1. Introduction

The multi-soft robot collaboration system has become a key paradigm for performing complex operational tasks in a constrained environment. Its applications cover industrial maintenance, precision manufacturing and minimally invasive surgery [

1]. Compared with traditional rigid robot operating arms, soft robots have stronger adaptability and are more suitable for unstructured operating environments. However, in the multi-arm collaborative scenario, the inherent flexibility of the multi-robot system makes it extremely prone to entanglement and jamming. This kind of topological deadlock mainly comes from global constraints rather than local geometric collisions, which may lead to system failure, reduced operational efficiency and safety hazards, and has become an important obstacle to the reliable deployment of multi-soft robots. Therefore, this article is committed to developing an efficient multi-soft robot coordination framework suitable for complex environments.

With the advancement of multi-soft robot collaboration research, the academic community has proposed a variety of system solutions for multi-soft robot collaboration, including paradigms based on dynamic motion planning, imitation learning and multitask reinforcement learning. In the field of traditional motion planning, sampling-based algorithms such as RRT* [

2] and optimization-based methods [

3] show progressive optimization in geometric path search, but these methods are essentially reactive methods, relying on the instantaneous environmental state and lack explicit modeling of the history of system motion.

Such methods usually decouple trajectory planning from tracking control [

4], ignoring the inherent nonlinear dynamic characteristics of soft robots, and hindering the maintenance of topological security in the real-time control process. Especially in a dynamic uncertain environment, it is difficult for traditional methods to respond to mobility obstacles and self-deformation in real time, which makes online re-planning to maintain topological security challenging.

In the field of multi-intelligence reinforcement learning, although the centralized training with decentralized execution framework [

5] provides a new paradigm for collaborative control, the centralized method is false. There is a core service provider, which masters the global information of all intelligent bodies (such as status and observations) and decides on the behavior of intelligent bodies, and generates global control instructions based on system-wide observations to ensure security, integrity and optimality. At present, the realization of centralized training combined with the distributed execution framework still faces many challenges: affected by the non-stableness of the multi-intelligent system, the existing value function decomposition method [

6] is difficult to accurately trace the long-term historical action sequence that leads to entanglement; in some observable environments, decision-making rules based only on local observation cannot be comprehensive. Evaluate the risk of system-level topology, and the combination explosion of joint action space further exacerbates the complexity of strategy optimization.

Special attention should be paid to the current Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) technology relies heavily on instantaneous collision punishment or security barriers [

7], which cannot effectively alleviate the expansion of cumulative effects and lag. Fight the risk. In addition, theoretical analysis shows that value-based multi-intelligent reinforcement learning algorithms cannot guarantee convergence to stable Nash equilibrium in general scenarios and game theory environments, so its stability in actual deployment scenarios is doubtful.

At present, the application of topology in the field of robotics is mostly limited to offline analysis and backtracking verification [

8], which fails to take topological invariants as an integral part of the real-time decision-making process. This design paradigm that decouples topological security from the control loop weakens the system’s ability to actively identify potential entanglement risks, thus threatening the realization of basic security in the process of dynamic operation. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a new method for embedding topological perception depth into the learning and decision-making process to solve the inherent topological security challenges in the collaborative control of multi-soft robots.

In view of the above limitations of existing research, this paper proposes an innovative topological perception multi-intelligence enhanced learning framework. By explicitly integrating topological constraints into the whole process of learning and decision-making, we can realize the active prevention and control of entanglement risks. TA-MARL integrates organically coupled collaborative learning mechanism: by introducing time-state modeling, it captures the dynamic evolution mode of topological configurations and provides key historical dependencies for the collaborative control of heterogeneous intelligent bodies; at the same time, the trust domain constraint optimization strategy is adopted to ensure the stability of the learning process in the complex strategy space. By separating the security trajectory and the high-risk trajectory, the sample efficiency of the intelligent body learning process is significantly improved; a hierarchical incentive framework that integrates the topological perception reward mechanism and action shielding is developed to realize the collaborative optimization of task performance and topological security.

The contribution of this article is summarized as follows:

A topological perception multi-intelligent body reinforcement learning framework is proposed to realize the paradigm shift from "geometric avoidance" to "topological anti-entanglement"; the innovative hierarchical control architecture based on the topological isolation experience playback mechanism solves the limitations of traditional methods of ignoring movement history and effectively prevents entanglement problems.

Real-time quantitative evaluation based on topological invariance can be realized, and the risk of winding can be perceived and measured at the millisecond level; through strict convergence and sample complexity analysis, the stability and efficiency of the proposed algorithm can be theoretically guaranteed.

Develop a security intervention layer that integrates dynamic concurrent control and real-time action suppression to ensure the robustness and generalization of the system in complex scenarios; the enhanced design gives the system active risk management capabilities, including early warning and autonomous mitigation of potential threats.

The follow-up structure of this article is arranged as follows:

Section 2 discusses the relevant work;

Section 3 explains the problem modeling and basic definition;

Section 4 introduces in detail the topological perception multi-intelligent enhanced learning framework and its core components;

Section 5 evaluates the algorithm performance through comprehensive simulation and melting experiments;

Section 6 summarizes the research work and discusses Direction;

Section 6 provides theoretical proof of topological invariance and system stability at the same time.

2. Related Work

This research focuses on the winding problem in multi-soft robot collaboration, and integrates soft robot technology, topological analysis and multi-intelligence reinforcement learning. Although progress has been made in all fields, there are still a lot of gaps in the study of integrating topological perception into multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) in physical systems.

