1. Introduction

This paper aims to share and promote the implementation of energy efficiency (EE) opportunities at the value chain level. Despite the importance of EE in the food cold chain, the literature still lacks a systematic analysis of these opportunities across the entire value chain. Collaboration among cold chain stakeholders can help remove—or at least reduce—barriers to the adoption of proposed solutions, thereby enhancing both energy savings and environmental benefits. However, there is still limited knowledge on how to effectively overcome these obstacles.

To fill this gap, this paper conducts a systematic literature review on the state of the art of EE solutions at the value chain level, analyzing the required intensity of collaboration among stakeholders. Specifically,

Section 2 introduces the concept of the value chain, with a particular focus on the cold food value chain, while

Section 3 discusses the concept of value chain collaboration.

Section 4 examines the impact of EE at the value chain level.

Section 5 describes the methodology adopted for the literature review, and

Section 6 presents potential energy-saving actions.

Section 7 analyzes the results of the study, while the final section discusses possible directions for future research.

2. Value Chain Definition

The value chain is defined as “the process view of organizations—the idea of seeing a manufacturing (or service) organization as a system made up of subsystems, each with inputs, transformation processes, and outputs. Inputs, transformation processes, and outputs involve the acquisition and consumption of resources such as money, labor, materials, equipment, buildings, land, administration, and management. How value chain activities are carried out determines costs and affects profits” [

1].

There is a common tendency to use the terms value chain and supply chain interchangeably; however, their underlying concepts differ significantly. Supply chain management focuses on activities related to the transformation of raw materials into final products or services, with the primary goal of minimizing total costs. A supply chain refers to the movement of materials among various stakeholders, typically organized around buyer–supplier relationships. In contrast, the value chain emphasizes the value added at each stage of the material transformation process, from one actor to another. In other words, value chain analysis focuses on maximizing the value delivered to the end user [

2].

Reference [

3] identifies three key dimensions of the value chain. The first is its flow, also referred to as its input–output structure. In this context, a value chain consists of a sequence of value-adding economic activities that link products and services together. Beyond this physical structure, a value chain also includes a less visible component: the flow of knowledge and expertise required for the physical input–output structure to function effectively. Although the knowledge flow generally parallels the material flow, its intensity may vary.

The second dimension relates to the geographical spread of the value chain. Some value chains are truly global, involving activities across multiple countries and continents, whereas others are more localized, involving only a few regions of the world.

The third dimension concerns control, that is, the degree of influence that different actors exert over the activities comprising the chain. Each actor directly controls its own operations and may be directly or indirectly controlled by others.

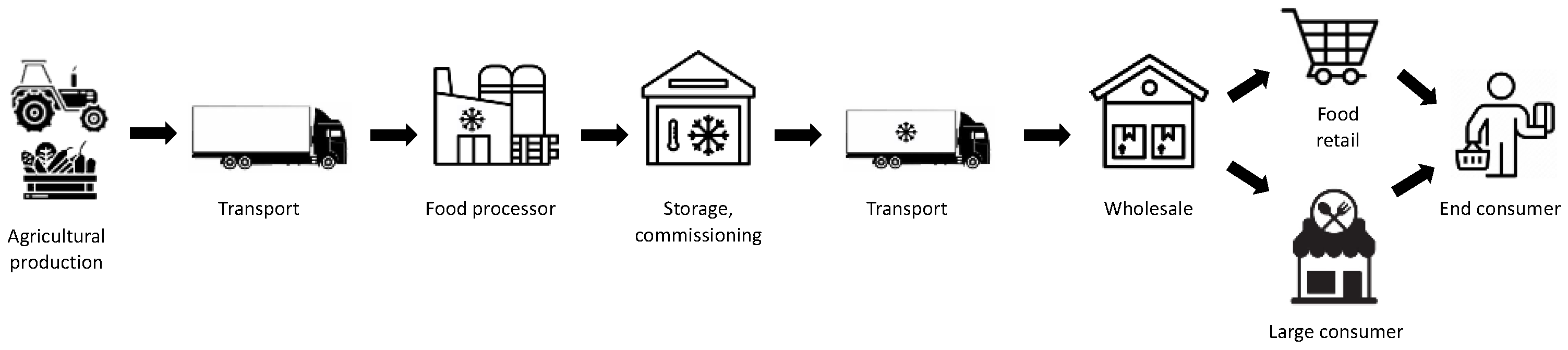

Specifically, a cold chain is a temperature-controlled value chain that encompasses the harvesting, storage, transportation, and distribution of perishable goods such as fruits and vegetables, seafood, meat, and dairy products. The structure of the cold chain varies depending on the product; however, based on storage temperature, it is typically divided into two main categories: cold (above 0 °C) and frozen (below 0 °C).

Figure 1 presents a simplified schema of a cold value chain, highlighting temperature-controlled stages such as food processing, storage, and transportation.

Due to the high cooling loads and strict temperature requirements throughout its stages, the cold chain is considered highly energy-intensive. To prevent value loss, it is essential to optimize energy consumption not only within individual stages but especially at the interfaces between stages.

The objective of this study is to analyze collaborative approaches for improving energy efficiency (EE) and integrating renewable energy sources, with a particular focus on refrigerated transport and storage. Specifically, this research aims to identify possible improvement actions—derived from real case studies in the literature—by examining the interactions among firms within the value chain. Section III introduces the concept of collaboration models in the value chain and presents the proposed model, followed by a discussion of the importance of optimizing energy consumption at the value chain level in cold chains.

3. Value Chain Definition

Value chain collaboration refers to the cooperation among different actors within the value chain to achieve common goals and improve overall performance. Several key aspects are essential for successful value chain collaboration:

Communication: Clear, frequent, and balanced communication builds strong relationships across the value chain and facilitates the exchange of information, ideas, and best practices.

Execution: This involves sharing resources, expertise, and responsibilities to achieve mutual benefits and enhance overall performance.

Governance: Effective collaboration requires well-defined protocols, guidelines, and frameworks to support interactions among partners and manage the measurement and distribution of shared value.

Organizational Redesign: In some cases, internal organizational changes are necessary to promote collaboration. This may involve restructuring departments, roles, and responsibilities to align with shared value chain objectives.

Benefit-Sharing: A fair and transparent approach to benefit-sharing ensures that the returns from collaborative efforts are distributed equitably among all partners.

Knowledge Transfer: Collaboration often requires specific skills and expertise. Promoting knowledge transfer, talent management, and continuous learning are key factors in fostering effective collaboration within the value chain.

