Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

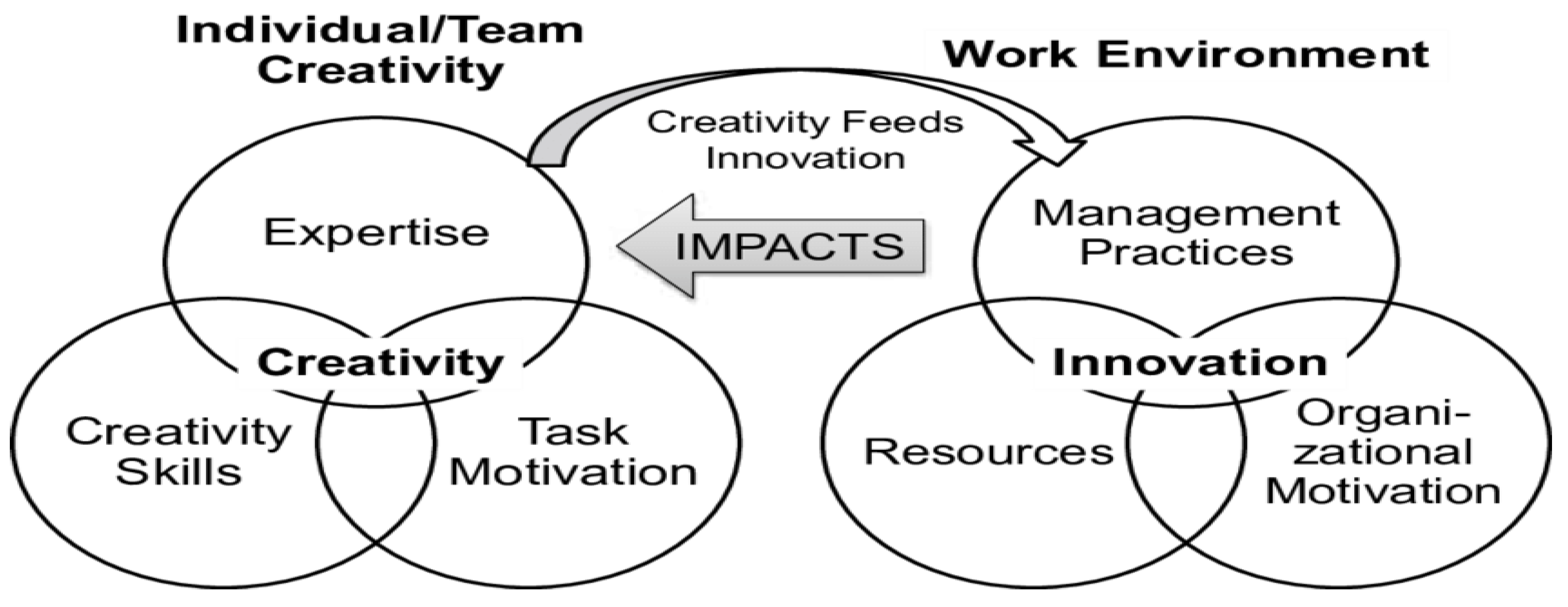

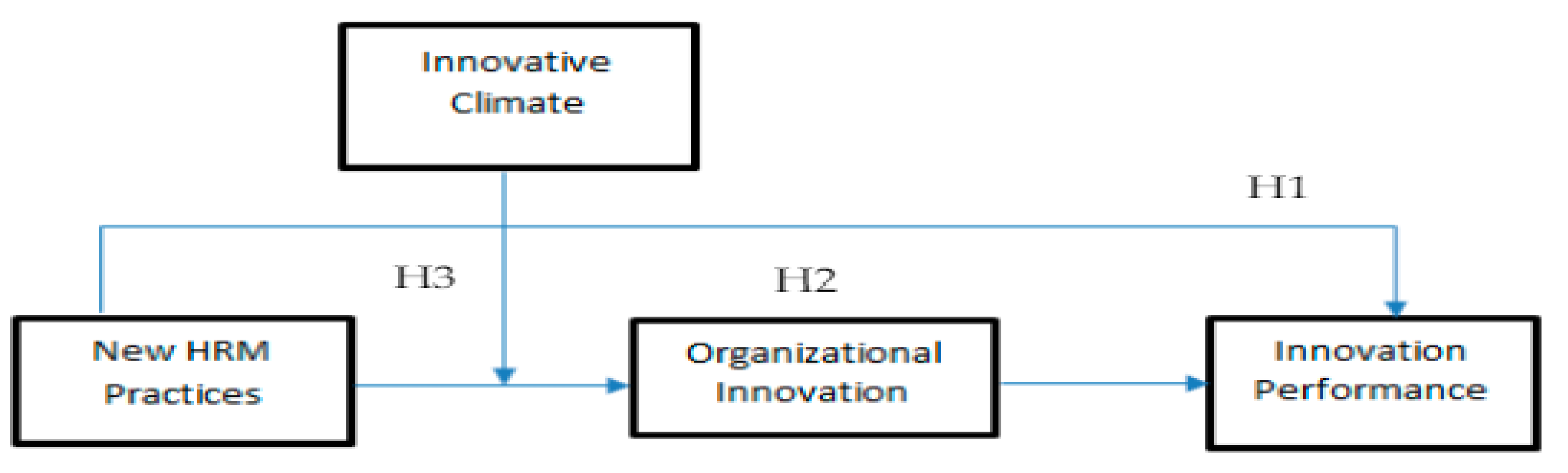

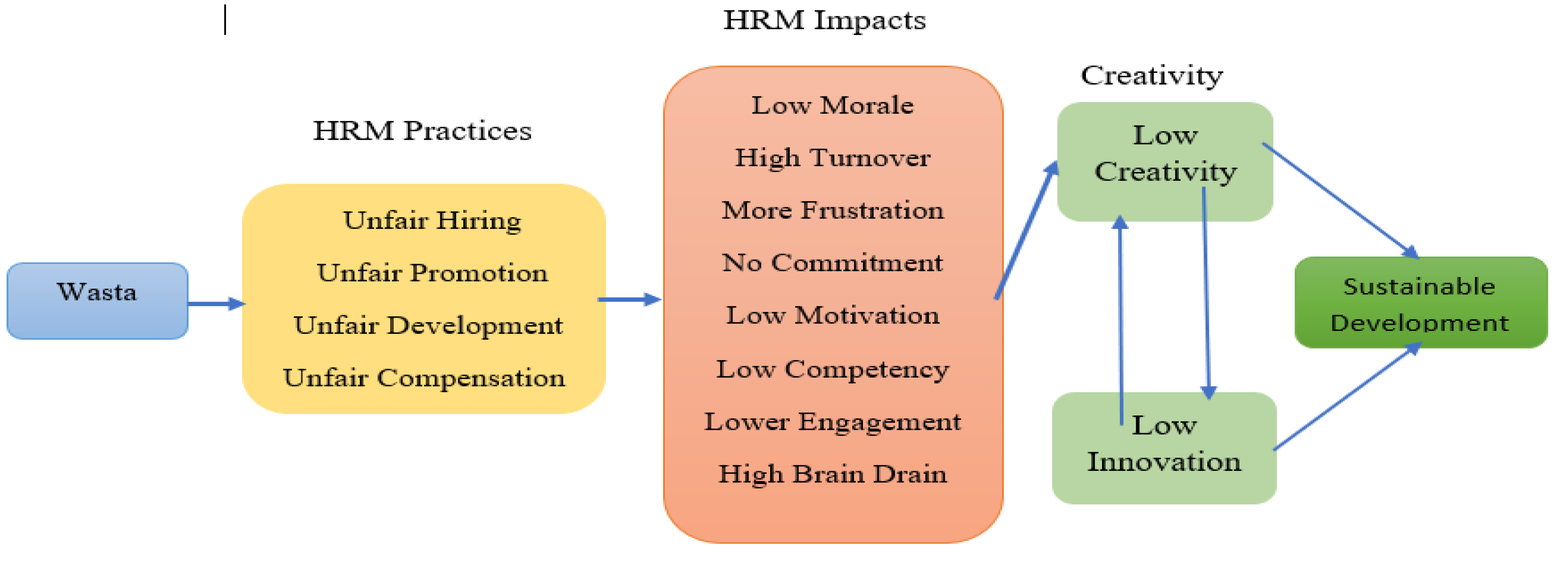

This study examines Wasta practiced by senior human resource management employees, entrepreneurial creativity, innovation, and sustainable development in the MENA and why the MENA entrepreneurs and their home countries are not among the top 100 innovators in the Global Innovation Index. In addition, the study explains why senior human resource management employees’ Wasta practices impede sustainable development. The author used Amabile’s Componential Theory of Organizational Creativity and Amabile’s Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations, articles published in Wasta, secondary data from the Global Innovation Index (GII) in 2023, and the (GEM NECI) in (2023) to support the arguments. The author analyzed the secondary datasets using a qualitative comparative analysis (constant analysis technique) to analyses documents. The analyzed datasets include accessible online indices, electronic and databases from the Global Innovation Index (GII) in 2023, the World’s Most Innovative Companies Index (Forbes), and the Top 100 Global Innovators 2024 Rankings Report (Clarivate). The study results conclude that Wasta practiced by senior human resource management employees is more likely to explain why MENA