Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

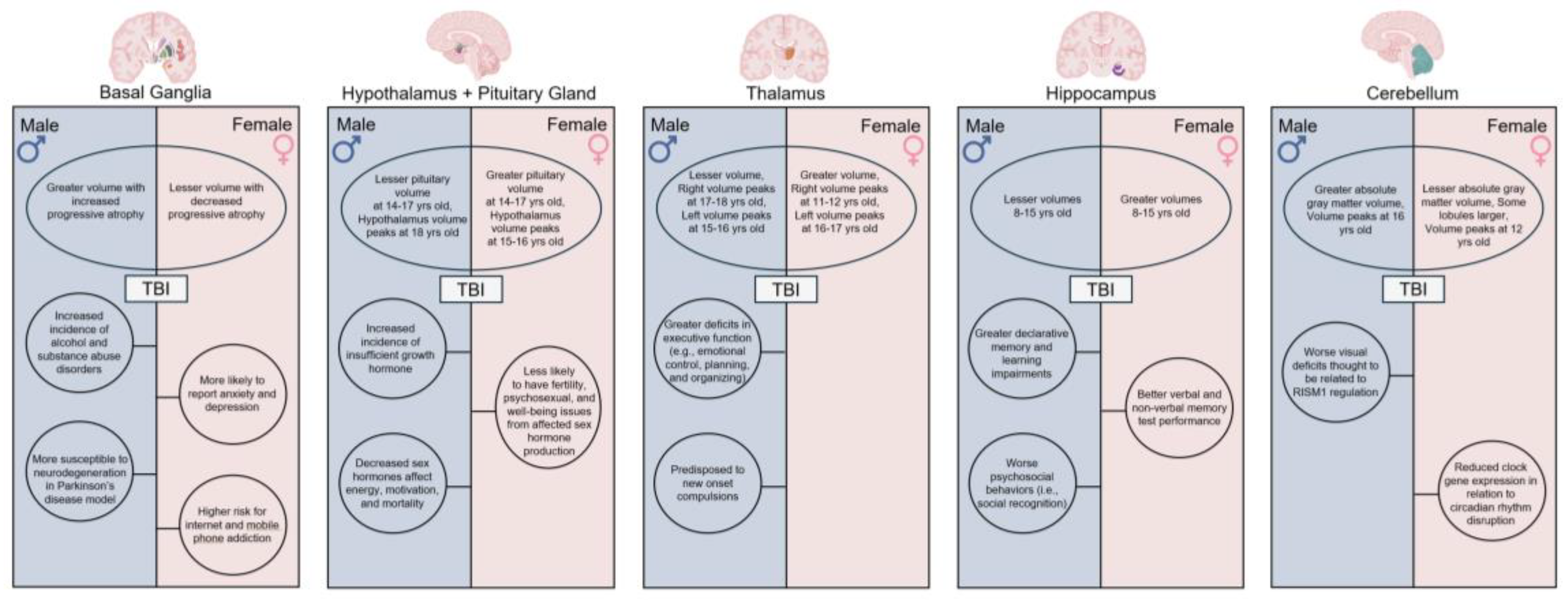

2. Sexual Dimorphisms in Specific Brain Structures

2.1. The Basal Ganglia

2.1.1. The Putamen

2.1.2. The Globus Pallidus

2.2. The Limbic System

2.2.1. The Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland

2.2.2. The Thalamus

2.2.3. The Hippocampus

2.3. The Cerebellum

3. Sexual Dimorphisms in Specific White and Gray Matter Compartments

3.1. White Matter

3.2. Gray Matter

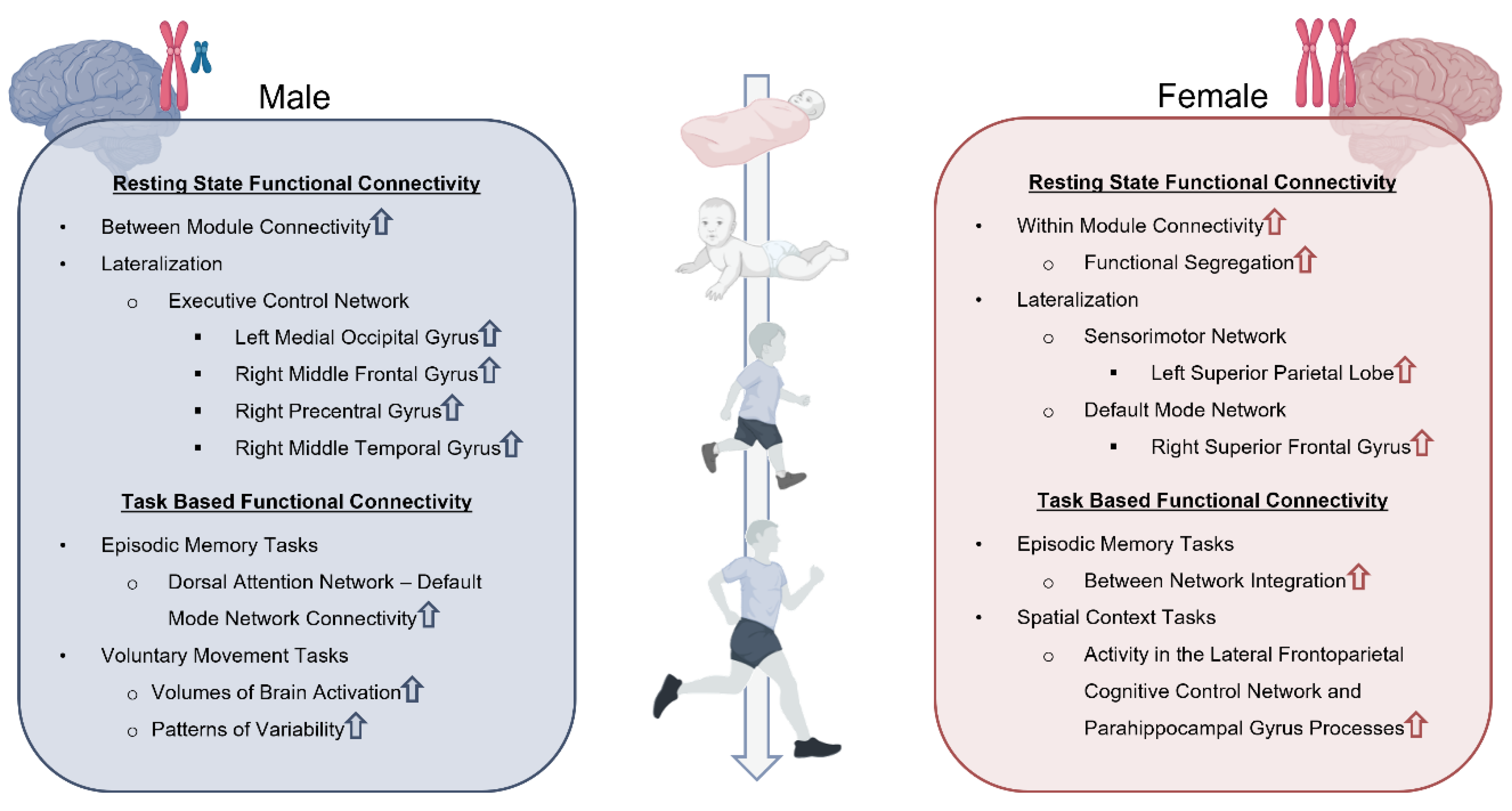

4. Sexual Dimorphisms in Functional Connectivity

4.1. Resting-State Functional Connectivity

4.2. Task-Based Functional Connectivity

5. Considerations and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Transparency: Rigor, and Reproducibility Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| ED | Emergency department |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| ADHD | Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| DTI | Diffusion tensor imaging |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

