1. Introduction

The dystrophin gene is the largest in the human genome, comprising 79 exons and encoding the 427 kDa dystrophin protein. Functionally, dystrophin is an essential cytoskeletal protein located on the inner surface of the muscle cell membrane and is concentrated at sites of cell-cell contact [

1]. In muscle, dystrophin is an essential part of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC), and the associated glycoprotein complex includes dystroglycan, sarcoglycan, sarcospan, and laminin [

2]. Dystroglycan consists of two subunits, α and β. α-Dystroglycan, an extracellular peripheral membrane protein and laminin-2 receptor, anchors the DGC to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Sarcoglycans form a tight complex with sarcospan, strengthening the connection between α- and β-dystroglycans. Besides its structural role, the sarcoglycan-sarcospan subcomplex also plays a part in signal transduction and mechanoprotection [

3]. This entire complex is essential for muscle physiology and function. However, the absence of dystrophin causes the complete loss of the dystrophin-associated protein complex and leads to membrane fragility disorders [

4]. Dystrophin-associated disorders are identified as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). Exon deletions make up 60-70% of cases observed in DMD, while frameshift mutations and duplications account for 30-40% [

5]. The most common hotspot for exon deletions in DMD is located in the core of dystrophin, between exons 45 and 55 [

6]. In particular, the central region is nearly indispensable in function and serves as the source of the genetic pathology for DMD.

In DMD, these mutations result in premature termination of protein translation, leading to the production of dysfunctional, unstable dystrophin [

7]. Dysfunctional dystrophin leads to muscle weakness. Early signs include trouble climbing stairs, difficulty walking without support, and frequent falls; these usually appear between ages 2 and 3. Most patients become wheelchair-dependent between ages 10 and 12 and need respiratory support by around age 20. With proper care, many with DMD die from heart or lung failure between the ages of 20 and 40 [

5,

8]. Dystrophin is mainly expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle. However, it has also been found in the brain, liver, intestine, kidney, and retina. Its presence in the brain is less extensive than in the muscles, which helps explain some of the central nervous system symptoms of the disease [

9]. For example, there is a decline in learning ability, impaired muscle coordination, and degeneration of both afferent and efferent nerves. Epilepsy occurs more frequently than in the general population, and autism-like behaviors have been occasionally observed [

10]. It is known that ALT and AST enzymes, in particular, are characteristically elevated in the liver [

11]. Problems like constipation caused by muscle weakness have been reported in the gastrointestinal system [

12]. Studies have indicated that cysteine levels in the kidneys are increased in DMD [

13]. These studies have demonstrated that renal involvement is linked to chronic cardiac dysfunction, low water intake, and diuretic use [

14]. Long-term follow-up studies have shown that, although myofibrillar atrophy, necrosis, and fatty degeneration are observed in DMD patients, endomysial fibrosis remains the standard myopathological parameter, depending on the severity of the pathology [

15].

Various studies have determined that the healing ability of muscle tissue is limited compared to other tissues. Fibrosis formation and ongoing myofibrillar destruction cannot be fully offset by satellite cell proliferation. The inflammatory process that follows muscle necrosis leads to the formation of fibrotic tissue and the replacement of fatty tissue [

16]. In our study, we investigated, for the first time, the effect of whole dystrophin transferred to muscle cells using cells from DMD patients and transgenic experimental animals.

4. Discussion

The in vitro study showed that the majority of 5 different sequences + carrier combinations are effective, but we chose the highest dystrophin expression rates. In this relation, promoter, 5’ and 3’ sequences, and polyA were applied for the EXON 51, 48, and 47 dystrophins. Four exons — 52, 51, 48, and 47 — were selected for animal experiments because they represent four of the most common deletions among DMD mutations.

At this stage, the animal experiment planning was conducted as follows. The experiment lasted 45 days and included two-stage transfers. The first transfer was planned to restore all muscles, and the second to cover newly formed muscles. Sixty mdx/d2 mice were sourced from the Jackson Laboratory. The mdx/d2 strain was chosen for our studies because it closely resembles the model of human muscle damage. The comparison confirmed that dystrophin was produced. This data demonstrates the complex’s ability to cross the cell membrane and synthesize the dystrophin protein. Nonetheless, functional dystrophy must be validated through behavioral tests.

Behavioral tests

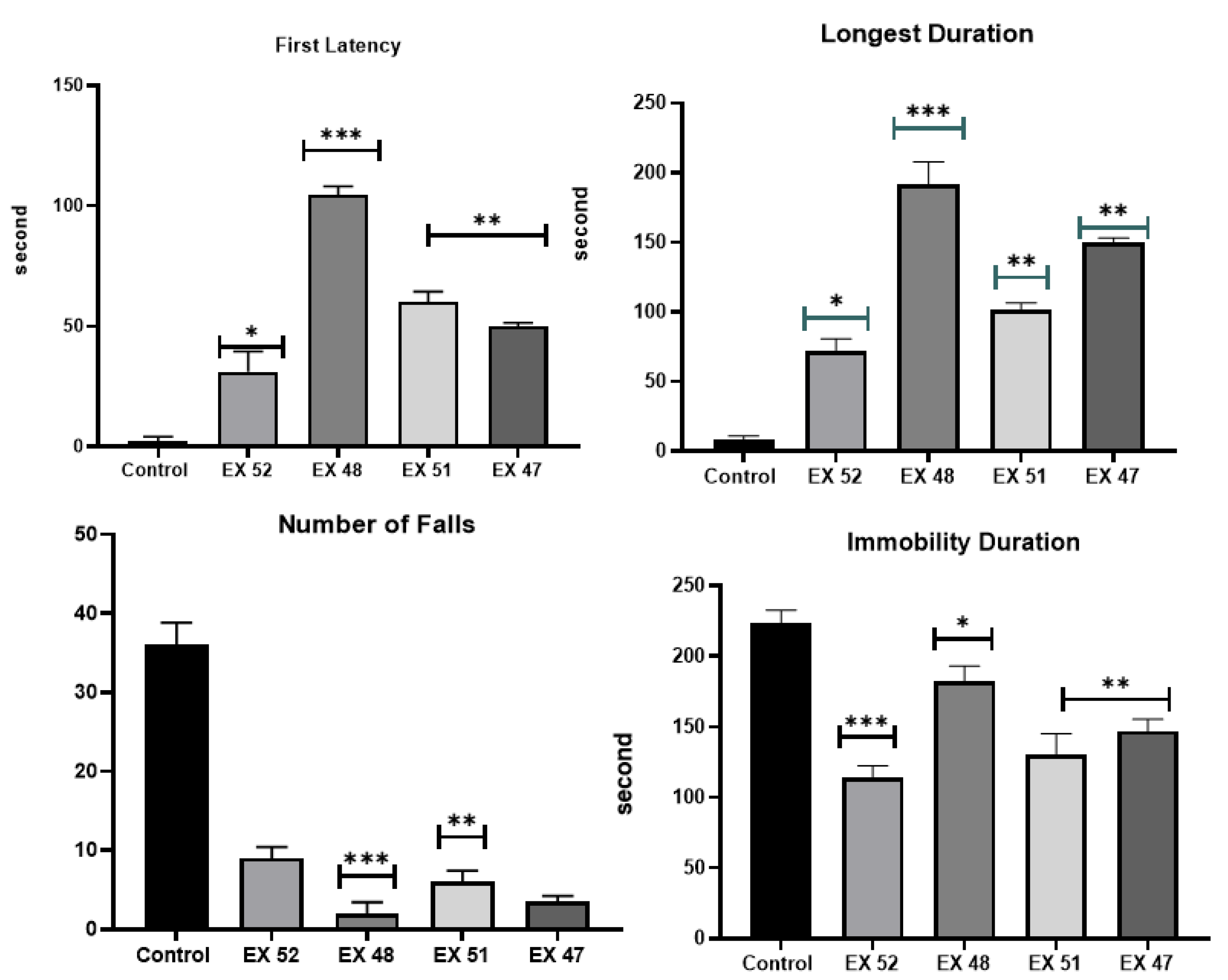

Motor function test

Motor function tests are routinely used to assess movement ability. An increase in movement ability or a decrease in rest periods indicates that motor cortex and muscle coordination have been achieved [

17]. The applied treatment has been found to increase the ability to move and stay on the rotarod during the experiment [

18]. Studies have shown improvements in wire-holding time and rotarod walking time in treated mice that produce dystrophin compared to controls. Due to decreased muscle strength (along with increased fatigue), mdx/d2 mice frequently fall from the rotating plate. The DMD control group dropped an average of 34 times in 200 seconds, while the EX48 group dropped an average of 8 times, and the other treatments dropped an average of 1 time. Visible improvement indicates increased muscle strength and that the dystrophin produced is functional.

The motor test is similar to the rotarod test. Studies have shown that the experimental mice traveled a shorter distance than the control group. However, the treated mice were found to move more vigorously and walk longer distances [

19]. When examining the distance covered and rest periods, increased mobility was observed in the treatment groups compared to the control group.

