1. Introduction

The prevailing computational approach to solving viscous incompressible flows employs a pressure Poisson equation (PPE), which plays the role of continuity and offers an efficient means to solve for pressure and velocity either in a coupled manner or separately. Research endeavors have been dedicated to enhancing the boundary condition for PPE to ensure a divergence-free velocity field, particularly in the presence of solid walls. Unfortunately, no recognized outcome has been gained so far. For many commercial or in-house flow solvers, the PPE is not accurately solved for wall-bounded flows, and their solutions are only ostensibly correct. Because they are not divergence-free upon close examination, particularly in the vicinity of solid walls, where the Neumann boundary condition is employed but not correctly prescribed. The degraded solutions implicate that many important near-wall flow features, such as the boundary layer stratifications, turbulence structures, flow separations, and corner eddies, may not be precisely predicted. Therefore, Peyret and Taylor [

1] describe the pressure boundary condition specification as a “primary difficulty,” Ferziger [

2] addresses the problem of posing proper pressure boundary conditions as an “open question,” and Colonius [

3] calls the pressure handling a complex situation that has led to a long-standing debate.

In most practices, the homogeneous Neumann boundary condition, which is derived from the boundary layer theory, is adopted as a convenient approximation for solid wall boundaries.

Despite being simple and numerically very stable, the accuracy of (1) is confined to scenarios where the local Reynolds number is high. When the normal pressure gradient becomes significant, (1) tends to induce a numerical boundary layer in the near-wall region, corrupting the local velocity field and undermining the flow prediction. Gresho and Sani [

4] have provided a numerical example showing that the application of (1) will lead to inaccurate numerical results.

Another Neumann boundary condition based on the momentum equation is also frequently prescribed in the form of

It has very limited stability with an allowable time step much smaller than what the von Neumann analysis indicates. Gresho and Sani [

4] asserted that (2a) is theoretically consistent with the momentum equation and sufficiently valid for solving the PPE, as long as the continuity is enforced at the boundary. (2a) is often discretized using ghost points outside of the boundary, where such ghost points are obtained from the continuity relation▽

·u = 0. Alternatively, the so-called curl-curl boundary condition [

5] (also referred to as the electric boundary condition [

6]) is adopted in some research to take account of the tangential velocity component, which is less affected in accuracy by the mesh resolution than the normal component [

4]. This boundary condition is analytically identical to (2a), but it incorporates a normal derivative of the velocity divergence. It is expressed as

Regardless of whether ▽·

u is set to zero, (2b) exhibits enhanced numerical stability compared with (2a). Under most circumstances, (2a) or (2b) is still unable to yield a divergence-free solution even with continuity enforced at the boundary. Rempfer [8, 9], Henshaw [10, 11], and Strikwerda [

12] contended that (2) is underdetermined, as it provides no additional information beyond what is already inherent in the interior flow field. Given that no compelling explanations have been put forward to resolve these discrepancies and no consensus has been reached within the research community, the proper specification of the pressure boundary condition becomes a controversial subject [4, 7, 8, 9].

Focusing on divergence-free solutions with wall boundaries, many follow-up studies have been reported in the literature. These remedies include converting the Neumann boundary condition to the Dirichlet boundary condition [

13], enforcing explicit continuity at the boundaries [

14], incorporating damping terms [

11], prescribed functions [

15], supplementary constraints [

16], and stabilizing terms [

17] to the PPE, as well as proposals of new Neumann boundary conditions [

7]. Some of them claimed their methods yield divergence-free solutions. However, their validation cases only presented domain-averaged quantities of the velocity divergence, which are large for coarse grids and tend to decrease to certain nontrivial levels as the mesh is refined. Therefore, these claims are inaccurate. Certain researchers attributed the nontrivial velocity divergence to discretization errors and time increment [

18]. This reasoning is questionable because the velocity divergence represents a quantitative relationship between velocity components rather than a primitive variable. A zero velocity divergence up to machine precision should be attainable as in the artificial incompressibility method, irrespective of the mesh fineness. By circumventing the Neumann boundary condition, the influence matrix technique developed by Kleiser and Schumann [

19] achieves a degree of success. By solving an integral problem for the pressure based on Green’s function in the context of spectral methods, it establishes a linear relation between the pressure and the velocity divergence at the boundary, and enables the determination of the boundary value of the pressure (up to an arbitrary constant). Nevertheless, this method is complex to implement for general problems and has not been widely adopted. The open question for a divergence-free solution with a solid wall boundary remains unresolved.

In this paper, we challenge this problem from a new perspective. Theoretically, the pressure is an auxiliary function or a Lagrange multiplier to allow the velocity field to satisfy the continuity constraint. Sani

et al. [

7] have realized that mathematically solving the incompressible flow does not need a pressure boundary condition, though they haven’t provided a viable solution. But solving a PPE requires a boundary closure. This gives rise to a fundamental contradiction between the theoretical principles and numerical implementations. Many previous studies have overlooked this issue, and that is why their treatments will not fix the non-divergence-free problem. Accordingly, we argue that those viewpoints on (2) being underdetermined are wrong. On the contrary, setting a pressure boundary condition like (1) and (2) makes the system overdetermined. Equations being over-constrained or ill-posed is the reason behind the non-divergence-free problem. To resolve this contradiction, our strategy is to set up a diminishing Neumann boundary condition. It first facilitates the numerical computation of the PPE and then gradually fades away to make the system well-posed. To realize this conception, we will reformulate the PPE and boundary condition and establish such a mechanism with them.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The new PPE and Neumann pressure boundary condition are derived in Section II. They are examined for compatibility, well-posedness, and stability in Section III. Numerical tests are carried out to validate the proposed method, and comparative studies are performed against existing numerics in Section IV, proving the effectiveness and superiority of the new formulations. Summary and conclusion are given in Section V.

2. Theoretical Formulations

A. PPE for Corrective Pressure

In the study of viscous incompressible flows, people have developed two basic forms of the pressure Poisson equation (PPE): the conventional PPE and the corrective PPE. The conventional form of PPE is derived straightforwardly from the momentum equation, sometimes with certain additional terms or functions for improvement. Its elliptic nature determines that the pressure field is a unique diffusive function of the velocity field of the same moment, independent of the flow’s time history [

20]. The corrective PPE was first proposed with the well-known SIMPLE method [

21]. It solves for the pressure correction rather than the pressure in a guess-and-correction manner by connecting pressure fields of the divergent and solenoidal velocity field. The corrective PPE is also elliptic in nature, though it cannot be directly applied to solve for a time-accurate pressure field. A key difference from the conventional PPE is that the source term in the corrective PPE will progressively drop to zero when the flow converges, so will the pressure update. This feature provides a foundation to incorporate a diminishing Neumann boundary condition.