entrepreneurs are less creative, less innovative, lag in acquiring sustainable development, and why their countries are not ranked in the top 100 innovative countries worldwide. Practices. Entrepreneurs should also understand why hiring fair human resource managers and supervisors when selecting candidates and promoting existing employees is critical. Moreover, the results might encourage policymakers to develop and implement new rules and regulations to tackle Wasta practices in the MENA region if they seek better innovative and sustainable development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Global Innovation Index Versus the MENA Region Countries’ Ranking

2.2. Wasta in the MENA and Human Resource Management Practices

2.3. Human Resource Management Wasta Practices Versus Employee Behavior and Entrepreneurial Innovation

2.4. How Wasta Influences Entrepreneurs’ Creativity, Innovation, and Sustainable Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Secondary Data Collection

3.3. Exploring Ranking Indices

- 1)

- Institutions (Institutional environment, Regulatory environment, Business environment)

- 2)

- Human capital and research (i.e., Education, Tertiary education, Research and development.

- 3)

- Infrastructure (Information and communication technologies, General infrastructure, Ecological sustainability

- 4)

- Market sophistication (Credit, Investment, Trade, diversification, and market scale).

- 5)

- Business sophistication (Knowledge workers, Innovation linkages, Knowledge absorption). Innovation input pillars grasp parts of the economy that promote and encourage innovative activities. The argument is that today’s innovation inputs equip the foundation for tomorrow’s innovation outputs.

3.4. Choosing Constant Comparison Analysis Technique

- to construct theory as opposed to examining it;

- to equip investigators with analytic instruments for dissecting data

- to help researchers comprehend numerous implications from the dataset(s) presented

- to deliver researchers with a methodical and creative technique for interpreting dataset(s)

- to aid researchers in pinpointing, creating, and interpreting the relationships among the dataset parts when forming a theme.

3.5. Data Analysis and Procedures

3.6. The Study Results

4. Conclusions

| Rank | Country | Total Patents Grants/Number of Patents |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | Israel | 5,358 |

| 22 | Turkey | 3,449 |

| 23 | Saudi Arabia | 2,684 |

| 26 | Iran | 2,250 |

| 37 | United Arab Emirates | 1,048 |

| 43 | Algeria | 610 |

| 46 | Morocco | 579 |

| 48 | Egypt | 495 |

| 56 | Bahrain | 197 |

| 73 | Syria | 65 |

| 75 | Jordan | 61 |

| 98 | Oman | 23 |

| 99 | Kuwait | 19 |

Appendix

| Number | Rank | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | Israel | 52.7 |

