Introduction

The Internet has emerged as a pivotal resource for individuals seeking to manage their healthcare needs, mainly due to a rapid shift from in-person consultations to online healthcare access [

1,

2,

3]. Websites often serve as the initial point of contact for users learning about a medical center's resources, and health information on these websites usually informs patients about the care they seek [

4,

5]. These websites have key features that make them more accessible to users, such as speed, readability, content quality, and website infrastructure [

6], encouraging people to turn to these resources for medical information.

Website Usability:

With the growing trend of people seeking health information online [

7,

8], it has become crucial that hospital websites are prioritized as trustworthy sources of health information, further emphasizing the importance of ensuring that they are easy to use and navigate. Different industries have developed standardized guidelines for accessibility, content, marketing, and technology to enhance website usability [

9]. Usability refers to the degree to which a system or interface allows users to achieve their goals with minimal effort, time, and frustration. In general, usability is evaluated using various metrics, including ease of navigation, accessibility, and the effectiveness of content presentation. These metrics are particularly important in healthcare websites, as they impact how easily patients, caregivers, and other users can find critical health information, navigate complex health data, and make informed decisions. For healthcare websites, usability metrics also include readability scores, which assess how easy it is for users to understand written content, and accessibility measures that ensure the website is usable by individuals with diverse needs, such as those with visual impairments. These metrics are especially critical in healthcare, where accessibility to accurate and understandable information can directly affect patient outcomes. Furthermore, healthcare websites must balance various objectives, such as delivering accurate medical information, complying with regulations, and maintaining a user-friendly interface. Various studies have adapted and applied preexisting usability scoring methodologies to assess the accessibility, content quality, marketing, and technology of websites from US academic medical centers [

10,

11], military residency programs [

12], emergency medicine residency programs [

13], and anesthesiology residency programs [

14]. This research proved valuable in informing hospitals on areas of improvement for their websites. However, this methodology could be used on more data to summarize critical information from the vast amount of data available on the Internet.

Need for Automation:

Automating the scoring process gives greater scope for increased efficiency and will deliver quicker feedback to medical centers on improving their websites. Language models can automatically summarize and automate manual reviews of website quality [

15]. Studies have shown that AI can significantly enhance the accessibility and readability of complex health information, making it easier for patients to grasp essential health details [

16,

17]. This underscores the potential of AI to automate content improvements on healthcare websites, which could lead to better patient engagement and outcomes. AI's ability to analyze sentiment and assess readability also supports its use in measuring content ease of use. Users, particularly in academic and professional settings, often face challenges in quickly locating precise information amidst overwhelming content. Studies have highlighted the necessity for improved methods to manage and condense online information, particularly for obtaining details such as dates, program specifics, and procedural guidelines. For instance, Van Veen et al. (2024) discuss the complexities of summarizing clinical texts due to computational and memory constraints, highlighting the potential of adapted large language models to emphasize the need for more efficient summarization techniques to manage extensive medical information. [

18]. Similarly, Andhale and Bewoor (2018) review various text summarization techniques, underscoring the ongoing challenges in creating effective and efficient summarization tools [

19]. These gaps highlight the importance of developing a web-based application that leverages generative AI to address these needs.

Objective:

There is significant literature on manually assessing website accessibility [

20]. However, this process is very time-consuming. For example, Sun et al. discussed the challenges involved in selecting appropriate tools and manually developing methods for evaluating the accessibility of e-textbooks, a task that requires significant time and expertise [

21]. Despite the growing role of healthcare websites in providing information to patients and the public, there is still no comprehensive, automated framework to evaluate their usability and accessibility. This highlights the need for automation. For instance, Mateus et al. compared manual inspections, automated tests, and user evaluations, showing the limitations of manual assessments [

22]. Similarly, Casado Martínez et al. examined the link between manual and automated web accessibility assessments, emphasizing that while manual methods are common, they would benefit from automation [

23]. This research aims to leverage the potential of AI and generative AI to extract data from medical center websites, offering hospitals insight into their websites' usability and content quality. The study tries to automate an established usability scoring methodology for healthcare websites to improve efficiency and accuracy. It sought to apply and evaluate this automated approach on a sample of Emergency medicine fellowship websites. We chose this subset of Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites because they provide a robust and diverse sample to test our methodology. This selection allowed us to demonstrate the application of automated usability analysis across various website domains with different design and content structures. While the focus was on fellowship websites, the methodology is intentionally broad and generalizable, making it applicable to other domains within healthcare. This ensures that the insights gained from this study can be translated to similar usability assessments in different contexts. The study also intends to analyze the results to provide actionable recommendations for enhancing these websites' usability and overall user experience, offering practical insights for improvements.

Results

The findings of the website usability analysis are displayed in the tables below, including the mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error, minimum, and maximum values for each examined aspect: accessibility, marketing (SEO), headers, paragraphs, and multimedia.

This dataset also gives each website a unique identifier known as the “Website Index” to improve the organization and management of the data. This is important to maintain data accuracy, since it ensures that no duplicate entries are recorded and that every entry can easily be found. Zero-based indexing, which means that the series begins with ‘0’, is very useful in data analysis as it adheres to the standard of many statistical software and programming languages. This technology enhances data retrieval and manipulation, thus making it easy to incorporate this dataset with others and perform accurate and precise comparisons and analyses.

The usability metrics for Selected Websites

Table 1 presents the usability data for a specific group of websites. Metrics, including Accessibility, Marketing, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia components are measured. The values indicate particular cases of website analysis, illustrating the heterogeneity across various sites. The Accessibility ratings exhibit significant variability, indicating differing degrees of readability and user-friendliness among websites.

Table 2 presents an overview of website usability data, emphasizing the mean, standard deviation, lowest, and maximum values for each usability indicator across 100 websites. The mean values are an average performance metric for each category, while the standard deviation underscores diversity. The range (minimum and maximum) highlights the extremes in performance, demonstrating websites with deficient or exceptional usability qualities.

The usability metrics presented in the dataset include a range of measures that offer a detailed analysis of the website’s performance. The scores are divided into five categories, namely Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia. For example, the first website in the dataset indexed as 0 has an Accessibility score of 76.49, which means that the website is fairly easy to use and read. On the other hand, its Marketing score is relatively low at 0.62, which means that there is room for improvement in terms of SEO strategies. Similarly, the scores for Headings and Paragraphs at 16.81 and 6.49, respectively, show that the content is well organized and not very shallow. This indicates that the website does not have multimedia elements, which is also demonstrated by the score of 0; this is another area that should be given attention to improve user experience through interaction. Consequently, these metrics provide a detailed comparison of each website’s usability, giving the necessary insights for precise improvements and overall assessment within the context of the given dataset.

Table 2.

Statistical Summary of the Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program website's usability metrics like Accessibility, Marketing, Headers, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, showing each metric's count, mean, standard deviation (Std Dev) and interquartile range. The study aimed to evaluate user-centered design and content quality for prospective applicants. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024..

Table 2.