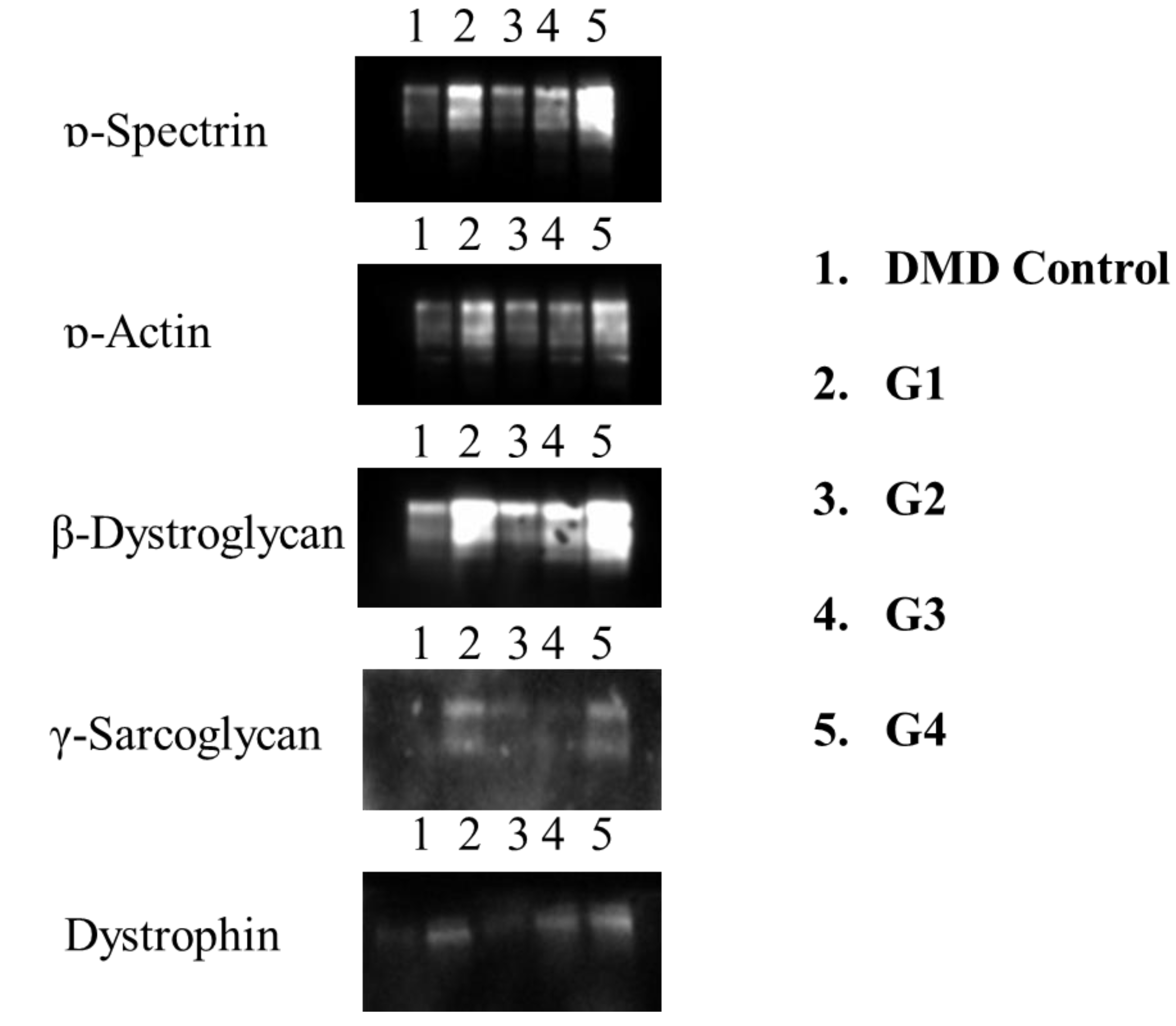

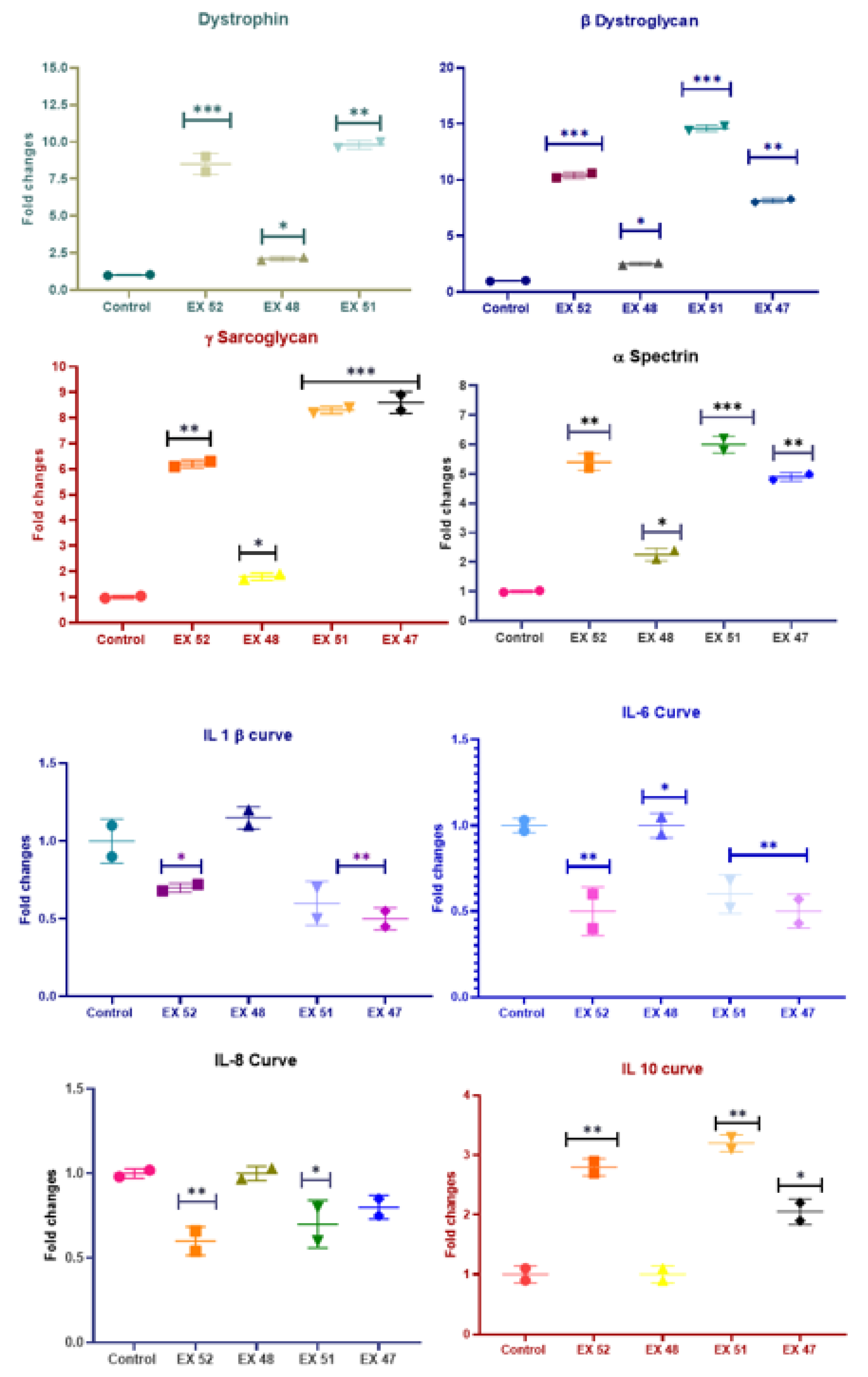

Determining Gene Expression Levels

At this stage of our study, dystrophin, β-dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, α-actin, and α-spectrin were detected at both the cellular and tissue levels. Studies generally monitor the level of dystrophin produced. However, our study supports the following notion: dystrophin forms the internal link with ɒ-actin, while β-dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, and ɒ-spectrin connect to the extracellular matrix. Therefore, investigating this complex in its entirety is essential to assessing the study’s success. CRISPR-Cas9, one of the leading methods currently used to treat DMD, increases dystrophin levels. However, it is emphasized that fibrosis negatively affects muscle development. Therefore, they suggest a gradual improvement in the treatment processes described. The first signs of improvement were reported after 1 year of treatment [

20]. Although our study was short-term, the results obtained within 45 days have significant therapeutic effects. Studies have reported increases in dystrophin production after treatment ranging from 6.255 to 11% [

21]. The exact amount of dystrophin sufficient for DMD patients is unknown. This is due to individual differences. The dystrophin ratio obtained in our study was much higher. The DMD control group was rated at 1. The highest results were found in the EX51 group, with dystrophin expression nearly 10-fold higher. These results are also supported by Western blot and IHC data.

Eteplirsen, also known as Exondys 51 (Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc.), was the first drug approved by the FDA for DMD. In DMD patients with mutations amenable to exon 51 skipping, this treatment increased dystrophin expression by 0.28% and 0.93% after 48 and 180 weeks of treatment, respectively [

22]. A significant difference was demonstrated in the 6-minute walk test 36 months after initial treatment, and six patients, with a mean age of 9 years, had lost mobility. A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, dose-finding, and comparison study is ongoing to assess the safety and efficacy of high-dose eteplirsen. Preliminary results from the phase 2 MOMENTUM study demonstrated that monthly dosing of SRP-5051, with exon 51 skipping, at 30 mg/kg resulted in an average increase in dystrophin expression of 6.55% in patients with DMD [

20].