Since the corrective PPE used in the SIMPLE method does not account for the convection and viscous effects and only works for segregated solvers, we will reformulate the corrective PPE in a complete form. The momentum equation for viscous incompressible flows in conservation form is

in which the velocity

u = (

u(x, y, z), v(x, y, z), w(x, y, z)),

ν being the kinematic viscosity and

f the body force per unit mass acting on the fluid. Taking the divergence of (3) with the velocity dilatation rate

we can obtain (5) without assuming Ф = 0.

With nonzero Ф, (5) can be considered a PPE of the velocity field, which is not converged and solenoidal. When the divergence-free condition is satisfied, we should have Ф = 0 and ∂Ф/∂

t = 0 throughout the domain, and (5) becomes

(6) is the so-called standard PPE documented in the literature and can be considered the PPE for the solenoidal velocity field. Eqs. (5) and (6) represent two distinct flow fields in the computation with no sequential connection in the flow field evolution. But the common terms in (5) and (6) suggest a PPE for the corrective pressure to be solved by guess-and-correction iterations.

With unity density, (7a) can be simplified with the pressure correction as

Since |Ф| << 1 typically holds after some computations, the nonlinear terms and viscous terms in (7b) are then small in magnitude. Eq. (7b) retaining only the temporal term, can be further simplified as

This approximates the corrective PPE used in the well-known SIMPLE method, in which zero velocity divergence is assumed at the next iteration and Ф represents the velocity dilatation of the intermediate velocity field. Therefore, the theoretical soundness of (7b) is partially validated by the proven success of the SIMPLE algorithm.

The viscous term in (7b) conserves the velocity diffusion. Though it produces negligible difference in the solutions, it can boost numerical stability and permit larger pseudo time steps in the computation. And it can be extended to the SIMPLE series method and the projection methods to improve numerical stability. The Ф convective term in (7b) is necessary for convection-dominated flows when this PPE is directly coupled with the momentum equations. For this reason, (7c) can only be used separately from the momentum equation as in the SIMPLE algorithm, due to its lack of the Ф convection term required for mass transport. The temporal Ф term in (7b) is indispensable and can be approximated by

In standard PPE practice since its introduction by Harlow and Welch [

22], Ф

n+1 is set to zero to enforce continuity, while Ф

n is retained as nonzero to maintain numerical stability. When additional Ф terms are involved in (7b), our experience shows that three approaches are viable for handling the temporal Ф terms in (8): retaining both terms, removing both, or retaining only Ф

n+1. Notably, removing both terms leads to slow convergence with occasional instability, whereas retaining only Ф

n+1 yields the fastest convergence. And the diffusion term can be evaluated at either time level

n or

n+1, depending on the computational needs.

Comparing (5), (6), and (7), the source term in (5) or (6) keeps being non-zero and evolving in the computation, rendering a complex coupling with the varying Neumann pressure boundary condition if it is not homogeneous. In (7), the source term involves Ф terms only, and it will become zero when the solution converges, enhancing the stability of the computation. (7) also eliminates the need to calculate the divergence of the body force

f. The influence of

f on pressure is instead accounted for in the momentum equation calculations. The iteration of (7) establishes a mechanism that drives the Ф field towards zero during the pressure evolution. Once Ф converges to a trivial value, (7) becomes mathematically equivalent to the continuity equation. This is another advantage over the conventional PPE (5) and (6). The use of the variable Ф also avoids the direct coupling between the pressure and the velocity, and moderates the pressure updating through its spatial distribution, transport, and diffusion. A similar technique was employed in the pressure gradient method study [

23] to achieve divergence-free solutions without the need for specifying pressure gradient boundary conditions.

B. Neumann Boundary Condition for Corrective Pressure

As discussed in Section I, directly applying a fixed Neumann boundary condition, such as Eq. (2), will not yield a divergence-free solution. A dynamic and decaying Neumann boundary condition is needed to couple with the corrective PPE and satisfy the well-posedness requirement. Orszag

et al. [

24] have once proposed such a Neumann boundary condition for corrective pressure in a form similar to (10) for high-order temporal accuracy. But their iterative scheme is designed only to remove certain numerical instability and features an undetermined iterative parameter. Following the methodology used in deducing (7), we will derive the corresponding Neumann boundary condition from the momentum equation. The pressure gradient expression from (3) with all Ф terms retained is

(9a) can be interpreted as the Neumann pressure boundary condition for the divergent flow field and Ф≠0. When Ф=0, the above equation corresponds to the converged and solenoidal flow field, taking the form:

By eliminating their common terms, (9a) and (9b) constitute a Neumann boundary condition for the corrective pressure, solvable by guess-and-correction iterations.

It is evident that this boundary constraint will diminish as Ф gets close to zero, making the system well-posed. Compared with the boundary conditions (1) and (2), (10) involves only 1st-order derivatives, incorporates the tangential velocity effects through the Ф term, and exhibits equal simplicity in expression. (10) also accounts for the influence of the wall normal velocity via the unФ term. With respect to the numerical compatibility, we have found that this boundary condition (10) alone will not work effectively without coupling with the corrective PPE (7), as will be shown in Section IV. For implementations, the normal derivatives of P can utilize one-sided spatial discretization schemes of any high order. This new pressure boundary condition can also be promoted to the SIMPLE family to achieve divergence-free solutions and to the artificial compressibility method.

Since the calculation of (7) and (10) needs Ф values at the boundaries, the boundary condition for Ф is equally important. The boundary Ф specification must be numerically consistent with the interior Ф calculation to make the Ф field continuous and smooth. For wall-bounded flows, setting Ф directly to zero at wall boundaries skips the non-solenoidal evolution process and may fail to yield a divergence-free solution. A Rubin boundary condition for Ф has been proposed in [

25] using the energy method. For stationary solid walls, it is equivalent to setting

∂Ф

/∂n = 0. It is not compatible with (10), because

∂Ф

/∂n = 0 implies a constant

∂P/∂n in (10) from its initial value in the iteration. Therefore, we adopt the Dirichlet boundary condition for Ф on solid walls and compute it with (4) and one-sided difference scheme.

On a staggered mesh, the computation of Ф should be straightforward. However, for collocated mesh, the pressure and Ф field solutions have been observed in numerical experiments with some spurious oscillations near certain solid walls. They stem from the numerical discontinuities between the interior and the boundary Ф values, introduced by the artificial viscosity term used to supplement the central scheme for interior Ф computations. When the magnitude of Ф diminishes, any non-decaying numerical errors become significant, contaminating the domain and causing solution wiggles. As we know, an upwind or one-sided scheme can be decomposed into one symmetrical part and one antisymmetric part. Conversely, the antisymmetric central scheme augmented with a symmetric artificial viscosity term is equivalent to an upwind or one-sided scheme. For illustration, consider a finite difference central scheme (

CS) with uniform grid spacing ∆

x, defined as

and a typical four-order artificial viscosity term (AVT) as

As shown in (12), a 3rd-order forward/backward one-sided scheme (used for the left/right boundary) can be expressed as a linear combination of the above CS and AVT terms.

