Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description and Modeling

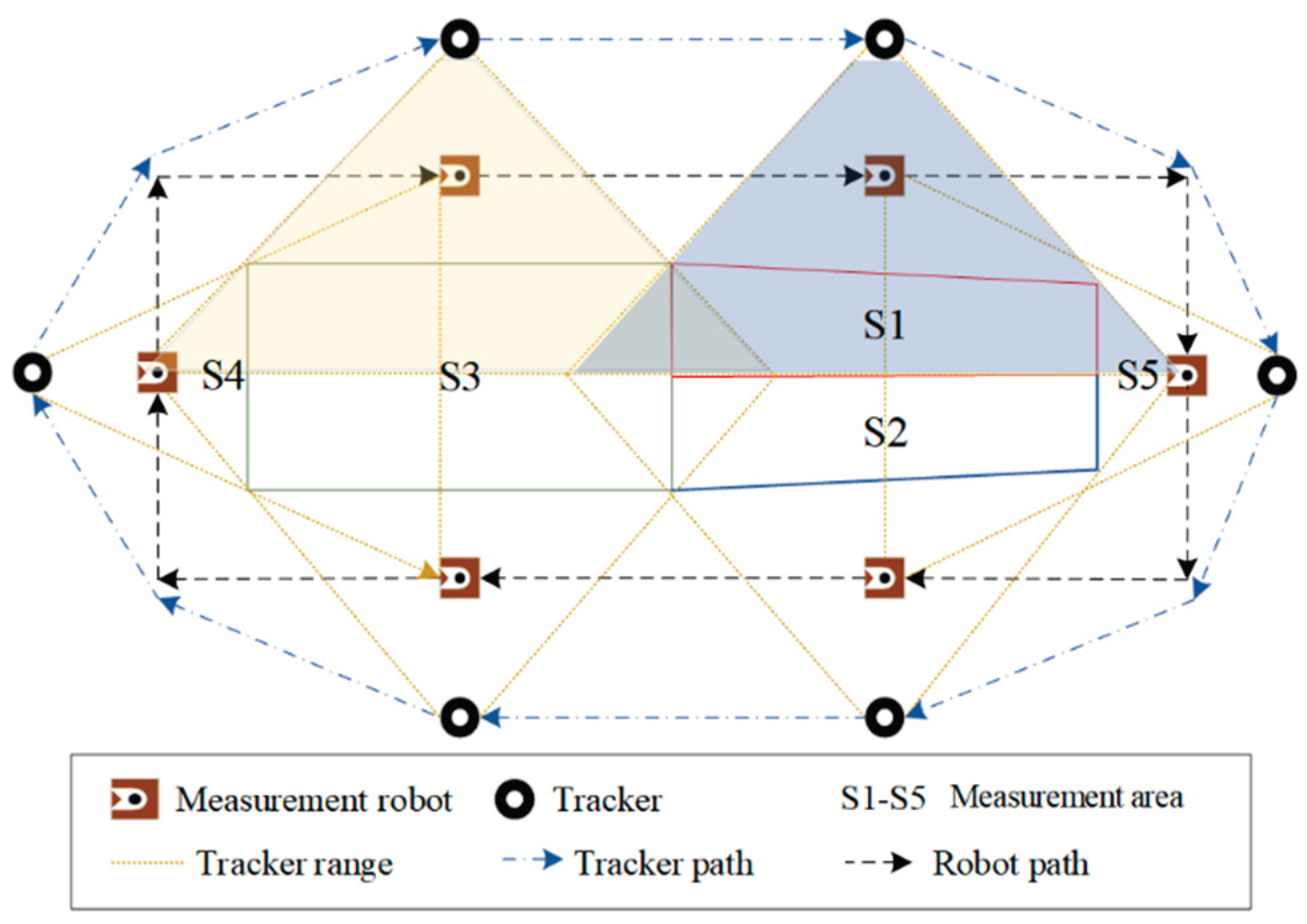

2.1. Problem Description

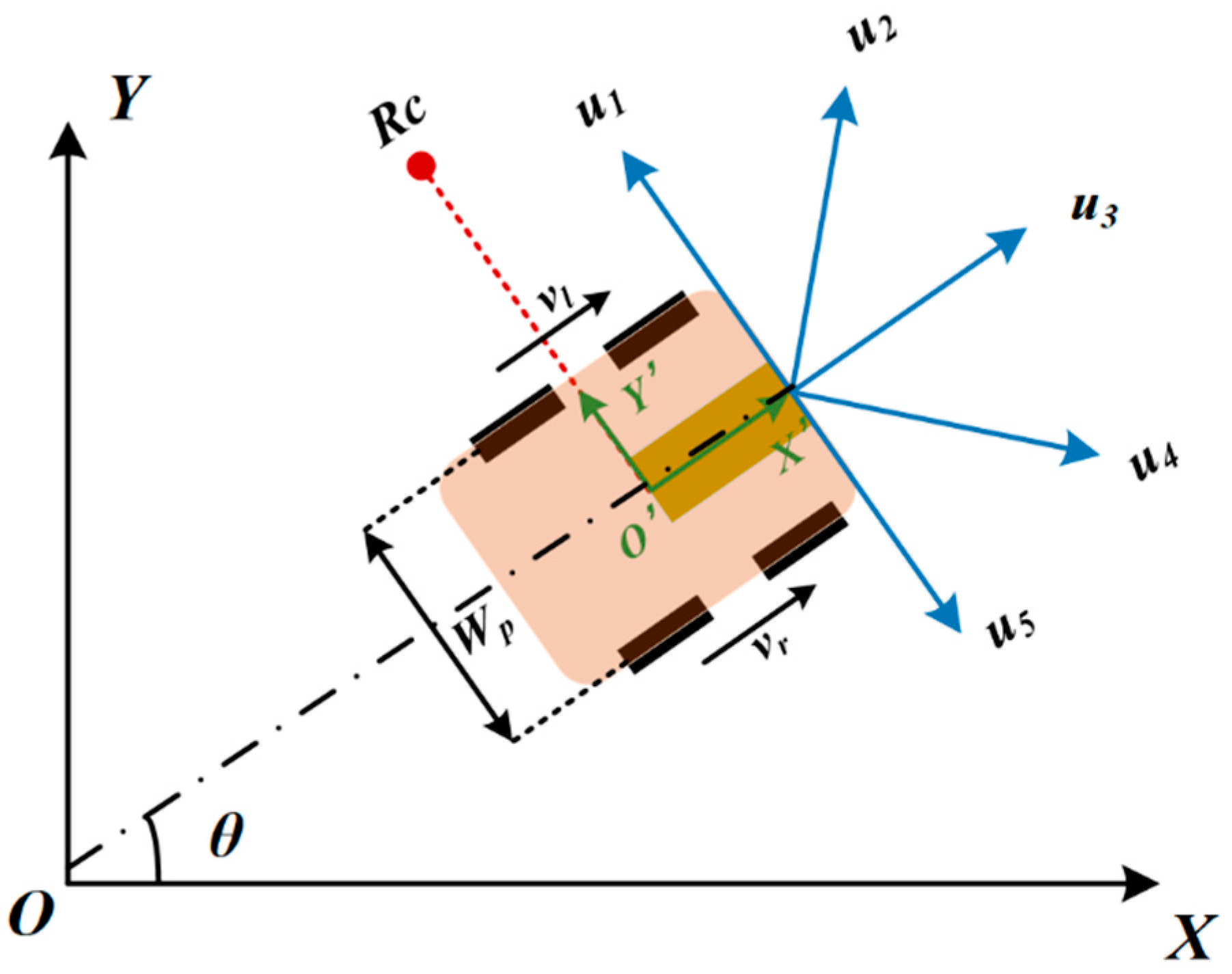

2.2. Dynamic Modeling for Mobile Robots

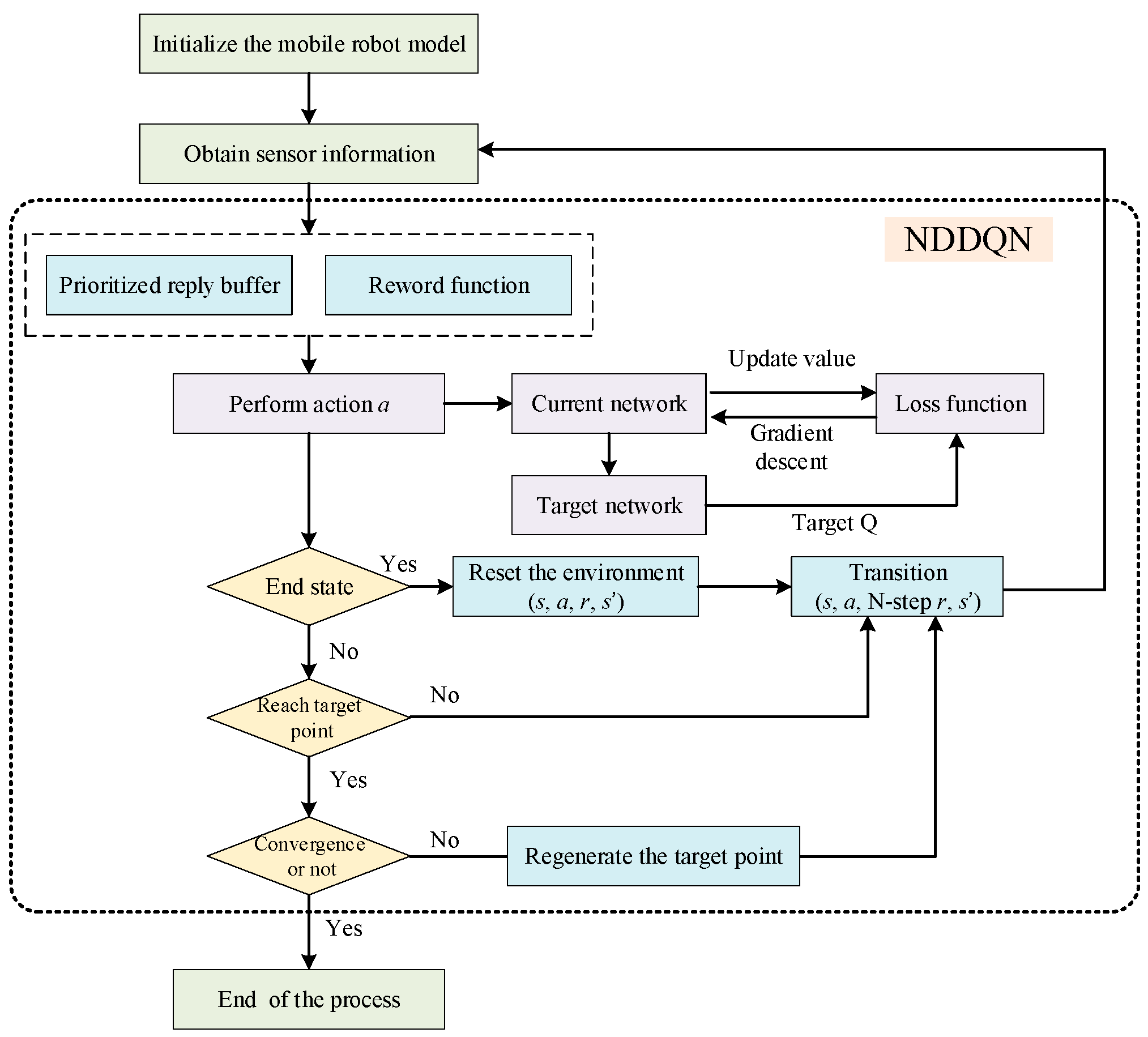

3. Improved Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm

3.1. Markov Process

3.2. Double-Q Learning

3.3. Priority Experience Reply

3.4. Priority N-step Update Strategy

4. Experimental Verification and Analysis

4.1. Exoerimental Environment