In the study by Paola et al., ROS-activated tyrosine kinase in DMD promotes the degradation of β-dystroglycan (β-DG), a component of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex that can amplify damaging signals [

23]. In mdx/d2 mice, a 4-week subcutaneous treatment with dasatinib (DAS), a pan-Src-TKs inhibitor approved as an anti-leukemic agent, increased muscle β-DG and resulted in minimal improvements in morphofunctional indices. The study is valuable because it conducted a single β-dystroglycan trial in a DMD model. In our research, TAC, MTT, TOS, IL-1-6-8-10, and β-dystroglycan ratio were evaluated. TAC, TOS, and MTT analyses, which correspond to ROS parameters, showed that muscle inflammation and oxidative stress decreased after our treatment. Survival rates were higher in the treatment groups than in the DMD control group. Additionally, the expression level of the β-Dystroglycan gene increased nearly 15-fold in the EX51 group, suggesting that β-, γ-, and δ-sarcoglycan function as a single unit. Notably, myofiber degeneration can occur independently of dystrophin in γ-sarcoglycan-deficient mice, even though they have normal dystrophin levels and localization. Furthermore, apoptotic myonuclei are highly expressed in γ-sarcoglycan-deficient skeletal muscles, suggesting that programmed cell death contributes to myofiber degeneration [

24]. Based on this information, γ-sarcoglycan gene expression is essential regardless of DMD. Our study showed that γ-sarcoglycan expression increased nearly ninefold in the EX51 group compared to the DMD control group.

Limited studies in the literature suggest that defects in actin and spectrin binding sites may occur in dystrophin-deficient muscle [

25]. It is known that this error is caused by the degradation of accumulated proteins by proteinases. However, it is normal for the levels of these proteins to increase as reinforcement occurs after the bridges are formed and dystrophin is restored. An eightfold increase in ɒ-actin expression and a nearly sixfold increase in ɒ-spectrin expression were detected in the EX51 and EX52 groups.

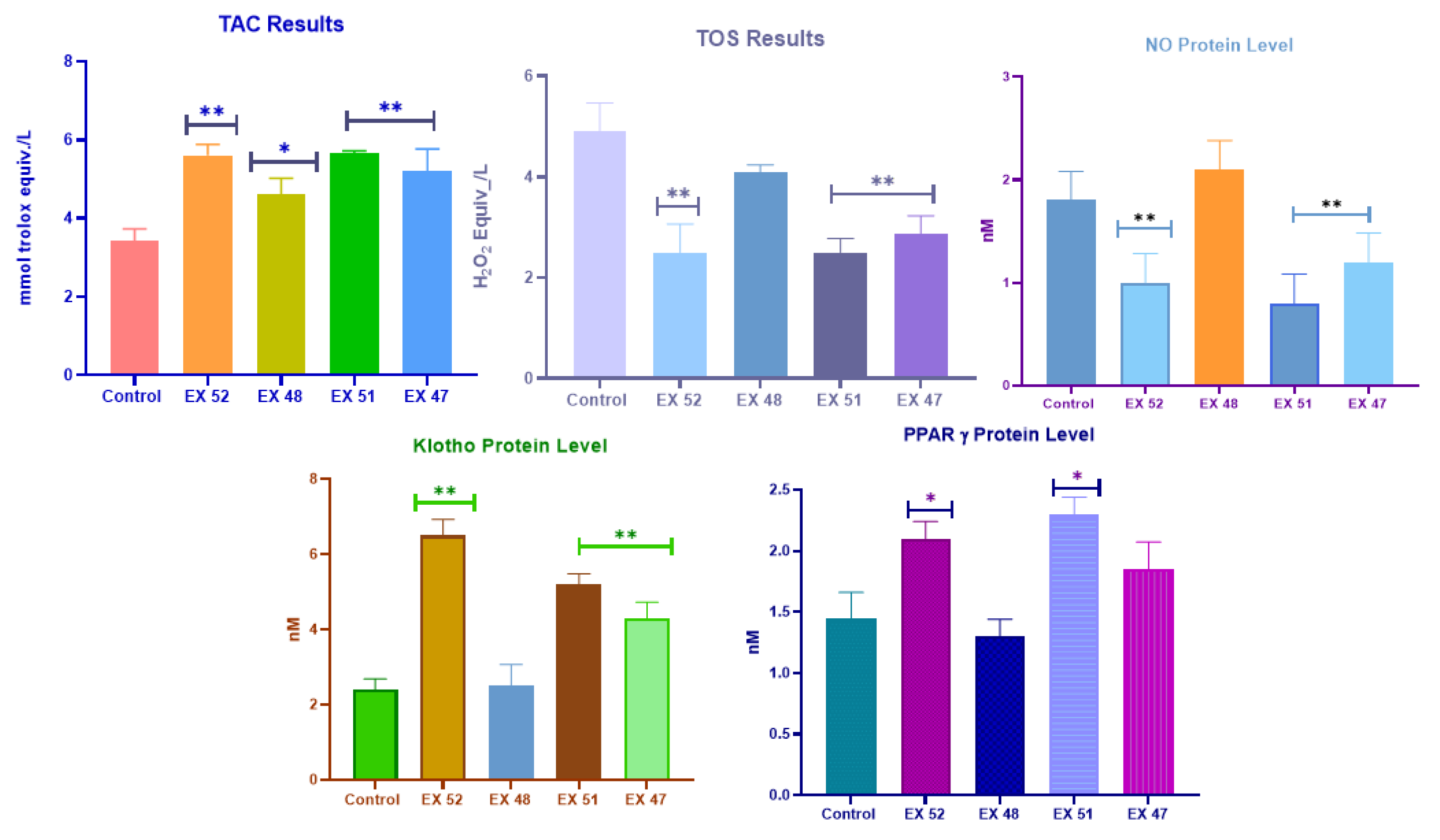

One study investigated epigenetic silencing of the klotho gene in the mdx mouse model of DMD to determine whether klotho silencing is a key feature of the disease. The data indicated that klotho undergoes muscle-specific silencing during the acute onset of mdx/d2 pathology. Expression of a klotho transgene in mdx/d2 mice has been shown to restore longevity, reduce muscle wasting, improve cellular function, and significantly increase the muscle-resident stem cell pool required for regeneration. Transgene expression was paralleled by decreased fibrosis and reduced expression of collagen types 1 and 3 in the late, progressive stages of mdx/d2 pathology. Therefore, epigenetic silencing of klotho during muscular dystrophy has been suggested to significantly contribute to the loss of regenerative capacity and increased fibrosis of dystrophic muscle in the later stages of DMD [

26]. In our study, ɒ-Klotho levels were increased in all groups except EX48 (P>0.05). Data obtained from groups EX52, EX51, and EX47 showed significant differences compared to the DMD control group (P<0.01). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a transcriptional coactivator that binds to various transcription factors. PPARγ coactivator 1 (PGC-1) has a wide range of biological effects in different tissues. It plays a key role in regulating oxidative metabolism, thereby regulating reactive oxygen species production, autophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis. Because of these findings, numerous studies aimed at determining the role of PGC-1 in the neuromuscular system have suggested that PGC-1 may be a promising target for treatments targeting neuromuscular diseases [

27]. The restoration of dystrophin and beta-dystroglycan, along with increased expression of PPARγ, a key component of cell metabolism, indicates improved function. In our study, PPARγ levels were increased in all groups except EX48 (P>0.05). Data from the EX52 and EX51 groups showed a significant difference from the DMD control group (P<0.05). The same pattern was also observed in the NO level test. Increased NO levels due to oxidative stress led to a positive treatment response, and our study data showed a decrease in its expression.

ELISA analyses of dystrophin, β-dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, ɒ-actin, and ɒ-spectrin protein levels were found to be consistent with RT-PCR results. While expression in all treatment groups was clearly higher than in the DMD control group, EX52, EX51, and EX47 showed the highest protein levels. Dystrophin, in particular, showed high expression. The increase observed in cell membrane compartments is proportional to dystrophin.

Histopathological Findings

Different organs were evaluated at this stage. Dystrophin is expressed in muscle, brain, monocytes, fibroblasts, and, to a lesser extent, in other organs. However, a deficiency in dystrophin levels affects the entire system. In DMD, the developmental stages, skeletal muscles, brain, immune system, heart, and lungs are primarily affected. In patients with DMD, muscle biopsy characteristically reveals necrotic or degenerative muscle fibers, often observed in clusters. Macrophages and CD4+ lymphocytes surround these necrotic fibers. Additionally, small, immature fibers with central nuclei are observed, reflecting muscle regeneration from myoblasts, resulting in a balance between necrotic and regenerative processes in the early stages of the disease [

