1. Introduction

The spread of fake news poses a critical threat to information reliability, public trust, and the health of democratic societies. Across digital platforms, misleading headlines and fabricated news stories can influence public opinion, exacerbate polarization, and undermine informed decision-making [

1,

2,

3]. The rapid dissemination of misinformation, especially via short text formats such as news titles, has heightened the urgency for automated detection systems capable of robustly identifying fake news at scale.

Traditional detection methods, such as manual content moderation or rule-based keyword filters, are increasingly inadequate in the face of evolving misinformation tactics and the sheer volume of online content. Manual reviews are labor-intensive, slow to adapt to new deceptive patterns, and often yield inconsistent results. In contrast, machine learning (ML) approaches have emerged as powerful alternatives, enabling the automatic extraction of discriminative linguistic and contextual features from news data. Supervised learning methods, including logistic regression and ensemble tree-based models such as random forest (RF) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), offer strong performance on labeled data and allow for interpretable model outputs. However, their capacity to model subtle language cues is often limited, especially in short text segments like headlines.

Recent advances in deep learning have further propelled the field, with neural architectures such as transformer-based models and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) demonstrating exceptional capabilities in natural language understanding. Notably, lightweight transformer models such as A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) can effectively capture semantic relationships and sequential dependencies within short texts, offering promising results for fake news classification [

2,

3,

4]. Despite these advancements, the relative merits of classical versus neural models remain an open research question, particularly in the context of short, information-dense inputs.

In this study, we systematically compare the effectiveness of both classical machine learning and modern deep learning approaches for automated fake news detection using only news article titles. Our contributions are threefold:

Comprehensive Benchmarking: We evaluate a range of supervised models, including logistic regression, random forest, LightGBM, ALBERT, and GRU, on the WELFake dataset, employing precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC for rigorous performance assessment.

Statistical Validation: We apply pairwise McNemar’s tests with Holm correction to statistically quantify differences in model performance.

Model Interpretability: We analyze and compare the most influential features identified by each machine learning model, providing insight into the lexical cues associated with fake and real news headlines.

Unlike many prior works that pursue ever more complex models or richer feature sets (e.g., MESSER), our approach deliberately emphasizes practical efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Rather than assuming access to long-form news articles or extensive metadata, we focus exclusively on the news headline—a short, information-dense text segment that is almost always available, but offers limited context.

This strategic minimalism enables several practical advantages: (i) faster inference and lower computational cost, making deployment feasible even on resource-constrained platforms; (ii) a lower barrier to real-world adoption, as headline information is universally available and requires no additional data collection; and (iii) a rigorous test of whether sophisticated deep learning and machine learning models can extract robust, generalizable cues from highly condensed inputs.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section II formally defines the problem setting and outlines the classification objective. Section III describes the dataset, preprocessing steps, and model configurations. Section IV presents the experimental results and statistical comparisons. Section V discusses key implications and limitations of the study. Finally, Section VI concludes the paper with recommendations for future research and real-world deployment of fake news detection systems.

2. Problem Formulation

Fake news detection aims to classify a given news item as either real or fake based on its content. Formally, let denote the set of input samples, where each represents the preprocessed textual feature vector derived from a news headline. Correspondingly, let , where each , indicate the ground-truth label, with 1 representing real news and 0 representing fake news.

The objective is to learn a function , parameterized by \theta, that maps each input x_i to its predicted label . This can be achieved through supervised learning, where model parameters \theta are optimized to minimize a loss function , such as binary cross-entropy for deep models or log loss for classical classifiers.

Given the nature of the input (short, high-variance titles) and the class labels, this is a binary text classification problem characterized by: (1) Sparse, high-dimensional feature space (TF-IDF or embeddings), (2) Limited context per sample (headline-only), (3) Minimal prior structure (no metadata or article body)

The study benchmarks multiple instantiations of , including linear, tree-based, and neural network models, to assess their ability to generalize in this constrained setting.

