1. Introduction

Several proliferative, non-proliferative, and non-malignant breast changes are associated with the risk of developing cancer [

1,

2]. To diagnose these changes and determine their prognostic significance, samples from core-needle biopsy (CNB) and/or fine needle aspiration (FNA) [

3], with needle sizes varying from 27G (FNA, outer diameter 0.4 mm) to 12G (CNB), were analysed in comparison to surgical samples.

FNA is less and less used in modern breast diagnostics, limited by its inability to distinguish between in situ and low-grade cancers or lobular carcinoma. Furthermore, FNA cannot differentiate between sclerosing and papillary lesions or atypical ductal hyperplasia (DH) [

4,

5]. It can however be used without local anaesthetics, and a report can usually be generated within a few hours.

CNB is considered the preferred choice over repeated FNA [

6]. However, even CNB has its limitations, including an upgrade rate to invasive cancer of up to 20% following an initial in situ diagnosis, and an upgrade rate of B3 lesions to malignancy ranging from 3–40%, depending on the lesion type [

7].

Over the past two decades, larger-diameter biopsy needles, up to 7G (outer diameter 4.6 mm), have been introduced and paired for use in vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB), resulting in reduced rates of histological underestimation [

7,

8,

9]. The primary advantage of VAB compared to CNB, besides its larger needle size, is its ability to obtain multiple samples through a single small skin incision, thereby enhancing tissue sampling and diagnostic accuracy [

10,

11]. For certain lesions, continued sampling until the entire lesion is no longer visible has been established as an alternative to open surgical excision (OSE), a technique known as vacuum-assisted excision (VAE).

Histopathological findings are categorized according to the European guidelines for quality assurance of breast cancer screening and diagnosis [

12,

13]. These categories include B1 (normal or non-diagnostic tissues), B2 (benign lesions), B3 (lesions with a 9.9–35.1% overall risk of upgrading to malignancy upon subsequent surgery) [

14], B4 (suspected malignant lesions), and B5 (malignant lesions). The B3 category, referred to as “probably benign,” is the most controversial in therapeutic management and includes: ADH, flat epithelial atypia (FEA), classical lobular neoplasia (LN) (including atypical lobular hyperplasia [ALH] and classical lobular cancer in situ [cLCIS]), phyllodes tumors, intraductal papillomas (with or without atypia), radial scars or complex sclerosing lesions, mucocele-like lesions, and other miscellaneous lesions [

12,

15]. The prevalence of B3 lesions in otherwise healthy women ranges from 5–10% [

16,

17,

18]. Most B3 lesions represent a clinical dilemma, as the only definitive method of excluding malignancy is OSE, often regarded as the “gold standard” for conclusive diagnosis [

14]. Given the advantages of improved patient comfort and cost-effectiveness, utilizing VAE for managing B3 lesions has become increasingly common [

19]. Since 2016, several organizations [

20,

21,

22,

23] have endorsed VAE for the management of B3 lesions.

This study aims to identify the patterns of pathological diagnoses across sequential diagnostic procedures in individual patients, including initial biopsy, successive VAE sampling containers, and any follow-up diagnoses within 2 years, to enhance our understanding of B3 lesions and inform strategies for optimized diagnosis and personalized management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Population

This retrospective study was based on the Swedish VAE trial, whose primary endpoints were procedure time and completeness of breast lesion removal. [

24]. The present study focused on histopathological reports across the diagnostic pathways of each patient, from CNB and/or FNA, and across three sequential tissue samples containers collected during VAE. From the established study population of the Swedish VAE trial, we excluded patients who did not undergo biopsy before VAE.

2.2. Diagnosis and Excision Procedure

Lesions were diagnosed before VAE using ultrasound-guided CNB (14G needle) and/or FNA (22G needle). For lesion excision, the EnCor EnSpire ™ Breast Biopsy System, primarily used for biopsies in our department, was employed. Microcalcifications were excised using a stereotactical technique with mammographic guidance, while all other lesions were excised using ultrasound guidance. The goal was to excise each lesion in three sequential rounds of VAE, where the tissue samples were placed in three numbered containers. The first container included all tissues from the area where no remaining lesions were visible on mammography or ultrasound. The second container included a 360-degree biopsy sweep within the cavity of the first container, while the third container included an additional 360-degree biopsy sweep, further expanding the excision cavity.