References

- Chen, C.; Peng, J.; Sribnick, E.A.; Zhu, M.; Xiang, H. Trend of Age-Adjusted Rates of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury in U.S. Emergency Departments from 2006 to 2013. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Bell, J.M.; Breiding, M.J.; Xu, L. Traumatic Brain Injury–Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignacio, D.A.; Babikian, T.; Dennis, E.L.; Bickart, K.C.; Choe, M.; Snyder, A.R.; Brown, A.; Giza, C.C.; Asarnow, R.F. The neurocognitive correlates of DTI indicators of white matter disorganization in pediatric moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1470710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H.S.; Temkin, N.R.; Barber, J.; Nelson, L.D.; Robertson, C.; Brennan, J.; Stein, M.B.; Yue, J.K.; Giacino, J.T.; McCrea, M.A.; et al. Association of Sex and Age With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury–Related Symptoms: A TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e213046–e213046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, K.E.; Greene, A.M.; Bondi, C.O.; Lajud, N.; de la Tremblaye, P.B.; Kline, A.E. Comparable impediment of cognitive function in female and male rats subsequent to daily administration of haloperidol after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 296, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.G.; Hammond, F.M.; Weintraub, A.H.; Nakase-Richardson, R.; Zafonte, R.D.; Whyte, J.; Giacino, J.T. Recovery of Consciousness and Functional Outcome in Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; Ley, E.J.; Tillou, A.; Cryer, G.; Margulies, D.R.; Salim, A. The Effect of Gender on Patients With Moderate to Severe Head Injuries. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2009, 67, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, E.E.; Downing, M.G.; Biernacki, K.; McKenzie, D.P.; Ponsford, J.L. Cognitive Reserve and Age Predict Cognitive Recovery after Mild to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 2753–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, H.T.; Clark, A.E.; Holubkov, R.; Cox, C.S.; Ewing-Cobbs, L. Psychosocial and Executive Function Recovery Trajectories One Year after Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: The Influence of Age and Injury Severity. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.M.; Arnold, A.P.; Ball, G.F.; Blaustein, J.D.; De Vries, G.J. Sex Differences in the Brain: The Not So Inconvenient Truth. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, P.E.; Knab, S. News from the Society for Women's Health Research: Subgroup Analysis in Clinical Trials: Detecting Sex Differences. J. Women's Heal. Gender-Based Med. 2002, 11, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.M.; Pickett, L.A.; VanRyzin, J.W.; Kight, K.E. Surprising origins of sex differences in the brain. Horm. Behav. 2015, 76, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, R.; Weiss, D.; Zafonte, R. Traumatic Brain Injury and Gender: What is Known and What is Not. Futur. Neurol. 2008, 3, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Luo, J.; Hu, M.; Zuo, C. Effects of Age and Sex on Subcortical Volumes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, M.; Qin, W.; Wan, B.; Yu, C.; Ming, D. Gender Differences Are Encoded Differently in the Structure and Function of the Human Brain Revealed by Multimodal MRI. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; van Tol, M.-J.; Li, M.; Miao, W.; Jiao, Y.; Heinze, H.-J.; Bogerts, B.; He, H.; Walter, M. Regional specificity of sex effects on subcortical volumes across the lifespan in healthy aging. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhausen, L.L.; Fröhner, J.H.; Lemaître, H.; Artiges, E.; Martinot, M.P.; Herting, M.M.; Sticca, F.; Banaschewski, T.; Barker, G.J.; Bokde, A.L.W.; et al. Adolescent to young adult longitudinal development of subcortical volumes in two European sites with four waves. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e26574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Iijima, K.-I.; Okada, K.; Yamashita, K. Gender Effects on Age-Related Changes in Brain Structure. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000, 21, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik-Olson, B.L.; Holshouser, B.; Ghosh, N.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Nichols, J.G.; Pivonka-Jones, J.; Tong, K.; Ashwal, S. Evolving White Matter Injury following Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.L.; Faskowitz, J.; Rashid, F.; Babikian, T.; Mink, R.; Babbitt, C.; Johnson, J.; Giza, C.C.; Jahanshad, N.; Thompson, P.M.; et al. Diverging volumetric trajectories following pediatric traumatic brain injury. NeuroImage: Clin. 2017, 15, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Ashman, T.; A Spielman, L.; Hibbard, M.R.; Silver, J.M.; Chandna, T.; A Gordon, W. Psychiatric challenges in the first 6 years after traumatic brain injury: cross-sequential analyses of axis I disorders11No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the authors(s) or upon any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2004, 85, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.; Zupan, B. Sex Differences in Emotional Insight After Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2020, 101, 1922–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, G.; E Mann, R.; Boak, A.; Adlaf, E.M.; Hamilton, H.; Asbridge, M.; Rehm, J.; Cusimano, M.D. Cross-sectional examination of the association of co-occurring alcohol misuse and traumatic brain injury on mental health and conduct problems in adolescents in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Heron, J.; Munafò, M. Substance use, criminal behaviour and psychiatric symptoms following childhood traumatic brain injury: findings from the ALSPAC cohort. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.A.; Jagannathan, L.; Jackson, L.R.; Becker, J.B. Sex differences in the effects of estradiol in the nucleus accumbens and striatum on the response to cocaine: Neurochemistry and behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 135, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, S.; Yang, C.; Jin, G.; Zhen, X. Estrogen regulates responses of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area to cocaine. Psychopharmacology 2008, 199, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.B.; Chartoff, E. Sex differences in neural mechanisms mediating reward and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viviani, R.; Dommes, L.; Bosch, J.; Steffens, M.; Paul, A.; Schneider, K.L.; Stingl, J.C.; Beschoner, P. Signals of anticipation of reward and of mean reward rates in the human brain. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joue, G.; Chakroun, K.; Bayer, J.; Gläscher, J.; Zhang, L.; Fuss, J.; Hennies, N.; Sommer, T. Sex Differences and Exogenous Estrogen Influence Learning and Brain Responses to Prediction Errors. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 32, 2022–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfel, E.L.; Aguinaldo, L.; Correa, K.; Courtney, K.E.; Max, J.E.; Tapert, S.F.; Jacobus, J. Traumatic brain injury, working memory-related neural processing, and alcohol experimentation behaviors in youth from the ABCD cohort. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2024, 66, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, C.; McKinlay, A.; McLellan, T.; Britt, E.; Grace, R.; MacFarlane, M. A comparison of adult outcomes for males compared to females following pediatric traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhornitsky, S.; Le, T.M.; Wang, W.; Li, C.-S.R.; Zhang, S. Depression Mediates the Relationship between Childhood Trauma and Internet Addiction in Female but Not Male Chinese Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.P.; White, K.M.; Cox, S.; Young, R.M. Keeping in constant touch: The predictors of young Australians’ mobile phone involvement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.-Y.; Chiu, S.-I.; Huang, D.-H. A model of the relationship between psychological characteristics, mobile phone addiction and use of mobile phones by Taiwanese university female students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østby, Y.; Tamnes, C.K.; Fjell, A.M.; Westlye, L.T.; Due-Tønnessen, P.; Walhovd, K.B. Heterogeneity in Subcortical Brain Development: A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Brain Maturation from 8 to 30 Years. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 11772–11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowell, E.R.; et al. Development of cortical and subcortical brain structures in childhood and adolescence: a structural MRI study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002, 44, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolschijn, P.C.M.; Crone, E.A. Sex differences and structural brain maturation from childhood to early adulthood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2013, 5, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijpkema, M.; Everaerd, D.; van der Pol, C.; Franke, B.; Tendolkar, I.; Fernández, G. Normal sexual dimorphism in the human basal ganglia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2012, 33, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedelahi, A.; Hasanzadeh, H.; Hadizadeh, H.; Joghataie, M.T. Morphometric and volumetric study of caudate and putamen nuclei in normal individuals by MRI: Effect of normal aging, gender and hemispheric differences. Pol. J. Radiol. 2013, 78, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, W.M.; Husain, M.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Figiel, G.; Boyko, O.; Krishnan, K.R.R. A magnetic resonance image study of age-related changes in human putamen nuclei. NeuroReport 1991, 2, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, N.J.; Demarchi, C.; De Simoni, S.; Samra, R.; Patel, M.C.; Kuczynski, A.; Mok, Q.; Wimalasundera, N.; Vargha-Khadem, F.; Sharp, D.J. Brain volume abnormalities and clinical outcomes following paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain 2022, 145, 2920–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molteni, E.; Pagani, E.; Strazzer, S.; Arrigoni, F.; Beretta, E.; Boffa, G.; Galbiati, S.; Filippi, M.; Rocca, M.A. Fronto-temporal vulnerability to disconnection in paediatric moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooijers, J.; Chalavi, S.; Beeckmans, K.; Michiels, K.; Lafosse, C.; Sunaert, S.; Swinnen, S.P. Subcortical Volume Loss in the Thalamus, Putamen, and Pallidum, Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury, Is Associated With Motor Performance Deficits. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2016, 30, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Alexander, G.; DeLong, M.R.; Strick, P.L. Parallel Organization of Functionally Segregated Circuits Linking Basal Ganglia and Cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1986, 9, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Hungerford, G.M.; Bagner, D.M. Topical Review: Negative Behavioral and Cognitive Outcomes Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Early Childhood. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Mao, Q.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Li, C.-S.R. Putamen gray matter volumes in neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. . 2019, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, G.J.; Pearlson, G.D.; Peyser, C.E.; Aylward, E.H.; Roberts, J.; Barta, P.E.; Chase, G.A.; Folstein, S.E. Putamen volume reduction on magnetic resonance imaging exceeds caudate changes in mild Huntington's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, D.A.; et al. Atrophy of the putamen in dementia with Lewy bodies but not Alzheimer's disease: an MRI study. Neurology 2003, 61, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, L.W.; van der Hiele, K.; Veer, I.M.; Houwing, J.J.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Bollen, E.L.E.M.; de Bruin, P.W.; Middelkoop, H.A.M.; van Buchem, M.A.; van der Grond, J. Strongly reduced volumes of putamen and thalamus in Alzheimer's disease: an MRI study. Brain 2008, 131 Pt 12 Pt 12, 3277–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, J.; Meuth, S.G.; Tenberge, J.-G.; Schiffler, P.; Wiendl, H.; Deppe, M. Early and Degressive Putamen Atrophy in Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23195–23209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, T.M.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging volumetric analysis of the putamen in children with ADHD: combined type versus control. J Atten Disord 2006, 10, 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.M.; et al. A magnetic resonance imaging study of putamen nuclei in major depression. Psychiatry Res 1991, 40, 95–9. [Google Scholar]

