Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Theoretical Reformulations

2.1. PPE Reformulations

2.2. Corrective Pressure Boundary Condition

III. Compatibility, Well-Posedness, and Stability Analysis

IV. Numerical Examples

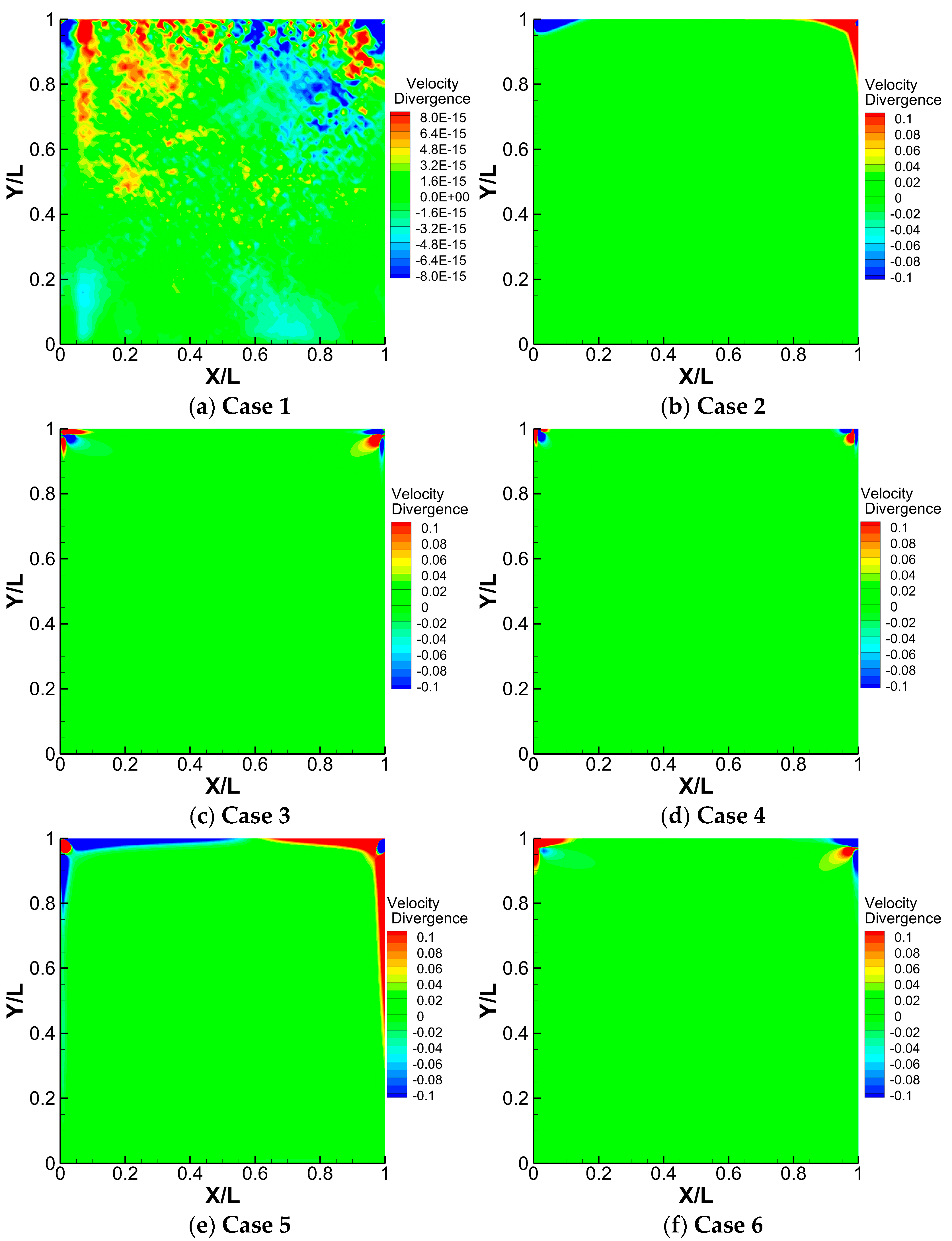

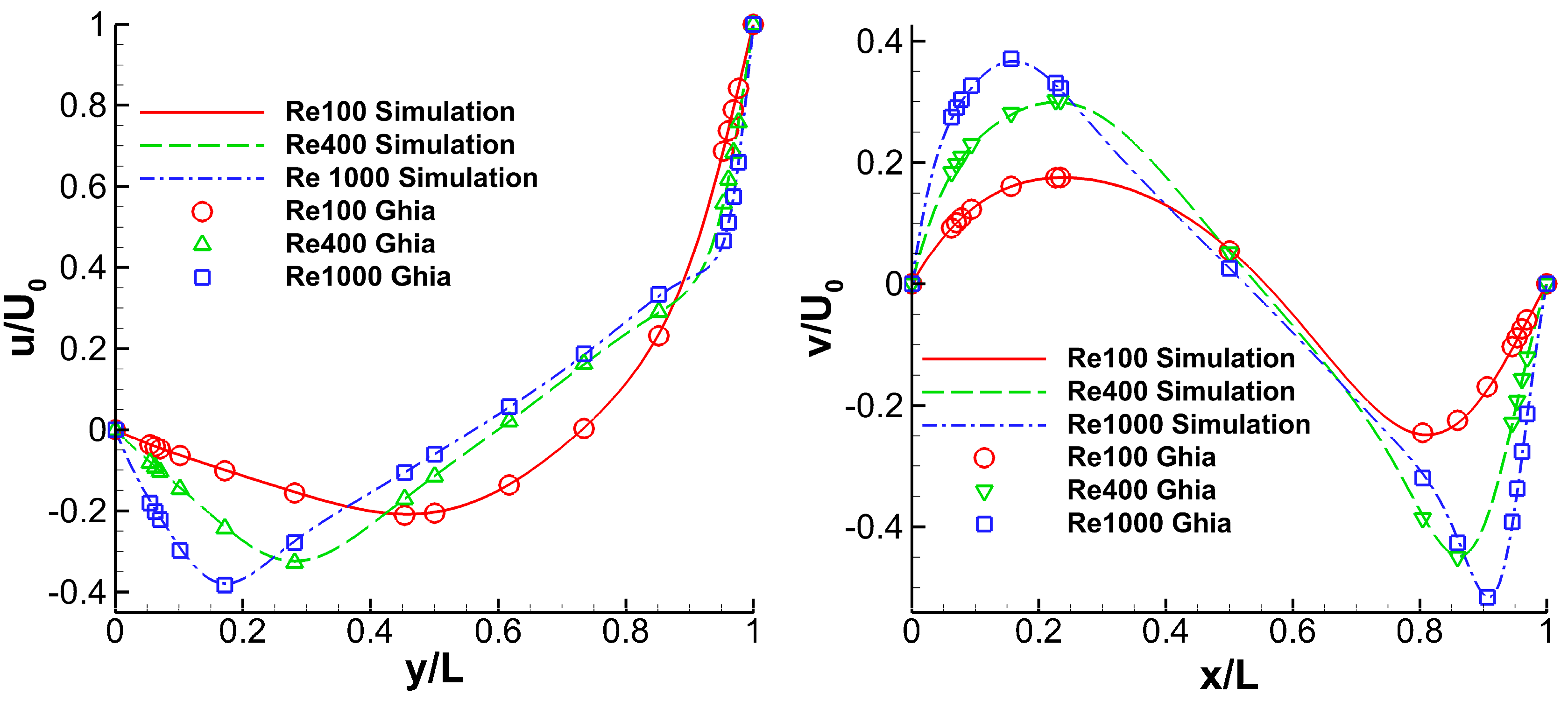

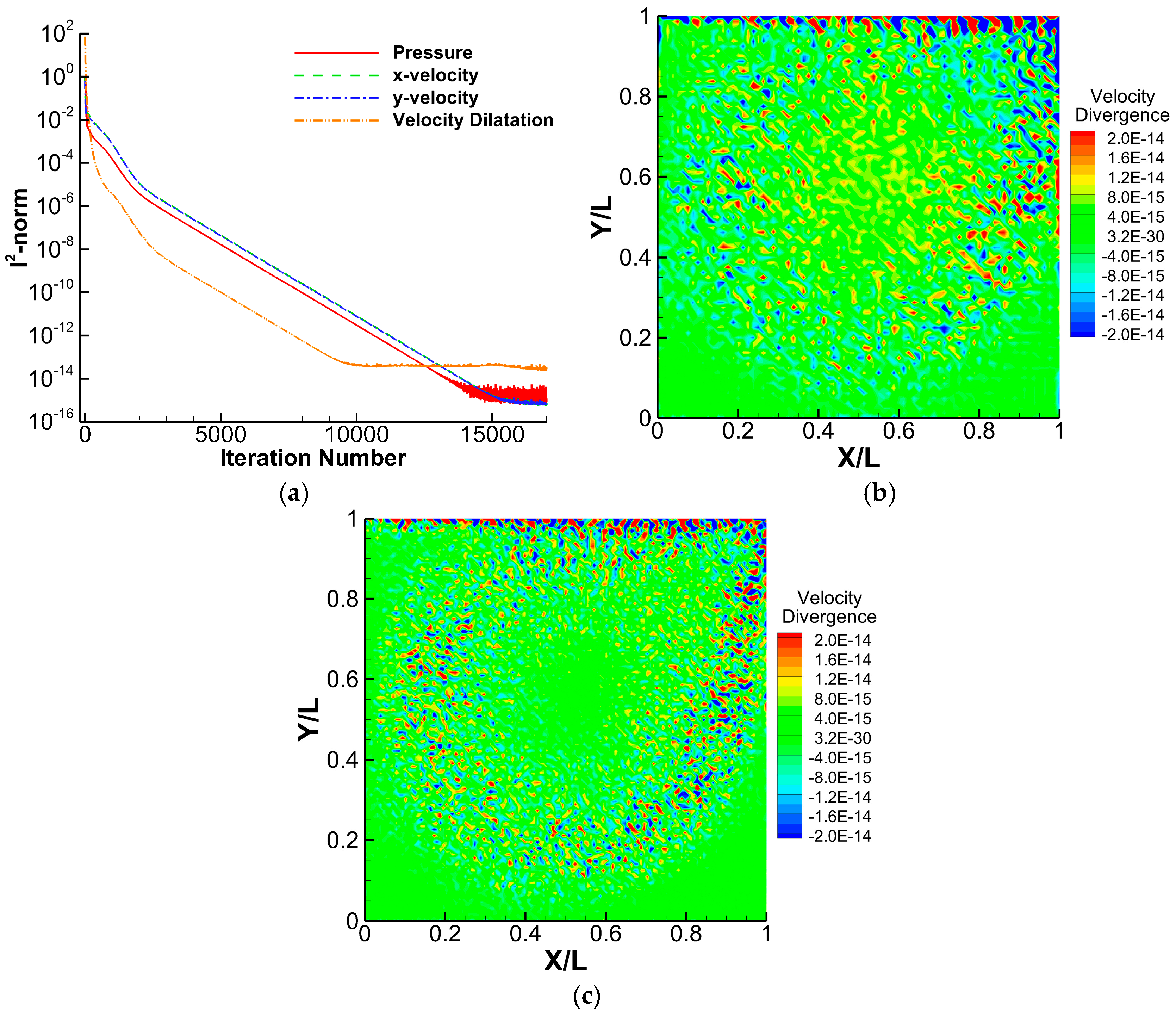

4.1. Lid-Driven Cavity Flow

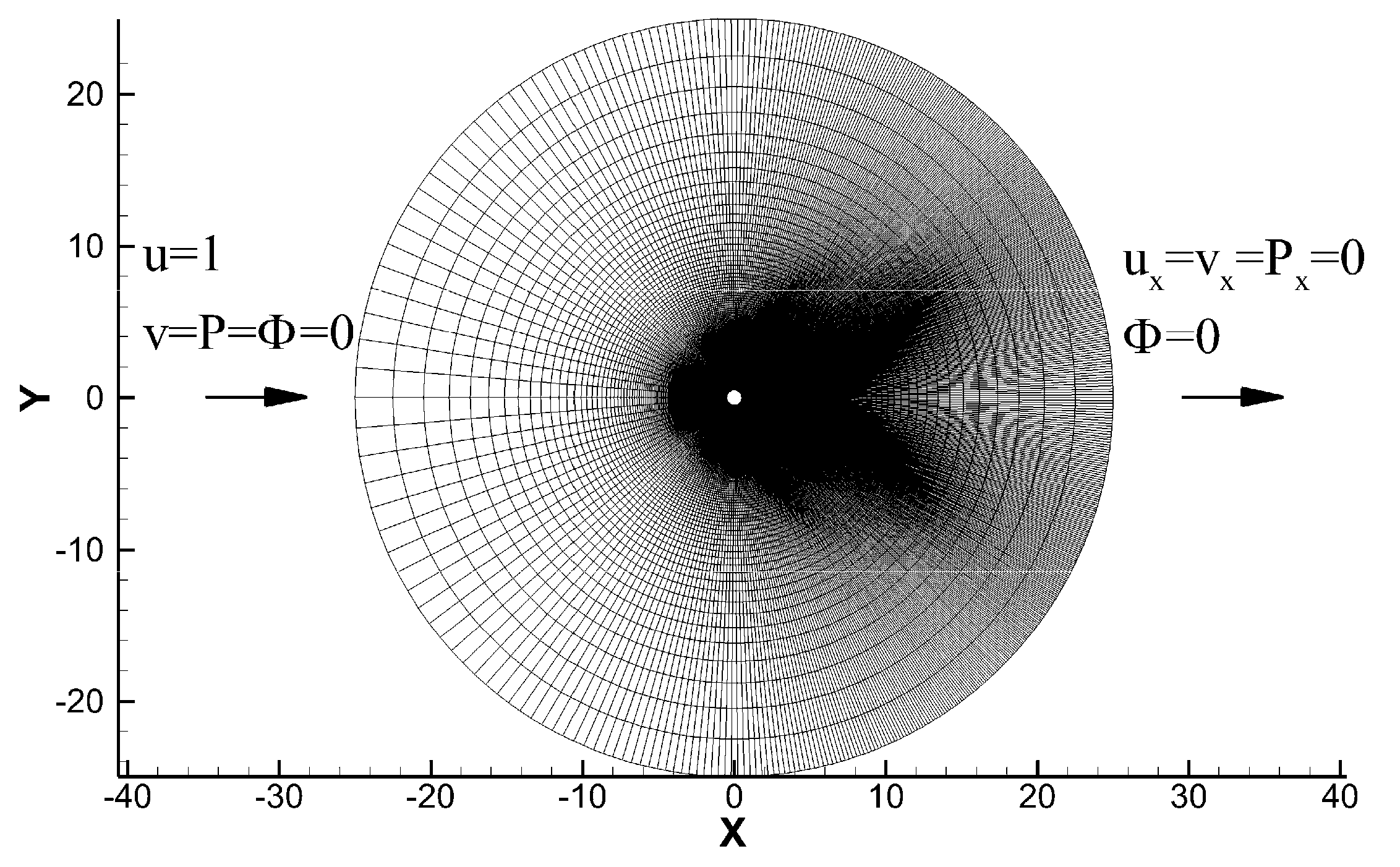

4.2. Flow Passing a Circular Cylinder

V. Conclusions

Declaration of Interest Statement

References

- Gresho, P.M.; Sani, R.L. On pressure boundary conditions for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1987, 7, 1111–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, R.L.; Shen, J.; Pironneau, O.; Gresho, P.M. Pressure boundary condition for the time-dependent incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2005, 50, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, N. Stability of Pressure Boundary Conditions for Stokes and Navier–Stokes Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2001, 172, 40–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, R.R.; Seibold, B.; Shirokoff, D.; Zhou, D. High-order finite element methods for a pressure Poisson equation reformulation of the Navier–Stokes equations with electric boundary conditions. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempfer, D. On Boundary Conditions for Incompressible Navier-Stokes Problems. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2006, 59, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempfer, D. Two remarks on a paper by Saniet al. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2008, 56, 1961–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, W.D. A Fourth-Order Accurate Method for the Incompressible Navier-Stokes Equations on Overlapping Grids. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 113, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, W.D.; Kreiss, H.-O.; Reyna, L.G. A fourth-order-accurate difference approximation for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. Comput. Fluids 1994, 23, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strikwerda, J.C. Finite Difference Methods for the Stokes and Navier–Stokes Equations. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1984, 5, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Dreyer, J. Dirichlet and Neumann boundary conditions for the pressure poisson equation of incompressible flow. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1988, 8, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H.; Liu, J.-G. Finite Difference Schemes for Incompressible Flow Based on Local Pressure Boundary Conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 2002, 180, 120–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfigli, G. Numerical solution of the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations with explicit integration of the pressure term. PAMM 2007, 7, 4100019–4100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokoff, D.; Rosales, R. An efficient method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations on irregular domains with no-slip boundary conditions, high order up to the boundary. J. Comput. Phys. 2011, 230, 8619–8646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreman, A. The projection method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations: The pressure near a no-slip wall. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 263, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, F.; Abdallah, S. The discrete continuity equation in primitive variable solutions of incompressible flow. J. Comput. Phys. 1991, 95, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiser, L.; Schumann, U. Treatment of Incompressibility and Boundary Conditions in 3-D Numerical Spectral Simulations of Plane Channel Flows. Proceedings of the Third GAMM-Conference on Numerical Methods in Fluid Mechanics. Notes on Numerical Fluid Mechanics 1980, 2, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. GePUP: Generic Projection and Unconstrained PPE for Fourth-Order Solutions of the Incompressible Navier–Stokes Equations with No-Slip Boundary Conditions. J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 67, 1134–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, F.H.; Welch, J.E. Numerical Calculation of