3. Methods

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

For this study, we utilized the WELFake dataset (available on Kaggle), a comprehensive and large-scale corpus specifically developed for fake news detection. WELFake was constructed by integrating four widely recognized news datasets—the Kaggle Fake News Dataset, McIntire Dataset, Reuters Dataset, and BuzzFeed Political News Dataset—resulting in a diverse and extensive collection of 72,134 articles, each labeled as either real (1) or fake (0) [

5]. Each record in the dataset contains a title, main text, and a binary label.

To ensure data quality, entries with missing values in any essential field (title, text, or label) and all duplicates were removed. For computational efficiency, we limited our analyses to the news article titles only, rather than the full article texts, for both machine learning and deep learning models. This choice was motivated by the large dataset size and the need to streamline processing and experimentation, while still capturing the core intent and distinguishing cues present in news headlines.

Text preprocessing followed a standardized pipeline. All titles were converted to lowercase, URLs, mentions, hashtags, HTML tags, punctuation, and numeric digits were removed, and extraneous whitespace was eliminated. Common English stopwords were excluded to reduce noise, and remaining words were lemmatized using the WordNet lemmatizer to normalize different inflections of the same term. This preprocessing pipeline was uniformly applied before model development.

For machine learning models, we transformed the cleaned titles into numerical feature vectors using term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) encoding, extracting up to 1,000 features based on unigrams and bigrams. The vectorizer was fit on the training titles and applied consistently to the validation and test titles.

The dataset was split into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) subsets using stratified sampling to preserve the distribution of real and fake news in all splits. All random splits used a fixed random seed for reproducibility.

By focusing solely on article titles, we ensured a consistent and computationally efficient approach to evaluating and comparing both traditional and neural classification models.

3.2. Machine Learning Models

To benchmark the performance of classical machine learning techniques in fake news detection, we implemented three widely used supervised models: logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM). Each model was chosen to represent a different set of strengths in interpretability, handling of feature complexity, and scalability.

Logistic regression [

4] provides a transparent, interpretable baseline for binary classification tasks. In our study, it models the probability that a news title is fake by applying a logistic function to a linear combination of the TF-IDF feature vector. While unable to capture nonlinear interactions, logistic regression produces coefficients that offer insights into the importance and directionality of individual n-gram features. We trained the model using L₂ regularization (i.e., ridge regression) to prevent overfitting, and optimized the regularization strength and solver choice through grid search. The model’s class weighting parameter was also tuned to address any residual imbalance between real and fake news samples [

5]. Hyperparameter tuning for logistic regression was performed based on the weighted F1 score on the validation set.

Decision tree classifiers are foundational algorithms in machine learning, capable of modeling complex, nonlinear feature interactions by recursively partitioning the data based on input features. However, single decision trees are well known for their tendency to overfit, especially in high-dimensional or sparse feature spaces such as those arising from text data. To ensure model generalizability and robustness, we did not include standalone decision tree models in this study. Instead, we focused on advanced ensemble tree-based methods that mitigate overfitting through aggregation and regularization.

Random forest [

7,

8] is an ensemble method that aggregates predictions from multiple decision trees, each built on bootstrapped samples of the training data with randomly selected feature subsets at each split. This design enables robust modeling of nonlinear patterns and complex feature interactions present in textual data. For this project, we tuned the number of trees, tree depth, and minimum sample requirements for splits and leaves via grid search, selecting hyperparameters based on the weighted F1 score on the validation set. Feature importance measures derived from the trained model helped identify the most influential title n-grams in fake news detection.

LightGBM [

9,

10] is a scalable gradient boosting framework that grows trees in a leaf-wise manner using histogram-based feature binning, resulting in efficient learning and high performance on sparse text features. Its ability to tune class weights and handle large-scale, high-dimensional data makes it well-suited for fake news classification with TF-IDF input. We systematically optimized hyperparameters including the learning rate, number of boosting rounds, maximum tree depth, and class weighting using grid search, with hyperparameter selection based on the weighted F1 score on the validation set. The model’s built-in feature importance metrics provided additional interpretability.

All models were trained exclusively on the TF-IDF features extracted from preprocessed news titles. No additional resampling or data augmentation was applied.

