Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Automated Detection of Fake News

1.2. Challenges and Open Problems

- Generalization Across Sources and Topics: News data is highly heterogeneous, with content drawn from diverse sources, domains, and time periods. Models trained in one context may not transfer well to others [18].

- Interpretability: While deep models achieve high accuracy, their complex architectures often hinder transparency and interpretability, complicating the justification of automated decisions—an important issue for stakeholders, journalists, and platform administrators.

1.3. Study Motivation and Contributions

- Classical machine learning: Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM);

- Deep learning: A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU).

- A unified, mathematically principled benchmarking of traditional and neural NLP models for fake news detection across diverse input scenarios;

- Empirical insights into how input granularity (headline vs. headline+content) affects model performance and feature utilization;

- A transparent, reproducible experimental protocol with interpretable analysis of model decision criteria.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Preprocessing and Preparation

- Title-only models: Trained solely on the title field, emulating scenarios where only headline information is available or where computational efficiency is paramount.

- Title + Content models: Trained on the concatenated output of the title and content fields, leveraging both concise headline cues and the broader semantic context provided by the full article.

- Lowercasing: All text was converted to lowercase to standardize lexical representation.

- Noise removal: URLs, HTML tags, user mentions, hashtags, punctuation, and numerical digits were removed using regular expressions.

- Whitespace normalization: Multiple consecutive spaces were collapsed into a single space, and leading/trailing whitespace was trimmed.

- Stopword removal: Common English stopwords were excluded using the NLTK corpus, retaining only semantically meaningful words.

- Lemmatization: The WordNet lemmatizer was used to reduce each token to its lemma, consolidating morphological variants.

2.2. Machine Learning Models

2.2.1. Logistic Regression

- ℓ2, specifying ridge regularization.

- , where is the inverse regularization strength.

- , where liblinear implements coordinate descent, suitable for sparse, high-dimensional data, and lbfgs is a quasi-Newton method advantageous for larger datasets and faster convergence with ℓ2 regularization.

- , to optionally adjust weights inversely proportional to class frequencies.

2.2.2. Tree-Based Models

- A minimum number of samples required to further split a node,

- A maximum tree depth,

- All samples at a node belong to the same class.

2.2.2.1. Random Forest

- n_estimators: Number of trees in the forest,

- max_depth: Maximum allowable depth for each tree,

- min_samples_split: Minimum number of samples required to split an internal node,

- min_samples_leaf: Minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node,

- class_weight: Adjusts weights inversely proportional to class frequencies to mitigate class imbalance.

Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) — Mathematical Perspective

- An ℓ2 penalty on leaf weights (),

- A minimum sum of Hessians per leaf node,

- A penalty for each additional leaf.

2.3. Deep Learning Models

2.3.1. A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT)

- Factorized Embedding Parameterization: ALBERT factorizes the word embedding matrix, decoupling vocabulary size from hidden dimension, such that with and , for vocabulary size V, bottleneck size k, and hidden size d, where .

- Cross-layer Parameter Sharing: A single set of encoder weights is shared across all layers, soreducing the total number of trainable parameters and promoting regularization.

- Learning rate : log-uniformly sampled in ,

- Number of epochs: integers in ,

- Dropout rate: uniformly sampled in .

2.3.2. Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

- An embedding layer that converts token indices into dense vectors.

- One or more GRU layers to encode sequential dependencies and context.

- A fully connected output layer applied to the final hidden state for binary classification.

- Embedding dimension: integers in ,

- Hidden dimension: integers in ,

- Learning rate : log-uniformly sampled in ,

- Number of epochs: integers in .