Time-Dependent Viscous Incompressible Flow of Fluid with Free Surface. Phys. Fluids 1965, 8, 2182–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orszag, S.A.; Israeli, M.; Deville, M.O. Boundary conditions for incompressible flows. J. Sci. Comput. 1986, 1, 75–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y. An improved pressure gradient method for viscous incompressible flows. Comput. Fluids 2024, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, J.; Mattsson, K.; Swanson, C. Boundary conditions for a divergence free velocity–pressure formulation of the Navier–Stokes equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2007, 225, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Kwak, D.; Kaul, U. On the accuracy of the pseudocompressibility method in solving the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. Appl. Math. Model. 1987, 11, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S. Numerical Methods for Partial Differential Equations: Finite Difference and Finite Volume Methods; Academic Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Svärd, M.; Nordström, J. Review of summation-by-parts schemes for initial–boundary-value problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 268, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.H.; Gottlieb, D.; Abarbanel, S. Time-Stable Boundary Conditions for Finite-Difference Schemes Solving Hyperbolic Systems: Methodology and Application to High-Order Compact Schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 111, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefethen, L.N.; Embree, M. Spectra and Pseudospectra: The Behavior of Nonnormal Matrices and Operators; Princeton University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, B.; Kreiss, H.-O.; Sundström, A. Stability theory of difference approximations for mixed initial boundary value problems. II. Math. Comput. 1972, 26, 649–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, W.; Liu, J.-G. Projection Method II: Godunov–Ryabenki Analysis. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1996, 33, 1597–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cai, M. Normal mode analysis of 3D incompressible viscous fluid flow models. Appl. Anal. 2019, 100, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, U.; Ghia, K.; Shin, C. High-Re solutions for incompressible flow using the Navier-Stokes equations and a multigrid method. J. Comput. Phys. 1982, 48, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutanceau, M.; Bouard, R. Experimental determination of the main features of the viscous flow in the wake of a circular cylinder in uniform translation. Part 1. Steady flow. J. Fluid Mech. 1977, 79, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | PPE | Neumann Boundary Condition | Max stable ∆t |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proposed PPE (7a) | Proposed BC (10) | 0.56 |