3.3. Deep Learning Models

Alongside classical supervised learning models, we explored two state-of-the-art neural architectures for fake news detection using news titles: A Lite Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (ALBERT) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU).

ALBERT [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] is a streamlined version of the popular BERT transformer, introduces significant parameter reduction through cross-layer parameter sharing and factorized embeddings. This design substantially reduces memory and computation requirements, making ALBERT suitable for large-scale applications such as automated news filtering. ALBERT’s pre-training objective also includes sentence order prediction, improving its sensitivity to context and coherence in text.

For this study, we fine-tuned the pre-trained albert-base-v2 model to classify news titles as real or fake. Input titles were tokenized using the ALBERT tokenizer, with sequences truncated or padded to a maximum length compatible with the model’s requirements. Randomized hyperparameter search was employed to select learning rates between 1e-5 and 5e-5, dropout rates between 0.1 and 0.5, and epochs in the range of 3 to 5. Model selection was guided by the weighted F1 score on the validation set. Training and evaluation utilized the Hugging Face Transformers library, and final assessment was performed on the held-out test set.

GRUs [

16] are a class of recurrent neural networks specifically engineered to model sequential data with reduced computational overhead compared to LSTMs. GRUs utilize update and reset gates to capture dependencies in text sequences, allowing them to effectively learn contextual relationships in short texts such as news titles.

For the GRU model, preprocessed and tokenized titles were converted to integer sequences and padded to a fixed length. The architecture comprised an embedding layer, a GRU layer, and a fully connected output layer. Dropout was applied to mitigate overfitting. Model training used the Adam optimizer and a weighted cross-entropy loss to account for any label imbalance. Hyperparameters, including embedding size (128–256), hidden units (128–512), learning rate (1e-4–1e-3), and number of epochs (5–10), were tuned using random search. Model performance was validated by the weighted F1 score.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

While many fake news datasets suffer from class imbalance, the WELFake dataset used in this study is nearly balanced, with comparable numbers of fake and real news titles. Nevertheless, we adopted a comprehensive evaluation framework based on four standard metrics: precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Precision measures the proportion of news titles predicted as fake that are truly fake, while recall captures the proportion of all actual fake news titles correctly identified. The F1-score, defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a single, balanced indicator of model effectiveness. Weighted F1-score was used as the primary metric for hyperparameter tuning across all models, ensuring consistent optimization and fair comparison.

The AUC-ROC metric was also reported to assess the models’ ability to discriminate between fake and real news across all classification thresholds, offering insight into overall discriminative power.

By employing this suite of metrics on a balanced dataset, we ensure a nuanced and reliable assessment of each model’s performance, both in terms of overall accuracy and class-specific predictive ability.

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of both machine learning and deep learning models on the WELFake news title classification task.

Table 1 summarizes the macro-averaged precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC for each model, with the highest values observed for the transformer-based ALBERT architecture.

Among the machine learning models, random forest slightly outperformed both logistic regression and LightGBM across all metrics, with macro-averaged F1-scores of 0.85 compared to 0.84 and 0.83, respectively. All three models achieved strong AUC values above 0.92, indicating reliable discrimination between fake and real news titles.

Deep learning models, however, demonstrated even greater effectiveness. ALBERT achieved the highest macro-averaged precision (0.92), recall (0.93), and F1-score (0.93), along with an AUC of 0.98. This indicates robust and balanced detection of both fake and real news titles, with minimal trade-off between precision and recall. The GRU model, while showing a slightly lower macro precision and recall (0.80 each), attained a high F1-score (0.90) and AUC (0.96), suggesting effective sequential modeling of the short textual inputs.

These results highlight the advantage of transformer-based neural architectures in capturing subtle cues and linguistic patterns present in news headlines, leading to superior classification performance compared to traditional machine learning baselines.

4.2. Pairwise Model Comparison

To assess whether the observed performance differences between models were statistically significant, we conducted pairwise McNemar’s tests with Holm correction for multiple comparisons. The results (see

Table 2) show that ALBERT significantly outperformed all other models, including GRU, random forest, and logistic regression. GRU also demonstrated statistically significant superiority over random forest, LightGBM, and logistic regression.