In the field of soft robot control, relevant methods have been developed from physics-based models (such as Cosserat rod theory [

9,

10], finite element method) to descending models (such as piecewise constant Curvature approximation [

11]). In recent years, reinforcement learning technology has been effectively used to deal with nonlinear dynamics problems of soft robots [

12,

13]. However, when expanding to multiple robot systems [

14,

15], the existing methods mostly focus on local geometric coordination and Euclidean space avoidance, ignoring the cumulative risks of global topological constraints and entanglement.

In the field of robotics, topological methods are traditionally used as offline analysis tools. In the early applications, the braid theory was used for multi-robot path planning [

8], and the linking number [

16], Gaussian integral linking [

17] and other invariables provide a mathematical framework for quantitative winding. In recent years, real-time topology computing technology has been developed and applied to knot tracking [

18], sensor network analysis [

19] and other scenarios. Nevertheless, topology is often regarded as a constraint rather than an active control signal, limiting its utility in the dynamic operating environment.

In the field of multi-intelligence reinforcement learning, MADDPG [

20], MAPPO [

21] and other frameworks solve the problem of non-stability through centralized training combined with distributed execution. Subsequent improved versions such as R-MAPPO [

22] and HAPPO [

23] have further improved the ability of time reasoning and heterogeneous synergy. Security design mostly focuses on collision avoidance and constraint satisfaction [

13,

24], which is usually implemented through punishment functions or security barriers, but these methods often ignore the accumulation and historical dependence of topological winding risks.

In summary, although independent progress has been made in the fields of soft robot control, topology analysis and multi-intelligent reinforcement learning (MARL), it is still an unsolved challenge to actively integrate topological invariants into the MARL framework to alleviate the entanglement problem. This research aims to fill this gap by embedding topological invariants as an active control signal to strengthen the learning paradigm.

3. Problem Statement

In constrained environments such as short cabins of aircraft engines and automobile chassis, multi-robot systems often have topological winding and knotting phenomena that traditional motion planning algorithms cannot solve. This kind of failure mode with global characteristics and dependence on historical status may cause system deadlock, mission failure or mechanical damage. In order to alleviate such problems, this paper proposes an advanced control framework: by constructing a high-dimensional mixed state space that integrates topological invariances, geometric parameters and task-specific states, and introduces topological perception capabilities; this method embeds topological constraints into the multi-intelligence body reinforcement learning architecture, which can realize the entanglement while ensuring operational efficiency. Real-time detection and mitigation of risks.

3.1. Assumptions

This paper studies the coordination problem of multi-soft robot operating arms to perform maintenance tasks in a constrained environment. Each operating arm needs to generate a collision-free trajectory and complete the assigned maintenance tasks within the specified time window. At the same time, it should abide by the boundaries of the geometric workspace to avoid topological entanglement with environmental obstacles or other operating arms. This problem can be modeled as a distributed workshop scheduling and motion planning framework with topological constraints: the maintenance process is predetermined and executed by heterogeneous robot intelligence, and the global topology state is the key safety indicator.

In order to facilitate analysis, the following basic assumptions are set:

The task priority relationship is represented by a directed acyclic graph (DAG), and any available operating arm can perform each task;

The duration of each maintenance process is determined by the minimum operating speed, which is a fixed value and is not affected by the kinematic configuration of the operating arm;

It is assumed that there is a robust control strategy, which can alleviate the impact of sudden dynamic obstacles and prevent the sudden failure of the drive device during operation;

The sensors used for shape reconstruction and positioning are highly reliable, and the communication infrastructure supports the real-time calculation of the global topology state.

3.2. Fundamental Definitions

This paper proposes a topological perception state coding method: constructing an integrated state manifold by integrating geometric invariants, task-related parameters and topological invariants. This coding method can realize the real-time assessment of the winding risk and provide accurate posture perception for the collaborative control of the multi-soft robot operating arm in the constrained operation environment.

The key components of the collaborative system are defined as follows:

Definition 1: Geometric Kinematic State of the Robots

The kinematic state of the robotic arm is characterized by its homogeneous transformation matrix, which comprehensively delineates the spatial configuration of each joint:

Where N represents the total number of robotic manipulators, denotes the number of kinematic nodes in the j-th manipulator, is the positional vector at parameter , is the linear velocity vector, is the orientation transformation matrix, and represent the curvature components along their respective principal axes.

Definition 2: Workplace Spatial Configuration

The operational environment of the robotic manipulator system is defined as:

Where K is the total number of tasks, specifies the operational workspace, denotes the positional vectors of the k-th target point, and represents the set of stationary obstacles, where is the centroid of each obstacle, and is the radius of each obstacle.

Definition 3: Topological Knotting Depiction

The topological entanglement framework incorporates various metrics to assess entanglement risks and provide early warnings of potential hazards. These metrics are formally defined as:

The computation and proof of topological invariants are detailed in Appendices A–C.

Definition 4: Work Task Scheduling Optimization

The system dynamically allocates robotic manipulator resources based on task progression and process data, formally defined as:

Where represents the complete set of maintenance protocols for the equipment, is the progress vector for operational tasks, is the temporal dependency graph modeled as a directed acyclic graph, and is the task allocation tensor.

3.3. Objective Function and Constraints

This study formalizes the system constraints as hard boundaries within policy optimization, while incorporating soft penalty terms into the reward function. The ultimate goal is to minimize the likelihood of entanglement among robotic arms during the execution of specified tasks:

C1: Positional Kinematic Constraints Ensure a minimum safety distance between the robotic arm and obstacles, such that , with all nodes confined within the workspace .