| 2 | Proposed PPE (7a) | Conventional BC (2a) | 0.09 |

| 3 | Conventional PPE (6) | Conventional BC (2a) | 0.09 |

| 4 | Conventional PPE (6) | Curl-Curl BC (2b) | 0.23 |

| 5 | Conventional PPE (6) | Homogeneous BC (1) | 0.76 |

| 6 | Conventional PPE (6) | Proposed BC (10) | 0.17 |

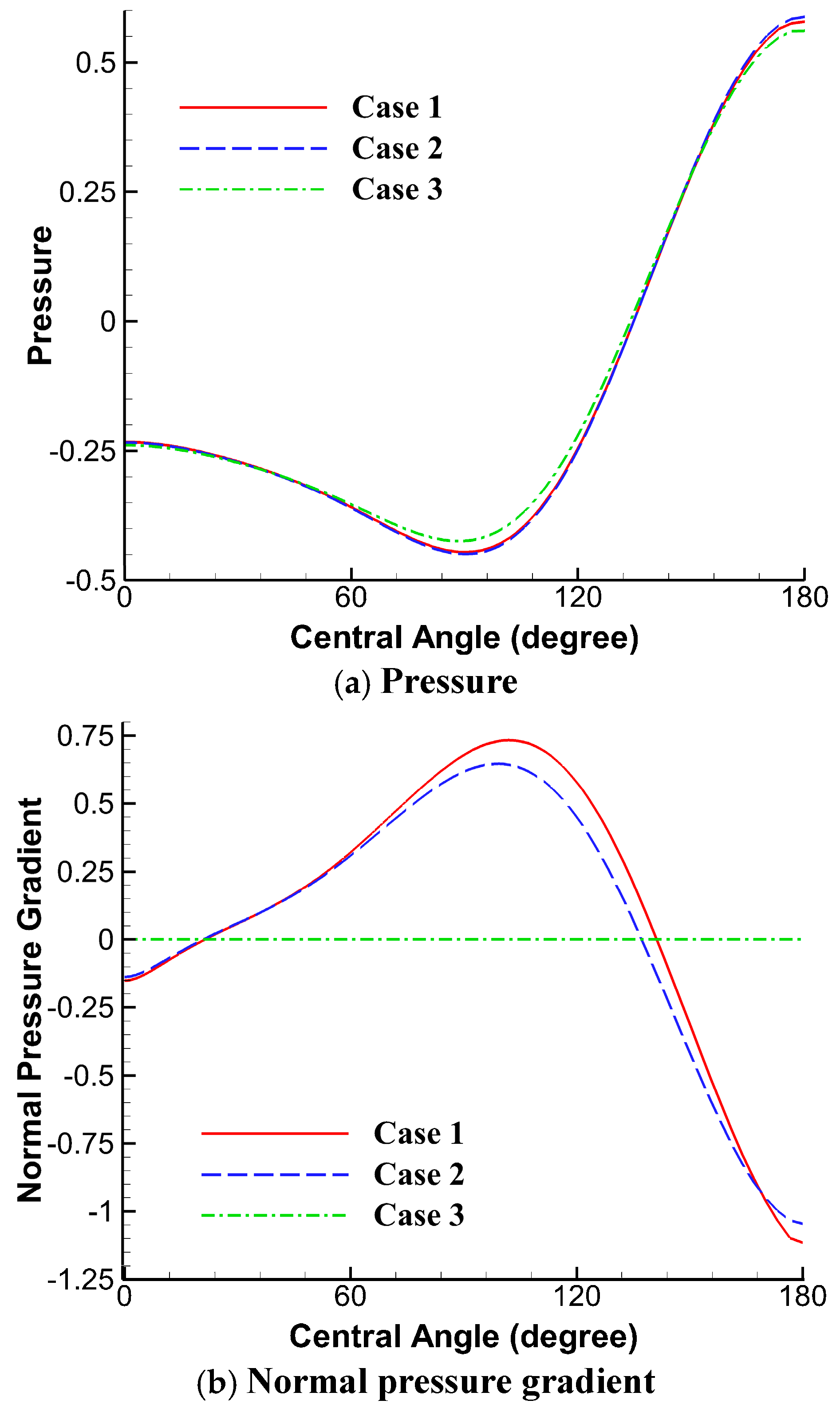

| Case | PPE | Neumann Boundary Condition | Separation Angle |

Reattachment Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proposed PPE (7a) | Proposed BC ((10) and (11a)) | 52.8o | 2.21 |

| 2 | Conventional PPE (6) | Conventional BC (2a) | 52.8o | 2.24 |

| 3 | Conventional PPE (6) | Homogeneous BC (1) | 52.8o | 2.31 |

| Experiments by Coutanceau and Bouard [32] | 53.5o | 2.13 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).