Statistical Summary of the Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program website's usability metrics like Accessibility, Marketing, Headers, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, showing each metric's count, mean, standard deviation (Std Dev) and interquartile range. The study aimed to evaluate user-centered design and content quality for prospective applicants. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024..

| Statistic |

Accessibility |

Marketing |

Headings |

Paragraphs |

Multimedia |

| Count |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Mean |

44.53 |

13.1 |

14.16 |

26.44 |

8.11 |

| Std Dev |

48.05 |

7.83 |

11.25 |

17.47 |

7.14 |

| Min |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 25% |

17.58 |

5.96 |

4.53 |

11.93 |

0.93 |

| 50% |

43.02 |

13.77 |

13.65 |

24.76 |

7.3 |

| 75% |

71.62 |

17.75 |

21.01 |

37.94 |

12.97 |

| Max |

149.24 |

29 |

52 |

69.25 |

26 |

Analysis of Variability and Outliers

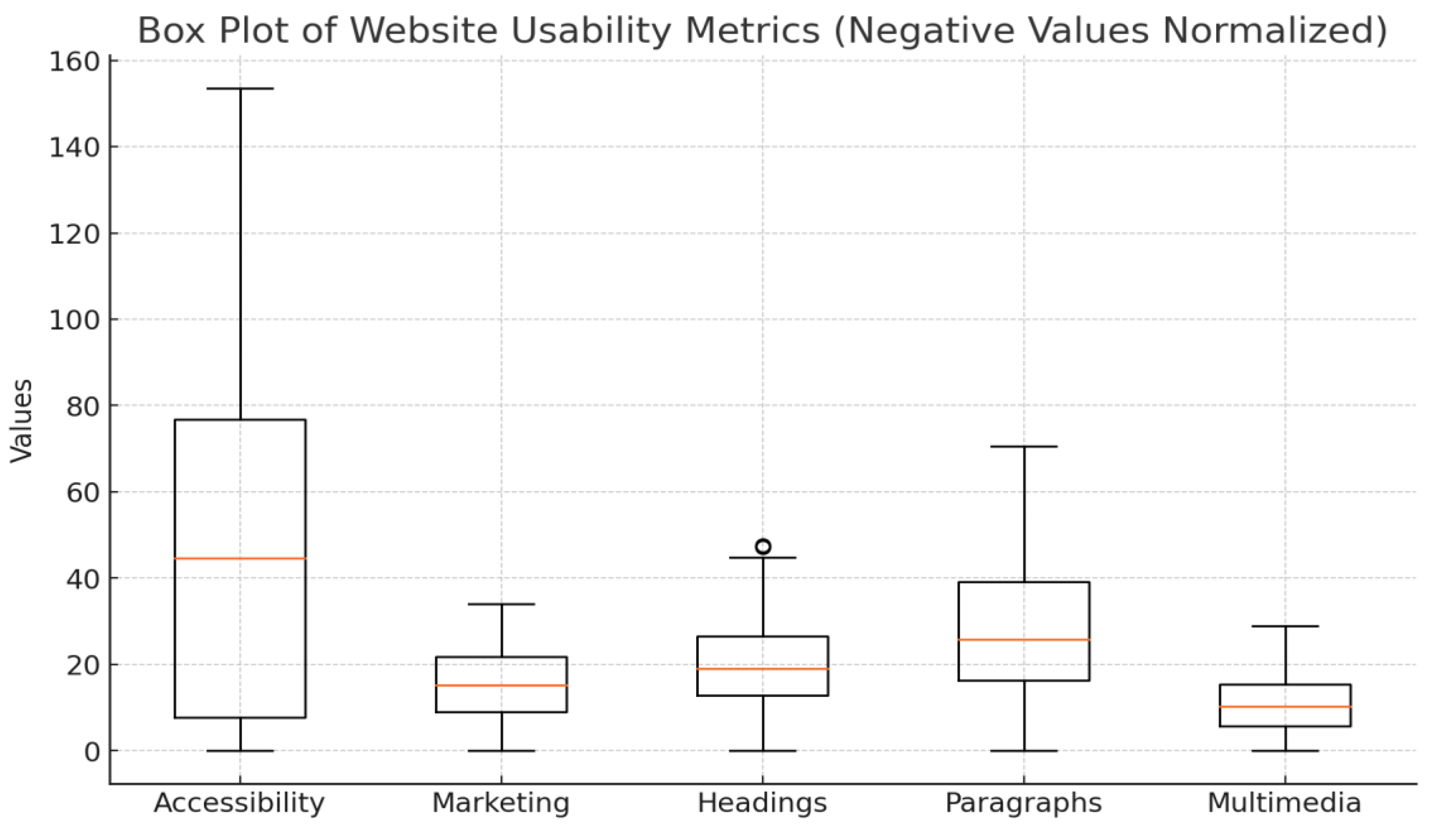

The box plot in

Figure 1 illustrates the dispersion and presence of values in the dataset, providing a visual representation of the usability metrics distribution. The visualization is essential for comprehending the dissemination and extremes of the data, specifically in measures such as accessibility and content quality.

The accessibility ratings demonstrate significant diversity and numerous extreme values, ranging from 0 to 206.84. This implies that certain websites exhibit remarkable readability, while others may present difficulties for visitors, potentially affecting their accessibility. The values suggest that certain websites may include content that is highly challenging to comprehend.

Outliers and broad interquartile ranges in the number of headings and paragraphs indicate inconsistent content organization across the websites. Websites with fewer headings and paragraphs may have less detailed content. In contrast, websites with a more significant number of headings and paragraphs may provide more extensive information.

