1. Introduction

In this hypothesis, the structure of set is presented in the simplest and most straightforward manner: on a number line with three parallel axes. The even and odd numbers are separated along their respective axes, and all prime numbers are confined to the third axis. This makes it easier to graphically represent the set and find possible patterns in its distribution and gaps.

The distribution of prime numbers within the set of natural numbers has been a fascinating topic since ancient times. It has posed countless challenges to brilliant mathematicians and scientists. Even now, there is no clear way to determine its pattern.

1 However, all of this has given rise to beautiful proposals, complex hypotheses, such as the Riemann Hypothesis and his later about the distribution of primes of 1859 [10], the extraordinary polar coordinate graphs, and theorems that approximate its possible distribution, such as the Green-Tao Theorem, among many others.

We may or may not discover and decipher it, which is why it attracts us, given our restless nature. We are never satisfied with what we are told. In this article, we propose a possible, more direct, and narrower path to appeal to our innate curiosity and subliminal interest in the unknown. We have confined all prime numbers to see if we can find a pattern in their distribution along the number line or at least one that brings us closer to such a vision.

This article will not be very long as it only concerns the mathematical structure of the decimal system in its simplest form . We will examine a perfectly structured space to see if we can deduce the fundamental organization of the progression of prime numbers. The article aims to introduce a new structural scheme for the decimal system so that anyone interested in investigating this problem can build upon it. We will also present the most suitable procedure for developing functions that predict the position of the next prime number. This hypothesis does not replace any others, but rather adds to them and echoes the common interest in this search, as conjectures in its most recent research by Hector Pasten suggest [7]. Other methods of counting prime numbers have recently been proposed by Mihai Prunescu and Joseph M. Shunia in their article [8]. Many other advances have been made, but it is impossible to cite them all in this space.

2. General Statements

As the object of our study is prime numbers, and everyone knows what a prime number is and how it behaves, I don’t think it’s necessary to define them. It is a well-established fact that all prime numbers greater than 5 end in , or 9. Then, I can move on to the next step.

The structure of the decimal system is composed of the following elements:

We arrange a table with all numbers of set

The prime number 2 is the source of all even numbers in the set

. Equation:

The prime number 3 is the source of a half of the odd numbers in the set

. Equation:

No number proposed by 3 has the possibility of being prime.

The sequence generates all odd numbers in the set for .

Prime number 3 links all composite odd numbers between the row of evens and the row of odds.

The prime number 5 is the only ones ending in 5; all others are composite odd numbers.

All prime are alone without any other number in its column.

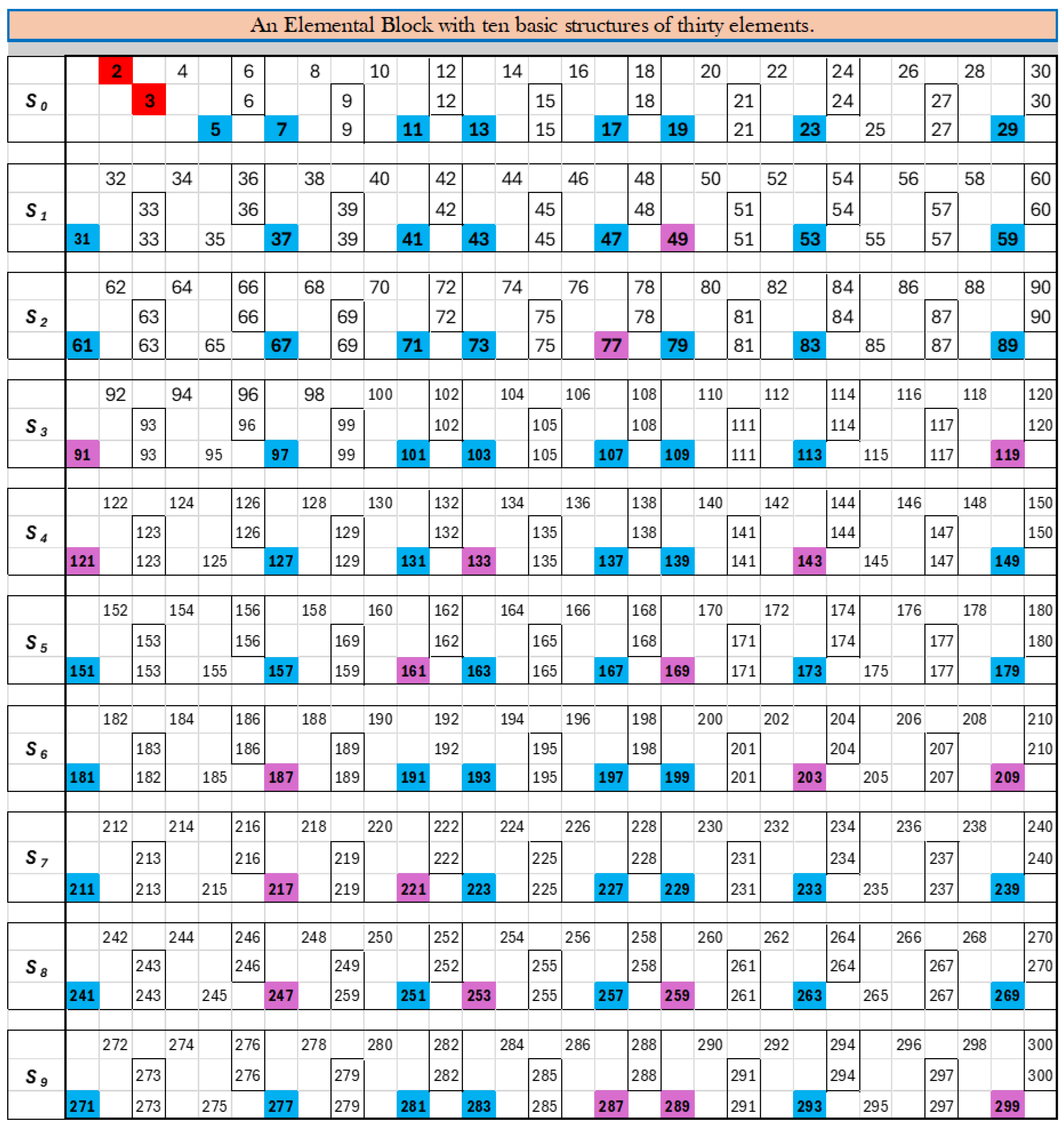

The table will be configured with 30 columns and three rows. The first row will contain the even numbers, the second row will contain the odd and even numbers formed by the number 3, and the third row will contain the odd numbers formed by the sequence of odd numbers , . These rows will be separated by their respective numbers .

These 30 columns and three rows form a basic structure of 30 digits. Then, 10 sets of these will form a block of 300 digits. This block configuration is repeated exactly in the next block, which goes from 301 to 600, and the next from 601to 900 and so on.

