1. Introduction

How does the universe build large structures from small components? This article on elementary algebra examines the set of natural numbers greater than 2,

, through their factorization into the set

of prime numbers, namely the subset of

that cannot be expressed as a product of two or more smaller numbers. In the analytic theory of prime arithmetic functions, we propose several probability mass and possibility distribution functions that are biased towards minor prime factors, alongside the well-known NBL (Newcomb-Benford Law). The NBL describes the frequency distribution of the leading digit in many naturally occurring numerical datasets written in standard positional notation [

1]; approximately

of these numbers start with the digit one, while below

begin with the digit nine [

2]. Do primes have similar laws?

It is pertinent to highlight how the theory connects prime numbers to NBL. In general, the sequence of prime numbers

is not Benford [

3]. Moreover, from the prime number theorem (see

Section 3.3), we can infer that the distribution of the first digit of prime numbers approaches uniformity as the scale factor increases [

4]. At this point, the research on the topic becomes twofold. On the one hand, although there is no uniform probability on any infinite countable set, i.e., there is no natural density, any well-defined density that satisfies certain intuitive conditions for prime numbers, e.g., lack of bias towards specific subsets of primes, will lead to NBL [

5]. Especially, prime numbers comply with NBL in both logarithmic and zeta densities [

6]; e.g., the set of primes with a leading digit of 1 has logarithmic density

(see subsection

of [

7]). On the other hand, we can generalize the NBL to cope with the primes by constraining the intervals of primes under consideration. The leading digits in the sequence of prime numbers follow a generalized NBL that accounts for the varying density of primes found within intervals of the form

[

8]. This approach reveals a scale-dependent

-power law that simplifies to a uniform distribution as the number of primes examined approaches infinity, i.e., as

vanishes. By focusing the analysis on intervals between two adjacent integral powers of ten and applying the density

, where

denotes the set of primes in

containing the subset

with a leading digit

d, we also arrive at NBL as s approaches infinity.

Notwithstanding, Kossovsky [

9] cautions that ” prime numbers do not care much about integral-powers-of-ten intervals [...] Surely they also do not pay any attention whatsoever to the particular number systems invented by the various civilizations scattered about randomly across the universe, as they float eternally up there well above all such lowly and arbitrary local inventions. Conclusions about the primes in digital Benford’s Law [...] do not interest the primes much.” We agree. While digit pattern analysis can reveal valuable insights that may not be evident in analytical studies or visual inspections, from a physics perspective, it is more functional to uncover new rules by examining the prime factor ordinals and exponents of an organic dataset. Despite confining the information to a particular domain, the acquired knowledge is more fundamental because it is independent of the number system and represents nature’s realities.

Suppose NBL reflects the occurrence probability of the digits in a sample of data represented in place-value notation. In that case, it is logical to expect a monotonically decreasing distribution regulating their prime factorization. To analyze the number theory associated with a dataset, we have introduced the SOE (Standard Ordinal-Exponent) representation of a number , an ordinal-ascending sequence of the prime factors by which N is divisible, where a prime ordinal and exponent (or multiplicity) represent the factor . The nexus between positional notation and primality lies in the number of distinct prime factors rather than in the individual digits. When written in positional notation, N’s size grows exponentially with respect to the average growth of , namely , and N’s representational cost is about , an information-theoretic measure of N’s energy, defined as .

Taking the SOE representation as a basis, we examined two representative natural datasets. The first dataset includes 300 entries of mathematical and physical constants (CT), while the second dataset contains 1,080 entries of world population data (WP). Both CT and WP datasets conform to the NBL. Datasets that comply with the NBL provide valuable insights when analyzed in relation to the chief functions of number theory. These include the energy function , the omega functions (number of distinct prime factors) and (total number of prime factors), the divisor functions (number of divisors) and (sum of divisors), as well as the distribution of rough and smooth numbers, the growth of highly composite numbers, the prime-counting function, and the totient function. We also study the internal growth of and after sorting the dataset, i.e., or . The joint analysis of these number-theoretic functions across natural datasets is a novel area of scientific research.

We acknowledge the existence of numerous theoretical findings in this field. The fundamental Erdos-Kac theorem in probabilistic number theory [

10] states that a standard normal distribution fits the probability distribution of

. This theorem supports the aforesaid link between positional and SOE notations, and hence between NBL and primality. Significantly, many of the theoretical concepts discussed in this work can be traced back to the works [

11,

12]. Additionally, relevant material included by [

13] in sections 2.6 and 2.7 also supports our discussion.

We have employed the Anderson-Darling, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Kuiper, Pearson’s chi-squared, Watson U², and Cramér-von Mises goodness-of-fit tests for statistical analysis. However, these methods often reject the null hypothesis even when there is explicit visual agreement, due to the sample size. To mitigate excess power in samples with more than 100 elements, we use the Relative Root Mean Squared Error (RRMSE

), which provides a normalized measure of the mean absolute deviation between the empirical and expected distributions, as described by [

14]. We base the thresholds for interpreting the outcomes on the guidelines from [

15].

The literature often suggests that physics emerges from mathematics, without proof. However, the set of laws governing ” the minor” we posit does sustain this hypothesis, which may reveal a fundamental aspect of the universe’s structure and dynamics. Much of the theory not addressed in this paper deserves similar attention. We do not cover areas such as the Möbius function, Liouville lambda, and radical functions intentionally to keep our study focused. Additionally, applying all current theories to a substantial collection of natural datasets would require many years. Other gaps identified by the reader are probably due to feasibility constraints rather than a lack of interest.

Specifically, our study presents a series of laws that confirm the significance of minor prime powers in subsets of , including the probability of a prime disregarding multiplicity within the factorization set, the probability and possibility of the SPO (Smallest Prime Ordinal), the probability of the number of participants in an interaction (in two versions), the distribution of a prime power divisor within the factorization set, the possibility of a prime power divisor relative to the dataset size, the general probability of a prime exponent, and the probability of the LPE (Largest Prime Exponent). We are not aware of any existing laws in the literature that encompass these findings. Additionally, we extend the applicability of our results and conclusions to real-life numerical datasets. In relation to ranges of naturals, CT, and WP, we also examine the informational energy of a prime, the growth of the number of primes, highly composite numbers, and totatives, as well as the density of the LPO (Largest Prime Ordinal), k-almost primes, and square-free k-almost primes, the growth of intratotatives and non-intratotatives, and the probability of the Greatest Common Divisor (GCD). From the information gathered, we derive a battery of rules to assess the naturalness of a dataset.

Another key result is that many distributions exhibit characteristics similar to those of a lognormal distribution. A random variable is lognormal if its logarithm follows a Gaussian distribution. Conversely, the exponential of a normal random variable results in a lognormal distribution. We often encounter the lognormal distribution when analyzing observational measurements in science and engineering. The usual distribution is, in fact, the lognormal distribution [

16], which is the maximum entropy probability distribution for a random variable whose logarithm has fixed mean and variance [

17]. Depending on these parameters, a lognormal variable’s distribution may either be monotonically decreasing or present a global peak (the mode). Moreover, we can adapt the lognormal model to fit the NBL distribution as the scale increases [

18]. In essence, the lognormal distribution encompasses the NBL distribution to such an extent that we can use it to test for statistical compliance with the NBL [

19].

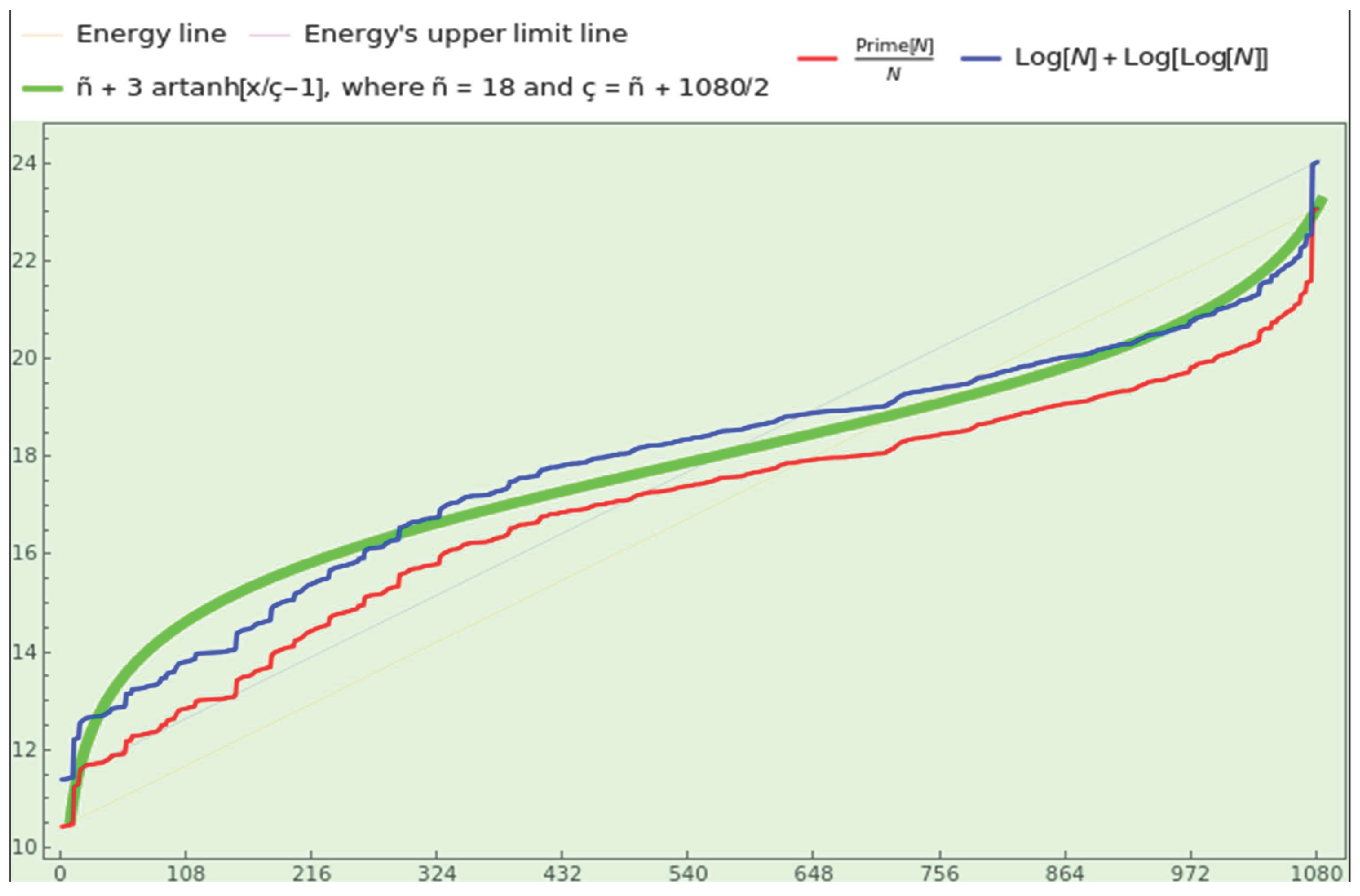

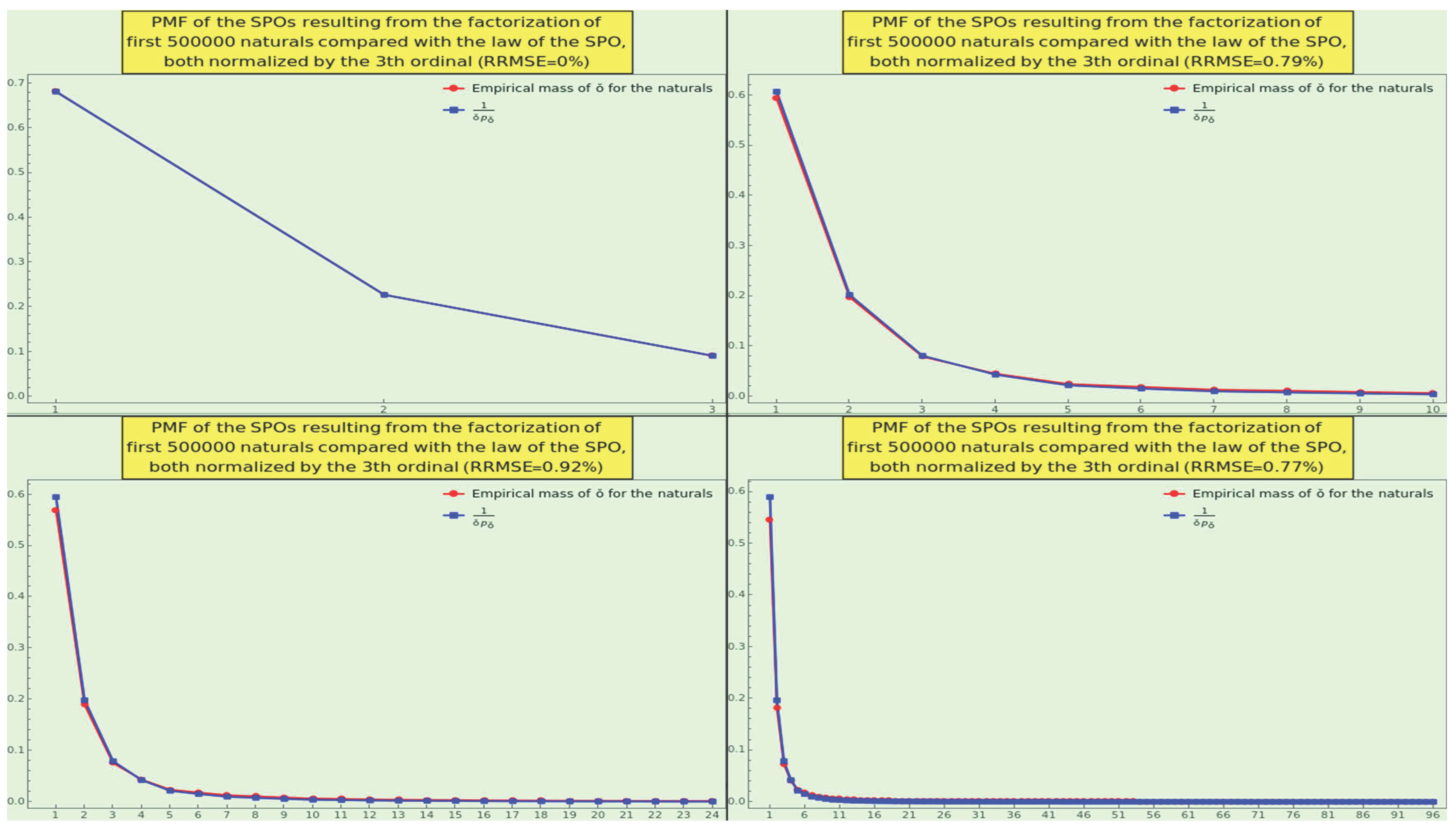

Lognormal distributions are instances of ” artanh distributions.” A random variable follows an artanh distribution if its logarithm delivers an LFT (Linear Fractional Transformation)

[

20]. When we zoom in sufficiently on the curve’s symmetry center, the artanh outline appears as a straight line. Likewise, it resembles an exponential or logarithmic curve near the boundaries when rotated. For example, when appropriately centered, scaled, and bounded (as shown in Figure 10 in green), the outline of the WP energy aligns with the conformal 1-ball model (see section 4 of [

21]); ” outside a coding source, the information resides on a harmonic scale, while inside, a logarithmic scale accommodates local Bayesian data.” Therefore, a plausible explanation for our observations is that the original data are generated globally from a harmonic scale. We then adapt the empirical data locally to our logarithmic scale through a conformal LFT transformation, allowing us to perceive a world of ” normality” in many instances.

This article has the following structure. We redefine the representational cost of a number and its informational energy, finding that a double logarithmic scale bridges the positional and SOE notations. We analyze the growth of divisibility and the distribution of prime numbers. Assuming the canonical PMF (Probability Mass Function), namely , we derive the law for the minor prime as well as the probabilistic and possibilistic laws for the SPO. Next, we review the density of almost-primes, the laws governing interactions, the growth of relative primes, and the law of the pairwise GCD. Further, we derive the laws governing the frequency of divisors (considering multiplicity), exponents, and the LPEs. Finally, we compare the theory embracing these topics with the prime factorizations of CT and WP, fragments of nature that generate number-theoretic patterns typical of . In particular, the relativistic conformal 1-ball model can explain the many observed artanh curve segments. The concluding remarks summarize the proposed laws and criteria we can use, in addition to NBL, to assess the naturalness of a dataset, and discuss the fundamental role they play as principles of a general theory of the minor prime factors.

2. Representational Cost, Information, and Energy

From an IT perspective, the cosmos must support a consistent numbering system while also being flexible and agile from an evolutionary standpoint. To achieve these goals, a crucial requirement is reasonable cost control.

We can define the cost

C of representing a number

in standard positional notation with radix

(

) [

22] as

The formula gauges how compacted a datum is.

We can approximately take the representational cost of

as (twice) the Hartley information

of sequences formed by

n successive selections from a set of

N elements. The elements or symbols of the set represent a fixed range of possible alternatives prior to each selection that cause ambiguity to the observer (receiver of the message, experimenter, or the like) [

23]. The total number of possible sequences of selections from the set is

[

24]. The formula

gives the amount of information conveyed by one among all these sequences, which is the only function satisfying the axioms of monotonicity (

) and additivity (

) for any proportionality constant

and radix

r. Choosing

,

, and

, we add the axiom of normalization

, so that the cost (i.e., inherent information) of the

r-ary (

) representation of

is

Indeed, the Hartley information is a normalized cost measured in bits (

), trits (

), or dits (

), depending on the coding radix. Note that this Hartley information interpretation of the cost is dual to the standard interpretation given to (

1). The latter is spatial, while the former is temporal, because it is the duration of the process of choosing among

N possibilities repeated at most r times. Ultimately, we must either minimize the space occupied or the time required to process the number, or both.

Nonetheless, the cost estimated by Equations (

1) and (

2) might be insufficient for calculation purposes. In arithmetic, the addition of a number to another that is several orders of magnitude smaller hardly alters the value of the former. What is the use of adding googol to 1, irrespective of the base? The biggest operands dominate the outcome of an unbalanced sum. In cosmology, for instance, distances and specific parameters require different techniques of approximate computation and estimation, allowing for adaptive precision [

25].

More particularly, numerical computation by machines often leads to subtle rounding errors that can become gross errors in specific scenarios. In IEEE 754 standard notation, this problem arises when the CPU represents the two terms in a sum using the same power of two in order to apply the distributive property of multiplication. If

, where

p is the number of bits used for the mantissa, everything is all right [

26]; otherwise, the consequences are unknown. Note that rounding errors are not specific to a system or notation; whenever we sum numbers that belong to too many different scales, or subtract one number from another that is very close, errors proliferate. To get around this situation, we should easily either access the order of magnitude of a number

N (e.g., explicitly prepending

to its representation) or calculate it as the exponential of its double logarithm, assuming that we can infer such data from its representation.

The point is that the double logarithmic and primality scales are linked. While the harmonic world connects with and logarithmic world through the asymptotic limit

where

is the

Nth harmonic number and

the Euler-Mascheroni constant, the harmonic series of primes (i.e., the depleted harmonic series comprised by the reciprocals of all prime numbers) and the double logarithmic scale are interrelated by the asymptotic limit [

12]

where

is the

Nth element of the harmonic series of primes and

is the Meissel-Mertens constant ([

13], section

). In other words, expression (

4) is the analog of (

3) for primes, where

and

M play the role of

and

, respectively.

Interestingly, , so that . Thus, we position the primality scale between the double logarithmic and double harmonic scales; M represents the separation between the double logarithmic and primality scales, and represents the separation between the primality and double harmonic scales.

The curves of these three scales grow very slowly. If we want, say, to halve the area between e and

, then

x must ebb down to

. In general, for a variable to scale by

, the variable must transform in a double geometric manner, i.e., according to a tetration scheme

. These ” second-order hyperbolic” scales enable efficient calculations and thrifty management of large numbers. What happens at the gigantic, coarse upper levels necessarily ignores the fine-grained detail of the lower levels. In particular, the double logarithm appears frequently in quite diverse disciplines of mathematics and physics (e.g., in studies of complexity concerning fundamental lattice problems [

27]).

The double logarithmic, primality, and double harmonic scales are intricately associated with factorization and divisibility. By the Erdos-Kac theorem of probabilistic number theory, they have, except for the separation constant, the same asymptotic order of growth as the average number

of distinct prime factors of

N, i.e.,

For example, , , , and .

In practice,

defines a coding scheme that uses the logarithm or harmonic number of the order of magnitude of

N rather than

N itself. Thus, if nature calculates the size of an operand

N via

,

1 should directly or indirectly involve

. Using a result from [

28], we can define this total cost, or ” energy” , in terms of a tight explicit pair of bounds.

Definition 1.

The law of the minor inherent information states that the energy

of is within the bracket

Mind that the relative weight of the double logarithm with respect to the energy fades away as

N goes to infinity. That is, as

N grows, its energy jumps less, and gaps tend to disappear. If we divide the bracket by

, then

What is the probabilistic meaning of

? It is the expected maximum load of balls across a collection of

bins after throwing

N balls into them one by one at random, where the sequence of target bins of throws is independent and identically distributed [

29]. For example, we expect a maximum of

balls across a million bins after randomly throwing a million balls into them.

Accordingly, we can redefine the cost (

2) of the

r-ary (

) representation of

as

A radix with a low average cost is economic (e.g., binary, ternary, or quaternary). We comply with the minimum information principle [

30] when the derivative of (

6) with respect to

r vanishes, obtaining Euler’s number e. This constant represents the optimal radix choice [

22].

In

Section 8, we analyze how the informational energy, and hence the representational cost, grows in real-world datasets.

4. The Canonical PMF

The probabilistic interpretation of the cumulative count of primes

10 is that the probability of a randomly chosen number

being prime as

N increases to infinity is in the limit

i.e., proportional to the expected frequency of

p as natural number and inversely proportional to its number of digits, thereby identifying the primes as outliers on a generic logarithmic scale that reifies the containment

.

Nevertheless, what is the probability mass of a natural? Allegedly, it is unknown, i.e., an integer has no natural density. However, [

21] (subsection 2.2 and section 5) postulates a probability inverse-square law, the canonical PMF for the nonzero integers, namely

which fulfills a bunch of fundamental properties, to wit, positive probabilities summing to one (if

Z vanishes, the probability is

), central symmetry, no bias (i.e., fair, undefined mean and variance), and minimal information. Additionally, it features constructability by superposition and emergence, constructability of the probability distribution by induction, separability of the entire probability space, discreteness of probability masses, and maximum randomness.

The significance of lies in its ability to express probability as normalized likelihood and derive the (global, rational) harmonic NBL and the (local, real, standard) logarithmic NBL.

The canonical complementary cumulative distribution function is proportional to the trigamma function, namely

By focusing on the integral of this function, the harmonic likelihood of

to fall into

is the ratio

where the ” harmt” (” harmonic unit” ) represents the natural unit of likelihood as global information, i.e.,

.

Call the most significant prime number

b the ” global base” . The harmonic scale becomes a concatenated list of ” quanta” , where a quantum is the most elemental entity computable globally. The probability mass of the range of quanta

regarding

b’s support is

where

and

. If

and

, we obtain quantum

q’s probability mass in base

b, i.e.,

Because , harmonic probabilities are fractions of a harmt.

When b goes to infinity, we can handle quanta like real values. Then, by focusing on the cumulative distribution function of this global PMF via integration, we turn to the local context represented by a coding source and define the logarithmic likelihood of

q falling into

as the ratio

Call digit to a locally computable elemental entity whose domain spans from the unit to

, where

is the coding space’s cardinality or ” radix” . The probability mass of the range of digits

regarding

r’s support is

where

and

. If

and

, we obtain the standard NBL, i.e.,

Again, probability is normalized information; since is the unit of likelihood as local information, logarithmic probabilities are fractions of a bit.

In summary, the canonical PMF enables us to derive both global and local versions of NBL and calculate natural densities that serve as a reference for estimating whether raw numerical sequences are natural. Besides, the canonical PMF tells us that the information we gain from an observation is proportional to its likelihood, represented on a harmonic or logarithmic scale.

At a high level of abstraction, the NBL is telling us that the minor numbers occupy more space in general, that is, their occurrence probability is higher than that of the large numbers. Do prime ordinals hold this rule? How does space share out among the elements of using the radixless SOE representation (see definition 2)? The first ordinal, , should be the most probable prime, i.e., that with more weight, space, worth, or mass. To what extent and how is the density of prime numbers unbalanced?

Now, we are seeking laws other than NBL characterizing subsets of the naturals.

9. Concluding Remarks

Let us take stock of this document, which aims to analyze the number-theoretic underpinnings of the prime factorization of unprocessed numerical data samples, including subsets of the natural numbers.

” For reasons that nobody understands, the universe is deeply mathematical,” says Steven Strogatz. He adds, ” There seems to be something like a code of the universe, an operating system that animates everything from moment to moment and place to place.” According to Wheeler, we should ” regard the physical world as made of information” because ” all things physical are information-theoretic in origin, and this is a participatory universe.” The information managed by such a universal code would be numeric, suggesting that numbers are not merely lifeless symbols but rather integral to living things, as Benford remarked in the closing sentences of his article.

A critical observation is that the physical information we receive is seldom linear. NBL indicates that the minor digits occur more frequently than the significant digits. Since digits represent numbers and numbers convey information, we can infer that the cosmos maintains an entropic balance by presenting numerous elements of low informational value alongside a few of high informational value. Then, how is information organized? Furthermore, should we not recognize this pragmatic preference for frugality in the canonical factorization of a raw numerical dataset as a bias towards minor prime power factors?

The informational representational cost of a natural N is proportional to its energy , which grows as . Based on the idea of resource economy, nature likely first considers the ” price” of the operands before proceeding with the subsequent calculations. For example, accurately adding numbers that differ by no more than two orders of magnitude makes sense. However, the efficiency of accurately summing 2 to () is questionable. Consequently, the logarithm of a numeral (or its harmonic number) is either explicitly incorporated in its representation or implicitly expressed by the number of prime factors. In this case, some form of the canonical factorization of the naturals might be ” real” .

The SOE representation introduces a subtle difference from the canonical factorization representation. Both share many advantageous properties, including compactness and scale invariance, due to the explicit form of the exponents. Functions like omega ( and ) and sigma divisors ( and ) are easily computable, and the prime and totative counting functions are tractable. However, the SOE representation emphasizes ordinals rather than the primes themselves. Many of our proposed rules pertain to prime ordinals; by making their accessibility straightforward, we can handle elemental information of practical character.