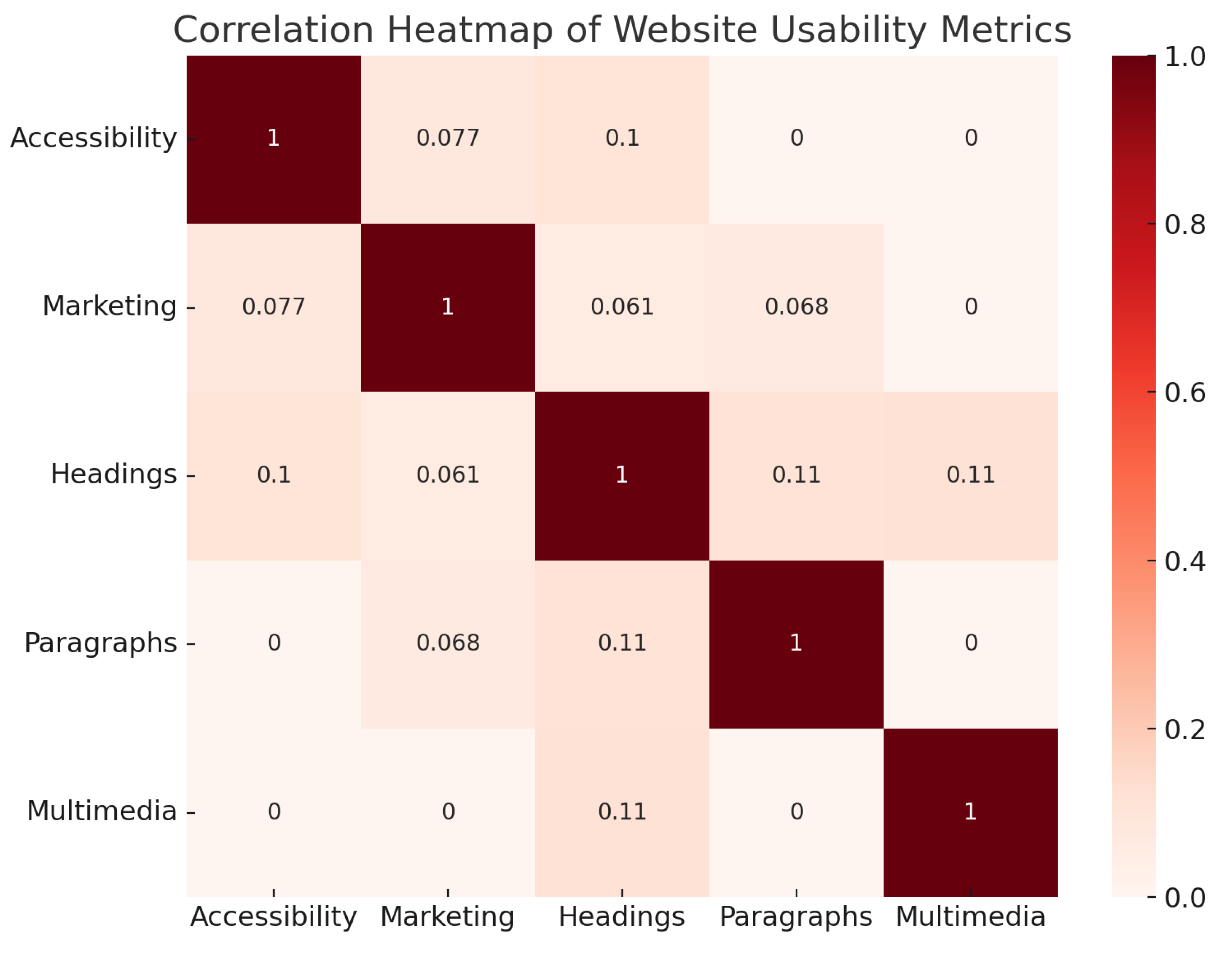

Correlation Analysis

Figure 2 displays a correlation heatmap of the usability metrics, illustrating the connections between various components of website usability. It is worth mentioning that Accessibility is inversely related to other measures, such as Marketing (SEO) and content elements (Headings and Paragraphs). These findings indicate that websites prioritizing search engine optimization and having substantial information may not always be the most user-friendly.

Positive correlations across content quality indicators, such as Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, suggest that websites with a high quantity or quality of one type of content also tend to have a high amount or quality of other types of material. For instance, websites with many Headings typically include many Paragraphs and Multimedia elements, indicating a thorough presentation approach.

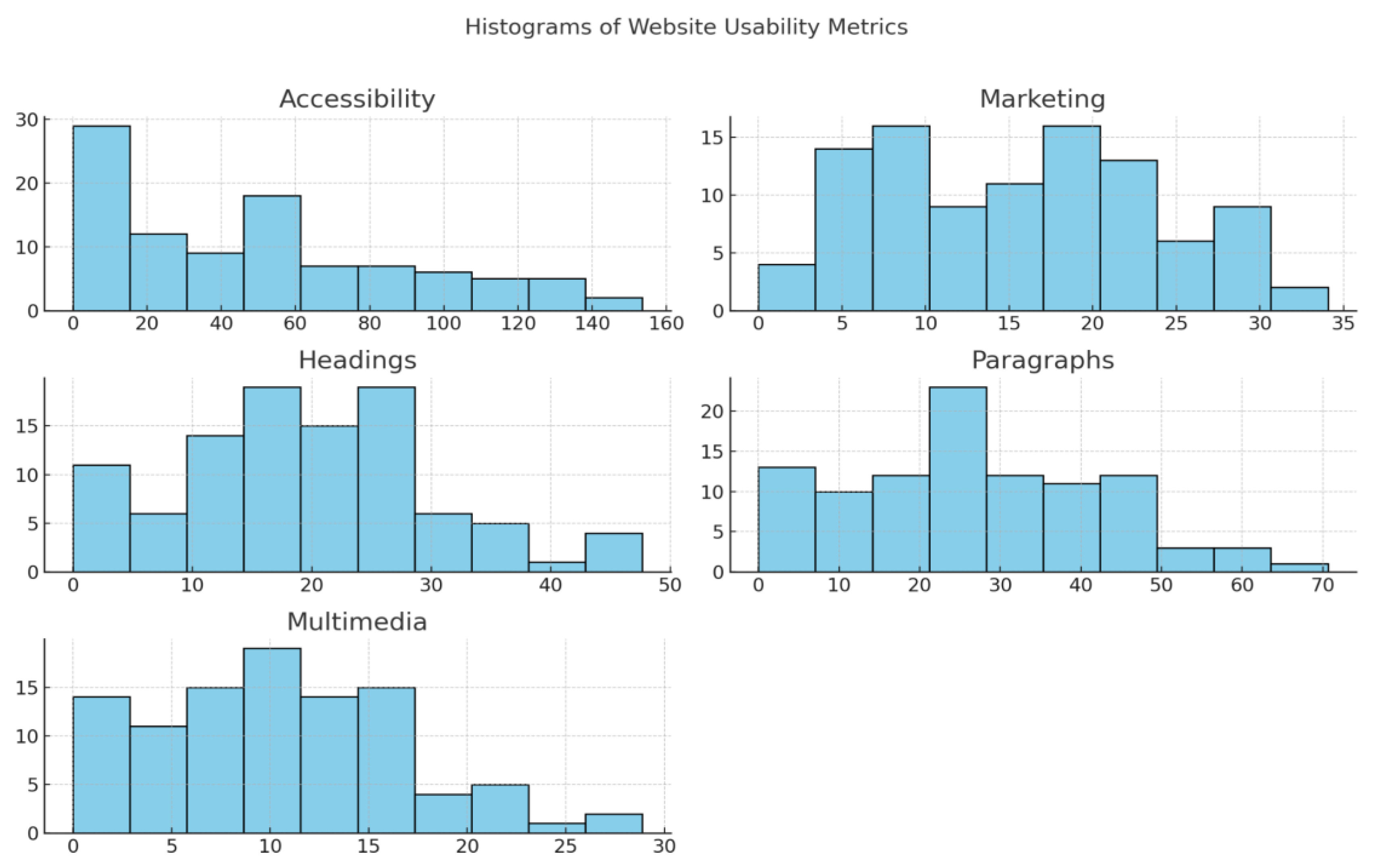

Distribution Patterns

The histograms shown in

Figure 3 illustrate the distribution patterns of each usability indicator, providing a deeper comprehension of the measures of central tendency and extent of variability. An analysis was conducted on these distributions to ascertain whether most websites effectively cater to clients or if notable anomalies impacted overall usability. This study facilitates the identification of specific areas where web designers and developers should concentrate their efforts to enhance user experience comprehensively. For example, the histogram depicting Accessibility exhibits a positive skewed distribution, where a number of websites obtained a score of approximately 50, suggesting a satisfactory degree of readability for many sites.. The results indicate that although a big proportion of websites provide sufficient Accessibility, there is still a notable disparity in performance, with specific sites demonstrating exceptional performance and others falling far behind. The observed heterogeneity underscores the necessity for focused enhancements in web accessibility protocols, especially for websites that fall toward the lower end of the range.

The histograms depicting Headings, Paragraphs and Multimedia exhibit an asymmetry of the probability distribution about the mean, with the majority of website usability being concentrated within the lower range, and to a lesser extent on the upper range. This pattern indicates that while several websites conform to established patterns, a few surpass expectations or significantly underperform.