| 2 | 32 | United Arab Emirates | 42.8 |

| 3 | 37 | Turkey | 39.0 |

| 4 | 47 | Saudi Arabia | 33.9 |

| 5 | 49 | Qatar | 33.9 |

| 6 | 64 | Iran | 28.8 |

| 7 | 66 | Morocco | 28.8 |

| 8 | 71 | Kuwait | 28.1 |

| 9 | 72 | Bahrain | 27.6 |

| 10 | 73 | Jordan | 27.5 |

| 11 | 74 | Oman | 27.1 |

| 12 | 81 | Tunisia | 25.4 |

| 13 | 86 | Egypt | 23.7 |

| 14 | 94 | Lebanon | 21.5 |

| 15 | 115 | Algeria | 16.2 |

| 16 | 127 | Mauritania | 13.2 |

| 17 | NA | Iraq | NA |

| 18 | NA | Yemen | NA |

| 19 | NA | Sudan | NA |

| 20 | NA | Syria | NA |

| 21 | NA | Libya | NA |

References

- Abdelrahim, D. Y. (2020). The influence of culture on rates of innovation: Re-examining Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. International Journal of Management, 11(9).

- Abdelrahim, Y. (2023). Wasta and Corruption: The Case of Sudan. Humanities & Natural Sciences Journal, 4(2), 1157-1168.A.

- Aidt, T. S. (2010). Corruption and sustainable development. International handbook on the economics of corruption, 2, 1-52.

- Aladwan, K., Bhanugopan, R., & Fish, A. (2014). Managing human resources in Jordanian organizations: challenges and prospects. International journal of Islamic and middle eastern finance and management, 7(1), 126-138. [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, M., & Robertson, M. (2014). The role of wasta in shaping the psychological contract: A Saudi Arabian case study. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, p. 15447). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management. Paper presented at 74th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, United States.

- Aldossari, M., & Robertson, M. (2016). The role of wasta in repatriates’ perceptions of a breach to the psychological contract: A Saudi Arabian case study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(16), 1854-1873. [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M., Hassan, S., Abdelrahim, Y., & Albadry, O. (2022, March). Wasta and favoritism: The case of Kuwait. In International Conference on Business and Technology (pp. 705-716). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Alenezi, M., Hassan, S., Abdelrahim, Y., & Albadry, O. (2022, March). Wasta and favoritism: The case of Kuwait. In International Conference on Business and Technology (pp. 705-716). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Alkhanbshi, A. S., & Al-Kandi, I. G. (2014). The religious values and job attitudes among female Saudi bank employees: A qualitative study. Journal of WEI Business and Economics, 3(1), 28-35.

- Alsarhan, F., & Valax, M. (2021). Conceptualization of wasta and its main consequences on human resource management. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 14(1), 114-127. [CrossRef]

- Alsarhan, F., & Valax, M. (2021). Conceptualization of wasta and its main consequences on human resource management. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 14(1), 114-127. [CrossRef]

- Alsarhan, F., Ali, S. A., Weir, D., & Valax, M. (2021). Impact of gender on use of wasta among human resources management practitioners. Thunderbird International Business Review, 63(2), 131-143. [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1982a). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of personality and social psychology, 43(5), 997. [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1983b). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of personality and social psychology, 45(2), 357–377. [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M., & Amabile, T. M. (1983a). The case for a social psychology of creativity. The Social Psychology of Creativity, 3-15. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Amabile, T. M., & Amabile, T. M. (1983b). The case for a social psychology of creativity. The Social Psychology of Creativity, 3-15. Amabile, T.M. (1988a). “A model of organizational innovation.” In B.M. Staw & L.L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, Vol. 10. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Amabile, T.M. (1988b). “From individual creativity to organizational innovation. In K.

- Assad, S. W. (2002). Sociological analysis of the administrative system in Saudi Arabia: In search of a culturally compatible model for reform. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 12(3/4), 51-82. [CrossRef]

- Avnimelech, G., Zelekha, Y., & Sharabi, E. (2014). The effect of corruption on entrepreneurship in developed vs non-developed countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 20(3), 237-262. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A., Yandle, B., & Naufal, G. (2013). Regulation, trust, and cronyism in Middle Eastern societies: The simple economics of “wasta”. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 44, 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. (1879). The principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press.Bentham, J. (1996). The collected works of Jeremy Bentham: An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press.