We have also reviewed the growth of divisibility through the average sum of divisors and the average sum of the sum of positive divisors functions. In this context, the concept of a highly composite number is noteworthy. The abundant composition scale progresses less steeply than the primality scale. The primes, governed by the prime number theorem, share a growth order with the logarithmic integral function, the quotient of sums of divisors, and the Chebyshev functions, allowing us to regard the prime counting function as a quantum energy level on average.

We describe the meaning of a quantum in

Section 4. The PMF that states the probability of a nonzero integer

Z as

allows us to explain that probability is normalized representational information and to derive the harmonic NBL and the standard NBL. The logarithmic scale is local, relating more to our perception than to the actual production of information generated from the global harmonic scale. Moreover, the canonical PMF links directly or indirectly to all the factorization laws we have addressed. For instance, the law of the minor prime (3) is equivalent to the probability of a quantum with a specific base (

14); a quantum and a prime constitute the same computational entity. Likewise, the law of the minor GCD (8) and the canonical PMF are essentially the same declaration.

The table below presents a comprehensive set of laws concerning the prime factorization of natural numbers. The law of the minor energy (first row) highlights the connection to the notion of likelihood and the prominence of the lowest informational entities. The law of the minor pairwise GCD (second row) and the possibility law of the minor prime disregarding multiplicity (third row) are well-known. The last nine rows of the table address the probability of a prime disregarding multiplicity within the factorization set, the probability and possibility of the SPO, the number of participants in an interaction (considering or not multiplicity), the probability and possibility of a prime power divisor, the probability of an exponent, and the probability of the LPE. Laws 3, 5, 11, and 7 disregard multiplicity, whereas 6, 9, 10, 12, and 13 consider multiplicity. These nine PMFs, unpublished to our knowledge, serve to illuminate the central idea that the natural preference for the small intensifies in the primality frequency; the smallest primes cover more ground in relative terms than that assigned by NBL to the smallest digits.

| Law of the minor ... |

Description |

Limiting value |

| Energy of a quantum (law 1) |

|

|

| Pairwise GCD (law 8) |

|

|

| Prime relative to the factorized numbers (law 4) |

(possibility) |

(possibility) |

| Prime relative to the factorization set

(law 3) |

|

|

| SPO (probabilistic law 5) |

|

|

| SPO (possibilistic law 11) |

(possibility) |

(possibility) |

| Number of interactors considering

multiplicity (law 6) |

|

|

| Number of interactors disregarding

multiplicity (law 7) |

|

|

| Prime divisor relative to the factorization set

(law 9) |

|

|

| Prime divisor relative to the factorized numbers

(law 10) |

(possibility) |

(possibility) |

| Exponent (law 12) |

|

|

| LPE (law 13) |

|

|

We have conducted an in-depth analysis of a pair of datasets that we see as archetypal examples of non-manipulated data, expecting the lessons learned to be generalizable to any natural dataset. We have reassured ourselves that NBL and CT, as well as NBL and WP, are aligned. The fact that we cannot reject NBL-conformance is good news, given the size of these samples, which contain 300 and 1080 numerals, respectively. However, CT is not only thinner but also more fabricated than WP. The fact that the CT dataset has 8 SPEs greater than 1 () indicates that it has been manipulated to some degree, as natural datasets typically have a much lower percentage, according to our experience. Let us say that CT is a repository of quasi-random numerals. In contrast, WP is a repository of mere raw numerical data.

The information gathered from our observations suggests several conditions for assessing the naturalness of a dataset. Among these requirements, several refer to a generic dataset DS. The requirements marked with an asterisk apply only to datasets of considerable size, specifically those with more than 1000 entries. Criteria involving the symbol of approximation ”≈” lead to avoiding rejection if the error is below

.

| Criterion |

Description |

| NBL conformance |

The PMF of the first digits obeys (16) |

| Informational energy |

Growth profile of is an artanh curve segment |

| Growth of the summatory of the prime factors ordinals |

Growth profile of

is an artanh curve segment |

| Odds of the rough against smooth numbers in DS |

|

| Rough/smooth equilibrium in DS |

to hold

=

|

| Growth of SPOs, GMOs, and LPOs |

Log-growth profile of these curves is an artanh curve segment |

| Distribution of the omega functions * |

The PMFs of and obey

a lognormal distribution |

| Growth of the number of prime factors with multiplicity |

Growth profile of is an artanh curve segment |

| Difference between the omega functions of DS |

,

where is the size of DS |

| Histograms of the divisor functions |

The histograms of and outline

an hyperbola |

| Growth of the sum of divisors function * |

Growth profile of is an artanh curve segment |

| Growth of the highly composite counting function * |

Log-growth profile of highly composition is an artanh segment |

| Comparison between the growths of energy and primes |

Growths of of and are

even |

| Growth of the prime counting function * |

Growth profile of is an artanh curve segment |

| Growth of the DS-prime counting function |

Growth profile of

proportional to

|

| Criterion |

Description |

| Distribution of primes |

The PMF of the primes obeys law 3 |

| Distribution of the SPOs |

The PMF of the SPOs obeys law 5 |

| Distribution of the LPOs |

The PMF of the LPOs obeys a lognormal distribution |

| k-almost DS-prime zeta functions * |

profile is like that of Figure 39, top-left

in gray |

| Square-free k-almost DS-prime zeta functions * |

profile is like that of Figure 40, top-left

in gray |

| k-warps of the 3D DS-prime zeta function values |

The plot of

form an arch when k is fixed |

| Growth of the Euler’s phi (or totient) function * |

Growth profile of is an artanh curve segment |

| Rate of DS intratotatives |

|

| Growth constant of DS intratotatives |

|

| Growth constant of DS non-intratotatives |

|

| Average growth of DS intratotatives |

grows as the straight line , where

|

| Distribution of the pairwise GCD |

The pairwise GCD PMF obeys law 8 |

| Distribution of divisors with multiplicity |

The PMF of the prime divisors weighted by the exponent obeys law 9 |

| Relative frequency of divisors with multiplicity |

The possibility of the prime divisors weighted by the exponent obeys

law 10 |

| Distribution of the prime exponent |

The PMF of the prime exponents obeys law 12 |

| Distribution of the LPE |

The PMF of the LPE obeys law 13 |

All these guiding principles converge on betting for the minor numbers. In general, an ordered set situates the most probable elements close to the origin, while the rare elements are far from the origin. The element of surprise of these hefty numbers counters the fact that, on average, they are level, anodyne, and predictable. The natural (unstable and perturbable) equilibrium is feasible by balancing many small likely elements with a few large unlikely ones.

In light of our findings, the lognormal distribution is a widespread phenomenon. For instance, does there exist a general distribution of a discrete random variable

associated with the number of distinct prime factors? Yes, the lognormal distribution. Does there exist a general distribution of a discrete random variable

associated with the k-almost primes, square-free or not, for a given number of participants in an interaction? Yes, the lognormal distribution. However, the lognormal distribution is not a panacea. We cannot fit the PMF of the k-almost prime zeta functions to the lognormal distribution for specific natural samples (see

Figure 21,

Figure 39,

Figure 22, and

Figure 40 at the top-left). The most we can do to approach such profiles is to utilize the so-called generalized gamma distribution, with four parameters.

An LFT requires precisely four parameters. Since we can express the logarithm of an LFT in terms of the artanh function, an artanh distribution fits all the plots we display in this article. Because an LFT becomes a linear map when its denominator is one, the artanh distribution contains the lognormal one. Curve segments of artanh approach linearity, exponential or logarithmic growth, and exponential or logarithmic (decelerating) decay with the appropriate displacement, rotation, inversion, and scale. Further, the importance of artanh lies in its role as the protagonist function of the conformal 1-ball model, which explains the information-preserving mapping between the external harmonic world and our internal logarithmic world.

The laws we have reviewed or disclosed, as well as the analysis of the empirical results, point to a latent endurance strategy. Concerning the outcomes of natural selection, John David Barrow in ” Pi in the Sky” claims that ” Their primary characteristic is persistence, or stability, rather than simplicity.” By weighing many lighter (or shorter) things against a few heavier (or longer) ones, the universe rejects uniformity in favor of dynamism, not only for rising stability but also for operability as a form of survival. Permanence, regularity, calculability, and balance between homogeneity and heterogeneity are inherent, ubiquitous values that nature fosters to guarantee evolution.

Assuming that nature is prone to managing small significands, one can infer an endemic preference for the minor primes, too. However, this affirmation needed supporting evidence. The primality setting we have focused on demonstrates that, for instance, number one appears most frequently as the leading prime ordinal and exponent, and the probability mass for two, three, etc., as ordinal and exponent, decreases significantly. Large ordinals are not common. High exponents are extremely occasional. We conclude that SOE is plausibly a fundamental representation, that the laws of the minor primes rule the natural datasets, and that the prevalence of the small over the large, at proper proportions, constitutes a tenet of the cosmos’ behavior.

Figure 1.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every natural number in the range , where M=2 (top-left), M=3 (top-right), M=4 (bottom-left), and M=5 (bottom-right).

Figure 1.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every natural number in the range , where M=2 (top-left), M=3 (top-right), M=4 (bottom-left), and M=5 (bottom-right).

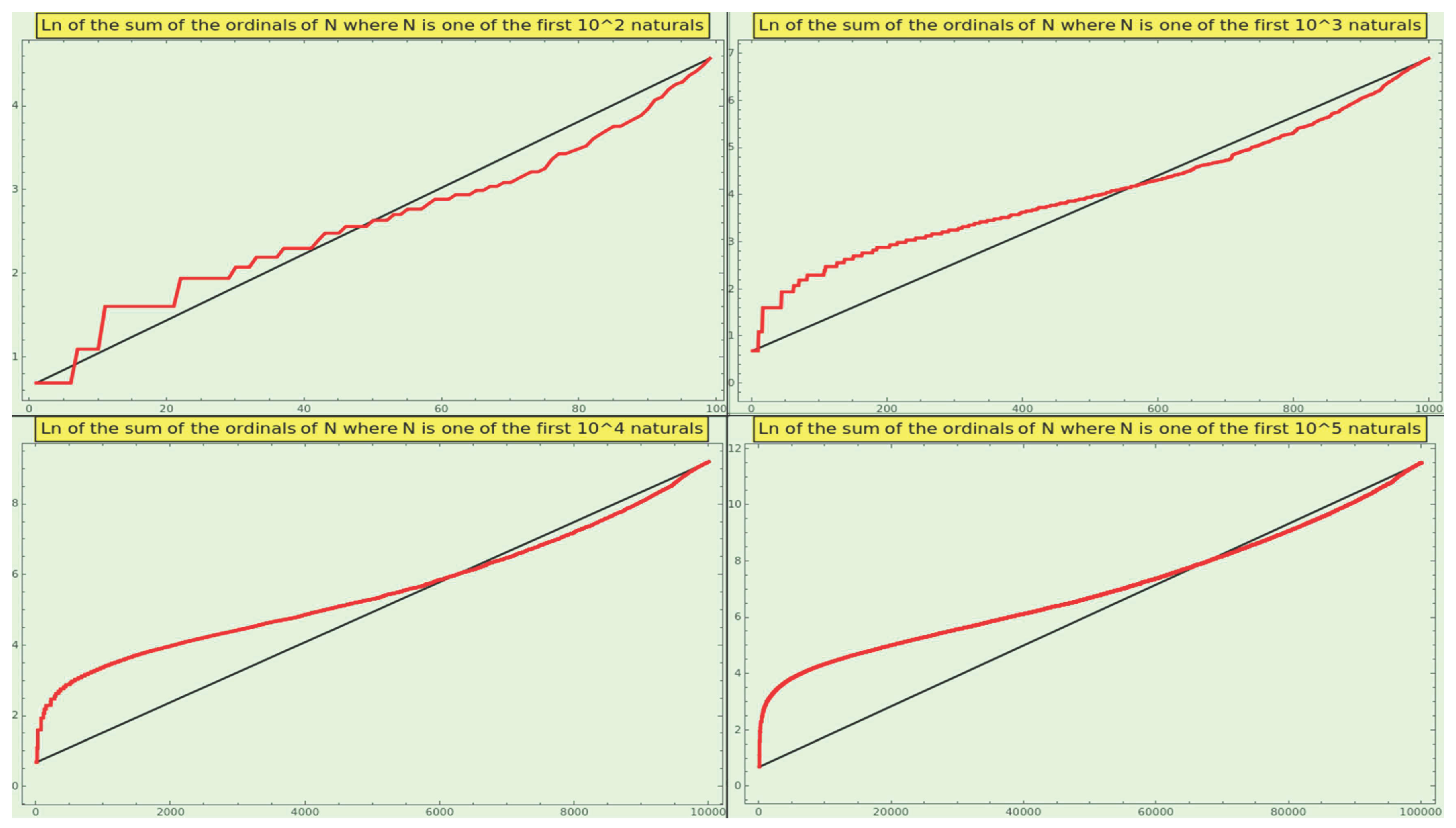

Figure 2.

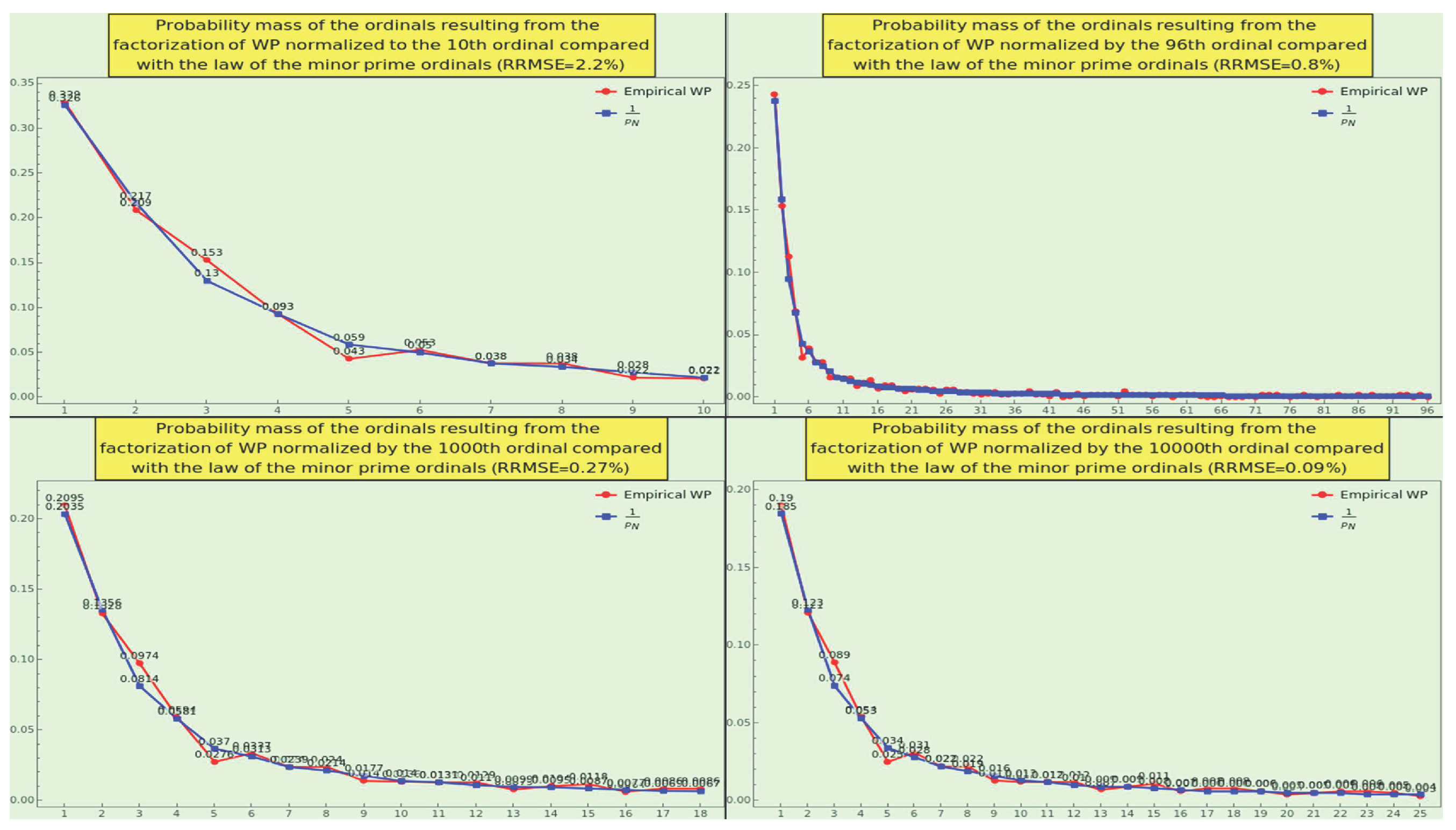

Plot of the probability masses of the prime factors (disregarding the exponents) resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers between and the Mth prime, where M=10 (top-left), M=100 (top-right), and M=100 (bottom-left). The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the definition 3’s formula decreases as M goes to infinity. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal, o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The plot in the bottom-right corner shows the empirical and expected probability measures for the prime ordinals resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers between and .

Figure 2.

Plot of the probability masses of the prime factors (disregarding the exponents) resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers between and the Mth prime, where M=10 (top-left), M=100 (top-right), and M=100 (bottom-left). The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the definition 3’s formula decreases as M goes to infinity. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal, o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The plot in the bottom-right corner shows the empirical and expected probability measures for the prime ordinals resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers between and .

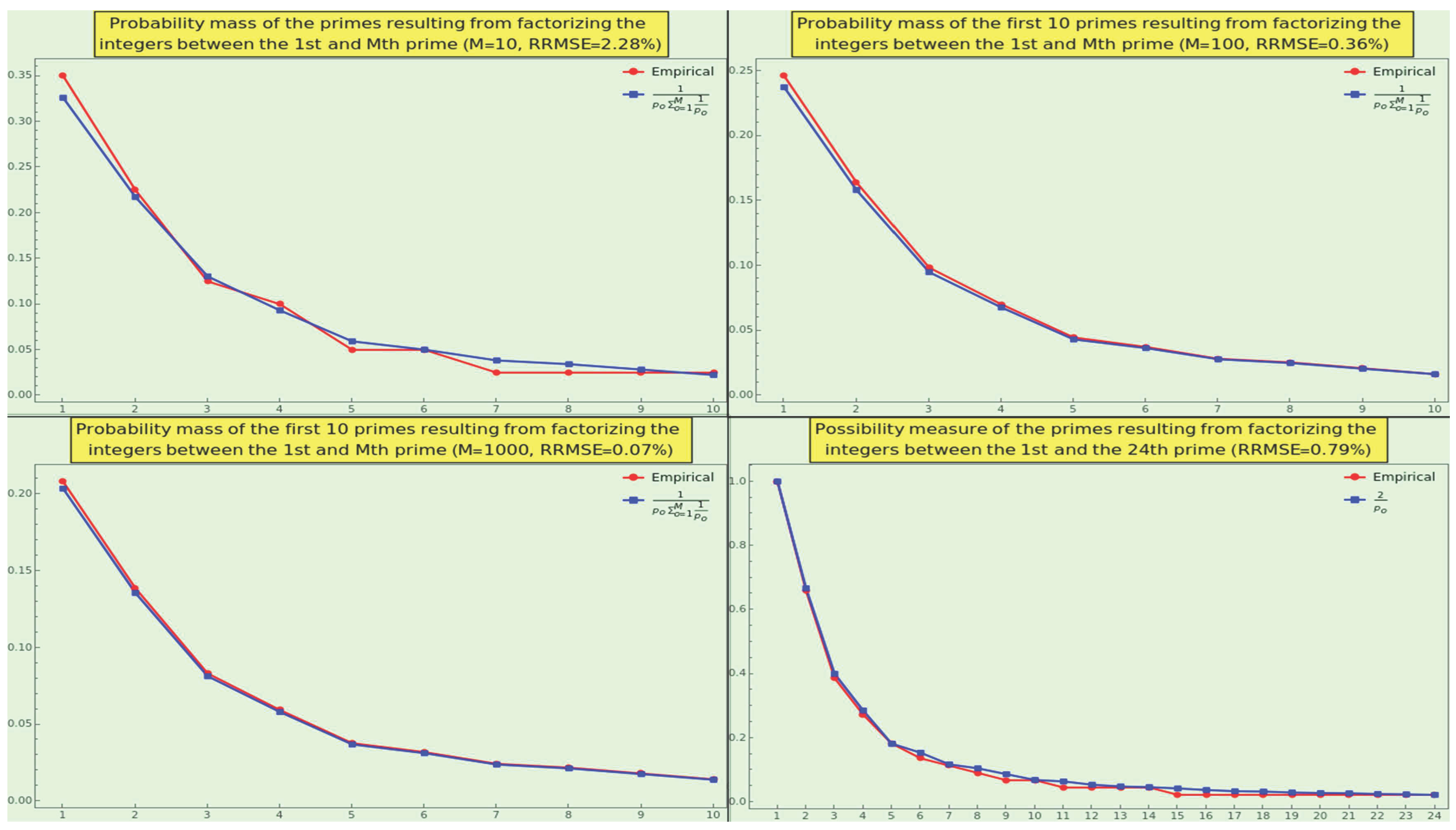

Figure 3.

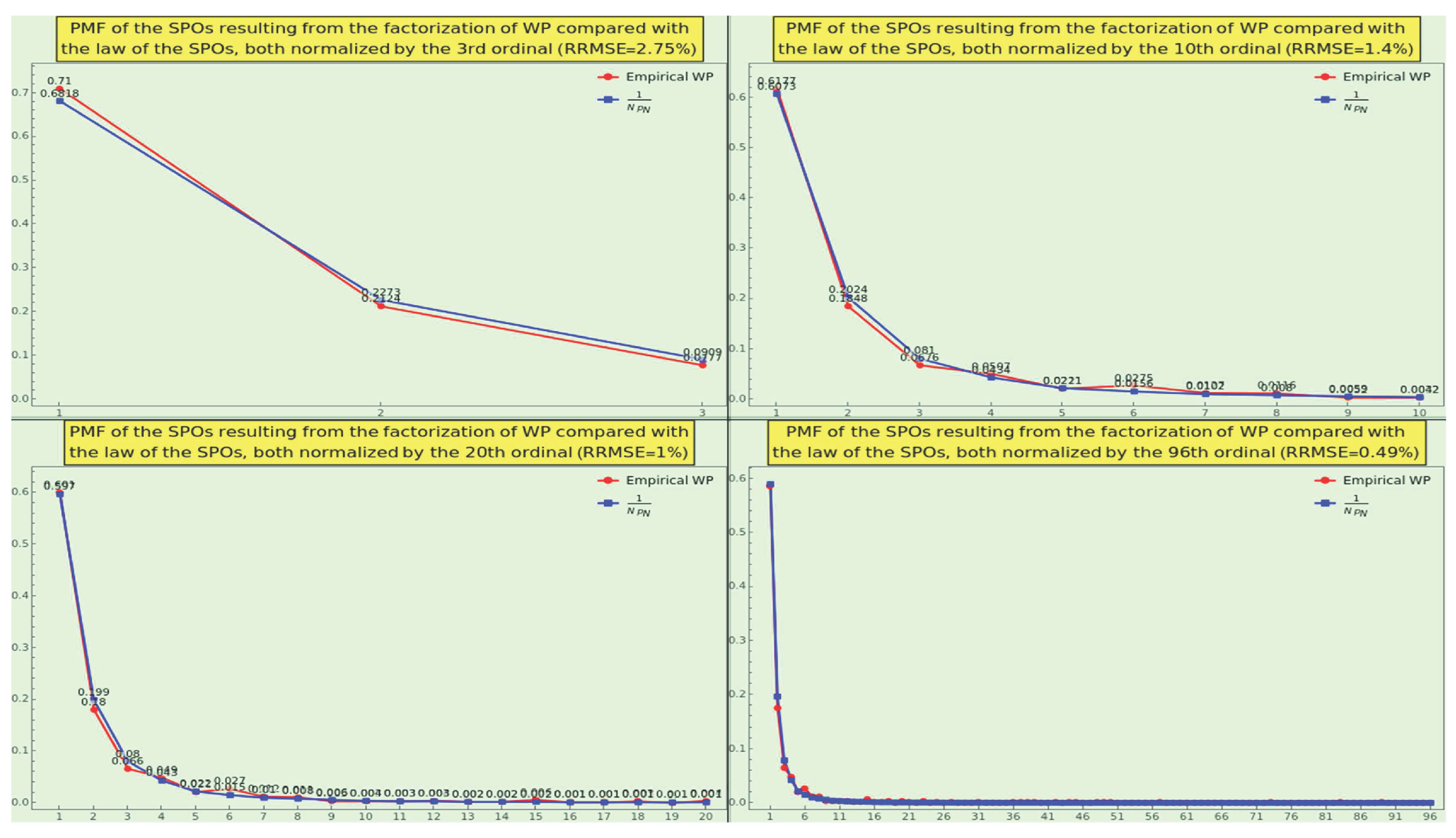

Take the naturals ranging from 2 to 500000, factorize, and calculate the distribution of the SPOs. Then, normalized for different values of ” the base” , namely 3 (top-left), 10 (top-right), 24 (bottom-left), and 96 (bottom-right). These PMFs adhere to the law 5; in particular, for 3 elements the empirical and theoretical distributions coincide (RRMSE). The x-axis indicates the SPO, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 3.