2.3. Data Analysis

The primary outcome was diagnostic discrepancy between the initial biopsy (CNB or FNA) pathology report and the results from successive tissue containers at VAE, and any follow-up diagnosis within 2 years (same breast location).

Histopathological analysis followed the European guidelines for quality assurance of breast cancer screening and diagnosis [

12,

13], where lesions were categorized as follows; B1: normal breast tissue; B2: fibroadenomas/fibroadenosis, hemangiomas, and pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH); B3: papillomas, radial scars or complex lesions, FEA, ADH, and LN; and B5: ductal cancer in situ (DCIS) or invasive cancer. For cytological analysis, due to the inherent diagnostic limitations following FNA [

4], we utilized the four categories recommended by Wells et al. [

25]; C1: normal breast tissue, C2: fibroadenosis, C3: papillary formations, and C4: atypia, where malignancy could not be excluded.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of each lesion was summarized and stratified by diagnostic and treatment methods. Descriptive statistics for each lesion type were calculated for relevant continuous and categorical parameters. All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

A total of 208 patients were screened and enrolled between November 2019 and August 2022 after obtaining written informed consent. Following eligibility assessment and withdrawals, the final trial population comprised 194 patients with one lesion per patient, of whom 169 had undergone CNB and/or FNA before VAE. The mean patient age was 50.1 years, and the mean lesion size was 10.4 mm.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study population.

3.2. Change in Primary Diagnosis After FNA

Seventy-one patients had an initial FNA report. When we compared the FNA diagnosis with the final diagnosis after VAE, we found that 44 primary diagnoses (61%) remained unchanged, 17 (24%) were upgraded, and 10 (14%) were downgraded (

Table 2).

Of the 10 lesions initially diagnosed as normal tissue on cytology, eight (80%) were upgraded: four to fibroadenosis, three to papilloma without atypia, and one to myofibroblastoma.

Of the 11 lesions diagnosed as fibroadenosis on FNA, two (18%) were upgraded: one to papilloma without atypia and one to radial scar/sclerosing adenosis.

Of the 40 lesions with papillary formations on FNA, 30 (74%) were later diagnosed as papilloma without atypia on CNB or VAE. Five (10%) were upgraded to ADH (two lesions), LN (one lesion), and DCIS grade I (two lesions).

Regarding atypia diagnoses, two lesions were upgraded to invasive cancer, while the rest remained unchanged or were downgraded.

3.3. Change in Diagnosis After CNB

A total of 126 patients were diagnosed based on CNB, including 28 who underwent initial FNA. After histopathological analysis of VAE tissue, 89 lesions (71%) retained their initial diagnoses, 19 (15%) were upgraded, and 18 (14%) were downgraded (

Table 3).

In the B1 category, 62% (5/8) were upgraded; three cases were upgraded to papilloma without atypia, and two to radial scar/sclerosing adenosis. In the B2 category, 13% (5/37) were upgraded to B3, including one case to ALH, two to radial scar/sclerosing adenosis, and two to papilloma. In the B3 category, 10% (8/79) were upgraded: five to cancer (two to invasive cancer and three to DCIS grade I), and three to increased associated atypia (B4). In the B5 category, of the two lesions diagnosed as DCIS grade I, one was upgraded to DCIS grade II, and one was downgraded to ADH.

3.4. Comparison of Diagnoses Between Subsequent VAE Rounds

Of the 169 patients who underwent one round of VAE, 115 underwent a second round (68%), and 42 underwent a third round (26%). Due to technical issues, 11 lesions from the second-round group and four from the third-round group could not be discriminated from the first round. Consequently, the second-round group included 104 diagnoses, and the third-round group included 38.

Table 4 shows the comparison between the diagnoses after the subsequent VAE rounds. Of the 104 lesions in the second round, 96 (92%) retained their initial diagnosis or were classified as normal tissue. The largest discrepancy was observed in the B1 category, where two lesions (50%) were upgraded to papillomas in the third round. Additionally, five lesions (31%) in the B1 category were upgraded after the second round: two to papilloma, two to ADH, and one to LN. In total, 8/104 (8%) lesions were upgraded in the second round, and 2/38 (5%) upgraded in the third round.