Overall, these statistical comparisons reinforce the superiority of neural architectures, especially ALBERT, in the fake news title classification task.

4.3. Model Interpretation and Feature Importance

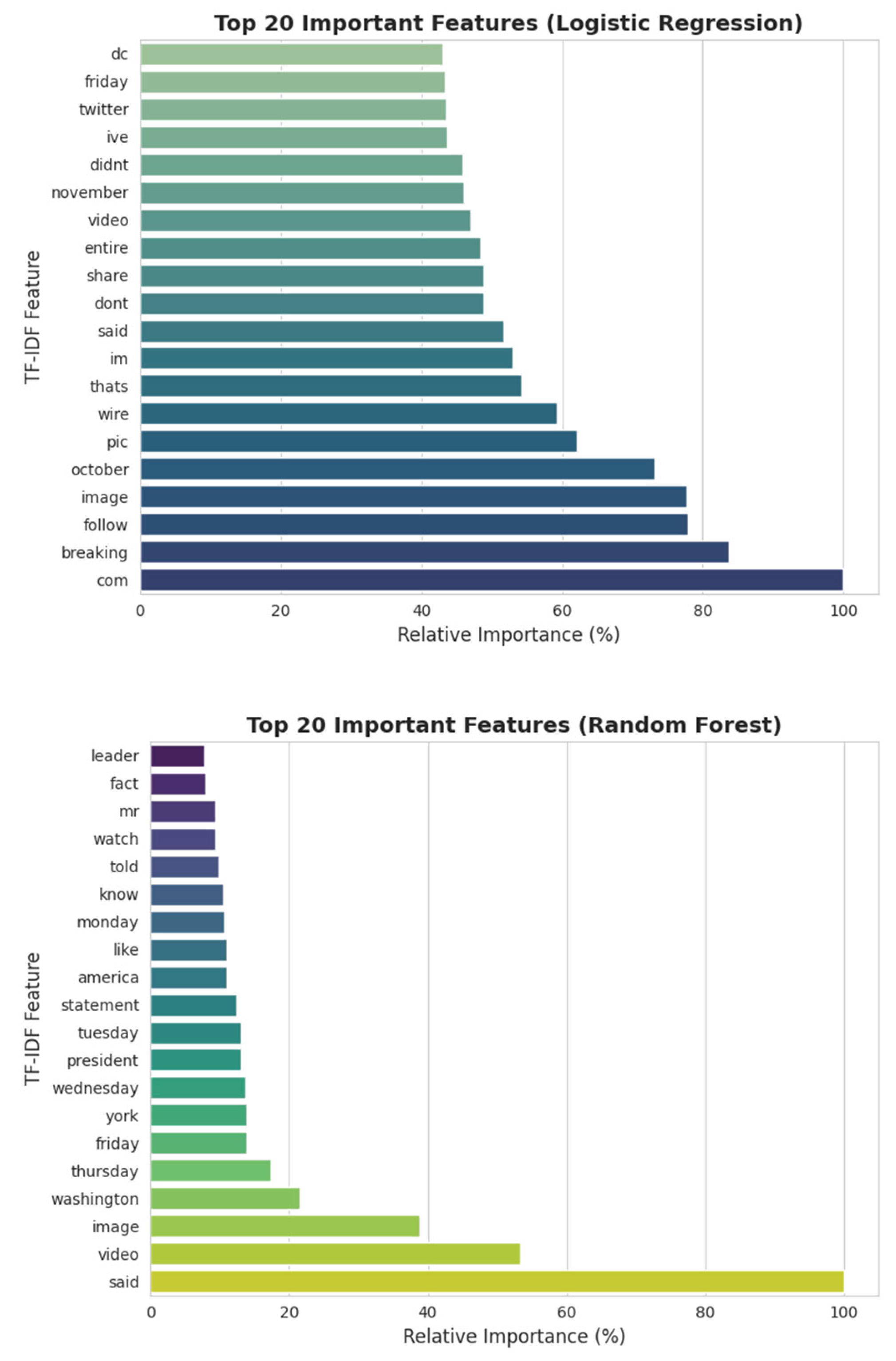

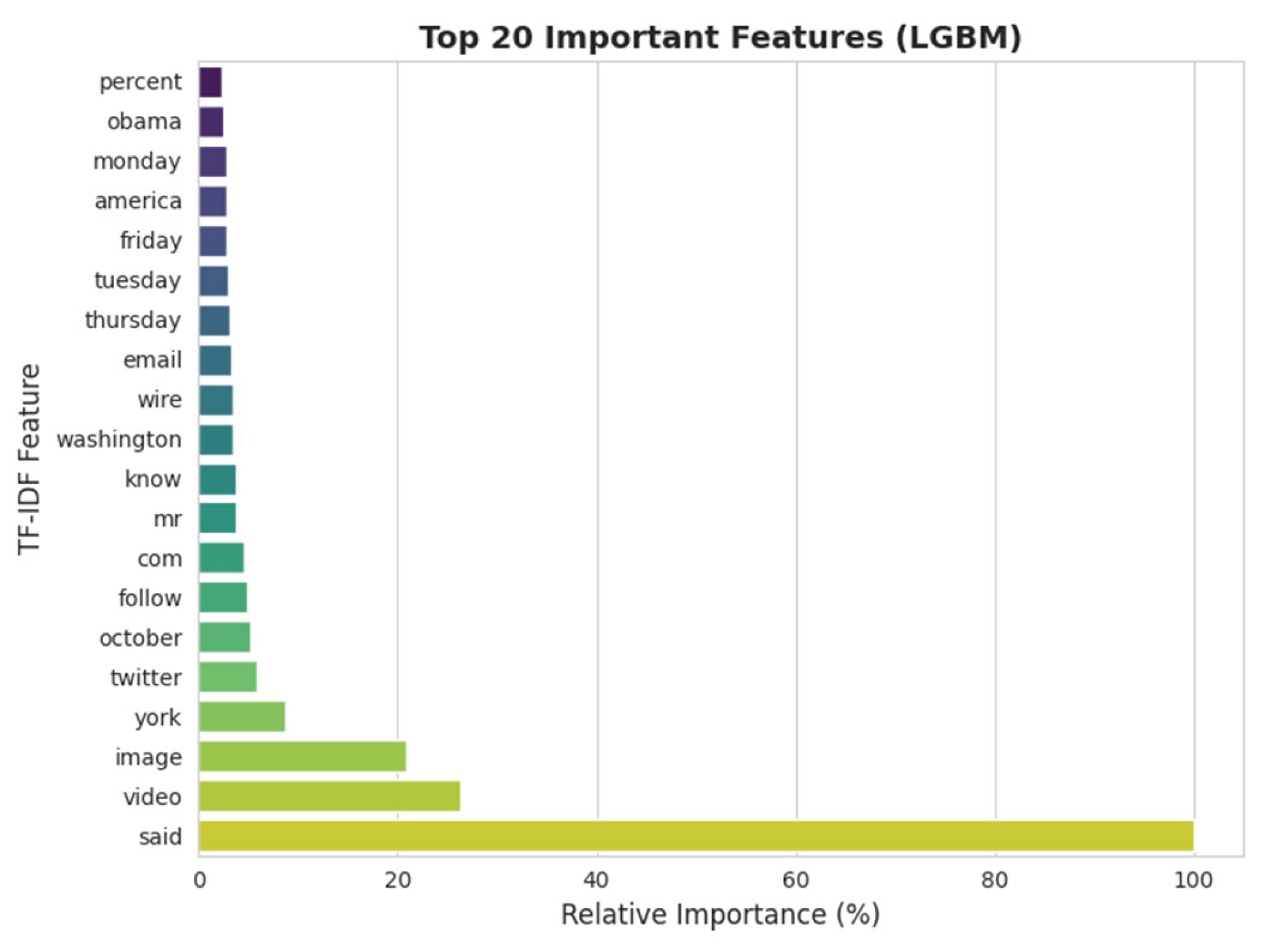

To better understand the decision-making processes of the machine learning models, we analyzed the most influential title features as determined by each model’s internal importance metrics (see

Figure 1). Feature importance was measured via model coefficients for logistic regression and mean decrease in impurity or gain for ensemble models.