Take the naturals ranging from 2 to 500000, factorize, and calculate the distribution of the SPOs. Then, normalized for different values of ” the base” , namely 3 (top-left), 10 (top-right), 24 (bottom-left), and 96 (bottom-right). These PMFs adhere to the law 5; in particular, for 3 elements the empirical and theoretical distributions coincide (RRMSE). The x-axis indicates the SPO, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

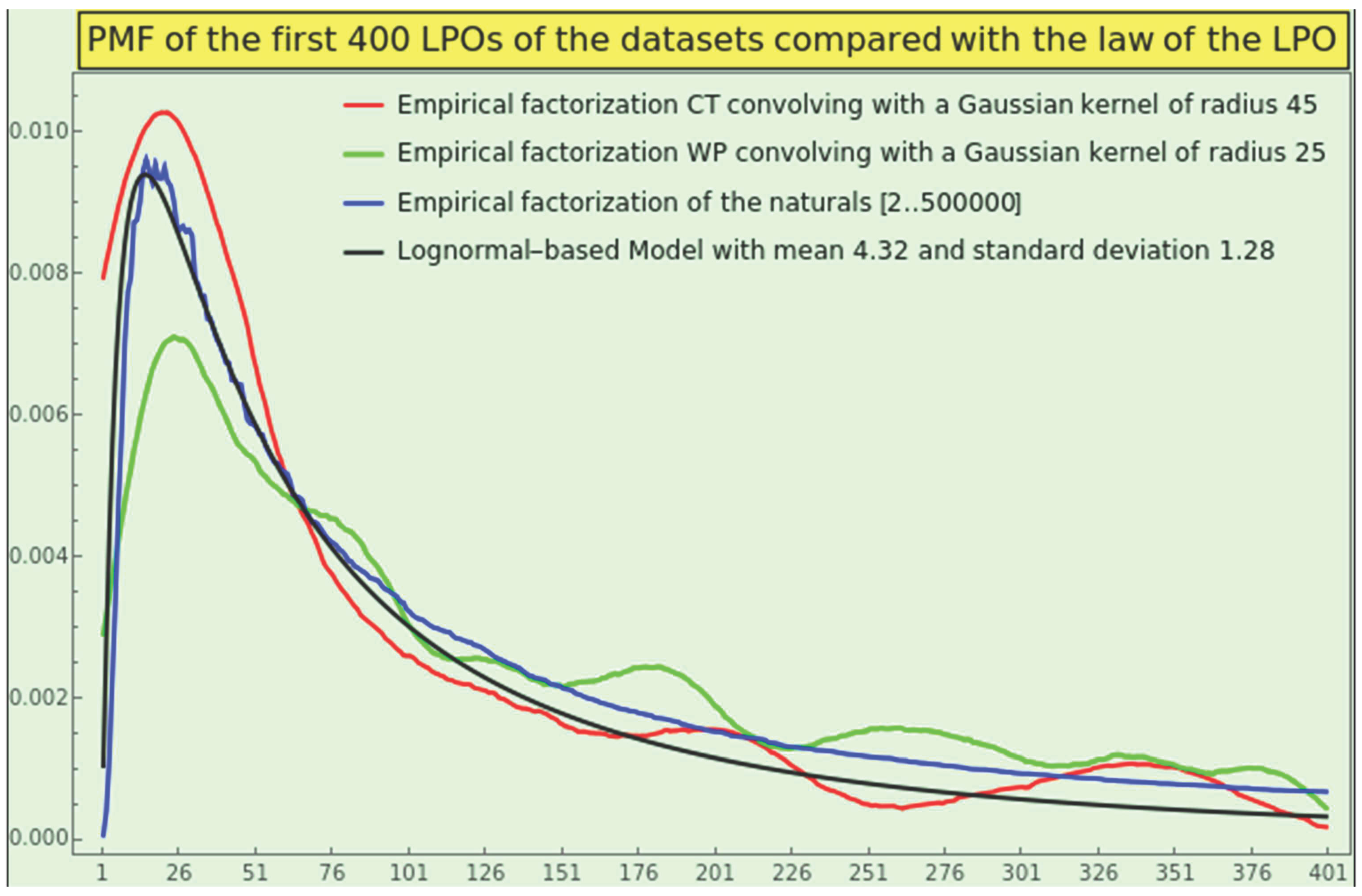

Figure 4.

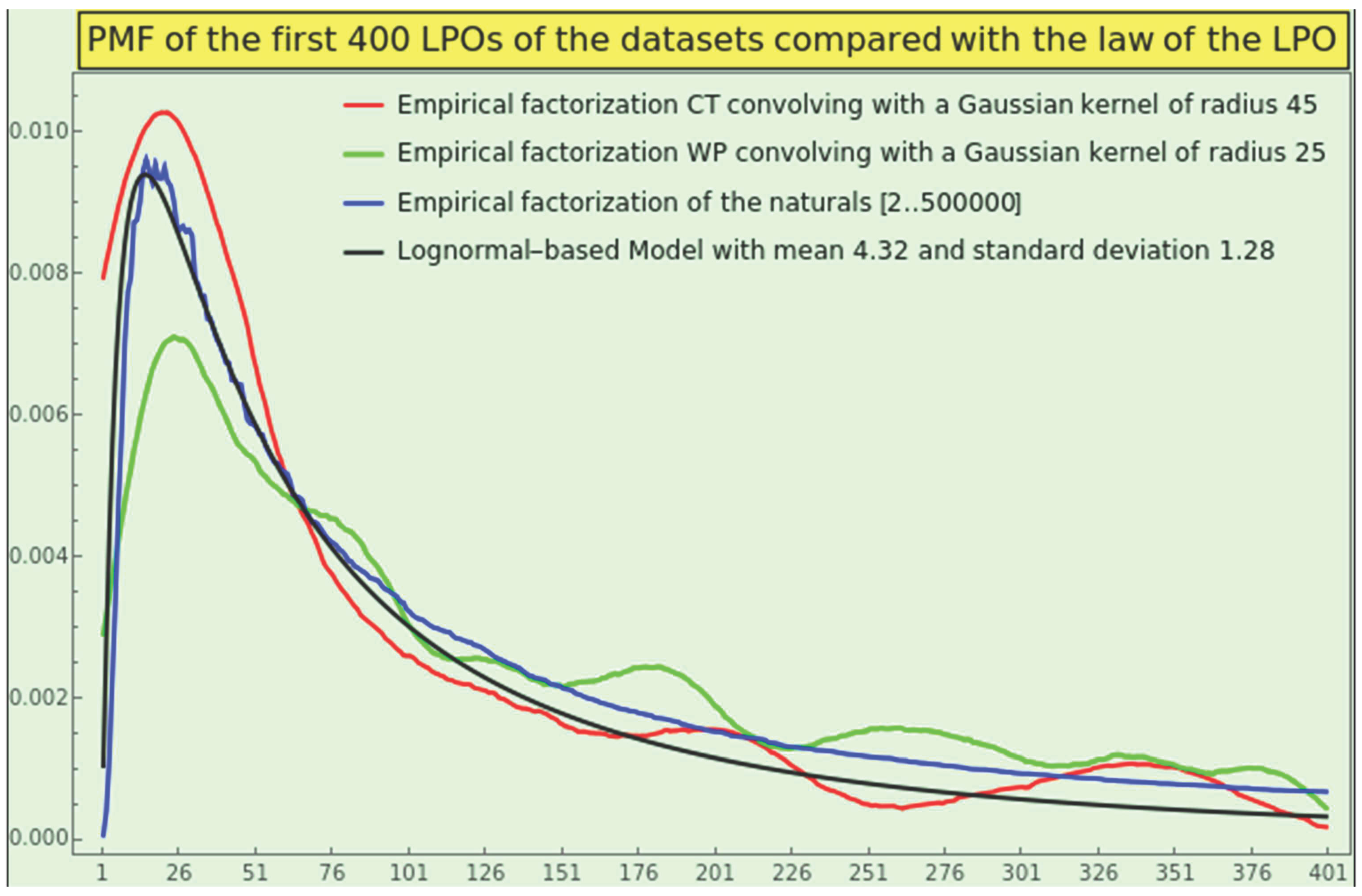

Take the naturals ranging from 2 to 500000, factorize, and calculate the distribution of the LPOs. Restrict the resulting distribution to a ” base” of 400 ordinals. Repeat the process with the CT dataset, and additionally calculate the convolution with a normal filter of radius 45 elements. Repeat the process with the WP dataset, and additionally calculate the convolution with a normal filter of radius 25 elements. Normalize the distributions of the three datasets (the naturals, CT, and WP) to obtain the corresponding PMFs of LPO. Then, fit the natural PMF to a lognormal model; a mean of 4.32 and a standard deviation of 1.28 yield excellent accuracy with an RRMSE of . Note that the natural PMF and the lognormal model have fat tails, meaning that the PMF decreases algebraically rather than exponentially as we get close to 400. Between the empirical plots of the naturals and CT, the RRMSE is . Between the lognormal model and the empirical CT plot, the RRMSE is . Between the empirical plots of the naturals and WP, the RRMSE is . Between the lognormal model and the empirical plot of WP, the RRMSE is .

Figure 4.

Take the naturals ranging from 2 to 500000, factorize, and calculate the distribution of the LPOs. Restrict the resulting distribution to a ” base” of 400 ordinals. Repeat the process with the CT dataset, and additionally calculate the convolution with a normal filter of radius 45 elements. Repeat the process with the WP dataset, and additionally calculate the convolution with a normal filter of radius 25 elements. Normalize the distributions of the three datasets (the naturals, CT, and WP) to obtain the corresponding PMFs of LPO. Then, fit the natural PMF to a lognormal model; a mean of 4.32 and a standard deviation of 1.28 yield excellent accuracy with an RRMSE of . Note that the natural PMF and the lognormal model have fat tails, meaning that the PMF decreases algebraically rather than exponentially as we get close to 400. Between the empirical plots of the naturals and CT, the RRMSE is . Between the lognormal model and the empirical CT plot, the RRMSE is . Between the empirical plots of the naturals and WP, the RRMSE is . Between the lognormal model and the empirical plot of WP, the RRMSE is .

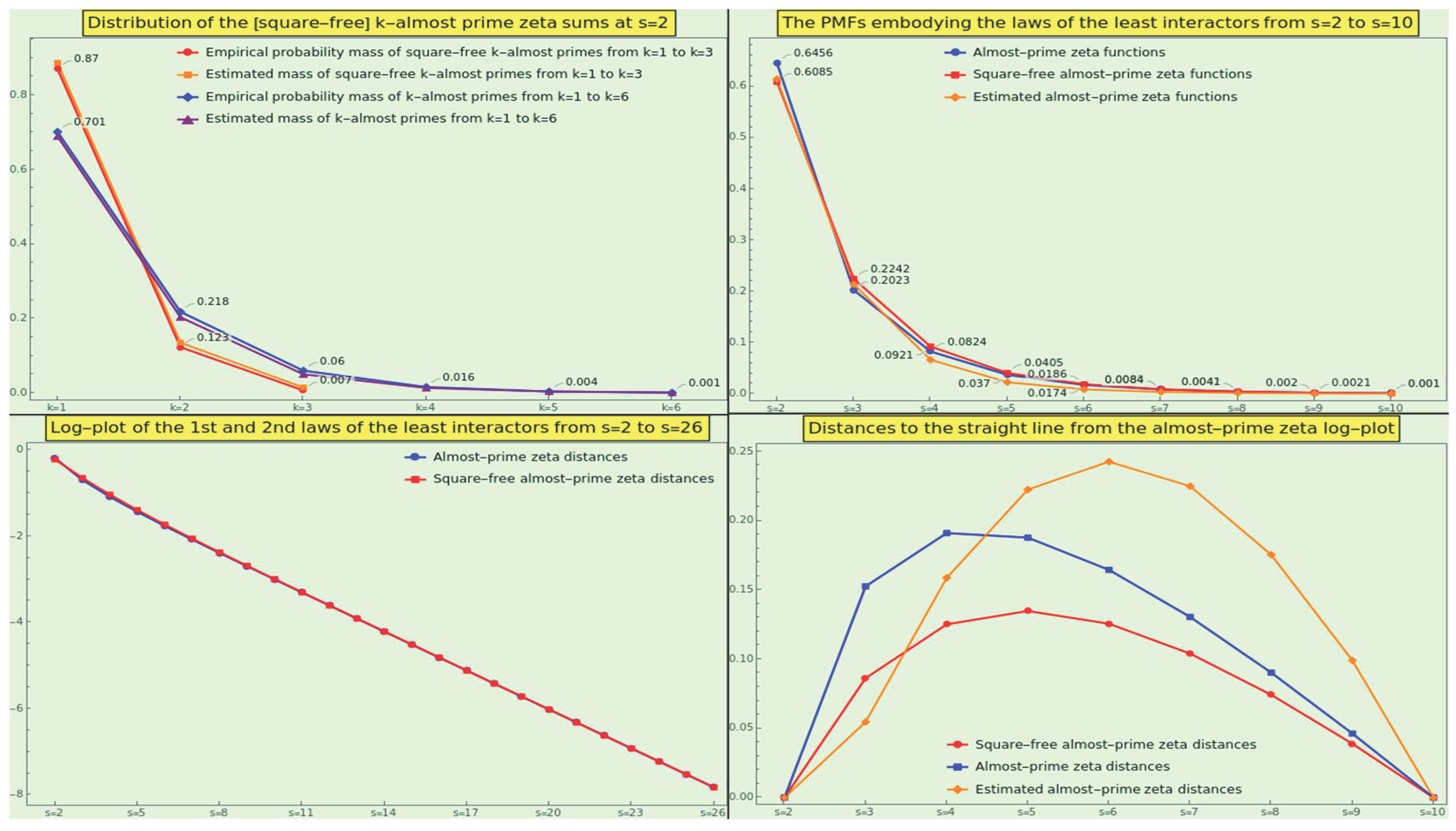

Figure 5.

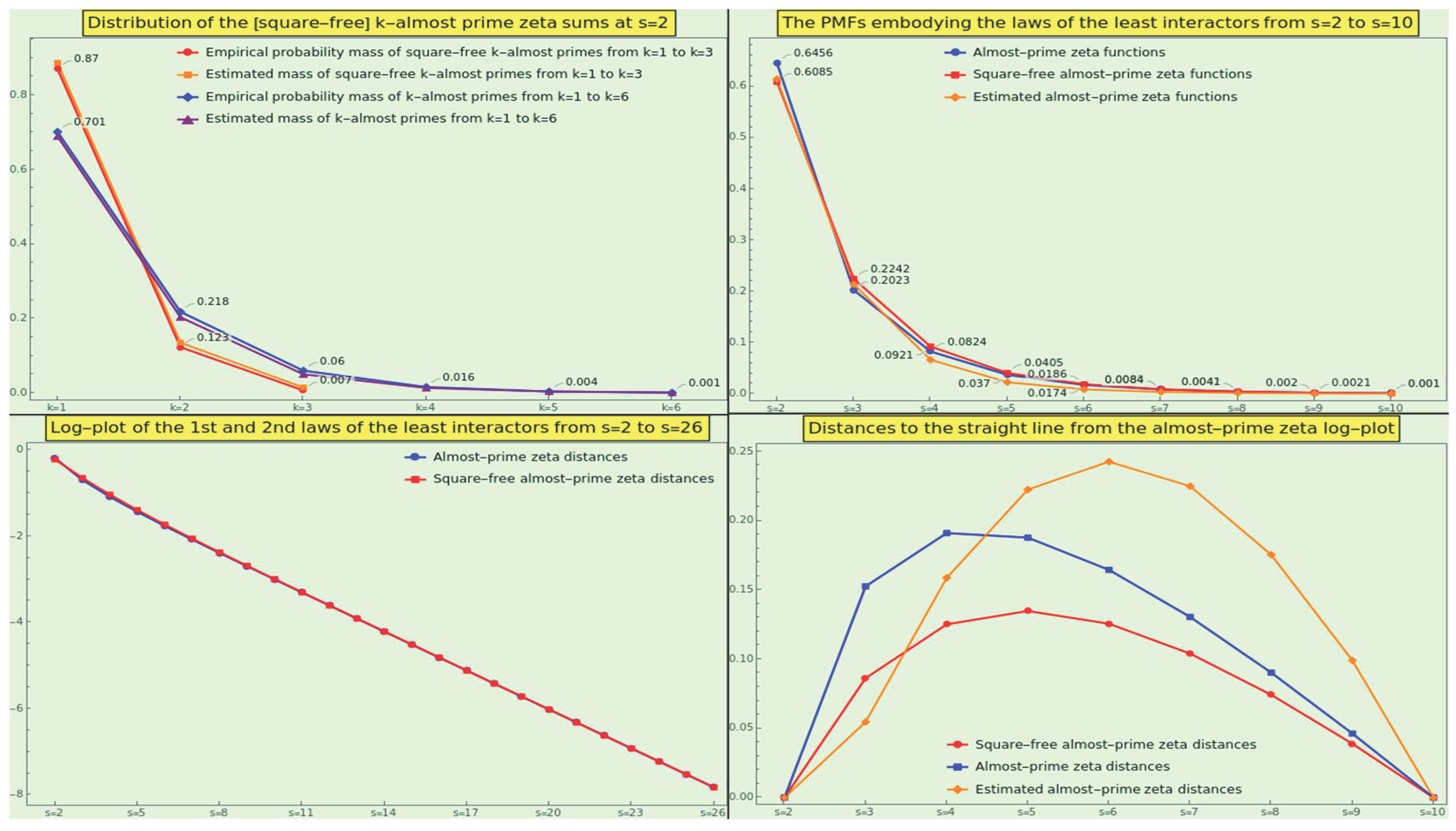

We illustrate the bias of the natural numbers towards the minor numbers. At the top-left, we show the PMFs of the empirical (in blue), the estimated (in purple) using a lognormal model with log-location 0.1 and log-scale 0.57, the empirical (in red), and the estimated (in orange) using a lognormal model centered at the origin and log-scale 0.45; the probability mass of the square-free almost-primes is negligible if . We show in the top-right corner the PMFs of the first (in blue) and second (in red) laws of interaction from s=2 (pairwise interaction) to s=10 (denary interaction). We also outline in orange (no labels) a lognormal model (log-location 0.135 and log-scale 0.635) that fits both empirical PMFs. We show in the bottom-left corner the log10-plots of the first (in blue) and second (in red) laws of interaction from s=2 to s=26, which practically coincide and exhibit a slight warping. In the bottom-right corner, we show the distance from the log10-plots to the straight line joining the log10-plot at s=2 and the log10-plot at s=10.

Figure 5.

We illustrate the bias of the natural numbers towards the minor numbers. At the top-left, we show the PMFs of the empirical (in blue), the estimated (in purple) using a lognormal model with log-location 0.1 and log-scale 0.57, the empirical (in red), and the estimated (in orange) using a lognormal model centered at the origin and log-scale 0.45; the probability mass of the square-free almost-primes is negligible if . We show in the top-right corner the PMFs of the first (in blue) and second (in red) laws of interaction from s=2 (pairwise interaction) to s=10 (denary interaction). We also outline in orange (no labels) a lognormal model (log-location 0.135 and log-scale 0.635) that fits both empirical PMFs. We show in the bottom-left corner the log10-plots of the first (in blue) and second (in red) laws of interaction from s=2 to s=26, which practically coincide and exhibit a slight warping. In the bottom-right corner, we show the distance from the log10-plots to the straight line joining the log10-plot at s=2 and the log10-plot at s=10.

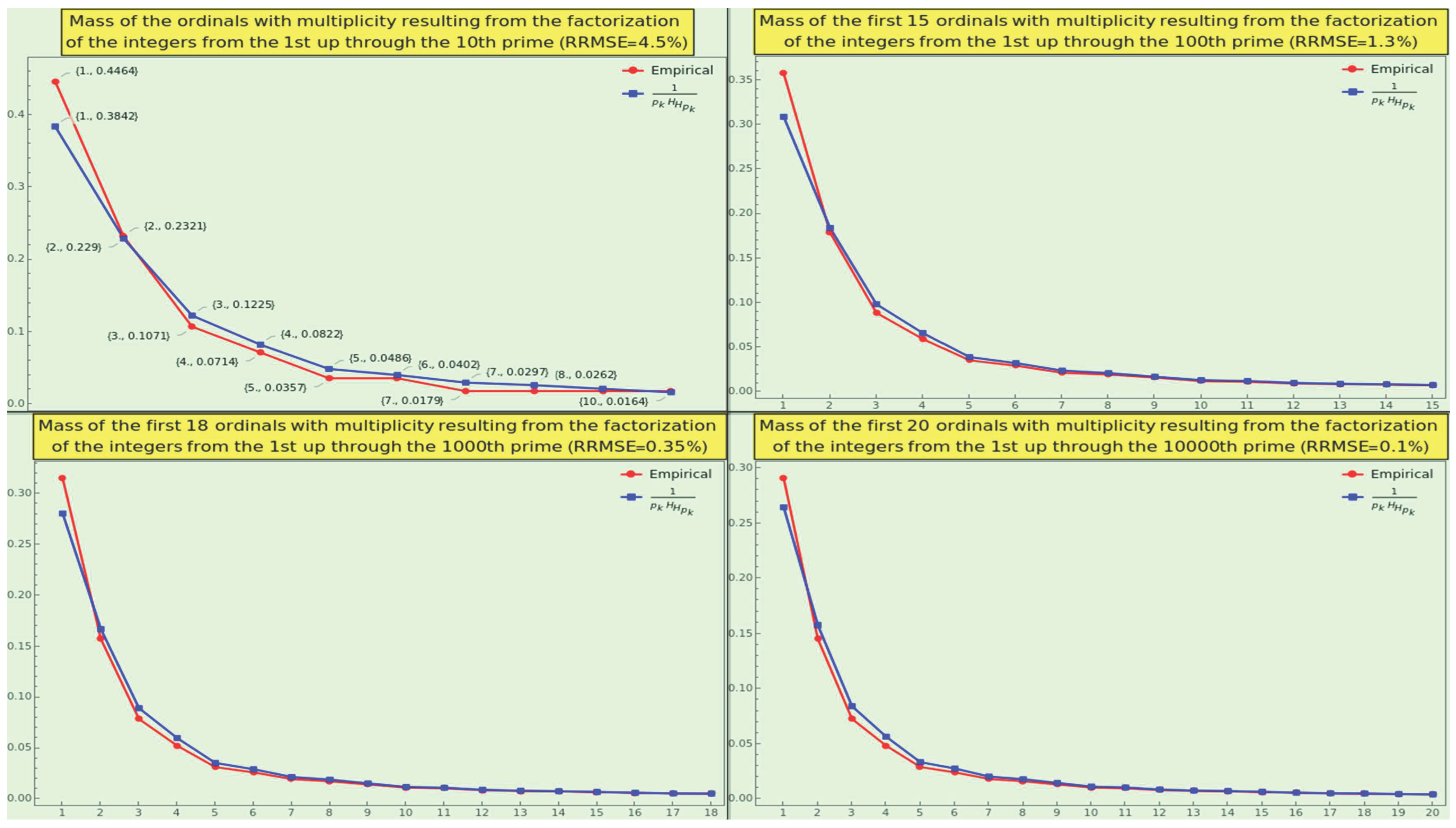

Figure 6.

Plot of the probability mass of the prime divisors (with multiplicity) resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers from up through the Mth prime, where M=10 (top-left), M=100 (top-right), M=1000 (bottom-left), M=10000 (bottom-right). The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal k, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from law 9 decreases as M goes to infinity, as does the gap between the first two probability masses 0.06225, 0.04878, 0.0346, and 0.02616, respectively.

Figure 6.

Plot of the probability mass of the prime divisors (with multiplicity) resulting from the factorization of the natural numbers from up through the Mth prime, where M=10 (top-left), M=100 (top-right), M=1000 (bottom-left), M=10000 (bottom-right). The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal k, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from law 9 decreases as M goes to infinity, as does the gap between the first two probability masses 0.06225, 0.04878, 0.0346, and 0.02616, respectively.

Figure 7.

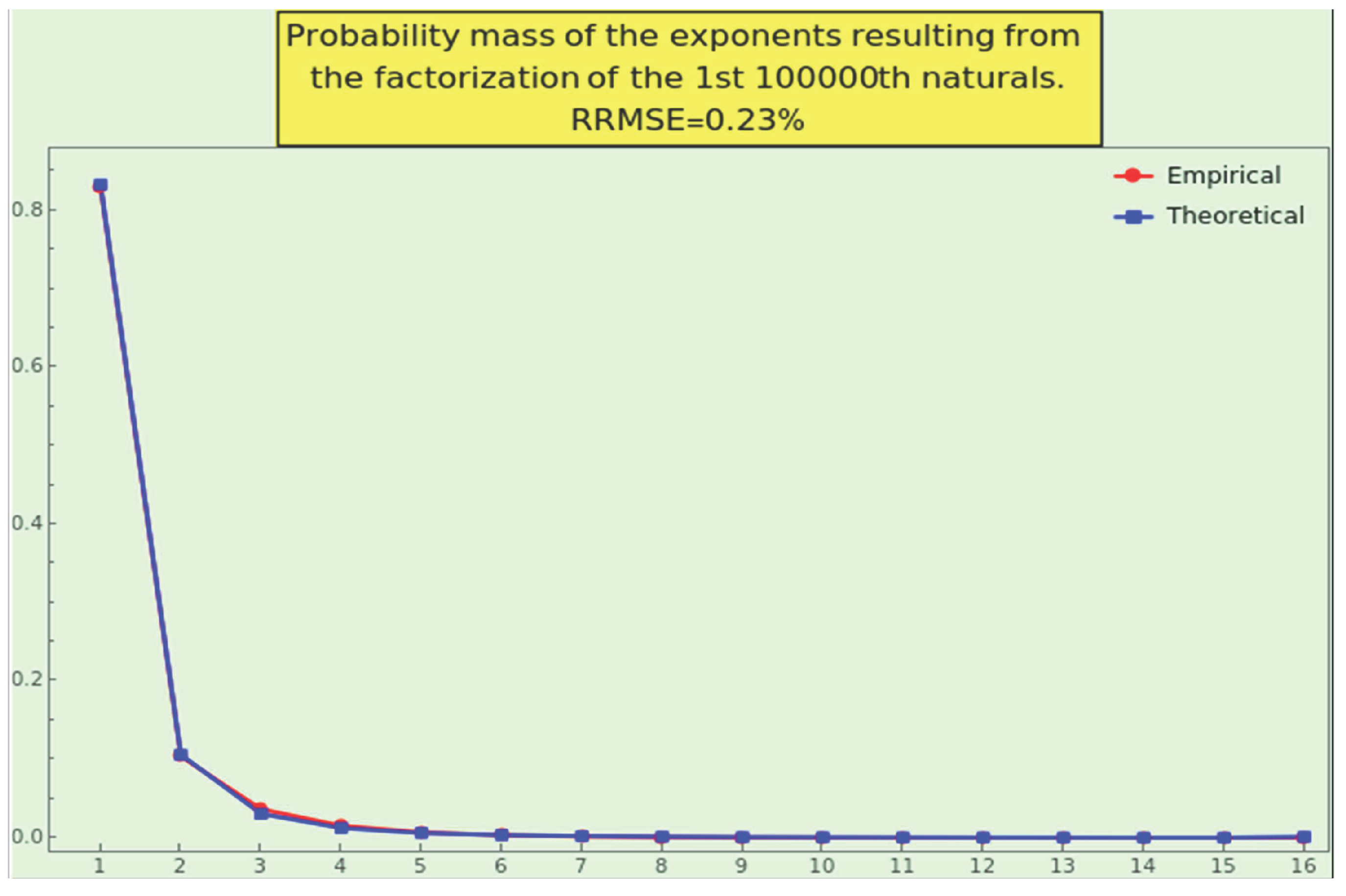

The factorization of the first th naturals reaches the multiplicity 16. The empirical (in red) and theoretical (law 12, in blue) distributions of multiplicities coincide; the RRMSE is 0.23%.

Figure 7.

The factorization of the first th naturals reaches the multiplicity 16. The empirical (in red) and theoretical (law 12, in blue) distributions of multiplicities coincide; the RRMSE is 0.23%.