3.5. Comparison of Diagnoses Between VAE and Surgery

A total of 13 patients underwent open surgery as the final treatment following decision-making during a multidisciplinary conference (

Table 5). Of these, seven patients were diagnosed with cancer after VAE (DCIS or invasive carcinoma), one with ADH, two with papilloma without atypia, one with fibroadenoma, one with radial scar/complex lesion, and one with adenomyolipoma.

One of the six (17%) non-malignant lesions was upgraded to malignancy after surgery from ADH to DCIS grade II. Three patients had only scar tissue in the specimen after the previous VAE, while the rest (9/13, 69%) had residual tissue from the targeted lesion, with no change in their diagnosis.

3.6. Cancer Diagnoses

A total of 10 cancer diagnoses were made after VAE and/or subsequent surgery.

The highest upgrade rate occurred in patients with ADH on CNB (3/12, 25%), followed by ADH diagnosed during VAE (1/5, 20%), ALH on CNB (1/5, 20%), atypia on cytology (2/10, 20%), papillary formations on cytology (3/40, 8%), and papilloma without atypia on CNB (2/50, 4%). Two patients had suspicious DCIS grade I after CNB, but only one maintained this diagnosis after VAE.

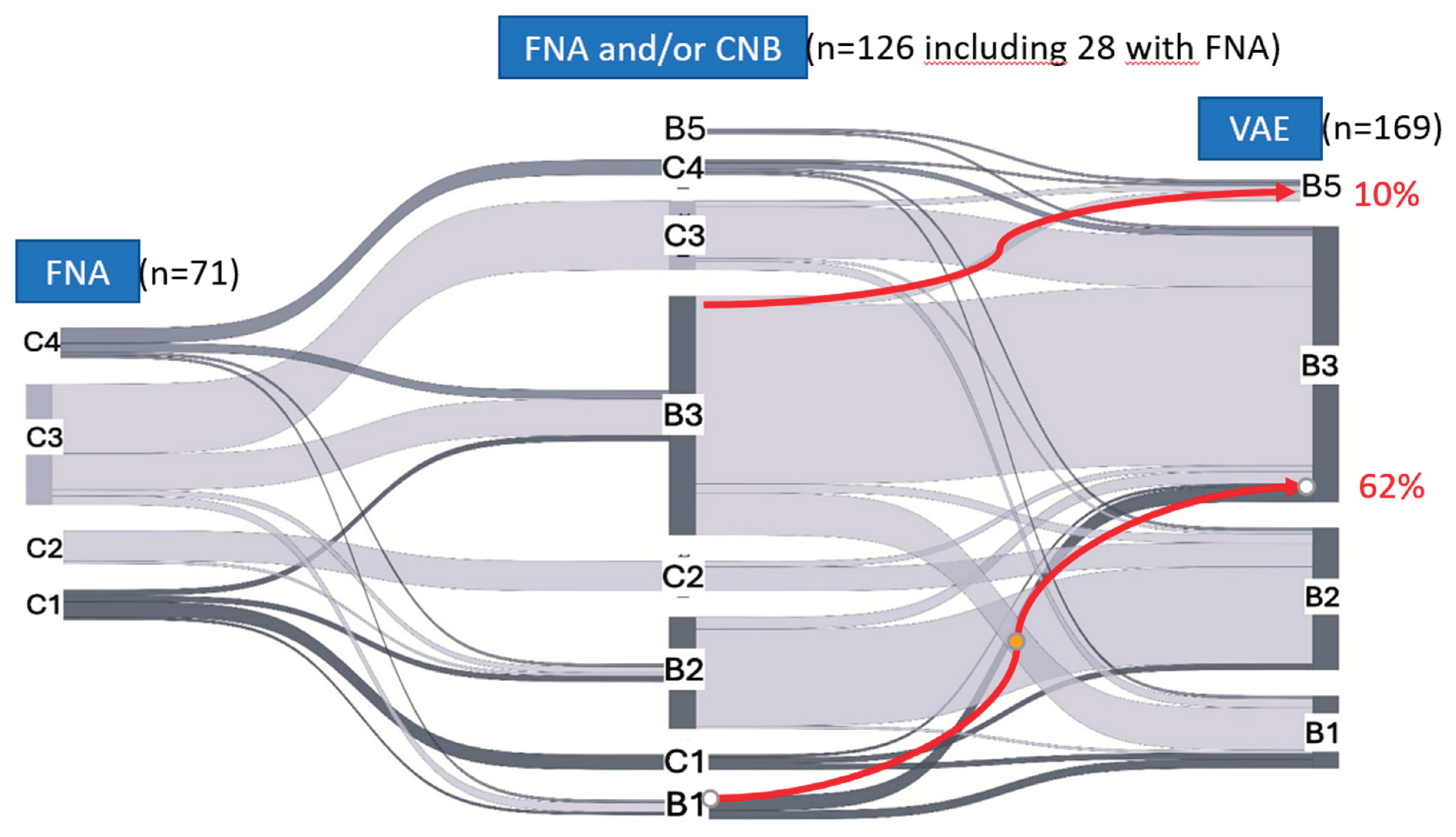

The changes in diagnoses among the different categories during subsequent biopsies are presented as a Sankey diagram (

Figure 1).

FNA, fine needle aspiration; CNB, core-needle biopsy; VAE, vacuum-assisted excision.

4. Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the Swedish randomized VAE trial, we found substantial diagnostic discrepancies between initial breast biopsy and subsequent VAE in lesions with uncertain malignant potential. The discrepancy rate was 29% for CNB and 38% for FNA. ADH on CNB was associated with the highest upgrade rate to malignancy (25%). These findings raise important considerations for biopsy selection and follow-up strategies in the clinical management of B3 lesions.

Previous studies, including one by Deb et al. [

26], have explored diagnostic discrepancies in benign and indeterminate breast lesions, though few have directly compared FNA and CNB to VAE. In our cohort, 8 of 10 lesions initially categorized as C1 on FNA were upgraded after VAE, reflecting key limitations of FNA such as inadequate sampling - often due to lesion consistency [

5] - and interpretive variability [

4]. These limitations can result in underdiagnosis, unnecessary repeat procedures, and potentially delayed treatment. Our findings reinforce the need to move away from FNA in favor of more reliable biopsy methods.

For CNB, the overall upgrade rate was 15%, with the highest discrepancy observed in B1 lesions (62%), likely due to similar sampling limitations as FNA [

