Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

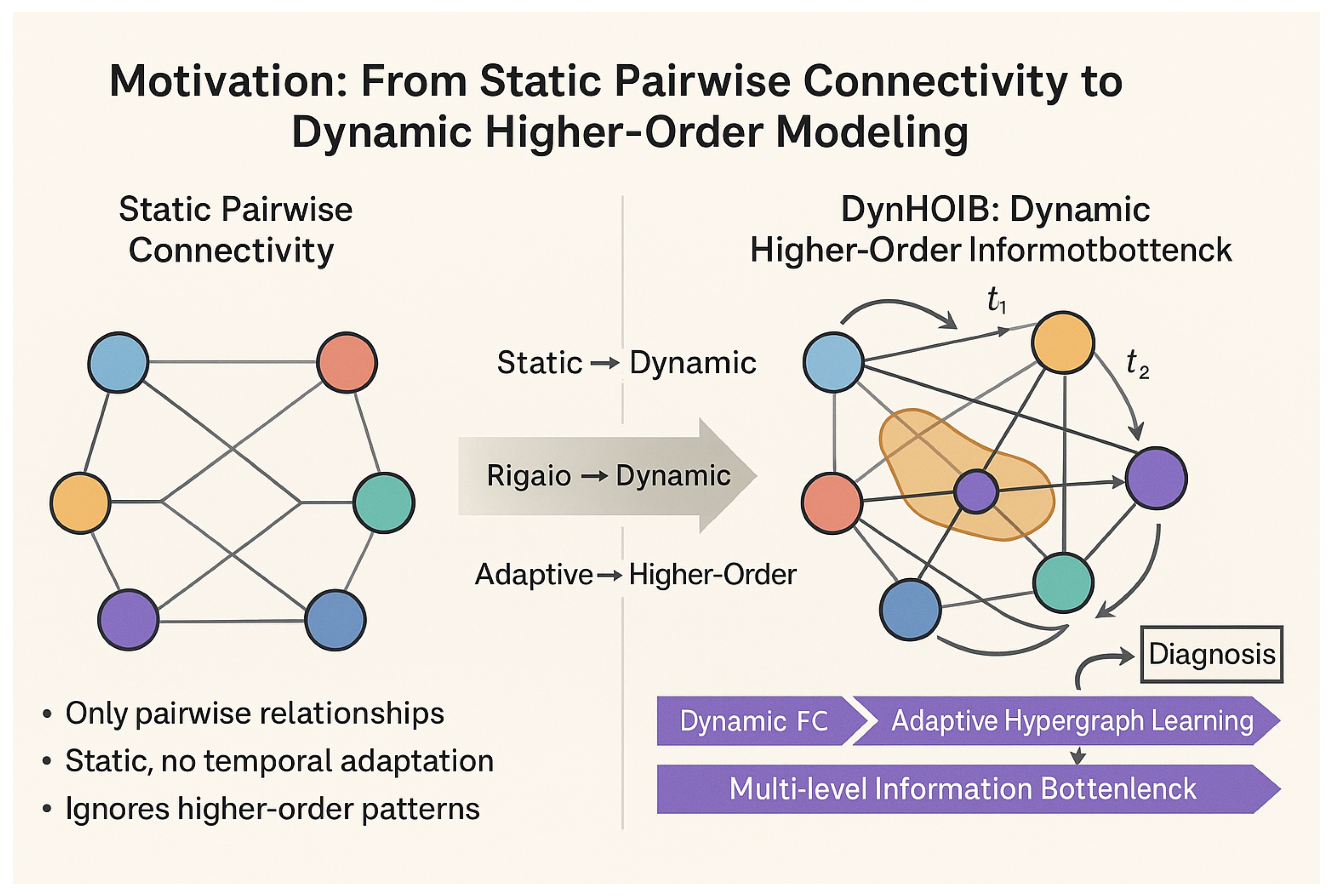

1. Introduction

- We propose DynHOIB, a novel framework that integrates dynamic higher-order interaction capture, adaptive hypergraph learning, and multi-level information bottleneck mechanisms for robust and accurate brain disease diagnosis from fMRI time series.

- We introduce a dynamic higher-order interaction generation module based on a learnable attention mechanism, capable of identifying and quantifying arbitrary-order HOIs, coupled with an adaptive hypergraph learning module for constructing time-dependent hypergraphs.

- We design a multi-level information bottleneck mechanism that performs hierarchical feature compression and fusion across different views and temporal dimensions, ensuring the learned representations are highly compact and maximally relevant to the diagnostic objective.