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

2.5. Statistical Comparison of Classifiers: McNemar’s Test

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Model Comparison

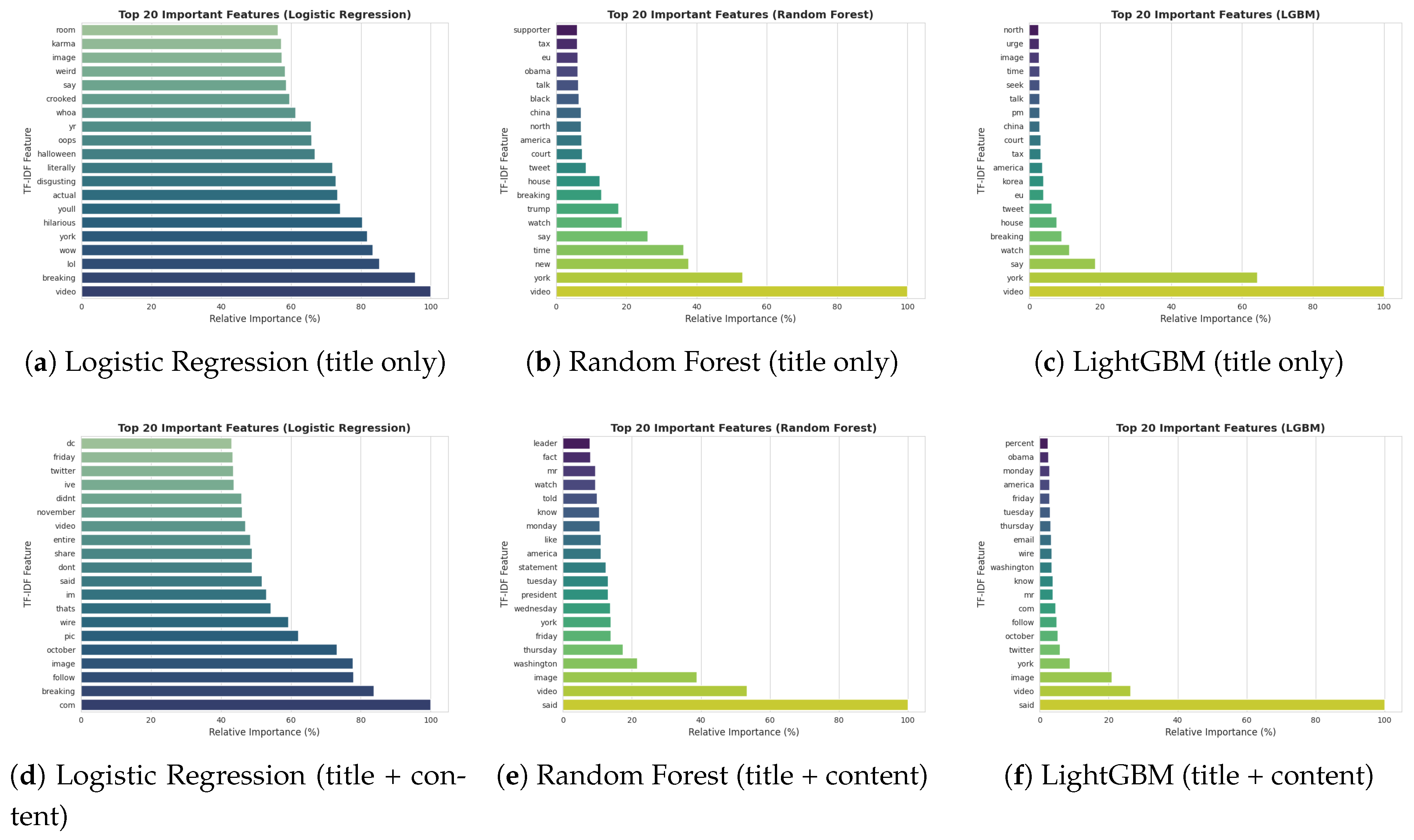

3.2. Model Interpretation: Feature Importance Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Model Performance

4.2. Statistical Significance and Model Robustness

4.3. Interpretability and Feature Analysis

4.4. Practical Implications

- For environments requiring computational efficiency and interpretability—such as media monitoring or regulatory compliance—classical ensemble models, particularly Random Forest and LightGBM, offer a robust and transparent option, especially when limited to headline data.

- In mission-critical or high-stakes settings, where detection accuracy is paramount and computational resources are sufficient, transformer-based neural architectures (such as ALBERT) are preferable, particularly when full article content is available.

- The interpretable nature of classical models can facilitate human-in-the-loop systems and explainable AI pipelines, supporting trust, regulatory transparency, and the rapid identification of emerging fake news topics or patterns.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

References

- Lazer, D.; Baum, M.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.; Greenhill, K.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The Science of Fake News. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarocostas, J. How to Fight an Infodemic. The Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluşan, O.; Özejder, İ. Faking the War: Fake Posts on Turkish Social Media During the Russia–Ukraine War. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The Spread of True and False News Online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, H.W.; S, G.; A, D.; M, R.; L, U.; HA, S.; DH, E.; L, L.; B, C. Bots and Misinformation Spread on Social Media: Implications for COVID-19. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e26933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Sliva, A.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Liu, H. Fake News Detection on Social Media: A Data Mining Perspective. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2017, 19, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, N.; Rubin, V.; Chen, Y. Automatic Deception Detection: Methods for Finding Fake News. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 2015, pp.1–4.