The backward one-sided scheme (12b) for boundaries with ending coordinate indices equals CS + AVT. This is the same combination used in the domain interior to compute ∂u/∂x for Ф. In contrast, the forward one-sided scheme (12a) for boundaries with starting coordinate indices conflicts with CS + AVT, being responsible for the oscillatory Ф field near these boundaries. Though the actual schemes (including compact schemes) applied in implementations may involve terms of different orders and a scaling coefficient, the numerical inconsistency between the boundary and the interior discretization persists.

One possible method to handle this difficulty is gradually removing the artificial dissipation term with an exponentially decaying coefficient as performed by Rogers

et al. [

26]. But the decaying parameter requires some case-by-case careful tuning, making this method not very feasible. We have found a more effective technique to resolve this inconsistency. As pointed out by Mazumder [

27], in a physical problem, when a boundary derivative (e.g.,

∂un/∂n) is not a prescribed value but computed with one-sided schemes, additional numerical error other than the truncation error will arise. And the solution of this derivative will be discontinuous from the interior to the boundaries, because the governing equation is not satisfied at the boundary. Mazumder has provided a treatment: enforce the governing equation in the one-sided scheme for 1st-order derivatives by incorporating a 2nd-order derivative, which may be already known from the physical problem. For one-dimensional implementation with uniform grid spacing

∆x, a 2

nd-order derivative can be embedded into the one-sided difference scheme for the 1st-order

u derivative by cancelling the 3

rd-order derivatives in the following two Taylor series expansions:

so that

In computing

∂un/∂n for velocity dilatation (4), the 2nd-order term

∂2un/∂n2 is accessible in the momentum equation in the form of (2) and can be replaced with (

∂P/∂n)/μ for a solid wall boundary. Therefore, Ф at the static wall boundary with the starting coordinate index is computed as

By replacing the

d²u/dx² term with the pressure gradient, (15a) establishes a new local coupling that improves numerical accuracy and convergence rate. Though (2) should not be used as a proper boundary condition to solve for the pressure, it is still a useful relation in this treatment. For finite volume implementations, in which the boundary conditions are applied on the cell faces rather than the cell centers,

∂un/∂n is computed differently. On a one-dimensional grid of equal cell spacing

∆x, Ф at the left (

W) wall boundary (starting coordinate index) is calculated as

with the centers of the boundary cell and the right cell next to it denoted as

O and

E.

Based on the above discussions, we choose to compute Ф with (15) at the boundaries of starting coordinate indices, while employing conventional one-sided schemes to calculate Ф at the solid wall boundaries of ending indices. The conventional one-sided schemes can be of any order relative to the central scheme for computing the interior Ф. With this implementation on collocated grids, the pressure and Ф fields will become smooth without any wiggles, helping minimize the Ф magnitude to nearly machine accuracy. Although (15) will turn out to be a 3rd-order one-sided scheme if the d²u/dx² term is substituted with a one-sided discretization, this 3rd-order scheme will not work as effectively as (15). And if we apply the correction procedure (15) correspondingly to the opposite one-sided scheme for wall boundaries of ending indices, the Ф solution will converge to a nontrivial value, because the correction disrupts the prior CS + AVT consistency.

For boundaries other than solid walls, such as an inflow with a static pressure value and a domain symmetry with zero pressure gradient, the theoretical requirement of pressure boundary condition absence is violated. In these cases, the calculation of the proposed PPE (7) should be restricted to the domain interior and solid wall boundaries. For inflow or outflow boundaries, Ф can be set to zero, assuming the far-upstream or far-downstream flows satisfying the continuity as in fully developed or undisturbed regions. This treatment maintains consistency with the iterative evolution of Φ toward zero in the domain interior.

C. Complete Formulations

For convenience, the complete formulations for numerical simulations with the proposed PPE and Neumann boundary condition are repeated and summarized as follows. The equations can be solved in a coupled or separated procedure.

3. Compatibility, Well-Posedness, and Stability Analysis

This section will examine the corrective PPE and Neumann boundary condition formulations proposed in the last section for specific theoretical validity and numerical stability prior to code implementations and computer testing. It is widely recognized that the pressure field is conservative, and a valid pressure solution must satisfy Gauss’s theorem within the domain or any subdomain as a compatibility or solvability requirement unless it is a finite element space.

For conventional PPE and pressure boundary condition specified by (2) and (6), the compatibility condition (16) can be readily proved based on their derivations from the momentum equations [

16]. For our proposed PPE (7) and pressure boundary condition (10), this relation is less evident due to their incorporation of the corrective pressure and Ф terms.

Proof Within a three-dimensional domain or subdomain Ω, the loop integral of the normal pressure gradient correction at the boundary can be expressed based on (10) as

Given that

∂Ф/∂n in (17) is continuous and differentiable, we can directly derive the following result from the divergence theorem:

Considering

unФ in (17) also being a vector and the definition ▽·

u = Ф, we have again from the divergence theorem that

Combining (17), (18) and (19), we obtain

Comparing with (7), we have arrived at

As

and

in the iterative process, we have

With a 1

st-order Euler’s backward time differencing assumption, the summing term in (22) is

When the initial value Ф0 is zero and the converged Фn equals zero, (23) will become zero. Therefore, the compatibility requirement for the pressure solution (16) holds for our proposed PPE and pressure boundary conditions provided the computation converges. □

The numerical stability and specific stable conditions are another concern for the proposed formulations. The existing stability analysis techniques applicable to general initial-boundary-value problems include the summation-by-parts (SBP) energy method [

28], simultaneous approximation term (SAT) method [

29], pseudospectra method [

30], and the normal mode analysis [

31]. In this study, the numerical well-posedness and stability are examined utilizing the normal mode analysis. This method is a generalization of the von Neumann stability analysis to account for the influence of nonperiodic boundary conditions. For simplicity, we study a two-dimensional Stokes problem in steady state. It has been proved in [

32] that the predictions from the normal mode analysis for the Stokes equations are also applicable to the full Navier-Stokes equations. The conventional pressure boundary conditions of (2a) and (2b) have been investigated via the normal mode analysis by Petersson [

5] and Zhang

et al. [

33] in semi-discrete or fully discrete form with different time schemes. For our proposed PPE and pressure boundary condition, we consider the semi-discrete form by discretizing the time term and leaving all the spatial terms continuous. The Stokes problem is defined by the equations and boundary conditions presented in (24), within a finite domain Ω with periodicity over (0, 2π) in

x-direction and solid wall boundaries at the two ends of [-1, 1] in

y-direction. Assuming a forward Euler scheme, we replace the iterative relation in the PPE (7b) and Neumann boundary condition (10) with a time derivative and a constant time step

∆t as in a pseudo-time marching procedure. The convective terms in (7b) are absent for the Stokes flow, and the insignificant viscous and nonlinear terms in (7b) are neglected to facilitate the analysis.