Data Sharing and Integration: The sharing and integration of data across the value chain are vital for effective collaboration. Modern supply chain collaboration platforms enable organizations to connect different parts of the chain, specify requirements, and address potential disruptions more efficiently.

Shared Interests and Solutions: Successful collaboration relies on a mutual understanding of each party’s interests and on joint problem-solving to create solutions that benefit all stakeholders.

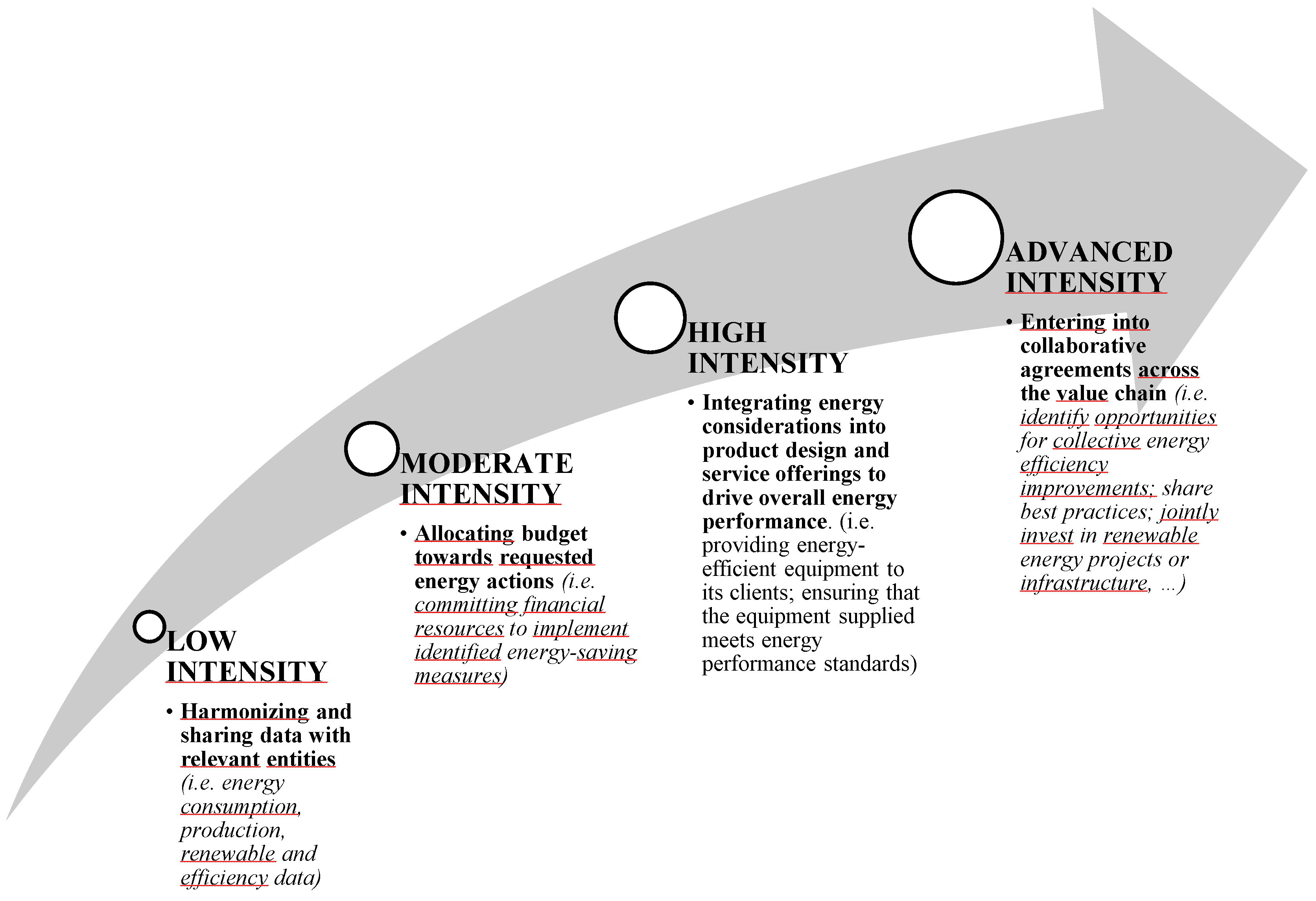

In particular, value chain collaboration models for energy efficiency focus on the coordination and cooperation of different actors within the chain to improve energy performance. The goal is to identify and implement energy-saving measures throughout the value chain, resulting in cost reductions, lower environmental impact, and increased competitiveness. This study identifies four levels of collaboration intensity within the value chain:

Low-Intensity Collaboration: At this level, the focus is on harmonizing and sharing data with relevant stakeholders. This involves establishing standardized data collection and reporting processes across the value chain. By sharing energy consumption, production, renewable, and efficiency data, stakeholders can gain insights into their energy performance and identify areas for improvement.

Moderate-Intensity Collaboration: Beyond data harmonization, this level includes allocating budgets for energy initiatives. In this model, value chain members actively participate in energy performance improvement initiatives by committing financial resources to implement identified energy-saving measures. Through investments in actions such as energy audits, equipment upgrades, or process optimization, partners can collectively achieve greater efficiency and cost savings.

High-Intensity Collaboration: This level integrates energy considerations into product design and service offerings. For example, a manufacturer may provide energy-efficient equipment to downstream partners. By ensuring compliance with energy standards, such collaboration enhances overall energy performance across the value chain.

Advanced-Intensity Collaboration: The most integrated form of collaboration involves formal agreements and coordinated action across the entire value chain. Partners jointly identify energy efficiency opportunities, share best practices, and co-invest in renewable energy projects or shared infrastructure. By aligning their efforts, value chain partners can maximize energy performance, optimize resource use, and achieve sustainable outcomes.

Figure 2.

Value Chain collaboration intensity level.

Figure 2.

Value Chain collaboration intensity level.

4. Reasons for Energy Efficiency Need in the Cold Chain

Cold chain stakeholders are increasingly implementing measures to combat global warming, with a primary focus on improving energy efficiency (EE) to reduce primary energy consumption. These improvements range from investing in advanced, best-in-class technologies—capable of reducing energy use by 15–40%—to adopting simpler, cost-effective operational practices within refrigeration systems and broader manufacturing processes, which can lower energy costs by 15% or more.