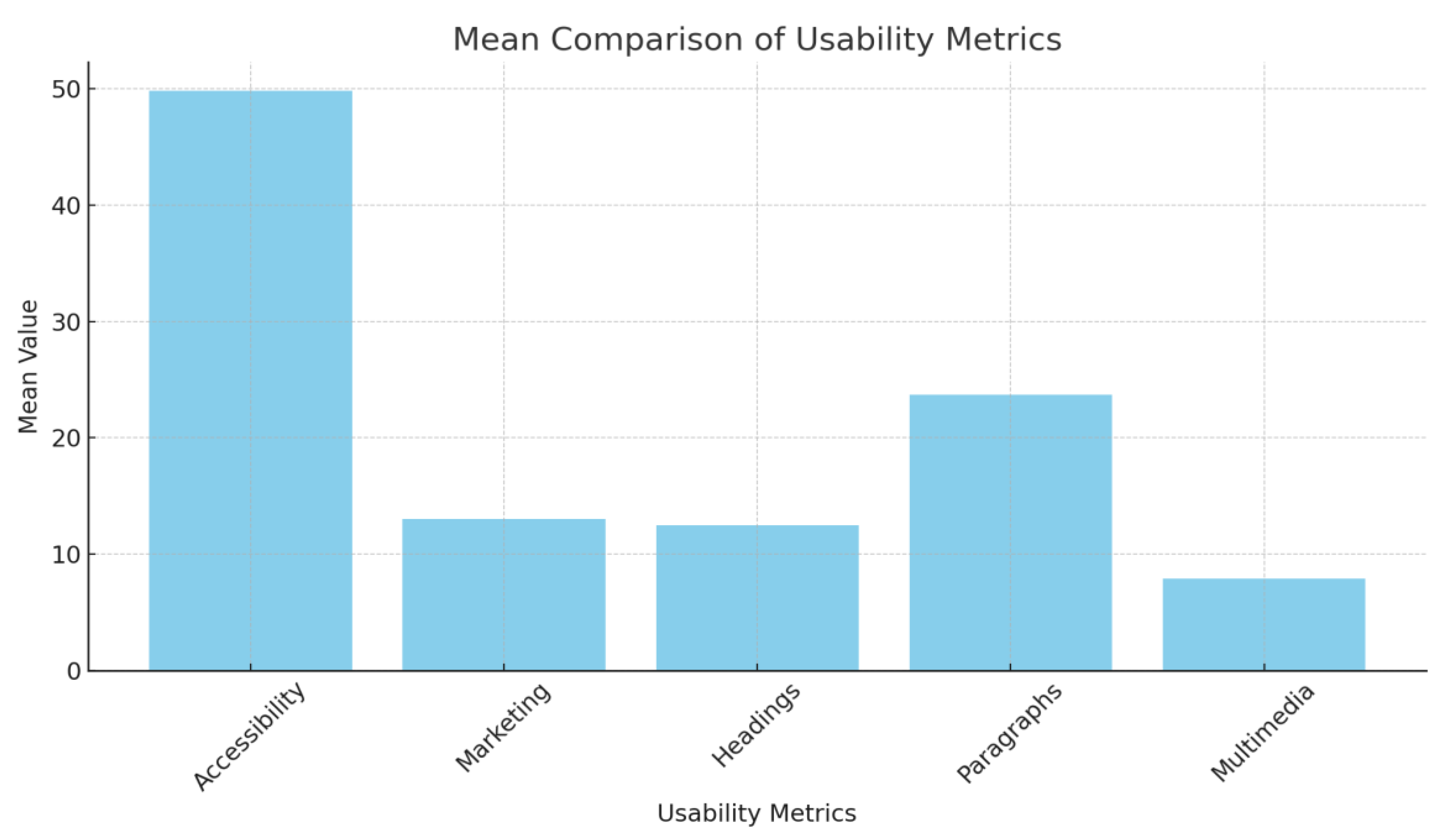

Comparative Overview

Figure 4 displays the average values of the usability metrics, offering a comparative summary. The mean value of Accessibility is the highest, indicating a moderate level of readability across the websites. Conversely, the average values for Marketing and Multimedia components are lower, suggesting that some websites may not be thoroughly optimized for SEO or abundant in multimedia material.

Relationship and Distributions

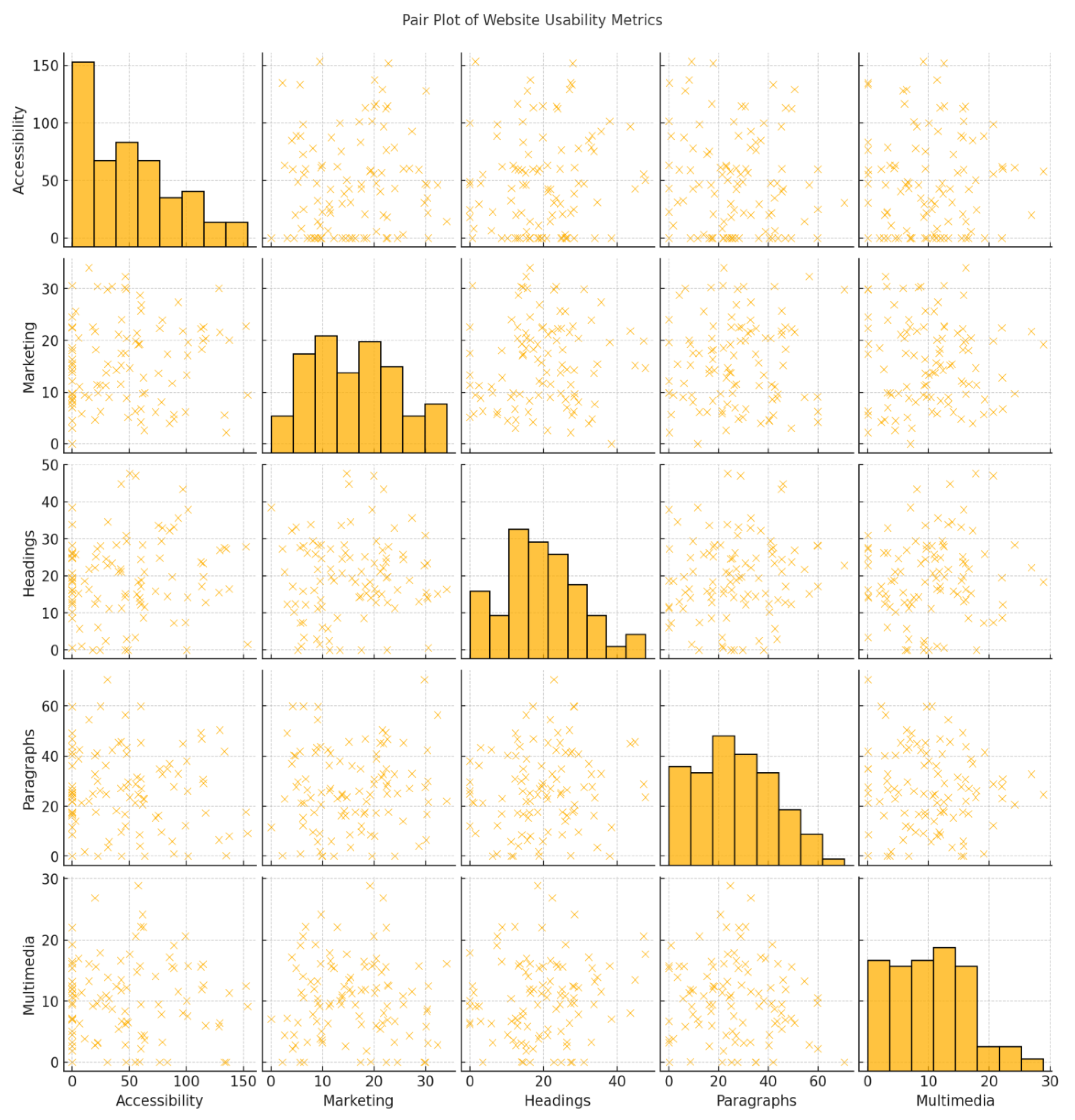

The pair plot depicted in

Figure 5 thoroughly visualizes the interrelationships and distributions of pairs of metrics, allowing insights into how various usability aspects interact. The scatter plots correlate with higher SEO scores and more headings and paragraphs. However, this relationship is inconsistent, suggesting that websites vary in balancing content richness and SEO optimization.

Analysis and Conversation

The analysis demonstrates significant diversity in the usability indices among the websites. The considerable disparities in standard deviations and extensive ranges seen in accessibility, SEO optimization, content structure, and multimedia utilization indicate a substantial variation in website usability throughout the sample.