C2: Velocity-Dependent Boundary Constraints Limit the velocity of each node to , thereby guaranteeing the dynamic stability of the system.

C3: Posture-Dependent Kinematic Constraints Restrict the curvature of bending , as well as torsional curvature and total arc length, to prevent structural failure and maintain geometric integrity.

C4: Temporal Precedence in Task Scheduling Tasks must be executed in the order specified by the directed acyclic graph (DAG): , where .

C5: Task Scheduling Constraints Ensure that each task is assigned to only one robotic arm and that each robotic arm executes only one task at a time, to avoid resource conflicts.

4. Methodology

4.1. Algorithm Framework

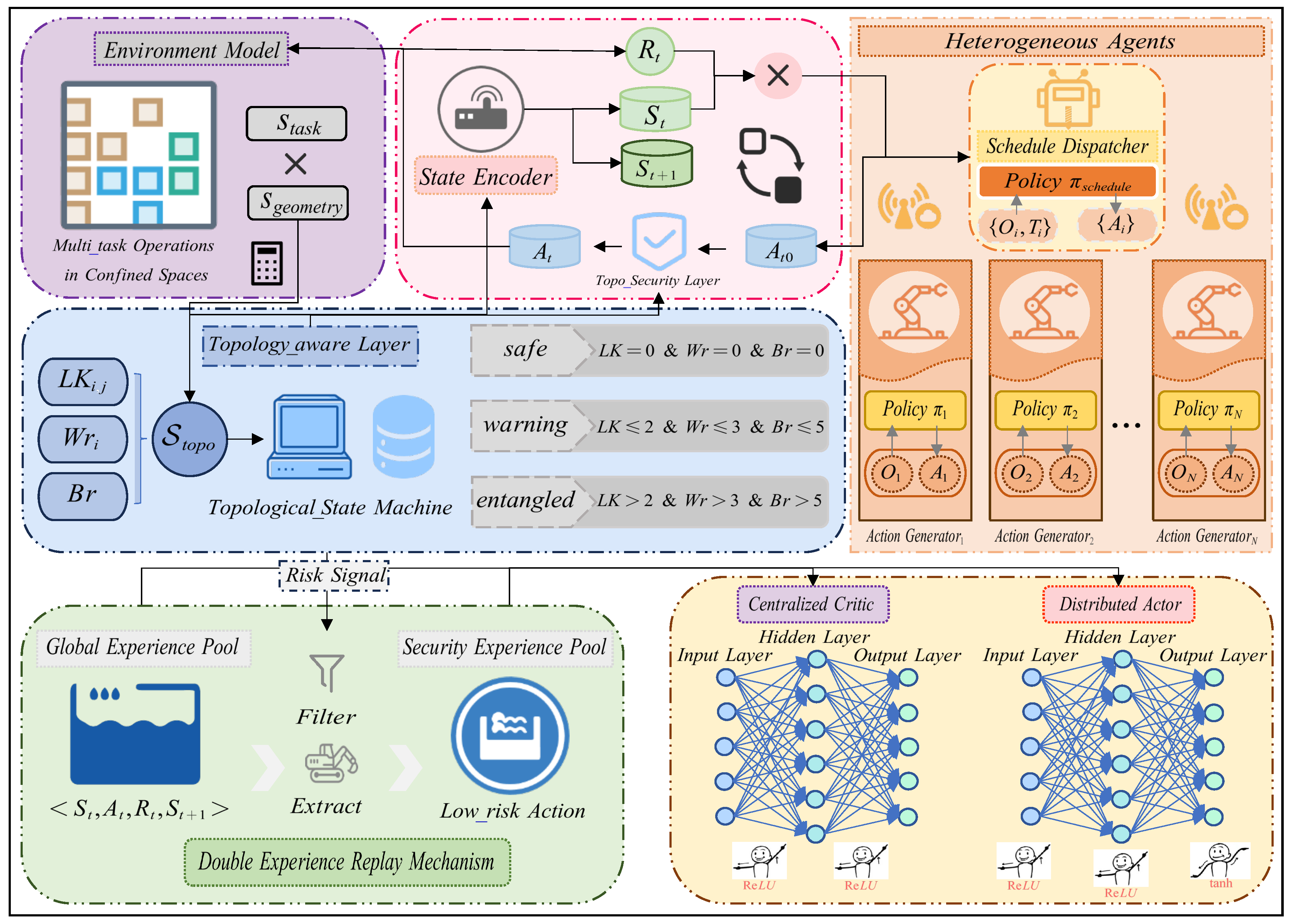

As shown in

Figure 1, the proposed collaborative control framework takes a hierarchical structure, containing two components: strategy dispatcher for overall scheduling; dedicated manipulators for running local paths. Topological invariant was incorporated into the representation of states as well as the update rule for the reinforcement learner, and the potential entanglement risk during the course of the manipulation task could be estimated online based on the integration between geometrical features and topological features.

The key algorithm, in combination with the idea of the strategy gradient method, adds trust region constraints to guarantee the stability and controllability of the policy iteration. And the key innovation point of this paper is the dynamic concurrency control mechanism: according to the online topology hazard evaluation results, respectively adjust the excitation level of operation arms, so that the system can work under full load in a safe environment, or reduce deployment scale facing coiling hazard.

According to the above analysis results, we introduce topology-aware experience playback and preemptive security verification, so that the framework can directly integrate topology perception into decision-making. The two-stage playback mechanism balances the trade-off between operation efficiency and important security experience considerations such that it achieves effective anti-replay capability under the restricted context but does not impair the task execution outcome.