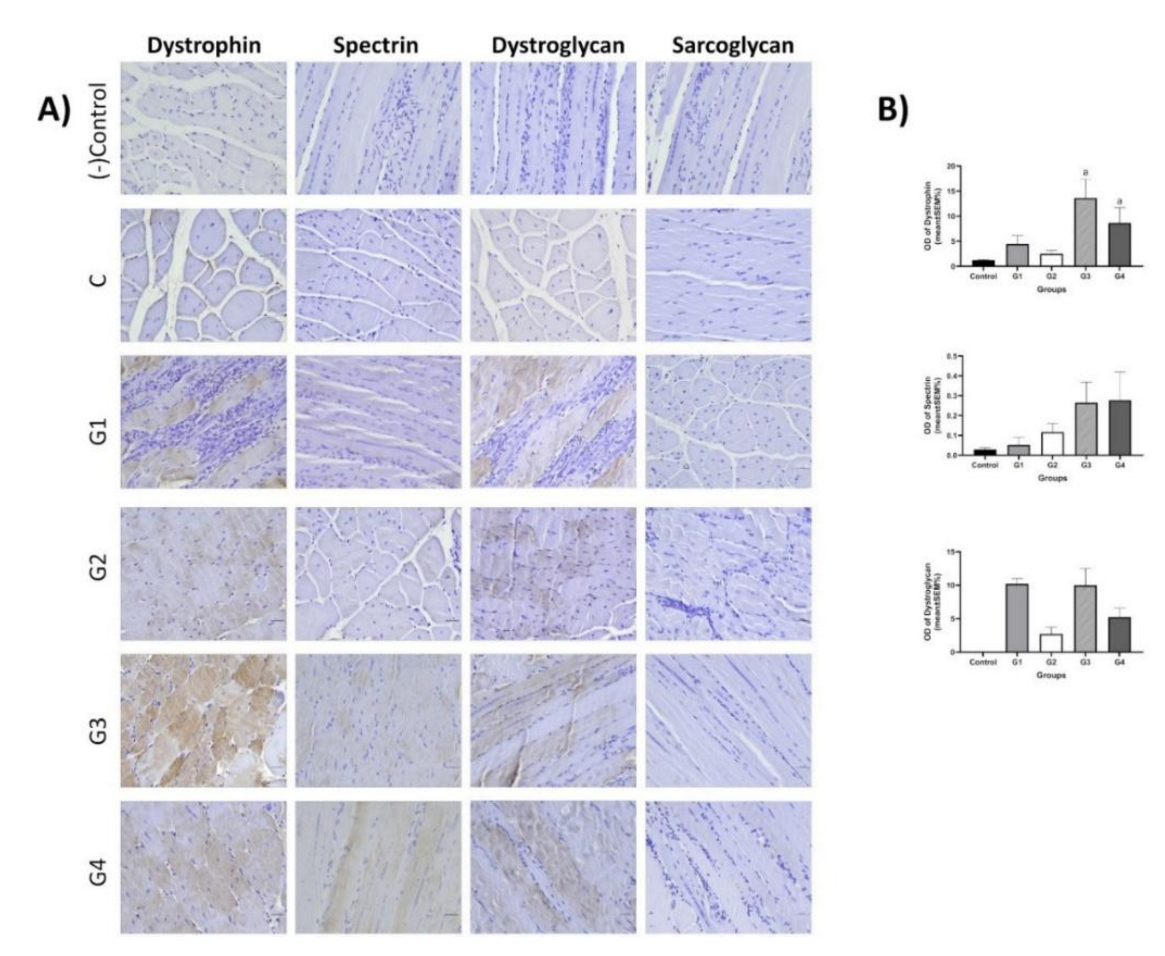

28]. Subsequently, the muscles’ regenerative capacity appears exhausted, and muscle fibers are gradually replaced by connective and fatty tissue. Therefore, the symptoms of Duchenne muscular dystrophy are thought to result from an imbalance between muscle fiber necrosis and myoblast regeneration. Necrosis is the primary pathological feature, but animal evidence suggests that regenerative capacity may decline with age. In our study, histopathological examination of the control DMD group revealed myofibrils of varying sizes, generally rounded in cross-section, with centrally located nuclei. Inflammatory cell infiltration and areas of necrotic tissue were observed. These histopathological findings were also observed in the other EX52, EX48, EX51, and EX47 groups, but these findings decreased from EX52 to EX47.

Immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate dystrophin, spectrin, dystroglycan, and sarcoglycan expression in striated muscle tissue from each group. Dystrophin expression increased in the EX51 (13.6±3.8%) and EX47 (8.63±3.06%) groups compared to the control group (1.24±0.09%) (P<0.05).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C., S.G., O.C., and A.T.; methodology, D.C., B.A., D.G.F., S.Y., S.B., K.K., E.N., O.C., E.S., M.K., S.G., and A.T.; validation, D.C., and S.G.; investigation, D.C., S.G., O.C., and A.T.; data curation, D.C., B.A., D.G.F., S.Y., S.B., K.K., E.N., O.C., E.S., M.K., S.G., and A.T.; writing D.C., B.A., D.G.F., S.Y., S.B., K.K., E.N., O.C., E.S., M.K., S.G., and A.T.; writing review and editing, D.C., B.A., D.G.F., S.Y., S.B., K.K., E.N., O.C., E.S., M.K., S.G., and A.T.; supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

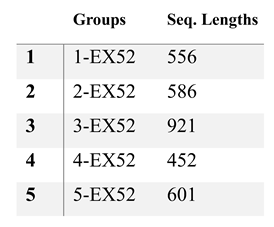

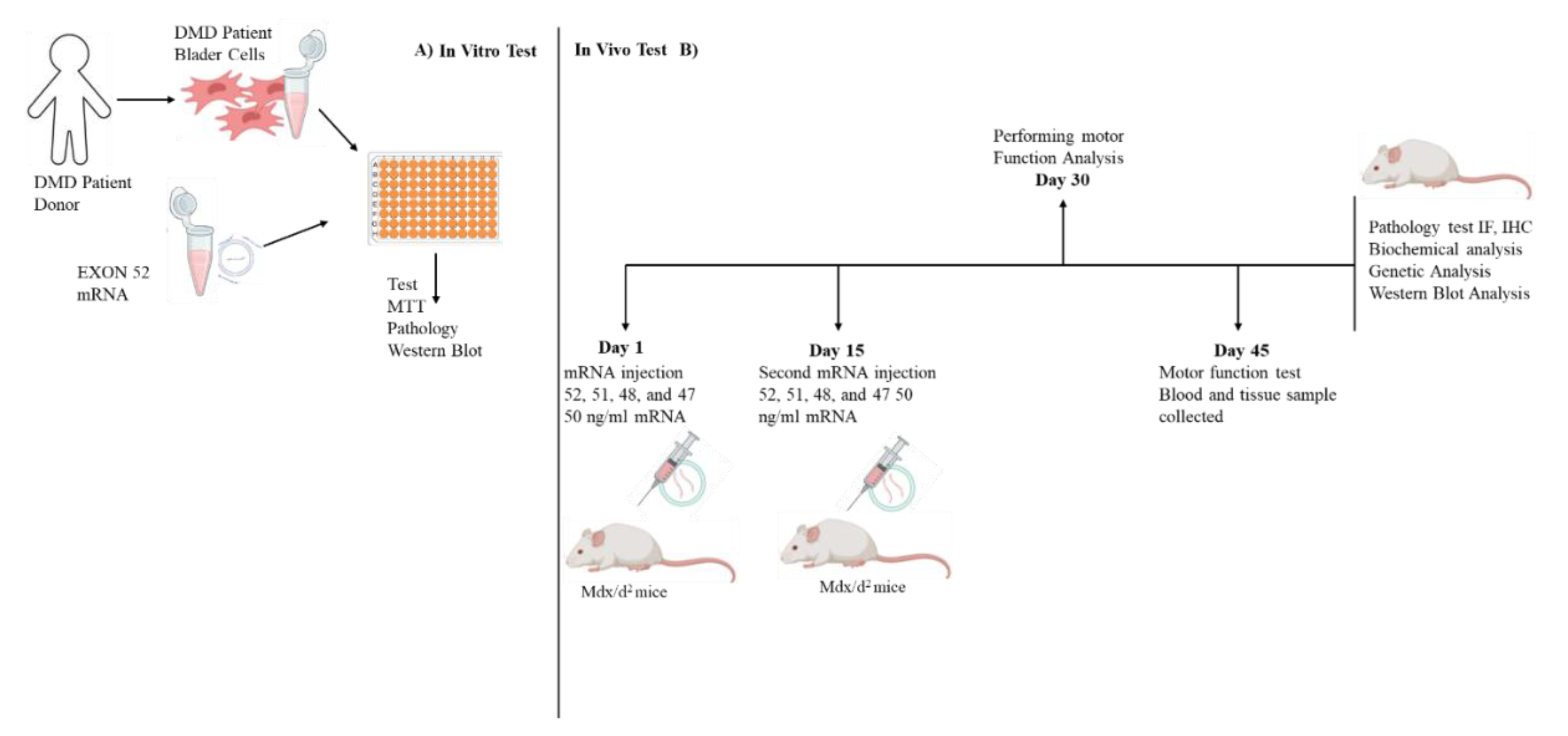

Figure 1.

Experiment design. A) In vitro analysis: Primary cells were collected from DMD patients. A primer cell was used to select an effective mRNA sequence. B) In vivo analysis was performed on mdx/d2 mice: mRNA from exons 52, 51, 48, and 47 was tested in primary isolated cells.

Figure 1.

Experiment design. A) In vitro analysis: Primary cells were collected from DMD patients. A primer cell was used to select an effective mRNA sequence. B) In vivo analysis was performed on mdx/d2 mice: mRNA from exons 52, 51, 48, and 47 was tested in primary isolated cells.