27]. Prior studies have suggested that diagnostic accuracy in CNB improves with increasing numbers of cores [

28], but we were unable to assess this due to lack of documentation on core counts or needle gauge. Downgrade rates were 14% for both FNA and CNB, in line with previous reports [

26], indicating that both under- and over-classification remain common with standard biopsy.

The trial protocol included a three-round VAE procedure, which previously showed higher complete excision rates [

24], In this study, we also observed improved diagnostic concordance with multiple rounds. Notably, our only case of malignancy following VAE occurred in a patient with ADH on CNB who underwent only a single VAE round. This underscores the value of multiple VAE passes not only for therapeutic purposes but also for diagnostic reliability. Our results support the growing view that surgery may be safely omitted in selected ADH cases—provided that VAE is performed thoroughly, with at least three excision rounds.

ADH remains the B3 lesion with the highest and most variable reported upgrade rate (5%–50%) [

20]. Our observed rate of 22% is consistent with prior literature and highlights the heterogeneity across studies. Variability in inclusion criteria, interobserver diagnostic reproducibility [

29] and biopsy technique (e.g., core number, needle size) may all contribute to this range. Our findings support targeted excision of ADH using multi-round VAE as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery, aligning with a risk-adapted approach to care.

Papillomas diagnosed on CNB were the most common B3 lesion in our cohort. The observed upgrade rate to malignancy was low (4%), with only one case each of DCIS grade I and invasive carcinoma. Only one papilloma had associated atypia (ADH). These results are consistent with earlier studies reporting malignancy upgrade rates of 1.7%–12% for papillomas without atypia [

30,

31] and support current guidelines favoring imaging surveillance after VAB, in these cases when radiologic-pathologic concordance is present.

Our study has several limitations. First, there is potential for indication bias, as the initial biopsy method (FNA vs. CNB) was selected by the diagnosing radiologist [

32], possibly influenced by lesion characteristics not captured in this study. This could underestimate the true discrepancy of FNA if simpler lesions were preferentially selected for that method. Second, subgroup analyses were limited by the low frequency of some lesion types, such as lobular neoplasia, radial scars, and ADH. Third, we did not capture lesion morphology or imaging features, which are known to influence upgrade risk. Finally, this was a single-center study, although our results are consistent with international literature.