2. Related Work

2.1. Graph Neural Networks for Dynamic Brain Network Analysis

2.2. Higher-Order Interaction Modeling and Hypergraph Learning

3. Method

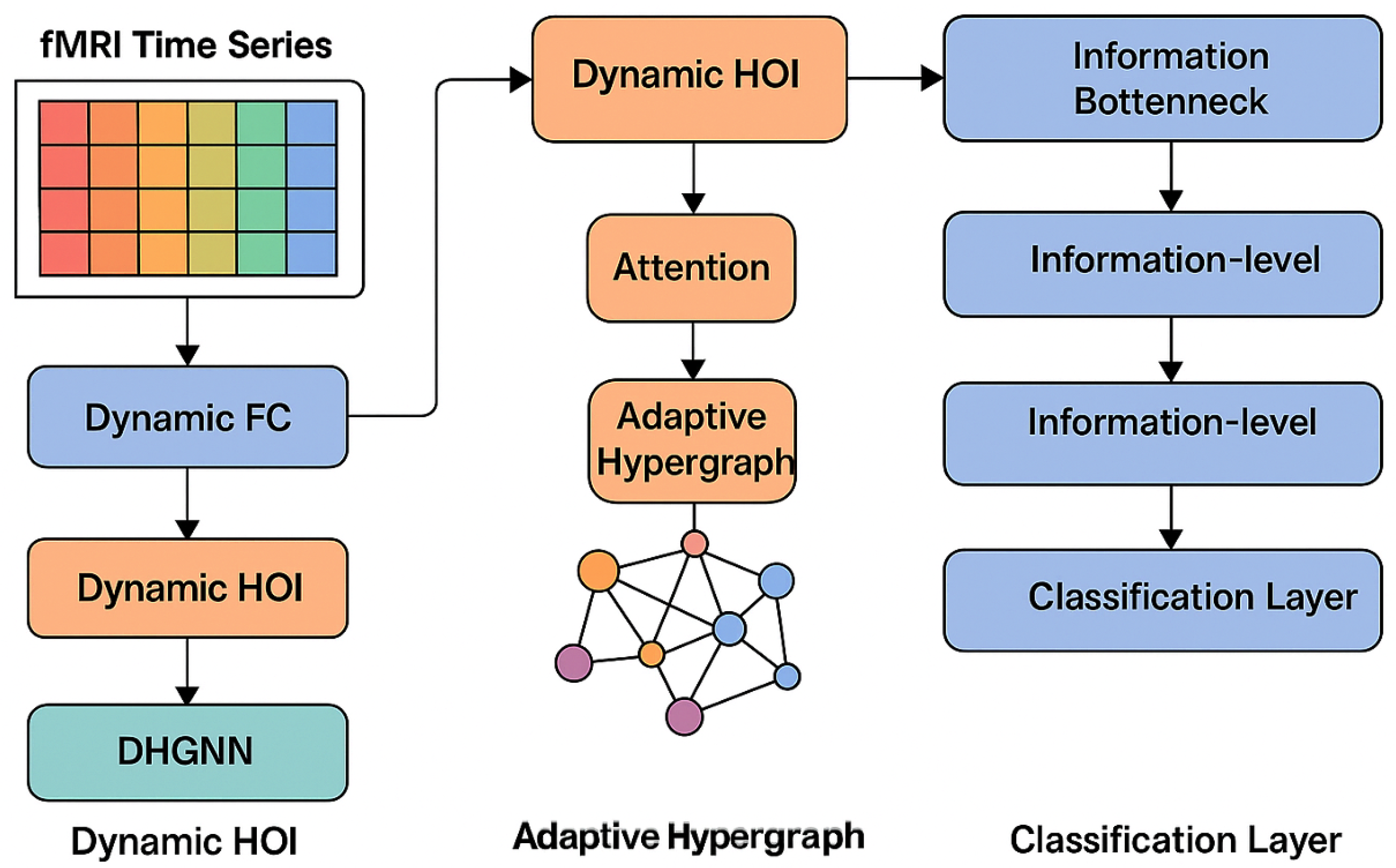

3.1. Overall Framework of DynHOIB

3.2. Dynamic Functional Connectivity Extraction and Temporal GNN

3.3. Dynamic Higher-Order Interaction Generation and Adaptive Hypergraph Learning

3.3.1. Dynamic Higher-Order Information Generator

3.3.2. Adaptive Hypergraph Construction

3.4. Dynamic Hypergraph Neural Network (DHGNN)

3.5. Multi-level Information Bottleneck Fusion

3.5.1. View-level Information Bottleneck

3.5.2. Temporal-level Information Bottleneck

3.5.3. Fusion-level Information Bottleneck

3.6. Classification Layer

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

- UCLA Dataset: This dataset is sourced from the UCLA Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics. It comprises fMRI scans for 50 subjects diagnosed with Schizophrenia (SZ) and 114 healthy control subjects (NC). The task is to accurately identify schizophrenia based on fMRI functional connectivity patterns.