Energy efficiency measures offer considerable potential to generate economic, environmental, and social benefits. Beyond direct energy savings, EE measures provide a range of non-energy benefits (NEBs), including:

Increased Productivity and Reduced Operating Costs: Enhancing system reliability and aligning refrigeration load with equipment capacity improve overall system efficiency.

Environmental Improvements: Lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and reduced waste contribute to more sustainable operations.

Enhanced Public Image: Companies gain reputational advantages due to growing societal concern about climate change.

Increased Sales: Lower environmental impact can positively influence customer perception and purchasing behavior.

Reduced Spoilage of Perishable Goods: By optimizing and monitoring the time–temperature relationship and associated energy consumption, spoilage can be significantly reduced.

Currently, most firms within the value chain focus primarily on EE measures, while NEBs are often considered only from a broader cold value chain perspective [

4]. Adopting a value chain approach, however, enhances opportunities for achieving greater energy cost reductions [

5].

The results of energy flow mapping provide decision-makers with valuable insights to identify the most energy-intensive stages of the cold chain [

6]. Specifically, reference [

6] proposes a quantitative approach to mapping energy flows across the cold chain, taking into account the time–temperature relationship of products from farm to fork. In addition, reference [

7] introduces a dedicated toolbox to support decision-makers and stakeholders in assessing EE strategies across food cold value chains. This toolbox helps optimize various environmental performance indicators, including specific energy consumption, overall environmental impact, and NEBs. Furthermore, reference [

6] presents a methodology to assess and prioritize EE measures for cold chains in terms of quality losses and specific energy consumption, categorizing them into technological, maintenance-related, and managerial opportunities.

5. Research Process and Method

Value chain collaboration plays a crucial role in identifying opportunities for improving energy efficiency (EE) and achieving outcomes that are shared among all stakeholders. However, a systematic categorization of EE opportunities within the cold value chain has not yet been proposed in the literature. This paper aims to address this gap by identifying such opportunities and analyzing the type and intensity of collaboration involved, along with the potential outcomes and key benefits.

To achieve these objectives, a scientific literature review was conducted as reported in [

8]. The review was based on the Scopus database and performed in December 2024. The selection procedure followed the guidelines outlined by [

9]. A structured search was carried out by combining the keywords “cold supply chain”, “cold value chain”, “food value chain”, “refrigerated storage”, and “refrigerated transport” using the following query:

((TITLE-ABS-KEY(cold AND supply AND chain) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY(cold AND value AND chain) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY(food AND value AND chain) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY(refrigerated AND storage) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY(refrigerated AND transport))

AND PUBYEAR > 1984

AND PUBYEAR < 2025

AND (LIMIT-TO(SUBJAREA, “ENGI”))

AND (LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE, “English”))

AND (LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “cp”)))

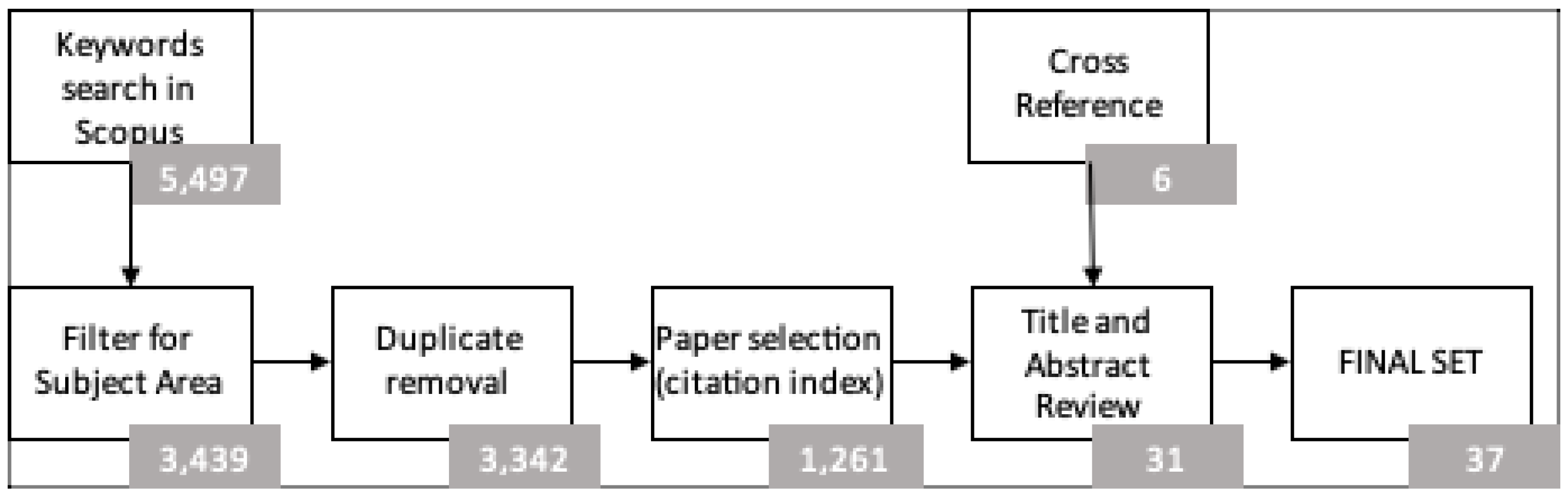

The initial keyword search yielded 5,497 entries (for the period 1985–2024). After restricting the results to the Engineering subject area and selecting only articles and conference papers written in English, the number of documents was reduced to 3,439. Following the removal of duplicates, 3,342 papers remained.

To ensure the quality and relevance of the reviewed studies, papers with a low citation index were excluded, resulting in 1,261 papers. These were further screened by reading their titles and abstracts. When the relevance could not be determined from the title or abstract alone, the full text was examined. The inclusion criteria for the literature review were as follows:

The paper addresses and discusses EE opportunities in the cold value chain;

The paper focuses specifically on the value chain level, while studies addressing only macro-level aspects (e.g., national-scale impacts) were excluded.

Figure 3.

Systematic literature review process.

Figure 3.

Systematic literature review process.

A total of 31 papers were initially selected based on these criteria. To address potential limitations of the keyword search, the selection was further complemented through cross-referencing, as recommended in [

9]. This additional step resulted in the inclusion of six more papers. Consequently, a total of 37 papers were selected and analyzed in detail.