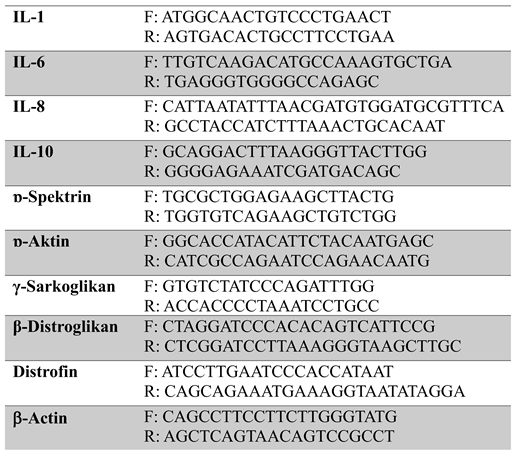

Figure 2.

Different WB results for 52 exon-mRNA treatments are shown. Expression of Spectrin α, α-actinin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, and Dystrophin is displayed.

Figure 2.

Different WB results for 52 exon-mRNA treatments are shown. Expression of Spectrin α, α-actinin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, and Dystrophin is displayed.

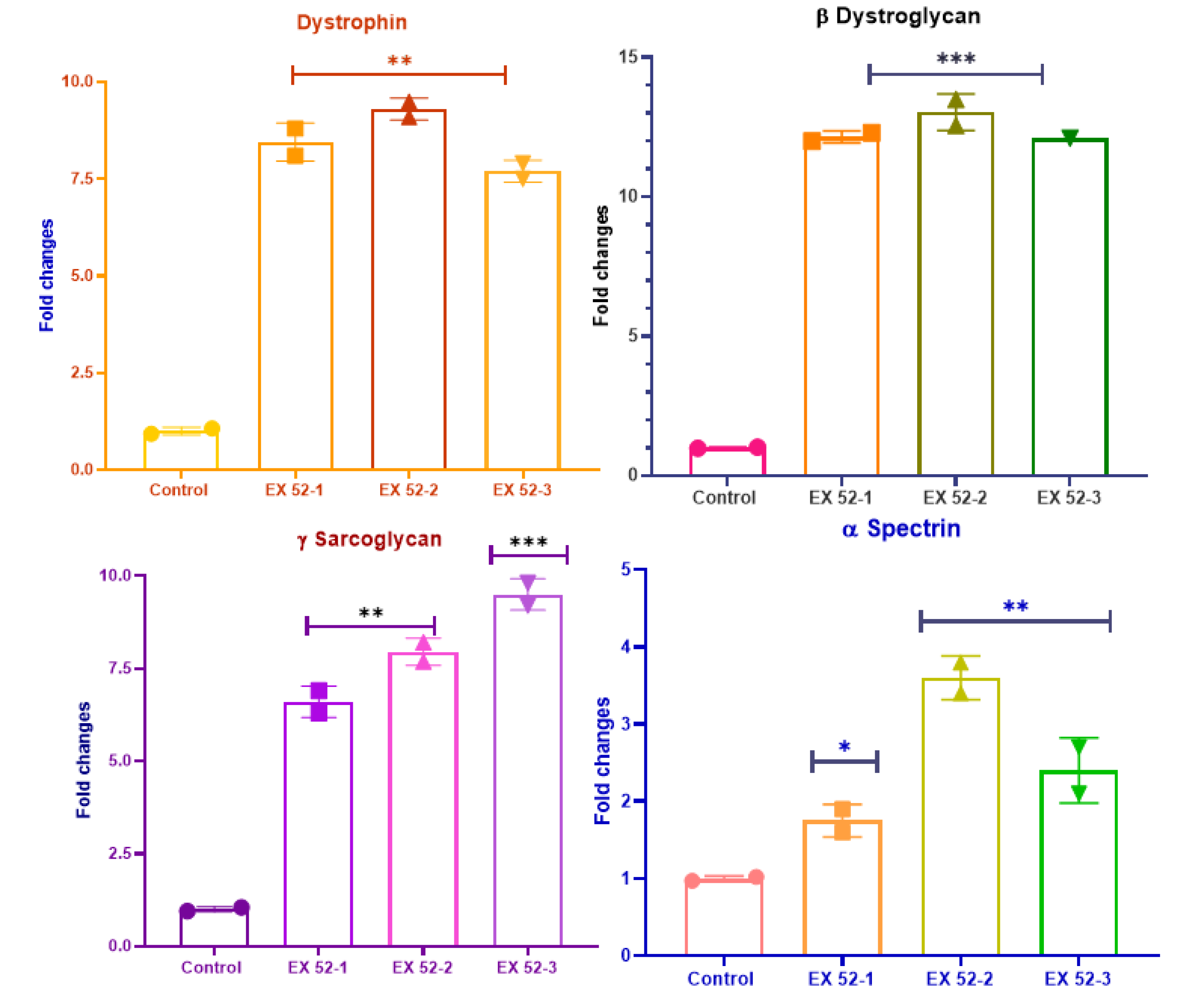

Figure 3.

DMD muscle cells obtained from primary cell culture and dystrophin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, and ɒ-Spectrin levels.

Figure 3.

DMD muscle cells obtained from primary cell culture and dystrophin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, and ɒ-Spectrin levels.

Figure 4.

Behavioral test results of mdx/d2 mouse groups (**P<0.01).

Figure 4.

Behavioral test results of mdx/d2 mouse groups (**P<0.01).

Figure 5.

TAC, TOS, NO, Klotho, and PPARγ levels in muscle tissues obtained from mdx/d2 mice.

Figure 5.

TAC, TOS, NO, Klotho, and PPARγ levels in muscle tissues obtained from mdx/d2 mice.

Figure 6.

Muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice and dystrophin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, ɒ-Spectrin, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 expression levels.

Figure 6.

Muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice and dystrophin, β-Dystroglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, ɒ-Spectrin, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 expression levels.

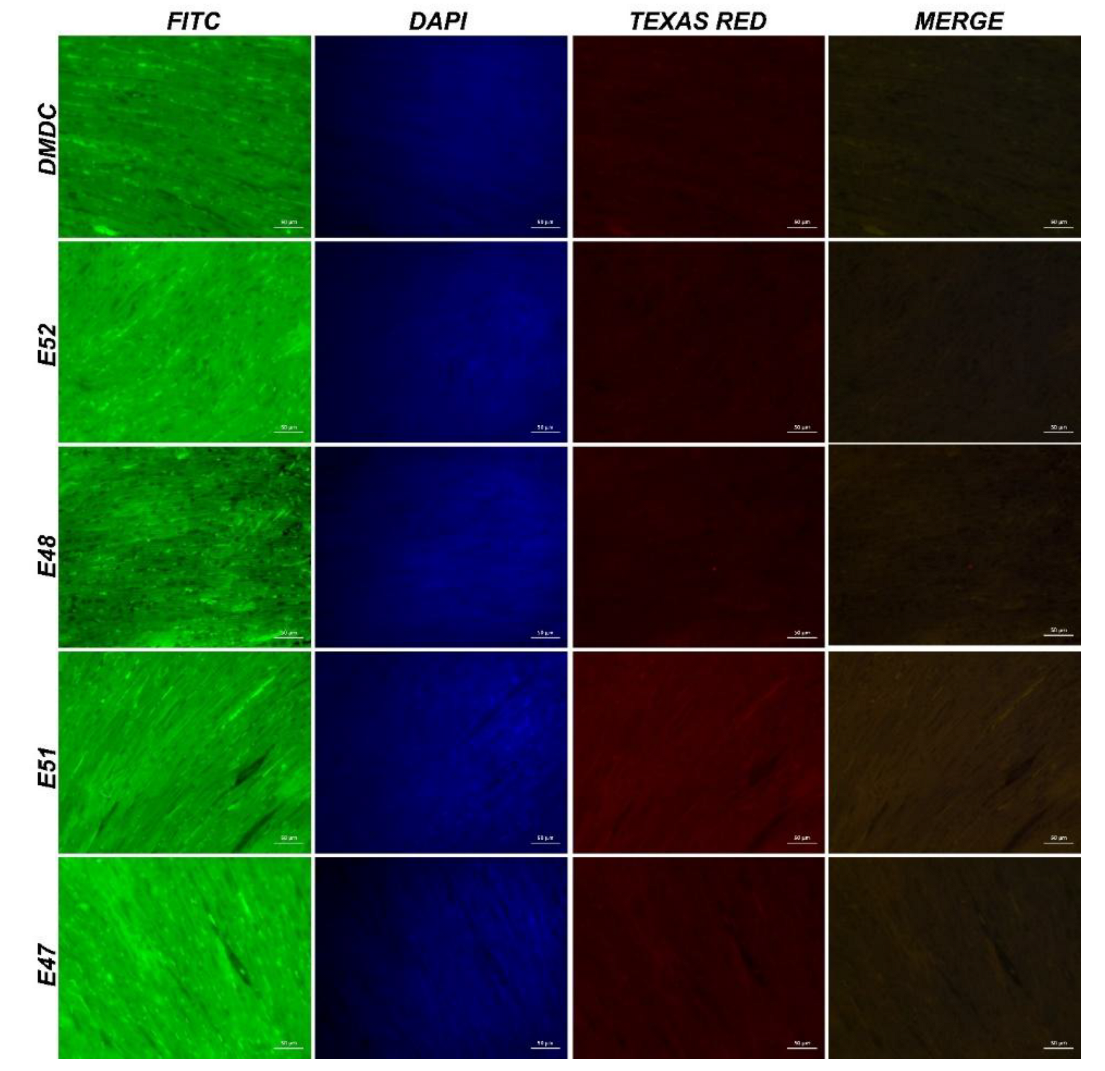

Figure 7.