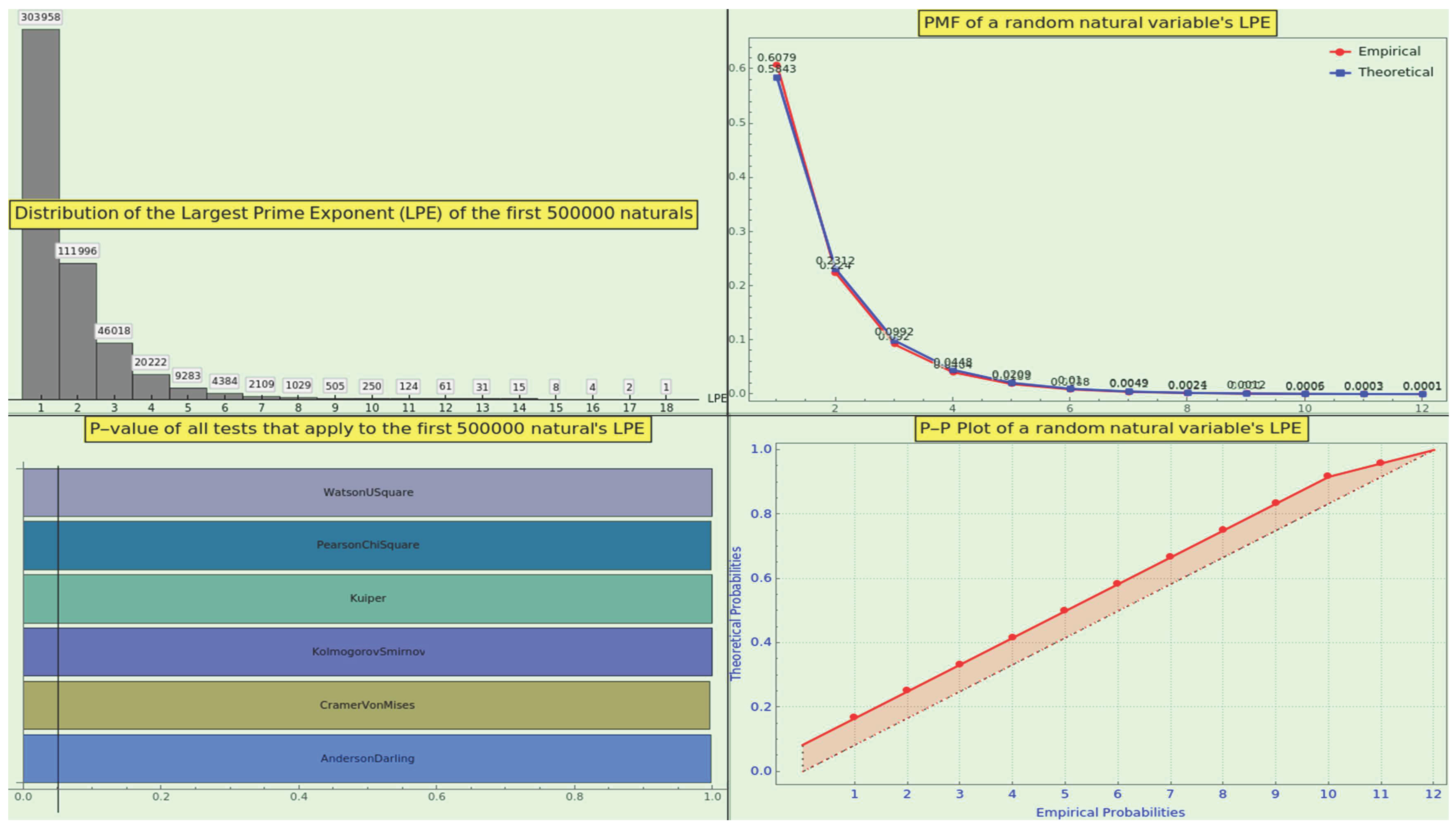

Figure 8.

The prime factorization of the first 500000 natural numbers reaches the multiplicity 18, as indicated by the histogram. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and theoretical in blue), the p-values of the statistical tests applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the empirical and theoretical PMFs of the LPE are hardly distinguishable.

Figure 8.

The prime factorization of the first 500000 natural numbers reaches the multiplicity 18, as indicated by the histogram. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and theoretical in blue), the p-values of the statistical tests applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the empirical and theoretical PMFs of the LPE are hardly distinguishable.

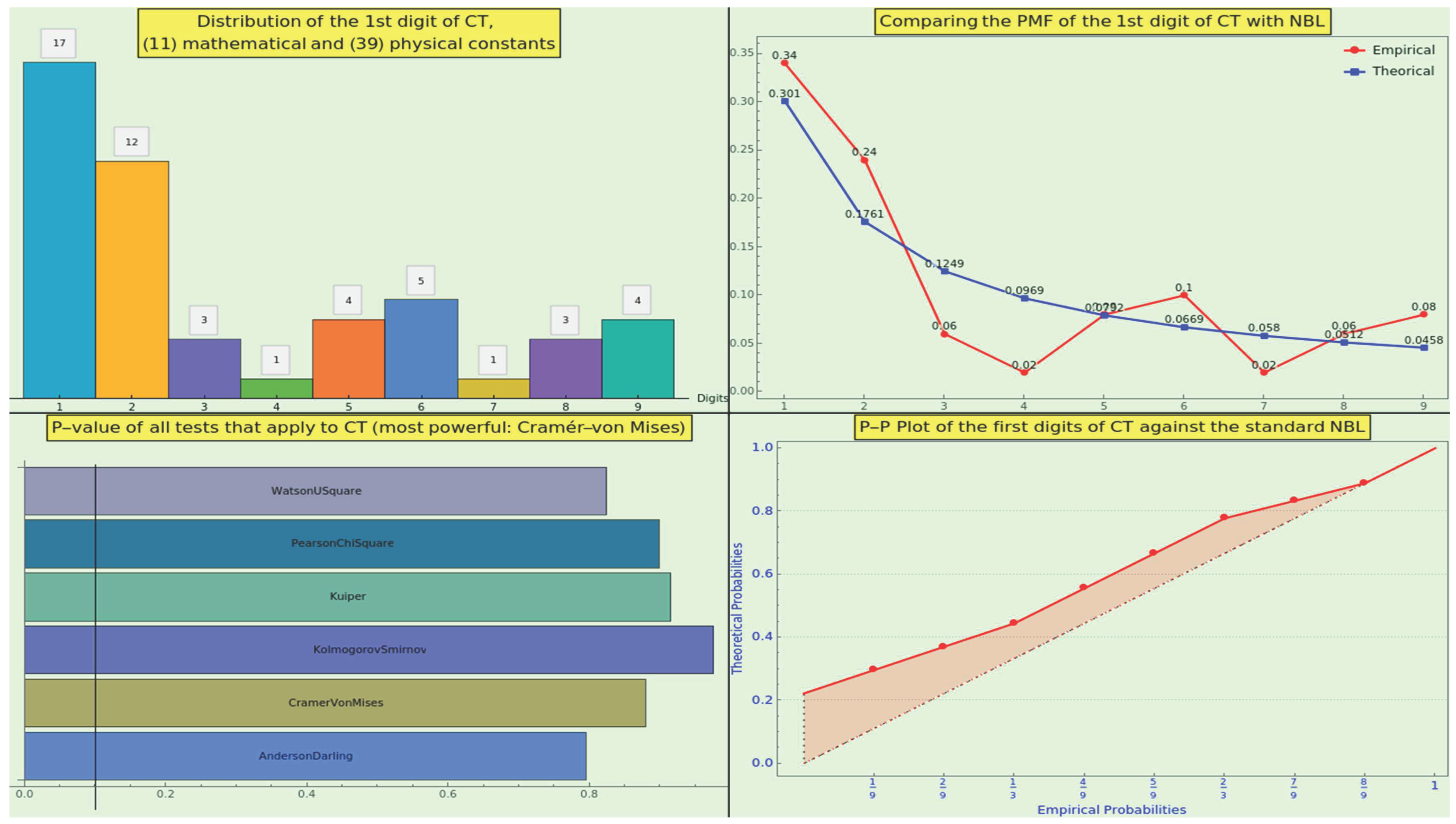

Figure 9.

CT plausibly complies with NBL.

Figure 9.

CT plausibly complies with NBL.

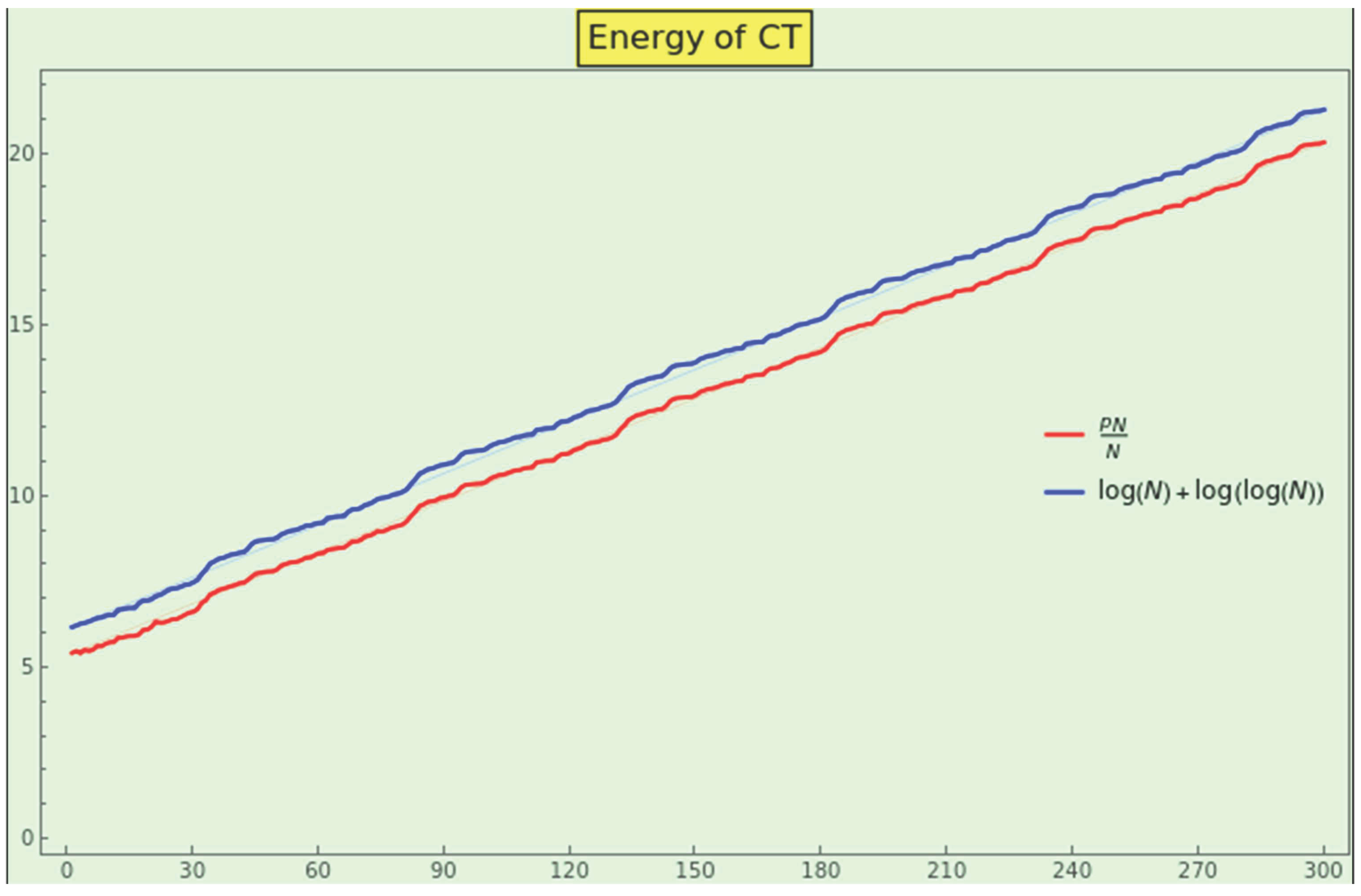

Figure 10.

We show the energy of the CT numerals and their upper limit.

Figure 10.

We show the energy of the CT numerals and their upper limit.

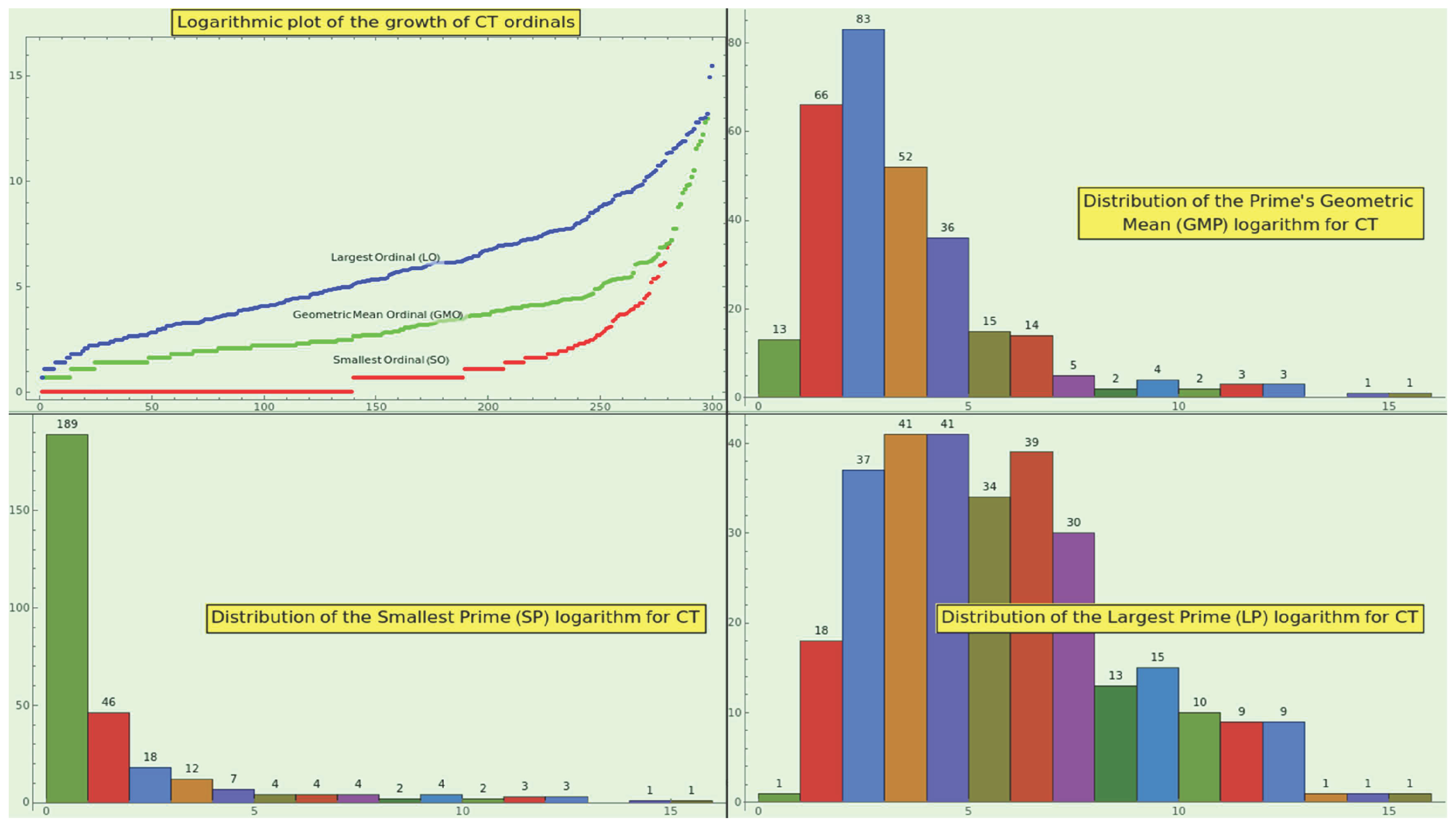

Figure 11.

Logarithmic plot of the CT ordinals (top-left) and histograms of the distribution of the SPO’s logarithm (bottom-left), prime geometric mean ordinal’s logarithm (top-right), and LPO’s logarithm (bottom-right).

Figure 11.

Logarithmic plot of the CT ordinals (top-left) and histograms of the distribution of the SPO’s logarithm (bottom-left), prime geometric mean ordinal’s logarithm (top-right), and LPO’s logarithm (bottom-right).

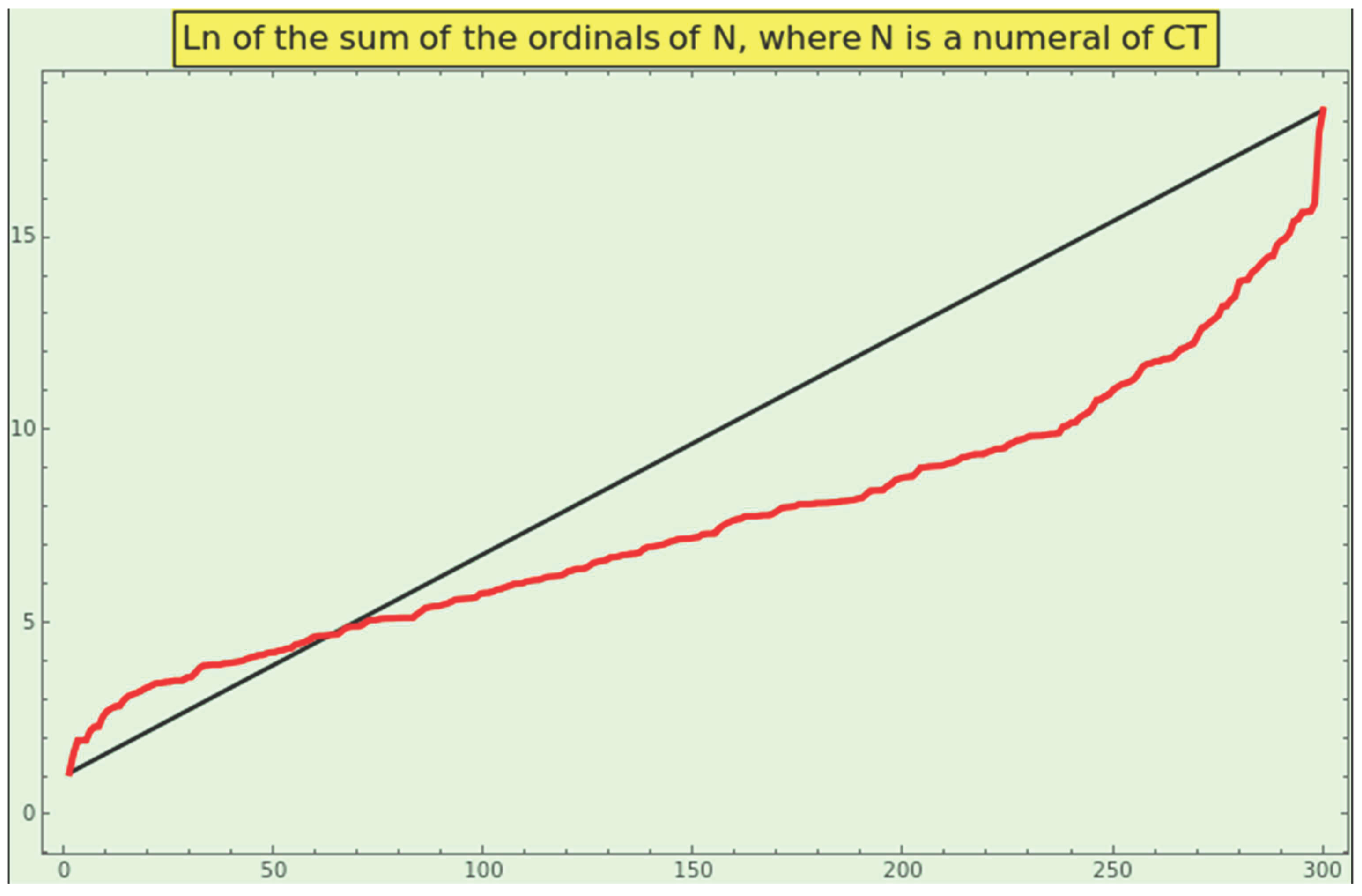

Figure 12.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every numeral in CT.

Figure 12.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every numeral in CT.

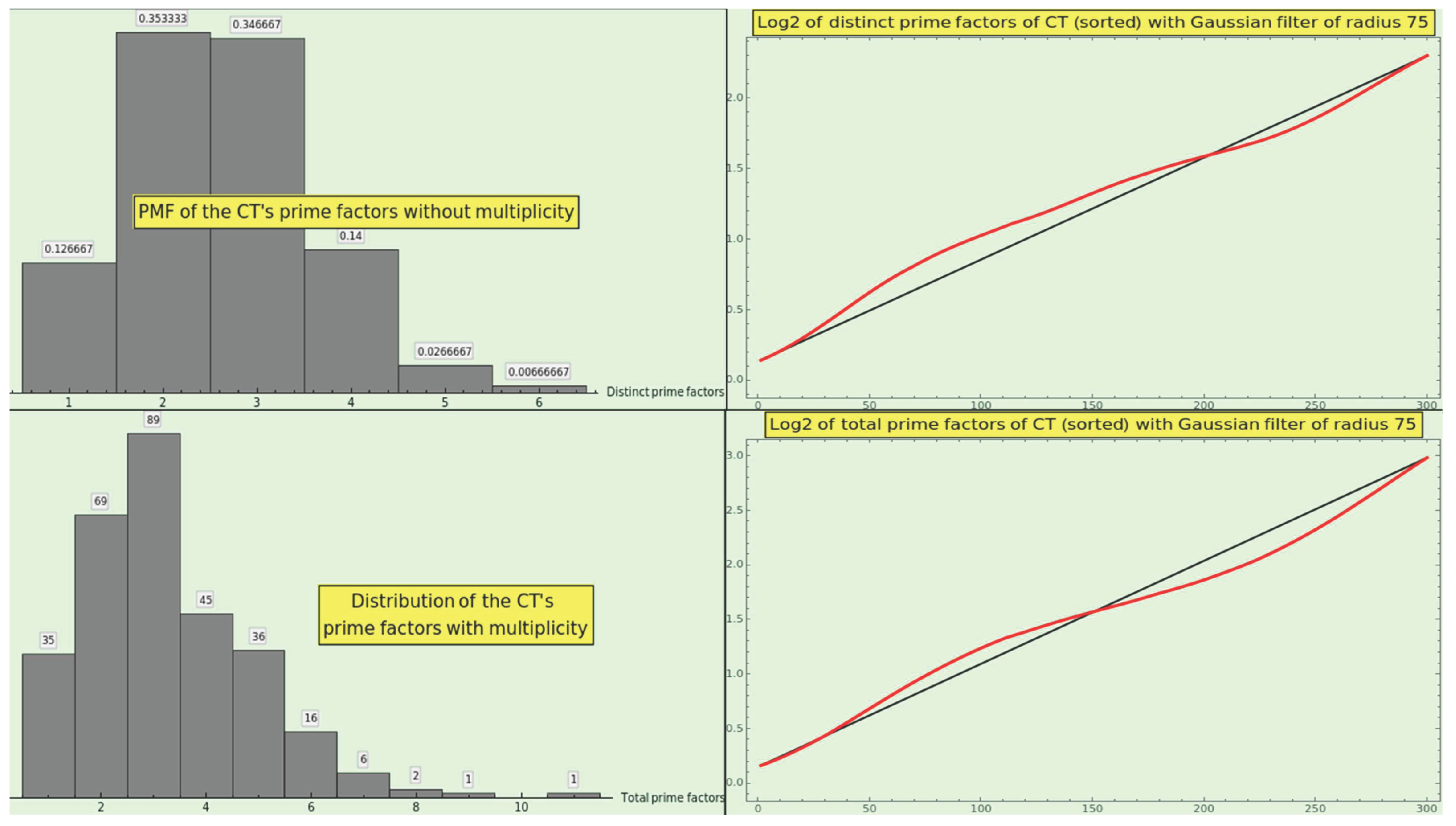

Figure 13.

Omega functions of CT.

Figure 13.

Omega functions of CT.

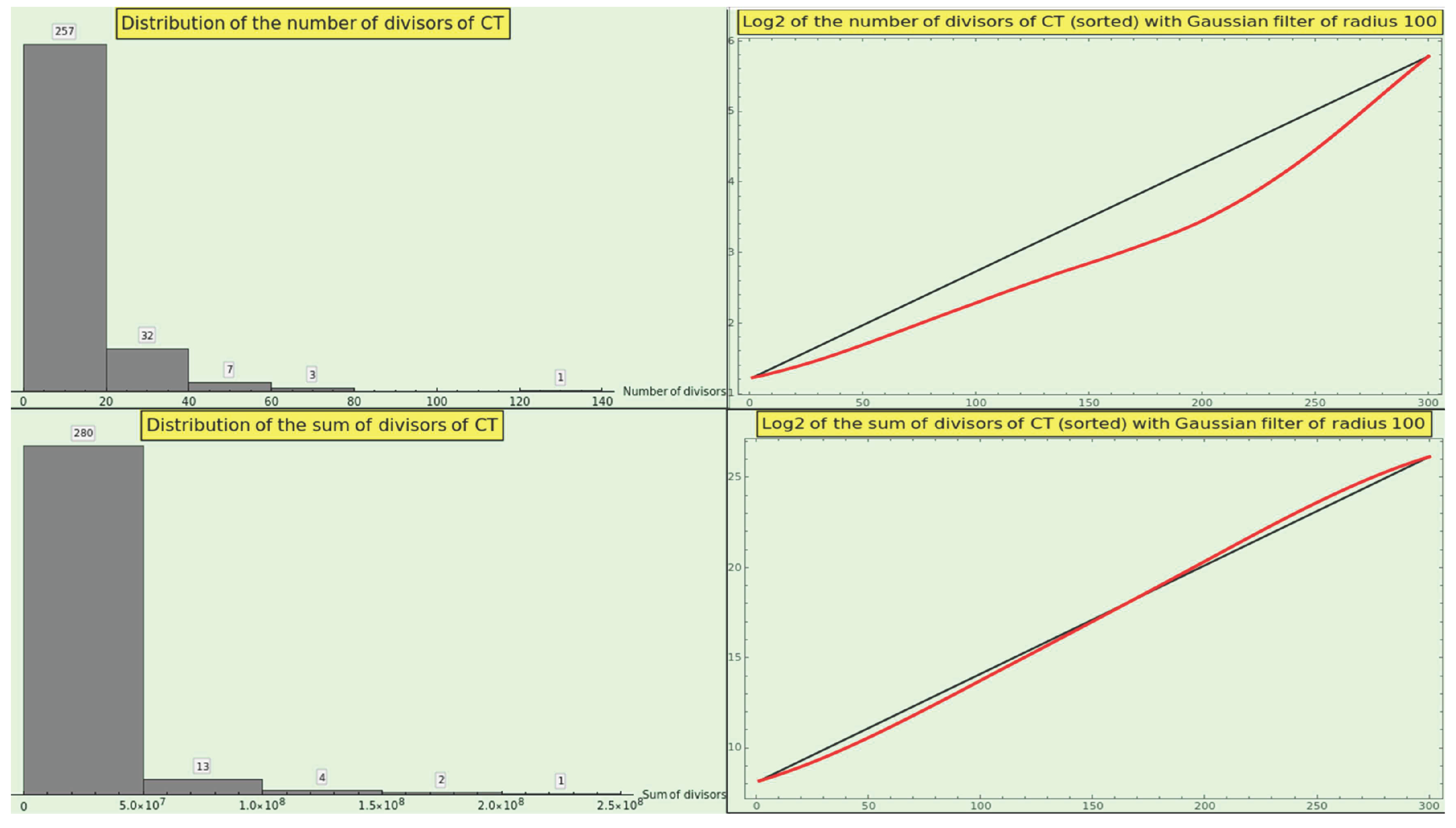

Figure 14.