- ADNI Dataset: The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset focuses on early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Our experiments utilize data from 38 subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and 37 healthy control subjects (NC). Early and accurate MCI diagnosis is crucial for intervention strategies.

- EOEC Dataset: This dataset involves 48 healthy students and is designed for brain state classification. The task is to distinguish between two fundamental brain states: Eyes Open (EO) and Eyes Closed (EC). This dataset tests the model’s ability to capture subtle dynamic changes associated with different cognitive states.

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.2.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

4.2.2. Implementation Details

4.2.3. Baseline Methods

-

Pairwise Connectivity-focused GNNs:

-

Information Bottleneck based Methods:

-

Dynamic and Multi-view Methods:

-

Higher-Order Interaction Methods:

- –

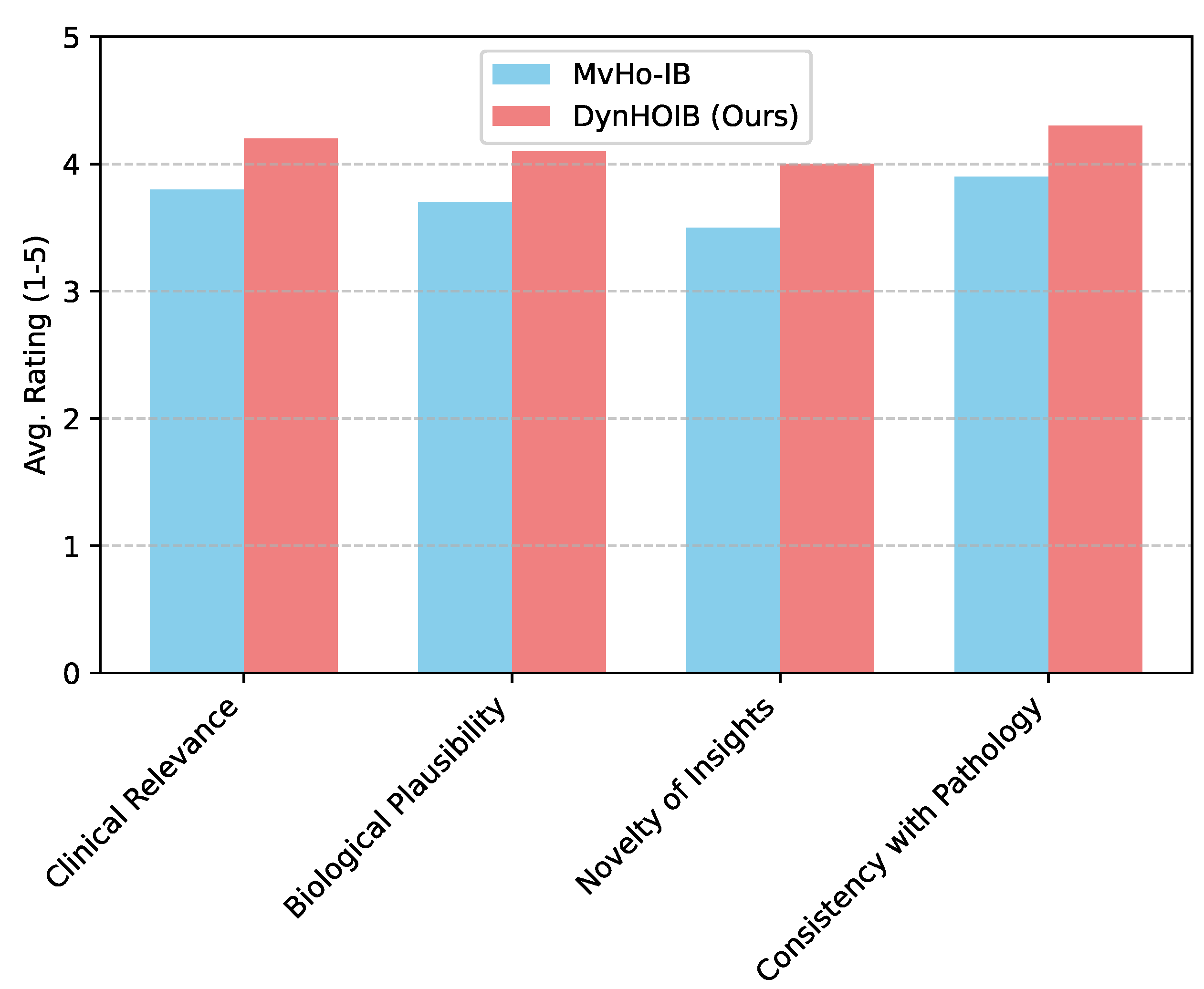

- MvHo-IB [35]: A multi-view higher-order information bottleneck method that captures static third-order O-information, representing the current state-of-the-art in higher-order brain network analysis.

4.3. Experimental Results

4.3.1. Overall Performance Comparison

4.3.2. Ablation Study

- DynHOIB w/o HOI Stream: Only the dynamic pairwise FC stream and the multi-level IB are used.

- DynHOIB w/o DHGNN (Static HOI): The dynamic HOI generator is kept, but hypergraphs are processed by a static HGNN (no recurrent units) before temporal pooling.

- DynHOIB w/o Adaptive Hypergraph: Instead of adaptive learning, we use a fixed 3rd-order O-information based hypergraph construction, similar to MvHo-IB’s HOI processing, but still dynamic.

- DynHOIB w/o Multi-level IB: All information bottleneck modules (3.5.1, 3.5.2, 3.5.3) are removed, and features are directly concatenated and classified.

- DynHOIB w/o Temporal IB: Only view-level and fusion-level IB are kept, temporal compression is done via simple pooling.

- DynHOIB w/o View IB: Only temporal-level and fusion-level IB are kept, view-level features are directly passed.

- DynHOIB w/o Fusion IB: Only view-level and temporal-level IB are kept, fused features are directly passed to classifier.

