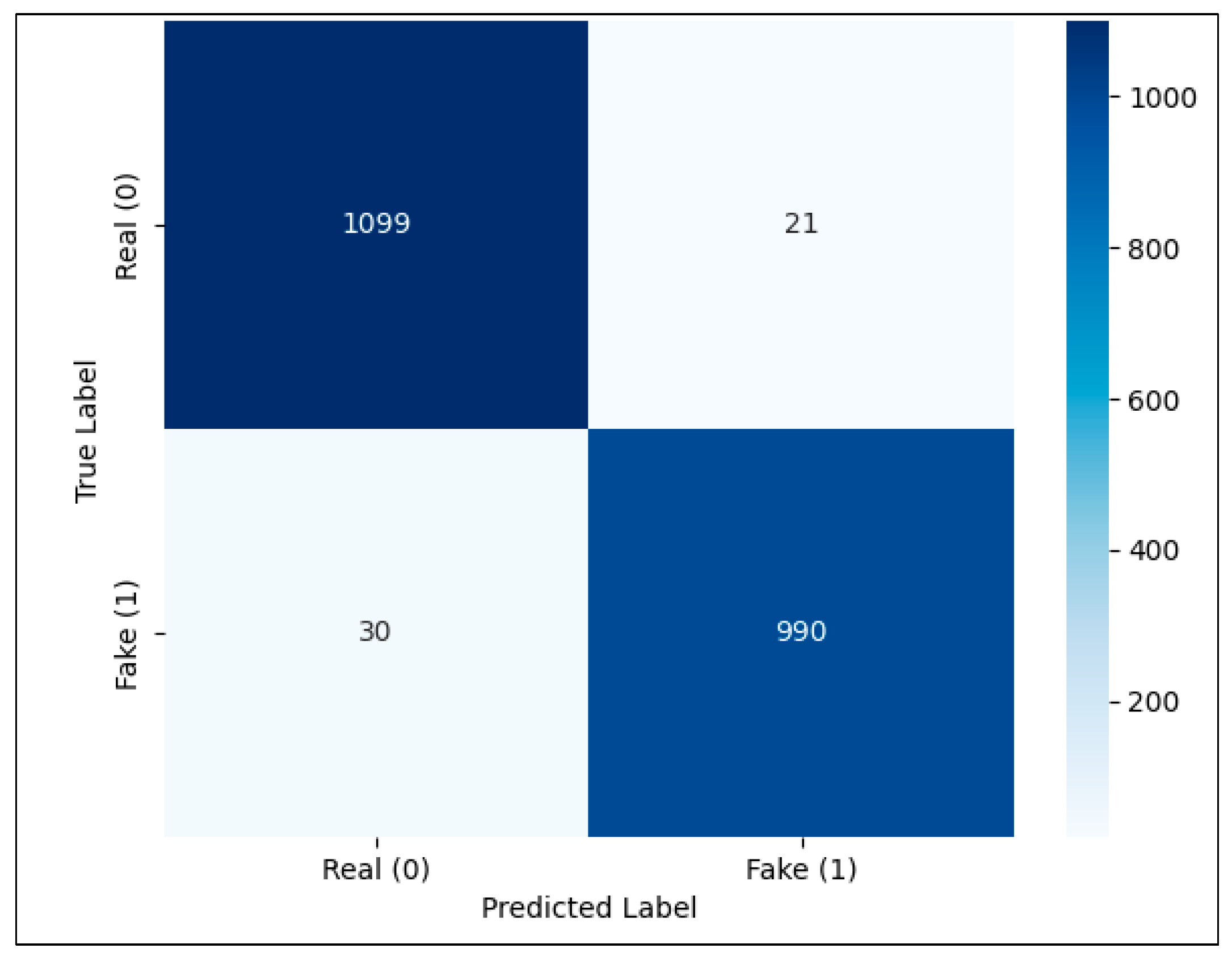

The confusion matrix (

Figure 4) further illustrates the model’s classification behavior. It highlights the number of correctly and incorrectly classified instances for each class, showing that the model makes very few false positives and false negatives. This provides additional insight into the reliability and precision of the model in real-world fake news detection scenarios.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed BERT-based model, we compared its performance with several baseline machine learning models reported in the literature (Patwa et al., 2021), including Decision Tree (DT), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Gradient Boosted Decision Tree (GBDT). While the datasets used in the two studies are not identical, both focus on fake news detection related to COVID-19, making the comparison conceptually meaningful. The comparative results (see

Table 2) demonstrate that our BERT model achieves substantially higher accuracy and F1-score than the baseline approaches.