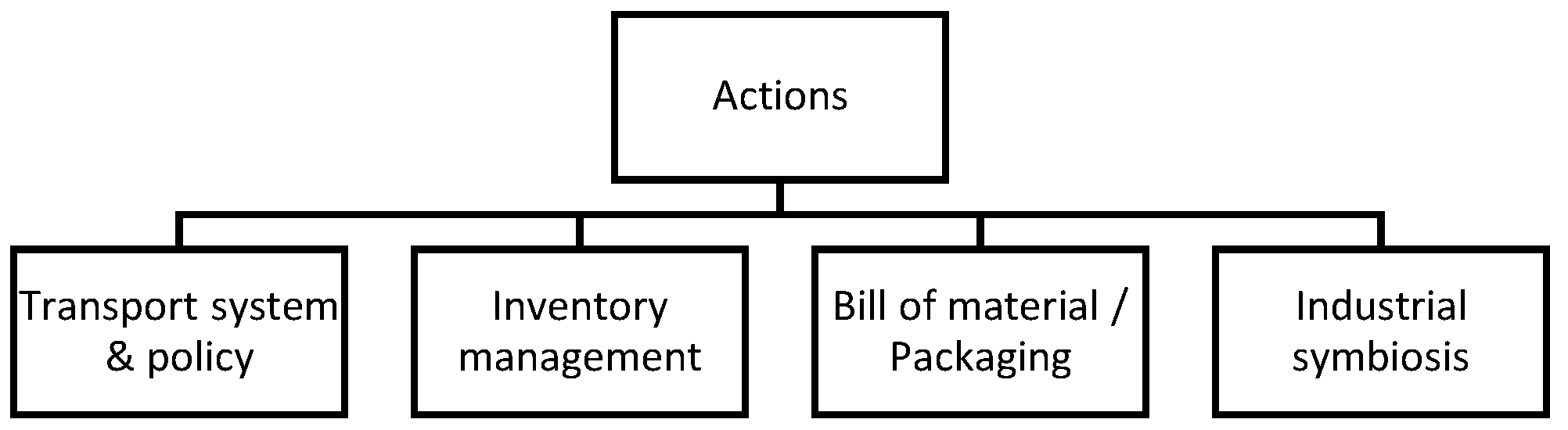

6. List of Possible Actions at the Value Chain Level

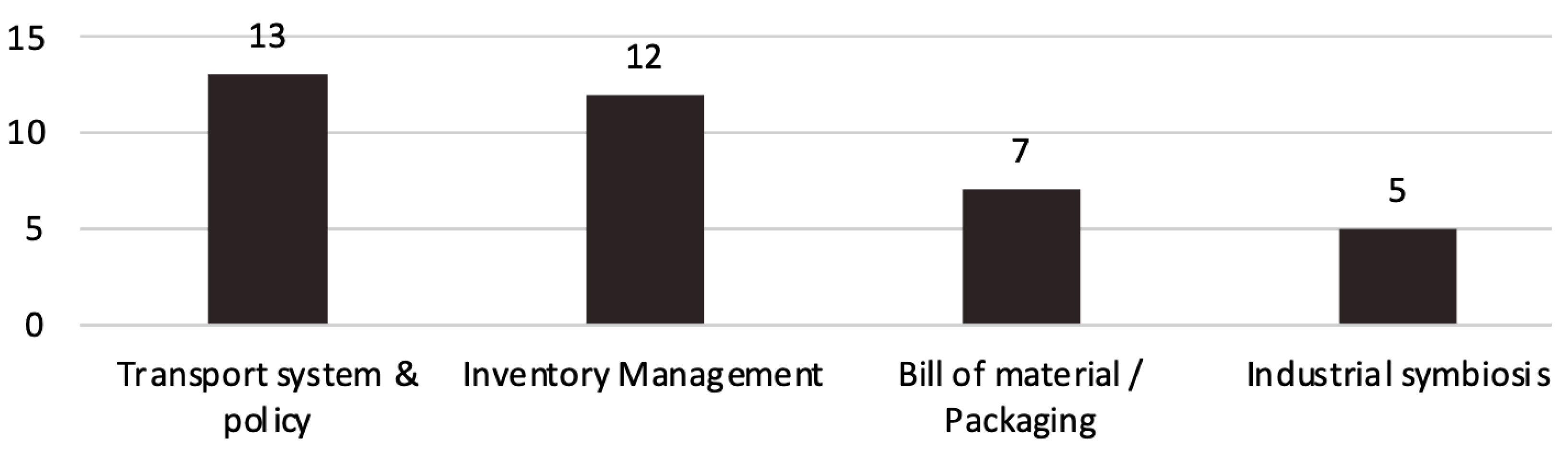

The aim of this study is to identify actions to enhance the sustainability and energy performance of cold value chains in the food sector, while also analyzing the level of collaboration required for their implementation. The 37 papers reviewed in the literature analysis were categorized according to the topics addressed and the proposed solutions (

Figure 4).

Transport System & Policy: This category includes the optimization of energy consumption during transportation, with a focus on network design optimization and route planning.

Inventory Management: This involves improvement actions related to inventory coordination among stakeholders within the same value chain.

Bill of Materials/Packaging: This category addresses the use of materials in product transformation and their redesign in relation to energy consumption and packaging considerations.

Industrial Symbiosis: This refers to energy symbiosis among value chain actors and explores the main constraints hindering the implementation of such initiatives.

Figure 5 illustrates the number of articles per category. It is evident that the largest number of studies focus on transport systems and related policies. Other categories—such as industrial symbiosis, bill of materials/packaging, and energy communities—are less represented. In our view, this may be due to significant implementation barriers, particularly in the cases of industrial symbiosis and bill of materials/packaging.

6.1. Transportation System & Policy

The optimal configuration of a cold supply chain distribution network can have a significant impact on the overall eco-efficiency of the value chain. Two key factors influencing network configuration are the number and location of distribution centers (DCs).

An increase in the number of DCs generally reduces supply chain costs but can also lead to a rise in the environmental impact of the chain [

10]. The results obtained indicate the potential economic and environmental performance outcomes achievable with different numbers of DCs within the supply chain.

The location of DCs has also been investigated by [

11], whose model aims to minimize total costs—including transportation, hub establishment, temperature adjustment in storage compartments, and carbon emission costs—while maximizing product quality across varying temperature requirements.

Transshipment has proven to be an effective tool for supply chain pooling. Reference [

12] demonstrates that transshipment among DCs can significantly reduce both GHG emissions and operational costs in cold supply chains.

By integrating variables related to distribution, transportation, and inventory management, [

13] proposed a model to minimize the energy consumption and carbon emissions of logistics providers. The results show a remarkable decrease in total expenses by 100.25% and in environmental impact by 100.04%. Similarly, [

14] developed a mixed-integer optimization model to address allocation and routing problems within a cold supply chain. When applied to a real case study, the model achieved a 9.25% cost reduction compared to the current situation.