Sigma functions of CT.

Figure 14.

Sigma functions of CT.

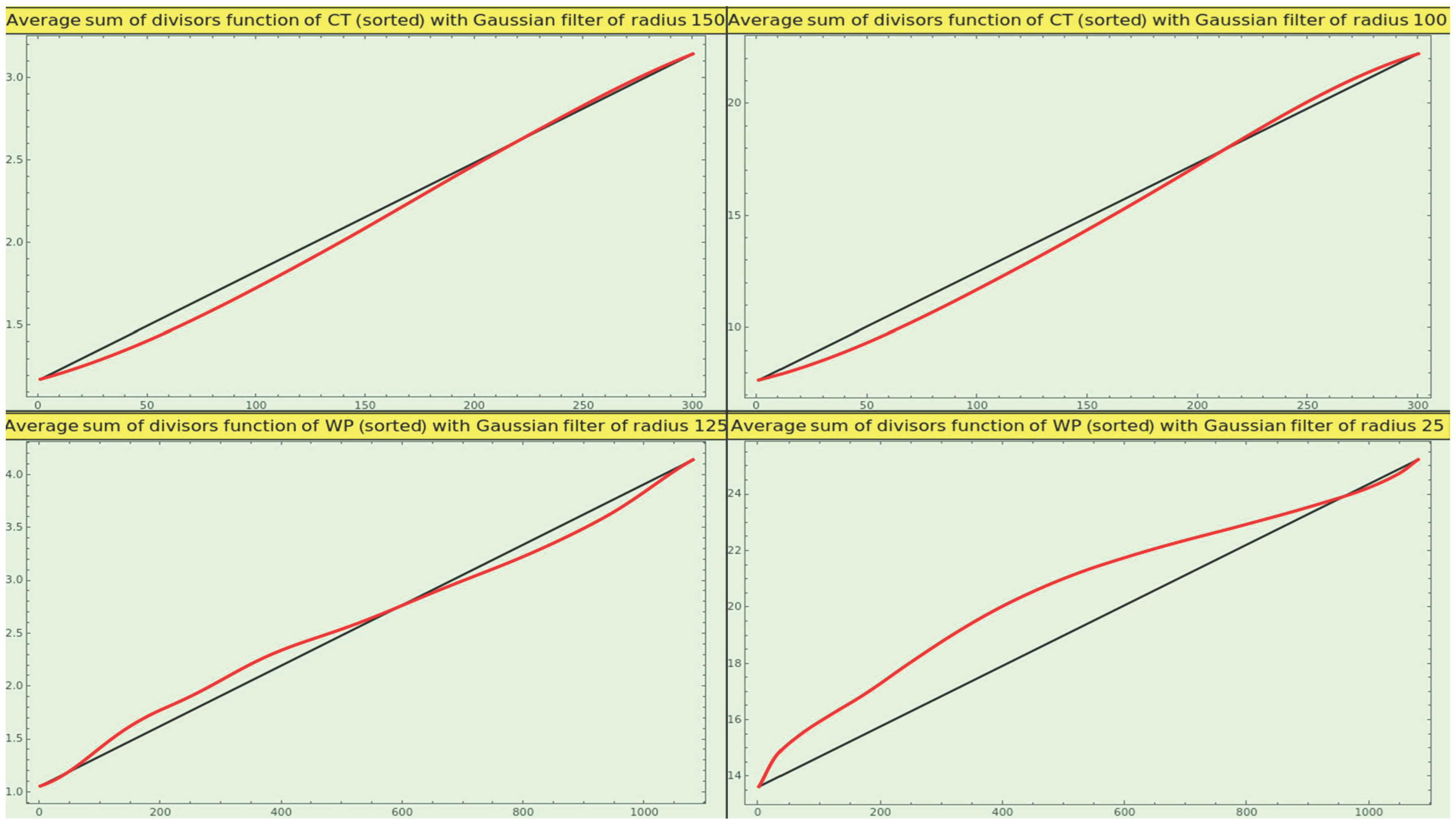

Figure 15.

Growth of the average sum of the number of divisors rendered by the CT and WP entries.

Figure 15.

Growth of the average sum of the number of divisors rendered by the CT and WP entries.

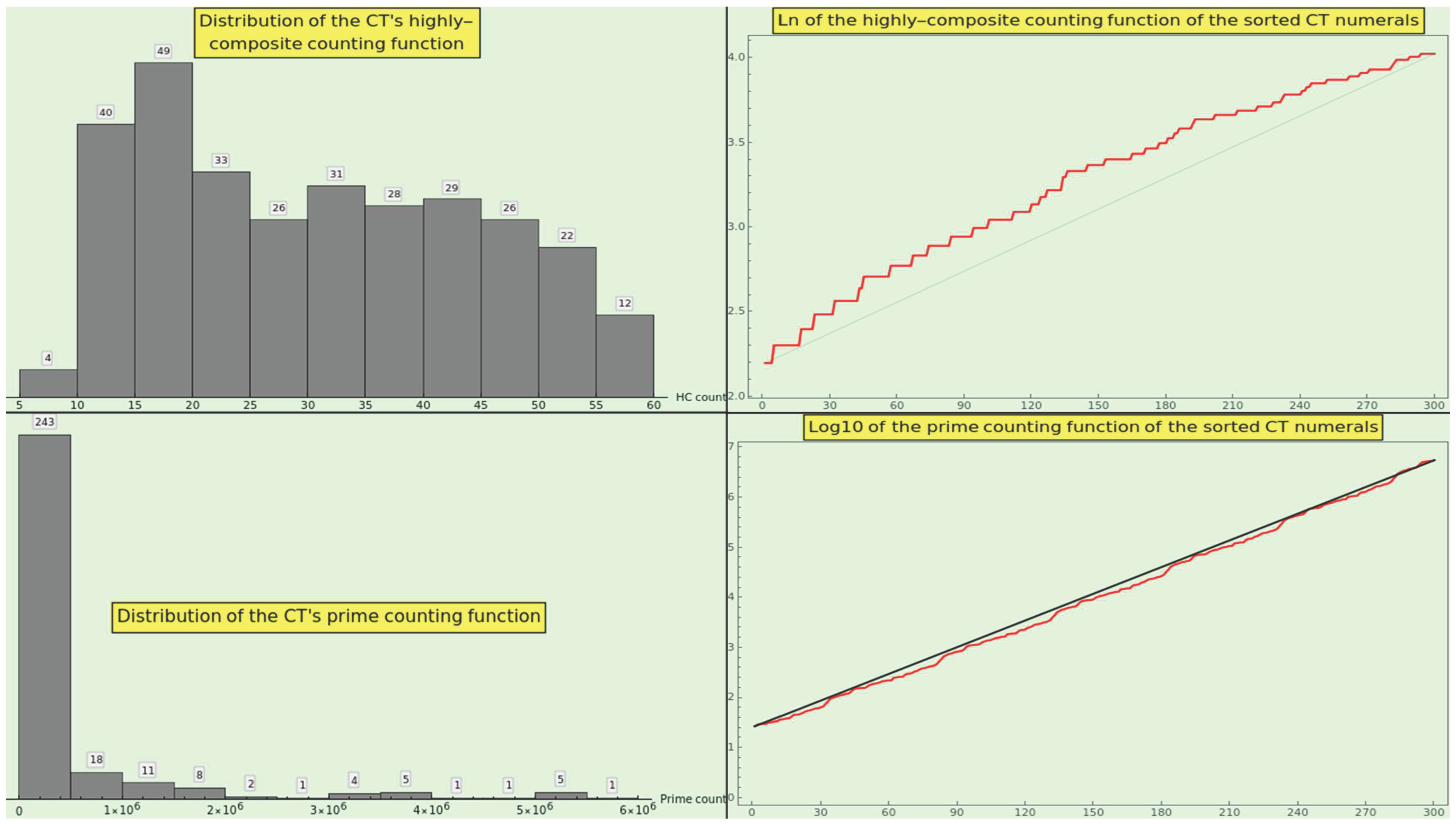

Figure 16.

Sort the numerals and calculate the natural logarithm of the highly composite counting function values to obtain the growth plot shown in the top-right corner. Now, calculate to obtain the growth plot shown in the bottom-right corner. We display the corresponding distributions on the left.

Figure 16.

Sort the numerals and calculate the natural logarithm of the highly composite counting function values to obtain the growth plot shown in the top-right corner. Now, calculate to obtain the growth plot shown in the bottom-right corner. We display the corresponding distributions on the left.

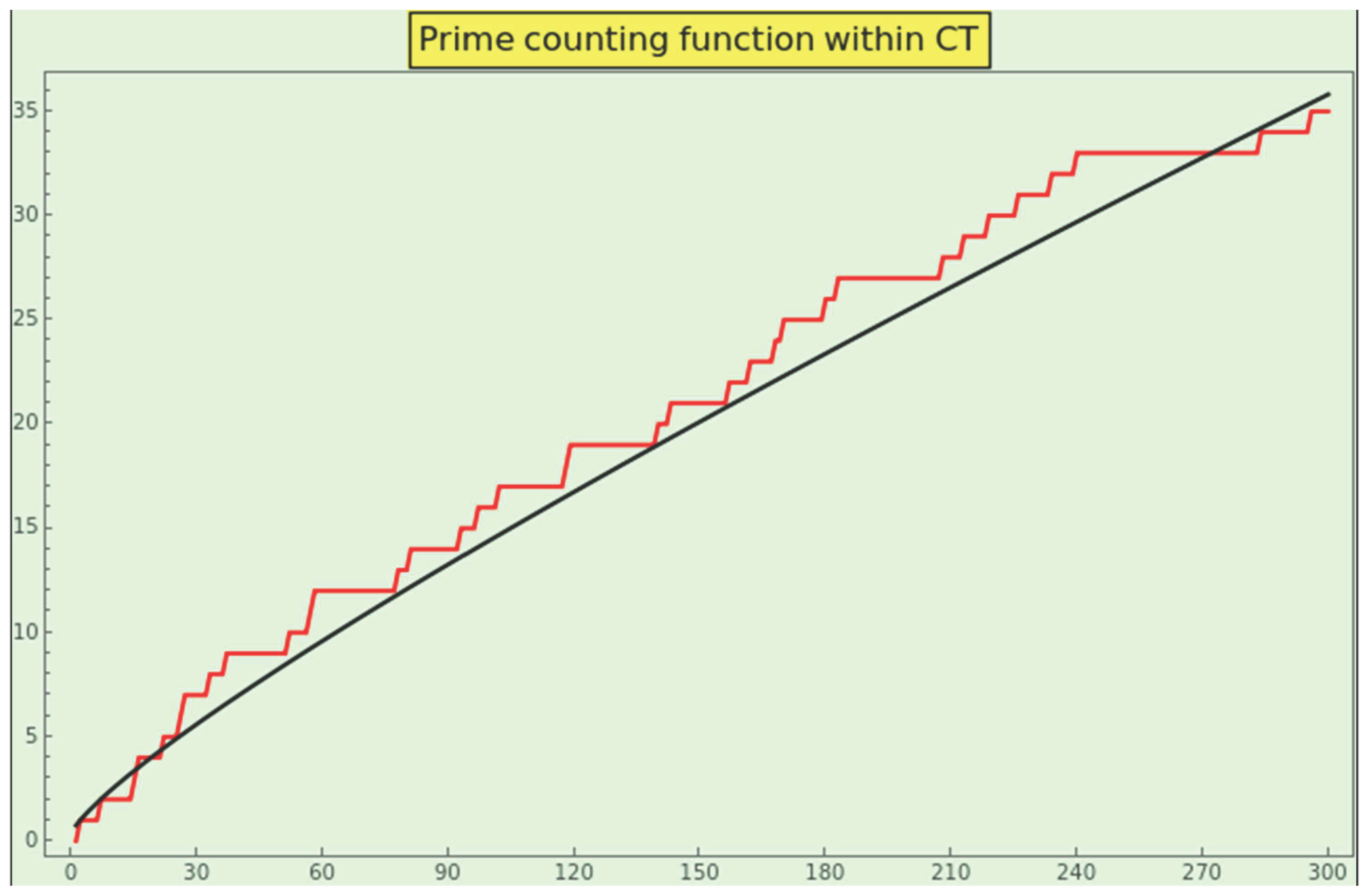

Figure 17.

Internal growth of the prime counting function of the numerals contained in CT, in red. We show the plot of the curve in black.

Figure 17.

Internal growth of the prime counting function of the numerals contained in CT, in red. We show the plot of the curve in black.

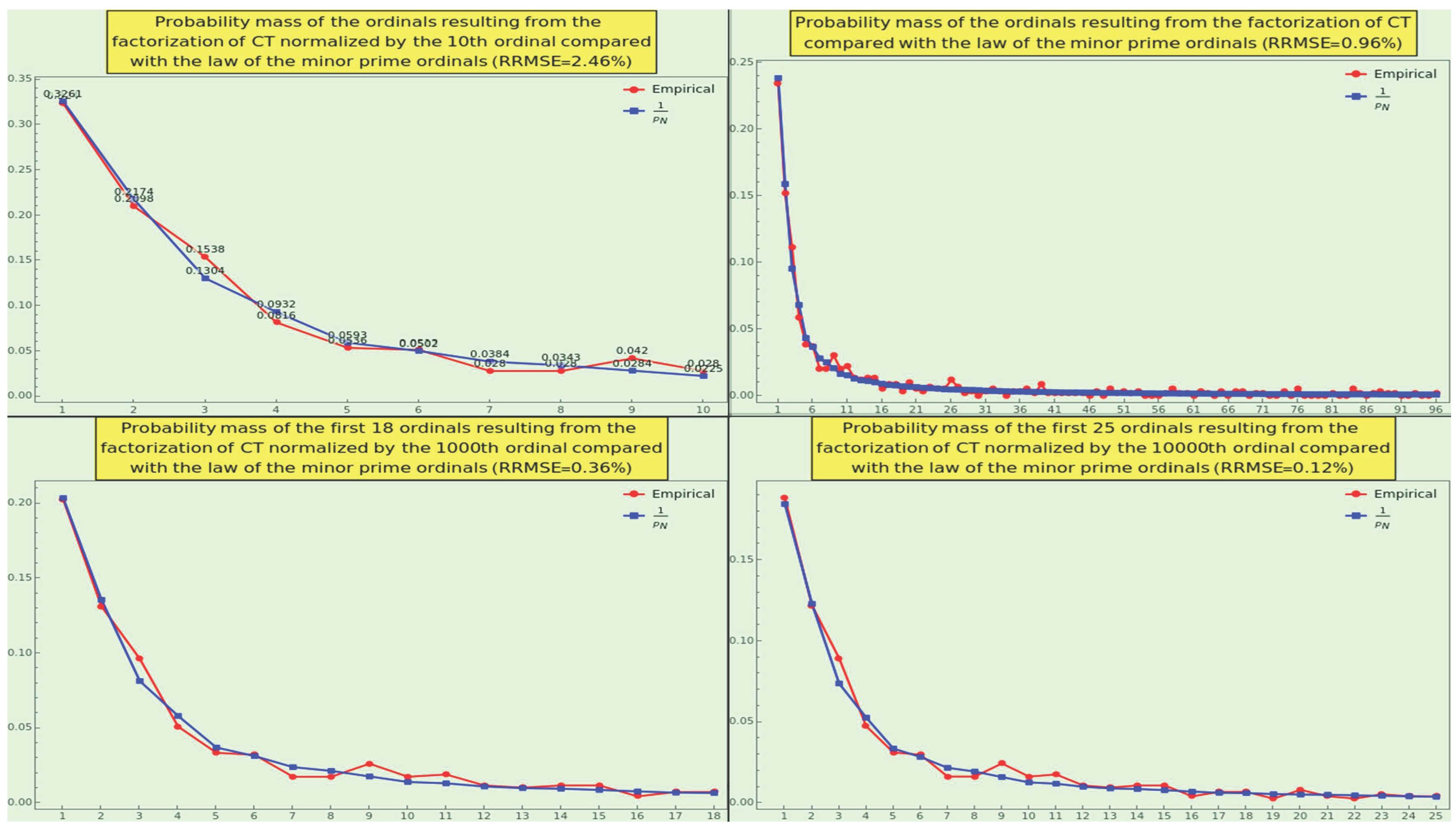

Figure 18.

Plot of all of the probability mass of the first ordinals of the factorization of CT normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime 3. We display the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency..

Figure 18.

Plot of all of the probability mass of the first ordinals of the factorization of CT normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime 3. We display the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency..

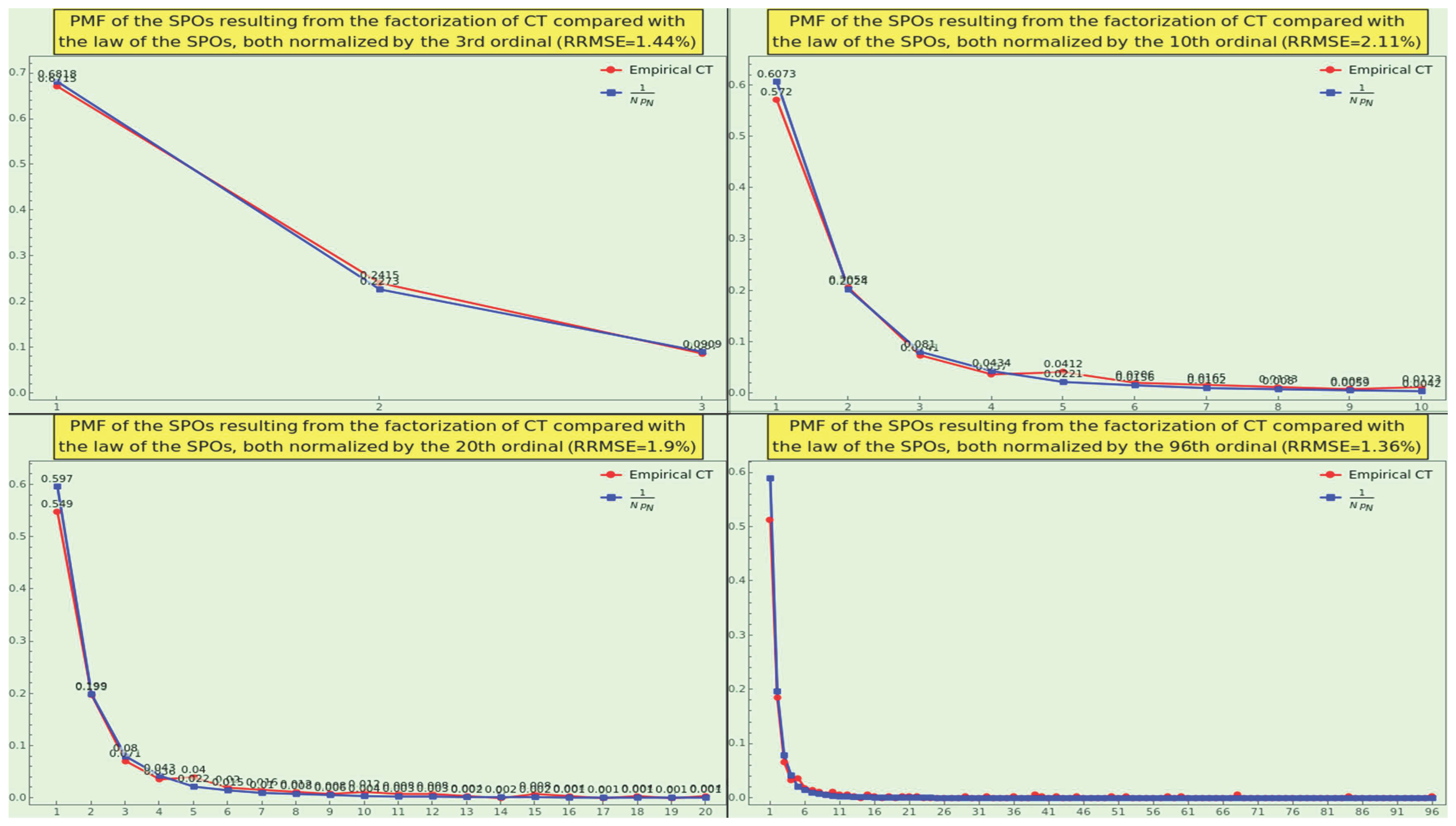

Figure 19.

Plot of the probability masses of the first SPOs of CT, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law 5. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 19.

Plot of the probability masses of the first SPOs of CT, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law 5. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 20.

The log-plot of the PMF sequences of , , , , , and are (-0.19,-0.694,-1.084,-1.432,-1.76,-2.078,-2.389,-2.697,-3.002), (-0.216,-0.649,-1.036,-1.393,-1.731,-2.057,-2.374,-2.686,-2.995), (-0.003,-2.171,-4.299,-6.405,-8.496,-10.576,-12.648,-14.714,-16.775), (-0.004,-2.017,-4.045,-6.078,-8.112,-10.148,-12.184,-14.219,-16.255), (0,-4.148,-8.198,-12.215,-16.221,-20.223,-24.224,-28.224,-32.223), and (0.,-3.959,-7.969,-11.99,-16.014,-20.037,-24.061,-28.086,-32.112), respectively. These are essentially the same curve (not a straight line), and hence constitute another sign of naturalness.

Figure 20.

The log-plot of the PMF sequences of , , , , , and are (-0.19,-0.694,-1.084,-1.432,-1.76,-2.078,-2.389,-2.697,-3.002), (-0.216,-0.649,-1.036,-1.393,-1.731,-2.057,-2.374,-2.686,-2.995), (-0.003,-2.171,-4.299,-6.405,-8.496,-10.576,-12.648,-14.714,-16.775), (-0.004,-2.017,-4.045,-6.078,-8.112,-10.148,-12.184,-14.219,-16.255), (0,-4.148,-8.198,-12.215,-16.221,-20.223,-24.224,-28.224,-32.223), and (0.,-3.959,-7.969,-11.99,-16.014,-20.037,-24.061,-28.086,-32.112), respectively. These are essentially the same curve (not a straight line), and hence constitute another sign of naturalness.

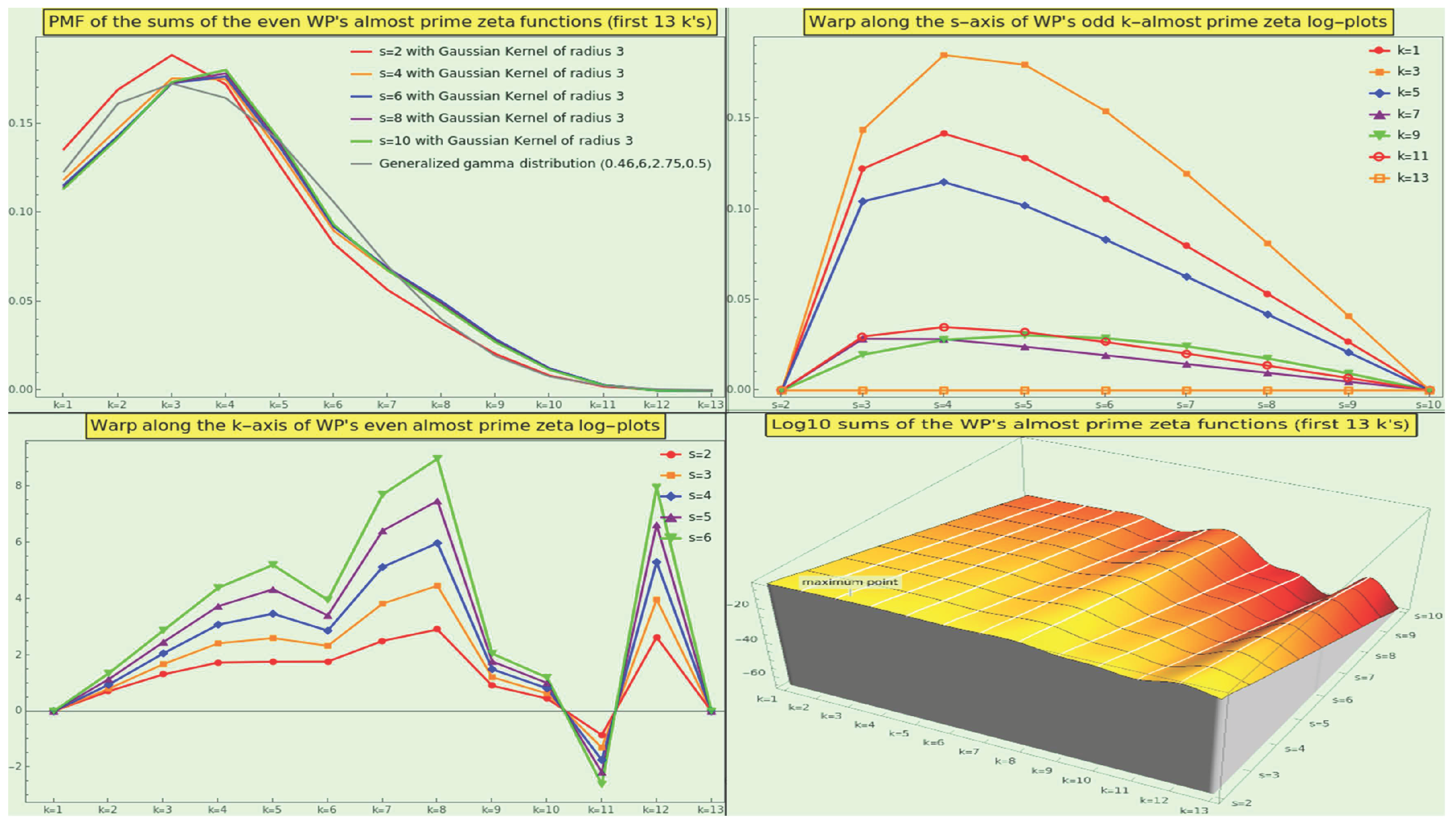

Figure 21.