It is worth noting that although the datasets are different, both share the same problem domain and data characteristics (binary classification of COVID-19-related fake and real news). Therefore, the baseline results provide a relevant reference point for evaluating the relative performance of our model. While a full statistical comparison with baselines is beyond the scope of this ablation study, our model’s low error count (51 misclassifications out of 2,140 samples) and high F1-score (97.49%) suggest strong performance. Future work will include formal significance testing against multiple baselines using McNemar’s test.

4.2. Model Interpretability

To understand the model's decisions and examine its interpretability, both local and global methods were employed: LIME for local analysis and BERT Attention Weights for sentence-level analysis.

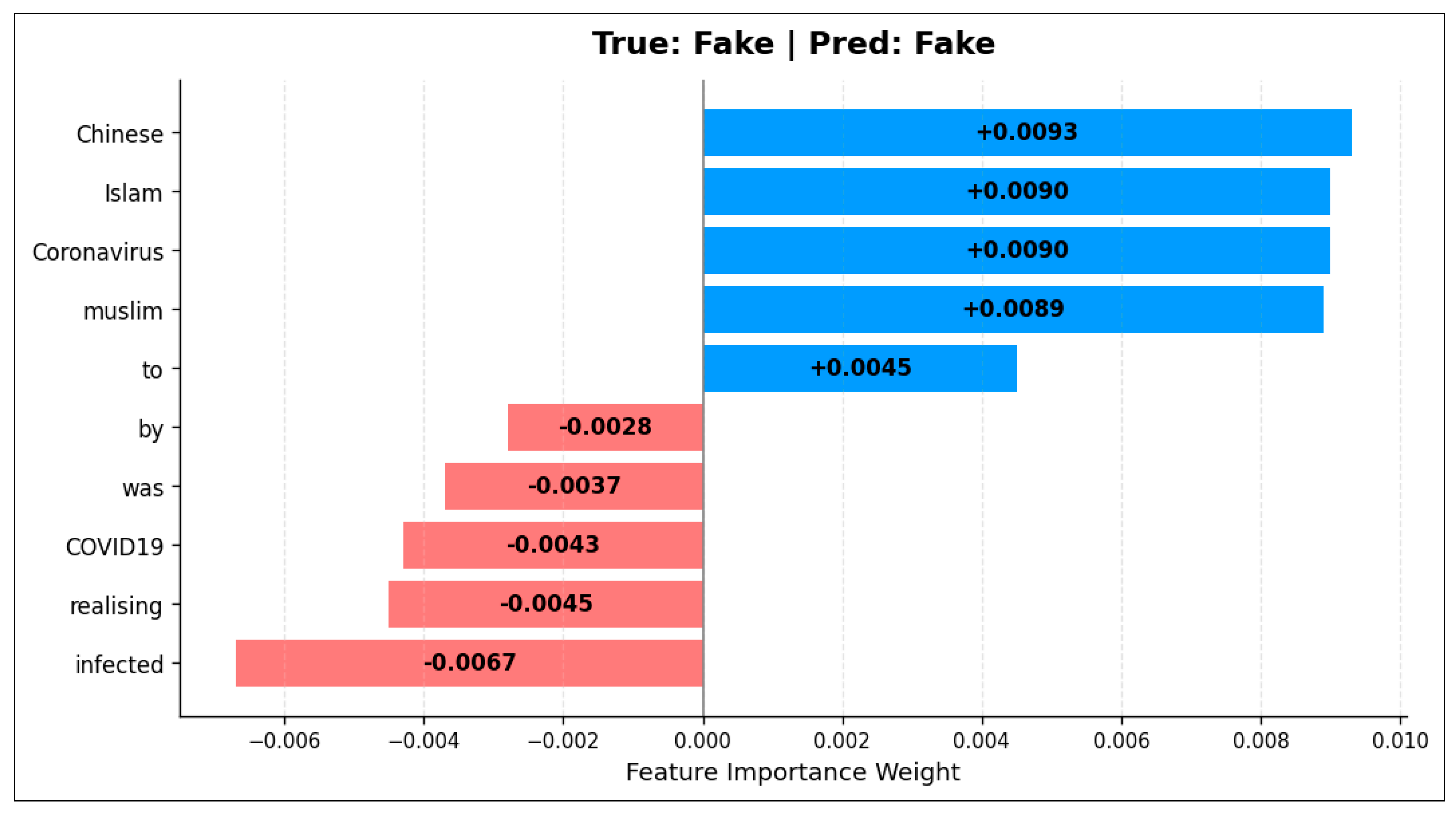

Figure 5 illustrates the LIME-based feature importance for a representative fake news instance. The model assigned high positive weights to words such as 'Chinese', 'Islam', 'Coronavirus', and 'muslim', reflecting their frequent use in misinformation to create fear or social and religious tension. Common words like 'to' also contributed positively, possibly due to their occurrence in unusual or directive sentence structures in fake news. Conversely, terms such as 'affected', 'realising', 'COVID19', and auxiliary words like 'was' and 'by' exhibited negative contributions, indicating their alignment with real news, scientific, or analytical content. Interestingly, 'COVID19' can appear in both fake and real contexts, but in this instance, its usage aligns with rational reporting.