Accessibility

The range of readability scores highlights the necessity for several websites to enhance their material to ensure it is more accessible to a broader audience, particularly considering users with varying reading abilities. Consistent readability is important, as indicated by the outliers and distribution patterns. Accessibility scores exhibited significant heterogeneity, with a mean of 49.83 (SD = 53.67, SE = 8.94), underscoring considerable differences among websites. Scores varied from 0 to 206.84, with values signifying substantial usability impediments, like inadequate readability or exclusive design features. This broad disparity highlights the necessity for focused actions to close the divide between easily accessible and inaccessible websites. The elevated standard deviation indicates that while several websites excel in accessibility, others are considerably behind, highlighting an urgent necessity for standardization in accessibility standards.

Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

The disparities in SEO methodologies underscore a deficiency several websites must rectify to optimize their visibility and expand their audience. The correlation research demonstrates that although SEO optimization and rich content might exist together, they do not ensure accessibility. This implies that well-balanced optimization tactics are required. The marketing performance, evaluated using SEO scores, exhibited a mean of 13.03 (SD = 8.77, SE = 1.46). The numbers, spanning from 0.0 to 29.00, indicate that numerous websites demonstrate typical optimization levels, with a limited number of outliers at the extremes. A comparatively lower standard deviation to accessibility signifies more uniform performance among websites; nonetheless, the overall low mean suggests a minimal focus on SEO strategies. This research indicates that numerous websites prioritize various facets of usability over discoverability, potentially affecting their reach and visibility.

Content Quality

Variations in the number of headings and paragraphs indicate that certain websites offer organized and comprehensive content. In contrast, others lack these qualities, which might impact the user's experience and level of involvement. Likewise, the diverse utilization of multimedia suggests that not all websites are capitalizing on these features to augment the depth of their material.

The average number of paragraphs per webpage was 23.72 (SD = 20.79, SE = 3.47), ranging from 0.0 to 82.00. This metric exhibited significant diversity, suggesting that certain websites present comprehensive, content-dense pages while others give scant textual material. The extensive range and elevated standard deviation indicate discrepancies in the prioritization of content depth, potentially affecting user engagement and knowledge retention. Standardizing material length and depth may improve usability and informational quality.

The mean usage of multimedia, including images, videos, and interactive features, was 7.89 (SD = 7.80, SE = 1.30). Scores varied from 0.0 to 26.00, exhibiting a more restricted spread than headings or paragraphs. Some websites utilize multimedia efficiently, while others disregard it, leading to inconsistent engagement potential. The comparatively lower average indicates a prevailing tendency to underutilize graphic and interactive material, representing a potentially wasted opportunity to improve user experience and engagement.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop and test an automated way to measure how easy it is to use healthcare websites, focusing on Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. The automated methodology successfully evaluated multiple dimensions of usability including Accessibility, SEO (Marketing), content structure (Headings and Paragraphs), and Multimedia use, highlighting substantial variability across websites. The findings revealed wide disparities, particularly in accessibility scores and content organization, indicating that while some websites offer strong user-centered design and readability, many lack standardized features necessary for optimal user experience. The correlation and distribution analyses further demonstrated that high SEO or content volume did not always equate to better accessibility, underscoring the complexity of balancing content richness with usability. These results support the study’s central hypothesis that an automated approach can expeditiously identify strengths and weaknesses in website design. It also supports the idea that such analytical tools like this could be used more widely to help healthcare websites improve and better serve their users.

Our findings of the website usability analysis indicate considerable variety in critical domains, including Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), content organization, and Multimedia use. This variability highlights the intricate nature of website design, where trade-offs among many usability elements are apparent. Accessibility was one of the most varied metrics, with scores ranging from 0 to 206.84. This shows a difference in how easy it is to use the websites. The Accessibility scores highlight key barriers that may hinder users, especially those relying on assistive technologies. These low scores could be due to complex medical language, poor contrast ratios, or lack of proper navigation support This underscores the need for a more consistent approach to web accessibility. Such obstacles can make it difficult for individuals with visual impairments or cognitive challenges to access important health information. Future studies should investigate these factors in detail and explore solutions, such as simplifying medical content, improving website design, and enhancing compatibility with screen readers.

SEO performance also showed some variability, with an average score of 13.03 and a standard deviation of 8.77. While scores ranged from 0 to 29, it’s clear that many websites are not doing enough to optimize their content for search engines. Poor SEO can limit a website’s visibility and reach. Interestingly, websites that focused on content often missed optimizing their SEO, affecting how well their pages perform in search rankings. With SEO being crucial for driving traffic, websites should adopt a balanced approach. This includes using relevant keywords, improving metadata, strengthening internal links, and ensuring fast load times and mobile-friendly design. An important finding of this study is the inverse correlation between accessibility and SEO performance. This suggests that optimizing a website for search engines may sometimes compromise its accessibility features or vice versa. For healthcare websites, this trade-off presents a significant challenge. On one hand, websites optimized for SEO are more likely to attract traffic and be easily found by users. Features aimed at improving accessibility, such as simplified navigation or additional alt-text for images, may not always align with SEO strategies, potentially making it harder for search engines to rank the page highly. This issue is further amplified by the role websites play in training AI and machine learning models, which rely on online content to generate medically relevant responses. If healthcare websites strike the right balance between SEO and accessibility, they contribute to the availability of well-structured, accurate medical information to the LLMs. Optimized websites help ensure that AI-generated responses align with medically accurate terminology, ultimately improving the quality of health information provided by AI-driven tools. Therefore, healthcare website designers must prioritize both accessibility and SEO, not only to enhance user experience but also to support the integrity of AI-driven medical information.

Furthermore, the inconsistency noted in content quality, especially regarding headings, paragraphs, and multimedia, indicates that content presentation significantly influences user engagement with the website. The positive association among these content elements suggests that websites abundant in one content type are likely to be extensive in others. The number of headings and paragraphs varied greatly across the websites, with an average of 23.72 paragraphs per page. This difference suggests that some websites provide detailed, well-structured content, while others offer less comprehensive information. Websites with more headings and paragraphs tend to present organized, easy-to-understand content that enhances user experience. On the other hand, websites with fewer headings and paragraphs may feel disorganized, making it harder for users to navigate or understand complex topics. To improve content quality, websites should focus on structuring content clearly with well-defined headings, appropriate paragraph breaks, and consistent formatting. The use of multimedia (like images, videos, and interactive content) was generally low across the websites, with an average score of 7.89. Scores ranged from 0 to 26, indicating some websites use multimedia effectively, while others don’t use it much at all. Multimedia can make websites more engaging and help explain complicated information. However, many websites miss out on this opportunity, which could impact user satisfaction. Websites should prioritize adding images, videos, and interactive elements to make the content more appealing and engaging. Additionally, these multimedia elements should be optimized for fast loading and work well on all devices, including mobile phones. As the digital world progresses, web designers and developers must prioritize creating balanced, accessible, and content-rich websites to meet customer expectations thoroughly.

Looking at the distributions of the usability metrics, especially Accessibility, we saw some interesting patterns. Many websites scored around 50 for Accessibility, but there were also outliers at both ends. This shows that while most websites perform reasonably well in terms of accessibility, some do exceptionally well or very poorly. Similarly, for SEO, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia usage, the scores were more evenly spread, but we still saw outliers in a positively skewed distribution, with some websites going above and beyond in terms of content and multimedia, while others fell behind. In conclusion, the analysis shows that websites vary widely in terms of usability. Improving accessibility, SEO, content quality, and multimedia usage can significantly enhance the user experience.