- Branine, M., & Analoui, F. (2006). Human resource management in Jordan. In Managing human resources in the Middle-East (pp. 145-159). Routledge.

- Branine, M., & Pollard, D. (2010). Human resource management with Islamic management principles: A dialectic for a reverse diffusion in management. Personnel Review, 39(6), 712-727. [CrossRef]

- Budhwar, P. S., & Mellahi, K. (2006). Introduction: Managing human resources in the Middle East. In Managing human resources in the Middle-East (pp. 1-19). Routledge.

- Budhwar, P., & Mellahi, K. (2007). Introduction: human resource management in the Middle East. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R. B., Sarayrah, Y. K., & Sarayrah, Y. E. (1994). Taming” wasta” to achieve development. Arab Studies Quarterly, 29-41.

- Cunningham, R., & Sarayrah, Y. K. (1993). Wasta: The hidden force in Middle Eastern society. (No Title). Praeger Publishers.

- Dutta, S., Lanvin, B., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (Eds.). (2018). The global innovation index 2018: Energizing the world with innovation. WIPO.

- Easa, N. F., & Orra, H. E. (2021). HRM practices and innovation: An empirical systematic review. International Journal of Disruptive Innovation in Government, 1(1), 15-35. [CrossRef]

- ESCAP, U., ECA, U., ECE, U., ESCWA, U., & ECLAC, U. (2017). World economic situation and prospects 2017.

- Fawzi, N., & Almarshed, S. (2013). HRM context: Saudi culture,” Wasta” and employee recruitment postpositivist methodological approach, the case of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Human Resources Management and Labor Studies, 1(2), 25-38.

- Frels, R. K. (2010). The experiences and perceptions of selected mentors: The dyadic relationship in school-based mentoring. Sam Houston State University.

- Gesteland, R. R. (2002). Cross-cultural business behavior: Negotiating, selling, sourcing and managing across cultures (4th ed.). Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. mill valley.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Gronhaug & G. Kaufman (Eds.), Achievement and motivation: A social-developmental perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of international business studies, 14, 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, K., & Weir, D. (2006). Understanding networking in China and the Arab World: Lessons for international managers. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(4), 272-290. [CrossRef]

- Idris, A. M. (2007). Cultural barriers to improved organizational performance in Saudi Arabia. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 72(2), 36–53.

- Kassab, E. (2016). Influence of wasta within human resource practices in Lebanese universities (Doctoral dissertation, CQUniversity).

- Khalfan, S. (2024). Wasta in business management: a critical review of recent developments and future trends in the tourism sector. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Loewenberger, P. (2016). Human resource development, creativity and innovation. In Human resource management, innovation and performance (pp. 48-65). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Madrid-Guijarro, A., Garcia, D., & Van Auken, H. (2009). Barriers to innovation among Spanish manufacturing SMEs. Journal of small business management, 47(4), 465-488. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. (2000). Culture and psychology: People around the world. Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

- Metcalfe, B. D. (2007). Gender and human resource management in the Middle East. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), 54-74. [CrossRef]

- Morrar, R. (2018). Innovation in the MENA Region. Strategic Sectors Economy & Territory.Morrar, R. (2018). Innovation in the MENA Region. Strategic Sectors Economy & Territory.

- Morse, J. W., de Kanel, J., & Craig Jr, H. L. (1979). A literature review of the saturation state of seawater with respect to calcium carbonate and its possible significance for scale formation on OTEC heat exchangers. Ocean Engineering, 6(3), 297-315. [CrossRef]

- Overton, J. (2020). Landscapes of failure: Why do some wine regions not succeed. Fermented landscapes: Lively processes of socio-environmental transformation.Overton, J. (2020). Why DoSome Wine Regions Not Succeed?. Fermented landscapes: Lively processes of socio-environmental transformation, 57.