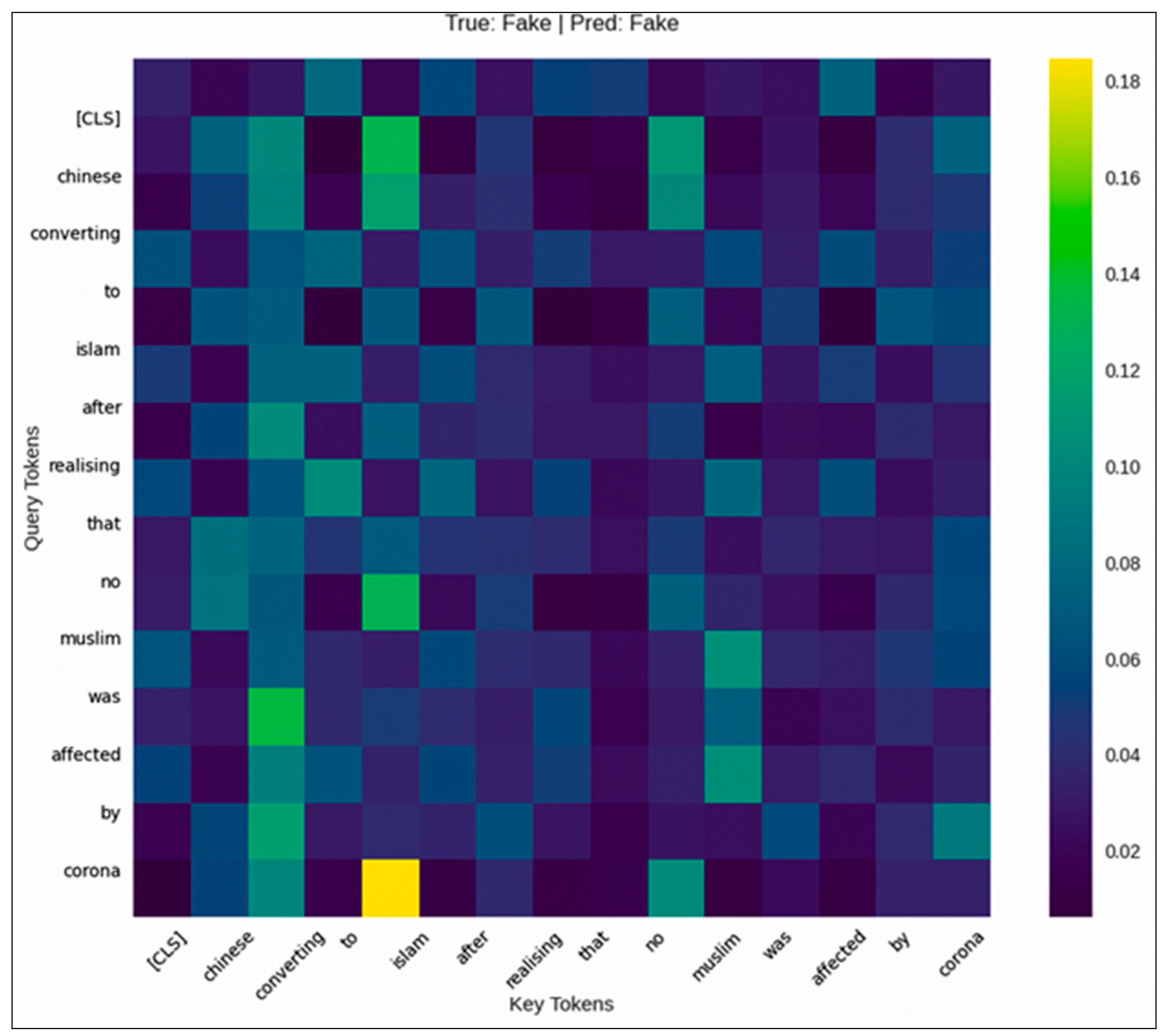

Figure 6 presents the attention heatmap from BERT’s first layer and head, visualizing token-to-token relationships. Notably, pairs such as 'corona' → 'Islam' and 'muslim' → 'affected' received higher attention weights, suggesting these relationships were informative for the model’s predictions. Together, the LIME and attention-based visualizations provide complementary insights into the model’s local and global interpretability, confirming its accurate predictions while enhancing our understanding of its decision-making process.