Previous literature has looked at different aspects of website usability, especially for healthcare websites. Usability measures, like readability and accessibility, have been a key part of these evaluations. For example, Lee and Kozar (2012) stressed the importance of defining and measuring website usability elements [

25], pointing out that understanding how these factors are connected can provide better insights into the overall user experience. In healthcare, Saad et al. (2022) analyzed healthcare website usability features, identifying problems like poor navigation, lack of mobile responsiveness, and accessibility issues [

26]. They also found that content often didn't match user needs, particularly with complex language and unclear information. They used testing methods like usability testing, heuristic evaluations, and accessibility audits to assess these issues, showing how important these aspects are for improving user experience in healthcare. Similarly, Ownby and Czaja (2003) focused on the elderly and identified challenges like small fonts, poor color contrast, and hard-to-use navigation that can make healthcare websites difficult for older users [

27]. They suggested improving website clarity and using assistive technologies to improve accessibility. In addition, Usman et al. (2017) conducted a systematic review on how healthcare websites are evaluated for usability [

28]. They found that expert reviews, user testing, and surveys are commonly used but emphasized the need for more user-centered approaches in website design for healthcare. The strength of our study is that we used an automated approach to evaluate several important usability features concurrently, rather than focusing on preferred singular areas ultimately reducing bias, while enhancing analytical power. Unlike earlier studies that relied mostly on manual methods or targeted specific user groups, our method provided a broader and quicker assessment across key domains like accessibility, SEO, content organization, and multimedia use. For example, we found an inverse relationship between accessibility and SEO, something that hasn't been deeply explored in past studies. This highlights a new challenge in designing healthcare websites: making sure they are both user-friendly and readily accessible online. This study examines Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites, employing a versatile and replicable methodology. Its broad and adaptable design allows for application across other healthcare domains. Consequently, the findings from this analysis can inform similar usability evaluations in diverse settings, enhancing its applicability beyond the initial scope.

Limitation:

The study has several limitations. The data collection occurred at a specific time (March, 2024), and websites frequently update content, SEO practices, and design. This time-specific snapshot may not accurately reflect ongoing or future improvements in website usability, highlighting the need for continuous evaluation and improvement.

This study heavily relies on automated tools and AI models for website usability assessment. However, it is of importance to note that AI tools, such as GPT-3.5-turbo, used for grammar and content quality analysis, may introduce biases or inaccuracies in evaluating complex medical terminology. For instance, these tools may not fully understand complex medical terms or the specific language used in patient materials. Additionally, these tools don't consider with what accuracy complex medical information is explained for use by the general public, which is important for making the content accessible and understandable. This method should be viewed primarily as a preliminary example framework rather than a definitive solution. Future studies should refine and expand upon these approaches to enhance their accuracy and applicability, especially when analyzing highly specialized medical content. Therefore, the potential impact of these tools on the accuracy of the evaluation should be carefully considered.

The study's accessibility assessment relies mainly on readability scores, which measure text complexity, but do not account for other accessibility issues, such as compatibility with screen readers, keyboard navigation, or visual design adjustments for color blindness. This limitation may result in an incomplete evaluation of website accessibility. Future research should include these factors and user testing with individuals who rely on assistive technologies to provide a more complete evaluation of accessibility.

Conclusion:

The analysis of Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites underscores the importance of usability, accessibility, and content quality in ensuring these sites effectively serve prospective applicants. Our findings reveal variability in website design, readability, SEO, and accessibility metrics, highlighting the need for standardized, user-centered website development across medical fellowship programs.

Despite limitations in scope and methodology, this study demonstrates that websites with high usability scores are better positioned to engage users and convey critical information. Sites optimized for readability and accessibility improve the applicant experience and expand access to a broader, more diverse audience. For example, by doing so, programs can attract a more diverse pool of applicants and foster transparency. These improvements also support broader goals in medical education by promoting inclusion and strengthening digital communication standards. Future efforts should emphasize integrating user feedback, refining accessibility features, and employing more dynamic SEO strategies to enhance the digital presence of fellowship programs.

Overall, prioritizing these factors can enhance communication, improve outreach, and support informed decision-making practices among applicants, ultimately contributing to a more effective recruitment process for Global Emergency Medicine Fellowships.

Methodology

Data Collection

For this study, the dataset was manually compiled by collecting URLs from institutions offering Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship programs. These URLs were sourced from the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) website, specifically from the GEM Fellowship Programs page. The data collection process occurred in March, 2024 and involved systematically navigating the list of fellowship programs on the SAEM website (

Table A1)

Each institution's fellowship program URL and relevant metadata such as program name, institution, and contact details were manually gathered and accumulated into a CSV file. We chose these websites because Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship programs represent a critical area of medical education where accessible and high-quality information is essential for healthcare professionals making important career decisions. Furthermore, various institutions offer these programs with varying website designs and structures, making them ideal for testing our automated website usability scoring methodology [

24]. The public accessibility of these URLs and their real-world impact on the decision-making process of prospective fellows made this dataset a fitting choice for our study. By analyzing these websites, we aim to offer actionable insights that can improve their usability and, in turn, enhance user experience for future fellowship applicants.

Scoring and Data Generation Process

The automated process is employed to assess the websites' usability in our dataset. The analysis centers on four key aspects: accessibility, marketing (SEO), content quality, and technology. The review method is completely automated, reducing the need for human interaction in quality assessment by utilizing several tools including the Large Language Model model (OpenAI's GPT-3.5-turbo), Python libraries Pandas, Requests, BeautifulSoup, and Textstat. The Requests library sent HTTP requests to each website URL to retrieve and parse the webpage content. The BeautifulSoup library subsequently processed the HTML content of the web pages. By parsing the HTML structure, we were able to retrieve pertinent information that was required for later investigation.

Scoring Metrics

Each usability metric Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia was assessed using a defined scoring system to evaluate distinct facets of website performance. The scoring system for each criterion is detailed.

Accessibility Analysis

Accessibility: Scores were calculated based on compliance with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1). Significant factors were assessed, including contrast ratios, text legibility, and navigational simplicity. Low scores suggest significant accessibility obstacles, while positive scores signify substantial compliance. This score measures the readability of the text on the webpage, a vital aspect of accessibility. The analysis entailed collecting all textual content from the web page's paragraphs and calculating the readability score.

Marketing (SEO) Analysis

Websites were evaluated according to search engine optimization criteria, encompassing meta tag utilization, keyword incorporation, page loading speeds, and mobile compatibility. Google Lighthouse and SEMrush were used to obtain SEO-related data, with scores varying from 0 (suboptimal optimization) to 30 (optimal). Meta tags have a crucial impact on SEO, and their existence reflects the degree of focus dedicated to optimizing the webpage for search engines.

Content Quality Analysis

The assessment of content quality involved the examination of multiple factors:

The homepage was analyzed to determine the number of headers (h1, h2, h3) and paragraphs present. This provided a deeper understanding of the content's arrangement and structure.

OpenAI's GPT-3.5-turbo LLM model was used to detect grammatical errors in the text collected from the webpage. The material contained both titles and blocks of text. The study entailed inputting the text into the model, which provided the count of identified grammatical errors.

The quantity of multimedia elements, including images and videos, was tallied. This indicated the abundance and variety of the content.

Technology Analysis

The technological performance of the homepage was evaluated by quantifying two essential factors:

The duration required for the web page to fully load was measured. Longer loading times might increase bounce rates, making it a crucial element of user experience.

We have detected broken links (links that result in a 404 error). Malfunctioning hyperlinks can negatively affect the user's browsing experience and a website's search engine optimization (SEO).