Across all models, the word “video” consistently emerged as the top predictor for distinguishing between fake and real news titles. This suggests that references to “video” in headlines are highly indicative of the underlying class, potentially reflecting the prevalence of sensational or multimedia-oriented fake news in the dataset. Other consistently important features for random forest and LightGBM included “york” and “new”—likely pointing to frequent mentions of “new york” in the corpus, which may have a strong association with either real or fake news.

While there was notable overlap in key features identified by the ensemble models (random forest and LightGBM), with terms like “breaking,” “watch,” “say,” “house,” “tweet,” and “america” ranked highly, logistic regression prioritized a somewhat different set of features. Besides “video” and “breaking,” logistic regression highlighted expressive or colloquial words such as “lol,” “wow,” “hilarious,” “literally,” “oops,” and “weird,” indicating a sensitivity to emotionally charged or viral language that frequently appears in misleading headlines.

Furthermore, logistic regression surfaced features suggestive of informal online discourse, such as “whoa,” “yr,” “karma,” “room,” and “crooked,” suggesting it may capture stylistic cues or slang that help differentiate fake news from real news in short text settings.

In summary, while all machine learning models relied on certain high-frequency or topical cues, ensemble approaches like random forest and LightGBM emphasized event-driven and location-based keywords, whereas logistic regression also surfaced emotionally charged and informal language as key indicators. This diversity in feature utilization reflects differences in model architecture and offers valuable interpretive insight into how news headlines are parsed and classified by automated systems.

5. Discussions

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

This study systematically benchmarks classical and deep learning models for fake news detection using only news article titles as input. Our results demonstrate that while traditional models—Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and LightGBM—provide strong baseline accuracy, advanced neural models, particularly the transformer-based ALBERT, achieve the highest performance across all metrics. ALBERT’s superior F1-score and AUC confirm its advantage in extracting nuanced contextual signals even from highly condensed inputs.

Within classical models, Random Forest consistently outperformed both Logistic Regression and LightGBM, benefiting from its ability to capture nonlinear feature interactions. Logistic Regression, although transparent, was more influenced by colloquial or emotionally charged terms. Ensemble models emphasized event-driven and location-based words, highlighting their interpretive value in headline analysis.

Importantly, the study’s core innovation lies in showing that robust fake news detection is possible with a minimal feature set. By focusing exclusively on headlines, we demonstrate that high accuracy (F1 > 0.90 for ALBERT) can be achieved without full-text input or complex feature engineering. This distinguishes our work from previous studies and addresses practical deployment needs where data or computation is limited.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings support several key recommendations for real-world applications:

Model selection: For rapid, low-resource scenarios, classical models—especially Random Forest—offer an effective, interpretable baseline. However, transformer-based models like ALBERT should be preferred in high-throughput or mission-critical settings where the highest accuracy is required.

Feature engineering: Consistently high importance of terms like “video,” city names, and emotive language indicates that both content and style are crucial for fake news identification, even with short text.

Efficiency: The demonstrated strength of headline-only models lowers the barrier for deployment on platforms where only limited or partial data is available.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations warrant further research:

Title-only focus: Restricting input to headlines omits richer semantic context found in full articles. Future studies should quantify the incremental benefits of including article bodies or additional metadata.

Dataset generalizability: Results are specific to the WELFake dataset; extending analysis to other datasets, languages, or domains would test the robustness of these findings.

Interpretability of deep models: While feature importance is accessible for classical models, neural models remain a “black box.” Incorporating model-agnostic interpretation techniques would enhance transparency.

Dynamic misinformation: All models were trained and tested statically; future work should explore online learning, domain adaptation, and real-time feedback mechanisms to handle evolving misinformation patterns.

Emerging models: Large language models and multimodal fusion represent promising avenues for capturing more sophisticated or cross-platform fake news strategies.