4.2. Topology Awareness and Safety Intervention Mechanisms

In the paradigm of multi-intelligent reinforcement learning, how to update the policy network is greatly affected by the exploration strategy in a high-dimensional configuration space. Traditional methods only rely on independent empirical learning, and it is difficult to effectively identify complex topological entanglement risks. This limitation is particularly prominent in dynamic constrained environments. In order to solve this core challenge, this paper innovatively builds an a priori knowledge base based on algebraic topology theory, and transforms complex spatial configurations into computable topological features through homogeneous invariants. The core innovation of this framework lies in the introduction of three precise topological invariant quantification mechanisms:

-

Simplified Braid Word Length (): By projecting the movement of the multi-robot system into a braid group and simplifying it to the minimum standard form, its length can directly measure the topological complexity and intertwining process of the system movement. Degree. See Algorithm 1 for the specific calculation process.

-

Linking Number (Lk): Accurately quantifies the degree of interlocking between robotic arms using Gaussian integral calculations. Mathematically, it is expressed as:

This invariant remains strictly unchanged under environmental isotopies, providing a reliable theoretical basis for entanglement detection.

Self-Entanglement Degree (Wr): Evaluates the propensity of a single robotic arm to self-entangle by calculating the self-winding integral along its centerline. Mathematically, it is expressed as:

Based on these rigorous mathematical definitions, we design a topological risk scoring function:

4.3. Theoretical Framework of Dual Experience Replay and Topological Value Learning

At the theoretical level, this framework establishes a rigorous formal analysis structure that provides theoretical guarantees for topology-aware reinforcement learning. We first define the effective state space as:

This definition partitions the state space into safe and hazardous regions, laying the foundation for subsequent theoretical analysis.

Based on this, we derive an upper bound on the sample complexity:

This bound indicates that by restricting exploration to the effective state space, the algorithm’s complexity can be reduced by approximately , where represents the proportion of haz- ardous states. This theoretical result validates the advantage of the dual experience replay mechanism in enhancing sample efficiency.

Furthermore, we conduct a theoretical analysis based on the entanglement rate convergence theorem(The detailed proof process is provided in Appendix E):

Analysis shows that the dual experience playback mechanism increases the topological penalty coefficient by about 20% per unit by increasing the number of effective strategy updates, thus improving sample efficiency. This theoretical cognition quantifies the impact of parameter tuning on the convergence speed of the algorithm.

4.4. Hierarchical Coordination Architecture of Heterogeneous Intelligent Agents

4.4.1. Hierarchical Design and Cooperative Optimization Mechanism

Layered design is one of the core innovations of this architecture. The scheduler agent is specially responsible for global task allocation and resource management. Its network structure is designed to handle complex system-level status information; the intelligence adopts Long Short-Term Memory network (Long Short-Term Memory, LSTM) models the time evolution process of topological configurations and effectively captures the historical dependencies of topological constraints. The robotic arm agents focus on local trajectory optimization and obstacle avoidance. Its network architecture is customized according to the needs of continuous control action space, and ensures the stability of policy updates through trust domain constraints (Appendix D).

Two types of intelligent bodies achieve in-depth collaborative optimization through carefully designed hierarchical reward functions: the reward function of the scheduler is designed as follows:

This function scientifically incentivizes the optimization of system-level performance metrics, with the topological penalty term

ensuring adherence to system safety constraints. The robotic arm’s reward function is:

which precisely guides the agents to accomplish detailed local tasks. This hierarchical reward design mathematically guarantees the alignment of individual objectives with the overall system goals.

The two types of intelligent bodies achieve implicit collaboration by sharing the global topology state: the communication protocol adopts the publish-subscribe architecture, the scheduler regularly releases the global task allocation and topology state summary, and the operator arm subscribes to the information and gives feedback. Local state. This design minimizes communication overhead while ensuring real-time coordination and conflict resolution. The deep integration of the security obstacle avoidance mechanism in the hierarchical architecture is reflected in multiple levels: the topological security layer screens actions in real time to prevent high-risk operations; the dual-experience playback mechanism gives priority to learning the security trajectory; the regularization item punishes the intervention of dangerous actions to maintain strategic consistency.

4.4.2. Dynamic Concurrent Control Mechanism

The dynamic concurrent control mechanism is another core innovation of this architecture, which realizes intelligent system resource allocation through real-time topological state perception. The system adjusts the number of operating arms concurrently based on the precise calculation of the length of braids:

where

is the concurrency decay factor, and

and

define operational boundaries. This innovative design allows the system to automatically degrade performance under high-risk conditions to ensure absolute safety, while fully leveraging maximum performance under safe conditions.

To further optimize the trade-off across different time scales, a dynamic discount factor mechanism is implemented:

According to the topological security status, the mechanism intelligently adjusts the preferences of the intelligent body between short-term security and long-term income, and significantly improves the quality of decision-making from the perspective of mathematical optimization: in the safe state, the higher discount factor promotes the intelligent body to give priority to long-term task rewards; when the winding risk is detected, the reduction of the discount factor guides its focus, that is Time is safe.

The deep integration of concurrent control and topological perception realizes the adaptive balance of system performance and security. Through real-time monitoring of topological invariants such as the number of surrounds, the length of braids, the degree of self-winding, etc., the system can predict the potential winding risk and actively implement obstacle avoidance strategies. This forward-looking control method not only avoids the inherent lag of reactive control, but also significantly improves the robustness and reliability of the overall system.