After 10 blocks of 300 digits, a block of

up to 10 blocks is formed to make a set of

, which with 10 blocks of

will be a blocks of

, and so on. See

Table 1

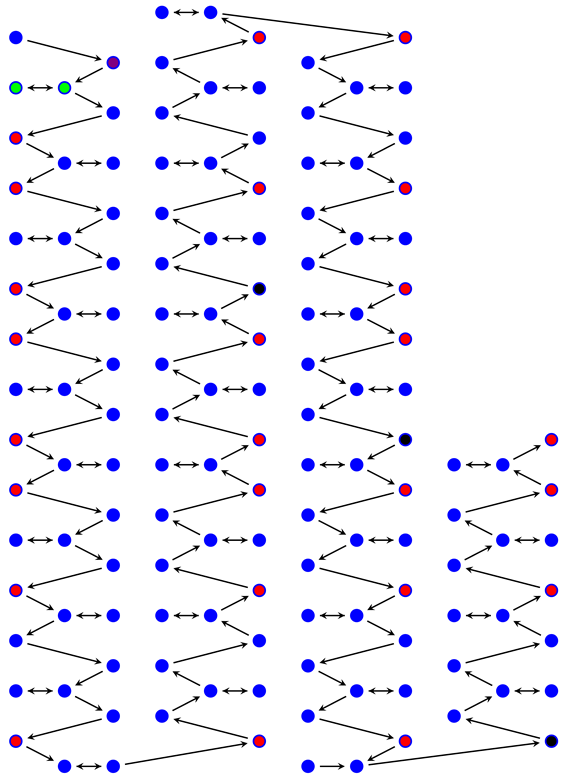

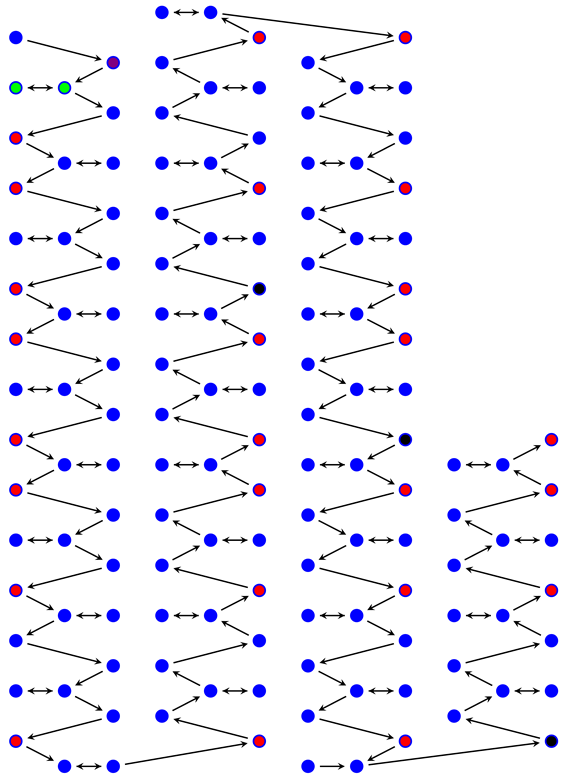

The third row of each basic structure contains all possible prime numbers. See

Figure 1 The third row has 15 digits, but only eight places are available for prime numbers. The remaining rows are occupied by links of three, and two places are always occupied by multiples of five, maintaining the same position throughout.

The first structure is the only one in which prime numbers occupy all its 8 places. If we consider 2 and 3 prime position, there are 10 prime numbers because the number 25 has already occupied its place. In the second basic structure of 30 digits, which go from 31 to 60, from the eight places available for primes one is occupied by the 49 which are the product of , then will be seven primes only.

In the next basic structure, from 61 to 90, one place is occupied by 77, the product of , so there are seven primes. Beyond the hundreds, more prime factors, which form composite odd will be introduced in each basic structure of 30 digits.

As we can see, seven of the 15 places on the third row are always occupied by factors of 3 and 5 from the first basic structure of 30 digits. Five of the 15 places are for links of three, and two are factors of five. This structure repeats exactly throughout the field of natural numbers.

Symbology: The blue squares represent prime numbers and its position, and the violet squares represent odd composite numbers that have replaced prime numbers. The red squares are 2 and 3 primes. Carefully observe

Figure 1.

It is important to note that the positions of the prime numbers remain the same throughout the table and in subsequent structures up to the desired number of blocks. Therefore, we can define them as an unalterable structure. Regardless of the basic structure to which a position corresponds—whether

,

, or

—the eight positions designated for prime numbers are preserved, whether or not they are occupied by them.

Denote

C as a column and the subscript as the relative position along the basic structure. As you can see, it coincides with the prime positions of the first basic structure, except for 5, because there will be no prime in its position from here on out.

The data that we treat here as subscripts of the elements of the set S, are in turn the values that we are going to use to calculate the separation between primes, because this configuration is preserved in the entire set of all structures .

The progression of the basic structure’s configuration occurs as follows: The elementary block of this configuration is . Then, a progression of blocks can be seen at each scale.

Considering the probability of finding a prime number based on the available spaces in each group of blocks reveals that it remains constant throughout development. It is

, but this is not an accurate representation of what we expect to find in prime numbers because the growth rate of prime numbers is erratic. As a number more is larger, the gaps between prime numbers increases. Therefore, having a large number of available spaces does not guarantee that they will be occupied by prime numbers. Nevertheless, this hypothesis provides a new perspective on how prime numbers can be organized, at least in our daily experience, and on how many problems can be formulated under this new perspective. The reason prime numbers decrease as

values increase is the primes themselves. They are eager to construct and integrate ever-increasing numbers. They have an insatiable appetite to destroy nothingness, driven by their power to be infinite—a property proven by Euclid’s Theorem. [1] [Proposition 20, Book IX]

Prime numbers are more than any assigned multitude of prime numbers.2 Each prime number greater than seven that is multiplied by itself and all successive primes generates an odd composite number that occupies exactly one of the eight available places. Therefore, the number of primes will decrease in that line.

Then, perhaps the best thing is to find the composite odd numbers and see the places they occupy and therefore the places they do not occupy will be occupied by the prime numbers. Now, we can easily deduce, which of them they are.

Let’s take a look at some examples.

The first block is , so see 2 for the primes and their factorizations, where the products are broken down.

Therefore, of the 80 places available, 20 are occupied by odd composites and 60 by primes. This block is the one that contains the greatest number of prime numbers.

Now, let’s look at the second block, . The factorization must begin with seven, followed by the prime that comes after the last factor of the previous block. The same applies to the others.

Therefore, of the 80 places, 32 are occupied by odd composites and 48 by primes.