,

With a mesh of uniform grid spacing ∆

x = 2π/

N, we consider a discrete Fourier transform of a grid function

F (

x, y) as

where

i is the square root of -1. The wave numbers

ω = 0 ~

N-1 correspond to a complete set of eigenfunctions

eiωx within the discretized domain. We perform a Fourier transform of the solution in the

x-direction and make the ansatz for differential equations (24) in semi-discrete form as

By employing fully implicit momentum equations and an explicit expression for Ф, we can derive the eigenvalue problem (27) by neglecting the forcing term and assuming unity density. The Godunov-Ryabenkii condition states that the solution to the system (24) is unstable if the eigenvalue

κ of (27) exists and |

κ| > 1.

By substituting

, (27) without boundary conditions can be simplified as

Without having to solve for

u and

v, the admissible odd solutions for the pressure and Ф are

By substituting the above pressure and the Ф solutions into the pressure boundary condition (27e) at

y = ±1, we can obtain an explicit and real expression for

κ as

From (30), it can be readily verified that |κ| < 1/2 for any nonnegative wave number ω, which is defined by the discrete Fourier transform (25). This confirms that the proposed formulation is unconditionally stable and this problem is well-posed in the strong sense. A similar conclusion holds for the even solutions. In the above analysis, no u velocity specification is required at the wall boundary y = ±1. Therefore, this analysis also applies to slip or non-slip moving wall boundaries. This special benefit has not been found in prior normal mode analysis on incompressible flow equations [5, 32, 33].

For finite difference discretization formulations of (24), we define the central difference approximation of ∂

x and ∂

xx with Fourier transformation and a uniform mesh spacing

∆x:

(28 a ~ d) is then rewritten as

Similar to (29), the admissible odd solutions for the pressure and Ф are

in which

D = sin

(ω∆x/2)/∆x. By substituting (33) into the pressure boundary condition (27e), we can obtain

κ as

We have 0 ≤ κ < 1. The discretized formulation is also unconditionally stable.

4. Numerical Test Cases

In this section, the proposed PPE and Neumann boundary condition are validated with two-dimensional steady-state laminar flow problems. Eqs. (3), (4), and (7b) are solved simultaneously using the finite difference method. All convection and diffusion terms are discretized with second-order central schemes on collocated grids. Artificial viscosity is thus added for the pressure gradient, the velocity gradient terms, and the Ф transport terms. Marching with a pseudo-time, the time derivative is discretized by the backward Euler scheme. And the pressure field is regularized to a zero mean value after each iteration. No convergence acceleration technique is employed in order to preserve the solution details for better comparison. The flow domains are initialized with a uniform pressure and velocity field. However, we have found that initial velocity and pressure fields of random but moderate values, which make the initial flow field non-divergence-free, also yield satisfactory results. Because the computation can rapidly purge out the randomness in the computation.

A. Lid-Driven Cavity Flow

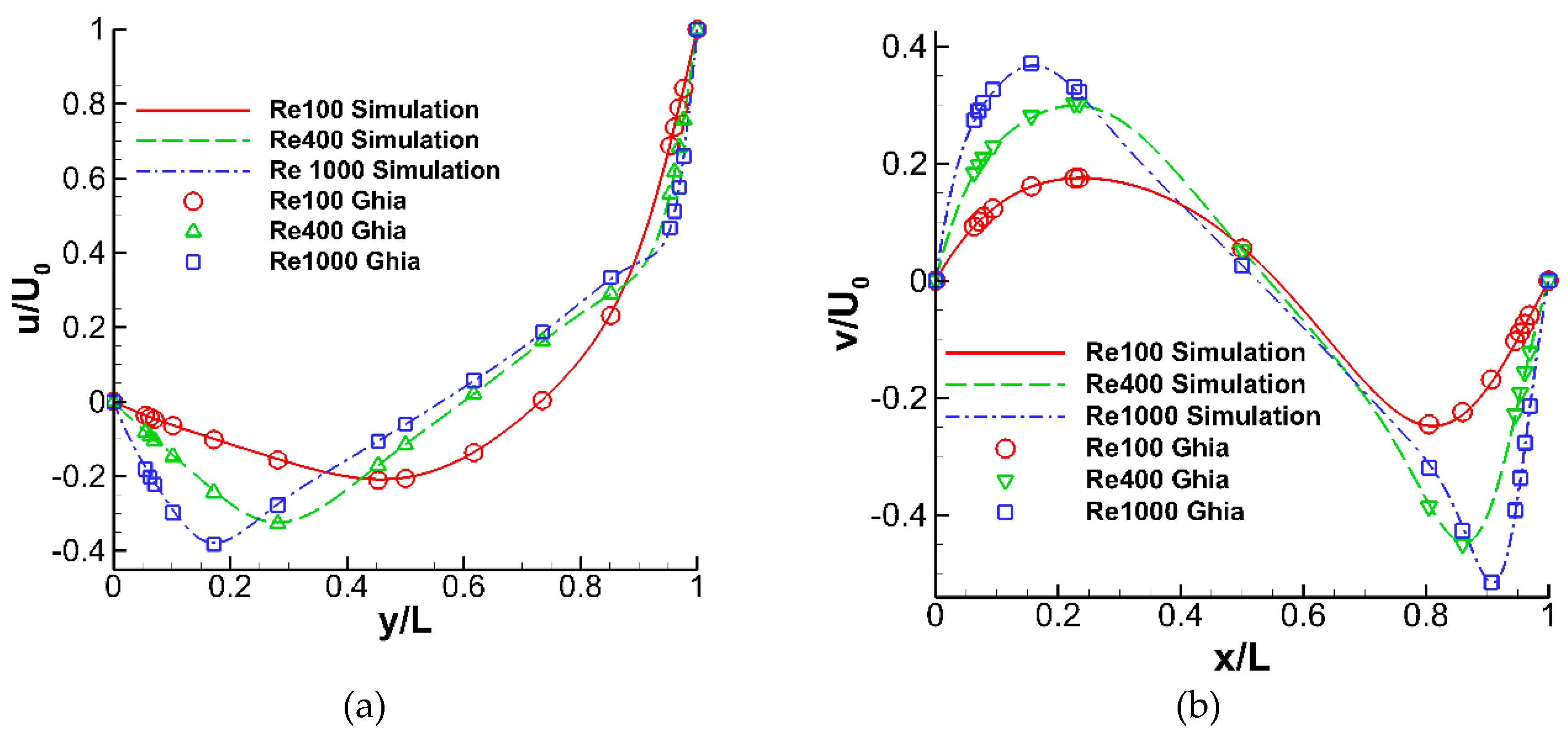

The first test case is the classic top-lid-driven cavity flow. This wall-bounded flow is simple in geometry but rich in flow features. The square domain consists of boundary conditions of all Neumann type for the pressure. It also characterizes numerical singularities at the two upper corners, which often pose difficulties for conventional PPE solutions. This problem is first modeled using our proposed formulations on a 129 × 129 mesh. The obtained centerline velocity profile results for different Reynolds numbers are plotted in

Figure 1 in contrast with the benchmark data of Ghia

et al. [

34], which are based on the vorticity-stream function method with divergence-free assurance. The two data sets show excellent agreement.