- Leunissen, I.; Coxon, J.P.; Caeyenberghs, K.; Michiels, K.; Sunaert, S.; Swinnen, S.P. Subcortical volume analysis in traumatic brain injury: The importance of the fronto-striato-thalamic circuit in task switching. Cortex 2014, 51, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, P.; Auzias, G.; Lefevre, J.; Takerkart, S.; Coulon, O.; Lesimple, B.; Torkomian, G.; Battisti, V.; Jacquens, A.; Couret, D.; et al. Long-term follow-up of neurodegenerative phenomenon in severe traumatic brain injury using MRI. Ann. Phys. Rehabilitation Med. 2022, 65, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.K.; Bathula, S.; Jeong, S.; Arruri, V.; Choi, J.; Subramanian, S.; Ostrom, C.M.; Vemuganti, R. An antioxidant and anti-ER stress combination therapy elevates phosphorylation of α-Syn at serine 129 and alleviates post-TBI PD-like pathology in a sex-specific manner in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 377, 114795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, P.O.; Roussakis, A.-A.; De Simoni, S.; Bourke, N.; Fleminger, J.; Cole, J.; Piccini, P.; Sharp, D. Distinct dopaminergic abnormalities in traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettemeridou, E.; Constantinidou, F. The cortical and subcortical substrates of quality of life through substrates of self-awareness and executive functions, in chronic moderate-to-severe TBI. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drijkoningen, D.; Chalavi, S.; Sunaert, S.; Duysens, J.; Swinnen, S.P.; Caeyenberghs, K. Regional Gray Matter Volume Loss Is Associated with Gait Impairments in Young Brain-Injured Individuals. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.L. , et al. Differences in Brain Volume in Military Service Members and Veterans After Blast-Related Mild TBI: A LIMBIC-CENC Study. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2443416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemann, C.; Godde, B.; Staudinger, U.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. Exercise-induced changes in basal ganglia volume and cognition in older adults. Neuroscience 2014, 281, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, C.; Hinson, H.E.; Baguley, I.J. Autonomic dysfunction syndromes after acute brain injury. Clin Neurol 2015, 128, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedd, J.N.; Rapoport, J.L. Structural MRI of Pediatric Brain Development: What Have We Learned and Where Are We Going? Neuron 2010, 67, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, A.; Rohlfing, T.; Rosenbloom, M.J.; Chu, W.; Colrain, I.M.; Sullivan, E.V. Variation in longitudinal trajectories of regional brain volumes of healthy men and women (ages 10 to 85years) measured with atlas-based parcellation of MRI. NeuroImage 2013, 65, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMaster, F.P.; Keshavan, M.; Mirza, Y.; Carrey, N.; Upadhyaya, A.R.; El-Sheikh, R.; Buhagiar, C.J.; Taormina, S.P.; Boyd, C.; Lynch, M.; et al. Development and sexual dimorphism of the pituitary gland. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.W.; Rafful, P.P.; Vidarsson, L.; Ertl-Wagner, B.B. MRI Volumetric Analysis of the Hypothalamus and Limbic System across the Pediatric Age Span. Children 2023, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlad, R.M.; Albu, A.I.; Nicolaescu, I.D.; Dobritoiu, R.; Carsote, M.; Sandru, F.; Albu, D.; Păcurar, D. An Approach to Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Hypopituitarism: Overcoming the Pediatric Challenges. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.P.; Bhatnagar, S.; Herman, S.D.; Zafonte, R.; Klibanski, A.; Miller, K.K.; Tritos, N.A. Predictors of Hypopituitarism in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Personnier, C.; Crosnier, H.; Meyer, P.; Chevignard, M.; Flechtner, I.; Boddaert, N.; Breton, S.; Mignot, C.; Dassa, Y.; Souberbielle, J.-C.; et al. Prevalence of Pituitary Dysfunction After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Children and Adolescents: A Large Prospective Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessen, L.Ó.E.; Kristjánsdóttir, H.; Jónsdóttir, M.K.; Lund, S.H.; Kristensen, I.U.; Sigurjónsdóttir, H.Á. Pituitary dysfunction following mild traumatic brain injury in female athletes. Endocr. Connect. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassa, Y. , et al. Pituitary deficiency and precocious puberty after childhood severe traumatic brain injury: a long-term follow-up prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 2019, 180, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S. , et al. Hypopituitarism After Traumatic Brain Injury. Cureus 2019, 11, e4163. [Google Scholar]