However, this procedure requires a lot of brute force. If we use computational resources to develop an algorithm that performs operations and satisfies conditions for prime or composite numbers, I will try to find a solution with a lower computational cost, if possible. However, this has yet to be put into practice. For now, all development of these operations is done with pencil and paper.

Therefore, I propose a different method that only works with the eight possible spaces to find numbers divisible by prime numbers. This reduces the process to eight operations for each prime number. The first division is discarded, and the next one is taken and so on.

Let’s look at an example.

Find the place where the prime could exist among the eight available places in the following set:

First, we divide each number by seven. The probability of finding a number divisible by seven is highest, followed by 11, 13, and so on. Even in very large quantities there is a probability that some are divisible by 7.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The number is divisible , then is prime.

The number is divisible , then is not prime.

The only prime number is , all the others are composite odd numbers.

3. Gaps Between Primes

The separation between consecutive prime numbers has been the subject of extensive research, which has laid the foundation for understanding their distribution among large numbers. Although it will not be possible to reach all of them given their infinite nature, this has not discouraged us from seeking new methods, new challenges, and new paradigms that allow us to shed more light on the subject. The distribution of prime numbers along the line of positive integers begins with the Prime Number Theorem. This theorem originated as a conjecture based on the work of Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665), Anton Felker (1740-1800), Jurij Vega (1754 - 1802), and Adrien-Marie Legendre (1752 - 1833). These mathematicians worked with tables of primes, logarithms, and polynomials respectively during the 16th and 17th centuries. In Legendre’s book: Essai sur la Théorie des Nombres, published in 1789, he cited the following text:

"Ce théorème , l’un des principaux de la théorie des nombres , est dû à Fermat ; il a été démontré par Euler dans divers endroits des Mémoires de Pétersbourg , et notamment dans le Tome I des Novi commentarii". (page 166, SECONDE PARTIE PROPRIÉTÉS GÉNÉRALES DES NOMBRES, § I.Théorèmes sur les nombres premiers.)

"This theorem, one of the most important in number theory, is due to Fermat; it was demonstrated by Euler in various places in the Petersburg Memoirs, and notably in Volume I of the Novi commentarii."

works contribution of his predecessors: [5] Legendre presented the first formal conjecture on the size of

. The works of Gauss (1777-1855) who introduced the prime counting function [2]

, Dirichlet (1805 - 1859) , Chebyshev (1821 - 1894), Euler ( 1707 - 1783) in its prove of theorem found the formula now known as

Euler’s product

and Riemann (1826 - 1866) also made significant contributions, including the discovery of the asymptotic law for the distribution of prime numbers, which was proven independently by Jacques Hadamard (1865 - 1963) and Charles Jean de la Vallée Poussin (1866 - 1962). More recent advances include the work of Yitang Zhang, [12] Terence Tao, and Ben Green, who proved the Green-Tao theorem [3] on the existence of large arithmetic progressions in prime numbers.

The Riemann hypothesis (1859) [11] is a brilliant proposition that remains unsolved. Using the sigma function under a complex number system shows a possible new pattern for understanding the distribution of prime numbers. [9] translated by David R. Wilkins, 1989.

The explicit Riemann formula is as follows:

However, definitive proof of the pattern followed by the distribution of prime numbers still eludes us. While there has certainly been great progress, for large numbers, any structure that could define a pattern breaks down.

This hypothesis does not aim to resolve this issue because, due to the infinite nature of prime numbers, it is impossible to do so. Nevertheless, we can discover fascinating aspects that will greatly advance our understanding of the structure of the set of natural numbers, which we can then extend to other sets.

3.1. What Are the Gaps like?

Many authors have defined the separation between two consecutive prime numbers as the difference between them. The general equation is , which results in an even number of spaces except between 2 and 3. These spaces are denoted as .

In the present hypothesis, the real gaps between consecutive primes are the places occupied by composite numbers in strict order between two primes. We cannot use the arithmetical difference because the position of and are occupied by themselves. Therefore, we need to subtract one at this difference.

Taking these premises into account, the gaps between prime numbers have the following properties:

All spaces between consecutive prime numbers are odd, except for the space between 2 and 3, which is zero.

Some gaps are prime numbers and are sometimes preserved in extensions.

The separation between two twin prime numbers is always one.

The pattern of all spaces between consecutive primes is the separation between the first eight primes. Thus, one can use this pattern to extend the distance between primes separated by a composite odd number.

The position of each prime number in the initial base structure is precisely defined, and this pattern continues for all prime numbers.

All primes are supported only by eight columns.

By doing this, we reduce the range of possible prime numbers to 30 digits. Since the sequence increases by a factor of 10, we can expand the search range to include larger prime numbers and break down each basic structure within it.

3.2. Looking for a Equation

According to the proposed structure, we can determine how prime numbers are interspersed to occupy the available spaces through a function that relates their factorization in a sequence.

The factors of 3 and 5 are included in the structure by their own weight. Therefore, we do not need to worry about them.

The factors of . are the numbers that need to be distributed among the eight spaces.

The remaining spaces must to be prime numbers.

Factoring by each prime in successive sequences explains why some of the eight places are occupied by these products. As the number line increases, so does the ratio of odd composite numbers.

Every prime number greater than 5 must be factored by all the primes that come after it, as well as by itself.

and so on.

A large number of composite odd numbers is produced by factoring 7. This number decreases as the sequence of larger prime numbers increases.

The product of each prime factorization is always an odd composite number that replaces a prime number structurally.