4.2. Deep Learning Parameter Settings

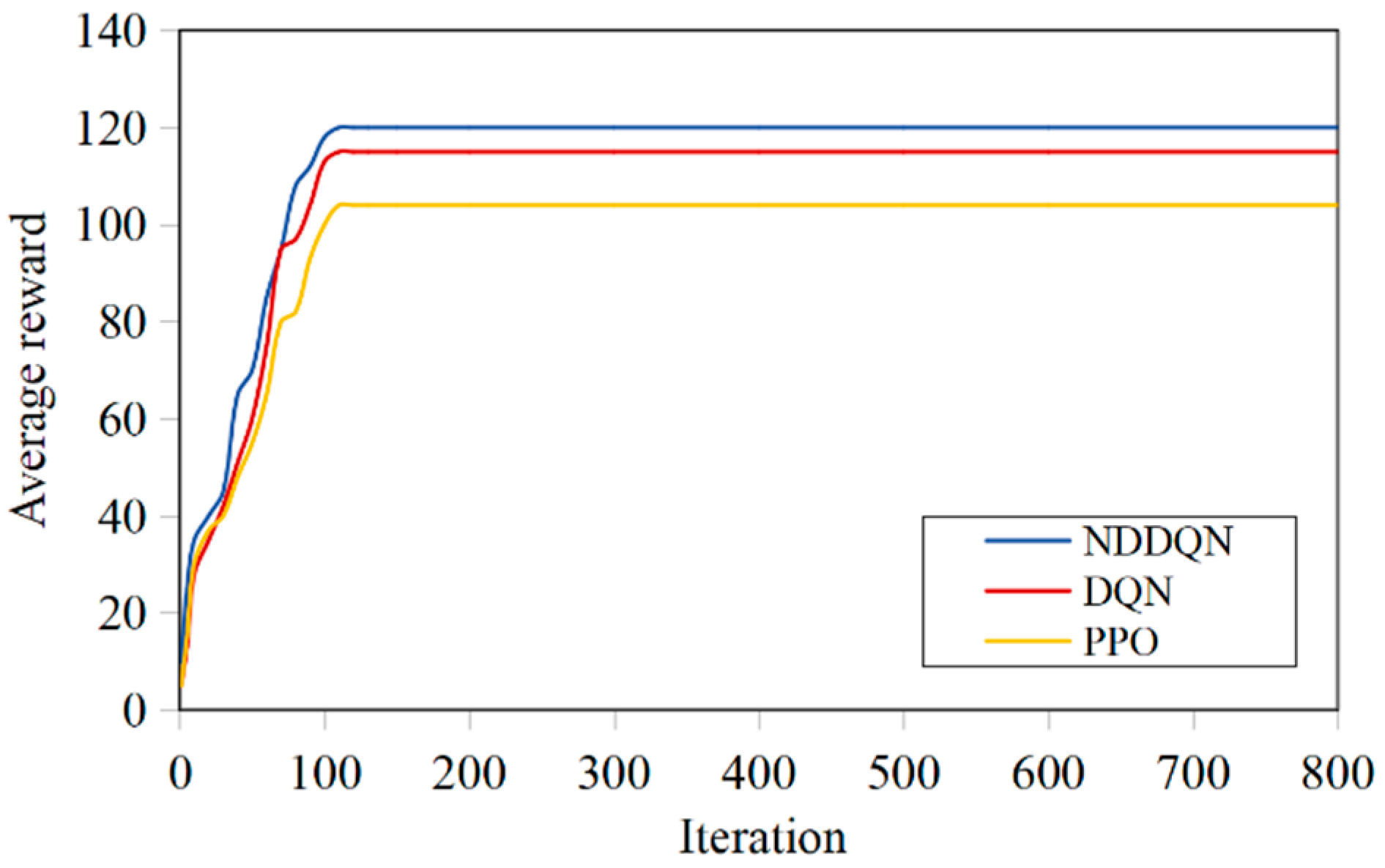

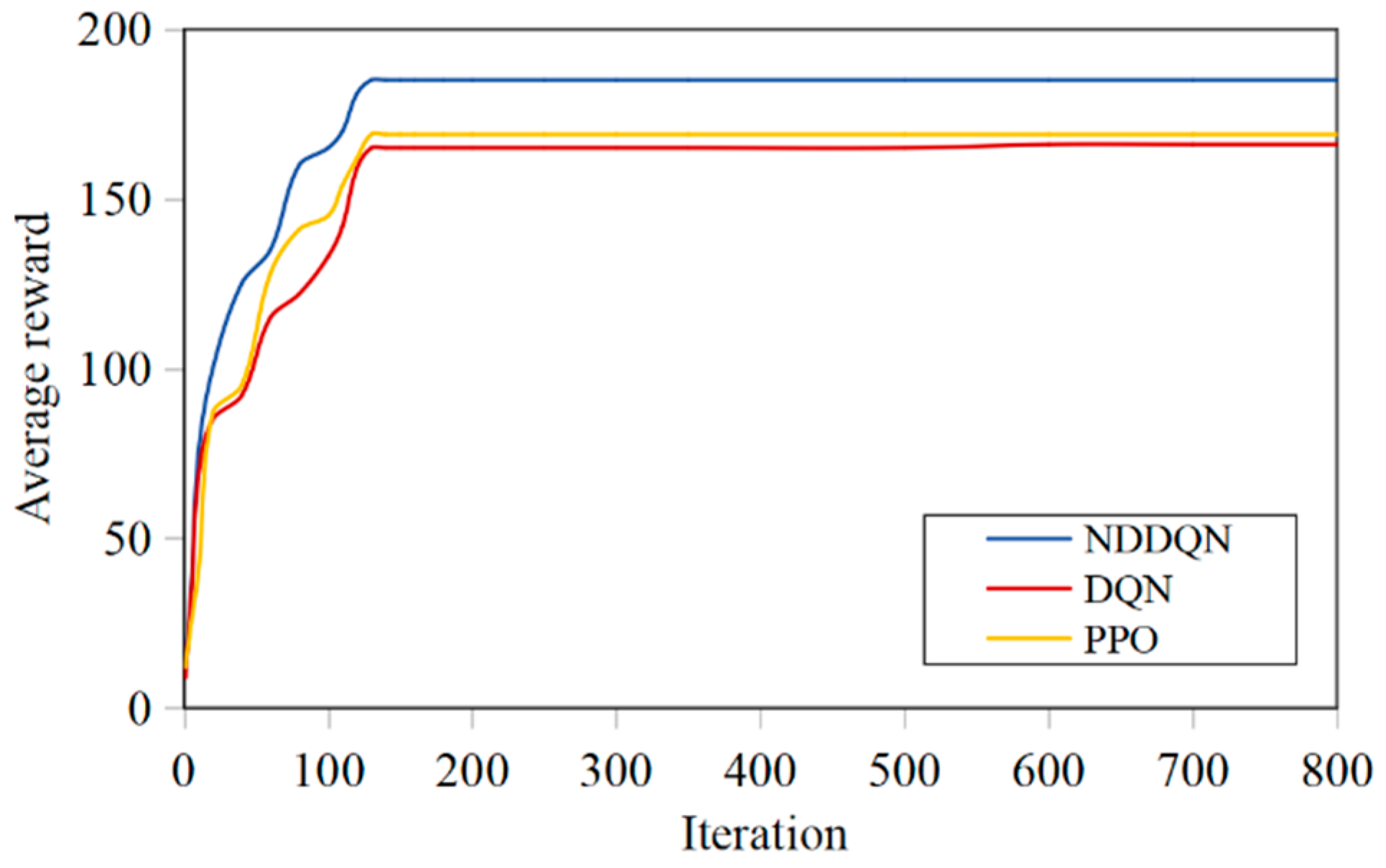

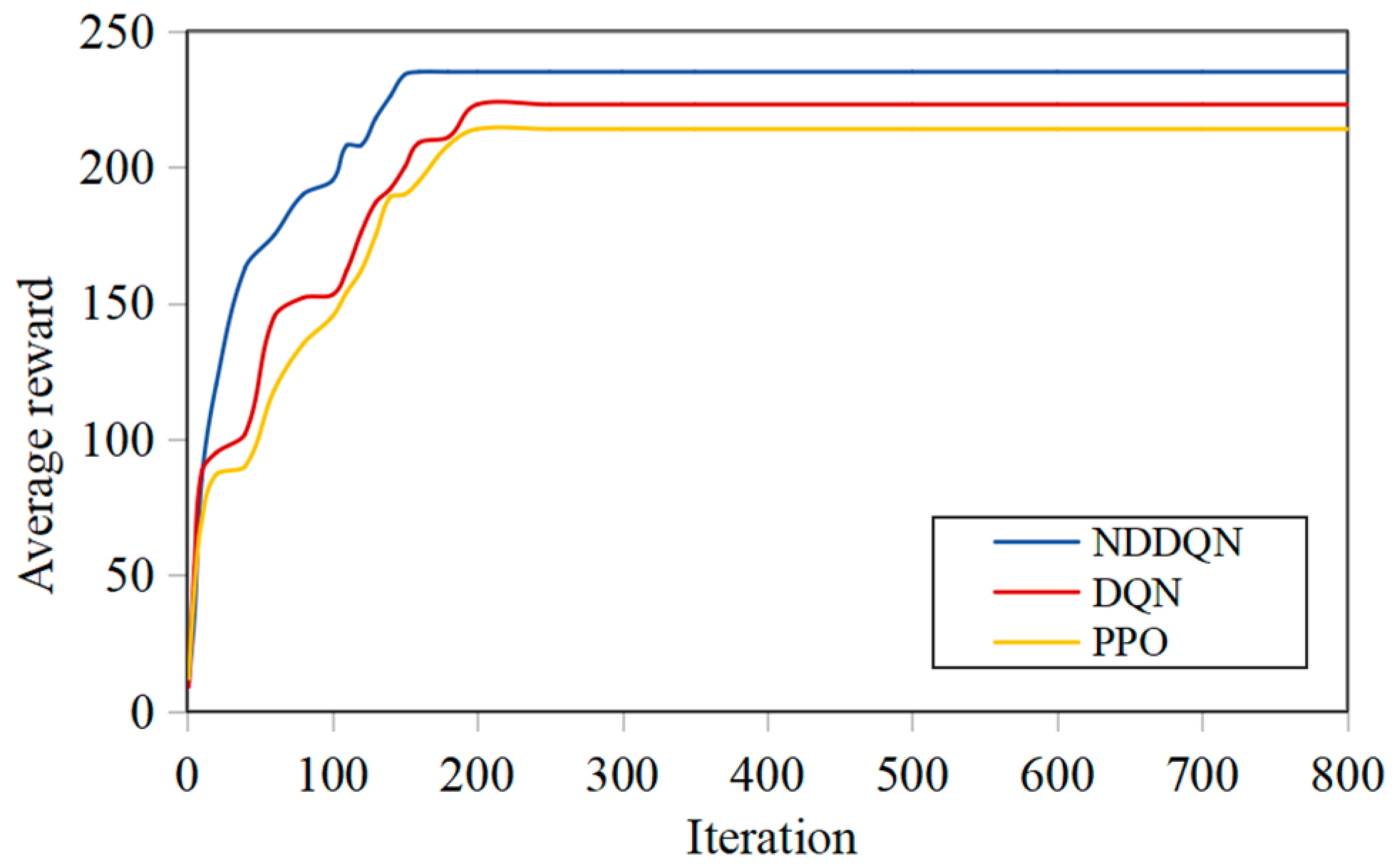

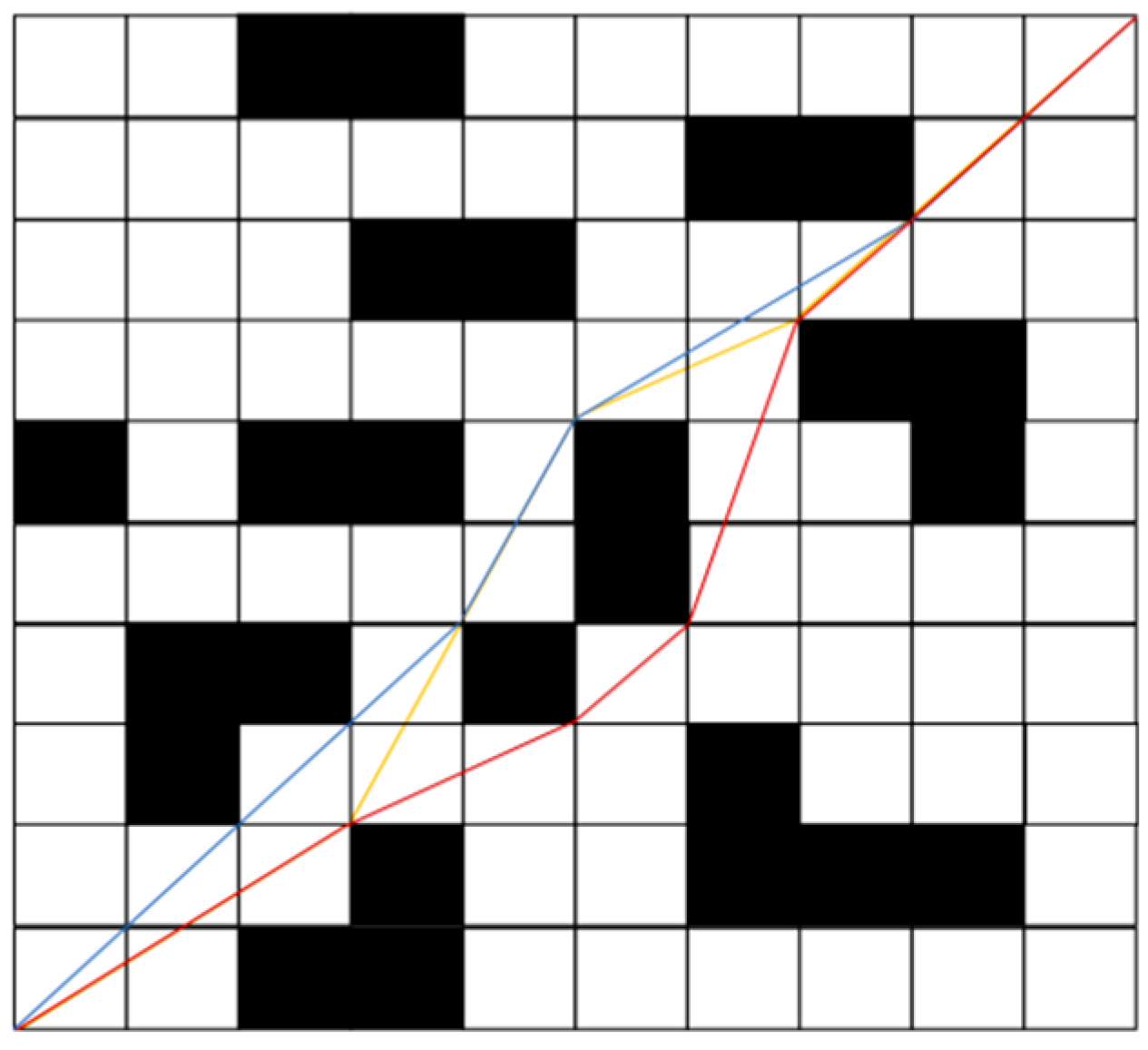

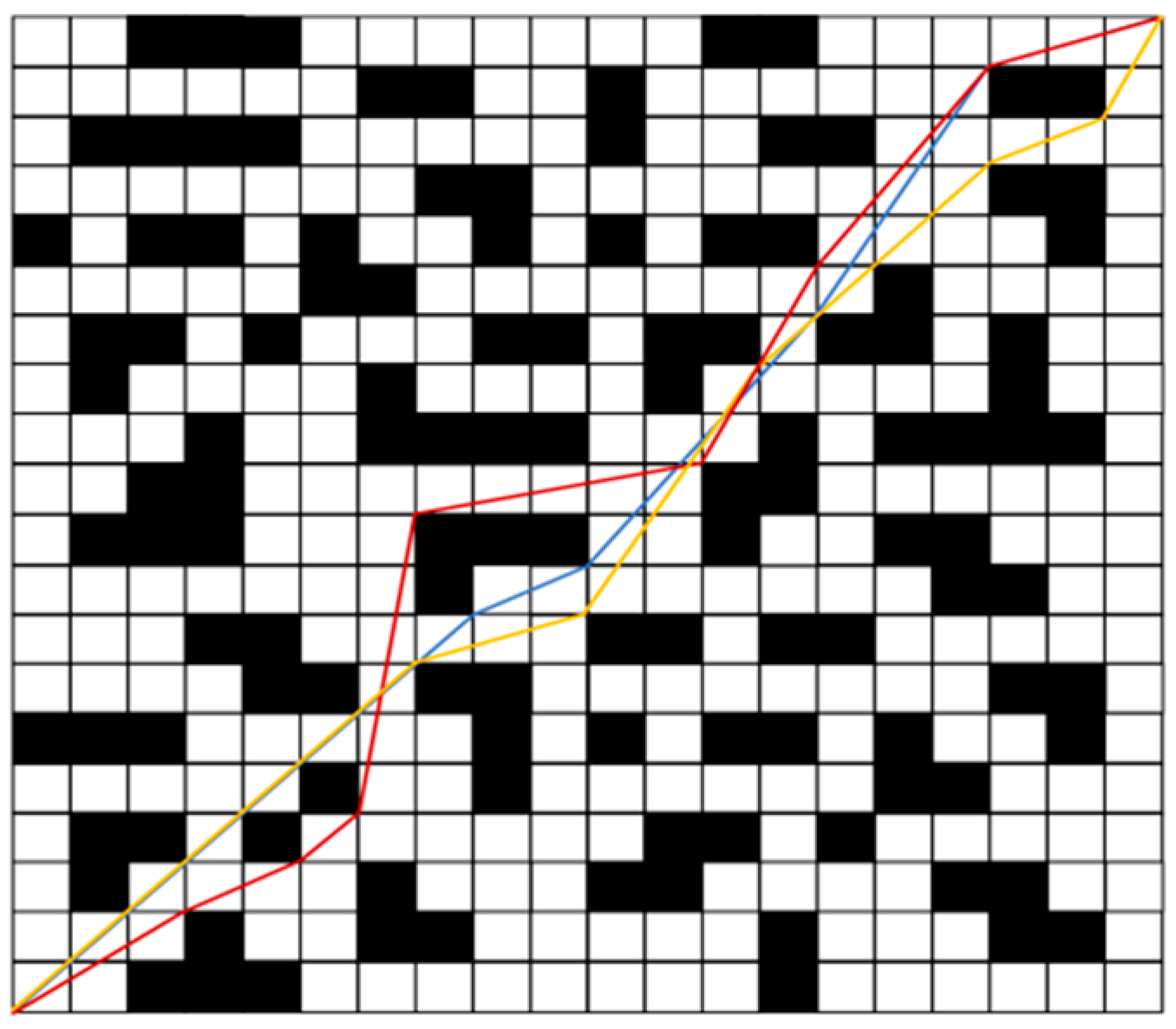

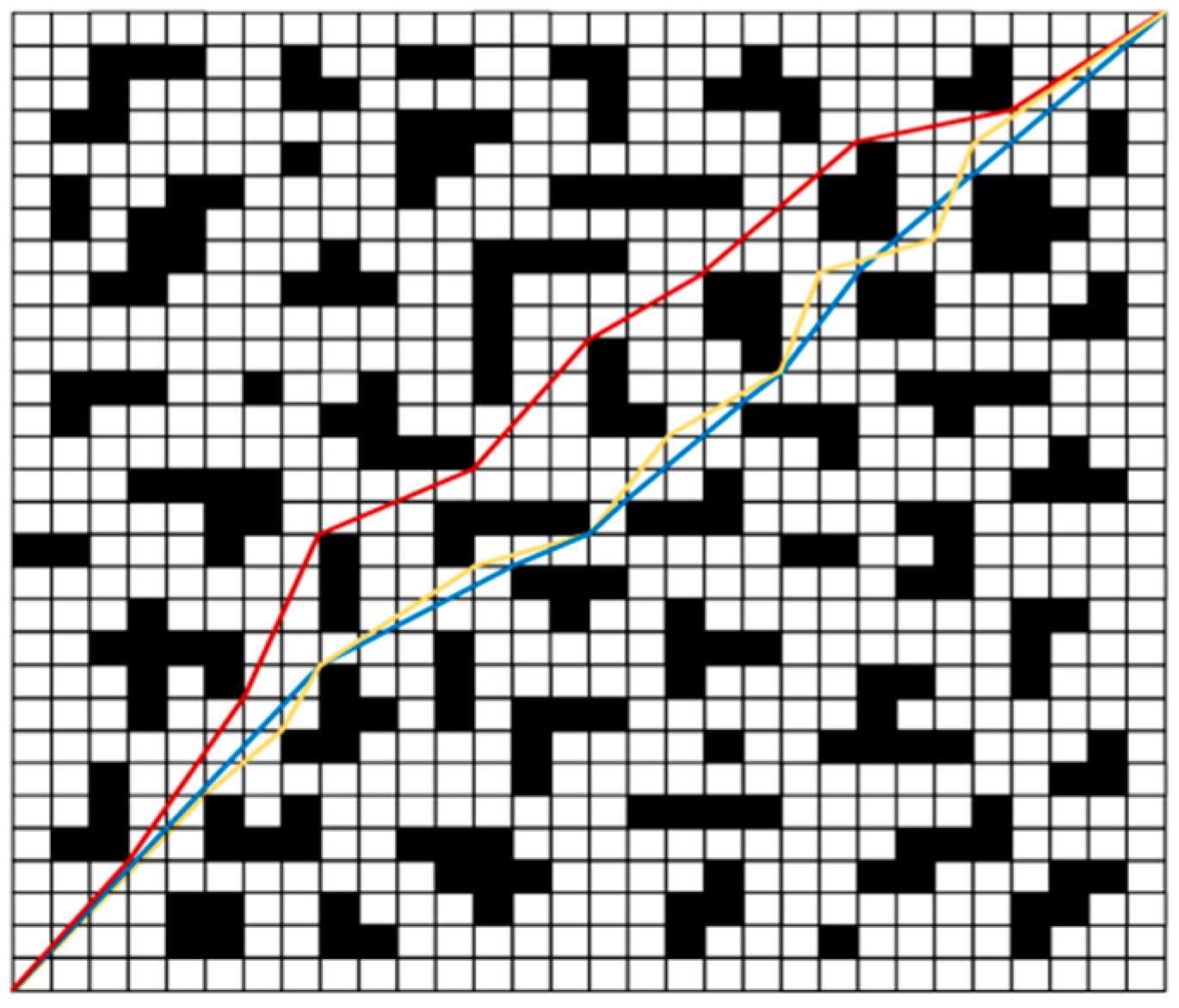

4.3. Simulation Results Analysis in Grid Map

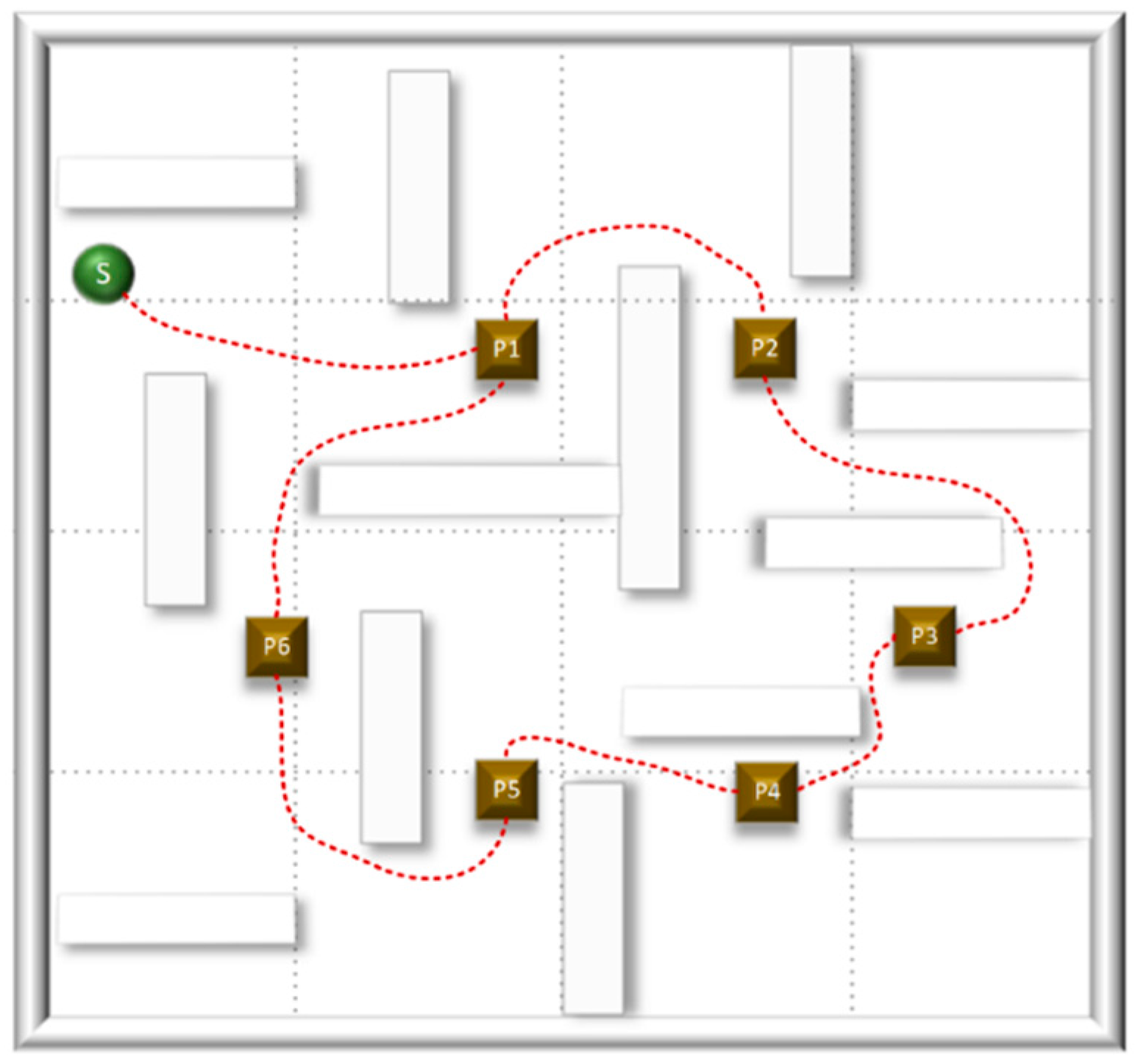

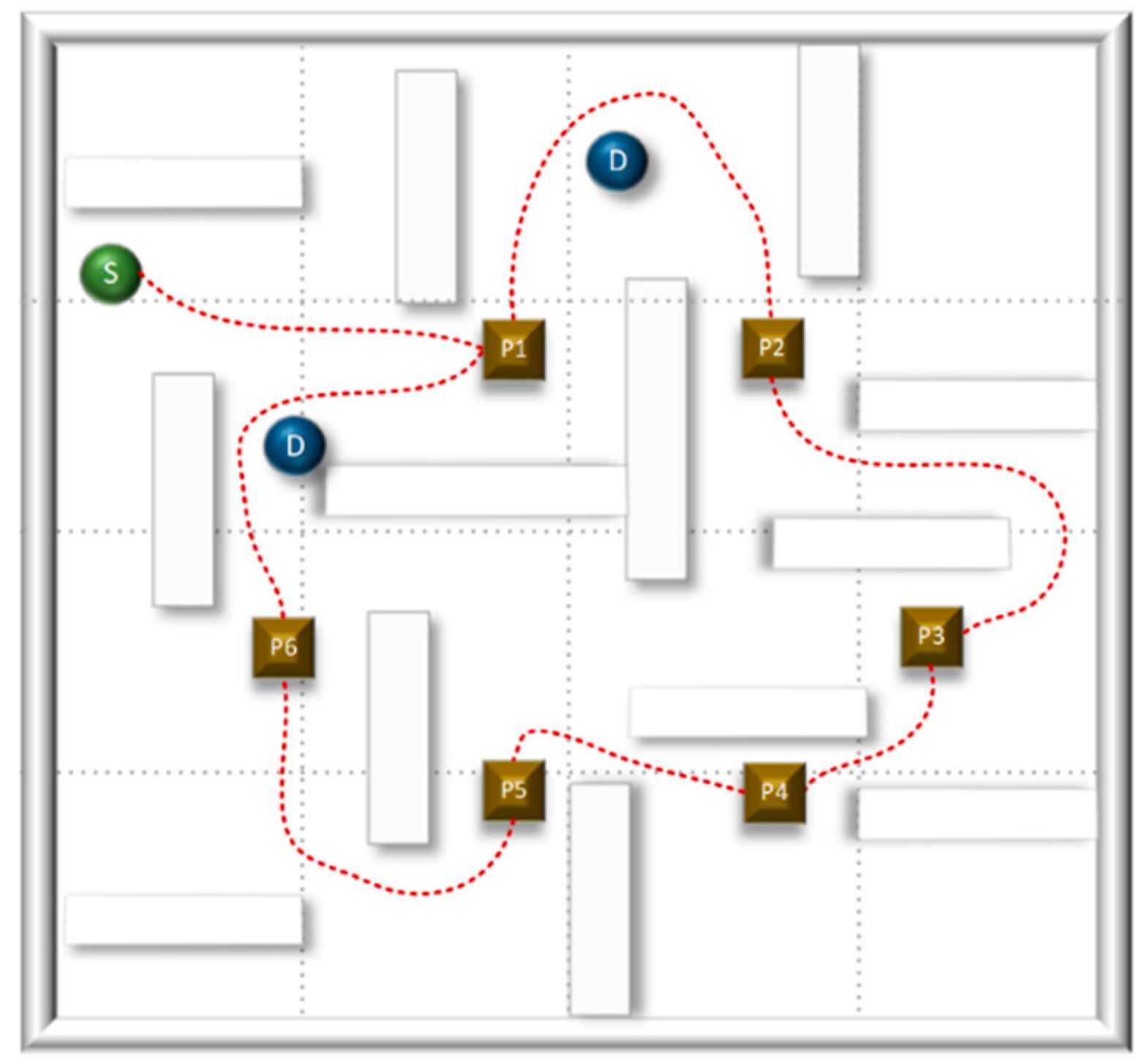

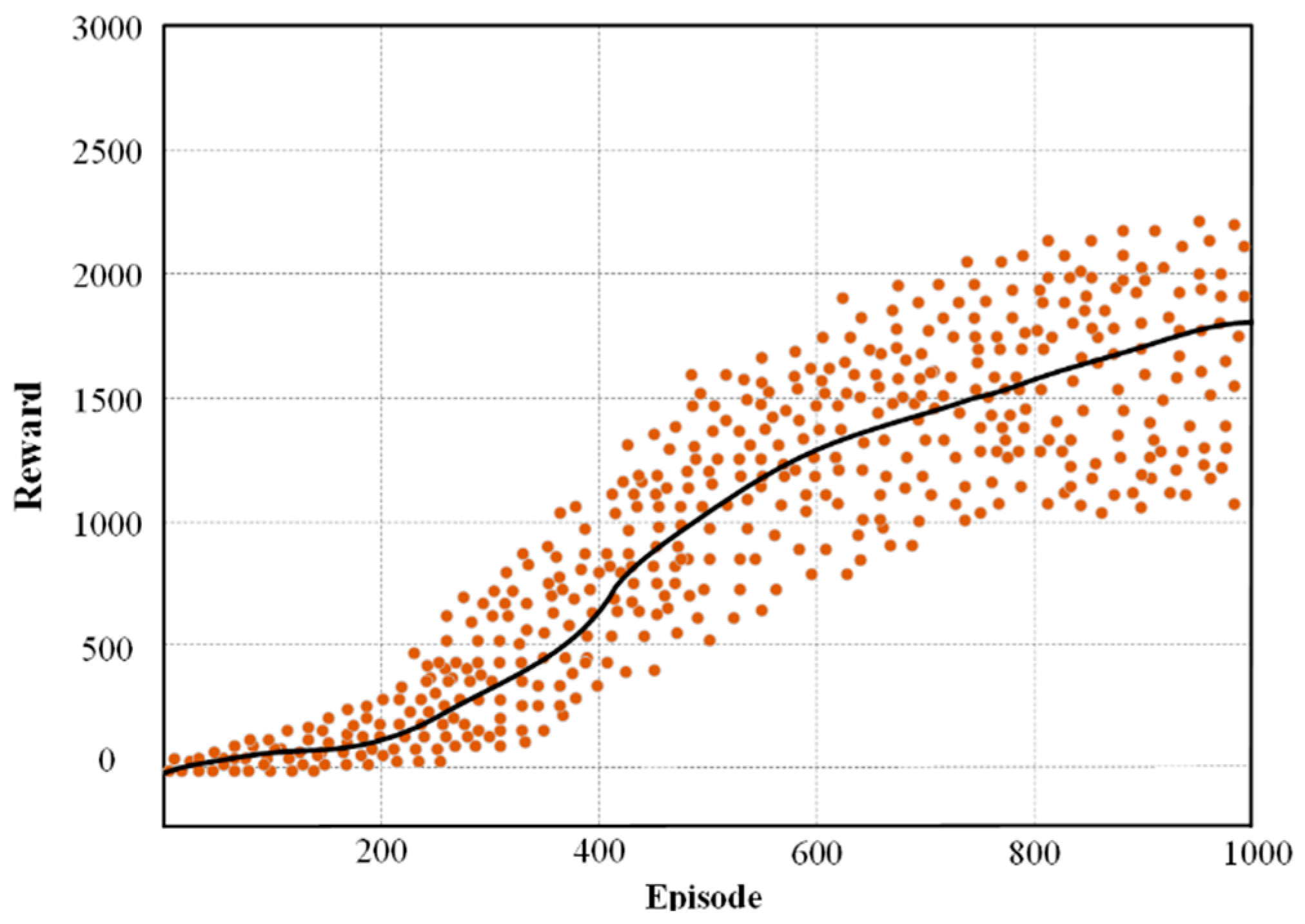

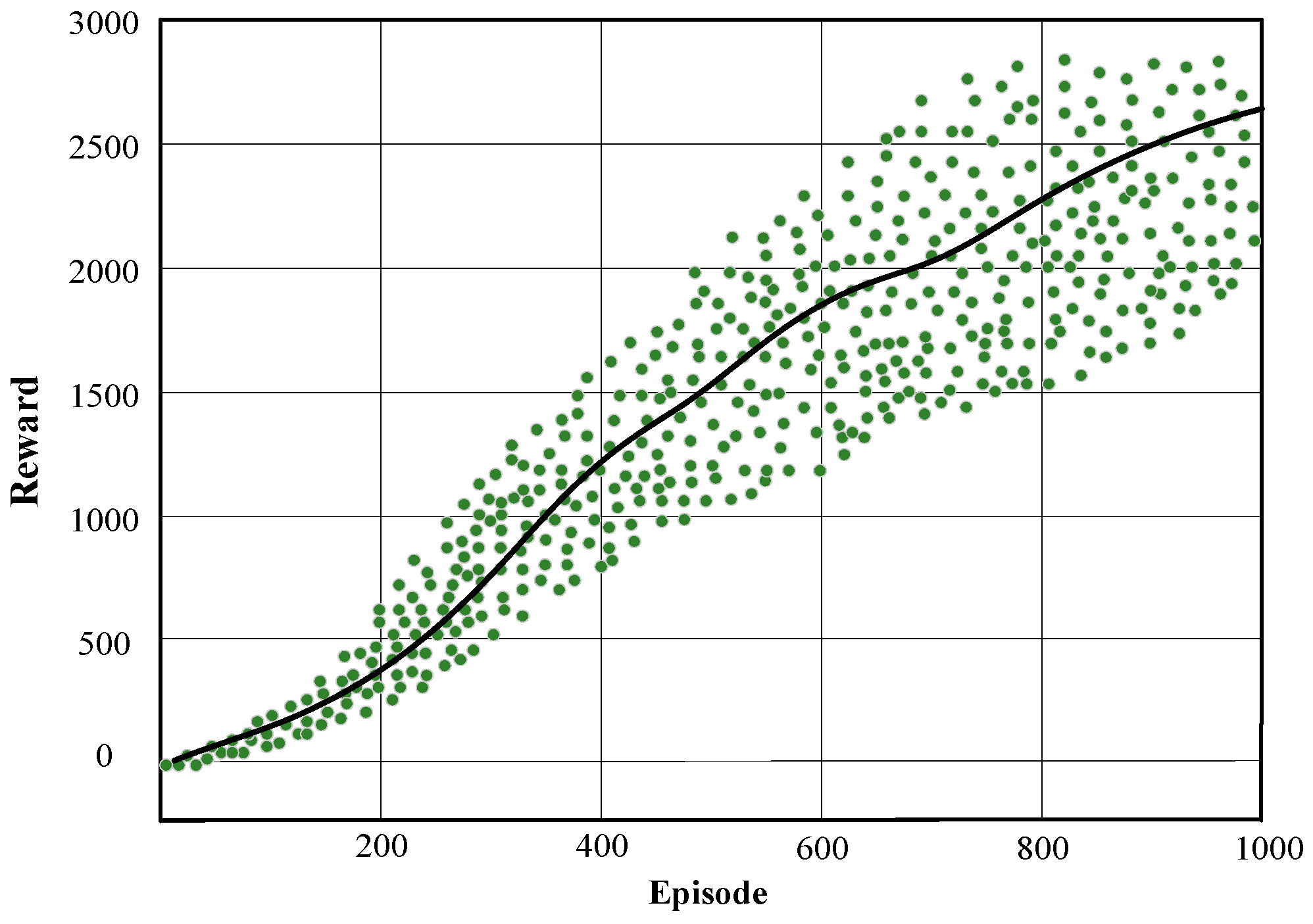

4.4. Simulation Results Analysis in Gazebo