At the top-left, we display the PMFs of CT, depending on k, for various values of s, after convolving the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=9) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to CT and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

Figure 21.

At the top-left, we display the PMFs of CT, depending on k, for various values of s, after convolving the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=9) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to CT and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

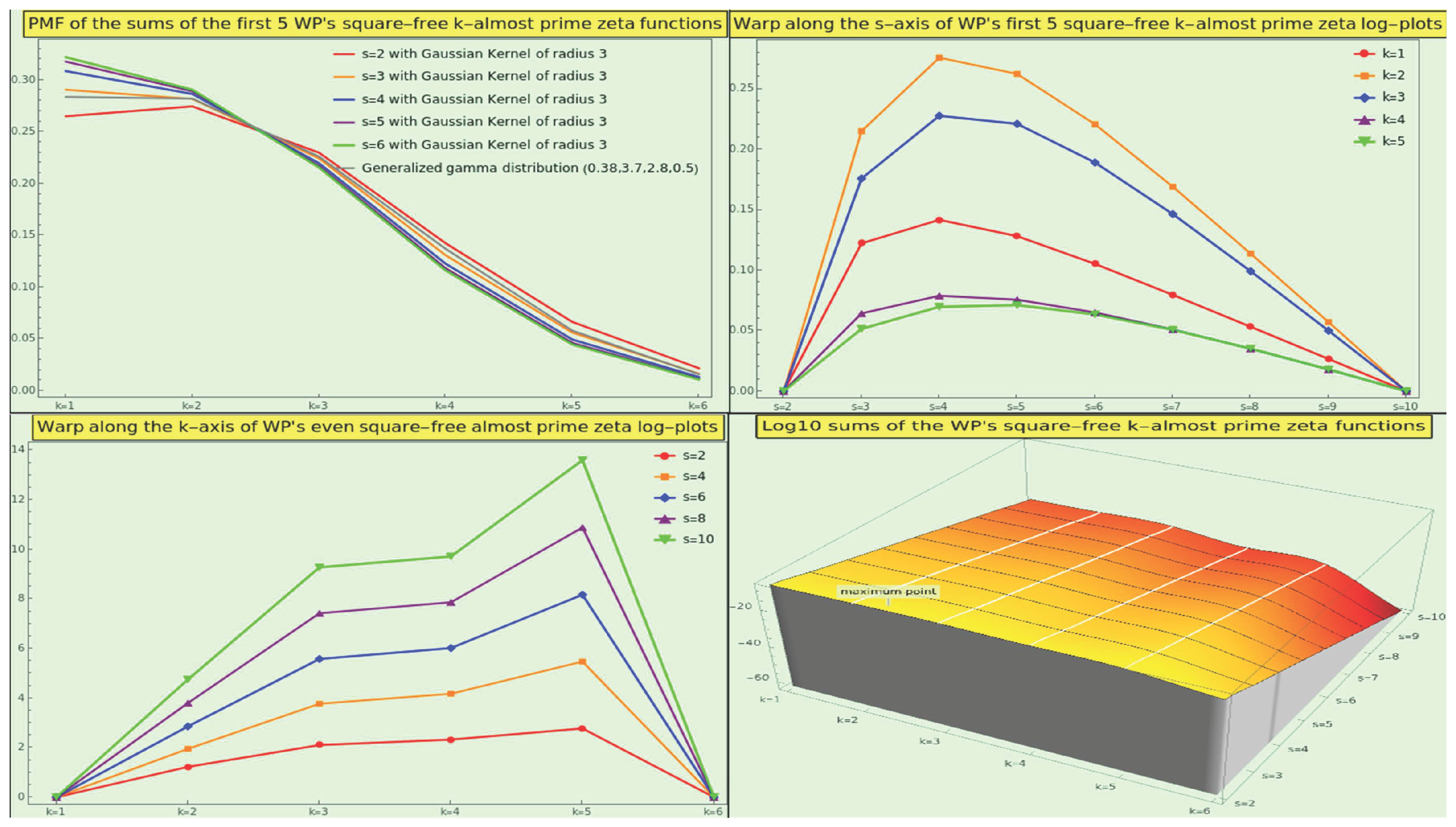

Figure 22.

At the top-left, we display the PMFs of CT, depending on k, for various values of s, after convolving the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these square-free almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=6) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to CT and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

Figure 22.

At the top-left, we display the PMFs of CT, depending on k, for various values of s, after convolving the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these square-free almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=6) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to CT and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

Figure 23.

Calculate for every and sort the resulting values; their plot shows linear growth of the CT totatives (top-left). Besides, we show the region of growth and plot of the intratotatives (top-right) and non-intratotatives (bottom-left), as well as the average growth of the intratotatives (bottom-right).

Figure 23.

Calculate for every and sort the resulting values; their plot shows linear growth of the CT totatives (top-left). Besides, we show the region of growth and plot of the intratotatives (top-right) and non-intratotatives (bottom-left), as well as the average growth of the intratotatives (bottom-right).

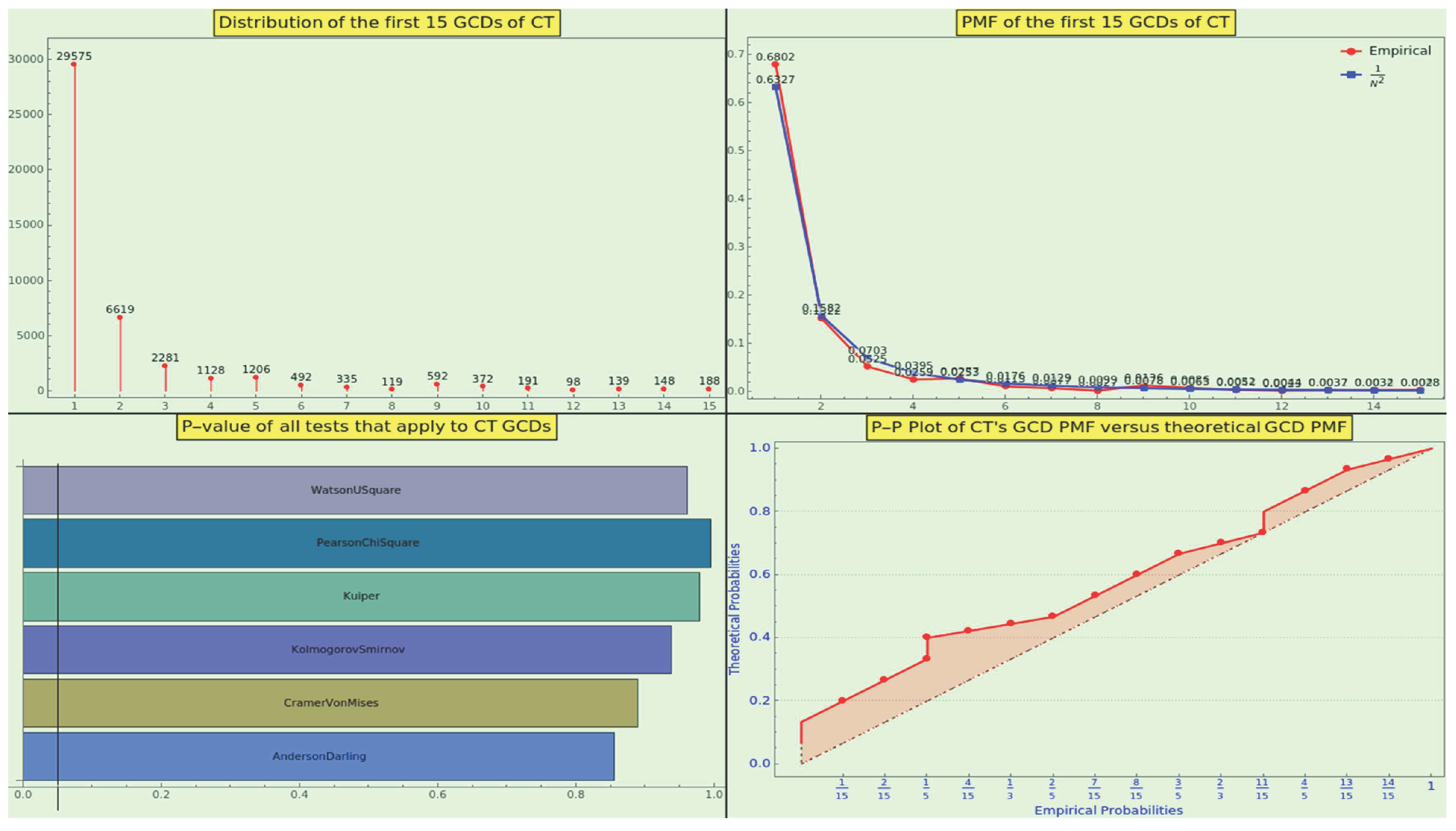

Figure 24.

The CT entries yield the histogram in the top-left corner of the figure regarding the pairwise GCD. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate that the GCD PMF of CT and the theoretical GCD PMF are hardly distinguishable.

Figure 24.

The CT entries yield the histogram in the top-left corner of the figure regarding the pairwise GCD. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate that the GCD PMF of CT and the theoretical GCD PMF are hardly distinguishable.

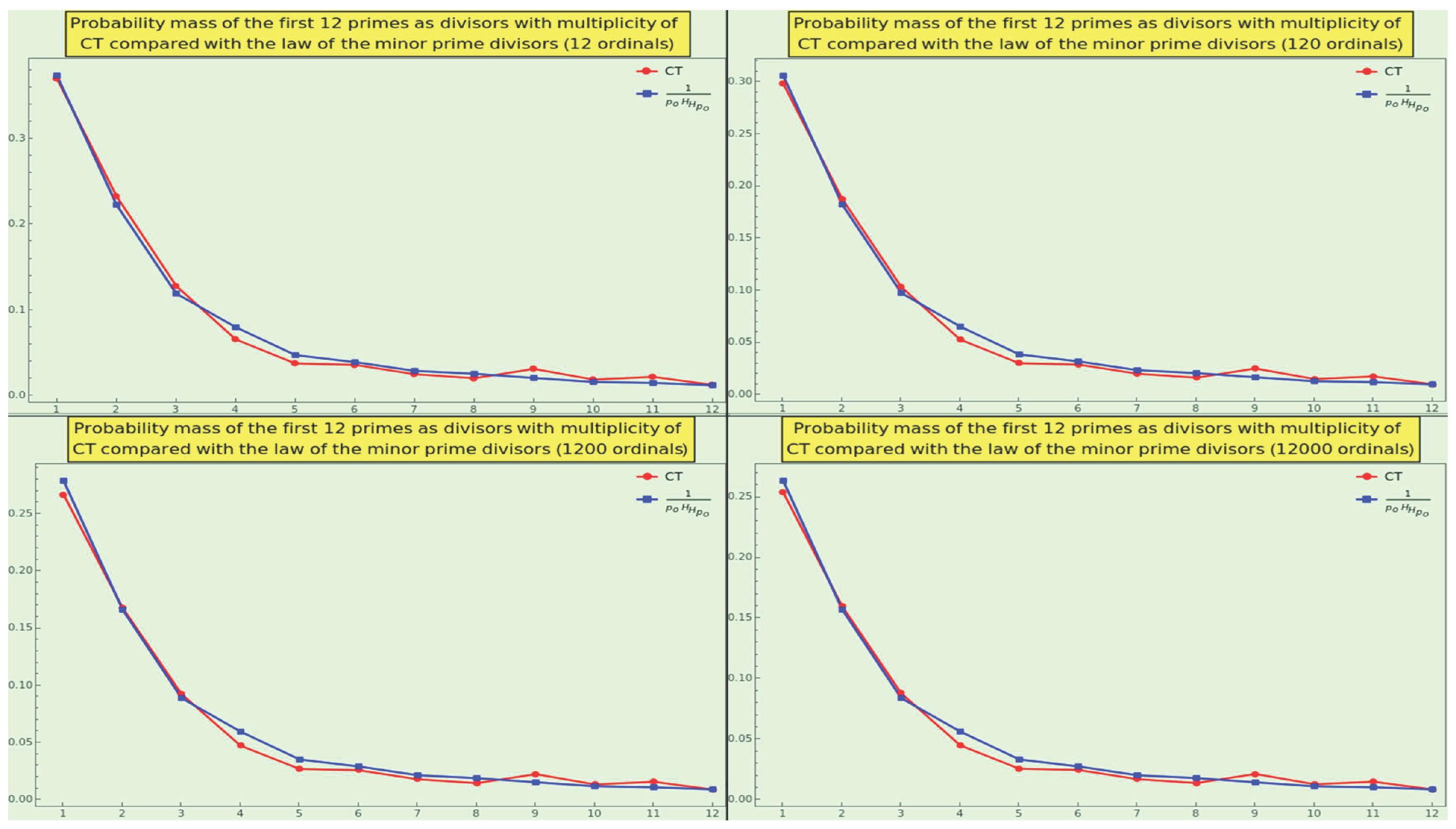

Figure 25.

Plot in red of the probability mass of the first 12 ordinals as divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of CT, compared with the plot in blue of the masses resulting from the law 9. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 25.

Plot in red of the probability mass of the first 12 ordinals as divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of CT, compared with the plot in blue of the masses resulting from the law 9. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

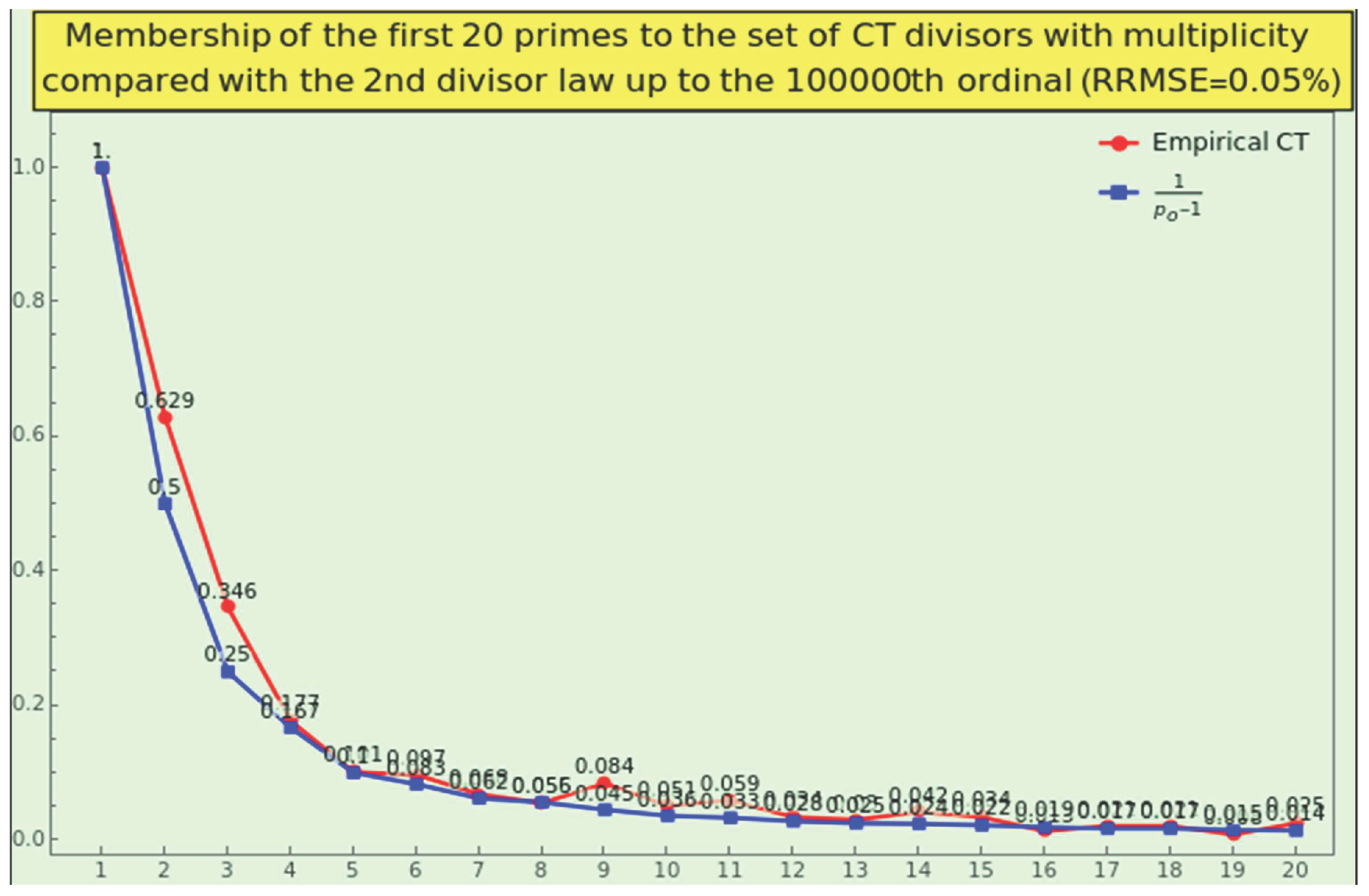

Figure 26.

Plot in red of the first 20 ordinal’s possibility masses of the prime divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of CT in comparison with the theoretical frequency relative to . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the law 10 (in blue) is excellent.

Figure 26.

Plot in red of the first 20 ordinal’s possibility masses of the prime divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of CT in comparison with the theoretical frequency relative to . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the law 10 (in blue) is excellent.

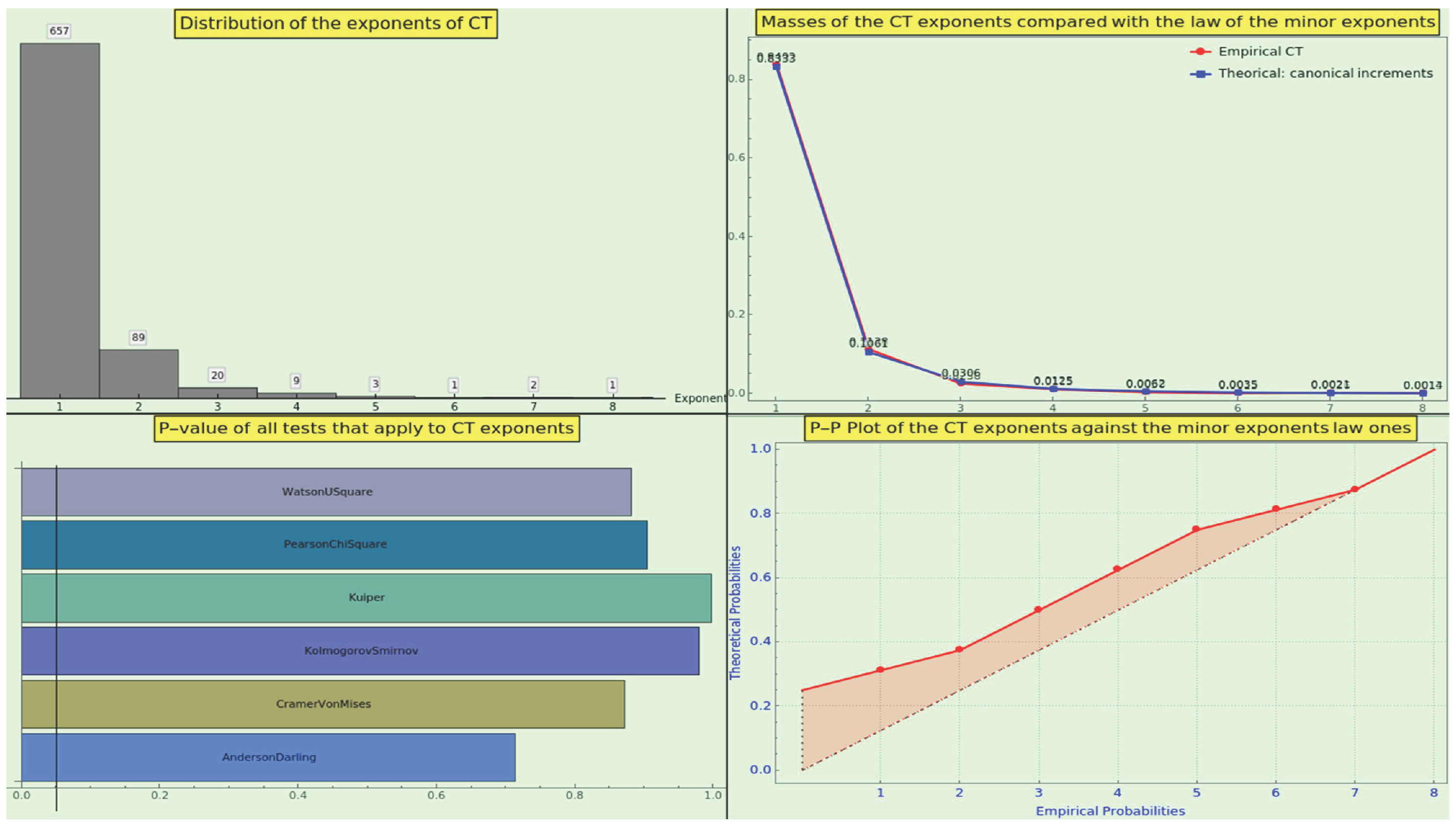

Figure 27.

The prime factorization of CT reaches the multiplicity 8, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the distributions of multiplicities are hardly distinguishable.

Figure 27.

The prime factorization of CT reaches the multiplicity 8, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the distributions of multiplicities are hardly distinguishable.

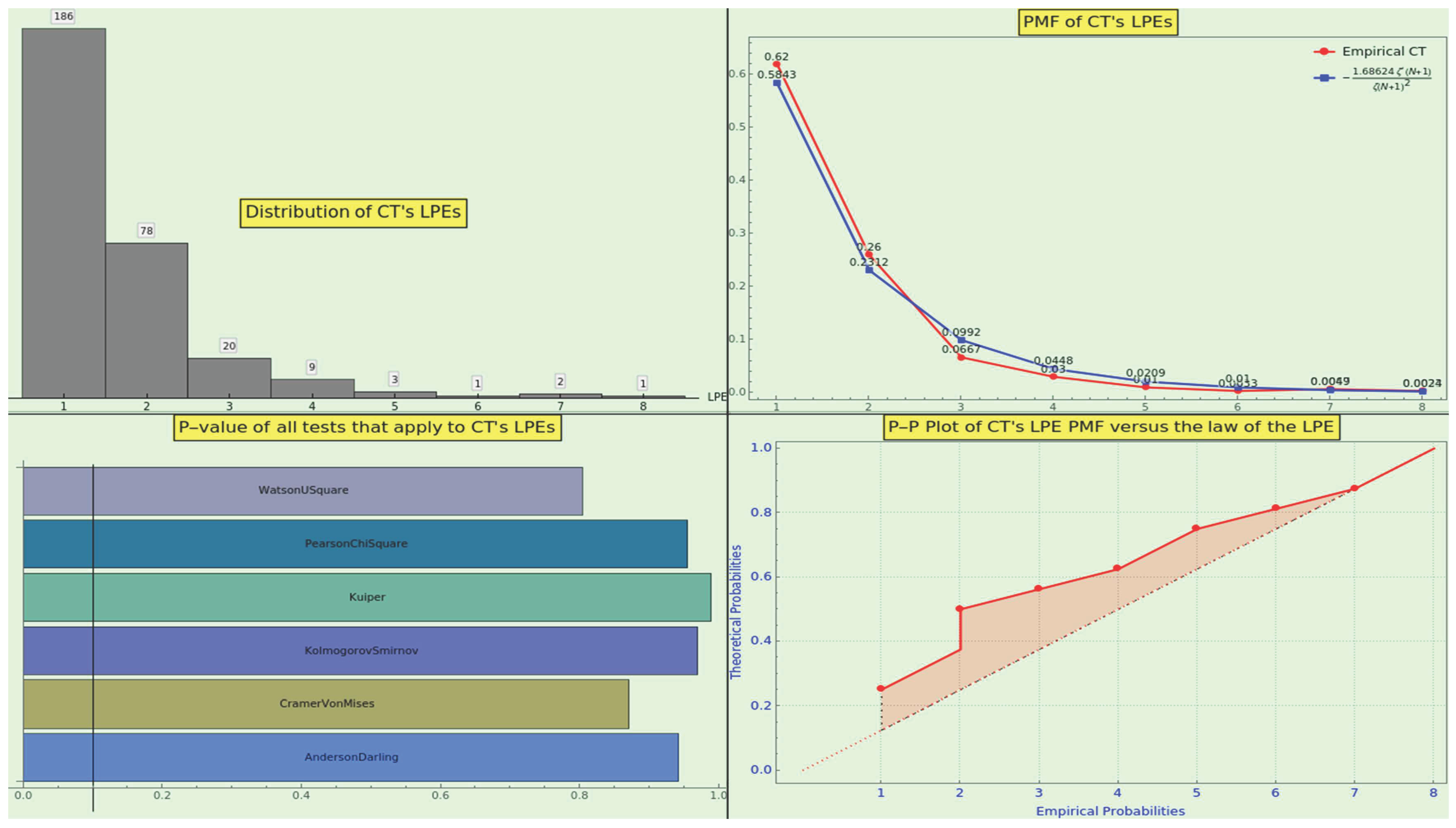

Figure 28.

The LPEs of CT reach the multiplicity 8, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot point to conformity.

Figure 28.

The LPEs of CT reach the multiplicity 8, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot point to conformity.