To support the design of sustainable cold chains, [

15] proposed a model that minimizes total energy consumption by identifying the optimal route and mode of transport based on product shelf life and required storage temperatures. Reference [

16] highlighted that commodity characteristics and voyage distances are key factors influencing the choice of shipping mode.

Reference [

17] analyzed the economic and environmental benefits of modular transport devices in the cold chain, particularly in cases where the volume utilization of standard refrigerated vehicles is low (e.g., less-than-truckload transport), without requiring investment in specialized trucks or infrastructure.

In another case study, [

18] demonstrated that adjusting vessel speed can reduce energy consumption while maintaining product quality. Reference [

19] found that vessel speed tends to decrease as bunker fuel prices rise, with this effect being more pronounced for less perishable goods.

Travel route optimization can substantially improve the energy efficiency (EE) of cold-chain logistics systems. Reference [

20] developed mathematical models for cold-chain logistics (MMCCL) to estimate fuel consumption and carbon emissions, aiming to identify the most carbon-efficient routes. In cold-chain logistics, navigation systems specifically designed for refrigerated transport must consider not only travel time and cost but also the energy required for cooling. Effective optimization minimizes both vehicle propulsion and refrigeration energy while maximizing load utilization.

Given the uncertainty inherent in real-world distribution, [

21] proposed a fuzzy approach to determine optimal frozen food distribution routes under uncertain time constraints. Reference [

22] developed an optimization-based decision-making model that enables real-time route adjustments through RFID-monitored shipments and strategically placed reader checkpoints along transportation routes.

Finally, [

23] demonstrated that aligning distribution activities with weather conditions can reduce both energy consumption and operational costs—a benefit that becomes increasingly significant as ambient temperatures rise. All the actions mentioned above require an advanced level of collaboration among value chain actors, particularly in sharing information to optimize transportation processes.

Table 1 presents the main measures related to the Transportation System & Policy category, as identified through the literature analysis. Specifically, the table indicates the required level of collaboration intensity, which, for this category, is classified as high or advanced.

6.2. Inventory Management

To reduce inventory levels and improve service performance in cold value chains, a comparative analysis of three inventory policies—Lot-for-Lot, Traditional, and Consignment Stock (CS)—with respect to energy consumption and environmental impact shows that the CS agreement can be particularly effective. CS involves smaller lot sizes and more frequent shipments, with most of the inventory located closer to the customer, thereby reducing overall storage time [

24].

Although CS has been shown to be more profitable than traditional agreements, this is not always the case for all stakeholders within the supply chain. A profit-sharing mechanism can address this imbalance, ensuring that both the vendor and the buyer benefit from the CS agreement [

25]. Implementing this policy requires an advanced level of collaboration among value chain partners, as they must share information to optimize inventory management. This approach is especially relevant for food cold chains, where demand may be stock-dependent.

Reference [

26] develops a model that considers batch size and energy consumption in cold chains, while [

27], using the same case study, proposes a method to approximate the optimal temperature. Reference [

28] presents a model to determine optimal decisions for producers and distributors—such as order quantity, freshness-preserving efforts, and pricing—in both decentralized and centralized systems.

Reference [

29] introduces three models to determine optimal lot sizing and shipment quantities: one focused on minimizing operational costs, another on minimizing the carbon footprint, and a hybrid model that accounts for both economic and environmental factors. The hybrid model yields the best results in terms of cost savings and carbon emission reduction, particularly when carbon taxes are considered.

To identify optimal replenishment policies and transportation schedules, [

30] highlights that higher carbon prices do not necessarily lead to greater cold supply chain efficiency. Instead, employing a heterogeneous fleet—including light-duty and medium-duty vehicles—can further reduce both costs and emissions.

Since cold products often require different temperature settings and cannot always be stored or transported together, [

31] proposes a multi-product inventory model to determine the optimal inventory levels for each product family, minimizing either total cost or carbon-equivalent emissions.

Taking into account product quality degradation and adopting shelf-life-based pricing, [

32] demonstrates that maximizing system-wide joint profit can be achieved by coordinating the manufacturing cycle with the inbound and outbound delivery frequencies of materials throughout the production process.

Reference [

33] proposes a model to minimize total cost by optimizing purchasing, inspection, food waste, packaging, cold storage, transportation, and carbon emission costs. The authors show that total costs and emissions are significantly affected by temperature variance, carbon penalty costs, and the types of vehicles employed.

Refrigerated warehouses are more energy-efficient when fully stocked, as this reduces the volume of air that needs to be cooled. Reference [

34] examines the combined effects of warehouse fill level and internal temperature, identifying the optimal lot size that minimizes total system cost. Finally, [

35] demonstrates that extending storage durations increases energy consumption and emissions, reinforcing the importance of sustainable and short cold chains.

Table 2 presents the main measures related to the Inventory Management category. Specifically, the measures analyzed in this category require an advanced level of collaboration. This is due to the need for specific agreements that enable the benefits generated by optimizing the entire value chain to be shared among different actors.

6.3. Bill of Material and Packaging

Modifying the Bill of Materials (BOM) can provide an effective strategy for improving environmental sustainability and reducing costs throughout the food value chain. Substituting a raw material with a locally sourced alternative can significantly reduce transportation requirements, thereby lowering fuel consumption and associated emissions [

36].

Using a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for an ice-cream value chain in a UK company, [

37] demonstrated that premium ice-cream flavors (such as chocolate and vanilla) have a higher environmental impact than standard ones, primarily due to differences in their recipes. Similar results are reported by [

38], who identified opportunities to enhance eco-efficiency and help consumers choose more environmentally friendly products in the confectionery and frozen dessert sectors.

Packaging specifically designed for refrigerated transport can reduce cooling time and offer substantial energy-saving potential. Reference [

39] shows that adding bottom vent holes to fruit and vegetable packaging can shorten cooling time by 37%. Reference [

40] recommends integrating Peltier cells into secondary and tertiary packaging to improve system efficiency and minimize temperature fluctuations during critical loading and unloading phases.

The extensive use of conventional, fossil-fuel-based food packaging contributes to environmental problems through the generation of long-lasting waste. Packaging accounts for approximately 42% of total plastic waste [

41]. Non-plastic packaging materials generate substantially lower environmental impacts than plastic alternatives—not only because of their renewable origin but also due to differences in manufacturing processes and energy consumption during production [

42].