5. Experimentation

This research explores the topological complexity of multi-robot collaboration in a high-obstacle density environment, proposes a topological perception multi-intelligent enhanced learning architecture, and strictly verifies the effectiveness of the proposed method in a variety of operation scenarios through a large number of computational simulation.

5.1. Simulation Environment Setup

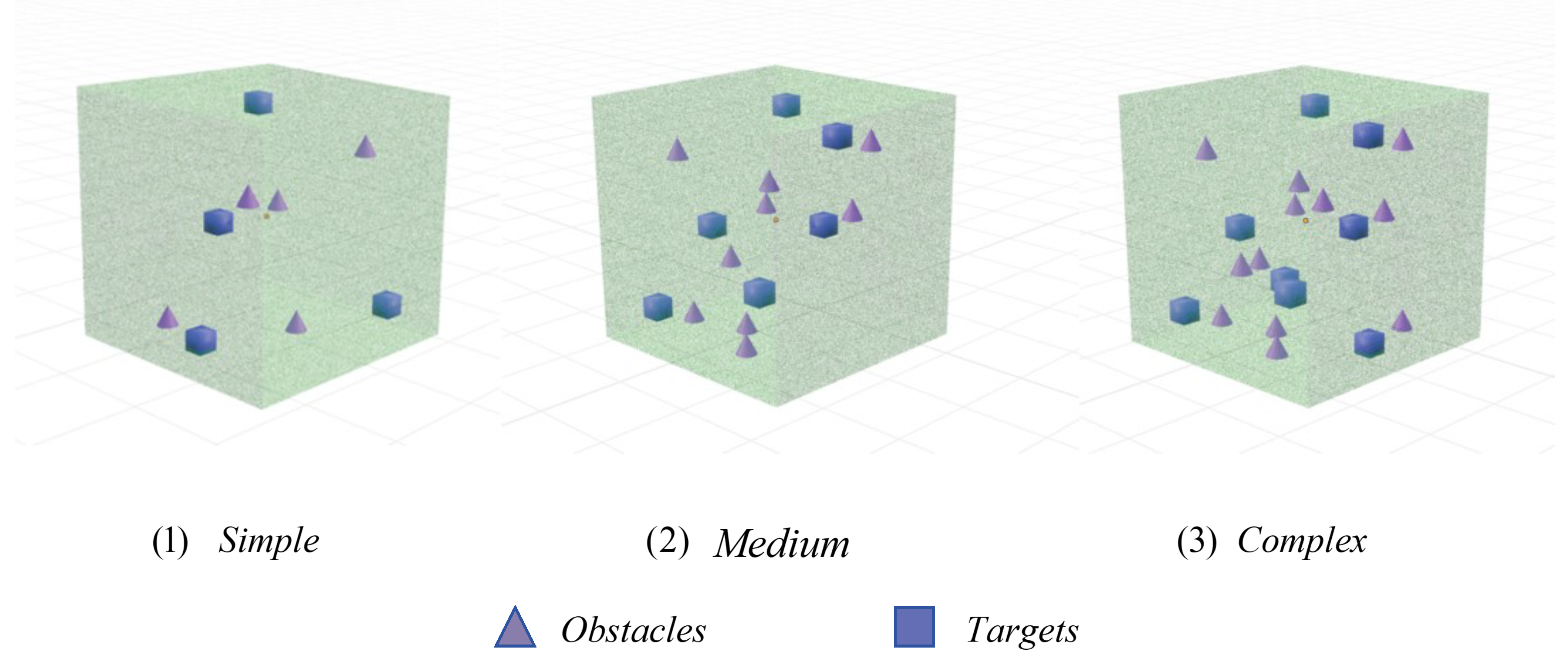

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the topological perception multi-intelligent enhanced learning framework, this research has developed a high-fidelity multi-soft robot operating arm collaborative control simulation platform to model industrial scenarios with spatial constraints such as aircraft engine short compartments and automobile chassis. The research has designed three environment configurations with increasing complexity (see

Figure 2) to systematically evaluate the algorithm performance:

Simple Scenario:4 operating arms operate at 4 designated points in a low obstacle density environment to provide benchmark reference for the basic coordination ability.

Medium Scenario:6 operating arms navigate and operate around 6 target points in a medium obstacle distribution environment, introducing moderate coordinated challenges and collision avoidance constraints.

Complex Scenario:10 operating arms operate at 8 target points in a high-obstacle density environment to test the system’s complex multi-intelligent body coordination ability under strict spatial restrictions.

The simulation environment integrates static structural obstacles and dynamic operation constraints, and requires the adoption of advanced trajectory planning and real-time collision avoidance strategies. Under the control of the global dispatcher, each operating arm needs to perform complex and timely tasks in an orderly manner, while keeping a safe distance from obstacles and other operating arms. Task configuration includes different degrees of complexity and duration. The specific parameters are shown in

Table 1; the parallel task execution process is shown in

Table 2, reflecting the typical concurrency of industrial automation systems.

The core evaluation index is the system’s ability to achieve a high task completion rate while avoiding the physical entanglement of the operating arm. By comparing the easy-to-wind benchmark method with the non-collision topology perception method under the same task conditions, the validity of the proposed framework is quantitatively verified.