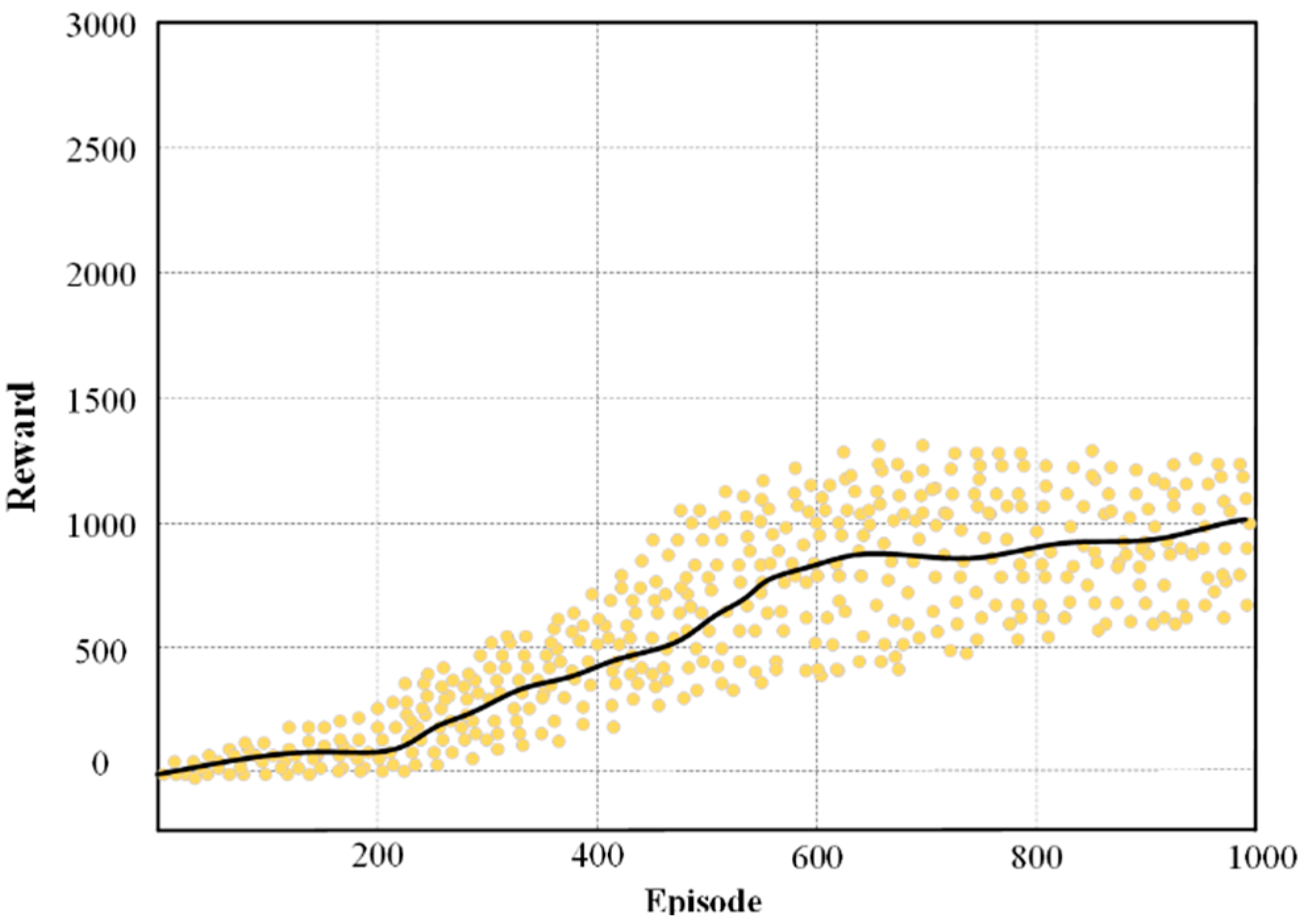

4.5. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| The robot's position of the global coordinate. | |

| The target point's position of the global coordinate. | |

| The linear velocity of the left front wheel and the left rear wheel of the robot. | |

| The linear velocity of the right front wheel and the right rear wheel. | |

| The forward linear velocity of the robot. | |

| The turning angular velocity of the robot. | |

| The instantaneous curvature center. | |