Table 3 summarizes the main measures related to the Bill of Materials and Packaging category. The first measure requires a high level of collaboration, as the choice of packaging material directly affects waste management across the entire value chain. The second measure, however, is typically determined by individual companies, based on data sharing with other actors in the value chain.

6.4. Indistrial Symbiosis

Direct inter-firm resource recovery is the cornerstone of Industrial Symbiosis (IS), which is based on achieving both economic and environmental benefits through the exchange of by-products among companies in close proximity [

43].

Reference [

44] analyzes the potential for IS between a forging industry and a nearby greenhouse installation. The results indicate three types of economic savings: (1) increased revenues deriving from the CO2 enrichment process, (2) elimination of natural gas consumption, and (3) reduction of CO2 emissions fees of the industrial plant. Similarly, [

45], through a life cycle assessment of beef production supply chain, promotes industrial symbiosis scenarios and evaluates the most efficient options.

The use of anaerobic digestion and cogeneration technologies enables the reconversion of food waste into usable energy within the value chain.

Reference [

46] proposes recovering and reusing the cold energy wasted during the liquefied natural gas (LNG) gasification process. This energy can be utilized in other processes, by different strategic business units, or by nearby companies requiring cooling, thereby improving overall energy efficiency.

Reference [

47] models a poly-generation plant designed for both power and cold production for recovering cold energy from LNG regasification in a district cooling network with three different temperature levels. The plant achieves an equivalent energy saving of 81.1 kW per ton of LNG, with an exergetic efficiency of 34.7%.

Table 4 summarizes the main measures associated with the Industrial Symbiosis category. The measures analyzed in this category require an advanced level of collaboration, due to the specific investments needed to implement by-product exchange systems.

7. Discussion

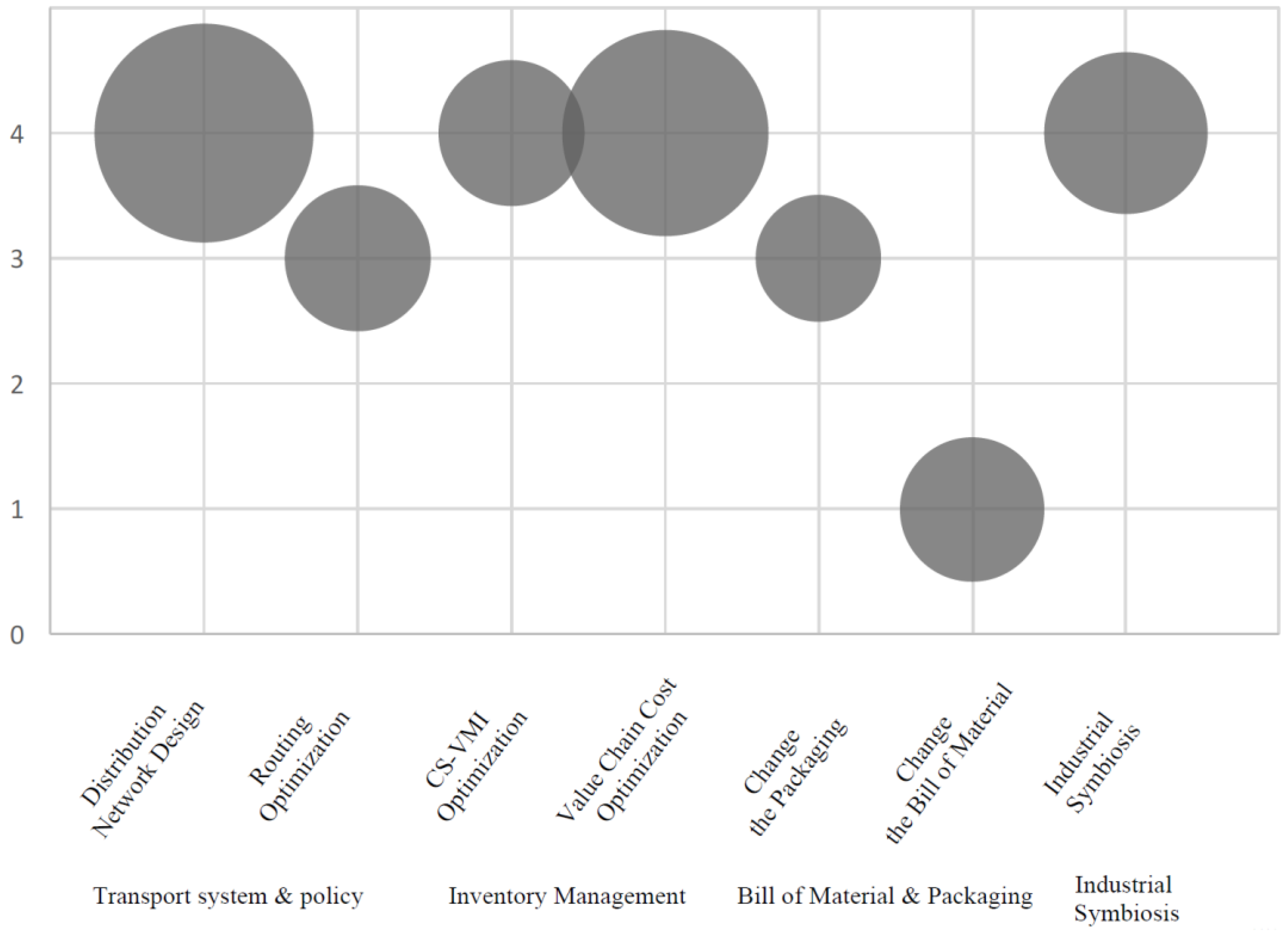

As shown in

Section 6, the actions proposed in the literature to improve the energy efficiency and performance of cold value chains involve varying degrees of collaboration among stakeholders.

Figure 6 summarizes the relationship between the proposed actions—categorized as defined earlier—and the required intensity of collaboration. In this graph, the size of each bubble represents the number of papers analyzing each specific action.

Analysis of the results reveals that most actions across the different categories require either high or advanced levels of collaboration. At these levels, integrating energy considerations into product design and service offerings becomes critical for enhancing overall energy performance. Moreover, collaborative agreements across the value chain must be established, focusing on the optimization of shared performance metrics.

An exception to this trend is the review of the bill of materials, which requires only a low level of collaboration. In this case, collaboration is primarily limited to data sharing necessary for assessing the energy and environmental impact of the materials used in production.