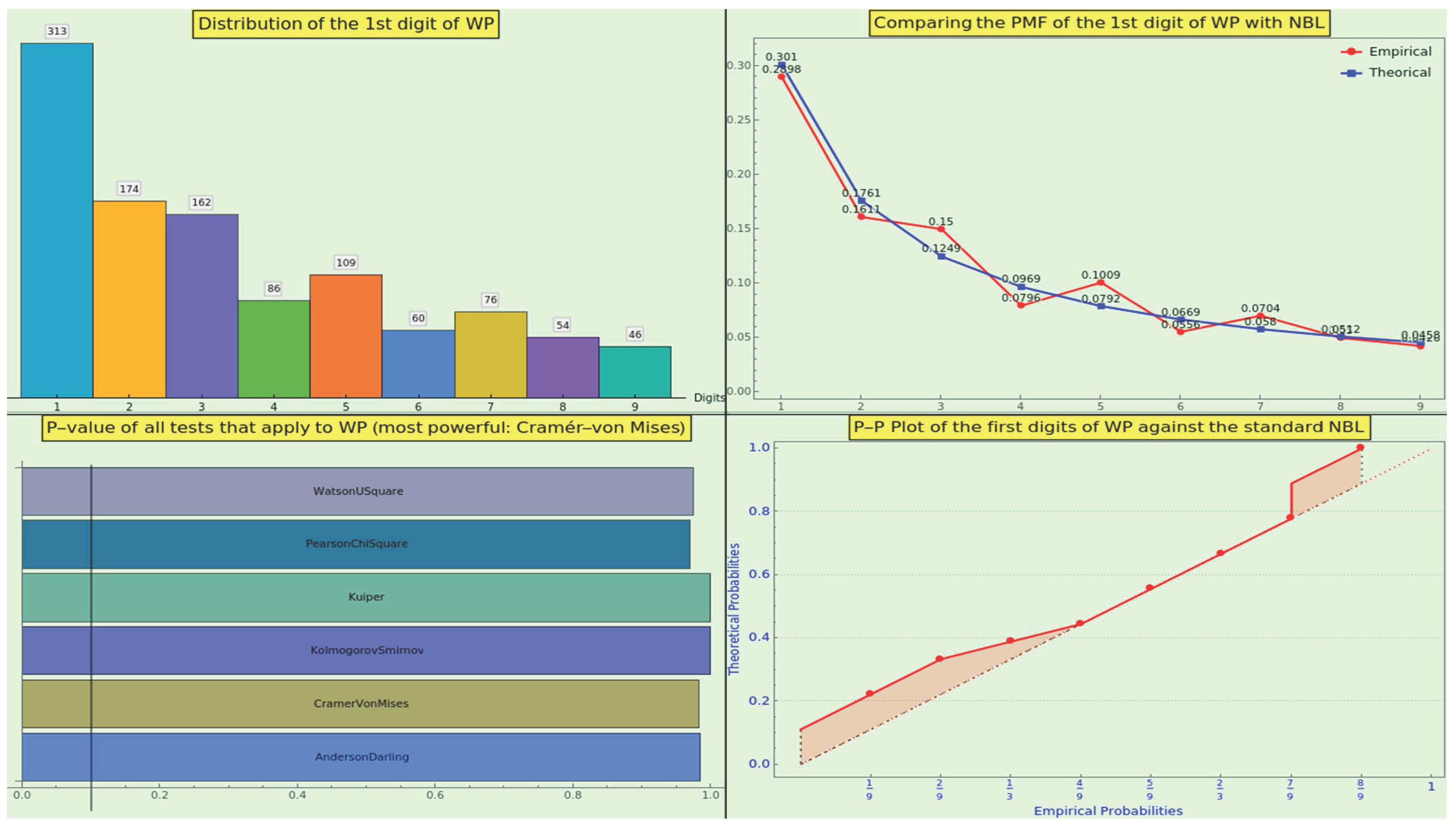

Figure 29.

WP plausibly obeys NBL.

Figure 29.

WP plausibly obeys NBL.

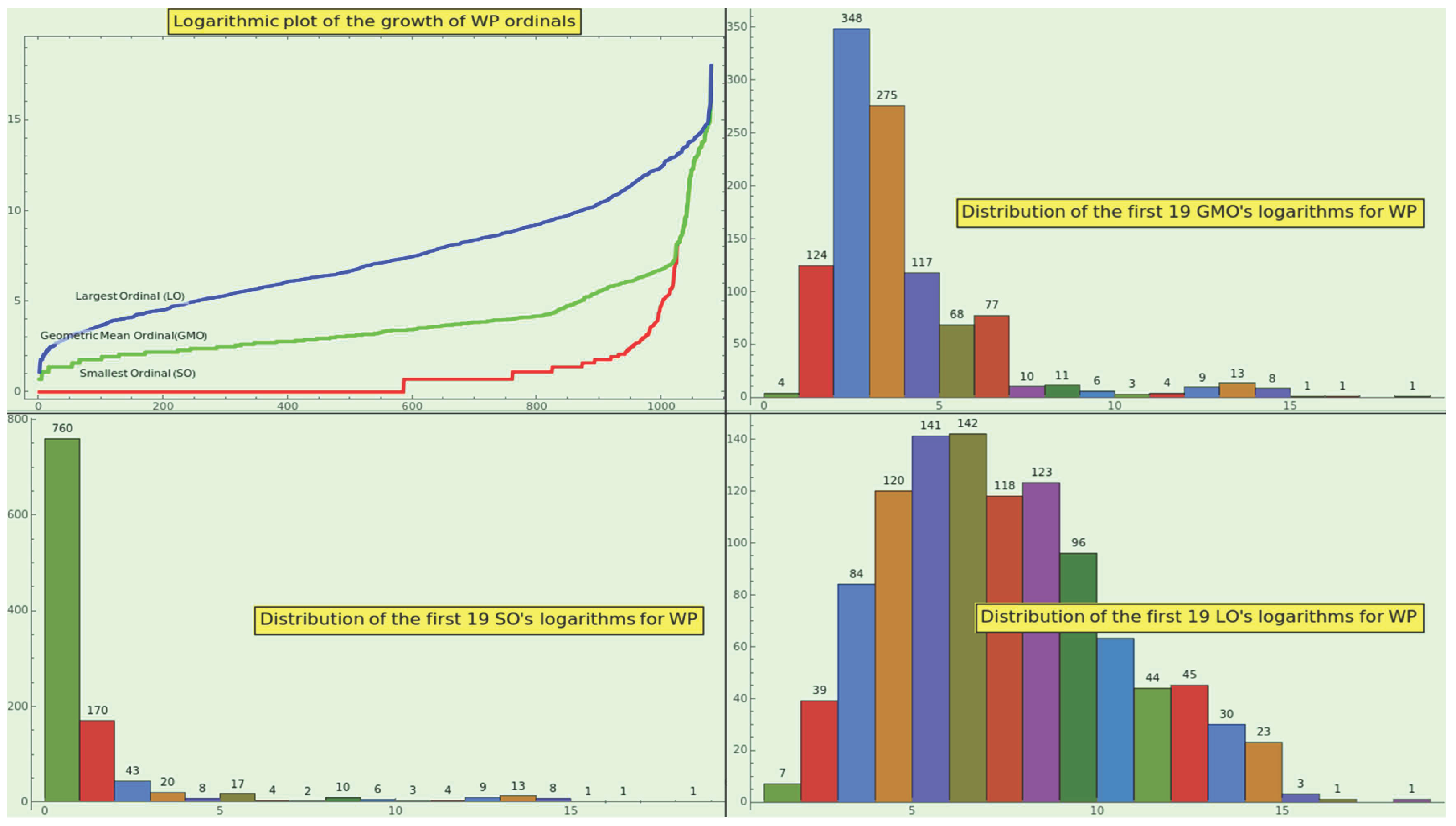

Figure 31.

Logarithmic plot of the WP ordinals (top-left) and histograms of the distribution of the SPO’s logarithm (bottom-left), prime geometric mean ordinal’s logarithm (top-right), and LPO’s logarithm (bottom-right).

Figure 31.

Logarithmic plot of the WP ordinals (top-left) and histograms of the distribution of the SPO’s logarithm (bottom-left), prime geometric mean ordinal’s logarithm (top-right), and LPO’s logarithm (bottom-right).

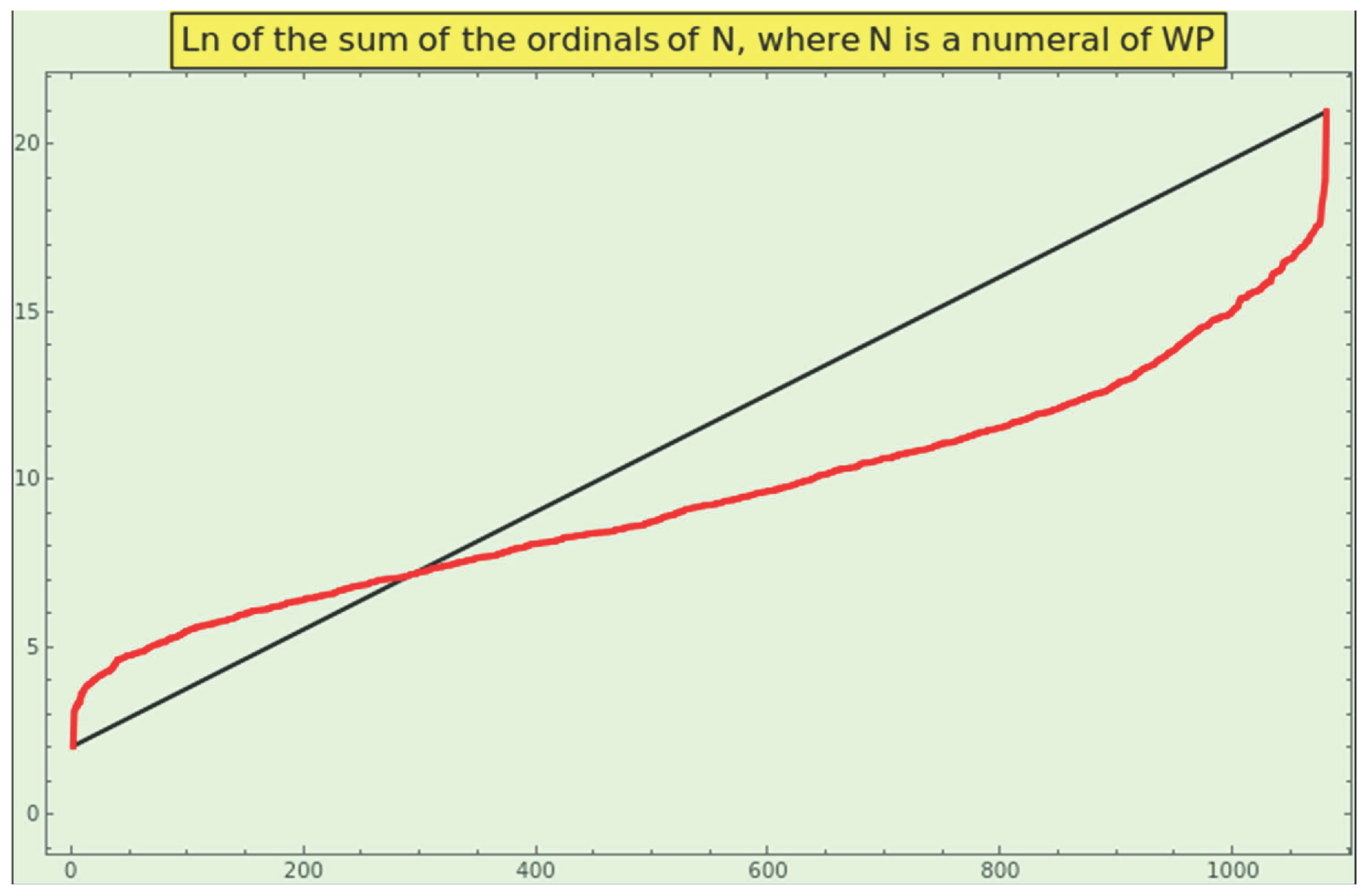

Figure 32.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every numeral in CT.

Figure 32.

Log-plot of the sums of the prime factor ordinals for every numeral in CT.

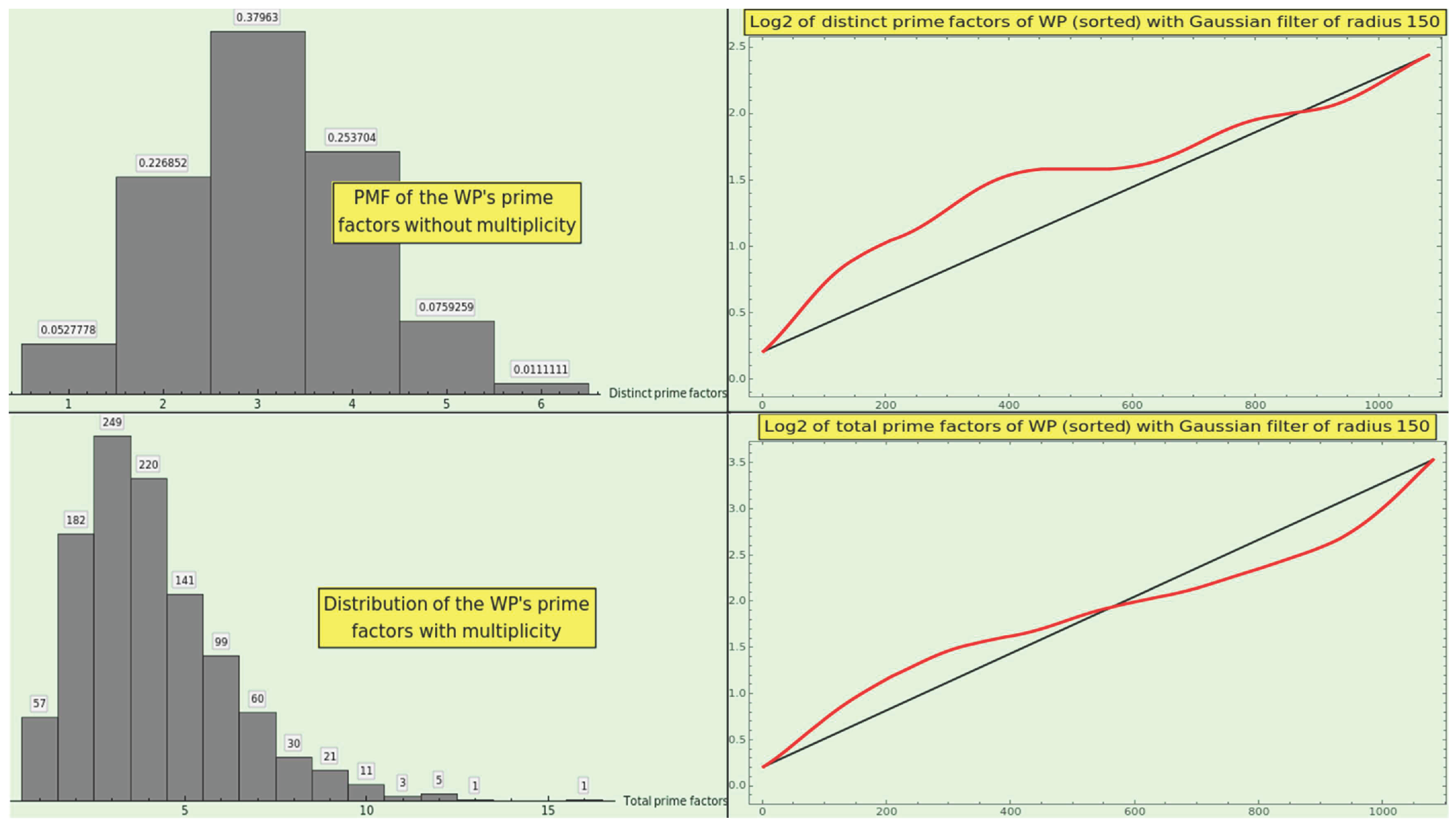

Figure 33.

Omega functions of WP.

Figure 33.

Omega functions of WP.

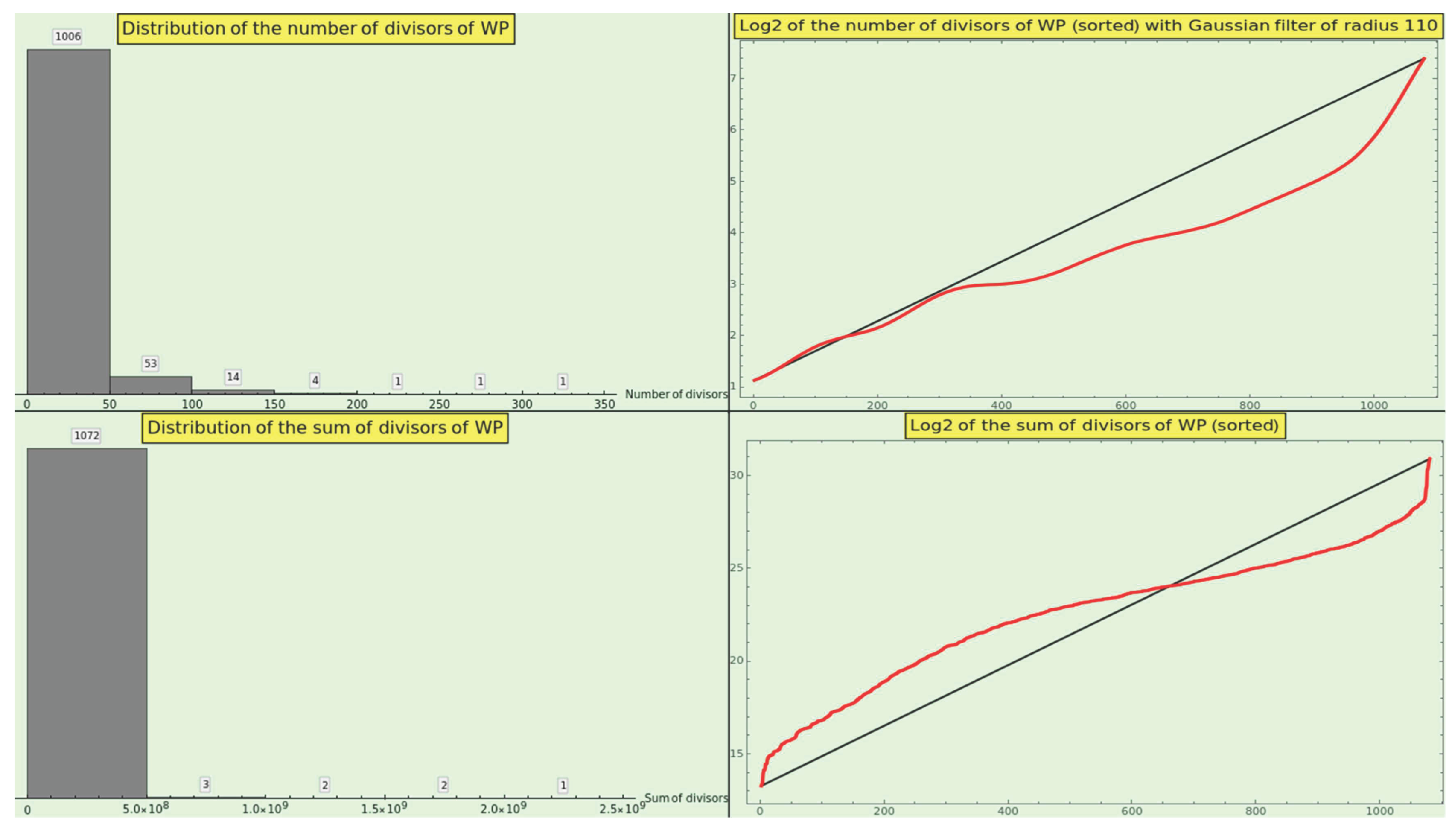

Figure 34.

Sigma functions of WP.

Figure 34.

Sigma functions of WP.

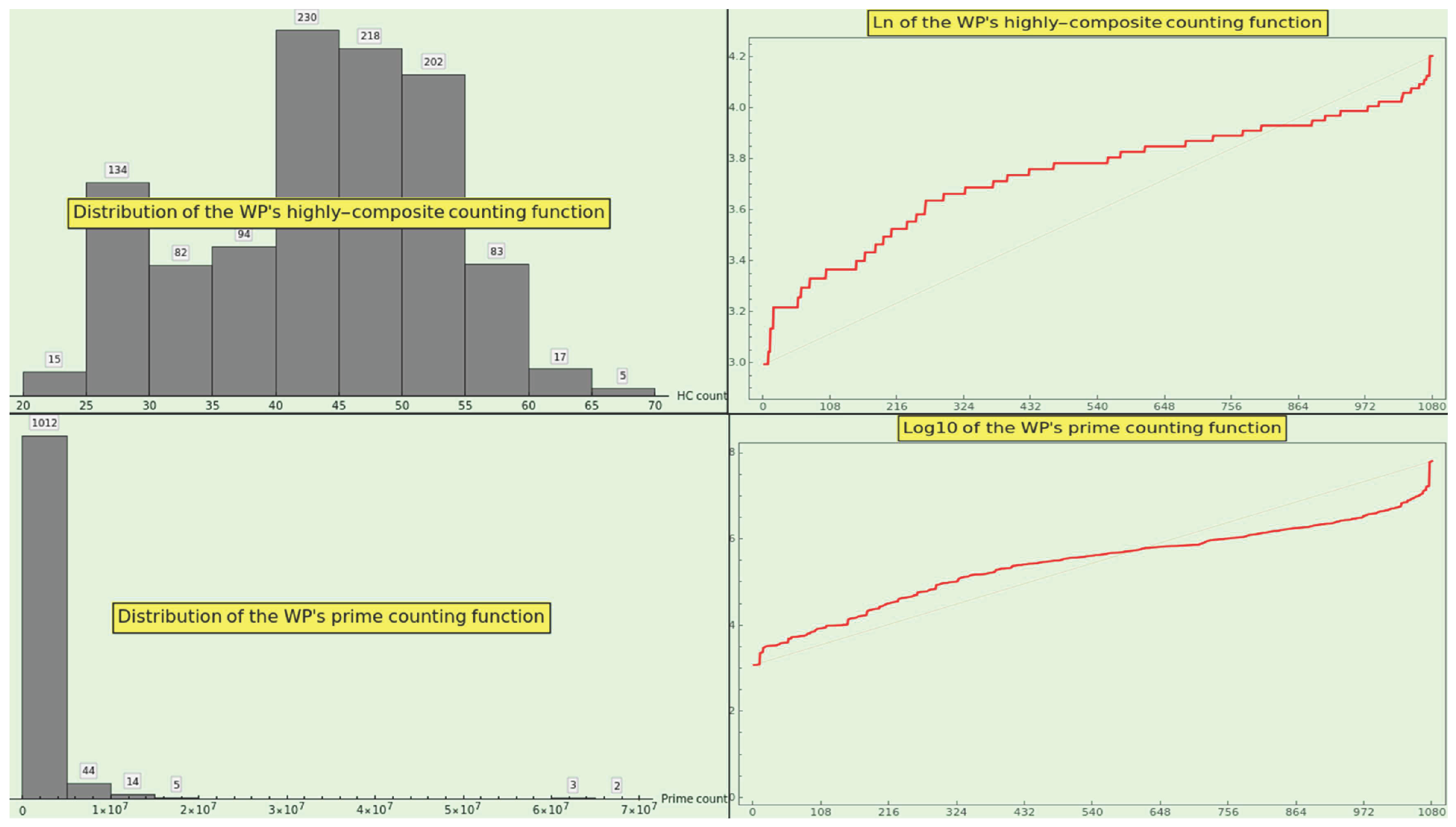

Figure 35.

Growth of the highly composite and prime numerals of WP.

Figure 35.

Growth of the highly composite and prime numerals of WP.

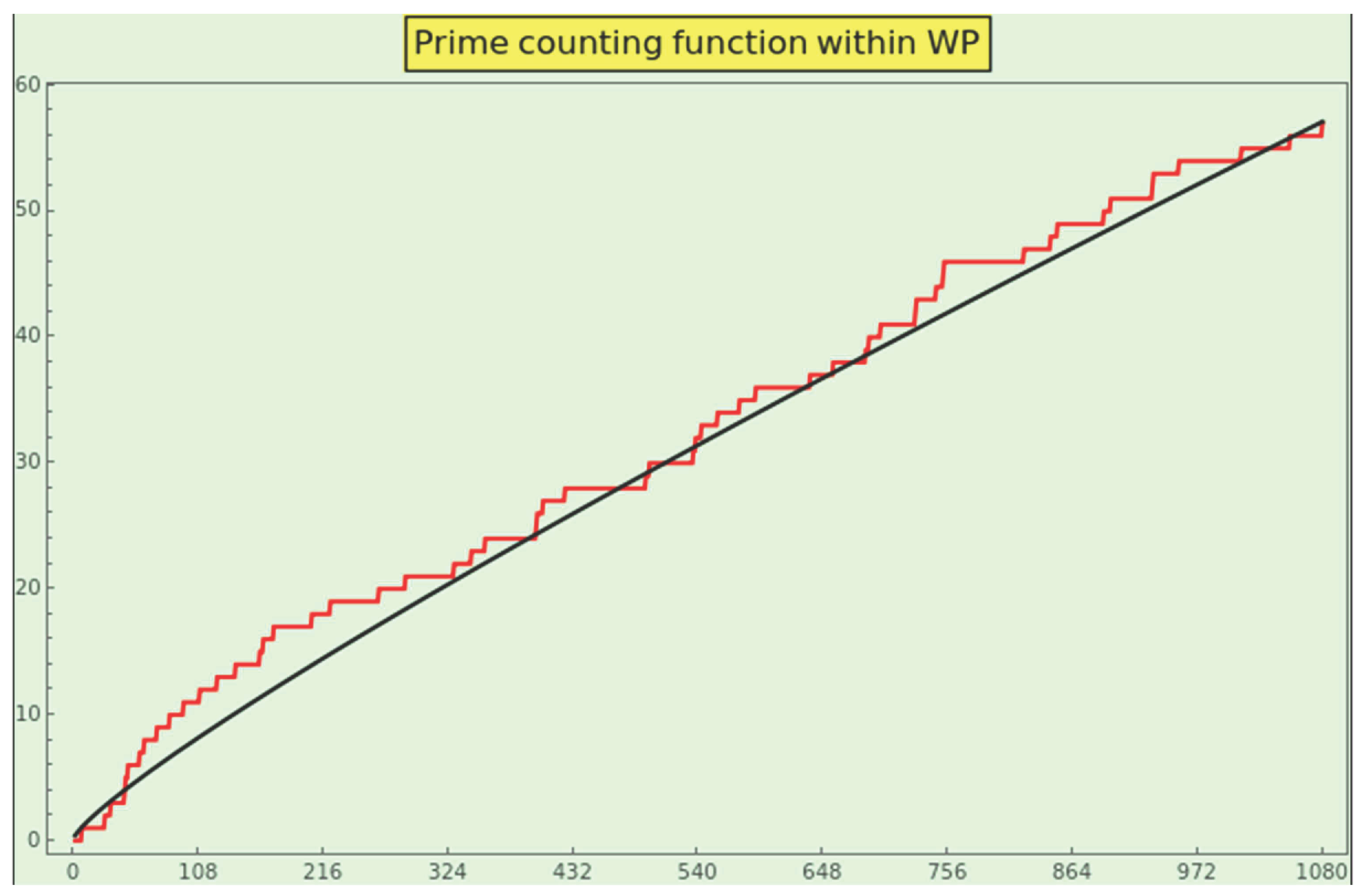

Figure 36.

Internal growth of the prime counting function of the numerals contained in WP, in red. We show the plot of the curve in black.

Figure 36.

Internal growth of the prime counting function of the numerals contained in WP, in red. We show the plot of the curve in black.

Figure 37.

Plot of the probability masses of the first WP primes, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime ordinals 3. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the based on the Anderson-Darling test, with RRMSE . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 37.