- Ramady, M. A. (Ed.). (2016). The political economy of wasta: Use and abuse of social capital networking (p. vii). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Routledge, B. R., & Von Amsberg, J. (2003). Social capital and growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 167-193. [CrossRef]

- Seeck, H., & Diehl, M. R. (2017). A literature review on HRM and innovation–taking stock and future directions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(6), 913-944. [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, A., Banai, M., & Dagher, G. K. (2022). Socio-cultural capital in the Arab workplace: Wasta as a moderator of ethical idealism and work engagement. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 45(1), 21-44. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge university press.Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge university press.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research (Vol. 15). Newbury Park, CA: sage.Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research (Vol. 15). Newbury Park, CA: sage.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research (Vol. 15). Newbury Park, CA: sage.Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques.

- Ta’Amnha, M., Sayce, S., & Tregaskis, O. (2016). Wasta in the Jordanian context. In Handbook of human resource management in the Middle East (pp. 393-411). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Talib, A. A. (2017). WASTA: The good, the bad and the ugly. Middle East Journal of Business, 12(2), 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Tytko, A., Smokovych, M., Dorokhina, Y., Chernezhenko, O., & Stremenovskyi, S. (2020). Nepotism, favoritism and cronyism as a source of conflict of interest: corruption or not?. Amazonia investiga, 9(29), 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Von Coombs, H. (2022). The complex identities of international student-athletes competing in the NCAA: an exploratory qualitative case study (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University).

- Waheed, A., Miao, X., Waheed, S., Ahmad, N., & Majeed, A. (2019). How new HRM practices, organizational innovation, and innovative climate affect the innovation performance in the IT industry: A moderated-mediation analysis. Sustainability, 11(3), 621. [CrossRef]

- Wunderle, W. D. (2008). A manual for American servicemen in the Arab Middle East: Using cultural understanding to defeat adversaries and win the peace. Skyhorse Publishing Inc.

- Xin, K. K., & Pearce, J. L. (1996). Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of management journal, 39(6), 1641-1658. [CrossRef]

- Yahchouchi, G. (2009). Employees’ perceptions of Lebanese managers’ leadership styles and organizational commitment. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 4(2), 127-140.

| Source of Information | Themes | Factors Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Literature Reviewed Articles | Theme 1: Culture Theme 2: HRM Practices Theme 3: HRM Impacts Theme 4: HRM Impacts Theme 5: Innovation |

1. PD, COL, HAR, UAE 1. Wasta 2. Unfair Hiring 2. Unfair Promotion 2. Unfair Development 2. Unfair Compensation 3. Low Morale 3. High Turnover 3. More Frustration 3. No Commitment 3. Low Motivation 3. Low Competency 3. Lower Engagement 4. Creativity 4. Innovation 5. Sustainable Development |

| Conditions to start a business based on Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s National Entrepreneurship Context Index (GEM NECI) in (2023). | Theme 1: the quality of a particular economy’s entrepreneurial environment that fosters innovation in a country Theme 2: Factors that enhance, hinder, or hinder entrepreneurial creativity and innovation. |

1. Creativity 2. Innovation |

| The GEM’s National Entrepreneurial Context Index (NECI) | Theme 1: Entrepreneurial conditions. | Innovation |

| Global Innovation Index by Country 2024 | Theme 1: Innovation inputs. | Innovation outputs (patents, knowledge creation, knowledge diffusion, patents, technical and scientific publications) |

| The World’s Most Innovative Companies Index (Forbes) | Theme 1: Innovation impact ranking. | Innovative companies |

| The World’s Most Entrepreneurial Countries, 2024 | Theme 1: Easy access to capital for entrepreneurs, Skilled workforce, and competitive business environment. Theme 2: Entrepreneurial environment. |