While these solutions can significantly reduce energy costs and environmental impact, their implementation becomes more complex as the required collaboration intensity increases. This complexity arises from the high degree of coordination needed, such as redesigning distribution networks, implementing Vendor-Managed Inventory (VMI), and adopting consignment stock strategies.

To facilitate such levels of collaboration, the following elements are essential:

Definition of common performance metrics and goals, to coordinate stakeholders across the value chain in implementing the proposed actions.

Establishment of specific agreements among stakeholders, outlining how the resulting benefits will be shared.

It is also important to note that, in general, the successful implementation of these actions requires appointing a value chain leader responsible for coordinating the activities of the various actors involved.

Considering the specific characteristics of the cold food chain, the primary focus of optimization for reducing energy costs and environmental impact lies in improving the efficiency of energy used for refrigeration. Based on the actions analyzed across different categories, energy consumption can be reduced and environmental performance enhanced through the following measures:

Reducing the time products spend in refrigerated inventory, while simultaneously optimizing the frequency of replenishments from various suppliers.

Shortening the duration of refrigerated transportation by optimizing routes and increasing vehicle load utilization.

Minimizing the distance between actors in the value chain by prioritizing the use of local or “low-distance” materials.

Redesigning packaging materials by switching to non-plastic alternatives.

Recovering and reusing cold energy wasted during the liquefied natural gas (LNG) gasification process.

8. Conclusions

This research aims to analyze value chain collaborations among actors in the food industry, with particular emphasis on the cold value chain. The study focuses specifically on collaborative strategies for enhancing energy efficiency in this context. Four levels of collaboration are defined within the value chain:

Low-Intensity Collaboration: Establishes standardized data collection and reporting practices across the value chain.

Moderate-Intensity Collaboration: Involves harmonizing and sharing data, as well as allocating budgets for energy-related actions.

High-Intensity Collaboration: Integrates energy considerations into product design and service offerings to improve overall energy performance.

Advanced-Intensity Collaboration: Represents the highest level of collaboration, requiring formal agreements across the value chain to achieve energy performance improvements.

Proposed energy efficiency actions are grouped into four categories:

Transport System & Policy: Focuses on network design and route optimization.

Inventory Management: Includes improvements related to the coordination of refrigerated inventory.

Bill of Materials/Packaging: Involves material substitution in production and packaging to reduce environmental impact.

Industrial Symbiosis: Implements by-product exchange strategies to leverage opportunities arising from geographical proximity.

The analysis indicates that these actions generally require high or advanced levels of collaboration and face the following main barriers:

The need to define common performance targets and goals among value chain participants.

The necessity of establishing formal agreements to govern benefit-sharing.

The requirement for a value chain leader to coordinate collaborative efforts.

Despite these challenges, inter-actor collaborative actions yield substantial improvements in energy efficiency. In the specific context of the cold value chain, the following benefits can be achieved:

Reduced time in refrigerated inventory.

Reduced time in refrigerated transport.

Minimized distance between value chain actors.

Redefined packaging using non-plastic materials.

Recovery and reuse of cold energy from LNG gasification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, I. Ferretti.; supervision, S. Zanoni.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work is part of the activities carried out in the context of the REEVALUE project (Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in the Value Chain), funded by the European Union – European Union’s Environment and Climate Action (LIFE 2014–2020) programme under grant agreement No 101119828.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Porter, M.E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, The Free Press, pages 11-15 (1985).

- Reddy, A.A., Training Manual on Value Chain Analysis of Dryland Agricultural Commodities, International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), page 4 (2013). [CrossRef]

- McCormick, D., Schmitz, H., Manual for Value Chain Research on Homeworkers in the Garment Industry, Institute for Development Studies, Pages 17-19 (2001).

- Neusel, L., Zanoni, S., Hirzel, S., Marchi, B., Energy efficiency from farm to fork? On the relevance of non-energy benefits and behavioural aspects along the cold supply chain, Eceee Industrial Summer Study Proceedings, Volume 2020-September, Pages 101 - 110 (2020).

- Zanoni, S., Marchi, B., Puente, F., Neusel, L., Hirzel, S., Krause, H., Saygin, D., Oikonomou, V., Improving Cold Chain Energy Efficiency: EU H2020 project for facilitating energy efficiency improvements in SMEs of the food and beverage cold chains, Refrigeration Science and Technology, Volume 2020-August, Pages 361 - 369 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Marchi, B., Bettoni, L., Zanoni, S., Assessment of Energy Efficiency Measures in Food Cold Supply Chains: A Dairy Industry Case Study, Energies, Volume 15, Issue 19, Article number 6901 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F., Vignati, J.A., Marchi, B., Paoli, R., Zanoni, S., Romagnoli, F., Effects of Energy Efficiency Measures in the Beef Cold Chain: A Life Cycle-based Study, Environmental and Climate Technologies, Volume 25, Issue 1, Pages 343 - 355 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P., Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review, British Journal of Management, Volume 14, Issue 3, Pages 207 – 222, (2003). [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S., Gold, S., Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management, Supply Chain Management, Volume 17, Issue 5, Pages 544 – 555 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, S., Mazzoldi, L., Ferretti, I., Eco-efficient cold chain networks design, International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, Volume 12, Issue 5, Pages 349 - 364 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Golestani, M., Moosavirad, S.H., Asadi, Y., Biglari, S., A Multi-Objective Green Hub Location Problem with Multi Item-Multi Temperature Joint Distribution for Perishable Products in Cold Supply Chain, Sustainable Production and Consumption, Volume 27, Pages 1183 - 1194 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.T., Ko, J., Inventory Transshipment Considering Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Sustainable Cross-Filling in Cold Supply Chains, Sustainability (Switzerland), Volume 15, Issue 9, Article number 7211 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Egami, R.H.M., Mathematical programming model for cost-optimized and environmentally sustainable supply chain design, AIP Advances, Volume 14, Issue 2, Article number 025230 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Al Theeb, N., Smadi, H.J., Al-Hawari, T.H., Aljarrah, M.H., Optimization of vehicle routing with inventory allocation problems in Cold Supply Chain Logistics, Computers and Industrial Engineering, Volume 142, Article number 106341 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A., Accorsi, R., Baruffaldi, G., Manzini, R., Designing sustainable cold chains for long-range food distribution: Energy-effective corridors on the Silk Road Belt, Sustainability (Switzerland), Volume 9, Issue 11, Article number 2044 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Lam, J.S.L., Shipping mode choice in cold chain from a value-based management perspective, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, Volume 11, Issue 5, Article number 1029 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, I., Mazzoldi, L., Zanoni, S., Environmental impacts of cold chain distribution operations: A novel portable refrigerated unit, International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, Volume 31, Issue 2, Pages 267 - 297 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., de Kleuver, C., de Leeuw, S., Behdani, B., Trading off cost, emission, and quality in cold chain design: A simulation approach, Computers and Industrial Engineering, Volume 158, Article number 107442 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Li, M., Xing, T., Zhang, Y., Research on the characteristics of photovoltaic-driven refrigerated warehouse system under different ice storage modes, Results in Engineering, Volume 21, Article number 101804 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Habibur Rahman, M., Fashiar Rahman, M., Tseng, T.-L., Estimation of fuel consumption and selection of the most carbon-efficient route for cold-chain logistics, International Journal of Systems Science: Operations and Logistics, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article number 2075043 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Brito, J., Martinez, F.J., Moreno, J.A., Verdegay, J.L., Fuzzy optimization for distribution of frozen food with imprecise times, Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making, Volume 11, Issue 3, Pages 337 - 349 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Mejjaouli, S., Babiceanu, R., Cold supply chain logistics: System optimization for real-time rerouting transportation solutions, Computers in Industry, Volume 95, Pages 68 - 80 (2018). S. [CrossRef]