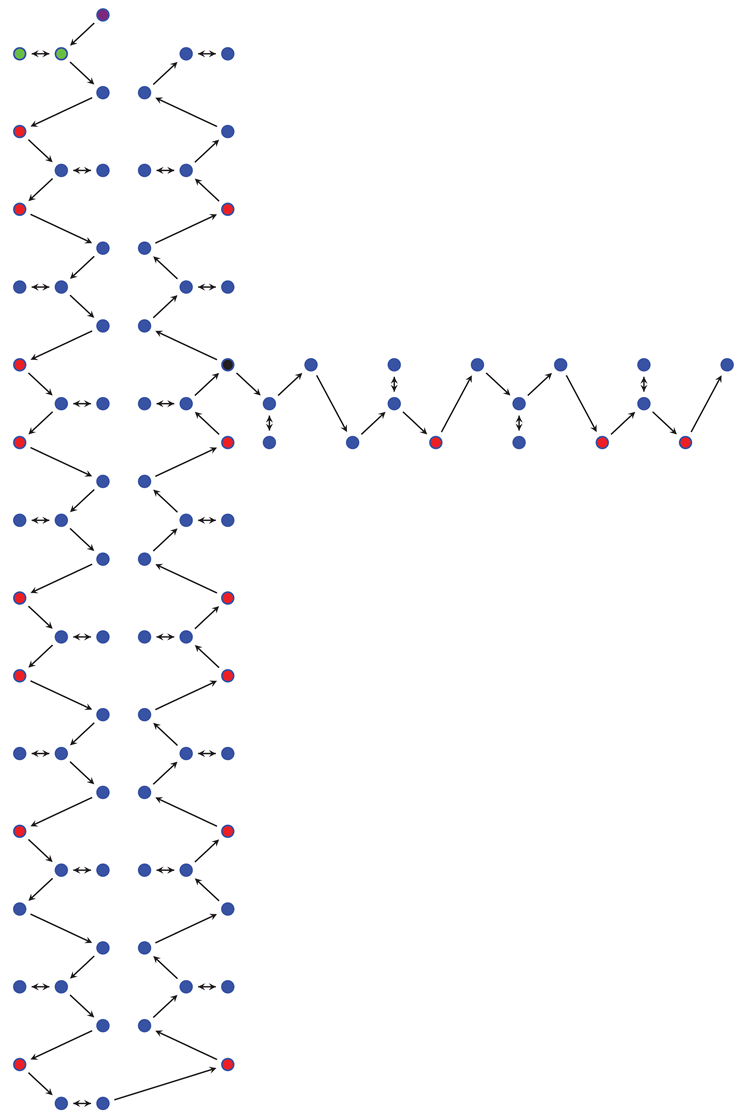

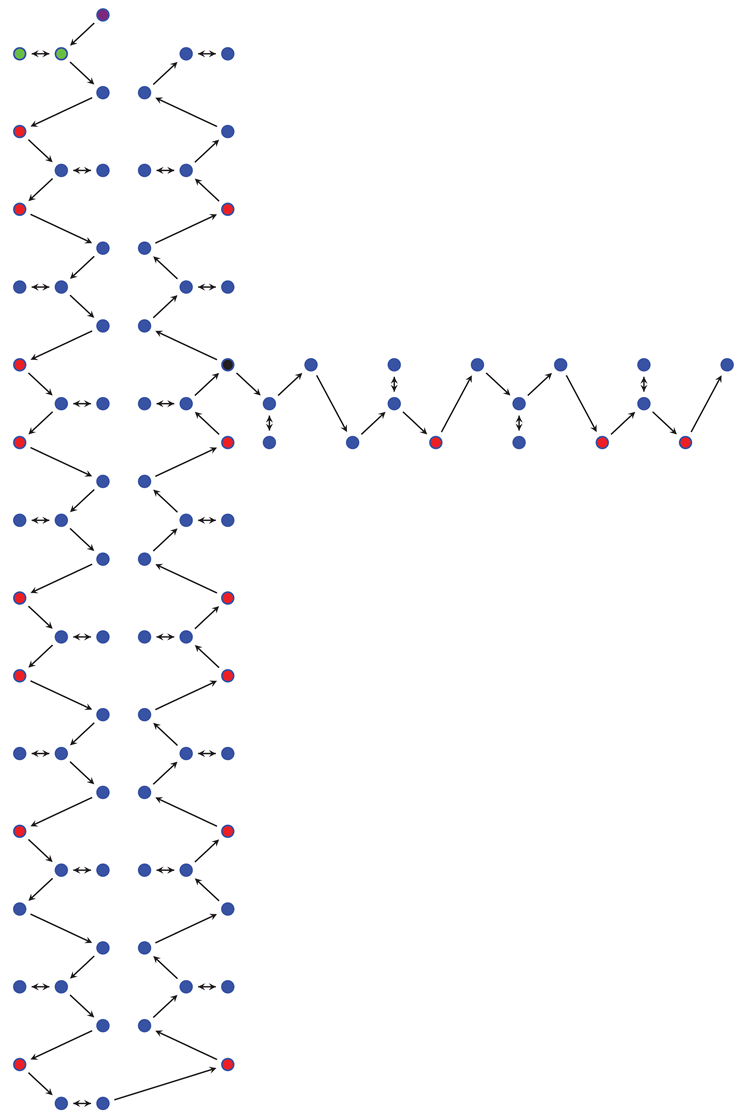

The gaps between primes can be determined precisely from the initial basic structure and will increase when odd composites are introduced. See

Figure 2.

Applying the previous criteria, we can describe a sequence of composite odd numbers that will replace the prime numbers within the first 300 digits.

From the

Table 2 above, it can be seen that, except for items 2 and 3, there are 80 odd numbers with a high probability of being prime in the 10 basic structures, each of which has 8 available spaces. However, by the result of the factorization of primes in the same range

to

, 20 of these odd numbers are composite, so there should only be 60 prime numbers, which is confirmed.

This pattern continues throughout the entire number line, and the gaps can be calculated.

It is important to see the gaps between each prime in order to understand its distribution along the numerical line.

3.2.1. Formulas

As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, our number line consists of three rows. The first row contains all the even numbers produced by factoring

by each natural number. The second row contains the composite odd numbers produced by factoring

by each natural numbers, and the third row contains all the odd numbers, some of which are prime, produced by

. All of our prime numbers fall on the third row and occupy eight columns due to their distribution. Five of the remaining seven spaces are occupied by composite odd numbers produced by factoring

by natural numbers, and two by those produced by

. This arrangement is maintained throughout our number line. The first row is ruled out because it contains even numbers. The second row is also ruled out because its numbers are composite odd numbers. Thus, only the third row remains as a possible location for prime numbers.

Each position must be denoted as where invariably.

The next equation is used to calculate the difference between two primes within the same basic structure, i.e., between

and

of

.

Where

g is the gap between consecutive primes in column and .

is the basic structure , defined by . In this case the structure is the same for both primes.

The subscripts 30 on both sides mean that the subtraction is normal in the same

The vertical bar | indicates whether a subscript is being added or subtracted.

Once it has been determined that a number,

N, is a prime number,

, we can know its value and position if we know the block, the basic structure, and its column. Here

, so

or

The same result occurs, for example; if the basic structure is the seventh structure, but if and only if these positions are occupied by prime numbers.

The next equation is used to calculate the difference between two primes with different basic structures. The size of the separation between the two structures does not matter.

Where the term

an other case if

we need to play the following formula:

Here,

is the number of basic structure at the end.

The same means as in equation

1 plus the following items are added.

is the basic structure of , defined by . In this case, the structure differs for both primes and can be as far away as the consecutive primes allow.

The term K is a counter that indicates how many complete basic structures are between the initial prime and the final prime. So, if , then there are no empty structures below. If , then one entire structure is empty, and 30 must be added to the equation. If , then 300 must be added and so on.

The superscript on the right bar indicates that should be subtracted of 30 because you need to go to the end of the row. In the case of the left bar, the subscripts must be added according to the term K plus the gaps from the beginning of the final row to the position of the last prime in this row.