4.3.3. Interpretability through Human Evaluation

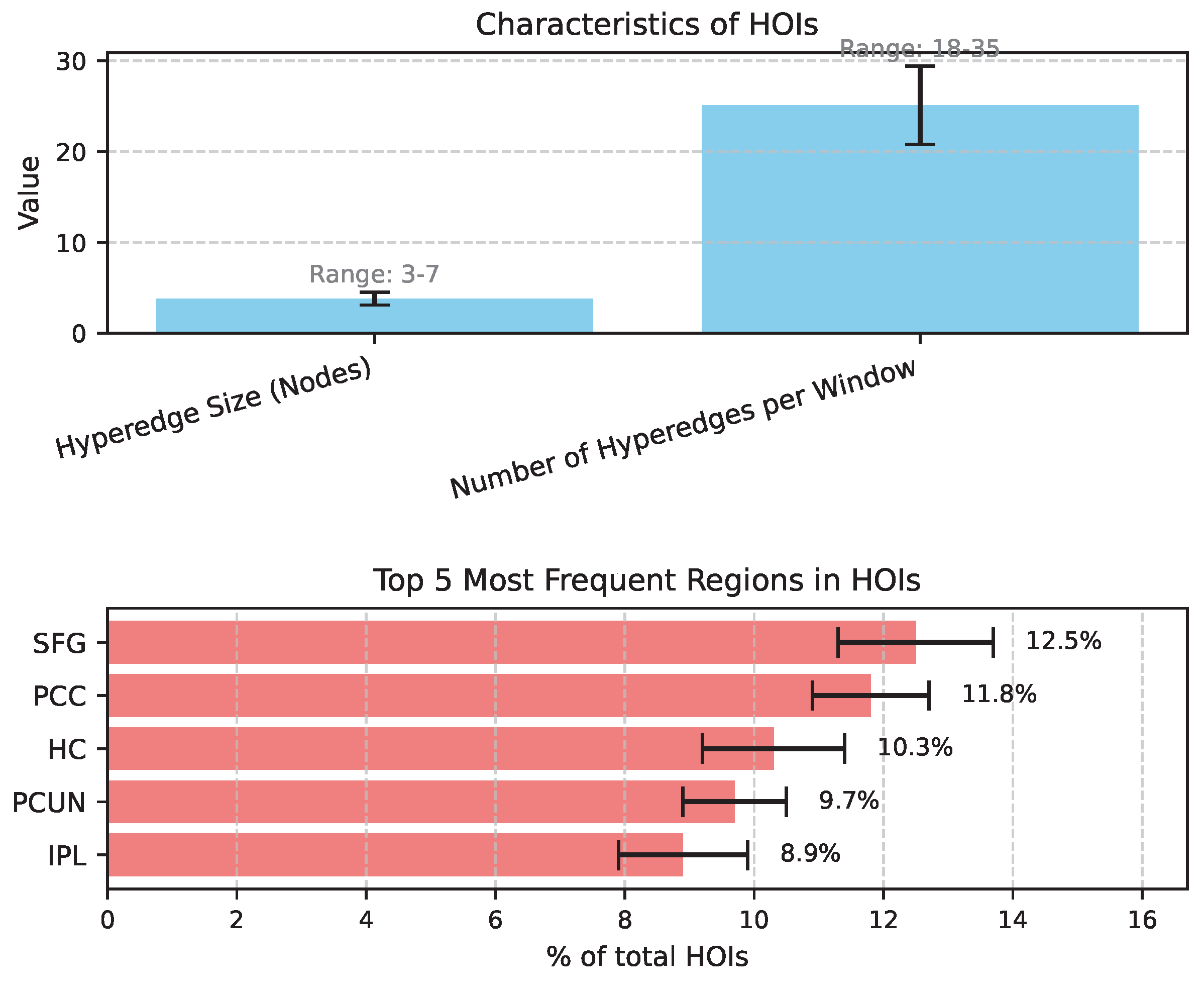

4.4. Analysis of Dynamic Higher-Order Interactions

4.5. Sensitivity to Information Bottleneck Hyperparameters

4.6. Computational Efficiency Analysis

5. Conclusions

References

- Zhou, Y.; Song, L.; Shen, J. Improving Medical Large Vision-Language Models with Abnormal-Aware Feedback. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01377. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zeng, C.; Liang, H.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J. Multimodality driven impedance-based sim2real transfer learning for robotic multiple peg-in-hole assembly. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2023, 54, 2784–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xiao, C.; Gao, G.; Sun, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Dreamarrangement: Learning language-conditioned robotic rearrangement of objects via denoising diffusion and vlm planner. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gu, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Yan, J.; Zhu, Y. Clinical Expert Uncertainty Guided Generalized Label Smoothing for Medical Noisy Label Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Mo, S.; Whittle, G. Connectivity functions and polymatroids. Adv. Appl. Math. 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Bui, T.; Mai, L.; Nguyen, A. Out of Order: How important is the sequential order of words in a sentence in Natural Language Understanding tasks? In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Q.; Yu, S. MvHo-IB: Multi-view Higher-Order Information Bottleneck for Brain Disorder Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer; 2025; pp. 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.; Xue, Y.; Yan, Z.; Huang, W.; Feng, J. Dynamic and Multi-Channel Graph Convolutional Networks for Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Multimodal Fusion with Co-Attention Networks for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2560–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhi, G.; Jin, L. Trigger is not sufficient: Exploiting frame-aware knowledge for implicit event argument extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2021; pp. 4672–4682. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Qi, P.; Wang, G.; Ying, R.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Zhou, B. Graph Ensemble Learning over Multiple Dependency Trees for Aspect-level Sentiment Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2884–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X. ConUMIP: Continuous-time dynamic graph learning via uncertainty masked mix-up on representation space. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 306, 112748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Z.; Nye, M.; Andreas, J. Implicit Representations of Meaning in Neural Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Miao, H.; Jiang, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y. STRAP: Spatio-Temporal Pattern Retrieval for Out-of-Distribution Generalization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19547. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Che, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Hu, G.; Liu, T. Dynamic Connected Networks for Chinese Spelling Check. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, G.; Song, Y.; Wan, X. Dependency-driven Relation Extraction with Attentive Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4458–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, X. IMCSN: An improved neighborhood aggregation interaction strategy for multi-scale contrastive Siamese networks. Pattern Recognition 2025, 158, 111052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, W.; Hu, S. Label-Specific Dual Graph Neural Network for Multi-Label Text Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 3855–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Gong, Y.; Liu, D.; Wei, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiao, J.; Duan, N.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X. Mask Attention Networks: Rethinking and Strengthen Transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yi, R.; Zhu, Y.; Rehman, A.; Zadeh, A.; Poria, S.; Morency, L.P. MTAG: Modal-Temporal Attention Graph for Unaligned Human Multimodal Language Sequences. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.; Liang, D. A Novel Virtual Flux Linkage Injection Method for Online Monitoring PM Flux Linkage and Temperature of DTP-SPMSMs Under Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.; Feng, Z. Virtual Back-EMF Injection-based Online Full-Parameter Estimation of DTP-SPMSMs Under Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Feng, Z. Novel Virtual Active Flux Injection-Based Position Error Adaptive Correction of Dual Three-Phase IPMSMs Under Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Xie, H. UniRel: Unified Representation and Interaction for Joint Relational Triple Extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 7087–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Jin, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J. Chain-of-specificity: Enhancing task-specific constraint adherence in large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2025; pp. 2401–2416. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Y.; Jin, L.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhi, G. Guide the many-to-one assignment: Open information extraction via iou-aware optimal transport. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2023; pp. 4971–4984. [Google Scholar]