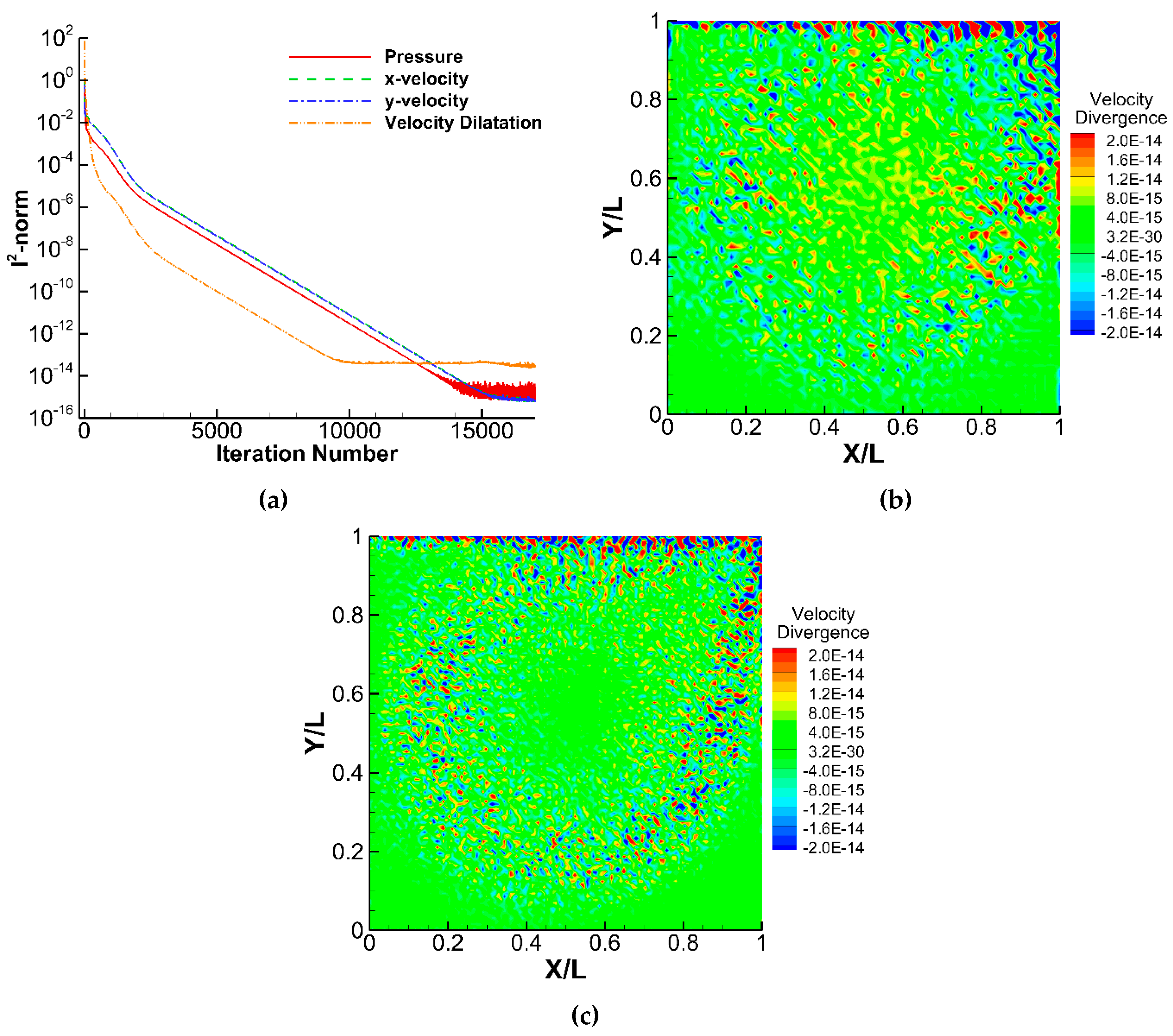

Figure 2(a) presents the convergence history for the case with

Re = 1000. Figs. 2(b) and 2(c) demonstrate the domain solutions of the velocity dilatation, confirming a genuinely divergence-free velocity field. The resolved magnitude level of Ф is independent of the grid spacing, and it is not affected by the corner singularity. Although the artificial viscosity term involved in computing the velocity dilatation (4) may be nontrivial in certain regions, this formulation’s capability is undoubted in driving the given Ф expression to near machine zero.