IF images of cardiac muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic Spectrin α expressions (FITC) and α-actinin expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

Figure 7.

IF images of cardiac muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic Spectrin α expressions (FITC) and α-actinin expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

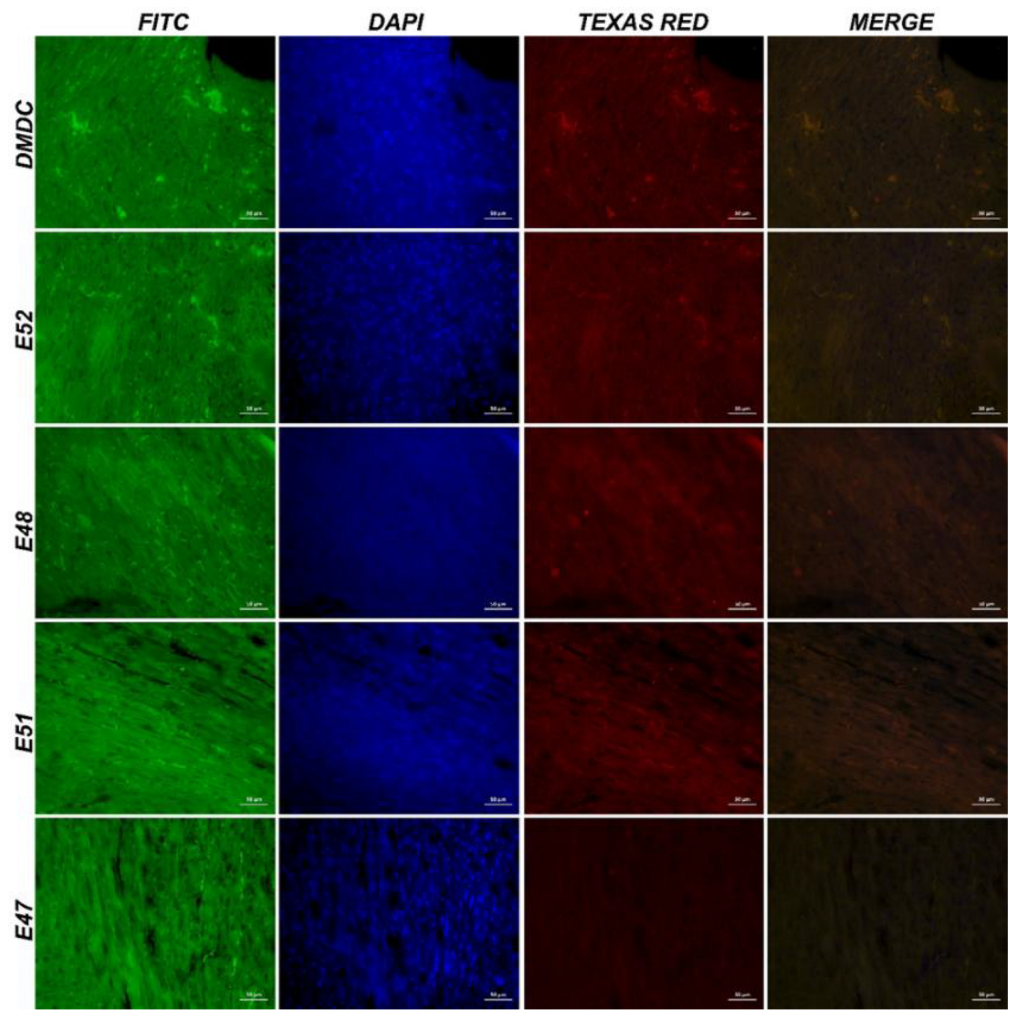

Figure 8.

IF images of muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic Spectrin α expressions (FITC) and α-actinin expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

Figure 8.

IF images of muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic Spectrin α expressions (FITC) and α-actinin expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

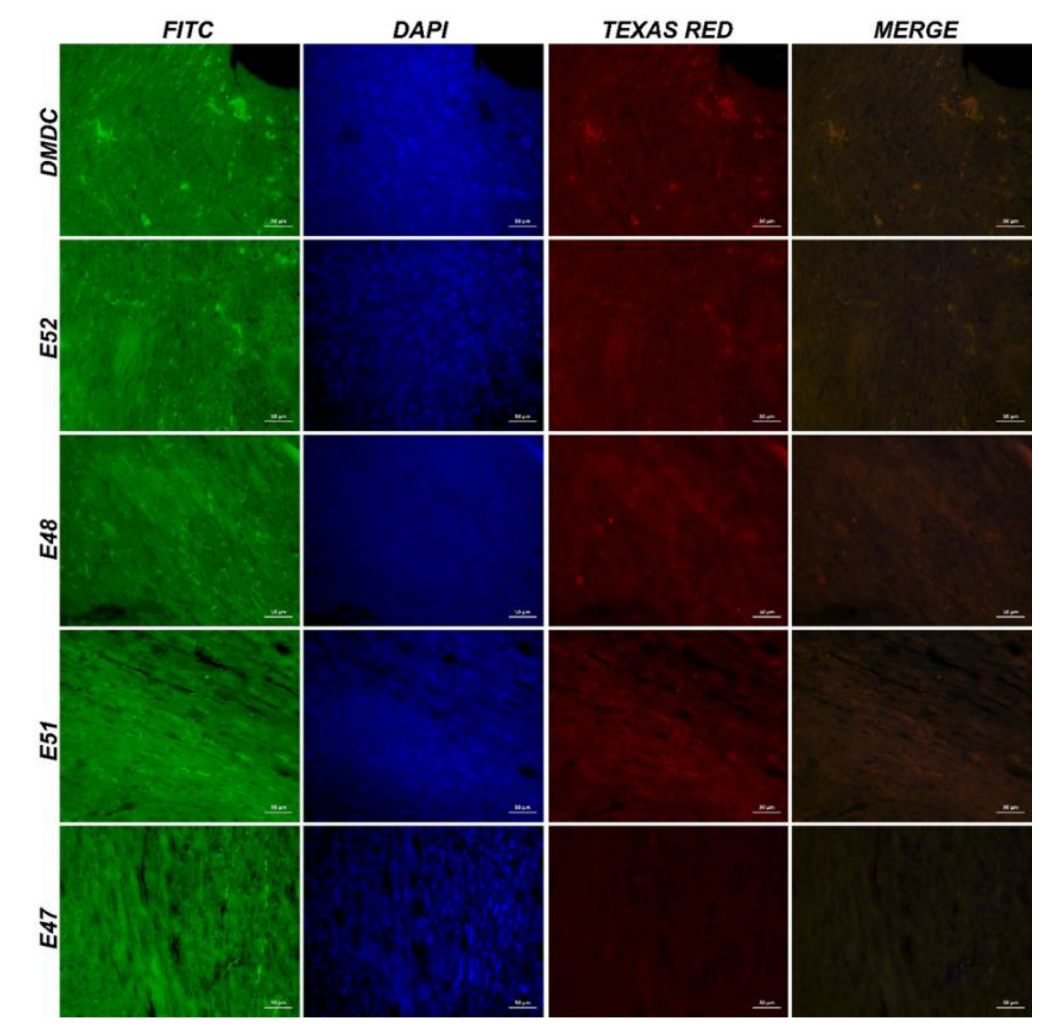

Figure 9.

IF images of cardiac muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic β-dystroglycan expressions (FITC) and γ-sarcoglycan expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

Figure 9.

IF images of cardiac muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic β-dystroglycan expressions (FITC) and γ-sarcoglycan expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