| The instantaneous radius of curvature. | |

| The Angle between the center of the robot and the global coordinate system. | |

| The reward of the robot agent. | |

| The state of robot agent. | |

| The action of the robot agent. | |

| The next state of robot agent. | |

| The next action of the robot agent. | |

| The next reward of the robot agent. | |

| The discount factor, and . | |

| The state space of robot. | |

| The action space of robot. | |

| The strategy of each state behavior. | |

| The probability of choosing action in state . | |

| The probability of obtaining the next state under state and behavior | |

| The reward for choosing behavior under state | |

| The cumulative reward of robot agent. | |

| The optimal strategy of robot agent. | |

| The optimal state value of robot agent. | |

| The optimal action value of robot agent. | |

| The updating network weight. | |

| The loss function. | |

| The target network. | |

| The priority weight of the jth sample. | |

| α | Learning rate. |

References

- Chen, Z.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y. Image-Based Visual Servoing With Collision-Free Path Planning for Monocular Vision-Guided Assembly. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Monaco, E.; Rautela, M.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Ricci, F. Machine learning algorithms for delaminations detection on composites panels by wave propagation signals analysis: Review, experiences and results. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 146. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Das, S.; Townley, S. Robot Differential Drive Navigation Through Probabilistic Roadmap and Pure Pursuit. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 22118–22132. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, T.; Tian, H. Research on Reducing Assembly Errors in Inductive Encoders With Observer Phase Detector Phase-Locked Loop. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 28744–28751. [CrossRef]

- SUI, S.; ZHU, X. Digital measurement technique for evaluating aircraft final assembly quality. Sci. Sin. Technol. 2020, 50, 1449–1460. [CrossRef]