Let . Then, let’s look at the following example.

As we apply , then , so on the next block.

According to the results of Example 3, the gap between the prime number in column 7 of the seventh basic structure and the prime number in column 19 of the first basic structure of the next block is 131 places.

Now, suppose . If there are primes in position 23 of the basic structure number 8 and in position 23 of the 1 structure, then the gap will be seen in the next example. So, we need to consider that a block is made up of ten basic structures. Therefore, there are ten complete blocks plus one structure of the eleventh block.

As we apply , then , so on the eleven block.

So, according to the results of Example 4, the gap between the prime number in column 23 of the ninth basic structure and the prime number in column 23 of the one hundred one basic structure, which made 10 blocks plus one basic structure is places, .

You can use K as large as you like, but remember that K is a basic structure counter in which no prime number exists in its eight positions. If a prime number does exist, the difference with respect to the immediately preceding prime must be determined. It is even possible that entire blocks will be found without a prime number in any of their 80 positions, or in any of their 800 or positions. It has certainly been proven that even for very large numbers, significant differences exist. However, there is a factorization that helps reduce their size: factorizing the numbers by all the prime numbers that come after them.

3.2.2. Long Count.

In this section, we will explore the fascinating structure of numbers in their decimal form from a new perspective. We will learn to write their sequence as repeating cycles where the base elements behave like a wheel system that can turn infinitely. To understand how they are distributed, we must adopt the most effective counting method. First, we need to understand their structure from its foundations, as well as the function of each of their fundamental elements.

Writing numbers in cycles will provide a breakthrough that we cannot yet envision but will surely discover as we delve into their secrets.

The structural basis of our decimal system is presented here as a structure of three fundamental elements.

First, I present a general description of the structure, and then I describe its function.

The number three is the first brick of the construction. It is the backbone of the entire system.

The three can be arranged in three rows, where the even numbers, odd composites, and primes can be seated in strict order, separated from each other.

The rows tend to infinity, but for the purposes of study, it can be cut off at 30.

The rows at 30 form the basic structure and the first wheel of the system. In this manner, it can progress to the next basic structure, and so on, ad infinitum.

The fundamental block of 300 consists of ten basic structures of 30 elements. This is the second cycle of the system. Each cycle of a block grows the sequence of numbers by 300 and continues to infinity.

Now, I will describe the function of the two elemental numbers for this kind of structure: 2 and 3.

The number three produces half of the even numbers and half of the odd numbers. Each is linked to the even numbers produced by two and the odd numbers produced by . The number three runs along the middle row. Its formula is , so when n is even, the product is even, and when n is odd, the product is odd. No number produced by 3 will ever be prime.

All even numbers are produced by and runs along the first row.

All odd numbers are produced by and run along the third row (including all the primes), except for the prime 2.

Now, I will describe the function of the basic 30-element structure.

The structure of 30 elements is fundamental to visualizing the exact positions of the primes. The first basic structure is the model because it is the only structure in which all eight available places are occupied by primes.

The basic structure is fundamental to determining the gaps between primes and tracing the development of these gaps back to the following structures.

Regarding the possible distribution and placement of primes, all that come after copy and repeat the basic structure exactly. It is the first wheel of the system, with successive numbers arranged in the same manner.

The basic structure has 30 places, or columns

Figure 1. Fifteen are occupied by evens and fifteen by odds. Eight of these places will potentially be occupied by primes.

Now, I will describe the function of the basic 300-element block structure.

Understanding the block structure is fundamental to understanding the cycles of numbers. It is composed of ten basic structures of 30, so it comes from any number with a unit of one and ends with a number whose unit is zero, 300 numbers away. For example, the numbers 901 to and to follow this pattern because the basic structure model is repeated here.

To identify each basic structure within the block and know which numbers are attached to them, each basic structure is numbered from 0 to 9.

The numbers representing each basic structure do not have any value in the number system because they only serve as a reference to the number of basic structures.

The blocks are repeated exactly every 300 numbers, and this is enough to denote a large number, as large as you wish.

General arrangement.

| Number notation |

| Blocks |

Identity |

Columns |

|

|

|

|

|

Initial |

to |

Final |

In the section of columns is written the number to correspond to de identity of the basic structure.

The last one, two, and three digits of every number are involved in the range of initial and final numbers, and this pattern repeats in each block. Therefore, we can establish this relationship as a constant arrangement.

Using

Table 3, we can determine the range in which a number falls if we know its final three digits. We can also determine its position and whether it is prime or composite odd. We can also read a number in this notation and convert it to traditional notation. This table is an essential guide for searching for or writing numbers in one or both directions. For example, the identity number

contains all the numbers from 151 to 180, including the extremes. Therefore, if you have a number such as

, the 169 is included in the five basic structures. If the number is

, then the identity number is now

.

Even if we have a very large number, which is the intention, we can find the number of blocks and use the first three digits to configure the block, removing the other digits. For example, If the first number of a block is and the block number is , then we know that the last number of this block is . Therefore, we can use only the numbers from 901 to 200 within the block, taking into account the whole number, and so on.

Table 4.

The first four blocks are listed here in order.

Table 4.

The first four blocks are listed here in order.

| Number notation |

|---|

| Blocks |

Identity |

Columns |

Blocks |

Identity |

Columns |

| … |

|

10 |

300 |

|

Initial |

|

Final |

… |

|

10 |

300 |

|

Initial |

|

Final |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

31 |

|

60 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

31 |

|

60 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

61 |

|

90 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

61 |

|

90 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

91 |

|

120 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

91 |

|

120 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

121 |

|

150 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

121 |

|

150 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

151 |

|

180 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

151 |

|

180 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

181 |

|

210 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

181 |

|

210 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

211 |

|

240 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

211 |

|

240 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

241 |

|

270 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

8 |

241 |

|

270 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

271 |

|

300 |

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

271 |

|

300 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

31 |

|

60 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

31 |

|

60 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

61 |

|

90 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

61 |

|

90 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

91 |

|

120 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

91 |

|

120 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

121 |

|

150 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

121 |

|

150 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

151 |

|

180 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

181 |

|

210 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

181 |

|

210 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

181 |

|

210 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

211 |

|

240 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

7 |

211 |

|

240 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

241 |

|

270 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

8 |

241 |

|

270 |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

271 |

|

300 |

|

0 |

0 |

3 |

9 |

271 |

|

300 |

As you can see, the first set of blocks has a value of 300, so if we have the number , its factors according to position are . Or, if we have the number , its factors according to position are . If we do not have a specific number, we can write the number in its range: , meaning 901 to 930.

In each cycle of a block, it increases by one until it reaches nine. Then, in the next cycle, it jumps to the next position to the left, and so on.