- Tran Phu, M.; Nguyen, T.H. Graph Convolutional Networks for Event Causality Identification with Rich Document-level Structures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 3480–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Wei, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Xie, X.; Quek, T.Q. Heterogeneity-aware high-efficiency federated learning with hybrid synchronous-asynchronous splitting strategy. Neural Networks 2025, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, S.C.; Zhang, J. Ehoa: A benchmark for task-oriented hand-object action recognition via event vision. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024, 20, 10304–10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Jia, R.; Hupkes, D.; Pineau, J.; Williams, A.; Kiela, D. Masked Language Modeling and the Distributional Hypothesis: Order Word Matters Pre-training for Little. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2888–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cui, L.; Shang, J.; Wei, F. LayoutReader: Pre-training of Text and Layout for Reading Order Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4735–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, K.; Khattab, O.; Saad-Falcon, J.; Potts, C.; Zaharia, M. ColBERTv2: Effective and Efficient Retrieval via Lightweight Late Interaction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 3715–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Q.; Yu, S. MvHo-IB: Multi-view Higher-Order Information Bottleneck for Brain Disorder Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2025 - 28th International Conference, Daejeon, South Korea, September 23-27, 2025, Proceedings, Part XV. Springer; 2025; pp. 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | UCLA (%) | ADNI (%) | EOEC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | 62.27 ± 6.21 | 66.13 ± 4.62 | 70.92 ± 8.56 |

| GAT | 67.73 ± 7.61 | 66.28 ± 8.69 | 72.73 ± 8.64 |

| GIN | 65.91 ± 8.21 | 68.33 ± 6.47 | 75.41 ± 9.65 |

| DIR-GNN | 75.72 ± 8.37 | 70.63 ± 6.96 | 80.12 ± 6.21 |

| SIB | 72.76 ± 8.13 | 70.12 ± 7.43 | 80.42 ± 7.97 |

| BrainIB | 79.14 ± 4.17 | 72.47 ± 5.32 | 82.06 ± 5.43 |

| HYBRID | 79.38 ± 8.34 | 71.34 ± 7.43 | 81.97 ± 7.43 |

| MHNet | 79.22 ± 6.72 | 71.96 ± 4.96 | 82.87 ± 5.43 |

| MvHo-IB | 83.12 ± 5.74 | 73.23 ± 4.37 | 82.13 ± 6.96 |

| DynHOIB (Ours) | 83.85 ± 4.98 | 73.91 ± 3.82 | 82.67 ± 6.15 |

| Method Variation | ADNI (%) |

|---|---|

| DynHOIB (Full Model) | 73.91 ± 3.82 |

| DynHOIB w/o HOI Stream | 70.88 ± 4.15 |

| DynHOIB w/o DHGNN (Static HOI) | 71.52 ± 4.01 |

| DynHOIB w/o Adaptive Hypergraph | 72.19 ± 3.95 |

| DynHOIB w/o Multi-level IB | 69.45 ± 5.23 |

| DynHOIB w/o Temporal IB | 72.53 ± 3.77 |

| DynHOIB w/o View IB | 72.88 ± 3.69 |

| DynHOIB w/o Fusion IB | 73.15 ± 3.74 |

| Configuration | ADNI Accuracy (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Compression | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 71.22 ± 4.11 |

| Optimal Configuration | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 73.91 ± 3.82 |

| High Compression | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 70.15 ± 4.56 |

| Method | Avg. Training Time per Epoch (s) | Avg. Inference Time per Subject (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| GCN | 0.82 | 12.3 |

| DIR-GNN | 1.55 | 25.7 |

| BrainIB | 1.10 | 18.9 |

| MvHo-IB | 2.15 | 35.2 |

| DynHOIB (Ours) | 2.87 | 48.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).