- Prodam, F.; Gasco, V.; Caputo, M.; Zavattaro, M.; Pagano, L.; Marzullo, P.; Belcastro, S.; Busti, A.; Perino, C.; Grottoli, S.; et al. Metabolic alterations in patients who develop traumatic brain injury (TBI)-induced hypopituitarism. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2013, 23, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemes, O.; Kovacs, N.; Czeiter, E.; Kenyeres, P.; Tarjanyi, Z.; Bajnok, L.; Buki, A.; Doczi, T.; Mezosi, E. Predictors of post-traumatic pituitary failure during long-term follow-up. Hormones 2015, 14, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acerini, C.L.; Tasker, R.C. Traumatic brain injury induced hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction: a paediatric perspective. Pituitary 2007, 10, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Ching, L.; Zasler, N.D.; Kreutzer, J.S. Male pituitary-gonadal dysfunction following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1994, 8, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederland, T.; Makovi, H.; Gál, V.; Andréka, B.; Ábrahám, C.S.; Kovács, J. Abnormalities of Pituitary Function after Traumatic Brain Injury in Children. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, A.; Rogers, B.; Sherlock, M.; O’kelly, P.; Tormey, W.; Phillips, J.; Thompson, C.J. Anterior Pituitary Dysfunction in Survivors of Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 4929–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.A.; De Bellis, M.D. The Relationship of Age, Gender, and IQ With the Brainstem and Thalamus in Healthy Children and Adolescents: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Volumetric Study. J. Child Neurol. 2012, 27, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, K.M.; Snyder, A.; Junge, C.; Reading, M.; Jarvis, S.; Squires, C.; Bigler, E.D.; Popuri, K.; Beg, M.F.; Taylor, H.G.; et al. Surface-based abnormalities of the executive frontostriatial circuit in pediatric TBI. NeuroImage: Clin. 2022, 35, 103136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, H.T.; Clark, A.E.; Holubkov, R.; Cox, C.S.; Ewing-Cobbs, L. Trajectories of Children's Executive Function After Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e212624–e212624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grados, M.A.; Vasa, R.A.; Riddle, M.A.; Slomine, B.S.; Salorio, C.; Christensen, J.; Gerring, J. New onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children and adolescents with severe traumatic brain injury. Depression Anxiety 2008, 25, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Choi, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B.-N.; Park, S.; Jung, K.-I.; Park, B.; Park, M.-H. The Association Between Hippocampal Volume and Level of Attention in Children and Adolescents. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierenga, L.; Langen, M.; Ambrosino, S.; van Dijk, S.; Oranje, B.; Durston, S. Typical development of basal ganglia, hippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum from age 7 to 24. NeuroImage 2014, 96, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, N.; Gunning-Dixon, F.; Head, D.; Rodrigue, K.M.; Williamson, A.; Acker, J.D. Aging, sexual dimorphism, and hemispheric asymmetry of the cerebral cortex: replicability of regional differences in volume. Neurobiol. Aging 2004, 25, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Collins, D.L.; Pruessner, M.; Evans, A.C. Age and Gender Predict Volume Decline in the Anterior and Posterior Hippocampus in Early Adulthood. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufang, S.; Specht, K.; Hausmann, M.; Güntürkün, O.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Fink, G.R.; Konrad, K. Sex Differences and the Impact of Steroid Hormones on the Developing Human Brain. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedd, J.N.; Vaituzis, A.C.; Hamburger, S.D.; Lange, N.; Rajapakse, J.C.; Kaysen, D.; Vauss, Y.C.; Rapoport, J.L. Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: Ages 4-18 years. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996, 366, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, M.; Whittle, S.; Yücel, M.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kline, A.; Simmons, J.; Allen, N.B. Mapping subcortical brain maturation during adolescence: evidence of hemisphere- and sex-specific longitudinal changes. Dev. Sci. 2013, 16, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamnes, C.K.; Bos, M.G.; van de Kamp, F.C.; Peters, S.; Crone, E.A. Longitudinal development of hippocampal subregions from childhood to adulthood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 30, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peper, J.S.; Brouwer, R.M.; Schnack, H.G.; van Baal, G.C.; van Leeuwen, M.; Berg, S.M.v.D.; de Waal, H.A.D.-V.; Boomsma, D.I.; Kahn, R.S.; Pol, H.E.H. Sex steroids and brain structure in pubertal boys and girls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peper, J.; Pol, H.H.; Crone, E.; van Honk, J. Sex steroids and brain structure in pubertal boys and girls: a mini-review of neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience 2011, 191, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peper, J.S.; Schnack, H.G.; Brouwer, R.M.; Van Baal, G.C.M.V.; Pjetri, E.; Székely, E.; van Leeuwen, M.; Van Den Berg, S.M.; Collins, D.L.; Evans, A.C.; et al. Heritability of regional and global brain structure at the onset of puberty: A magnetic resonance imaging study in 9-year-old twin pairs. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009, 30, 2184–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.H.; Yuan, B.K.; Tan, L.H. Effect of Gender on Development of Hippocampal Subregions From Childhood to Adulthood. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, A.M.; Nadig, A.; Seidlitz, J.; Reardon, P.K.; Mankiw, C.; McDermott, C.L.; Blumenthal, J.D.; Clasen, L.S.; Lalonde, F.; Lerch, J.P.; et al. Sex-biased trajectories of amygdalo-hippocampal morphology change over human development. NeuroImage 2020, 204, 116122–116122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, E.; Moser, M.; Andersen, P. Spatial learning impairment parallels the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal lesions, but is hardly present following ventral lesions. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 3916–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bear, M.F., B. W. Connors, and M.A. Paradiso, Neuroscience : exploring the brain. 3rd ed. 2007, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. xxxviii, 857 p.

- Lundy-Ekman, L. , Neuroscience : fundamentals for rehabilitation. 4th ed. 2013, St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier. xi, 539 p.