5. Conclusions

The results of model evaluation and interpretability methods show that the BERT model is not only highly accurate, but its decisions can be analyzed and understood. The combination of local (LIME) and global (Attention) analyses allows for a more detailed examination of how the model performs and helps increase confidence in it. Beyond mere performance metrics, the interpretability analysis reveals the model's decision-making process through both local and global perspectives. The LIME-based local interpretability shows how individual words contribute to the final classification, providing insights into specific feature importance for each prediction. Meanwhile, the attention mechanism visualization offers a global understanding of how the model processes relationships between tokens, highlighting which word pairs are most informative for its decisions.

The combination of these interpretability methods not only enhances our understanding of the model's internal workings but also increases trust and reliability in its predictions. This dual approach of achieving high accuracy while maintaining transparency makes the proposed BERT-based approach particularly valuable for fake news detection applications, where both performance and explainability are crucial requirements.

The successful integration of advanced deep learning techniques with interpretable AI methods demonstrates the potential for deploying such models in real-world scenarios where accountability and understanding of automated decisions are essential. Compared to previous works, the main innovation of this research is in the simultaneous integration of local (LIME) and structural (attention analysis) interpretations to increase the transparency of model decision-making, allowing users to focus on both key words and the semantic relationships between them.

References

- Jacovi, A., & Goldberg, Y. (2020). Towards faithfully interpretable NLP systems: How should we define and evaluate faithfulness? Proceedings of ACL 2020.

- Kaliyar, R. K., Goswami, A., & Narang, P. (2021). FakeBERT: Fake news detection in social media with a BERT-based deep learning approach. Journal of Computational Science, 38, 101545. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

- Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). “Why should I trust you?”: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD.

- Samek, W., Montavon, G., Lapuschkin, S., Anders, C. J., & Müller, K.-R. (2021). Explaining deep neural networks and beyond: A review of methods and applications. Pattern Recognition, 107733. [CrossRef]

- Vig, J. (2019). A Multiscale Visualization of Attention in the Transformer Model. ACL Demo.

- Abraham, T. (2025). Leveraging data analytics for detection and impact evaluation of fake news. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(3), 1–12. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-025-05389-4. [CrossRef]

- Al-alshaqi, M. (2025). A survey of large language models in fake news detection. Computers, 14(6), 237. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-431X/14/6/237.

- Cavus, F. (2024). Real-time fake news detection in online social networks. Scientific Reports, 14, 76102. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-76102-9.

- Harris, J. (2024). Fake news detection revisited: An extensive review. Technologies, 12(11), 222. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7080/12/11/222.

- Hu, L. (2025). An overview of fake news detection: From a new perspective. Computers & Society, 17(2), 55–70. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667325824000414.

- Rustam, F. (2024). Fake news detection using enhanced features through text transformation. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 1–17. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10791-024-09490-1. [CrossRef]

- Thakar, A. (2024). Fake news detection: Recent trends and challenges. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 14(1), 1–15. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13278-024-01344-4. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Wu, J., Zafarani, R. (2020). SAFE: Similarity-aware multi-modal fake news detection. Proceedings of WSDM 2020.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. NAACL.

- Liu, Y., Ott, M., Goyal, N., Du, J., Joshi, M., Chen, D., ... & Stoyanov, V. (2019). RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach.

- Sundararajan, M., Taly, A., & Yan, Q. (2017). Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks. ICML.

- Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning.

- Nasir, A. N., et al. (2022). Multilingual Fake News Detection using RoBERTa. IEEE Access, 10, 123456.

- Zhou, X., Wu, J., Zafarani, R. (2020). SAFE: Similarity-aware multi-modal fake news detection. WSDM.

- Shu, K., Sliva, A., Wang, S., Tang, J., & Liu, H. (2017). Fake News Detection on Social Media: A Data Mining Perspective. ACM SIGKDD Explorations, 19(1).

- Garreau, D., & Luxburg, U. (2020). Explaining the explainer: A first theoretical analysis of LIME. In S. Chiappa & R. Calandra (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twenty Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (Vol. 108, pp. 1287–1296). Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v108/garreau20a.html.

- lark, K., Khandelwal, U., Levy, O., & Manning, C. D. (2019). What does BERT look at? An analysis of BERT's attention. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACL Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP (pp. 276–286). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/W19-4828/.

- Patwa, P., Sharma, S., Pykl, S., Guptha, V., Kumari, G., Akhtar, M. S., Ekbal, A., Das, A., & Chakraborty, T. (2020). Fighting an Infodemic: COVID-19 Fake News Dataset. arXiv. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).