- Accorsi, R., Gallo, A., Manzini, R., A climate driven decision-support model for the distribution of perishable products, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 165, Pages 917 - 929 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, S., Jaber, M., A two-level supply chain with consignment stock agreement and stock-dependent demand, International Journal of Production Research, Volume 53, Issue 12, Pages 3561 - 3572 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Marchi, B., Zanoni, S., Ferretti, I., Zavanella, L.E., Stimulating investments in energy efficiency through supply chain integration, Energies, Volume 11, Issue 4, Article number 858 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, S., Zavanella, L., Chilled or frozen? Decision strategies for sustainable food supply chains, International Journal of Production Economics, Volume 140, Issue 2, Pages 731 - 736 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Wahab M.I.M., Chilled or frozen? Decision strategies for sustainable food supply chains: A note, 2015 12th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, ICSSSM 2015, Article number 7170244 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., Chen, J., Xiao, Y., Xu, X., Optimization and coordination of fresh product supply chains with freshness-keeping effort, Production and Operations Management, Volume 19, Issue 3, Pages 261 - 278 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Hariga, M., As’ad, R., Shamayleh, A., Integrated economic and environmental models for a multi stage cold supply chain under carbon tax regulation, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 166, Pages 1357 - 1371 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Babagolzadeh, M., Shrestha, A., Abbasi, B., Zhang, Y., Woodhead, A., Zhang, A., Sustainable cold supply chain management under demand uncertainty and carbon tax regulation, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Volume 80, Article number 102245 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Borzogli, A., Multi-product inventory model for cold items with cost and emission consideration, International Journal of Production Economics, Volume 176, Pages 123 - 142 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Fauza, G., Amer, Y., Lee, S., Prasetyo, H., An integrated single-vendor multi-buyer production-inventory policy for food products incorporating quality degradation, International Journal of Production Economics, Volume 182, Pages 409 - 417 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Wangsa, I. D., Vanany, I., Siswanto, N., An optimization model for fresh-food electronic commerce supply chain with carbon emissions and food waste, Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, Volume 40, Issue 1, Pages 1 - 21 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Marchi, B., Zanoni, S., Jaber, M., Energy implications of lot sizing decisions in refrigerated warehouses, Energies, Volume 13, Issue 7, Article number 1739 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, M., van Eeden, J., Goedhals-Gerber, L.L., Energy and emissions: Comparing short and long fruit cold chains, Heliyon, Volume 10, Issue 11, Article number e32507 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.N., Ball, A.S., Lang, T., Morison, J.I.L., Farm costs and food miles: An assessment of the full cost of the UK weekly food basket, Food Policy, Volume 30, Issue 1, Pages 1 - 19 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Konstantas, A., Stamford, L., Azapagic, A., Environmental impacts of ice cream, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 209, Pages 259 - 272 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Konstantas, A., Stamford, L., Azapagic, A., A framework for evaluating life cycle eco-efficiency and an application in the confectionary and frozen-desserts sectors, Sustainable Production and Consumption, Volume 21, Pages 192 - 203 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Getahun, S., Ambaw, A., Delele, M., Meyer, C.J., Opara, U.L., Analysis of airflow and heat transfer inside fruit packed refrigerated shipping container: Part II – Evaluation of apple packaging design and vertical flow resistance, Journal of Food Engineering, Volume 203, Pages 83 - 94 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P., Gaspar, P.D., Silva, P.D., Peltier Cell Integration in Packaging Design for Minimizing Energy Consumption and Temperature Variation during Refrigerated Transport, Designs, Volume 7, Issue 4, Article number 88 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R., Jambeck, J.R., Law, K.L., Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made, Science Advances, Volume 3, Issue 7, Article number e1700782 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, A., Salehy, Y., Derens-Bertheau, E., Duret, S., Adlouni, M.E., Merouani, A., Annibal, S., Mireur, M., Merendet, V., Hoang, H.-M., Strawberry supply chain: Energy and environmental assessment from a field study and comparison of different packaging materials, International Journal of Refrigeration, Volume 153, Pages 78 - 89 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R., “Uncovering” industrial symbiosis, Journal of Industrial Ecology, Volume 11, Issue 1, Pages 11 - 30 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Marchi, B., Zanoni, S., Pasetti, M., Industrial symbiosis for greener horticulture practices: the CO2 enrichment from energy intensive industrial processes, Procedia CIRP, Volume 69, Pages 562 - 567 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Diaz, F., Romagnoli, F., Neusel, L., Hirzel, S., Paulus, J., Marchi, B., Zanoni, S., The ICCEE Toolbox. A Holistic Instrument Supporting Energy Efficiency of Cold Food and Beverage Supply Chains, Environmental and Climate Technologies, Volume 26, Issue 1, Pages 428 - 440 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, H.J., Pantoja, J.M., Monica, M., Vasconez, J.P., Briceno, I.C., Larenas, R.A., Dionicio, N.-R., Proposal for the Recovery of Waste Cold Energy in Liquefied Natural Gas Satellite Regasification Plants, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 220, Pages 940 - 945 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Atienza-Márquez, A., Bruno, J.C., Coronas, A., Cold recovery from LNG-regasification for polygeneration applications, Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 132, Pages 463 - 478 (2018). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).