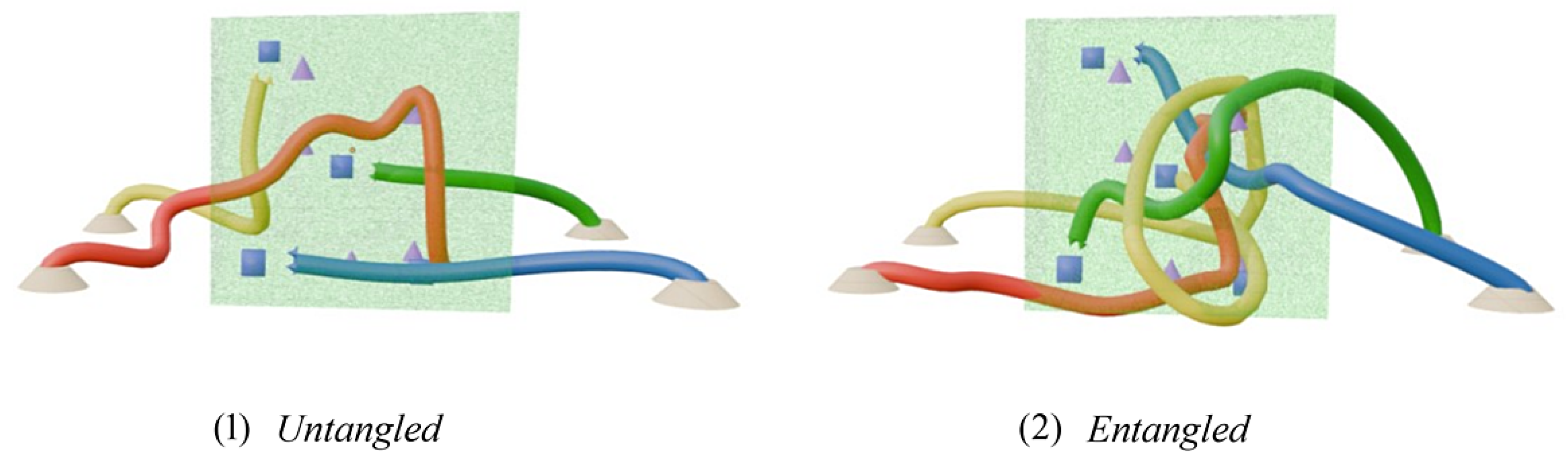

Figure 3 shows the typical scenarios of winding and no winding operation, and visually presents the practical advantages of topological perception strategies in a high barrier density environment.

5.2. Experimental Setup

In order to compare the effectiveness of the proposed method with the existing research, this study analyzes four types of benchmark algorithms:

RRT* + Greedy Algorithm:Realizes the progressive optimal planning of the geometric path through probability sampling. The greedy module is responsible for instant task allocation, only sets the lower performance limit according to the geometric data, does not consider topological constraints, and cannot detect or avoid multiple operations. Entanglement caused by the cumulative movement of the arm.

MAPPO Series Algorithms:Our focus encompasses the standard MAPPO and HAPPO. The former uses a centralized training-distributed execution architecture to alleviate the instability of the multi-intelligent body system and provide a stable benchmark for collaborative learning; the latter introduces sequential strategy updates to improve the heterogeneous management ability of the intelligent body and improve the synergy effect of operating arms with different kinematic characteristics under the multi-operation arm configuration.

MASAC Series Algorithms:MASAC promotes stable exploration of complex environments by maximizing expected returns and entropy values; MAAC strengthens intelligent inter-body communication with attention mechanism to improve the efficiency of multi-operator arm information interaction; FACMAC improves sample efficiency and scalability by decoupling the centralized commenter architecture.

MADDPG Series Algorithms:MADDPG Series Algorithms: Evaluate the basic MADDPG and QDDPG. The former adopts a centralized commenter-distributed actuator architecture to provide a stable learning framework for continuous action space; the latter introduces centimal regression technology and discrete value functions to stabilize training and improve performance.

In order to ensure the fairness of the comparison, all algorithms are configured with the same hyperparameters, and the efficiency is maximized by system tuning. The complete parameter specifications are shown in

Table 3.

5.3. Performance Comparative Analysis

All experiments are carried out under controlled environmental parameters, and the validity of the proposed algorithm and benchmark model is evaluated with the following indicators:

Winding Incidence Rate:The frequency of winding events confirmed by topological diagnosis is the core index of topological integrity and security.

Safety Intervention Rate:The probability of the topological safety layer actively intervening and replacing dangerous actions in decision-making, reflecting the real-time risk mitigation ability of the system.

Task Completion Rate:The proportion of target tasks successfully performed within the preset time window, and directly quantify the basic operation efficiency of the algorithm.

Robot Idle Rate:The ratio of running time in the inactive state of a single operating arm to evaluate system-level resource allocation and collaborative efficiency.

Evaluation Reward:The model accumulates total rewards per round in the independent test environment, and comprehensively measures the strategy’s ability to balance between task performance, action cost and security constraints.

Convergence Time:The time required to evaluate the reward and stabilize at 95% of the asymptotic performance in training, reflecting the convergence speed of algorithm learning.