In summary, our work demonstrates that cost-effective, headline-based detection pipelines can achieve state-of-the-art performance and provides a practical blueprint for scalable fake news detection in settings where computational efficiency is paramount.

References

- T. Abdullah All, E. M. Mahir, S. Akhter, and M. R. Huq, “Detecting Fake News using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms,” in 2019 7th International Conference on Smart Computing & Communications (ICSCC), pp. 1–6, June 28–30, 2019.

- J. Alghamdi, Y. Lin, and S. Luo, “Towards COVID-19 fake news detection using transformer-based models,” Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 274, p. 110642, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Shah and S. Patel, “A comprehensive survey on fake news detection using machine learning,” Journal of Computer Science, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 982-990, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nida, I. U. Khan, F. S. Alotaibi, L. A. Aldaej, and A. K. Aldubaikil, “Fake Detect: A deep learning ensemble model for fake news detection,” Journal of Computer Science, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 555-584, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Verma, P. Agrawal, I. Amorim, and R. Prodan, “WELFake: Word Embedding Over Linguistic Features for Fake News Detection,” IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 881–893, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. W. Hosmer and S. Lemeshow, Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed., New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000.

- Y. Zhang, Z. Wang, Z. Ding, Y. Tian, J. Dai, X. Shen, Y. Liu, and Y. Cao, “Tutorial on using machine learning and deep learning models for mental illness detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04342, 2025.

- L. Breiman, “Random forests,” Machine Learning, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 5–32, 2001.

- J. H. Friedman, “Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine,” Annals of Statistics, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 1189–1232, 2001.

- G. Ke, Q. Meng, T. Finley, T. Wang, W. Chen, W. Ma, Q. Ye, and T.-Y. Liu, “LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree,” in Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), pp. 3149–3157, 2017.

- Z. Lan, M. Chen, S. Goodman, K. Gimpel, P. Sharma, and R. Soricut, “ALBERT: A lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.11942, 2020.

- Z. Wang, J. Cheng, C. Cui, and C. Yu, “Implementing BERT and fine-tuned RoBERTa to detect AI generated news by ChatGPT,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.07401, 2023.

- S. Xu, Y. Tian, Y. Cao, Z. Wang, and Z. Wei, “Enhancing fake news detection with transformer models and summarization,” Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 23253-23259, 2025.

- A. Rahman, S. S. Kumar, and M. S. R. Anwar, “Transformer-based approach for detection and classification of fake news in low-resource languages,” Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Natural Language Processing, pp. 112-120, 2024. (Please insert DOI if available.).

- S. Kumar and R. Singh, “A novel approach for early rumour detection in social media using ALBERT,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 259-265, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Cho, B. van Merrienboer, C. Gulcehre, D. Bahdanau, F. Bougares, H. Schwenk, and Y. Bengio, “Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation,” in Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pp. 1724–1734, 2014.

- D. M. W. Powers, “Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation,” Journal of Machine Learning Technologies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 37–63, 2011.

- J. Davis and M. Goadrich, “The relationship between precision-recall and ROC curves,” in Proc. 23rd Int. Conf. on Machine Learning (ICML), pp. 233–240, 2006.

- Z. Ding, Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, Y. Cao, Y. Liu, X. Shen, Y. Tian, and J. Dai, “Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media,” Scientific Reports, vol. 15, article no. 14497, 2025.

- Y. Cao, J. Dai, Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, X. Shen, Y. Liu, and Y. Tian, “Machine learning approaches for depression detection on social media: A systematic review of biases and methodological challenges,” Journal of Behavioral Data Science, vol. 5, no. 1, Feb. 2025.

- Y. Huang, L. Zhang, and J. Xu, “Adversarial group linear bandits and its application to collaborative edge inference,” in IEEE INFOCOM 2023 – IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, May 17, 2023, pp. 1–10.

- Y. Wang, Y. Guo, Z. Wei, Y. Huang, and X. Liu, “Traffic flow prediction based on deep neural networks,” in 2019 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Nov. 8, 2019, pp. 210–215.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).