Plot of the probability masses of the first WP primes, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime ordinals 3. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the based on the Anderson-Darling test, with RRMSE . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 38.

Plot of the probability masses of the first SPOs of WP, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime 5. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 38.

Plot of the probability masses of the first SPOs of WP, normalized to an increasing maximal ordinal, compared with the probabilistic law of the minor prime 5. We display in full the factorization normalized to the 96th ordinal; we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the datasets have the same distribution at the level of significance based on the Cramér-von Mises test, and even less considering that the RRMSE is below . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal N, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 39.

At the top-left, we display, depending on k, the square-free almost-prime zeta function PMFs of the WP elements for various values of s, after calculating the convolution of the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times and even cross the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=13) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to WP and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the square-free partial sums.

Figure 39.

At the top-left, we display, depending on k, the square-free almost-prime zeta function PMFs of the WP elements for various values of s, after calculating the convolution of the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times and even cross the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=13) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to WP and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the square-free partial sums.

Figure 40.

At the top-left, we display the square-free almost-prime zeta function PMFs of the WP elements, depending on k, for various values of s, after calculating the convolution of the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these square-free almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=6) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to WP and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

Figure 40.

At the top-left, we display the square-free almost-prime zeta function PMFs of the WP elements, depending on k, for various values of s, after calculating the convolution of the frequencies with a normal filter of radius 3. We cannot model these square-free almost-prime profiles using a lognormal distribution; instead, we use a generalized gamma distribution. This fact explains why the log-plots for all k’s along the s-axis show a slight deviation from the straight line connecting the start (s=2) and end (s=10) points (top-right). The log-plots for all values of s along the k-axis change direction several times relative to the straight line joining the start (k=1) and end (k=6) points (bottom-left). The outline of these s-cuts is specific to WP and cannot be considered characteristic of a natural dataset. The three-dimensional log-plot in the bottom-right corner displays the complete surface of the partial sums.

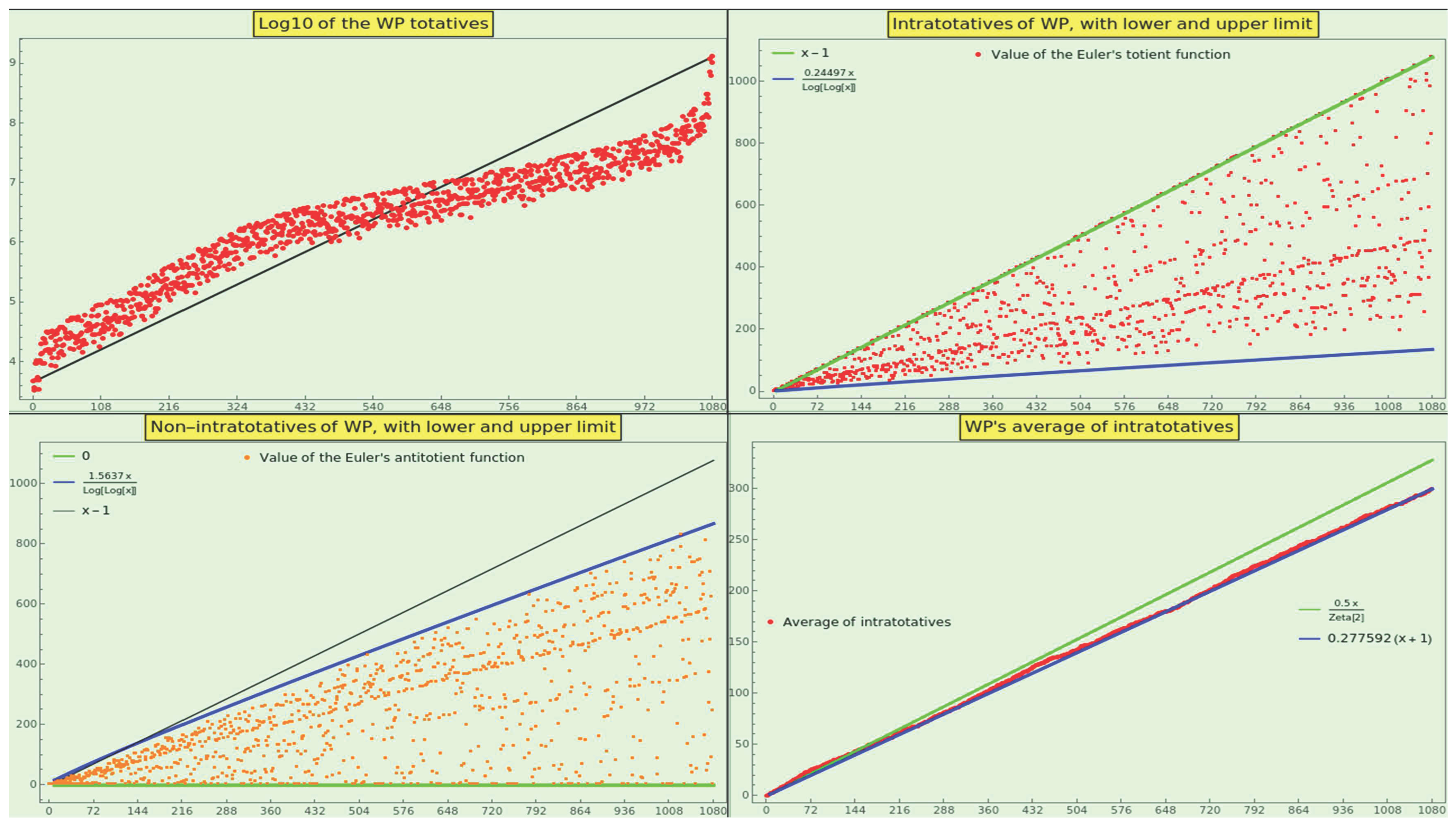

Figure 41.

Growth of the WP totatives (top-left), region of growth and plot of the intratotatives (top-right) and non-intratotatives (bottom-left), and average growth of the intratotatives (bottom-right).

Figure 41.

Growth of the WP totatives (top-left), region of growth and plot of the intratotatives (top-right) and non-intratotatives (bottom-left), and average growth of the intratotatives (bottom-right).

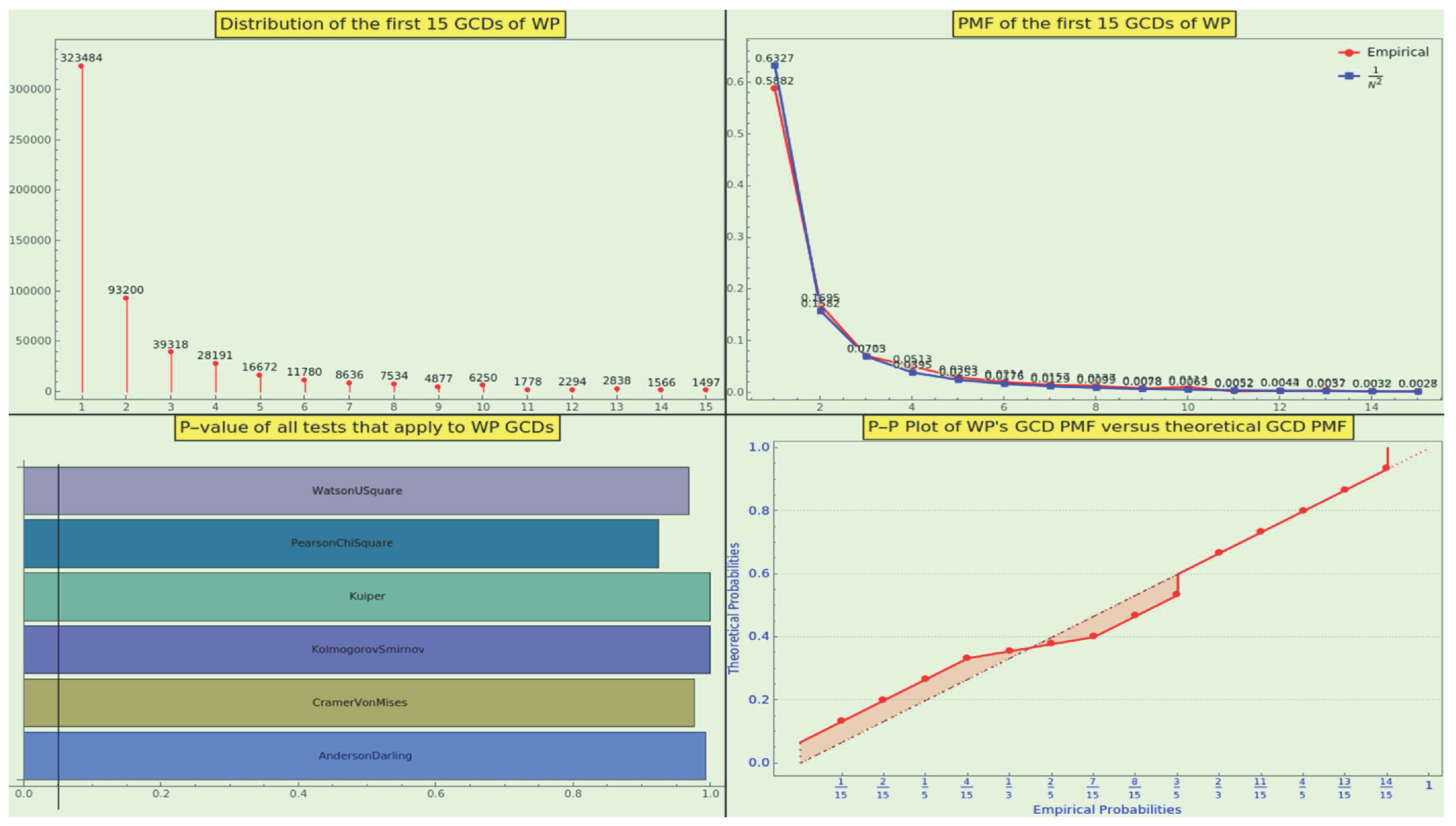

Figure 42.

The WP entries yield the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate that the GCD PMF of WP and the theoretical GCD PMF are hardly distinguishable.

Figure 42.

The WP entries yield the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate that the GCD PMF of WP and the theoretical GCD PMF are hardly distinguishable.

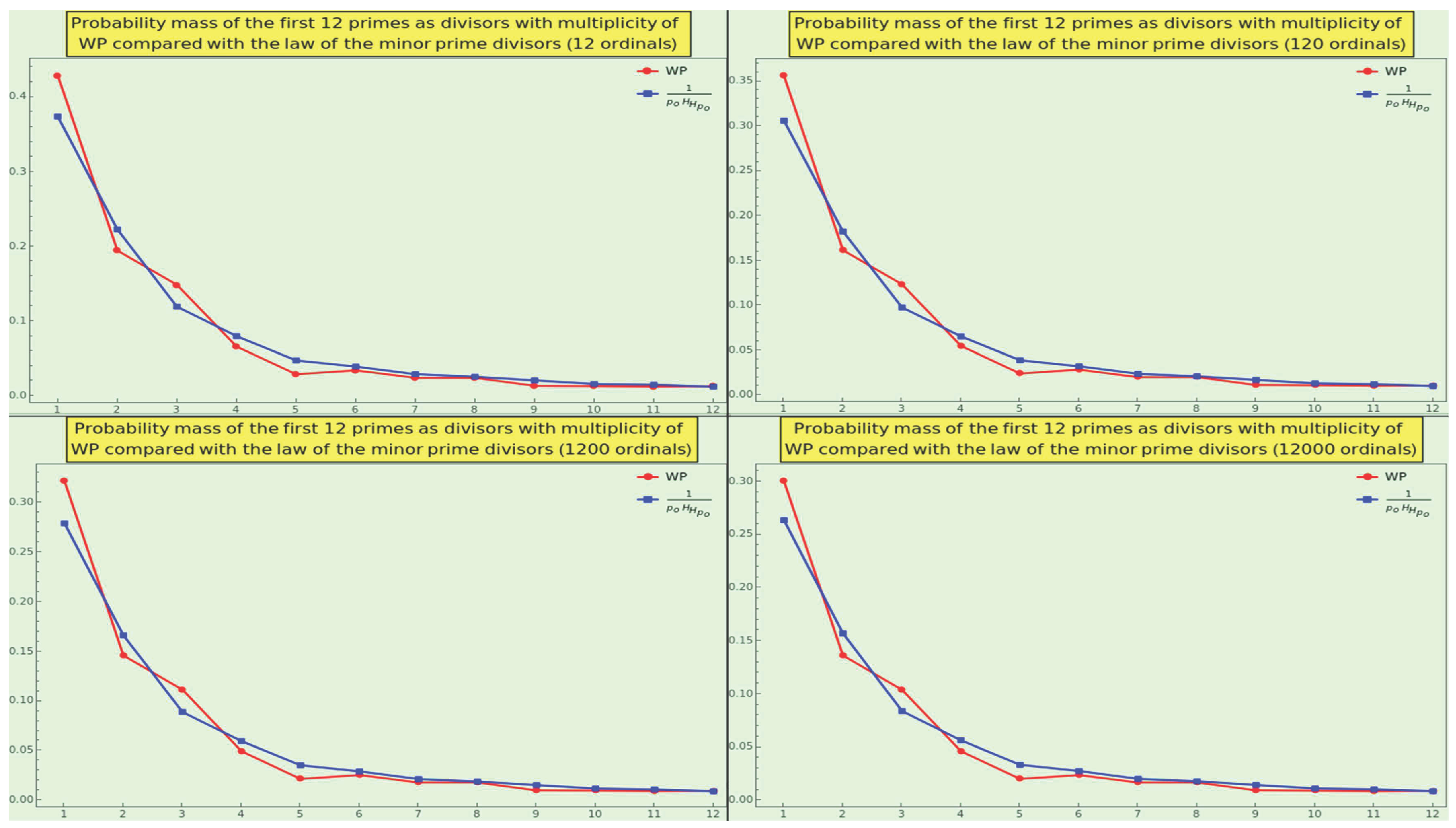

Figure 43.

Plot in red of the probability mass of the first 12 ordinals as divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of WP, compared with the plot in blue of the masses resulting from law 9. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

Figure 43.

Plot in red of the probability mass of the first 12 ordinals as divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of WP, compared with the plot in blue of the masses resulting from law 9. The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency.

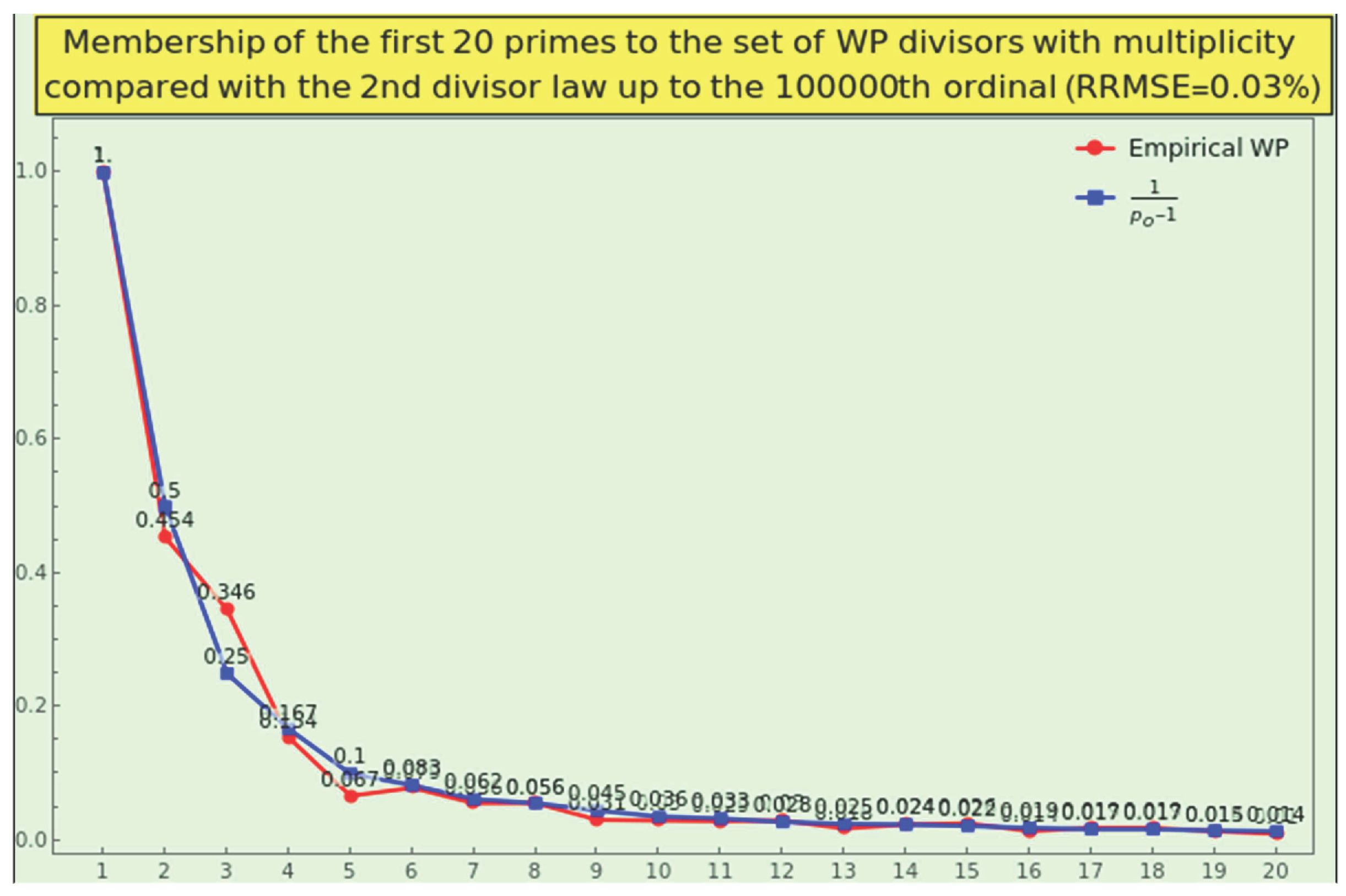

Figure 44.

Plot in red of the first 20 ordinal’s possibility masses of the prime divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of WP in comparison with the theoretical frequency relative to . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the law 10 (in blue) is excellent.

Figure 44.

Plot in red of the first 20 ordinal’s possibility masses of the prime divisors with multiplicity resulting from the factorization of WP in comparison with the theoretical frequency relative to . The x-axis indicates the prime ordinal o, and the y-axis indicates the occurrence frequency. The RRMSE between the empirical data and the data obtained from the law 10 (in blue) is excellent.

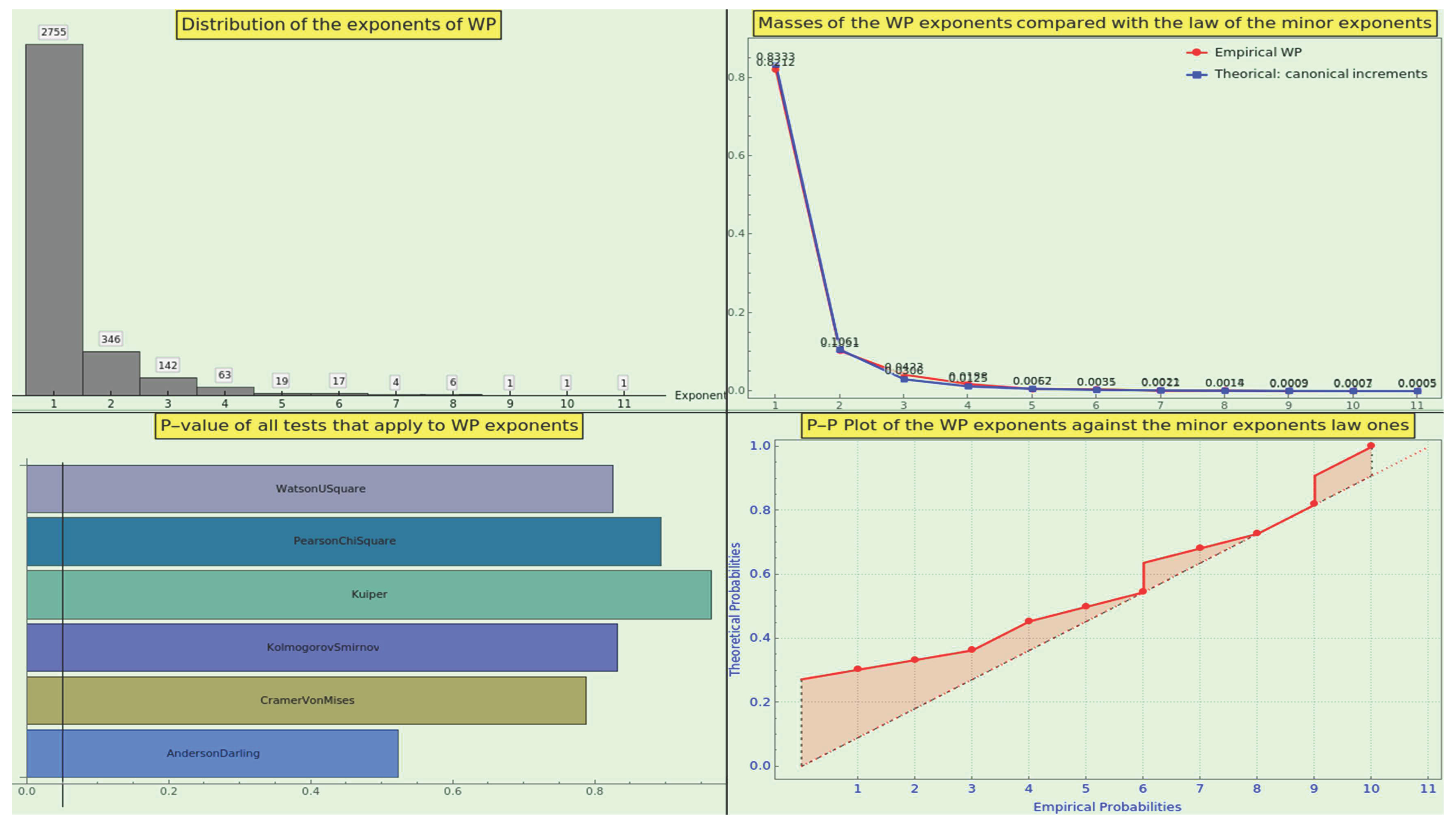

Figure 45.

The prime factorization of WP reaches the multiplicity 11, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the distributions of multiplicities are hardly distinguishable.

Figure 45.

The prime factorization of WP reaches the multiplicity 11, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and law in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied to this factorization, and the P-P plot indicate that the distributions of multiplicities are hardly distinguishable.

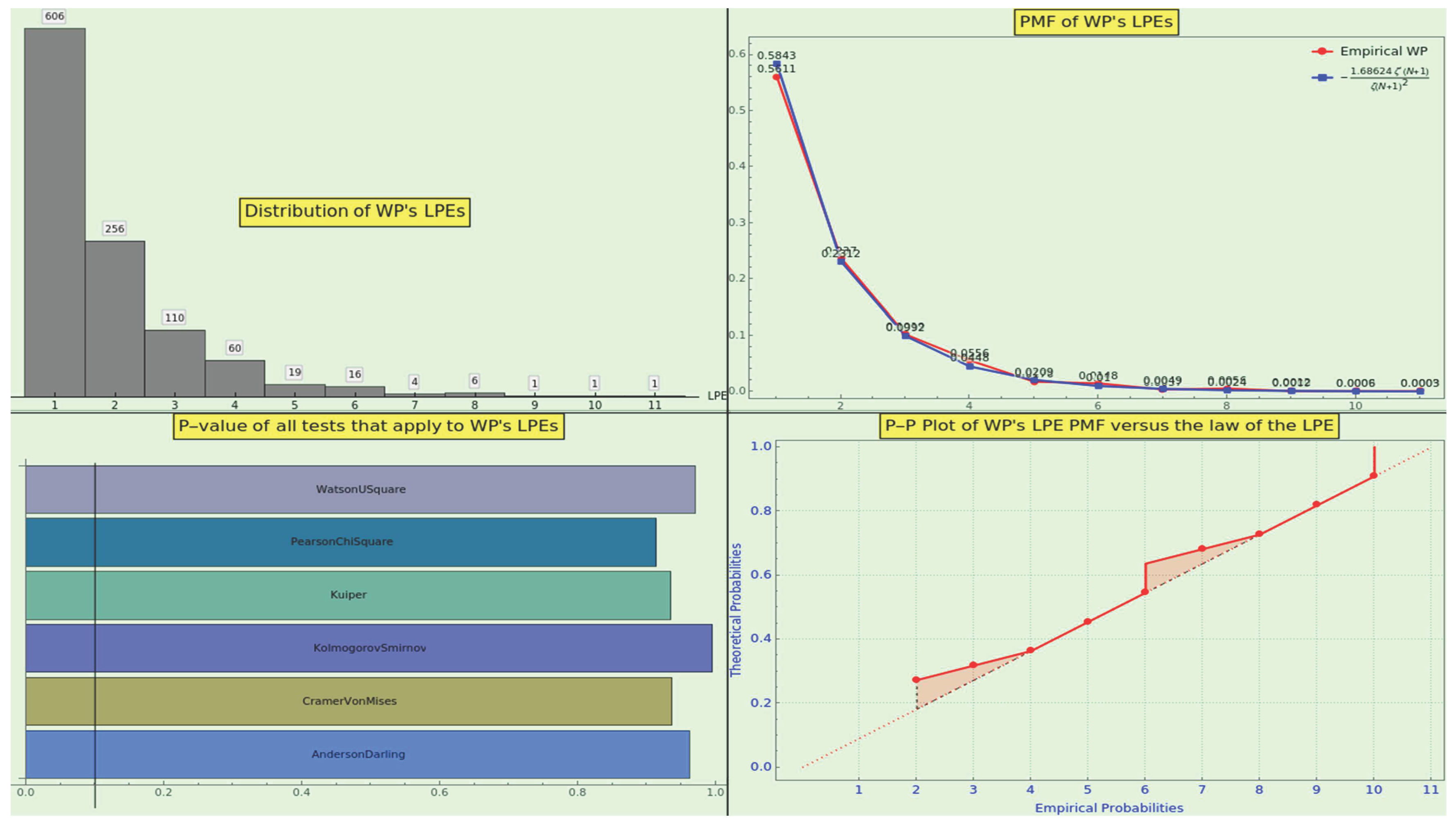

Figure 46.

The LPEs of WP reach the multiplicity 11, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and theoretical in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate excellent conformity.

Figure 46.

The LPEs of WP reach the multiplicity 11, as indicated by the histogram in the top-left corner. The plot of the frequencies (empirical in red and theoretical in blue), the p-values of the statistical test methods applied, and the P-P plot indicate excellent conformity.