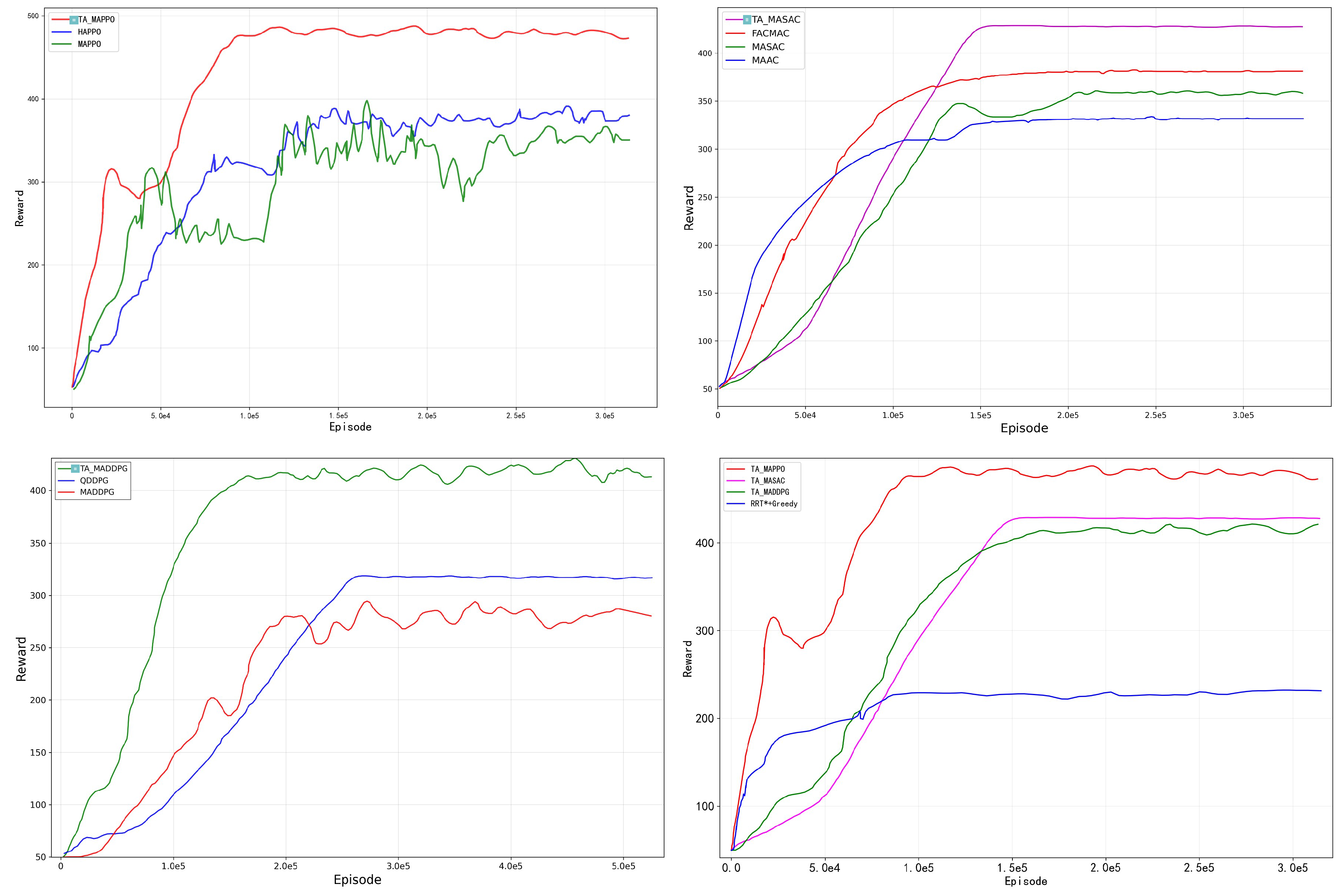

The experimental results based on this learning paradigm (see

Figure 4) show that Topology-Aware Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (TA-MARL) The framework can still maintain stable and stable training performance when the complexity of the environment increases. The specific experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

Tip: The reward curve represents the performance of different algorithms in multiple rounds. The chart in the upper left shows the reward convergence curve of the MAPPO algorithm series; the chart in the lower left shows the reward fluctuation law of the MADDPG algorithm series; the chart in the upper right shows the reward trajectory of the MASAC algorithm series; the chart in the lower right compares the reward change process of TA-MARL and RRT*+greedy algorithm. The curve marked with a square is the reward trajectory of the TA-MARL algorithm.

In terms of training efficiency, TA-MARL significantly improves sample efficiency. In complex scenarios, compared with the standard MAPPO, the final strategy performance of TA-MAPPO is improved by 33.4%, and the training rounds required for convergence are reduced by 38.3%. This improvement is due to the early integration of the topological perception module, so that the intelligent body can detect potential winding risks at the early stage of training and avoid the formation of wrong strategies. It is worth noting that the topological perception component has strong generalization: after combining it with MAPPO, HAPPO, HATRPO and other algorithms, the winding rate is reduced by more than 80%, the task success rate is increased by 4%-8%, and the convergence speed is accelerated by more than 28%, confirming that it strengthens learning in the existing multi-intelligent body (MARL) Universality in the algorithm.

When the complexity of the environment is increased from a simple configuration (4 operating arms and 4 targets) to a complex configuration (10 operating arms and 8 targets), the proposed method still maintains stable performance. In simple scenarios, the task success rate of TA-MAPPO reaches 99.95%, and the probability of winding is only 0.1%; even under the most severe conditions, the task completion rate of 96.8% is maintained, and the performance decline is significantly lower than that of the benchmark method. Traditional algorithms such as RRT* have a winding rate of more than 30% and a task success rate of less than 70% in medium and high complexity environments, and the proposed methods show better security and efficiency; even with advanced multi-intelligent algorithms such as standard MAPPO and HAPPO, the winding rate is usually between 5% and 15%, which is difficult to meet. Security deployment requirements in practical applications. This shows that in a multi-arm dense system, relying only on geometric information or the lack of topological perception in collaborative learning cannot effectively alleviate the risk of systematic entanglement.