- Unhelkar, V.V.; Dorr, S.; Bubeck, A.; Lasota, P.A.; Perez, J.; Siu, H.C.; Boerkoel, J.C.; Tyroller, Q.; Bix, J.; Bartscher, S.; et al. Mobile Robots for Moving-Floor Assembly Lines: Design, Evaluation, and Deployment. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2018, 25, 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Lv, F.; Shi, J.; Tian, G.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Pham, D.T. Integrated optimisation of human-robot collaborative disassembly planning and adaptive evaluation driven by a digital twin. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Jin, X.; Lei, K.; Zhang, Q. Research on Energy-Saving and Efficiency-Improving Optimization of a Four-Way Shuttle-Based Dense Three-Dimensional Warehouse System Based on Two-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11367. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, C. A graph-based pipe routing algorithm in aero-engine rotational space. J. Intell. Manuf. 2013, 26, 1077–1083. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y. An Improved Multi-UAV Area Coverage Path Planning Approach Based on Deep Q-Networks. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11211. [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Ding, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Sun, L. A Generalized Voronoi Diagram-Based Efficient Heuristic Path Planning Method for RRTs in Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 4926–4937. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, G.; Niu, X.; Xia, C.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Sun, Y. A hybrid formation path planning based on A* and multi-target improved artificial potential field algorithm in the 2D random environments. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2022, 54. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Qin, J.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Ma, Q. SRL-ORCA: A Socially Aware Multi-Agent Mapless Navigation Algorithm in Complex Dynamic Scenes. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 9, 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Soualhi, T.; Crombez, N.; Ruichek, Y.; Lombard, A.; Galland, S. Learning Decentralized Multi-Robot PointGoal Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 4117–4124. [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, D.P.; Stiller, P.F.; Zegers, F.M.; Dixon, W.E. Plug-and-Play Cooperative Navigation: From Single-Agent Navigation Fields to Graph- Maintaining Distributed MAS Controllers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2023, 69, 5262–5277. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Song, K.-T. Path Re-Planning Design of a Cobot in a Dynamic Environment Based on Current Obstacle Configuration. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 1183–1190. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Lin, J.; Yu, H. A generalisable tool path planning strategy for free-form sheet metal stamping through deep reinforcement and supervised learning. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 36, 2601–2627. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, W. RLoPlanner: Combining Learning and Motion Planner for UAV Safe Navigation in Cluttered Unknown Environments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 4904–4917. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Pang, H.; He, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, T. Path Planning of Autonomous Mobile Robot in Comprehensive Unknown Environment Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 22153–22166. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Wei, D.; Fu, K.; Liu, L.; Gao, B.; Liu, Q.; Huang, J. Efficient Target Assignment via Binarized SHP Path Planning and Plasticity-Aware RL in Urban Adversarial Scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9630. [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, M.M.; Tang, T.B.; Lu, C.-K. Vision-Based Autonomous Navigation Approach for a Tracked Robot Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Sensors J. 2020, 21, 2230–2240. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, B.; Fränti, P. A review of motion planning algorithms for intelligent robots. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 33, 387–424. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Mobile Robot Path Planning Based on Improved Localized Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Sensors J. 2020, 21, 6962–6972. [CrossRef]

- W.D. Smart; L.P. Kaelbling. Effective reinforcement learning for mobile robots. Proceedings 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation 2002, Volume 4, 3404–3410.

- Low, E.S.; Ong, P.; Cheah, K.C. Solving the optimal path planning of a mobile robot using improved Q-learning. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 115, 143–161. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W. Concise deep reinforcement learning obstacle avoidance for underactuated unmanned marine vessels. Neurocomputing 2018, 272, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Xu, K.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Yan, J. Path planning in an unknown environment based on deep reinforcement learning with prior knowledge. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 5773–5789. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Han, Q. Improved DQN for Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance and Ship Path Planning. Algorithms 2023, 16, 220. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Motoi, N. Path Planning for Mobile Robot Considering Turnabouts on Narrow Road by Deep Q-Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 19111–19121. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lv, J.; Shi, L.; Hou, Z.; Xu, S. DM-DQN: Dueling Munchausen deep Q network for robot path planning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 9, 4287–4300. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, F. Anti-conflict AGV path planning in automated container terminals based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 61, 65–80. [CrossRef]

- Z. G. Li; S. Han; Y. J. Chen; et al. Mobile robots path planning algorithm based on angle searching and deep Q-network. Acta Armamentarii 2025, Volume 46, 1–14.

- Wu, Q.; Lin, R.; Ren, Z. Distributed Multirobot Path Planning Based on MRDWA-MADDPG. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 25420–25432. [CrossRef]

- Z. Y. Li; X. T. Hu; Y. L. Zhang; et al. Adaptive Q-learning path planning algorithm based on virtual target guidance. Computer Integrated Manufacturing Systems 2024, Volume 30, 553–568.

- Hua, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Hierarchical Motion Planning Strategy for Multirotors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2025, 21, 4324–4333. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, J. Hierarchical Control Framework for Path Planning of Mobile Robots in Dynamic Environments Through Global Guidance and Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.; Pan, S.; Dengler, N.; Zhou, S.; Schoellig, A.P.; Bennewitz, M. Safe Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Behavior-Based Cooperative Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 6256–6263. [CrossRef]

- Jonnarth, A.; Johansson, O.; Zhao, J.; Felsberg, M. Sim-to-Real Transfer of Deep Reinforcement Learning Agents for Online Coverage Path Planning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 106883–106905. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Hu, C.; Kong, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. An Improved HM-SAC-CA Algorithm for Mobile Robot Path Planning in Unknown Complex Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21152–21163. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, B. Soft Actor-Critic Combining Potential Field for Global Path Planning of Autonomous Mobile Robot. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 7114–7123. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Environment-Adaptive Motion Planning via Reinforcement Learning-Based Trajectory Optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 16704–16715. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Huan, J.; Wang, Q.; Yu, H.; Gao, S. ST-D3QN: Advancing UAV Path Planning With an Enhanced Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework in Ultra-Low Altitudes. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 65285–65300. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Xia, G.; Ding, H. A Novel Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Path/Force Cooperative Regulation Framework for Dual-Arm Object Transportation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 15792–15804. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, R.; Liang, Z. Research on the Local Path Planning for Mobile Robots based on PRO-Dueling Deep Q-Network (DQN) Algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yan, J.; Du, H.; Zhou, F. Path Planning for Full Coverage of Farmland Operations in Hilly and Mountainous Areas Based on the Dung Beetle Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9157. [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter | Value |

| The first layer network nodes | 256 |

| The second layer network nodes | 256 |

| The third layer network nodes | 128 |

| Max episodes | 1000 |

| Max steps | 800 |

| Learning rate (α) | 0.0005 |

| Mini-batch | 64 |

| Discount factor (γ) | 0.95 |

| Network update rate | 0.001 |

| The safe distance | 0.5m |

| Playback cache storage capacity | 50000 |

| Action | Linear Velocity (v) | Angular Velocity (ω) |

| Move forward | 0.8 m/s | 0 rad/s |

| Turn left | 0.8 m/s | -0.5 rad/s |

| Turn right | 0.8 m/s | 0.5 rad/s |

| Turn left quickly | 0.8 m/s | -1 rad/s |

| Turn right quickly | 0.8 m/s | 1 rad/s |

| Grid | Algorithm | Total reward | Time | Total length | Number of turns | Average curvature |

| 10×10 | NDDQN | 121 | 19.41 | 14.33 | 3 | 4.2 |

| DQN | 115 | 19.69 | 14.55 | 3 | 4.4 | |

| PPO | 104 | 20.33 | 14.66 | 4 | 5.8 | |

| 20×20 | NDDQN | 183 | 38.46 | 28.78 | 5 | 3.8 |

| DQN | 166 | 38.78 | 29.02 | 5 | 4.1 | |

| PPO | 169 | 41.31 | 30.25 | 7 | 5.2 | |

| 30×30 | NDDQN | 233 | 53.06 | 40.05 | 7 | 3.9 |

| DQN | 221 | 57.40 | 42.32 | 10 | 5.5 | |

| PPO | 214 | 57.96 | 43.17 | 9 | 4.8 |

| Method | Success Rate | Convergence Time/Min | ||

| E1 | E2 | E1 | E2 | |

| PPO | 34.2 | 28.4 | 248 | 286 |

| DQA | 58.3 | 49.2 | 153 | 193 |

| NDDQA | 92.7 | 88.6 | 114 | 142 |

| Model | Average Returns | Training Steps | Standard Deviation |

| -N-step | 450.2 ± 25.1 | 55,80 ± 6,50 | 25.1 |

| -PER | 420.5 ± 45.7 | 72,10 ± 8,90 | 45.7 |

| -DQL | 485.3 ± 22.5 | 41,00 ± 5,00 | 22.5 |

| Baseline DQN | 400.8 ± 52.0 | >100,00 | 52.0 |

| NDDQN | 00.0 ± 15.3 | 38,500± 4,20 | 15.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).