Innovation |

| Patents by Country / Number of Patents Per Country 2024 | Theme 1: requirements, Patent laws, procedures, national laws, procedures. | Creativity Patents |

| Rank | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 42.88 |

| 2 | Germany | 41.05 |

| 3 | United Kingdom | 35.8 |

| 4 | Israel | 34.25 |

| 5 | United Arab Emirates | 31.01 |

| 6 | Poland | 29.75 |

| 7 | Spain | 29.01 |

| 8 | Sweden | 28.16 |

| 9 | India | 25.47 |

| 10 | France | 25.34 |

| 11 | Australia | 25.05 |

| 12 | Estonia | 24.64 |

| 13 | Ireland | 24.37 |

| 14 | Malaysia | 23.6 |

| 15 | Saudi Arabia | 22.98 |

| 16 | South Korea | 22.43 |

| 17 | Canada | 21.8 |

| 18 | Philippines | 21.62 |

| 19 | Denmark | 21.42 |

| 20 | Switzerland | 21.34 |

| 21 | Taiwan | 21.24 |

| 22 | Japan | 20.71 |

| 23 | Singapore | 20.05 |

| 24 | China | 20.04 |

| 25 | Austria | 19.92 |

| 26 | Portugal | 19.73 |

| 27 | Belgium | 19.72 |

| 28 | Italy | 19.46 |

| 29 | New Zealand | 18.55 |

| 30 | Thailand | 18.32 |

| 31 | Colombia | 18.25 |

| 32 | Bulgaria | 18.05 |

| 33 | Chile | 17.41 |

| 34 | Czech Republic | 17.37 |

| 35 | Mexico | 17.37 |

| 36 | Norway | 17.22 |

| 37 | Cyprus | 17.16 |

| 38 | Argentina | 16.96 |

| 39 | Latvia | 16.76 |

| 40 | Serbia | 16.55 |

| 41 | Brazil | 16.4 |

| 42 | Romania | 16.25 |

| 43 | Hungary | 16.19 |

| 44 | Netherlands | 16 |

| 45 | Indonesia | 15.42 |

| 46 | Greece | 15.23 |

| 47 | Croatia | 15.2 |

| 48 | South Africa | 15.12 |

| 49 | Luxembourg | 15.05 |

| 50 | Rwanda | 14.96 |

| 51 | Turkey | 14.95 |

| 52 | Slovenia | 14.86 |

| 53 | Slovakia | 14.8 |

| 54 | Russia | 14.79 |

| 55 | Belarus | 14.71 |

| 56 | Peru | 14.65 |

| 57 | Iceland | 14.65 |

| 58 | Qatar | 14.54 |

| 59 | Armenia | 14.41 |

| 60 | Malta | 14.4 |

| 61 | Morocco | 14.32 |

| 62 | Moldova | 14.23 |

| 63 | Kenya | 14.2 |

| 64 | Nigeria | 14.11 |

| 65 | Azerbaijan | 14.07 |

| 66 | Finland | 14 |

| 67 | Kazakhstan | 13.87 |

| 68 | Puerto Rico | 13.86 |

| 69 | Uruguay | 13.84 |

| 70 | North Macedonia | 13.59 |

| 71 | Georgia | 13.57 |

| 72 | Lithuania | 13.55 |

| 73 | Ukraine | 13.53 |

| 74 | Vietnam | 13.44 |

| 75 | Jordan | 13.38 |

| 76 | Tunisia | 13.38 |

| 77 | Ghana | 13.35 |

| 78 | Ecuador | 13.34 |

| 79 | Bahrain | 13.34 |

| 80 | Sri Lanka | 13.18 |

| 81 | Dominican Republic | 13.16 |

| 82 | Albania | 13.16 |

| 83 | Costa Rica | 13.06 |

| 84 | Bangladesh | 12.99 |

| 85 | Jamaica | 12.91 |

| 86 | Botswana | 12.85 |

| 87 | Lebanon | 12.8 |

| 88 | Iran | 12.66 |

| 89 | Cameroon | 12.65 |

| 90 | Egypt | 12.59 |

| 91 | Uganda | 12.59 |

| 92 | Venezuela | 12.59 |

| 93 | Trinidad &Tobago | 12.52 |

| 94 | Paraguay | 12.39 |

| 95 | Bolivia | 12.32 |

| 96 | Algeria | 12.28 |

| 97 | Ethiopia | 12.27 |

| 98 | Zambia | 12.27 |

| 99 | Pakistan | 12.24 |

| 100 | El Salvador | 12.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).