- Ruchansky, N.; Seo, S.; Liu, Y. CSI: A Hybrid Deep Model for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. ALBERT: A Lite BERT for Self-supervised Learning of Language Representations. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:1909.11942. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, Z.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y. Tutorial on using machine learning and deep learning models for mental illness detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04342. 2025 [arXiv:cs.LG/2502.04342].

- Gupta, A.; Kumaraguru, P. Credibility Ranking of Tweets during High Impact Events. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Privacy and Security in Online Social Media, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zafarani, R. A Survey of Fake News: Fundamental Theories, Detection Methods, and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, Article–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J.; Cao, Y. A Systematic Review of Machine Learning Approaches for Detecting Deceptive Activities on Social Media: Methods, Challenges, and Biases. 2025 [arXiv:cs.LG/2410.20293]. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.; Japkowicz, N.; Kołcz, A. Editorial: Special Issue on Learning from Imbalanced Data Sets. SIGKDD Explorations 2004, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUN, Y.; WONG, A.K.C.; KAMEL, M.S. Classification of Imbalanced Data: A Review. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence 2009, 23, 687–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J. Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, Y.Y.; Yearick, K.A. Machine Learning vs Deep Learning: The Generalization Problem. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.01621. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, P.K.; Agrawal, P.; Amorim, I.; Prodan, R. WELFake: Word Embedding Over Linguistic Features for Fake News Detection. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2021, 8, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.S. A Statistical Interpretation of Term Specificity and Its Application in Retrieval. Journal of Documentation 1972, 28, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y. Machine learning approaches for depression detection on social media: A systematic review of biases and methodological challenges. Journal of Behavioral Data Science 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, second edition ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software, Monterey, CA, 1984.

- Xu, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y. Fraud Detection in Online Transactions: Toward Hybrid Supervised–Unsupervised Learning Pipelines. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Electronic Communication and Artificial Intelligence (ICECAI 2025), 2025. 2025), 2025.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests; Vol. 45, Springer, 2001; pp. 5–32.

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2017, pp. 3149–3157.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2014, pp. 1724–1734.

- McNemar, Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 1947, 12, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Input | Model | Precision | Recall | F1-score | AUC-ROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title only | Logistic Regression | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.92 |

| Random Forest | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.93 | |

| LightGBM | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.92 | |

| ALBERT | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.98 | |

| GRU | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.96 | |

| Title + Content | Logistic Regression | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| Random Forest | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.98 | |

| LightGBM | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.99 | |

| ALBERT | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

| GRU | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Statistic | Winner | Corrected p-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title Only | |||||

| LightGBM | RandomForest | 51.60 | RandomForest | Yes | |

| LightGBM | LR | 0.96 | LR | 0.33 | No |

| LightGBM | ALBERT | 801.63 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| LightGBM | GRU | 425.25 | GRU | Yes | |

| RandomForest | LR | 24.39 | RandomForest | Yes | |

| RandomForest | ALBERT | 553.23 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| RandomForest | GRU | 260.98 | GRU | Yes | |

| LR | ALBERT | 789.32 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| LR | GRU | 394.33 | GRU | Yes | |

| ALBERT | GRU | 77.64 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| Title + Content | |||||

| LightGBM | RandomForest | 64.50 | LightGBM | Yes | |

| LightGBM | LR | 30.82 | LightGBM | Yes | |

| LightGBM | ALBERT | 371.12 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| LightGBM | GRU | 207.76 | GRU | Yes | |

| RandomForest | LR | 5.39 | LR | 0.02 | Yes |

| RandomForest | ALBERT | 592.98 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| RandomForest | GRU | 408.49 | GRU | Yes | |

| LR | ALBERT | 524.70 | ALBERT | Yes | |

| LR | GRU | 341.88 | GRU | Yes | |

| ALBERT | GRU | 41.65 | ALBERT | Yes | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).