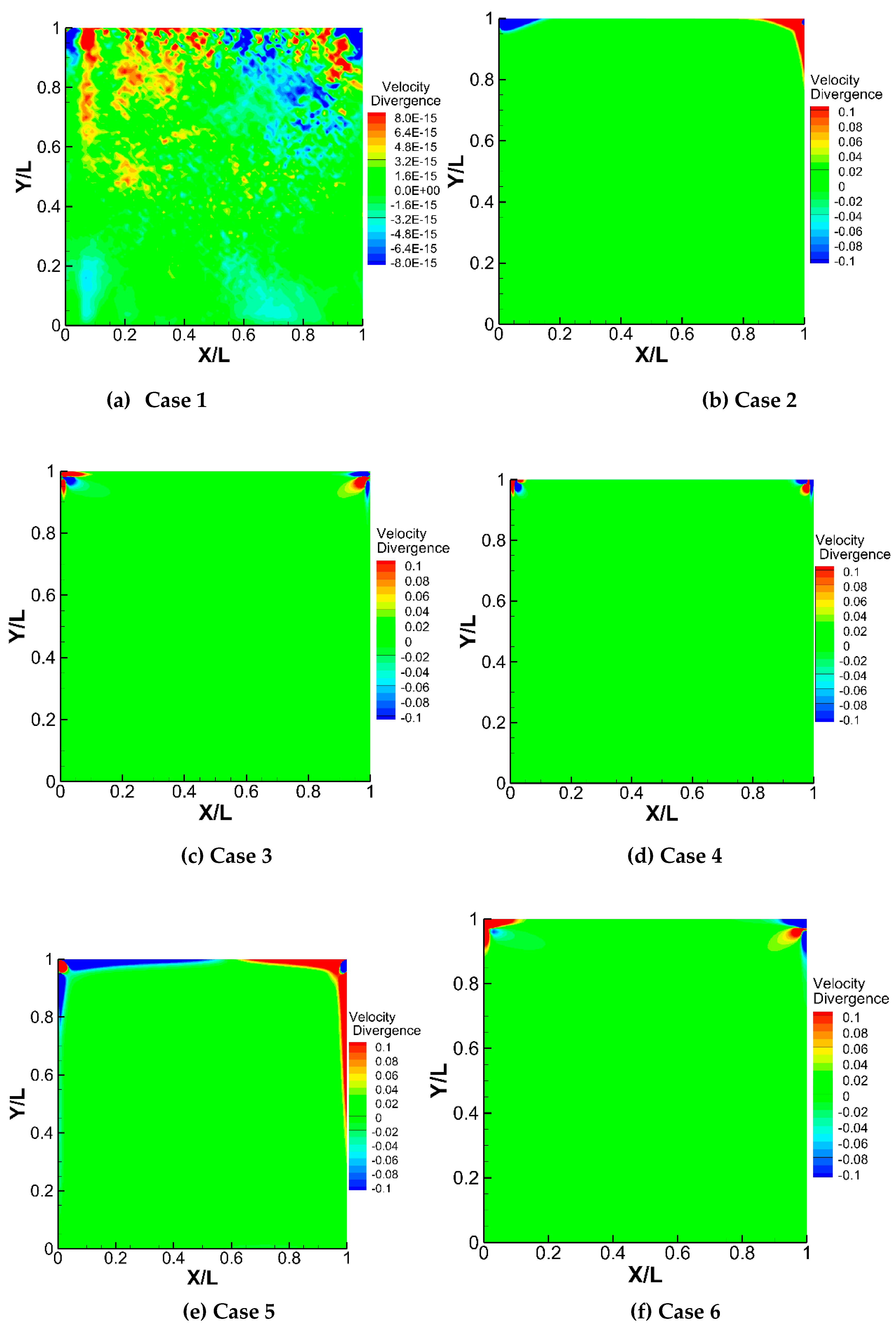

A comparative study in numerics is then performed with this cavity flow problem on a 101× 101 mesh.

Table 1 elaborates the case setup employing the PPE and pressure boundary conditions from the proposed method, previous methods, and their mixtures. We also examine the curl-curl (2b) and the homogeneous pressure boundary conditions (1) in this study. All cases utilize identical formulations except for the PPE and pressure boundary condition. For Cases 2 and 3, the discretization of (2a) includes external ghost points computed by applying the continuity equation at the boundary. For Case 4, the boundary vorticity is calculated for use in the curl-curl boundary condition (2b).

Table 1 also lists the maximum stable pseudo-time step sizes in serial computing for comparison, with equal underrelaxations in variable updating for each case. The well-converged velocity divergence solutions for Case 1~6 are presented in Figs. 3(a)~(f). Our proposed PPE and pressure boundary condition evidently outperform the others and represent the only combination capable of achieving divergence-free solutions (Case 1). The rest of the cases display magnitudes of velocity dilatation up to the level of ~10

2 near the two upper corners. These magnitudes exceed typical numerical errors and indicate poor solution quality under the influence of boundary singularities. To better visualize the magnitude differences, the contour range for Case 2 to 6 is restricted to -0.1 ~ 0.1. The conventional PPE (6) with the homogeneous pressure boundary condition (1) yields the poorest result, as it additionally produces numerical boundary layers adhering to the two side walls. We also find that our proposed boundary condition (10) alone will not generate divergence-free solutions with the conventional PPE (Case 6), nor will our proposed PPE perform effectively with the conventional boundary condition (2a) (Case 2). Therefore, we can determine that the boundary condition for corrective pressure is only adaptive to the corrective PPE.

From the pseudo-time step comparison in

Table 1, our proposed PPE and boundary condition (Case 1) demonstrate a significant advantage in stability over the conventional setups (Case 3 and Case 4), albeit Case 4 is also theoretically proven unconditionally stable [2-5]. For this problem, our new PPE functions adequately with only the linear terms in (7b), and its stability is considerably enhanced when more nonlinear terms are included. Without external ghost points from the continuity, Cases 2 and 3 will have even smaller allowable time steps. The homogeneous pressure boundary condition (Case 5) permits the largest time steps. This is attributed to its numerical simplicity, which enhances the diagonal dominance of the system matrix. For Cases 2~5, the pressure solutions are uniquely determined, though flawed. Based on the PDE theory, we conclude that their pressure boundary conditions ((1) and (2)) are enforced excessively, making the system ill-posed instead of being underdetermined as previously hypothesized. The homogeneous pressure boundary condition (Case 5) imposes the most rigid over-constraint and therefore renders the largest errors.

Figure 3.

Velocity divergence solutions with the problem setup prescribed in Table 1 for Re = 100 on a 101 x 101 uniform mesh.

Figure 3.

Velocity divergence solutions with the problem setup prescribed in Table 1 for Re = 100 on a 101 x 101 uniform mesh.