The pseudocode provides a systematic methodology for evaluating websites' usability listed in a CSV file. The process commences with the retrieval of the website data and the establishment of the LLM model. Functions are established to retrieve and analyze web page material, assess accessibility, optimize marketing (SEO), evaluate content quality, and examine technology. Each website undergoes a process of fetching and parsing its content. Accessibility is evaluated by assessing readability scores, while SEO is determined by counting meta tags. Content quality is analyzed by checking for grammar issues and counting multimedia elements. Technology is measured by loading time and identifying broken links. The outcomes for each website are aggregated and stored in a CSV file, which is subsequently exhibited. This systematic approach guarantees a comprehensive assessment of the usability of every website.:

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions Statement

All authors contributed in writing and reviewing the original manuscript.

Transparency: statement

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Patient: and Public Involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Dissemination: to Participants and Related Patients and Public Communities

As there were no participants involved in this study, there are no dissemination plans to participants or related patients and public communities.

Ethics Statements

No ethical review was conducted, as no patients or animal participants were involved.:

Data Availability.

In this study, the dataset was manually compiled by collecting URLs from institutions offering Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship programs. These URLs were sourced from the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) website, specifically from the GEM Fellowship Programs page. The data collection process occurred in March, 2024 and involved systematically navigating the list of fellowship programs on the SAEM website (

Table A1).

Conflict: of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

SAEM - Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

GEM - Global Emergency Medicine

SEO - Search Engine Optimization

WCAG - Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

LLM - Large Language Model

API - Application Programming Interface

CSV - Comma-Separated Values

Table A1.

URLs of Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship Program Websites. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024.

Table A1.

URLs of Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship Program Websites. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024.

- Global Health and International Emergency Medicine Fellowship

- Global Health | Emergency Medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship | Department of Emergency Medicine | Medical School | Brown University

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship | Atrium Health

- Global Emergency Medical Fellowship | Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

- Global & Urban Emergency Medicine Fellowship - Wayne State University

- Global Health Pathway for Residents and Fellows – Hubert-Yeargan Center for Global Health

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship - Macon & Joan Brock Virginia Health Sciences at Old Dominion University

- Global EM Fellowship | Emory School of Medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine & Public Health Fellowship | School of Medicine and Health Sciences

- International Emergency Medicine Fellowship - Brigham and Women's Hospital

- International Emergency Medicine & Public Health Fellowship | Johns Hopkins Emergency Medicine Fellowship Programs

- Global EM Fellowship - LLU EMERGENCY MEDICINE

- Global Emergency Medicine Division | College of Medicine | MUSC

- Emergency Global Health Fellowship | Icahn School of Medicine

- ZuckerEM @ Northwell – For medical students, resident doctors, and other interested individuals

- Fellowships | Department of Emergency Medicine | School of Medicine | Queen's University

- Global | Emergency Medicine | Stanford Medicine

- International Emergency Medicine Fellowship | Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University

- International Emergency Medicine Fellowship | Emergency Medicine | Fellowships & Residency | SUNY Downstate

- Global EM | UChicago EM

- Global Emergency Medicine - Emergency Medicine

- Global Health Fellowship | Department of Emergency Medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship | UC Davis Emergency Medicine

- Global Health — Taming the SRU

- Global Emergency Medicine and Public Health Fellowship | Department of Emergency Medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship: UF Emergency Medicine » Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship » Department of Emergency Medicine » College of Medicine » University of Florida

- Social and Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship | Department of Emergency Medicine | University of Illinois College of Medicine

- Jackson Memorial & University of Miami Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship | global emergency medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine | Emergency Medicine

- Global EM | PennEM

- urmc.rochester.edu/emergency-medicine/education/fellowship

- Emergency Resident

- Division of Global Emergency Medicine - Global Emergency Medicine Division

- The Global Health Fellowship at UT Health San Antonio - Department of Emergency Medicine

- Global Health Fellowship | School of Medicine | University of Utah Health

- Global Emergency Medicine & Rural Health Fellowship | Department of Emergency Medicine

- Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship – Emergency Medicine – UW–Madison

- Global EM Fellowship | Vanderbilt Emergency

- Weill Cornell - Aga Khan University Joint Global Emergency Medicine Research Fellowship | Emergency Medicine

- Global Health Fellowship < Emergency Medicine |

Table A2.

Stepwise methodology for website technology and usability analysis. Description of each major processing step, consisting of loading the website list, fetching webpage content, and parsing it with BeautifulSoup. Methodology entailed distinct analyses for accessibility (readability), marketing (SEO meta tags), content quality (headings, paragraphs, grammar checking via OpenAI API), and technical metrics (loading time, broken links).

Table A2.

Stepwise methodology for website technology and usability analysis. Description of each major processing step, consisting of loading the website list, fetching webpage content, and parsing it with BeautifulSoup. Methodology entailed distinct analyses for accessibility (readability), marketing (SEO meta tags), content quality (headings, paragraphs, grammar checking via OpenAI API), and technical metrics (loading time, broken links).

BEGIN

LOAD CSV file INTO DataFrame data

SET OpenAI API key

FUNCTION fetch_webpage(URL):

TRY:

FETCH webpage content using requests

PARSE content with BeautifulSoup

RETURN parsed content

EXCEPT Exception as e:

RETURN error message

FUNCTION analyze_accessibility(parsed_content):

EXTRACT paragraphs text from parsed_content

CALCULATE readability score using Textstat

RETURN readability score

FUNCTION analyze_marketing(parsed_content):

COUNT meta tags in parsed_content

RETURN SEO score

COUNT grammar issues in the API response

COUNT multimedia elements in parsed_content

RETURN number of headings, paragraphs, grammar issues, multimedia elements

FUNCTION analyze_technology(URL):

MEASURE the loading time for the web page

IDENTIFY broken links in webpage content

RETURN loading time and number of broken links

For each website in data:

GET website name and URL

CALL fetch_webpage(URL) AND STORE parsed_content OR error

IF error:

STORE website name, URL, error in results

CONTINUE to the following website

CALL analyze_accessibility(parsed_content) AND STORE readability score

CALL analyze_marketing(parsed_content) AND STORE SEO score

CALL analyze_content_quality(parsed_content) AND STORE content quality metrics

CALL analyze_technology(URL) AND STORE technology metrics

STORE all metrics in the results

SAVE results to CSV

DISPLAY the first few rows of results

END

FUNCTION analyze_content_quality(parsed_content):