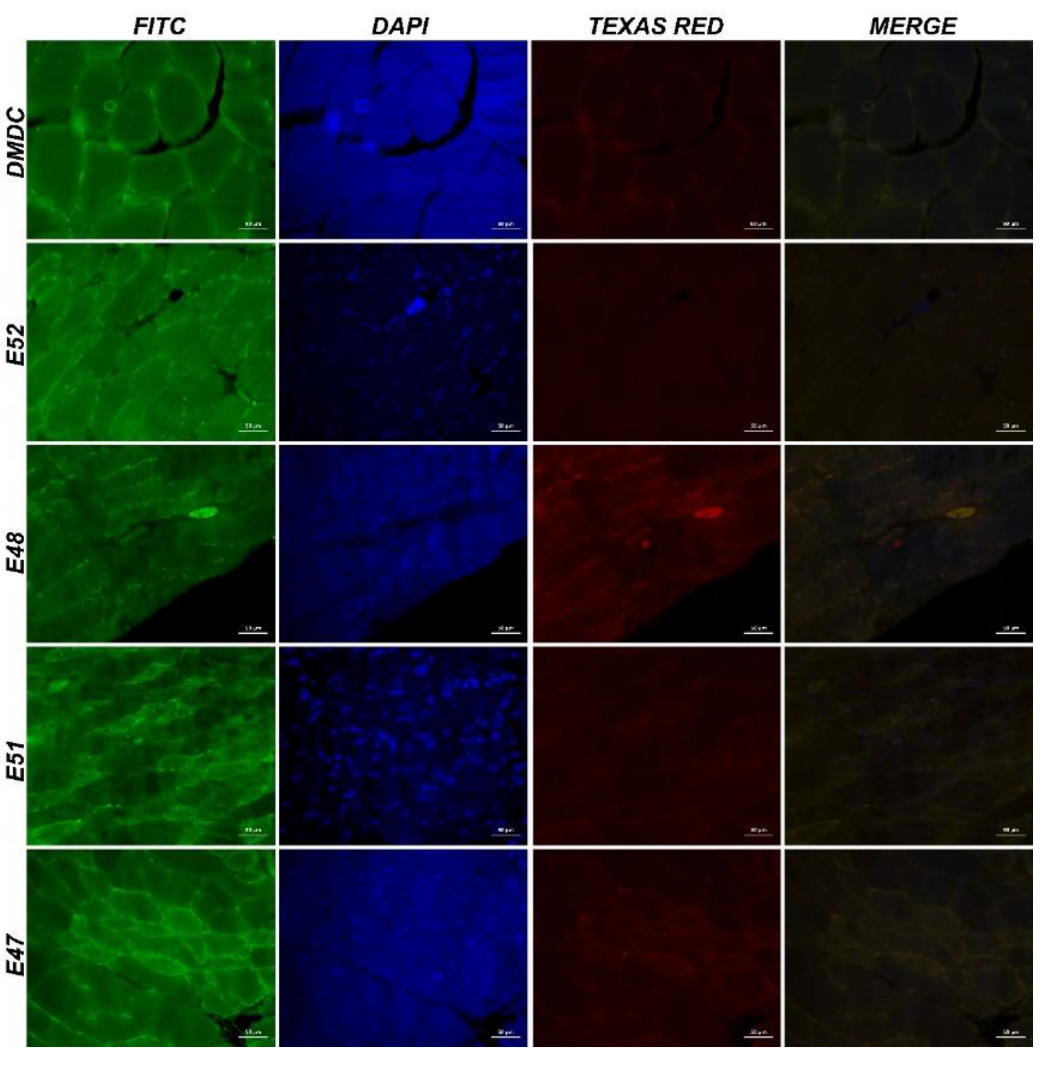

Figure 10.

IF image of muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic β-dystroglycan expressions (FITC) and γ-sarcoglycan expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

Figure 10.

IF image of muscle tissue obtained from mdx/d2 mice (Intracytoplasmic β-dystroglycan expressions (FITC) and γ-sarcoglycan expressions (Texas Red) in myocytes, IF, Bar: 50µm).

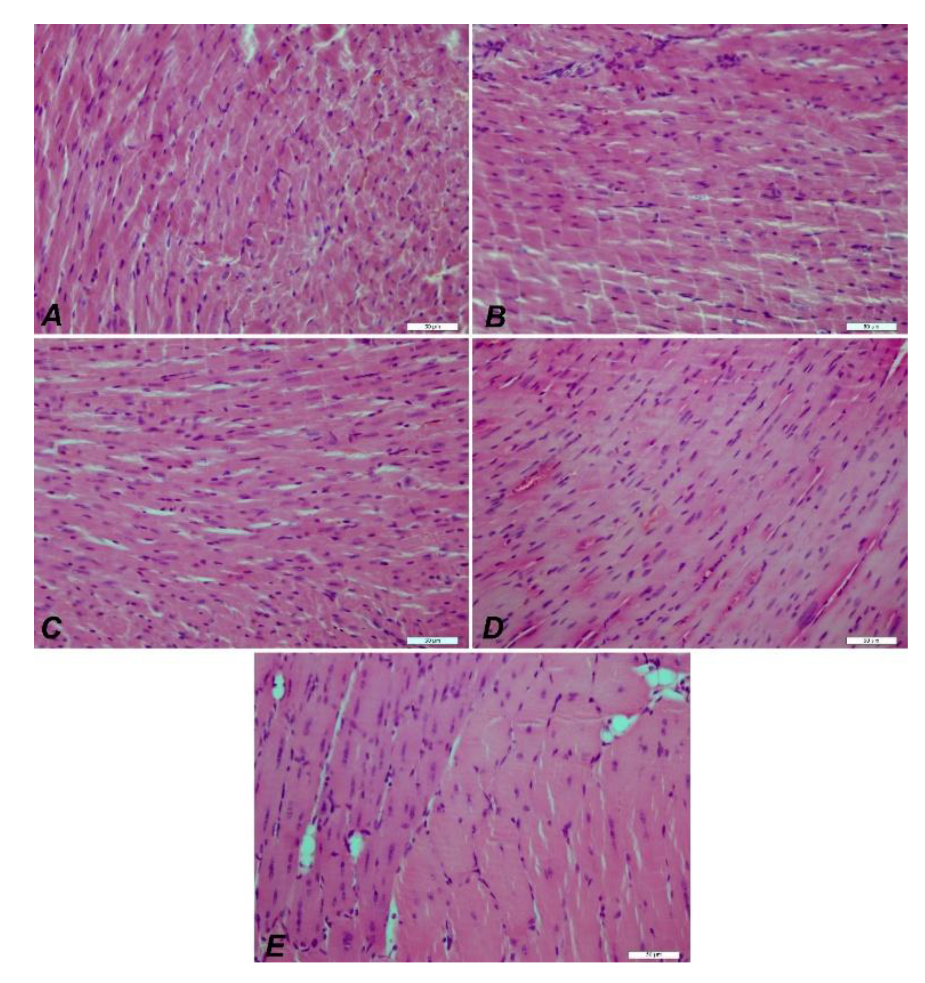

Figure 11.

IHC images of cardiac muscle tissue from mdx/d2 mice. Degeneration and necrosis in DMD Control (A), E52 (B), E48 (C), E51 (D), E47 (E) myocytes, inflammation in interstitial spaces, H&E, Bar: 50µm.

Figure 11.

IHC images of cardiac muscle tissue from mdx/d2 mice. Degeneration and necrosis in DMD Control (A), E52 (B), E48 (C), E51 (D), E47 (E) myocytes, inflammation in interstitial spaces, H&E, Bar: 50µm.

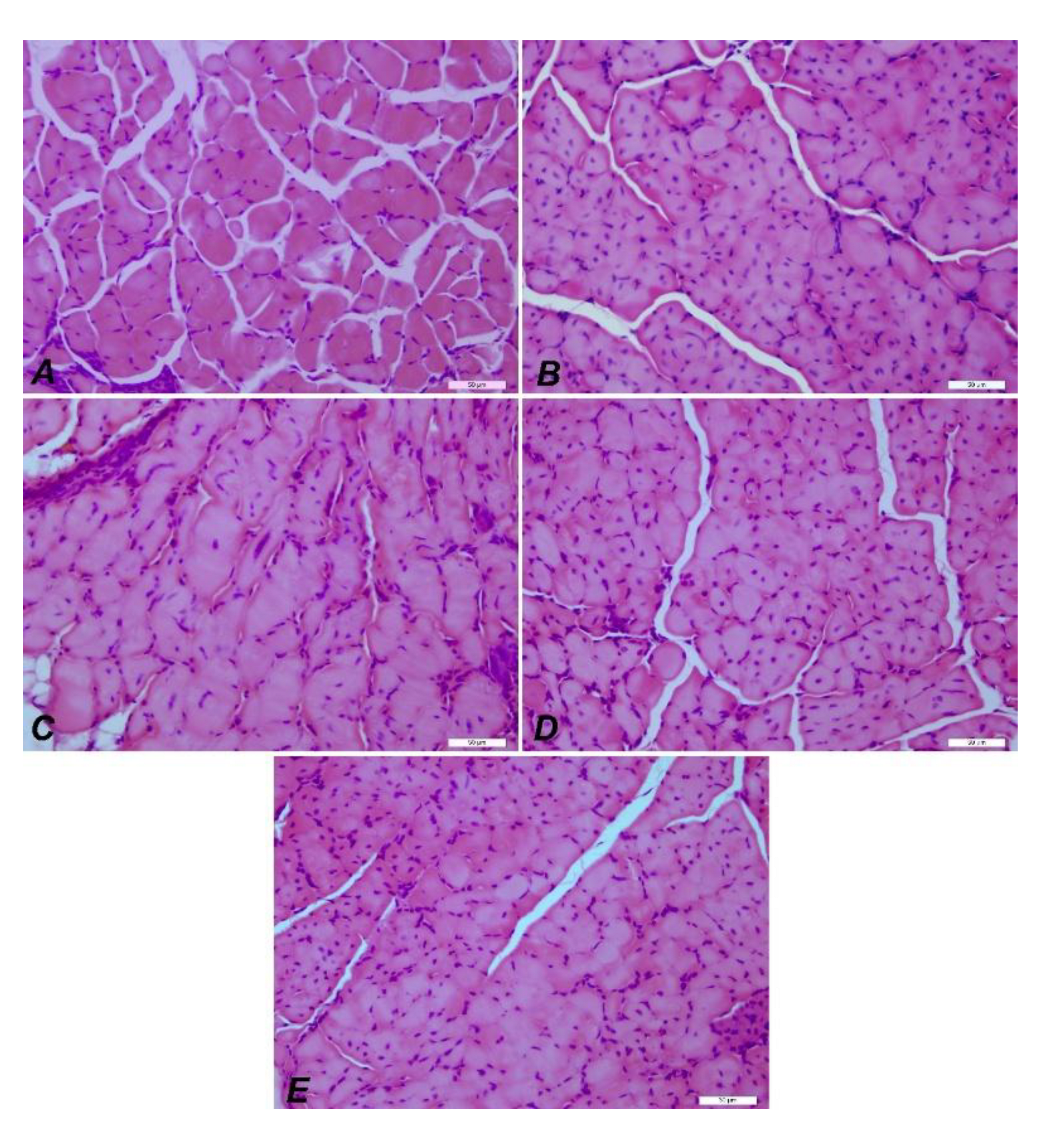

Figure 12.