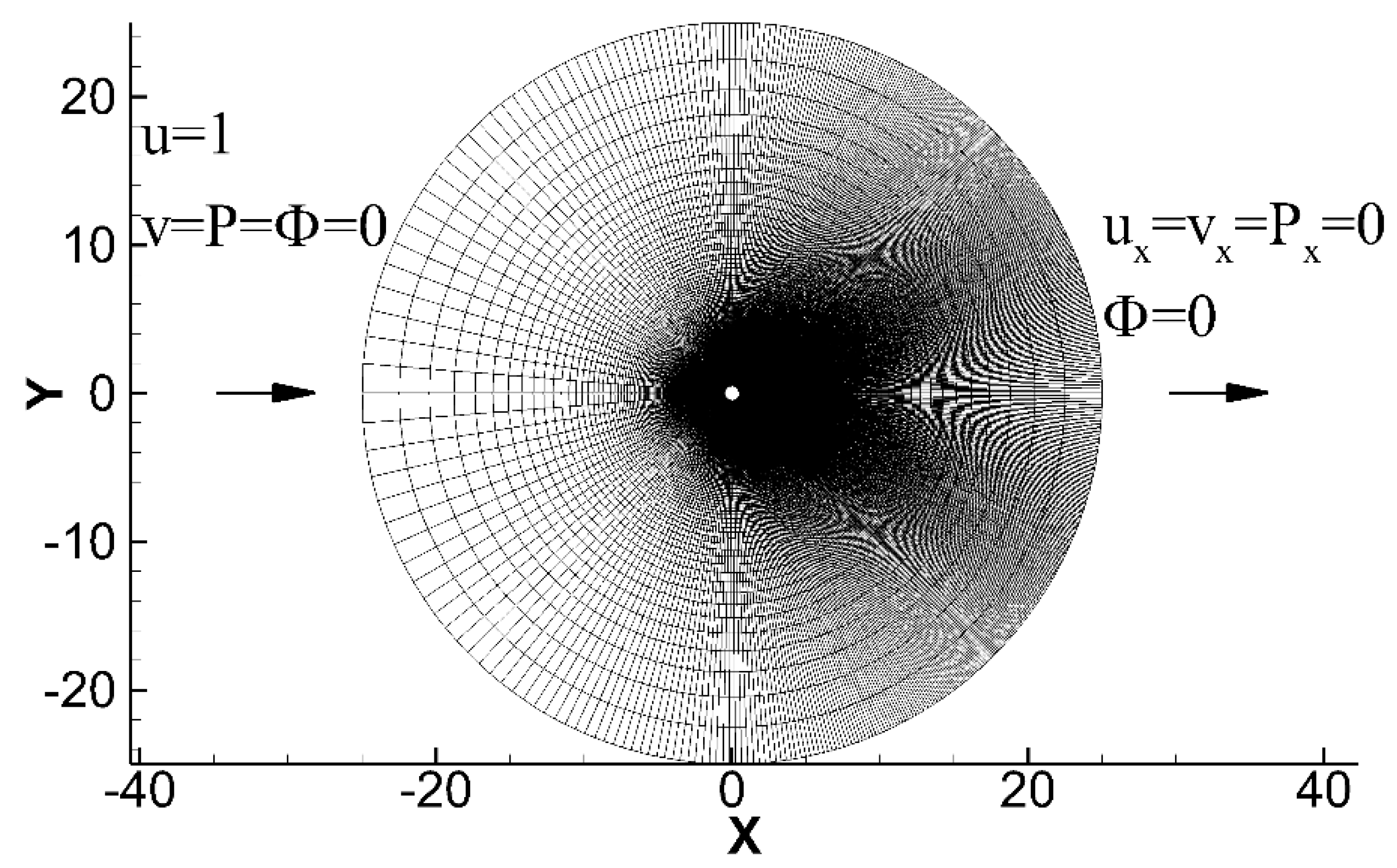

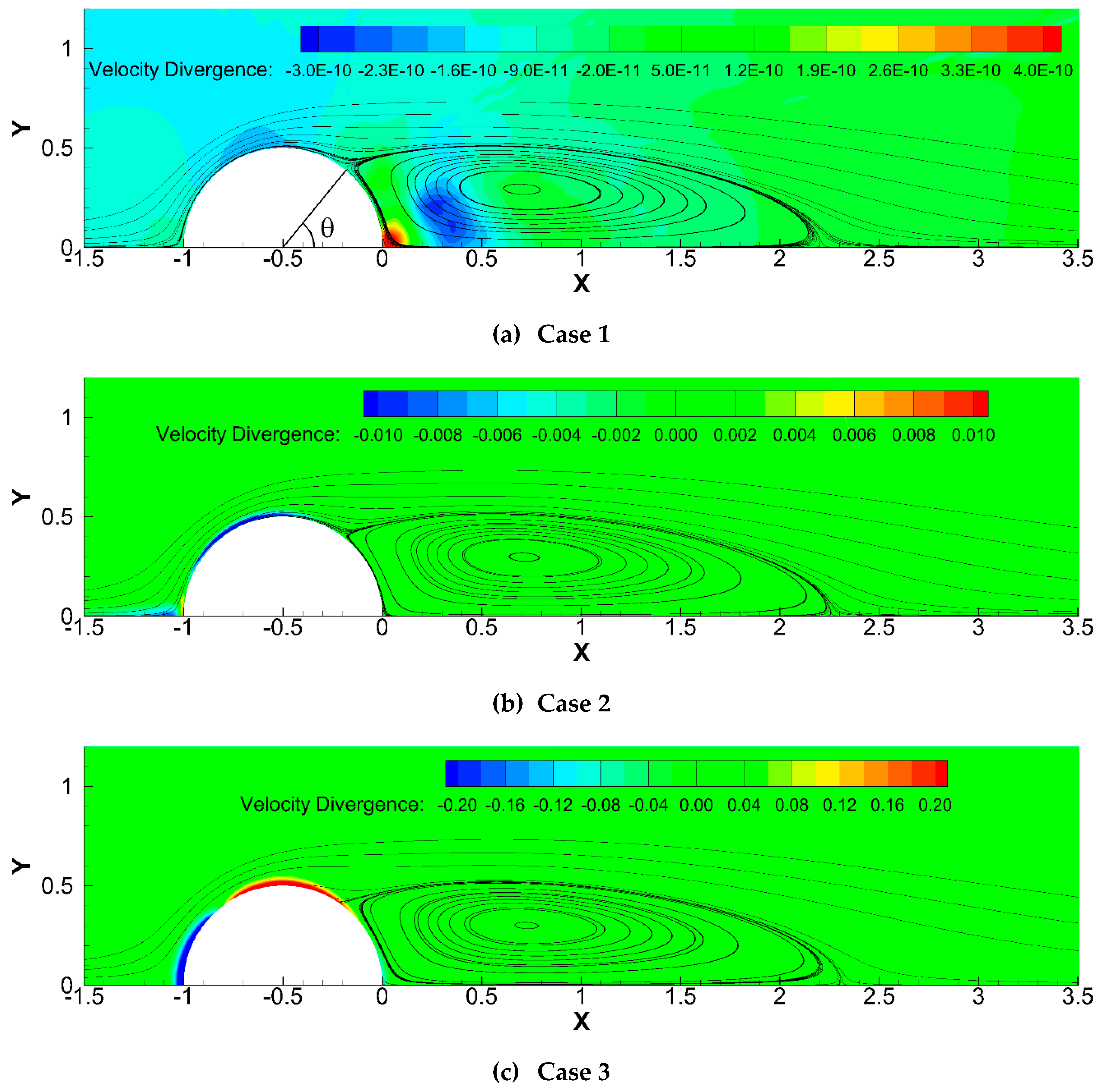

B. Flow Passing a Circular Cylinder

The second test case focuses on the uniform flow passing a circular cylinder. It is a fundamental external flow problem characterized by flow separation and wake formation. The accurate prediction of these flow features heavily relies on the velocity solution quality and the proper specification of the pressure boundary condition on the cylinder surface. This problem is investigated in steady-state condition at a Reynolds number of 40. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the cylinder diameter is set to unity, and the circular computational domain is designed with a radius 25 times the cylinder diameter to mitigate the adverse influence of the finite domain effects on flow predictions. The 541 × 301 structural mesh is clustered around the cylinder and refined in the wake region to better capture the flow details. The near wake region has a radial resolution of 0.01. And all intersecting mesh lines are arranged to be orthogonal to one another to reduce discretization errors. The external boundary condition configurations for each variable are also specified in

Figure 4. The left semicircle of the domain serves as the inflow boundary with given velocity, static pressure, and Ф. The right semicircle functions as the outflow boundary with the velocity and pressure values obtained by streamwise extrapolation from the domain interior.