- Bazarian, J.J.; Blyth, B.; Mookerjee, S.; He, H.; McDermott, M.P. Sex Differences in Outcome after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.M.; Burgess, N. The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farace, E.; Alves, W.M. Do women fare worse: a metaanalysis of gender differences in traumatic brain injury outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, B.D.; Dixit, S.; Shultz, S.R.; Boon, W.C.; O’bRien, T.J. Sex-dependent changes in neuronal morphology and psychosocial behaviors after pediatric brain injury. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 319, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila-Valencia, I.; Saad, M.; Olthoff, G.; Faulkner, M.; Charara, M.; Farnum, A.; Dysko, R.C.; Zhang, Z. Sex specific effects of buprenorphine on adult hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioral outcomes during the acute phase after pediatric traumatic brain injury in mice. Neuropharmacology 2024, 245, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.C.; Rochowiak, R.N.; Plotkin, M.R.; Rosch, K.S.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Crocetti, D. Sex Differences and Behavioral Associations with Typically Developing Pediatric Regional Cerebellar Gray Matter Volume. Cerebellum 2024, 23, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.M.; D’mEllo, A.M.; McGrath, L.M.; Stoodley, C.J. The developmental relationship between specific cognitive domains and grey matter in the cerebellum. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipping, J.A.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, A. Cerebellar development and its mediation role in cognitive planning in childhood. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 5074–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C.J.; Chakravarty, M.M. Gray-matter structural variability in the human cerebellum: Lobule-specific differences across sex and hemisphere. NeuroImage 2018, 170, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgro, M.; Ellens, S.; Kodila, Z.N.; Christensen, J.; Li, C.; Mychasiuk, R.; Yamakawa, G.R. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury alters central and peripheral clock gene expression in the adolescent rat. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythm. 2023, 14, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.; Dixon, C.E.; Henchir, J.; Gorse, K.; Vagni, V.A.; Janesko-Feldman, K.; Kochanek, P.M.; Jackson, T.C. Gene knockout of RNA binding motif 5 in the brain alters RIMS2 protein homeostasis in the cerebellum and Hippocampus and exacerbates behavioral deficits after a TBI in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 374, 114690–114690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, K.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, R.; Gaebler, A.; Casals, N.; Scheller, A.; Kuerschner, L. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in grey and white matter regions of the brain metabolize fatty acids. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.G.; Julé, A.M.; Cullen, P.F.; Sun, D. Astrocyte heterogeneity within white matter tracts and a unique subpopulation of optic nerve head astrocytes. iScience 2022, 25, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, T.; Shan, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xiong, D.; Hauberg, M.E.; Bendl, J.; et al. Common genetic variation influencing human white matter microstructure. Science 2021, 372, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, K.E.; Abaryan, Z.; Laltoo, E.; Hernandez, L.M.; Gandal, M.J.; McCracken, J.T.; Thompson, P.M. White matter microstructure shows sex differences in late childhood: Evidence from 6797 children. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursache, A.; Noble, K.G. ; the Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics Study Socioeconomic status, white matter, and executive function in children. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, L.E.; Tubi, M.A.; Bright, J.; Thomopoulos, S.I.; Wieand, A.; Thompson, P.M. Sex is a defining feature of neuroimaging phenotypes in major brain disorders. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022, 43, 500–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; Colich, N.L.; Sisk, L.M.; Oskirko, K.; Jo, B.; Gotlib, I.H. Sex differences in the effects of gonadal hormones on white matter microstructure development in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 42, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hemmen, J.; Saris, I.M.J.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Veltman, D.J.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Bakker, J. Sex Differences in White Matter Microstructure in the Human Brain Predominantly Reflect Differences in Sex Hormone Exposure. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, bhw156–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartnik-Olson, B.L.; Holshouser, B.; Ghosh, N.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Nichols, J.G.; Pivonka-Jones, J.; Tong, K.; Ashwal, S. Evolving White Matter Injury following Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, E.M.; Yuh, E.L.; Mac Donald, C.L.; Bourla, I.; Wren-Jarvis, J.; Sun, X.; Vassar, M.J.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Giacino, J.T.; Okonkwo, D.O.; et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Reveals Elevated Diffusivity of White Matter Microstructure that Is Independently Associated with Long-Term Outcome after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.A.; Spitz, G.; Ponsford, J.L.; Dymowski, A.R.; Willmott, C. An investigation of white matter integrity and attention deficits following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, N.P.; Genc, S.; Beauchamp, M.H.; Yeates, K.O.; Hearps, S.; Catroppa, C.; Anderson, V.A.; Silk, T.J. White matter microstructure predicts longitudinal social cognitive outcomes after paediatric traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitz, G.; Alway, Y.; Gould, K.R.; Ponsford, J.L. Disrupted White Matter Microstructure and Mood Disorders after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhran, S.; Yaeger, K.; Collins, M.; Alhilali, L. Sex Differences in White Matter Abnormalities after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Localization and Correlation with Outcome. Radiology 2014, 272, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, D.F.; Jamieson, D.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Sacks, D.D.; Iorfino, F.; Crouse, J.J.; Guastella, A.J.; Scott, E.M.; Hickie, I.B.; Lagopoulos, J. Sex differences in fronto-limbic white matter tracts in youth with mood disorders. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 76, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, M.D.; Goodman, A.; Harnett, N.; Wood, K.; Mrug, S.; Granger, D.; Knight, D. Sex-related Differences in Stress Reactivity and Cingulum White Matter. Neuroscience 2021, 459, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowet, D.S.; Vaida, F.; Hesselink, J.R.; Ewing-Cobbs, L.; Schachar, R.J.; Chapman, S.B.; Bigler, E.D.; Wilde, E.A.; Saunders, A.E.; Yang, T.T.; et al. Novel Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder 24 Months After Traumatic Brain Injury in Children and Adolescents. J. Neuropsychiatry 2024, 36, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, E.; Scratch, S.E.; Ameis, S.H.; Wheeler, A.L. Disrupted Maturation of White Matter Microstructure After Concussion Is Associated With Internalizing Behavior Scores in Female Children. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 96, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, E.; Stojanovski, S.; Scratch, S.E.; Ameis, S.H.; Wheeler, A.L. Premature white matter microstructure in female children with a history of concussion. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 62, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.K.; Symons, G.F.; O’bRien, W.T.; McDonald, S.J.; Zamani, A.; Major, B.; Chen, Z.; Costello, D.; Brady, R.D.; Sun, M.; et al. Diffusion Imaging Reveals Sex Differences in the White Matter Following Sports-Related Concussion. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 4411–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, R.; Delevich, K.; Kirshenbaum, J.S.; Borchers, L.R.; Ho, T.C.; Gotlib, I.H. Sex differences in pubertal associations with fronto-accumbal white matter morphometry: Implications for understanding sensitivity to reward and punishment. NeuroImage 2021, 226, 117598–117598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsgodt, K.H.; John, M.; Ikuta, T.; Rigoard, P.; Peters, B.D.; Derosse, P.; Malhotra, A.K.; Szeszko, P.R. The accumbofrontal tract: Diffusion tensor imaging characterization and developmental change from childhood to adulthood. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36, 4954–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, E.P.; Harden, K.P.; Chein, J.M.; Steinberg, L. Sex Differences in the Developmental Trajectories of Impulse Control and Sensation-Seeking from Early Adolescence to Early Adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roediger, D.J.; Griffin, C.; Marin, F.V.; Verdoorn, H.; Fiecas, M.; A Mueller, B.; O Lim, K.; Camchong, J. Relating white matter microstructure in theoretically defined addiction networks to relapse in alcohol use disorder. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 9756–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, K.S.; Maleki, N.; Papadimitriou, G.; Makris, N.; Oscar-Berman, M.; Harris, G.J. Cerebral white matter sex dimorphism in alcoholism: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennatas, E.D.; Avants, B.B.; Wolf, D.H.; Satterthwaite, T.D.; Ruparel, K.; Ciric, R.; Hakonarson, H.; Gur, R.E.; Gur, R.C. Age-Related Effects and Sex Differences in Gray Matter Density, Volume, Mass, and Cortical Thickness from Childhood to Young Adulthood. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 5065–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotze, M.; Domin, M.; Gerlach, F.H.; Gaser, C.; Lueders, E.; Schmidt, C.O.; Neumann, N. Novel findings from 2,838 Adult Brains on Sex Differences in Gray Matter Brain Volume. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadalupe, T.; Mathias, S.R.; Vanerp, T.G.M.; Whelan, C.D.; Zwiers, M.P.; Abe, Y.; Abramovic, L.; Agartz, I.; Andreassen, O.A.; Arias-Vásquez, A.; et al. Human subcortical brain asymmetries in 15,847 people worldwide reveal effects of age and sex. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017, 11, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, F.; Schijven, D.; Heuvel, O.A.v.D.; Hoogman, M.; van Rooij, D.; Stein, D.J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Bölte, S.; Auzias, G.; Kushki, A.; et al. Large-scale analysis of structural brain asymmetries during neurodevelopment: Associations with age and sex in 4265 children and adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e26754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C.; Theofanopoulou, C.; Senior, C.; Cambra, M.R.; Usall, J.; Stephan-Otto, C.; Brébion, G. A large-scale study on the effects of sex on gray matter asymmetry. Anat. Embryol. 2018, 223, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchev, Z.; Gilboa, A.; Binns, M.; Colella, B.M.; Glazer, J.M.; Mikulis, D.J.M.; Green, R.E. Progressive Neurodegeneration Across Chronic Stages of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabilitation 2022, 37, E144–E156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, G.R.; D, J.F.D.; Verhelst, H.; Linden, C.V.; Deblaere, K.; Jones, D.K.; Cerin, E.; Vingerhoets, G.; Caeyenberghs, K. Network diffusion modeling predicts neurodegeneration in traumatic brain injury. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.R.; Meier, T.B.; Dodd, A.B.; Stephenson, D.D.; Robertson-Benta, C.R.; Ling, J.M.; Reddy, S.P.; Zotev, V.; Vakamudi, K.; Campbell, R.A.; et al. Prospective Study of Gray Matter Atrophy Following Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurology 2023, 100, e516–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida, A.F.; Massett, R.J.; Imms, P.; Vegesna, R.V.; Amgalan, A.; Irimia, A. Significant Acceleration of Regional Brain Aging and Atrophy After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Xu, Y.; Bi, H.-Y.; Xu, M.; Yang, Y. Developmental changes in brain activation and functional connectivity during Chinese handwriting. NeuroImage 2025, 317, 121330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risen, S.; Barber, A.; Mostofsky, S.; Suskauer, S. Altered functional connectivity in children with mild to moderate TBI relates to motor control. J. Pediatr. Rehabilitation Med. 2015, 8, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.A.; Salorio, C.F.; Barber, A.D.; Risen, S.R.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Suskauer, S.J. Preliminary findings of altered functional connectivity of the default mode network linked to functional outcomes one year after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2018, 21, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuerk, C.; Dégeilh, F.; Catroppa, C.; Dooley, J.J.; Kean, M.; Anderson, V.; Beauchamp, M.H. Altered resting-state functional connectivity within the developing social brain after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Nowikow, C.; DeMatteo, C.; Noseworthy, M.D.; Timmons, B.W. Sex-specific differences in resting-state functional brain activity in pediatric concussion. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muetzel, R.L. , et al. Resting-state networks in 6-to-10 year old children. Hum Brain Mapp 2016, 37, 4286–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, T.D.; Wolf, D.H.; Roalf, D.R.; Ruparel, K.; Erus, G.; Vandekar, S.; Gennatas, E.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Smith, A.; Hakonarson, H.; et al. Linked Sex Differences in Cognition and Functional Connectivity in Youth. Cereb. Cortex 2015, 25, 2383–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supekar, K.; Musen, M.; Menon, V. Development of Large-Scale Functional Brain Networks in Children. PLOS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.T.; Hanten, G.R.; Li, X.; Orsten, K.D.; Levin, H.S. Emotion recognition following pediatric traumatic brain injury: Longitudinal analysis of emotional prosody and facial emotion recognition. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 2869–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agcaoglu, O.; Muetzel, R.L.; Rashid, B.; White, T.; Tiemeier, H.; Calhoun, V.D. Lateralization of Resting-State Networks in Children: Association with Age, Sex, Handedness, Intelligence Quotient, and Behavior. Brain Connect. 2022, 12, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Pang, G. Identification of Brain Regions with Enhanced Functional Connectivity with the Cerebellum Region in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.M.; Wild, J.T.; Burgess, J.K.; McCracken, K.; Malekian, S.; Turner, J.A.; King, K.; Kwon, S.; Carl, R.L.; LaBella, C.R. Assessment of post-concussion emotional symptom load using PCSS and PROMIS instruments in pediatric patients. Physician Sportsmed. 2024, 52, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigon, A.; Duff, M.C.; McAuley, E.; Kramer, A.F.; Voss, M.W. Is Traumatic Brain Injury Associated with Reduced Inter-Hemispheric Functional Connectivity? A Study of Large-Scale Resting State Networks following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumskaya, E.; van Gerven, M.A.J.; Norris, D.G.; Vos, P.E.; Kessels, R.P.C. Abnormal connectivity in the sensorimotor network predicts attention deficits in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlkeld, Z.D.; Bodien, Y.G.; Rosenthal, E.S.; Giacino, J.T.; Nieto-Castanon, A.; Wu, O.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Edlow, B.L. Functional networks reemerge during recovery of consciousness after acute severe traumatic brain injury. Cortex 2018, 106, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.A.; Salorio, C.E.; Gomes, J.P.; Nebel, M.B.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Suskauer, S.J. Response Inhibition Deficits and Altered Motor Network Connectivity in the Chronic Phase of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 3117–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, L.; Cao, J.; Huang, W.; Sun, C.; Zheng, D.; Wang, Z.; Gan, S.; Niu, X.; Gu, C.; et al. Sex Differences in Abnormal Intrinsic Functional Connectivity After Acute Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neural Circuits 2018, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniapillai, S. , et al. Age- and Episodic Memory-related Differences in Task-based Functional Connectivity in Women and Men. J Cogn Neurosci 2022, 34, 1500–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniapillai, S.; Rajagopal, S.; Elshiekh, A.; Pasvanis, S.; Ankudowich, E.; Rajah, M.N. Sex Differences in the Neural Correlates of Spatial Context Memory Decline in Healthy Aging. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 31, 1895–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Halperin, J.M.; Li, X. Abnormal Functional Network Topology and Its Dynamics during Sustained Attention Processing Significantly Implicate Post-TBI Attention Deficits in Children. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, D.R.; West, J.D.; Bailey, J.N.; Arnold, T.W.; Kersey, P.A.; Saykin, A.J.; McDonald, B.C. Increased brain activation during working memory processing after pediatric mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 8, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.Y.; Di, X.; Yu, X.; Biswal, B.B. The significance and limited influence of cerebrovascular reactivity on age and sex effects in task- and resting-state brain activity. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrushko, J.W.; Rinat, S.; Kirby, E.D.; Dahlby, J.; Ekstrand, C.; Boyd, L.A. Females exhibit smaller volumes of brain activation and lower inter-subject variability during motor tasks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narad, M.E.; Riemersma, J.; Wade, S.L.; Smith-Paine, J.; Morrison, P.; Taylor, H.G.; Yeates, K.O.; Kurowski, B.G. Impact of Secondary ADHD on Long-Term Outcomes After Early Childhood Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2020, 35, E271–E279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fur, C.; Câmara-Costa, H.; Francillette, L.; Opatowski, M.; Toure, H.; Brugel, D.; Laurent-Vannier, A.; Meyer, P.; Watier, L.; Dellatolas, G.; et al. Executive functions and attention 7 years after severe childhood traumatic brain injury: Results of the Traumatisme Grave de l’Enfant (TGE) cohort. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 63, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wu, K.; Halperin, J.M.; Li, X. Abnormal structural and functional network topological properties associated with left prefrontal, parietal, and occipital cortices significantly predict childhood TBI-related attention deficits: A semi-supervised deep learning study. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1128646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzer, S.; Rocca, M.A.; Molteni, E.; De Meo, E.; Recla, M.; Valsasina, P.; Arrigoni, F.; Galbiati, S.; Bardoni, A.; Filippi, M. Altered Recruitment of the Attention Network Is Associated with Disability and Cognitive Impairment in Pediatric Patients with Acquired Brain Injury. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manelis, A.; Santos, J.P.L.; Suss, S.J.; Holland, C.L.; Perry, C.A.; Hickey, R.W.; Collins, M.W.; Kontos, A.P.; Versace, A. Working Memory Recovery in Adolescents with Concussion: Longitudinal fMRI Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlustos, S.J.; Chiu, C.P.; Walz, N.C.; Wade, S.L. Neural substrates of inhibitory and emotional processing in adolescents with traumatic brain injury. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 8, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).