In an era prioritizing minimally invasive diagnostics and personalized care, our findings offer strong evidence to guide clinical decision-making. FNA is insufficiently reliable and should be avoided for indeterminate breast lesions. CNB, while more accurate, still carries a non-negligible risk of diagnostic discrepancy, especially in ADH. For ADH, multi-round VAE appears to provide both diagnostic and potential therapeutic value, offering a promising alternative to surgery. Papillomas without atypia may be safely managed with imaging follow-up if radiologic-pathologic concordance is confirmed. Future studies should focus on refining criteria for VAE-based management, incorporating imaging and lesion morphology to support individualized, evidence-based care.

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Region Stockholm and Karolinska Institute. The funding sources had no role in the data analysis, interpretation, writing of the article, or the decision to submit the article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The trial was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Board (dnr 2019-04096), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice.

Informed Consent Statement

The trial was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Board (dnr 2019-04096), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good clinical practice.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):146-51. . PubMed PMID: 3965932. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, et al. Benign Breast Disease and the Risk of Breast Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353(3):229-37. [CrossRef]

- Verma P, Sharma R, Sharma N, Gulati A, Parashar A, Kaundal A. Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology versus Core-Needle Biopsy for Breast Lesions: A Dilemma of Superiority between the Two. Acta Cytol. 2021;65(5):411-6. Epub 20210630. PubMed PMID: 34192704. [CrossRef]

- Fine-needle aspiration and core biopsy in the diagnosis of breast lesions: A comparison and review of the literature. CytoJournal. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Nassar A. Core needle biopsy versus fine needle aspiration biopsy in breast-A historical perspective and opportunities in the modern era. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2011;39(5):380-8. [CrossRef]

- Kooistra B, Wauters C, Strobbe L. Indeterminate Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration: Repeat Aspiration or Core Needle Biopsy? Annals of surgical oncology. 2009;16(2):281-4. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi G, Castellano I, D’Anna MR, De Matteis A, Milanesio L, Durando M, et al. B3-lesions of the breast: Risk of malignancy after vacuum-assisted breast biopsy versus core needle biopsy diagnosis. The breast journal. 2019;25(6):1308-9. [CrossRef]

- Grady I, Gorsuch H, Wilburn-Bailey S. Ultrasound-guided, vacuum-assisted, percutaneous excision of breast lesions: an accurate technique in the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(1):14-7. PubMed PMID: 15978438. [CrossRef]

- Darling ML, Smith DN, Lester SC, Kaelin C, Selland DL, Denison CM, et al. Atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ as revealed by large-core needle breast biopsy: results of surgical excision. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(5):1341-6 PubMed PMID: 11044038. [CrossRef]

- Hoorntje LE, Peeters PH, Mali WP, Borel Rinkes IH. Vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: a critical review. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(12):1676-83. PubMed PMID: 12888361. [CrossRef]

- Park HL, Hong J. Vacuum-assisted breast biopsy for breast cancer. Gland Surg. 2014;3(2):120-7. PubMed PMID: 25083505; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4115763. [CrossRef]

- Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Törnberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition--summary document. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(4):614-22. Epub 20071117. PubMed PMID: 18024988. [CrossRef]

- Lee AHS, Pinder SE. An overview of B coding of breast core biopsy categorisation and management implications. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2024;30(2):132-40.

- Bianchi S, Caini S, Renne G, Cassano E, Ambrogetti D, Cattani MG, et al. Positive predictive value for malignancy on surgical excision of breast lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) diagnosed by stereotactic vacuum-assisted needle core biopsy (VANCB): a large multi-institutional study in Italy. Breast. 2011;20(3):264-70. Epub 20110103. PubMed PMID: 21208804. [CrossRef]

- Bellini C, Nori Cucchiari J, Di Naro F, De Benedetto D, Bicchierai G, Franconeri A, et al. Breast Lesions of Uncertain Malignant Potential (B3) and the Risk of Breast Cancer Development: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study. Cancers. 2023;15(13):3521. [CrossRef]