As outlined in

Table 2, the simulations are carried out for comparative study using our proposed PPE/pressure boundary condition and the conventional formulations. All cases are run with identical iteration numbers and ensured sufficient convergence. The experimental measurements by Coutanceau and Bouard [

35] are available as baseline data for flow separation angle and reattachment distance. Solution flow fields from the three simulations are visualized in

Figure 5 with streamlines and velocity divergence contours. Our proposed PPE and boundary condition produce a high-level divergence-free solution (

Figure 5(a)). If more iterations are executed, the velocity divergence magnitude can be further reduced. For conventional PPE and boundary condition (

Figure 5(b)), the maximum velocity divergence reaches a level of 10

-2. And for conventional PPE with a homogeneous boundary condition (

Figure 5(c)), this peak magnitude increases to the level of 10

-1, concentrated round the cylinder surface.

Table 2 compares the separation angle (θ) and the reattachment distance measured from

x = 0 as defined in

Figure 5(a) for the three cases. The flow separation point on the cylinder surface and the wake reattachment point are identified by streamline bifurcations. Our proposed formulation predicts the reattachment distance closest to the experimental measurement, whereas the conventional PPE with homogeneous pressure boundary condition results in the largest deviation. For the separation angle, results of all three cases are very close. They differ from the experimental data by approximately 1 degree, partly due to the mesh resolution. This numerical example demonstrates that the correct pressure boundary condition and divergence-free velocity solution are decisive in the flow separation prediction, which subsequently influences the wake length and drag estimates. Our proposed formulations thus provide a critical improvement in the modeling fidelity.

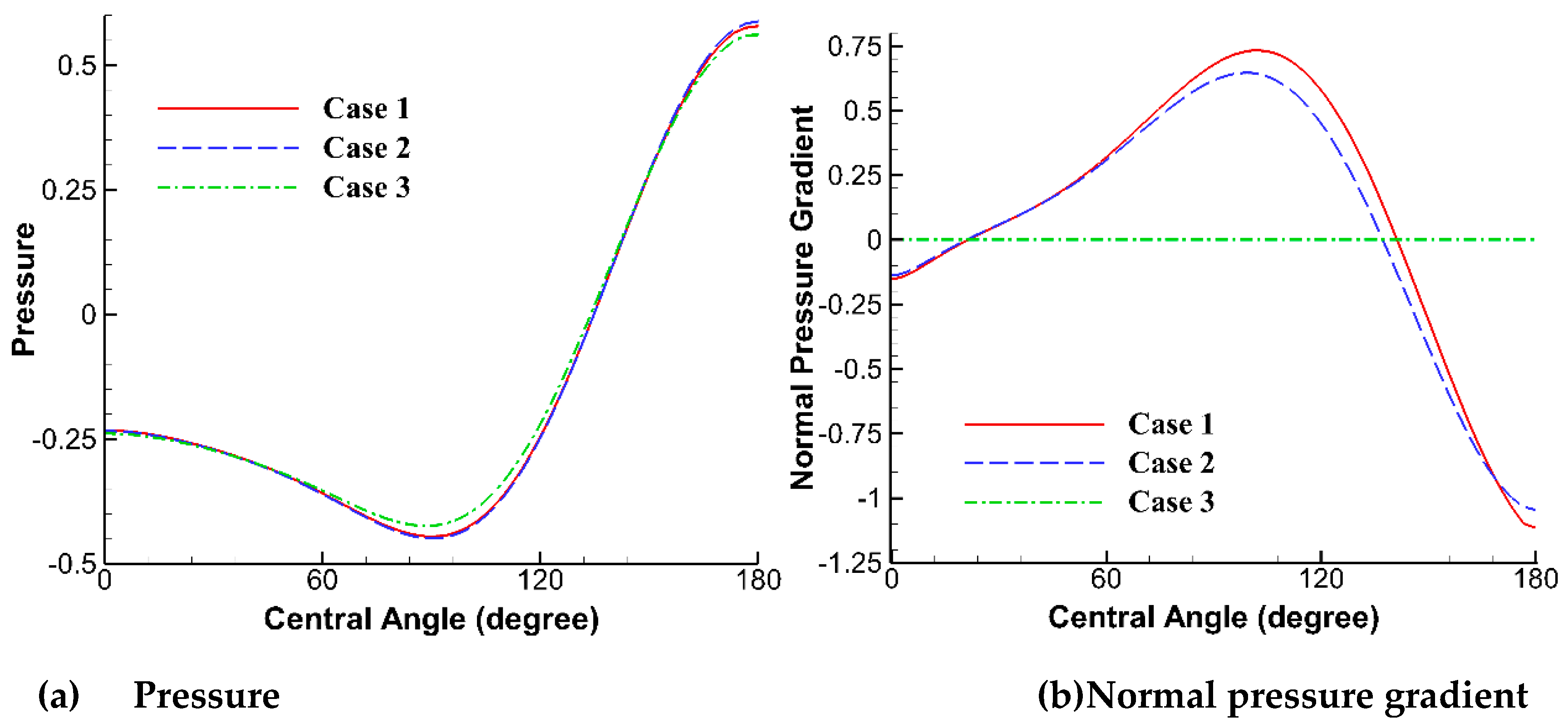

Figure 6 compares the pressure and normal pressure gradient on the upper half-cylinder surface along the central angle (θ), which starts from the rear stagnation point. In

Figure 6(a), Case 1 and Case 2 display nearly identical pressure curves, while the curve of Case 3 is slightly smaller in magnitude. Overall, their predictions are in close agreement. That also indicates very similar tangential pressure gradients along the cylinder surface. However, differences between the three cases become more pronounced for the normal pressure gradients, which are post-processed from the pressure solutions using a one-sided scheme. Case 1 resolves a peak normal pressure gradient approximately 10% larger than Case 2, whereas the pressure gradient in Case 3 is trivial due to the constraint imposed by its simulation setup. A comparison of Figs. 6(a) and (b) reveals that nearly identical boundary pressure values can correspond to distinct normal pressure gradients, which will impact both pressure and velocity solutions. This observation casts doubt on the validity of the practice adopted by some researchers [10, 16], namely, replacing the Neumann pressure boundary condition on solid walls with a consistent Dirichlet boundary condition, even if the Dirichlet-specified pressure values are accurate. Based on the curl-free relationship for the pressure gradients, ∂P

n/∂

τ = ∂P

τ/∂

n, this distinction in normal pressure gradients also accounts for the difference in tangential pressure gradients next to the wall surface, which affects the flow separation predictions.