Importantly, the framework has excellent scalability: when the number of operating arms increases from 4 to 10, the performance decreases by only 3%, far lower than the 15%-25% decline of the benchmark method. This scalability is mainly due to the fact that the topological perception mechanism does not require precise topological calculation - by simplifying the braid representation and adopting real-time approximate calculation, the state update can be completed within a simulation step length of 10 milliseconds, ensuring that the method is suitable for real-time multi-intelligent systems.

5.4. Ablation Experiment Analysis

In order to evaluate the independent role of each core component in the multi-intelligence enhanced learning system, this study carried out a comprehensive ablation experiment under complex operation scenarios. The results (

Table 5) show that the three core innovation modules of dual-experience playback mechanism, security action replacement layer, and hierarchical control architecture can significantly improve the performance of various benchmark algorithms, and confirm the robustness and generalization of the topological perception framework.

The double experience playback mechanism shows a stable optimization effect in all evaluation algorithms: after removing the mechanism, the winding probability increases significantly, of which TA-MAPPO rises from 0.7% to 1.5%, TA-MASAC rises from 2.0% to 2.8%, and TA-MADDPG rises from 2.3% to 3.2%, which confirms that it has a universal effect on improving learning stability by separating safety and dangerous trajectories. The protective effect of the safe action replacement layer is the most direct: after removal, the algorithm performance decreases significantly (especially in the highly exploratory separation strategy algorithm), and the TA-MADDPG winding rate rises to 4.8%, highlighting its key function of restricting high-risk actions. The hierarchical control architecture also contributed stability. After removal, the task success rate of TA-MAPPO, TA-MASAC and TA-MADDPG decreased by about 5-6 percentage points, which verified that the resource scheduling scheme based on different algorithms has universal effectiveness.

There are significant differences in the response of different algorithm paradigms to topological components: the performance is the best when the strategy algorithm TA-MAPPO adopts the complete configuration (winding rate 0.7%, success rate 96.8%), while the winding rate of the strategy algorithms TA-MASAC and TA-MADDPG is 2.0% respectively, 2.3%. This shows that the strategy algorithm has a natural stronger compatibility with topological security constraints with a stable strategy update mechanism.

The collaborative integration of the three major innovative modules has been fully verified in all test algorithms: the task completion rate of TA-MAPPO’s complete configuration is 12.2 percentage points higher than the benchmark, TA-MASAC is 7.3 percentage points higher, and TA-MADDPG is 10.5 percentage points higher. These performance improvements far exceed the simple superposition effect, confirming the wide applicability of "perception-evaluation-intervention" closed-loop design in various algorithm architectures. The experimental results show that the proposed topological security framework can not only effectively improve the performance of a variety of multi-intelligent reinforcement learning (MARL) algorithms, but also provide an expandable technical path for the security collaborative control of multi-intelligent systems.

5.5. Analysis of Algorithm Efficiency and Stability

Based on the experimental data of

Table 6, this study systematically evaluates the convergence efficiency of various reinforcement learning algorithms in complex operation scenarios. The results show that the convergence speed of topological perception algorithms (especially TA-MAPPO) is significantly improved, about 1.5 times faster than the benchmark MAPPO and about 0.5 times faster than HAPPO, which verifies the effectiveness of the topological perception mechanism to improve the training throughput. It is worth noting that the convergence periods of TA-MAPPO, TA-MASAC and TA-MADDPG are reduced by 76.3%, 45.1% and 48.4% respectively compared with their respective benchmark algorithms, confirming the universality of the framework in different algorithm architectures.

In terms of convergence stability, TA-MAPPO performed the best, and the variance of the stability index was 62.5% lower than that of the benchmark MAPPO; the stability of the topological perception variants TA-MASAC and TA-MADDPG was improved by 15.2% and 22.2% respectively, highlighting the improvement through topological perception. The generalization of stability. This shows that topological constraints effectively reduce the policy update variance and ensure the robustness of the training process by limiting the intelligent body exploration to the safe operation area.

The sampling efficiency index further confirms the advantages of the topological perception framework: the performance of TA-MAPPO is better than that of other comparison algorithms, 81.1% better than that of the benchmark MAPPO. Although the convergence period of the traditional motion planning method RRT*+Greedy is shorter, its convergence stability is relatively poor. The sampling efficiency of all topological perception variants has been comprehensively improved, confirming the effectiveness of the dual-experience playback mechanism - the mechanism optimizes the data utilization rate by emphasizing learning from the security trajectory.

As shown in

Table 7, the evaluation results of parameter sensitivity and robustness show that the topological perception framework has a significant robustness advantage: the parameter sensitivity of all topological perception algorithms is low, while the benchmark algorithm generally shows medium and high sensitivity, confirming that the topological perception component is universal for improving robustness. Effect.

The robustness score further supports the stability advantages of the topological perception framework: TA-MAPPO obtained the highest robustness score and maintained excellent performance stability under environmental interference and sensor noise. This robustness improvement comes from a multi-layer security mechanism: topological invariants increase the state characterization dimension and reduce the impact of environmental uncertainty; the security action replacement layer effectively filters high-risk actions; and the hierarchical control architecture improves fault tolerance by optimizing resource scheduling. In contrast, traditional methods such as RRT*+Greedy are prone to systematic failures in complex interaction environments due to the lack of topological risk perception, and the robustness is only at an average level. The integration of historical topological information into the decision-making process greatly improves the adaptability of the system in dynamic operation scenarios.