All the numbers to the left of B must be multiplied by 300 because this gives the value of the blocks. Then, the value in the columns is added to the value of the blocks to get the final number. In this manner, all the numbers in the set of natural numbers could be factors of B.

So, every number has three parts:

- 1st. part

The first wheel system has 30, which together form the second wheel of 300 digits, running through its ten basic structures. Here, the columns are clearly visible. Using the columns, we can identify any prime or composite odd or even number.

- 2nd. part

The identity number is entirely math-neutral but provides information on where a specific number could be found. This part is a bridge that connects each of the ten basic structures one by one with the blocks.

- 3rd. part

The biggest part: The block of 300, whose value can be multiplied by natural numbers.

Taking into account that , we can write any number as follows:

. Breaking down the numbers, we get:

Breaking down the numbers, we get:

converting the number .

Breaking down the numbers, we get:

Breaking down the numbers, we get:

So, generalizing the expression, it takes the following form with all its parts.

Where

Example

This means that the values of each part are as follows:

the numbers of blocks.

the number of basic structures.

the number of column and the place of position of the number.

The total value of the seven structures plus the seventeen in the column.

3.2.3. Conversion to the Decimal System and Vice Versa

Any number in the Long Count structural form can be converted to a decimal number. In turn, any number in decimal form can be converted to the Long Count structural form. This is useful when determining if a number is prime or finding the distance between two known prime numbers. The Long Count provides all the necessary information to determine the exact position of each prime number. The following examples illustrate each case.

Convert to a Long Count structure.

Follow this step-by-step procedure:

First divide , where n is the factor of B, and , r and are the residues.

Second divide where i is the number of basic structure and is the number of column.

Match each term to the corresponding long count number.

If you see 1 the number 151 is founded exactly in the fifth basic structure and the first column.

Convert

to a Long Count structure.

Convert

to a Long Count structure.

Convert

to a Long Count structure.

Convert

to a Long Count structure.

There is a special case in which dividing by 30 may result in a remainder of 0, meaning the column is number 30. Therefore, subtract one from the quotient and add 30 to the remainder to make the operation equivalent. Record the result as .

Convert

to a Long Count structure.

So, if

, then

To convert any number in Long Count notation to the decimal system, multiply the coefficient of

B by 300 and add

C value as explained below. Usually, an expression of a Long Count number must be written in the following form:

as explained previously. Here

, so if we have a number as

Now, let’s calculate the conversion.

Therefore Our number is in the position of a prime number. But is it? We can investigate if we want to.

Now, we have a number as Now, let’s calculate the conversion.

Therefore

Now, we have a number as Now, let’s calculate the conversion.

Therefore

Now, we have a number as Now, let’s calculate the conversion.

Therefore

Converting between systems is important for understanding the various ways we can express a number. This allows us to use it in the field that interests us at the time. The way the decimal system is organized is much more interesting than we realize, so there is still much to discover.

3.3. Prime Gaps that Are Also Prime

For many, the spaces between prime numbers are all even numbers, except for 2 and 3 which is equal to one. See

https://oeis.org/A001223, (

The On-line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences) but under the architecture of this hypothesis, analyzing the basic structure and everything that it implies in its extension to the entire numerical line, if we strictly consider the real physical separation that exists between two successive primes, we find a succession of odd number of spaces, some of which also yield a quantity of spaces that correspond to a prime number. This has its root cause in the first, after seven, because between 2 and 3 there is no space and between 3 and

and 7 there is a space of one, the same is true for all twin prime numbers, and the second basic structure, which we use to complete the pattern, where all the spaces are quantities that represent prime numbers. This quality extends to all successive structures randomly as the products of prime numbers greater than 7 are interspersed.

For a long time, I’ve heard that prime numbers are the building blocks of the number system, and I’ve wondered just as many times how or where they fit into such a structure. This is probably only part of what we can see, because I think we still have much to discover when it comes to seeing the complete structure.

In some ways, the fact that the spaces between prime numbers alternately also represent prime quantities may be the key to not leaving such large gaps in the numerical wall being built.