IHC images of muscle tissue from mdx/d2 mice. DMD Control (A), E52 (B), E48 (C), E51 (D), E47 (E) myocyte degeneration and necrosis, inflammation in interstitial spaces, H&E, Bar: 50µm.

Figure 12.

IHC images of muscle tissue from mdx/d2 mice. DMD Control (A), E52 (B), E48 (C), E51 (D), E47 (E) myocyte degeneration and necrosis, inflammation in interstitial spaces, H&E, Bar: 50µm.

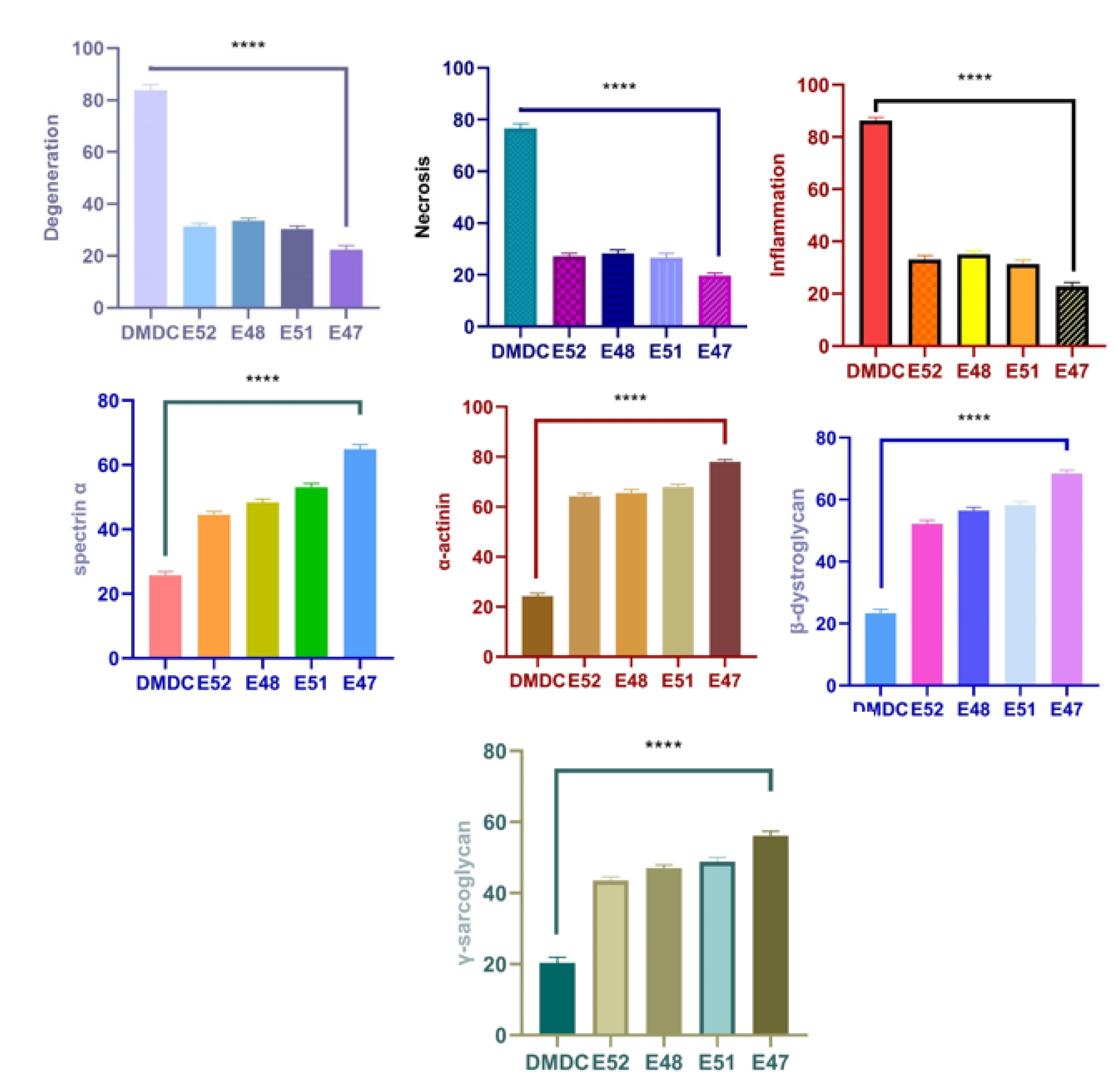

Figure 13.

Statistical analysis of histopathological findings and immunofluorescence staining results seen in muscle tissue. Myocyte degeneration (****P<0.0001), myocyte necrosis (****P<0.0001), inflammation (****P<0.0001), Spectrin α expression levels (****P<0.0001), α-actinin expression levels (****P<0.0001), and β-dystroglycan expression levels (****P<0.0001), γ-sarcoglycan expression levels (****P<0.0001).

Figure 13.

Statistical analysis of histopathological findings and immunofluorescence staining results seen in muscle tissue. Myocyte degeneration (****P<0.0001), myocyte necrosis (****P<0.0001), inflammation (****P<0.0001), Spectrin α expression levels (****P<0.0001), α-actinin expression levels (****P<0.0001), and β-dystroglycan expression levels (****P<0.0001), γ-sarcoglycan expression levels (****P<0.0001).

Figure 14.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the groups. Groups A: Control, B: EX52, C: EX48, D: EX51, and E: EX47. Although the pathological findings in the control group were observed in all groups, they decreased from EX52 to EX47. 50µm bars in all.

Figure 14.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the groups. Groups A: Control, B: EX52, C: EX48, D: EX51, and E: EX47. Although the pathological findings in the control group were observed in all groups, they decreased from EX52 to EX47. 50µm bars in all.

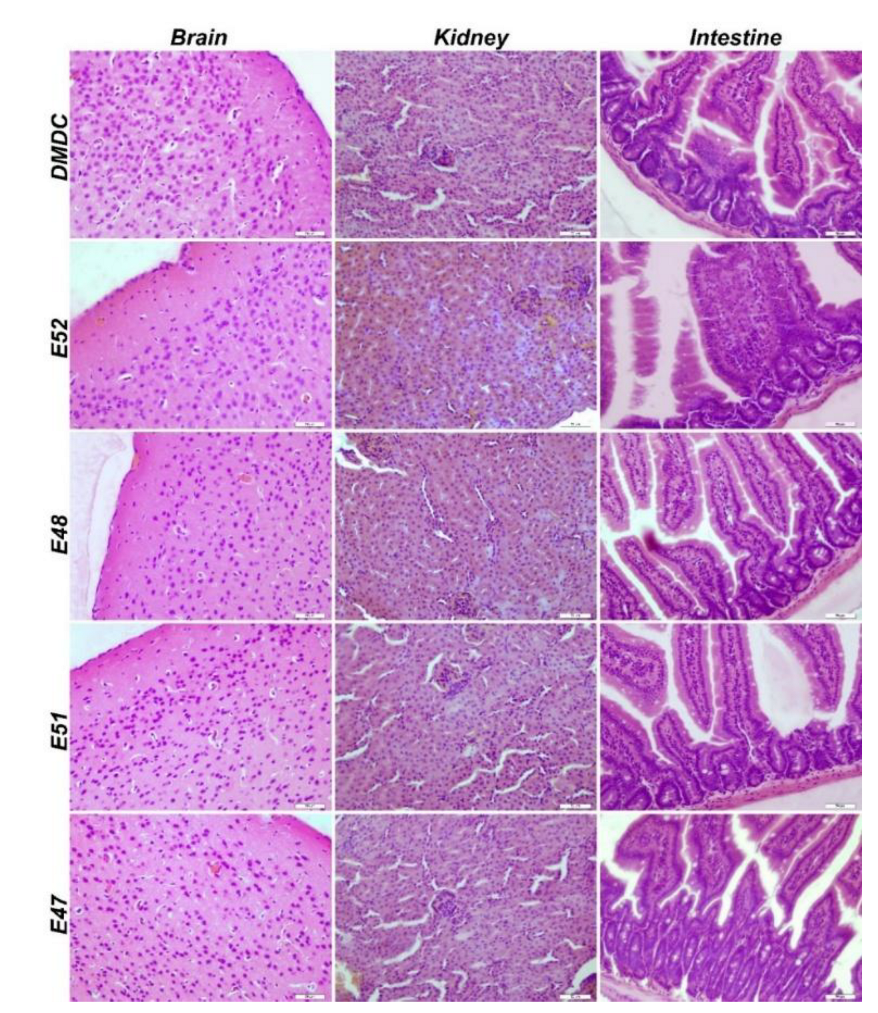

Figure 15.

IHC staining of brain, kidney, and intestinal tissues of dmx/d2 mice (Control, H&E, Bar: 50µm). This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Figure 15.

IHC staining of brain, kidney, and intestinal tissues of dmx/d2 mice (Control, H&E, Bar: 50µm). This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.