EXTRACT headings and paragraphs text

CONCATENATE headings and paragraphs text

SEND text to OpenAI API for grammar check

|

References

- Hua, Z.; Yuqing, S.; Qianwen, L.; Hong, C. Factors Influencing eHealth Literacy Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, [online] 2025, 27, e50313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saskia Muellmann, Rebekka Wiersing, Zeeb, H. and Brand, T. Digital Health Literacy in Adults With Low Reading and Writing Skills Living in Germany: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Human Factors, [online] 2025, 12, e65345–e65345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Dahiya, K. Impact of Covid-19 on Digital Healthcare: A New Era of Internet-Based Health Services. JMIR. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, W.; Chang, W.; Everson, J.; Gabriel, M.; Patel, V.; Richwine, C.; Strawley, C. The Evolution of Health Information Technology for Enhanced Patient-Centric Care in the United States (Preprint). Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, T.R.; Hefner, J.L.; Ford, E.W.; McAlearney, A.S.; Menachemi, N. Hospital Website Rankings in the United States: Expanding Benchmarks and Standards for Effective Consumer Engagement. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014, 16, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.J.; Black, K.C.; Calvano, J.D.; Fundingsland Jr, E.L.; Lai, D.; Silacci, S.; et al. An Analysis of US Academic Medical Center Websites: Usability Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021, 23, e27750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, S.N.; Hassan, N.M.; Seman, S.A.A. Online health information seeking behavior pattern. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 10582–10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Pang, Y.; Liu, L.S. Online Health Information Seeking Behavior: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2021, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oermann, M.H.; Lesley, M.L.; VanderWal, J.S. Using Web sites on quality health care to teach consumers in public libraries. Qual Manag Health Care 2005, 14, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.J.; Black, K.C.; Calvano, J.D.; Fundingsland Jr, E.L.; Lai, D.; Silacci, S.; et al. An Analysis of US Academic Medical Center Websites: Usability Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021, 23, e27750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, D.; Black, K.C.; et al. Network Analysis of Academic Medical Center Websites in the United States. Sci Data 2023, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong P, Grob P, DiMattia G, et al. Website Usability Analysis of U.S. Military Residency Programs. Mil Med. Published online October 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fundingsland, E.; Fike, J.; Calvano, J.; et al. Website usability analysis of United States emergency medicine residencies. AEM Educ Train. 2021, 5, e10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, N.; Beach, J.; Calvano, J.; Lu, S.; He, S. American Anesthesiology Residency Programs: Website Usability Analysis. Interact J Med Res. 2022, 11, e38759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kassas, W.S.; Salama, C.R.; Rafea, A.A.; Mohamed, H.K. Automatic Text Summarization: A Comprehensive Survey. Expert Systems with Applications. 2020, 165, 113679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, G.J.; Kim, R.Y.; Weddle, J.B.; Bible, J.E. Can Artificial Intelligence Improve the Readability of Patient Education Materials? . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023, 481, 2260–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhi, A.D.; Ghanem, Y.K.; Yolchieva, L.; et al. Can Artificial Intelligence Improve the Readability of Patient Education Materials on Aortic Stenosis? A Pilot Study. Cardiol Ther. 2024, 13, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Veen D, Van Uden C, Blankemeier L, et al. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 1134–1142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudhvi K, Bharath Chowdary A, Subba Rami Reddy P, Lakshmi Prasanna P. Text Summarization Using Natural Language Processing. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 2020, 535–47.

- Mucha, Justyna Magdalena. Combination of automatic and manual testing for web accessibility. MS thesis. Universitetet i Agder; University of Agder, 2018.

- Sun, Yu Ting, et al. "Accessibility evaluation: manual development and tool selection for evaluating accessibility of e-textbooks." Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering: Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering, July 27-31, 2016, Walt Disney World®, Florida, USA. Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- Mateus, Delvani Antônio, et al. "A systematic mapping of accessibility problems encountered on websites and mobile apps: A comparison between automated tests, manual inspections and user evaluations.". Journal on Interactive Systems 2021, 12, 145–171. [CrossRef]

- Casado Martínez, Carlos, Loïc Martínez-Normand, and Morten Goodwin Olsen. "Is it possible to predict the manual web accessibility result using the automatic result?." Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services: 5th International Conference, UAHCI 2009, Held as Part of HCI International 2009, San Diego, CA, USA, July 19-24, 2009. Proceedings, Part III 5. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009.

- Shuhan, C. , Wamiq, S., Sean, K., Nicole, X., Kevin, Y., Rmaah, Z., Prem, A., Abdel, M., David, B., Norawit, P., & Angela, T. (2024). International emergency medicine network analysis. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Lee, Younghwa, and Kenneth A. Kozar. "Understanding of website usability: Specifying and measuring constructs and their relationships.". Decision support systems 2012, 52, 450–463. [CrossRef]

- Saad, Muhammad, et al. "A comprehensive analysis of healthcare websites usability features, testing techniques and issues.". IEEE access 2022, 10, 97701–97718. [CrossRef]

- Ownby, Raymond L., and Sara J. Czaja. "Healthcare website design for the elderly: improving usability." AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 2003. American Medical Informatics Association, 2003.

- Usman, Muhammad, Mahmood Ashraf, and Masitah Ghazali. "The Usability of Healthcare Websites-How they were Assessed? A Systematic Literature Review on the Usability Evaluation.". Research & Reviews: Journal of Educational Studies 2017, 3, 20–26.

Figure 1.

Box plot analysis depicting website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing, Headers, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, collected from Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. Evaluation of each metric's descriptive statistics, including median, interquartile range, and outliers, with accessibility having the widest range and most outliers, is indicative of website accessibility variability.

Figure 1.

Box plot analysis depicting website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing, Headers, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, collected from Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. Evaluation of each metric's descriptive statistics, including median, interquartile range, and outliers, with accessibility having the widest range and most outliers, is indicative of website accessibility variability.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of Spearman Correlation Coefficients for website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. Red indicates a favorable association between Paragraphs and Headings (0.65), whereas blue indicates a negative correlation between Accessibility and Marketing. This analysis shows essential usability feature relationships. .

Figure 2.

Heatmap of Spearman Correlation Coefficients for website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia, across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. Red indicates a favorable association between Paragraphs and Headings (0.65), whereas blue indicates a negative correlation between Accessibility and Marketing. This analysis shows essential usability feature relationships. .

Figure 3.

Histogram analysis for five key website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia elements, analyzed across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. The distribution patterns highlight variation in design features, with accessibility scores showing a wider spread and more extreme values, indicating disparities in readability and user-friendliness. These visualizations help identify areas where websites adhere to defy usability standards..

Figure 3.

Histogram analysis for five key website usability metrics, consisting of Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia elements, analyzed across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites. The distribution patterns highlight variation in design features, with accessibility scores showing a wider spread and more extreme values, indicating disparities in readability and user-friendliness. These visualizations help identify areas where websites adhere to defy usability standards..

Figure 4.

Bar chart means comparison of Accessibility, Marketing, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia website usability parameters evaluated across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites.. Accessibility shows the highest mean value, reflecting stronger compliance with readability and accessibility standards. In contrast, multimedia and other content-related features have lower average scores, suggesting less emphasis on enriching website design and user engagement..

Figure 4.

Bar chart means comparison of Accessibility, Marketing, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia website usability parameters evaluated across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites.. Accessibility shows the highest mean value, reflecting stronger compliance with readability and accessibility standards. In contrast, multimedia and other content-related features have lower average scores, suggesting less emphasis on enriching website design and user engagement..

Figure 5.

Multiple pairwise comparison analysis using both histogram and scatter plots for the purpose of illustrating the distributions and correlations of the usability metrics Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia usage across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites. Each subplot highlights variations on website performance for different aspects of functionality and content, and in the process revealing patterns and disparities within the sample..

Figure 5.

Multiple pairwise comparison analysis using both histogram and scatter plots for the purpose of illustrating the distributions and correlations of the usability metrics Accessibility, Marketing (SEO), Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia usage across Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship websites. Each subplot highlights variations on website performance for different aspects of functionality and content, and in the process revealing patterns and disparities within the sample..

Table 1.

Summary of variability in usability metrics, including Accessibility, Marketing, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia across five selected Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites . The study aimed to evaluate user-centered design and content quality for prospective applicants. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024.

Table 1.

Summary of variability in usability metrics, including Accessibility, Marketing, Headings, Paragraphs, and Multimedia across five selected Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship program websites . The study aimed to evaluate user-centered design and content quality for prospective applicants. The data collection was conducted in March, 2024.

| Website Index |

Accessibility |

Marketing |

Headings |

Paragraphs |

Multimedia |

| 0 |

76.49 |

0.62 |

16.81 |

6.49 |

0 |

| 1 |

42.41 |

9.34 |

19.27 |

12.07 |

3.21 |

| 2 |

84.59 |

10.02 |

25.6 |

39.26 |

7.93 |

| 3 |

131.57 |

5.99 |

25.24 |

36.41 |

8.26 |

| 4 |

37.26 |

11.62 |

0 |

23.29 |

4.38 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).