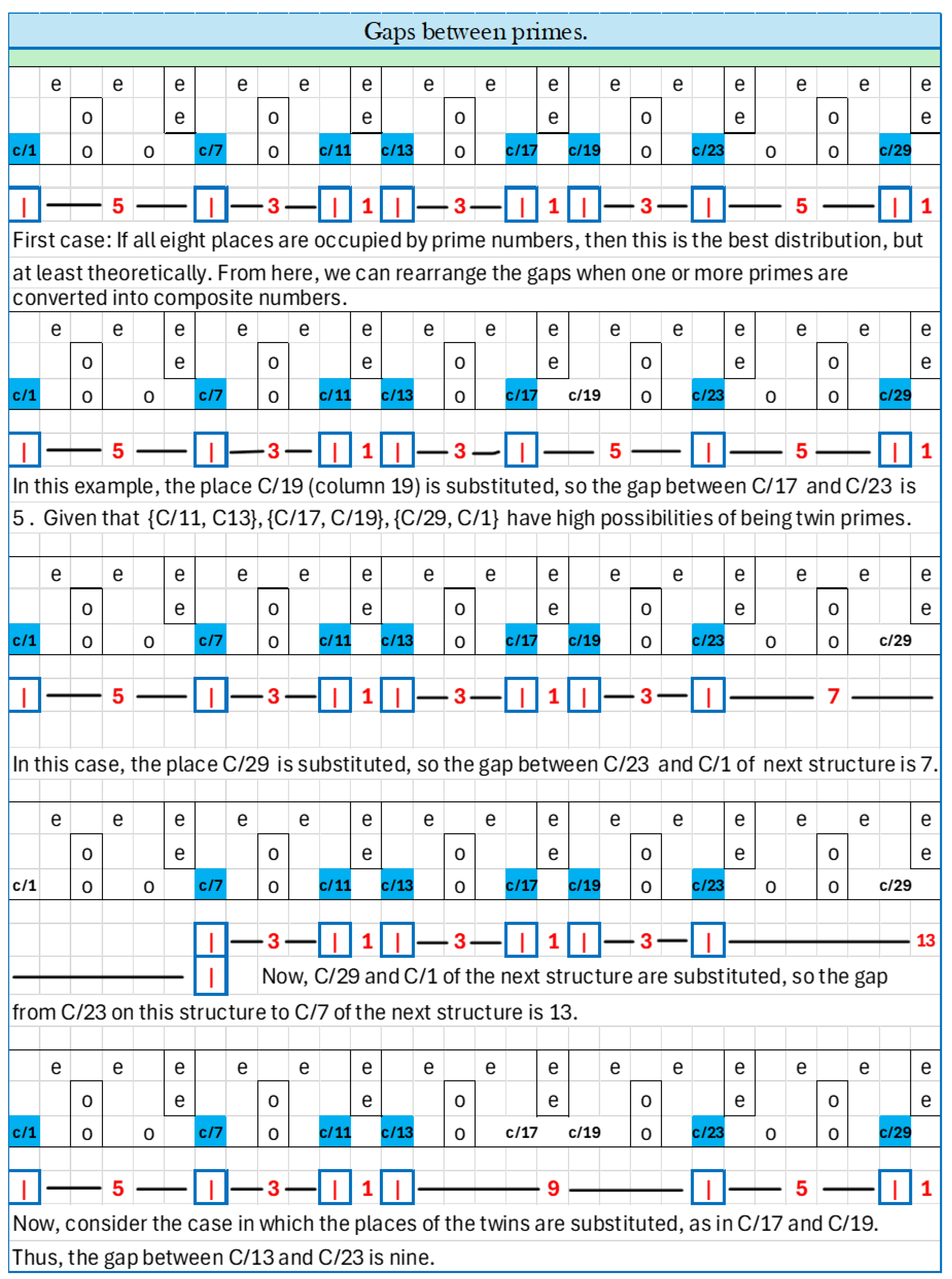

In any basic structure of 30 digits, the general arrangement of the space between consecutive primes is determined by the pattern of the eight places that would be occupied by them. Suppose there are all eight primes.

Table 5.

This table shows the general distribution of gaps, excluding the and 5, which are only present in the first structure. is the position of primes, .

Table 5.

This table shows the general distribution of gaps, excluding the and 5, which are only present in the first structure. is the position of primes, .

| Gaps between primes |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

|

g |

|

| 1 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

3 |

11 |

11 |

1 |

13 |

13 |

3 |

17 |

17 |

1 |

19 |

19 |

3 |

23 |

23 |

5 |

29 |

|

g |

|

| 29 |

1 |

1 |

We will analyze the primality property of spaces by applying formula

1 and

2 to calculate the separation between two prime numbers. This study is merely an introduction to the mechanics of determining this behavior of prime numbers, but finding a function that describes the probability of finding or not finding a prime in a given position will require a more in-depth analysis.

There will surely be many cases along the number line of natural numbers in which, in some basic 30-digit structures, these possible conditions are met, which is why we study them in the following examples, considering the most common possibilities. Obviously, there will be cases that contain a larger gap between primes and may even leave half or more of a block without prime numbers, but we will study these special cases in more detail and will probably be able to determine what the largest separation could be or at least how it could be calculated.

Find the gap between to , to , to , to , to and to

Find the gap between to , to , to , to , and to

Find the gap between to , to , to , and to

Find the gap between to , to and to

Find the gap between to and to

The final relationship within any fundamental structure is between two possible prime numbers, which could be positioned in the and columns.

Find the gap between to

To expand the gaps between prime numbers beyond the elementary structure, we use formula two

2 or

3. However, the case that interests us is when the primality property of the spaces is preserved. Therefore, we will only analyze this case in its elementary form. Then, we will move on to cases of greater interest that may arise, since this is just a new field of study concerning the primality properties of the gaps between primes.

I estimate that several primes, in their mutual relationship, manage to maintain and extend the property of primality among their gaps in some way.

Let’s calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. Suppose there are no primes between them. Here

Calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. There are no primes between them. Here

Let’s calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. There are no primes between them.

Let’s calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. Suppose there are no primes between them. Here

Let’s calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. Suppose there are no primes between them. Here

Let’s calculate the gap from

to

to the next

. Suppose there are no primes between them. Here

If we have two consecutive primes, and , their gap is 23.

Now, if we have two consecutive primes,

and

, their gap is 59.

3

If we have two consecutive primes, and , their gap is 59. This relationship is very interesting because it alternates with the positions of odd numbers generated by prime number products. These products must occupy one or more of the original prime number positions, which increases the distance between prime numbers. At what rate does this growth occur? The relationship between prime and odd numbers is certainly very close, as the odd numbers are the product of successive multiplications between the prime numbers .

If we can understand and establish this relationship, where they discover each other, then we may be able to understand the mechanics of their distribution. This will be one of the major tasks of the next research project.

4. The DNA of the Decimal Number System

Another fascinating contribution of the structure of the numerical system proposed here is the formation of a symbiotic relationship between each and every number, odd and even together, which in their strict order form a three-axis helix. We can denote these three helices however we wish; for the moment, I have mislabeled them as DNA, but later we will find a name appropriate to their true meaning.

As we have stated in previous paragraphs, the number 3 constitutes the backbone of the decimal system because it connects the even number axis with the odd number axis, like vertebrae that maintain the cohesion of the system throughout its entire construction. However, by constituting the numerical structure in a system of three helical axes, it brings us other, even deeper contributions that we will analyze with great interest.

For now, we will present them as a set of questions, waiting for answers.

The figure above shows a hypothetical three-axis helical chain arrangement, in which a strictly ordered sequence of numbers develops. Red dots indicate prime numbers and blue dots indicate composite numbers that are even or odd. Prime number 3 is highlighted in green and 2 in violet. The composite odd numbers that occupy one of the eight possible prime number spaces are highlighted in black.

The chain could be extended to infinity, but that wouldn’t be interesting because it wouldn’t have any meaning or importance in our daily lives.

Apparently, none of us are interested in infinity because no one knows if it is practical for our perception of reality or daily events or if it offers anything. It’s better to think in parts since we are all part of a whole. Even though we are subtly the same totality of the whole in its true essence and can’t see the totality, we can at least try to understand the totality of the parts.

So, what if our number sequence, with its three helical axes, doesn’t actually reach infinity in a linear, straight line? What if it’s just a part of something larger? What if it’s only the part that gives solidity to an object, phenomenon, variable, thought, intelligent process, or numerical field? What if we are part of it? It’s better to be part of something in order to constitute infinity because otherwise, how can one be infinite? How else could we be sure that infinite prime numbers exist? Therefore, the most important parts are the parts themselves. In this way, we can conjecture that our infinite chain is made up of parts—of many parts—of infinite parts, and that each part has a beginning and an end. If everything has a beginning and an end, then the end is the same point as the beginning. However, this is not a strict sense, but rather a sense of cycles. For something to begin, something must end, transform, redirect itself, rediscover itself, rethink itself, resurface, or die. In this sense, dying means being renewed in the evolution of its incipient part, continuing the cycle until reaching the end again.

What if our three-axis helical chain could connect to another similar chain in a different position? This would be facilitated by occupying an odd composite number in one of the eight places designated for prime numbers and replacing it with a prime number from the new chain. What if such a chain extends perpendicular to the first chain? What if another identical chain were positioned in a different place in the opposite direction? What if other chains were added to the new chains in different positions and directions? What would happen? What if other chains were positioned vertically, up and down, above the original chain? What if horizontal chains were positioned above the vertical chains in both directions?