- Richter-Ehrenstein C, Maak K, Röger S, Ehrenstein T. Lesions of "uncertain malignant potential" in the breast (B3) identified with mammography screening. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):829. Epub 20180816. PubMed PMID: 30115017; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6097423. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed ME, Rakha EA, Reed J, Lee AH, Evans AJ, Ellis IO. Predictive value of needle core biopsy diagnoses of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) in abnormalities detected by mammographic screening. Histopathology. 2008;53(6):650-7. PubMed PMID: 19076681. [CrossRef]

- Houssami N, Ciatto S, Bilous M, Vezzosi V, Bianchi S. Borderline breast core needle histology: predictive values for malignancy in lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3). Br J Cancer. 2007;96(8):1253-7. PubMed PMID: 17438578; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2360144. [CrossRef]

- Monib S, Mukerji S, Narula S. Vacuum-Assisted Breast Biopsy System: No Innovation Without Evaluation. Cureus. 2021;13(1):e12649. Epub 20210112. PubMed PMID: 33585135; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7876960. [CrossRef]

- Rubio IT, Wyld L, Marotti L, Athanasiou A, Regitnig P, Catanuto G, et al. European guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of breast lesions with uncertain malignant potential (B3 lesions) developed jointly by EUSOMA, EUSOBI, ESP (BWG) and ESSO. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2024;50(1):107292. Epub 20231127. PubMed PMID: 38061151. [CrossRef]

- Rageth CJ, O'Flynn EAM, Pinker K, Kubik-Huch RA, Mundinger A, Decker T, et al. Second International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174(2):279-96. Epub 20181130. PubMed PMID: 30506111; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6538569. [CrossRef]

- Rageth CJ, O'Flynn EA, Comstock C, Kurtz C, Kubik R, Madjar H, et al. First International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(2):203-13. Epub 20160813. PubMed PMID: 27522516; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5012144. [CrossRef]

- Elfgen C, Leo C, Kubik-Huch RA, Muenst S, Schmidt N, Quinn C, et al. Third International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Virchows Arch. 2023;483(1):5-20. Epub 20230617. PubMed PMID: 37330436; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10326140. [CrossRef]

- Zouzos A, Fredriksson I, Karakatsanis A, Aristokleous I, Foukakis T, Strand F. Effect of needle size on outcomes of vacuum-assisted excision of breast lesions. A randomized controlled trial. European journal of radiology. 2024;183:111895. [CrossRef]

- Wells CA, Ellis IO, Zakhour HD, Wilson AR. Guidelines for cytology procedures and reporting on fine needle aspirates of the breast. Cytopathology (Oxford). 1994;5(5):316-34. [CrossRef]

- Deb RA, Matthews P, Elston CW, Ellis IO, Pinder SE. An audit of 'equivocal' (C3) and 'suspicious' (C4) categories in fine needle aspiration cytology of the breast. Cytopathology (Oxford). 2001;12(4):219-26. [CrossRef]

- Masood Md S. Core Needle Biopsy versus Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy: Are There Similar Sampling and Diagnostic Issues? The breast journal. 2003;9(3):145-6. [CrossRef]

- Lacambra MD, Lam CC, Mendoza P, Chan SK, Yu AM, Tsang JYS, et al. Biopsy sampling of breast lesions: comparison of core needle- and vacuum-assisted breast biopsies. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;132(3):917-23. [CrossRef]

- Wadsten C, Rask G. Management and risk of upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia in the breast: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Scandinavian journal of surgery. 2024;113(3):229-36. [CrossRef]

- Willers N, Neven P, Floris G, Colpaert C, Oldenburger E, Han S, et al. The Upgrade Risk of B3 Lesions to (Pre)Invasive Breast Cancer After Diagnosis on Core Needle or Vacuum Assisted Biopsy. A Belgian National Cohort Study. Clinical breast cancer. 2023;23(4):e273-e80. [CrossRef]

- Nakhlis F, Baker GM, Pilewskie M, Gelman R, Calvillo KZ, Ludwig K, et al. The Incidence of Adjacent Synchronous Invasive Carcinoma and/or Ductal Carcinoma In Situ in Patients with Intraductal Papilloma without Atypia on Core Biopsy: Results from a Prospective Multi-Institutional Registry (TBCRC 034). Annals of surgical oncology. 2021;28(5):2573-8. [CrossRef]

- Lieske B, Ravichandran D, Wright D. Role of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy in the preoperative diagnosis of screen-detected breast carcinoma. British journal of cancer. 2006;95(1):62-6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).