The result would be the most beautiful three-dimensional mesh of our numerical system.

5. Conclusion

This hypothesis will forever remain just that—a hypothesis—because it is impossible to know the total arrangement of the distribution of gaps between prime numbers, given their uncountable and indescribable size. So, what is the point of studying them? Do they have any practical applications? Do they provide solutions to our everyday problems? There is absolutely no point, no application, no solution, nothing. From this perspective, there is nothing, certainly nothing if we only see them as unattainable numbers. However, if we learn to study them closely to the extent that our intellectual capacity and physical abilities allow, we will undoubtedly be ecstatic about their immense wonder and understand all of their fascinating secrets.

The marvelous thing about prime numbers and the numerical structure that contains them, giving it consistency and form, is studying them to the extent that we can count them. If we can’t count something, there’s no point in continuing because it will have no meaning.

First, it is important to focus on what we can understand intellectually; this must be our first step. However, if we go beyond that, it is surely because we are trying to understand. This is very important to our civilization because there is much knowledge we need to discover.

To begin, let’s start with the most basic question: What is a number? Assuming we know, can we then understand what it means to be a prime number? Do these questions make sense? Yes, they certainly do. It is fundamental to our civilization to know and understand what it means to be a number. Why? And for what purpose? The answer comes from our primitive ancestors, but the more holistic concept originates from Greek culture. This concept was greatly influenced by the exceptional contributions of Pythagoras of Samos (570-490 BCE) [13] and his brotherhood: the Pythagorean school, which considered the universe and numbers to be one and the same.

The influence of the Pythagorean school has spanned our entire intellectual evolution as humans, from the Hellenistic era, [6] with Plato, Aristotle, Phylolaus, Archytas of Tarentum, and Nicomachus, who influenced Euclid’s work on The Elements, to the Roman era with Apollonius of Tyana, and the Middle Ages and Renaissance with Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Gottfried Leibniz, see

https://www.britannica.com/science/Pythagoreanism and many others, who have followed the philosophical and mathematical thought of the Pythagorean school.

In our modern age of artificial intelligence, an era proliferating in so many extraordinary inventions, but in the face of our precarious philosophy filled with conflicts, the philosophy and mathematical foundations of Pythagoras and his school should not go unnoticed.

In an era of massive data processing centers, where every living and non-living being is inscribed. An era where quantum processors can uncover the secrets of every living, thinking individual’s thoughts. Where the secrets of the atom have been discovered and manipulated to detonate in a chain reaction capable of destroying the entire structure of our planet.

If, despite all this scientific progress, we still don’t understand what information is, then our supposed intelligence isn’t really intelligence. What, then, is our philosophy of things? How can we understand the importance of numbers, measurements, and proportions? [4] Our entire reality is numbers. There is no physical thing that has a number that makes it unique; even something intangible to our senses has a specific number.

Therefore, numbers generate the information that defines the characteristics and properties of objects, manifesting them in their entirety, regardless of whether our perception of an object is accurate. Everything is information, and the value of information is determined by its number. There is no other way to understand anything. Everything vibrates; everything emits or reflects light. Even in extreme darkness, a small amount of light is emitted, but a large quantity is absorbed. Therefore, everything is in a state of oscillation, vibration, or movement.

All objects, whether particles, cells, bodies, or galaxies, are subject to internal and external forces. These forces are equal and opposite, and vary in magnitude and direction. If the internal forces are balanced, the object remains in equilibrium. If the forces are unbalanced, the object becomes dynamic. In both cases, the object responds in a way that keeps it active in the face of external forces. Such results allow the object to interact with other objects, balancing the forces and activating the phenomena of action and reaction. Every force and action has an intrinsic number, whether we perceive it or not. All of this can be understood through numbers because numbers identify it.

In an environment, a number emits and absorbs numbers in a mutual exchange of information.

What is useful in our daily lives is what is close to us. I assure you that the infinite, the nothing, the unthinkable, the incomprehensible, and the totality of everything are closer to us than we can imagine.

The decimal system is extremely malleable. It adapts to any structural form, ranging from subtle, imperceptible simulations, such as the Bridge Theory, to densely solid mathematical bodies. I have developed some of these forms, which I will present in future works.

There is still much to be explained, so this article only covers a small part of what we need to know. I hope we can delve deeper into the close relationship between numbers and our perception of reality as a civilization, regardless of what it means for each individual or for the simulation it may mean for some, because the numbers are present even in a simulation.

This hypothesis is an open invitation for anyone interested in delving deeper into and developing a function that describes the relationship between prime numbers and their gaps. This function will surely provide a clearer view of the mechanics of prime number distribution along the number line. Here are the basics to help us see the problem of such arrangement from a different point of view. This is just the beginning.

References

- Johan Ludvig Heiberg Euclid, Sr T. L. Heath. The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, volume II. University Press, 1908.

- Carl Friedrich Gauss. Disquisitiones arithmeticae auctore d. Carolo Friderico Gauss. in commissis apud Gerh. Fleischer, jun., 1801.

- Ben Green and Terence Tao. The primes contain arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions. Annals of mathematics, pages 481–547, 2008.

- Detlev Hoffmann. Pythagoras numbers of fields. Journal of the American Mathematical Society, 12(3):839–848, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Adrien Marie Legendre. Essai sur la théorie des nombres. Courcier, 1808.

- Dominic J O’meara. Pythagoras revived: Mathematics and philosophy in late antiquity. Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Hector Pasten. The abc conjecture, arithmetic progressions of primes and squarefree values of polynomials at prime arguments. International Journal of Number Theory, 11(03):721–737, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mihai Prunescu and Joseph M Shunia. On arithmetic terms expressing the prime-counting function and the n-th prime. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14594, 2024.

- Bernhard Riemann. On the number of prime numbers less than a given quantity.(ueber die anzahl der primzahlen unter einer gegebenen grösse.). Monatsberichte der Berliner Akademie, 1859.

- Bernhard Riemann. Sobre el número de números primos menores que una magnitud dada. Monatsber. Akad. Berlin, pages 671–680, 1859.

- Bernhard Riemann. Ueber die anzahl der primzahlen unter einer gegebenen grosse. Ges. Math. Werke und Wissenschaftlicher Nachlaß, 2(145-155):2, 1859.

- Yitang Zhang. Bounded gaps between primes. Annals of Mathematics, pages 1121–1174, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Leonid Zhmud. Pythagoras as a mathematician. Historia Mathematica, 16(3):249–268, 1989. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Keyword: Basic structure, Block, Column, Helical structure, Prime gap. |

| 2 |

This fascinating property and its relationship to nothingness form the basis for defining what a number is. I describe this in another investigation. |

| 3 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).